Information Note - Marine Habitat Enhancement, Recovery, Restoration and Creation in Scotland: Terminology and Examples

This information note clarifies how NatureScot applies the various definitions for actions associated with marine habitat enhancement; informs our approach in this field; and sets the scene for future research and casework.

Interest in marine habitat enhancement has been increasing in recent years and is becoming a growing part of marine work for NatureScot. This information note has been prepared to clarify how NatureScot applies the various definitions for actions associated with marine habitat enhancement; informs our approach to this field; and to set the scene for future research and casework. Whilst use of terms relating to this field may vary amongst practitioners, it is important that NatureScot has clear definitions to inform the organisation’s stance for casework and advice. The definitions in this document relate to how these terms are used in the marine environment.

Broadly speaking, responsibly carried out enhancement activities may fit with the Conservation Objectives for protected features in MPAs. For some of those protected features that have ‘recover/restore’ conservation objectives, these activities may be crucial for the MPAs to achieve improved condition and status. The National Marine Plan provides a wider policy framework related to these activities. Enhancement actions may also assist with, for example, aspirations for positive effects for biodiversity, building resilience and addressing climate change impacts in Scottish waters.

NatureScot has a responsibility to ensure our advice is based on the best evidence available at the time; that projects are carried out according to best practice; and that consideration is given to Scotland’s marine environment and Priority Marine Features, and the whole spectrum of protected features in the Scottish MPA Network.

Introduction

This document clarifies how NatureScot applies the various definitions for actions associated with marine habitat enhancement; informs our approach in this field; and sets the scene for future research and casework.

In recent years, habitat enhancement, regeneration, restoration and creation have become increasingly hot topics in the marine environment. There is some confusion surrounding the precise definitions of these terms and there is a tendency for them to be used interchangeably. The terms featured in this document may also be applied to actions relating to a particular species, together with a number of other terms such as reintroduction and conservation translocations. These require separate discussion and definition and this paper therefore only deals with marine habitats.

Under Part 5 of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, “Marine Protection and Enhancement: The Marine Protection Area”, conserving a feature in relation to a Marine Protected Area (MPA) may include “enabling or facilitating its recovery or increase”. Scotland’s National Marine Plan (Scottish Government, 2015) sets out wider policies and drivers for the conservation and enhancement of habitats. The Plan uses the terms “enhancement” or “enhancing” over a broad spectrum of the topics relevant to marine planning. Where provision is made for enhancement in the context of recovery or regeneration of ecosystems, habitats and species, then the Plan sometimes qualifies this with the phrase “where appropriate” or similar wording. NatureScot would also use “where appropriate” as these activities represent only part of a suite of conservation actions that can be taken, including “do nothing”. Appendix 1 provides the wording of the relevant sections of the Plan for reference.

Drivers for habitat enhancement, regeneration, restoration and creation include:

- Biodiversity conservation and enhancement

- Redressing damage and other degradation to habitats

- Environment quality improvement

- Ecosystem function and services

- Climate change issues

- Coastal and marine management

- Recreating lost habitats

- Creating habitats in new areas

- Marine development

Positive effects for Biodiversity and Environmental Net Gain are being discussed in marine planning and development as approaches to encourage developers to deliver a wider range of biodiversity or environmental benefits (e.g. flood risk management) over and above what is considered to be needed as mitigation for the impacts of the proposed development. This may in the future lead to revisions of Scottish Planning Policy and the National Planning Framework (NPF 4). Compensation and mitigation measures associated with marine development may include restoration or habitat creation. In terms of actions that marine industries may take, there will be differences in measures and approaches depending on the following:

- Mitigation – project level measures required to reduce significant impacts identified during the EIA process;

- Compensation – project level compensatory measures that are required due to the work having an adverse effect on site integrity to one or more Natura sites/ features; and

- Enhancement – work that developers may do in addition to any mitigation or compensation required (this may take place in the same location as the development or elsewhere).

The Dutch, for example, are formulating a Catalogue of National Inclusive Design Options, which includes actions such as European native oyster restoration, for offshore developments. For Scottish marine developments, a possible Environmental Enhancement Fund is being developed, which would be a major driver for enhancement work.

