Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) Specialist Report - Land Management

This report should be cited as: Campbell, R.D., Kortland, K., Strong, R., Tallach, N., Cumberbirch J. and Mason, G. (2023). Scottish Wildcat Action final report: Land Management. NatureScot, Inverness.

Authors and instituions: Roo Campbell, Scottish Wildcat Action, Kenny Kortland, Forestry and Land Scotland, Rebekah Strong, Scottish Land & Estates, Nicola Tallach, Scottish Wildcat Action, Jackie Cumberbirch, Forestry and Land Scotland, Gareth Mason, Forestry and Land Scotland.

Year of publication: 2023

Keywords

Game management; forestry; agriculture; construction; prey; GPS-tagging; artificial dens; rodenticides; barns.

Background to SWA

The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP) was published in 2013 following the input of over 20 partner organisations. This led to the establishment of the Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) project that ran from 2015-2020, funded by the Scottish Government, National Lottery Heritage Fund and others. SWA operated with a team of project staff managed by NatureScot, and associated work was carried out by various partner organisations. The overall work programme was steered by a group made up of ten of the partners. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Cat Specialist Group reviewed the work of the SWA, and other ongoing wildcat conservation work, and provided recommendations for future action (Breitenmoser et al., 2019). A wide range of topics relevant to wildcat conservation were covered during the SWA, and have now been published as a series of reports, of which this is one. These outputs will inform the next phase of wildcat conservation work in Scotland, including the SavingWildcats ‘SWAforLife’ project that runs from 2019-2026.

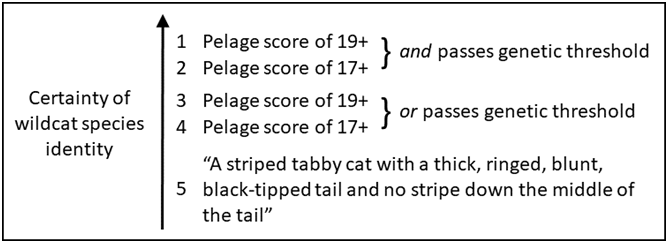

Wildcats hybridise with domestic cats and we use a combination of morphology and genetics to distinguish wildcats from domestic cats and their hybrids. The method applied is generally determined by the practicalities of management. For example, it is much easier to have high confidence in the pelage scores from a sedated cat, than from a camera-trap image taken at night. Genetic and pelage results can only be generated jointly in certain scenarios. Therefore, identifications under different situations have different levels of confidence associated with them. We therefore set different thresholds for identification of wildcats based on the ability to distinguish pelage and genetic characteristics in different situations. The confidence hierarchy, and the definitions used in this report, are given below.

A graphic showing increasing certainty of wildcat identity over five levels as more information on pelage and genetic status are available.

It reads:

Unless described otherwise, a wildcat in this report is defined as a cat with a 7PS pelage score of 19+ and/or that passes the genetic threshold for the genetic analyses. The consequences of applying different thresholds in different situations and management regimes are also examined.

A ‘wildcat’ in this report is defined at level 4 by a cat with a pelage threshold of 17+. Genetic information is not available for all cats and so is not used in population size assessments.

Background

How the living and working landscape of Scotland is managed has played an important role in the current conservation status of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) and it will continue to do so in the future.

Hybridisation and the presence of feral cats and hybrids in wildcat habitats is recognised as the main threat to the survival of the wildcat in Scotland. However, a combination of other threats linked to the management of the land have no doubt contributed to the wildcat’s problems. These include habitat loss or fragmentation and the killing of wildcats, particularly prior to their legal protection.

Wildcats require a mosaic of suitable habitats with sufficient cover in which to hunt, shelter and breed. Changes to the land use, habitat fragmentation and degradation all pose potential threats to wildcat numbers, in addition to the ongoing management activities being undertaken as part of estate, forestry or agricultural operations. However, past or ongoing land management in some areas may help create habitat suitable for wildcats. For example, the rotational clear-felling of commercial conifer plantations can create a mixture of prey and cover habitat combinations that wildcats use, while traditional farming practices may have allowed wildcats to exist historically in some areas that were otherwise poor habitat.

Summary of work

-

Ahead of the project, land management was recognised as of key importance to wildcat conservation. Threats identified included those from game management, forestry and agriculture. Construction work in wildcat areas could also impact on wildcats.

Game management

- Wildcats are legally protected under a 1988 amendment to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. Feral domestic cats are not protected under the act and can be shot legally by gamekeepers during predator control. However, hybridisation with domestic cats means that reliably distinguishing wildcats from feral domestic cats and hybrids is difficult and the accidental shooting of wildcats misidentified by gamekeepers is a recognised threat. Conversely, legitimate control of feral cats by gamekeepers may play a role in mitigating the threat of further hybridisation from domestic cats if conducted appropriately.

- A protocol for ‘wildcat-friendly’ predator control (WFPC) was first developed under the Cairngorms Wildcat Project and promoted under this project. In essence, the protocol discourages the use of spot-lighting (or lamping) at night for cat control, encouraging instead the use of cage-trapping, so that the cat can be more reliably identified and, if thought to be a wildcat, released. We asked the Moorland Forum to review the WFPC, and an updated version was added to the Moorland Management best practice website.

- We identified an emerging threat to wildcats from thermal-imaging-assisted night-shooting. Wildcats cannot be identified reliably using this technology. We produced a leaflet highlight the risk of lamping and thermal-image-assisted night-time shooting, distributing this at events and to land management partners in 2018-2019.

- Project staff built relationships with estate managers within the Priority Areas (PAs) over the course of the project. We loaned trail cameras to five estates to enable identification of wildcats ahead of any predator control they were planning.

- Scottish Rural Development Programme (SRDP) funding was also available to any estates in the PAs to purchase and maintain their own trail cameras and cage traps. However, there was no successful take-up of this funding option. Following a questionnaire survey of 15 landowners, we identified that lack of awareness of the fund, low value and onerousness of requirements were all factors, but that landowners would consider applying to a revised scheme. Any future scheme would require more staff resources to promote it and a review of its value. Changes in land-use constraints may also help; the option is currently restricted to moorland whereas outside summer, wildcats more often use wooded habitats.

- To engage with land managers, staff and volunteers set up project stands, hosted by project partners, at targeted events such as the Highland Field Sports Fair (Moy), the Scottish Game Fair (Scone), The Black Isle Show and local shows. We published blogs and articles with land management partners (e.g. Scottish Land & Estate’s LandBusiness, British Association for Shooting and Conservation’s Shooting and Conservation, and the website of Shooting and Country Sports UK). Throughout 2019 we also ran a regular column in Shooting Scotland magazine. We revamped the wildcat ID cards popular with gamekeepers during the Cairngorms Wildcat Project, distributing these at events and with partners.

- By 2018 engagement with WFPC remained low. Reasons for this included lack of interest from some estates, an underestimate by the project of the staff time and resource needed by the project to engage with, build relationships and work with estates, or simply that some estates do not conduct predator control using methods that put wildcats at risk. To help improve engagement, we set up a land management subgroup towards the end of 2018. One task agreed by the subgroup was to have gamekeepers trial the WFPC method to inform its future development and encourage uptake of the protocol. Seven gamekeepers in the Angus Glens were involved and the trial took place over the summer. Feedback indicated that some gamekeepers may not be confident enough to identify wildcats in traps and future work could include developing a wildcat identification training video.

Forestry

- We worked closely with Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) to investigate a range of habitat management measures in commercial forestry areas and to promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice.

- FLS and SWA staff produced an awareness leaflet for forestry contractors working in forests containing wildcats, which was distributed to all forestry contractors and all relevant FLS operational staff.

- Surveys of rodent prey were carried out in Clashindarroch Forest in the Strathbogie Priority Area. The aims of this work were to determine the relative abundance of three common species of rodents in three typical habitats found in commercial plantations; unfelled stands of timber, restocked (i.e. replanted) areas, and clear-fells. Bank vole were most common in unfelled stands of timber and field voles in felled areas. Wood mice were found in low numbers mainly in felled and unfelled stands. Felled areas with high numbers of field voles likely offer the best foraging areas for wildcats. This is being confirmed by the results of the WildCRU GPS-tagging study of wildcats in forest habitats. Although bank voles are present in high numbers in the forest, they occur in habitats that are less suited to wildcat hunting (e.g. unfelled and un-thinned Sitka spruce stands). Longer-term monitoring has now been established through FLS to track annual population fluctuations in the field vole, which is thought to be the most important rodent prey species.

- From current knowledge, it would appear that timber production and wildcat conservation may be compatible where plantations consist of a mosaic of habitats that are suitable for wildcats.

- FLS constructed a total of 63 artificial dens of varying design, 30 in the Angus Glens PA, and 33 in the Strathbogie PA. FLS staff and SWA volunteers used camera traps to monitor 17 of the artificial dens for 10,490 camera days. No wildcat activity was noted in any of the artificial dens. Results so far indicate that provision of artificial dens is not a useful mitigation or conservation action. These artificial dens may however be used by wildcats in the future as they settle into the landscape.

- FLS Environment Rangers worked with SWA field staff and wildcat biologists to develop and improve pre-operational surveys for wildcats, and to enhance mitigation measures to lessen the potential impact of forest operations on wildcats. Enhanced pre-operational surveys were developed, with increased deployment of camera traps, and new restrictions on felling operations were introduced as a precautionary measure.

- FLS approaches to pre-operational surveys and mitigation will be revised according to the results of the ongoing WildCRU GPS-tagging project. An overall assessment and comparison of the benefits to wildcats and the issues created for the local timber industry will need to be carried out by FLS, in order to judge if such measures are worth rolling out more widely. From our experiences and data collected during the project camera surveys and GPS-tagging, the Scottish Forestry (formerly FCS) Guidance Note 35d: Forest operations and wildcats in Scotland will be revised.

