Guidance on Nature Finance Opportunities for Land Managers in Scotland

Purpose of this guidance

This guidance has been written to help managers of rural land in Scotland consider the opportunity of new sources of private finance for the stewardship of land, water and nature.

The revenue and investment considered in this guidance is often referred to as ‘nature finance’ or ‘natural capital investment’. It can help land managers to become more resilient, to achieve net zero, to grow the financial value of their assets, and to make additional positive contributions to the life of rural communities.

This guidance is intended to provide an introduction to the topic, rather than a definitive guide to all of the many technical and legal aspects of new sources of finance for each type of land manager in Scotland. Suggestions for sources of professional advice are provided as part of this guidance.

Focus

The focus of this guidance is new sources of private finance for improvements in the stewardship of rural land in Scotland. Public finance, philanthropy and charitable funding are expected to continue to have an important role alongside changes in the availability of money from private sources.

There are two parts to nature finance:

- The supply, sale and purchase of ecosystem services (the direct and indirect contributions of the natural environment to people’s wellbeing). In this process, environmental outcomes are sold to private entities seeking to secure these outcomes. This is sometimes referred to as nature markets or environmental markets. It could include, for example:

- The removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into soils, trees and other vegetation. This could be purchased by a company seeking to offset a portion of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with its activities, its supply chains or its investments.

- The planned use of vegetation or small changes in landform to reduce flood risk. This could be purchased by organisations or local communities seeking to mitigate flood risk.

- ‘Upfront’ investment into activities designed to deliver environmental outcomes. This may include, for example, finance to pay for peatland restoration and the planting of woodland. Where there is a buyer of benefits, investors and banks can provide the finance for upfront interventions that will allow the creation and therefore sale of those benefits – much like financing the capital for any business that has a product that buyers want. Investors will seek a mix of financial returns alongside the environmental and social outcomes.

“Investors will seek a mix of financial returns alongside the environmental and social outcomes.”

Trading in ecosystem services is the foundation for nature finance. Without it, finance for projects and businesses is unlikely to be forthcoming.

Read more about Why nature finance matters to rural land management in Scotland.

Structure

Following this introduction, five Starting points provide tailored introductions to nature finance and key considerations for a set of land manager interests.

A series of Explanations and Case studies provide more detail on specific topics associated with nature-based finance. A book (📖) symbol next to a term indicates that this is explained in the Glossary. The arrow symbol denotes a link to an external website.

The Case studies are an important part of this guidance as they illustrate a range of key opportunities in relation to nature finance.

- The potential for nature-finance to generate benefits for rural communities, especially in terms of employment opportunity. Highlands Rewilding and the Shieling Project are examples of this.

- The diversity of land holdings involved (ranging from the 4 hectare Shieling Project to the diversification of income on the 18,000 hectare estate of the Assynt Foundation).

- The connections between new forums of private finance and environmentally-based tourism. The Trees for Life project exemplifies this.

- The breadth of income streams beyond the initial target revenue source (see for example the financing of peatland on the Lochrosque Estate and the Wyre Natural Flood Management Project).

- The importance of establishing a clear baseline for the condition of natural assets (exemplified by the work of Highlands Rewilding).

Status and revision

This guidance has been drafted by an external contractor team. It has been informed by online consultation events in 2021 and 2022 for rural land managers in Scotland. Nature finance is rapidly advancing in Scotland and beyond. This includes the Investment Readiness in Nature scheme for Scotland that commenced in 2022 with seven pilot projects that are involving a range of land managers. The Facility for Investment ready Nature in Scotland was launched in 2023.

As a result, this guidance will be updated regularly as nature finance project experience is gained, and the priorities of different types of land manager become clear. Feedback on this guidance is encouraged and will be used to revise the guidance in accordance with needs and interests of the many different types of land manager in Scotland. This includes the provision of examples relating to the different types of land manager considered in the preparation of the guidance.

The finance opportunities appropriate to individual land managers in Scotland will depend on their business, their objectives and the local circumstances. For this reason, professional advice should be sought before any changes to land management take place, or any agreements are made that may involve new finance or new obligations. Suggestions for sources of professional advice relating to nature-based finance opportunities are provided in the sources of advice section.

This guidance does not represent a formal policy position of any organisation.

Image of a section of the River Wyre that is part of the natural flood management scheme. Showing riverbank vegetation and surrounding agricultural land. © 2022 Wyre Rivers Trust.

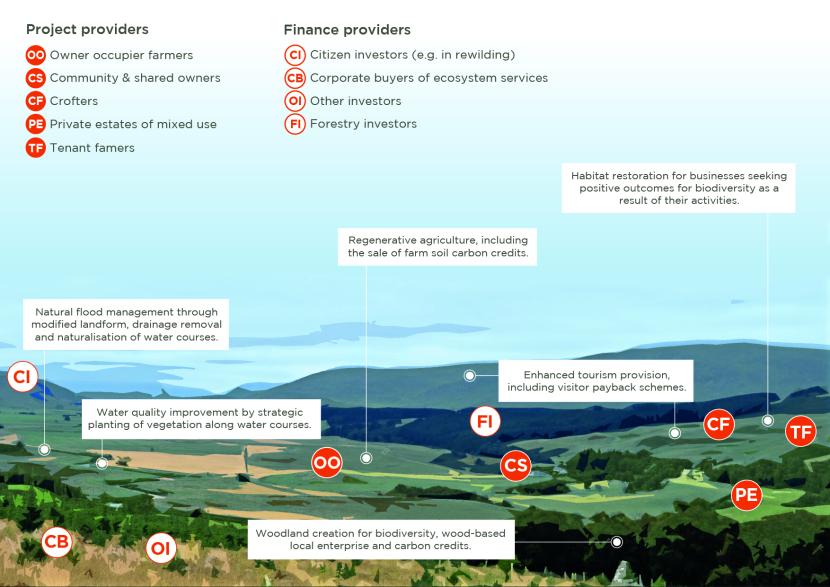

Illustration showing a view of a valley with a large floodplain, comprising mixed land use with woodland, forestry and agriculture. Various nature finance opportunities are identified: Natural flood management through modified landform, drainage removal and naturalisation of water courses. Water quality improvement by strategic planting of vegetation along water courses. Enhanced tourism provision, including visitor payback (📖) schemes. Woodland creation for biodiversity, wood-based local enterprise and carbon credits.

Project providers identified in the diagram are: Private estates of mixed use, Crofters, Community and shared owners, Tenant farmers, Owner occupier farmers. Finance providers identified in the diagram are: Corporate buyers of ecosystem services, Forestry investors, Citizen investors (e.g. in rewilding 📖), Other investors.

Why nature finance matters

Managers of rural land in Scotland have a vital role in maintaining and restoring the natural environment. To date, funding for land managers to deliver enhanced environmental outcomes has come mainly from government, philanthropy and charitable donations, as well as land managers themselves.

Over the last decade, a natural capital approach (📖) has arisen as a means of understanding the economic and social value of the natural environment. This has led to greater awareness of the connection between the work of land managers and their contribution to the natural environment that businesses and wider society desire. Knowledge of this connection is now leading to the identification of new sources of finance. In particular, an increasing number of businesses are prepared to pay land managers to deliver environmental outcomes that fulfil their needs and interests. These outcomes include the recovery of nature, as well as improvements to water quality beyond what is required by government regulation.

Traditional activities associated with the management of land in Scotland will remain important, even as new sources of private income arise. This includes, for example, the provision of recreation, sporting and tourism opportunities, as well as the supply of timber and food. Emerging markets for ecosystem services (📖) offer an additional or alternative means for attracting new finance for activities that support the preservation or restoration of the natural environment.

