Scotland's Biodiversity Progress to 2020 Aichi Targets - Report 2019

This report presents an assessment of Scotland's progress towards meeting the 20 Global Aichi Targets. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) set 20 global targets, known as Aichi Targets, to be met by 2020. The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy: 2020 Challenge for Scotland's Biodiversity sets the strategic priorities for Scotland, and the Route Map to 2020 identifies the large-scale collaborative projects that are needed to contribute to these targets. For Scotland, out of the 20 Aichi targets, nine are assessed as being on track, and the other 11 are showing progress. We shall publish a final report later in the year.

Pages: 98

Published: 2021

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Account development

- Summary of findings

- Next steps

- Aichi accounts

- AICHI Target 1 – Awareness increased | A1 References end notes

- AICHI Target 2 – Biodiversity values integrated | A2 References end notes

- AICHI Target 3 – Incentives reformed | A3 References end notes

- AICHI Target 4 – Sustainable consumption & production | A4 References end notes

- AICHI Target 5 – Habitat loss halved or reduced | A5 References end notes

- AICHI Target 6 – Sustainable management – marine | A6 References end notes

- AICHI Target 7 – Sustainable agriculture, aquaculture & forestry | A7 References end notes

- AICHI Target 8 – Pollution reduced | A8 References end notes

- AICHI Target 9 – Invasive species prevented and controlled | A9 References end notes

- AICHI Target 10 – Pressures on vulnerable ecosystems reduced | A10 References end notes

- AICHI Target 11 – Protected areas increased and improved | A11 References end notes

- AICHI Target 12 – Extinction prevented | A12 References end notes

- AICHI Target 13 – Genetic diversity maintained | A13 References end notes

- AICHI Target 14 – Ecosystems & services safeguarded | A14 References end notes

- AICHI Target 15 – Ecosystems restored & resilience enhanced | A15 References end notes

- AICHI Target 16 – Nagoya protocol in force & operational | A16 References end notes

- AICHI Target 17 – National Biodiversity Strategy & Action Plan | A17 References and notes

- AICHI Target 18 – Traditional knowledge respected | A18 References end notes

- AICHI Target 19 – Knowledge improved, shared and applied | A19 References end notes

- AICHI Target 20 – Financial resources increased | A20 References end notes

- Annex 1: Relationship between Aichi Targets and Route Map to 2020 Priority Projects

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this report was led by David O’Brien and Simon Foster with considerable input from Debbie Bassett, Alan Cameron, Professor Des Thompson, Iain Macdonald and Kamila Fraser.

The work was overseen by a sub-group of the Scientific Advisory Committee of SNH which included Professor Bob Furness, Professor Jeremy Wilson, Dr Ruth Mitchell and Dr Aileen Mill.

Introduction

This report presents an assessment of Scotland’s current progress towards meeting the Global Aichi Targets.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) set 20 global targets, known as Aichi Targets, to be met by 2020. The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy: 2020 Challenge for Scotland’s Biodiversity sets the strategic priorities for Scotland and the Route Map to 2020 identifies the large-scale collaborative projects that are needed to contribute to these targets.

In 2016 an initial assessment of 13 Aichi Targets was published using recognised CBD guidance and design standards. The ensuing reporting standard, proposed by Scotland, has now been adopted for the UK. The 2017 report and this latest report contain an assessment of progress against each of the 20 Aichi Targets. The evidence base continues to be developed. We intend that this assessment will attract interest and engagement which helps us develop the final 2020 report.

Background

In October 2010 the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) agreed a Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and set 20 international targets known as ‘Aichi Targets’.

In 2010, SNH undertook a national assessment of biodiversity achievements in Scotland. This assessment concluded the following:

- Progress for Scotland’s biodiversity has been made by many people and organisations that care about Scotland’s biodiversity. Biodiversity loss had been slowed where targeted action had been applied.

- However, Scotland’s biodiversity indicators, the condition of notified habitats and species in protected areas, and progress towards meeting Scotland’s biodiversity targets demonstrated that biodiversity loss had not halted and would require renewed and sustained effort over a longer period.

The UK is a signatory to the CBD and submitted a full report in March 2019, which included progress on each Aichi Target. In Scotland, the Scottish Government has also indicated that we should undertake an assessment in 2019 and a final assessment at the end of 2020.

Account development

The Aichi Targets are wide ranging and diverse in nature and present challenges both in terms of delivery and reporting. This is the second time we have reported on all 20 targets in Scotland and we were the first nation in 2017 to report progress to the Convention on Biological Diversity on the full suite of targets. The collation of data and information across such a wide range of areas from financial resource allocation to knowledge transfer and conserved genetic resources has presented considerable challenges. We have enlisted the collaboration, advice and support from many organisations including government, agencies, academics, NGOs and research institutes.

The accounts presented are composed of a combination of information and data, the majority are available at a Scotland level, though some are only collated at a UK level. There are some generic issues with information and data that cut across all accounts and require some further work and coordination at the UK level. This applies particularly to data derived from UK indicators, which either require updating or disaggregation for Scotland. We have also attempted to take account of Scotland’s impact on biodiversity elsewhere in the world.

In order to ensure a consistent approach to account development and enable the data and subsequent analysis to contribute to UK reporting, the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) quick guides were used to scope the assessments, with reference to technical documentation and the Global Biodiversity Outlook 4 assessment (GBO4).

We have adopted the five-point scoring system produced by the United Nation Convention on Biological Diversity as shown in Table 1 below to summarise progress against each target.

Figure 1. Five point scale of progress, adapted from Global Outlook 4.

| Description | Icon |

|---|---|

|

On track to exceed target (we expect to achieve this before its deadline) |

|

| On track to achieve target (if we continue on our current trajectory we expect to achieve the target by 2020) |

|

| Progress towards target but insufficient (unless we increase our efforts the target will not be met by its deadline) |

|

| No significant overall progress (overall, we are neither moving towards the target nor moving away from it) |

|

| Moving away from target (things are getting worse rather than better) |

|

Following collation of information and data for each Aichi account, an assessment of status using the UN scale of progress shown above was assigned to each Aichi Target. This was undertaken by relevant experts within and out-with SNH. The Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) Scientific Advisory Committee provided quality assurance and expert advice through-out Aichi target account development and assessment.

Summary of findings

An account of progress with each Aichi Target in Scotland is provided with a summary of the assessment of each target list below. There are nine Aichi targets assessed as being on track. A further 11 are showing progress, but requiring additional action if we are to meet these targets by 2020.

The Convention on Biological Diversity brigaded the Aichi Targets under five strategic goals covering; A) mainstreaming; B) direct pressures; C) biodiversity status; D) benefits to all; and E) enhanced implementation.

There are a number of areas where Scotland is progressing well with mainstreaming biodiversity, including work to increase public awareness and engagement and embedding biodiversity values through the development of policy and practice on natural capital; brigaded under Strategic Goal A. But there appears to be a time lag in terms of translating these ambitions into changes in practice and clearly influencing decision making across key sectors of government and society. A priority has been given to mainstreaming biodiversity across government, public bodies and business under the recently established Scottish Biodiversity Programme; which will include work to reform incentives to better support biodiversity and reduce harm. Further action is required to ensure we understand the impact of other incentives on biodiversity and ensure production and consumption are within safe ecological limits. Stringent carbon targets set by the Scottish Government to achieve net zero carbon by 2045 are aligned with the action required, in terms of production and consumption.

The areas of work that have proved most challenging is actions contributing to the Aichi Targets brigaded under the Strategic Goal B which relate to the direct pressures on biodiversity. Although positive changes in relation to sustainable management, pollution reduction and protection of ecosystems vulnerable to climate change are underway, there is still more to do particularly in relation to herbivore impacts, invasive species, some aspects of sustainable marine management and the increasing pressure of climate change. Development of improved metrics and focused action on a range of pressures are planned and being implemented. Utilisation and further development of ecosystem health indicators will help to identify where to prioritise our efforts.

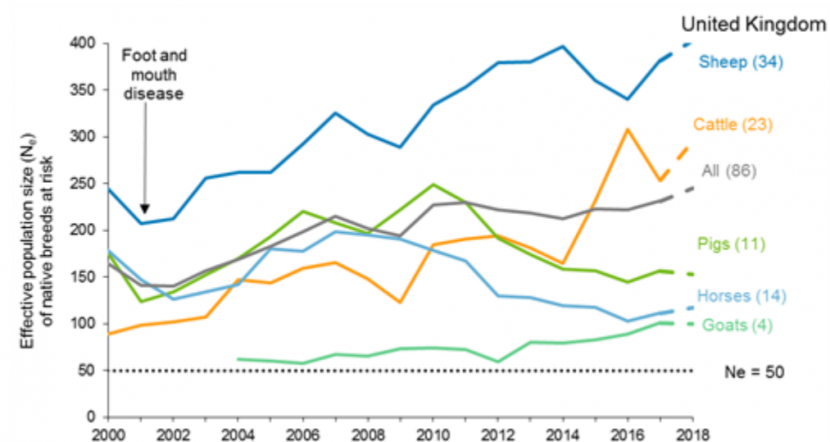

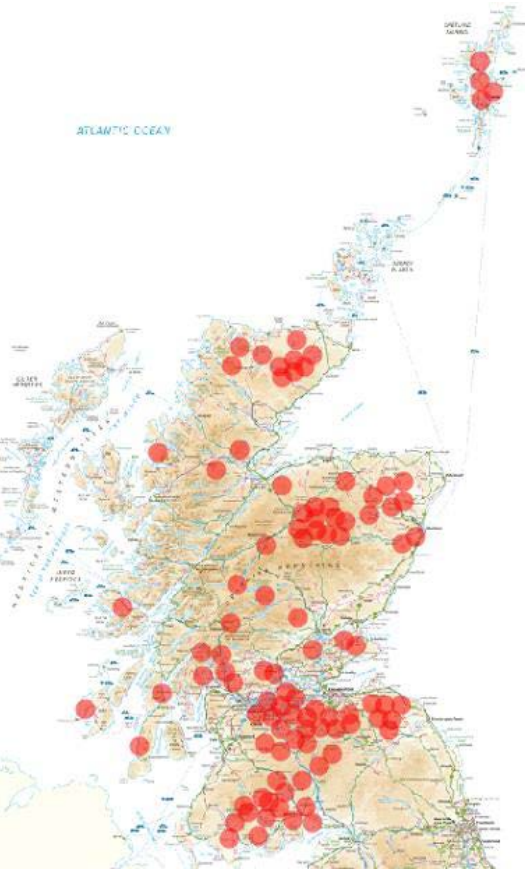

There has been good progress in safeguarding biodiversity with the designation of marine and terrestrial protected areas now exceeding the international target. However, further progress on improving the conservation status of protected areas is needed to meet Scottish Government targets. The creation of Scotland’s National Marine Plan and the reformed Common Fisheries Policy, along with the Marine Strategy Framework Directive are all helping to focus efforts towards sustainable management in the marine environment. Work collated under Strategic Goal C will continue to 2020 to ensure management, representativeness, integration, and connectivity is improved. Further work is underway including the development of a seabird conservation strategy for Scotland and focused action for waders such as curlew. A Biodiversity Challenge Fund for Scotland, of £4million has been established to support projects delivering actions contributing to biodiversity Aichi targets and climate change adaptation. In Scotland a genetic diversity indicator for terrestrial and freshwater species of cultural and socioeconomic importance has been developed. This has been endorsed by IUCN as a method for assessing genetic diversity that is applicable across the world. The detailed report has been published as a supplementary report. Work is underway in Scotland to develop a combined biodiversity indicator for a wide suite of species.

