Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) Specialist Report - Responsible Cat Ownership

This report should be cited as: Campbell, R.D., Burns, V., Bacon, A. and Gaywood, M. (2023). Scottish Wildcat Action final report: Responsible Cat Ownership. NatureScot, Inverness.

Authors and instituions: Roo Campbell, NatureScot, Vicky Burns, NatureScot, Alice Bacon, Royal Dick School of Veterinary Science, University of Edinburgh, Martin Gaywood, NatureScot.

Year of publication: 2023

Keywords

Hybridisation, disease, neutering, vaccinating, microchipping, pets, farms, legislation.

Background to SWA

The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP) was published in 2013 following the input of over 20 partner organisations. This led to the establishment of the Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) project that ran from 2015-2020, funded by the Scottish Government, National Lottery Heritage Fund and others. SWA operated with a team of project staff managed by NatureScot, and associated work was carried out by various partner organisations. The overall work programme was steered by a group made up of ten of the partners. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Cat Specialist Group reviewed the work of the SWA, and other ongoing wildcat conservation work, and provided recommendations for future action (Breitenmoser et al., 2019). A wide range of topics relevant to wildcat conservation were covered during the SWA, and have now been published as a series of reports, of which this is one. These outputs will inform the next phase of wildcat conservation work in Scotland, including the SavingWildcats ‘SWAforLife’ project that runs from 2019-2026.

Background

We identified cat owners as key stakeholders in the conservation of the wildcat because domestic cats could potentially transmit disease to, or interbreed with, wildcats. Pet cats can also enter the feral population through a number of routes, leading to downstream risk to wildcats. Reasons for cats entering the feral population are further complicated by the varying statuses of cats along a spectrum, from owned house cats to unowned feral cats. For example, some cats are ‘stray’, relying on multiple households for food (indeed, some owned house cats visit multiple households too). Therefore ownership is difficult to establish and responsibilities of ownership consequently unclear. With hybridisation occurring within the ‘pet’ cat population too, the situation is even murkier. We recognised a need to ‘turn off the taps’ of new recruits into the feral cat population; through responsible cat ownership we can avoid direct interbreeding with wildcats and reduce disease transmission.

Summary of work

- At the core of our responsible cat ownership strategy was a campaign. Its main aim was to promote the neutering and vaccinating of pet cats, with the additional aim of encouraging the use of pet ID microchip implants. Chips aid the differentiation of owned cats from stray and feral cats when conducting trap, neuter, vaccinate and return programmes.

- We identified three key messages to promote during the campaign:

- Scottish wildcats are really special.

- Cat owners can take action to protect the Scottish wildcats they love.

- Happy healthy pet cats are neutered, vaccinated and microchipped.

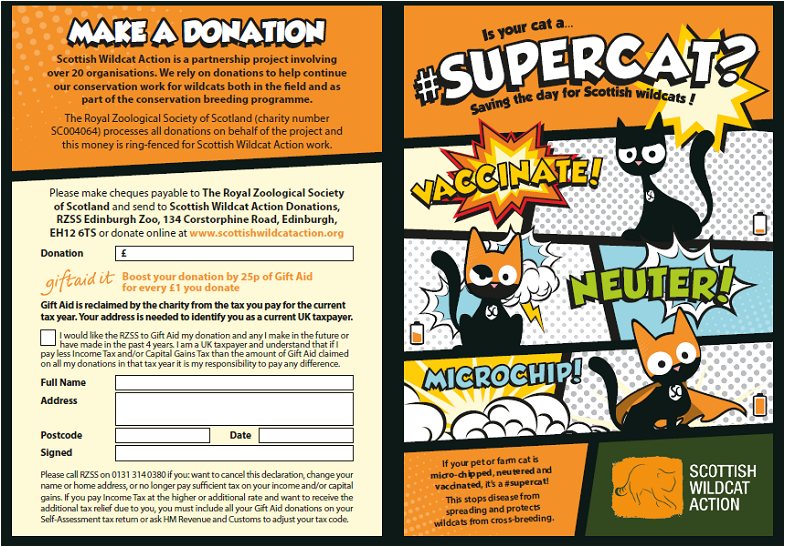

- We branded the campaign #Supercat and worked with a designer to create a comic-book style graphic that featured a ‘normal’ domestic cat turning into a ‘Supercat’ through vaccination, neutering and microchipping. We formally launched the campaign on 28 February 2017.

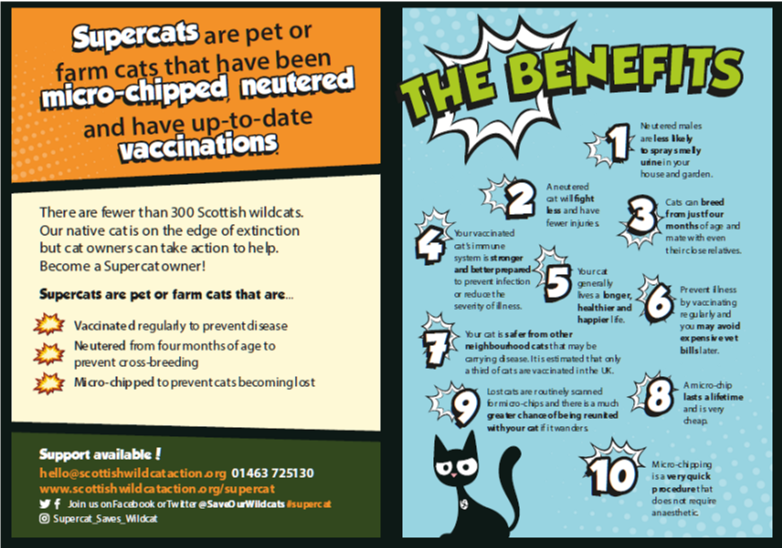

- From this core comic graphic, we created marketing materials including stickers, facemasks, T-shirts, a Facebook filter, posters and a leaflet. The leaflet included an explanation as to why these actions were helpful to wildcats, some key facts about wildcats and ten benefits to neutering, vaccinating and microchipping.

- Stickers and facemasks were available from our website. We also included further information online, including benefits of the procedures to pet cats and to wildcats, and offered cat owners the option of taking a pledge to make their cat a Supercat.

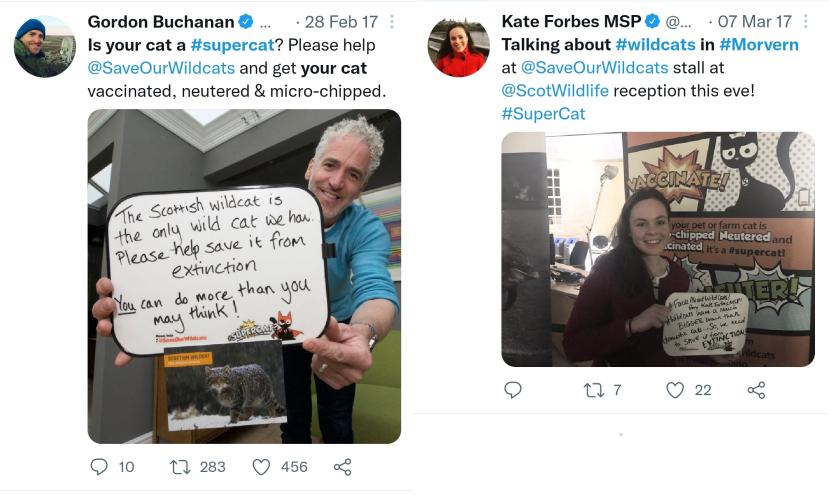

- We promoted the campaign on social media and via our website. We used the #Supercat hashtag on Twitter, and asked project partners to promote the campaign too. We also asked high profile figures to help. This led to a four- to ten-fold increase in engagement through Twitter, but was less effective on Facebook. Over the duration of the project, we published 40 tweets on Twitter with #Supercat, along with 65 Facebook posts.