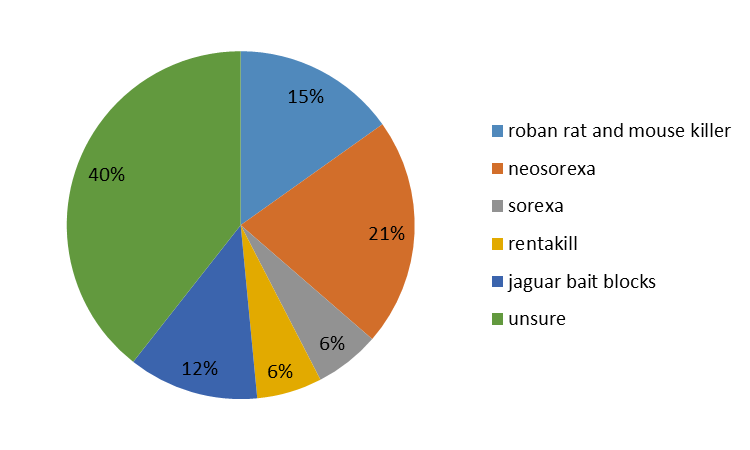

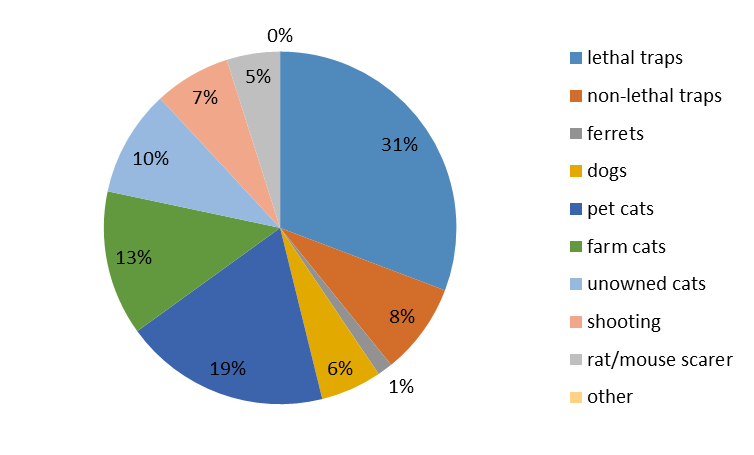

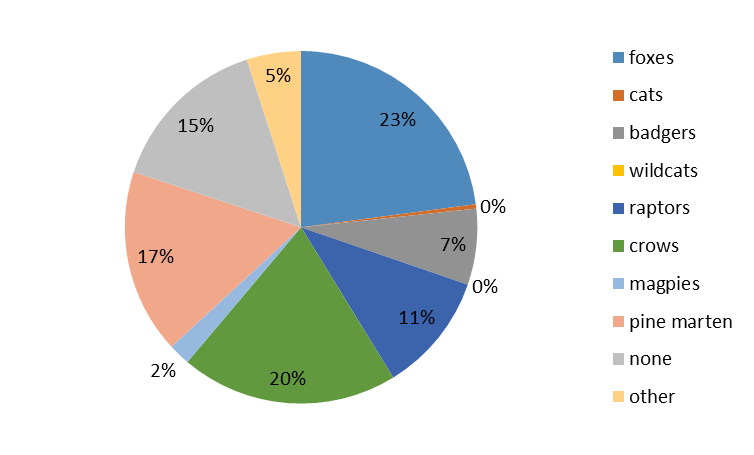

Agriculture

- Through a student placement we conducted a questionnaire survey of 147 farmers and crofters relating to their management of cats and farm pests. The responses were biased towards smaller farms and crofts and showed low (20%) use of rodenticides. The most commonly used chemicals were second generation rodenticides that present the greatest secondary poisoning risk. Most farms and crofts did not use professional pest controllers, though 90% took some measures to reduce poisoning risk. The most common non-chemical pest control methods were the use of cats. Cats weren’t seen as a predation threat against livestock (e.g. poultry), unlike foxes and crows. Though most respondents did not conduct predator control, some (30%) used shooting or lamping (11%), the latter a potential threat to wildcats.

- Through an MSc project, we assessed the levels of rodenticide in the livers of 49 wild-living cats collected on roads. 61% showed rodenticide residues, nearly half of which presented residues above the toxic level recognised for other mammals and birds. The most prevalent rodenticides detected were second generation rodenticides.

- Following this study, we ran regular columns in Farming Scotland magazine, over 2019-2020. These highlighted the risks to wildcats from rodenticides and encouraged readers to follow the code set out by the Campaign for Responsible Rodenticide Use. We also discussed wildcats’ use of barns for denning and habitat management techniques farmers could adopt to benefit wildcats.

Development

- We provided advice and wildcat records to ecological consultants involved in construction projects over the course of the project. Information gained from the camera surveys and GPS collaring study will be used to update the guidance available on the nature.scot website.

General

We held a Sharing Good Practice event aimed at consultant ecologists, developers, foresters and gamekeepers. Few gamekeepers attended and therefore the discussion focused on ecological surveys, developments and forestry.

Acknowledgements

The SWA project was supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

It was also funded by the Scottish Government, NatureScot and the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. Support and resources for associated work was also provided by all the Steering Group members: Cairngorms National Park Authority, Forestry and Land Scotland, National Museums Scotland (NMS), Scottish Land & Estates, NatureScot, Scottish Wildlife Trust, The National Trust for Scotland, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, The Scottish Gamekeepers Association, The Scottish Government, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU). In addition, Jenny Bryce and Fiona Strachan helped develop the project while Eileen Stuart, Alan Bantick and Andrew Kitchener chaired the Steering Group.

Additional sponsors, funders and contributors to SWA work included Aigas Field Centre, Ailsa Black, British Association for Shooting and Conservation, Cairngorm Brewery Company, Chester Zoo, Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, John Muir Trust, Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, Lukas Ruiter Production, MyPetOnline, NFU Scotland, petDetect, RSPB, Scotland The Big Picture, Swift Ecology and The Highland Council.

We are also very grateful to the many academics, landowners, captive collection managers, veterinary specialists and others who contributed valuable time and effort, members of the public who contributed funds and support, and in particular the many volunteers who got involved in the project.

This was a wide-ranging body of work involving the input of many people involved in land management. Many land managers across the project PAs assisted us in our work in some form. Particular thanks to the gamekeepers who took the time to meet with us and discuss predator control and other land management issues; the forestry staff who contributed to the discussion on improving forest management; the farmers who took the time to respond to our questionnaire survey; those who organised and attended the Sharing Good Practice event; and all those who worked with us to conserve, monitor and research the wildcats on their land. Martha Gavan conducted the questionnaire survey through the East of Scotland Bioscience Doctoral Training Partnership (part of the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council’s Doctoral Training Partnerships). Thanks to Athole Murray Fleming for providing space for regular wildcat columns in the Farming Scotland and Shooting Scotland magazines. In addition to those named above, The Scottish Association for Country Sports provide valuable input into our work on land management.

1. Introduction

How the living and working landscape of Scotland is managed has played an important role in the current conservation status of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) and it will continue to do so in the future.

Introgressive hybridisation and the presence of feral cats and hybrids in areas where wildcats live is recognised as the main current threat to the survival of the wildcat in Scotland (see the Monitoring and Surveys, Genetics and Morphology, and Trap Neuter Vaccinate Return Programme reports). However, hybridisation may have been driven by other factors including low numbers of wildcat. A combination of other threats linked to the management of the land have no doubt contributed to the wildcat’s current parlous state, likely including habitat loss, fragmentation and the killing of wildcats, particularly prior to their legal protection.

Wildcats require a mosaic of suitable habitats with sufficient cover in which to hunt, shelter and breed. Changes to the land use, woodland cover, habitat fragmentation and degradation all pose potential threats to wildcat numbers, in addition to the ongoing management activities being undertaken as part of estate, forestry or agricultural operations.

The project sought to engage and work with land managers and project partners to take forward a range of actions that would promote and support the conservation of the wildcat alongside existing land management practices. This included the development and continuation of work carried out with estates during the Cairngorms Wildcat Project, working with Forest and Land Scotland on the development of best practice and working with a land management subgroup to improve information flow, guidance and training available to land managers.

The three main projects identified within the SWCAP to take forward work around land management to underpin a wider conservation programme were:

2.1 Promote wildcat-friendly predator control

2.2 Promote wildcat-friendly management of estates, farms and crofts

2.3 Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice

These three projects are considered in detail within this report, including the associated actions that were identified within the National Lottery Heritage Fund application. In addition, during the course of the project’s work, we identified other areas that potentially present risks to wildcats and we discuss how we approached those issues.

2. Promote wildcat-friendly predator control

2.1 Background

The management of gamebirds such as red grouse, pheasants and red-legged partridges plays a role in the rural economy in particular areas of Scotland, including parts of the SWA Priority Areas (PAs). One aspect of this management which has the potential to have the greatest impact on the wildcat is the legal control of mammal predators that are seen as a threat to gamebird populations.

Mammals that can be controlled legally and humanely using baited cage traps, snares, spotlighting and more recently thermal scopes include feral cats, foxes, weasels, stoat and mink. A licence is required for the control of any other legally protected species and this includes the wildcat. Feral cats can be controlled throughout the year and are typically controlled on sporting estates by night-time shooting with a spotlight and/or, more recently, a thermal scope.