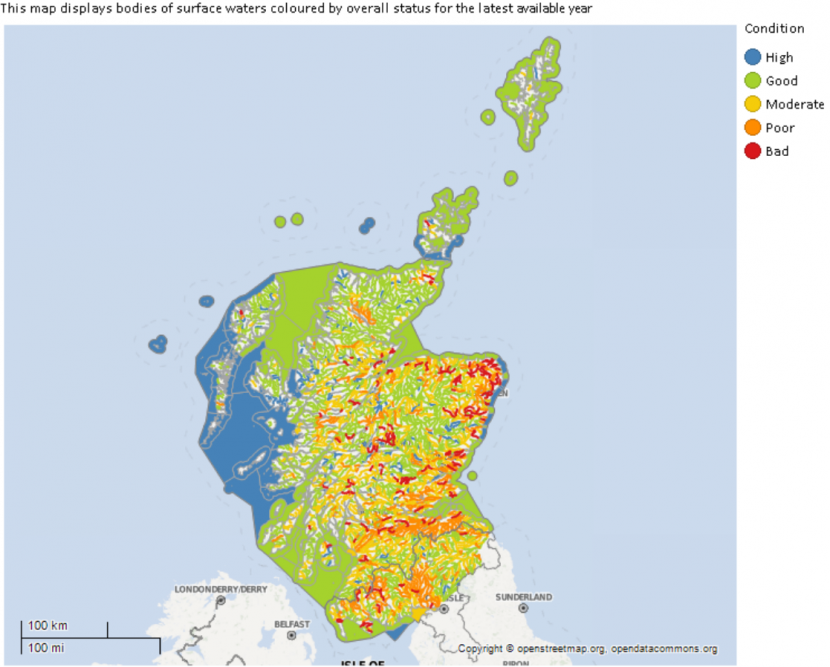

The Aichi Targets relating to Strategic Goal D; benefits to all from biodiversity and ecosystem services have been progressed well. A suite of regulations are in place across the UK to ensure compliance with the Nagoya Protocol which safeguards the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the utilisation of genetic resources. The restoration of peatlands across Scotland is increasing year on year and the ecological status of freshwaters habitats is continuing to improve. Ambitious targets for native woodland restoration and improving condition have yet to be met, but establishment of new native woodland is progressing. The Lowland Deer Panel has completed an assessment and reported to SNH on sustainable lowland deer management in Scotland. The development of upland deer management plans has been completed and now deer management groups are beginning to implement these plans. Both the ecological and wider social, economic and environmental benefits of these actions will take some time to realise. Much work is on-going and continues to be developed to ensure ecosystem services are safeguarded; such as the EcoServ GIS tool for Scotland and the application of the Ecological Coherence Protocol.

Finally, there is mixed progress on the Aichi Targets that comprise Strategic Goal E. The continued implementation of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and the Route Map to 2020 is regularly reported to the Scottish Parliament and Ministers. The fourth annual progress report on the latter concludes that three targets have already been achieved, nine targets are progressing well, with only two targets not currently on track. The protection of traditional knowledge and the rights of communities are contributing positively to Scotland’s biodiversity. The improved collation of data and data management are ensuring decisions are informed and information is shared and accessible. More work is required to address improved data recording, data analysis gaps and data relating to ecosystem functions. Over the period there has been a move towards dedicated funding towards biodiversity projects, which cover a wide range of work connecting people and nature.

Summary assessments of the 20 Aichi Targets

| Aichi Target Name | Target assessment |

|---|---|

|

A1 Awareness increased Biodiversity awareness in Scotland is currently measured at around 71%. There are a large number of organisations actively seeking to promote biodiversity and help raise the awareness of conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. |

|

|

A2 Biodiversity values integrated Scotland is a world leader in developing the concept of natural capital, and actively promotes biodiversity through strategies and policies. Whilst challenges remain to embed conservation and sustainable use in practice, biodiversity values have been integrated into the mainstream planning, policy and reporting frameworks. |

|

|

A3 Incentives reformed Incentives help to influence behaviour towards achieving a range of aims. They can encourage activity that can promote biodiversity. However, in Scotland some conflict with biodiversity leading to its deterioration and sometimes loss. |

|

|

A4 Sustainable consumption & production Sustainability is an integral part of Scotland’s economy and enshrined within the Government Economic Strategy. Scotland is committed to being a low carbon economy and has ambitious targets to achieve this. However, not all indicators show confidently that we operating within safe ecological limits. |

|

| Aichi Target Name | Target assessment |

|---|---|

|

B5 Habitat loss halved or reduced Some of Scotland’s habitats have suffered degradation and losses through changes in land use and management. Targeted restoration is underway on peatland, woodland and freshwater habitats. Work is ongoing to improve protection of Priority Marine Features and the Scottish MPA network through implementing fisheries management measures The Habitat Map of Scotland provides baseline habitat data and will enable us, in time, to look at changes in Scotland’s habitats. The Ecosystem Health Indicators will improve our knowledge of habitat fragmentation. |

|

|

B6 Sustainable management – marine Considerable progress has been made in ensuring fish, invertebrate and aquatic plants are harvested sustainably and in line with Scottish and European legal frameworks. The latest fishery stock assessments show that they are at Good Environmental Status (GES) for the Greater North Sea ecoregion. In the Celtic Seas ecoregion, a number of stocks have very low biomasses and are not sustainable. The development of Scotland’s National Marine Plan, and Aquaculture, Seaweed Harvesting and Fisheries Strategies along with the UK Marine Strategy are all helping to focus efforts towards sustainable management in the marine environment. |

|

|

B7 Sustainable agriculture, aquaculture & forestry Agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are important industries in Scotland. Considerable progress has been made in developing policies and strategies that will help achieve and support sustainability targets by 2020. |

|

|

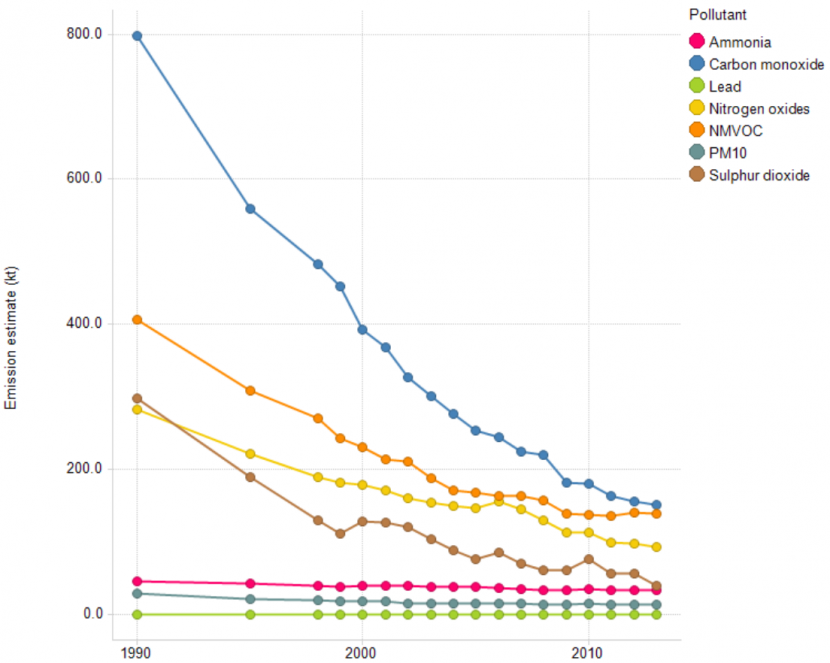

B8 Pollution reduced Improvements to air and water quality over recent decades, brought about by reduced pollution, have led to marked improvements in their status. However, work remains to be done, with more challenging measures required to control air pollution and diffuse pollution, control marine litter, and better quantify the effects of pollution on Scotland’s biodiversity and ecosystems. |

|

|

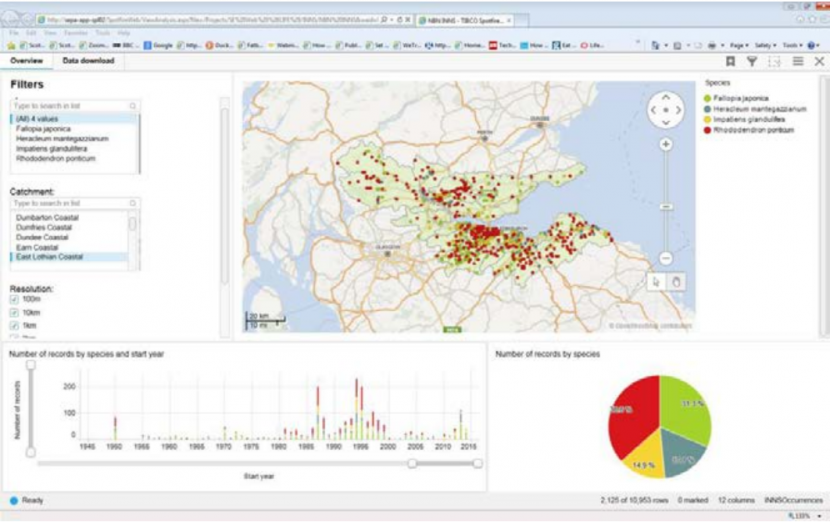

B9 Invasive species prevented and controlled Action to control the most problematic non-native invasive species is underway and new information systems are being developed to inform rapid response. However, the spread of invasive non-native species and their impacts on biodiversity is a present and growing threat. |

