Developing with Nature guidance

Guidance on securing positive effects for biodiversity from local development to support NPF4 policy 3(c)

The following Guidance has been published in support of policy 3(c) of National Planning Framework 4. An illustrated version of this guidance is currently in preparation, and will be published on this page when finalised.

1. Introduction

The Planning system, development and nature

- The world is facing the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. These interlinked challenges need to be addressed together, requiring enormous effort globally, nationally and locally.

- In Scotland, biodiversity has declined dramatically in recent decades, with strong and bold action now required to bring about the transformative change needed to halt this loss (see Box 1). The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 2019 global assessment identified land / sea use change, in part driven by development, as one of the five main drivers of nature loss (the others being direct exploitation, pollution, climate change and invasive alien species). It is important that all of society’s activities, including development, not only avoids damage to and loss of nature, but helps to restore it.

Box 1: Scotland’s declining biodiversity

Scotland’s biodiversity is under huge strain from a number of pressures. These include agricultural management, climate change, hydrological change and invasive non-native species. Along with these, development and urbanisation has resulted in a loss of valuable wildlife sites, disturbance to species and the fragmentation of habitats. While immediate impacts can be all too obvious, this also severely impacts species dispersal and mortality, restricts genetic mixing, increases inbreeding and as a result increases species isolation and the chance of local populations going extinct. This is of increasing concern as the ability of species to adapt and disperse in response to climate change becomes more restricted.

The most up to date data show that the abundance and distribution of Scotland’s species has on average declined over recent decades. Most measures indicate that this decline has continued in the last decade, with no let-up in the net loss of nature in Scotland.

- 24% decline in average species abundance since 1994

- 14% decline in average species distribution since 1970

- 49% of species have decreased in abundance since 1970

- 11% of 6,413 species found in Scotland are threatened with extinction from Great Britain

Source: The State of Nature Scotland 2019, The State of Nature Partnership

3. The 2022 UN Convention on Biological Biodiversity Conference of the Parties (COP15) addressed the role of planning through Target 12 of the new Global Biodiversity Framework. This incorporates the 2020 Edinburgh Declaration and encourages local government to step up action. Scotland’s draft Biodiversity strategy to 2045: tackling the nature emergency identifies 26 of the most urgent actions to achieve nature positive by 2030. These include ensuring positive effects on biodiversity under the National Planning framework are delivered, with development proposals contributing to the enhancement of biodiversity, restoring degraded habitats and building and strengthening nature networks.

4. Planning therefore has an important role in helping to address our damage to nature. This requires a new approach, one that halts and reverses biodiversity loss and better connects habitats and biodiversity rich areas. Simply minimising damage and replacing lost habitats and species will not address the decline in Scotland’s biodiversity.

5. The Fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4) therefore places climate and nature at the centre of the planning system and includes a cross-cutting outcome to improve biodiversity. Policy 1 gives significant weight to the global climate and nature crises to ensure that they are recognised as a priority in all plans and decisions. Policy 3 plays a critical role in ensuring that development will secure positive effects for biodiversity. It rebalances the planning system in favour of conserving, restoring and enhancing biodiversity and promotes nature-based solutions, benefiting people and nature. This policy intends to protect biodiversity, reverse biodiversity loss, deliver positive effects from development and strengthen nature networks. Further information on relevant strategies and policies can be found on page 9 of NPF4.

6. Well-designed development integrating nature-based solutions provides multiple benefits. As well as addressing the causes of climate change and supporting biodiversity, they benefit people and enhance our places in keeping with the six qualities of successful places (see Box 2). Wider environmental benefits include better water and temperature regulation, improving air and water quality, enhancing carbon storage, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and absorbing noise. These all contribute to better places that promote wellbeing, provide for healthier lifestyles, enable people to connect with nature, support greater attachment to place and can enhance the economic value attributed to a development.

Box 2: Supporting Liveable Places

Healthy: supporting the prioritisation of women’s safety and improving physical and mental health.

Pleasant: supporting attractive natural and built spaces.

Connected: supporting well connected networks that make moving around easy and reduce car dependency

Distinctive: supporting attention to detail of local architectural styles and natural landscapes to be interpreted, literally or creatively, into designs to reinforce identity.

Sustainable: supporting the efficient use of resources that will allow people to live, play, work and stay in their area, ensuring climate resilience, and integrating nature positive, biodiversity solutions.

Adaptable: supporting commitment to investing in the long-term value of buildings, streets and spaces by allowing for flexibility so that they can be changed quickly to accommodate different uses as well as maintained over time.

NPF4 Annex D provides further detail on the considerations required when designing for these six qualities.

Source: National Planning Framework 4, The Scottish Government (2023)

Who is this Guidance for?

7. This Guidance is for anyone making or considering a planning application under Scotland’s Planning Acts for certain local developments. These are those not subject to an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA is required for any application likely to have significant effects on the environment), nor a householder development or open water farmed finfish or shellfish development (policy 32(e) refers). ‘Local development’ is any development that is identified as neither a ‘national development’ nor a ‘major development’. Examples include small developments of new housing, industrial and retail buildings, amongst others. Further information on ‘local’, ‘major’ and ‘national development’ can be found in Circular 5 2009: Hierarchy of Developments.

8. Most local development applications will not engage ecological expertise, or be guided by a masterplan or design framework setting out specific biodiversity requirements (although relevant local development plan policies will apply). The information in this Guidance is therefore intended to provide an understanding of what common measures to enhance biodiversity are feasible to the non-specialist. Where development interacts with less common, valued, more complex and / or extensive areas of biodiversity interest, expert ecological input and more specific guidance is very likely to be required. Some sources for this are included in Section 3.

9. Measures should be proportionate to the nature and scale of development proposed. It follows that, for larger scale or complex forms of local development, more detailed consideration and more ambitious measures than are set out in this Guidance are likely to be required. Many of the measures set out in this Guidance can also be incorporated in and around existing development, and where the opportunity to ‘retrofit’ these exists, this is encouraged.

The application and scope of this Guidance

10. NPF4 sets out new requirements for the planning system to take greater account of nature in the decisions it makes. In particular policy 3 ‘Biodiversity’ sets out policy principles in response to the nature crisis, and 3(c) states that proposals for local development will include appropriate measures to conserve, restore and enhance biodiversity in accordance with national and local guidance. Such measures should be proportionate to the nature and scale of development. This guidance describes a number of these biodiversity measures, and the considerations that should be taken in to account when determining whether they are appropriate for the particular development.

11. This Guidance has been prepared to support application of NPF4 policy 3(c). It should be the starting point for applying policy 3(c), but will not cover all circumstances. This is non-statutory guidance and not part of the development plan. However, applicants and Planning Authorities are expected to give this Guidance due consideration through the site selection, design and planning application process. It should be considered alongside the local development plan and any local guidance the Planning Authority may have prepared.

12. Policy 3(c) does not apply to householder development (development within the curtilage of a single dwelling that requires a planning application, such as an extension or conservatory), nor open water farmed finfish or shellfish development. Nonetheless, small-scale householder development can easily incorporate features that will be of benefit to nature and applicants are encouraged to apply the principles and measures set out in this Guidance wherever possible. Such applications will in any case be subject to all other relevant NPF4 policies, and where such features are designed-in, this may lead to a smoother passage through the planning system.

13. Section 1, this introduction, set out the purpose and scope of the Guidance, who it is for, and outlines the contents to follow.

