NatureScot Science Quarterly Newsletter - Issue 38 - February 2022

Welcome from the SAC Chair

Pete Higgins

Last summer, the agreement between the SNP and Scottish Green Party set out an ambitious programme of work to improve the protection of Scotland’s seas. Over the next five years NatureScot will be continuing to work on ensuring that existing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are well-managed and that sensitive seabed habitats identified as ‘Priority Marine Features’ (PMFs) outside the Scottish MPA network also receive the protection that they need. Alongside work relating to capping inshore fishing effort, perhaps the most ambitious aspect of the agreement for marine biodiversity is the commitment to designate 10% of Scotland’s seas as ‘Highly Protected Marine Areas’. These will be areas that support nature’s recovery and help build resilience to climate change.

The evidence we get from marine monitoring work underpins the advice provided by NatureScot on a range of different activities and developments, including on MPAs and PFMs. There are standard techniques that NatureScot has used for some time, such as grab sampling and diver surveys, but the monitoring articles in this edition explore how new technologies are helping to improve our understanding, including through the use of deep learning and drones. Closely related to this work is a subject that receives relatively little attention – how we can best manage marine biodiversity data in Scotland. This is critical to ensuring that good quality evidence is available to support those making decisions relating to the use of our seas.

The hotly anticipated growth of offshore wind is also creating a boom in science to inform marine plans and decision-makers. The recent ‘ScotWind’ leasing round from Crown Estate Scotland triggers the biggest round of offshore wind development in the world to date! Seventeen new sites have been announced, of which ten are likely to be for floating wind technology. A spate of research funding is flowing through public bodies and research councils at the UK and Scottish levels, much of which should help us minimise impacts on Nature. The big challenge for NatureScot is to strike the right balance between enabling the Just Transition to Net Zero and ensuring a nature-rich future. The articles below include an overview of the development of our marine energy team and its scientific endeavours since 2010, reflections from new team members, and insights from some projects in which NatureScot is involved. Whilst there are undoubted additional challenges in carrying out habitat restoration underwater, there are nevertheless a growing number of projects around Scotland tackling this head on. In the penultimate article in this edition, we look at recent experience with native oysters - once abundant in many parts of Scotland.

As we look towards the development of the new Scottish Biodiversity Strategy in 2022, the recovery and regeneration of nature will be high on agendas between now and 2030. The Biodiversity COP15 to be held in Kunming in the summer will raise the profile of all this.

I vividly remember reading Sir Alastair Hardy’s ‘The Open Sea’, in the Fontana New Naturalist series, as a young environmental science student. It was the Preface to the book that really caught my imagination, where he seeks to engage the reader’s attention by pointing out that we tend to look over the sea rather than into it, mentally changing our perceptions by asking us to imagine it turned through 90 degrees, and as a great ‘curtain' hanging in front of our eyes. He encourages us to imagine holding our breath and being able to run into it for a few moments before having to come back out.

Advances in marine science, unheard of on Hardy’s days, now allow us to know and understand more of our seas and oceans than ever before. The development of a range of technologies to gather and analyse data allow us to assess the status of species and ecosystems, and to monitor damage and restoration. The articles in this issue of the NatureScot Science Newsletter exemplify this perfectly. In the penultimate article in this edition, we look at recent experience with native oysters - once abundant in many parts of Scotland. If all of this is not enough, read the end piece by Jane Reid, a member our Scientific Advisory Committee, writing from her research base in Trondheim, Norway. Jane reinforces the importance of cutting-edge science in helping us understand what is happening in the marine world – and how we must take action to improve matters. It is so pleasing to see Jane appreciating the work of NatureScot’s marine and coastal staff. With the advances in technology and the many forms of support available for scientific research, it is easy to overlook the importance of ingenuity, talent and energy in the people undertaking the work. We are so fortunate to have such dedicated people working in Scotland – and further afield.

Making the most of our marine biodiversity data

Rona Sinclair and James Dargie

Access to robust data is fundamental to develop nature-based solutions and adopt an ‘ecosystem services approach’ to tackle the twin nature and climate crises. NatureScot relies on access to complete and highquality marine biodiversity datasets to fulfil its key statutory functions; underpinning its advice to the Scottish Government on marine policies and management decisions. A strong scientific evidence-base is essential to support a Blue Economy. One of the biggest challenges is accessing, collating and interpreting the data required at appropriate spatial and temporal scales to make informed decisions. The commitment to open up as much marine biodiversity data as possible is detailed in the UK Marine Science Strategy, and includes wider access to industry data.

Recent technological advances which have made marine biodiversity data collection more accessible to citizen scientists; and the expansion of offshore activities, that are required to collect biodiversity data for characterisation and compliance monitoring, have led to a growing, substantial data resource. Independently, these datasets may have temporal and spatial limitations, but when combined with broadscale survey data, collected by government bodies, they provide an invaluable resource for a range of analyses to inform conservation and policy needs. Data providers have become increasingly willing, and in some cases compelled, to share information. NatureScot’s work with coastal community groups across Scotland has led to the co-production of a community-led marine biodiversity survey and monitoring handbook. It is anticipated that significant quantities of new types of biodiversity and physical data will be collected by the volunteer community and work is ongoing to ensure that these data contribute to the wider marine evidence base.

