Marine and coastal enhancement projects within Scottish inshore waters - Guidance on scoping a proposal

Published 2022

Introduction

Striving for enhancement

The aim to leave the environment in a better state than which we find it in has been a growing area of focus over recent years, responding to drivers such as habitat loss, threat to species, risks to the wider ecosystem and impacts from climate change. There has been a growing sense of ambition and environmental stewardship both from communities and partnerships, as well as Government and private sectors, with a recognition that environmental improvement may often provide a range of benefits.

This ambition has been supported through voluntary measures on a site by site basis but now benefits from an increasing framework with commitments for environmental enhancement (e.g. OSPAR restorative targets in the 2010-2020 strategy and new post-2020 Biodiversity Framework and the North-East Atlantic Strategy). Within Scottish legislation (Marine (Scotland) Act 2010) and policies (e.g. Scotland’s National Marine Plan) there is a commitment to the protection of marine habitats and species as well as for their sustainable enhancement and restoration. These are addressed through specific feature and site protection, i.e., Priority Marine Features (PMFs) and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). They provide a core foundation from which individual enhancement projects can then go on to help achieve more widespread goals and objectives for environmental health as a whole.

Types of enhancement

‘Enhancement’ has been used, for the purpose of this document, as an umbrella term for a range of different mechanisms through which a species or habitat may be improved at a site. It includes habitat or species recovery, regeneration, restoration, creation or, less often in the marine environment, rewilding. These terms are defined further in the Project Information section.

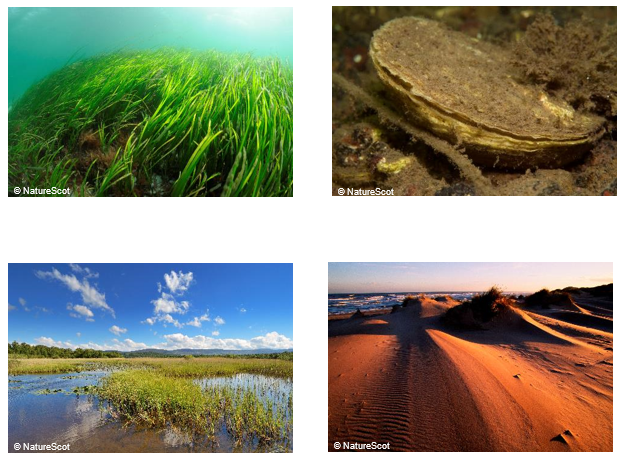

A seagrass bed

A close-up of a native oyster on the seabed

Saltmarsh showing the mosaic of vegetation and water

Sand dunes.

NatureScot’s role

NatureScot are Scotland’s nature agency and we work to improve our natural environment in Scotland and inspire everyone to care more about it. As the nature advisor for Scottish Government we are the key organisation in providing advice on marine and coastal enhancement projects in Scotland. NatureScot‘s advisors help those planning new enhancement projects, from early engagement, through to full proposal and subsequent project development and monitoring. We provide a wide range of skills and experience in specific species and habitats, local knowledge, enhancement projects and conservation and management.

Marine and coastal enhancement framework

This document provides guidance on NatureScot’s framework to support the development of suitable marine and coastal enhancement projects in Scotland. This is primarily aimed at four features which have been of the highest interest, including native oysters, seagrass, saltmarsh and coastal sand dunes, though it also provides a useful guide to other habitats or species (hereon named ‘features’).

The framework aims to guide those planning an enhancement project through the process, advising on the types of information required by NatureScot, other regulators and funding bodies, as well as what approaches are most likely to lead to success. Ultimately the framework provides a clear structure from which applicants may build their proposals and map out the necessary components to ensure an efficient process.

The provision and use of a consistent framework allows NatureScot to provide better advice, in a timely manner, ensure consistency between different projects, support site suitability assessments and in doing so improve the chances of success in enhancement projects. The framework also ensures we provide suitable guidance on project compliance and risks to ensure greater project efficiency and progression at the early stages.

It is recognised that an iterative approach is often best suited to developing enhancement projects. Therefore NatureScot welcomes initial informal discussion in the first instance, with this then informing initial steps and development of a proposal.

At this initial enquiry stage, the Marine Scotland Licencing Operations Team (MS-LOT) should also be contacted as, even if the activity is exempt, this will require confirmation by Marine Scotland or completion of their exemption form. Whilst an overview of licensing is provided in the Regulation and Management Section 4, initial guidance can be sought online.

Initial enquiries with NatureScot

NatureScot welcome initial enquiries by email and telephone. This should provide a very brief overview of the planned project to cover:

- Lead applicant details

- Enhancement feature and type

- Site location

- Primary project objective(s)

- Timescales

Such information will allow NatureScot to provide an initial high-level steer, point to available resources to inform proposal development, as well as providing early advice on the consenting process. Contact details are provided at the end of this document.

Enhancement proposal form

Following an initial enquiry, NatureScot will guide the point of contact through the marine and coastal enhancement proposal form, to be filled out by those developing projects. The proposal form consists of a set of questions about the project to aid a more detailed assessment by NatureScot and a wider set of stakeholders / regulators.

This guidance document acts as a guide to completing the proposal form, detailing the scope and types of information required at each step within the form to support completion and submission to NatureScot. The following sections in this guidance document refer to the corresponding sections in the proposal form to complete.

While native oyster, seagrass, sand dunes and saltmarsh are the focus of the guidance, the process is not limited to those features.

Ongoing support

Once full details of the project are shared NatureScot will be able to provide ongoing support through the project. This may include further advice on guidance and regulation, stakeholders to engage with and advice on monitoring, management and success of the project over time.