14. Section 2 provides guidance on selecting those measures most appropriate to a site and the development proposed, the information that applicants can usefully include to detail how the biodiversity enhancements will be delivered, and deciding on the scale of enhancement to be delivered.

15. Section 3 identifies some of the key online sources and organisations providing further information on measures for enhancing biodiversity.

16. Annex A describes 24 measures that development can incorporate to enhance biodiversity and identifies where further detailed information on the design, construction, management and maintenance of each measure can be found.

17. Annex B provides a list of invasive non-native plant species that should be excluded from use in planting schemes seeking to enhance biodiversity.

18. Annex C provides a suggested template for presenting information on enhancing biodiversity of a standard appropriate for more significant local development.

19. The focus of this Guidance is on measures enhancing biodiversity, which can also bring wider benefits and improve our places and the lives of those working and living there. This Guidance does not provide an exhaustive list of measures, and other innovative or bespoke measures may be required for some developments - in particular, for larger scale or more complex local developments, additional measures may be needed to enhance biodiversity. It does cover many common actions that are widely applicable across a range of settings that can be included in many types of development without undue difficulty.

20. This Guidance does not include more specialist measures applicable to rarer species. Where the opportunity arises to support these species, expert ecological advice will be required. Some of the measures included here will support some species that enjoy special protection (for example, bats), which places certain legal requirements on anyone potentially disturbing them to ensure their safeguarding. Understanding and conforming to legal requirements is essential for any development likely to interact with protected species, whether already present on site or likely to be attracted by the biodiversity measures set out here. Further information on what species are protected and what this means can be found on the NatureScot website.

21. NatureScot welcomes feedback on this Guidance from those applying it to local development applications, as experience of its use is gained. Please send any comments to [email protected].

2. Taking account of nature planning

Ensuring a nature rich approach

22. With early consideration of the opportunities to provide for nature and appropriate siting and design, even the smallest of developments and sites will be able to support and provide benefits for biodiversity. Each of the component parts that a development commonly comprises should be considered for their potential to enhance biodiversity, including any nature-based solutions that will be implemented.

Buildings and structures: Consider the opportunities for incorporating features within, or on, built structures, and the choice of building materials that can support biodiversity. Many species are able to utilise artificial structures whose features reflect their natural habitat. As well as furnishing homes for many species they can also provide a substrate that supports food sources and cover.

Borders, boundaries and buffers dividing the site: Consider the on- and off-site connectivity of linear features, including living hedgerows, verges and buffer strips, and built dykes, walls and fences. Linking together areas of habitat, or adding to wider nature networks by the provision of good quality linear features, provides food, shelter and safe corridors for movement across a site and dispersal beyond it where boundaries are permeable to species. Incorporating connectivity and permeability in a development’s design will augment the benefit of individual measures.

Rain and surface water management: Consider how water can be used to support biodiversity, through utilising existing sources, minimising impermeable surfaces and soil sealing, and ensuring any sustainable drainage system (SuDS) is truly multi-functional. Measures to collect, infiltrate and convey water at source and across the development site should be designed and managed to provide food, shelter, homes and safe corridors for wildlife.

Greenspace and gardens: Consider the opportunities for enhancing biodiversity in the amenity and public spaces adjoining built development (including transport provision), and creating biodiverse and people-friendly green spaces. The layout, structure, choice of species and management regime of these areas will have a strong influence on the opportunities provided for nesting, shelter, food and movement, and their likely success.

23. To ensure positive effects for biodiversity are secured in practice, a number of commonly used and widely applied ‘rules’ should be followed, to ensure nature is an integral part of the development.

Apply the mitigation hierarchy

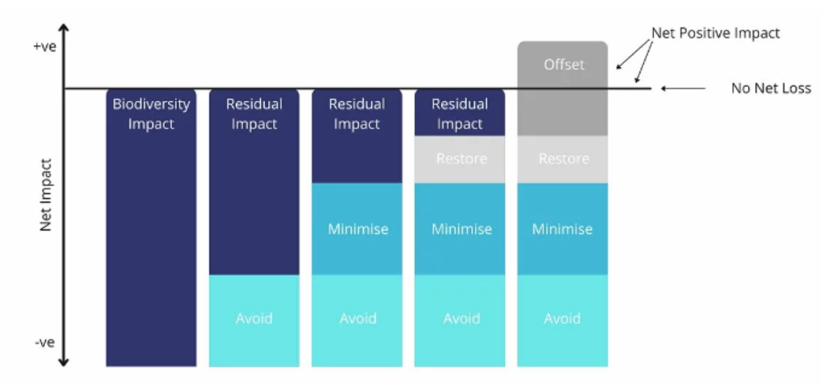

24. Delivering positive effects first requires all detrimental impacts on biodiversity to be mitigated to the greatest degree possible, in accordance with the mitigation hierarchy (see Box 3). The hierarchy sets out the order in which the impacts of development should be addressed:

- first, avoid - by removing the impact at the outset wherever feasible;

- second, minimise – by reducing the impacts that are unavoidable;

- third, restore – by repairing and enhancing damaged habitats and disturbed species; and

- fourth, offset – by creating new habitat, preferably on-site but can be off-site, to compensate for any residual impact that remains.

Box 3: The mitigation hierarchy

The mitigation hierarchy indicates the order in which the impacts of development should be considered and addressed, when residual impacts remain from actions higher in the hierarchy. Depending on the nature of the development and its impact, net positive may be achieved from restorative actions, or also require offsetting.

25. Securing positive effects is additional to the measures already expected to be applied to mitigate a development’s impact. However, many of the measures identified in this Guidance can be applied to both mitigate impacts on, and to enhance, biodiversity. It is only when these measures result in biodiversity being left in a better state than before development that nature is enhanced and positive effects for biodiversity have been secured.

26. Offsetting for residual impacts should seek to replace with ‘like for like or better’, taking into account the distinctiveness and functionality of the lost habitat and species, and any identified priorities for biodiversity action. The ease and cost of compensatory measures should not be the determining factor. Offsetting cannot compensate for the loss of irreplaceable habitats, and actions to deliver positive effects must accord with all nature conservation legislation.

Consider biodiversity from the outset

27. The opportunities for safeguarding and enhancing biodiversity should be considered from the very earliest stages of formulating a development proposal, as a core part of the siting and design process to avoid it being ‘bolted on’ at the end. For more significant local development, widely applied design processes such as masterplanning provide a clear and robust framework for including biodiversity. This requires an understanding of site conditions (such as soil properties, aspect, shelter and drainage), existing habitats and species, and how they vary across the site. In nearly all circumstances, retaining and enhancing existing nature is of greater benefit than seeking to substitute with new habitats and species that will require time to become established, with some uncertainty as to their success.

28. Early consideration helps avoid unacceptable impacts on valued habitats and should minimise other impacts, and allow the full range of opportunities for delivering the best outcome for biodiversity to be considered. This can lead to improvements in a development’s design, capturing the benefits provided by mature habitats and better integrating biodiversity measures and their management needs at the outset (and avoid the cost of later ‘retrofit’). Early consideration of existing soil and habitat resources can also help reduce waste and the need to import new material for the reinstatement and improvement of biodiversity.

Provide synergies and connectivity for nature

29. Individual measures should not be considered in isolation, but as an important component of their wider setting. Most measures will be dependent for their success on the availability of suitable foraging or shelter being available, and many will complement the habitats and species that other measures provide. Existing, well-established habitat, either retained on site or found in adjacent areas, is of particular value as new habitat requires time to mature.

