The Jewel of the Forth Guidebook - Exploring the Isle of May NNR

Note: Isle of May NNR map and guidelines are available.

Welcome to the Isle of May

The Isle of May National Nature Reserve (NNR) is owned and managed by NatureScot. Lying at the mouth of the Firth of Forth, the island is 1.5km long and 0.5km wide.

This iconic reserve is hugely significant for its thousands of breeding seabirds in the summer and internationally important grey seal nurseries in the autumn. During the spring and autumn, the island is also one of the most important migration stations on the east coast for migrant birds travelling to summer and wintering grounds.

In 1956 the Isle of May was designated as a National Nature Reserve. It has many other national and international designations; they help to ensure the habitats and species found here are protected. We manage the island sensitively to conserve it for the future and to keep the precious wildlife safe. Please help us keep it that way and enjoy your visit.

The importance of the Isle of May

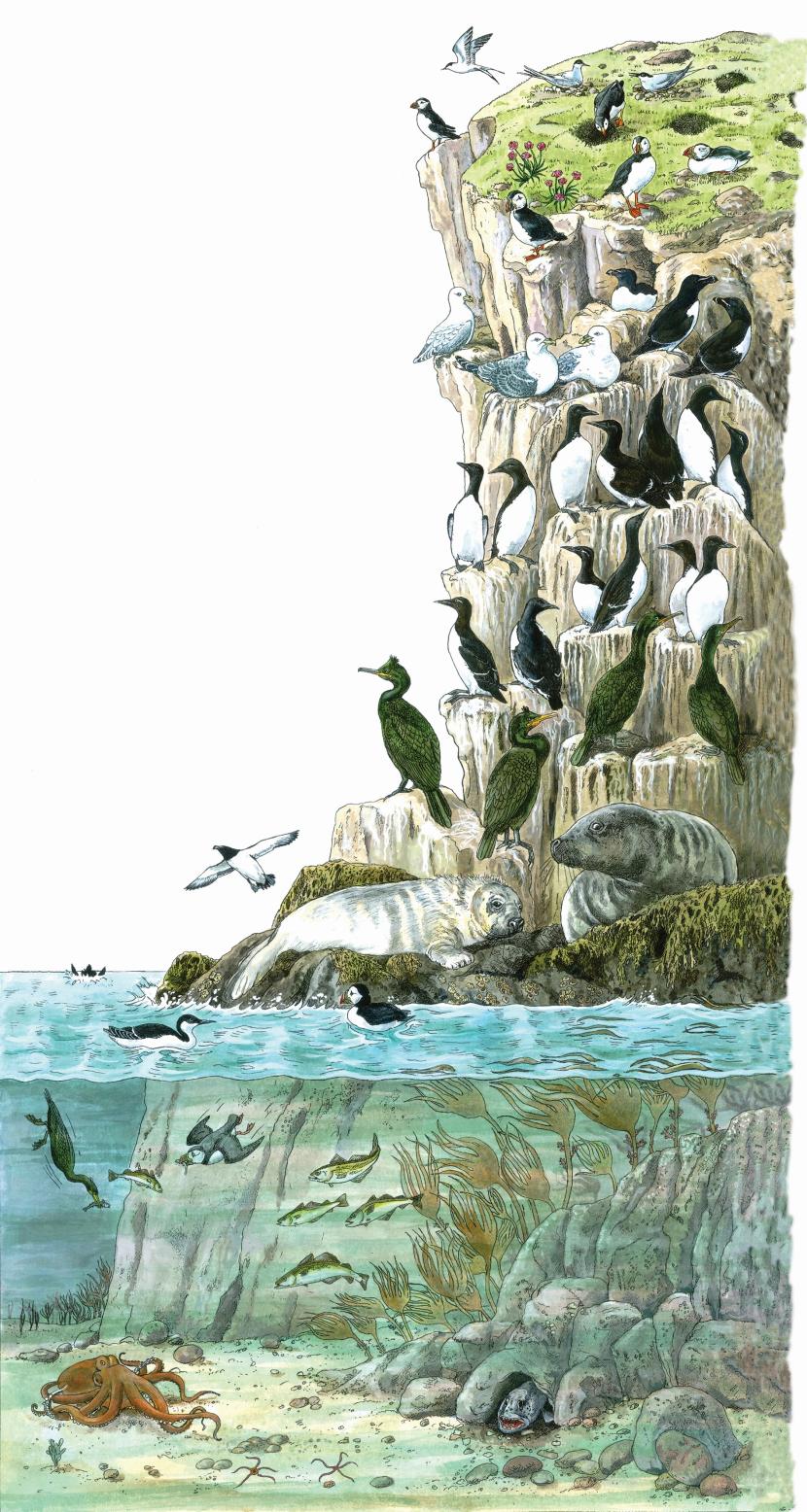

The island is made up of greenstone (olivine-dolerite), forming the high west cliffs which reach 45 metres in height. These cliffs provide perfect breeding ledges for cliff-nesting birds. It slopes from the west cliffs to shallow rocky shores on the east.

The whole island is covered by a shallow layer of soil and maritime grassland; a perfect place for burrowing puffins and groundnesting birds.

The island is a safe haven for the thousands of seabirds as there are no mammalian predators such as rats and foxes that would predate eggs and young. The nutrient-rich seas are excellent fishing grounds for sprats, herring and sand eels – food sources for the seabirds and seals.

The island has a deep cultural history spanning 1,000 years with early Christianity dating back to the seventh century.

In more modern times, lighthouses played an important role for navigation through the Forth with Scotland’s first ever lighthouse built on the island in

1634.

Cliff nesters

Guillemot

Known as the ‘Northern penguin’, guillemots breed in large colonies laying a single egg on cliff ledges. Adults return to breeding ledges in March and will be there until July when the flightless chicks take a leap of faith from the cliffs, before spending the winter out at sea.

Guillemots, along with their close relatives the razorbill and puffin, are excellent divers. Using their wings as flippers they can dive to depths of 200 metres in search of prey.