Further information

As part of this framework, a more detailed report is also available to provide a wider context and experience in enhancement projects; and specific information on four features (native oyster, seagrass, sand dunes and saltmarsh), such as legislation, policy and regulation, lessons learned and guidance. The full set of resources for the marine and coastal enhancement framework is provided below.

- Guidance (this document): NatureScot (2022) Marine and coastal enhancement projects within Scottish inshore waters: Guidance on scoping a proposal

- Proposal form: NatureScot (2022) Marine and coastal enhancement projects within Scottish inshore waters: Proposal scoping form

- Project report: Full project report with additional guidance and case studies. Chambers, C., Jones, K.L., Malcolm, F., Boyle, G., Sanderson, W.G., Garbutt, A., Jones, L., Unsworth, R.K.F. and Lilley, R.J (2022). Development of a marine and coastal enhancement project assessment framework for Scottish inshore waters. NatureScot Research Report No. 1293

Throughout this document, further information specific to each section of the proposal form is also provided, as well as broader and feature specific information at the end of the document.

1. Project Information

Overview

The most important information required in developing a proposal are the ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘how’, ‘why’ and ‘when’ of the project, detailing the basics of the project design / plan. These will provide the basis from which to assess all subsequent aspects of the project’s development. Project details are also the essential components for any initial email or telephone enquiry, albeit in a more brief format (see Initial enquiries).

Feature

The proposal should state which feature(s) (i.e. habitat or species) the scheme focuses on, whether this is native oysters, seagrass, saltmarsh or sand dunes (or other); and any specific sub-species’ common and Latin names, where known.

Location

In addition to the site name, area and region of Scotland that the project is located, it would also be useful to include a geographic reference through coordinates (e.g. centroid or bounding box) with the coordinate system specified. For example, this could be ‘Newburgh, River Tay, near Perth, Central Scotland, 56.3563N, 3.228W, WGS 84’ (or equivalent Ordnance Survey grid reference). Other means to providing the geographic reference could be through attaching a spatial layer file. These may be generated through the use of freeware such as GoogleEarth (.kml file), QGIS (shapefile .shp file) as well as commercial products including ArcGIS.

Enhancement type

Whilst ‘enhancement’ is used as an overall term for the purpose of this framework, there are a number of different types of enhancement a project may be characterised by. Consideration of these different types, as defined in Table 1, can help to consolidate a project’s aims.

|

Enhancement type |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Habitat Enhancement |

This term is applied in relation to those actions that aim to improve the quality, size or geographic distribution of a habitat. |

|

Habitat Recovery |

To be used in relation to actions taken to enable a habitat to overcome damage or other disturbance and reach a better state, rather than trying to “turn the clock back”. This is seen as a relatively passive process involving removing pressures and allowing the habitat to repair naturally. |

|

Habitat Regeneration |

Still conveys a process but with possibly low level interventions taking place alongside removing pressures. The term regeneration can also be used where there is active fishing (see Part 1(ii) for more explanation). |

|

Habitat Restoration |

NatureScot consider the term “restoration” to be applicable to projects entailing a high level of intervention, such as those rebuilding a habitat or reintroducing an ecosystem engineering species to assist with enhancing a habitat into a location from which it has been extirpated and where re-establishment could not occur without assistance. |

|

Habitat Creation |

Habitat creation can be used in two different contexts – one using more natural approaches and substrata, for example, creating saltmarsh as part of managed realignment work; and one using artificial substrata or creating habitat where it was not historically present, for example, in offshore marine developments. |

|

Rewilding |

Restoring processes and functions in very large, landscape / ecosystem scale projects (though marine habitat enhancement is at too small a scale currently for this term to be applied, scientifically and scale wise. |

Process

Off-site preparation for project

Proposals will need to describe the physical steps involved prior to on-site work. One important consideration here is any physical movement of supporting material, e.g. cultch, soil or biological material. Details should be included on the nature of donor material, e.g. seeds or other plant propagules, soil, eggs, larvae, juveniles or adults; as well as donor site location, hatchery or seed storage tank. It is also useful to specify any sub-species, variety, ecotype or race. A detailed set of guidance specifically about translocation and the security risks and legislation is provided in the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations (see ‘Risks’ section).

Site methodology

The site methodology should provide any physical steps planned on site and access required to site to implement the enhancement project. This may include equipment, technology, people etc.

Timescales

If possible, the applicant should aim to specify the project timescales, including the proposed start date for site preparations at a minimum. It is important that these are realistic from the outset. Any further key milestones are also useful where planned, e.g. the various stages of the project and when the final outcomes are expected to be achieved.

2. Project Rationale

Primary enhancement objective

This aims to capture the desired overall outcome of the project. This will need measurable target(s) and will normally be governed by the extent of the habitat or species established in a given area. For example, this could be the target area (m2) or proportional increase in area, as well as the optimum location within a site.

The primary objective may be further defined through a target number or density of individuals, level of biodiversity of the feature, or a target vegetation or marine community.

These all require measurement against, and therefore knowledge of, the baseline conditions from which to determine success in the project. It can be useful here to consider confidence in achieving these measured outcomes. This will need some consideration of the risks involved, which is detailed in the Risks section.

Any other benefits that will be achieved indirectly as a form of ecosystem services, should be outlined in the Benefits section. These may take the form of ‘supporting’, ‘regulating’, ‘provisioning’ or ‘cultural’, with examples such as improvement of water quality from native oyster filter feeding, meeting site conservation objectives, or wider national or international restoration targets.

- Area-based solutions with wider habitat management, e.g. as an alternative way to improve water quality

- Species-based solutions with targeted management, e.g. controlling invasive non-native species, diseases and pathogens

- Social / indirect solutions, e.g. protection of ecosystem via a designation or public education / outreach programmes

- No action, e.g. no human intervention

3. Site Profile

Overview

Essential to the success of any project will be the collection of biological and environmental site characteristics and assessing their suitability for the enhancement planned. This section considers aspects applicable to all features, whilst specialist guidance for each feature, i.e. native oysters, seagrass, salt marsh and coastal sand dunes, may be accessed from the links in the ‘Further information’ section at the end of this document.