In terms of ‘nature-based solutions’, habitat enhancement has the potential to play a key role in both addressing the Climate Emergency and the Biodiversity Crisis. In April 2019, the First Minister of Scotland declared a Climate Emergency, emphasising that Scotland would ‘live up to our responsibility to tackle it’. This was backed up by a statement to Scottish Parliament which highlighted the need for transformative change. The climate change emergency may mean that drivers for enhancement are magnified and may override other considerations. At around the same time, the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystems (referred to as the IPBES report, IPBES, 2019) was published which in turn led to reporting of a global Biodiversity Crisis. The report highlights key drivers of change, with numerous references to restoration, including the societal and economic benefits that can be achieved through ecological restoration.

New strategies, for example, linked to the post-2020 Convention on Biodiversity and OSPAR’s increasing focus on more restorative targets from 2020 onwards, may also further drive the impetus for enhancement and restoration.

Intervention such as enhancement, restoration and creation of habitats may not always be the most appropriate action – for example, there are natural cycles of secession amongst habitats (e.g. seagrass) and some habitats are ephemeral (for example, serpulid and Sabellaria reefs) and active intervention could be viewed as undesirable interference with natural processes. The Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations (National Species Reintroduction Forum, (2014) has become embedded as best practice for work in Scotland, for example, in relation to the reintroduction of beavers), and must be used when planning enhancement projects and applying for any relevant licence which would be required from Marine Scotland or NatureScot.

In view of the increasing interest in investing in enhancement projects and activity in, for example, native oyster restoration in Scottish waters, it is timely for us to set out NatureScot’s understanding of and position on marine enhancement policies. From NatureScot’s point of view, our first priority must be to protect the extant features and to ensure that, where initiatives are proposed for habitats and species, our advice is based on the best evidence available at the time. NatureScot is supportive of enhancement work but also mindful of the organisation’s responsibilities and ensure that schemes follow best practice and do not lead to negative effects on other equally important features or strategic goals (such as carbon sequestration and storage).

Part 1: Terminology

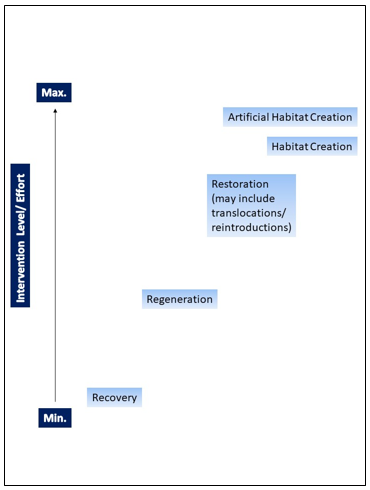

Figure 1 illustrates the commonly used terms used in connection with enhancement and restoration and demonstrates the increasing level of intervention required for each type of enhancement activity. Enhancement, rightly or wrongly, tends to be used a catch-all term. Each term is discussed in this section.

Figure 1: Diagram illustrating a perceived hierarchy of initiatives for habitats. Enhancement tends to be used as catch all/ overarching term for all these actions. Recovery represents the most passive form of enhancement (i.e. removing pressures) through to restoration, which represents the highest level of intervention and may necessitate, for example, conservation translocations. Habitat creation is divided into two – the first taking a more natural approach to creating e.g. saltmarsh, and then artificial habitat creation which may include addition of artificial substrata.

Summary of terms and NatureScot interpretation of definitions

This section summarises the NatureScot interpretation of the terms used in relation to habitat enhancement. Fuller explanations of the definitions for these terms, their general use and NatureScot’s interpretation are given below the definitions.

Habitat Enhancement: This term is applied in relation to those actions that aim to improve the quality, size or geographic distribution of a habitat.

Habitat Recovery: To be used in relation to actions taken to enable a habitat to overcome damage or other disturbance and reach a better state, rather than trying to “turn the clock back”. This is seen as a relatively passive process involving removing pressures and allowing the habitat to repair naturally.

