NatureScot Research Report 1272 - Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment - project report

Year of publication: 2021

Authors: Hume, A., Gibson, A., Fitton, R. and Mansfield, J. (Finance Earth)

Cite as: Hume, A., Gibson, A., Fitton, R. and Mansfield, J. 2021. Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment – project report. NatureScot Research Report 1272.

Keywords

natural capital; investment; sustainable finance; nature-based solutions; ecosystem services

Background

NatureScot and its partners are exploring approaches to secure more varied and sustained investment in nature through the Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment project (the “Project”). The Project aims to identify business cases, financing mechanisms and supporting tools that can help to unlock significant investment in the natural environment and have the potential to be scaled up and replicated across Scotland.

The objective of this report is to capture the learnings and findings of the Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment project. This report should be used to support further efforts to facilitate investment into Scotland’s Natural Capital.

Main findings

- Scotland’s natural capital assets deliver significant levels of ecosystem services, many of which have the potential to attract private investment to maintain or enhance them.

- To catalyse private investment, natural capital project developers and enterprises should explore the opportunities to generate net positive cashflows.

- A natural capital assessment provides a good basis for identifying opportunities.

- There are a range of financial products and investment vehicles that could be applied in the context of Scotland’s natural environment.

- Financing solutions should be applied based on their suitability to the underlying revenue streams of a given project, as well as the regulatory and market infrastructure in the region.

- Public sector support is required to catalyse the growth of natural capital investment markets. This could take several forms, including investment-readiness funding, compliance regulations and price support mechanisms.

- Natural capital investments should be implemented with transparent and robust governance structures to avoid trade-offs between financial and impact goals, and in order to distribute the benefits widely, such as to local communities.

- The development of a Scotland Carbon Fund could facilitate private investment at scale into Scotland’s peat and woodland landscapes and provide a model for funding other nature-based solutions.

- The development of a Price Floor Guarantee mechanism for carbon projects could help to overcome some of the key barriers to market development and improve the efficiency of public spending.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Facilitating Natural Capital Investment Project Board for their input and guidance throughout the Project and on the preparation of this report.

The learnings and outputs of this report are the result of consultation with a wide range of local stakeholders across the Scottish Borders and industry and environmental experts. The authors would like to give thanks to all those who contributed, including Eftec, RSPB Scotland, International Union for Conservation of Nature UK and Professor Mark Reed, Forest Carbon, Peatland Action, Scottish Borders Council, Buccleuch Estates, Scottish Environment Protection Agency and Go Tweed Valley.

As local partners and hosts to the Project, Tweed Forum has provided a wealth of information and expertise and a uniquely informed perspective on local natural capital priorities and challenges, as well as access to its broad network of stakeholders across the Scottish Borders and beyond. The authors give special thanks to the Tweed Forum team for their ongoing engagement in the Project.

This report was prepared by Finance Earth.

Introduction

“Natural capital” refers to the stock of renewable and non-renewable resources (biodiversity, air, water, soils, minerals) that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people (SEAA, 2020). Scotland is home to a broad range of natural capital assets, including some of the world’s most important peatlands, extensive forests and hundreds of miles of coastline and marine habitat. NatureScot’s Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment Project (“the Project”) seeks to demonstrate practical mechanisms to secure private investment into these assets in order to deliver environmental, social and economic benefits.

The objective of this report is to summarise the process, outputs and learnings of the Project conducted between August 2020 and March 2021. Background section briefly sets out the domestic and international context of the Project and the process carried out by NatureScot and project partners to date. Investment opportunities in the Tweed Catchment section considers the breadth of natural capital investment opportunities identified by the Project team across the selected project area of the Tweed catchment. Assessment of Investment Priorities section captures the summary outputs of our analysis of the natural capital investment opportunities identified. Priority Investment Structure - Scotland Carbon Fund section provides a deep dive into the priority investment structure, a ‘Scotland Carbon Fund’, and includes an analysis of aligned financial structures and market mechanisms to further facilitate investment in parallel with the Scotland Carbon Fund. Financial Analysis section summarises the financial analyses carried out to underpin the market impact of proposed mechanisms and structures. Learnings and recommendations section draws together the learnings of the initiative and identifies key recommendations from the Project to carry forward.

The Project Area Characterisation report, produced by eftec to support the Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment Project, can be found in NatureScot Research Report 1284.