Site Suitability

Natural characteristics

In order to assess the suitability of a site for the planned enhancement, the wider environment and ecosystem dynamics will need to be assessed. These include key issues such as the conditions leading to a need for enhancement in the first place, and whether this is the most appropriate location to achieve the enhancement. These may be explored through a few key questions:

- If the enhancement focuses on a new location, what are the key environmental and other conditions that will ensure success, and how well does this site meet those conditions? These may consider substrate, depth, light quality, turbidity, exposure, intertidal exposure, water quality, seasonal change etc., as well as any model outputs on habitat suitability and connectivity.

- What is the current and historical temporal / spatial change of the feature at the site, in terms of extent and distribution, condition, as well as resident population sub-species, variety etc.? Assessment may be informed by data in the National Marine Plan interactive portal and NatureScot’s Sitelink for protected areas.

- What other species occupy the area, considering food chains, predators, herbivores, pollinators and dispersers, pathogens and parasites?

- Is the site large enough to enhance the wider ecosystem or other objectives and is the feature sufficiently connected to or dependent on other sites?

- It is useful to outline how these characteristics have been informed or estimated (also see ‘Evidence Base’ below).

Answers to the above questions will set the scene for site suitability alongside a background understanding of the feature’s basic biology as well as life stage requirements, reproduction, population dynamics, seasonal biological change and species interactions, etc.

Activities and pressures

The site suitability assessment should also be informed by the current activities and pressures in the area and it would be useful to note patterns of use, known impacts and any management of activities. Pressures might include, for example, known fishing pressures, dredging and recreational shipping activities, atmospheric nitrogen deposition to sand dunes and saltmarsh. Meanwhile management activities might include presence/absence of grazers on saltmarsh and sand dunes, drainage or other influences on water levels and water quality in coastal wetlands. It is important to consider:

- If the need for enhancement is due to external or internal pressures on a site, what are those pressures, are they still present and if so increasing or decreasing, and how will they influence the success of the planned enhancement?

Evidence base

Existing data

The evidence base is a critical component to any enhancement project to gain support and help ensure project success. In the first instance, this is likely to include collating information on historic in-situ surveys and outputs such as habitat models. It may also include other forms of data capture, such as historic maps, aerial photographs or satellite imagery. It would be useful to note here any ongoing survey programmes outside of the scheme itself that may be used to assess outcomes over the project lifecycle.

Key gaps

This section is primarily aimed at identifying the key gaps in information on the feature and environment but may also address other activities in the area as well as gaps to understanding a fuller view on the project risks and benefits. Key gaps should be addressed in the ‘Management, monitoring & evaluation’ section and any residual gaps should inform the uncertainty in outcomes.

Baseline monitoring

Most projects will require baseline surveys before undertaking the pilot study / trials and before scaling these up, depending on the level of existing information. As noted in the ‘Project Rationale’ section, baseline surveys provide critical information of the condition before enhancement takes place and inform the degree of success of the subsequent enhancement scheme. However a baseline survey is important to ensure the site is suitable for the target species / habitat, to help with assessing potential impacts on protected features and if it is appropriate to carry out the project in that location.

Baseline surveys should assess current feature characteristics, status and the environmental conditions at a site to find out if it is suitable for enhancement (answering some of the questions outlined above). Different features will require specific environmental conditions and assessments need to take account of both the biological and the wider ecological status of the site, e.g. monitoring light levels for seagrass, water levels for dune slack wetlands, water quality for shellfish and seagrass. This is also covered further in ‘Management, monitoring & evaluation’.

4. Regulation and management

All projects will need to carry out early engagement with regulators, and NatureScot are available for initial discussions. This will help map out the necessary license and permits required and allow timely progression of the project. Licenses and permits may be required in four categories: species, protected areas, activities and access.

Early engagement is particularly important where a project crosses the terrestrial and marine environment in the intertidal area (between Mean Low Water Springs and Mean High Water Springs) to allow liaison between authorities, management of timing and sharing the evidence base.

Information on licenses and permits is presented in the following four sub-sections and associated tables. Whilst an overview the possible licenses and permits is given, these will be assessed on a site by site basis and may not necessarily be required: these should be checked with the regulator.

Further information is also available in the full report (Chambers et al., 2022). It should be noted that marine and terrestrial licensing is continually under review, with this being particularly the case for marine and coastal enhancement practices. Therefore, the latest information should always be checked with the relevant regulators.

Should any further information be required in addition to that provided on the weblinks below, please contact the relevant regulator or organisation as follows:

See website for contact form

See website for relevant local authority

Focal Species / Habitat

Native oysters, seagrass, saltmarsh and coastal sand dunes are listed as conservation features of interest both at the international level and protected through Scottish legislation (Table 2). Further information for species regarding biosecurity is provided in the ‘Risks’ section.

Licenses related to species include:

- Species license related to the activity

- Species that may undergo hybridisation

- Translocation of species

- Involving non-native, invasive or dangerous species (if using translocation)

- Pests or disease possible

|

Name |

Native oysters |

Seagrass |

Saltmarshes |

Sand dunes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

Yes |

– |

– |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Yes (Translocation to former historical oyster beds) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes

|

|

|

Biosecurity Plan (Marine or Terrestrial) |

Yes (both organisms and cultch) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Protected areas

A principal consideration in project proposals is whether the site falls within or in the vicinity of a protected area, e.g. Nature Conservation Marine Protected Area (MPA), Special Protection Areas (SPA), Special Area of Conservation (SAC), Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) or a Ramsar site; or in an area that is governed by other legislation such as a local Byelaw. Often this will result in a need for a formal assessment to consider whether the enhancement project will impact on the conservation objectives of the site. This could be positive for the environment with potential enhancement of the protected area and future protection extended to the species / habitat; or negative, with a resultant loss or change in protected species / habitat extent or species composition.

