River types

From fast and furious steeply flowing burns to wide meandering rivers, Scotland’s great range of running waters is fascinating.

Such a variety of river types provides Scotland with a great diversity of river habitats and landscapes. Below is a selection of our most typical river types.

Rivers descending the mountains

Bedrock reaches, slot gorges and waterfalls

Narrow rock chasms, slot gorge channels and freefall waterfalls are steep and often spectacular. Sub-glacial meltwaters originally carved out many of our deep-sided bedrock channels.

Mountain torrents

These steep boulder bed burns can move very large rocks in their beds during flash floods. Many torrents rework the old glacial sediments that plaster Scottish mountainsides, but some erode gullies in vulnerable bedrock.

Alluvial basins

Rivers form these small areas of flatter ground where they deposit flood-borne sediment. In many Highland glens, these basins have bedrock-controlled river channels both upstream and downstream of them.

Debris cones and alluvial fans

Mountain torrents, especially in steep gullies, deposit these small steep fans of sediment where they meet the valley floor. The steeper the gully, the more likely it is that the burn will carry slurries of rock and water (debris flows).

Rivers in glens and straths

Wandering gravel bed and braided rivers

Upland Scotland has a great many wide gravel bed rivers. Some have more than one actively migrating channel, and their many reaches can form gravel islands. Such rivers are most common where there are large amounts of glacially derived sands and gravel deposits to rework – these are often stored in wide straths or valleys as high river terraces.

Scotland has some amazing braided rivers, which have multiple threads of channels that divide and rejoin to form an almost fishnet-style network. Channels may form and be abandoned during floods. If there’s a long time between big floods, the river may gradually rework its gravels and adopt a more meandering path.

Lake deltas

A delta often forms where a river enters a loch, as the river flow slows and sediment is dropped into the loch water. The delta’s shape depends on how much sediment the river or burn carries and how ‘flashy’ its river flow regime.

Tributary river alluvial fans

Alluvial fans often occur where a side valley river meets a main valley and river. They’re formed as the tributary river switches its channel path every so often over a very long period. Once sediment deposition causes the channel path to become raised above the surrounding land, the river is more likely to switch direction and flow through adjacent lower-lying land.

Rivers crossing the lowlands

Meandering rivers

These are typically single-channel, sand-bedded rivers that flow over wide, flat floodplains. The channel evolves and migrates across the floodplain in response to the flow path of the channel current (thalweg). As the outside bank of a river bend (above a deep pool) is undercut, sediment is carried downstream, where it may be deposited in a lateral bar or riffle.

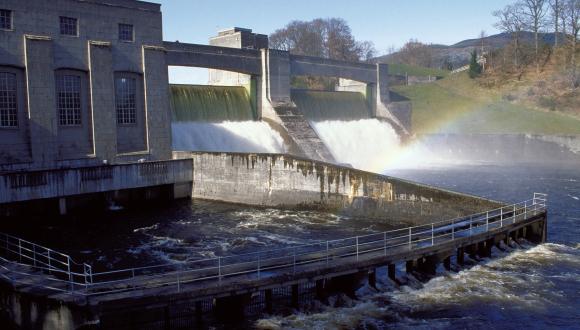

Bedrock-controlled rivers

Rock gorges and waterfalls may form where the river has been able to cut through hard rock sections.

Lowland lake deltas

In lowland lochs, lake deltas are often built of sands, silts and clays (muds).

Rivers flowing into the sea

Estuaries and firths

These mud, silt and sand bed rivers move sediment out to the sea through both river flow and tidal current processes. The stages of the tide determine the direction and strength of water flow, and the ability of the water to move and deposit sediment.

Estuaries and firths can flood due to tidal and storm surges (determined by tidal stage, wind direction and strength) and inland flooding. The biggest floods occur when these factors coincide.

Saltmarshes that form along natural shorelines help to regulate floodwater and capture flood-borne nutrients.