30. Every opportunity should be taken to safeguard, enhance and extend functional connectivity between the development itself and adjoining areas of habitat, ensuring ‘permeable boundaries’ are incorporated. Hedgerows, woodland and scrub, meadows and verges, street and feature trees, and ponds and wetlands can all provide stepping stones and corridors that aid the movement and dispersion of species, address fragmentation and avoid creating isolated pockets of nature. Ensuring suitable habitat connectivity for wildlife across the landscape is important for most species, particularly where cover avoids predation, or protects from exposure to the elements. Improved connectivity will help build and strengthen the resilience of nature networks, which may be specifically identified in local action plans and strategies, or more generally encouraged by specific species initiatives.

Integrate nature to deliver multiple benefits

31. While enhancing biodiversity is the primary role of delivering positive effects, this will also improve the stock of natural capital and contribute to the provision of ecosystem services more generally. Development should consider opportunities to maximise these, and deliver multiple benefits for both people and nature.

32. Nature-based solutions (NbS), such as sustainable drainage systems (SuDS), green roofs and walls, street trees and green space, are increasingly being utilised in development. These provide a cost effective and climate-resilient solution to issues such as extreme temperatures, high energy use, noise, water quality and quantity, and poor amenity. Not all NbS automatically maximise their biodiversity potential, but integrating biodiversity rich NbS into the design can directly enhance nature, providing suitable nesting, foraging and shelter habitat. They can also have a wider positive impact on nature, for example through enabling suitable temperatures for wildlife to be maintained, limiting disturbance by reducing noise pollution, and reducing pollutant run-off.

Prioritise on-site enhancement before off-site delivery

33. Wherever possible measures for enhancing biodiversity should be provided within the development site, where the loss of, or damage to, biodiversity is taking place. This is an equitable approach, that seeks to ensure that areas of development do not become ‘nature poor’ as a consequence of the loss of habitat reducing habitat connectivity and species range, to the detriment of both people and biodiversity. For most local development, enhancement will be delivered on-site.

34. Off-site offsetting is generally considered as the ‘last resort’ in the mitigation hierarchy. But where adequate provision of positive effects cannot be delivered on-site, or significantly better outcomes for biodiversity enhancement can be achieved elsewhere, off-site provision may be justified alongside on-site. This may entail enhancing existing habitat or creating new, strengthening the connectivity of nature networks, delivering larger landscape-scale benefits, and enhancing the resilience of key habitats and species identified as a priority for action. Potential off-site projects may be identified in the Local Biodiversity Action Plan (LBAP) or other strategies, and by local or national environmental NGOs.

35. Off-site offsetting, when appropriate, should be carried out as close as possible to the development site, to reduce the loss of biodiversity in the local area. The deficit in on-site enhancement should be ‘over-compensated’ for by delivering a greater level of off-site enhancement, the scale of which should increase the further from the development site that off-site measures are delivered. Where off-site offsetting itself detrimentally impacts the off-site’s existing biodiversity, this should also be accounted for in the scale of enhancement delivered. Off-site offsetting should be clearly evidenced and secured for the long term. Where planning conditions or obligations are to be used, the relevant tests set out in the appropriate Circulars will need to be met.

Take a placed-based and inclusive approach

36. For development with nature to work, an understanding is required of the main natural assets of the site and its surroundings (particularly the ability of soils to support proposed species and habitats), the opportunities they provide for enhancement, and how the development will be used. Consideration should be given to any opportunities to contribute towards restoring or enhancing any habitats and species identified as national, strategic or local priorities. The local environmental records centre or wildlife group may be able to advise on appropriate habitat and species choice.

37. Local stakeholders can apply their knowledge to identify broader benefits of the measures to both people and place. At the same time this can raise understanding and encourage involvement in, and protection of, nature. Schools can become involved in the management and monitoring of nature, contributing to delivery of the curriculum and any award schemes.

Ensure long term enhancement is secured

38. Nature is uncertain and not fully within our control. Securing positive effects for biodiversity inevitably entails a degree of risk as to whether the intended outcomes will be delivered in practice. Incorporating a contingency to compensate for this risk, designing for resilience and taking an adaptive approach that can respond to nature’s uncertainty is required.

39. Even after the careful implementation of appropriate measures, on-going management and future monitoring should be secured to ensure the intended enhancement is achieved in practice. This is similar to the requirement for new or enhanced blue / green infrastructure to provide effective management and maintenance plans and funding arrangements under the blue and green infrastructure policy 20(e). Addressing the nature crisis requires measures to be retained for the long term (preferably in perpetuity), in order to deliver a lasting legacy. How this will be done should be set out in the application.

Selecting the measures that are appropriate

40. When selecting biodiversity measures there are ten guiding factors to consider, to ensure the opportunities for enhancement can achieve the greatest benefit for nature. These factors are either of an ecological or practical character.

Ecological Considerations

Locally and ecologically relevant

Consider the measure(s) ‘fit’ with existing nature, such as how it complements, substitutes for or restores lost, degraded or disturbed habitats and species, particularly those considered a priority for action (for example those identified in a LBAP or similar strategy – see paragraph 42). Selected measures should draw on the nature found on the site and its surroundings, taking in to account their resilience to future climate change. Encouraging native species present in the immediate area will help strengthen local biodiversity, and enhancing these will usually have the greatest chance of success and deliver the most benefits.

Careful species choice

Consider whether the measures’ species are appropriate and able to thrive under local conditions, ensuring that it will not benefit one species with unintended consequences for others. Species that are known to be invasive and can come to dominate and overtake valuable biodiverse native habitat should not be used (see Annex B). Preference should be given to:

- using native species (of local provenance) where these are appropriate and available

- employing nationally (Scottish BAP) and locally (LBAP) listed priority species and habitats wherever feasible

- favour rarer species where appropriate

Connected and permeable for nature

Consider how the measures take account of and strengthen connectivity (within the site and to wider networks), with habitats and permeable boundaries allowing safe movement for foraging and dispersal. This is particularly important for larger local development, and where development more widely is resulting in the fragmentation of habitats, and as a consequence remaining pockets struggle to maintain viable populations and do not benefit from dispersal from other areas. LBAPs, regional habitat networks, local pollinator corridors, greenway and ‘B-lines’ initiatives may identify important opportunities.

Space for adaptation

Consider how well the measure(s) will work in response to the modified habitats and natural processes following development. Provide space to allow nature the opportunity to expand and colonise new areas naturally.

Allow for synergies

Consider the opportunities for individual measures to complement and reinforce one another, and for nature outwith the development to support its introduction (such as existing foraging habitat being present for the species provided with shelter). None of the measures should be considered in isolation, but as part of the wider whole.

Scale of provision

Consider the scale of the measure(s) to be delivered is suitable for ecological reasons. Some measures work best when provided in groups (for example a cluster of swift or sparrow boxes), or are of a minimum size (for example a grassland area).

Practical Considerations

People and nature together

Consider the compatibility of the measure(s) with the future use of the development to ensure it reflects the needs of both people and nature, avoiding potential conflict. Development and its associated activity can result in disruption and disturbance to nature, but good planning and design can provide multi-functional buildings and spaces for both people and nature. Incorporating measures in a way that respect’s nature’s needs and at the same time provides opportunities for people to connect with nature will promote long term community stewardship of them.