Razorbill

Razorbills are shy birds and often breed in individual pairs tucked away in nooks and crannies.

Like the guillemot they lay a single egg directly on to the bare rock. They don’t build a nest as the egg has a hard shell and is pear shaped to minimise the risk of it falling off ledges.

Above and below

Puffin

The island’s most numerous and iconic seabird, puffins arrive back on land in early April to find their lifelong mate and their burrow.

The female lays a single egg with both parents taking turns to incubate for 40 days. It will be a further 40 days before the chick leaves the safety of the burrow and makes its way to the sea, where it instinctively knows how to dive and catch fish on its own.

Puffins are able to carry more than one fish at a time, an efficient way to feed hungry chicks. Some have been known to hold over 60 fish in their bill at once. Having small barbs in the roof of their mouth enables them to hold onto their catch whilst hunting for more.

Puffin lifecycle

- Return in late March

- Egg laying mid-April

- First chicks hatch late May

- First chick fledge in early July

- Last chicks depart early August

- Mid-August all adults gone and do not return until next March

Large gulls

The Isle of May has three different large gull species breeding: herring, lesser black-backed and the larger great black-backed gull.

All build a nest on the ground from vegetation and seaweed as well as any rubbish they find that looks good for nest material. They lay between one and three eggs.

Both adults will incubate and feed the young, bringing back both fish and scraps from landfill sites 30-40km away on the mainland.

Terns

Arctic and common terns breed here every year. Sandwich and roseate terns only breed occasionally but can often be seen flying over. Terns are the last of the breeding birds to arrive as they have the furthest to travel from their wintering grounds.

Arctic terns have the longest annual migration of any creature on earth, wintering in the Antarctic before flying back to the Northern hemisphere to breed in our summer. One tracked bird clocked up 100,00km in one year!

Eider

Male and female eiders have different plumages. Colourful males display to females, throwing their heads back and making a ‘wooo’ call to attract a mate.

The well-camouflaged female makes a cosy nest lined with down. Once the chicks hatch the female walks them to the water to start feeding, forming crèches with many females looking after a number of ducklings.