Baited cage-traps, which capture the animal alive, are widely used and, by law, must be checked at least every 24 hours. For maximum cost-benefit, cage traps tend to be deployed in numbers around an area of particular sensitivity, e.g. a pheasant release pen. Snares, which are typically set for rabbits or foxes, can, on occasion, also catch feral cats. If set correctly and legally, they should hold the animal alive until the gamekeeper checks it at least once every 24 hours. Both cage traps and snares should allow non-target species to be released unharmed. (Hetherington and Campbell, 2012, p.30)

The use of a spotlight typically produces eye-shine from nocturnal animals and gamekeepers can judge the species from the colour and size of the eye-shine. In recent years, this is often used alongside the thermal image scope which allows the gamekeeper to instantly pick up a heat source from any mammal within its range. It does not require the mammal to be looking up (to observe the eye shine) as the full body will be emitting heat that can be detected. The body shape and size is then used to determine the species but the coat pattern is not visible.

There is considerable scope for wildcats to be shot inadvertently if feral cats are shot on the basis of body shape or eye-shine alone. The combination of darkness, distance, and obscuring vegetation makes accurate identification of cats, particular tabby-marked ones, potentially challenging and there is significant scope for errors of judgement. Cage-trapping reduces the scope for error considerably as a much clearer view of the animal can be ascertained. However, in a spotlighting, thermal imaging or cage-trapping scenario, the safety of an endangered and legally protected species is heavily dependent on the attitudes and judgement of the gamekeeper. It is therefore crucial for the gamekeeping community to be both sympathetic towards wildcat conservation and confident in wildcat identification. (Hetherington and Campbell, 2012, p.30)

2.1.1 Field sports in Priority Areas

Of the six PAs originally selected, Morven and Strathpeffer are the only two without driven grouse moor, however some ground is managed for lowland game birds in both areas and is estimated to be below 25% by the project officers, with no shoots currently operating in Morvern to our knowledge.

The area managed by landowners that host gamebird shoots in Strathbogie is estimated to be between 25 and 50%, mostly made up of lowland pheasant and partridge shoots but with some driven grouse moorland on the higher ground. Strathavon, Strathspey and the Angus Glens all have more than 50% of the ground managed as gamebird shooting estates, both upland and lowland. Of these three, the Angus Glens contains the highest proportion of ground managed for game birds with both upland grouse moor and lowland gamebirds forming the majority of the land use in the area. Establishing and maintaining good relationships with gamekeepers, land managers and owners within the PAs would be essential to gaining information on wildcat numbers, ecology and conservation threats.

2.2 Agreed actions

2.2.1 Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan

Actions and lead partners identified to deliver project 2.1, ‘Promote wildcat-friendly predator control protocols in Priority Areas’ can be seen in Table 1 below.

|

Actions |

Action Plan Numbering |

Action Leads (as of 04/2017) |

|---|---|---|

|

ACTION IN PRIORITY AREAS |

2 |

- |

|

Promote wildcat-friendly predator control protocols in PAs |

2.1 |

- |

|

Agree a wildcat-friendly protocol including an identification key and the use of cage traps. |

2.1.1 |

Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) |

|

Ensure the wildcat-friendly protocol is incorporated in relevant training/ liaison with keepers/ rangers in PAs. |

2.1.2 |

Scottish Gamekeepers Association (SGA) |

|

Work with estates and provide resources to promote the protocol in PAs – e.g. identification cards and cage traps. |

2.1.3 |

NatureScot/SWA |

|

Work with estates to collate information on feral cats trapped; pelage and disease. |

2.1.4 |

NatureScot/SWA |

2.2.2 National Lottery Heritage Fund

As part of the National Lottery Heritage Fund application, a Wildcat Action Activity Plan was developed, setting out details of how project activities would be delivered. The project activities are arranged into six work programmes which cover a range of in situ work as well as ex-situ measures, monitoring and communications. Work Programme 1 covers the subject area of Land Management and includes the following details:

Work Programme 1: Land management actions and Scottish wildcat conservation

During the project’s development phase, the SWCAP land manager’s task group (not the same as the subgroup referred to later in this report) produced the Land Managers Scottish Wildcat Conservation Protocol, which sets out how to reduce the potential for accidental harm to wildcats during legal predator control activities. This was based on the wildcat-friendly predator control (WFPC) protocol developed and promoted successfully during the Cairngorms Wildcat Project. The Project worked with estates, land managers and gamekeepers to promote and encourage uptake of the protocol and provide support and help to use it. They also provided advice and support on how land management practices e.g. forest management can affect wildcats. The Project also sought to involve land managers in the project’s wildcat monitoring programme.

Key activities in this theme include:

2.2.2.1 Delivering training for gamekeepers and land managers

We organised targeted events in each of the PAs at which gamekeepers, land managers and estate owners and staff can learn how wildcat conservation activities can be integrated into the day-to-day running of their estates. Support from the Project Officers worked with estates on an individual basis to provide assistance and establish strong relationships, which will provide valuable links and secure a network of ‘wildcat friendly’ estates.

One of the main aims of SWA is to bring about changes in the way things are done in the wildcat PAs, which will ensure that actions to conserve wildcats persist beyond the life of the project. We aim to do this by working with further education colleges and industry training providers to ensure that training on land management practices that will benefit wildcats becomes a long-term part of their courses.

2.2.2.2 Providing access to resources to facilitate wildcat monitoring

A pool of equipment (ID cards, camera traps, traps) will be made available in each PA for gamekeepers and estate staff to use to assist them in implementing the Land Managers’ Scottish Wildcat Conservation protocol. In doing this, the Project Officer will also ensure that information collected on wildcats and feral cats is integrated with the project’s on-going monitoring and recording work.

2.2.2.3 Promoting uptake of SRDP wildcat option

The Scottish Rural Development Programme (SRDP) was launched in 2015 and included an option for support to landowners for uptake of the Land Manager’s Scottish Wildcat Conservation protocol. This support will only be available to landowners within the Scottish wildcat PAs. This illustrates the emphasis being placed on these areas by the Scottish Government and illustrates a coordinated approach to wildcat conservation across different initiatives. Part of the Land Management Project Officer’s role is to promote this support and offer advice and guidance on its uptake.

2.2.2.4 Development of an identification and recording app to improve levels of reporting.

See the Monitoring and Communications reports for further details on this.

2.2.2.5 Working with ‘Wildcat Action Ambassador Estates’

We worked with estates that are happy to share their experiences of being involved with SWA and promote the work that they have been involved in as examples of best practice. We also worked with partner organisations to ensure that wildcat conservation became part of the criteria for awards initiatives such as the Wildlife Estates Scotland run by Scottish Land and Estates.

Through this work programme, people learned more about how they can help to conserve wildcats without compromising their ability to carry out their duties. By the end of the project we aimed to have this become the norm amongst land managers in the Wildcat PAs and as such this will persist beyond the end of the project. Land managers benefited from assistance in the form of advice, and access to equipment and will have actively contributed to data gathering. They became part of the wider community of SWA volunteers.

2.2.2.6 Land management actions for wildcats – evaluation

Targets and measures of success are listed in the Action Plan (section 4), but our methods of evaluation of the activities in this work programme will include collecting data on:

- Number of delegates attending training

- Number of land managers and gamekeepers engaging in the project through use of equipment, participation in volunteering programmes

- Level of uptake of wildcat SRDP option

- Level of uptake of project equipment

- Level and quality of records and data submitted through use of project equipment

- Number of ambassador estates

- Feedback from delegates on the training they received and what they were able to do using their new skills

- Feedback from land managers and gamekeepers on how they were able to use project equipment to change how they carry out predator control to benefit wildcats

One particular aspect of estate and farm management that has dramatically influenced wildcat numbers in the past and continues to pose a threat, is the ongoing management of ‘pest’ species. This takes the form of predator control on estates with gamebirds through to smaller scale activities by farmers controlling predators such as foxes or using rodenticides for rodent control.

2.2 Promote wildcat-friendly management of estates

Engagement with estates done on an ‘ad hoc’ basis by Project Officers within individual PAs.

2.3 Delivery of actions

2.3.1 General promotion of the wildcat-friendly predator control

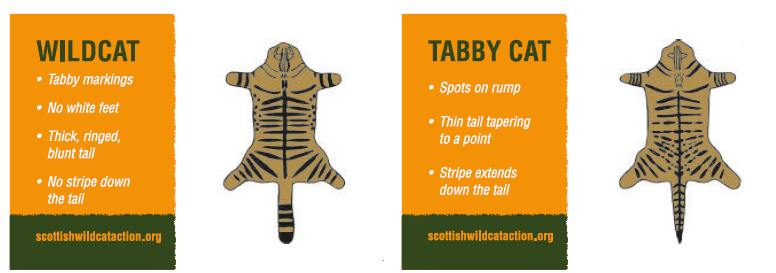

With the help of partner organisations and volunteers, we set up project stands, usually hosted with a land management partner, at key events that would be attended by land managers. These included the Highland Field Sports Fair at Moy, the Scottish Game Fair at Scone and The Black Isle Show. See the Communications report for a full list of events attended. At these events we handed out relevant leaflets (see below) and an overhauled version of the wildcat ID cards originally created for the Cairngorms Wildcat Project. The new ID cards were in colour and in credit-card sized plastic to encourage land managers and gamekeepers to carry them in their pockets (Figure 1).

One side has a pelage drawing show the key characteristics of a wildcat and describes four key characteristics (tabby markings; no white feet; thick, ringed blunt tail; no stripe down tail). The other face shows the same for a tabby domestic cat with three key characteristics (spots on rump; thin tapered tail; a stripe extends down the tail).

