NatureScot Research Report 1318 - Nature’s contribution to people and community engagement: socio-cultural and economic perceptions of beaver presence in the environment

Year of publication: 2023

Authors: Johnson, V., Martin, A., and Delugin, C. (Centre for Living Sustainability, UHI Inverness)

Cite as: Johnson, V., Martin, A., and Delugin, C. Nature’s contribution to people and community engagement: socio-cultural and economic perceptions of beaver presence in the environment. NatureScot Research Report 1318.

Keywords

Beaver; Castor fiber; translocation; conservation translocation; reintroduction; socio-cultural perceptions; participatory action research; Beauly catchment; nature’s contribution to people

Background

A formal reintroduction of Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) to Scotland took place in 2009 after a 400-year absence (having been driven to extinction). This was done through the licensed Scottish Beaver Trial which took place from 2009-2014 in Knapdale, Argyll (Jones and Campbell-Palmer, 2014). Larger populations have become established in Tayside and the Forth valley following unofficial releases and/or escapes (Gaywood, 2018; Dowse et al., 2020). Having been granted European Protected Species status in May 2019 by the Scottish Parliament, there is now serious consideration being given to further conservation translocations of beavers to other areas in Scotland.

To this end, Scotland’s Beaver Strategy 2022-2045 (‘the Strategy’) was published in August 2022, which included setting out the steps required to implement conservation translocations and manage beavers in the short to medium-term. Within the Strategy, it is acknowledged that beavers have an ecological, social, and economic impact, and their presence might not be appropriate in all locations where they might potentially thrive. The Strategy is therefore a ‘working document’ comprising a range of themes, goals, and objectives including the stipulation that ongoing research on beavers be undertaken.

As a result, NatureScot, and the organisations involved in producing the Strategy, are seeking a greater understanding of perceptions of beavers, improving community engagement in decisions about beavers, and increasing and communicating the ecological, environmental, social, and cultural knowledge base on beaver effects and impacts. In March 2021, a partnership was established between UHI Inverness, NatureScot, and cbec ecosystem engineering to undertake research on the ecosystem roles of beavers. The collaboration established four research objectives concerning: (i) beaver effects on physical processes, (ii) socio-cultural perceptions of beavers, (iii) the communication of research outputs, and (iv) support for additional research, monitoring and teaching opportunities.

This report specifically focuses on objective (ii) the socio-cultural objective of the wider project. It also relates directly to the Goal 8, Objective E, Action (i) of the Strategy, and the requirement to undertake research on the current perceptions/impacts of having beavers, across different stakeholders and at differing scales (p.32). It should be noted that the Strategy was not published until late in the research process (August 2022). The implications of this on the project are explored in the body of this report. This includes recognition that achieving more locally accepted conservation translocation requires time for broader consultation in the community and ongoing information and education regarding beavers and nature’s contribution to people.

The purpose of this research was to work with a community to explore perceptions (views, ideas, opinions, and feelings) about beavers and their potential translocation. Working with local communities to understand socio-cultural perceptions and the potential impacts of beavers being in, or returned to, a catchment is crucial as social factors hold implications for the success or failure of such wildlife reintroduction projects (Coz and Young, 2020; Auster, Barr and Brazier, 2022a). The potential for human-wildlife conflicts to arise, which are seldom only about ecological factors, is a particular concern (Glikman et al., 2022).

The overall aim of the project was to inform policy and management practice regarding beaver conservation translocation within Scotland through an exploration and greater understanding of socio-cultural perceptions of beavers and their effects.

Specific objectives

- To collate, analyse and report field-based evidence of beaver presence effects on socio-cultural and economic perceptions associated with ‘cultural ecosystem services’ and ‘nature's contribution to people’ that relate to people’s recreational, educational, and spiritual interactions with the environment, plus provisioning/regulating and supporting ecosystem services that all contribute to human well-being and have socio-cultural and economic effects.

Under the overall objective specified above the following sub-objectives were developed at the outset of the research process in collaboration with NatureScot:

(a) Implement community-engaged research that seeks to understand differing perceptions of beavers, where beavers have already been or are likely to be translocated.

(b) Capture this experience as a detailed case study in a community where beavers have been or are likely to be translocated.

(c) Encourage dialogue on policy and practice relating to beavers locally and regionally, combining stakeholder and community perspectives with evidence from physical and ecological dimensions of the wider research project.

d) To communicate the outputs of the above work through a local community conversation held within the case study community, circulation of the report directly within the community, and dissemination of the findings nationally and academically.

Activities completed to meet objectives

An initial workshop with key stakeholders, including NatureScot, Forestry and Land Scotland, and selected local landowners, was conducted to identify a suitable location for the research. The case study site selected was the River Beauly catchment (‘the catchment’), which extends from Loch Affric to the lower reaches of the Beauly Firth and includes the sub-catchments of the Rivers Glass, Cannich, Affric, and Farrar. This was chosen due to the existing presence of a small number of beavers (from prior escapes/unofficial releases) and a proposal (‘the bid’) led by Trees for Life in collaboration with local landowners, to reintroduce beavers to the upper Beauly catchment through the conservation translocation of animals from Tayside. As any conservation translocation bid, including those involving a licence application, requires consultation as stipulated in the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations, a meeting was held with Trees for Life to ensure this research was complementary but separate to the community consultation work they were undertaking. It was agreed with all stakeholders that it was important for the UHI research team to remain independent of the translocation bid but that the context of the bid provided an important ‘real world’ dimension to the chosen case study. The Trees for Life community consultation was undertaken concurrently, and as anticipated, had a bearing on this project, the implications of which are discussed in detail in the findings and recommendations within the main report.

Participatory action research was undertaken between March and October 2022, with 82 individuals participating from local communities across the catchment. This comprised the research team going out and inviting people to interact with a range of material (posters, post-its, stickers) at various public locations. All participants were coded by gender, age, location (residency in the catchment), and relationship to land (see Table 3 in the main body of the report and the Methodology section for a detailed explanation of the methods, including the use of coding). The research explored:

- Perceptions of beavers (in general but also situated temporally and spatially), encompassing the role of beavers ecologically, culturally, and economically.

- Community members' sense of context, place, and change relating to beaver presence in the landscape.

- People’s views on the proposed translocation of beavers to the Beauly catchment and their responses to the associated consultation process being undertaken by Trees for Life.

- Views on the management of beavers and associated governance of their translocation and reintroduction.

Towards the end of the research process a community conversation was held to share findings and encourage dialogue locally. This is a key component of participatory research, but it also fed into the broader communication objective of the research. In this conversation, details about the full research project, including findings from the physical, ecological, and socio-cultural work, were presented to the community with participants interacting with those findings in a process of participatory action planning. On completion of the study and reporting process, full project outputs will be communicated and made accessible to a wide audience.

Implications of context on the research

This research took place within, and therefore interacted with, a dynamic and evolving policy context. This context influenced the availability and awareness of guidance and information, and the processes and practice of community engagement. Government-led support for the proposed expansion of a large mammal species throughout Scotland, including potential active intervention through conservation translocation, is significant and unmatched in possible scope/impact. The nature of engagement sought with those interested and/or affected by these proposals is under development. ‘Proportionate stakeholder engagement’ is well referenced in the Strategy. ‘Stakeholder engagement’, the role of communication in ‘public engagement’, and the need for ‘consultation’ are also referenced within the Best Practice Guidelines for Conservation Translocations in Scotland. However, precise details stipulating the nature, extent and scope of engagement, or how formal community consultation should be carried out, is not prescribed, with these activities considered to be contingent on the specifics of individual translocation proposals. The commissioning of social science participatory action research is also somewhat new to NatureScot. The implications of this are discussed within the body of the report and the findings should be viewed in this context. In particular, certain aspects became apparent during the research process, or were established after, key elements of the research were undertaken. The specific implications resulting from this context are as follows:

- With regards to terminology – at the outset of the research (May 2022) the use of the terms reintroduction and translocation were discussed. It is acknowledged in the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations that reintroduction is one type of conservation translocation and the overarching term referenced within the Strategy is ‘conservation translocation’. However, the term ‘reintroduction’ was selected for use in the participatory materials. This reflected, in part, its more common usage at the time but it was also selected for simplicity as an accessible term which could help to introduce participants to the research. Specific aspects of beaver translocation e.g. where would the animals being reintroduced to Beauly come from and why, were then explored during interaction and discussion with participants. When exploring perceptions within an evolving policy context, the terminology used by participants is not always consistent and does not necessarily reflect official definitions. For this research it was important to document how terms were being used by those involved, in particular community members, but also Trees for Life (more detailed explanation as to how terms have been understood and used are provided within the report - see also the Glossary).

