Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) Specialist Report - Trap Neuter Vaccinate Return Programme

This report should be cited as: Campbell, R.D., Rawling, E., Langridge, K.V. and Tallach, N. (2023). Scottish Wildcat Action final report: Trap Neuter Vaccinate Return Programme. NatureScot, Inverness.

Authors and institutions: Roo Campbell, Scottish Wildcat Action, Emma Rawling, Scottish Wildcat Action, Keri Langridge, Scottish Wildcat Action, Nicola Tallach, Scottish Wildcat Action.

Year of publication: 2023

Keywords

Feral cat management; neutering; trapping; hybridisation; disease; volunteers; farm cats.

Background to SWA

The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP) was published in 2013 following the input of over 20 partner organisations. This led to the establishment of the Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) project that ran from 2015-2020, funded by the Scottish Government, National Lottery Heritage Fund and others. SWA operated with a team of project staff managed by NatureScot, and associated work was carried out by various partner organisations. The overall work programme was steered by a group made up of ten of the partners. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Cat Specialist Group reviewed the work of the SWA, and other ongoing wildcat conservation work, and provided recommendations for future action (Breitenmoser et al., 2019). A wide range of topics relevant to wildcat conservation were covered during the SWA, and have now been published as a series of reports, of which this is one. These outputs will inform the next phase of wildcat conservation work in Scotland, including the SavingWildcats ‘SWAforLife’ project that runs from 2019-2026.

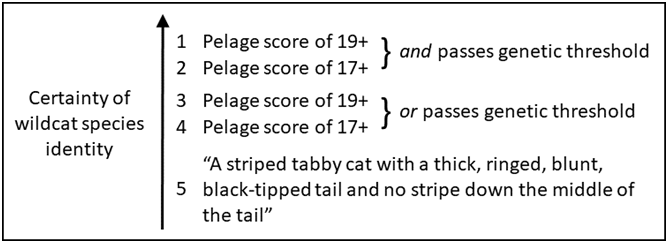

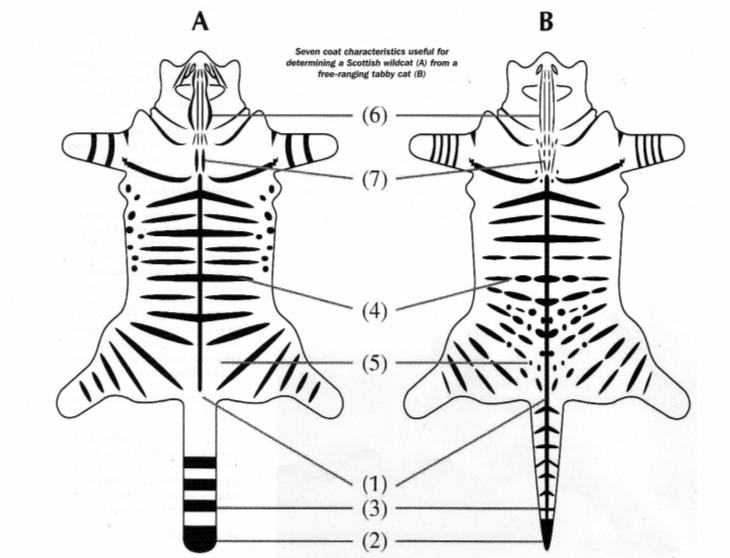

Wildcats hybridise with domestic cats and we use a combination of morphology and genetics to distinguish wildcats from domestic cats and their hybrids. The method applied is generally determined by the practicalities of management. For example, it is much easier to have high confidence in the pelage scores from a sedated cat, than from a camera-trap image taken at night. Genetic and pelage results can only be generated jointly in certain scenarios. Therefore, identifications under different situations have different levels of confidence associated with them. We therefore set different thresholds for identification of wildcats based on the ability to distinguish pelage and genetic characteristics in different situations. The confidence hierarchy, and the definitions used in this report, are given below

A graphic showing increasing certainty of wildcat identity over five levels as more information on pelage and genetic status are available.

It reads:

Unless described otherwise, a wildcat in this report is defined as a cat with a 7PS pelage score of 19+ and/or that passes the genetic threshold for the genetic analyses. The consequences of applying different thresholds in different situations and management regimes are also examined.

A 'wildcat' in this report is defined at level 4 as a cat with a 7Ps pelage score of 17+. Genetic information is not available prior to neutering unless a cat has been sampled previously.

Background

Hybridisation with, and disease transmission from, domestic cats have been identified as key threats to wildcats in Scotland. As companion animals, the management of domestic cat populations via lethal or non-lethal methods is highly controversial. Scottish Wildcat Action adopted a non-lethal approach to feral domestic cat population management known as Trap, Neuter, Vaccinate and Return (TNVR), whereby cats are live-captured in cage traps, neutered and vaccinated, then returned to the point of capture. TNVR was used because a) it is a proven method of effective cat population control when used intensively in defined areas; b) returning neutered cats to previously held territories may help to prevent the influx of new, unneutered and unvaccinated individuals to wildcat areas; c) gaining wider public support for the conservation aims of the project, including encouraging local communities to voluntarily participate in feral cat control activity, and to neuter, microchip and vaccinate their own pet cats, would be difficult if lethal methods were employed. To achieve long-term changes in the feral domestic cat population, modelling suggests that an annual neutering rate of 75% of the population is required. Domestic cat × wildcat hybrids (hereafter termed ‘hybrids’) were also treated under the TNVR programme if they scored below the pre-defined pelage and/or genetic threshold.

Summary of work

- A detailed TNVR protocol with associated guidance were developed in collaboration with project partners, veterinary clinicians and cat-trapping experts. This was reviewed throughout the project and set high standards for welfare and the management of risk to target cats and wildcats.

- The TNVR programme was launched across all six Priority Areas from the second winter of the project (2016-2017) after systematic camera surveys during 2015-2016 identified feral and hybrid cats to target for trapping. This programme was managed by a contractor in the Angus glens and by Project Officers (with volunteer support) in all other Priority Areas.

- Camera traps were usually placed ahead of live-trapping to identify target cats and acclimatise them to bait. Camera traps were often managed by volunteers with staff or contractors focused on live-trapping. Most effort was focussed on trapping wild-living cats (i.e. those living at greater distance from humans) because they likely present a greater immediate risk to wildcats. But feral or farm cat colonies were also specifically targeted in Strathbogie, where there was a number of substantial farm colonies living in close proximity to wildcat areas.

- In all the Priority Areas, neutering and vaccinating was conducted by qualified vets. Veterinary contractors were employed in the Morvern Priority Area and local veterinary practices were used in all the other Priority Areas. If no signs of ownership could be found, trapped cats were neutered, ear-tipped, and vaccinated against feline panleukopaenia virus, also known as feline parvovirus (FPLV), feline herpesvirus (FHV) and feline calcivirus (FCV), which are both primary causes of the disease syndrome commonly called ‘cat flu’. Cats were screened for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV – also known as ‘feline aids’) using SNAP tests. The project policy, following veterinary advice, was to euthanise any cat failing the SNAP test or exhibiting other signs of disease or injury that would adversely affect its welfare. When euthanasia was necessary it was carried out by a qualified vet, and not by the SWA project staff.

- Overall, we invested 3,652 trap nights in live-capture of cats. From the third winter (2017-2018) when wildcats were also targeted for genetic screening and GPS collar attachment, there was significant overlap in trapping for both TNVR cats and wildcats. Effort for capturing wildcats versus TNVR targets was not recorded separately.

- In total we captured 228 cats on over 262 occasions, including 205 that were feral cats and obvious hybrids (captured on at least 239 occasions). Another 12 feral and obvious hybrid cats from other sources were processed for TNVR. Bycatch was rare due to camera-led targeting, but included 13 pet cats, pine martens, foxes, badgers, hedgehogs and a buzzard. Trapping was avoided at locations visited regularly by badgers and pine martens. The use of valerian lure reduced incidence of trapping non-target species.

- Overall effort (trap nights per target cat) was 16 (14 per capture). Effort per target cat improved from 16 nights in the first trapping year to 12 nights in the second, before declining to 33-40 nights in the third and fourth years, when the focus was on capturing wildcats over TNVR. Of the feral and obvious hybrid cats caught, 99 (43%) were colony-living farm cats, most of which were captured in Strathbogie. Excluding farm cats, effort per target cat was 28 trap nights (a low of 19 in the second year and a high of 40 in the fourth year, when the genetic screening and collaring of wildcats was the main focus).

- Thirty-nine volunteers contributed an estimated 544 days directly to TNVR. Recruiting volunteers to conduct trapping for TNVR was substantially more difficult than recruiting for camera-trap surveys.