- A key message promoted during many press and media interviews/articles was that cat owners could help us by getting their pets neutered, vaccinated and microchipped.

- We promoted responsible cat ownership at events in and around our priority areas (PAs) and distributed leaflets around local veterinary practices, as well as working with partner organisations to distribute leaflets to other locations.

- We offered Supercat vouchers to cover the cost of the pet cat procedures within our PAs. Over the project duration, 47 vouchers were used, some for all three procedures and others for one or two (e.g. just microchipping and/or vaccination for pets that owners had had neutered already).

- Through our partners at the R(D)SVS, we surveyed cat owners with a questionnaire. 95% of respondents had neutered their cat(s) already, 85% had vaccinated and 75% had microchipped. Overall, two-thirds had done all of these, indicating that a third of cats could impact wildcats negatively. 53% had already heard about the project (84% of those near one of our PAs), so this sample had an unrepresentatively high number of owners already engaged with responsible cat ownership. This suggests that in the wider population, more than a third of pet cats could potentially negatively impact wildcats.

- Through a student placement we conducted a questionnaire survey of 147 farmers and crofters. Smaller farms and crofts were highly represented in these responses. 39% had cats living on their farm or croft, with an average per farm or croft (from the total) of 0.42 pet, 0.35 farm and 0.27 unowned cats. Neutering and vaccinating rates for pet cats were similar to that reported above (97% neutered and 75% vaccinated). Rates were lower for farm cats (70% and 20%) and lower still for unowned cats (15% and 0%), with 65% of respondents with unowned cats not knowing their status. Consequently at least 10% had had kittens in the past year. The largest barrier to neutering and vaccination was that it wasn’t their responsibility (49%), that they didn’t have time (16%), or that they couldn’t catch the cats (14%). However, other research conducted by R(D)SVS has found a higher level of compliance, with the main barrier to neutering quoted as practicality. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of cats on farms may present a risk to wildcats. We followed this up in our regular column in Farming Scotland magazine by encouraging farmers to have the cats on their farms neutered and vaccinated.

- We did not have the opportunity to assess changes in public attitudes and behaviour around responsible cat ownership over the project duration and would recommend a follow up questionnaire.

- Unneutered and unvaccinated cats will likely present a problem for any future wildcat conservation. Legislation to enforce neutering and vaccination would aid such conservation, but as a minimum, compulsory microchipping would force owners to engage with responsible ownership, provide a ‘census’ of owned cats in Scotland and streamline TNVR (trap, neuter, vaccinate, return) programmes by reducing risks to pet cats.

Acknowledgments

The SWA project was supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

It was also funded by the Scottish Government, NatureScot and the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. Support and resources for associated work was also provided by all the Steering Group members: Cairngorms National Park Authority, Forestry and Land Scotland, National Museums Scotland (NMS), Scottish Land & Estates, NatureScot, Scottish Wildlife Trust, The National Trust for Scotland, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS), The Scottish Gamekeepers Association, The Scottish Government, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU). In addition, Jenny Bryce and Fiona Strachan helped develop the project while Eileen Stuart, Alan Bantick and Andrew Kitchener chaired the Steering Group.

Additional sponsors, funders and contributors to SWA work included Aigas Field Centre, Ailsa Black, British Association for Shooting and Conservation, Cairngorm Brewery Company, Chester Zoo, Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, John Muir Trust, Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, Lukas Ruiter Production, MyPetOnline, NFU Scotland, petDetect, RSPB, Scotland The Big Picture, Swift Ecology, the Highland Council and Robertsons Trust.

We are also very grateful to the many academics, landowners and managers, farmers, foresters, keepers, captive collection managers, veterinary specialists and others who contributed valuable time and effort, members of the public who contributed funds and support, and in particular the many volunteers who got involved in the project.

The responsible cat ownership campaign was developed with the help of other SWA staff (Hebe Carus, Keri Langridge, Emma Rawling, Matt Wilson) and partners, including Prof Anna Meredith (R(D)SVS). Alan Tait Graphic Design developed the fantastic Supercat artwork used in the campaign. Thanks to all the cat owners who responded to the campaign by having their pet cat neutered, vaccinated and/or microchipped, and to the veterinary clinics that agreed to administrate our Supercat vouchers. Special thanks to the celebrities, MSPs, Wildcat Champions, vets and volunteers who helped us promote the campaign. Our thanks also to those who took the time to complete the questionnaires used in this report. Martha Gavan conducted the questionnaire survey through the East of Scotland Bioscience Doctoral Training Partnership (part of the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council’s Doctoral Training Partnerships). Finally, thanks to Roo Campbell’s pet cat, which behaved unusually well at the vet being filmed having a microchip implanted.

1. Background

The wildcat in Scotland is threatened by factors that include hybridisation with the domestic cat (Beaumont et al. 2001; Macdonald et al. 2004; Senn et al. 2019) and possibly the transmission of feline diseases from the domestic cat population (Meredith et al. 2018, see the Disease Surveillance report). One of the main tasks for SWA was to reduce these threats in Priority Areas (PAs, see also the Trap Neuter Vaccinate return Programme report). Any un-neutered, un-vaccinated free-roaming cat is a potential risk to wildcats. Owned cats present a direct risk through interactions with wildcats but also may present an indirect risk through the contribution to the feral domestic cat population. Cats enter the feral population through a number of routes. These include;

- Abandonment of adult cats

- Abandonment of unwanted juveniles

- Birth of kittens from pet cats away from the home, resulting in kittens that fail to socialise to humans

- Neglect of a pet cat resulting in the animal leaving on its own accord.

Abandonment and other reasons for cats entering the feral population are further complicated by the varying statuses of cats along a spectrum from owned house cats to unowned feral cats. For example, some cats are ‘stray’, relying on multiple households for food (indeed, some owned house cats visit multiple households too). Therefore ownership is difficult to establish and responsibilities of ownership consequently unclear. With hybridisation occurring within the ‘pet’ cat population too, the situation is even murkier. During the course of an earlier study around Strathpeffer, the lead author trapped and GPS-collared a wild-living (not associated with houses or farms) neutered hybrid male (Campbell 2015). Only after approximately three months did the cat return to its ‘owner’, who later explained that the cat regularly disappears for extended periods. The owner eventually moved away but the cat stayed and was detected regularly during SWA surveys.

We recognised a need to reduce the number of unneutered and unvaccinated free-roaming owned cats, both to reduce the direct threat these may have for wildcats and to ‘turn off the taps’ of new recruits into the feral cat population. Domestic cat owners are a key stakeholder in the project’s work to conserve wildcats in PAs more widely. This was highlighted under the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP):

2.5 Promote the responsibilities that go with domestic cat ownership to communities in priority areas. Including considering not keeping cats in these areas.

2.5.1 Targeted public awareness within priority areas (cat health and neutering).

Alongside this, one aim set out by a key funder, the National Lottery Heritage Fund, was:

Domestic cat owners will be encouraged to neuter cats in order to prevent inbreeding.

