Biodiversity Route Map to 2020 - Final Report

Published: 2022

Foreword

The Climate COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh and Biodiversity COP15 in Montreal have concluded. Now is the time to focus sharply on the nature-climate crisis.

Over the past nine years, since the 2020 Challenge for Scotland’s Biodiversity was published, great effort has been devoted to hundreds of biodiversity projects all geared to halting the loss of important habitats and wildlife, and raising awareness of the plight of nature.

Published in 2015, Scotland’s biodiversity: a route map to 2020 sets out a programme of action-orientated work to support biodiversity and its benefits for people. I’m delighted to see that a huge amount of work has been undertaken, and in the pages ahead there is a real richness in the range of work carried out, and in its reach and impact. This is the final report from this phase of biodiversity work. Responding to the challenge has prompted tremendous effort, and I warmly thank the many organisations and literally thousands of people who have made this happen.

Looking back to when the 2020 Challenge was published, I think it is fair to say we earnestly believed we could protect and indeed restore biodiversity across Scotland’s land and seas, and connect many more people with nature. Well, we gave it a good go, but with time we have come to realise that not just here, but globally, we have not done enough.

With the declaration of a climate emergency here in Scotland, in May 2019, and recognition of the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss in December 2020, we need to transform policy, engagement and support for nature. During COP15 the Scottish Government published a draft 25-year biodiversity strategy. The strategy and its ambitious Delivery Plan will set out what needs to be done at scale to halt the loss of biodiversity by 2030, and sustain wide-scale nature restoration by 2045. Our Scottish Government-funded £65 million Nature Restoration Fund, launched in July 2021, marks the enormity of the support needed, as do commitments to peatland restoration and woodland planting. In total £500mn has been committed by the Scottish Government in this Parliamentary Session.

Looking ahead, I believe not millions but billions of pounds from a wide range of land and sea stewards and users will be needed. The rewards of such investment will be repaid in ways we can barely imagine now – regenerative sea and land use reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere to limit the impacts of global warming, and placing nature at the heart of our lives and livelihoods.

This report reveals the dividends of inspired work and great energy with relatively little resourcing. We can be confident then, that when we act we will have a positive impact. I believe that thanks to the action we all took in the past nine years, we have a springboard to galvanising a Scotland-wide mass movement committed to restoring Scotland’s nature, and especially its living species, habitats and ecosystems. In short, to save our nature.

Dr Mike Cantlay OBE

Chairman, NatureScot

Executive Summary

This is the final report on the Scotland’s Biodiversity: a Route Map to 2020 (the Route Map) and its ambitious programme of actions to make Scotland a better place for biodiversity and people by 2020. The report covers the whole period of the Route Map from 2015 - 2020 and includes a number of updates from 2021 and 2022. It illustrates the tremendous efforts from partners and highlights many of their successes in delivering the actions set out in the Route Map, while acknowledging the challenges ahead.

Published in 2015 the Route Map included 12 Priority Projects (PPs) underpinned by 79 Actions and 14 Targets. The focus of the Route Map was on large-scale collaborative activities. Under Priority Project 1, restoration of peatlands, the Peatland Action Project has put over 35,000 hectares (ha) of peatland on the road to restoration, a significant achievement although still well below the 25,000 ha per annum required to achieve their 2030 target.

Since 2013/14 Scottish Forestry has supported the establishment of over 31,000 ha of new native woodland; an average of around 3,500 ha per year thus meeting the target for the amount of new native woodland created. Elsewhere within Priority Project 2, restoration of native woodland, over 18,000 ha of planted ancient woodland sites are under restoration management on land managed by Forestry and Land Scotland. Across Scotland, however, only 68.2% of protected woodland features are in ‘favourable’ or ‘recovering condition’. Herbivore impacts, particularly from deer, have been highlighted, over decades, as a serious issue in relation to native woodland condition. The Route Map target to work in partnership with private woodland owners through Deer Management Plans to restore approximately 10,000 ha of native woodland to satisfactory condition has not been met.

In 2018 a total of 65.7% of Scotland’s surface water and groundwater bodies were assessed as being in a good or better condition. This was an improvement in the condition of water bodies since 2015 and sits alongside other improvements in Scotland’s water environment resulting from actions under Priority Project 3, restoration of freshwaters. These include substantial actions to control riparian invasive non-native species, river restoration for freshwater pearl mussel populations, actions to reduce diffuse pollution and river restoration projects at catchment scale.

There has been a lot of activity under Priority Project 4, securing economic and social benefits from, and investment in, natural capital. Scotland was the first country in the world to publish a Natural Capital Asset Index, which is now a national indicator within our National Performance Framework, acting as an economic indicator of sustainable development. Scotland's National Strategy for Economic Transformation further embeds natural capital as underpinning our prosperity, health and a wellbeing economy. New opportunities for increased funding and investment in natural capital and green infrastructure are being taken forward by the Scottish Conservation Finance Pioneers group, while the Peatland and Woodland Carbon Codes are helping to develop markets in the drive for Net Zero.

Awareness of, and access to, walking and cycling routes have both greatly increased through actions under Priority Project 5, more people experiencing and enjoying nature. Green infrastructure projects have created and improved multifunctional green infrastructure in many deprived areas of urban Scotland, whilst the Natural and Cultural Heritage Fund is enabling more people to enjoy and experience nature across remote and rural areas. National and local participation campaigns, events, activities and outreach work targeted at under-represented groups, volunteers and local communities have all helped people to connect with nature.

Under Priority Project 6, taking learning outdoors, the Learning in Local Greenspace project has helped schools serving Scotland’s 20% most disadvantaged communities to access and, where necessary, develop and improve their local greenspaces. Other projects have helped to strengthen and support teachers’ outdoor learning practice.

Four Green Health Partnerships and an NHS Greenspace Demonstration Project are part of developing Scotland’s natural health service (Priority Project 7). They have delivered greenspace infrastructure improvements at 13 sites across ten mainland Health Boards, and have helped to demonstrate and promote the physical, mental and social health benefits of participating in outdoor activity and of increased contact with nature.

The Priority Project 8, protected areas in good condition target of 80.4% of natural features on protected areas in favourable or recovering status was achieved in March 2016. That proportion has since declined, however, to below the target and stood at 77.9% in March 2022.

The target of delivering six high profile wildlife conservation projects was exceeded under Priority Project 9, conservation of priority species and as a result there are now more golden eagles in south Scotland than at any time recorded in the last two hundred years and European storm petrels have bred successfully on the Shiant islands where previously rat predation prevented this. The main threat to the rare tufted saxifrage, however, appears to be from a warming climate and consequently there is little that practical conservation actions can do to protect this species other than to ensure that its current habitat remains healthy.

The EcoCo Life project improved habitat connectivity at 45 sites across central Scotland, improving ecological connection, Priority Project 10. A habitat connectivity map has been developed to help target actions to reconnect fragmented habitat networks and steer actions towards creating new habitat in central Scotland. Data on habitat connectivity have been used by partners to help develop nature networks in central Scotland, although much remains to be done to increase the resilience of biodiversity to climate change.

Sustainable land management, Priority Project 11, has been supported by £214 million funding through the Scottish Rural Development Programme’s Agri-Environment Climate Scheme (AECS). By May 2022 the Wildlife Estates Scotland initiative was generating increased interest amongst land managers; 59 estates are fully accredited with another 25 in the process of application. The total area of accredited estates is over half a million hectares.

The Scottish Protected Area network now include 37% of Scotland’s seas, which will make a significant contribution to increasing the environmental status of our seas, Priority Project 12. In 2017, the Scottish Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) monitoring strategy was published and is used to guide work carried out by statutory bodies and others to improve our understanding of the status of MPAs.

This Route Map Report provides further detail on all of the above and more, including the substantial amount of supporting work that helps to underpin biodiversity outcomes. It illustrates the tremendous efforts from partners and demonstrates their many successes in tackling the actions set out in the Route Map, while acknowledging the challenges encountered and our growing understanding that despite all these efforts biodiversity continues to decline. The transformational changes needed to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity in Scotland are set out in Scotland's draft biodiversity strategy.