- In terms of the availability of information - throughout the research process, a range of material relating to beavers, their impacts and behaviour, potential control and recognised mitigation measures, guidance on consultation etc. was being developed, and gradually made available. Fundamentally however, the aim, was to establish what the community knew and perceived. In addition to information gaps, in some instances, material was in development (e.g. the Strategy), or even if available (e.g. on the Trees for Life website), was not necessarily known about. The focus of the research was on what participants reported, which was commonly that they wanted more information or were unaware of what was available etc. This has implications for the future communication and dissemination of information about beavers and is explored further within the report.

Main findings

Below are the main findings, which are elaborated and evidenced in the main body of the report.

Perceptions of beavers

- Perceptions of beavers within the community, their impacts, and contribution to people, were diverse. There was no clear link to gender, but there were intergenerational differences.

- There was a high degree of common understanding across participants about beaver behaviour and activities, although there was also a demand for more information.

- There were varied (and in certain instances very polarised) views about whether those behaviours and activities (e.g. beavers modifying their environment), were considered positive or negative.

- What was particularly important were the participants’ relationships to the land, for example where they had a role in conservation, land management, and/or were a landowner within the catchment.

- The research demonstrated a clear relationship between concerns about beaver impacts and the perceived likelihood of different forms of impact. These differences were largely informed by the proximity of participants’ land/property to watercourses.

- Participants’ perceptions of beavers were influenced by the context of the proposed translocation bid, specifically this was not a hypothetical exercise, but corresponded to the real potential for beavers to be actively released into the local environment.

- Perceptions of beavers and the proposed translocation were also affected (both positively and negatively) by participants’ previous experiences of, and opinions about, Trees for Life.

Proposed further action

Based on the study findings, a range of further action is proposed covering: the report, beaver impacts, beaver management, information, education, community engagement, and guidance, including responsibilities. These points have emerged through the course of the research as being considered important, with many directly specified by participants e.g. through the action planning process. More details on each point can be found in the main report.

- The report - proactive dissemination of this research in the local community and to broader stakeholders.

- Beaver impact - further social and ecological research on beavers’ presence and impacts in specific locations would be beneficial to inform communities of context-dependant effects. Citizen science approaches could also help to increase direct engagement with communities where conservation translocations are proposed and with the wider public.

- Beaver management - there needs to be greater clarity provided locally on management responsibilities, process, resources, control, and mitigation where beaver conservation translocations are proposed.

- Information - the research highlighted the need to provide general information on beavers that is easily accessible to the public and communities. Information on beaver impact and management also needs to be explained locally.

- Education - there was a general appetite for a broader and deeper understanding of beavers, their behaviour within the environment, and potential interaction with other species.

- Engagement - the methodology developed and applied within this study has increased community engagement over beavers and their potential translocation to the local environment of Beauly. It has also developed our understanding of Nature’s Contributions to People more broadly.

- Guidance - the findings of this study can help develop better support and guidance for those proposing conservation translocations as to what constitutes good community engagement and consultation.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to thank the broader UHI team including Melanie Smith, Bernd Haenfling and Victoria Pritchard, Melanie Manwaring MacKay and Helen Miller, and the partners in cbec ecosystem engineering, particularly Matthew O’Hare. We would also like to thank Professor Andrew Church for his advice on the ‘Nature’s Contribution to People’ framework. Thank you to NatureScot for the funding and co-construction of the project, particularly Martin Gaywood and Angus Tree. Also, to the investment in this research by UHI Inverness who have supported the socio-cultural and ecological aspects of the interdisciplinary research. Finally, thanks go to all those who participated in the research, specifically members of the local community without whose time and patience this type of research would be impossible.

Abbreviations

Community Assessment and Action (CAA)

European Protected Species (EPS)

Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS)

Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

Nature’s Contribution to People (NCP)

National Nature Reserve (NNR)

Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE)

University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI)

Glossary

Community consultation: the formal process undertaken by Trees for Life as part of the translocation bid and licence application.

Community engagement: a broader, less prescribed process than community consultation, utilising a variety of methods to encourage dialogue and explore perceptions.

Conservation translocation: deliberate movement and release of plants, animals, or fungi into the wild for conservation purposes. Reintroduction (see below) is a type of conservation translocation approach.

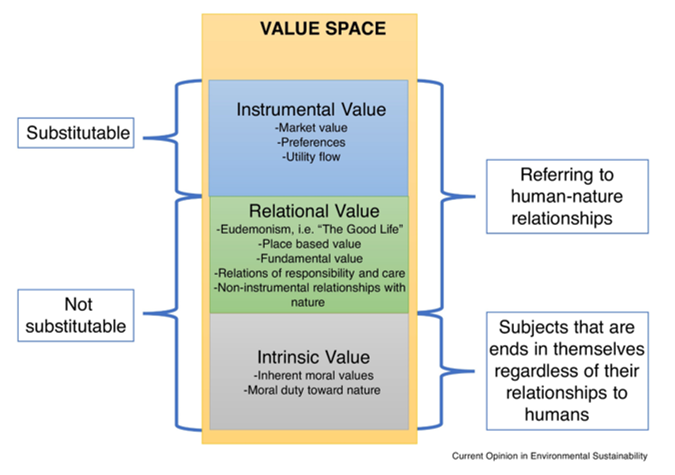

Instrumental values: values that emerge from the importance of nature as a means to achieve human ends or satisfy human needs, interests or preferences.

Intrinsic values: values that refer to the inherent worth of nature as an end in itself, regardless of any human interest.

Relational values: values that emerge from the meanings created through the relationships between people and nature.

Participatory action research: a research approach which involves researchers and participants working together to develop a shared understand, often of an issue or problematic situation, to change it for the better.

Reintroduction: species reintroductions are one type of conservation translocation. Reintroduction involves the translocation of an organism inside its natural range, to areas from which it has been lost, with the aim to re-establish a viable population.

Snowball sampling: a sampling or recruitment technique in which research participants are asked to assist researchers in identifying other potential participants.

Main body of the report

Context

Scotland’s Beaver Strategy 2022-2045 launched in August 2022, acknowledges (i) the potential biodiversity, wider environmental, and socio-cultural benefits that can result from beaver activity, (ii) the land and freshwater management challenges that can arise from the effects of beaver activity, and (iii) the conservation objectives for the species itself. The Strategy also identifies the need for research and innovation to “improve the management of the expanding beaver population through the development of new techniques, technologies, and applied research to understand the full consequences of beavers within the Scottish landscape” (p.5). Taking an interdisciplinary approach to this research can help to provide physical/ecological and community engagement methodologies for future conservation translocations and add new knowledge to the body of academic work on beavers in respect to nature’s contribution to people. The socio-cultural aspect of this research has been carried out as a partnership between the University of the Highlands and Islands (an academic institution) in collaboration with NatureScot (the statutory body responsible for coordinating the implementation of the Strategy) specifically within a context where concerns have been raised in communities across Scotland regarding beaver reintroduction and subsequent translocations.