|

|

B10 Pressures on vulnerable ecosystems reduced In Scotland terrestrial ecosystems vulnerable to climate change include uplands, peatlands and oak woodland. Coastal habitats such as machair and saltmarsh as well as intertidal habitats are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and increased air and water temperature. Many marine habitats and species such as cold water corals, maerl beds, serpulid reefs, horse mussel and flame shell beds are considered vulnerable to various factors such as temperature increase and ocean acidification. Steps are being taken to identify pressures and to make ecosystems more resilient through protecting sites, voluntary codes and enacting legislation. |

|

| Aichi Target Name | Target assessment |

|---|---|

|

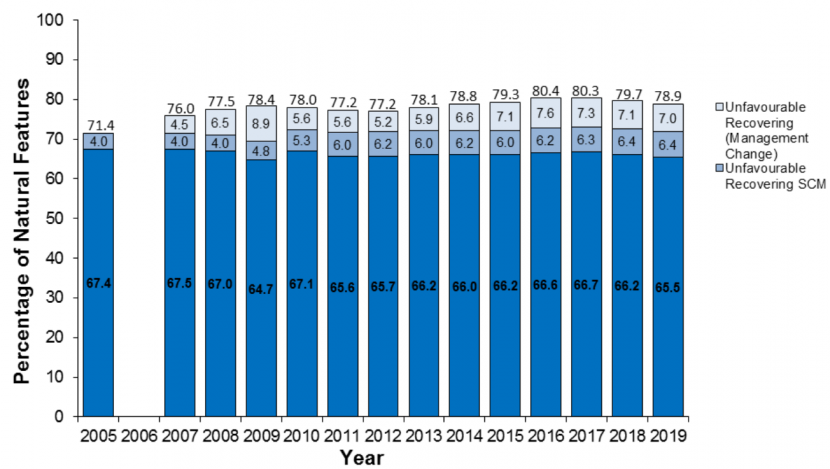

C11 Protected areas increased and improved Species, habitats and geology of national and international importance in Scotland are safeguarded in a suite of protected areas, contributing to halting biodiversity loss. By March 2019 some 22.7% of terrestrial and inland water areas and 17.6% of marine areas had been brought under site protection, with 78.9% of designated features in favourable (including recovering) condition. Although the area percentages exceed the Aichi Target, the condition target is lower than the 80% national target and shows no significant improvement from the 2010 level. More work is still required on management, representativeness, integration, and connectivity of sites. |

|

|

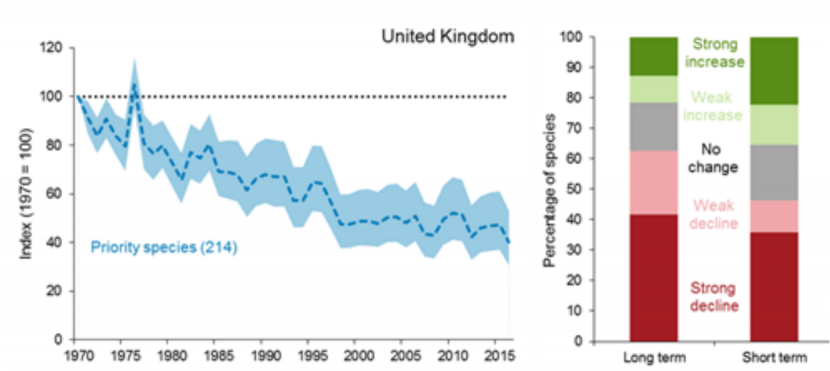

C12 Extinction prevented In historical times, there has been only one case of a Scottish vertebrate going extinct worldwide: the great auk which went extinct in Scotland in 1840, and globally in 1844. The Manx shearwater flea (Ceratophyllus fionnus) and Caledonian planthopper (Cixius caledonicus), have not been recorded since the 1960s and are therefore presumed extinct. From a biological viewpoint, in many cases it is appropriate to look at extinction risk across the British Isles as a whole, as well as the Scottish context. The UK Indicator shows some evidence of a slowing in the rate of decline in abundance of the UK’s priority species. There is a mixed picture from Scotland’s species indicators: with seabirds, waders, upland birds, and specialist butterflies in decline; generalist butterflies, woodland birds, and geese are increasing. Further work is required to develop a Scotland priority species indicator, and improvement of the taxonomical breadth of our GB-Red Lists, and indicator suite. |

|

|

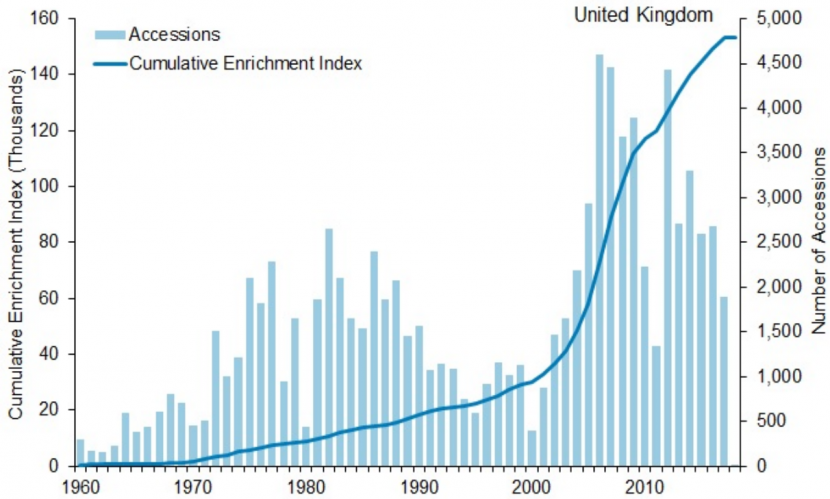

C13 Genetic diversity maintained There is no universally agreed metric of how genetic diversity should be measured and the subject itself is complex. However, Scotland has developed metrics for wild species to complement our knowledge of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals. A detailed assessment of key species is published as a supplementary report. The UK’s first Gene Conservation Unit (GCU) was declared at Beinn Eighe in Wester Ross for Scots pine and further GCUs are being developed. Overall there are effective monitoring schemes in place and active genetic conservation programmes. |

|

| Aichi Target Name | Target assessment |

|---|---|

|

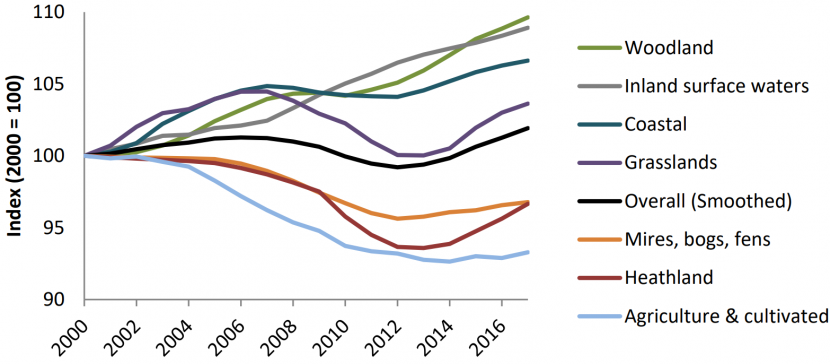

D14 Ecosystems & services safeguarded Scotland has a variety of ecosystems which provide essential services for environmental, cultural, recreational and economic purposes. These include large rivers and lochs, woodlands along with an extensive coastline and marine area. The overall measure shows Scotland’s natural capital deteriorated historically until the 1990s. Most habitat types were declining during this period, especially bogs and grassland. However, stocks have stabilised or slightly improved since 2000. Numerous policies, directives and legislation help us to safeguard these ecosystems. The biodiversity duty placed on all public sector bodies in Scotland further protects them. Clean drinking water is widely available with 99.91% of samples at point of use meeting EU Drinking Water Directive standards. |

|

|

D15 Ecosystems restored & resilience enhanced Reversing ecosystem degradation, loss and fragmentation are key aims of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy. Considerable efforts have been made on restoration of some of Scotland’s most threatened habitats over the past few years. In particular peatlands and rivers have seen focused efforts which help towards Scotland’s climate change targets. Rivers have seen continuous improvement in condition over the last 25 years. The area of woodland has more than trebled since 1900, though much of this is non-native commercial plantations. |

|

|

D16 Nagoya protocol in force & operational The UK signed the Nagoya Protocol in 2011. Following public consultation in 2014 the Nagoya Protocol (User Compliance) Regulations 2015 were laid in the UK Parliament on 23 March 2015. Guidance on compliance and provision of an Access and Benefit-sharing (ABS) information platform provides a key tool for facilitating the implementation of the Nagoya Protocol. |

|

| Aichi Target Name | Target assessment |

|---|---|

|

E17 National Biodiversity Strategy & Action Plan adapted as policy instruments The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy; 2020 Challenge for Scotland’s Biodiversity was approved by the Scottish Cabinet and published in 2013. This document sets the strategic direction for biodiversity action in Scotland towards 2030. The Route Map to 2020, published in 2015, provides a clear focus for activity which will significantly contribute to the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy. Both documents represent the policy instruments for biodiversity in Scotland. |

|

|

E18 Traditional knowledge respected Scotland’s traditional languages and the knowledge held by their speakers have gained greater protection since 2005, following the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. New research is safeguarding and sharing traditional knowledge. The rights of communities have been enhanced through several pieces of legislation, particularly since 2000. Traditional land management practices, such as crofting, benefit nationally and internationally important biodiversity. |

|

|

E19 Knowledge improved, shared and applied Scotland has made significant efforts in data delivery and data management systems with The NBN Atlas Scotland, Scotland’s Environment Web, and the Marine Scotland data publishing portal all contributing greatly to improving sharing and application of Scotland’s knowledge. Volunteers and researchers make large contributions to the numbers of species and habitats records and the way we use them. The Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum (SBIF) Review is looking at the future options for biological data management across Scotland as part of the process to ensure that the necessary structures are in place to collect and disseminate biological information. Improved information on the consequences in the loss, values, and functions of Scotland’s biodiversity, could aid us in prioritising conservation action. |