Introduction

This is the final report on the Scotland’s Biodiversity: a Route Map to 2020 (the Route Map) and its ambitious programme of actions to make Scotland a better place for biodiversity and people by 2020. The report covers the whole period of the Route Map from 2015 - 2020 and includes a number of updates from 2021 and 2022. It illustrates the tremendous efforts from partners and highlights many of their successes in delivering actions set out in the Route Map, while acknowledging the challenges ahead.

Published in 2015 the Route Map included 12 Priority Projects (PPs) underpinned by 79 Actions and 14 Targets. Responsibility for each Action and Target rested with a lead organisation. The focus of the Route Map was on large-scale collaborative activities. Lead organisations contributed to a series of annual progress reports. For the last full and cumulative account of progress please refer to the Progress Report for 2017-19. Many Route Map Actions were ‘start and finish’ projects, whereas others continued beyond 2020. This report provides an overview of each Priority Project with each individual action and target highlighted in bold font.

The Covid-19 pandemic delayed development of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity’s new Global Biodiversity Framework and consequently the new Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (SBS). In the interim the Scottish Government published the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Post-2020: A Statement of Intent, which extended the principles and projects of the Route Map until it is replaced by the new strategy and delivery plan.

Lochgilphead High School 3rd year pupils on a Snapberry photography workshop at Taynish National Nature Reserve.

Priority Project 1 - Restoration of peatlands

Aim

This Priority Project included a target for an ambitious peatland restoration programme contributing to target two of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020, which aimed to maintain and restore ecosystems and their services by including green infrastructure in spatial planning and restoring at least 15 % of degraded ecosystems by 2020.

Scotland’s National Peatland Plan: Working for our future was published in 2015. This was developed in response to the commitment in the Infrastructure Investment Plan for Scotland to provide a 10 year £250 million Programme for Government (PfG) commitment. Reflecting the increasing recognition of peatland in delivering multiple benefits, the government intend to develop and deliver a new vision and strategy for Scottish peatlands, updating and replacing the National Peatland Plan.

Funding from Scottish Government through the Peatland ACTION Project, a partnership of NatureScot, the two National Parks, Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) and Scottish Water has put over 35,000 hectares (ha) of peatland on the road to restoration since 2012. Unfortunately, this has been achieved at a rate of under 6,000 ha per annum, well below the 25,000 ha per annum required to achieve the 2030 target. Thus, given the importance of functioning peatlands to the climate and biodiversity emergencies, new initiatives are being established to increase the demand for restoration, increase the design/pipeline of restoration projects and increase/upskill the workforce to deliver the projects. These initiatives include increasing use of the Peatland Code, with investors using it to generate carbon credits and draw in private finance. The Peatland Code is discussed under Priority Project 4.

One example of a project delivering peatland restoration is the Flows to the Future Project. Led by the Peatland Partnership and funded by the National Heritage Lottery Fund this major project took place from 2014 to 2019 and restored large areas of blanket bog in the heart of the Flow Country that had been damaged by forestry planting. The £11.3 million invested achieved a considerable amount, including: non-native trees removed from 837 ha of deep peat; 564 ha cleared of regenerating non-native conifers; forestry furrows and drains blocked over 1,747 ha; management and funding advice provided on 75,000 ha. Public engagement was facilitated by building a field centre for operations and researchers, installing a new lookout tower over the Forsinard peatland, installing exhibitions at Strathnaver Museum and Caithness Horizons in Thurso, and by providing outdoor visitor interpretation at various sites throughout the Flows.

Priority Project 2 - Restoration of native woodlands

Aim

This Priority Project included three targets: increase the amount of native woodland in good condition; create new native woodland; and restore native woodland through improved deer management.

The Route Map sought to increase the amount of all native woodlands in good condition from a baseline of 46%, as identified in the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland in 2014. This survey has not been repeated, so a direct comparison cannot be made; formal, repeated condition monitoring of designated sites, however, is available and informative.

Scottish Forestry and NatureScot worked together targeting designated sites’ protected woodland features that had been monitored and assigned to the ‘unfavourable condition’ category. The percentage of protected woodland features in ‘favourable’ or ‘recovering condition’ categories at 31st March 2022 was 68.2%, a drop from the peak of 69.1% achieved in 2016. Scottish Forestry and NatureScot continue to work together to target woodland features in unfavourable condition.

Conservation management on the National Forest Estate targeted towards protected areas means that 92.5% of woodland features on the National Forest Estate are in favourable condition. Deer continue to be the main threat to woodland features. Controlling deer remains a challenge, particularly where the National Forest Estate adjoins estates with different objectives. A number of key landscapes have recently been recommended by Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) to NatureScot as ‘focus areas’ for the Deer Working Group Operational Delivery Workstream. FLS is also working closely with partners in the Alliance for Scotland’s Rainforest (including NatureScot and Scottish Forestry) to identify priority areas to control invasive rhododendron at a landscape scale. In most cases, these priority areas support nationally or internationally important woodland conservation features.

Since the Route Map’s publication in 2015 FLS has carried out notable conservation action and research for a range of endangered species, including capercaillie, raptors, red squirrel, freshwater pearl mussel and pine hoverfly. In 2020 over 18,000 ha of planted ancient woodland sites (PAWS) were under restoration management on land managed by FLS. FLS has undertaken preparatory work to accelerate delivery in the rainforest zone and across Caledonian pinewood areas. Biodiversity has been enhanced significantly on 18 new landholdings on the National Forest Estate, including over 1,300 hectares of woodland creation on former opencast coal sites.

New native woodlands have been created, mainly with support from the Scottish Rural Development Programme (SRDP), which includes the Forestry Grant Scheme, meeting the Route Map target of 3,000 - 5,000 ha per year. Since 2013/14 Scottish Forestry has supported the establishment of 31,544 ha of new native woodland; an average of 3,504 ha per year. In 2021/22 at least 4,362 hectares were native species. A Fairer, Greener Scotland: Programme for Government 2021-22 set a new increased target for native woodland creation of at least 4,000 ha per annum. Scottish Forestry will assist through the Forestry Grant Scheme, for example, establishing new target rates for Small Native Woodlands within Crofting Communities and the Clyde Climate Forest, designed to prioritise native woodland creation options. On the National Forest Estate new native woodland continues to be established.

During 2021/22 over 200 ha of new native woodland was planted.

Red deer grazing in a commercial forestry plantation. Forsinard Flows National Nature Reserve

Herbivore impacts, particularly from deer, have been highlighted, over decades, as a serious issue in relation to native woodland condition. Covering more than 3 million ha, 48 upland Deer Management Plans (DMP) are in place to guide the management of deer in order to help retain existing native woodland cover and improve woodland condition. The Route Map target of approximately 10,000 ha of native woodland being restored into satisfactory condition, in partnership with private woodland owners through DMPs, was not met. Further work with Deer Management Groups, following publication of the Scottish Government’s response to the Deer Working Group Report, is directed at improving habitat condition. Data from the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland provide the basis for habitat condition assessments in most DMPs. The SRDP Forestry Grant Scheme is the primary incentive-based mechanism for native woodland restoration. This requires information on herbivore management approaches and related measures, to help ensure improvements.

In March 2021 the Scottish Government Response to the Report from the Deer Working Group on 'The management of wild deer in Scotland' was published. This included a number of proposals to modernise deer legislation, and major work needed to reduce deer impacts on biodiversity and other interests. The Cabinet Secretary’s Foreword to the response noted: “The twin climate and biodiversity crises require a much greater urgency to our efforts to ensure sustainable deer management and we must recognise that more can and must be done to better realise our ambitious targets on vital issues such as forest regeneration, woodland creation, peatland restoration and habitat improvement.”