Habitat Regeneration: This still conveys a process but with possibly low level interventions taking place alongside removing pressures. The term regeneration can also be used where there is active fishing (see Part 1(ii) for more explanation).

Habitat Restoration: NatureScot consider the term “restoration” to be applicable to projects entailing a high level of intervention, such as those rebuilding a habitat or reintroducing an ecosystem engineering species to assist with enhancing a habitat into a location from which it has been extirpated and where re-establishment could not occur without assistance.

Habitat Creation: Habitat creation can be used in two different contexts – one using more natural approaches and substrata, for example, creating saltmarsh as part of managed realignment work; and one using artificial substrata or creating habitat where it was not historically present, for example, in offshore marine developments. It is NatureScot’s view that it may not be the best choice to default to placing hard substrata where none is already or was previously present. It could, for example, be more valid to manage or create habitat to encourage other threatened species.

Rewilding: This term refers to restoring processes and functions in very large, landscape/ ecosystem scale projects. Scientifically and scale wise, marine habitat enhancement is at too small a scale currently for this term to be applied.

Remediation: This term is not relevant to habitat enhancement in the UK as it tends to be used more to convey the actions required in relation to chemical/ pollution incidents or requirements of EIAs for marine development.

i) Habitat enhancement

NatureScot interpretation: The term “enhancement” tends to be used as a broad term encompassing various levels of intervention in relation to marine habitats. NatureScot apply this term in relation to those actions that aim to improve the quality, size or geographic distribution of a habitat that is already present at a location.

There appears to be no set definition for the term “habitat enhancement” in use in Scotland or the rest of the UK. The USA, however, has created a legal definition – “habitat enhancement” is defined as “the manipulation of the physical, chemical or biological characteristics of a habitat to change a specific function or seral stage of the habitat” (see for example US Legal, 2019).

“Habitat enhancement” appears to be being used in the UK and the rest of Europe as an overarching/ coverall term for the different activities encompassed within the field of regeneration, recovery and restoration. Scotland’s National Marine Plan uses enhancement rather than other terms such as restoration throughout the Plan, both in association with conservation-orientated subjects such as MPAs and PMFs, but also with regard to general improvement of the marine environment and economy (see Appendix 1).

Enhancement may be used where a habitat or species is already present and taking action to improve its status. For habitats, the term “enhancement” may be especially applicable to projects where increasing the size or geographical distribution of biogenic habitats (e.g. seagrass, saltmarsh or shellfish beds) is possible and potentially beneficial. It may also be applied to projects at a location where the habitat is present but degraded in quality and/or reduced in area from its original extent. The term may also sometimes encompass activities where there is uncertainty over whether the habitat was previously present in that location and a general improvement of the local environment or provision of particular ecosystem services is desired.

It is worth noting that “remediation” is sometimes used in this regard in the USA. However, NatureScot would seek to avoid the use of this term within the areas covered by this paper because, in the UK, remediation tends to be used more to convey the actions required in relation to chemical/ pollution incidents or requirements of EIAs for marine development.

ii) Habitat recovery and habitat regeneration

NatureScot interpretation: Recovery and regeneration are often used interchangeably. However, NatureScot make a clear distinction between the two terms. The term “recovery” should be used in relation to actions taken to enable a habitat to overcome damage or other disturbance and reach a better state, rather than trying to “turn the clock back”. This is seen as a relatively passive process involving removing pressures and allowing the habitat to repair naturally. The term regeneration is regarded as still conveying a process but with possibly low level interventions taking place alongside removing pressures. The term regeneration can also be used where there is active fishing (see the final paragraph of this section).

In NatureScot, the terms “recover” or “restore” are also used in the context of Conservation Objectives for protected features of MPAs, SACs and SPAs where protected features have experienced deterioration and are in an unfavourable condition. Where features are not in a favourable condition the Conservation Objectives will seek to restore/recover the protected feature. Where restoring/recovering the protected feature is not possible at a site level, the site specific advice seeks to ensure the conditions within the site are appropriate to support recovery. A literature review carried out for NatureScot by Mazik et al., (2015) identified wide variation in the use and interpretation of the term “recovery”. Whilst some authors regarded recovery as a return of an impacted habitat to its previous condition, others use recovery to describe both a process and an outcome. Also, different definitions have been proposed as applicable at different scales or to individual species, communities and habitats.