|

|

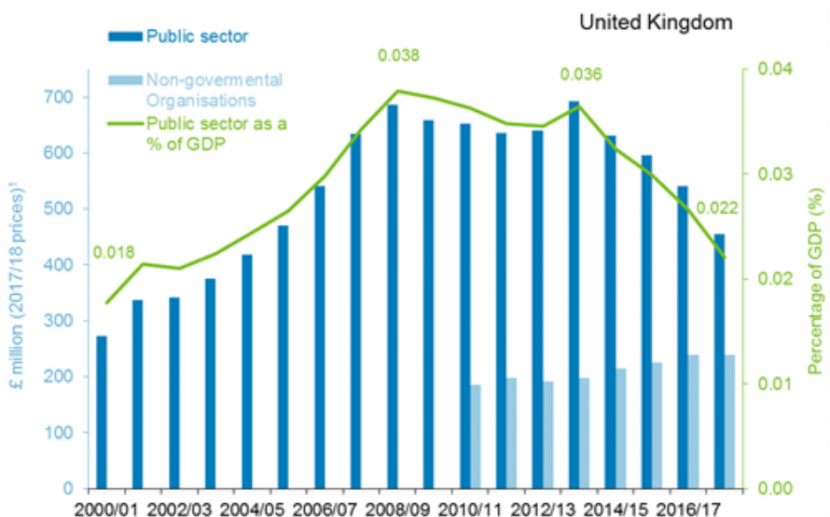

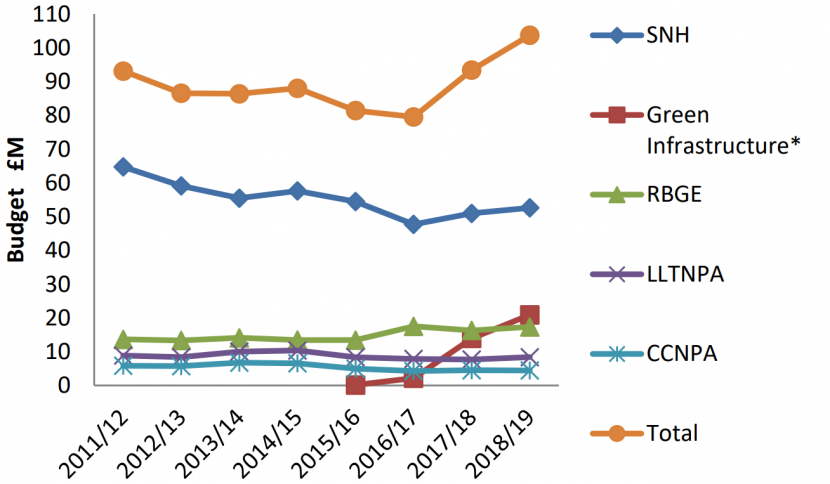

E20 Financial resources increased The UK indicator shows a decline in funding for biodiversity since 2010/11. Overall government funding for biodiversity in Scotland has increased over the same period, mainly through specific targeted projects which connect people and nature, notably the Green Infrastructure Strategic Intervention Programme, and the Peatland Action Programme. Agri- environmental funding is a further major source of resources to maintain and enhance the natural heritage. |

|

Next steps

The final assessment on progress towards the Aichi Targets in Scotland will be published in late 2020.

In order to achieve this, we will continue to build capacity and engage a wider audience in the assessment process. We would welcome feedback on the direction and pace of progress to-date, and views on further development of reporting against the Aichi Targets.

Aichi accounts

The 20 accounts are documented in the following section.

AICHI TARGET 1 - AWARENESS INCREASED

By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.

![]() Biodiversity awareness in Scotland is measured at around 71%. There are a large number of organisations actively seeking to promote biodiversity and help raise the awareness of conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Biodiversity awareness in Scotland is measured at around 71%. There are a large number of organisations actively seeking to promote biodiversity and help raise the awareness of conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Measuring biodiversity

We measure awareness of the values of biodiversity using a number of methods. Since 2009, the Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey (SNO) has provided an insight into public awareness and engagement with SNH and its work. The SNO includes a number of questions about the public’s views on biodiversity and their participation in activities which help look after the natural environment. Figures from the latest SNO(2020) revealed around 71% of people were concerned about biodiversity. The Scottish Household Survey2 shows that the proportion of people vising the outdoors on a weekly basis has significantly increased (up from 52% in 2017 to 59% in 2018 – the highest level reported since the time series began in 2006) and a continuing increase in the proportion of people who view climate change as an immediate and urgent problem (up from 46% in 2013 to 65% in 2018, with the biggest increase occurring among 16-24 year olds).

The membership figures for environmental NGOs, and number of records submitted to various biological recording schemes also provide insight into awareness and involvement and we have used information from over 35 environmental organisations that form Scottish Environment LINK.3

People throughout Scotland take part in a range of environmental activities, from large scale citizen science projects to focused species-specific research. Figures from Scottish Environment LINK show that around 565,000 people were members of environmental organisations in 2018. Due to the complexities surrounding the membership figures, no allowance can be made for double counting across the 35 organisations that make up the LINK partnership.

The Scotland Counts project was launched in 2011 and is delivered through a partnership between Scottish Government, Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) and The Conservation Volunteers (TCV). SNH has supported the Scotland Counts Project since 2011 to achieve a range of outcomes focussed on engaging communities and mainstreaming Citizen Science. The project aims to ensure that every individual and community in Scotland has the opportunity to develop skills and confidence to understand their local environment through Citizen Science. The Scotland Counts project works with various schools, community groups, volunteers, youth groups and teachers to deliver Citizen Science sessions for all.

Every year the project works directly with over 2,000 participants and supports other TCV colleagues to use Citizen Science with at least another 2,000.

Promoting biodiversity

Promoting biodiversity is a key aim of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy.5 Since its inception in 2004 there has been a range of initiatives rolled out across Scotland, targeting all areas and sectors. More recently in 2013, the 2020 Challenge for Scotland’s Biodiversity6 set out the key steps needed to improve the state of nature in Scotland. The work to deliver this is complex and challenging. Scotland’s Biodiversity - A Route Map to 20209, published in 2015, identifies six ‘Big Steps for Nature’ required to meet the 2013 challenge and a total of 12 ‘Priority Projects’7 to achieve the Big Steps. This includes the following three Priority Projects specifically focused on connecting people with nature:

Priority Project 5: More people experiencing and enjoying nature

Aim: Improve levels of regular participation in outdoor recreation, volunteering and learning by all of Scotland’s people.

Target: Increase regular visits and active travel in greenspace through improved infrastructure, information, and campaigns, and the provision of activities and events.

Priority Project 6: Taking Learning Outdoors

Aim: Increase secondary and primary schools’ access to greenspace and nature for outdoor learning as part of the wider ‘Learning for Sustainability’ agenda.

Target: 100 schools in the 20% most disadvantaged areas across Scotland have access to quality greenspace for outdoor learning.

Priority Project 7: Developing Scotland’s natural health service

Aim: NHS Health Boards to promote health benefits from physical outdoors activity and contact with nature, with green exercise routinely prescribed by health professionals as part of the physical activity pathway.

Target: Improve greenspace quality and use on at least one hospital or health care facility in each NHS health board in mainland Scotland.

A duty to further the conservation of biodiversity was placed on all public sector bodies in Scotland in 2004. This biodiversity duty is about connecting people with the environment and managing biodiversity in the wider environment all around us, including protected sites. The Scottish Government Biodiversity Duty report 2012-2014 provides information regarding Scottish Governments contribution to the biodiversity duty.8 The Public Audit & Post- legislative Scrutiny Committee reviewed these duties in 2018 and made a number of recommendations for improving compliance with both duties.9

| Priority Projects | Relevance | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

PP5 – More people experiencing and enjoying nature |

Increase regular visits and active travel in greenspace through improved infrastructure, information, and campaigns, and the provision of activities and events. |

|

|

PP6 – Taking learning outdoors |

100 schools in the 20% most disadvantaged areas across Scotland have access to quality greenspace for outdoor learning. |

|

|

PP7 – Developing Scotland’s natural health service |

Improve greenspace quality and use on at least one hospital or health care facility in each NHS Health Board in mainland Scotland. |

|

A1 References end notes

1 NatureScot Research report 1198 - Scottish Nature Omnibus 2019

3 Scottish Environment Link

4 TCV The Conservation Volunteers

5 Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and COP 15

7 Scotland's biodiversity: a route map to 2020

8 Scottish Government Biodiversity

9 Scottish Parliament - Post-legislative Scrutiny: Biodiversity and Biodiversity Reporting Duties

AICHI TARGET 2 - BIODIVERSITY VALUES INTEGRATED

By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

![]() Scotland is a world leader in developing the concept of natural capital, and actively promotes biodiversity through strategies and policies. Whilst challenges remain to embed conservation and sustainable use in practice, biodiversity values have been integrated into the mainstream planning, policy and reporting frameworks.

Scotland is a world leader in developing the concept of natural capital, and actively promotes biodiversity through strategies and policies. Whilst challenges remain to embed conservation and sustainable use in practice, biodiversity values have been integrated into the mainstream planning, policy and reporting frameworks.

Ecosystem services

In 2011 Scotland became “the first country in the world to publish a detailed attempt to measure annual changes in its natural capital, based on an evaluation of ecosystem service potential.” 1,2,3

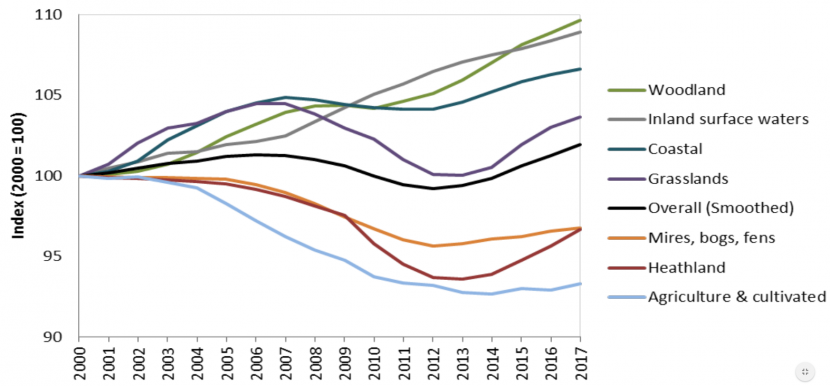

Scotland's Natural Capital Asset Index 2019

Ecosystem services4 are provided by habitats such as forestry,5 freshwater6 and coastal habitats.7 Habitats are assessed by their ability to provide ecosystem services, these services are then weighted by their ability to contribute to human wellbeing.

