Tentsmuir NNR - visiting the reserve leaflet

Welcome to Tentsmuir National Nature Reserve, managed by NatureScot

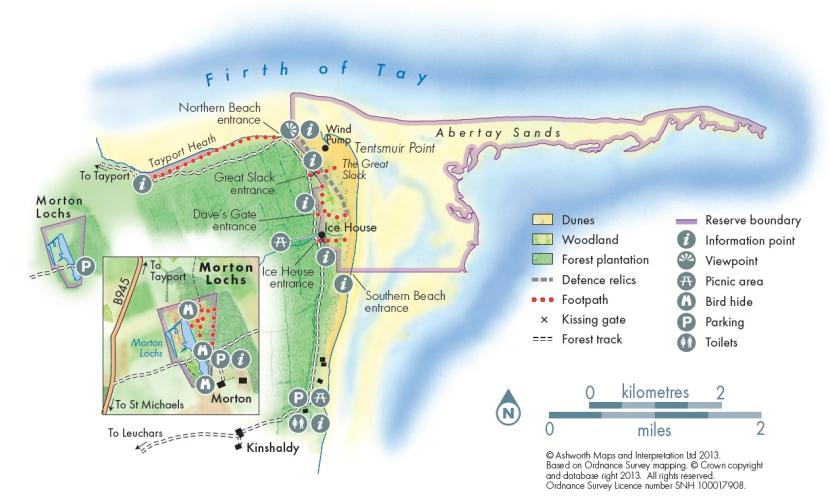

Visitors are welcome here at all times of the year. Several gateways lead in to Tentsmuir National Nature Reserve from the easternmost road through Tentsmuir Forest. Access is also possible along the shore from the Forestry and Land Scotland’s Kinshaldy car park and along the foreshore from Tayport.

Growing point

At Tentsmuir, the mighty River Tay is one of the power sources giving unusual thrust for growth and change. The Tay disgorges more water than any other river in Britain. At peak flows, this can be the same as more than 2000 freshwater bathloads hitting the North Sea every second.

The sea swirls its own currents and tides within the outrush from the Tay and the smaller River Eden. One spectacular fall-out of sediment from this watery push and tug is the Abertay Sands, which stretch eastward beyond the landward tip of

Tentsmuir.

Abertay’s glistening curves and channels are fully revealed only at the lowest of tides, but this sand system is a vital part of the whole Reserve. It’s a haven for seals and birds and provides raw material for the growth of Tentsmuir’s land, in the form of sand transported by tides, then dried and shunted westward by winds. Grain upon grain, this adds to the foreshore.

True grit

Plants take up where the sea leaves off, helping to trap wind-blown sand, then bind it in their mesh of roots. Those in the vanguard of coast creation – such as sea rocket, lymegrass and marram grass – have to be tough. Sand storms; drenching salt spray; shortage of fresh water; extreme high and low temperatures – these are all part of survival at this wild edge.

Further inland, the front line of sand-binding grasses gives way to a greater variety of plants. On grey dunes (named for their mat of vegetation), mosses and lichens are abundant. The hollows on the side of the dunes away from the wind hold even more varied plant life, including low-growing bushes of creeping willow

Inland again, towards the forest edge, dune heathland with abundant crowberry and cross-leaved heath grows in the more acid conditions on the Reserve’s longest established sands.

Landscape wizardry

The northern part of Tentsmuir is one of the fastest growing parts of Scotland, while at the southern end the sea is making inroads, plucking sand back to the deeps. This makes the Reserve a key site for studying the processes that mould beaches and coasts.