Long term retention and management

Consider the management needs of the measure(s) and how this will be delivered in the future. This includes practical requirements such as access, as well as legal and resource needs. Certainty of retention and long term management is essential if the enhancement is to endure and achieve the long term benefit for nature that is required.

Local community involvement

Consider the opportunity for the local community to get involved with the measure(s), particularly for larger scales of development. Where measures are part of the public realm, wider engagement and involvement in its stewardship can promote awareness, understanding and community pride in the nature to be found.

Multiple benefits

Consider the opportunity that the measure(s) provide for delivering wider benefits for the environment, people and the development itself. This can include supporting climate adaptation (better water and temperature regulation), improving air and water quality, enhancing carbon storage, absorbing noise and improving health and wellbeing, which will result in delivering better places.

41. The most suitable and locally appropriate biodiversity measures will be dependent on the location, site and type of development seeking approval. Some will be more or less suitable depending on the scale of the development proposed. The cost of delivering and managing individual measures should not be the determining consideration.

42. Consideration should also be given to established guidance on safeguarding and enhancing biodiversity in the local area. These can identify habitat and species priorities for action, and opportunities for delivering wider benefit, such as contributing to wider nature networks. Available, up to date guidance varies across Scotland, and the Local Authority’s planning portal is a good place to search for many of the most common sources, including the following.

- The Local Development Plan (LDP) can identify opportunities to improve connectivity, support species, establish new or extend habitats, or restore and enhance biodiversity across the plan area. For more significant development sites allocated in the LDP there may be a site brief, design framework or masterplan that identifies particular opportunities to enhance biodiversity.

- The Planning Authority may have supporting documents that identify opportunities to enhance biodiversity at the larger spatial scale. Relevant information may be found in an Open Space Strategy, Green Network Strategy, Forestry and Woodland Strategy or similar. The Regional Spatial Strategy may identify opportunities to contribute to habitat enhancement and networks beyond the local authority scale. Development in the Central Scotland Green Network area can interrogate the Habitat Connectivity Map to identify opportunities for connecting habitats.

- The Local Biodiversity Action Plan (LBAP), which identifies the priority species and habitats for action in its area, is a key source of information on local nature. This includes Local Nature Conservation Sites (LNCS) and Local Nature Reserves (LNRs), enabling consideration of opportunities to complement these sites and avoid any unintended impacts. NatureScot’s website includes links to most of Scotland’s LBAPs.

- Many areas have a local environmental or biological records centre that may be able to provide information on the habitats and species in the area.

- Local groups of many of the wildlife organisations listed in Section 3 can be found across Scotland. Their knowledge of local wildlife can inform consideration of the likelihood of successfully enhancing individual species and habitats.

43. Where this supporting information is limited or not available, separate ecological expertise may need to be accessed. This will be particularly important for local development that interacts with less common, valued, more complex and / or extensive areas of biodiversity interest.

44. Delivering many of the biodiversity measures, particularly for the larger scales of local development, can benefit from engagement with the local community and wildlife groups. Opportunities include:

- drawing on the knowledge of local groups when considering the suitability of the measures to be installed, and any potential complementary measures;

- working with local groups on constructing or installing the measures, particularly those incorporated in the public realm;

- involving local groups in the monitoring and maintenance of the measures; and

- promoting awareness and understanding of the measures incorporated in the development and the benefits they provide for biodiversity (for example through interpretation panels or the provision of wildlife information packs to new homeowners).

Information to include in the Planning Application

45. Applicants are strongly encouraged to discuss the biodiversity measures proposed for incorporating in the development at an early stage with the planning authority. The information provided in the planning application will need to provide confidence that the development includes appropriate measures to conserve, restore and enhance biodiversity, in proportion to its nature and scale, as required by NPF4 policy 3(c). These measures should leave nature in a better state than before development. Where the Planning Authority has set out its own local guidance on the information required, this should also be taken into account.

46. Planning applications should contain a statement setting out the measure(s) to be included, with an accompanying plan(s). The plan(s) should clearly show existing and retained biodiversity interest, and the enhancements proposed, indicating how these measures are expected to conserve, restore, and enhance biodiversity. If measures will be incorporated into a building or other structure, appropriate elevation drawing(s) should be included. Where a design statement has been prepared, either as a requirement or voluntarily, the information could be incorporated into this (Planning Advice Note 68: Design Statements provides advice on their purpose and content).

47. The statement (or its alternative) should succinctly set out:

- the site’s current biodiversity interest (against which the scale and nature of the enhancement required to achieve positive effects is considered), the impact of the development on this, the mitigation proposed and residual impact

- how the proposed development has taken into account the opportunities for enhancing existing biodiversity on site, including the consideration given to surrounding habitats and strengthening connectivity

- the biodiversity measures delivering enhancement that will be incorporated in the development, and the reasons for their selection (noting the support, if any, provided for these by the LDP, LBAP and other strategies)

- where relevant, any future maintenance and management to be undertaken and how the long term retention of the measure(s) will be secured, including any monitoring and reporting that will be undertaken

48. If more detail is contained in other documents and plans these should be described and listed, but the statement should contain enough information to allow a clear overview to be taken of what and how much enhancement will be delivered. It should be clear from the information provided that the measures proposed are additional to what is expected to mitigate the development’s impact in line with established good practice and compliance with other policies, and enable the planning authority to be confident that appropriate measures to conserve, restore and enhance biodiversity will be delivered and secured.

49. The level of information to be provided will vary with the site, scale and complexity of the development, and the type of biodiversity measures to be incorporated.

- For the smallest developments (such as a single house), a simple plan and elevation drawing with an accompanying statement describing the proposed measure(s) should be provided.

- For larger developments (for example with multiple buildings, access arrangements and greenspace), a detailed landscape plan and / or elevation drawing with an accompanying statement describing the measure(s), their relationship with species and habitats on and surrounding the site, and mechanism by which their retention and long term management will be secured should be provided.

- For developments seeking outline permission, or that will be subject to phased development, the overarching strategy for enhancing biodiversity should be clearly set out. This should consider ‘front-loading’ enhancements in case later phases are delayed, and minimise any dependency on future phases to deliver the enhancement required.

- For developments that have prepared a specific ecological report, such as a Preliminary Ecological Appraisal (PEA) or Ecological Impact Assessment (EcIA), these studies should have addressed the opportunities for enhancing biodiversity on the site. The plan, drawing and accompanying statement should set out how the identified opportunities will be delivered to their maximum potential. Where opportunities identified in the PEA or EcIA are not incorporated in the development, the reasons for this should be clearly set out.

50. The statement, relevant plan(s) and elevation drawing(s) will form part of the approved application.

Determining the scale of enhancement to be delivered by development

51. NPF4 policy 3(c) requires proposals for local development to include appropriate measures in accordance with national and local guidance, proportionate to the nature and scale of development. Based on the measures identified in the proposal, it will be for the Planning Authority to decide whether these are appropriate in the circumstances of a particular application, and proportionate. The selection and design of measures will be a matter of judgement based on the circumstances of the individual case, but should take into account a number of considerations.

- The location of the development site and the opportunities it provides for enhancing biodiversity: The setting of development sites varies considerably. Peri-urban and rural locations should allow a broader and greater set of measures to be considered than a small, densely developed, urban site. The greater the opportunity for nature, the higher the expectation should be of the development realising this.