While there is inevitable uncertainty, these have informed weightings in the Natural Capital Asset Index (NCAI).8 The NCAI covers terrestrial habitats; a feasibility study by Marine Biological Association of the UK into the development of a marine version of the NCAI9 concluded that a marine index is possible but is currently limited by suitable datasets. Based on a survey of scientists, the Scottish Public Opinion Monitor (often known as ‘the Scottish Omnibus survey’) and the relative economic contribution of nature-based tourism, ecosystem service group weightings were derived, as 25% (provisioning), 50% (regulating/maintenance – split equally) and 25% (cultural). Specific services within each group were also weighted to reflect their relative contributions to human wellbeing; for example, the Scotland-wide importance of carbon sequestration was estimated to be twice as important as Freshwater quality regulation.1 The NCAI is underpinned by 38 separate indicators. Biodiversity is recognised as a key indicator of habitat quality as it underpins the functioning and resilience of ecosystems. Quality indicators include several bird indices, urban bird diversity and butterfly indicators. As the natural capital discipline evolves and progresses, the NCAI should remain open to evolving, much in the same way it has done since its inception in 2011 (McKenna, 2019). McVittie et al. (2016)10 state that “challenges remain in developing natural capital accounts. We need biophysical data that reflect changes in condition over time, and that can be linked to both management actions and benefits that can be valued.” The latest assessment11 shows a stabilisation of Scotland’s natural capital following decades of decline until the 1990s. Almost all broad habitat types showed an improvement in 2017, including important habitats such as heath moorland and grassland, though three habitats are still below their level in 2000. Woodland extent continues to increase, including broadleaf woodland covering 20% more land than in 2000. Cultural services increased through increased interactions with the environment: outdoor visits are at their highest rate since 2000. Urban greenspace continues to be perceived as degraded, limiting the benefits people derive from nature in their neighbourhoods.

National policies and Strategies

All public bodies in Scotland have a biodiversity duty12 and are required to publish their compliance with it.13

The Scottish Economic Strategy recognises the need for investment in natural resources. Scottish Planning Policy and the National Planning Framework (NPF3)14 support four key outcomes: A successful sustainable place; a resilient place; a low carbon place; and a more connected place. These policies and frameworks operate at national and sub-national scales.

Scotland’s National Marine Plan15 provides a comprehensive overarching framework for all marine activity in Scotland’s waters. It aims to enable sustainable development and use of marine areas in a way which will protect and enhance the marine environment whilst promoting both existing and emerging industries.

The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy states that biodiversity will be conserved for the health, enjoyment and wellbeing of the people of Scotland.16 The Scottish Land Use Strategy has objectives relating to the economy, environment and communities; and the Principles for Sustainable Land Use to guide policy and decision making by Government and across the public sector.17 The Scottish Government is developing an Environment Strategy for Scotland.18 Other measures that can also help support biodiversity include: European LIFE funding, Heritage Lottery Funds, Scotland’s Rural Development Programme and Land Use Strategy.

Green Infrastructure

Green infrastructure (GI) is ideally a strategically planned network of high quality natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features, which is designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services and to protect biodiversity, in both rural and urban settings.19 Scotland uses European and domestic funding20 to develop and improve green infrastructure. Access to urban greenspace has been shown to be linked to better health, particularly in areas of multiple deprivation.21

| Priority Project | Relevance | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

PP4 – Investment in natural capital |

Businesses are more aware of their reliance on Scotland's natural capital, and more investment is being made in building natural capital. |

|

A2 References end notes

1 Hambrey, J. & Armstrong, A. 2010. Piloting a Natural Capital Asset Index. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 750.

2 Albon, S., Balana, B., Brooker, R. & Eastwood, A. 2014. A systematic evaluation of Scotland’s Natural Capital Asset Index. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 751.

3 McKenna, T., Blaney, R., Brooker, R.W., Ewing, D.A., Pakeman, R.J., Watkinson, P. & O'Brien, D., 2019. Scotland’s natural capital asset index: Tracking nature’s contribution to national wellbeing. Ecological Indicators, 107, p.105645.

4 Brooker, R., Hester, A. & Pakeman, R. eds. 2016. Ecosystem Services. The James Hutton Institute. 28pp.

5 Edwards, D., Elliot, A., Martin, S. et al. 2009. A valuation of the economic and social contribution of forestry for people in Scotland. Forestry Commission Research Report. Forestry Commission Scotland, Edinburgh.

6 Martin-Ortega, J., Holstead, K.L. & Kenyon, W. 2013. The Value of Scotland’s Water Resources. CREW.

7 Scotland's Coastal Assets

8 Technical Guidance

9 Tillin, H.M., Langmead, O., Hodgson, B., Luff, A, Rees, S., Hooper, T. & Frost, M. 2019. Feasibility study for a Marine Natural Capital Asset Index for Scotland. Scottish Natural Heritage Research Report No. 1071.

10 McVittie, A., Novo, P., Nijinik, M. 2016. Valuation and natural capital accounting. In Ecosystem Services. eds. Booker, R., Hester, A. & Pakeman, R. The James Hutton Institute.

11 Information Note

12 The Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004

13 Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011

14 Scottish Planning Policy and the National Planning Framework (NPF3)

15 Scottish Government - Scotland's National Marine Plan

16 Scottish Government Biodiversity

17 Scottish Government Land use strategy

18 Scottish Government Developing an Environment Strategy for Scotland

19 European Commission. 2013. Building a Green Infrastructure for Europe. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

20 Green Infrastructure

21 Mitchell, R., & Popham, F. 2008. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1655-1660.

AICHI TARGET 3 - INCENTIVES REFORMED

By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio-economic conditions.

![]() Incentives help to influence behaviour towards achieving a range of aims. They can encourage activity that can promote biodiversity. However, in Scotland some still conflict with biodiversity leading to its deterioration and sometimes loss.

Incentives help to influence behaviour towards achieving a range of aims. They can encourage activity that can promote biodiversity. However, in Scotland some still conflict with biodiversity leading to its deterioration and sometimes loss.

Incentives in Scotland

In Scotland there is a range of subsidies and incentives available, some of which positively support and influence biodiversity, while others do not. Agricultural and forestry land use covers around 80% of Scotland. The current support mechanism provides around £1.326 billion to land managers, of which around 9% (£125m) goes towards biodiversity, although Scotland’s protected nature sites receive separate funding of some £30m.

Other subsidies exist, including tax incentives for oil and gas exploration and extraction, renewable energy, estate management, house-building and capital allowance. Further analysis is required to understand the implications of these on biodiversity. A stringent planning policy exists that considers biodiversity interests but the degree to which this restricts negative impacts is unknown.

Supporting farming

As part of the measures of support, Cross Compliance is a mandatory set of requirements and standards that land managers have to meet in order to receive support payments. With the reforms to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), all areas under receipt of payments have to meet mandatory criteria to ensure good agricultural and environmental condition (GAEC) is being maintained.1 However, positive and direct payment for agri-environment activity is a limited element within overall farm support.

Although the GAEC criteria should manage negative impacts, particularly for soils, habitats and landscape features on agricultural land, there are anomalies in the current system of funding. To claim funding for any farm, land managers are required to submit details of their land that is eligible for funding. Exclusions exist within this for some natural habitats such as marsh, rock and scree, gorse, and bracken.2 As a result of these exclusions, areas of natural habitat supporting biodiversity may be at risk of loss. A more thorough investigation on the scope of this activity is needed to fully understand the level to which this occurs.

Bioenergy

The dedicated production of feed-stocks to supply bioenergy developments can require large areas of land, which would have otherwise been available for other purposes. This in turn increases pressure on land globally, leading to habitat loss. The Renewable Energy Directive has defined a set of sustainability criteria to ensure that the use of biofuels (used in transport) and bioliquids (used for electricity and heating) is done in a way that guarantees real carbon savings and protects biodiversity. Only biofuels and bioliquids that comply with the criteria can receive government support or count towards national renewable energy targets.3 Because the additional demand for land may cause displacement effects, Green House Gas (GHG) emissions that might be caused by indirect land-use change must be included in the reporting of fuel providers and EU countries. This policy framework helps limit risks but further assessments will be needed to judge its effectiveness in terms of protecting biodiversity.

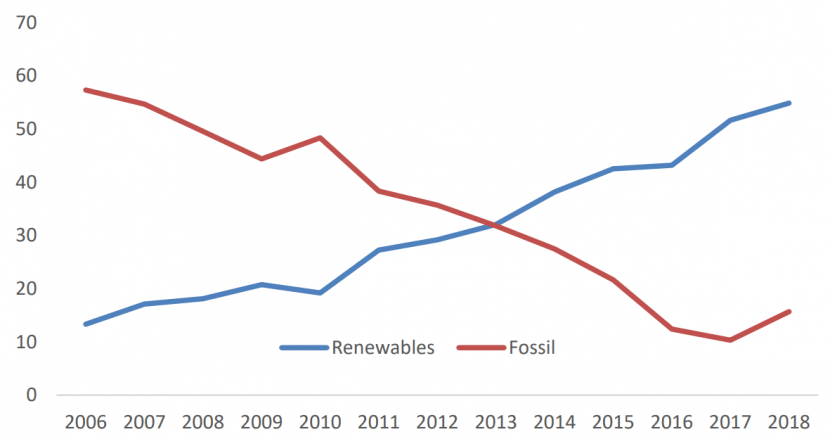

Renewable Electricity Generation versus Fossil Fuels – Scotland, 2006 – 2018. Source Scottish Government.

There has been a rapid increase in renewable electricity generation, mainly as a result of subsidies aimed at meeting other targets such as reducing our reliance on fossil fuels. The future contribution of bioenergy is likely to increase (Figure 3.1).4

| Priority Project | Relevance | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

PP4 – Investment in natural capital |

Businesses are more aware of their reliance on Scotland's natural capital, and more investment is being made in building natural capital. |

|

|

PP11 – Sustainable land management |

Promotion of measures to support biodiversity under CAP: sites demonstrating good practice aimed at supporting wildlife. |

|

A3 References end notes

3 European Commission Sustainability criteria

AICHI TARGET 4 - SUSTAINABLE CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION

By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.

![]() Sustainability is an integral part of Scotland’s economy and is enshrined within the Government Economic Strategy. Scotland is committed to being a low carbon economy and has ambitious targets to achieve this. However, not all indicators show confidently that we have achieved safe ecological limits.

Sustainability is an integral part of Scotland’s economy and is enshrined within the Government Economic Strategy. Scotland is committed to being a low carbon economy and has ambitious targets to achieve this. However, not all indicators show confidently that we have achieved safe ecological limits.