Background

International context

It has been estimated that globally approximately $967 billion of annual investment is required to safeguard the natural environment, but current annual spending is only around $130 billion (Deutz, 2020). There is growing recognition of the importance of the private sector to meet this funding gap, by developing investment opportunities that protect or restore natural capital while generating a return on investment.

Today, the bulk of funding for nature conservation comes from public and philanthropic sources. As of 2019, it was estimated that just c.$20.75bn of private capital flowed to nature positive activity and conservation investments, (Deutz, 2020) although the market is rapidly growing in some parts of the world (Hamrick, 2016). For example, the US restoration industry alone has reached $25 billion in annual economic output, supporting 220,000 jobs, more than the logging, coal mining, iron and steel industries combined (Barrett, 2015).

Scottish context

Within Scotland, there is increasing political interest in natural capital, with recognition of Scotland’s unique landscapes, wildlife and resources for natural capital and renewable energy. With the First Minister’s declaration of a climate emergency in 2019, Scotland aims to reach net zero by 2045, five years before the rest of the UK. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, Scotland is now positioned to showcase its plans for a green recovery at COP 26, with an “unequivocal focus on climate change, fair work, diversity and equality” (Scottish Government, 2020).

The Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment project was commissioned to demonstrate practical ways in which private sources of finance and investment can be facilitated to support nature-based interventions that produce a range of beneficial outcomes – environmental, economic, human and social - that reflect both national and local priorities.

This focus is reflected in the selection of Tweed Forum as local partner and host to the Project. Tweed Forum has provided leadership and expertise to develop a range of nature-based projects spanning the Scottish Borders. While the focus of its work is localised, the learnings are relevant across Scotland.

Literature review

In January 2021, NatureScot published the Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment: Literature Review (Finance Earth, 2021). This review was carried out by Finance Earth to identify key lessons for facilitating investment in natural capital in Scotland, particularly at the regional level, by looking at relevant experience and initiatives from across the world.

The review assessed a series of natural capital financing products and vehicles used in an international context that may be applied to Scotland’s natural capital assets. The review also identified the key barriers to the development of ecosystem service markets in Scotland, including revenue uncertainty, capacity and expertise, consistency of policy and standards and the scale and complexity of projects. The review also considers how these may be overcome. The key recommendations from the review, including for more investment readiness support and pathfinder funding to catalyse new markets, are echoed in this report. The remainder of the Project has built on the foundations of the literature review and these two documents should be considered in tandem.

Facilitating Local natural Capital Investment Project process

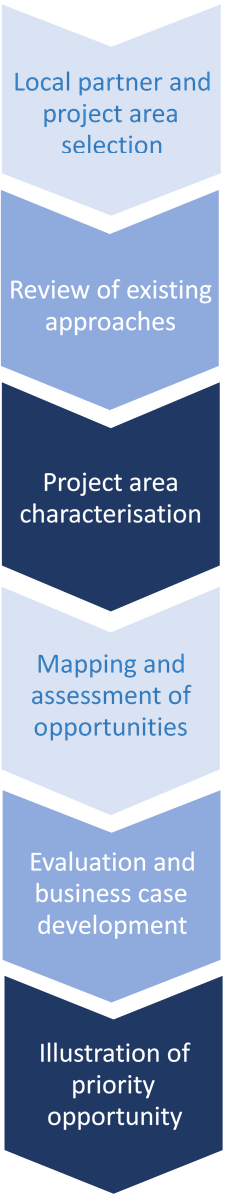

The Project followed a six-stage process to identify and evaluate natural capital investment opportunities across the Tweed catchment.

Full description of the diagram is provided in the text below

Local partner and project area selection

- A short tender process was used to select an experienced local partner with whom to develop the Project.

- From a total of 16 applicants, Tweed Forum was selected to be the Project partner to host the study with a focus on the Tweed catchment within the Scottish Borders.

Review of existing approaches

- The Project team carried out a desktop review of global natural capital investment initiatives to identify project learnings and approaches applicable in a Scottish context.

- The literature review in NatureScot Research Report 1260.

Project area characterisation

- A characterisation of the Project area was developed to review the natural capital assets across the Tweed catchment.

- The area characterisation identifies both existing ecosystem services and the demand and priorities for investment.

- The characterisation report is included in NatureScot Research Report 1284.