The extent of the potential interaction will dictate the level of engagement required with regulators, e.g. the need for a license / consent / assessment, how to go about this and how work could be undertaken to avoid any negative effects.

If the project is capable of affecting the protected features of an SAC or SPA, a Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) is required under the Conservation (Natural Habitats & c.) Regulations 1994 (as amended). If it is within a MPA then an assessment is required under Section 82, 83 or 95 of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010. A SSSI consent may be required if an SSSI could be affected. Table 3 below provides a summary of the protected area legislation and assessments.

|

Name |

Native oysters |

Seagrass |

Saltmarshes |

Sand dunes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Section 82, 83 or 95 assessment |

Section 82, 83 or 95 assessment |

- |

- |

|

|

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

|

|

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

|

|

Operations Requiring Consent (ORC) |

Operations Requiring Consent (ORC) |

Operations Requiring Consent (ORC) |

Operations Requiring Consent (ORC) |

|

|

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

Habitats Regulations Appraisal |

|

|

Area specific Byelaws (Go to relevant local council website) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

[a] Note Ramsar sites in Scotland overlap with either SPAs or SACs and all are underpinned by SSSIs; are therefore protected under the relevant statutory regimes.

Activities

Across all areas of Scotland, certain activities will require a licence as summarised in Table 4 below. These will all need considering on a case by case basis as certain setups will exclude the need for a license, e.g. suspending oyster cages from existing infrastructure. Those licences listed under native oysters and seagrass would also be applicable to other marine species and habitats.

|

Name |

Native oysters |

Seagrass |

Salt marshes |

Sand dunes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Depositing, constructing, or using a vessel to remove an object from the marine inshore region (0 and 12 nm) |

Depositing, constructing, or using a vessel to remove an object from the marine inshore region (0 and 12 nm) |

Depositing, constructing, or using a vessel to remove an object from the marine inshore region (0 and 12 nm) |

Beach replenishment |

|

|

– |

– |

Local authority conducting coastal protection works |

Local authority conducting coastal protection works |

|

|

Crown Estate Scotland Marine Works / Lease / Seabed survey license |

Activities that physically interact with the seabed and filming on the foreshore |

Activities that physically interact with the seabed and filming on the foreshore |

Activities that physically interact with the seabed, filming on the foreshore, coastal protection and flood defence works |

Coastal protection and flood defence works |

|

Movement of oysters to temporary abode as trial phase or part of biosecurity operations |

– |

– |

– |

|

|

Local Authority Planning Permission (Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997) |

– |

Above MLWS but depends on nature and scale |

Above MLWS but depends on nature and scale |

Above MLWS but depends on nature and scale |

|

Water Environment Regulations 2011 (Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009) |

– |

– |

Activities that might impact on wetlands such as enhancement works |

– |

|

Water Use Licence (Water Environment and Water Services (Scotland) Act 2003) |

– |

– |

Activities posing the greatest risk to the water environment e.g. engineering works in and near freshwater |

Activities posing the greatest risk to the water environment e.g. engineering works in and near freshwater |

|

Water Use Licence (Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011) or ‘CAR’ |

– |

– |

Construction, alteration or operation of impounding works in surface water or wetlands |

Carrying out building or engineering works likely to cause a direct or indirect impact |

|

Felling License (Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Act 2018) |

– |

– |

- |

Woodland removal |

Landowner and access

In addition, permission to carry out activities will be required from the land / seabed owner which may include Crown Estate Scotland (CES), local council’s planning permission and private landowners. This will concern:

- Project site

- Access to site

- Donor site (if translocation)

A summary of permits, byelaws and licenses, both marine and terrestrial, is provided below in Table 5 for each feature. Those already presented in tables above are presented in lighter grey text.

|

Name |

Native oysters |

Seagrass |

Saltmarshes |

Sand dunes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Crown Estate Scotland (CES) Marine Works / Lease / Seabed survey license |

Activities that physically interact with the seabed and filming on the foreshore (already presented) |

Activities that physically interact with the seabed and filming on the foreshore (already presented) |

Activities that physically interact with the seabed, filming on the foreshore, coastal protection and flood defence works (already presented) |

Filming on the foreshore, coastal protection and flood defence works (already presented) |

|

Planning permission (Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997) |

– |

Above MLWS but depends on nature and scale (already presented) |

Above MLWS but depends on nature and scale (already presented) |

Above MLWS but depends on nature and scale (already presented) |

|

– |

– |

Re-routing footpaths |

Re-routing footpaths |

|

|

– |

Applies if not owned by CES or council |

Applies if not owned by CES or council |

Applies if not owned by CES or council |

5. Risks

Risks associated with the project include risks to the feature itself, impacts to the wider ecosystem and environment, the local community and businesses, as well as risks to the project itself, such as dependency on funding. All of these may affect the short-term or long-term success of the enhancement project. The proposal form provides an opportunity to lay out the initial risks and potential mitigation measures considered. Risks will need to be considered in relation to potential / presumed current and future threats in relation to climate change.

Biology and Ecology

Information on biological and ecological risks are provided in the following subsections below.

Biosecurity

One of the key biological risks with enhancement projects is biosecurity, i.e. the introduction and/or spread of harmful organisms. This will need examining in relation to both wild populations and to the fishing and aquaculture industry.