For marine habitats and species, NatureScot regards the terms ‘recovery’ or ‘regeneration’ as conveying a process, as well as the concept of taking appropriate actions which create a positive direction of travel to promote an improved status or condition of the impacted feature. The term “Recovered” would be the end point of this process (Mazik et al., 2015), with the caveat that the baseline at the point the Conservation Objectives were set may not necessarily be the point that can be reached in the future. The new Conservation and Management Advice documents for SACs, SPAs and MPAs being produced by NatureScot provide additional information on the recovered condition we anticipate achieving for protected features in unfavourable condition, where recovery is possible. Note that NatureScot has used the definition of recovery (as an endpoint) proposed by MarLIN (2013) for the purposes of sensitivity assessments in FeAST: “a habitat, biotope or species which has undergone disturbance or damage returns to a state close to that which existed before the activity or event caused the change”.

The term habitat recovery is also used in relation to coastal processes and flooding and offshore infrastructure. However, Scotland’s National Marine Plan makes reference to “recovery” mainly in the context of resources and other economic topics (Appendix 1).

It is common to manage pressures within the marine environment by, for example, removing fishing activity. In this sense, “recovery” is therefore taking action to bring a habitat to an improved status after it has been damaged or otherwise impacted. An example of this would be in Loch Carron where there was damage to flame shell beds from scallop dredging. Action was taken in the form of establishing an MPA and fisheries management measures to remove the damaging pressures and allow the protected feature to recover naturally.

The inherent ability of impacted communities to recover following the removal of pressures is one of the drivers for the adoption of this approach to marine environmental management. It is implicit in the use of the term that the recovery state should be better than when the pressure was acting upon the habitat. However, it is important to remember that often for marine habitats there is the issue of shifting baselines and variation amongst locations and it may therefore be difficult to define precisely what constitutes a “better” state. The aim of reducing or removing pressures should be to aid recovery. Removal of a pressure should not cause more disturbance or damage than leaving the pressure in place.

In contexts where there may be sensitivities, e.g. in relation to habitat enhancement activities where there is active fishing, either for the species or other target species, in the area of a proposed project, then the use of “regeneration” may be less controversial than “recovery” and may better convey the implication of both potential environmental and socio-economic benefits of engagement with the process to stakeholders.

iii) Habitat restoration

NatureScot interpretation: NatureScot consider the term “restoration” to be applicable to projects entailing a high level of intervention, such as those rebuilding a habitat or reintroducing an ecosystem engineering species to assist with enhancing a habitat into a location from which it has been extirpated and where re-establishment could not occur without assistance.

The Society for Ecological Restoration defines “ecological restoration” as an “intentional activity that initiates or accelerates the recovery of an ecosystem with respect to its health, integrity and sustainability.” This term has been widely applied to the terrestrial environment where, generally, there is often a clearer understanding of the un-impacted form of the habitat. In the marine environment, the pristine state of a habitat is likely to be less clear and it is therefore important that restoration projects acknowledge this and set realistic goals. Additionally whilst some species/ habitats seem to be attracting large amounts of attention in terms of restoration potential in Scottish waters, equally important and valid species/ habitats may be being overlooked. NatureScot therefore aims to adopt a balanced, evidence-based response when approached for advice on proposed projects.

Restoration implies a level of intervention that can require high levels of investment of both time and money. This influences the habitat types for which restoration efforts would be practical or cost-effective. These currently tend to be intertidal/ nearshore habitats such as saltmarsh, seagrass or native oysters. There are examples from the USA of projects, such as the Green Harbors Project, that include combinations of all three of these habitats (see for example, Frankić, 2015). Restoration project aims may include biodiversity targets or adding value to ecosystem services such as water quality, nursery areas for fishery target species, coastal defence or carbon sequestration and storage. An example of biodiversity target would be the DEEP Project in the Dornoch Firth which is aimed at reintroducing native oysters into an area within their natural range from which they have been extirpated. There is, also growing interest in restoring habitat in offshore areas, sometimes in conjunction with marine developments such as windfarms.