The Government Economic Strategy is aimed at all production sectors, including agriculture, forestry, fisheries, oil and gas, and renewables, as well as other forms of production such as electronics, retail and marketing, construction and tourism.1

National Indicators measuring environmental impact

The Scottish Government National Performance Framework includes five key measures of sustainable production and consumption:2

- Reduce Scotland's carbon footprint

- Increase the proportion of journeys to work made by public or active transport

- Reduce waste generated

- Increase renewable electricity production

- Improve the state of Scotland’s marine environment

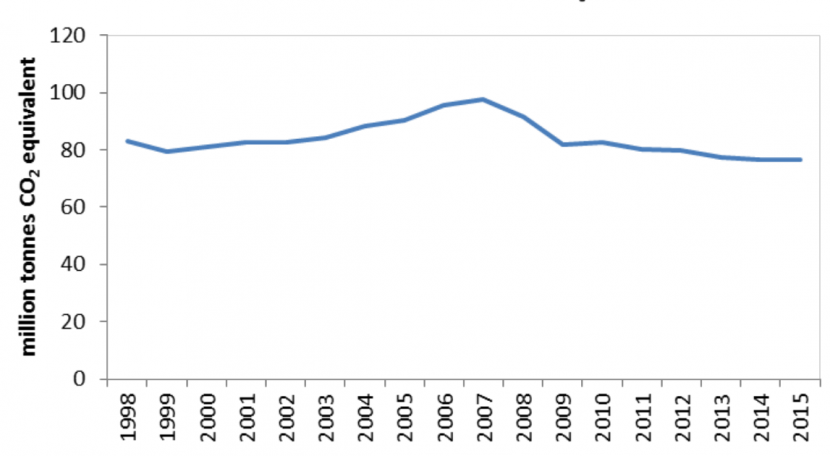

There has been reduction in Scotland’s carbon footprint since a peak in 2007. Scotland’s carbon footprint in 2015 was 76.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e). This is 23.3% lower than the 2007 levels (100.2 MtCO2e). An estimate of the ecological footprint was undertaken in 2006.3 This was stable but exceeded the target value.

Scotland's Carbon Footprint, 1998-2015. Source: Scottish Government.

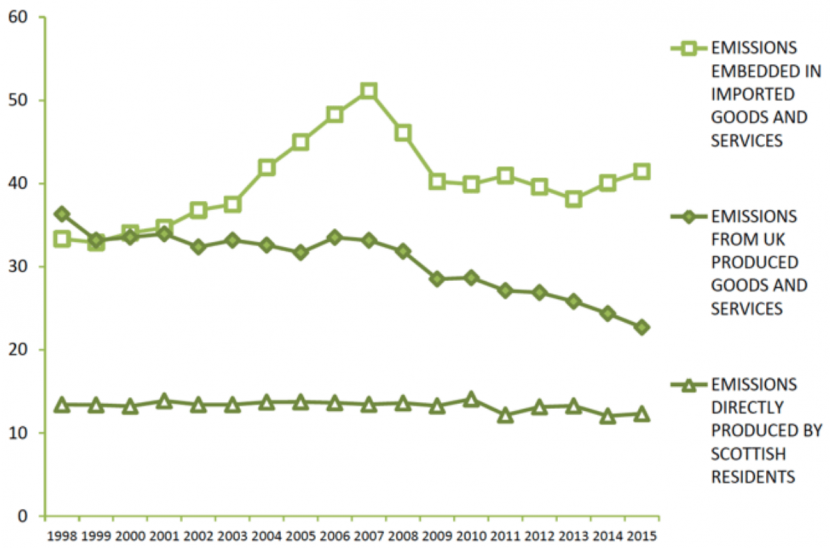

Scotland’s carbon footprint can be broke down into three main components from 1998 to 2015.

- Greenhouse gas emissions embedded in imported goods and services from overseas.These accounted for 54.2 per cent of Scotland's carbon footprint in 2015; up from 40.1per cent in 1998.

- Greenhouse gas emissions embedded in UK produced goods and services. Theseaccounted for 29.7 per cent of Scotland's carbon footprint in 2015; down from 43.7 percent in 1998.

- Greenhouse gas emissions directly produced by Scottish residents. These account for16.1 per cent of Scotland's carbon footprint in 2015; essentially equal to theiremissions share in 1998 at 16.2 per cent of total consumption-based emissions.

Scotland’s Carbon Footprint, by main component, 1998 to 2015. Values in MtCO2e. Source: Scottish Government.

Scotland’s Carbon Footprint, by main component, 1998 to 2015. Values in MtCO2e4

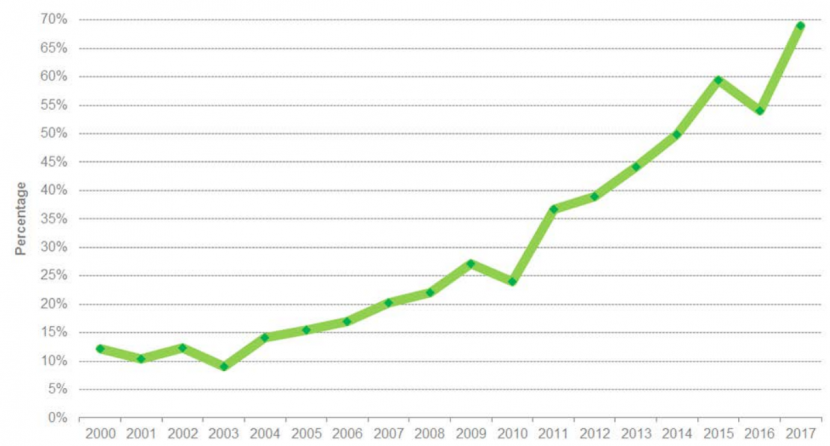

Over the decade there has been an increase in the amount of electricity generated in Scotland by renewable sources. In 2017, renewable electricity generation was equivalent to 70.1% of gross electricity consumption, an increase of 14.0 percentage points compared with 54.0% in 2016. This is over four times the level at the end of 2006.5 The reduction in renewable generation in 2016 can be attributed to falls in both hydro and wind generation due to reduced rainfall and wind speeds that year.

Electricity generated by renewables as a % of gross consumption, 2000 to 2017. Source: Scottish Government

Plans for sustainable consumption and production

A number of policies and strategies help guide action towards ensuring sustainability goals are being met. These include the Climate Change (Scotland) Act (2009),6 the Zero Waste Plan (2010),7 Low Carbon Scotland (2013),8 Safeguarding Scotland’s Resources (2013),9 A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland10 and Scotland’s National Marine Plan.11 The Carbon metric, produced by Zero Waste Scotland, shows how waste reduction and sustainable waste management can play a critical role in the fight against climate change.

Despite large annual fluctuations in waste generated, improved recycling and declining use of landfill continues to reduce the overall carbon impact of waste in Scotland, which has fallen 26% or 3.6MTCO2e since 2011.12

The impacts of Scotland’s consumption and the dependence on ecosystems overseas are poorly understood. More work is required to fill gaps in knowledge and explore measures to minimise Scotland’s global ecological footprint. SEPA have produced a strategy that aims to help reduce Scotland’s ecological footprint. The One Planet Prosperity Strategy sets a new ambitious direction that will help meet the targets required to reduce our ecological footprint.13

Although the use of natural resources is mentioned within the Circular Economic Strategy, it is unclear specifically what measures are being taken to ensure that impacts are being kept within safe ecological limits.

| Project | Relevance | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

PP4 – Investment in natural capital |

Businesses are more aware of their reliance on Scotland's natural capital, and more investment is being made in building natural capital. |

|

|

PP11 – Sustainable land management |

Promotion of measures to support biodiversity under CAP: sites demonstrating good practice aimed at supporting wildlife. |

|

A4 Reference end notes

1 Scottish Government - Scottish Annual Business Statistics 2018

2 Scottish Government - National Performance Framework

3 Scottish Government - Ecological footprint

4 Scottish Government - Scotland's carbon footprint 2015

5 Scottish Government - National Performance Framework

6 Scottish Government - Climate change

7 Scottish Government - Managing waste

8 A Low Carbon Economic Strategy for Scotland

9 Scottish Government - Safeguarding Scotland's resources - blueprint for a more resource-efficient and circular economy

10 Scottish Government - Making Things Last: a circular economy strategy for Scotland

11 Scottish Government - Scotland's National Marine Plan

12 Zero Waste Scotland - The carbon footprint of Scotland's Waste

13 SEPA - One Planet Prosperity

AICHI TARGET 5 - HABITAT LOSS HALVED OR REDUCED

By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

![]() Some of Scotland’s habitats have suffered degradation and losses through changes in land use and management. Targeted restoration is underway on peatland, woodland and freshwater habitats. Work is ongoing to improve protection of Priority Marine Features and the Scottish MPA network through implementing fisheries management measures The Habitat Map of Scotland provides baseline habitat data and will enable us, in time, to look at changes in Scotland’s habitats. The Ecosystem Health Indicators will improve our knowledge of habitat fragmentation.

Some of Scotland’s habitats have suffered degradation and losses through changes in land use and management. Targeted restoration is underway on peatland, woodland and freshwater habitats. Work is ongoing to improve protection of Priority Marine Features and the Scottish MPA network through implementing fisheries management measures The Habitat Map of Scotland provides baseline habitat data and will enable us, in time, to look at changes in Scotland’s habitats. The Ecosystem Health Indicators will improve our knowledge of habitat fragmentation.

Scotland’s peatlands, mountain landscapes, coastal cliffs and seas, machair and some of our woodland ecosystems are exceptional by European standards.1 However, degradation, losses and reduction of Scotland’s native habitats has been – and is being – caused by many pressures including land use intensification and modification; habitat fragmentation; overexploitation; over and under grazing;2 invasive non-native species (e.g. rhododendron)3 and wildlife diseases (e.g. Dutch elm disease). Climate change, particularly affecting montane, wetland and coastal habitats, and pollution have also impacted on our natural habitats.4,5

Habitat changes

The overall condition of notified habitats on protected sites in Scotland is stable6 with 78.9% of all designated features in favourable or recovering condition (see Aichi Target 11). The area of terrestrial land and inland water under site protection has remained approximately 23% between 2016 and 2019.7 The proportion of Scotland’s seas designated as Marine Protected Areas for nature conservation is increasing, reaching nearly 18% by mid-2019 with a commitment for further designation.7,8

2019 EU Habitats Directive Article 17 Scottish reporting – Scottish assessment of Overall trends in Conservation Status qualifier for 58 terrestrial and coastal habitats.