Whilst not required at the proposal stage, projects will ultimately need to demonstrate they have appropriate and rigorous biosecurity protocols in place before carrying out any work. We would expect that projects going ahead would develop a Biosecurity Measures Plan, which will require scaling up over time as the project develops. Overall, a precautionary approach is needed and it is recommended biosecurity measures are introduced even where no invasive non-native species or disease are thought to be present.

NatureScot also recommend the Check Clean Disinfect Dry procedure and can advise on a case by case basis, e.g. ways to reduce biosecurity risk may include local movement of species from adjacent sites.

Translocation

Biosecurity risk is particularly evident during translocation of both organisms and cultch. Due to the high degree of risk with translocation, the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations must be followed where this is relevant. The code provides detailed guidance and checklists on the range of risks and mitigation (see Further Information). In the first instance, risk may be reduced by ensuring the historical range of a species is maintained, avoiding high risk donor sites, e.g. with disease present, and using a nearby donor site within the same water body.

Further information on biological risk

- Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations (Guidance): National Species Reintroduction Forum (NSRF). 2014. The Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations.

- Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations (form): National Species Reintroduction Forum (NSRF). 2014. Best Practice Guidelines for Conservation Translocations in Scotland Version 1.1. Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Marine biosecurity planning best practice: Cook, E.J., Payne, R.D. & Macleod, A. 2014. Marine biosecurity planning – Identification of best practice: A review. SNH Commissioned Report No. 748.

- Check Clean Dry Procedure: Scottish Invasive Species Initiative website: Biosecurity

- European Guidelines on Biosecurity in Native Oyster Restoration: zu Ermgassen, P.S.E., Gamble, C., Debney, A., Colsoul, B., Fabra, M., Sanderson, W.g. Strand, Å. & Preston, J. (eds), 2020a. European Guidelines on Biosecurity in Native Oyster Restoration. The Zoological Society of London, UK., London, UK.

- Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations: IUCN, 2013. Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations. Version 1.0. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Species Survival Commission.

- Non-native Species - Code of Practice: Scottish Government (2012) Non-native species: code of practice. ISBN: 9781780459301.

Genetics

It is important that restoration practices maintain local or regional genetic diversity and adaptations of plants and animals. In all organisms, seeking techniques that maximise the genetic diversity in the offspring can enhance resilience to future change, e.g. high genetic diversity and Bonamiosis-resistance are important features of any sustainable restoration programme for shellfish, helping ensure ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions, disease and climate change.

Wider ecosystem

Risks to the wider ecosystem include potential reduction or removal of established habitats and / or a shift in the ecosystem. This may be direct e.g. where a newly created habitat replaces what was there previously, or may be indirect, e.g. due to competition for resources between native oysters and blue mussels.

Climate change

The applicant will need to consider climate change resilience and potential adaption of the site in relation to current and future climate states. Considerations should range from sea-level rise, and increased terrestrial flooding, changes in air temperature and rainfall patterns, which in turn affect groundwater levels in wetlands, to sea temperature range changes, increased storminess and extreme weather events. However, these will depend on the local area’s vulnerabilities and will also be informed through recent climate change impacts at the site. For example, a site that historically contained a seagrass may no longer provide the ideal environment given increased storminess and sea level rise; or may become ideal conditions for an invasive species, e.g. Pacific Oysters. Further information on risks associated with climate change is provided in the section on general guidance.

Socio-economic

Potential or perceived risks to the local community’s livelihoods, leisure, health and wellbeing may result from a variety of impacts, including restricted access / interaction, change of land use, loss of other species and habitats or changes to the wider ecosystem, e.g. water quality, erosion control, pollination or nutrient cycling. Risk mitigation in such circumstances will require careful management of concerns, resistance, conflicts and incident management.

Management

Funding may pose a risk to the project in terms of reduced funds causing inadequate management and reduced attraction of future funding, or negative impacts resulting in remedial costs. Funding sources can also govern the design of a project to a certain extent. Consideration should be given to ensure that projects are adequately designed to not only secure funding but also ensure processes are in place to allow the correct and efficient progression, e.g. through aspects such as licensing.

Risk mitigation

As the project design develops, a risk mitigation strategy will be required, outlining actions that will be taken to reduce the risk of negative impacts occurring. This will require a monitoring plan to identify risks and remedial action if required. Such mitigation planning would also be useful at an early stage help address requirements in the licensing, consenting processes.

Further information on climate change

- Climate change and marine conservation: United Kingdom Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership (MCCIP). 2018. Climate change and marine conservation: Saltmarsh (Eds. Ladd C, Skov M, Lewis H and Leegwater E) MCCIP, Lowestoft, 8pp. Climate change and marine conservation: Seagrass (Eds. Dawson K, Kennedy H, Leegwater E and Brazier P) MCCIP, Lowestoft, 8pp.

- Looking ahead: planning for coastal change (Scotland): SNH (2019) Looking ahead: planning for coastal change, Using coastal change information to plan for development and infrastructure around the coast, Guidance. In partnership with the Scottish Government’s Dynamic Coast project.

- Coastal systems and low-lying areas (climate change): Wong, P.P., Losada, I.J., Gattuso, J.-P., Hinkel, J., Khattabi, A., McInnes, K.L., Saito, Y. & Sallenger, A. 2014. Coastal systems and low-lying areas. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., Girma, B., Kissel, E.S., Levy, A.N., MacCracken, S., Mastrandrea, P.R. & White, L.L. (eds.)). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA, pp. 361-409.

6. Benefits

The proposal form allows for an initial assessment of the potential benefits. This may include information and examples of biological benefits, ecosystem services, socio-economic benefits, cumulative benefits and nature-based solutions.