We published blogs and articles with land management partners (e.g. Scottish Land and Estate’s (SLE) LandBusiness magazine, British Association for Shooting and Conservation’s (BASC) Shooting and Conservation magazine, and the website of the Scottish Association for Country Sports (SACS). We also collaborated with Athole Design & Publishing Ltd to write a column in their Shooting Scotland magazine throughout 2019. This took the form of an opening article introducing the project and the key issues around wildcat conservation, followed by two articles that drew on the research the partnership was conducting. Firstly, the use of grouse moor by wildcats during summer, as illustrated by the GPS data on a cat in the Angus Glens and written by Dr Kerry Kilshaw of the WildCRU at the University of Oxford. This article highlighted the need to follow the WFPC protocol. Secondly, an article on the risks to wildcats from rodenticide use as revealed by our analysis of cat livers, written by Lydia Peters of The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies at the University of Edinburgh. While this latter piece did not promote the protocol, it introduced another topic relevant to wildcat conservation that game managers could help with.

We worked with the Moorland Forum and Principles of Moorland Management (PoMM) project, now Moorland Management Best Practice (MMBP) to review the WFPC. The main objective of MMBP is to publish guidance as a resource for land managers to help them in their management of moorland and upland areas. Following review, the WFPC was published on the Moorland Forum’s guidance webpage, now the MMBP website.

During the course of the project, we identified a new threat from the use of emerging technologies to assist in predator control. In particular, the use of thermal imaging scopes in place of spotlights for shooting predators could present a high risk to wildcats. We created a guidance leaflet to inform land managers of the risks, along with images taken from thermal imaging scopes (Figure 2) and distributed this to land management partners and at events.

Finally, as part of the #generationwildcat campaign, we created a page on our website that provide some key information to land managers including highlighting the risks from thermal scope assisted shooting and giving links to the WFPC and the Code for Responsible Rodenticide Use (CRRU) (see section 4. below for further details of the latter).

Two thermal scope image showing a cat as a pale shape against a darker background. Coat markings are not distinguishable in the images.

2.3.2 Engagement with estates in PAs

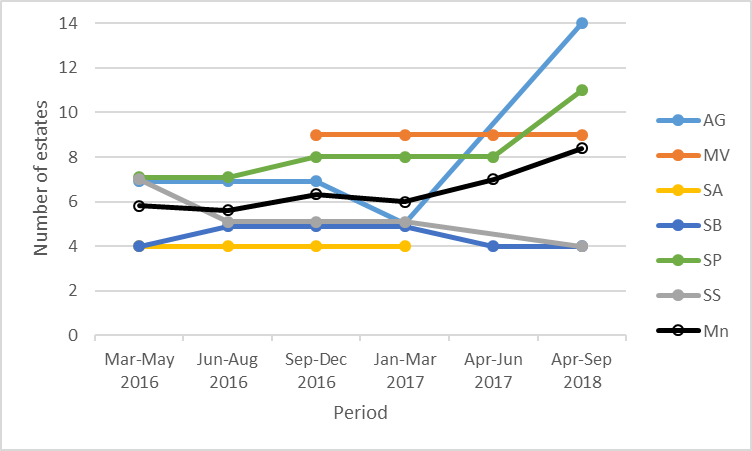

Project staff built relationships with gamekeepers and other estate staff during the course of the project. This we generally instigated through the need for access or help to conduct cat surveys, though the project’s presence at local events also allowed us to make contact with relevant local landowners and managers. Sometimes, finding the right contact proved difficult and partner organisations or estates we had already engaged with were helpful in establishing contact. By the end of the first year, we had already engaged with most of the estates in the PAs (Figure 3). The notable exception to this was in the Angus Glens, where we did not succeed in building relationships with some of the estates until the third year of the project (see 2.3.5). In addition to access for surveys, we discussed with estates the wider wildcat conservation issues and particularly risks from predator control practices such as lamping. Establishing trust with estates and other landowners/managers can take longer however, and where possible we invested time in ensuring that estates received feedback from us, such as sharing with them results of surveys conducted by staff and volunteers on their ground.

Mean per PA is labelled Mn. Note the gap in reporting between July 2017 and March 2018 due to staff investment in cat surveys. A line graph showing the number of estates engaged with over six periods running from March 2016 to September 2018. There are separate lines for each Priority Area and the overall mean number per Priority Area. The overall trend is for increased engagement during this period, though for individual Priority Areas, number of estates varied following the initial engagement process prior to March 2016.

Though we had broad engagement with landowners and land managers, the extent of this varied. With some estates, we developed good working relationships. For example, one estate at the edge of the Strathavon PA asked the Project Officer to help identify several cats captured in cage traps during predator control. Following engagement, several estates adopted WFPC methods and we were asked to help identify captured cats on several other estates across the project’s PAs. Other estates provided access for volunteers to conduct camera surveys, or participated in the surveys themselves, but not all of these allowed us later access to capture cats detected during the surveys, whether for genetic screening and collaring of wildcats or neutering of feral cats and hybrids. The main reason cited for this was that, understandably, the estate conducted predator control and did not want neutered cats released back on to their ground, which they would later need to kill. Indeed, there is a welfare issue around the project trapping and neutering a feral cat if there is a risk it will be killed during later predator control. The project’s policy was that if a feral cat or hybrid were accidentally trapped while attempting to capture a wildcat, the individual would have to be neutered, vaccinated and returned to the point of capture. Thus, estates sometimes refused permission to trap even if we were intending to capture a wildcat. Overall, we found estates in areas with less gamebird management, such as Morvern and Strathpeffer, were more amenable to trapping.

Following GPS collaring data (see the Ecology report) that showed one of the collared cats had moved from forestry ground in winter on to grouse moor in the Angus Glens over the summer, we made contact with the estate on which the cat was living on. Some partners such as SLE also included the story in their newsletters. By the following winter, the cat had returned to the lower forestry ground.

2.3.3 Training for land managers

Project staff provided individual informal training for land managers in PAs. We approached Northern College, University of the Highlands and Islands (Thurso) to establish what additional training or resources could be provided by SWA. However, UHI already incorporate advice on avoiding impacts on wildcats so we did not pursue this further. Nevertheless, the rarity of wildcats relative to hybrids, found through the project’s work, suggests that the levels of experience contained within the game-keeping community in identifying wildcats will be in decline. Ensuring young gamekeepers are familiar with wildcat identification and the WFPC protocol and incorporating these into an online training course in future training is needed. To this end, NatureScot, SLE and BASC are working to create an online training tool to be completed in 2021.

2.3.4 Resources for land managers

Between March 2016 and September 2018 we kept a project-wide record of loans of traps and cameras to estates for the purpose of WFPC, which showed that we typically loaned equipment to only a small number of estates (Table 2). Those provided with cameras were given wildcat identification guidance and could contact project staff for help in identifying cats if needed. In addition, staff with many more of the estates were loaned cameras for our winter surveys, which are not included in Table 2. Only in Strathavon and Strathspey did we not lend any cameras and traps to staff for the proposes of land management.

|

Period |

Angus Glens |

Morvern |

Strathavon |

Strathbogie |

Strathpeffer |

Strathspey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mar-May 2016 |

1 |

- |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

Jun-Aug 2016 |

0 |

- |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

Sep-Dec 2016 |

0 |

- |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

Jan-Mar 2017 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Apr-Jun 2017 |

- |

0 |

- |

1 |

0 |

- |

|

Apr-Sep 2018 |

0 |

3 |

- |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2.3.5 SRDP and uptake of WFPC protocol

The WFPC option under the upland, peatland, moorland and heath category under the Scottish Rural Development Programme offered £140 per trap per year, with up to 20 cage traps and 20 camera traps per contract. Applicants needed to submit a predator control plan and, if successful, keep records of locations, dates and captures of wildcats. It was intended that estates apply for the option as part of a wider set of funding options available under the upland, peatland, moorland and heath theme. Only one estate applied for this option and, because they did not consult with the project beforehand, their application was unsuccessful.

To evaluate why there was no successful uptake of the option, we conducted an online questionnaire survey of landowners in late 2019. The survey was promoted through land management partners and we received 15 responses. Of these, 11 (73%) provided post codes that were within or adjacent to one of the six initial PAs and nine (60%) had land within one of the five PAs active at the time of the survey. Overall, 78% of estates with land within a PA were aware of the project. The main reason given for not applying for the SRDP option was lack of awareness (Table 3). Two other main reasons were that they already conduct WFPC (both respondents who ticked this were also unaware of the SRDP option) or that the contract requirements were too onerous, though one respondent also thought the application process was too difficult and the payment too low. All seven who answered stated they would reconsider applying in the future if the option was revised.

|

Reason |

% |

N |

|---|---|---|

|

I was not aware of the funding option |

63% |

5 |

|

Wildcat Friendly Predator Control is already undertaken on my property |

25% |

2 |

|

My property is not within a priority area |

13% |

1 |

|

I did not know/ think that the wildcat needed protection |

0% |

0 |

|

The application process is too difficult |

13% |

1* |

|

The payments are too low |

13% |

1* |

|

The contract requirements are too onerous |

25% |

2* |

|

I cannot use the option on the land type where it is required |

0% |

0 |

* One respondent ticked all three of these reasons

Our own informal review of the SRDP option in collaboration with NatureScot highlighted that there could be a mismatch between where the option can be used and where it would be most effective: the trapping should be conducted on a holding eligible moorland, but in winter when trapping is most successful, wildcats are much more likely to be resident to forests and other cover habitats. This was not identified by any of the survey participants as an issue, however. It is possible that the reason for this is because it is not obvious that this restriction is in place (it arises because the WPFC option sits within the upland, peatland, moorland and heath category).