Mapping and assessment of opportunities

- With support from Tweed Forum, local stakeholders were engaged to gather evidence on the priorities for investment outlined in the characterisation report.

- Opportunities were assessed at a high level against their capacity to develop and deliver revenue streams to support investment.

Evaluation and business case development

- The suitability of a series of financing mechanisms to the needs of each investment priority was evaluated.

- Opportunities were assessed based on their maturity, scalability & replicability, investment readiness and impact.

- The opportunity for a Scotland Carbon Fund was selected for further analysis.

Illustration of priority opportunity

- Detailed analysis of the opportunity for a Scotland Carbon Fund and aligned financial mechanisms was carried out.

- This included engagement with both local and national stakeholders, financial modelling and scenario analysis.

The following sections of this report capture the learnings and outcomes of each stage of the Project.

Investment opportunities in the Tweed Catchment

Longlist opportunities for investment

Baseline information was gathered on a diverse range of investment opportunities across the Scottish Borders. Priority opportunities have been grouped into eight themes, selected based on activity witnessed across the Tweed catchment and the investment needs highlighted in NatureScot Research Report 1284.

Further investment opportunities may arise overtime as a result of policy and market developments, such as updates to the National Planning Framework and NatureScot’s pilot land management projects testing outcomes-based approaches.

Key opportunity themes assessed include:

- Peatland Restoration

- Woodland Creation

- Nature Friendly Farming

- Riverwoods

- Nature-based Tourism

- Biodiversity offsetting

- Renewable Energy*

*Renewable Energy opportunities were excluded from the scope of our analysis, based on the maturity of the existing market in the Project area. However, further opportunities for Renewable Energy projects may develop over time and planning policy developments could enable significant investment to enhance biodiversity to mitigate against development impact.

Assessment criteria

For each opportunity theme, the business model and financing structure was evaluated against the five criteria in Table 1. This assessment was carried out to identify near term priorities for further analysis, as detailed in Investment Opportunities in the Tweed Catchment section and summarised in Assessment of Investment Opportunities section.

It should be noted that this analysis is specific to the Tweed catchment area only and the suitability of different mechanisms may vary between other regions and at a national level.

Table 1. Assessment criteria

|

Criteria |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Maturity of the underlying market or business model, whether developed within Scotland, or internationally. |

|

Scale of opportunity in Project area |

Scale of the opportunity to raise investment and deliver change across the Tweed catchment. |

|

Replicability across Scotland |

Opportunity to replicate the proposed approach at a national level beyond the Tweed catchment. |

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Capacity to attract investment against the proposed model in the context of Scotland’s regulatory and market environment. |

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

Alignment with Scotland’s social and environmental priorities. |

Peatland restoration

Peatland restoration was identified as a high priority opportunity for further investigation.

Opportunity summary

There is 22,000ha of blanket bog across the Tweed catchment of which just 3% is currently in ‘near natural’ condition (NatureScot Research Report 1284). The establishment of the Peatland Code by the International Union for Conservation for Nature (IUCN) in 2017 presents a repayable finance opportunity for peatland restoration projects by utilising the revenue stream generated through the sale of carbon units to corporates with voluntary carbon offsetting strategies.

Dryhope Farm in the Yarrow valley is home to the first restoration project delivered under the Peatland Code in the UK. Restoration spanning across 77ha was delivered with a blend of carbon credit sales and grant support provided by Peatland Action.

Based on evidence provided by Tweed Forum, Forest Carbon, RSPB Scotland and Peatland Action, there is a growing case for the use of a blend of public and private finance to support peatland restoration.

Unlike available grant funding, carbon-based finance could be used to fund long term habitat maintenance and compensate for the loss of existing revenues on the land. In this way, private finance may be more attractive to landowners and enable larger-scale restoration compared to short term grants.

Key barriers to investment

The following key barriers to investment and scale have been identified:

- Carbon pricing is currently not sufficient to support the majority of restoration activity. Carbon markets are also considered volatile and opaque, driving uncertainty and restricting the ability for landowners to participate individually in the markets.

- Public funding provided through Peatland Action has been intermittent, and time constrained and has not incentivised private investment.

- Understanding of peatland restoration is limited amongst investors, landowners and contractors. Restoration interventions and associated costs are site specific and may require ongoing active management to secure long-term ecological improvement.