- The character and scale of the development: The type of development, its form and elements it contains will influence what, and how many, measures can be incorporated. Development including greenspace provides a wide range of opportunities, but buildings and structures should also be considered carefully for the many opportunities they provide. Even where the choice of measures may be limited, many can be replicated across a development which can increase the likelihood of their success. Many of the measures can be incorporated into the smallest of developments, and larger developments will be expected to deliver more and at scale.

- The requirements and cost of maintenance and future management of the measures proposed: The ease and cost of delivering and managing individual measures is a relevant consideration, but should not be the determining factor when deciding the scale of enhancement to be delivered.

- The distinctiveness and scale of the biodiversity damaged or lost: Cognisance should be taken of the biodiversity damaged or lost as a consequence of the development, to be confident in delivering positive effects. This includes the habitat’s species richness, its rarity and the degree to which it supports species rarely found in other habitats. The greater these are, the greater the scale of enhancement that should be delivered by the development.

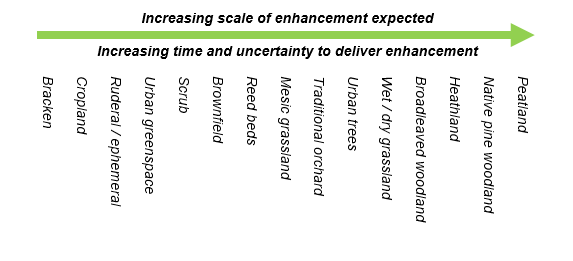

- The time required to deliver biodiversity benefits and any risks or uncertainty in achieving this: Some measures require time to mature to fully enhance biodiversity, or are dependent on future successful management, or there is a degree of uncertainty as to their likely success. A balance needs to be found between delivering enhancements today with confidence, or at a later date with more uncertainty.

Box 4: Indicative relationship between some broad habitat types and the likely time required and associated risk in replacing their biodiversity value

The longer the time-scale and / or the greater the uncertainty to delivering positive effects, the larger the scale of enhancement that should be required to provide confidence that positive effects will be delivered

3. Key sources of further information

52. Most local development applications applying this Guidance will not have access to dedicated ecological expertise. But a wealth of information and advice on development and nature can be found on the NatureScot website and those of various wildlife organisations. These complement the further information identified under each measure in Annex A. We recommend exploring the following sources to learn more about the opportunities to enhance biodiversity, and the individual species and habitats that will benefit.

53. For development interacting with less common, valued, more complex and / or extensive areas of biodiversity interest, which falls beyond the scope of this Guidance, the appropriate professional bodies can advise on accessing relevant expertise and specialist guidance. These include:

- Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM)

- Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA)

- Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management (CIWEM)

General sources on enhancement for biodiversity

- Association of Local Environmental Records Centres provides contact details of local centres across Scotland. As well as a source of local habitat and species data, many include resources and guidance relevant to development.

- The National Biodiversity Network’s NBN Atlas Scotland provides an online portal to Scotland’s largest collection of freely available biodiversity data.

- Partnership for Biodiversity in Planning provides an online Wildlife Assessment Check toolkit for identifying whether small to medium scale development requires expert ecological advice, and guidance on enhancement for species.

- CIRIA’s Big Biodiversity Challenge is an award promoting biodiversity enhancements on construction sites, new development and existing buildings, with examples of what can be done.

- Three general publications provide an overview and case studies of many of the biodiversity measures discussed in this Guidance.

- National House-Building Council’s (NHBC) Biodiversity in New Housing Developments: creating wildlife-friendly communities (2021)

- The UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology’s Biodiversity Toolkit for Housing Providers (2020)

- The Wildlife Trusts’ Homes for people and wildlife - How to build housing in a nature-friendly way (2018)

- CIEEM have published guidance on identifying the opportunities for enhancing biodiversity on a site: Biodiversity Net Gain Feasibility Report, Guidelines for Preliminary Ecological Appraisal, and Guidelines for Ecological Impact Assessment in the UK and Ireland.

- Scottish Government’s Green infrastructure: design and placemaking guidance sets out some key design issues and techniques for incorporating green infrastructure into development.

Organisations

- Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust

- Barn Owl Trust

- Bat Conservation Trust

- British Hedgehog Preservation Society

- British Herpetological Society

- British Trust for Ornithology (Garden BirdWatch project)

- Buglife

- Bumblebee Conservation Trust

- Butterfly Conservation

- Fisheries Management Scotland

- Freshwater Habitats Trust

- Froglife

- Hedgelink

- Living Roofs

- NatureScot

- People’s Trust for Endangered Species

- Plantlife

- Royal Horticultural Society (Wildlife Gardening)

- Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

- Scottish Environment Protection Agency

- Scottish Wildlife Trust

- Social Farms and Gardens

- Susdrain

- Swift Conservation

- Wild About Gardens

- Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (gardening for wetlands)

- Wildlife Gardening Forum

- Wildlife Trusts (wildlife gardening)

- Woodland Trust

Annex A: Appropriate measures to enhance biodiversity

A.1. This Annex describes 24 biodiversity measures that can be incorporated into development, grouped in to three categories: planting for nature; providing homes for nature; and managing water with nature. This is not an exhaustive list, and other innovative or bespoke measures may be required for some developments. Each measure adheres to a common format that provides the key information necessary for considering the measure’s fit and suitability for the development that is proposed. This includes:

- a short description of what the measure comprises;

- an overview of what benefits the measure provides for nature;

- the key requirements for successfully implementing the measure;

- a description of the management effort required to maintain the measure;

- other measures that the measure in question has particular synergies with or complements;

- nature notes providing general information of wider interest; and

- web links to sources of further information on delivering the measure.

A.2. These individual measures should not be considered in isolation from each other, as their benefits can readily be enhanced when they are delivered in association with other measures that they have synergies with. For example, planting the right species and enhancing habitats will afford the necessary shelter for species provided with homes, and encourage the prey species that will be a source of food. This does not always require additional space, for example when incorporating a log or leaf pile in a hedgerow, or suitable space for hibernation (known as a hibernacula) beneath a bee bank capped with wildflowers.

A.3. Individual measures should also consider their potential to improve connectivity for wildlife and enhance nature networks. This can be through incorporating linear features such as hedgerows or wild flower verges for pollinators, and providing ‘stepping stones’ of habitat that enable movement. Consideration needs to be given to nature both within and outwith the development site, and avoiding potential conflicts such as encouraging wildlife to frequent busy roads.

Planting for Nature

A.4. Plants, shrubs and trees provide food, shelter and homes for many species. All planting, whatever their size, should be designed and managed to enhance biodiversity where possible. This includes incorporating edge and structural diversity, and species variety (selected to suit the soil, topography and drainage properties found across the site). To ensure soils remain healthy and support plants well in to the future, best practice in the sustainable handling, storage, use and management of soils (in particular topsoil) should be followed. This will avoid compaction, contamination and drying out.

A.5. Both large landscaping schemes and small areas of ground can be planted to attract insects and pollinators, providing an important food source for species using buildings and other structures, which themselves can provide a substrate for plants when incorporating living roofs and green walls.

A.6. The use of native species in preference to non-natives can have significant benefits for biodiversity, as they usually provide a home or food source for a greater diversity of insects, fungi and birds than non-natives and avoid potential issues with invasives. Native species within their natural range and appropriate to the site conditions, that compliment those found locally, should be selected. These should be grown from local sources (of local provenance) where possible, to reduce the risk of introducing pests and disease. Local Biodiversity Action Plans (LBAPs), the NBN Atlas Scotland, Atlas of the British and Irish Flora, local environment record centres and local wild life groups are key sources of information on what native species are appropriate to an area.