There are various infrastructure improvement projects underway to develop systems and automated data workflows to aggregate data collected by: public sector organisations, industry and NGOs/ citizen science initiatives. For example, the re-development of ‘Marine Recorder’ into a modern cloud-based platform with geospatial functionality, including a public interface, will significantly improve the management and accessibility of seabed species and habitat data.

A review of the Scottish marine biodiversity data landscape

NatureScot is leading a stakeholder focussed project to develop and examine existing data flow pathways and infrastructure supporting the collation and use of marine species and habitat data Scotland. The review has gathered information on: barriers and issues encountered by data provides/end-users, and where improvements are necessary to enhance availability and accessibility of high-quality marine biodiversity data. This work is an adjunct to the Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum (SBIF) Review of the Biological Recording Infrastructure in Scotland published in 2018.

The marine data review has identified the following top three priority stakeholder needs:

- Unification and/or rationalisation of databases and portals with clear guidance on where to submit datasets and the dissemination opportunities

- Unduplicated data that is easily accessible for use in collations

- Improved access to industry survey data

The work of the UK Marine Environmental Data and Information Network (MEDIN) has ensured that the marine sector is at the forefront of advances in geospatial metadata creation and data sharing; now ahead of its terrestrial counterparts. Organisations involved in collecting marine environmental data in UK waters are encouraged to submit data to a relevant MEDIN Data Archival Centre via affiliated data management systems such as the new Marine Recorder Online, the Joint Cetacean Data Programme (JCDP) Portal and other established data repositories.

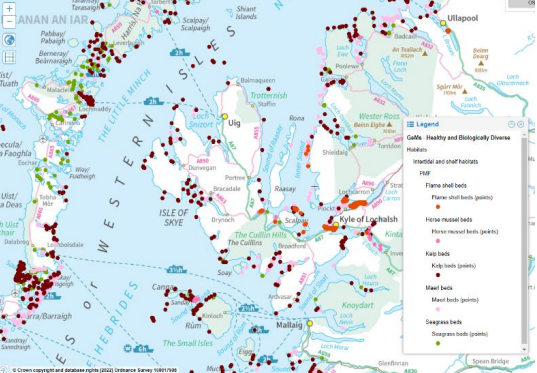

Well established workflows make Scottish Priority Marine Feature datasets publically accessible on Marine Scotland’s National Marine Planning Portal (NMPi) as a contribution to the evidence base for use in planning decisions and casework advice. Marine species records are also served to the NBN Atlas.

Marine renewables industry data

Improving access to marine industry data in Scotland is being kick-started through a Developer Data Archival project contracted by Marine Scotland. The project will produce guidance of where to mobilise and archive data for the offshore and marine renewables industry, within appropriate databases and MEDIN archive centres.

NatureScot has been working with colleagues at Marine Scotland and Crown Estate to discuss anticipated benefits and rationale for requiring developers to submit seabed species and habitat data into the Marine Recorder. The aim: to make biodiversity monitoring data from ScotWind and other developments publically available to inform future marine planning.

Marine Recorder re-development project

‘Marine Recorder’, for the last 20 years, has been the home of seabed species and habitat data across the UK. Where commissioned by NatureScot, the other Statutory Nature Conservation Bodies and others such as the Marine Conservation Society’s Seasearch initiative. The current system relies on ageing software architecture and local desktop installations and has reached storage capacity. The system is not fully compliant with data guidelines published by the MEDIN, nor has it kept pace with the means to service onward publication destinations such as MEDIN Data Archive Centres or NBN Atlas. It fails to handle complex spatial geometries. The time for change is now.

The new Marine Recorder Online application supports many key improvements including:

- The streamlined mobilisation of data - allowing direct harvesting by the MEDIN data archive centre network.

- Ability to handle complex spatial geometries.

- Compatibility with widely accepted UK marine data standards, and direct linking to associated discovery metadata.

- Allow the tagging of records with conservation status like Scottish Priority Marine Feature or Habitats Directive Annex I habitat making record identification for conservation designation and management purposes easier.

- An ongoing relationship with the developer to provide user support to facilitate further development and maximisation of the applications’ life-span.

We hope the project secures significant Marine Scotland funding input in 2022-2023. Likewise, due to our ongoing relationship with the developer there may be scope to develop a bespoke simplified interface to support user from community and citizen science groups. Thus, supporting the Scottish Community-led Marine Monitoring Project.

Marine energy - energising science

Erica Knott

In 2010, NatureScot decided to create a team to provide advice on marine energy – including offshore wind, tidal stream and wave projects – and the possible impacts on species and habitats in marine and coastal environments. In the ensuing period there has been shift of focus on renewables. However, the overarching mission of the team is to examine: what we know, are learning; how best to share knowledge; and identify and fill gaps of our own and other knowledge.

We provide advice on policy development, research, guidance and casework across a wide range of aspects: marine birds; marine mammals; fish species including diadromous fish; benthic; underwater noise; landscape and coastal impacts; and coastal change. There has been a shift in focus to primarily offshore wind since the early 2010s. We have been involved in all Scottish offshore wind farms to date including: the first - Robin Rigg in the Solway, the clusters of developments in the Moray and Forth and Tay estuaries as well as the world first demonstration floating arrays at Kincardine and Hywind and the demonstrator array site in Aberdeen Bay.

We have been instrumental in the creation of new and existing tools to predict impacts for Environmental Impact Assessment / Habitats Regulations Appraisal, including collision risk modelling, population models and the consideration of cumulative impacts. We have also developed coastal character assessment guidance as well as contributing to the first study on the public perceptions of offshore wind in Scottish waters.