Nevertheless, it is apparent from the lack of awareness of the option evidenced in the survey that we would have needed to invest many more resources into promoting the option to landowners, land managers and land agents. For example, the Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels project achieved higher levels of take up of the grey squirrel control SRDP option, with 197 landowners receiving funding up to 2013 (Bryce and Tonkins, 2019). This was achieved at least in part by investing staff time in promoting the option and dedicating staff resources to leading applicants through the application process (J. Bryce, pers. comm). In order to achieve similar successes, SWA would have needed to reduce staff activities on other areas such as TNVR and monitoring.

2.3.6 Further trialling of the WFPC protocol

By 2018 engagement with WFPC remained low. We established a land management subgroup consisting of project staff and partners from land management organisations (BASC; CNPA; FLS; Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT); John Muir Trust (JMT); SACS; SGA; SLE). One task agreed with the subgroup was to involve gamekeepers in a trial of the WFPC method to inform its future development and encourage uptake of the protocol. Seven gamekeepers in the Angus Glens were involved and the trial took place over the summer. Feedback indicated that some gamekeepers may not be confident enough to identify wildcats in traps and future work could include developing a wildcat identification training video.

2.4 Overall assessment of the wildcat-friendly predator control work stream

We established a good relationship with most estates within our PAs and raised the profile of the wildcat in relation to game management through events and publications. The only negative feedback from estates we experienced was around the provision of feedback on our surveys results after each winter. Feedback could be delayed due to the volume of data and further curtailed following staffing changes. Employing a full-time data officer to assist in the collation of survey data may have helped as this was a significant task (see the Monitoring report). We achieved legacy through the distribution of robust wildcat ID cards, ensuring the protocol was available on the Moorland Management Best Practice webpage and from the nascent online training tool for land managers. We achieved less success in encouraging uptake of the wildcat SRDP funding option and increasing the use of the WFPC protocol generally. In order to improve on this, we needed to invest more staff resources away from the surveys and TNVR activities into promoting land management protocols through training, SRDP funding and promoting ambassador estates. Establishing the land management sub-group in the first year of the project would have assisted in this, for example through helping the project staff build relationships and assisting in the delivery of training days. However, having estates in the Angus Glens trial using the protocol is a positive first step and future work will need to concentrate on increasing the uptake of the protocol through encouragement and/or funding support.

2.4.1 Future improvements to the game management with wildcats

- Predator control around pheasant shoots (e.g. around rearing pens) presents a risk to wildcats not identified previously. For example, a significant proportion of queries from gamekeepers after they had trapped possible wildcats in cage traps were around pheasant pens.

- The Wildlife Estates Scotland (WES) accreditation scheme was on a hiatus during the project, but has since been relaunched. Incorporating the WFPC and habitat management for wildcats (e.g. the latter as part of a woodland management plan, see Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice) into the scheme should be explored.

- Many estates have tenanted land and the SWA messages would benefit from being promoted by the estates to their tenants.

- On occasion, the project’s activities could appear to be in conflict with other conservation activities. For example, releasing neutered cats may superficially appear to contradict some of the aims of the ‘working for waders’ project (though in reality, TNVR is a tool to reduce feral and hybrid cat populations and so does not contradict predator reduction aims). Nevertheless, the difficult issue of cat management needs to be addressed across conservation projects to ensure a cohesive approach is taken.

3. Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice

3.1 Background

Forest habitats are important for wildcats in Scotland and across their European range. Survey work before and during the SWA project found that a large proportion of the remnant population of potential wildcats was associated with commercial plantations and other woodlands. Publicly owned forests, managed by Forestry and Land Scotland, were important in this regard. This is probably because these sites have served as predator control-free havens for wildcats for decades and offer contiguous areas of cover in increasingly fragmented landscapes.

As part of the SWCAP land management actions, Scottish Forestry (SF, formerly Forestry Commission Scotland) and FLS (formerly Forest Enterprise Scotland) committed to actions under Project 2.3: Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice. The impact of forest management on wildcats is not fully understood, so improving our understanding is a key aspect of the work undertaken by FLS.

SF undertook to revise and promote their existing guidance note on forestry operations and wildcats. This note has limited scientific or management experience underpinning it, and was based on best available knowledge at the time of publication. Given that the note was published in 2009, and that knowledge of wildcats in Scottish forests has increased significantly thanks to the SWA project and other research, a revision of the note is overdue.

FLS undertook to carry out trials of a limited range of habitat management measures on the national forest estate. However, given that GPS tracking information indicates that potential wildcats spend significant amounts of time in managed forests, it was decided that the first and most valuable action would be to understand the relative importance of different parts of a commercial plantation on the availability of potential wildcat prey. Therefore, surveys of rodent prey were carried out in Clashindarroch Forest in the Strathbogie PA. The long-term aim was to gather knowledge on food (rodent) availability within the forest, relate this to observed habitat use by wildcats, and use all of the information to influence forest design for the benefit of wildcats.

The creation and monitoring of artificial dens was another key action. It was hypothesised that the provision of artificial dens had the potential to enhance wildcat conservation within productive forests. Wildcats are a European Protected Species and are protected under The Conservation (Natural Habitat, &c) Regulations, 1994, and as such are afforded strict legal protection. It is an offence to disturb an animal while it is occupying a structure or place used for shelter or protection; to disturb an animal while it is rearing or otherwise caring for its young; or to obstruct access to a breeding site or resting place, or otherwise deny an animal use of a breeding site or resting place.

Given this protection, the forestry sector is trying to develop methods to reconcile wildcats with forest management activities, which have the potential to contravene the legislation, albeit unintentionally. The key problem is that breeding sites and resting places (henceforth called ‘dens’) are difficult to locate. Data from WildCRU’s GPS tracking of wild-living cats and from other GPS studies on wildcats have shown that wildcats use several den sites throughout their home ranges (see the Ecology report). If wildcats were to use artificial dens, it would be possible to create such features at suitable locations within forests, and subsequently plan forest management activities to avoid these known locations. This would reduce the likelihood of contravening legislation protecting wildcats.

In Scotland gamekeepers used to build artificial dens in drystane (dry stone) dykes on grouse moors, for the purpose of attracting and then trapping predatory mammals. These artificial dens regularly attracted wildcats (K. Peters, pers comm.). Furthermore, there is a view that, given the increase in badger (Meles meles) and fox (Vulpes vulpes) populations, den sites may be limiting for wildcats (R. Dennis, pers comm.). For these legal and anecdotal reasons, FLS undertook to create and monitor a number of artificial dens.

A photo taken in Clashindarroch forest showing an open grassy area with long grasses and herbs along a watercourse, surrounded by mature conifer plantation with some spruce regeneration around the margins.

Improving pre-operational surveys and mitigation measures was an objective of the SWCAP. Although the evidence and research that is available strongly suggests that wildcats and timber production are largely compatible, there remains an unquantified risk of direct harm to wildcats and the legally protected structures they use. Based on the spatial and temporal scales of use of plantations by wildcats, and the dispersed and limited annual extent of timber-harvesting operations, the chances of direct harm to wildcats is likely to be low. However, a risk exists and FLS, and the forestry sector more generally, are keen to reduce the risk to an absolute minimum. To this end, FLS staff managing Clashindarroch worked with SWA field staff and biologists, plus the WildCRU biologist, who was actively tracking wildcats, to improve pre-operational surveys and associated mitigation.

During the SWA project, FLS commissioned additional survey work close to the Angus Glens PA, based on recommendations from local wildcat enthusiasts, and volunteers surveyed various Aberdeenshire forests (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). Further survey work will be carried out wherever wildcat sightings are reported.

3.2 Agreed actions

Actions and lead partners identified to deliver project 2.1, ‘Promote wildcat-friendly predator control protocols in PAs’ can be seen in Table 4 below.

|

Actions |

Action Plan Numbering |

Action Leads (as of 04/2017) |

|---|---|---|

|

ACTION IN PRIORITY AREAS |

2 |

- |

|

Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice. |

2.3 |

- |

|

Revise and promote SF guidance on forestry operations and wildcats (including habitat management for wildcats). |

2.3.1 |

SF |

|

Carry out trials of a limited range of habitat management measures on the National Forest Estate, e.g. assess the benefits of extended fallow periods on restock sites, creation of brash piles and artificial den sites. |

2.3.2 |

FLS |

3.3 Delivery of actions

3.3.1 Action 2.3.1: Revise and promote Scottish Forestry guidance on forestry operations and wildcats

FCS Guidance Note 35d (Forest operations and wildcats in Scotland) was assessed and the content compared against the recent published literature and continuing wildcat research. During this process an immediate need for a guidance note for front-line staff working on tree-felling operations was identified.

3.3.2 Actions 2.3.2: Carry out trials of a limited range of habitat management measures on the national forest estate

3.3.2.1 Rodent prey surveys

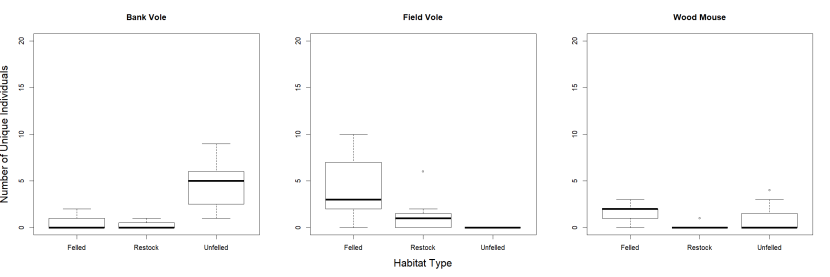

Information on what determines the presence of the wildcat in Scotland is limited, but prey availability is likely to be an important aspect (Corbett 1979; Monterroso, Brito, Ferreras and Alves, 2009). The wildcat’s primary prey is small mammals, especially where rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is less abundant (Hewson 1983). Previous and continuing research shows that wildcats tend to use open areas and clear fells in plantations, because these are grassier and support small mammal prey (Campbell 2015; Scottish Wildcat Action, 2017; K Kilshaw pers comm.). Short-tailed field vole (Microtus agrestis; henceforth called field vole) is one of the species found in these clear fells (definition according to Sibbald et al., 2006: ungrazed grassland and young forestry plantation), making it a potential prey species for the wildcat. Less is known about the habitat use of two other rodent prey species in commercial plantations in Scotland – the bank vole (Myodes glareolus), and the wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus). To improve and potentially expand suitable habitat for wildcat within plantations in SWCAP PAs, it is important to gain more specific knowledge about rodents in these areas.