Literature

Work to assess the feasibility and desirability of Eurasian beaver Castor fiber reintroduction began in Scotland in the mid-1990s. Several reviews, assessments and a national consultation led to a proposal for a trial. Eventually a licensed ‘Scottish Beaver Trial’ took place from 2009 - 2014 at Knapdale in mid-Argyll which included a programme of management and ongoing monitoring and evaluation (Jones and Campbell-Palmer, 2014). In the meantime, a population became established on Tayside as a result of escapes from private collections and possibly deliberate releases. A range of studies and stakeholder group reports from Knapdale and Tayside were collated, along with international work and experience, within the ‘Beavers in Scotland’ report to the Scottish Government in 2015 (Gaywood, 2015), which was used to inform the ministerial decision on the future of the species.

In 2016, Scottish Ministers stated they were ‘minded’ to allow beavers to remain in Scotland, encompassing the populations in Knapdale and Tayside. Views and experiences surrounding beavers differed, and this decision was not universally welcomed. Concerns were expressed especially in relation to the Tayside populations by certain stakeholders and land managers, over the impact of beaver activities on specific land uses, fisheries, and some conservation interests.

In May 2019, beavers became a European Protected Species (EPS) in Scotland and fully protected under the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994 (as amended). This was a formal recognition of the first ever authorised mammal reintroduction to Britain. In parallel, a ‘Management Framework for Beavers in Scotland’ was launched by Scottish Natural Heritage (the former name for NatureScot) to support the proposal to grant beavers EPS status and to set out an approach to mitigation, support, licensing, translocation and related issues. This was done in close consultation with representatives from across the conservation, environmental, land and freshwater management sectors through the ‘Scottish Beaver Forum’ (2017-2022). The initial confirmation of EPS included a Scottish Government policy stating that beavers should not be translocated in Scotland outside their current range, but that they be allowed to expand their range naturally.

Discussions surrounding the management of beavers, especially in Tayside and the adjacent Forth catchment, continued through the Scottish Beaver Forum. Licences have been issued for the removal of beavers present on Prime Agricultural Land (i.e., lands capable of producing a wide range of crops and/ or high yields of a narrow range of crops and/ or moderate yields of a wider range (Soil Survey of Scotland Staff, 1981)) through translocation and culling. In the meantime, the Knapdale population has been reinforced, in part through the translocation of animals from Tayside (Dowse et al., 2020).

In recent years, resources have been focused on the management challenges presented by beavers, particularly those on Tayside (Campbell-Palmer et al., 2015, Campbell-Palmer et al., 2022). Although there has been recognition of beavers providing hydrological benefits in some areas , including increased water storage in the landscape, flood reduction, and increased sediment, nitrogen, and carbon storage (Thompson et al., 2020), there has also been damage in terms of localised flooding and burrowing leading to riverbank collapses with associated remedial costs involved. Potential management strategies have included discussions around the practice of culling. In response, translocation has been identified as an alternative with some landowners coming forward offering to provide suitable release locations. It is recognised that species translocations, including for beavers, can be controversial through their potential negative impacts on the environment, other species, and people’s livelihoods, with the subsequent generation of conflict (Auster, Barr and Brazier, 2020a). In the context of Tayside, the importance of the landscape for agriculture and commercial forestry and the presence of beavers has led to ongoing human-wildlife conflict (Coz and Young, 2020). However, beavers are also recognised as having the potential to generate a range of ecosystem benefits (Stringer, Blake and Gaywood, 2015; Gaywood, 2018; Brazier et al., 2020). Studies have found that beaver activity and disturbance commonly increases habitat heterogeneity and structural complexity, gives rise to unique successional stages such as beaver meadows, and overall supports a greater diversity of certain plants, aquatic invertebrates, fish, amphibians, and birds on a landscape scale than in undisturbed areas (Stringer, Blake and Gaywood, 2015). Other services include water purification and supply, the moderation of extreme events, and recreation (Brazier et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020).

In November 2021, the Scottish Government announced a shift in policy to allow beavers to be translocated and moved to new release sites in Scotland outside the Tayside and Knapdale areas. The subsequent requirement for a national strategy was identified and Scotland’s Beaver Strategy 2022-2045 developed. As a result of the publication of the Strategy, a new ‘Scottish Beaver Advisory Group’ has been established, made up of key organisations who will work together as a governance group.

The overall programme of research carried out by UHI Inverness in partnership with NatureScot and cbec ecosystem engineering includes ecological and physical research, alongside the socio-cultural research detailed in this report. It was designed to investigate potential ecosystem contributions and broader socio-cultural roles that the translocation of beavers may bring to catchments and communities. The research can be used to inform actions described in the Strategy and help navigate potential conflict amongst communities. The overall research programme is innovative in piloting new ways of measuring and modelling the impact of beavers on physical processes and biodiversity, for example through the use of environmental eDNA techniques, and in proposing participatory forms of engagement to understand and respond to diverse community perspectives on conservation translocation. The intention is to provide academic research from selected case study areas to inform policy and practice relating to the ecological, socio-cultural and economic aspects of beaver conservation translocation.

Background to the Conceptual Framework

Whilst the biological components of conservation translocation have been widely studied, there is still a lack of research on the human dimensions of conservation translocations (Glikman et al., 2022) and recent studies have highlighted the importance of conducting further social and qualitative studies to investigate the complex social dimensions of wildlife reintroduction (Auster, Puttock and Brazier, 2019).

Ecosystem services refer to the benefits (in terms of goods and services) that people obtain from nature, as a result of the interplay between social and ecological systems; for example, the ability of healthy soil (resulting from complex geochemistry and ecological interactions) to grow crops and therefore be used for farming and food production (as part of a complex agricultural economy). The Millennium Ecosystems Assessment provides the most widely accepted classification of ecosystem services and described four categories: 1) provisioning, 2) supporting, 3) regulating, and 4) cultural.

There has been a growing recognition however, of the importance and plurality of cultural elements in research investigating human-nature relationships in the field of ecosystem services. New conceptualisations therefore aim to move beyond what some consider the limited instrumental and utilitarian aspects of the Ecosystem Services Framework, specifically to develop a more nuanced understanding of cultural services (Cooper et al., 2016; Fish, Church and Winter, 2016;).

A framework proposed by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (Díaz et al., 2015) introduced the concept of ‘Nature’s Contribution to People’ (NCP). NCP is an expansion of the socio-cultural and economic aspects of the ecosystems services approach which focuses on the interdependence between humans and nature, and how people understand and perceive living in balance with nature. It contains the notion of values, with three main types of values across a spectrum: instrumental, intrinsic, and relational (Figure 1).

There are commonalities and differences between the three types of values, which exist within the “value space” in orange. The three types of values, although distinct, are connected. Both instrumental and relational values are grounded in human-nature relationships, whereas intrinsic values are independent of human needs and interests. However, both relational and intrinsic are not substitutable, unlike instrumental values.

The research reported here involves the investigation of the potential impacts of beaver presence within a landscape and environment as understood by affected individuals and communities. NCP therefore provides an appropriate framework within which to situate the research. Indicators of sustainability described within the framework (which expand on the four identified within classic definitions of ecosystem services), and relevant to beavers include: habitat creation and maintenance, regulation of freshwater quality and quantity, food and feed, materials and assistance, learning and inspiration, physical and psychological experience, and supporting identities. This project also draws on socio-cultural-ecological research that specifically focuses on the link between NCP and ‘relational values’; these reflect that many values and benefits, for example ecosystem services, are manifested and given meaning through human interactions with (how humans relate to) specific environments and animals (Martín-López et al., 2018; Schröter et al., 2020). Through the lens of ‘relational values’, contributions of nature to people have been categorised under the headings of security and sovereignty, health, equity and justice, and heritage identity and stewardship (Schröter et al., 2020). Although the overall categorisations within ecosystem services, NCP and relational values vary, they are largely attempts to capture similar aspects to varying degrees. Specifically, and of relevance to this study, is the emphasis on the interaction between people and nature and the role of socio-cultural perceptions in how people understand, relate to, value, and act towards nature. It should also be noted that although the research and the participatory materials were informed by a priori concepts (e.g. as encapsulated within NCP indicators and values), throughout the research process, participants were given the opportunity to raise new ideas and issues potentially not captured by existing frameworks.