Along the coast

Shag

A close relative of the cormorant, shags have a green iridescence to their feathers, displaying their shaggy crest during the breeding season. They are comical to watch when nest building, carrying a variety of materials from seaweed and grass to old rope and rubbish that is found around the shore. They often steal material from their neighbours.

Fulmar

Fulmars spend long periods soaring low over the sea in search of food, feeding on fish, plankton and carrion. They have a great sense of smell and can locate rotting flesh up to three miles away. They nest on ledges and crevices at the tops of cliffs.

Fulmars are almost gull-like but are related to the albatrosses. They have specialist tube noses and fly with very stiff wings, with shallow wingbeats, gliding and banking over the cliffs.

Kittiwake

Kittiwakes are the true ‘sea-gull’ of Britain spending all their life around coastal waters, venturing as far as Greenland and Canada during winter. They arrive at the island in early spring, pair bonding on ledges and calling their name “kittiwake” loudly. Their nests are made of dead grass and mud, just a small bowl stuck precariously on cliff ledges.

Under the sea

The underwater reefs are covered with mosaics of barnacles, tufts of wrack and on the western cliffs, mussels. The rock surfaces and crevices harbour sea anemones and velvet and edible

crabs. Cold waters from the Arctic influence the marine species that live around the Isle of May. Both ends of the island experience strong currents on the incoming and outgoing tide promoting the growth of filter feeders and soft corals. Forests of kelp plants shelter many other species, including fish, octopus and crabs.

Grey seals

Grey seals can be seen around the island throughout the year especially at low tide at the Maidens and Rona. Numbers increase dramatically in early autumn when females prepare for the pupping season.

The first pup is usually in late September. Over 2,200 will then be born between October and December.

Females move up the island spending three weeks with the pup feeding and protecting them. Males will follow and defend a small harem from other males, mating with the females when ready.

After three weeks suckling rich fatty milk, the pup triples in weight and moults its white coat revealing its darker waterproof coat. It is now independent, ready to learn how to find fish and feed itself.

The UK holds over 40% of the world’s population of grey seals with the island having a high proportion of that total.

May Time

- 669 AD St Ethernan dies. His shrine on the May attracts monks and pilgrims.

- 1145 King David I founds a monastery on the island to pray for the souls of kings.

- 1320 Although the monks have moved to the mainland, a candle still burns on the shrine.

- 1500 The monks welcome half a million pilgrims including King James IV on a picnic.

- 1550 The island is sold and the ruined priory is turned into a tower house.

- 1636 Scotland’s first lighthouse lights its beacon.

- 1715 300 fleeing Jacobites are marooned for eight days without food

- 1730 John Wishart, the last villager, is buried on the island

- 1816 Robert Stevenson’s lighthouse replaces the beacon

- 1844 The Low Light adds its signals to help sailors avoid the North Carr rocks.

- 1886 The Main Light is powered by electricity rather than by oil. The South Horn and engine room are built.

- 1914 The May becomes a naval base guarding the entrances to the Forth in both World Wars.

- 1938 The North Horn is built. The foghorns are powered by compressed air from storage tanks.

- 1956 The island becomes a National Nature Reserve

- 1972 The lighthouse keepers’ families move to the mainland

- 1989 The Main Light is automated and the last lighthouse keepers leave the island. Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) take ownership of the island.

- 2016 Main Light is converted to solar power.

For more information and to keep in touch:

Email: [email protected]

Isle of May blog

@isleofmayNNR

Find out more on

- Visiting the reserve

- Isle of May NNR map and guidelines

- About the reserve

- Getting involved

- Visit more of our nature reserves

Photographers (in alphabetical order): Ella Benninghaus, Chris Cachia-Zammit, Lorne Gill/NatureScot, Sam Oakes, Bex Outram, David Steel. Illustrations: Ross Associates.

Early history – A Pilgrim’s Haven

Excavations have revealed an amazing story of 1000 years of Christian community – the island was an important centre for early Christianity.

A missionary named Ethernan ministered to the Picts of Fife from the Isle of May. He eventually died and was buried on the island in 669 AD with the place of burial attracting many pilgrims. Some died here and were buried in the sacred soil.