Nature finance matters because it can help fulfil the ambitions in Scotland for a just transition (📖) towards net zero (📖). The guidance also reflects the importance of partnerships in rural land use and working with rural communities, as identified in Scotland’s Land Use Strategy 2021 to 2026. The case studies provided in this guidance illustrate the opportunity for rural communities, community-based initiatives, charities and microenterprises to be at the centre of nature finance. Larger landowners can facilitate this by enabling communities to purchase land, as has occurred with the Langholm Estate (see the example below).

Nature finance can deliver outcomes desired at the local and national level, such as net zero and nature-positive targets. Through the provision of employment opportunities and by aiding local climate resilience, the pursuit of new sources of finance can help land managers to make additional positive contributions in life of rural communities.

An illustration of nature finance opportunities within a Highland Glen

A view of a Highland Glen with various nature finance opportunities identified: Habitat restoration for customers requiring nature-positive outcomes. Peatland restoration for carbon and water quality improvement. Best practice forestry for long-term carbon storage in trees and timber. Regenerative agriculture with potential premium payments for food products. Enhanced tourism provision associated with nature-recovery, enhanced scenic qualities and ease of access.

Project providers identified in the diagram are: Private estates of mixed use, Crofters, Community and shared owners, Tenant farmers, Owner occupier farmers. Finance providers identified in the diagram are: Corporate buyers of ecosystem services, Forestry investors, Citizen investors (e.g. in rewilding), Other investors.

Public sector agri-environment support

The current Agri-environment Climate Scheme (AECS) of Scottish Government opened for applications in early 2022. Application periods are expected in 2023 and 2024. Alongside this, Scotland is in the process of developing future arrangements for public finance to support agriculture and its contribution to environmental management and the just transition (📖) to net zero (📖). While the design of new arrangements is at an early stage, the interaction between public and private finance will be a key consideration in this.

A greater focus on the measurement and verification of the environmental outcomes from land management activity is a likely feature of both private and public finance in future. Participation by land managers now in schemes involving nature-based finance will help them to prepare for this and, as a result, provide an advantage. It may enable them to find ways in which public finance and private finance can in future be combined, with each source paying for different but compatible outcomes. Examples of such outcomes are: the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the reduction of flood risk and improvements in farmland biodiversity.

Starting points for different types of land manager

Tenant Farmers

Relevance of nature finance

Agricultural tenants can make a vital contribution to climate change adaption and mitigation. They have the capability to restore nature while maintaining high standards of food production from Scotland’s farmland. They may be approached directly by buyers of ecosystem services (📖) or by their landlords. As a result, it is vital that effective relationships and lines of communication are established from the outset.

In the first instance, nature finance for tenant farmers is likely to occur alongside public sector grants and subsidies. For example, existing Tenant farmers will be concerned to ensure the future success and resilience of their businesses. New income streams can be a vital part of this. Businesses in food supply chains may want tenant farmers to help them achieve net zero (📖).

For many tenant farmers, the continuing production of food will be a priority. This may require new approaches to farm business management, as well as investment in artificial structures (such as those used in managing livestock slurry) and digital technology (such as that used in the delivery of nutrients to crops). There is an opportunity to integrate investment in natural features into investment in these technologies.

Key considerations

New opportunities for nature finance must be considered in the light of existing tenancy agreements and the law underlying them. Scotland’s Tenant Farmer Commissioner provides Codes of Practice and guidance relating to the relationship between tenants and land owners. This includes guidance on Securing Tradeable Carbon Credits in an Agricultural Holdings Situation.

In cases where a tenant wishes to pursue an idea for revenue diversification, it will be very important to consider carefully the implications for the landlord. This will mean that the case for participation in a new initiative can be presented to the landlord with a deep understanding of the landlord’s own position and likely concerns.

Landlords may initiate discussions with tenants about new ideas for revenue and investment on or near their farms. Tenants in this situation should ensure they understand fully the obligations and rights they have under their existing tenancy agreements. The best outcomes for both parties are most likely to be achieved by working openly in a spirit of partnership and shared outcomes. There may be other parties with a close interest in the farm as well. Examples include owners of sporting rights, employees, beneficiaries of rights of way (such as utility companies), local conservation or amenity groups or recreational users.

When pursuing nature finance, obligations associated with Government funding support also need to be kept. Once a new system of government agri-environmental support in Scotland has been finalised, the balance between public and private income sources is likely to become clearer. Specific parts of this guidance deal with tenancy requirements, business impact and collaborative working. There are also Explanations of tax implications and contractual considerations. These provide further starting points for a tenant considering new opportunities in nature finance.

Suggested next steps in the guidance – visit the Checklist and Case studies.

Crofters (including common grazings)

Relevance of nature finance

Crofting (📖) is an important form of land tenure in Scotland. Crofters and others sometimes jointly hold a right to allow their livestock to graze on land. Sites where this occurs are known as common grazings (📖).

As an integral part of Scottish rural society, crofters play an important role in stewardship of the environment of the Highlands and Islands. Their local knowledge and skills, together with the extensive common grazings that they are involved with, makes them well-placed to play a central role in the pursuit of nature finance. Specific opportunities include assisting organisations seeking to fulfil net zero commitments (📖) and the offsite provision of new habitat associated with the process of permitting new built development (such as housing or transport infrastructure).

Nature finance may also be an important opportunity to reinforce the overall financial position of a crofter by providing new opportunities for off-croft work in the local economy. Many of the nature finance opportunities and challenges of crofters will be comparable with tenant farmers. However, unlike tenant farmers, crofters have extensive rights in relation to planting and harvesting of woodland. This provides an opportunity through the Woodland Carbon Code.

Given the location of many crofts in areas of peatland, it is likely that graziers may have the opportunity to work with landowners on peatland restoration projects, secured through finance for carbon credits (📖).

Key considerations

Existing crofting law and crofters’ rights and responsibilities will be very important in considering new income opportunities associated with the restoration of natural features.

While crofters may be invited to participate in new schemes, some initiatives designed to attract new income may come from crofters themselves. The scale of investment in relation to the size of crofts means that projects are likely to bring together many different people.

The best outcomes for all parties, the environment and local communities are most likely to be achieved by working openly in a spirit of positive partnership and shared outcomes. Any new income-generating activity must be compatible with that of other crofters within a landscape. Where formal Grazings Committees are in operation, these will have a vital role in the development of new proposals. They could be involved in initiating peatland restoration works. It will also be useful to maintain close relationships with the Crofting Commission, the Scottish Crofting Federation and other organisations interested in crofting.

Specific parts of this guidance deal with crofting and grazing rights and responsibilities, tenancy requirements, business impact and collaborative working. Sections on taxation, structural and contractual considerations are also useful starting points for crofters considering new opportunities in nature finance.

Crofters should consider the need for landlord’s consent for habitat restoration projects designed to attract nature finance. This might usefully be included in discussions about other aspects of a proposal, including the commercial aspects.

Suggested next steps in the guidance – visit the Checklist and Case studies.

Community-based land ownership

Relevance of nature finance

Community-based organisations provide a way in which rural communities as a whole can benefit directly from new sources of income, opportunities for employment and an improved natural environment. Their involvement in nature finance is an important part of the just transition (📖) to net zero (📖).

Community-based landowners may be attractive to investors interested in social as well as environmental outcomes. Nonetheless, landowners with charitable objectives will need to consider potential reputational risks associated with new external sources of income and investment.

The case study in this guidance for the Assynt Foundation illustrates the emerging opportunity of community-based landowners to attract new sources of private finance.