Biology

As per the primary enhancement objective, a local species / habitat benefit can include increasing the number of individuals, improving population structure and/or increasing the number or size of locations at which a species occurs. This may include establishing populations in areas where the species will experience reduced levels of threat (e.g. by moving organisms into more suitable ‘climate space’, disease-free areas, or localities with suitable management). It can also include improving the genetic health and resilience of a population by directly introducing genetic diversity and establishing ‘bridging populations’ to facilitate migration and / or gene flow.

A wider benefit beyond meeting the core project objectives may also include reducing a wider geographic risk to extinction as well as improving the conservation status of a threatened or endangered species.

Ecosystem

Ecosystem benefits may include increasing the overall species richness of a habitat to enhance its biodiversity value, increasing habitat quality, e.g. translocating species to alter cattle grazing regimes, improving the conservation status of an ecosystem, habitat and/or other species, as well as improving ecosystem services and functions (e.g. water quality, blue carbon storage or habitat provisioning for economically important species).

Socio-economics

Socio-economic benefits may be provided to the benefit of local people and businesses in the region as a result of the proposed scheme. This may include local community environmental awareness through support and participation of the proposed scheme. This might include enriched human experiences and environmental awareness due to increased contact with biodiversity, wildlife tourism activities, as well as ecosystem services or commodities such as improved water quality. Increased visitors to enhancement projects could generate increase revenue for local businesses.

The project may also benefit by providing compensation for damage or loss caused by a particular activity, e.g. carbon credits, green credentials. The provision of benefits to the local economy may also be provided via employment, business opportunities and / or increases in tourism and recreational activities.

The proposal may also lead to cumulative benefits such as improved extent over a particular area or ecological connectivity, potentially in conjunction with other similar or related projects.

7. Engagement

Establishing and maintaining engagement with regulators, stakeholders and the wider community throughout the project life cycle will be a significant contributing factor to success of any enhancement project.

Early engagement

Whilst engagement will develop through the project’s lifecycle, early engagement is essential to establish project plans, site suitability, uncertainty concerning potential risks and impacts or legislative constraints. This will be especially important with the key regulators: Marine Scotland, Crown Estate Scotland (CES), NatureScot, Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) and the relevant Local Authority, as well as the public, Non- Governmental Organisations and other interest groups. It is essential that any engagement with regulators takes place prior to placing anything (animals or substratum, etc.) in or removing from the marine or coastal environment.

Whilst it is not necessary to detail any further engagement planned for the scheme within the proposal form, other aspects are detailed below to inform project development.

Stakeholder group

Most projects will benefit from setting up a stakeholder group with a range of members from constituent politicians (Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) and / or Member of Parliament (MP)), councillors, local authorities, Government bodies, environmental groups, community groups and councils, universities, developers and private sector businesses, residents and landowners. This will help to gain site knowledge, mitigate risks and ensure involvement from those that have been involved previously at the site.

Public outreach

Providing opportunities for public involvement often leads to a sense of local ownership providing not only pride and opportunity to the local community, but also a greater commitment to safeguarding the site. Involvement may include contributing to the evidence base as volunteers, as well as other forms of collaboration and shaping of plans, or through individuals enjoying benefits from the project such as tourism activities and educational programmes.

Communicating success

Stakeholder feedback is an essential component to demonstrate the direct impact of their involvement and progress in the site management, thereby encouraging ongoing commitment. This will be a critical element of the monitoring programme (below) and may include e.g. press releases, social media, conference presentations, displays and media.

8. Management, monitoring & evaluation

Funding

Funding sources may include European funding bodies, Government, grants, trusts, charities, Lottery, business, crowdfunding, community funding etc. The total value should account for the essential activities over the full life cycle of the project. This should be up until the project is complete or the site is considered self-sustaining, as well as accounting for any remedial funding for potential damage and long term monitoring.

Implementation

Details are required in this section of the proposal form on how the success and performance will be measured through the project, which often will include a staged process of monitoring. Metrics for measuring a change in the target feature may depend on certain tools and the comparison to prior conditions.

Metrics need to be specific, relate to the success criteria, and give a time scale. For example:

- Area of recognisable salt marsh vegetation in a realignment site (measure / report annually)

- Average density of oysters in restored area (measure annually)

Ultimately the success criteria will be provided through a clear plan that will deliver the proposal objectives, whilst considering the evidence that will measure if the objectives have been met. It can be useful here to consider confidence in achieving these outcomes.

Therefore any successful enhancement project will require a full management and monitoring plan that takes into account the legal requirements, feature management, risks, pressures and public engagement. Some of the key aspects for successful implementation include:

- Management plan with specific achievable tasks assigned to individuals or organisations within given timescales

- Progress review at all stages of the project to monitor success against objectives and adjusting where required, e.g. ecological impacts

- Arrangements for remedial action regarding indirect impacts or for reversing the enhancement itself if required

- Up-to-date documentation and accessibility of records regarding engineering, construction and cost information

- Monitoring plan for all stages of project including methods, logistics, contractors, costs etc.

Progress review

Staged progress reviews provide a cyclical process, with assessment against the specific objectives and the project’s milestones. It should identify management adjustments where appropriate e.g. ecological impacts and determination of effects, changes in relation to a shift in the ecosystem.

Adaptive management

Adaptive management allows for plans to respond quickly to changing information as it becomes available. It allows for action despite uncertainty in existing conditions and trends, both current, e.g. ecological features, or future, e.g. climate change and change in activities within an area. This uncertainty may be reduced in interactive steps through monitoring, improved understanding and guidance.

Using this knowledge to update plans allows for reduced risk and appropriate measures to be put in place. In some cases this may result in reduced control of activities; plan updates can therefore be of greater benefit to all users. As such, it is key that plan updates are demonstrated to the wider community.