A.7. Non-native plants are a mainstay of many amenity plantings, providing greater variety, structure and seasonal colours. With careful species choice they can be of great benefit to wildlife, providing nectar for pollinators, habitat for insects and food and shelter for birds. The plants should, where possible, be locally grown. However the law (set out in the Non-native species code of practice), bans the planting of most non-native species “in the wild” (areas such as road verges, hedgerows, grasslands, woodlands and river banks), or permitting them to spread into these areas. Non-natives, other than those trees and plants on an exemption list that can be planted anywhere, can only be planted in areas designated as “non-wild” (such as private gardens, amenity greenspace, public parks and gardens, civic and play space).

A.8. As one of the five major threats to biodiversity the avoidance of invasive non-native species (INNS) in planting schemes is essential. While only a small proportion of non-native plants have the potential to become invasive, they can result in significant harm to biodiversity and a great cost to the economy. Invasive species such as ants and flatworms can also ‘hitch-hike’ on new plants, their containers and in soil.

A.9. Annex B provides a list of plant species that are either banned by law, or commonly considered to be invasive and should be avoided. However there are less-harmful alternatives to many of these, such as those set out in the Gardening without harmful invasive plants guide. Avoidance is essential where INNS may spread from the “non-wild” to “the wild”, particularly if the area is of recognised interest such as a Local Nature Conservation Site, Local or National Nature Reserve.

A.10. INNS of plants may already be present on site or spreading from adjacent land. These should be removed and disposed of appropriately, to enhance the site’s biodiversity. Landowners have a legal responsibility to prevent further spread and damage to surrounding habitats. Further information on invasive plants can be found on the NatureScot website.

A.11. Similarly, the condition of any imported soil required for planting needs to be checked for potential introductions. It should be locally sourced and avoid peat and other carbon-rich soils. Future management needs should be considered from the outset, and the use of herbicides and pesticides discouraged. Where their use is justified, planting can be used to create a ‘buffer strip’, separating different uses and activities on the site and providing some protection for sensitive areas.

Measure 1: Plants for Pollinators

Careful selection of plant species to support wildlife is one of the simplest changes that can be made for biodiversity. Gardens and landscaped areas are provided in many developments, and planters can be provided in hard landscaped spaces. Climbing plants can grow up shrubs and trees, or use walls and structures for support, providing additional niches for wildlife by allowing plants and animals to utilise vertical space.

There does not have to be a trade-off between attractive, functioning gardens and landscaped grounds, and benefitting biodiversity. We have a huge variety of native species that are often long flowering. With careful species selection not only does this create attractive spaces, but these species often require less maintenance and have a higher level of survival than non-natives.

Benefits to Nature

The plants in themselves will enhance biodiversity, but the biggest group of species to benefit will be the pollinators (that the plants are themselves dependent upon). Plants can support a diverse group of insects, including their larval stage (when they feed on the plant’s roots or leaves), as well as several mammal and bird species that predate on them. Native plants usually support the most species, and the larger the variety of plant species the more pollinator species are likely to benefit from the range of different shaped and sized flowers.

Most plants from bulbs are early flowering and can be an important resource for early season pollinators, particularly those that have come out of hibernation. Spring flowering trees and shrubs are vital nectar and pollen sources for pollinators in early spring, and late flowering species and those providing edible seeds and berries are crucial at the end of the year.

Ensuring habitat connectivity can be of particular benefit to pollinators and their predators as fragmentation is a leading cause of decline, which is accentuated by climate change. Areas identified for planting should consider how wildlife can use them to move across and beyond the site.

Other benefits of pollinator planting can include providing shade and cooling, water control, carbon storage, crop pollination and pest control, and recreational use and well-being.

Key Requirements

Any scale of development can incorporate planting for pollinators, from the use of small planters and containers, pocket and large gardens, to extensive landscaped grounds. Plants should be selected that are suited to the location and the site’s soil and environmental conditions, and intended use of the area.

Selected species should not be potentially invasive native species, particularly when planted near to vulnerable habitats, or invasive non-native species (see Annex B). A diverse species choice should consider the time of year and for how long the plants are flowering (to provide for pollinators throughout the year), the opportunities they provide for shelter (especially all year round shelter), the seed, fruit, pollen and nectar source they provide, and encourage diversity.

Bulbs can be planted and provide a resource in areas where other plants and trees cast too much shade later in the year. Areas of amenity grassland can be planted with early flowering bulbs that can be cut once the leaves arising from the bulbs have died back. Bulbs can also be planted into some meadow areas where they will not out-compete the meadow species or become invasive.

Future Management

Plants after planting may require some fertilisation and watering until they are established. Future management will depend on the species planted, with some needing no or little on-going effort while others require regular cutting back, pruning, watering, mulching and protecting to maintain them in good condition. Plants should be monitored to ensure they have established and are in good health, and management adapted to their needs. Dead or dying plants should be removed and disposed of appropriately. Plants should be replaced and if a species is found to struggle a more suitable species should be considered. Replacements should be planted as soon as the planting season allows, so as not to degrade the biodiversity provision afforded.

Management should not be onerous for small areas, but for more extensive areas a simple planting and management plan may be appropriate to ensure the necessary management is undertaken in the future. The plan should include instructions on how its content will be conveyed to site factors and operators, both now and in the future.

Complementary Measures

Plants for pollinators can be incorporated into living roofs, walls and screens (measures 5 and 6), wildlife walls (measure 12), rain gardens (measure 19), and the setting of biodiverse SuDS ponds (measure 21).

Nature Notes

Different pollinators have a variety of distinct body forms that enable them to access specific flower shapes. Many pollinators (especially bees) need both pollen and nectar, requiring a variety of plants, and not all flowers provide similar resources. Some will have less nectar and pollen, while other flowers that have been bred for aesthetic characteristics (for example extra petals), can block access to pollen and nectar. These should be avoided, along with species that could have negative effects if they were to seed or sucker into surrounding habitats.

Further Information

- On making development pollinator friendly see NatureScot’s Guidance – pollinators in planning and construction guide

- On selecting plant species that are not invasive see the Non-native Species Secretariat (NNSS) guidance on Gardening without harmful invasive plants

- On the selection of plants see the Royal Horticultural Society’s Find a plant database (to produce a filtered list of native wildlife and pollinator friendly species) and the RHS plants for pollinators guide

- On plants for wildlife see the RSPB’s All about the plants guide and the North East Scotland Biodiversity Partnership’s Wildlife gardening

- On plants for bees see the Bumblebee Conservation Trust’s Gardening for bumblebees, and The Wildlife Trusts’ How to attract bumblebees to your garden and The best plants for bees and pollinators

- On plants for butterflies see Butterfly Conservation’s guides for Caterpillar food plants and Nectar plants for butterflies, and the Wildlife Trusts’ How to attract butterflies to your garden

- On plants for moths see the Wildlife Trusts’ How to attract moths and bats to your garden and the RSPB’s Grow food for moths

Measure 2: Wildflower Meadow

A wildflower meadow consists of a variety of wild grasses and wildflowers growing generally on unimproved and ungrazed land in conditions suitable for less vigorous and more easily outcompeted species. Meadows can be large, enhancing the biodiversity value of a public greenspace, or small, occupying a small corner of a garden or established as part of another measure (such as a bee bank or buffer strip to a swale). They include a range of different forms:

- Short flowering lawn – in place of the common monoculture grass lawn using seed mixes or wildflower turves favouring low growing and ground hugging species, which require less cutting than amenity grass.