Key considerations

At the start of their consideration of nature finance, it is particularly important that community-based landowners consider the relationship between their strategic objectives and new opportunities for the sale of ecosystem services (📖). In particular, nature finance may involve allocating land to long-term uses that may limit other options in perpetuity. It may also require new skills within an estate management team, especially when negotiating with buyers of ecosystem services and financial services organisations. Infrastructure for renewable energy projects may not be compatible with some types of environmental restoration.

Relationships with other organisations involved in the local community should be uppermost in the early consideration of nature finance opportunities. This includes local authorities and other enterprises; care must be taken in identifying them, engaging them and understanding their needs, interests and capabilities.

Natural capital finance opportunities may bring particular opportunities to progress a wide range of community objectives. These include support for new livelihoods and enterprises, such as those arising through the management of woodland and tourism.

Most of the general guidance on the consideration of the business case and the relationships with other stakeholders will be as relevant to community landowners as to other land occupiers and managers.

Suggested next steps in the guidance – visit the Checklist and Case studies.

When considering nature finance, community landowners should start with a simple appraisal of their existing natural capital assets (📖). This can be as simple as a sketch plan of the property with the key land cover types and environmental features highlighted. This provides an opportunity for dialogue within the local community, ensuring that those who know the land best can share their insight. External support, including through partnerships with research and educational establishments, may help with this process.

Registered charities

Relevance of nature finance

Landowners that are registered charities are well-placed to become involved in nature finance because of their focus on long-term outcomes for people and the environment. There may be reputational benefits to those providing finance or investment to registered charities.

At the start of their consideration of nature finance, it is important that charitable landowners review the likely relationship with the charitable purpose registered with the charity regulator, as well as any restrictions associated with their status as a registered charity. Reputational risks associated with certain sources of private finance should also be considered carefully. It is therefore vital that charities assess what natural capital assets they already have, how they would like to see them managed and what they do (and do not) want in the long and short term. This will all need to be judged against the overarching purpose and objectives of the charity.

Key considerations

Charitable landowners should ensure that they have a good understanding of the existing natural capital assets (📖) present within the land and water for which they have responsibility. This can be as simple as a sketch plan of the property with the key land cover types and environmental features highlighted. This provides an opportunity for dialogue within the local community, ensuring that those who know the land best can share their insight. External support may be required for this, including through the production of natural capital accounts.

Relationships with other stakeholders will need to be uppermost in the early consideration of nature finance opportunities. Care must be taken in identifying them, engaging them and understanding their concerns and ambitions.

Charities should consider carefully whether any new activity that attracts nature finance is supportive of the organisation’s existing purpose and objectives. For example, they must evaluate whether activities to attract new sources of income constitute trading activity by the charity and whether it is set up to deal with this. A new subsidiary company might be needed for this purpose, or there may be one already in existence that can be used. Specialist advice may be needed on this aspect.

Most of the general guidance on the consideration of the business case, relationships with other stakeholders and the implications for capital value (in view of charity responsibilities to maintain assets) will be as relevant to charities as to other land managers.

Suggested next steps in the guidance – visit the Checklist and case studies involving registered charities (including the Langholm Initiative, Assynt Foundation and Trees for Life).

Private landowners (including owner-occupier farmer businesses)

Relevance of nature finance

Nature finance provides diverse opportunities for private landowners and farmers. This includes opportunities to work collaboratively with tenants, as well as other landowners and rural communities.

Key considerations

Knowledge of the natural capital assets relating to an area of privately-owned land is important. Start with a simple appraisal of existing natural capital assets (📖) . This can be as simple as a sketch plan of the property with the key land cover types and environmental features highlighted. External advice may be helpful at this stage.

It will also be useful to make a list of who else needs to be involved. Consider, for example:

- Do you have tenants or other occupiers of your land?

- Do other people have rights over your land like mineral or sporting rights?

- Is the land under any existing obligations as debt security or similar commitments?

- Is your land owned in trust and, if so, who are the trustees and the beneficiaries? If ownership is in trust, landowners should make sure that they are familiar with the terms of the trust concerning what is and isn’t allowed to take place on the property. (These terms are normally contained in the trust deed.)

- Is the land is already subject to environmental requirements, e.g. agreements on protected sites (and requirements to seek consent), or conditions of payments through public schemes like agri-environment schemes?

It is also important to determine whether the land is already subject to environmental requirements, e.g. agreements on protected sites (and requirements to seek consent), or conditions of payments through public schemes like agri-environment schemes.

Taxation status is important to most private landowners and farmers. A key consideration due to the current scope of agricultural property relief from inheritance tax. Additionally, forestry and farming are both treated in specific ways for Income Tax purposes, and it could be important to evaluate the ‘fit’ of any new enterprises with existing arrangements.

Business impacts can be appraised using budgets. Staffing, machinery and investment implications might also need to be considered in the longer term. These reviews might also highlight other areas of the business which might benefit from review and different approaches.

In the longer term, the extent of future commitments and the risk associated with them must also be balanced. This will extend to consideration of the outlook for asset values.

Suggested next steps in the guidance – visit the checklist and detailed prompts for the consideration of nature-based finance.

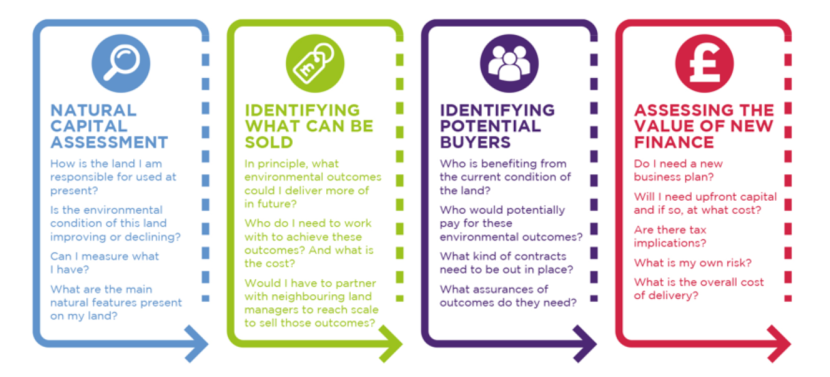

Checklist of considerations for nature finance

The first steps for consideration of nature finance by all types of land manager are shown in the diagram below. Opportunities for involvement in nature finance are likely to become clear only once these steps have been followed.

First steps for land managers when considering nature finance

This diagram shows four steps in securing nature finance. These are:

Natural capital assessment

- How is the land I am responsible for used at present?

- Is the environmental condition of this land improving or declining?

- Can I measure what I have?

- What are the main natural features present on my land?

Identifying what can be sold

- In principle, what environmental outcomes could I deliver more of in the future?

- Who do I need to work with to achieve these outcomes? And what is the cost?

- Would I have to partner with neighbouring land managers to reach scale to sell these outcomes?

Identifying potential buyers

- Who is benefiting from the current condition of the land?

- Who would potentially pay for these environmental outcomes

- What kind of contracts need to be put in place?

- What assurances of outcomes do they need?

Assessing the value of nature finance

- Do I need a new business plan?

- Will I need upfront capital and, if so, at what cost?

- Are there tax implications?

- What is my own risk?

- What is the overall cost of delivery?

A set of detailed prompts for the consideration of nature finance is provided within this guidance in order to help land managers of all types identify opportunities for involvement in nature finance. The level of detail required for each consideration will depend on the type of land manager and the size of the business.

Case studies

The Wyre Natural Flood Management Project

The project is an example of how land managers in a river catchment can come together to attract payments for the ecosystem service of flood risk reduction. It also illustrates how a new legal entity may need to be formed to enable investment and collaboration.

