Serpulid reefs

Though found as individuals in almost all marine environments, serpulid tubeworms form ‘reefs’ in only a few special places.

The organ-pipe or serpulid worm (Serpula vermicularis) is a beautiful marine tubeworm with a showy crown of feathery tentacles. Bright red, pink and orange, these contrast with its hard white tube. Individual organ-pipe worms occur almost worldwide, but only rarely grow together as ‘reefs’.

Serpulid reefs are a Priority Marine Feature in Scotland’s seas.

Serpulid reefs are bush-like structures made up of hundreds of individual worm tubes, each about 5mm in diameter and up to 150mm long. The world’s largest area of serpulid reefs is in Scotland, in Loch Creran. The reefs here, which grow at depths of 6 to 10m, are up to 75cm high and 1m across.

Serpulid reefs form a high-rise home for a host of other animals:

- bright orange sponges with long tendrils are particularly abundant on some colonies

- sea firs, sea squirts and seaweeds also attach to the tubes

- spider crabs, squat lobsters, hermit crabs, starfish, small urchins and marine snails shelter or hunt on the colony

- brittlestars and terebellid worms shelter deep within reefs

Organ-pipe worms are highly sensitive to light and vibrations. When disturbed, a worm will rapidly retract its tentacles and close the entrance to its tube with a plug. A reef will suddenly transform from showing its bright red and orange flower-like structures to just the pure white of the tubes.

Information on where serpulid reefs are found is at Scotland’s National Marine Plan Interactive (NMPi).

The organ-pipe worm (Serpula vermicularis) is a beautiful marine tubeworm with a showy crown of colourful feathery tentacles.

Cycle of growth and collapse

Living reefs were once found in Linne Mhuirich, an inlet by Loch Sween, but these died out in the 1990s for reasons still not understood.

Small groups of organ-pipe worms were found in 2006 in Loch Teacuis – now part of the Loch Sunart Marine Protected Area. It was hoped that these would grow larger and develop into full reefs – live serpulid material growing on dead worm tubes. But more recent reports suggest that the Loch Teacuis aggregations have died back and no longer cover such a wide area of the seabed.

We now believe that serpulid reefs go through natural cycles of growth and collapse. Individual structures eventually get so large that they can no longer support themselves. Fallen worm tubes can continue to grow up from the seabed. But if they die, the dead tubes form new habitat for the settlement of serpulid larvae and the reef continues to grow and spread.

Reef collapse in Loch Creran appears to have been made worse by an increase in storm events – for example, greater amounts of collapsed reef were reported in 2015.

A dogfish Investigates a serpulid reef in Loch Creran

Threats to serpulid reefs

Serpulid reefs are very fragile and extremely vulnerable to mechanical disturbance from, for example:

- mobile and static fishing gear

- anchors and mooring chains

- fins used by divers

They may also be sensitive to water quality and changes in water flow. More information on the sensitivities of serpulid reefs can be found at Scotland’s Feature Activity Sensitivity Tool (FeAST).

Protection of serpulid reefs

Serpulid reefs are a Priority Marine Feature and a UK BAP habitat.

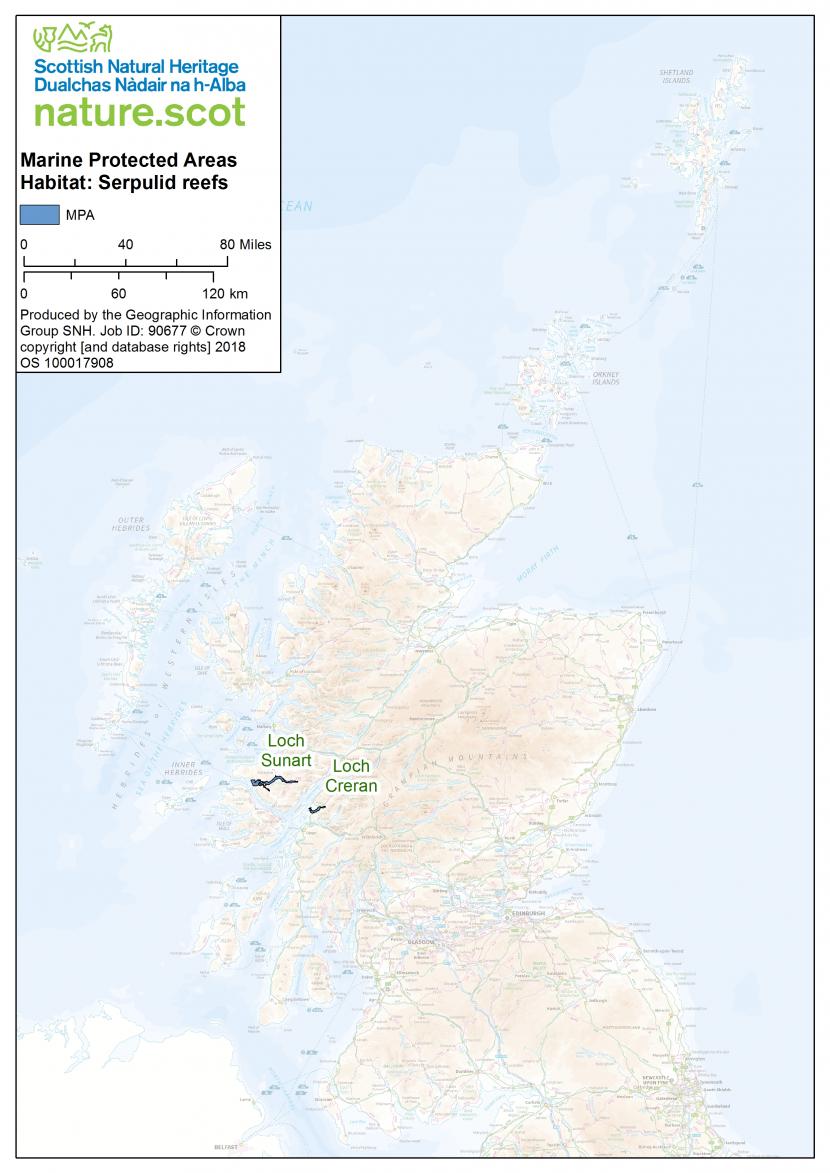

Serpulid reefs are protected in both locations they are known to occur in Scotland by Marine Protected Areas shown in the map below.

The Loch Creran SAC management plan includes:

- guidance for private and commercial vessels on locating moorings away from the serpulid reef

- guides to anchoring and diving safely in the loch

After it had been designated as Loch Creran Marine Protected Area in 2015, the site was closed to mobile fishing gear. Static gear fishing is allowed but is restricted to areas with no biogenic reefs.

View The Inshore Fishing (Prohibition of Fishing and Fishing Methods) (Scotland) Order 2015.