- Wet meadow – in areas with damp or wet conditions that may periodically flood, meadow species can thrive so long as water flows do not improve the nutrient poor conditions.

- Hedgerow borders – seed mixes specifically for hedgerows can tolerate a degree of shading, supplementing the range of wildflowers already present when the cutting regime allows for the growth of woody species through the hedge.

- Woodland and shrub understorey – wildflower seeding or using plug plants to enhance existing ground cover, with management of the woody plants to ensure it does not become too shaded.

- Verges beside roads and paths - creating linear meadows where shading, fertile soils and small plots do not constrain.

- Pollinator meadow – using a mix favouring high nectar value species that would not naturally be together nor found within the local area, possibly including non-invasive garden species.

- Beetle banks – incorporated within the meadow these low mounds, seeded with tussock forming native grasses that are cut irregularly, provide important overwintering habitat for invertebrates, small mammals and reptiles.

Benefits to Nature

Wildflower meadows benefit a large number of species. The vegetation supports a diverse range of invertebrate species that depend on these as their food plants (for example caterpillars of moths and butterflies), and their flowers support a number of pollinator species. Small mammals (especially hedgehogs and bats), birds and other invertebrates will be supported by the seeds and fruits produced by the plants and presence of prey species. Areas of long grass allowed to die back are valuable for nesting and shelter, and areas of bare ground can be basking areas for reptiles and many invertebrates. Birds of prey, including owls, will also forage across meadows to feed on small mammals.

With appropriate management other plant species will colonise wildflower meadows over time, and these areas can become important reserves for rare plants. The larger the meadow that is created, the more functionally diverse the habitat that will be established. Meadows can also provide corridors or steppingstones that facilitate species movement across the site and beyond it. Meadows can also form important features in other habitats, for example woodland ground cover and under hedgerows, and areas of transitional and buffer habitat (such as at the edge of water, scrub or woodland).

Other benefits of wildflower meadows include water management, crop pollination and pest control, well-being and recreation.

Key Requirements

Any development site with an area of grass can establish a form of wildflower meadow, taking into account the size of the available area, surrounding habitats, soil type and local environmental conditions. For a large meadow the whole area may not suit a single seed mix, and soil and ground type should be assessed (for example, elevated soil pH and fertility levels associated with past management practices may impede meadow establishment). Minimising the loss and retaining existing grassland and open habitat mosaic should be the priority.

Where development incorporates undisturbed grassland, by starting an appropriate cutting regime existing species suppressed by past management can grow and produce seed. Where the ground has been disturbed, or covered with soil from elsewhere on the site or offsite, the seed bank may have been disturbed. If the area has been previously seeded or high performing amenity grasslands turfs laid then these can outcompete wild species, requiring the area to scarified and seeded with yellow rattle to reduce the grass dominance, or cleared.

When creating a meadow from seed or turves the species selected should be in keeping with those found within the local area, from a local source where possible, and avoiding standard mixes that may not be appropriate for the site’s ground and climatic conditions. Ground preparation and a maintenance schedule that includes weeding of unwanted species, cutting regime, potentially some reseeding and removing cut material to reduce site nutrients will be key to its success. Resources for management must be available to manage the meadow and keep it in good condition.

Future Management

Meadows require regular maintenance and this can be higher during their establishment and getting them into good condition. An appropriate cutting regime is the main requirement once established.

Meadows need to be cut regularly, in many cases twice a year. The first cut is in the autumn, usually around October when the plants have set seed for the next year (checking seed pods have released seeds), the second in the early spring before flowering plants have started to grow tall. Timings can vary to avoid some species becoming dominant. Following cutting the vegetation should be left for several days to allow seed to drop, and then removed to maintain the meadow’s low nutrient level. Any beetle banks are cut more irregularly, and any bare ground patches retained.

For some plants (for example primrose and cowslip) there is always an active part of the plants growing crown above the surface of the ground and the height of the cut needs to avoid damaging this. When cutting wet meadows care should be taken to ensure the ground does not get rutted or compacted by cutting machinery.

Plants within woodland and shrub areas may not need to be cut as regularly as open grassland, but it needs to be enough to stop unwanted species from becoming dominant while not negatively effecting the plants being encouraged. Thinning of trees and removing woody vegetation might also be required. For hedgerows woody species such as bramble can be allowed to establish in some areas so some zones of the hedge might have different management regimes.

The meadow should be regularly inspected for non-native and invasive species that can reduce its diversity over time. Dominant grass species can also reduce wildflower diversity as it matures, which can be managed by encouraging yellow rattle, scarifying, cutting, use of appropriate plug plants and re-seeding.

Regular surveys can be undertaken to see how well species have established and what species have come in over time. The management regime may need revising to benefit species that have naturally established or failed to establish well, with reseeding or plug planting into the sward.

Complementary Measures

A number of measures can incorporate mini-wildflower meadows including orchards (measure 3), woodlands (measure 4), living roofs (measure 5), hedgerow (measure 7), hibernacula (measure 9) and bee banks (measure 10). Wet meadow mix can be used in wildlife ditches and swales (measure 20) if not permanently covered by water, around biodiverse SuDS ponds (measure 21), wildlife ponds (measure 22) and rivers and burns (measure 23).

As wildflower meadows are important habitats for nocturnal insects and foraging bats, where light sources are necessary these should be wildlife friendly (measure 18).

Nature Notes

When the correct seed mix for the area and habitat is chosen and combined with a suitable cutting regime, a wildflower meadow creates a diverse and large number of flowering species, enhancing the landscape and biodiversity. Mown paths can provide for access. Where there is concern that a meadow might be perceived as ‘untidy’ and not being maintained, signage or interpretation boards can explain their purpose, wildlife benefit and some of the wildflower species and wildlife to look for. This will increase awareness and help build community buy in, preventing the potential for negative reaction from local users.

Further Information

- On restoring, creating and managing wildflower meadows see the Bumblebee Conservation Trust’s Grassland restoration and creation… for bumblebees, Butterfly Conservation’s Meadow creation and management video, or the RSPB’s Create a wildflower meadow

- Plantlife’s guide on Managing grassland road verges provides information of wider interest for managing wildflower grassland

- On small meadows see the RSPB’s Make a mini-meadow guidance

- On beetle banks see the RSPB’s Beetle banks guidance

- On the selection of plants see the Royal Horticultural Society’s Find a plant database (to produce a filtered list of native wildflowers)

Measure 3: New and Old Growth Orchards

Orchards consist of five or more fruit or nut trees that are planted for the food they produce, often with a mix of different species and variety of fruit trees. They can be planted in larger gardens or communal green space shared by users of a site, or a community orchard can be established. Existing traditional or old growth orchards can be found on sites subject to development, and these can be brought back into condition with pruning, taking grafts to establish new trees of the same variety, and reintroducing management.

Orchards are more than the trees, with an understorey that can be sown and managed as a meadow, fallen trees and log piles providing deadwood features, and often enclosed by a hedgerow (containing flowering shrubs such as hawthorn and dog rose) or wall.

Benefits to Nature

Orchards can be exceptionally species rich environments, with the most valuable comprising multiple trees of multiple species. They provide important floral resources (especially for early season pollinators), and a large number of invertebrate species like this type of habitat or feed directly from the trees. The fruit borne by the trees in autumn provide an important sugar source for late season insects and food source for birds, with larger fruits lasting in to the winter.