Where a species or habitat has been extirpated, this means that projects would need to bring in species and materials from other sources. This may only involve one species or multiple species, for example for combined seagrass, saltmarsh and oyster restoration. The distinction between habitat restoration and reintroducing a species (e.g. via translocation) may become blurred when this involves an ecosystem engineer such as native oysters (Ostrea edulis) and the act of reintroducing the species is a necessary part of re-establishing the habitat that they create.

Whether the organisms are sourced from the wild or from hatcheries/ farms, there are inherent risks with this process, including the spread of parasites, pathogens and invasive non-native species. NatureScot would therefore expect projects to adhere to the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations (National Species Reintroduction Forum, (2014). Based on the IUCN’s “Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations”), the code has become embedded as best practice for work in Scotland (for example, in relation to the reintroduction of beavers), and must be used when applying for any relevant licence from Marine Scotland or NatureScot. The code is expected to be revised within the next two to three years and to have more reference to reintroductions in the marine environment.

One of the main limiting factors for restoration projects at the present time is obtaining sufficient organisms and material. Removal of animals from the wild to stock restoration projects is not recommended as this can have a negative impact on the donor population. Hatcheries are increasingly being couched in terms of restoration (e.g. lobsters, native oysters). There are, however, genetic bottleneck implications of the use of hatchery stock raised from relatively small numbers of broodstock. There is also the inherent risk with both wild and hatchery sourced stock in terms of movements of invasive species such as Didemnum vexillum. For all species (shellfish, seagrass, etc.), decisions on, for example, the use of seed from local donor populations or seed mixes from other locations need to be clearly evidence based and risks fully considered.

For restoration projects at the current time, it is clear from agencies and restorers that the existing governance, policy and consenting/licensing environment is not sufficient to meet the needs of such projects. Currently in the UK, for example, there are differences in approaches amongst the different administrations and regulations that can be applied are largely generic or aquaculture/ fisheries driven rather than restoration specific. With the burgeoning interest in restoring marine habitats, there is ongoing discussion between government and other bodies to draw up policies and legislation specifically aimed at restoration activities. It is important, however that, except in exceptional circumstances, the drive to restore and any new policies to facilitate restoration do not achieve this at a negative cost to extant habitats or other protected features.

iv) Habitat creation

NatureScot interpretation: Habitat creation can be used in two different contexts – one using more natural approaches and substrata, for example, creating saltmarsh as part of managed realignment work; and one using artificial substrata or creating substrate where it was not historically present, for example, in offshore marine developments. It is NatureScot’s view that it may not be the best choice to default to placing hard substrata where none is already or was previously present. It could, for example, be more valid to manage or create habitat to encourage other threatened species.

“Habitat creation” is used in terrestrial terms and also for activities such as establishing saltmarsh through managed realignment, etc. which would be expected to be occurring in areas where the existing habitat has declined or had previously been present. The term “enhancement” is also often used in the context of habitat creation. In the context of actions to assist with combating climate change, Scotland’s National Marine Plan is quite clear in stating policy regarding habitat creation “In some cases, compensatory habitat creation or enhancement may be possible and should be considered as a last resort if significant harm cannot be avoided” (Appendix 1).

Artificial habitat creation is regarded by NatureScot as a distinct action from the way in which habitat creation is used in terrestrial or managed realignment contexts as it relates to the placing of artificial substrata or structures in the marine environment. These actions may be carried out for a wide variety of reasons, ranging from mitigation measures for marine developments such as offshore wind or resource extraction to creating nursery areas for fishery target species or places for recreation activities (such as the sinking of a vessel to create diving opportunities).