- Identification of owned (pet) cats was a significant issue for project staff. Considerable time and effort were required on the ground to deliver local awareness-raising campaigns and identify cats in the community. A ‘Mog Shots’ gallery was introduced on the project website and promoted on social media, to help identify pet cats ahead of trapping. But this was ultimately of limited benefit. A system that placed the onus of identification with the pet owners through the microchipping of their pets, rather than with TNVR workers, would have greatly increased both the efficiency and efficacy of TNVR.

- Permissions from landowners to conduct TNVR were not always forthcoming. Some landowners who allowed us to survey on their ground did not subsequently allow trapping for TNVR. This was primarily the case for estates that conducted predator control activity (including for feral domestic cats). Farmers with colonies were not always amenable to the idea of trapping and neutering their cats. However, their concerns (primarily ‘running out’ of cats for rodent control) could usually be addressed, particularly after discussion with other farmers who had directly observed the benefits.

- Only a small proportion of the feral cats and hybrids trapped were reported to the project via the website, with the majority detected through volunteer survey cameras or directly through the community engagement work of the Project Officers. Local knowledge proved more helpful in identifying farm cat colonies and feral cats around settlements.

- The project benefitted from informal collaboration between Project Officers and the staff and volunteers of animal welfare charities, including the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SSPCA), and Cats Protection (CP). For example, when assisting with large-scale TNVR and the holding and rehoming of stray cats and kittens.

- Based on the number of feral and hybrid cats estimated from camera surveys and discounting farm colonies, the 75% annual neutering rate needed for effective population control (Anderson et al. 2004) was not reached. On two occasions, approximately two-thirds of the population was neutered. Overall the 75% rate was difficult to attain with the resources available to the project and the often-conflicting demands of other field activities within the same time-limited season. TNVR targets were also difficult to measure because surveys concentrated on wild-living cats but farm cats were also neutered in some areas. Wild-living hybrids can behave similarly to wildcats and the difficulties we had identifying and trapping these was a key issue. But important lessons were learned, and with significantly more resources targeted at fewer locations, this high neutering rate may be achievable.

Acknowledgements

The SWA project was supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

It was also funded by the Scottish Government, NatureScot and the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. Support and resources for associated work was also provided by all the Steering Group members: Cairngorms National Park Authority, Forestry and Land Scotland, National Museums Scotland (NMS), Scottish Land & Estates, NatureScot, Scottish Wildlife Trust, The National Trust for Scotland, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, The Scottish Gamekeepers Association, The Scottish Government, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU). In addition, Jenny Bryce and Fiona Strachan helped develop the project while Eileen Stuart, Alan Bantick and Andrew Kitchener chaired the Steering Group.

Additional sponsors, funders and contributors to SWA work included Aigas Field Centre, Ailsa Black, British Association for Shooting and Conservation, Cairngorm Brewery Company, Chester Zoo, Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, John Muir Trust, Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, Lukas Ruiter Production, MyPetOnline, NFU Scotland, petDetect, RSPB, Scotland The Big Picture, Swift Ecology and The Highland Council.

We are also very grateful to the many academics, landowners and managers, farmers, foresters, keepers, captive collection managers, veterinary specialists and others who contributed valuable time and effort, members of the public who contributed funds and support, and in particular the many volunteers who got involved in the project.

Our profound thanks go to the volunteers, contractors and vets who helped us with the difficult job of trapping and neutering. We couldn’t individually name all the volunteer field assistants, but the work would have been impossible to carry out without their help. They included Laura Braunholtz, Jen Clark, Claire Hill, Ana Luisa Barros, Kirstin Mair, Rhonda Newsham, Ana Morales González, Fiona Pamplin, Héctor Ruiz, Lara Semple, Laura Sessions and James Walker. Many thanks to our contractors; Dr Roisin Campbell-Palmer, Kelsey Wilson, Kirstin Mair, Matt Wilson and Rhian Evans. Veterinary support came from Alice Bacon, Helen Wells, and staff at Aberlour Veterinary Centre; Dunnydeer Veterinary Group, Fraser & Fraser Vets, Seafield Veterinary Group, Strathbogie Veterinary Centre and Thrums Veterinary Group. Volunteers with Cats Protection and staff at the SSPCA were instrumental in helping us deal with some of the more challenging practical issues, such as neutering larger farm colonies and taking kittens into care. Matt and Rhian also kindly let us use their home as a base and clinic. Finally, thanks to the members of the public who informed us about feral cat issues in the Priority Areas.

1. Introduction

Hybridisation with domestic cats is a key threat facing wildcats in Scotland (Beaumont et al. 2001; Macdonald et al. 2004; Senn et al. 2019). One of the main tasks for SWA was to reduce the threat of continuing interbreeding with feral domestic and hybrid cats in Priority Areas. This report sets out the logic behind the approach adopted by SWA, the methods and results of the programme and recommendations for the future.

1.1 Why neuter?

There are two main approaches to the management of feral cat populations: lethal control (culling) and neutering. Neutering requires surgery to the reproductive organs of the cat and therefore the cat needs to be trapped unless it is socialised to humans, which, by definition, feral cats are not. It is standard practice to then return the cat to the point of capture because releasing a post-operative cat into a strange environment is considered poor welfare. Trap, Neuter, Return (TNR or TNVR where vaccination is included) is the standard term for this process. The scientific literature on TNR shows mixed results, with efficacy of the method dependent on the behaviour of the public in abandoning or neutering pet cats and the proportion of the feral cat population that was neutered (Bryce 2015).

TNR is reported to be successful in the long-term reduction of feral cat populations where neutering rates have been high (e.g. Neville and Remfy 1984; Gibson et al. 2002; Scott et al. 2002; Gorman and Levy 2004). Lethal control can also be an effective method of feral cat population control (e.g. Nogales et al. 2003; Winter 2004). However, there are situations where lethal control can have the opposite effect to that intended. For example, a study in Tasmania found that feral cat numbers increased as a result of a low-level culling programme, with controlled cats swiftly replaced by individuals from outside the control area (Lazenby et al. 2015). This perturbation of the cat population may bring with it an increased risk of disease transmission to wildcats when new feral cats move onto vacated territories, as has been proposed following the control of badgers (Meles meles) to eradicate Mycobacterium bovis (bovine tuberculosis), e.g. Tuyttens et al. 2001; Donnelly et al. 2006; Bielby et al. 2014. These new cats may not only carry new disease into the area, but scratches and bites that are inflicted as they establish new territories are likely a major route of infection of feline diseases such as FIV. Promoting lethal control of feral domestic cats and hybrids also carries additional risks for wildcats, and for pet domestic cats in wildcat Priority Areas, through unintentional killing. Due to these risks, in areas with wildcats, lethal control would also involve live-capture of cats to assess them prior to dispatch. This could reduce the overall efficiency of lethal control as a method, particularly compared with TNVR.

Scottish Wildcat Action focused conservation action in six Priority Areas (see the Monitoring and Surveys report for a review of the areas). These are discrete geographic areas where intensive TNVR could potentially achieve sufficiently high neutering rates to reduce the feral domestic and hybrid cat population. A long-term solution to the issues of feral domestic cats in the countryside must include public support to help identify the locations of feral cats, reduce abandonment of pet cats, and increase the neutering of pet cats (Loyd and DeVore, 2010). A survey of public attitudes to domestic cat management conducted ahead of the launch of the SWA project found a majority in support of encouraging pet cat neutering and other methods to reduce feral cats, such as discouraging feeding, and a majority (66%) also supported a TNR programme (Littlewood et al. 2014). Given these factors, and the risk that disease transmission may play in wildcat conservation (see the Disease Surveillance report), the management of feral and hybrid cats was conducted through a TNVR programme. We recognised that there may be no single solution to feral cat management and therefore did not oppose lethal control by estates within the Priority Areas where it was conducted without bringing risks to wildcats (see the Land Management report).

Modelling has indicated that annual neutering of 75% of the fertile feral cat population is needed for effective population control (Anderson et al. 2004), though lower levels of >50% may be sufficient provided there is no immigration (Schmidt et al. 2009). Neutering may result in lower immigration than lethal control and will require fewer cats treated because of this (Schmidt et al. 2009). Nevertheless, this is a challenging undertaking (Anderson et al. 2004) and the time-period to eradication of the feral population can exceed a decade (Nutter 2005).

SWA was a five-year project and, with the possible exception of Morvern, all of the project’s Priority Areas are likely to experience immigration of feral and hybrid cat populations from elsewhere. An intensive TNVR programme was therefore unlikely to lead to the eradication of the feral and hybrid populations within the five-year time-scale of the project. Thus, the expected outcome from such work would be to reduce, but not remove completely, hybridisation risk for any wildcats remaining in Priority Areas.