The Wyre Natural Flood Management Project is located in a small river catchment in the Forest of Bowland in Lancashire, England. This location has suffered increased flooding in recent years.

Summary of the key steps from the Checklist.

- Natural capital assessment: extensive hydrological modelling, including assessment of the impact of natural flood management measures on flood risk at the property level.

- Identifying what can be sold: flood risk reduction by storing water on land and slowing its flow towards the river. Additional services such as carbon storage are expected to be sold subsequently.

- Identifying potential buyers: insurance sector, utilities, developers, the local authority and the Environment Agency.

- Valuing new finance: Nine-year loan currently being sought, alongside existing grant funding.

The project was one of four pilots initially funded by Defra, the Environment Agency and Esmée Fairbairn Foundation in 2019 to trial the possibility of generating revenue streams from environmental service provision. The Wyre Project was initiated by United Utilities (a water company in North West England), the Environment Agency and The Rivers Trust.

Its aim was to develop a new commercial business model to accelerate landscape and nature recovery which could attract private financing and innovative contracting structures to supplement public funding and address flood risk. The Project has involved The Rivers Trust, The Wyre Rivers Trust, Environment Agency, United Utilities, Triodos Bank UK, Cooperative Insurance and Flood Re.

Over two years, the Project has developed a delivery plan of natural flood management actions over 70 hectares and across six to ten properties. More than 1,000 targeted measures on the farms over three years will act to store floodwater and prevent peak flow. These include leaky dams (placement of woody material in watercourses), earth bunds (small embankments), ponds, tree planting, kested hedgerows (planting hedgerows on small embankments) and the rewetting of peat. Some of these actions are being delivered and maintained by farmers and some by The Rivers Trust.

The costs involved in the Project are estimated to be £1.5 million of capital expenditure, and £50,000 a year in running costs.

In order to cover the costs and pay the farmers for the interventions and maintenance, the Project identified beneficiaries of the interventions and approached them to see if they would be prepared to pay for those benefits. These beneficiaries include the insurance sector, utilities, developers, the local authority and the Environment Agency.

“the Project identified beneficiaries of the interventions and approached them to see if they would be prepared to pay for those benefits.”

While flood risk reduction is the primary ecosystem service in this scheme, the Project is also delivering carbon sequestration as a result of woodland planting; water quality improvements from reduced nutrient run-off; and biodiversity gain from the planting of hay meadows and grasslands. These will attract different buyers to those of natural flood management such as businesses and third sector organisations.

In order to assure buyers of natural flood management of the efficacy of the flood interventions, hydrological modelling has been applied. For buyers of carbon sequestration, the Project is verifying credits through the Woodland Carbon Code, for nutrient reduction it is using a tool called ‘Replenish’, and for biodiversity net gain, Defra’s biodiversity net gain metric.

Given the number of stakeholders and complexity of contracts, the project established a not-for-profit Special Purpose Vehicle (a type of legal entity). Known as the Wyre Catchment Community Interest Company, it will be the legal entity through which capital will flow. It will hold the financial risk.

The Wyre Catchment Community Interest Company has attracted £850,000 of private investment to go alongside a £526,000 grant from the Woodland Trust’s Grow Back Greener programme (supported by HM Government’s Nature for Climate Fund for England). The money has been raised in the form of a nine-year loan. There was one loan agreement for the institutional investors and one loan agreement for those investing through a mechanism called Social Investment Tax Relief. The interest rate is 6% on both loan facilities. The institutional investor loan interest rate reduces to 5% if additional biodiversity targets are achieved.

Assynt Foundation

The Assynt Foundation is a community-owned charity that is selling peatland carbon credits from its land in the Highlands. This is part of a broader strategy to generate revenues that will facilitate further investment in natural capital assets and pay for regeneration and community investment.

Summary of the key steps from the Checklist.

- Natural capital assessment: The evidence base has been generated primarily through the Coigach & Assynt Living Landscape Programme. This included a High-Value Habitat survey in 2020, a joint venture between Scottish Wildlife Trust, the Assynt Foundation and NatureScot.

- Identifying what can be sold: a peatland restoration feasibility was commissioned a study to identify, assess, and map areas of potential peatland restoration. As part of this, potential restoration work was costed.

- Identifying potential buyers: these are expected to be commercial buyers of carbon credits.

- Valuing new finance: to be explored once initial carbon credits have been sold.

The Assynt Foundation was formed in 2025 following the purchase of two adjoining sporting estates in the Northwest Highlands. One of the Foundation’s core objectives is ecological restoration of nearly 18,000 hectares which it has been carrying out over the last 16 years.

More recently, the Foundation began to take a broader natural capital approach. In particular it sought opportunities to fund environmental restoration through the sale of ecosystem services. Peatland restoration was identified as an opportunity given the amount of eroding peatland on the land.

NatureScot supported the Foundation by carrying out a peatland restoration feasibility study. As a result, a programme of projects was identified that will together restore hundreds of hectares of peatland.

Grants through Peatland Action (a Scottish Government grant funding programme) have provided 90% of the costs of the capital works required on the peatland. While the work requires specialist contractors, there are a growing number of such organisations in the Highlands as a result of increased uptake in peatland restoration schemes. Typically, these contractors require monthly payments as they are small businesses.

There is also a recognition that carbon credits are an important revenue source. The Foundation is now working with Forest Carbon Ltd. (a developer of projects delivering woodland and peatland carbon credits) as it goes through the verification process that will enable the Foundation to generate and sell peatland carbon credits through the Peatland Code.

If successful, and depending on price terms, the Foundation will be able to generate significant and transformative income for this community owned charity from the credits.

The revenue from the first sale is expected to go back into funding more peatland restoration projects but also other work such as native woodland restoration and improvements to specific flora as well as being allocated to other charitable objectives. Some future credits generated may be retained in order to create a reserve future income for the Foundation by selling them at a later date.

The Foundation has also considered other means of generating revenues, such as through renewable energy. However, designation of one of the two sites as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (including the provision of habitat for species such as golden eagles), together with the remote location, has led to this being ruled out as an option. Environmentally-based tourism, however, offers an opportunity. In particular, greater numbers of visitors attracted to the area because of the opportunity to walk the ‘North Coast 500’ long-distance path. The only other key revenue generated from the land is from deer management.

Highlands Rewilding

This initiative exemplifies how private investment in the restoration of Scottish rural land has the potential to support greater prosperity for rural communities, as well as delivering on national objectives for the restoration of nature and the achievement of net zero.

Highlands Rewilding involves three estates:

- The 511 hectare Bunloit Estate, a former private shooting estate near Loch Ness.

- The 360 hectare Beldorney Estate in Aberdeenshire.

- The 1,400 hectare Tayvallich estate on the coast in Argyll.

The developer of Highlands Rewilding is green entrepreneur Jeremy Leggett. He made the land purchases. Highlands Rewilding now owns nearly all of the land at Beldorney and two thirds of the land at Bunloit.

Summary of the key steps from the Checklist.

- Natural capital assessment: Highlands Rewilding has placed emphasis on collecting the data to represent the baseline condition of carbon and nature at both estates.

- Identifying what can be sold: revenue will be generated through the sale of carbon and biodiversity credits, as well as ecotourism. There is also the expectation of providing consultancy services to other land managers.

- Identifying potential buyers: these are expected to be commercial buyers of carbon and biodiversity credits. There is, however, no intention of selling any carbon or biodiversity credits for five years.