Following the general approach adopted by SWA, the project and partner’s work revolved around conservation action combined with research to better understand the problem. For responsible cat ownership, this involved:

1. A responsible cat ownership campaign

2. Research to investigate current attitudes towards responsible cat ownership

3. Legislative approaches to responsible cat ownership

2. The Campaign

2.1 Key aims and messages

The main communication requirements included:

Delivering positive domestic cat neutering/vaccination/micro-chipping promotions whilst linking this to the protection of Scottish wildcats.

Creating a small number of key messages (sharp, concise, informative) about the contribution of local people to the survival of one of our important native species. These were used consistently across platforms and by partner organisations. The key messages were:

- Scottish wildcats are really special.

- Cat owners can take action to protect the Scottish wildcats that they love.

- Happy healthy pet cats are neutered, vaccinated & microchipped.

2.1.1 Key outcomes

a) More owners will neuter (as well as vaccinate and microchip) their domestic cats, particularly in wildcat priority areas.

b) More Scottish people will recognise the link between neutering, vaccinating and micro-chipping domestic cats with the protection of the Scottish wildcat.

c) We will increase awareness of SWA’s role in saving the Scottish wildcat by engaging with a wider audience.

2.2 Campaign design and material

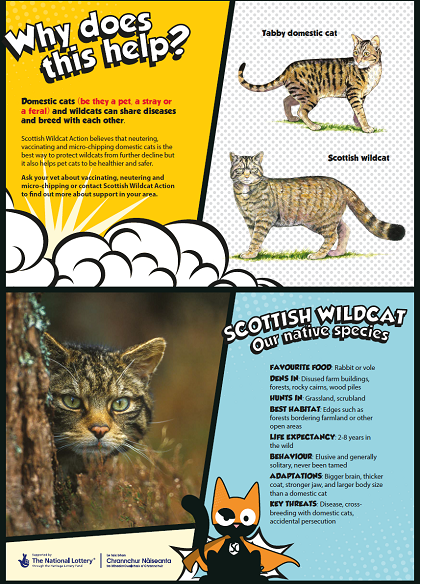

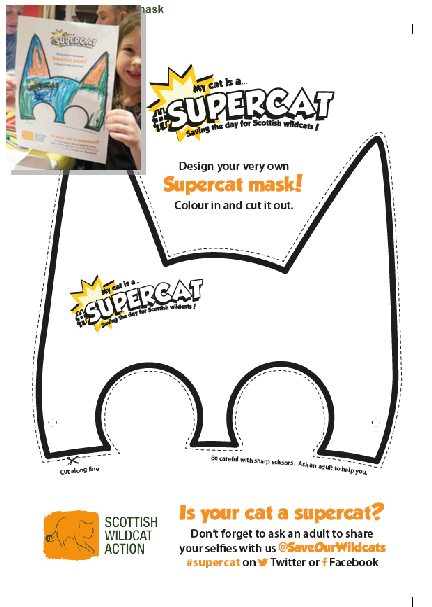

The campaign was branded #Supercat. The project worked with designer Alan Tait to create comic-book style graphics that featured a ‘normal’ domestic cat turning into a ‘Supercat’ through vaccination, neutering and microchipping (Figure 1). The cat’s superpower was illustrated though the addition of a mask, then cape and a battery-level indicator which got progressively fuller as the cat was vaccinated, neutered and microchipped. From this core comic graphic, other marketing materials were created including stickers, facemasks, T-shirts, a Facebook filter, posters and a leaflet. The leaflet included an explanation as to why these actions were helpful to wildcats, some key facts about wildcats and ten benefits to neutering, vaccinating and microchipping (Annex 1). 10,000 copies were printed in its initial run. The facemasks were printed on white card and could be coloured in by children (Annex 2). The campaign was formally launched on 28 February 2017 with a press release.

A flier from the #Supercat campaign showing, in comic style imagery, the transformation of a normal cat into a supercat through a sequence of vaccination, neutering and microchipping.

2.3 Local campaign

During local outreach events, pet cat neutering, vaccinating and microchipping was always highlighted as one way that the audience could help. Leaflets were distributed to local veterinary practices and the project worked with partners to distribute them to other locations. For example, Aberdeenshire Council sent leaflets and posters out to schools, council offices, libraries and museums in their area while Montrose Basin Visitor Centre near the Angus Glens’ PA hosted a Supercat display during Easter 2017. Materials such as Supercat facemasks were used during outreach to children.

In conjunction with this, the project offered Supercat vouchers to cover the cost of neutering, vaccinating and/or microchipping pet cats within our PAs. Vouchers were either managed directly by the veterinary practice or by the local SWA Project Officer. Over the project duration, 47 vouchers were used, some for all three procedures and others for one or two (e.g. just microchipping and/or vaccination for pets that owners had had neutered already).

2.4 National campaign

Supercat section was added to the SWA website. This hosted campaign materials including stickers, facemasks and leaflets; allowed visitors to take a pledge on having their own cat neutered, vaccinated and/or microchipped; allowed visitors to create a #Supercat selfie frame for Twitter and Instagram; provided an FAQ section on the benefits of neutering, vaccinating and microchipping; and provided visitors with the contact details of vets in the PAs.

Two tweets from high-profile supporters of the campaign. The first is from Gordon Buchanan, a wildlife cameraman and presenter, with a photo showing him holding a signs stating “The Scottish wildcat is the only wildcat we have. Please save it from extinction. You can do more than you may Think”. The second is from Kate Forbes, a member of the Scottish Parliament, holding a signs stating “#FactsAboutWildcats from Kate Forbes MSP #Wildcats have a much bigger brain than domestic cats… so we need to save it from extinction”.

The campaign was promoted on social media using the #Supercat hashtag, which was launched by wildlife filmmaker Gordon Buchanan (Figure 2). Project staff also asked other high-profile figures to help promote the campaign. These included Roseanna Cunningham MSP (the Scottish Government’s Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform at the time) and Kate Forbes MSP, alongside the local authority based Wildcat Champions. There were 65 Facebook posts that used #Supercat, which comprised of 50 posts from SWA and 15 from other pages, such as RZSS and Gordon Buchanan. On Twitter, there were 40 posts using #Supercat, which included 26 posts from SWA and 14 posts from other pages.

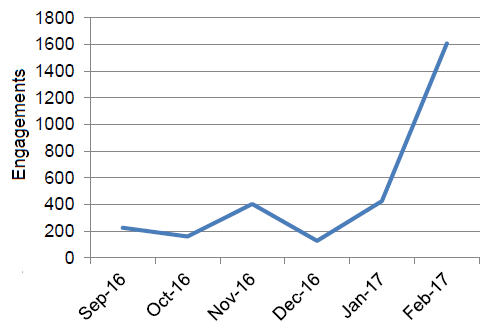

In the months leading up to the campaign, monthly engagement on Twitter was typically 150-400. This increased to 1,600 during February 2017, a four- to ten-fold increase (Figure 3). Engagement on Facebook did not increase as dramatically, though there was already a higher following. As the number of Facebook and Twitter followers increased year-on-year, so did engagement with the #Supercat posts. The majority of #Supercat posts were published within the period between the start of the Supercat campaign in 2017 and up to the launch of the #GenerationWildcat campaign in 2018 (see the Communications report). There were 4,125 views of the Supercat pages on our website throughout the project.

Alongside the online campaign, a press release was issued by NatureScot and was picked up by ten national level publications and a number of local newspapers, blogs and websites. That cat owners could help wildcats by getting their pet cat neutered, vaccinated and microchipped was a key message promoted during many media and press interviews and articles following this. News outlets picked up on this so that, for example, at the launch of the successor Saving Wildcats project in 2019, the BBC highlighted responsible cat ownership despite it not being a key message in the press release.