EU LIFE funding was not secured for either Atlantic oakwood or Atlantic hazelwood restoration, however, the Alliance for Scotland’s Rainforest has developed an ambitious ‘Saving Scotland’s Rainforests Action Plan’ to be implemented beyond 2020. This is important work; not only does our rainforest sequester carbon, it is considered by many to be a jewel in Scotland’s biodiversity crown. The Alliance is a group of over 20 Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), statutory bodies and other organisations working together to help Scotland’s rainforest thrive again. In November 2021 Environment Minister Mairi McAllan announced that Scotland’s rainforest will be restored and expanded as a natural solution to the climate emergency.

Areas of focus for the Alliance include establishing two landscape-scale projects to improve and expand rainforest sites. In 2020 RSPB Scotland led on the submission of an EU LIFE concept application for a £3.8M landscape-scale ‘Saving Morvern’s Rainforest’ project. The initial stage bid was successful, however, the full application did not secure EU LIFE funding. The project has nonetheless secured funding support from private donors, trusts and grants, including £180,000 from Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, and continues to seek the remaining funds.

Priority Project 3 - Restoration of freshwaters

Aim

The Route Map set a target that Scotland should achieve agreed ecological water quality objectives under the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) for river and lake water bodies, and contribute to meeting conservation objectives through scoping improvements to physical modifications.

For the implementation of the WFD there are 3,652 river, loch, estuary, coastal water and groundwater bodies in Scotland, and an additional 1,526 protected areas associated with the water environment. The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) leads on implementing the WFD, with recent work to improve freshwater quality set out in the second River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) for Scotland which ran until December 2021. In 2018, mid-way through the RBMP, a total of 65.7% of Scotland’s surface water and groundwater bodies were assessed as being in a good or better condition. This marked an improvement in the condition of water bodies since 2015 at the start of the second RBMP cycle when 63.5% of water bodies were at good or better condition.

The third River Basin Management Plan for Scotland 2021–2027 published in December 2021 reported that water quality is now in good or better condition in 87% of Scotland’s water environment. The upgrade in water quality reflects improvements made through Scottish Water’s investment programme and the sustained hard work by all stakeholders to improve rural land management practices and reduce diffuse pollution.

The flows and levels in Scotland’s water environment are currently at good or better condition in 90% of rivers, lochs and groundwaters. This is up from 88% when SEPA published the second RBMPs in 2015. Since then 29 barriers to fish migration have been removed or eased. SEPA identified additional barriers and confirmed that a number do not need action. When taken together, this now means that 88% of Scotland’s rivers and lochs are at good or better condition for fish migration, up from 86% in 2015.

The physical condition of Scotland’s water environment is now at good or better condition in 90% of our waters. Since 2015, SEPA has completed five projects to restore the physical condition of rivers and has another 17 in development. When the above assessments of water quality, water resources, fish barriers and physical condition are combined with 97% of waters being free from aquatic invasive non-native species (INNS), the combined classification indicates that 66% of Scotland’s water environment overall was in good or better condition in 2020. This was an improvement of three percentage points in overall condition since 2015.

The Route Map recognised the need to target action towards restoring water bodies supporting freshwater pearl mussel populations. To maintain and enhance populations it is important to ensure high water quality at a catchment scale. This was successfully achieved through the physical restoration of rivers in priority catchments as part of the Pearls in Peril EU LIFE+ project. This project delivered substantial biodiversity benefits before closing in 2017. During 2019-2020 further partnership work to extend physical restoration of priority catchments continued with support from the Biodiversity Challenge Fund.

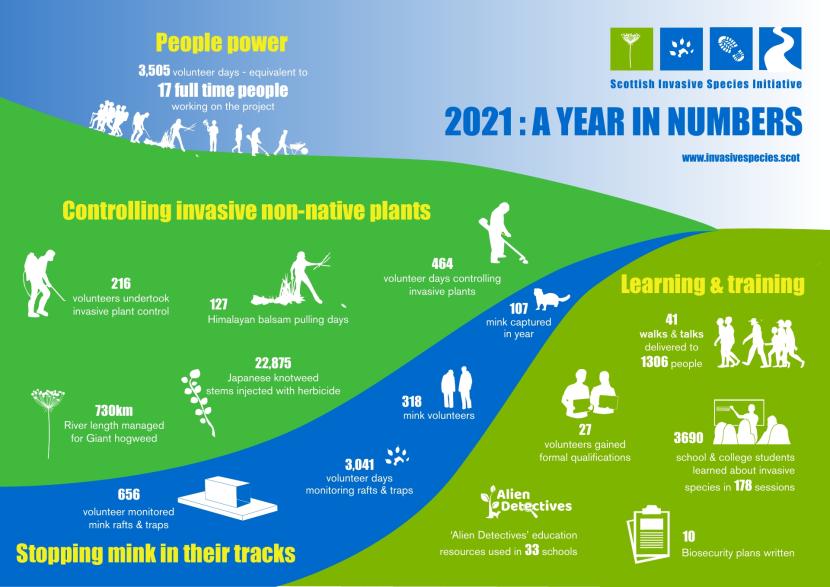

The Scottish Invasive Species Initiative (SISI) began in October 2017 with funding of over £2 million from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and NatureScot. This project has now been extended until 31 March 2023. It is led by NatureScot and tackles INNS at landscape scale with a small project team working alongside local delivery partners across most of the northern third of the Scottish mainland. By the end of 2021, volunteers had contributed over 90,000 hours to eradicate Japanese knotweed with herbicide injections across hundereds of sites, thus reducing this invasive species at many locations across multiple catchments. SISI have published information on all its project activities, case studies of invasive plant control, and annual infographic summaries, the latest of which is shown below. During 2018 – 2021 over 170,000 Japanese knotweed stems have been injected with herbicide and nearly 3000 km river length managed for giant knotweed.

Infographic text summary

People Power: 3,505 volunteer days - equivalent to 17 full time people working on the project

Controlling invasive non-native plants: 216 volunteers undertook invasive plant control, 127 Himalayan balsam pulling days, 464 volunteer days controlling invasive plants, 22,875 Japanese knotweed stems injected with herbicide, 730km river length managed for giant hogweed

Stopping mink in their tracks: 656 volunteer monitored mink rafts and traps, 3,041 volunteer days monitoring rafts and traps, 318 mink volunteers, 107 mink captured in year

Learning and training: 41 walks and talks delivered to 1306 people, 27 volunteers gained formal qualifications, 3690 school and college students learned about invasive species in 178 sessions, 'Alien Detectives' education resources used in 33 schools, 10 Biosecurity plans written

SEPA identified ‘diffuse pollution priority catchments’ in the Rural Diffuse Pollution Plan for Scotland to help target catchments that were failing to meet environmental standards. The most recent performance report in quarter three of 2019-20 showed 91.7% uptake of measures to alleviate diffuse pollution, exceeding the target of more than 80%. The third RBMP for Scotland reported, in December 2021, that SEPA’s priority catchment initiative continues to support land managers in 57 priority catchments to achieve and maintain compliance with regulatory standards and go further where possible.

Phase two of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) River Restoration and Biodiversity Project concluded with a report that sets out principles and recommendations to be adopted when restoring rivers. The project has developed into a Programme, one of two run under the auspices of the IUCN UK National Committee. The aim of phase three is to establish a network of river restoration sites across the UK and Republic of Ireland which will be monitored and appraised to illustrate the biodiversity benefits of restoring rivers.

The Route Map aimed to restore four pilot catchments with associated biodiversity benefits. Scottish Government published a framework for the physical restoration of Scotland’s rivers in 2015 and established The Water Environment Fund through which SEPA provides funding to support restoration projects focussed primarily on urban rivers and the removal of barriers to passage of fish in rivers. Information on 11 case studies of river restoration projects funded through the Water Environment Fund during the 10 year SBS plan period is provided on SEPA’s website.

Priority Project 4 - Securing economic and social benefits from, and investment in, natural capital

Aim

This Priority Project included the target of ensuring that businesses are more aware of their reliance on Scotland’s natural capital, with more investment in building natural capital.