- Valuing new finance: Highlands Rewilding has so far raised over £10 million of equity investment from over 50 individual investors. These include high net worth investors, family offices and one mutual fund. It is also attracting crowdfunding investment from individuals and retail investors.

Since purchase of the estates, Highlands Rewilding has deployed staff and other resources on the collection of detailed data representing the carbon and biodiversity status of the land. This includes the collection of field data, as well as the use of satellite and drone survey data. eDNA technology has been used to assess the flora and fauna present. A first calculation of the carbon dioxide equivalent stored within the natural features of the Bunloit Estate was made in 2021. This was equivalent of 2% of Scotland’s current yearly emissions.

Highlands Rewilding has undertaken a significant programme of work with local communities in and around the estates, in order to ensure that the restoration work delivers lasting benefits for them. The objective is to provide employment opportunities and places to live that revive the rural economy in and around these estates.

With the addition of more investors, it is expected that Highlands Rewilding to provide a model for the regeneration of land in other parts of Scotland through private finance.

Trees for Life

Carbon credits and environmentally-focused tourism enabled Trees for Life to receive a loan from Triodos Bank for its land regeneration ambitions. This case study illustrates how a charitable landowner can attract finance from a mix of sources, providing benefits to a local community.

Summary of the key steps from the Checklist.

- Natural capital assessment: Over the last 12 years, Trees for Life has developed a broad understanding of the ecological value of the land under its care.

- Identifying what can be sold: After considering a range of services that could be sold, the initial focus was identified as carbon credits generated through woodland planting.

- Identifying potential buyers: Trees for life has considered carefully the likely buyers of carbon credits registered through the Woodland Carbon Code.

- Valuing new finance: Trees for Life undertook a scoping study to gauge what realistic levels of income and profitability could be in order to define the budget.

Trees for Life is a small charity in the highlands of Scotland focused on rewilding (📖) (including tree planting) and community support and development. While Trees for Life is a charity, it offers several examples of how revenues can be generated - and finance attracted - for nature-positive land use change. It also exemplifies first-mover advantage.

Trees for Life acquired 4,000 hectares of land at Dundreggan in 2009. This site is situated near Loch Ness in Glen Moriston. In its early years, the charity struggled to reach the running costs of the tree nursery, volunteering program, centre and land management. Native trees for planting cost from £0.35p to £0.80p per tree, depending on species and sapling height. Rarer species were in the region of £1.50. Planting costs using hand mounding vary from location to location but tend to be around £0.85 per tree.

Various revenue streams were considered by Trees for Life to pay for the costs including running a caravan park and the introduction of hydro or wind energy.

The charity then explored the sale of carbon credits and now uses the Woodland Carbon Code for selling carbon sequestered at Dundreggan through natural regeneration. A high carbon price of more than £30 (Pending Issuance Unit price) has been achieved because of the broader outcomes of rewilding, biodiversity and restoration of land. The charity’s intention is to transfer £10 per tonne from each sale to local community organisations to spend on projects that relate to the land and nature.

Now Trees for Life is developing a new rewilding centre at the site to generate revenues that will rely on visitors and tourism. The charity is well-placed to attract visitors. Dundreggan, for example, is on the main road from Inverness to the Isle of Skye, and Trees for Life has many followers attracted to its nature-related ambitions.

The centre is a £6 million project and Trees for Life undertook a scoping study to gauge what realistic levels of income and profitability could be in order to define the budget.

A consultancy firm was engaged that used an algorithm to determine which paid-for experiences and accommodations could be included to attract the required level of visitors to be able to project suitable incomes. Based on the study, the size of the project was increased by £2 million. Costs have been further inflated by the combined effects of Brexit and the Covid-19 Pandemic on materials prices, leaving a significant gap to bridge.

To pay for the project, traditional grant funding was available for some charitable activities at the centre, and 10% of the funding has been from Trees for Life’s own money from its carbon credit activities. The major source of funding however is via Triodos’ crowdfunding platform as a loan with a 10-year pay-back period. The crowdfunding was launched with a £2 million target on the 13th September 2021 and closed less than 48 hours later with the target achieved and an average investment of £4,800.

Early involvement in carbon credits has also enabled the charity to develop a small for-profit carbon credit advisory business using the skills it has gained in its own journey to advise landowners in the Highlands who are wishing to transform their land.

The Shieling Project

This case study shows the potential for the restoration of leasehold land to be supported by revenues generated from educational events and environmentally-based tourism. Public sector grants, a repayable loan and private income have enabled a business to grow and provide local employment opportunities.

The Shieling Project is a social enterprise founded by Sam Harrison. It involves the lease of four hectares of land in Inverness-shire. With grants and a loan from Social Investment Scotland (a charity offering support to social enterprises), the Project has been able to restore the abandoned house and buildings, restore natural habitat, introduce restorative agricultural practices and create an outdoor learning centre with a business model that generates revenues from educational courses and tourism.

The Project is now exploring alternative revenue generation models such as carbon credits, new courses (such as butchery) and restorative agriculture advisory services.

The Shieling Project began leasing the land in 2015. Deer were excluded from the four hectares that were abandoned in 1968. This allowed natural regeneration of woodland to occur and the planting of over 4,000 trees.

The loan from Social Investment Scotland was used for restoration of the buildings and the introduction of a herd of Shetland cattle. The cattle help restore the condition of the land through rotational grazing. They also produce beef supplied to visitors and manure for crops. Grants from the SSE Highland Sustainable Development Fund, Highland LEADER and others have further supported the restoration of hay fields and traditional cereal crops that support the cattle and pigs, and basket willow is grown next to a stream on the land that is then cropped for crafting.

The Project works with local authorities and schools, and students, tourists and families pay to visit and stay on the land, learning traditional farming methods by doing and crafting, but also playing a role in building and restoring the eco-friendly barns and accommodation. The land supports 36 overnight guests and is entirely self-sufficient using a biomass boiler and solar panels for energy.

The restorative and traditional farming methods have improved the biodiversity on the land. For instance, yellowhammers (Emberiza citrinella) have returned. In addition, due to the labour-intensive nature of the work, the project has created jobs for the community. Prior to the Covid-19 Pandemic, the four hectares provided work for 14 employees. The intention is to return this to 12 employees by the end of 2022.

Over the last five years, the Project has doubled revenue each year. There are up to 800 visitors per year. Before the Covid-19 Pandemic, the project received £120,000 in net income. The aim is to double this.

A challenge has been finding investment that will pay for capital expenditure. Most grants prefer to pay for salaries or specific projects which don’t create sustainable long-term revenue generation. To supplement revenues from visitors, the aim is to sell ecosystem services such as carbon credits. This will be dependent on cost of assessment but also demonstrating former baselines of carbon and additionality. Sam Harrison is being approached by other land managers to learn about the role of grazing animals in rewilding that could develop into an advisory business in the future.

A view of the land within the Shieling project, looking across a valley of woodland and open moorland. credit The Sheiling Project.

Lochrosque Estate

This case study shows the opportunity of peatland restoration to deliver carbon revenue and a wide range of additional benefits.

Summary from the Checklist.

- Natural capital assessment: The condition of the peatland was assessed using the Peatland Code Protocol.

- Identifying what can be sold: The peatland was in deteriorating condition. Its restoration with the aid of grant funding provided an opportunity to sell peatland carbon code credits to reflect the reduction in emissions which would be achieved by a successful restoration programme.

- Identifying potential buyers: the opportunity was promoted through the Peatland Carbon Code Registry and directly to potential purchasers via a new company, Caledonian Climate Ltd

- Valuing new finance: Other than grant funding external sources of finance were not explored for this work. Had they been explored it is believed the project would have been judged on conventional commercial lending terms, including the availability of security.