1.2 Initial aims

The need for feral and hybrid cat management through TNVR was highlighted under the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP):

2.4 Promote a co-ordinated approach to Trap-Neuter (vaccinate) and Release (TNR) of feral cats in priority areas.

- 2.4.1 Produce a protocol for an effective TNR programme. Operating guidance and contacts.

- 2.4.2 Promote reporting of feral cats to Cats Protection or local vets by farmers and crofters.

- 2.4.3 Support local volunteer groups to carry out TNR.

Alongside this, the project was asked by its key funder, the National Lottery Heritage Fund, to:

“train approximately 180 volunteers (30m per priority area) to assist with the trapping, neutering and re-release of feral cats”.

1.3 General approach adopted during the programme

From the start, wild-living hybrid and feral cats were identified as those most likely to breed with wildcats because they inhabit territories alongside or overlapping those of wildcats. Feral cats around farms and settlements may present a lesser risk unless wildcats visit farms and settlements or those feral cats range further afield in the breeding season searching for mates. In order to neuter wild-living cats, their locations need to be identified. The project therefore decided to use the camera-trap surveys (see the Monitoring and Surveys report) as a way of identifying initial targets for neutering.

TNVR can potentially be conducted at any time of the year. However, our core TNVR activity in Priority Areas was focused on the winter season. This temporal focus was due to both the higher efficiency of trapping wild-living cats during the colder months, when there is a shortage of natural food and they are more likely to visit baited traps, and to avoid the risks of trapping in wildcat areas during the later phase of the wildcat breeding season, when females may be pregnant or have dependent young (March – August). The timing of field activities was necessarily interconnected, with camera-trap surveys also being conducted over winter, and the results of the surveys being used to subsequently target trapping effort. TNVR of farm colonies, or feral domestic cats in urban areas, could be conducted out-with the winter season where there was no risk to wildcats, particularly where cats were regularly fed by farmers or ‘carers’, because this makes them far easier to catch. This activity could be particularly time-consuming for Project Officers, and so had to be balanced against conflicting priorities. It was usually undertaken as a result of reports of feral cats from the community, rather than active attempts by project staff to locate neutering targets over the summer. Care also had to be taken when trapping domestic cats during their respective breeding season (spring through to autumn), to avoid the same potential welfare issues of pregnant females or dependent young.

Recruiting volunteers to conduct camera-trap surveys was vital to the project. The task is relatively straightforward (though not necessarily easy) and the incentive for the volunteers is that they could possibly see a wildcat on a survey camera. Some of these volunteers would also get involved in the more complex task of live-capture for TNVR. The project additionally advertised on its website for TNVR volunteers and made use of a small number of seasonal full-time ‘residential’ volunteers to assist in both surveying and live-capture and the management of other volunteers involved in these. These seasonal volunteers proved hugely important to the project. All volunteers were given training ahead of their involvement in the TNVR programme.

The TNVR programme began in the second year of the project (2016-2017) and was focused entirely on the capture of cats that were clearly hybridised or feral. From the third year, trapping aims also included the capture of wildcats for genetic screening and GPS collar deployment (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). However, TNVR and wildcat trapping efforts are not independent, since wildcat spatial distribution overlapped with all other wild-living cats, and some individuals could not be confidently assigned to ‘wildcat’ or ‘hybrid’ based on camera-trap photos alone, and a diagnosis (and subsequent action) was decided after sedation. Therefore, throughout this report, figures on trapping effort and capture rates related to all types of cat unless explicitly stated.

2. Methods

2.1 Timing

Preparatory camera trap surveys and pre-baiting with traps in-situ commenced in autumn 2016. Traps were secured (locked open with padlocks and the back door removed) to prevent tampering or accidental closure, and to allow time for the traps to ‘bed-in’ to the environment. No active trapping took place until the wildcat breeding season was over and any wildcat kittens were likely to be semi-independent and not at risk of capture. Camera-trapping of all trap sites helped to ensure there was no risk to very young wildcats. The active TNVR season ran from October to March with local variation in each Priority Area (for example, depending on cat sightings, volunteer availability, weather and access permissions). The winter focus was chosen to coincide with camera trap surveys providing current sightings data, and because the cold weather and lower availability of natural prey make cats more likely to visit bait stations. In addition, male wildcats range more widely during winter looking for potential mates and are therefore more trappable over a larger area. In most areas, trapping temporarily halted for two weeks over Christmas and New Year.

All trapping ceased by mid-March at the latest, as per TNVR protocols designed to reduce the risks of trapping either heavily pregnant cats (or females with dependent young) or other wildlife (particularly pregnant pine martens). Some PAs and sensitive sites ceased trapping at the beginning of March, or earlier if at-risk animals were detected by camera traps. Some opportunistic TNVR activity continued in Priority Areas over the spring and summer in limited cases, usually where individual feral cats or colonies were reported directly to Project Officers in areas where they were easy to catch (farms or back gardens) and presented no risk to wildcats. In some cases, Project Officers focused TNVR effort in concentrated bursts of one to two weeks of intensive activity, with a break before the next bout. This approach allowed staff time to recover (particularly from lack of sleep) and also allowed for coordinated timing with the local veterinary practices, who could not always conduct neutering at short notice.

Two photographs showing cage traps. The left image shows a trap set against a wall and covered with a waterproof sheet and vegetation. The right shows a feral cat caught in a trap.

2.2 Process

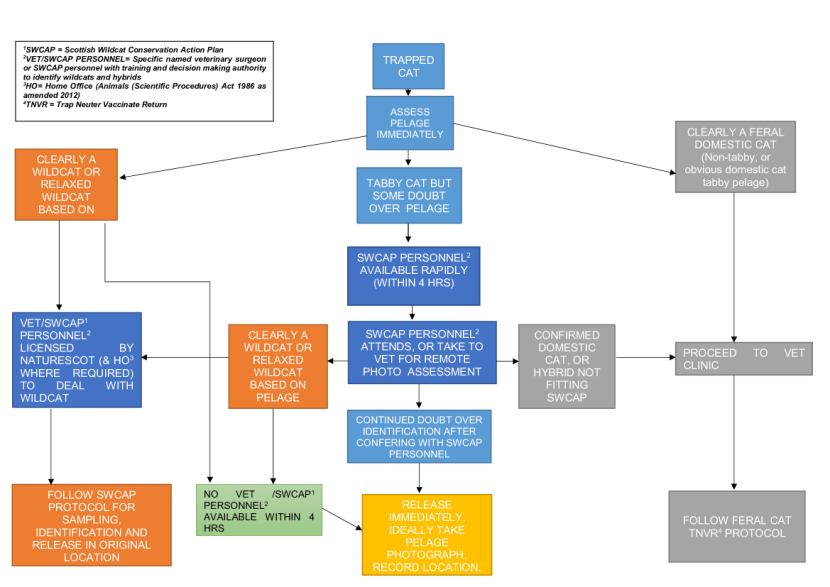

A detailed TNVR protocol (see Annex 1) with associated guidance was developed in collaboration with project partners, veterinary clinicians and cat-trapping experts. This protocol was continually reviewed throughout the project and aimed to implement best practice and set high standards for welfare and the management of risk to target cats and wildcats. A detailed protocol for the targeted trapping of wildcats is provided in the Monitoring and Surveys report and, unless otherwise stated, the methods set out below all related to TNVR. All TNVR was undertaken using techniques outlined in the TNVR protocol and every trap site went through the following stages:

2.2.1 Site Selection

Sites were selected based on a number of factors. The first factor was the known or suspected presence of a feral or hybrid cat based on camera trapping or public reports. Secondly, sites were selected based on ease of access and thirdly, welfare considerations for the individual. So, for example, if camera trapping found a cat visiting several locations, the preferred location to trap at would have the best vehicular access and provide better protection from the weather. A camera trap was placed for a minimum of one week beforehand to research each site. This helped ensure only target feral cats were trapped and also minimised conflicts with the presence of non-targets such as wildcats or pet cats.

2.2.2 Pre-baiting

Cage traps were placed in situ but inactive (locked open) with bait provided to attract cats. The pre-baiting period varied widely, depending on how often individual cats would visit the site and how motivated they were to reliably enter the trap and take food (or visit valerian lure). Cameras continued in operation to check for any non-target cats or other species that might affect trapping effectiveness, such as the presence of badgers.

2.2.3 Live capture

Traps (Figure 1) were generally run ‘live’ overnight (c.12 hours) for four to five nights per week, according to staff/volunteer availability and vet opening hours. Some traps were live for the full 24 hours over those days. Every trap was checked at least every 12 hours, or at least every eight hours if a potential wildcat was known to visit the trap location. Alternatively, a remote monitoring system was used (see 2.4), mainly where wildcats were the main target. With remote monitoring, during the first season of operation physical checks were conducted every 24 hours while the effectiveness of these systems was assessed. In later seasons, this rule was relaxed as the system proved reliable, with no captures going undetected by the monitoring devices.