Natural Capital is the environmental resources, e.g. plants, animals, air, water, soils, that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people. Scotland was the first country in the world to publish a Natural Capital Asset Index (NCAI). It tracks changes in the potential of Scotland’s terrestrial ecosystems to contribute to people’s well-being and the economy. The Route Map has helped to steer its refinement, raised awareness of our reliance on natural capital and contributed to plotting a path towards building our natural capital.

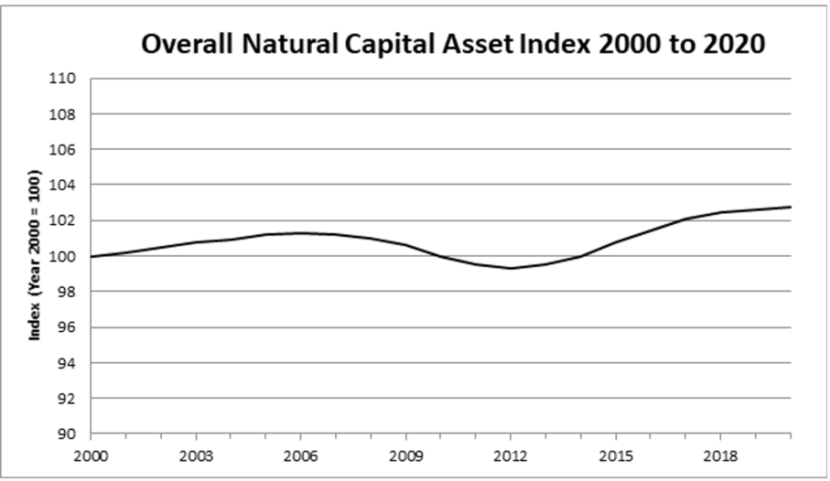

The NCAI is based on assessments of habitat quality and quantity. Habitat quantity is tracked using data on land cover in Scotland and habitat quality is tracked using 38 separate indicators based on data gathered by a range of organisations including through citizen science. The complete data model and all the underlying data can be viewed and downloaded from NatureScot. The NCAI baseline was the year 2000 but we know that Scotland's natural capital deteriorated between the 1950s and 1990s with declines in extent of many habitats including heather moorland, grassland and bogs, and in many species populations, due to factors such as afforestation, land drainage, and intensification of farming.

Work continues on improving the data underpinning the NCAI. For example, a new set of habitat maps for Scotland was published in April 2021, their production uses satellite data and is repeatable thus they can be used to track land use change (see also the section below on ‘supporting actions’). The June 2022 update notes that Scotland's potential to deliver ecosystem services has grown slightly over the past 20 years and is at its highest level since 2000.

Graph showing the overall Natural Capital Asset Index from 2000 to 2020, this is a smoothed curve with 2000 as the baseline year.

The NCAI is a National Indicator within the National Performance Framework, acting as an economic indicator of sustainable development. Scotland's National Strategy for Economic Transformation further embeds natural capital as underpinning our prosperity, health and a wellbeing economy in which restoring nature and investing in our natural capital and land-based economy will help to tackle the twin climate and nature crises, create new opportunities for nature-based businesses and jobs, and help to share the benefits from a just transition.

In 2019 NatureScot published a feasibility study for a marine Natural Capital Asset Index for Scotland. The study showed that developing such an index is feasible, but that data and indicators are not yet sufficiently developed for this to be immediately possible.

Since 2017 a number of organisations have been working to trial the Natural Capital Protocol (NCP), developed by the Capitals Coalition, alongside other natural capital approaches with land-based businesses in Scotland. These trials have been pioneering projects, including the world's first ever trial of the NCP on a land-based business, led by Crown Estate Scotland. The learning from this trial was used by NatureScot to develop a natural capital assessment template for landholdings that is now being trialled by farmers across Scotland. In 2020 Scottish Forestry published a report on ‘Applying the Natural Capital Protocol Forest Products Sector Guide’. This is the first application in the UK of the Forest Sector Guide under the NCP.

The Scottish Forum on Natural Capital (SFNC) was launched in 2013 and now has a membership of over 100 organisations including many businesses. It has formed a partnership with Business in the Community and provides resources that support organisations to take action to protect and build Scotland’s natural capital.

The SFNC in partnership with the Global Ethical Finance Initiative, Scottish Government, the United Nations Development Programme and Global Canopy ran a series of events during the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties in Glasgow in 2021 (CoP26). These explored ways in which greater investment could be leveraged from the private sector into nature. The Scottish Nature Finance Pioneers working group ran three 'hackathons' at CoP26 to explore blended finance approaches in Riverwoods, Vacant and Derelict Land, and lessons from the Landscape Enterprise Networks project led by SEPA and Nestlé.

In 2021, an annual roundtable of public sector leaders convened by the SFNC and NatureScot agreed a set of principles for natural capital accounting on public land and launched the 100 Business Actions for Nature project to encourage businesses to contribute to the transformational changes needed to meet the twin climate and nature crises.

Opportunities for new investment by business in green infrastructure, especially in the Central Scotland Green Network area have been taken forward by the Scottish Conservation Finance Pioneers group. They focussed on the vacant and derelict land pillar of the Route Map to £1 billion, an initiative published in May 2020 by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and SEPA aimed at unlocking £1 billion of new investment for nature conservation in Scotland.

The Woodland Carbon Code (WCC) is a UK government scheme administered by Scottish Forestry. It allows the owners of new woodland planting schemes to calculate the total carbon sequestration their woodland will achieve over the lifetime of the trees. Pending Issuance Units (PIUs) have a value and may be sold but may not be used in an offsetting calculation until the trees have grown and the carbon sequestration verified. In 2020 the UK Land Carbon Registry was launched as a joint platform with The Peatland Code to ensure the transparency of all UK Land Carbon Projects.

Between July 2015 and March 2020 77 projects in Scotland were validated, covering around 8,000 ha and estimated to sequester more than 2.7 million tonnes of carbon dioxide over their lifetime. During 2020, 71 new projects were registered with the WCC in Scotland representing a 45% increase in the number of projects and a 40% increase in area, an addition of almost 5,000 ha. These newly registered projects are estimated to sequester around 1.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide over their lifetime. Following rapid growth in the UK carbon market, especially in Scotland, Scottish Forestry has announced that the Woodland Carbon Code is to be strengthened with tougher new tests so that it remains the ‘gold standard’ for all woodland creation carbon schemes.

The Peatland Code was developed in 2015 and is managed by the IUCN Peatland Programme. The Code allows the reduction in carbon emissions through peatland restoration to be quantified, validated, and verified in a similar way to the Woodland Carbon Code. Projects yield PIUs at validation, verification then allows PIUs to be converted to Peatland Carbon Units, which can be used to offset UK-based emissions. In May 2022 the total number of UK Peatland Code projects, including those under development, was 96 of which 73 were in Scotland. Of the 15 fully validated UK projects 11 were in Scotland. The projected emissions reduction from all the UK validated projects is 563,000 tonnes CO2e.

Increased interest in investing in UK Land Carbon Projects represents an opportunity for generating substantial benefits for biodiversity. NatureScot are working with partners across the UK to help realise this opportunity and maximise the benefits for nature. Interim principles have been established to help shape new natural capital markets as highlighted in the ministerial statement from Ms Mairi McAllan, Minister for Environment and Land Reform in March 2022 on emerging markets for private investment in Scotland’s natural capital.

Project Project 5 - More people experiencing and enjoying nature

Aim

This Priority Project included the target of increasing regular visits and active travel in greenspace through improved infrastructure, information and campaigns and the provision of activities and events.

Participation in outdoor recreation helps to improve our health and wellbeing, strengthen local economies and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by increasing active travel and reducing congestion. Projects to enable participation in outdoor recreation and to help everyone pursue active lifestyles included expanding and promoting the National Walking and Cycling Network (NWCN) of paths, trails and canal towpaths, and providing online information on our finest long-distance trails on the Scotland’s Great Trails website.