Pressures management

One of the key aspects requiring management through the project will be assessing what activities are taking place on the site that may have an impact on the project’s success and managing these where possible (remove, displace or reduce).

Data collection & monitoring

Details of site monitoring are required to evidence that the applicant has considered how the site will be monitored to determine success, This information can include a proposed monitoring plan, identification of elements of the site and/or target feature that will be monitored, e.g.

- Feature measurements of density, extent and percentage cover, considering key stages of feature development

- Measurement of wider ecosystem effects such as sediment stability, water quality and fish / shellfish biomass, especially where these are a primary objective of the project

- Identifying receptors at risk from project, especially around biosecurity and other biological / ecological aspects

Consideration of location and timing of monitoring will be another important aspect, including:

- Concurrent baseline or reference area monitoring, i.e. natural unaffected areas, as close to site as possible but not less than 100m away; else historic baseline data (essential if no pre-restoration monitoring)

- Pre-restoration monitoring at the proposed site in the year prior to restoration to aid in site-selection and to document pre-restoration conditions, particularly if the site is an MPA (though this may be addressed through licensing requirements anyway)

- Post-restoration monitoring to assess whether changes are due to actions implemented as part of the enhancement project itself, or are due to natural change, e.g. inter-annual variations or changes in water quality

- Determine if the monitoring of the site will be maintained long-term to assess continued success

Further information on monitoring

- Guidance for Habitat Restoration Monitoring: Presents a framework for developing and implementing technically defensible monitoring plans for habitat restoration projects associated with the USA Department of Navy. Naval Facilities Engineering Command (NAVFAC) & Argonne National Laboratory, 2004. Guidance For Habitat Restoration Monitoring: Framework For Monitoring Plan Development And Implementation - User's Guide. Naval Facilities Engineering Command Risk Assessment Working Group.

Establishing Success

Success criteria

The success criteria will help determine how the scheme will measure performance and set targets. These must clearly express actions to deliver the goals and objectives of the scheme, taking into consideration evidence that will measure progress towards meeting defined objectives and ultimately determine the success or failure of the scheme. These should consider confidence in achieving the objectives to provide a best and worst case scenario.

Communication Plan

A communication plan will aid in the dissemination of information from the scheme to interested parties, e.g. land / site owner(s), public / local community and stakeholders. This can be achieved via various methods, including but not limited to press releases, social media, presentations, conferences, guided tours of facilities, displays and media (photography and video footage). The plan can document and share findings to support future strategies and projects.

Exit strategy

The decision to discontinue a project is considered defensible if the scheme design includes indicators of lack of success and the tolerable limits of their duration or if undesired and unacceptable consequences have occurred. This is particularly relevant to translocation schemes.

"In a changing world, the enhancement of our marine and coastal environment will help us build a more resilient, stable and sustainable world that benefits the natural world and the health and wellbeing of people today and for future generations."

Further information

For more information on general and feature specific guidance, see details below including weblinks where available.

General guidance

- National Review Innovative and Successful Coastal Habitats: Provides information on restoration research and the innovative and successful components of funding, partnerships, planning, restoration methodology, monitoring and adaptive management, dissemination of information and community involvement. Borde, A.B., O'Rourke, L.K., Thom, R.M., Williams, G.W. & Diefenderfer, H.L., 2004. National Review of Innovative and Successful Coastal Habitats. Technical Report, Battelle Memorial Institute, Duxbury, MA, USA.

- Nature Networks Evidence Handbook: Identifies the principles of network design and describes the evidence that underpins the desirable features of nature networks. Crick, H.Q.P., Crosher, I.E., Mainstone, C.P., Taylor S.D., Wharton, A., Langford, P., Larwood, J., Lusardi, J., Appleton, D., Brotherton, P.N.M., Duffield, S.J. & Macgregor N.A. 2020. Nature Networks Evidence Handbook. Natural England Research Report NERR081. Natural England, York.

- Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Provides a comprehensive assessment of the physical science basis of climate change. IPCC, 2013. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V. and Midgley, P.M. (eds.)). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM): Guides assessment teams through the ROAM and how they can be combined and sequenced to suit different needs. IUCN & WRI, 2014. A guide to the Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM): Assessing forest landscape restoration opportunities at the national or sub-national level. Working Paper (Road-test edition). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Marine habitat, enhancement, recovery, restoration and creation: Clarifies how NatureScot applies the various definitions for actions associated with marine habitat enhancement; and sets the scene for future research and casework. NatureScot. 2021. Information Note - Marine habitat, enhancement, recovery, restoration and creation.

- Land Reform: Provides information on land access rights. Scottish Government. 2003. Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. Acts of the Scottish Parliament.

Native oyster guidance

NatureScot and Marine Scotland are developing Scotland specific native oyster guidance, which will aim to provide advice to would-be applicants and ongoing schemes already in development, including both specific on-site guidance as well as wider geographic considerations such as the collection of broodstock for hatcheries. The current key guidance documents of relevance to enhancement in Scotland are listed below, whilst Chambers et al. (2022) provides a full review of further guidance.

- Oyster habitat restoration monitoring and assessment handbook (USA): Recommendations for a set of Universal Metrics that should be monitored for restoration projects and guidelines for assessing optional Restoration Goal-based Metrics. Baggett, L.P., Powers, S.P., Brumbaugh, R., Coen, L.D., DeAngelis, B., Greene, J., Hancock, B. and Morlock, S., 2014. Oyster habitat restoration monitoring and assessment handbook. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA, USA.

- Restoration Guidelines for Shellfish Reefs (USA): Provides guidance in decision-making for restoration projects and examples of different approaches undertaken by experienced practitioners. Fitzsimons, J., Branigan, S., Brumbaugh, R.D., McDonald, T. & zu Ermgassen, P.S.E. (eds) 2019. Restoration Guidelines for Shellfish Reefs. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington VA, USA.