Two photographs from the TNR programme. The left shows two volunteers standing in a farmyard holding cage traps in which cats have been captured. The right shows 12 transport crates holding cats just captured at a farm colony.

Where local veterinary practices were being used to conduct the neutering operations (most cases), the vets had to be notified of the trapping work in advance. All trap sites were visited first thing in the morning (6-8am) and any captured cats were immediately evaluated for potential ownership (did they have a collar or a microchip, were they showing behaviours typical of feral cats etc). In most cases, the feral status of the target cat had been established beforehand, through communication with local people. Cats that were likely to be owned were released; cats that appeared to be stray (previously owned but now in poor health or condition) and obvious feral cats were taken to the vets. Where possible, the hybrid status of trapped cats was also evaluated in the trap (quickly to cause minimal stress), and the visible pelage often gave a clear indication that cats should be neutered (i.e. an obvious dorsal line extending down the tail). Cats with an unconfirmed or borderline pelage score were taken to the vets for assessment under sedation. Cats were transferred in situ from the trap to a ‘crushable’ transport cage (also known as a crush cage), which allowed the vets to sedate them without the need for physical contact.

During TNVR, the vets were called in advance to notify them of how many cats were being brought in for surgery. Generally vets asked that cats were delivered to veterinary practices as soon as they opened (between 8am and 8.30am). The vets would phone the Project Officer later in the day to notify them of a collection time, or to discuss potential problems (such as hybrid status, welfare issues, microchips or positive SNAP test results). Vets often sent photos of the sedated hybrid to the Project Officer for remote pelage scoring.

Live capture at farm cat colonies (Figure 2) followed a different procedure. Additional coordination was needed with the veterinary practice to ensure they had the capacity to process a large number of cats in one day and the work involved a larger team of trappers, drawn from staff, volunteers and other welfare organisations. Depending on the level of socialisation to humans, farm cats were either trapped overnight, or over the course of a few hours during the day. The most socialised could be approached closely enough to capture by hand. For large colonies, only a representative sample of the colony had blood samples taken for subsequent disease and genetic screening (see the Disease and Monitoring Surveys reports).

2.2.4 Release and post-capture follow-up

After surgery, healthy cats were collected and released by project staff, or occasionally by volunteers. Male cats were released in the afternoon after surgery. Female cats were almost always kept in overnight, either by the vets, or where they did not have capacity (e.g. in Strathspey) the female cats were collected and looked after by volunteers until their release in the morning. Female cats were usually kept in the crush cage with an additional cage attached to the front containing food and water. All cats were released at the same location where they were caught within 36 hours of capture, with the vast majority within 24 hours. Most cats were subject to post-release monitoring with camera-traps (Figure 3), and staff and volunteers continued to provide food for a limited time after trapping where possible, particularly in very cold weather. This was generally easy to do because cameras and bait remained in place to monitor or target other cats in the same location.

Two photos taken on camera traps. The first shows a cat sitting in an open trap with food outside the trap, taken during the ‘pre-bait’ stage of trapping. The second, inset, shows a previously neutered black feral cat with its left ear tip missing.

2.3 Staffing

Staffing of TNVR (site research, pre-baiting and active trapping, transfer to vets as well as aftercare of cats etc) varied according to Priority Area. In some areas, the Project Officer did the majority of the work due to the availability of volunteer help (see 4.2.4) or site access restrictions. In other areas, much more of this was delegated to local volunteers. In Angus, some volunteers assisted with the initial trap setup on pre-bait, but all later stages were conducted by contractors. All veterinary procedures (sedation, neutering etc) were carried out by licenced veterinary clinicians.

Two photos showing the work of the project during TNVR. The left shows a SWA staff member walking along a track carrying a trapped cat in a transport cage. The right shows a cat lying sedated on a table as a vet, assisted by volunteers, operates.

2.4 Equipment used

Automatic trap models used were Trapman® small and large cat traps; MDC Eezicatch® traps with mesh floors; MDC Eezicatch(R) cat traps; and Albion fox traps modified with 25m gauge mesh (the latter only for wildcat trapping). Manual cage traps (i.e. where the trapper closes the door manually and in close proximity, after the cat has entered) were successfully used in rare instances, usually in a garden where feral cats were used to being fed and would enter the trap immediately for food, allowing selective trapping of the feral cat versus any pet cats. Each trap was accompanied by a camera trap (mostly Spypoint trail cameras but also Cuddeback models, see the Monitoring and Surveys report) set up opposite the trap entrance to monitor all animals visiting the site, before and during the live trapping process. In the small number of cases where remote monitoring systems were used, these were usually MinkPolice trap alarm units, but SIM-enabled Acorn trail cameras were also used (Campbell and Griffith 2015). All traps were baited with food (quail, rabbit, tinned fish and wet or dry domestic cat food) and/or scents (salmon oil, catnip and valerian root). Cat urine, sourced from vets, was also found to be effective during initial trials but because of concerns around disease and risks to volunteers, this was not adopted as a lure.

2.5 Targets for TNVR

Traps were deployed where there was evidence of feral cat presence, either from camera-trap surveys or public sightings. In most areas, those individuals found closest to known wildcat territories or habitats were targeted first. Staff also responded to reports of feral cat colonies on farms. During the first year of TNVR (project year two), feral cats and obvious hybrids were targeted first rather than borderline hybrids; this precautionary approach was taken while volunteers, vets and staff gained more experience in pelage scoring. In the second year of TNVR, any individual scoring <17 on pelage score (Kitchener et al. 2005) was targeted for TNVR and some wildcats were also targeted for genetic screening (see the Morphology / Monitoring and Surveys reports) and GPS collar attachment (see the Ecology Report). During the fourth and fifth years of the project, more wildcats were targeted and staff more often adopted a trap-and-assess approach to TNVR decision-making as cats with pelage scores close to the 17 threshold were targeted. This change in strategy followed a review of data from camera-trap surveys that showed wildcats made up only a very small proportion of the wild-living cat population (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). From this, it was agreed with veterinary partners that the risk of not neutering a hybrid due to over-caution was greater than the risk of accidentally neutering a wildcat. During the fifth year of the project, TNVR was not the primary focus of work by project staff. Whenever a wildcat was known to visit a trapping location, wildcat trapping protocols were followed (see Monitoring and Surveys report).

2.6 Access permissions

Every TNVR site had landowner access permission. Major landowners giving permission included Forestry and Land Scotland and the Crown Estate in Strathavon. Not all estates managers who gave access for general wildcat survey work also gave permission for TNVR as some preferred to continue their own lethal control methods.

2.7 Training of local volunteers

Each Project Officer undertook training for their TNVR volunteers, utilising materials developed by Emma Rawling (TNVR Project Lead). Some chose to run in-depth events, others to train individual volunteers on a case by case basis. Every volunteer participating in TNVR was asked to sign a confirmation of method and training sheet to ensure protocols were followed. Generally, local volunteers required considerable supervision and continual input from POs during all stages of the TNVR process.

2.8 Contractors

Contractors were recruited to deliver TNVR in the Angus Glens PA due to the impracticalities of staff covering two Priority Areas at the same time. Due to staff shortages in year five, the contractor was also used for wildcat trapping in Strathbogie.

2.9 Pop-up TNVR clinics

Due to a lack of veterinary access in the Morven Priority Area (the nearest being over an hour’s travel time in either Fort William or on the island of Mull), the decision was taken to trial a ‘pop-up’ TNVR clinic in Morven (Figure 4). An intensive period of TNVR was undertaken at the end of the camera-trap survey period, using the sightings data to target individual cats and potential trapping locations. A vet was contracted to provide services for the period alongside a volunteer Veterinary Nurse. Equipment was either provided by the veterinary practice of the contractor, purchased by SWA or borrowed from other practices. An intensive four days of trapping, aided by three project staff members, was undertaken with a temporary treatment clinic set up in our local contractors’ home. This was a highly successful approach, treating eight cats in four days in the first trapping season and representing a good return for number of days of effort. During the second season, poor weather hampered trapping success and staff and vets used the spare capacity left from fewer captures to undertake further community engagement and neutering work on pet cats.