Between 2015 and 2020 NatureScot, Sustrans Scotland and Scottish Canals collectively spent £30 million on developing 625 km of new and improved routes. An Evaluation Report on Scotland’s National Walking and Cycling Network estimated that 145.1 million walking and cycling trips took place on the NWCN during 2019, helping to take 19.5 million car journeys off the road thereby saving 7,100 tonnes of CO2e.

Numerous platforms across the public, voluntary and private sectors provide information on opportunities to enjoy the outdoors including, for example, Ramblers Scotland who published an initial online Scottish Paths Map in August 2021 showing around 42,000 miles of paths in Scotland, many of which are not shown on Ordnance Survey maps.

The ‘Improving Public Access’ element of SRDP’s Agri-Environment Climate Scheme (AECS) committed £7.9 million between 2015 and 2018 to support land managers and other organisations and groups to create and improve 166 km of paths across rural Scotland by installing signage, gates and other infrastructure. These improvements make outdoor access, recreation and enjoyment of the outdoors possible for a wide range of users, connecting places and people whilst integrating recreational use with managing land for other objectives.

Responsible outdoor access is promoted through the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (SOAC). The Code explains how everyone can go on to most land to enjoy the outdoors – as long as they behave responsibly. It is based on three key principles: respect for the interests of others; care for the environment; and, taking responsibility for your actions. The Code is accompanied by guidance aimed at different audiences and activities, including camping, cycling, dog walking, horse riding, water sports, and various land and water managers.

The Green Infrastructure Strategic Intervention is a programme led by NatureScot and funded through the 2014-2020 European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) programme. Through the Green Infrastructure Fund (GIF) it supports projects to create and improve multifunctional green infrastructure in deprived areas of urban Scotland, working with public and third sector organisations to improve habitats and biodiversity, transform derelict land, address flood risk and improve health and wellbeing.

Phase one of the GIF allocated £7.5 million of ERDF funding to seven capital projects. These included Glasgow City Council’s Greater Easterhouse Integrated Green Infrastructure Project, which created integrated green and blue networks and improved open spaces within two areas, forming connections with the Seven Lochs Wetland Park and transforming over 29 ha of land within a socially and economically deprived area. The improved green infrastructure is helping to manage flood risk, provide accessible greenspaces for people, and improve habitats for biodiversity, including the Easterhouse water vole population. A further £8 million from the ERDF was allocated to projects in 2019; these will be completed by June 2023 despite delays from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Natural and Cultural Heritage Fund, administered by NatureScot, was one of the Strategic Interventions in the 2014–2020 ERDF programme and delivered 13 projects across remote and rural areas that will enable more people to enjoy and experience nature, for example the Corrieshalloch gorge gateway and the Dundreggan Rewilding Centre.

Supporting the better provision and quality of greenspace through development planning and place-making helps biodiversity, increases opportunities for people to connect with nature and improves our health and wellbeing. Developers and planners have included blue-green infrastructure within spatial plans at various scales in Edinburgh, Stirling and Glasgow. Architecture and Design Scotland, the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations, NatureScot and Scottish Government have worked together to support and promote Green Infrastructure in social housing and in 2018 published a report on ‘Maximising the benefits of green infrastructure in social housing’. New requirements soon to be placed on Planning Authorities to: develop Open Space Strategies; conduct Play Sufficiency Assessments; and, deliver Positive Effects for Biodiversity in new developments will all increase the quality and extent of greenspaces in future.

Many NGOs and individual volunteers are involved in running citizen science activities that collect data on the natural world, for example, species records and this remains a popular activity and a valuable source of information for monitoring biodiversity. Many citizen science activities were impacted by Covid-19 and in response NatureScot promoted a number of surveys and citizen science activities that could be done in and around homes and gardens.

The environmental training and volunteering organisation TCV Scotland (The Conservation Volunteers) continued to work with communities and young people through its Scotland Counts citizen science project. This helps to connect communities with nature in local greenspaces, support the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) agenda through working with schools and build community resilience to local flooding by increasing awareness and capacity in targeted areas to monitor river levels and identify potential blockages. During lockdown the project successfully delivered various online courses, events and presentations to schools, communities and TCV staff. These included promoting Women and Girls in Science, contributing to the Glasgow Science Centre online science festival and Scottish Wildlife Explorer online session for recently arrived families from ethnic minority backgrounds. CoP26 provided the focus for various volunteer conservation and citizen science activities supported by Scotland Counts citizen science project, including running sessions with Glasgow City Council.

The overall aim to improve levels of regular participation in outdoor recreation, volunteering and learning by all of Scotland’s people has been taken forward by many partners, including Volunteering Matters Action Earth, a small environmental community grant scheme that supports volunteers to get involved in practical activities to improve local greenspaces for people and nature. Projects have focussed on volunteering by younger and older people and by people with disabilities or poor health, as well as in areas of multiple deprivation. The John Muir Award scheme in Scotland, run by the John Muir Trust, encourages people from all backgrounds to connect with, enjoy and care for, wild places through activities such as tree planting, creating wildflower areas, restoring ponds, clearing invasive species, collecting litter, and improving paths. Other award schemes such as the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award and organisations such as TCV Scotland and members of Scottish Environment LINK enable more people to enjoy and experience nature through volunteering.

National and local participation campaigns, events and activities and outreach work targeted at under-represented groups including people from minority ethnic backgrounds, people with disabilities and disadvantaged families, individuals and communities have been organised and run by a number of partner organisations in addition to those mentioned above, including for example Backbone CIC and Paths for All.

Priority Project 6 - Taking Learning Outdoors

Aim

This Priority Project incorporated a specific target to ensure that 100 schools in the 20% most disadvantaged areas across Scotland have access to quality greenspace for outdoor learning. This took forward the internationally distinctive Scottish Government commitment made in 2016 to embed ‘Learning for Sustainability’ as an entitlement for all school pupils, and encouragement for schools to take learning outdoors and into nature.

The Learning in Local Greenspace project provided practical support to schools serving Scotland’s 20% most disadvantaged communities. It helped participants to access and where necessary develop and improve greenspace provision close to schools. It aimed to remove or reduce barriers to learning in local greenspaces and embed outdoor learning practice across the curriculum. One hundred and fifteen schools in 12 local authorities signed up to the project and worked with NatureScot and various partner organisations. The percentage of teachers taking learning out into their local greenspaces on a very regular basis rose by 19.2 percentage points (baseline = 9% and post-project = 28.2%), while those feeling fairly or very confident to take learning outdoors rose from 54% to 85%. After the project, more than a third (37%) of teachers felt that their pupils had a ‘good or excellent’ connection to nature, compared to just 19% prior to the project. The proportion of teachers who believed their pupils’ engagement in learning outdoors was good or excellent also increased from 56% to 79%. NatureScot supported 18 partners through an Outdoor Learning in Nature Fund to provide additional support to project schools.

The project developed a number of digitally accessible resources including a resource pack ‘Beyond Your Boundary – easy steps to learning in local greenspace’ to support and inspire educators to use their local greenspace for learning. The Greenspace Map for Outdoor Learning is designed to help educators find their local greenspace. Case studies and films share the experiences of schools in taking learning outdoors into local greenspaces.

The Teaching in Nature programme was developed by NatureScot and the University of Stirling and delivered by a partnership of NatureScot, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) and Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA). Teachers from across a wide geographical area took part in the programme to enhance their outdoor learning practice. Nine participants took on the additional challenge of achieving Professional Recognition in Outdoor Learning from the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) via the programme and GTCS re-accredited Teaching in Nature until 2024, describing the programme as ‘sector leading’.

A partnership between NatureScot, Scottish Forestry, Forestry and Land Scotland, Historic Environment Scotland, CNPA, LLTNPA, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and the Scottish Advisory Panel for Outdoor Education developed the Outdoor Learning Directory. This web-based resource is regularly updated and provides outdoor learning information on reserves and the national forest estate by signposting news, events, training and funding opportunities, including biodiversity resources for educators.