Our work will continue long term - both the recent ScotWind announcement and the next ‘Contract for Difference’ auction will likely support tidal stream projects. Thus, our work will continue with increasing focus on what these industries will deliver for net-zero targets and the Scottish economy. However, as there are still likely to be environmental impacts, our job will aim to minimise these. We will be increasingly required to provide advice on compensation measures highlighted through derogation cases. These will be complex and challenging as we need to take account of changes to species and habitats through climate change and the predicted impacts from developments.

It is fair to say the team recognise that our work is innovative; forges synergies between research and evidence, casework and guidance; and creates the opportunity to build good relationships through collaboration; but also allows for our own staff to demonstrate leadership in research. In the next few articles, members of the team provide a flavour of the work we are involved in. New members provide their first impressions; a review of lessons learned and our contributions in the area of underwater noise impacts; and the current development of a suite of guidance to help inform impact assessments of marine birds.

Science, policy and industry working together in Scotland to develop impact assessments for offshore wind farms and marine birds.

Alex Robbins

The above is the title of a presentation at the World Seabird Conference, delayed and held in an online format in October 2021. It is also the title of a presentation for the Conference on Wildlife and Wind planned for April in the Netherlands. Why might you ask are we providing the same talk at these conferences?

We are keen to highlight that NatureScot, alongside Marine Scotland, have been considering what we have learned from the first round of offshore wind farms in Scottish waters and what might be the next steps for the next round recently announced and known as ScotWind. Scotland has 24 species of breeding seabirds; however, of the 11 we currently produce trends information on, 9 have shown sustained declines in the last 20 years. The reasons for these declines are complex and we need to consider whether the development of offshore wind projects will substantially add to these declines.

In February 2020, NatureScot held a workshop with developers and advisers to identify necessary updates to existing tools and guidance for the next round of offshore wind and tidal stream applications. In this workshop, we identified a suite of 11 guidance notes for marine bird impact assessments to assist new projects throughout the life-cycle of development. The suite of notes includes: methodology for baseline surveys, population modelling, identifying connectivity of breeding seabird colonies and collision risk modelling.

Findings from the development of a new assessment tools such as the stochastic collision risk model have informed some of these new notes. Findings from postconsent monitoring of operational wind farms have also been incorporated to help inform development. An exciting development of the post-consent monitoring discussions has been the collaboration with SSE, Microsoft and Avanade in the development of remote, automated monitoring of puffins at breeding colonies – Project Puffin.

Our suite of guidance notes will be ready for the next round of applications. Importantly, we recognise that it will be an iterative process to consider: the emerging evidence based on monitoring newly operational wind farm, new research and ongoing tool development.

Offshore wind development – clearance of unexploded ordnance (UXO)

Caroline Carter

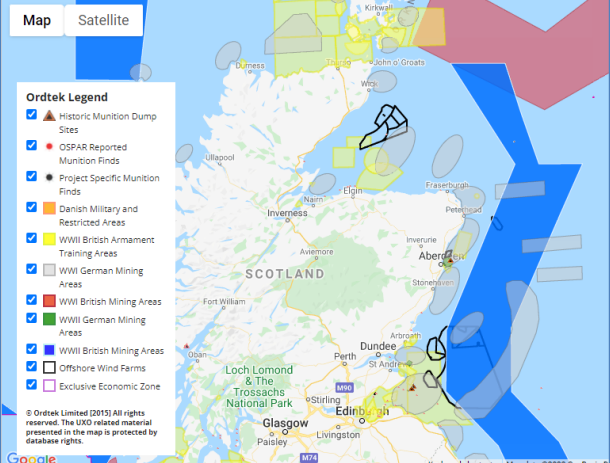

A large volume of explosives were left undetonated in the marine environment after World Wars’ 1 and 2. This includes: sea mines, torpedoes, depth charges, artillery projectiles, rockets, and land service ammunition (for example, mortars, grenades or small arms ammunition). Figure 1 shows there is a fair bit of overlap between offshore wind developments and potential UXO presence.

Prior to construction, the developer needs to check the site and cable route for any UXO present, and if found, proceed with clearance. Safety, project design and/or time constraints mean the usual method of clearance is to detonate the device in situ. This has historically involved placing relatively large explosive donor charges next to the UXO, to detonate any live explosive material left in the device.

The main concerns from underwater explosions on marine life are: (i) physical trauma; (ii) auditory impairment; and (iii) behavioral disturbance such as displacement from habitat, and interruption of feeding, mating and resting. Additionally, the resulting crater damage to the benthic environment could release harmful chemicals into the marine environment.

The military have been clearing UXO for decades, however, it was never assessed through the marine consulting process. Our understanding of potential risks is ever evolving. Previously, it was thought that the JNCC explosive guidelines would mitigate any harm to marine life. It advised a minimum 1km radius of no animal observations to initiate detonation. However, new findings suggest a 10km minimum radius is required to prevent auditory injury; JNCC are currently updating their explosive guidelines. Additional mitigation methods include the use of acoustic deterrents or noise abatement systems such as a bubble curtain.