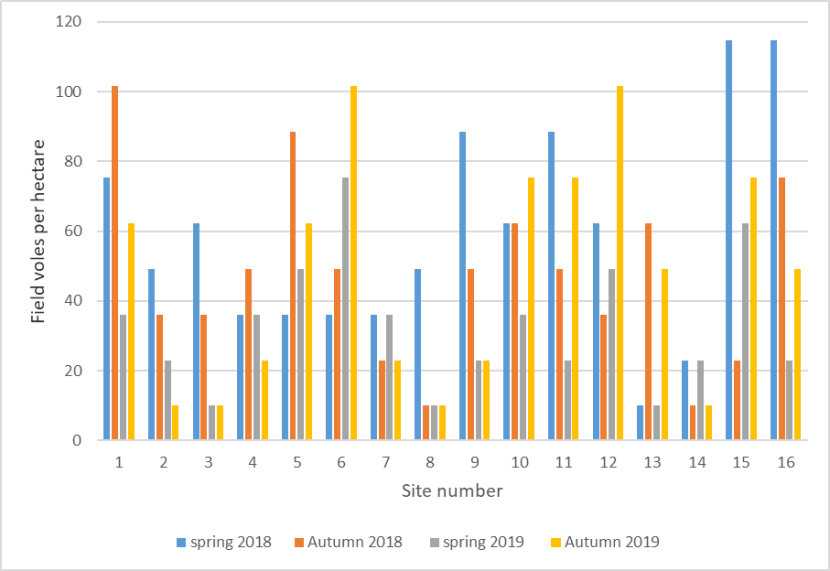

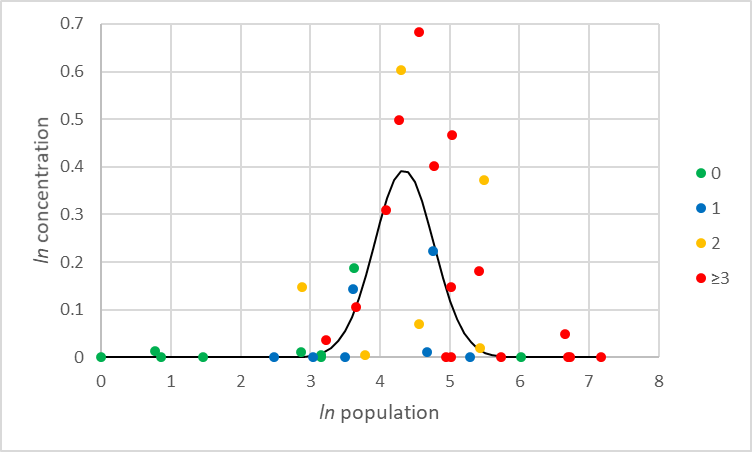

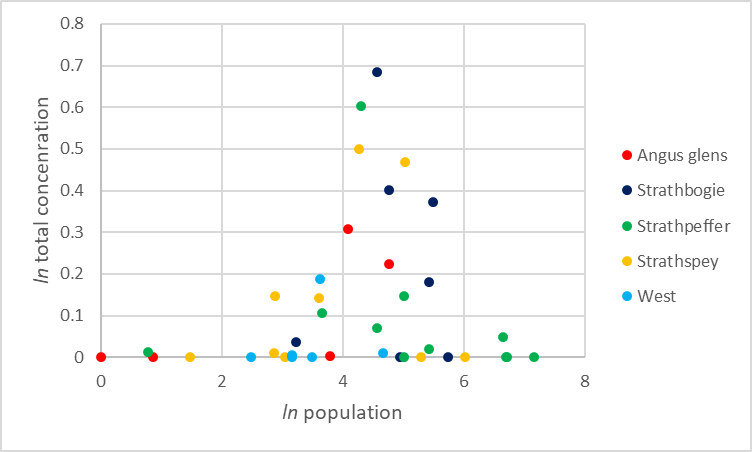

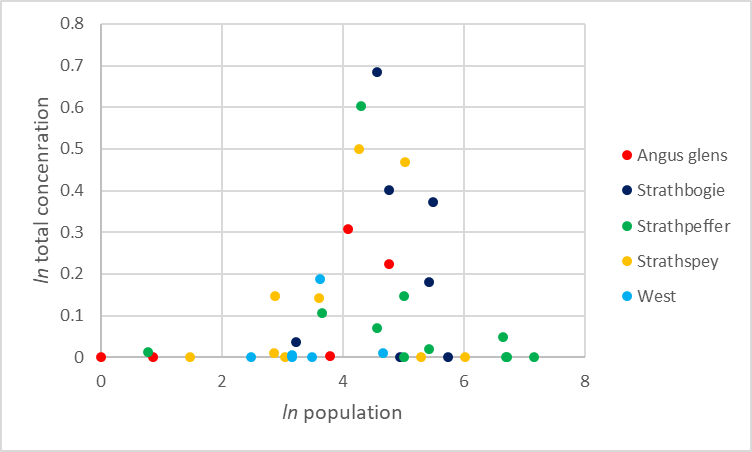

Therefore, the aims of this work were to determine the distribution and relative abundance of three species of rodents in four different habitat types within Clashindarroch forest in the SWCAP Strathbogie PA (Figure 4). The three species of rodent were the field vole, the bank vole and the wood mouse. The four habitat types were unfelled stands of timber, restocked (i.e. replanted) areas, clear fells and permanent open areas. Long-standing commercial plantations like Clashindarroch have large areas of all four of these habitat types.

Vole sign Index method for field vole

The method used for estimating field vole population density is based on the method described in Lambin et al., (2000) and is referred to as the Vole Sign Index (VSI) method. Field voles leave signs in the field in the form of grass clippings, runways and droppings. Sampling areas were in restocks and clear fells, where graminaceous vegetation was growing or well developed. In each sampling area, 25 quadrats were searched for field signs. The quadrats were 25x25cm wooden frames, which were thrown in the direction of suitable vole habitat and searches for signs were carried out where they landed; a constant effort of around 30 seconds was used for each quadrat. When the frame landed on bare ground or wood, it was thrown again. The position of each quadrat was determined by walking 20 paces from the previous quadrat, following the most suitable habitat. Findings of field signs were categorised as fresh droppings, old droppings, fresh grass clippings, old grass clippings and runways. The quantity of field vole signs were then converted to field vole population densities using the VSI.

Live trapping for bank vole, field vole and wood mouse

To obtain an estimate of the bank vole populations, a live-trapping method was used. This method was based on the small quadrat method described by Millymãki et al. (1971). Field signs searches are not suitable for estimating bank vole population density, because this species does not leave adequate signs (Xavier Lambin pers comm.). The small-quadrat method is used for its comparability with studies conducted in Fennoscandia, where it is a regularly used method. This method is also preferable to live-trapping, because each quadrat can be placed on suitable habitat, and is, therefore, more reliable. Traps were set in 15x15m quadrats containing 12 traps. Three Ugglan Special multiple-capture traps (manufacturer: Grahnab, Marieholme, Sweden) were set on each corner of the quadrat. Quadrats were located in seven unfelled stands of timber (Sitka spruce), seven restocked (i.e. replanted) areas, and seven clear fells.

A trapping period consisted of three pre-baiting days, one day for setting the traps and three capture nights. Traps were pre-baited with oats, carrots and peanut-butter (Lambin and Baucha, 1989). On capture days the traps were checked daily (once per 24 hours). To prevent by-catch and deaths of shrews, every trap was equipped with a 12mm hole. The influence of these shrew exits was studied by Eccard and Klemme (2013): the number of shrews caught in their experiment went down from 31 to 0, while the number of caught bank voles was not affected.

Two vole monitoring projects ran concurrently and were managed by FLS:

Project 1

This project employed the VSI method and sampled permanent open habitats within Clashindarroch. Surveys were carried out in spring and autumn 2018, and spring and autumn 2019. The intention is to continue to carry out these twice-yearly surveys on an ongoing basis, in order to quantify the magnitude of fluctuations in the population.

Project 2

This project used live trapping to sample bank voles, field voles and wood mice in unfelled stands of timber, restocked (i.e. replanted) areas and clear fells. The aim was to determine the distribution and relative abundance of three species of rodents in the three different habitat types. Project 2 was carried out in 2018.

3.3.2.2 Creation and monitoring of artificial dens

Several kinds of artificial dens were created, using stones and boulders, wooden boxes, logs, brash (branches left after felling), and mixtures of these materials. The brash dens and box-log-brash dens were constructed as part of pre-programmed felling operations, because this would be the standard method of construction if the artificial dens were found to be of value for wildcats. The prefabricated box dens were ordered from and constructed by Wood Recyclability Ltd., a local social enterprise company. They were deployed in various places in Clashindarroch, both on and off the ground. Some dens in Glen Isla were constructed by hand by volunteers. Some examples of the various artificial dens are shown in Figure 5-Figure 8 below.

Two photos showing the construction of a log, box and brash den in Clashindarroch forest. The first photo shows the den box set on top of logs lying on the ground and the second photo shows the box den covered with brash (branches from felled conifers).

A photo of a box den placed on the ground in Clashindarroch, set within an area of wind-blown young conifers.