Lochrosque Estate’s peatland restoration programme in the west Highlands covers an area of 251 hectares. In addition to biodiversity and social benefits, the project has reduced carbon emissions and the Estate is selling peatland carbon credits through the Peatland Code.

As with many Highlands estates, Lochrosque has significant areas of peatland, some of which has been degraded from decades of erosion and over-grazing. This has left deep exposed peat bogs with poor biodiversity and increasing soil erosion.

In accordance with the land management objectives of the wider estate, Lochrosque embarked on a multi-year peatland restoration programme in 2018, funded through the Scottish government Peatland Action Programme and supported by in-kind contributions from the landowner. The main area of restoration lies above the village of Achnasheen on the A832 in Ross-shire.

The programme has required the creation of more than 8,000 timber and peat dams. A total of 251 hectares have been restored to date. With 158,246 metres of reprofiling work, erosion of peat banks on the site caused by wind, rain and heat has been halted and allowed vegetation to regenerate, and although only part of the way through the ten year restoration, other biodiversity benefits have already occurred. For example, raising the water table through restoration has allowed sphagnum moss to continue its bog-building work, and bog pools are now teeming with life. Greenshank and golden plover have also returned (chick mortality has reduced due to restoration efforts).

With regards to the climate mitigation (📖) benefit, the peatland restoration has provided 87,103 tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in emissions avoidance over 100 years. This equates to 3.47 tCO2e per hectare per year. All of this emissions reduction is attributable to the restoration as peatland would otherwise continue to emit greenhouse gases for the next 100 years. This has been estimated to be the equivalent of 1,528 hectares of forestry cover. Carbon credits are now being offered to offsite purchasers through the Peatland Code. The current listing can be found here. One buyer is a producer of cycle safety gear that wishes to become carbon neutral.

The following additional benefits have arisen from the project:

- Employment for specialist peat restoration contractors including training and skills development opportunities;

- Improved water flow to a hydro-generation plant has increased electrical output and reduced maintenance requirements because intake screens do not need to be cleared of eroding peat deposits as frequently;

- Improved water flow and quality to in intake of Scottish Water used for the production of drinking water.

Caledonian Climate and others are now establishing the data to underpin the sale of the hydrological benefits of the scheme.

Explanations

Green finance and nature finance

Green finance means any method of financing or investment activity where money is put to work to ensure an improved environmental outcome. Government and business commitments to reach net zero, alongside greater collective awareness about the importance of environmental protection and restoration, has led to the growth of green finance in recent years. It encompasses financial products such as:

- commercial loans

- community municipal bonds or investments (📖)

- environmental impact bonds (📖)

- corporate or sovereign bonds

- project finance

- public equity (stocks and shares)

- investment funds

- pension funds

- direct investments by companies

- private equity (📖) and venture capital (📖)

- mortgages

- credit trading

- savings products

- crowdfunding (📖)

- philanthropic capital and grants, and

- public sector finance

Green finance can result in a range of environmental outcomes. This covers:

- Climate mitigation (📖), such as through improved energy efficiency and reduced greenhouse gas emissions through technologies such as wind power and heat pumps for buildings.

- Climate adaptation (📖) , such as in reducing flood risk through built or natural structures.

- Sustainable agricultural practices and the restoration of biodiversity.

Nature-based finance is gaining recognition as an important aspect of green finance. This term describes finance or investment that directly goes into the protection and restoration of natural features such as waterbodies, woodland and peatland. Typically, finance for the protection and restoration of natural features has come from the public sector or philanthropy. For example, in 2020, the Scottish Government announced £250 million of funding over ten years for peatland restoration, with a target of restoring 250,000 hectares of degraded peatland by 2030. In recent years, biodiversity loss, coupled with increased recognition of nature’s role in climate mitigation and adaptation, has shone a light on the need to attract private finance. Analysis of the difference between available finance and funding requirements provides the context for this1. For instance, the shortfall for protecting and restoring biodiversity in Scotland over the next ten years has been estimated to be in the region of £8 billion. Similarly, the requirement for climate mitigation using the natural environment (such as in flood risk reduction) over the coming decade is thought to be in the region of £9 billion.

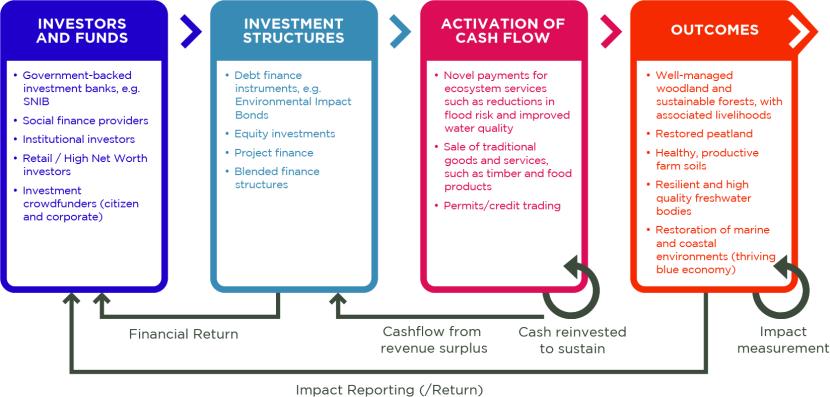

Unlike public finance or grants, private finance requires a financial return. Markets for environmental services are the basis for the flow of private finance into the natural environment. They connect the buyers of services arising from land, water and nature with those who can supply those services. These markets involve financial transactions that are sometimes referred to as payments for ecosystem services (📖). As shown in the following figure, a wide range of investors, investment funds and investment structures may be involved in nature finance.

1 GFI, eftec, Rayment Consulting, 2021, The Finance Gap for UK Nat

Nature finance framework

This diagram shows the key relationship between the various components of nature-based finance. It is arranged in the following four components:

Adapted from a diagram in Conservation Finance. From Niche to Mainstream (Credit Suisse 2016).

Investors and investment funds

Government, philanthropists, institutional investors, retail and High Net Worth investors, investment crowdfunding (citizens and corporates)

Investment structures

- Debt finance instruments, e.g. environmental impact bonds

- Equity investments

- Project finance

- Blended finance structures

Activation of cash flow

- Sales from traditional enterprise activities (tourism, timber, food products)

- Markets for previously untraded ecosystem services (carbon credits, flood risk reduction, biodiversity)

- Compensation fees

- Permit / credit trading

Outcomes

- Well-managed woodland and sustainable forests, with associated livelihoods

- Restored peatland

- Healthy, productive farm soils

- Resilient and high quality freshwater bodies

- Restoration of marine and coastal environments (thriving blue economy)

The availability of private finance may be conditional on social or environmental outcomes. Reliable measurement and verification of these outcomes will be important to investors. While the UK Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code now have widespread recognition as industry standards for the purchase of carbon credits, the requirements of investors for the data to provide them with the assurance that investments in natural features are delivering the desired outcomes are expected to become clearer in future years.

In some cases, private, philanthropic and public finance may be designed to work together in order to achieve better outcomes than if these sources of finance were kept separate. This is known as blended finance, and is yet to be secured for Scotland. Public finance may have a role in reducing the risk of early investments, or guaranteeing a minimum price for ecosystem services such as carbon credits.

Example: A water company is facing increased costs of dealing with polluted water. Rather than building an expensive water treatment plant, the water company can pay for farmers upstream to plant cover crops and reduce nitrate leaching, thereby reducing pollution. In this case the water company is the buyer (and investor) of ecosystem services and the farmer is the seller. (See the explanation of nutrient trading in the Glossary.)