Alternatives to high order detonation are becoming commercially available. The intention is to disintegrate or burn out the explosive trigger of the UXO rather than complete destruction. The burn out (deflagration) method is subject of an ongoing research project run by the National Physical Laboratory (NPL); starting in 2019. This method, so far, produces significantly less noise than high order detonation. Tests sites will move from submerged quarries to offshore sites in 2022. NatureScot currently advises that low noise alternatives are preferable; mitigation of impact needs to be precautionary and based on worst case scenario of high order detonation. Noise monitoring of clearance activity also needs to be conducted to further our knowledge of the impact of UXO clearance on the marine environment.

Offshore wind development – lessons learned from the Moray Firth

Caroline Carter

When I joined NatureScot at the tail end of 2012, the Moray Firth offshore wind developments were already at the application stage with their accompanying EIA reports. These types of developments, like most we deal with in the marine environment, are novel. The impacts are largely unstudied and unknown. We have learned a lot since then; my focus is predominantly on underwater noise and marine mammals but the same degree of learning can be said for other receptors i.e. birds.

Much of the EIA has been assessed using proxy information and models; the novel considerations presented uncertainty and barriers for consenting. Regional Advisory Groups (in the Moray Firth MFRAG; Figure 2, and Firth of Tay FTRAG) were set up to combat these issues. This collaborative approach allowed for discussion of unknowns and led to an agreement on proposed methods. For marine mammals, one of the key impacts was injury/disturbance risk from impact piling.

We were fortunate in the Moray Firth, because the key marine mammal species were already monitored by the University of Aberdeen Lighthouse Field station (UALSF). An early decision was for the UALFS to formalise a Strategic Marine Mammal Monitoring Plan (MMMP) designed to build on the existing data. This was jointly funded by all the developers in the region, and included the targeted collection of data, pre-, during, and post-construction.

Historically, mitigation of harm to marine animals relied on a team monitoring the risk zone to halt ‘piling’ until the area was clear. This methodology posed many risks due to uncertainties in animal detection. Within MFRAG, we agreed to trial acoustic deterrents to move animals out of the injury zone. Collectively, we developed ‘The Piling Strategy Agreement’. This strategy required monitoring the abundance and distribution of SAC species like the Harbour Seal and Bottlenose Dolphin. Also, to monitor the reaction of harbour porpoise to the Acoustic Deterrent Device (ADD) mitigation and piling activity. This was a first for Offshore Wind Farm (OWF) development in the UK.

So, what have we learned from this process and monitoring regime? Well, lots!

- The RAG worked well; it was a mechanism to look at the area and issues in a strategic manner, and helped secure developer buy-in to the mitigation and monitoring proposed.

- Defining post-consent monitoring has been challenging, as there are multiple developments in the same area, all developed sequentially.

- There was no barrier effect for Bottlenose Dolphin in their key areas of foraging/travelling.

- The ADD mitigation protected Harbour Porpoise from the piling injury risk.

- In addition to ADD and piling noise disturbing/displacing porpoise, there was a displacement effect from general construction vessel traffic.

- There was no observed effect on Harbour Seals from the construction activity - so far.

- Porpoise displacement to construction activity reduced over time, so they were not displaced to the same extent from the second development than they were from the first.

The noise monitoring during piling found an unexpected noise level pattern that is thought to be particular to pin piles (as opposed to monopile) so the foundation type has a bearing on the noise profiles. We’ve learned much from the Moray Firth, but also that this knowledge may not be directly transferable to other areas/development types, context is key.

There remains the need for research to reduce uncertainties and consenting risks. There are many forums that co-ordinate the research needed to fill gaps, for example through ScotMER (MS led), the Crown Estate and ORJIP. We are continuously learning; our EIA models are evolving with increasing complexity and input data needs.

There are other research programmes associated with different OWF foundation types, for example, suction buckets (Aberdeen, Seagreen) and small scale floating wind (Kincardine; Hywind) which will be a good starting point for the upcoming ScotWind projects. The progress has been parallel for all other key receptors. However, we are beginning to look at ecosystems effects, rather than only receptor, as the marine environment is highly interconnected; this has to be the way forward. Thus, our advice is not static. We must be flexible so we can reflect upon new knowledge. This makes casework responses tricky as we cannot simply Figure 2: MFRAG cluster OWF developers 10 rely on what we’ve concluded before. More collaboration and learning will continue in this extremely fastmoving, developing and exciting area of marine energy

Marine energy: perspectives from new team members

Caitlin Cunningham, Malcolm Fraser and Jenna Lane

Malcolm, Caitlin and Jenna are recent additions to the Marine Energy team, which sits within Sustainable Coasts & Seas. Within the Marine Energy team, work primarily involves coordinating NatureScot’s casework responses to marine renewables – offshore wind (fixed and floating), wave and tidal stream. This includes advising on the impacts of marine energy casework on the marine environment around Scotland, covering pre-application engagement, Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) scoping, marine / s.36 licence applications as well as Habitat Regulations Appraisal (HRA) and European protected species (EPS) licensing.

Malcolm Fraser – Marine Ecology Adviser

I joined the Marine Energy team in June 2021 on a one-year fixed-term appointment as a Marine Ecologist, working two days per week as a backfill for part of an existing post. For the remaining three days I work as an Area Officer in the Forth Area Team.

There’s good energy and leadership in the Marine Energy team – we meet every Monday morning to take stock of where we are, and share our priorities for the week. The Marine Ecologists also meet weekly to discuss technical topics and new publications, or to brainstorm casework issues. It’s been a fantastic team to join, everyone has been very encouraging, available and supportive. I’ve really valued this support as this is a specialist role and very different to the generalist Area Officer role that I’m used to.