- Peatland condition data is not ordinarily available and baselining surveys are required before intervention

- Market uncertainty has driven under-investment in training and equipment by restoration contractors. This is compounded by the seasonality of restoration works due to weather and ecological factors.

Illustrative investment structure

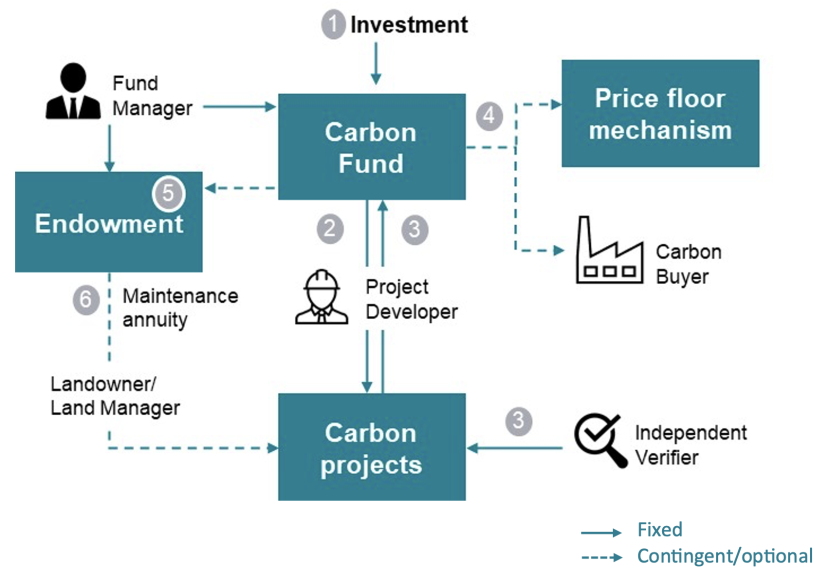

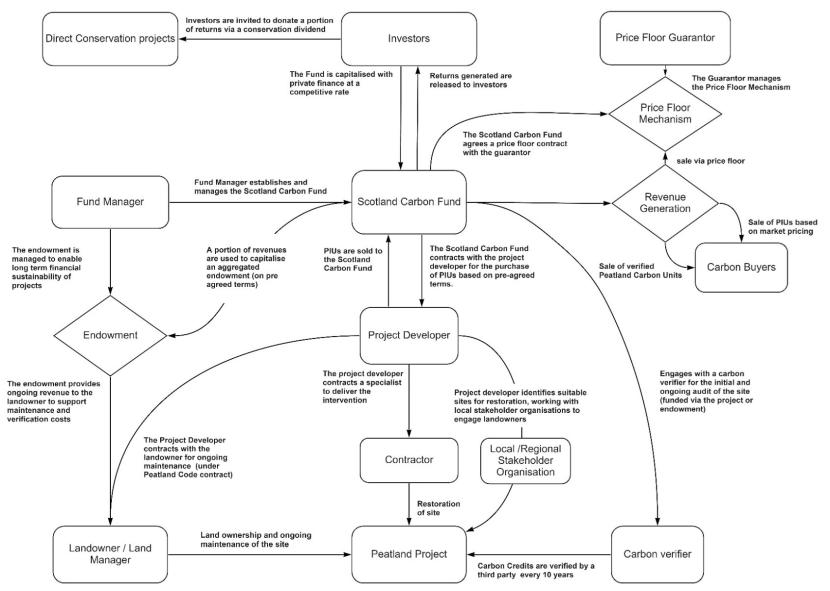

A Scotland Carbon Fund could provide access to private capital at scale to multiple “carbon-sink” landscape types, including woodland and peatland, and other land uses and habitats in future, as standards are developed. The proposed mechanism is designed to work in tandem with a price floor guarantee, explained further in Model structure options section.

A Scotland Carbon Fund could support private investment into the delivery of peatland restoration and allow for landowners to participate in long term carbon market movements as well as receiving upfront income. It would be more effective if it was able to access a carbon price guarantee mechanism provided by the Scottish Government. A pilot fund would aim to raise at least £10 million of private investment.

- Under the proposed structure, repayable investment is raised into the Scotland Carbon Fund by a regulated fund manager.

- The Carbon Fund purchases validated carbon units (Pending Issuance Units, ‘PIUs’) from planned projects prior to restoration activity, thus taking on project delivery risk. These projects are identified through partnership with project developers and networks of local stakeholder organisations such as Tweed Forum, which work closely with landowners to establish new opportunities.