A graph of date (Sept 2016 to Feb 2017) against monthly Twitter engagements with the project following the launch of the #Supercat campaign. Engagement numbers are around 90 to 400 up until Jan 2017, after which they increase to about 1600.

2.5 Evaluation

Engagement online was high and the message will have gotten out to many. The campaign and associated voucher scheme undoubtedly led to cats being neutered/vaccinated/microchipped that otherwise would not have been. Nevertheless, of the estimated 700,000 pet cats in Scotland, as many as 13% aren’t neutered, 35% aren’t vaccinated when young, and 42% aren’t microchipped (PDSA, 2018). The cheerful cartoon-like campaign may have got the message across to some owners, but there is likely a core of cat owners who aren’t yet engaged with responsible cat ownership. There was no opportunity to assess changes in public attitudes and behaviour around responsible cat ownership over the project duration. A follow up questionnaire based on the work of Alice Bacon (see below) would enable an assessment of this.

3. Research

3.1 Survey of cat owners

Through project partners at the R(D)SVS, a questionnaire survey of cat owners was conducted. See Bacon (2017) for full details. Below is a brief outline of the methods, key results and conclusions.

3.1.1 Methods

The questionnaire survey aimed to assess responsible cat ownership awareness, uptake, motivations and barriers among Scottish cat owners. In particular, the survey focused on neutering, vaccination and microchipping. The questionnaire was hosted online for three months by Bristol Online Surveys (BOS), through the University of Edinburgh. A link to the questionnaire was distributed by all the SWA partners by email and social media, and respondents were encouraged to forward it to their contacts. Responses from cat owners throughout Scotland were included, with 7% of responses from within or near one of the Priority Areas and 19% were within the range of the wildcat in Scotland. 46% of owners lived in a town (including cities), 28% lived rurally, and 26% lived in a village. In total, 1,455 responses were received, of which 1,313 were used in analyses. Of the 132 that were discarded, 67 were not resident in Scotland and 50 did not own cats or had kittens younger than four months of age.

3.1.2 Results and discussion

3.1.2.1 Overall compliance

Neutering rates were high, with 98% of the survey respondents having neutered at least one of their cats (95% having neutered all their cats). Vaccination rates were slightly lower at 85% and microchipping rates lower again at 75%. Overall, two-thirds had done all of these indicating a third of cats could present a risk to the status of the wildcat in Scotland. About half of respondents, 53%, had already heard about the project (84% of those near one of our PAs) so this sample has an unrepresentatively high number of owners already engaged with responsible cat ownership, suggesting in reality more than a third of pet cats could impact wildcat conservation negatively. Indeed, PDSA (2018) reported lower figures for all three: 87% neutering, 65% vaccinated when young, and 58% microchipped, albeit from a smaller sample of 173 cat owners in Scotland.

3.1.2.2 Drivers of compliance

Neutering

An owner being a crofter or farmer is a positive predictor of neutering. However, the sample was small (5% of respondents) and may be biased towards owners already engaged in responsible cat ownership. The most frequently cited reason to have not neutered, was that owners were waiting until their cat was older. This is unsurprising, as recent research has shown neutering compliance at four months old to be low, improving by six months or older, and that despite British Veterinary Association guidelines, vet practices are still poor at encouraging early neutering (Welsh et al. 2013). Unplanned pregnancies in cats between six and 12 months are thought to contribute significantly to unwanted kittens (Murray et al. 2009), and vet and owner education is needed to increase owner compliance.

Vaccinating

Respondent awareness of the disease risks around domestic and feral cats influenced the rate of vaccinating, with greater awareness associated with higher vaccination rates. Outdoor-only cats, though a very small proportion of the total, were least likely to be vaccinated. Expense also played a role, with the respondents who were willing to pay more for vaccinations more likely to vaccinate.

Microchipping

Respondents from urban areas were more likely to have microchipped their cats than those from rural areas, while farmers and crofters were least likely to microchip. As with vaccinating, expense also played a role, for rural owners at least; the respondents who were willing to pay more for microchipping were likely to do so. It is possible that the higher rate for urban cat owners is due to such owners more often purchasing complete pet care plans from their vets, which usually include microchipping as part of the package.

3.1.3 Conclusions

Many of the barriers to responsible cat ownership can be attributed to a lack of understanding of feline physiology, poor awareness of the risks and benefits of interventions, and to a perception of unreasonable financial cost.

There is a real and urgent need for improved cat owner compliance with responsible ownership. Quantifying the current level of compliance, and targeting education campaigns and subsidy schemes appropriately, would be greatly aided by a census of cats and cat owners, as would be achieved by mandatory microchipping legislation.

Changing public behaviour is notoriously difficult, and is more likely to be achieved with incentives of advantages for owners, or for their pets, than by encouraging owners to adopt behaviours to support conservation efforts (Robertson, 2008). Secondary achievement of responsible cat ownership as a result of these primary motivations should not be underestimated. Education campaigns focusing purely on wildcat conservation may not be as successful as those that reiterate and reinforce messages about the pet health advantages, and owner lifestyle benefits, resulting from responsible cat ownership. However, such campaigns have been run by multiple organisations over several decades, and non-compliance is still a problem. Again, legislation requiring responsible cat ownership practices may ultimately prove most effective (see 4).

3.2 Survey of farmers and crofters

Martha Gavan, a postgraduate student on placement, conducted a questionnaire survey for farmers and crofters. The focus was on farming practices that might impact wildcats (see the Land Management report). Included in the questionnaire under ‘Part B’ were questions on the presence of domestic cats on farms and crofts and their management. The information below summarises the main findings from responses to Part B.

3.2.1 Sample

Questionnaires were sent out to 927 crofters registered with the Crofting Commission and we received 102 responses (an 11% response rate). In addition, the questionnaire was distributed online, receiving 32 responses, and an additional 12 responses were received following face-to-face contact. The total sample was 147 farmers and crofters and smaller farms and crofts were highly represented. Most responses (74%) were from the Highlands.

3.2.2 Results

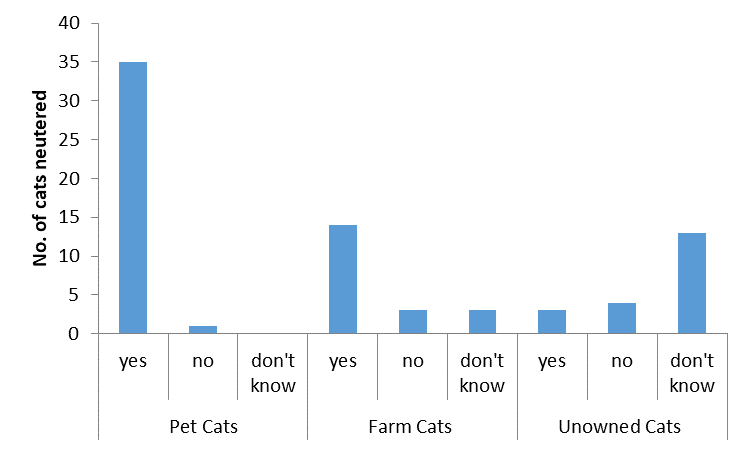

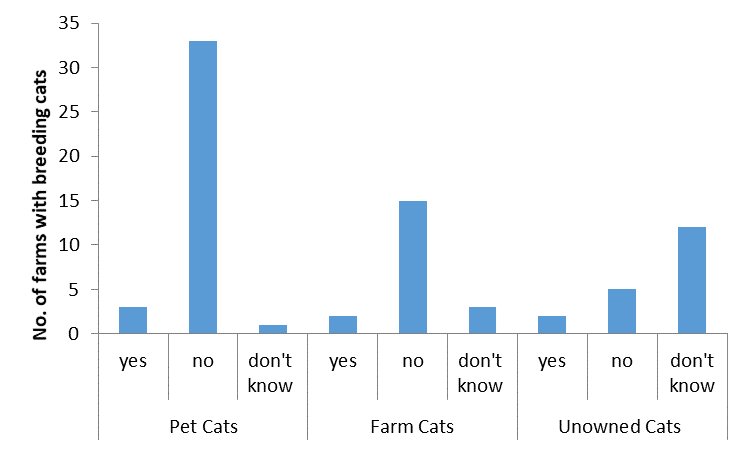

A bar chart showing the responses from the questionnaire on the numbers of the pet, farm and unowned cats on their property that were neutered, as far as they were aware. Most pet (97%) and farm (70%) cats were neutered, whereas for unowned cats, most respondents didn’t know their status (65%).