The Area Officer role requires an awareness of a huge range of technical topics, but the Marine Ecologist role requires a detailed technical understanding of some of those topics. So whilst I was already fairly comfortable with basic marine mammal biology, and the policy framework around their conservation; I’ve learned much more about how we measure their population status and distribution, the fine details of how they are protected by legislation, and the ways they are affected by noise.

The ongoing highlight of my time in this team is providing specialist advice to Area staff. With support from the Marine Ecologist team, I’ve been able to provide quick and direct advice to Area colleagues around Scotland, including my colleagues in Forth!

Caitlin & Jenna – Marine Sustainability Advisers

We joined the Marine Energy team in October / November 2021, both on fixed-term appointments. Our roles as Marine Sustainability Advisers are developmental opportunities, allowing us to expand our understanding of marine renewables through shadowing, assisting with casework responses and attending relevant training courses and conferences.

Caitlin Cunningham

Since October, I have been working full-time as a Marine Sustainability Adviser. I previously completed a graduate placement working on blue carbon within Sustainable Coasts & Seas, which further developed my understanding of Scottish coastal and marine ecology, habitats and species.

The role of Marine Sustainability Adviser mainly involves collating advice from specialists and maintaining a generalist view of casework. I’ve enjoyed diving in at the deep end with marine renewable casework and helping to write and coordinate our scoping response for Berwick Bank Offshore Windfarm. Whilst the topics can be challenging, everyone within the Marine Energy team has a wealth of experience and are happy to help improve my understanding. The multidisciplinary support I’ve received to develop my learning has been incredibly useful and one of my highlights so far has been the underwater noise training. Prior to this training, underwater noise felt like a mammoth (or whale?) of a subject and I didn’t know where to begin. But the complex topic was broken down and explained in a clear way. Now I feel more confident understanding subsequent technical reports and casework, as well as knowing which issues to flag to specialists.

I’m looking forward to seeing how my journey continues to develop with the Marine Energy team, especially with the exciting news around ScotWind.

Jenna Lane

After a decision to better utilise my marine background, in November I began a split role working half the week as a Marine Sustainability Adviser. I spend the remaining time as a Senior Licensing Officer, having worked in the Licensing team across various roles since 2016. I’ve been amazed to discover how similar the two roles are, with both requiring a generalist approach and both involving the collation of advice. So I have found it easy to settle into the Marine Sustainability Adviser role.

The past couple of months has been both exciting and challenging (in a good way). It’s been motivating to be involved in marine renewable energy work which, in the bigger picture, helps the work towards reaching Scotland’s net zero targets. I’ve been able to put my under-utilised marine biology background to good use and I’ve learned an incredible amount about marine energy and NatureScot’s statutory advisory role. I’ve been surprised by the breadth of marine development impacts on marine and coastal receptors, the complexity of how these are assessed and how many different specialists are involved.

A highlight has been getting involved in user testing for new e-learning modules on offshore wind developed by the Offshore Wind Industry Council. These modules were very comprehensive and interactive and will be invaluable in my role going forward. Another topic I have found particularly interesting has been learning about the Seascape, Landscape & Visual Impact Assessment (SLVIA). I had the opportunity to sit in on a meeting between the relevant stakeholders of the Pentland Floating Offshore Windfarm and I was impressed with the technology we have to visually determine what the proposed wind farm would look like from various key viewpoints and how this interrupts or blends in with the seascape.

Next, I’m looking forward to tackling my first piece of casework for an offshore floating wind farm and discovering the opportunities and challenges on the back of the ScotWind offshore wind leasing announcement.

Embracing new technology in our marine survey and monitoring work

Peter Webster

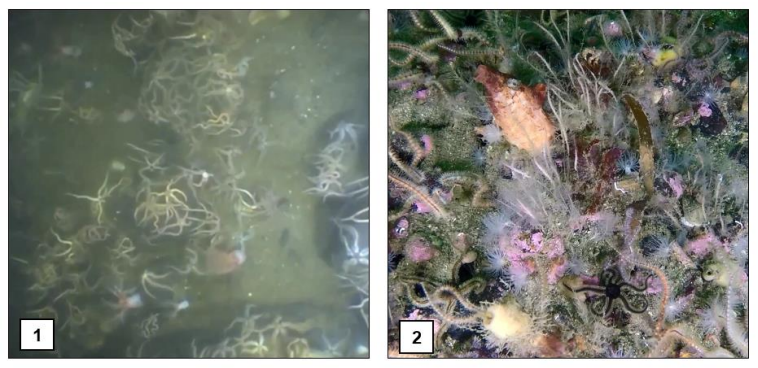

Monitoring and surveying the marine environment comes with a range of challenges which requires a unique set of tools to overcome. Tools we use in our seabed habitat surveys include drop down videos (DDV), diver held cameras, small remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and data loggers to take physical measurements in the water column. Recently, the Marine Ecosystems team in NatureScot was successful in a joint bid with Marine Scotland Science (MSS) to the Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) to upgrade some existing equipment and expand the collective MPA monitoring ‘toolbox’. An upgrade of our ageing underwater diver camera systems will allow us to shoot up to 8k video and 45 megapixel stills, greatly improving the scope of our site surveys. Our drop down system is also being upgraded and will utilize the latest mini action cameras in a deep-water aluminium housing (rated to 250 m depth). Identifying living organisms confidently could be a challenge with some of the older systems but the latest additions will raise the bar significantly. As an example, image 1 is a still captured from the drop video camera in 2013, while image 2 is a still from a DDV survey in 2017.

