Hermaness NNR - visiting the reserve leaflet

Welcome to Hermaness National Nature Reserve, managed by NatureScot

Seabird city

In the summer the cliffs of Hermaness are home to 100,000 noisy and bustling breeding seabirds. Approaching these magnificent cliffs across the dark moorland, you get no indication of what is to come – no sound of crashing waves, no view of the sea – and you will be literally stopped in your tracks as you reach the precipice.

The exposed, jagged cliffs, which tower up to 170 metres above the foaming sea, are teeming with life: gannets, puffins, fulmars, guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes and shags are among the dozen or so species. The gannets alone number about 30,000 pairs, making this one of the top six breeding sites in the UK for this massive, elegant bird.

Smashing but smelly

There are several gannetries along the reserve’s western coast, one of the best being at Neap which you pass on the Saito Trail. You will probably smell and hear the birds long before you see them: the fishy stench of the guano, and a gurgling, gargling cacophony. Then, as you round a small headland, you see them: thousands of gannets squabbling over territory on the white-stained cliffs.

Watching the birds dive is a remarkable spectacle. Their amazing vertical descents reach speeds of more than 60mph, evolution having equipped

them with skulls that can absorb the shock of smashing into the water at such a velocity.

Clifftop clowns

Puffins, or ‘tammie norries’ as they are known in Shetland, grace the cliff-tops from mid-April to early August.

Landing clumsily with their colourful, parrot-like beaks full of sand eels, and popping in and out of their burrows in the soft turf, they seem almost

comical. Having spent the winter at sea, travelling as far west as Newfoundland, puffin couples usually return to the same burrow each spring.

They can dig these out using their powerful legs and beaks, although they often use old rabbit burrows.

Land of the giants

Hermaness, or ‘Herma’s headland’, is reputed to be named after a mythical giant who fought with a neighbouring giant, Saxa, over a beautiful mermaid. They hurled enormous boulders at each other over the Burra Firth, one of which landed in the sea and became Out Stack, Britain’s most northerly point. In reality, Hermaness is more likely to have been named after an early Norse owner.

The main rock type at Hermaness is gneiss, created under immense heat and pressure more than 450 million years ago. These ancient rocks, with pink veins of granite running through them, have been sculpted into incredible shapes by the power of the Atlantic, creating stacks, caves, natural arches and steep-sided clefts known as geos.

Riot of colour

Salt-tolerant plants such as angelica, red campion, thrift, Scots lovage, spring squill and lesser sea spurrey cling to cliff ledges, bringing an ever-changing mosaic of colour to this harsh environment. The more sheltered, eastern side of the peninsula is home to three species of hawkweed that are unique to Shetland.

Inland, the bulk of the reserve is rough moorland– blanket bog and peaty pools that provide a habitat for heather, cottongrass, blaeberry, sphagnum mosses and colourful orchids. Golden plover, dunlin and snipe nest here, along with great and Arctic skuas (though the latter has declined significantly in recent decades). A few pairs of rare red-throated divers – called ‘raingoose’ in Shetland – also breed on secluded moorland lochans.

Pirates of the airways

On the moorland in summer, you might encounter great skuas, known locally as ‘bonxies’. Protective of their nests, they divebomb passing walkers. They go for the highest point, so hold your arm or a walking pole above your head, although they rarely make contact.

They are more of a threat to their avian neighbours, as they prey on other seabirds or harry them until they give up their fishy meals.

In 1831, there were just three pairs of great skua, but naturalist Dr Laurence Edmondston set up a protective programme, starting a long history of conservation that continues today. Numbers rose to almost a thousand breeding pairs (making Hermaness the third largest colony in the world), but the devastating outbreak of highly pathogenic avian flu in 2022 caused a crash in the population.

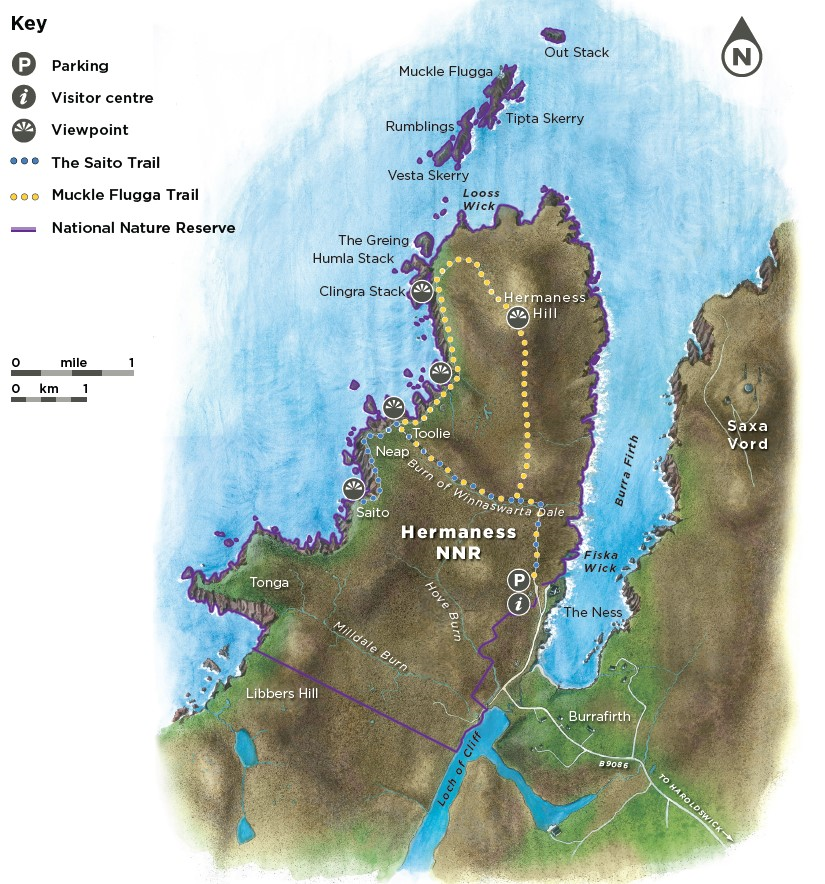

Hermaness NNR is 3 miles/4.8km north-west of Haroldswick on Unst. It takes two ferry journeys to reach Unst from Shetland Mainland. The first is from Toft to Ulsta on Yell. This is followed by a 17 mile/27.4km drive north to Gutcher for the ferry to Belmont on Unst. There is a limited bus service between Lerwick and Haroldswick. Check the ZetTrans website for an up-to-date timetable. There are 2 bike stands. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2022.

Need to know

Please keep dogs on a lead to avoid disturbing nesting birds and livestock. Please keep to the paths to avoid disturbing birds and damaging the fragile peatland. Please take care along the cliff edge and steep sea-facing slopes. Please follow requests on any notices you see.

Find out more

- Tel 01463 667600 or email [email protected].

- Follow @ScotlandsNNRs.

- Support this NNR at www.nature.scot/donate-nnr

- Visiting the reserve and about the reserve

Reserve map

Trails

The Saito Trail

Follow the path through the wild moorland interior to the spectacular cliffs on the west coast. Head south along the coast for breathtaking views of the thronging gannet colony.

Muckle Flugga Trail

A circular route across wild moorland, along cliff tops and over Hermaness Hill. Enjoy breathtaking scenery, views to Muckle Flugga and pass the

remains of the old signal station.

Find out more on

- Visiting the reserve

- About the reserve

- Visit more of our nature reserves