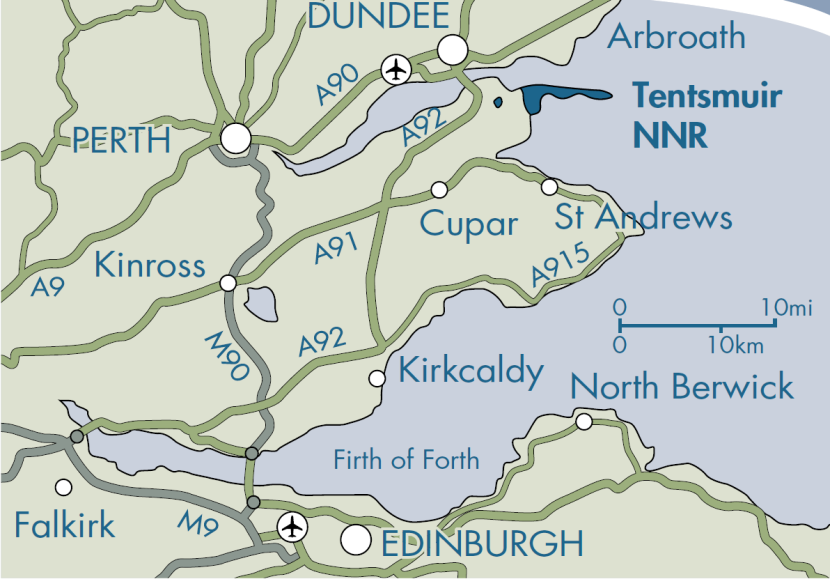

Tentsmuir National Nature Reserve lies some 2.5 miles (4kms) east of Tayport, or 1.5 miles (2.5kms) north of the Forestry and Land Scotland car park, signposted Kinshaldy Beach, off the B945 Tayport to Leuchars road.

Find out more

- Tel 01382 553704 or email [email protected]

- Support this NNR at nature.scot/donate-nnr

- Follow @TentsmuirNNR on social media

- Visiting the reserve

- About the reserve

- Getting Involved

- Visit more of our nature reserves

A finger’s breadth a day

You can get some measure of Tentsmuir’s awesome expansion by using a road, the forest, a finger and some strides.

Some 8000 years ago, wandering tribesfolk in the area would have seen a shoreline close to where the Leuchars to Tayport road now runs, several kilometres from the present coast.

A 12th century monk, who surveyed Tentsmuir as part of the St. Andrews Cathedral lands, spoke of it as a bandit country populated by ‘devils, bears and oxens’. In his time, the boundary between land and sea would have been deep within where the forest now stands.

By the early 1800s, the shore was close to the forest’s eastern edge. Then in 1941 during the Second World War came the clearest time-marker of all with the installation of a line of large concrete blocks as defence against enemy tank landings.

Since then, some of the anti-tank blocks at the southern Reserve edge have been overwhelmed by the sea. Elsewhere, much of the broad plain of the Great Slack separates them from the water, showing that Tentsmuir has since grown by about five metres a year.

That’s an astonishing increase. Think of it as being like a finger’s width each day and you’ll begin to get the picture. Take five paces seaward from the anti-tank block near the forest to imagine one year’s growth, then look to the coast for the idea really to sink in.

The heavy team

Big, hairy and helpful – that’s the small herd of cattle used to graze the Reserve in summer, helping to keep the area free of tree cover and so conserve its value for wildlife.

Sheltered by the forest, the more open dune areas can soon be invaded by seedling trees. That’s why a major programme of tree and scrub removal has been carried out in recent years, restoring 95 per cent of the Reserve to mainly dune grassland and heathland. The heavy team is helping to keep further tree and bush growth in check.

Pump up the value

Dune ‘slacks’ are hollows whose bottom sits close to the water table below. So the sand in them can be damp or hold shallow pools, encouraging rich plant life. The Great Slack at Tentsmuir is a superb example, with its floral show through spring and summer.

Yellow flowers of bird’s-foot-trefoil, pink petals of seaside centaury, a purpling of northern marsh orchids and the pure white of grass-of-Parnassus are some of the colour tones that make the dune grassland and wetland areas zing. And above and on them you’ll find many kinds of insects, including butterflies such as common blue and grayling, and day-flying burnet moths.

Further inland, Morton Lochs is home to a variety of dragonflies and damselflies, and the open water and surrounding vegetation give food and shelter to waterbirds, amphibians, and the elusive otter.

Here’s looking at you

The Tay and Eden estuaries have enormous value for wildfowl and waders, especially between autumn and spring. That’s when thousands of geese such as pink-feet from Iceland, shorebirds such as bar-tailed godwits and grey plovers from Siberia and ducks, flock and feed around Tentsmuir’s rim.

The vast flock of eider ducks that gathers in the outer part of the Tay between October and March is a star turn among this abundant birdlife. It’s the largest gathering of these ducks in Britain and Ireland, and benefits from the mussels that grow on coarse gravels near the river mouth. Impressive numbers of grey and common seals also use the area throughout the year. The greys – sometimes as many as 2000 of them – like to haul-out on the Abertay Sands and the sandbank near the southern sea fence. Up to several hundred commons use all the sandbanks and the southern foreshore.

Reserve map