2.10 Vets

In almost all cases, cats were transferred to local veterinary practices for treatment as previously arranged and agreed with the local Project Officer. Veterinary practices differed widely in their capacity to assist with TNVR. Some of the smaller practices could only provide limited help, particularly when trapping clashed with other seasonally intensive activities such as lambing. Six different practices participated regularly, although at least three more were willing to receive cats from the project. Each participating practice was given an SWA introduction pack, a TNVR protocol and a sample kit for each cat. Each cat was delivered with an SWA admission form to ensure consistency of approach and accurate record keeping. Some costs were kept down by SWA providing SNAP tests from our own supplies. Unfortunately, an agreement for a vaccine manufacturer to donate vaccines to the project was cancelled and therefore vaccines were either supplied by the vet or purchased through the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies.

2.11 Data collection and analysis

2.11.1 Number of individuals captured

Cat trapping was recorded in two ways. Firstly, project staff and contactors reported capture totals to the Steering Group quarterly or at the end of the winter season. Secondly, each cat that was processed in any way (i.e. taken to a vet or non-invasively sampled) instead of being released immediately (pet cats, non-target recaptured cats) had a procedure form completed (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). There were slight variations between these figures. For example, stray cats brought in by the public during TNVR would be classed as TNVR in the procedure forms but were excluded from trapping counts because they were not captured by project staff or volunteers. This resulted in the figures from procedure forms slightly exceeding those recorded by project staff. A project year ran from April to March inclusive. This was because the peak of the trapping season ended in March and the period matched the project reporting periods.

2.11.2 Trapping effort

Project staff estimated trapping effort based on the number of traps set to capture and the number of nights each was set. From years three to five, wildcats were also targeted for capture for genetic screening and GPS collar attachment (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). Since wildcats and non-wildcats often visited the same traps, the aims of trapping overlapped. Moreover, for some cats, deciding whether to neuter versus GPS collar (non-wildcat versus wildcat) was only made once the cat had been sedated. It was therefore not possible to record trapping for TNVR separately from trapping for wildcat capture. While pet cats and recaptures were usually excluded from trapping records, for the purposes of assessing trapping effort, individuals that were recaptured intentionally, such as wildcats that required GPS collar replacement or removal, were included. This is because the targeted recaptures required trapping effort. Because trapping colony cats requires much less effort per individual than capturing wild-living cats, trapping effort was also calculated excluding colony-living individuals. The total number of trap nights were not adjusted because trapping effort for colonies was not recorded separately and it was assumed that the effort involved for colonies was only a small proportion of the total (see Results, below). The only exception to this was for Morvern, where the colonies were very small and capture still required considerable effort. The colony status of cats was not recorded in quarterly and annual reports and so has been calculated from procedure form records.

2.11.3 Estimating proportion of cats captured

To estimate the proportion of the non-wildcat wild-living population processed through the TNVR programme, population figures from the two standardised surveys (or an average where two standardised surveys were conducted). See the Monitoring and Surveys report for details on population figures. Where spatially explicit capture recapture (SECR) population estimates were available, these were used minus the number of wildcats detected during the survey. Otherwise, the number of cats detected (known as the ‘minimum number alive’) less the number of wildcats was used.

2.11.4 Additional statistics

Once trapped, a cat had four possible outcomes. 1. It was a wildcat and would be released after sampling (and collaring for some); 2. It was a non-wildcat and failed a SNAP test, at which point it would be euthanised on welfare grounds; 3. It was a non-wildcat and passed the SNAP test, at which point it would be neutered, vaccinated and released; and 4. It passed the SNAP test and it was a kitten (<12 weeks in age) and therefore could be rehomed. These cat outcomes were recorded by project staff during years two and three alongside the number of volunteers assisting with TNVR.

3. Results

3.1 Number of captures and outcomes

A total of 240 procedures were recorded (Table 1) and 262 cats were recorded as captured. This included 13 pet cats over all years and 21 non-target recaptures in years three to five. Excluding these, 228 cats were captured, of which 205 were feral domestic or hybrid captures (Table 2). Pet cats and non-target recaptures are excluded from the main count and included separately. A year ran from April to March inclusive and no trapping was conducting in year one. For TN/cat figures, total is the total TN/total cats, while mean is average across years. Pets and recaptures are not included in the trap effort calculations (Table 2) and 23 wildcat capture events, though 25 procedures were recorded, see Table 1, because two wildcats were later reassessed as hybrid from pelage. A total of 215 non-wildcats were processed (Table 1), with the disparity in numbers between this and the 205 recorded captures partly arising from cats not captured by project staff and volunteers (including all cats from outside the Priority Area boundaries). Not all cats processed for TNVR were recorded as cat procedures, however. For example, a colony of 26 cats trapped had only 22 procedure records. It is not clear why this was the case, but indicates that the figures presented here are slight underestimates. Only cats initially assessed as wildcat were targeted for recapture, either for collaring or because they were later reassessed as hybrids and were targeted for TNVR. Probably, many more non-target recaptures were unrecorded and therefore while at least 215 individual feral domestic and hybrid cats, including 12 not trapped by the project, were processed (neutered and vaccinated, rehomed or euthanised), it is highly likely there were more than 262 capture events. Over years two to three, when the majority of feral domestic and hybrid cats were captured, 12 (7%) failed SNAP tests and 17 (10%) were kittens young enough to rehome (Table 3). SNAP test fails were more commonly associated with older male cats living in colonies. Colony-living cats made up half of the feral domestic and hybrid cats captured, of which most (79 of 115, Table 1) were from Strathbogie. About one quarter of these colony-living individuals (26), all from other Priority Areas, were classed as from small colonies (<five cats).

3.2 Trapping effort

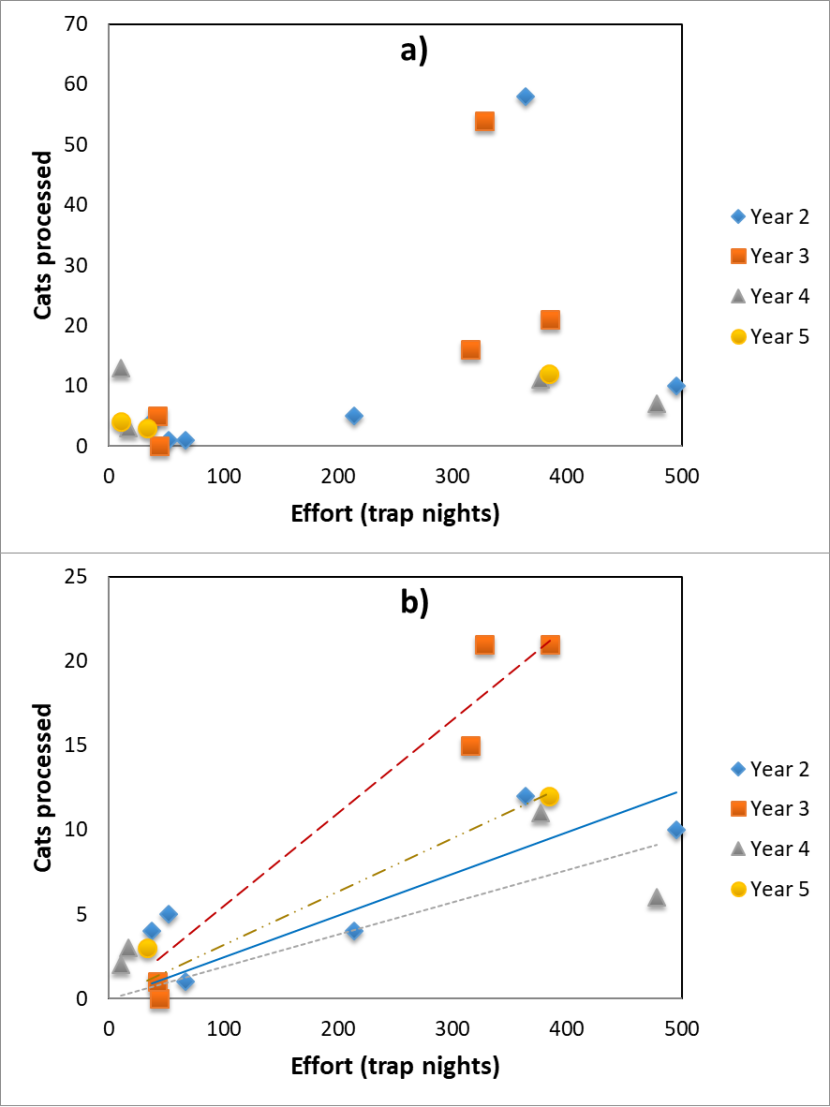

The effect of trapping effort on the total number of cats captured was highly variable (Figure 5a) and effort ranged from 12 to 26 trap-nights per cat (overall 16 trap-nights per cat, Table 2). This was largely due to the capturing of cats living in colonies, particularly in Strathbogie. One example of the trapping of cat colonies is illustrative: a large farm colony was unidentified in Strathbogie. Following extensive groundwork by project staff and with the assistance of an SSPCA inspector, all 26 cats in the colony were trapped in one afternoon. Even smaller colonies were relatively easy in terms of trap-night effort, though considerable work may have been needed to set up the trapping. Discounting colony-living cats, the relationship between trapping effort and cat captures is clearer (Figure 5b). The first year of trapping (year two) involved 34 trap-nights per cat (Table 2). This was reduced to 19 trap-nights in year three as staff and volunteers gained experience. In years four and five, the effort per cat increased again to 40 and 33 trap-nights when wildcats were targeted.