- PIUs are independently verified over time to become Peatland Carbon Units (PCUs).

- Carbon units are sold by the fund either to:

- Private carbon buyers (as either PIUs or PCUs); or

- Through a publicly funded price floor mechanism as PCUs (explored further in Priority Investment Structure: Scotland Carbon Fund section, thereby generating a return to investors in the fund if sales are profitable.

- A portion of profits may be used to capitalise an endowment, providing an ongoing revenue stream to the landowner through a revenue share agreement between the Scotland Carbon Fund and the Landowner to support lifetime management costs or account for foregone revenues.

- Sites are managed over their respective project lifetimes by the landowner/ manager or a third-party operator.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Medium |

|

|

Scale of Opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

High |

|

|

Replicability |

High |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Low |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

High |

|

Recommendations for further development

The Scotland Carbon Fund opportunity was prioritised for further analysis which is detailed below in Priority Investment Structure: Scotland Carbon Fund section.

Woodland Creation

Woodland Creation was identified as a high priority opportunity for further investigation.

Opportunity Summary

A significant opportunity for woodland creation in the Scottish Borders was identified, based on the existing scale of activity.

In partnership with Forest Carbon, Tweed Forum has delivered 16 woodland creation projects, by connecting with and engaging aligned landowners across the region (Forest Carbon Limited, 2021). This includes a significant focus on riparian planting with a recognition of the multiple benefits generated for the catchment.

Projects are funded through a mix of planting grants and the sale of Woodland Carbon Code-validated PIUs to voluntary offtakers.

Approximately 20% of the Scottish Borders is currently wooded, comprising primarily of commercial coniferous plantations in upland areas. There is a significant opportunity to improve the biodiversity of woodlands through the planting of non-timber oriented, mixed native species.

It was reported that carbon payments typically support 25-30% of capital costs of delivery in the current market. Notably, projects with additional environmental and social benefits such as charismatic biodiversity and local community benefits and engagement can attract a carbon price premium, a trend also evident in international voluntary carbon markets.

Key Barriers to Investment

The following key barriers to investment and scale in Scotland have been identified:

- Rising timber prices, paired with growing interest in voluntary carbon markets have increased competition for available land, with forestry land prices more than doubling in 2020 (John Clegg & Co, 2020).

- Land ownership is highly concentrated and complicated by a patchwork of tenant farmers, crofters and longstanding land rights.

- Revenue stacking, which involves selling carbon credits alongside other products from the same land such as agroforestry or water quality credits, can raise additionality complexities. Both the Peatland Code and Woodland Carbon Code require projects to pass additionality tests.

Illustrative Investment Structure

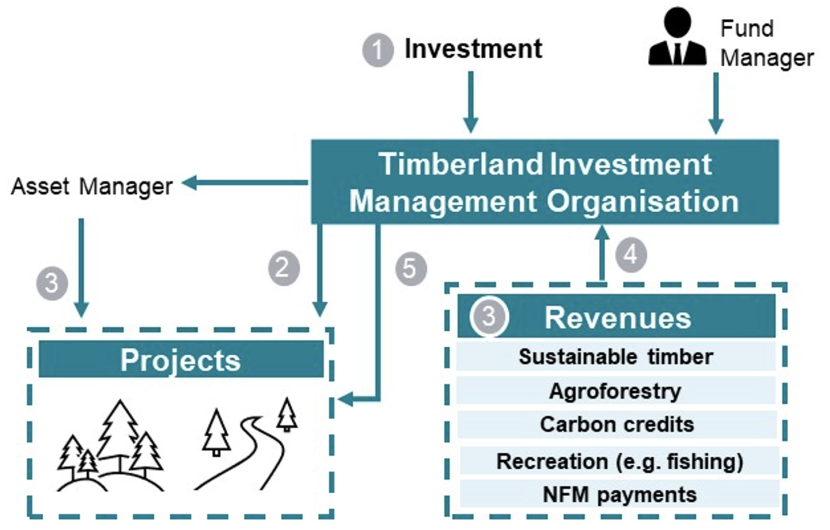

A Timberland Investment Management Organisation (TIMO) is a pooled fund that enables investment in landscapes at scale, generating sustainable revenues to support conservation objectives.