A photo of a box den placed on the ground in Clashindarroch, set within an area of wind-blown young conifers.

Photo of the completed stone and pipe den. The three pipes have been covered by stones that have fallen from the old stone dyke so that the den is not visible.

Camera traps were deployed to detect and monitor wildcat usage of a sample of 17 of the artificial dens: two of the wooden boxes in Clashindarroch (Figure 6), and 15 of the hand-constructed artificial dens in Glen Isla (Figure 8).

3.3.2.3 Improving pre-operational surveys and mitigation measures

FLS Environment staff worked with SWA field staff and wildcat biologists to develop and improve pre-operational surveys for wildcats, and to enhance mitigation measures to lessen the potential impact of forest operations on wildcats. The focus of this work was in Clashindarroch Forest, where SWA field staff and biologists spent time in the field with FLS Environment Rangers and other staff, training them on wildcat detection, ecology and conservation.

Discussions were held between SWA staff and FLS Environment, Planning and Operations staff about what additional wildcat conservation measures were compatible with timber-harvesting programmes, and what new mitigation could be enacted on a trial basis. SWA camera-trapping and GPS collar data were shared with FLS staff to inform operational decision-making.

3.3.2.4 Additional wildcat surveys on FLS land

During 2018, camera trap-based surveys for wildcats were conducted on additional FLS sites. One set of surveys was conducted by an experienced contractor in Strathardle, approximately 10km west of the Angus Glens PA (Ross, A. 2018), during winter and spring 2018. Another set of surveys were conducted by experienced students on a scholarship funded by the Spanish Government, deploying camera traps in areas in Aberdeenshire (Villar and González, 2019). Camera-trap locations were at least 300m apart, spread throughout the forest blocks. At each location two camera traps were deployed in order to improve detection. Results of both these surveys are summarised in the Monitoring and Surveys report.

3.4 Results

SWCAP Project 2.3: Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice

3.4.1 Action 2.3.1: Revise and promote Scottish Forestry guidance on forestry operations and wildcats

The revision of FCS Guidance Note 35d (Forest operations and wildcats in Scotland) was deferred pending the results of the WildCRU GPS-tracking study of wildcats in forest habitats and other work.

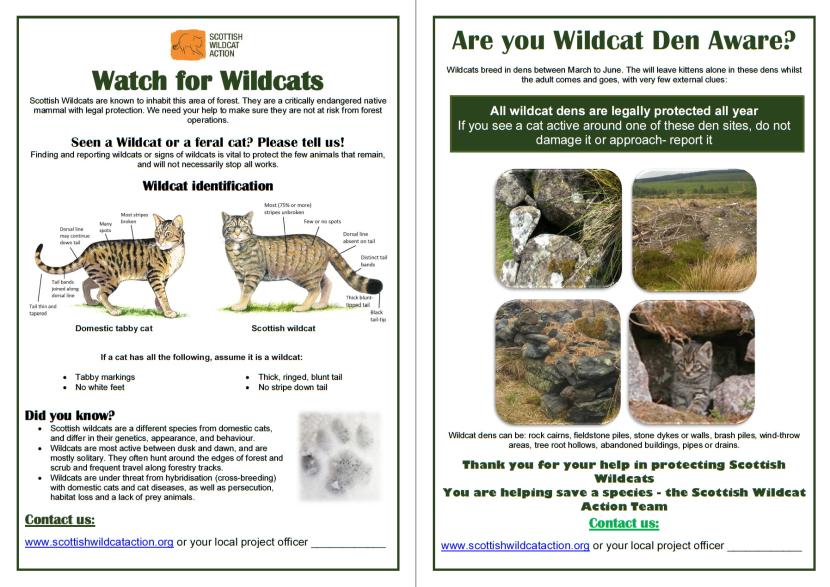

As an additional and interim measure, SWA and FLS staff produced a leaflet for forestry contractors working in forests containing wildcats (Figure 9). This has been distributed to all forestry contractors and all relevant FLS operational staff – over 50 people in total. In addition, SWA staff and FLS Environment staff spoke face-to-face and on-site with all FLS staff and contractors working in the Strathbogie and the Angus Glens PAs.

Image of the two-page guidance not for FLS forest operations staff and contractors. Side 1 (titled ‘watch for wildcats’) shows annotated images of a wildcat and a domestic tabby to help in wildcat identification; lists three key facts for forestry workers alongside the image of a cat paw-print in snow and has SWA contact information. Side 2 (titled ‘are you wildcat den aware?’) stats that wildcat dens are protected; shows four photos of typical wildcat dens in forestry environments (within stone dykes and under brash piles) including one with a possible wildcat kitten; thanks forestry workers for their help and again provides contact details for the project.

3.4.1.1 Rodent prey surveys

Project 1

|

Area |

Spring 2018 |

Autumn 2018 |

Spring 2019 |

Autumn 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

75.46 |

101.66 |

36.16 |

62.36 |

|

2 |

49.26 |

36.16 |

23.06 |

9.96 |

|

3 |

62.36 |

36.16 |

9.96 |

9.96 |

|

4 |

36.16 |

49.26 |

36.16 |

23.06 |

|

5 |

36.16 |

88.56 |

49.26 |

62.36 |

|

6 |

36.16 |

49.26 |

75.46 |

101.66 |

|

7 |

36.16 |

23.06 |

36.16 |

23.06 |

|

8 |

49.26 |

9.96 |

9.96 |

9.96 |

|

9 |

88.56 |

49.26 |

23.06 |

23.06 |

|

10 |

62.36 |

62.36 |

36.16 |

75.46 |

|

11 |

88.56 |

49.26 |

23.06 |

75.46 |

|

12 |

62.36 |

36.16 |

49.26 |

101.66 |

|

13 |

9.96 |

62.36 |

9.96 |

49.26 |

|

14 |

23.06 |

9.96 |

23.06 |

9.96 |

|

15 |

114.76 |

23.06 |

62.36 |

75.46 |

|

16 |

114.76 |

75.46 |

23.06 |

49.26 |

A bar chart of the Vole Sign Index converted to field vole population densities for 16 sites in Clashindarroch recorded in spring and autumn 2018 – 2019. It shows that the vole density is highly variable between sites, seasons and years, but that some sites had consistently greater densities than others.

No clear trends or partial cycles were apparent in the field vole population after two years of monitoring. Some of the 16 survey sites appeared to support more field voles than others, though all sites supported 20 voles per hectare in at least one site×season measure. Field vole population densities in these permanent open areas surveyed within Clashindarroch varied from about 10 voles per hectare to almost 115 voles per hectare. In 54 out of the 64 site×season measures, field vole population densities were in excess of 20 voles per hectare. In half of the site*season measures, field vole population densities were in excess of 50 voles per hectare.

Based on a weight of 25g, and using the mean population densities for each season, derived from Table 5, the following biomasses of field voles were available to wildcats in open areas in Clashindarroch:

Spring 2018: 1.48 kg ha-1

Autumn 2018: 1.19 kg-1

Spring 2019: 0.82 kg-1

Autumn 2019: 1.19 kg-1

Project 2

|

Quadrat |

Habitat type |

Bank vole |

Field vole |

Wood mouse |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 in 1 Felled |

Felled |

1 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

|

3 in 1 Felled part 2 |

Felled |

2 |

10 |

2 |

14 |

|

3 in 1 Restock |

Restock |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

3 in 1 Restock Part 2 |

Restock |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Craigie Beg 1 |

Unfelled |

9 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

Craigie Beg 2 |

Unfelled |

5 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

Craigiebeg 1 Part 2 |

Unfelled |

1 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

|

Craigiebeg 2 Part 2 |

Unfelled |

7 |

0 |

4 |

11 |

|

Craigiebeg Carpark |

Unfelled |

5 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

Longbank 2 Down |

Restock |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Longbank Down |

Restock |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Picadilly |

Unfelled |

4 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Picadilly 2 |

Unfelled |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Pretty |

Felled |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Pretty Part 2 |

Felled |

0 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

|

Red Deer |

Felled |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

Red Deer Part 2 |

Felled |

0 |

7 |

3 |

10 |

|

Upper Burnfell |

Felled |

1 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

|

Upper Longbank |

Restock |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

|

Upper Longbank 2 |

Restock |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

Spiny Bark |

Restock |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Grand Total |

|

38 |

41 |

19 |

98 |

Three box and whisker plots (one each for bank vole, field vole and wood mouse) showing the mean number of unique individuals captured (0-20) during live trapping in felled, restock and unfelled sites. Bank voles show low numbers in felled and restock sites and more in unfelled sites. Field voles show most in felled sites, some in restock sites and very few in unfells sites. Wood mouse show very few in restock sites and some in both felled and unfelled sites.

All three species of rodent were found in all three forest stand types, but in different numbers (Figure 11). Bank voles were the most common in unfelled stands. Field voles were the most common in felled areas and restocks. Wood mice were found in all three habitats, but were not the most common species in any of the three habitats.

3.4.1.2 Creation and monitoring of artificial dens

A total of 63 artificial dens were constructed; 30 in the SWCAP Angus Glens PA and 33 in the SWCAP Strathbogie PA (Table 7).

|

Priority area |

Site(s) |

Den type |

Number |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Strathbogie |

Clashindarroch, Ardonald, Gartly, The Bin |

Prefabricated wooden boxes |

10 |

|

Strathbogie |

Clashindarroch |

Machine constructed with logs, box and with brash cover |

3 |

|

Strathbogie |

Clashindarroch, Ardonald, Gartly, The Bin |

Deadwood piles constructed during forest operations |

20 |

|

Angus Glens |

Glen Isla |

Hand-built with stone and pipe, or windblown wood |

15 |

|

Angus Glens |

Glen Isla |

Brash piles created during forest operations |

9 |

|

Angus Glens |

Glen Doll |

Brash piles created during forest operations |

6 |

Up to 25 camera traps at a time, some in pairs, were deployed on 15 artificial dens in Glen Isla (Angus Glens) between November 2018 and October 2019. In total 10,450 camera-trap days were achieved. In Clashindarroch two wooden boxes were monitored with two camera traps for a total of 40 camera-trap*days. An overall total of 10,490 camera-trap days of monitoring was carried out.