|

Cat type |

Sch-eme |

Pheno-type |

Priority area |

Year 2, 16-17 |

Year 3, 17-18 |

Year 4, 19-20 |

Year 5, 19-20 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

D |

MV |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

D |

SB |

46 |

33 |

0 |

0 |

79 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

D |

SP |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

D |

SS |

0 |

0 |

10 |

1 |

11 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

D |

xPA |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

D |

Sub-total |

59 |

34 |

10 |

1 |

104 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

H |

SP |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

H |

SS |

0 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

H |

xPA |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

NW-C |

TNVR |

H |

Sub-total |

3 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

11 |

|

NW-C |

- |

Total colony |

- |

62 |

38 |

11 |

4 |

115 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

D |

TNVR |

8 |

18 |

5 |

0 |

31 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

D |

AG |

2 |

6 |

3 |

0 |

11 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

D |

SA |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

D |

SB |

1 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

10 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

D |

SP |

2 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

D |

SS |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

NW-L |

WcT |

D |

WcT |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

|

NW-L |

WcT |

D |

SB |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

|

NW-L |

- |

D |

Sub-total |

8 |

18 |

6 |

4 |

36 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

H |

TNVR |

15 |

35 |

4 |

0 |

54 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

H |

AG |

7 |

13 |

2 |

0 |

22 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

H |

SB |

7 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

H |

SP |

0 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

H |

SS |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

|

NW-L |

TNVR |

H |

xPA |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

NW-L |

WcT |

H |

WcT |

2 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

10 |

|

NW-L |

WcT |

H |

SB |

0 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

|

NW-L |

WcT |

H |

SS |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

NW-L |

WcT |

H |

Sub-total |

17 |

35 |

6 |

6 |

64 |

|

NW-L |

- |

Total lone |

- |

25 |

53 |

12 |

10 |

100 |

|

NW |

Total |

D + H |

- |

87 |

91 |

23 |

14 |

215 |

|

Wc |

TNVR |

W |

AG |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Wc |

TNVR |

W |

SB |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Wc |

TNVR |

W |

SP |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Wc |

TNVR |

W |

Total |

1 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Wc |

WcT |

W |

AG |

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

Wc |

WcT |

W |

MV |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

Wc |

WcT |

W |

SB |

0 |

0 |

6 |

4 |

10 |

|

Wc |

WcT |

W |

SS |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Wc |

WcT |

W |

Total |

1 |

0 |

11 |

7 |

19 |

|

Wc |

Total |

W |

- |

2 |

5 |

11 |

7 |

25 |

|

Grand total |

- |

- |

- |

89 |

96 |

34 |

21 |

240 |

3.3 Volunteers

A total of 39 volunteers (Table 3) assisted in trapping directly, alongside the many more who assisted by setting and maintaining survey camera-traps to locate targets (see the Monitoring and Surveys report). These included 10 seasonal full-time volunteers who assisted in many aspects of the work including coordination of survey volunteers, maintaining survey cameras alongside the trapping tasks for both TNVR and wildcat trapping such as setting and checking traps and taking feral domestic and hybrid cats to the vet. The remaining volunteers assisted by monitoring cage traps but more rarely were able to transfer trapped cats from cages to transfer baskets and take them to the vet. Through direct involvement for TNVR or time spent as full-time volunteers assisting with aspects of the project including TNVR, volunteers contributed the equivalent of 544 days. In addition, an estimated 2,100 days were invested by other volunteers in setting and maintaining camera-traps to allow detection and monitoring of cats.

|

Year |

Trap nights (TN) |

Total cats |

Total exc. colonies |

Wild-cats |

TN/cat |

TN/cat exc. colonies |

Bycatch (Pets + re-captures) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2 |

1229 |

79 |

36 |

2 |

15.6 |

34.1 |

7+0 |

|

3 |

1114 |

96 |

58 |

5 |

11.6 |

19.2 |

4+8 |

|

4 |

882 |

34 |

22 |

9 |

25.9 |

40.1 |

0+8 |

|

5 |

427 |

19* |

13 |

7 |

22.5 |

32.8 |

2+5 |

|

Total |

3652 |

228 |

129 |

23 |

16.0 |

28.3 |

34 |

|

Mean |

913 |

57 |

32 |

5.8 |

18.9 |

31.6 |

8.5 |

*including two cats previously trapped as wildcats, later reassessed as hybrid and recaptured for TNVR.

Two plots of trapping effort against number of cats processed, colour coded by year. In both there is a general pattern within years of more effort leading to more cats captured. In the top plot there is a lot of variation however, which is partly explained by some cats coming from colonies. Removing these in the lower plot shows a much clearer pattern between effort and numbers of cats.

|

Priority Area |

Feral / hybrids |

Wildcat |

Cats TNVR |

SNAP test fails |

Kittens |

Volunteers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Angus Glens |

22 |

2 |

22 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Morvern |

10 |

0 |

9 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

|

Strathavon |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

|

Strathbogie |

116 |

4 |

96 |

6 |

12 |

6 |

|

Strathpeffer |

24 |

1 |

19 |

2 |

3 |

11 |

|

Strathspey |

10 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

Total |

184 |

7 |

152 |

12 |

17 |

39 |

3.4 Proportion of cats captured

Using the first full camera-trap surveys in each area as a baseline and excluding cats processed from colonies (except Morvern), in any one year the percentage of feral domestic and hybrid cats trapped for neutering did not exceed 75%, while the 50% threshold was met on two occasions (Table 4). Including colony-living cats, in Strathbogie in years two and three, more cats were processed than estimated to be living in the area, but this was because the camera surveys would not have included most colony-living cats.

Table 4. Number (N) of feral domestic and hybrid cats processed, and as a percentage (%) of their population size estimated from camera surveys, in each year (Y). Cat processing figures exclude farm or colony-living cats, except in Morvern where colonies were all very small and a proportion was detected during the survey.

|

Priority Area |

Population size |

N Y 2 |

N Y 3 |

N Y 4 |

N Y 5 |

% Y 2 |

% Y 3 |

% Y 4 |

% Y 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Angus Glens |

38 |

9 |

18 |

4 |

0 |

24% |

47% |

11% |

0% |

|

Morvern |

9 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

. |

67% |

0% |

0% |

. |

|

Strathavon |

12 |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

8% |

. |

. |

. |

|

Strathbogie |

29 |

11 |

19 |

5 |

6 |

38% |

66% |

17% |

21% |

|

Strathpeffer |

52 |

4 |

14 |

. |

. |

8% |

27% |

. |

. |

|

Strathspey |

22 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

. |

23% |

5% |

9% |

. |

3.5 Change in cat recruitment

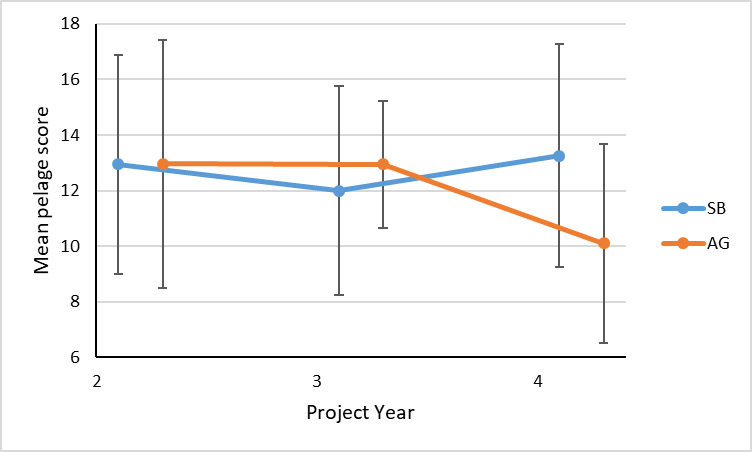

Two of the Priority Areas, Angus Glens and Strathbogie, had consistently higher processing rates for cats. Based on full surveys in years one and three and informal surveys for the purpose of TNVR in years two and four, the mean pelage score of recruits into the cat population (cats not detected in prior surveys) did not change from years two-four (Figure 6).

A plot showing the mean pelage score (with error bars for SD) in Angus Glens and Strathbogie, which shows little change in mean pelage score over the years. Note that the locations surveyed in the Angus Glens changed more between years than in Strathbogie and so there change in mean pelage score could be due to different individuals being captured on camera.