Over a third, 39%, of respondents had cats living on their farm or croft. These included pet cats (allowed into the house), farm cats (cats the farmer or crofter took responsibility for) and unowned cats (cats that were seen living around the property but for which the farmer or crofter took no responsibility). Including respondents who stated they had no cats, this is equivalent to an average per farm or croft of 0.42 pet, 0.35 farm, and 0.27 unowned cats. Neutering and vaccinating rates for pet cats were similar to that reported by Bacon (2017), with 97% neutered and 75% vaccinated (Figure 4). Rates were lower for farm cats (70% neutered and just 20% vaccinated) and lower still for unowned cats (15% and 0%). However, 65% of respondents with unowned cats did not know their status and therefore some of these unowned cats may have been neutered and vaccinated by others. Not surprisingly, at least 10% of farm and unowned cats had had kittens in the past year (Figure 5).

A bar chart showing the responses from the questionnaire on whether the pet, farm and unowned cats on their property had kittens in the past year. For most pet and farm cats, the response was none. For unowned cats, the most common response was that they did not know.

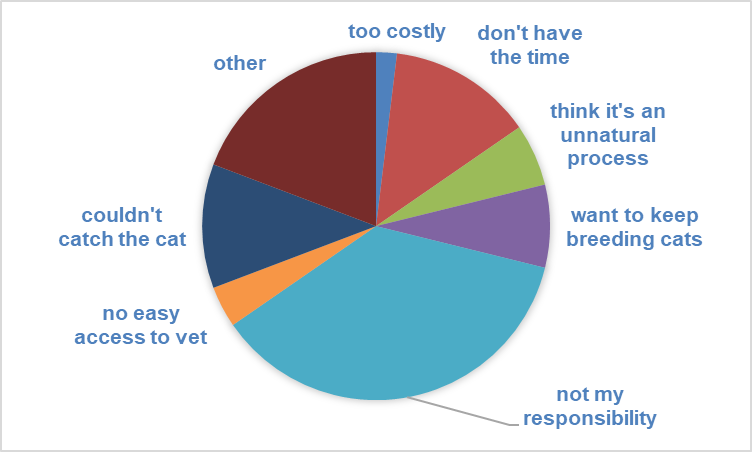

Forty three respondents with cats (74%) gave a reason as to why some or all of their cats weren’t neutered or vaccinated. Participants could select more than one option. The largest barrier to neutering and vaccination was that it wasn’t their responsibility (49%), that they didn’t have time (16%), or that they couldn’t catch the cats (14%), with 16% giving ‘other’ as a reason (Figure 6). ‘Other’ reasons mainly fall under the category of vaccination not thought of or known to be important.

The vast majority of respondents with cats on their property commented that they kept cats to control the rodent population, because they like them as pets, or as a combination of both. However, there were also some comments that they don’t actively encourage cats to their property but instead they just turn up and stay there. This is likely the main reason that many farmers and crofters felt that the care of these cats isn’t their responsibility.

Reasons include not my responsibility, other, want to keep breeding cats, don't have the time, think it's an unnatural process, too costly, no easy access to vet and couldn't catch the cat.

3.2.3 Conclusions

A substantial proportion of cats on farms present a risk to wildcats. SWA had a regular column in Farming Scotland magazine. Following this work, the project used the column to encourage the neutering and vaccination of cats on farms. Lack of perceived responsibility, lack of time or ability to catch the cats, and a lack of access to vets are, in combination, responsible for most cats going unneutered or vaccinated. SWA’s neutering and vaccinating work on farms in its PAs (see the Trap Neuter Vaccinate Return Programme report) will have resolved some of these issues for a subset of farmers in the short-term. However, longer-term and more widespread impact will be gained by ensuring that farmers and crofters are more aware of their responsibilities, perhaps through clear legislation, combined with assistance in catching and transporting cats to vets. Organisations such as Cats Protection (CP) and the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SSPCA) are well placed to offer such assistance and indeed do so. However, a more pro-active approach may be needed to ensure that cats on farms are more routinely neutered and vaccinated.

4. Legislative approaches

4.1 Why consider legislation?

It is clear from the monitoring work carried out by SWA (see the Monitoring report) that there is a significant issue with feral domestic and hybrid cats in Scotland. It is also evident that the capture and neutering of sufficient numbers of these cats to reduce their numbers in the long-term is challenging (see the Trap Neuter Vaccinate Return Programme report). The large amount of neutering work carried out by welfare organisations, while important, does not appear to have resulted in fewer feral cats (e.g. see Stirling, 2017). Pet cat neutering rates have been consistent over recent years (c.90-93% of pet cats in the UK, PDSA, 2019). In addition, as discussed above, the difficulty in identifying pet cats from feral cats creates problems for organisations that trap cats for neutering. If we are to achieve our long-term vision of restoring the wildcat more widely across Scotland, a workable, effective and achievable solution to domestic cat management is fundamental. Statutory measures could help reduce the threat to wildcats posed by domestic cats. Such measures would also improve the welfare of domestic cats both immediately and in the longer term, while being acceptable to, and supported by, the wider community (see also Roberts, 2016). From early on in the SWA project, the SWCAP Steering Group that oversaw its implementation discussed the benefits of a legislative approach (e.g. see Annex 3).

4.2 Legal measures for responsible pet ownership

There are a number of options for statutory measures focussing on pet ownership that were identified by the SWCAP Steering Group. These were:

(i) No change to current arrangements.

(ii) Amendment of the INNS (Invasive Non-Native Species) code to highlight best practice to neuter/vaccinate/chip all pet domestic cats. Exceptions to this code may include provisions that apply to registered cat breeders and, for example, professional veterinarian discretion in employing vaccinations. This could be applied at different geographical scales e.g.:

- Priority Areas for wildcat conservation (and buffer zones)

- Regional e.g. local authority or national parks

- National

(iii) Compulsory legal measures that would prevent ownership of pet domestic cats unless they were neutered/vaccinated/chipped (with some exceptions*). These could include ‘Special Control Orders’ (SCOs) as set out in the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended) – these are compulsory and can be used to compel certain actions in regard to invasive non-native species. This could be applied at different geographical scales as described in option (ii) above.

(iv) A combination of (ii) and (iii) above, which could be phased in over time.

(*Exceptions may include provisions that apply to registered cat breeders and, for example, professional veterinarian discretion in employing vaccinations.)