Artificial habitat creation is often sold on perceived “reef” effects. NatureScot is of the view that there are relatively few circumstances in Scottish waters where artificial habitat creation proposals such as artificial reefs can be justified on the basis of biodiversity conservation objectives (restoration of marine habitats or species). Where the aim of artificial habitat creation may be, for example, enhancing recreational diving opportunities, then this may be valid. In such cases, the key consideration would be the location of the feature, to ensure that it would not have any negative effects on other activities or the marine environment. In most cases, this would likely involve the loss of existing habitat, which NatureScot would not support. However, whilst NatureScot would advise this to be avoided, there may be occasions when projects may still go ahead. NatureScot also takes the view that whilst some species do aggregate around or colonise such structures and may derive some benefit from this, the population-level benefits of artificial structures are largely speculative. There are also inherent risks related to this practice, including the potential for structures to act as “stepping stones” for invasive non-native species.

Artificial habitat creation also becomes relevant when considering decommissioning of oil and gas infrastructure. Whilst NatureScot takes the view that removal of pressures or physical structures should not cause more disturbance than leaving that pressure or structure in place, however, international policy currently supports the total removal of structures. There may be future changes to this policy which could give opportunities for accessing wider biodiversity benefits of leaving structures in place and NatureScot would need to input into this process to ensure that all aspects of these activities are considered including the Carbon cost of removing these structures and the impacts of their removal upon climate change. Changes to designs for offshore renewables that would include space for biodiversity enhancement are envisioned and would also likely require NatureScot input.

Technically, some restoration initiatives may be better described as habitat creation, as there is not necessarily evidence that the habitat was originally present in the location. In the Netherlands, for example, there is a growing drive to use offshore windfarms as sites for restoration projects of European native oysters and blue mussels. This is partly influenced by spatial considerations because the Netherlands’ territorial waters occupy a small and very busy area of the North Sea. Space to carry out projects is therefore at a premium and there is a drive to take opportunities wherever they arise.

v) Rewilding

NatureScot Viewpoint: This term refers to restoring processes and functions in very large, landscape/ ecosystem scale projects. Use of this term should be treated with caution for marine habitat restoration. Scientifically and scale wise, marine habitat enhancement is at too small a scale currently for this term to be applied.

More commonly associated with very large scale terrestrial conservation projects (see Rewilding Europe and Rewilding Britain websites for examples), this term is starting to drift into the marine habitat restoration field. The Rewilding Britain website gives COAST, Arran as an example of rewilding. However, both in scale and scientific evidence, marine habitat enhancement in European waters is currently not at the stage where this term would correctly be applicable. It is likely to become more widely used as time goes on, and NatureScot will consider the application and use of this term when needed.

Part 2: Other Considerations for Enhancement Projects

i) Defining Goals and Targets

NatureScot Viewpoint: Enhancement initiatives should set clear, realistic goals and targets from the outset. Whilst these will vary amongst projects, there should be clear evidence that the actions to be taken are necessary and appropriate.

In the marine environment, pressures may have been acting upon habitats for decades or even hundreds of years. Also, habitats that may appear to have undergone no human intervention may historically have been altered by anthropogenic activities. This can make it difficult to have a clear understanding of the level to which habitats have been impacted and identify suitable reference sites. There can therefore be significant difficulty surrounding describing and finding pristine reference examples of a particular habitat.

Even where the pristine condition of a habitat is known, it can be difficult to be certain whether enhancement could achieve this state, given changing environmental conditions (either in the past or which may occur in the future through climate change). It can therefore be misleading to suggest that a marine habitat can be restored to some halcyon state. However, even in impacted marine environments, the habitat may retain many of the physical characteristics and components of the associated community or an ability for those component organisms to recover.

It is essential that projects set clear, realistic goals and targets from the outset (failure to do this has been considered to contribute to the lack of success of some projects). Measuring success or failure also needs to be a part of project planning and can be measured using biodiversity or ecosystem function as part of a carefully designed monitoring programme. This need for clear goals and targets is relevant to any project to which any of the terms defined in this paper is applicable, including “enhancement” projects where there is a direction of travel rather than a clear endpoint. There may also need to be policy, legislation and monitoring put in place to record what is happening and adapt management strategies accordingly.