4. Discussion

4.1 Trapping success and impacts

4.1.1 Capture rates

Trapping success peaked in year three of the project, where the mean number of trap nights per cat was 11.6 including all cats and 19.2 for wild-living cats (i.e. excluding farm cats). This latter figure is equivalent to 0.052 cats per trap night. This is a higher rate than reported by either Campbell (2015) of 0.035 cats per trap night for wild-living cats (including hybrids) in Scotland, and three times that reported by Potočnik et al. (2002) of 0.017 cats per trap night reported for wildcats in Europe. Similarly low values have been reported for wild-living feral cats in New Zealand, e.g. 0.007 for cage-trapped feral cats from an eradication programme on Little Barrier Island, and 0.010 in 1996 with cage-trapping (alongside spotlighting) on Macquaire Island (Parkes et al. 2014). The relatively high success rates for the project may partly reflect that while the cats targeted were largely living wild (feral), some will have been associated with settlements, making trapping easier. For example, an Australian eradication programme found a success rate of 0.094 cats per trap night for cats that scavenge around rubbish tips, versus an overall success rate of 0.008 for both wild-living and scavenging cats (Short et al. 2002). The high success rate will also reflect the highly intelligence-led targeting of trapping effort, using camera-traps and local knowledge to guide trap placement and to assess pre-baiting success. The tens of thousands of camera-trap nights effort along with the various other tasks that underpinned live-trapping are not factored into this measure of trapping success, though camera-trapping requires an order of magnitude less input by staff and volunteers per unit effort than live-trapping. When the project focused on trapping wildcats, annual success dropped to between 32.8 and 40.1 trap-nights per cat (0.030-0.025 cats per trap-night). Compared with the Potočnik et al. (2002) study, these figures are still impressive and overall, the trapping success figures illustrate the effectiveness of the camera-first, trap-second approach adopted by SWA. A notable change to the project’s approach that helped improve trapping success between years two and three in the Angus Glens was a move to more trap-and-assess decisions instead of avoiding targeting cats that were borderline on pelage score. This allowed more choice of location and meant that decisions to open a trap from pre-bait were made more quickly. In most instances where a cat was scored borderline on pelage from camera trap images, assessment while sedated indicated it scored as a hybrid. This shift in approach also occurred elsewhere to a lesser extent, but the main reason trapping success improved in year three was the increased experience of staff and volunteers and better local knowledge.

4.1.2 Proportion of population captured

Despite the relatively high success rate, the project did not succeed in capturing 75% of the wild-living population in any one year, though two-thirds were caught on two occasions. Trapping such a large proportion of the population was undoubtedly made more difficult by the targeting of wild-living cats, though ensuring such cats are neutered will be essential to reduce the risk of further hybridisation. Cats living in farm colonies may also present a risk for hybridisation (indeed, many of those were found to be hybrids based on genetic assessments, see the Monitoring and Surveys report). However, the numbers of those in each Priority Area were not known and therefore it is impossible to establish whether the high number of these processed during the TNVR programme (about as many cats again as were captured in the wild) represent 75% of the unneutered farm cat population.

That 66% of wild-living cats in Strathbogie were caught in year three was largely due to the resources applied to TNVR in that area: The SWA Project Officers were normally responsible for two Priority Areas, with the Project Officer for Strathbogie also covering Strathavon. The decision to withdraw from Strathavon allowed greater investment of staff and, consequently, volunteer time on TNVR in Strathbogie. Had more resources been similarly concentrated on the other Priority Areas, a higher proportion of the wild-living population may have been caught in those areas in some years too. Note however that the estimated numbers of wild-living feral and hybrid cats were greater in the Angus Glens, Strathpeffer and Strathspey areas than in Strathbogie. The staff resources required to achieve the 75% threshold are clearly significant and for areas with substantial wild-living feral and hybrid cat populations, more than one staff member per Priority Area would be required. Other issues experienced around TNVR are discussed below.

4.1.3 Impacts on the population

No change was observed in the quality (based on pelage) of newly recruited cats into the population for the two Priority Areas were the most effort was put in to trapping and monitoring. This does not indicate that the TNVR programme did not achieve some impact on the population but within the timescales of the project, ensuring population change is challenging and accurately measuring the long-term impact on the wild-living cat population was not possible. Note that cats classed as domestic or hybrid based on pelage often scored lower on genetic tests (see the Monitoring and Surveys report) compared with individuals scoring as wildcat, though there was overlap in genetic scores between the cat pelage groups.

4.2 Issues around finding and trapping feral cats

4.2.1 Working with other organisations

4.2.1.1 Coordination of work

Cats Protection (CP) also undertook neutering of feral cats in most of the Priority Areas. While the project developed good working relationships with CP volunteers in some areas, in two Priority Areas, there was no such relationship. This may have been due to false reports that the project was conducting lethal control in the Priority Areas. This led to duplication of effort and wasted time for vets, staff and volunteers. In at least three cases, feral cats were targeted by our teams that, when presented at vets, turned out to be already neutered by others. In those cases, the cats had not been marked using the standard ear tipping method to indicate the cat as treated, so staff were unaware of their status. However, in areas where SWA had working relationships with CP volunteers and SSPCA staff, the project benefited by being able to concentrate activity at locations where these organisations rarely worked, for example on wild-living cats not associated with human areas (e.g. settlements or waste ground). Furthermore, on occasion, the organisations were able to team up to tackle larger tasks such as some farm colony neutering in Strathbogie.

4.2.1.2 Dealing with kittens

Kittens can present a problem as SWA is not a welfare organisation (unlike CP or the SSPCA) and therefore did not have facilities to hold kittens. Kittens trapped before the age of 8-12 weeks require holding until they are old enough to neuter. This required coordination with CP, SSPCA and others who had facilities to hold kittens. Without the help of these organisations and individuals, targeting mothers with kittens would not have been possible and the unexpected capture of kittens would have created a problem for staff. Future neutering programmes need to ensure they have access to facilities to hold kittens either through relationships with other organisations or by maintaining the facilities within the programme.

4.2.2 Identifying pet cats

A large amount of Project Officer time was spent in preparatory work trying to ensure pet cats were not accidentally targeted or caught during TNVR. This was communicated through posters, leaflet drops through letterboxes (for at least a one-mile radius of trapping sites) and website and social media publicity. For example, a ‘Mog Shots’ gallery was trialled on the project website where camera-trap images of suspected pet cats were posted. Web and social media posts produced few results and most information on pets was gathered locally. In some areas, such as Strathpeffer, this task was especially time-consuming and represented a large proportion of staff time on TNVR. There, staff adopted an innovative approach using a Community Cat Board (Figure 7). Overall this work constituted vastly more effort than any other organisation conducting TNVR typically invests and was undertaken largely because the project pro-actively found cats, whereas other organisations normally reactively trap cats following reports from the public. If all pet cats were identifiable through microchipping, this work would have been unnecessary. Compulsory microchipping of pet cats would greatly benefit future feral cat management.

A photo pf a display board set up in a community centre. On it are information about the project, including maps and guidance on identifying wildcats. Also on the display are images of local cats seen om camera, asking locals if they recognise any of the cats as pets.

4.2.3 Lack of feral sightings from the public

Most TNVR was undertaken on target feral cats and hybrids identified from camera surveys. The number of such cats reported by the public was very low (see the Monitoring and Surveys report) and needs to be encouraged in the future. Low reporting could have been caused by some of the public believing the false reports about the project’s use of lethal control, the difficulty people have in identifying a feral cat from pets, and that reporting feral cats instead of wildcats or hybrid cats is not as interesting to the public.

4.2.4 Working with volunteers

Many local volunteers helped with camera traps and pre-baiting cage traps. However, only a small proportion of those were also able to help in the process of capture and transport to the vet. Reasons for this are varied and include the constraints from other commitments (e.g. employment and parenting responsibilities). Checking a trap can be done before work for example, but if a cat is captured, the handling and transport time could conflict with other duties. Following neutering, the cat needs to be collected from the vet ahead of closing time. Overall, it takes exceptionally dedicated volunteers, who have flexibility in their other commitments, to invest time and energy in TNVR. In addition, it takes time for such a volunteer to build up the experience to work independently of project staff. Future projects should not expect to rely heavily on volunteer contributions to cat trapping and staff will usually be needed to carry out many of the more difficult duties. If volunteers are to be used for TNVR, recruiting and training a small number of individuals who have the time will be most effective.