4.2.1 Consideration in selecting legislative options

Option (i), based on our experience, is not viable if we are to have a realistic and reasonable chance of conserving the wildcat in Scotland. The numbers of un-neutered domestic cats are currently too high, current voluntary schemes are clearly inadequate, and pet domestic cats will continue to bolster the feral domestic cat population.

Option (ii) by itself will inevitably have some appeal to decision-makers as it presents a less heavy-handed approach than option (iii). NatureScot understands amending the INNS code would not make neutering/vaccinating/chipping cats compulsory, although the application of this recommended best practice by any person could be used in a court of law as evidence. The amendment of the code could also provide a useful ‘hook’ to promote and explain the rationale of responsible pet ownership. However, ultimately we have concerns that this would be regarded as guidance, rather than a compulsory requirement, and would not result in the level of action by cat owners that is required.

Option (iii) applied successfully at the national scale would significantly reduce the risk to wildcats into the longer-term. Careful and sensitive communication and education would be required to minimise some shorter-term risks, such as a possible increase in abandoned pet domestic cats in the countryside immediately after such legislation came into force, and a negative response from some of the public who might consider this heavy-handed. In applying this option, the value of maintaining and increasing public support for wildcat conservation would need to be recognised. Responses from welfare and veterinary organisations to a recent compulsory neutering campaign (Stirling, 2017) raised concerns around enforcement, the costs of neutering, and the implications of compulsory neutering for cat abandonment rates. Indeed, only SWCAP partner organisations were supportive of the proposal. A consensus across all stakeholders seems more likely if the compulsory element of such legislation was restricted to microchipping. This would provide some direct benefits to ongoing wildcat conservation by helping identify pet cats but would not be perceived to contain the same pet abandonment risks as compulsory neutering. Microchipping would furthermore act as a first step to increasing responsible ownership by encouraging the owners of c.10% of unneutered cats to have a conversation with their vet about the benefits of neutering.

The above options were provided to the Scottish Government as part of the SWCAP Steering Group response to Stirling (2016), in which the Steering Group recommended that a version of option (iv) should be applied. As a minimum this should start with the application of option (iii) as soon as possible within PAs for wildcat conservation and surrounding buffer zones up to 2025 and beyond, extending to the whole of Scotland after 2025.

If option (iii) starts within PAs for wildcat conservation first, then this phase could be used as an opportunity to further monitor and learn more about responsible cat ownership and public attitudes. A coordinated, parallel programme of education and communication would need to be run prior to, and during, the launch of any change to the legislation. We would anticipate that over time the public will become more aware and supportive of the aims and benefits of responsible cat ownership measures to domestic cat welfare, and wildcat conservation.

5. Future Directions

While compliance with neutering of pet cats is high in the UK, it doesn’t take many unneutered individuals to contribute to the feral cat population. Getting the last ~5% of owners with unneutered pets is always going to be a difficult task. More of an issue may be the lack of clearly defined responsibilities that come with ‘ownership’ for a significant number of cats (Roberts, 2016). In that sense, responsible cat ownership overlaps with feral cat management. Compulsory microchipping of pet cats would underscore the responsibilities of cat ownership to their owners, forcing those who haven’t neutered their pet to visit a vet, where the process of neutering and vaccination can be discussed. Microchipping would also have the advantage of making identification of pets easier during Trap Neuter Vaccinate and Return programmes. While any ‘un-chipped’ cat can legally undergo neutering through a TNVR programme, neutering pet cats without owners’ consent can lead to negative publicity and reputational damage to a project, hampering work with communities that encourage pet neutering and identification of feral cats. A public information campaign would still be required in conjunction with such legislation, to raise awareness and ensure compliance.

Compulsory microchipping can be considered a minimum requirement to aid wildcat conservation in Scotland. An additional step would be to provision for compulsory neutering and vaccinating, either nationally or, through changes to the INNS code, at local or regional levels, where concerns around hybridisation with wildcats are particularly relevant. A first step could be trialling this latter approach in certain wildcat areas (e.g. where wildcats are being released as part of a conservation translocation) to assess its effectiveness and to learn how to avoid unintended consequences, such as pet abandonment. For such a trial, funding to help cat owners cover the costs of microchipping would be needed.

6. References

Bacon, A. 2017. Responsible cat ownership attitudes and behaviours in the context of Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris) conservation. MVSc dissertation. University of Edinburgh. 60pp.

Beaumont, M., Barratt, E.M., Gottelli, D., Kitchener, A.C., Daniels, M.J., Pritchard, J.K. & Bruford, M.W. 2001. Genetic diversity and introgression in the Scottish wildcat. Molecular Ecology, 10 (2), 319-336.

Campbell, R.D. 2015. Spatial ecology of the Scottish wildcat. Final report. Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, University of Oxford. 105 pages.

Macdonald, D.W., Daniels, M.J., Driscoll, C., Kitchener, A.C. & Yamaguchi, N. 2004. The Scottish Wildcat: analyses for conservation and an action plan. Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, University of Oxford, 67 pages.

Meredith, A., Bacon, A., Allan, B., Kitchener, A., Senn, H., Brooks, S., Kortland, K., Hetherington, D. and Davies, S. 2018. Domestic cat neutering to preserve the Scottish wildcat. Veterinary Record, 183, 27-28.

Murray, J.K., Whitmarsh, A., Gruffydd-Jones, T.J., Roberts, M.A. 2009. Survey of the characteristics of cats owned by households in the UK and factors affecting their neutered status. Veterinary Record, 164, 137-141

PDSA. 2018. PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) report 2018 – Scotland summary. 8pp. Accessed 15 Jul 2020.

PDSA. 2019. PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) report 2019. 29pp. Accessed 29 Mar 2021.

Roberts, M. 2016. Feline lost: making microchipping compulsory for domestic cats. Veterinary Record, 179, 178-179.

Robertson, S.A. 2008. Review Article: A review of feral cat control. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 10, 366-375.

Senn, H.V., Ghazali, M., Kaden, J., Barclay, D., Harrower, B., Campbell, R.D., Macdonald D,W. & Kitchener, A.C. 2018. Distinguishing the victim from the threat: SNP‐based methods reveal the extent of introgressive hybridisation between wildcats and domestic cats in Scotland and inform future in situ and ex situ management options for species restoration. Evolutionary Applications, 12, 339-414.

Stirling, E. 2017. PE01674: Managing the Cat Population in Scotland. Petition to The Scottish Parliament. Accessed 29 Mar 2021.

Welsh, C.P., Gruffyd-Jones, T.J., Murray, J.K. 2013. The neuter status of cats at four and six months of age is strongly associated with the owners’ intended age of neutering. Veterinary Record, 172, 22, 578-586.

Annexes

Annex 1: #Supercat leaflet pages

Front cover

Back cover

Centre cover

Annex 2: #Supercat facemask

Colour in mask and cut out.

Annex 3: RCO paper produced by the Steering Group

Proposal for additional control measures on domestic cat ownership in Scotland. (submitted by Anna Meredith to SWCAP Steering Group, June 2016)

Scottish Wildcat Action

Proposal for additional control measures on domestic cat ownership in Scotland as a conservation action to protect the Scottish Wildcat.

1. Introduction and background

1.1 The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP), launched in 2014, is an evidence-based national activity plan that aims to deliver a comprehensive programme of actions over five years to reverse the decline of the Scottish wildcat and secure its future as an iconic Scottish predator species. The Action Plan represents the contributions of leading wildcat experts from over 20 key organisations and focuses on land management, responsible domestic cat ownership, feral cat control, and conservation breeding, underpinned by rigorous scientific and technical oversight and ongoing reactive monitoring of wildcat populations. Effective communication, with stakeholder and public engagement, are recognised as key to the success of the Action Plan, and for its legacy to continue beyond its five-year scope.