Potential pressures on the ‘enhanced’ environment need to be considered upfront, to ensure that costly projects to restore or create a habitat are not damaged or destroyed by pressures that have not been managed or removed.

ii) Building resilience

NatureScot Viewpoint: NatureScot view building resilience as an outcome of enhancement actions rather than an enhancement action.

We live in an ever changing world and resilience generally refers to an ability to withstand pressures or the ability to recover from the impacts (short- or long-term) of a pressure(s). It also refers to a species’ or habitat’s capacity to absorb or adapt to a pressure or change whilst maintaining its essential function(s). The definition of resilience may change depending upon scale (e.g. individual or landscape scale). Resilience can be based on a range of factors and scales - genetic, seed/ source, physical, or system - where more diverse systems and communities generally exhibit greater resilience than less diverse ones. Systems which have developed in environments with greater ongoing change and instability tend to be more resilient than systems which developed in very stable static environments. The resilience of most of Scotland’s marine habitats and species will also be affected by the issue of climate change.

In view of threats such as climate change, ensuring that there are replicate examples of a particular habitat throughout Scottish waters, possibly via enhancement activities, may assist with building resilience and ensuring survival of that habitat, even if individual locations may be negatively affected. Connectivity may also assist with building and sustaining resilience by creating sources and sinks for e.g. larval settlement and by maintaining greater genetic diversity, and hence resilience. Removal of other pressures may also help maximise an individual’s, population’s or habitat’s ability to adapt to and withstand climate change impacts.

In order to build resilience into populations, especially of threatened/ endangered species, it may be desirable or necessary to restore species or habitats back into their natural range (see Page 15 of the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations for an explanation of the Scottish legal difference between natural and native range). However, building resilience may not require such high levels of intervention – it may just need prevention or removal of pressure(s).

Within systems, individual habitats change. The ability of systems to adjust to change decreases when stability is imposed. Increasing or maintaining resilience of systems therefore requires not intervening in natural processes of change, and certainly not trying to force a system to maintain a state chosen by us as ‘the natural state’ despite changing conditions.

References

Ahmed & Glaser, (2016). Can “Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA)” adapt to climate change in coastal Bangladesh? Ocean & Coastal Management 132:120-131

Blue Carbon Initiative (2019).

Buck, B.H., Troell, M.F., Krause, G., Angel, D.L., Grote, B. & Chopin, T., 2018. State of the Art and Challenges for Offshore Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). Frontiers of Marine Science. 5:165. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00165

Frankić, A., 2015. Oyster Reef Restoration Project 2011-2014.Town of Wellfleet. USDA Report.

IPBES, 2019. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services.

Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN). 2013. Sensitivity Assessment Rationale. Accessed 2nd August, 2013.

Mazik, K., Strong, J., Little, S., Bhatia, N., Mander, L., Barnard, S. & Elliott, M., 2015. A review of the recovery potential and influencing factors of relevance to the management of habitats and species within Marine Protected Areas around Scotland. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 771.

National Species Reintroduction Forum (2014). The Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations. Scottish Natural Heritage. 80 pp

Scottish Government, 2015. Scotland’s National Marine Plan – a single framework for managing our seas. Scottish Government Publication, 144 pp.

US Legal, (2019). Habitat Enhancement Law and Legal Definition.

Appendix: Scotland's National Marine Plan (Scottish Government, 2015)

The term “enhancement” is used in the Plan not only in relation to species and habitats but also in relation to nutrient enhancement and benthic impacts of aquaculture operations and in terms of economic concerns, tourism, and infrastructure, e.g. the electricity grid.

The term “recovery” is used in the Plan mainly in the context of the economy and resources such as fish stocks and oil reserves.

Specific mentions of the terms “enhancement”, “enhancing” or “restoration” in the context of habitats or species

Section 2: Marine Planning in Context – National and Regional

2.9 This Plan sets out some guidance specifically for regional planners in Chapters 3 and 4 and at the end of each of the sector chapters. The basic legislative requirements for regional plans include:

- Stating the contribution of MPAs and other designated areas to the protection and enhancement of the region.

Section 4: General Policies

Gen 5 Climate change: Marine planners and decision makers must act in the way best calculated to mitigate, and adapt to, climate change.