The revenue stream generated can, in turn, attract loans or investments that can pay for upfront capital expenditure.

Example: A landowner can introduce several natural flood management (📖) interventions that will reduce flooding in a local town and therefore reduce costs for public bodies responsible for managing flood risk, as well as those involved in reinsurance for flood risk. The local authority may offer to pay the landowner a price for the maintenance of interventions, but the landowner needs the upfront funding to pay for the capital expenditure. Under this hypothetical scenario, a bank could provide a loan to the landowner with the understanding that the revenue generated from the local authority payments will enable the landowner to make the repayments. See also the Wyre Natural Flood Management Case Study.

Potential income opportunities for Scottish land managers

Nature finance provides opportunities to Scottish land managers to receive incomes through identifying buyers for continuing environmentally-sound practices, improved sustainable land management practices or larger nature-positive land use change. The following table provides examples of the relationship between natural capital (📖) assets, the ecosystem services (📖) they provide and potential buyers. In some cases, service provision may require environmental improvements or a change in land use practices. In the case of the provision of crops, livestock and timber, it may be possible to attract a premium price if they make a particular contribution to environmental restoration.

| Agricultural land | Forests & woodland | Peatland | Ecosystem service | Potential Buyer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

● |

- |

- |

Crops, livestock, educational opportunity |

Consumers, agribusiness |

|

● |

● |

● |

Emissions avoidance and possible carbon removal credits |

Business seeking carbon credits |

|

● |

- |

- |

Carbon emission avoidance (credits) |

Business seeking carbon offsets, businesses via corporate responsibility funding |

|

● |

● |

● |

Surface water retention (flood risk reduction) |

Local businesses, local government, operators of transport infrastructure, insurers |

|

● |

● |

● |

Water quality improvement, including nutrient reduction |

Water companies, housing providers |

|

● |

● |

● |

Opportunity for education, tourism and recreation |

Visitors, local government, companies including local tourism business collaborations, and educational establishments |

|

● |

● |

- |

Timber, including through agroforestry |

Consumer goods companies, construction sector |

|

● |

● |

● |

Biodiversity |

Wildlife charities, businesses via corporate responsibility funding |

The Case studies provided within this guidance demonstrate how land managers are reacting to these opportunities and how they are developing projects.

Financing ecosystem service provision

The following is an explanation of the ecosystem services that are likely to be the basis for new markets, or the basis for the purchase of land based on its natural capital value (potential to provide ecosystem services).

Crops and livestock

- Changes to sustainable, restorative or regenerative farming methods can command a higher price from buyers who are keen to see environmentally positive activities within their supply chains, or from consumers who are willing pay more for products that support habitat restoration.

Carbon credits (storage credits and avoidance credits)

- A carbon credit represents either the permanent removal of a tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) from the atmosphere, or the avoidance of one tonne of CO2e being emitted in the first place. An example of natural emissions avoidance is the restoration of peatlands, which release large volumes of greenhouse gases when they are in a degraded state. The price of carbon varies greatly depending on the quality and narrative of a project and on the buyer. The carbon credit market will also have price fluctuations as with other markets. Quality assurance standards such as Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code, and associated registers, provide transparency and a level of assurance and verification to buyers of carbon credits. They provide a means to match buyers with projects. Care is needed when judging the potential costs, benefits, timings and risks of carbon transactions.

Natural flood management

- Natural flood management such as use of woody debris and damming of water courses to slow the flow of water (including through the introduction of beavers), or re-meandering water courses or woodland or crop planting can alleviate flood and therefore reduce costs of flood damage in surrounding areas. See the Wyre Natural Flood Management case study.

Water quality improvement

-

Interventions such as cover crops and the reduction of nutrient use can improve local water quality for which utilities may be prepared to pay.

Tourism and opportunities for education and recreation

- Land can be used to provide education or recreation opportunities for paying visitors. In conjunction with environmentally positive interventions such as rewilding or restorative farming methods, this land use change can have both a social and environmental impact. The Shieling Project case study is one example. Tourism businesses based on the qualities of the Scottish landscape may look for ways to invest to create positive impact for nature, including using voluntary visitor payback (📖) schemes. Organisations seeking supporting the growth of tourism may look to invest in the restoration of nature based on the enhanced business opportunities.

Timber

- As with food crops and livestock, timber produced in accordance with best practice, and the use of continuous cover forestry, can attract a higher price that traditional timber. The timber industry and retailers of products that use wood are expected to be under increasing pressure to ensure that their supply chains are associated with positive environmental and social outcomes. This may incentivise the creation of woodland planned and managed for multiple benefits, where biodiversity and recreation are balanced with the production of timber and the associated long-term removal of carbon from the atmosphere. Agro-forestry will also play a part in meeting demand for some aspects of local timber markets.

Biodiversity

- Rewilding (📖) and regenerative farming projects that increase biodiversity can attract payments for ecosystem services from wildlife charities or businesses through their corporate responsibility commitments. The achievement of positive outcomes for biodiversity through built development is under consideration as part of the development of the National Planning Framework for Scotland.

Stacking and bundling

In some cases, several different ecosystem services can be sold at the same time. For example, with appropriate design and management, planting woodland on a property or improving soil health may provide carbon sequestration, water retention and water quality improvements. This is known as bundling (📖) . Projects that are designed in way that provides additional benefits like biodiversity may attract a higher price for carbon credits. In other cases, a land owner may sell a set of ecosystem services from the same parcel of land, but each is sold separately. This is known as stacking (📖) .

The role of aggregation

Large investors such as institutional investors often seek investment opportunities that are relatively large in size and scale. This is because it is not an efficient use of resources to deploy teams to assess small projects. They typically need to put between £20 million up to in excess of £500 million to work. As such, they are difficult to attract unless several large landowners work together on a large-scale project.

There are, however, smaller investors or buyers that will look for projects that require between £1 million and £20 million in investment. Collaboration between farmers or communities across a catchment or landscape can help aggregate multiple smaller projects into a large-scale programme. This is the basis for the Landscape Enterprise Networks scheme, in which groups of businesses determine their dependencies – through value chains – on land, water and nature in a particular geographical area. They then collaborate to procure relevant ecosystem services from land managers in the area, ensuring this is done in an equitable, transparent and locally-accountable way. A Landscape Enterprise Networks scheme is currently being developed in South West Scotland.

Landscape Enterprise Networks (adapted from the Landscape Enterprise Networks website).

- Step 1 - Network opportunity analysis

A process for understanding which businesses in a region have most at stake in a healthy and resilient landscape, which natural capital assets in a landscape underpin that performance, and where there are common interests among businesses in the same assets. The objective here is not to develop a comprehensive understanding, but rather to identify the most promising starting point for a Landscape Enterprise Network.

- Step 2 – Building a collaborative value chain

This step focuses on building a first ‘anchor’ value chain, working with those representing ‘demand side’ interests to define a common specification for services they require. Land managers who represent the ‘supply side’ are then enabled to define their service proposition. A deal is then brokered between buyers and sellers, often through an intermediary (known as a ‘supply aggregator’).

- Step 3 - Growing and formalising the regional network

Once Step 2 has generated momentum and interest, the ‘anchor’ value chain can be extended by attracting more customers and suppliers. Additional value chains can be identified. A governance structure is then created within the geographical area to manage and broker trades in an equitable, transparent, and locally-accountable manner.