As orchard trees grow and mature they provide a suitable substrate for many species of lichen and moss to grow on, with many of conservation interest reliant on this type of habitat. Old growth orchard is of special importance and particularly difficult to replace. Veteran trees can also contain rot holes and sap runs, providing feeding and nesting habitat for a wide variety of birds and invertebrates. Many insects and their larvae will feed on the tree’s foliage, and ultimately support their predators, including small mammals and birds. The ground flora and flowering shrubs in any attached hedgerows also provide important sources of additional nectar for dead wood invertebrates (which are often not very good dispersers).

Other benefits of orchards include absorbing air pollutants, carbon capture, crop pollination and pest control, providing shade and cooling, water management, food provision, well-being and recreation.

Key Requirements

Orchards can be very variable in size, from as few as five fruit trees in a garden or on a small site, to multiple groups of trees on a larger site. The soil must be of adequate depth and type to support the trees, and avoid frost pockets where possible. The trees will need to be protected from browsing animals, such as rabbits or deer. The ability to manage the ground cover and undertake regular pruning is required, which will be greater for old growth orchards.

Future Management

When orchard trees are first established watering may be required until they are well established. A schedule of yearly pruning will encourage the trees to develop the best form for bearing fruit, and produce strong fruit crops. Rejuvenating an old growth orchard may require harsher pruning to restore the health of the trees, and more understorey management to remove any weedy or invasive species which have become established. Any replacement trees should be of similar varieties where possible, with consideration given to taking cuttings from the original trees (to protect historic varieties).

Any other biodiversity measures incorporated into the orchard, such as bird boxes, will need to be maintained as required.

Complementary Measures

A large number of other measures can be incorporated in an orchard, including bee boxes and bricks, and a bee bank (measure 10) where there is a large enough open space with direct sunlight without canopy cover. Bee species that use these are some of the best pollinators of fruit trees.

Log and leaf piles (measure 8), hibernacula (measure 9), bug hotels and boxes (measure 11) and hedgehog houses (measure 12) will encourage invertebrates, amphibians and small mammals that predate on other invertebrate species that could cause damage to the orchard, providing a natural pest control. Bird and bat boxes (measures 13 and 15) can be placed on older orchard trees that are able to support their weight, or on trees or structures nearby, with young birds especially preying on potentially damaging caterpillar species. As orchards can be important habitats for nocturnal insects and foraging bats, where light sources are necessary these should be wildlife friendly (measure 18).

A wildlife wall (measure 16) or hedgerow (measure 7) can be used to establish the orchard’s perimeter and provide shelter. A wall also provides basking areas for many invertebrate species, and the hedgerow can complement the orchard’s resources for pollinators and predators. The understorey of the orchard can be sown with a wildflower meadow mix (measure 2).

Nature Notes

Old growth orchards are valuable historic and biodiversity features that usually support a large diversity of wildlife. However they have been in rapid decline in our landscape, and where neglected their trees can take several years to return to good condition. Where development includes an old orchard its protection and enhancement should be prioritised where possible.

New orchards, even small ones, will enhance biodiversity, and can become an important community feature. Even small orchards will produce fruit that will be well received by the community (leaving some for wildlife), providing an opportunity for promoting the connections between people and nature, supported by interpretative materials where appropriate.

Further Information

- On planting and enhancing an orchard see NatureScot’s Garden for orchards to help local wildlife guide and the Woodland Trust’s Orchards guide

- For a wide range of advice, information and practical management guides see The People’s Trust for Endangered Species Traditional orchards project

Measure 4: Trees, Scrub and Woodland

Trees take many years to establish and provide good habitat, and retaining and enhancing existing trees, scrub and woodland wherever possible will be of greatest amenity and biodiversity value. Veteran trees are particularly rich in biodiversity, and should be incorporated within the planned development and protected from damage during construction, especially the root zone.

But planting trees and woodland, or allowing them to regenerate, can provide an important enhancement for biodiversity, and enhance connectivity both on- and off-site. Native trees appropriate to the area should be prioritised as these will support the most wildlife, but non-natives can benefit biodiversity when their flowers, fruits, berries and seeds can be utilised by wildlife (avoiding any that could self-seed and become invasive). Trees can be incorporated in a variety of forms, including individual trees, rows of trees, a small copse, mini woodland or more extensive woods.

- Street trees can be planted in tree pits along roads or pavements, and within gardens or grounds beside them. Lining a route provides a corridor for wildlife to move through development, connecting landscape planting, hedgerows, woodland and greenspace on- and off-site. Feature trees can be planted in groups or corridors, providing benefits for sustainable urban drainage schemes and urban cooling, as well as biodiversity.

- Scrub is formed of low growing woody species and immature trees that will eventually grow into woodland, or planted as a transitional zone on the edge of existing or created woodland. It can provide shelter for development, and dense scrub can protect habitats from light, noise and air pollution, and discourage public access with thorny species.

- There are many different types of woodland, depending on the ground type, species and local environment conditions. This can include riparian or wet woodland species that enjoy wetter conditions (such as alder and willow), planted at the edge of wetland or water features. The value of the existing habitat that will be replaced by trees, its availability within the area and species using it needs to be considered, and improving connectivity where possible with on- and off-site woodland.

Benefits to Nature

Native tree species support a large number of native species, providing leaves for invertebrates to feed on, floral resources especially for early season pollinators, berry and seeds for birds (particularly important for winter migratory species). They also provide shelter, roost and nest sites, and can connect habitats within and around development. Biodiversity generally increases as trees mature and woodland develops a diverse understorey and ground cover, including deadwood, which supports significant populations of invertebrates.

Scrub is very valuable for biodiversity, providing dense areas of early flowers for a range of pollinators, a large amount of fruit for many winter thrush species, and a large number of insects feeding on the scrub that are prey for others. It also provides a key nesting area for many birds.

Small mammals gain foraging and shelter (and larger mammals in bigger woodlands), including hedgehogs, red squirrel and pine martens. The tree species themselves and certain woodland types can be a priority for action in Local Biodiversity Action Plan, for example establishing new areas of Aspen. Riparian woodland is also a key contributor to the aquatic system, as an important source of organic matter supporting invertebrates, providing shade that helps regulate light levels and water temperature, and shelter for emerging semi-aquatic insects, particularly important for the development of chicks fed on flying insects and a prey for bats and fish.

Other benefits of trees, scrub and woodland include absorbing air pollutants and noise, carbon capture, providing shade and cooling, screening light pollution, water management, well-being and recreation.

Key Requirements

Street and feature trees can be planted where space only allows for a single tree if soil of suitable depth and type is present, with space for growth over time. A large enough area of living soil around the tree should be left unpaved so that it can properly feed and support the tree, with permeable and semi-permeable surfaces allowing enough water to reach their roots. Its water requirements will change over its life cycle, and the extent of their roots and impacts on other street infrastructure requires consideration.

A woodland requires an area large enough to include multiple trees of a mix of species, and ideally with scrub around its edge transitioning in to meadow or grassland. A smaller area may be able to accommodate just scrub planting, or scrub with a few emergent trees. The trees need to be spaced out to allow enough light to penetrate and sustain ground cover and scrub (requiring less space, ‘Wee Forests ’ are high density, native species pocket sized woodlands). The soil depth and type must be suitable for the selected tree species.