Within the NCP framework, this research explored the following research questions:

- What are the different community perceptions of beavers and their potential reintroduction/translocation?

- How are these perceptions informed by people’s experience (or lack of) of beavers, including their access to information relating to beavers?

- How do perceptions intersect with place - where people live within the catchment, their experiences of nature, and how they feel about the local environment?

- How do people’s varying perceptions of beavers relate to the socio-cultural, and economic aspects of their lives, for example their identity, roles in the community, livelihoods?

- What are community views on governance, specifically in relation to the proposed translocation and consultation process being undertaken in the selected catchment area?

- How can this research and methodology inform future conservation translocation community engagement plans and the work of organisations involved in implementation of the Strategy.

Methodology

The methodology was based on an approach to participatory action research called Community Assessment and Action (CAA) (Johnson and Nurick, 2006). This process was ‘place-based’ as it focused on a particular case study area and context and involved different parts of the sub-communities situated across a selected larger catchment community. The research was intergenerational and sought to reach a range of community members with different experiences and information about beavers, and with differing roles in the community. Therefore, participants were purposively selected, and ‘snowball sampling’ techniques (when research participants suggest other participants based on certain characteristics) were used (Johnson, 2005; Parker, Scott and Geddes, 2019). It involved a range of local stakeholders including people working in local organisations engaged in land and water management, landowners, community members, and some visitors to the area whose livelihoods were not necessarily connected to land management.

The methodology included creative and visual methods, which are considered to be accessible, expressive, and reflective practices that engage participants in knowledge production. This included the use of posters, photographs, and ranking lines (see Appendix 1), and involved visiting communities and carrying out research activities within community locations, for example outside local shops, and at community-organised events. A coding system was developed to collect information on participants, including gender, age, and place and connection/ role in the community with regards to land management (see Appendix 2). These characteristics consider aspects of an individual’s identity as well as their roles and place in a community that are likely to information perceptions of environment. The coding process allocates everyone with a unique number, and aspects of their identity (age and gender) and relationship to the land are recorded during the process of gaining informed consent and thus are only known to the research team. This coding maintains individuals’ anonymity whilst they interact with the participatory activities whilst also allowing the research team to explore the relationship between these characteristics and perceptions during analysis.

The selection of the catchment was opportunistic – a proposal to restore beavers to the catchment was made by a third party (Trees for Life). NatureScot and UHI, in discussion with FLS, decided this would be a good opportunity to undertake the socio-cultural research described here.

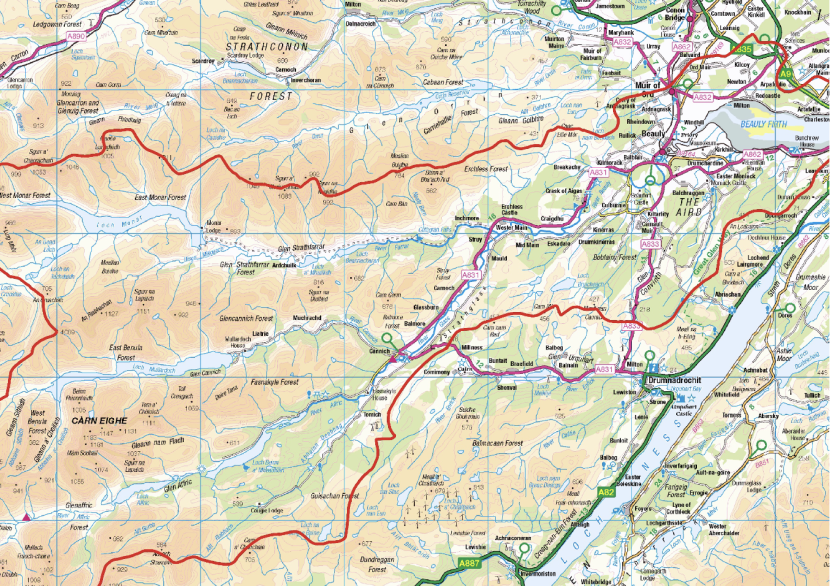

Open invitations to be involved in the research through participatory activities were posted publicly in the community and provided options for members of the public to get involved. The research team identified locations where the views of a diverse range of community members, including those involved in land management, could be recorded. This included local stores and community halls (see below for details of sessions and participants). A ‘monitoring map’ was kept to locate participants in terms of place of residence, as well as a record of participant profiles, to ensure that there was coverage across the whole catchment and the population. The ‘local area’ was defined by the Beauly catchment from Glen Affric at the southwest, to Beauly at the southeast, and surrounding settlements (Figure 2).

Please note, that for the purposes of the research and simplicity, the map was presented without the red line during fieldwork, where it was used to record participants’ location in the catchment, and for reference on the posters (see Appendix 1).

© Crown copyright [and database rights] 2021 OS 100017908

The general research approach was agreed across the partners and the UHI research team and was carried out by a lead researcher (Johnson), a researcher (Martin), and research assistant (Delugin) based at UHI Inverness. The team co-constructed the methodology and took on different roles to ensure that ethical protocols were adhered to. Themed analysis, (following Braun and Clarke 2012) was undertaken and is widely applied in qualitative analysis. The selection of quotes by the team to illustrate the themes identified (see Findings) is also part of this methodology. Lone working was avoided, and anonymity of the participants was respected. During the analysis stage, themes relevant to the research questions were identified. It was also important that a member of the team was always available to respond to any concerns about the process raised by community members, and to answer questions where possible.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Highlands and Islands, in accordance with the university’s Research Policy and Ethics. The research team developed local project-specific protocols so that the team and participants were kept informed and safe. Research data was produced, analysed, and stored in accordance with UHI data management procedures. Participant information sheets were developed to make the purpose and use of the research clear and to enable participants to provide informed consent to be involved. Consent was registered through a signature on the consent form or indicated verbally to a research team member and recorded (see Appendices 3, 4 and 5 for details of the information provided to participants during fieldwork, participant information sheets, and informed consent forms).

A ‘community conversation’ was held so that people who live and work across the catchment could be invited to see the most recent results in a local venue. This provided them with an opportunity to check that their views were represented if they had already participated, and to contribute if they had not. This is a form of verification of findings that improves the rigour of qualitative research (Creswell, 2014). In addition, all the people attending the community conversation had a chance to participate in an action planning session to draw out actions or recommendations from the results. This also provided a safe and facilitated way for local people to voice their support or concerns about the proposed reintroduction of translocated beavers into the catchment. Refreshments were provided and the team was present to facilitate the discussion and answer any questions that participants had about the research process. The research findings will be disseminated with a link to this report in the local community as well as nationally through NatureScot and UHI websites, talks and follow-up discussions and seminars.

Phases of the research

The methodology was conducted in the following phases:

Phase 1 – Inception

A planning workshop was held on 06/05/22 with NatureScot and other key stakeholders to confirm the study site and design the case study approach. The workshop involved: NatureScot providing an update on the development of Scotland’s Beaver Strategy; discussion on potential sites for the research; work to define the scope of the different project elements; and the planning and defining of stakeholder roles including a timeline of activities. There was also a visit to an enclosed beaver site and a discussion of the physical and ecological monitoring that was taking place (as part of objective (i) of the wider project).

During this time, Trees for Life confirmed the Beauly catchment including Strathglass (a sub-catchment) was being proposed as an ecologically suitable site for a potential conservation translocation of beavers. Consequently, this provided a good opportunity to undertake a parallel socio-cultural study while Trees for Life developed their proposal.

Throughout the research phases, components from the wider programme of research (involving an assessment of the role of beavers in affecting physical processes, and the development of techniques for studying beaver ecology) were discussed with participants, and their perspectives on the findings were recorded.

Phase 2 – Outreach Community Assessment and Action (CAA) fieldwork

Between July and September 2022, the research team planned and conducted the main body of research - CAA with local people across the catchment. This included outreach research with people passing or attending community events and a focus group. Six sessions were conducted in total.