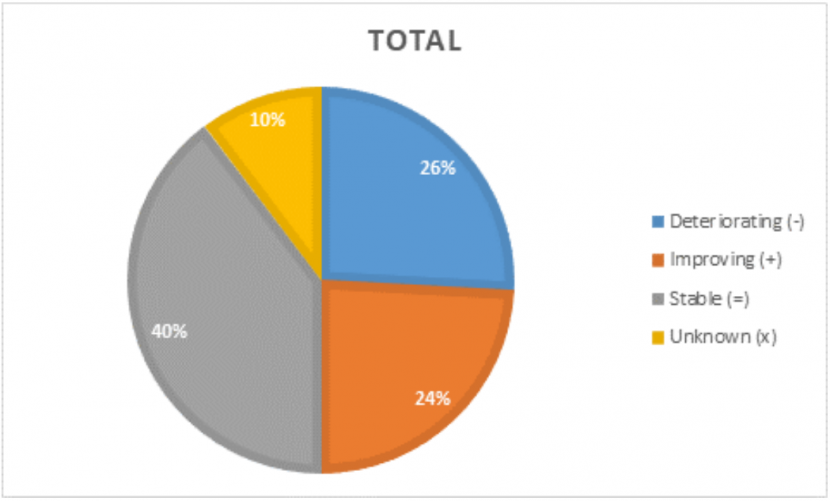

Trends in the conservation status of habitats of European importance in Scotland were 26% deteriorating, 24% improving, 40% stable and 10% unknown when last reported (Figure 5.1). Table 5.1 shows how one of the habitat groups had a declining conservation status “Coastal sand dunes and continental dunes. Three habitat groups showed an improving or stable status overall; “Freshwater”; “Raised Bogs, Mires and Fens” and “Rocky Habitats and Caves”. “Marine, coastal and halophytic habitats” have the largest number of unknown trends.

| Habitat Group | Deteriorating | Improving | Stable | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal sand dunes and continental dunes | 7 | 1 | 1 | n/a |

| Forests | n/a | 1 | 4 | n/a |

| Freshwater habitats | 1 | 1 | 4 | n/a |

| Marine, coastal and halophytic habitats | 2 | n/a | 3 | 6 |

| Natural and semi-natural grassland formations | 3 | 3 | 2 |

n/a |

| Raised bogs and mires and fens | 1 | 3 | 4 | n/a |

| Rocky habitats and caves | n/a | 3 | 3 | n/a |

| Scelerophyllous scrub (matorral) | n/a | n/a | 1 | n/a |

| Temperate heath and scrub | 1 | 2 | 1 | n/a |

Whilst the extent of semi-natural features reduced by 17%10 between 1947 and 1988, the assessment to 2007 was more positive, notably for expanding native woodland habitats.11 Scotland uses a variety of data sources to review habitat extent; we have the Habitat Map of Scotland12 which shows Level 1 EUNIS land cover13 and a UK marine EUNIS map.14 Work is continuing to produce higher level EUNIS maps for the Habitat Map of Scotland.15 These will provide current and up-to-date maps of the distribution of Scotland’s terrestrial and marine habitats, against which, with time, change may be measured. Work is being carried out by JNCC on “Making Earth Observation work for UK biodiversity conservation.”16 The recently published Ecosystem Health Indicators quantify habitat connectivity.17

Scotland's habitats and biodiversity

Completion of the Habitat Map of Scotland enables us to better assess the extent of habitats across Scotland at a broad scale. More information on habitat data may be found in Aichi Target 19 in this report.

Scotland’s woodland area had declined to 4.5% by the beginning of the 20th century.18 However, by the middle of the 20th century, Scotland’s woodland had increased rapidly mainly through the planting of fast growing conifer species. By the 1990’s more diverse woodland types were being planted.5 By 2013 the proportion of Scotland covered by forest increased to 18% of land area (1.4Mha).(Figure 5.1). Most of this area is dominated by introduced species, however, and the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland (NWSS) found that just over one fifth (0.3Mha, March 2011) of our woodland is native.19 The NWSS showed that 50% of native woods on the National Forest Estate were in good condition (compared to 46% of all native woodland), but the remaining 50% were in unfavourable condition with the largest factor being excessive herbivore impacts.2 Birds associated with woodlands show a long-term increase in abundance in Scotland,20 which may be associated with both condition and extent. However, at the last reporting round in 2013, all five of Scotland’s Habitats Directive Annex I forest habitat types have an overall conservation status of inadequate / declining (Table 5.1). Although Scotland’s State of the Environment Report, 2014 assessed the condition of our forests and woodlands for wildlife as “moderately good”, and that this condition is likely to continue with sustainable management (Figure 5.1) woodland habitats on protected sites have the second worst condition of all habitats, with only 65.2% of protected woodland features being in favourable condition.6

Around 18% of Scotland’s sea area is covered by Marine Protected Areas21 The most recent assessment of Scotland’s marine and coastal protected areas found that most protected features are in favourable condition at 98% (marine habitats) and 88% (coastal habitats) and 57% (marine mammals) (Figure 5.1). There have been declines in some inshore habitats with concerns for shallow and shelf subtidal sediments across Scotland.22 UK implementation of the UK Marine Strategy and implementation of policies in Scotland’s National Marine Plan (and in due course, Regional Marine Plans) are expected to contribute to better management of these areas. Many of our freshwater habitats are in relatively good condition (Figure 5.1). However, there are some declines in our freshwater vascular plant diversity,23 and invasive non-native species continue to negatively impact these habitats and remain extremely challenging to control.

Mountains and uplands define much of Scotland’s landscape (Figure 5.1). Upland breeding birds which depend on these habitats have shown a gradual long term decline in Scotland,20 but remedial action on protected sites is improving condition of some upland habitats (Figure 5.1). Peatlands cover more than 20% of Scotland’s area; it is estimated that in Scotland 70% of blanket bog and 90% of raised bog have been damaged.24 However, Scotland’s National Peatland Plan (2015) is working towards improving their protection and condition. This is covered in more detail under target 15. Biodiversity hotspot analysis in the uplands has shown the importance of biodiversity habitat mapping to enable the spatial targeting of management options.25 Grasslands have suffered declines in recent years: there have been significant declines in vascular plant diversity in grasslands;23 and, 23.9% of grassland protected features are in unfavourable condition (Figure 5.1).

Ecosystem Services and Health & Wellbeing

When in a healthy condition Scottish habitats can provide ecosystem services such as water, food, fuel and energy, storm protection, carbon storage, minerals, and flood control (Figure 5.1). Although Scotland’s Natural Capital Asset Index is static overall, the natural capital in woodland, freshwater, coast, and urban greenspace broad habitats increased between 2000 and 2010, and declined in moorland, grassland, and cropland.26 Scotland’s Land Use Strategy will enable us to think more strategically about land-use, and provide a framework for decision making to ensure that our land delivers multiple benefits, results in partnerships with nature, and links people with the land.27 A project in central Scotland is looking at the natural environment, climate change resilience and how these impact on our health and wellbeing, particularly in our more populated areas.28

| Project | Relevance | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

PP1 – Restoration of peatlands |

Ambitious peatland restoration programme underway, contributing to the EU15% degraded ecosystem restoration target. |

|

|

PP2 – Restoration of native woodlands |

Increase the amount of native woodland in good condition (upwards from 46% as identified by the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland). |

|

|

PP2 – Restoration of native woodlands |

3,000 to 5,000 ha new native woodland creation per year.

|

|

|

PP2 – Restoration of native woodlands |

Restore approximately 10,000 ha of native woodland into satisfactory condition in partnership with private woodland owners through Deer Management Plans. |

|

|

PP3 – Restoration of fresh waters |

Achieve agreed ecological water quality objectives under the Water Framework Directive of river and lake water bodies and to contribute to meeting conservation objectives (including Natura 2000 sites) through scoping improvements to physical modifications. |

|

|

PP11 – Sustainable land management |

Promotion of measures to support biodiversity under CAP: sites demonstrating good practice aimed at supporting wildlife. |

|

|

PP12 – Increase environmental status of our seas |

10% of Scotland’s seas to be incorporated in nature conservation Marine Protected Areas. |

|

A5 References end notes

1 Scottish Government - Scotland's biodiversity: a route map to 2020

2 NatureScot - Woodland condition

3 Scottish Forestry - Invasive rhododendron

5 Scottish Government - Marine litter

6 Nature Scot - Official statistics for protected sites - proportion in favourable condition

8 Scottish Government - Protecting Scotland's Future: the Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-2020

9 JNCC - Article 17 Habitats Directive Report 2019

10 NatureScot - Trend notes - Land cover change

11 CS - Countryside Survey: Scotland Results from 2007

12 Scottish Government -Habitat Map of Scotland

14 JNCC - Marine habitat data product: UKSeaMap

15 NatureScot - Habitat Map of Scotland

16 JNCC - Earth Observation

17 Scottish Government - Indicator 8: Connectivity

18 Scottish Government - Woodlands and forests

19 Scottish Forestry - Native Woodland Survey of Scotland (NWSS)

20 NatureScot - Official statistics for Terrestrial breeding birds

21 Scottish Government - Marine Protected Area Network - 2018 Report to the Scottish Parliament

22 Scottish Government - Scotland's Marine Atlas: Information for The National Marine Plan

24 NatureScot - Scotland's National Peatland Plan: Working for our future

25 Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum - Making the Most of Biodiversity Data

26 NatureScot- Natural Capital Asset Index

27 Scottish Government - Land Use Strategy

AICHI TARGET 6 - SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT - MARINE

By 2020, all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

![]() Considerable progress has been made in ensuring fish, invertebrate and aquatic plants are harvested sustainably and in line with Scottish and European legal frameworks. The latest fishery stock assessments show that they are at Good Environmental Status (GES) for the Greater North Sea ecoregion. In the Celtic Seas ecoregion, a number of stocks have very low biomasses and are not sustainable. The development of Scotland’s National Marine Plan,1 and Aquaculture, Seaweed Harvesting and Fisheries Strategies along with the UK Marine Strategy are all helping to focus efforts towards sustainable management in the marine environment.

Considerable progress has been made in ensuring fish, invertebrate and aquatic plants are harvested sustainably and in line with Scottish and European legal frameworks. The latest fishery stock assessments show that they are at Good Environmental Status (GES) for the Greater North Sea ecoregion. In the Celtic Seas ecoregion, a number of stocks have very low biomasses and are not sustainable. The development of Scotland’s National Marine Plan,1 and Aquaculture, Seaweed Harvesting and Fisheries Strategies along with the UK Marine Strategy are all helping to focus efforts towards sustainable management in the marine environment.

Fishery catch statistics are collated annually by the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES). These provide a measure on sustainable use and inform fishery quotas and policy decisions. The latest fishery stock assessments show that many are being harvested at sustainable levels, with biomass increasing in the North Sea.2 In the North Western Waters, the situation is less positive, with a number of stocks being harvested at unsustainable levels and having very low biomasses.