Scottish Forestry employs an Outdoor and Woodland Learning (OWL) Scotland Education Programme Manager and supports a network of local OWL groups across Scotland.

West Pilton Park Wee Forest is one of 20 Wee Forests planted in winter 2021/22 by Edinburgh and Lothians Greenspace Trust as part of the NatureScot Wee Forest Demonstration Project.

Priority Project 7 - Developing Scotland's natural health service

Aim

This Priority Project included the target of improving greenspace quality and use on at least one hospital or health care facility in each NHS Health Board in mainland Scotland.

NatureScot led the broad and ambitious ‘Our Natural Health Service’ programme to work with national and local cross-sectoral partners to achieve a population-level change in the use of the outdoors in order to deliver health and wellbeing outcomes. Initially four Green Health Partnerships (GHPs) were established in North Ayrshire, Dundee, Highland and Lanarkshire to demonstrate and promote the physical, mental and social health benefits of outdoor activity and contact with nature with the aim that green health activities are routinely prescribed by health professionals. A further phase of support for the Dundee, North Ayrshire and Highland GHPs involving NatureScot, Scottish Government Active Scotland Division and Transport Scotland is underway on referral pathways, green health prescribing and mainstreaming the GHP approach.

With £3 million of funding from Scottish Government, NHS Scotland Health Boards and the Green Exercise Partnership (GEP), the NHS Greenspace Demonstration Project delivered greenspace infrastructure improvements at 13 sites across ten mainland Health Boards, with additional sites identified for future improvements by NHS Shetland and NHS National Services Scotland. The GEP provided assistance to each Health Board to undertake landscape assessments, appraisals and master planning of the estate to develop priorities for future greenspace improvements across one or more of their sites. Overall, nearly 90 ha of greenspace was improved in the first phase. This included 46 ha of woodland brought back into sustainable management, 11,000 trees planted, four therapeutic gardens created, 1.4 ha of wildflower meadow planted and 20 km of new or upgraded paths and active travel routes created.

Work continues through the GEP to embed positive management of NHS greenspace in policy and practice. In 2020 the GEP published the report 'Unlocking the Potential of NHS Greenspace for Health and Wellbeing' detailing achievements and learning points; this was followed by a webinar in May 2021 on the principles of landscape planning and design, accompanied by a report ‘NHS Greenspace: Good Design of the Outdoor Estate’.

The GEP brought closer working with Scottish Government to develop proposals to integrate the lessons learnt from the NHS Greenspace Demonstration Project into policy and practice, including mapping the NHS outdoor estate, developing natural capital audits in support of the ambitions set out in the biodiversity and greenspace sections of NHS Scotland’s Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy 2022 to 2026. A wide range of resources are available on the NatureScot website, including short films and case studies on the NHS Greenspace Demonstration Project. A set of green health infographics and a number of short public-facing animated films designed to be shown at healthcare / leisure facilities have been developed for use by the GHPs and other partners of the ‘Our Natural Health Service’ programme

Priority Project 8 - Protected Areas in good condition

Aim

The Route Map adopted the target of at least 80% of designated features in favourable condition by 2016. This indicator measures the proportion of natural features on protected nature sites which are in satisfactory condition; or are recovering, with the necessary management measures in place.

Protected nature sites (protected areas) are Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), which are identified as ‘special’ for plants, animals or habitats, rocks, landforms or a combination of these features. NatureScot selects SSSIs after detailed survey and evaluation against scientific criteria. Protected areas also include Natura 2000, which is an EU-wide network made up of sites designated under the EC Birds and Habitats Directives. Sites designated under the Birds Directive are termed Special Protection Areas and sites designated under the Habitats Directive are termed Special Areas of Conservation.

The condition of more than 5,000 individual notified features are assessed through NatureScot’s Site condition monitoring programme, which contributes to the Scottish Government National Performance Indicators. Favourable condition means that the features for which SSSIs or Natura sites are designated are in satisfactory condition or are recovering with the necessary management measures in place, such that NatureScot predicts that the land will in due course reach favourable condition. The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy: report to Parliament 2017 to 2019 provides detail on the status of notified features, and NatureScot publishes the Official Statistic The proportion of Scotland's protected sites in favourable condition 2022. The Route Map target was achieved in March 2016 with 80.4% of natural features on protected areas in favourable or recovering status. Since 2016, the proportion of features in favourable or recovering condition has declined, and stood at 77.9% in March 2022; some of the reasons for this are explained via the link above.

Site condition monitoring acts as a trigger for remedial management when an unfavourable assessment is made, focussing action on those sites that are in most need of effective conservation management. The aim is to identify the causes of unfavourable condition quickly and to ensure that appropriate remedial management is put in place through partnership working. Progress in returning features to favourable condition is hampered when there is no on-site management action that can be taken because the drivers of change are acting at a distance from the protected area; this provides challenges in working towards improving the condition of protected sites in the longer term. Examples of such features include seabird and wader populations in coastal sites where the drivers of their decline are acting on the feeding grounds elsewhere. In addition, a number of important drivers of change require landscape-scale coordination, for example deer grazing and controlling INNS, which means there is often a limit to the ability of on-site action to improve condition.

There are more than 1,800 protected areas in Scotland covering approximately 18%1 of land and freshwater, thereby ensuring that at least 18% of land and freshwater is under conservation designation. 37% of the marine environment is currently protected. In the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy post-2020: Statement of Intent Scottish Government set a target that the extent of land protected for nature in Scotland will be at least 30% of our land and sea area by 2030.

1the area of land covered by protected areas is 17.6%

Priority Project 9 - Conservation of priority species

Aim

The Route Map adopted the target of six high profile wildlife projects underway in 2015, with a further suite of species projects to be developed. This work involves a wide range of partners and a variety of funding mechanisms. Wildlife projects highlighted in the Route Map represent only a fraction of the total number of species conservation projects undertaken in Scotland between 2015 and 2020.

The Pollinator Strategy for Scotland 2017 - 2027 and annual progress reports are available on the NatureScot website. Highlights include the establishment of pollinator trails at National Nature Reserves and publication of guidance on Helping Scotland's Pollinators. Delivery of the Pollinator Strategy requires support from a range of partner organisations, for example, the Buglife (Scotland) B-Lines project. NatureScot hosted a Scottish Local Authority Pollinator Conference in June 2021 to highlight and share experiences of implementing pollinator-friendly practices in public greenspace. Many local authorities are now integrating pollinator-friendly practices into their management of greenspaces and active travel networks.

The Scottish Plant Health Strategy was published in 2016 and the Plant Health Centre, a virtual ‘centre of expertise’ was launched in 2018. The Strategy continues to raise awareness of good practice, for example via the International Year of Plant Health 2020, the Scottish Plant Health Conference in March 2020, and the first UK National Plant Health Week in September 2020. The Scottish Plant Health Centre has commissioned a range of plant health research projects and has worked with the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and other parts of the UK Plant Health Service to develop a draft Plant Biosecurity Strategy for Great Britain.

The South of Scotland Golden Eagle Project oversaw the release of nineteen eagles since 2018, as a result there are now more golden eagles in south Scotland than at any time recorded in the last two hundred years. The population as a whole now exceeds 30 birds. Effective community engagement has been the cornerstone of success, with more than 10,000 volunteers and special project participants of all ages. The first ever UK Golden Eagle Festival was held in Moffat in autumn 2021 and the project’s website includes regular blogs. In June 2022 the project was awarded the prestigious Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM) Tony Bradshaw Award for Outstanding Best Practice.

Home to over 60,000 pairs of puffins, around 8,000 razorbills and 9,000 guillemots the Shiant Islands were declared rat free in 2018 marking successful completion of the Shiant Isles Recovery Project coordinated by the RSPB, with support from the European Union’s LIFE programme (LIFE+), NatureScot and the landowner. This has secured a safe nesting area for one of Europe’s most important seabird colonies. Previously unable to breed on the islands due to their vulnerability to rat predation European storm petrels bred successfully in 2018.