No cats of any kind were recorded going into or out of any of the dens. Several cats, including wildcats, were recorded on camera traps close to, or even on top of, a small number of the dens (e.g. Figure 12). A wildcat and kittens were recorded using a roadside timber stack for several days. This timber stack was located close to a few artificial dens (hand-built stone/pipe dens, and brash piles), but these were not used.

Two photos. The top photo is a colour daytime camera trap image shows a tabby marked cat with a thick, blunt, tail walking on top of an artificial den set within a stone dyke in the Angus Glens. The bottom photo is a monochrome night-time still from a camera trap video showing two kittens under a log pile laid over a ditch. One kitten shows mackerel tabby markings that might indicate it is wildcat (though it is not possible to confirm from pelage at such a young age). The other kitten shows blotch-tabby markings which clearly indicate the kitten is not a wildcat.

3.4.1.3 Improving pre-operational surveys and mitigation measures

FLS Environment staff, SWA field staff and wildcat biologists spent over 30 days working together in the field in Clashindarroch, refining pre-operational surveys and exchanging knowledge. FLS staff received continuing training on effective camera-trap deployment and on detecting wildcat field signs, breeding sites and resting places. SWA staff also advised FLS Environment staff on operation-specific mitigation in Clashindarroch. This enhanced the capability of FLS staff to enact effective conservation and mitigation for wildcats via a wildcat data-based risk assessment process.

Discussions were held between SWA staff and FLS Environment, Planning and Operations staff about what additional wildcat conservation measures were compatible with timber-harvesting programmes and what new mitigation could be enacted on a trial basis. Starting in early 2018, the following measures were enacted on a trial basis in Clashindarroch:

- Camera traps were deployed on harvesting sites at least six months prior to any forest management

- Tagging data from the WildCRU wildcat GPS tracking project were used to inform management

- No clear felling in Clashindarroch between March and June inclusive

- No thinning operations in Clashindarroch between March and June inclusive

- Operations only carried out where no evidence of wildcats was found on a site

- Prior to any operations beginning in Clashindarroch Forest, all operators were briefed on the presence of wildcats and were provided with an FLS/SWA interim guidance note

- All contractors and operators and FLS staff working in Clashindarroch Forest were asked to remain vigilant and to report any sightings of wildcats. Standard operating procedures on the sighting of a wildcat was to stop all work and report it immediately to the FLS Environment team

- If evidence of wildcats was found, operations were deferred

- All potential dens (e.g. rock piles) were protected from damage at all times

- From August 2019 mounding operations were restricted to out-with the breeding period

- FLS staff and contractors record all wildcat sightings and signs

This trial is continuing and similar approaches have been adopted in all FLS forest blocks known to have populations of wildcats.

3.4.1.4 Additional wildcat surveys on FLS land

During the Strathardle survey, one potential wildcat, though it was likely a hybrid, and one feral domestic cat were recorded in Kindrogan, and one unknown cat was recorded at Dalrulzion (Ross, A. 2018). The surveys in the Aberdeenshire blocks (Villar and González, 2019) failed to locate any cats with high pelage scores within FLS forest blocks, though one potential wildcat was detected elsewhere (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). Two hybrids and nine feral or domestic cats were detected across three of the forest blocks. No cats at all were detected in Pitfichie.

3.5 Overall assessment of forestry management work stream

SWCAP Project 2.3: Promote wildcat-friendly forestry practice

3.5.1 Action 2.3.1: Revise and promote Scottish Forestry guidance on forestry operations and wildcats

The deferral of the revision of FCS Guidance Note 35d (Forest operations and wildcats in Scotland), pending the results of the WildCRU GPS-tagging study of wildcats in forest habitats, is sensible as it will avoid doing an inadequate revision, followed soon after by a second revision. The delay will be well worthwhile, because the WildCRU research is shedding new information, at unprecedented resolution, on wildcat behaviour within plantations and, in combination with other work, will result in a hugely improved guidance note.

The additional and new SWA/FLS leaflet for forestry staff and contractors, and continuing face-to-face dialogue between SWA/FLS staff and forestry workers, have raised awareness significantly among key personnel in the meantime. It has been apparent that forestry workers are amenable to helping with wildcat conservation and efforts to engage with them will continue.

3.5.1.1 Future work

1. Use the results of the SWA project findings and the WildCRU wildcat GPS-tracking project as a basis to revise FCS Guidance Note 35d (Forest Operations and Wildcats in Scotland) in late 2021 or early 2022.

2. FLS staff and SWA volunteers to continue to liaise and work with forestry personnel to protect wildcats in managed forests.

3.5.2 Action 2.3.2: Carry out trials of a limited range of habitat management measures on the national forest estate

3.5.2.1 Rodent prey surveys

Project 1 showed that field vole population densities in permanent open areas were substantially lower than those in Kielder Forest, which is a comparable site in England. There, densities of 200 to 765 voles per hectare were recorded at the peak of the vole cycle (Lambin et al., 2000; Ergon et al., 2011). It may be that the field vole population in Clashindarroch is currently at the low point of the cycle and will increase in the near future to levels closer to those in Kielder.

However, despite being lower than Kielder, the field vole population densities in Clashindarroch were comparable to vole population densities reported in broadleaf woodland and hedgerows (Flowerdew et al., 2004) elsewhere in the UK. Very rough calculations indicate that, on average, about 1 kg per hectare of field vole biomass is typically available to wildcats in permanent open areas in Clashindarroch.

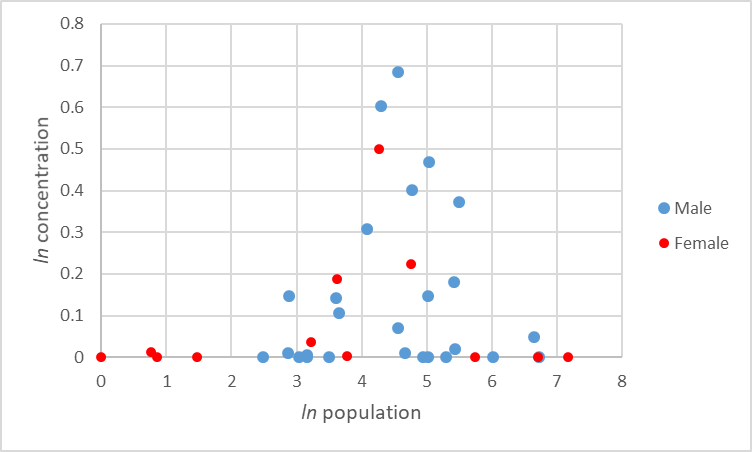

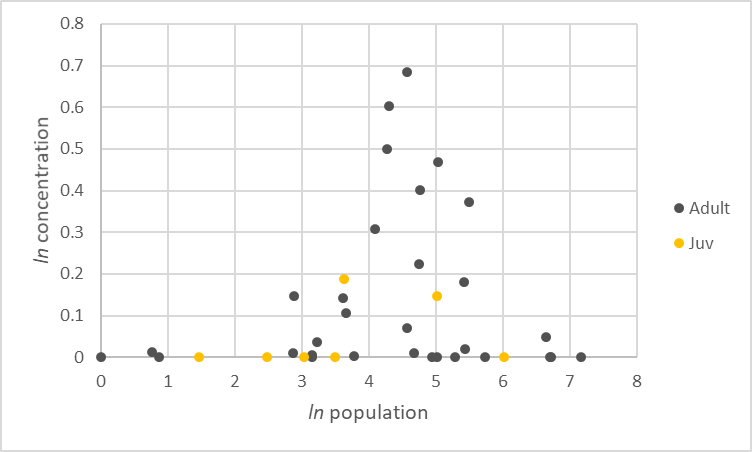

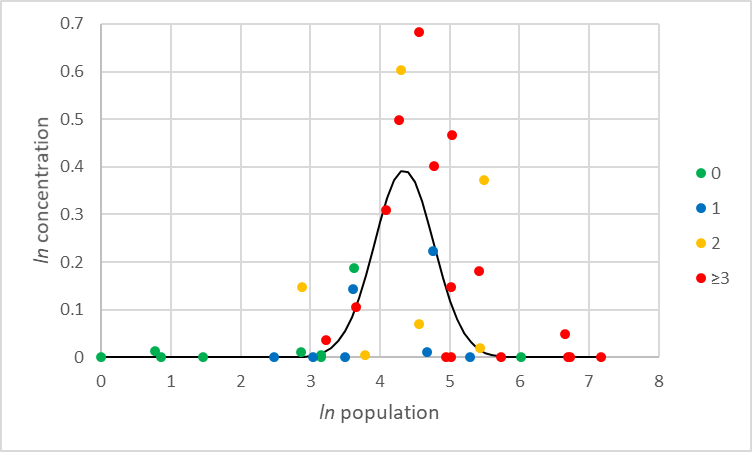

Project 2 showed that rodent prey was present in all three surveyed habitat types (unfelled, restocked and clear fells). However, although bank voles were present in the forest, and are a suitable prey species for wildcats, they occur in habitats that are not suited to wildcat hunting, i.e. unfelled and un-thinned stands, including Sitka spruce. They are known to climb well and spend time several metres up trees eating bark, especially in winter. Therefore, bank voles are probably less available to wildcats than field voles.