Using the coding system described previously, each participant was given a unique identifier number and was asked to complete a form containing demographic questions (i.e., gender, age, location in the catchment, and relationship to the area) in order to build participant profiles (see Appendix 2). Participants were then given sticky dots and post-it notes with that same number and coding. They were then introduced to the participatory material, six posters which were put on display (see Posters 1-6, Appendix 1), and invited to use the post-it notes and dots to add comments and views by interacting with the participatory material presented (for further discussion of the posters and participant interaction see the Findings). The use of coding maintained anonymity in the research whilst also allowing in-depth qualitative analysis of variables of gender, age, residency, involvement in land use, and the intersection of these variables with the responses given.

Analysis was conducted by the research team after the community engagement sessions in order to assess findings, verify information and add to the action planning process. The core overarching research questions above (listed in ‘Background to the Conceptual Framework’) were answered during the research process using the methods presented in Table 1.

|

Research questions |

Methods |

|---|---|

|

What are the different community perceptions of beavers and their potential reintroduction/translocation? How are these perceptions informed by people’s experience (or lack of) of beavers including their access to information relating to beavers? How do perceptions intersect with place - where people live within the catchment, their experiences of nature, and how they feel about the local environment? |

A picture of a beaver was used, and participants were asked to use their post-it notes to write sentences and key words reflecting what came to mind, as well as any reasons why they picked those things. In addition, participants were asked about what they valued about their local environments, and about previous or hypothetical encounters with beavers. Their associated reactions and attitudes were recorded. |

|

How do people’s varying perceptions of beavers relate to the socio-cultural, and economic aspects of their lives e.g. their identity, roles in the community, livelihoods?

Did the location of people across the selected catchment have a bearing on their responses? |

A coding system was put in place to record participants’ demographics and eventual roles in land management. This was accompanied by a monitoring map to record the participants’ places of residence (the majority lived within the catchment). |

|

What are community views on governance, specifically in relation to the proposed translocation and consultation process being undertaken in the selected catchment area? |

Participants were asked to place their sticky dots, marked with their unique identifiers, on a ranking line to reflect their views on beaver translocations in areas of Scotland, justify why, and suggest measures that could be taken to improve translocation processes and promote human-beaver coexistence. In addition, participants were asked where they thought beavers should be released and/ or establish territories by placing their sticky dots (with their unique identifiers) on a map of the Beauly catchment, and to explain why using post-it notes. Other options were available (e.g. ‘Do not know’, ‘Elsewhere in Scotland’). Participants were also asked to write on post-it notes who should decide where the beavers should be. |

|

How can this research and methodology inform future conservation translocation community engagement plans and the work of organisations involved in implementation of the strategy. |

There have been ongoing discussions with the NatureScot and cbec ecosystem engineering partners, and other stakeholders within the catchment, about the research process and interim findings.

|

Phase 3 – Community Conversation and Analysis

A community conversation was held on 03/10/22 in Cannich Community Hall. The purpose of the community conversation was to verify and discuss findings, primarily from the CAA fieldwork of Phase 2 but also to share some of the available ecological/physical data from the wider research programme, with local stakeholders and community members. The event was advertised widely with attendance open to all. Attendees comprised many of those who had already participated but also those who were new to the research. The same coding system was utilised with attendees invited to interact again with participatory material. For those who had already participated they kept their original unique identifier whilst new participants were added (through the same process of informed consent and demographic questions). Using the unique identifier and coding system, it was possible to identify those people who had taken part at any of the previous six events, and where they had participated.

The community conversation was intended as a space for local people to participate and contribute further to the project, and to engage with each other. An interactive planning session was facilitated so that community members could contribute to a draft action plan relating to beavers and their potential translocation. The draft action plan was presented in the form of a grid which specified actions that had emerged from the CAA process. Participants could add additional actions but, importantly, were also asked to prioritise actions, provide suggestions as to who should lead the enactment of the actions, and to elaborate on the details of how, when and where actions could be supported and implemented.

Phase 4 – Further write up and analysis

Phase 4 included a detailed analysis of the data (following initial, interim assessments that had been carried out in Phases 2 and 3), which involved the identification of initial themes and patterns relevant to the research questions, a review of the themes to verify that they worked in relation to the full dataset, and a detailed analysis of each theme and how it fitted the overall research narrative. An analysis of the variables, such as by gender, age, residency, and involvement in land use, was also conducted across and within the themes that were identified during the Phase 2 CAA exercises.

The themes that had arisen from the initial tranche of data collection (Phase 2) were taken back out to the community to verify the findings during the community conversation (Phase 3). This allowed key stakeholders and members of the local communities to engage with the preliminary analysis, help verify the findings, and provide feedback as well as additional data.

|

Session |

Date |

Location |

Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

04/08/22 |

Cannich SPAR/store |

9 |

|

2 |

04/08/22 |

Kilmorack Hall |

6 |

|

3 |

05/08/22 |

Cannich SPAR/store |

9 |

|

4 |

18/08/22 |

Beauly Coop |

3 |

|

5 |

18/08/22 |

Kilmorack Hall |

9 |

|

6 |

27/08/22 |

Kirkhill Gala Day |

28 |

|

7 |

03/10/22 |

Community Conversation - Cannich Community Hall |

30-40 participants (which included participants from the previous events 1-6, and 18 new participants) |

Who we spoke to

In total, we engaged with 82 participants. The demographics of the participants are shown in Table 3.

|

- |

Number of participants |

|---|---|

|

Gender Man Woman Plus |

43 38 1 |

|

Age Under 16 16-29 30-64 65 and over |

5 7 46 24 |

|

Origin Lives locally Works locally Sometimes works locally Does not work locally (including retired) Lives elsewhere in the Highlands Lives elsewhere in Scotland |

76 47 7 28 3 3 |

Case study area

The Beauly catchment

The Beauly catchment covers approximately 1000 square kilometres of land and is the second largest north of the Great Glen, in the Highlands of Scotland, and includes the sub-catchments of the Rivers Beauly, Glass, Cannich, Affric, and Farrar.

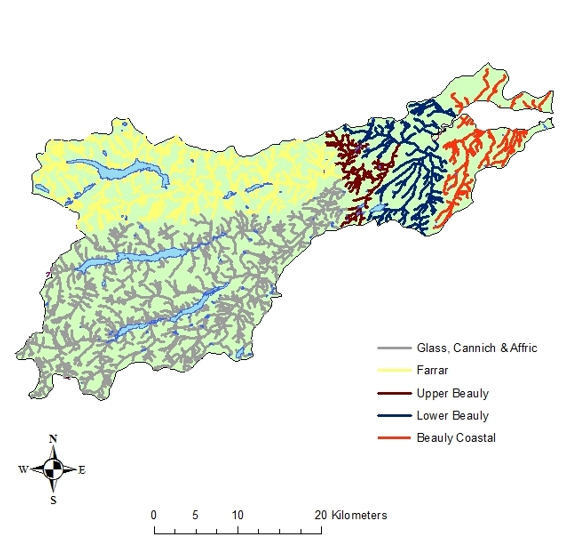

For catchment management purposes the Beauly System is sub-divided into five management units by the Beauly Fisheries Management Plan (Figure 3). These units are:

- Beauly Coastal

- Lower Beauly

- Upper Beauly

- Farrar

- Glass, Cannich and Affric

The ‘Beauly Coastal’ catchments shown in Figure 3 are separate from the main River Beauly catchment, but flow into the Beauly Firth and are considered as part of the Beauly catchment defined for the purposes of this project. Land use within the catchment is broadly similar to neighbouring river catchments with large areas owned by sporting estates (often utilised for deer stalking), and other areas used for rough grazing for cattle and sheep, and commercial timber forestry and native woodland. The largest urban centre is Beauly, located in the lower reaches of the River Beauly system. Glen Affric contains the third largest remnant of Caledonian Forest (Steven and Carlisle, 1959; Bunce, 1977) and is designated as a National Nature Reserve (NNR).