The Langholm Moor Demonstration Project was established in 2007 to explore and demonstrate the relationships and resolve conflict between moorland management for red grouse and other moorland species including hen harrier. It concluded in 2019 with the publication of The Final Report of the Langholm Moor Demonstration Project Partners 2008-2017 highlighting some recovery of wading bird populations, support for rural jobs and many visitors seeing hen harriers and other raptors. The project’s findings contributed significantly to the independent Grouse Moor Management Group report which looked at the environmental impact of grouse moor management practices and advised on the option of licensing grouse shooting businesses upon which a ministerial statement was made in November 2020.

In March 2021 Langholm Moor was the subject of one of the largest community-led buyouts in Southern Scotland. The land now supports a community-owned nature reserve with plans underway to secure more funding to extend the community landholding.

The Hebridean Mink Project, established in 2001, quickly reduced the number of American mink to very low numbers in the Western Isles. Trapping the last few mink over such a large area is proving to be difficult. Currently the population of mink is being kept at a very low density by a small number of trappers, which has had significant positive consequences for ground-nesting birds. This includes colonial species like terns and gulls, but also wader species such as oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, snipe, dunlin and ringed plover as well as many duck species. Ongoing trapping effort is required to maintain mink populations at a low level and allow the biodiversity of the Western Isles to continue to recover.

The Partnership for Action against Wildlife Crime in Scotland’s ‘Heads Up for Harriers’ partnership has been a key public-facing project combating crime against hen harriers. Established in 2015 the project engaged 31 estates and monitored 147 chicks to fledging. Some estates have had successfully breeding harriers for the first time in many years. Work detailed in a NatureScot Research Report ‘Heads up for Harriers - Image analysis 2015-2019’ published in 2020 revealed some cases of natural failure that may have otherwise been unexplained or considered suspicious, together with key factors influencing nesting and fledging success. The project ended in 2021. Partnerships, information and intelligence-sharing increased through this project, with multi-agency solutions adopted to prevent wildlife crime.

Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels is a partnership project, led by the Scottish Wildlife Trust, to raise awareness of threats to red squirrels, monitor squirrel populations and manage populations of grey squirrels that threaten native red squirrels. In 2017 the project secured funding, including from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, for developing community action. This has engaged local communities and continued conservation work, including responding to squirrel pox outbreaks in southern Scotland and coordinating national Scottish squirrel surveys. The 2019 annual survey found that most of Scotland’s red squirrel populations remained stable and that grey squirrels continue to decline in North East Scotland. In 2019 the project won the Scottish Land and Estates ‘Helping It Happen Conservation Award’. Project funding has been extended for a further two years; from April 2022 to March 2024 it will continue to build upon the network of skilled volunteers and protect red squirrels through grey squirrel management in priority areas. This transition phase will consider how the project’s priority work, and that of other invasive non-native species projects, can be aligned and sustained in the future.

The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan was largely completed in March 2020. The partnership Scottish Wildcat Action successfully raised awareness of the plight of wildcats and conducted a massive camera-trapping operation involving many volunteers. The images collected identified a minimum of 29 individual wildcats, 119 individual hybrids and 82 individual feral domestic cats. A trap, neuter, vaccinate and return programme captured 213 cats for neutering, alongside 20 wildcats for genetic screening and/or equipping with GPS collars, which improved our understanding of Scottish wildcat behaviour. A genetic screening programme showed that the wild-living cat population is a hybrid swarm with almost no cats passing the genetic threshold for Scottish wildcat. These results have been used by the current Saving Wildcats project, which incorporates recommendations outlined by members of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission Cat Specialist Group, by establishing an ex situ breeding centre for wildcats followed by the release of captive bred wildcats into the Cairngorms National Park.

When the Scottish Biodiversity List was published it was not possible for land managers to easily find out which species had been recorded on their land. A function was added to the National Biodiversity Network Atlas Scotland which permitted boundary areas to be drawn and a list of all Scottish Biodiversity List species within that area to be identified; this enables land managers to prioritise their land management decisions.

Scotland holds nearly 15% of the global breeding population of Eurasian curlew. The combination of global conservation status and rapid decline makes curlew a conservation priority in Scotland. In 2015 the RSPB launched a curlew recovery programme in Scotland with two main components: a trial management project, and an audit which identified 14 key RSPB reserves for curlew in Scotland. These feature in phase two of the curlew recovery programme (2020 – 25), which aims to ensure that appropriate land-management policies are in place and that strong partnerships are developed within the key reserves and seven priority landscapes. Established in 2017, the Working for Waders partnership provides a platform for partners in Scotland to deliver for waders, including curlew. In 2019 Scottish Forestry published ‘Woodland Creation and Curlew’, providing guidance on how to reduce impacts from woodland creation upon curlew.

Corncrakes remain heavily dependent on land management supported by dedicated agri-environment schemes. Despite SRDP Agri-Environment Climate Scheme (AECS) funding having been available, there is a smaller area under current corncrake management than under the previous scheme, which may be one of the factors contributing to recent declines in corncrake numbers; a reduction of 30% since 2014. The RSPB’s four year Corncrake Calling project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, started in August 2020. It focuses on land management, education and advocacy.

The RSPB’s corn bunting recovery work began almost two decades ago, underpinned by research which identified causes of decline and solutions. Partnership recovery work is mainly focused in north and east Scotland. Work has also been underway on the Western Isles to provide winter food, although changing agricultural systems have now made this unsustainable. The number of corn buntings in the Western Isles is very low. A resurvey of corn buntings in North East Scotland during 2015 revealed the population has stabilised. In Angus declines have been halted, with a slight increase since 2014 due to active intervention. Similarly, there have been increases in Fife.

A small-scale experimental reintroduction of water voles by Aberdeen University in the Tarland area of Aberdeenshire has been successful and the population is showing signs of further expansion. Water voles have subsequently moved into the nearby Monandavan Burn and then into the Burn o’ Vat on the Muir of Dinnet National Nature Reserve. Large scale recovery of water voles depends on mink control across Scotland.

The scope of the Route Map action on pearl-bordered fritillary was expanded to include other woodland butterfly and moth species. Butterfly Conservation Scotland (BCS), in partnership with Forestry and Land Scotland, monitored chequered skipper and pearl-bordered fritillary populations. BCS produced a Scottish Conservation Strategy identifying species in most urgent need of conservation action, including several woodland species, the following of which are in the highest priority and threat categories: Kentish glory; dark bordered beauty; and, Diana’s choreutis moth. Significant progress has been achieved regarding habitat improvement for both dark bordered beauty and Kentish glory, this will also benefit other woodland species.

The Bumblebee Conservation Trust established the Saving the Great Yellow Bumblebee project to run identification workshops and encourage people to record this declining species. Identification leaflets, the promotion of a Caithness Bumblebee trail and a 2019 great yellow bumblebee hunt across the species range in Scotland have all increased awareness. This has encouraged land managers to apply for great yellow bumblebee friendly management support through SRDP AECS. In Durness the RSPB has been working with land managers to encourage low-intensity High Nature Value crofting to benefit both corncrakes and great yellow bumblebee. With the encouragement of RSPB, volunteers on Tiree established Tiree’s great yellow bumblebee project, 2017–2021. The end of project report’s highlights include an estimated increase in the number of bees in 2021, participation by 90 adults and children, and the publication of a children’s book ‘Beataidh Banrigh Super-Bee’.

A genetic study of all four remaining native populations of alpine blue-sowthistle, conducted by Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE), found that very few individuals remain at each site and that the populations are inbred. In order to increase genetic variability, and therefore the health of the Scottish population, plants originating from different Scottish populations were planted together at new sites. This allows the plants to breed together, something which would be highly unlikely amongst the wild populations. Between 2017 and 2021 over 1,200 alpine blue-sowthistle plants were planted at 12 new sites, on five different estates.