1.2 The Scottish wildcat faces a unique threat among endangered species in Scotland in that one of the key factors contributing to the species’ decline is dilution of its genetic integrity by hybridisation with the domestic cat. This situation is rarely encountered in species conservation, whereby a closely related non-native domesticated species has largely unhindered access to opportunities to interact and interbreed with a wild-living endangered species.

1.3 The threat of ongoing hybridisation is posed by both un-owned feral domestic cats and un-neutered owned domestic cats, due to the potential ability of both categories to roam freely in wildcat habitat. Domestic cats have retained the innate ability to hunt live prey (e.g. rodents and birds) and are thus able to utilise and survive on a wild diet, competing with the wildcat for food, and straying into wildcat territory where hybridisation can then occur between the two species.

1.4 There are estimated to be at least 100,000 feral cats (defined as being un-owned) in Scotland (Cats Protection). Feral cats vary from truly free-living and independent of man, relying solely on predation for food, to being partially or wholly dependent on man via food sources that are either deliberately or unintentionally supplied.

1.5 Owned domestic cats may also be under varying degrees of human control and either wholly or partly dependant on man for food and shelter. Although some are kept solely as house pets and never have access to the outdoors, cats are unique among domestic pets in the UK in that most are allowed to have unlimited free access to the natural environment (urban or rural) without any direct physical control or confinement, and without the owners being aware of their whereabouts or interactions with other animals. Despite this, the expectation is that an owned cat will return and is dependent on its owner for (most of its) food and other requirements.

1.6 In 2015, 25% of UK households owned a cat and there are an estimated 11.1 million pet cats in the UK (PDSA, 2015). Numbers of owned pet cats in Scotland are not known. Current estimates of neutering levels of pet cats in the UK range from 64.8% in a survey of 4009 cats with known causes of mortality in England (O’Neill, 2015), to 92% in a survey of 12,334 cat owners (PDSA, 2015). In the same survey, the PDSA (2015) found that 46% of cats were microchipped and 74% vaccinated; but 9% of owners reported their cat had had one litter and, of these, 65% report their cat’s pregnancy was unplanned. However, levels of neutering and microchipping in Scotland are not known, and feral cat populations remain large, due to continuing reproduction and influx of new animals, e.g. unwanted or abandoned (stray/previously owned) cats, as well as ongoing opportunities for existing feral cats to mate with un-neutered owned cats. This is also due to the high reproductive rate of domestic cats (one female cat, a mate, plus their kittens can produce up to 400,000 kittens a in seven years, even accounting for only 25% of the kittens surviving to reproductive age).

1.7 Due to their ability to roam freely, both feral cats and owned cats have the potential to encounter wildcats or already existing hybrids, and if un-neutered, breed. In addition, direct and indirect contact with wildcats is a pathway for disease transmission. Common pathogens of domestic cats have been identified in wildcats, and the scientific assumption is that these have been acquired from the domestic cat (Leutenegger et al. 1999; McOrist et al. 1991; Millan and Rodriguez, 2009).

1.8 In addition to the threats of hybridisation and disease to wildcats, both feral and owned cats are known to predate significant numbers of wild species. Globally, there is increasing evidence of the ecological impacts of free-ranging cats via direct predation on native prey (Crooks and Soulé 1999; Baker et al. 2005; Slater, 2005; van Heezik et al. 2010; Loss et al. 2013), and they are listed as one of the 100 worst invasive species in the world (Lowe et al. 2000). For example, one UK study over a five-month period estimated that nine million cats predated 92 million prey items (Woods et al. 2003), consisting of 57 million mammals, 27 million birds and five million reptiles and amphibians. Domestic cats therefore pose a potential conservation threat to many wildlife species, not just Scottish wildcats, although the extent of the impact on Scottish wild animal populations is unknown.

1.9 A recent study (Gramza et al. 2016) highlights that long-term solutions to the issue of free-ranging domestic cats will necessitate human behaviour change, and indicates that changes in risk perceptions may result in behaviour change. Public awareness of cat-related risk perceptions and attitudes such as to native species conservation and disease risks could be used to develop communication programmes aimed at promoting risk-aversive behaviours among cat owners and cat-management strategies that are both acceptable to the public and directly advance conservation of native species (Gramza et al. 2016).

2. Legal considerations

2.1 In Scotland, feral cats and hybrids are considered as a non-native species under the Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011, which significantly amended the provisions under Section 14 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. These aim to prevent the release and spread of non-native animals (and plants) into areas where they can cause damage to native habitats and species or economic interests. In Scotland, there is a presumption of ‘no-release’ for species that are out-with their ‘native range’. Under this legislation, a ‘release’ offence for a non-native animal constitutes releasing, allowing to escape from captivity, or causing to be out-with the control of any person, at a place out-with its native range. An animal is considered to be ‘released’ when it is no longer under human control (NatureScot Native Range Guidance, 2014).

2.2 Circumstances in which animals are not considered to be ‘released’ include: animals kept in enclosures from which they cannot escape; free-range livestock which can be gathered for husbandry purposes; and pets or working animals that are expected to return to their owners. Therefore, owned cats that roam freely are not normally considered ‘released’.

2.3 Release of a feral cat or hybrid may be allowed under a non-native species licence from NatureScot (e.g. after being temporarily captured for neutering purposes (see section 3).

2.4. Currently there are no requirements for pet cats to be registered or individually identified. In contrast, compulsory microchipping of pet dogs and registration on one of the authorised commercial databases was introduced in the UK in April 2016. There is also no requirement for an owner to be aware of their cat’s whereabouts, but to be not considered non-native, it must be expected to return. A timeframe for, or frequency of, this expectation is not defined. In contrast, it is still a legal requirement under the Control of Dogs Order 1992 for a dog to wear a collar with the owner's name and address on it when in a public place. Both the Dogs Act 1871 and the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 require an owner to have proper control of their dog.

2.5 The Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006 requires that cat owners have a duty of care to ensure that the welfare needs of an animal are met. This applies to all owned cats, (i.e. considered under human control), even if they live wholly or partly in a free-ranging state e.g. farm cats. Under this Act, the Scottish Government Code of Practice for the Welfare of Cats recommends that owners consider neutering their cat to prevent unwanted kittens, reduce wandering behaviour and for numerous health benefits, including the limiting of spread of infectious disease. It also recommends individual identification of cats by microchipping, or alternatively by the wearing of a collar, but this is considered a less secure method and has the potential for causing injury.

2.6 There are currently no requirements for compulsory neutering of owned pet animals not required for breeding. Although the breeding of dogs, where they produce more than five litters per year, is controlled (The Breeding of Dogs Act 1973 and the Breeding and Sale of Dogs (Welfare) Act 1999), this does not cover neutering and there is no similar legislation for cats. Many other countries have now adopted, or have under consideration, legislation requiring compulsory neutering of both cats and dogs, with an exemption system for licensed breeders, e.g. Australia, certain areas of the USA, Belgium. These schemes have arisen out of the recognition that there is an urgent need to control and reduce the high numbers of unwanted cats being abandoned and requiring euthanasia or continuously contributing to the feral cat populations, rather than for conservation of a closely related wildcat species. Such schemes have varying degrees of compliance and success.