Resident beavers and the proposed translocation bid

There are currently a small number of beavers already resident within the Beauly catchment, comprising two captive groups and several escaped individuals. Some people within the catchment communities are therefore likely to have had some experience of beavers (or knowledge of these individuals and their behaviour), although community views had not been evaluated prior to this research. The availability of suitable habitat for beavers in the Beauly catchment has previously been assessed as relatively high (Stringer, Blake and Gaywood, 2015).

A proposed translocation, and associated licence application (‘the bid’) was being developed by Trees for Life during this research project. The application process was undertaken concurrently to the CAA and formed an important component of the case study context. The licence application, including the required stakeholder engagement and community consultation process, was separate to the UHI research. The Trees for Life bid was being developed in collaboration with three private landowners and FLS. The preliminary proposal involved the translocation of up to 16 adult beavers, potentially with dependent young, to the catchment, reinforcing existing individuals on the Beauly and the connected Glass sub-catchment. It was proposed that releases would be spread out over two to three years, with the Beaver Trust carrying out the translocations to land owned by those detailed above (including Loch Affric and Loch Beinn a’Mheadhain).

The Trees for Life community consultation process ran from Monday 25 July until the Monday 3 October. This was required as part of the licence application process, but also because it is an important part of best practice for any project of this type to help ensure good conservation outcomes, as highlighted in the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations

Trees for Life both extended their original consultation timeframe (from 6 weeks to 10 weeks) and ultimately amended their reintroduction proposals, in part a response to the evolving findings and interaction with the UHI research, and in response to the outcomes from their own consultation process (the implications of this are explored further in the Discussion). At the time of writing no licence application has yet been made although discussions are ongoing between Trees for Life and NatureScot. Trees for Life are also continuing to communicate and plan further engagement with stakeholders and the community should the translocation bid proceed.

Key findings

The findings from this research can be divided into three broad categories: 1) perceptions of the local environment, 2) perceptions of beavers, 3) views about the proposed translocation and consultation process. In addition, a brief fourth section introduces the action planning process. The results for these categories are separated out below for clarity. However, they are inter-linked, and the implications of this are examined in the Discussion section. Unless stated otherwise, the opinions and perceptions detailed in this research, including the terminology used and any emphasis (e.g. shown as underlined) comes directly from the participants.

The aim of the research was to access the diversity of perceptions and views held by participants. Quotes were selected to illustrate that diversity and were those considered by the research team to convey effectively the varied perceptions being expressed by participants. Although the purpose was to explore diversity, where appropriate a qualitative indication is given as to how commonly a view or perception was held amongst those who participated e.g. indicated by the use of terms such as many, few, some etc.

1. Perceptions of the local environment

Almost all the participants who took part were local to the Beauly catchment area i.e., resident in one of the communities within the catchment. Most participants expressed an appreciation of the natural environment, including the landscape, the scenery’s beauty, the variety of ecosystems, and the presence of diverse flora and fauna. Perceptions about this were sought through Poster 1 (see Appendix 1) which was presented to the participants but were also collated from responses given by participants throughout all the participatory activities. The local area was often associated by participants with a sense of peace, tranquillity, and certain remoteness (“peaceful”, “quiet”, “remote and calm”). The rural and remote setting was seen positively by a majority of participants, as it was perceived as providing a good quality of life through the provision of a “secure”, “safe”, and “unspoilt” area, protected from development.

In the context of the ‘Nature’s Contributions to People’ framework, analysis revealed that many participants valued the provisioning and regulating aspects of the natural environment highly, linked to a high quality of life. For example, the provision of “clean air” and “clear water” were associated with good health. The contribution of the local environment to positive physical and psychological experiences was also highlighted. Access to nature, and the ability of participants to both be in nature in their everyday lives, as well as being able to get out into nature for recreation, was perceived as important. Participants who lived in the area also highlighted the importance of the local community in terms of the interaction between a “good community life” and aspects such as “employment”, and a “family-friendly” environment.

2. Perceptions of beavers

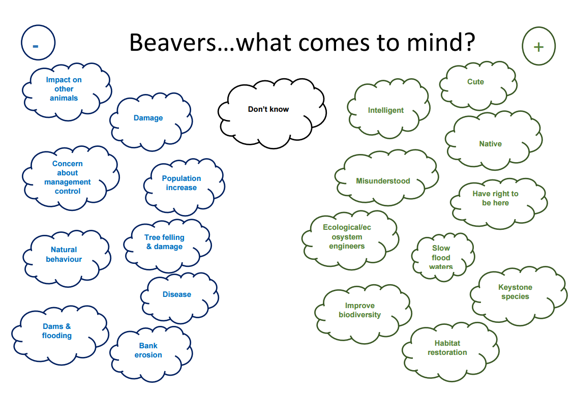

Perceptions about this were sought specifically through inviting interaction with Poster 2 (see Appendix 1) which was presented to the participants. There were diverse perceptions within the community about beavers and their contribution to people. Only a very small proportion of participants responded by saying that they did not know anything about beavers. In many cases participants reflected deeply on their perceptions and feelings about beavers and their potential translocation to the catchment. It was notable that there was not an immediate or clear dichotomy of views. Where there was a difference of opinion or concerns expressed about beavers these related primarily to whether perceptions of impacts of beavers (largely agreed upon), such as dam building, were considered positive or negative. In Figure 4, perceptions have been grouped to reflect the data collated. For example, although it could be judged as positive by some people, population increase was primarily perceived in a negative light, linked directly by participants to concerns about appropriate management.

Beavers’ appearance

Some participants focused on beavers’ appearance, describing attributes (“long teeth”, “tail”) and certain aesthetic qualities (“cute”, “beautiful”). Most of these perceptions were positive, although one participant described beavers as “tree rats” and went on to expand that they considered this a negative association to the way beavers look and behave.

Beavers’ behaviours and activities

There was a high degree of agreement across participants about beaver behaviour and activities in and around watercourses (including the construction of dams or burrowing activities in the banks) and in relation to trees (including the felling or damage of trees for dam construction or feeding). However, views varied, and in certain instances were very polarised about whether those behaviours and activities were considered to have a positive or negative impact on the wider environment (including other animal and plant species) and people.

More positive views of beavers’ activities were reflected by the participants’ use of words and phrases such as “flood control”, “they help slowing the water flow”, “ecological/ecosystem engineers”, “keystone species”, “improve biodiversity”. To these participants, beavers’ ability to modify and impact their environment was perceived to be of value. In this context, beavers were also sometimes described as “intelligent”, “ingenious”, or “complex” creatures. A few participants went into considerable detail mentioning potential benefits to specific taxa (specifically invertebrates, birds, aquatic plants) through beaver activities.

The results indicated that beavers were perceived by many participants as having the potential to have a positive impact on nature, and on people and human societies. Comments included:

“Beavers are a great addition to wildlife and a resource for people.”

Thus, highlighting that for some participants, there was a connection between beavers and their potential contribution to human well-being. One local participant involved in conservation and river restoration highlighted the potential regulating role of beavers in addressing current issues in Scottish river systems:

“Our river systems have become so degraded; beavers are one solution to this.”

Negative views about beavers were also expressed by participants. These were also related to potential modifications to the environment but in adverse ways, for example “flooding”, “bank erosion”, tree felling”, “damage to trees” or the possibility that beavers may “bring disease”. Participants expressed concerns over beavers’ impact on nature, and on the existing local flora and fauna. For example, one participant mentioned the “fragility of the flora on the river margins” and that:

“This will have a negative effect on salmon and migratory fish. We have otters and kingfishers; beavers will disturb the animals we have.”

These participants stressed a care for nature and appreciation based on the current landscape, citing the harmony of the place, and a fear that beavers’ presence will disrupt a perceived balance. More often however, concerns were expressed about beavers’ impact on people:

“Beavers will destroy land, infrastructure, trees, undermining roads”.

“What if they cause flooding on land, properties, homes?”