In 2016, of 19 ‘key’ Scottish stocks 13 (70%) were fished at or very close to being fished at the Maximum Sustainable Yield; 5 in the North Sea, 6 in the west of Scotland and 2 Northern Shelf stocks. Biomass is also steadily improving with 14 of these stocks (74%) above biomass action points for fisheries management (MSY Btrigger). For comparison in 2015, 11 stocks were fished at or very near MSY (almost 60%). The setting of Total Allowable Catches (TAC) is done at an international level for fish stocks which are widely dispersed and often fished by many countries. As such Scotland does not have complete control over what is a very internationally managed process. An outcome of fisheries negotiations at the end of 2017 is that for 2018, nine of the thirteen stocks (69%) by which Scottish Government measures its sustainability performance have had their Total Allowable Catches (TACs) set in line with the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) for 2018 - an increase from 62% in 2017.

Levels of fishing in the past have meant that several fish species in both ecoregions are now on the OSPAR threatened and declining species list, including spurdog, the common skate complex, angel shark, porbeagle and some deep-water sharks.3 Assessments by the OSPAR Commission in their Intermediate Assessment 20174 (across sea areas larger than Scotland (but including data from Scotland) indicate that fisheries management is starting to have a positive impact on fish communities, with for example the proportion of large fish (more susceptible to fishing mortality) in the demersal community improving and set to continue as long as current pressures, including wider environmental pressures, do not increase.

The fishery for Nephrops (known as Norway lobster, scampi, Dublin Bay prawn or langoustine) in Scottish waters has developed from landings of a few tonnes in the early 1960s to over 30,000 tonnes in the mid-2000s. Landings in 2018 of just over 18,000 tonnes had a first sale value of approximately £63 million making Nephrops the second most valuable species landed into Scotland by Scottish vessels (after mackerel).5 The latest shellfish stock assessment for Scotland shows variation between the different fishing grounds. In some stocks abundance has declined to around the Maximum Sustainable Yield Biomass trigger, the level where management actions may be needed.3

Fisheries managers are also working to implement the commitment to end discarding in European waters which was in the reformed Common Fisheries Policy. This should lead to healthier fish stocks in the longer term as mortality from fishing can be more accurately controlled. Implementing this commitment does create significant management challenges for all EU Member States and will require substantial changes in the fishing operations which will be demanding to deliver within the timescales contained in the legislation.

Scotland’s National Marine Plan6 states “Achieving a sustainable economy, promoting good governance and using sound science responsibly are essential to the creation and maintenance of a strong, healthy and just society capable of living within environmental limits.” The plan sets out strategic policies for the sustainable development of Scotland’s marine resources. Aquaculture and fisheries have sustainable management strategies in place. While the strategies do not explicitly explain how they are linked to biodiversity, they do state that operations should have due regard to the environment.

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) places further emphasis on ensuring that Scotland’s seas are healthy, productive and safeguarded for use by future generations.7

A new indicator for tracking the status of Scotland’s commercial fish stocks is being developed which will be available for the final 2020 Aichi report. The proposed indicator will measure the extent to which the fishing mortality (i.e. rate of fish captured – landings plus discards) for different key commercial stocks is in line with sustainability thresholds as defined by relevant MSY reference points. The current policy objective, as required by the UN following the 2002 Johannesburg Declaration, is to reduce fishing mortality for each key commercial stock to a level below the respective MSY reference point.

The Scottish Government Programme for Government 2019-208 provides commitments to marine work including a sustainable marine economy and environment, noting that “as well as providing a habitat for many species, our marine environment plays an important role in helping to absorb carbon”.

| Priority Projects | Relevance | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

PP12 – Increase environmental status of our seas |

10% of Scotland’s seas to be incorporated in nature conservation Marine Protected Areas. |

|

A6 References end notes

1Scottish Government - National marine planning

2 Scottish Government - Scottish Sea Fisheries statistics 2018

3 ICES, 2017a. Greater North Sea Ecoregion – Fisheries Overview. ICES Report

4 Ospar Assessment Portal - Intermediate Assessment 2017

5 Scottish Government - Scottish Sea Fisheries Statistics 2018

6 Scottish Government - Scotland's National Marine Plan

AICHI TARGET 7 - SUSTAINABLE, AGRICULTURE, AQUACULTURE AND FORESTRY

By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

![]() Agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are important industries in Scotland. Considerable progress has been made in developing policies and strategies that will help achieve and support sustainability targets by 2020.

Agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are important industries in Scotland. Considerable progress has been made in developing policies and strategies that will help achieve and support sustainability targets by 2020.

Agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are widespread land uses throughout Scotland. Sustainable management benefits from a planned approach and the second Land Use Strategy for Scotland builds upon the central framework of the first strategy. The second strategy identifies priority activities leading up to 2021 and where ecosystem services are considered as natural capital assets which require an ecosystem approach to management.1 Although primarily focussed on food and fibre production, farmland includes some of Scotland’s most biodiverse areas. Aquaculture can be broadly split by marine and freshwater.2 Marine aquaculture is largely sited along the west coast and Northern Isles. Freshwater aquaculture shows a more widespread distribution across Scotland.

Sustainability Certification Schemes

Woodland

All woodlands owned and managed by Forestry and Land Scotland meet the UK Woodland Assurance Standard (UKWAS).3 The UKWAS Steering Group works closely with the internationally recognised certification schemes Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) in the UK to ensure continued alignment of the UKWAS standard with their scheme requirements. In 2007 the working arrangements were formalised by the means of Concordats between the UKWAS Steering Group and FSC UK and PEFC UK setting out each party’s respective role.4 In addition to this timber and wood suppliers are encouraged to only use and promote products coming from FSC (or equivalent) sources. A Fourth Edition of the UKWAS was agreed by stakeholders in 2016 and adopted for use in FSC and PEFC certification from 1 April 2018.4

Aquaculture

Alongside the existing sustainability drivers through the consent process, accreditation schemes that promote sustainable practices and are used currently by industry include the Aquaculture Sustainability Council (ASC) and the Soil Association Organic Certification Scheme. In addition the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification scheme5 principles and criteria for sustainable fishing is a standard ensuring that a fishery is well managed and responsibly harvested to sustain the target fishier and the surrounding marine environment. Certification to this standard demonstrates commitment to sustainable practices and results in the recognition in the market.

Agriculture

Certification exists for organic farms in Scotland. Under Organic Certification schemes farmers need to meet a prescribed set of standards. Approximately two percent of Scottish farmland was certified as organic in 2017.6 In addition farms in receipt of the Single Farm Payment Subsidy must meet Cross Compliance requirements, which provide some environmental protection for example by protecting hedges.

High Nature Value Farming and Forestry

High Nature Value (HNV) farming and forestry has been mapped for Scotland. This provides an indication of important areas for biodiversity. These are reported as an Official Statistic for Scotland. The findings show that the total area under HNV farming was estimated at 2,432,000 hectares (44% of the utilised agricultural area). The Highlands made up the largest area for HNV farming. The area of woodland determined to be of HNV status was estimated to be 575,000 hectares.7

Fertiliser Use

Fertiliser use in Scotland has declined overall since 1986, and in particular from around 2000 suggesting improved agricultural practices. Fertilisers contain nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, which improve plant growth and crop yields. However, the inappropriate or mistimed use of fertilisers may cause nutrient enrichment and eutrophication of waters. The application rate of nitrogen fell from 127 kg/ha in 2001 to 89 kg/ha in 2015 and the application rate of potash fell from 49 kg/ha to 34 kg/ha over the same period. The phosphate application rate remained relatively stable at around 45 kg/ha until 1997, before declining steadily to 27 kg/ha in 2015.8

Pesticide and Rodenticide Use

Pesticides and biocides are used to control pests. They are widely used in the countryside and have been linked to declines in the diversity and abundance of invertebrates and plants. There is also evidence that they have adversely affected farmland birds through removal of food resources. Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture (SASA) routinely collect data on the usage of pesticides and biocides and monitor their impact. In 2018 pesticide use on arable crops grown in Scotland dropped by four percent compared to 2016.9 Ninety eight percent of arable crops and 93% of soft crops in Scotland were treated with a pesticide in 2018. The pesticide application levels in 2018 were also lower than those recorded in 2014 and 2012.

A reduction in the use of rodenticides was recorded in 2018 compared to 2016. Fifty five percent of arable farms applied rodenticides in 2018 compared to 78% in 2016. The quantity of rodenticide bait applied was approximately 47% lower in 2018 compared to 2016. This reduction may have been influenced by the introduction of an industry led rodenticide stewardship scheme in 2015.

However, long-term turnover in the identity of pesticide and biocide products used in the wider countryside, coupled with a lack of regulation of their use based on knowledge of their wider environmental impacts, means that likely impact cannot easily be understood based on simple usage statistics. For example, increasing evidence suggests that the environmental impacts of a new generation of pesticides, neonicotinoids, now in widespread global use, are high.10

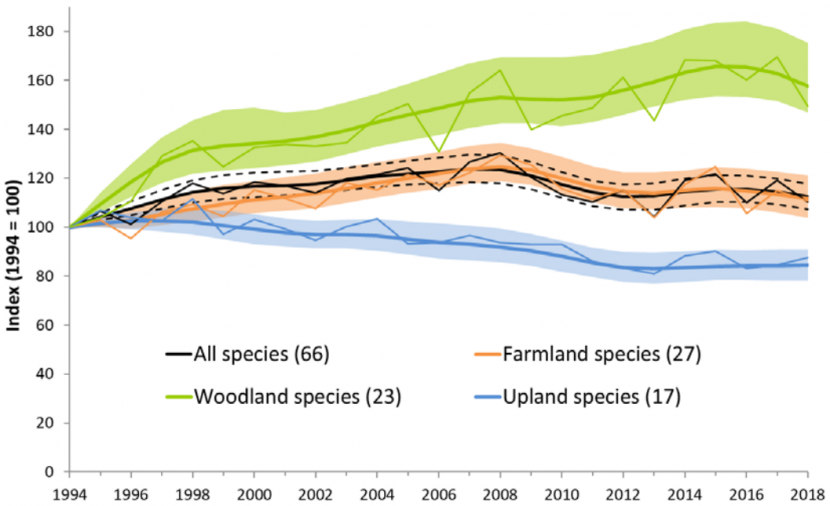

Breeding Birds

The Official Statistic for Terrestrial Breeding Birds provides a high level measure on biodiversity trends for Scotland. As of 2016 the trend of breeding woodland birds has increased significantly by 69% since 1994. Farmland birds have increased by 23%. Upland birds, in contrast declined by 17%. Farming in Scotland is less intensive than many other parts of the UK and there are agri-environment measures in place to encourage wildlife, such as corn bunting.

Policies, Strategies and Industry Initiatives