For our diving work, new lens magnification scopes paired with the high image resolution will let us capture incredibly detailed imagery of organism’s only millimeters in size, allowing for the identification of more species than ever before (see NatureScot Flickr pages).

We work closely with colleagues in MSS to deliver science projects under the Scottish MPA Monitoring Strategy. We bid for time on their research vessel Alba na Mara and collaborate on seabed habitat surveys every year. A significant part of the successful 2021/’22 NRF bid includes upgrading the multibeam acoustic survey systems on Alba and her sister ship RV Scotia, building capacity to deliver on the range of marine conservation policy commitments.

Video ‘screengrab’ stills from DDV surveys in 2013 (LHS) showing brittlestars clearly in abundance but a real challenge to identify other species and from 2017 (RHS) allowing different brittlestar species to be identified plus sea squirts, hydroids and sponges also clearly visible.

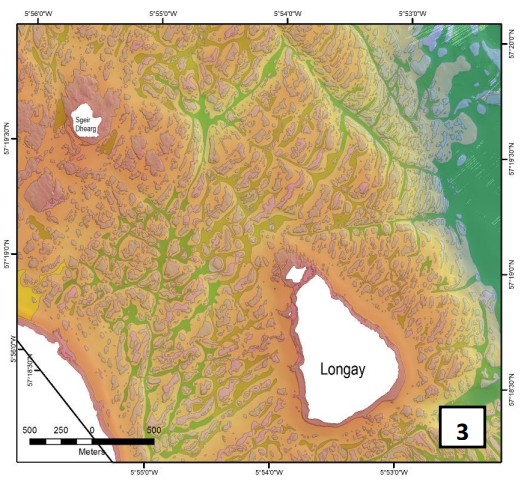

High-resolution multibeam bathymetry products play a key role in mapping the distribution and extent of seabed habitats. The interpretation of multibeam data collected by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) in the Inner Sound of Skye in 2019 (see image 3), helped identify submerged rock drumlins and moraines used by critically endangered flapper skate for egg-laying in the Red Rocks and Longay MPA. Ground truthing of this work in 2021 (see our December blog for more details) using drop-down video systems confirmed the importance of this area and our formal advice to Scottish Ministers on the importance of this site at the end of last year. Other planned ‘toolbox’ additions to the include Baited Remote Underwater Video systems (BRUVS), which can be placed on the seabed or suspended in mid-water to attract fish, other scavengers and larger predators in front of a remote camera. The BRUVs will improve our understanding of fish diversity, abundance and behaviour in the Scottish MPA network.

©Crown copyright [and database rights] 2022 OS 100017908. Reproduced with the permission of the British Geological Survey ©UKRI [2021]. All rights reserved

We are also ordering a number of UAVs (drones) to help survey intertidal areas - precisely mapping algal species, blue mussel beds and adjacent saltmarsh habitats as well as seagrass beds down into the shallow subtidal. Artificial intelligence built into the drones will enable us to accurately repeat surveys to compare the extent and distribution of species over time. The drone can take different camera ‘payloads’ with future options for thermal imaging to support seal counts or Lidar to chart changes in the structure of coastal habitats.

We are also exploring the application of novel analytical techniques with our monitoring work now expected to include the collection of sub samples from sediment grabs for molecular analysis to identify species possibly missed by routine laboratory analyses of sieved samples. Another area of interest is image annotation when our remote video is analyzed with a view to informing future AI processing to avoid laborious specialist review of 100’s hours of footage.

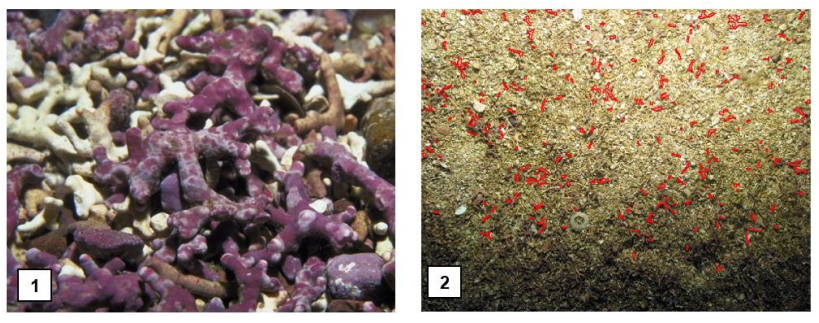

How pink is the seabed? Deep learning to assess the quality of maerl beds through automated image classification

Lisa Kamphausen

Percentage cover of live maerl material is one of the metrics we use to describe the ecological quality of a maerl bed. Comparing data from several decades of survey work has shown us that humans are not very good at assessing percentage cover of pink maerl twiglets on the seabed, especially at low percentages. There is huge variation.

Thousands of images have been collected at three case-study sites on the Scottish west coast, where we have conducted repeat surveys of maerl beds over several years before and after introduction of management measures.

To be able to analyse such volumes of data we are working on an automated assessment method, using deep learning. A computer algorithm, once trained well, should be much better than humans at identifying how much of a picture is pink, and more efficient and consistent in analysing thousands upon thousands of images. The size of fragments and as well as their shape will also be analysed, providing more important metrics in relation to the condition of the habitat.