This included concerns over people’s livelihood (e.g. farming activity), house safety (e.g. properties in close proximity to a watercourse or located on flood plains), and infrastructure (e.g. roads, telephone poles). In this context, beavers were perceived as a potential threat to people’s sense of security and were associated with negative changes and a reduced quality of life. These participants often reported a sense of general anxiety and worry about beaver presence and translocation, illustrating the strong connection between ‘Nature’s Contribution to People’ and quality of life considerations such as security and sovereignty.

Some participants were also divided and mentioned both “good and bad ways” in which beavers influence the ecosystems they are part of. For example, a participant wrote:

“I know that they are good for biodiversity, but due to evidence I realise that they can cause damage to riverbanks and trees in riparian zones.”

Reasons behind perceptions

Reasons behind these perceptions were also explored. Some participants with more positive views referred to existing scientific evidence and reports, as well as previous reintroduction plans in other countries:

“There is scientific evidence that beavers play a role in creating natural barriers to flooding.”

“Beavers have been a success, reintroduced in 28 European countries.”

In direct contrast with the participants who mentioned other countries as positive examples of successful initiatives, others highlighted the negative impact of beavers, both in and outside the UK, including Austria, Poland, and in particular the Tayside catchment:

“Damage will be widespread, just look at the damage on the Tay, Islay and the Central Belt.”

“We know people in Tayside, they’ve told us the damage and issues that beavers have caused. Don’t want to see the same happening here.”

“The experience of beaver activity and the conflicts that arose in the Tay should not be visited on this community.”

The Tayside catchment was mentioned by many of the participants with more negative views and who had strong concerns about beaver presence in the Beauly catchment. Tayside was often used as a “reference point” providing evidence of the impacts beavers can have in Scotland. In particular, participants involved in certain land uses such as farming, were concerned about the negative impacts beavers might have on their activities and livelihoods, referencing current conflicts with farmers in Tayside and the Central Belt region of Scotland.

There were also disagreements over beavers perceived “right to be here” both in the wider context of Scotland and in the specific context of the Beauly catchment. For many participants, there was a notion that beavers deserve to be in the landscape:

“They have a right to exist, unharmed, without human intervention.”

“People have been responsible for removing beavers from the environment in the first place, so let’s bring them back.”

For these participants, the presence of beavers in the Scottish landscape had an intrinsic value, outside of a utilitarian or monetary value, that would benefit human societies. Beavers were considered as “native fauna”, by these participants, and “deserve a home and a clean, safe environment”, as they are “part of nature’s cycle”. In addition, the responses of some participants revealed a sense of moral responsibility to bring back beavers to Scotland. They perceived humans as responsible for the extinction of beavers and thus responsible for their reintroduction, to restore an ecological and moral balance. In clear contrast, others argued that beavers have “not been in the landscape for 400 years, they won’t be beneficial here”, and viewed them as a potential threat to what they perceived as the current balance in nature. A small minority perceived beavers as non-native.

As described above, some participants with more negative views and concerns perceived beavers as a threat to a current natural balance and harmony in the catchment. In addition, some participants were worried about the threats to the community’s harmony which the proposed translocation was having, mainly by putting community members in opposition to each other.

“The Strathglass community is one which I have known and lived in for most of my life and it is generally harmonious. […] As a member of the community, I am totally opposed to this proposed introduction – it will bring conflict and stress to our community – as NatureScot well know from the Tayside experience.”

The analysis indicated that perceptions and concerns did not only focus on the ecological aspects of beavers but also very much on wider social and cultural consequences, particularly those associated with the proposal to translocate beavers to the Beauly catchment. Participants were aware of a divide between members of the local communities with different views on the subject, leading to heightened tensions.

Link between views and encounters with beavers

A large of majority of participants reported that they had never encountered a beaver. Amongst these respondents, a majority declared that they would like to see a beaver in the wild in the future. Many reported excitement at the prospect of seeing beavers in the wild:

“It is exciting to glimpse any wild animal! It makes me feel privileged and promotes understanding of how important they are”.

This reflected strong relational values associated with beavers and their presence in the landscape, and positive personal, psychological experiences. Many participants highlighted that encountering beavers in the wild would increase their awareness and sense of connection with nature. However, it is also worth noting that some participants reported that they would prefer “leaving them in peace”, “without human intervention”. These participants considered that increased human-beaver interactions in the wild could have a negative impact on beavers’ health and behaviours and expressed their preference for limited interactions to avoid bothering or harming them and the general ecosystem functioning.

Most participants who did not express a wish to see beavers held negative views towards them and were concerned about the negative impacts and damage that they could cause.

Amongst those who reported seeing beavers in the past, a majority expressed positive feelings and emotions, e.g. “pleased”, “delighted”, “excited”. Some expressed that it made them “hopeful for the future” and associated the experience with a “privilege” and an “encounter with the wild and nature”. These participants had generally very positive views towards beavers. However, a few participants expressed concerns and reported feeling “concerned” and “worried”. These participants reported seeing beavers and signs of damage. For example, local farmers reported that they witnessed “damage to trees and built structures” and argued that they “do not want to see any more in the landscape”.

Relationship to demographics

There was no clear link between participants’ gender and views on beavers, although there were indications of intergenerational differences. Based on a small number of responses (a total of 12 participants were under 29 years of age) the research indicated that younger participants tended to perceive beavers more favourably and were more supportive of the bid in the Beauly catchment than older participants, whilst being aware of the potential human-wildlife conflicts that could arise from beavers’ presence.

There was evidence of a clear link between participants’ views and their involvement in land management. Relationship to the land, such as having a role in conservation, land management or being a landowner, was important in informing perceptions. There was a clear relationship between concerns about beaver impacts and the likelihood of being impacted. For example, residents having land or properties in close proximity to watercourses were often more concerned with the potential impact.

There was a relationship between perceptions of beavers and the location of the participants in the catchment. Participants were more engaged with the issues, and this research project, in the upper catchment (probably due to the fact that the translocation was proposed for Glen Affric, and the communication during the Trees for Life consultation was focused on communities above Aigas). In contrast, many participants in the lower catchment were not familiar with the proposed bid led by Trees for Life to translocate beavers in the Beauly catchment.

Beavers and the Beauly context

Participants’ views were influenced by the context of the proposed translocation bid being planned for the River Beauly catchment. Some participants, although generally feeling positive towards beavers, questioned the plan to translocate beavers into the Beauly catchment.

“Why does the local area need beavers or more wetlands?”

“Why now? Beavers are quite controversial…”

“Lack of hard facts. What does SSE [Scottish and Southern Energy] have to date about beavers’ activities on the watercourses they manage? Benefits to this specific area are unquantified.”

Some participants questioned the choice of the location (why here?) and the timeline (why now?) relating to beavers being translocated/ reintroduced in the Beauly catchment. These participants felt the need for more information: both general information on the impact of beavers (positive and negative), as well as contextual information directly relevant to the Beauly area. This included participants who reported not knowing much about beavers and requested additional information, in order to be able to make an informed decision about beavers’ and their presence in the Beauly catchment.

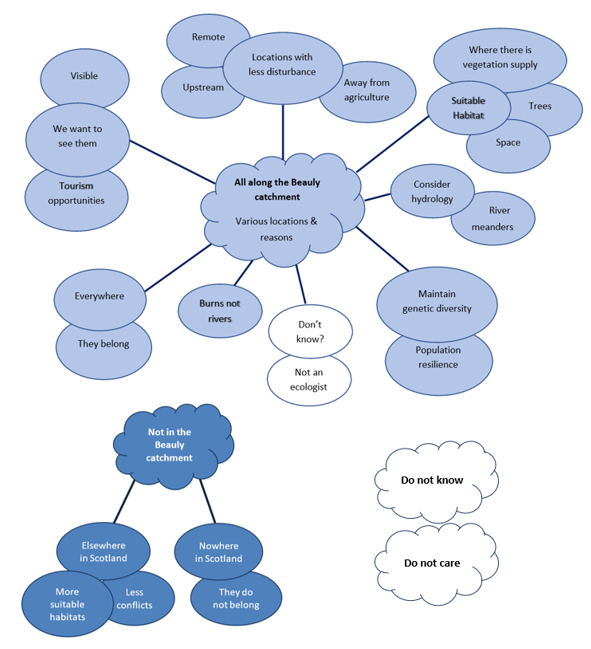

Participants were then asked about their views on where beavers should be within the Beauly catchment and/or within Scotland as a whole, and to justify why, using their sticky dot on a map and post-it notes (see Poster 5 in Appendix 1). Participants also had the option to answer that they did not know, or that they thought that beavers should not be in the catchment and/or in Scotland as a whole.