A small stone church was built around 900 AD replacing an older timber church. Between the 600s and 900s many pilgrims were buried in stone-lined cists – their bones showed most had been seriously ill. In 1145, King David I founded a new monastery with 13 Benedictine monks. The monks built a bigger church and cloister with income from the fisheries and estates surrounding the Forth. They introduced rabbits to the island.

Around 1300 a man in his 20s was buried in front of the high altar. Before burial a scallop shell had been placed in his mouth. This was the symbol of pious pilgrims who travelled to the great shrine of St James at Compostela in Spain. This man may have made that pilgrimage, returned to his monastery on the island and died soon after.

History – A beacon of hope

A lighthouse has been operating on the island since 1636 in which year King Charles I granted a patent to erect a coal-fired beacon and collect dues from shipping for its maintenance. The light was a three-floored stone structure surmounted by an iron fire basket in which burned a coal fire to serve as the illuminant across the sea. The coals were hoisted in a box and pulley. Three men were employed the whole year round attending to the fire which consumed about 400 tons of coal a year. In 1790 a lightkeeper’s entire family was suffocated by fumes except for an infant daughter, who was found alive three days later.

Despite the fact the light was regarded in its time as one of the finest in existence, the light was sometimes hard to recognise. On 19 December 1810 two Navy ships were wrecked near Dunbar because the light of a mainland lime kiln on the coast had been mistaken for the navigation light on the Isle of May. In 1814 the Northern Lighthouse commissioners purchased the island and the construction of a new lighthouse was soon underway.

History – A Stevenson masterpiece

The main lighthouse was built in 1816 and was designed by Robert Stevenson. Standing 24 metres high the building could accommodate three lighthouse keepers’ families. The light produces two flashes every 15 seconds and has a range of 44 km in good visibility.

Over the years, many changes have taken place including conversion to electricity in 1883. This made it Scotland’s first electrically powered lighthouse. However, due to the high expense, it was converted back to oil in 1924. Two fog horns were constructed: South Horn in 1886 and North Horn in 1938. These were powered by compressed air generated from the island’s power plant at Fluke Street. You can see the cast-iron pipe on the ground running north and south across the island but the horns have not sounded since 1989.

In August 1972 the lighthouse became listed as a ‘Rock Station’ meaning that families could no longer live on the island, leaving only three lighthouse keepers in attendance. Eventually, with the onset of modernisation the lighthouse went fully automatic in March 1989 and the lighthouse keepers left for good. During the winter of 2015 the diesel generators were removed and the lighthouse is now powered by a series of solar panels.

History – Light as a feather

The ‘Low Light’ on the east side of the island is a small lighthouse that opened in April 1844 to act in conjunction with the main lighthouse. As both lights align, ships could avoid the treacherous North Carr rocks some seven miles north of the Isle. However, when the North Carr Lightship was established in 1887, there was no longer a need for the Low Light and it was decommissioned.

In 1934 a group of young Scottish ornithologists set up the Isle of May Bird Observatory. This was the first bird observatory in Scotland and only the second in the British Isles. It is administered by a charitable trust and manned by up to six visiting volunteer observers between March and November.

The volunteers monitor, count and record all bird migrants. They also ring birds using the four specialist Heligoland traps which you can see on the island.

History – Fluke in the Forth

Fluke Street consists of former lighthouse keepers’ cottages and outbuildings built in 1886. The buildings form the main living accommodation on the island for NatureScot staff, researchers and volunteers.

The Isle of May is internationally important for its famed for its research. It is one of four strategic seabird research sites in the UK. Seabird research has been carried out on the island since 1966 and seal research since 1982. This long term research helps us understand the effects of climate change on the seabirds and seals in relation to their diet and distribution.

At the height of the season up to 18 people live and work here. We try to be as self-sufficient as possible. The accommodation has running water (pumped from the island’s well), solar energy for power and even an electric vehicle to carry supplies!

Island living can be challenging but extremely rewarding as we share the place with the spectacular wildlife.