If things go to plan, we will be able to identify changes in the percentage cover of live maerl at these sites at sub-decadal timescales.

Initial steps

The automated classification is being developed in a cooperation between GIG (Karen Frake) and Marine Ecosystems (Lisa Kamphausen).

In the initial stages “eCognition” software was used to segment images (divided into polygons) from a training dataset and generate an initial classification where dark objects and shadows were identified. Then, using a shallow Neural Network on Google colab, information was created which allowed objects to be classified into live and dead maerl fragments. Finally, the classification was joined back to geometries, and geometric characteristics of maerl fragments (such as size) were calculated using ArcGIS.

The classification was then improved by applying deep learning, using the MASK R-CNN model (to enable the outline of maerl fragments to be delineated, rather than just a bounding box).

Reality-check

So far so good - the concept was successful. However, trying to scale-up and introduce other, older datasets proved more complicated. Firstly, as technology has advanced, camera systems have changed, and our images have not all been taken using the same set-up. Often they were not evenly lit, and areas of shadow affected the quality of the classification. Sometimes the maerl was partly obscured by seaweed, and in other images pink shell fragments masqueraded as maerl. And then it became apparent that even pink comes in shades of grey; dying maerl progressively fades in colour, and there is no one clear cut-off that distinguishes live from dead.

Later we found that Google colab did not have enough RAM to process our images. Thankfully, NEODAAS (NERC Earth Observation Data Acquisition and Analysis Service) at Plymouth Marine Laboratory gave us 15 access to Mageo (Massive additional GPU for earth observation) which enabled the model to be trained and processing of an initial approximately 2500 images. Their assistance and provision of increased processing power is gratefully acknowledged. The model is undergoing improvements with the aim of a better classification across different survey areas and dates.

Going forward

We are now working with a Masters student, Ellie Takhar supervised by Mark James and Tania Mendo at St Andrew’s University, to take the next steps. Ellie is going to perform an accuracy analysis of the existing model, a manual clean-up of outputs and analysis of geometric characteristics. We need to understand how well the model performs in different conditions, what post-processing may be required, and whether the algorithm needs to be adjusted for new locations.

At the end of the project we hope to have a novel image analysis technique for the assessment of subdecadal changes in maerl beds in Scotland, to inform future advice to Scottish Ministers on the effectiveness of MPA management measures.

The Native Oyster

David Donnan

The Native Oyster ‘Ostrea edulis’ was once more widespread and abundant in Scotland than it is today. In some locations, famously in the Firth of Forth, there were extensive oyster beds of high economic significance. However, in common with other countries around the North Sea, the Native Oyster underwent a steep decline in the late 19th century and today are absent from the east coast. Native Oysters are now found only on the west coast and islands, where they have a patchy distribution with highly variable abundance.

This dramatic decline is reflected in the conservation status of the species, being listed as a Threatened and Declining under the OSPAR convention and as one of our Priority Marine Species. Native Oysters are also included in the Marine Protected Areas (MPA) network, being a feature of the Loch Sween MPA.

Due to its scattered distribution the status of the Scottish Native Oyster population remains far from complete. Building the evidence base is an ongoing task, with our existing records being drawn from literature, collected in the course of field surveys or via targeted projects such as reported in NatureScot Commissioned Report 251: Conservation of the Native Oyster (Ostrea edulis) in Scotland.

The importance of understanding and conserving this remnant Native Oyster resource has been underlined further by the recent growth in interest in restoration of the species. There are currently a number of projects happening or in development, including the Dornoch Firth and the Firth of Forth on the east coast, and ranging from Wester Ross to Argyll and to the Clyde on the west.

During work carried under the 2007-2012 Species Action Framework, the feasibility of oyster restoration was given consideration and it identified two significant challenges to be overcome. The first relates to the inherent risks of disease and non-native species in the movement of shellfish, while the second is the lack of availability of biosecure oysters in sufficient quantities for restoration efforts to be successful.

Consequently, the existing population has the potential to provide the broodstock that will enable these challenges to be overcome. But, only if the existing oyster beds are of sufficient size to readily sustain collection from them.

And that brings us to the ‘Oyster Ark’ project funded by round three of the Biodiversity Challenge Fund and led by Prof Bill Sanderson of Heriot Watt University. Part of the project has involved developing our knowledge of oyster abundance, by reviewing a wide range of formal and citizen science records and carrying out reconnaissance surveys at likely locations. A smaller number of sites were selected for more detailed quantitative survey to assess population size. The latest surveys took place at locations on the west coast in autumn 2021 and Lisa Kamphausen from our Marine Ecosystems team accompanied the Heriot Watt team.

Prof Sanderson says “We are currently assessing and writing up the results of the surveys, which had very promising results. We are now in the process of seeking the necessary consents from Marine Scotland for collection of oysters to be moved to a hatchery partner in Orkney. In addition, we are using novel molecular testing methods to ensure that any oysters moved are disease free”.

The Oyster Ark project marks an important step forward in the conservation of the Native Oyster, by bolstering our knowledge of the west coast population and helping to underpin the future success of restoration efforts.