Many participants suggested various locations within the Beauly catchment (in light blue in the diagram), however, some participants disagreed that beavers should be in the Beauly catchment. These participants (in dark blue in the diagram) were either supportive of beavers’ presence elsewhere in Scotland, or were not supportive of their presence in Scotland as a whole. Participants also had the option to place their dot on a “Do not know” and a “Do not care” box (in white in the diagram).

There was a diversity of responses from participants about where beavers should be. Some participants were strongly opposed to beaver presence in the Beauly catchment. Amongst these participants, some were opposed to the presence of beavers anywhere in Scotland, whilst others argued that other locations in Scotland would be more appropriate:

“I can see that beavers may well have a place on the Somerset Levels and even on the wetlands of Caithness and Sutherland, but definitely not on a hydro river system running through tourist businesses, farms and domestic gardens. They have no natural predators and tourism will not ultimately be served once they are out of control here.”

“I quite like them to be honest, but the question is about management, and there’s no measure that could work in this specific area for beavers.”

Some participants highlighted that habitats that would be most suitable ecologically were not necessarily most suitable to avoid conflicts with human activities. For example, some participants (both ecologists and farmers) argued that the Strathglass area downstream of Glen Affric would potentially be the most suitable habitat for beavers. However, participants with an involvement in land use (mainly farming) in this area stated their worries about the perceived negative impact that beaver presence could have on their activity and livelihood:

“Almost anywhere in Strathglass would seem ideal for them but need to be sympathetic with local landowners and respect their views/concerns.”

“Strathglass but I am worried because of farms/farmland.”

Some participants viewed beaver translocation and human interests as contradictory. Amongst these participants, two main conflicting viewpoints emerged: an intrinsic valuation of nature for its own sake and a belief that nature should be given priority; and an instrumental valuation of nature because of the material or physical benefits it provides to humans and a belief that human interests should be given priority:

“This is a NNR so it’s perfect. It should be for nature, it shouldn’t be an unnatural place where human interest is first. We don’t want lots of farms, we need nature, and nature needs to work on its own terms. […] Rewilding should mean no people.”

“Put the beavers where the local landowners and businesses are not! […] Local people’s lives and livelihood should be the main priority, not beavers.”

The two quotes above reflect these diverging positions with both participants viewing nature and human interests as mutually exclusive. However, the majority of participants highlighted that a “middle ground” is desirable which reflects the needs of nature and people.

Who should decide: the question of governance and responsibility

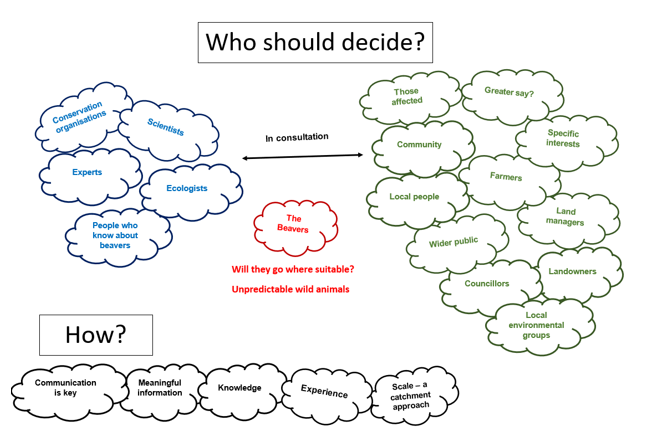

Participants were asked who should decide where beavers should be, leading to a wide variety of answers, presented in Figure 6.

A wide range of stakeholders was suggested by participants. The blue text lists the stakeholders who have scientific knowledge relating to beavers, the green text lists other human stakeholders, and the red text corresponds to beavers. The black text lists the strategies suggested by participants to support good governance.

A large majority of participants were positive towards the involvement of local communities in the process of decision-making:

“Communities, where all have a voice as to what happens in their locality. Keep opinions local.”

“The local community should choose as ultimately beavers will affect their lives and they will live alongside them.”

“Only the local community.”

Most participants argued that this should be a shared decision between various stakeholders, mainly between expert individuals and organisations and members of the local community:

“Environmentalists/ ecologists/ beaver experts/ rewilding organisation BUT in discussion and consulting with community, landowners, local businesses, children – so everyone feels included and have received education on beavers’ needs.”

“Experts, and gain support from landowners and communities.”

Some participants argued that the decisions should be made by (or at least in close consultation with) people whose livelihood or activity were “most likely to be impacted by beavers” i.e., those people with land and properties in close proximity to the watercourse or located on the flood plains.

“The farmers, homeowners and business owners are likely to be most affected and need to agree. Landowners at a distance may not care.”

“None of the estates that are in favour of the proposal are directly affected by the course of the rivers.”

Moreover, these participants often argued for a catchment-scale approach. Indeed, they argued that as beavers were very likely to move across the catchment, it would therefore be important to involve communities across the whole catchment. This point was raised specifically by participants in the Strathglass area of the catchment.

It is also worth noting that participants involved in conservation pointed out that:

“Beavers are not predictable, any expert advice that you are given is not going to guarantee that beavers will stay where you want them”.

“Beavers don’t read books.”

These participants highlighted that rewilding projects involve a level of unpredictability and uncertainty, as they involve wild animals and living creatures. However, this uncertainty is often a source of anxiety and worry amongst local communities. They often argued that such information needs to be communicated to the public, in order to manage people’s expectations on the levels of planning and control that can and should be undertaken.

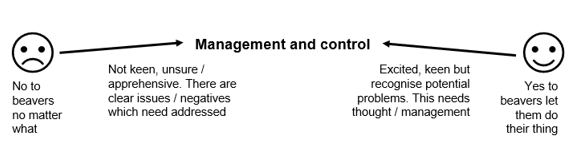

3. Potential reintroduction and the translocation bid consultation

Participants were asked how they felt about the reintroduction of beavers to new areas of Scotland using a ‘ranking line’. At each end of the ranking line were two extremes, one end represented by a happy face and the other by a sad face (see Poster 4 in Appendix 1). Interestingly, there was a wide range of views, with most participants placing their coloured, coded dot somewhere along the line between the two extremes. Respondents were also asked why they felt this way, and what would need to happen to move from ‘sad’ towards ’happy’. This was primarily in terms of them personally, but several respondents also answered this with regards to general concerns about beavers they were aware of (e.g. in instances where they were happy about reintroduction but appreciated that other members of the community were not). People’s feelings varied. The associated discussion and further questioning led to a variety of suggestions about support or actions which could potentially make people feel happier about reintroduction. Although the participatory material presented reintroduction more broadly (Poster 4 in Appendix 1) and a number of participants did reflect on this issue more generally (i.e. considering Scotland more widely and not necessarily referencing Beauly), responses were overwhelmingly focused on suggestions relating directly to the specific proposal to reintroduce beavers to the Beauly catchment through translocation.

Analysis of the data revealed a range of views, although many participants reported feeling positive towards beaver reintroduction / translocation both in general and specifically with regards to potential releases in the Beauly catchment.

A variety of supporting views were expressed, associated with the positive impacts perceived and reported in section 2 above such as:

“I think it will really benefit the ecosystem and the regeneration of habitats.”

“Opportunity for wider education/ understanding of functioning ecosystems and all its necessary parts.”