RBGE have conducted a genetic study of Scottish populations of marsh saxifrage. This demonstrated that at locations where there might appear to be many hundreds of plants, most were clones of only a small number of genetically separate individuals. In the Pentland Hills, where marsh saxifrage had not flowered well for decades, stock fencing was erected around the saxifrage allowing grazing during the winter when the plant is not flowering, but not during the flowering season. Subsequent surveys have found flowers to be present.

It was initially proposed to conduct conservation work on the rare tufted saxifrage, however, research by RBGE found that this arctic species does not appear to be threatened by land management. The main threat appears to be from a warming climate, consequently there is little practical conservation effort that can be carried out to protect this species other than to ensure that its current habitat remains healthy. Even where habitats appear healthy it may be too late for some populations, in the Cairngorms there are some sites where tufted saxifrage has not been re-recorded for over sixty years.

The Scottish temperate rainforest’s bryophyte, liverwort and lichen communities are of international importance. RBGE has been testing the feasibility of translocating rare lichens and lichen assemblages. Starting in 2017 experimental translocations were conducted both at healthy long-established woodland and at woodland where invasive rhododendron had been recently removed. Both experiments were successful and these methods will be used to reinforce populations of threatened rainforest lichens elsewhere.

In 2021 Plantlife recruited a Lichens and Bryophyte Advisor specifically to develop a monitoring programme for Plantlife’s project ‘Saving Scotland’s Rainforest’. This post will develop and deliver species management advice to land managers and ensure that a lichen and bryophyte focus remains part of the Saving Scotland’s Rainforest programme, contributing towards the partnership work of the Alliance for Scotland’s Rainforest.

Priority Project 10 - Improving ecological connection

Aim

The target to improve connectivity between habitats and ecosystems and support landscape-scale approaches provided the foundation for many conservation actions, including those undertaken by the EcoCo Life project, which was completed in 2019 having improved habitat connectivity and coherence at 45 sites across central Scotland. Actions included restoring over 1,000 ha of peatland, improving the management of over 50 ha of grassland, and improvements to over 50 ha of wetland habitat and more than 20 ha of brackish lagoons.

The development of habitat opportunity mapping for central Scotland and the identification of delivery mechanisms progressed through work by NatureScot and partners on the Habitat Network workstream of The Green Action Trust (formerly the Central Scotland Green Network Trust). A Habitat Connectivity Map was developed to help target actions to reconnect fragmented habitat networks and steer actions towards creating new habitat.

The data on habitat connectivity in central Scotland have been used by partners to help develop nature networks through spatial planning, development management, and habitat creation projects, for example in the ‘Blueprint’ work of the Glasgow and Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership, in the Ecological Coherence Plan in Edinburgh, and in the John Muir Way Greening Study. In addition, a number of projects such as the Inner Forth Landscape Initiative, Garnock Connections and East Ayrshire Coalfield Communities have taken actions to improve connectivity between habitats and ecosystems across Central Scotland.

A national ecological network has not been developed, however, a number of landscape-scale projects have started. Projects include Flows to the Future discussed above under Priority Project 1, and Cairngorms Connect a partnership of neighbouring land managers, with support from the Cambridge Conservation Initiative’s Endangered Landscapes Programme, who are committed to a bold and ambitious 200-year vision to enhance habitats, species and ecological processes across a vast area within the Cairngorms National Park.

Notable landscape-scale projects include the Wester Ross Biosphere, which was recognised in 2016 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for its important landscapes, wildlife and cultural heritage. Other landscape-scale projects include the Nevis Landscape Partnership involving local and national organisations working together to protect and enhance the Glen Nevis and Ben Nevis area through a variety of projects, the Coigach & Assynt Living Landscape, Spey Catchment Initiative, Dee Catchment Partnership, Southern Uplands Partnership, Tweed Forum, Galloway and Southern Ayrshire Biosphere, North Isles Landscape Partnership, and Callander’s Landscape.

NatureScot published an indicator of ecological connectivity at catchment scale as part of the suite of Ecosystem Health Indicators to help prioritise actions toward improving ecological connectivity of four key habitats: woodland, heathland, grassland and marshes. This indicator evaluates habitat connectivity at a regional and a Scotland-wide scale taking into account a habitat's size, shape, configuration, distance from other similar habitats, and the effects of different habitats in the surrounding landscape. NatureScot published the method behind the indicator as a Research Report on Developing a habitat connectivity indicator for Scotland to support integrating ecological connectivity into spatial planning.

Priority Project 11 - Sustainable land management

Aim

The target for this Priority Project is promotion of measures to support biodiversity under CAP. A suite of sites demonstrating good practice aimed at supporting wildlife.

The Wildlife Estates Scotland initiative has generated increasing interest amongst land managers. This may be associated with growing public awareness amongst land managers of the biodiversity and climate crises and the benefits generated by natural capital. By May 2022, 59 estates were fully accredited with another 25 in the process of application. The total area of accredited estates is 505,065 ha with another 114,689 ha potentially to be added should all applications be successful.

Funding from the SRDP Agri-Environment Climate Scheme has been key to securing biodiversity and climate change mitigation and adaptation benefits from the land. A total of £214 million has been committed since 2015 to 3,500 projects covering 1.18 million ha of agricultural land. In total, around 3,000 land managers have had five-year contracts under AECS, delivering sustained positive management on around 30% of Scotland’s agricultural land. A review of biodiversity outcomes delivered through agri-environment programmes is provided in the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy: report to Parliament 2017 to 2019.

The scheme has contributed to delivering national and international targets for biodiversity, climate change, water quality and flood prevention, and has supported organic farming, protection of our historic environment and improved public access. Environmental benefits supported by AECS include: providing food for farmland birds in key arable areas; improving the management of carbon-rich soils and grasslands; peatland restoration; actions to halt the decline in corncrakes, corn buntings and wading birds; providing habitat for pollinators, and reducing diffuse pollution.

The Ecological Focus Area (EFA) greening requirement has provided support for biodiversity on arable farms. This has included protection for hedgerows and watercourses, nutrient efficiency measures on grassland farms, and restrictions on the use of plant protection products in some EFAs to benefit pollinators.

Following exit from the EU, Scotland entered a period of transition, with new policies and schemes being developed for the period post 2024. The Natural Capital Pilot Programme (NCAPP) is testing a number of approaches that could be adopted as part of the future rural support framework at a range of scales. Piloting an Outcome Based Approach in Scotland is one of the NCAPP projects working with 70 farmers and crofters in seven clusters to test innovative approaches to delivering and monitoring environmental outcomes on farms and crofts. For information on other projects securing economic and social benefits from, and investment in, natural capital see Priority Project four.

The SRDP Farm Advisory Service (FAS) and Scottish Rural Network provide advice and support to farmers on a number of topics through a programme of workshops, discussion groups, network farm meetings and advice notes. During the 2020 pandemic FAS increased its use of webinars and produced digital and online material.

The Soil Association Scotland’s ‘Farming for the Future’ programme is helping to build knowledge and confidence through demonstrations and workshops on topics including grassland and water management, agroforestry, building soil health, non-chemical pest control and holistic grazing. A number of collaborative groups have been established through the Rural Innovation Support Service, and the SRDP Knowledge and Innovation Transfer Fund.

The James Hutton Institute (JHI) and Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) run demonstration activities on Research Farms. At Glensaugh JHI initiated a bold transformation plan to develop a flagship climate-positive farming initiative to explore technological and agro-ecological design elements for a low-carbon economy. This has also investigated new ways of farming based on an integrated land use approach with multiple benefits for nature and sustainable livelihoods for people.

The JHI Centre for Sustainable Cropping demonstrated the potential benefits and trade-offs from a more sustainable or integrated farm management approach. Their ‘Magic margin’ field margins on Mylnefield and Balruddery research farms have demonstrated practical solutions to soil erosion while retaining biodiversity-rich habitats.