The potential for project aggregation should not, however, preclude the opportunity of much smaller-scale projects founded on a close relationship between land managers and the rural communities that they belong to. In particular, this can ensure that projects are developed in partnership and that benefits (such as through employment) are retained locally. The scope to formulate and sustain commercial arrangements within the farming sector and other rural businesses should also be considered

Detailed prompts for the consideration of nature finance

A simple Checklist within this guidance provides an overview of the key considerations regarding nature-based finance opportunities. The following provides a more detailed set of prompts for land managers in their consideration of how it might relate to their organisation.

The land I look after

- How is the land I am responsible for used at present?

- Is the environmental condition of this land improving or declining, and how do I make this judgement?

- Who is benefiting from the current condition of the land?

- In principle, what environmental outcomes could I deliver more of in the future?

- Who would potentially pay for these environmental outcomes?

My business at present

- What are my long-term objectives?

- Who will determine any changes to my business? Are they amenable to delivering more environmental outcomes?

- Who are the buyers of environmental outcomes who have an interest in the land I am responsible for?

Scoping new plans

- What impact would the delivery of more environmental outcomes have on my business as a whole?

- Do I need a new business plan, or does the existing one suffice?

- Could I work with others, including managers of neighbouring land, in order to increase the scale?

- How might I work with rural communities on and around the land I look after?

- What permissions or changes to existing agreements would be required?

- How might I demonstrate the environmental outcomes of a new project? How much would this cost?

Making new plans

- What skills and experience are needed to make new plans? How much will this cost?

- Who is going to pay for which environmental outcome? What income can I generate?

- What are the implications for my existing business?

- What data, standards and metrics will be required in order for new agreements to be made? How much will these cost?

- Who should I present my new plans to?

- What upfront capital may be required, and how much would this cost?

- What are the implications for taxation and capital value?

Develop contracts

- Who is the contract with?

- How long is the contract for?

- What is the payments schedule and how is this connected with the measurement and verification of outcomes?

- What is the capacity for variation of the agreement or termination?

- What are the implications for the sale of the land, or the tenancy?

- What are your responsibilities at the end of the agreement?

- What happens if the terms of the contract are breached?

Implications of nature finance for capital value

One of the first considerations for many landowners considering nature-based finance will be the impact of this on the long-term capital value of their land. At present, this is an area of uncertainty due to the absence of case history.

Participation in nature finance initiatives may have a positive or negative impact on land value (or no impact at all).

- Shorter-term (up to five year) commitments with flexible terms for renegotiation or withdrawal are likely to have a smaller impact on the capital value of land in the long term.

- Longer-term (longer than ten years) commitments represent a higher risk for current and future owners and their impact may be discounted accordingly in an asset valuation. This is particularly the case where the changes to land are irreversible (such as with planting of woodland) and/or locked in by contractual commitments. There is no clear evidence on what the amount, if any, of that discount might be. It could also be argued that a generous income with a strong covenant (broadly the financial security of the payer) on appropriate terms should enhance the value of rural assets.

Ideally, payment terms would include provisions for reviews at regular intervals, perhaps also linked to the Consumer Price Index or some other index of inflation. Readily accessible and economical methods of dispute resolution would also be an important consideration in assessing the impact of these terms.

The emergence of a new category of private purchaser of land, based on natural capital is a feature of the market for larger Scottish estates in recent years. In some cases, this involves corporates with interests in the value of land for the provision of carbon sequestration, as well as other Environmental, Social and Governance (sustainability) responsibilities. This is a factor in the volatile market for land. Restoration of land to enhance its natural capital value can be expected to cause increases in land value.

In December 2021 The Scottish Land Commission commissioned research into this area. A report is expected in Spring 2022.

Contractual considerations

Think carefully about contractual considerations before approaching your lawyer and other rural professional consultants for advice. This will enable you to get the most from them at the best price. You may need to seek advice on the practical contractual implications from a rural surveyor or farm business consultant as well as legal and financial advice from your lawyer and accountant. Agreements may take any one or more of a number of forms, for example, a short and simple written contract signed by two parties, a licence or lease to occupy land or even a legal deed.

The following list suggests some considerations and issues which it will be best to think through from the very start of any proposal.

Parties involved

Who will be the parties to the contract and in what capacity can they make a contract between themselves? Typically, this might be a landowner and/or occupier who is selling natural benefits or services from the land, and the purchaser. Be aware that others with an interest in the land may also need to be a party to a contract. Examples include:

- Lenders who hold security over the land

- Holders of leases and beneficiaries of other rights, such as sporting rights

- Owners of mineral rights

Others may need to be consulted and closely involved, included in the main contract, or have separate side contracts of their own. Examples here might be tenants and other occupiers, beneficiaries of trusts and temporary occupiers – graziers, contract or share farmers for example. In some situations, other authorities may also need to be a party to the agreement, for example, a local planning authority where a Planning Obligation (Section 75 Agreement) may apply.

Type of agreement

In addition to the Section 75 agreements mentioned above; other agreements may take the form of a simple agreement while some may need to be created by deed. Some agreements may take the form of a lease or licence to occupy the land. Advice on the options and best solution will be needed. A clear understanding of the objective of the agreement, and what is trying to be achieved, will be essential to determine the best type of agreement.

The land and property

This will need to be defined preferably with the use of a descriptive schedule and a well-drawn plan at a useful and recognisable scale. Specific sites may need to be identified within a larger landholding, and the plan may need to show additional features such as access routes, vehicle parking and servicing areas, storage areas, planned boundaries and other features depending on the agreement. Early thought is needed to specify the type of plan(s) required to make sure they will be ready in time, including the need for more detailed larger-scale insets.

Services to be provided

The services to be provided should be defined as precisely and carefully as possible. Most land managers will want to define the services to be provided as narrowly as possible to leave scope for the negotiation of new opportunities in future for example carbon sequestration in timber. It can therefore be helpful to say what is not included as well as what is included provided this does not unwittingly exclude other possibilities which have not been foreseen yet. Many further considerations will flow once the services have been defined.

Access arrangements

It is important to consider what site access the parties need. Considerations include: the type of vehicles allowed on-site, where they can be parked (and for how long), whether notice is needed before entering the site, what the maximum size of visiting parties is, and whether there should be permitted hours for access with no or emergency-only access outside these hours. There may need to be specification of the arrangements for animals on-site and their welfare. Associated rights, such as those required to install and visit monitoring equipment, will need to be clarified.

Wider publicity including photography

Aspirations for wider publicity? How will these be addressed? Is a policy on photography and filming on site needed?

Risk assessments, health and safety

Land managers will need to determine which risk assessments must be prepared, maintained and shared, and by whom. Key issues and responsibilities for health and safety will need to be determined, including signage.

Security

Consideration will need to be given to site security, including locking of gates, and security ID for personnel on-site. There may need to be signing in (and out) arrangements for sensitive sites. Emergency contact details and arrangements will need to be specified Consideration should be given to the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

Signage

What signs, if any, are required or will be permitted, and how will their design and location be agreed upon? The siting and design of signs may be particularly sensitive in some locations. For example, there may be concerns about the impact of signage on access arrangements under the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

Relationship with and reservations concerning other agreements or schemes affecting the same site

At the very least, the existence of other agreements or schemes should be recorded. Land managers may need to go further by repeating restrictions and obligations which arise from other agreements and schemes in the form of undertakings between the parties.

Use of power and other resources like water

Access to electrical outlets and charging arrangements (if any) will need to be specified. Consideration will need to be given to the use of powered appliances on-site including hand tools like strimmers. Arrangements for fuel and lubricants to be brought on to the site as to types, quantities and storage will also be important.

Waste storage and removal

Consideration needs to be given to waste that might arise on the site, including how will it be collected, kept safe, stored and removed. There may be licensing requirements associated with this.

Duration