British Ecological Society conference – December 2021

Jeanette Hall, Fairlie Kirkpatrick-Baird, David O’Brien and Karen Frake

One of the few conferences to be held in person in 2021, the British Ecological Society conference was an illuminating, and energising event held jointly with the French Society for Ecology and Evolution (SFE2). The event boasted an attendance of 708 participants in person and 679 remotely, with up to eight concurrent streams covering a variety of topics including Nature Based Solutions, genetics, ALAN (Artificial Light at Night), pollinators and agro-environment schemes - from 445 speakers. There were some incredibly well delivered and inspiring plenary talks. A wide variety of other presentations showcased some in depth thinking; they challenged mainstream attitudes, provided a passionate outlook on scientific practices and conservation objectives, displayed cutting edge technology, and focussed on scientific evidence for a wide range of ecological topics and context for our work. There were also social meet-up groups for many aspects of ecology providing opportunity for further engagement. The event was incredibly well organised and we all felt COVID safe due to measures put in place.

Four of us were privileged to go to the conference, three in-person and one virtually. In-person attendance provided a fantastic opportunity to interact with people face-to-face and experience the passion and energy from having so many like-minded people from across the world in one place.

NatureScot has a long association with BES Events, including the Scottish Policy Group and various Special Interest Groups. Staff have attended the conference in past years and presented on topics including drought risk and genetic diversity. This year followed that tradition with David O’Brien presenting on ‘Codevelopment of habitat enhancement in farmland and forestry is effective in safeguarding a range-edge amphibian population’. Codevelopment was a major theme this year with several speakers stressing its importance, and David co-chaired a workshop on the topic. The level of interest perhaps suggests that more people in research and conservation are recognising that solutions to the twin biodiversity and climate change crises have to be developed with communities rather than imposed upon them.

The talks on shifting baselines and their relevance to conservation were one of the highlights, giving an interesting range of perspectives. Presenters rolled back the clock to explain why farmers in West Sussex had a very different view of what traditional countryside should look like from that of their parents, possibly explaining why the latter were more enthusiastic about rewilding projects like that at Knepp. Going further back, presenters discussed the legacy on the microbiome and flora of semi-natural woods left by the Romans and the arrival of the House Sparrow in Britain around 3,000 years ago. As much as anything, it was a reminder that the past is dynamic, that our vision of what the countryside used to look like is very different from that of our grandparents, and that we need to be clear about what our baseline is when we talk about restoring nature.

Other highlights included:

- A method of training deep learning models using training data where each image only included a single type of class

- A project focussing on degradation of eDNA, taking place in Assynt

- Research on the association of spider species with different species of tree, including work taking place across Scotland

Overall, the conference was an energising experience and although the virtual option was good it was felt that a lot was missed due to limited talks being streamed and not being able to interact in person. However, it did mean that topics were encountered that would not normally have been. We must also recognise the incredible work of the organisers in managing to run a hybrid format conference and in working to keep delegates safe. The next conference is to be held in Edinburgh, where we look forward to showcasing our work and further engagement with a passionate forward-thinking scientific community involved with ecology.

References

O'Brien, Hall, Miro, O'Brien and Jehle (2021): A co-development approach to conservation leads to informed habitat design and rapid establishment of amphibian communities. Ecological Solutions and Evidence 2:e12038

End piece – some reflections from a SAC member in Norway!

Jane Reid

Scotland is surrounded by precious oceans: we all know that, but it is too easy to forget. Now, we must act positively to safeguard Scotland’s marine life and environments in the face of enormous challenges.

We do need to utilise the marine realm for fisheries, and for unprecedented scales of renewable energy developments that will underpin our essential transition to net-zero. Yet, we also need to balance these demands against protecting biodiversity. This tricky balance must be struck in the context of rapid climate and environmental changes that are disproportionately affecting our seas and key marine species. I have certainly seen this first-hand when extreme winter storms caused huge mortality in east coast populations of the red-listed European shag. If that were not enough, we must also deal with the legacy of past misdeeds; Scotland’s waters are still littered with wartime debris, and other forms of legacy pollution and habitat degradation.

Navigating through these complex and competing demands will certainly require a strong science base, providing sound information and predictions on which fair and effective policy decisions can be based. Yet, the ambition to understand the workings and requirements of marine life presents severe challenges to us scientists: marine biologists are terrestrial animals after all!

Now, it is heartening to see NatureScot’s advancing capabilities at the interface between marine science and policy. This newsletter serves to illustrate how new technologies, encompassing everything from drones to underwater cameras to high-performance computing, are being deployed to revolutionise our capabilities to monitor marine species and the environments on which they depend.

Yet, for the moment at least, technology is still nothing without the people. This newsletter also showcases how NatureScot has invested in talented and enthusiastic marine and coastal staff, who can work in collaboration with key stakeholders and the wider public to generate new knowledge and ensure its translation into practical advice and policy decisions.

These advances cannot come too soon. Summer 2022 will see the critical COP15 UN Biodiversity Summit. Perhaps we have not heard so much about COP15 as about the COP26 Climate Change Conference, but we really should have done. It will define the Global Biodiversity Framework, which will underpin global efforts to conserve and restore biodiversity over the coming decades. Particularly for the marine realm, we must raise our eyes to think not only nationally, but also internationally.

From my window here in Norway I can see the sea. It is the same turbulent and awe-inspiring sea that stretches across to Shetland, and down to my other home in Aberdeen. It is the same warming and the same kinds of energy and aquaculture developments, impacting the same biodiversity. NatureScot’s expertise will be invaluable as we take on the challenge of ensuring the best possible joint future.