3. Current and previous control measures to prevent hybridisation of domestic cats with wildcats

3.1 Voluntary neutering of owned cats will prevent breeding with feral, hybrid or wildcats and cut off a source of unwanted kittens that may be abandoned or released. Neutering also reduces roaming and fighting behaviour that contributes to interactions that promote the spread of feline infectious diseases. Levels of neutering of owned cats in Scotland are not currently known.

3.2 Trap, neuter, release (TNR) or trap, neuter, vaccinate, release (TNVR) programmes are recognised and recommended in international studies and guidelines as a valid option for unowned cat management (ISFM, 2013; WSPA, 2011) and are carried out by some charities and voluntary organisations, e.g. Cats Protection. TNVR is a key action of the SWCAP to reduce the threat of hybridisation and spread of disease, and will be carried out in combination with existing schemes.

3.3 For TNR to be effective in reducing populations, sustained levels of at least 71-94% of the population being neutered are required (Natoli et al. 2006). However, the authors of one study (Natoli et al. 2006) concluded that, in the absence of a public education campaign to stop people from abandoning cats, i.e. to ‘turn off the tap’, TNR efforts of feral cats are “a waste of money, time and energy.” In addition, these figures of >70% are derived from defined urban populations, whereas required levels and effectiveness for more diffuse rural populations are not known, but are likely to be higher.

3.4 A targeted TNR programme in the Cairngorms National Park (Cairngorms Wildcat Project) between 2005 and 2011 resulted in seven veterinary practices neutering >7500 cats (2005-2011), and Cats Protection neutering 3200 cats, both feral and owned. However, this has been discontinued, and any lasting effect on cat populations in this area is not known.

4. Key issues surrounding feral and un-neutered domestic cats

4.1 Although some feral cats are not reliant on humans for food or shelter, they are clearly non-native. The degree of control and declaration of ‘ownership’ considered necessary to mean that a free-ranging cat is feral (unowned) or owned is ill-defined and subject to interpretation. For example, a person may state that they ‘own’ a cat even if they did not originally acquire it, do not feed it, and it lives entirely in a free-ranging state with no human control over its movements. Whereas in other situations, a clearly unowned or previously-owned ‘stray’ cat may be fed by a person, either regularly or occasionally, but they clearly state that they do not own that animal.

4.2 Owners of un-neutered domestic cats that are allowed to range freely have no control over where they go, or their reproductive activity (if un-neutered), either with other domestic cats, or with hybrids or Scottish wildcats.

4.3 Advocates of responsible pet cat ownership, such as the veterinary profession and animal welfare charities, widely promote routine neutering and vaccination against common infectious diseases.

5. Proposal

5.1 SWA proposes that, due to the unique threat posed by feral and un-neutered domestic cats, effective conservation of the Scottish wildcat requires urgent introduction by the Scottish government of additional statutory control measures on domestic cat ownership. Current voluntary schemes are clearly not sufficient to reduce and ultimately prevent the recruitment of free-ranging and unowned fertile cats that are able to hybridise with Scottish wildcats and pose the major direct threat to its conservation and survival. In combination with the existing conservation interventions in priority areas described in the SWCAP, we propose these measures are necessary to ensure the continued effectiveness of conservation measures across the whole of Scotland after the five-year scope of the current Action Plan.

5.2 It is proposed that these additional measures are:

- A clear and unambiguous definition of what constitutes ownership and control of a domestic cat, and the responsibilities of such ownership. These will include:

- Compulsory neutering of all* owned cats in Scotland to prevent hybridisation with wildcats or existing hybrids, and to minimise the threat from feline infectious diseases. *A licensed exemption scheme will allow continued responsible breeding of domestic cats.

- Compulsory identification of all cats by microchipping and their registration on an authorised commercial database.

5.3 The proposed measures are applicable to the whole of Scotland. Restriction to the currently identified wildcat priority areas or other areas where Scottish wildcats may exist would be almost impossible to define and discriminate against cat owners within such areas. The additional significant benefits to domestic cat welfare and health (as defined in the Code of Practice for the welfare of cats), and potentially other wildlife species, mean that these measures are equally applicable to all domestic cat owners.

5.4 Neutering and microchipping provides the opportunity for consideration and direction of an appropriate preventive medicine programme (e.g. vaccination, anti-parasitic treatment, etc.) of all cats by a veterinary surgeon. Exact requirements, such as diseases included, age of vaccination, exemptions, and frequency of vaccination should be determined by the veterinary surgeon.

5.5 Consideration will need to be given to subsidised neutering, microchipping and vaccination schemes to promote and encourage compliance. Emphasis on the conservation rationale to save the Scottish wildcat from extinction, in addition to the health and welfare benefits to domestic cats, should be encouraged.

Professor Anna Meredith, Lead – SWACP TNR subgroup May 2016.

References

Baker PJ, Bentley AJ, Ansell RJ, Harris S. (2005) Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area. Mammal Review 35:302–312.

Scottish Government. Code of Practice for the Welfare of Cats.

Crooks KR, Soulé ME. 1999. Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system. Nature 400:563–566.

Gramza A, Teel T, VandeWoude S, Crooks K. (2016) Understanding public perceptions of risk regarding outdoor pet cats to inform conservation action. Conservation Biology;30(2):276-86.

ISFM (2013) ISFM Guidelines on Population Management and Welfare of Unowned Domestic Cats (Felis catus)

Loss SR, Will T, Marra PP. (2013) The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nature Communications DOI:10.1038/ncomms2380.

Leutenegger CM et al. (1999) Viral infections in free-living populations of the European wildcat. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 35, 678-686.

McOrist S Boid R, Jones TW, Easterbee N, Hubbard AL, Jarrett O.(1991) Some viral and protozoal diseases in the European wildcat (Felis silvestris). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 27, 693-696.

Millan J, Rodriguez A (2009) A serological survey of common feline pathogens in free-living European Wildcats (Felis silvestris) in central Spain. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 55, 285-291.

Natoli E et al. (2006) Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy). Preventive Veterinary Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2006.06.005

O’Neill DG , Church DB, McGreevy PD,Thomson PC, Brodbelt DC (2015) Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 17(2) 125–133.

WSPA (2011) International Companion Animal Management Coalition (Humane Cat Population Management Guidance)

PDSA (2015) Animal Wellbeing Report 2015.

Slater, M (2005) The welfare of feral cats. In: The welfare of cats, I. Rochlitz (ed), Springer, The Netherlands, 141-175.

Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (2013) Scottish Natural Heritage

van Heezik Y, Smith A, Adams A, Gordon J. (2010) Do domestic cats impose an unsustainable harvest on urban bird populations? Biological Conservation 143:121–130.

Woods, M., Macdonald R., Harris S (2003) Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain. Mammal Review 33 (2) 174–188.

Roo Campbell, NatureScot, Great Glen House, Leachkin Road, Inverness, IV3 8NW.

Telephone: 01463 725130

Email: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-1-78391-983-3

This publication is part of a series of specialist reports on the work of the Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) project that ran from 2015-2020. The work was led and steered by a partnership of organisations: Cairngorms National Park Authority, Forestry and Land Scotland, National Museums Scotland, Scottish Land & Estates, NatureScot, Scottish Wildlife Trust, The National Trust for Scotland, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies (R(D)SVS), The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, The Scottish Gamekeepers Association, The Scottish Government, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU).

The many other partners and funders are listed in the SWA Summary report.

For more information, including access to the other reports, contact Martin Gaywood at NatureScot.

This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of NatureScot or the relevant authors. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of NatureScot. © NatureScot 2023.