4.19 Reducing human pressure and safeguarding ecosystem services such as natural coastal protection and natural carbon sinks (e.g. seagrass beds, kelp and saltmarsh) should be considered. In some cases, compensatory habitat creation or enhancement may be possible and should be considered as a last resort if significant harm cannot be avoided. Appropriate proactive opportunities for enhancing natural carbon sinks and allowing natural coastal change where possible should also be considered.

Gen 7 Landscape/ seascape: Marine planners and decision makers should ensure that development and use of the marine environment take seascape, landscape and visual impacts into account.

4.29 In making these judgements, planners and decision makers should have regard to the qualities of the location in question, including any designation. More generally, the siting and design of a development should take account of the local landscape/ seascape character and quality. Potential effects on landscapes and seascapes, including cumulative effects should be considered and developers should seek to minimise adverse impacts through careful planning and design, considering the services which the natural environment is providing and maximising the potential for enhancement.

Gen 8 Coastal process and flooding: Developments and activities in the marine environment should be resilient to coastal change and flooding and not have unacceptable adverse impact on coastal processes or contribute to coastal flooding.

4.37 Wherever possible, flood risk management and coastal protection solutions should work with natural processes and features, encouraging managed realignment of coastal habitats such as sand dunes, salt marshes and mudflats. The protective role of geodiversity, geomorphological and natural features such as kelp beds, biogenic reefs and sandbanks should also be considered alongside opportunities for recovery and enhancement.

Living within environmental limits - Gen 9 Natural Heritage

Development and the use of the marine environment must:-

- Comply with legal requirements for protected areas and protected species;

- Not result in significant impacts on the national status of Priority Marine Features;

- Protect and where appropriate enhance the health of the marine area.

4.39 Scotland’s marine natural resource, biodiversity and geodiversity is a valuable asset delivering a wide range of ecosystem services (see Annex A) which provide a large stock of natural capital and support a variety of recreational and economic activities. Nature conservation measures play an integral role in protecting and enhancing the marine natural environment, ensuring it is healthy, biologically diverse, resilient and productive and that ecosystems continue to provide social, economic and wider benefits for people, industry and society.

4.40 Marine planners and other decision makers should act in the way best calculated to further the achievement of sustainable development and use, including the protection and, where appropriate, enhancement of the health of the Scottish marine area. The Strategy for Marine Nature Conservation in Scotland’s Seas sets out aims and objectives to achieve this. The Strategy outlines a three-pillar approach to conservation: site protection, species conservation and wider seas policies and measures.

4.41 A network of well managed marine protected areas is being established to meet national objectives and help deliver and ecologically coherent MPA network in the North East Atlantic, contributing to the protection and enhancement of the area to which this Plan applies. The network will comprise of newly designated Marine Protected Areas (Map 4) as well as Natura Sites and marine components of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Ramsar sites. The management requirements of each of these designation types must be met. These sites, together with other protected areas will make a significant contribution to the protection, enhancement and health of the marine area. Improved health of the marine environment will also lead to increased resilience of ecosystems to climate change.

4.56 Priority Marine Features are species and habitats which have been identified as being of conservation importance to Scotland. Most are a subset of species and habitats identified on national, UK or international lists. They provide new focus for marine conservation in Scotland. The list does not currently include wild bird species, which are protected under the EU Birds Directive. Impacts of development and use on the national status of Priority Marine Features must be considered when decisions are being made, taking account of the advice of Statutory Advisors. Where planned developments or use have the potential to impact PMFs, mitigation, including alternative locations, should be considered. Actions should be taken to enhance the status of PMFs where appropriate.

Part 4: The future

11.39 The Scottish Offshore Renewables Research Framework should provide a collaborative and co-ordinated research programme supporting the sustainable development of marine renewable industries and better inform future marine planning and decision making for offshore wind and marine renewable energy development. A future co-ordinated national, regional and project specific environmental monitoring strategy will also be useful to identify potential opportunities for enhancement and recovery of ecosystem services in the exclusion zones around offshore energy generation sites (i.e. restoration and improvement on habitats damaged during the construction process).