4.2.5 Access permission for trapping

Permissions to conduct TNVR were not always forthcoming. Some landowners who allowed us to survey on their ground would not subsequently allow trapping for TNVR. This was primarily the case for estates that conducted predator control activity (including for feral domestic cats). The killing by land managers of a feral or hybrid cat that the project had neutered would be a poor welfare outcome and a waste of project resources. Therefore access refusal doesn’t necessarily create a problem. However, if the project detected a wildcat and was unable to trap because the landowner did not want any feral or hybrid cats, caught as by-catch, neutered and returned, this refusal of access could be frustrating. If future projects have a moratorium on all lethal methods, except euthanasia on welfare grounds, then an alternative strategy for releasing neutered feral or hybrid cats may need to be sought. For example, releasing the cat at an alternative location. Farms with colonies were not always amenable to the concept of trapping and neutering their cats, but their concerns (primarily ‘running out’ of cats for rodent control) could usually be addressed, particularly in discussion with other farmers who had directly observed the benefits. Nevertheless, the time taken to negotiate access from landowners and farmers needs to be considered when planning trapping programmes.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

SWA’s TNVR programme established an excellent system for ensuring highly effective live-capture alongside good welfare. With a higher capture success rate in capturing wild-living domestic and hybrid cats than most programmes targeting wild-living cats, the camera-first, trap-second approach should be one adopted for future work. Volunteer input through surveys was extremely helpful to the work while the programme established good relationships with a number of stakeholders including vets, workers with welfare organisations and landowners. Despite this success, a sufficiently high proportion of the wild-living populations were trapped too rarely to ensure long-term population change. Reflecting on this, a number of recommendations might, if applied, ensure greater success in the future:

- Compulsory microchipping of pet cats so that TNVR workers are better able to identify pets without investing in significant legwork to do so.

- Recruiting volunteers to conduct cat live-capture for TNVR is difficult and something that welfare organisations also find challenging. This is because it can be difficult and dirty work. Conservation and welfare organisations need to work together to ensure that more volunteers from a variety of backgrounds can be recruited. Even so, the ability of volunteers to take the strain of domestic and hybrid cat management should not be over-anticipated. In most situations, paid workers will need to conduct most of the trapping to ensure population change results from a TNVR programme.

- While the cat populations and issues around their management will be different in different areas, all else being equal, a minimum of one full-time staff member is needed to ensure sufficient trapping rates for TNVR per 200km2 of management areas (equivalent to approximately 1.5 staff per Priority Area).

- The need for accurate monitoring needs to be balanced against the need for rapid and effective cat trapping. Reducing the time each camera is at a location prior to setting cage-traps may lessen our ability to assess population density accurately from the cameras. But swifter follow-up on detected cats, and the ability to move cameras more freely when no cats are detected in the first two to three weeks, will improve trapping efficiency and may allow more individuals to be identified for trapping.

- For the long-term management of feral and hybrid cats in Scotland, a regional or national approach will be required.

6. References

Anderson, M.C., Martin, B.J. & Roemer, G.W. 2004. Use of matrix population models to estimate the efficacy of euthanasia versus trap-neuter-return for management of free-roaming cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 225, 1871-1876.

Bielby, J., Donnelly, C.A., Pope, L.C., Burke, T. & Woodroffe, R. 2014. Small-scale badger culling for TB control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111, 9193-9198

Bryce, J. 2015. Feral cat management: Justification for proposed Wildcat Action approach. Background paper A1288389, Scottish Natural Heritage. 14pp.

Campbell, R.D. 2015. Spatial ecology of the Scottish wildcat. Final Report. Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, University of Oxford. 105 pp.

Campbell, R.D. & Griffith, M. 2015. The use of remote cameras for monitoring cage traps during animal trapping. Ecological Research. 30, 963-967.

Donnelly, C., Woodroffe, R., Cox, D. et al. 2006. Positive and negative effects of widespread badger culling on tuberculosis in cattle. Nature 439, 843–846.

Gibson, K.L., Keizer, K. & Golding, C. 2002. A trap, neuter, and release programme for feral cats on Prince Edward Island. Canadian Veterinary Journal 43, 695-698.

Gorman, S., & J. Levy. 2004. A public policy toward the management of feral cats. Pierce Law Review 2:157–181.

Kitchener, A.C., Yamaguchi, N., Ward, J.M. & Macdonald, D.W. 2005. A diagnosis for the Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris): A tool for conservation action for a critically-endangered felid. Animal Conservation 8, 223–237.

Lazenby, B.T., Mooney, N.J. & Dickman, C.R. 2015. Effects of low-level culling of feral cats in open populations: a case study from the forests of southern Tasmania. Wildlife Research, 41, 407-420.

Littlewood NA, Campbell RD, Dinnie L, Gilbert L, Hooper R, Iason G, Irvine J, Kilshaw K, Kitchener A, Lackova P, Newey S, Ogden R, Ross A. 2014. Survey and Scoping of Wildcat Priority Areas. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 768

Loyd, K.T., & DeVore, J.L. 2010. An evaluation of feral cat management options using a decision analysis network. Ecology and Society 15, 10.

Neville, P.F. & Remfy J. 1984. Effect of neutering on two groups of feral cats. Veterinary Record, 114, 447-450.

Nutter, F. 2005. Evaluation of a trap-neuter-return management programme for feral cat colonies: population dynamics, home ranges and potential zoonotic diseases. Dissertation, comparative Biomedical Science, North Carolina State University.

Nogales, M., Martin, A., Tershy, B.R. Donlan, C.J., Witch, D., Puerta, N., Wood, B. & Alonso, J. .2003. A review of feral cat eradication on islands. Conservation Biology 18 (2), 310-319.

Parkes, J., Fisher, P., Robinson, S., & Aguirre-Muñoz, A. 2014. Eradication of feral cats from large islands: an assessment of the effort required for success. New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 38, 307-314.

Potočnik, H., Kljun, F., Raçnik, J., Skrbinšek, T., Adamiç, M. & Kos, I., 2002. Experience obtained from box trapping and handling wildcats in Slovenia. Acta Theriologica 47, 211-219.

Schmidt, P.M., Swannack, T.M., Lopez, R.R. & Slater, M.R. 2009. Evaluation of euthanasia and trap–neuter–return (TNR) programmes in managing free-roaming cat populations. Wildlife Research. 36,117-125.

Scott, K.K. Levy, J.K.& Crawford, C.P. 2002. Characteristics of free-roaming cats evaluated in a trap-neuter-return programme. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association 221, 1136-1138.

Senn, H.V., Ghazali, M., Kaden, J., Barclay, D., Harrower, B., Campbell, R.D., Macdonald D,W. & Kitchener, A.C. 2018. Distinguishing the victim from the threat: SNP‐based methods reveal the extent of introgressive hybridisation between wildcats and domestic cats in Scotland and inform future in situ and ex situ management options for species restoration. Evolutionary Applications, 12, 339-414.

Short, J., Turner, B. & Risbey, D. 2002. Control of feral cats for nature conservation. III. Trapping. Wildlife Research 29, 475 - 487

Tuyttens, F.A.M., Delahay, R.J., Macdonald, D.W., Cheeseman, C.L., Long, B. & Donnelly, C.A. 2000 Spatial perturbation caused by a badger (Meles meles) culling operation. Implications for the function of territoriality and the contrological of bovine tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis). Journal of Animal Ecology. 69, 815–828.

Winter, L. 2004. Trap-neuter release programmes: the reality and the impact. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 225, 1369-1376

ANNEXES

Annex 1: Example guidance for TNVR

1. Introduction

What is TNVR?

TNVR stands for Trap, Neuter, Vaccinate and Return, sometimes also known as TNR (Trap Neuter and Release), and is a non-lethal method of controlling feral cat populations by preventing an individual’s ability to breed and therefore reducing the reproduction rate of the whole population so the overall numbers decline over time.

Why are we doing TNVR to help wildcats?

Though domestic cats (whether house cats, unowned stray or feral cats) are distinct from the Scottish wildcat, they are similar enough that they can breed together and produce fertile offspring. This is called hybridisation (also known as crossbreeding or interbreeding). If the resulting hybrids breed with each other or with other domestic cats or wildcats (backcrossing), this is known as introgressive hybridisation. Introgressive hybridisation is a serious threat to the survival of our native wildcats. If this continues unchecked, with each successive generation there are fewer and fewer wildcat genes in each cat and less chance of the long-term survival of wildcats as a distinct Scottish wild animal.

The TNVR programme is a key part of the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan, which is being implemented to try to halt the loss of our distinctive wildcats. TNVR work is being focused in six key areas in Scotland (known as Wildcat Priority Areas) where we believe there are wildcat populations with the best chance of being sustainable long term, with our help. Reducing numbers of fertile feral cats and poor quality hybrids is key to the success of this plan.

The Aim of our TNVR programme