- European Native Oyster Habitat Restoration Handbook: Provided information on restoration including current methods, biosecurity recommendations, and how to effectively communicate outcomes. Preston J., Gamble, C., Debney, A., Helmer, L., Hancock, B. & zu Ermgassen, P.S.E. (eds) 2020. European Native Oyster Habitat Restoration Handbook. The Zoological Society of London, London, UK.

- European Guidelines on Biosecurity in Native Oyster Restoration: Presents biosecurity guidelines for conservation and restoration of native oyster habitat in Europe, based on current knowledge and experiences. zu Ermgassen, P.S.E., Gamble, C., Debney, A., Colsoul, B., Fabra, M., Sanderson, W.G. Strand, Å. & Preston, J. (eds), 2020a. European Guidelines on Biosecurity in Native Oyster Restoration. The Zoological Society of London, London, UK.

Seagrass guidance

NatureScot have developed a Scotland seagrass restoration handbook and guidance document in collaboration with Marine Scotland and Project Seagrass. To ensure projects are evidence-led this document provides background information, regulatory considerations and monitoring / research guidance. The project report (Chambers et al., 2022) associated with this guidance document provides a substantial amount of further guidance on seagrass enhancement and experience from case studies. The current key guidance documents of relevance to enhancement in Scotland are listed below.

- Seagrass Restoration in Scotland: Provides an evidence-led approach to guide seagrass restoration proposals in Scotland. NatureScot. 2021. Seagrass Restoration in Scotland - Handbook and Guidance.

- Seagrass Restoration in UK and Ireland: Practical guidance on restoring and creating seagrass habitat. Gamble C., Debney, A., Glover, A., Bertelli, C., Green, B., Hendy, I., Lilley, R., Nuuttila, H., Potouroglou, M., Ragazzola, F., Unsworth, R. and Preston, J, (eds) 2021. Seagrass Restoration Handbook. Zoological Society of London, UK., London, UK

- Handbook for eelgrass restoration in Sweden: Provides detailed guideline to eelgrass restoration including site evaluation and selection, consultation and permitting, harvesting and planting, to monitoring and evaluation of results. Moksnes, P-O., Gipperth, L., Eriander, L., Laas, K., Cole, S. & Infantes, E., 2021. Handbook for eelgrass restoration in Sweden - National guideline. Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management Technical Report, Report number 2021, 5, 111.

- Management and restoration of eelgrass in Sweden: Addresses ecological, legal and economic aspects of management and restoration of eelgrass in Sweden. Moksnes, P-O., Gipperth, L., Eriander, L., Laas, K., Cole, S. & Infantes, E., 2016. Management and restoration of eelgrass in Sweden

Saltmarsh guidance

The UK & Ireland Saltmarsh Restoration Handbook is currently in preparation and will be published in 2021 and will describe all types of saltmarsh restoration techniques, provide guidance on target setting, success criteria, project timelines, licencing and policy considerations and post-development monitoring. The project report associated with this guidance document (Chambers et al., 2022) provides a substantial amount of further guidance on saltmarsh enhancement and experience from case studies. The current key guidance documents of relevance to enhancement in Scotland are listed below.

- Saltmarsh restoration in the UK and Ireland: Practical guidance on restoring and creating saltmarsh habitat. Hudson, R., Kenworthy, J. and Best, M. (eds) (2021). Saltmarsh Restoration Handbook: UK and Ireland. Environment Agency, Bristol, UK.

- Saltmarsh Management Manual (England and Wales): Detailed guidance on how saltmarsh condition should be established and the process for developing the most appropriate programmes for management based on site-specific factors. Defra and Environment Agency, 2007. Saltmarsh Management Manual. Joint Defra / Environment Agency Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management R&D Programme. R&D Technical Report SC030220.

- Salt Marsh Restoration and Monitoring Guidelines: Guide restoration projects and identify and address common shortcomings noted in previous restoration projects. Niedowski, N.L., 2000. Salt Marsh Restoration and Monitoring Guidelines. NOAA Coastal Services Centre, Charleston, SC, USA, 187pp.

Coastal sand dune guidance

The UK Sand Dune Managers Handbook provides guidance on a wide range of management actions on dunes, which are relevant to restoration and all forms of habitat enhancement. The project report associated with this guidance document (Chambers et al., 2022) provides a substantial amount of further guidance on coastal sand dune enhancement and experience from case studies. The current key guidance documents of relevance to enhancement in Scotland are listed below.

Further key information on coastal sand dune enhancement guidance

- Beach Dunes - a guide to managing coastal erosion in beach / dune systems: Dune procedures management measures. NatureScot (previously SNH). 2000.A guide to managing beach / dune systems

- The Sand Dune Managers Handbook: Provides information on the latest approaches in sand dune management. UKCEH, UK Sand Dune And Shingle Network, Plantlife, and Dynamic Dunescapes partners (2021). The Sand Dune Managers Handbook. Version 1, June 2021.

To download the project assessment form please go to the marine and coastal enhancement projects in Scottish inshore waters - project assessment form page.

Acronyms

CES Crown Estate Scotland

FHI Fish Health Inspectorate

GIS Geographical Information System

INNS Invasive Non-Native Species

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature

LNR Local Nature Reserve

MP Member of Parliament

MPA Marine Protected Area

MSP Member of the Scottish Parliament

NAVFAC Naval Facilities Engineering Command

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NSRF National Species Reintroduction Forum

PMFs Priority Marine Features

ROAM Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology

SAC Special Area of Conservation

SEPA Scottish Environment Protection Agency

SPA Special Protection Area

SSSI Site of Special Scientific Interest

UKCEH UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology

WGS World Geodetic System

WRI World Resources Institute