A TIMO can be designed to manage a portion of its assets to generate revenues to support biodiverse woodland planting and conservation initiatives. This could include productive woodland subsidising riparian conservation efforts.

A TIMO could be aligned with or governed by a place-based organisation (such as Tweed Forum) or a community enterprise, ensuring that the vehicle remains accountable and that benefits generated are captured locally.

A TIMO structure could support private investment into the delivery of woodland creation and restoration, through the stacking of a series of revenue streams that could include carbon credits, timber (produced through sustainable practice, as defined by the UK Forestry Standard), Natural Flood Management (NFM) payments and enterprise activities.

A TIMO should aim to raise at least £10 million and ideally more than £25 million to access institutional investment, supported by a project pipeline it could be deployed at a regional or national scale.

- Under the proposed structure, investment is raised into the TIMO.

- The TIMO purchases or leases target land and forestry assets with a mix of identified revenue opportunities.

- The TIMO contracts an Asset Manager to generate a range of conservation outcomes and associated revenues from the assets, which could include the creation of new nature-friendly woodlands.

- Investment returns are generated out of project revenues to repay investors over the life of the TIMO.

- Surplus returns may be reinvested or donated to an aligned community entity as a ‘conservation dividend’ providing indirect social and environmental benefits, and tax efficiencies.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

High |

|

|

Scale of opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

High |

|

|

Replicability |

High |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Medium |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

High |

|

Recommendations for future development

The TIMO structure could facilitate project development, improve environmental outcomes, access to capital and scale for biodiverse woodland creation and management projects. Growth could be driven by the development of the voluntary carbon market, or through enterprise opportunities.

The Scotland Carbon Fund and price floor guarantee opportunities detailed in Priority Investment Structure: Scotland Carbon Fund section may also be applicable to woodland creation projects. However, peatland and woodland carbon markets are distinct and at different phases of development in Scotland. As such further analysis and application of the model to woodland project examples is required to assess this opportunity further.

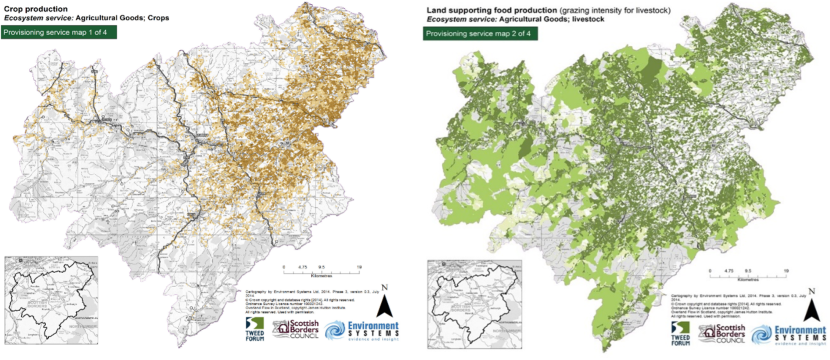

Nature Friendly Farming

Nature friendly farming was identified as a medium-term opportunity.

Opportunity Summary

As key landowners and beneficiaries of ecosystem services across the Tweed catchment, farmers and farming practices are critical to the protection and enhancement of natural capital.

As depicted in Figure 5, more than 75% of land across the Scottish Borders is used for agricultural purposes (NatureScot Research Report 1284). This is comprised of:

- 2,500 farm holdings;

- c.190,000ha of arable farmland and improved grassland concentrated in lowland plains; and

- c.170,000ha of rough grazed land (mostly sheep grazing).

With this scale of land use, sustainable management of farmland has a vital part to play in the management of Scotland’s natural capital. This includes building on the significant ongoing activity led by farmers while also allowing the sharing and development of new practices.

Farming community organisations have a key role to play in setting standards and building shorter and more impactful supply chains. This includes organisations such as Scottish Agricultural Organisation Society (SAOS), National Farmers Union, Scotland (NFUS), Scottish Land and Estates, Local Agricultural Discussion Societies and the Border Union Agricultural Society.

Key Barriers to Investment

The following key barriers to investment and scale have been identified:

- No/Few ‘keystone’ beneficiaries willing to pay for natural capital enhancements have been identified to date. Where key beneficiaries can be identified farmers and landowners may come together to delivered nature-based solutions at an aggregated scale.

- The complexity of existing supply chains may dilute or confuse relationships with retailers and end consumers.

- Complexity of engaging with large group of farming stakeholders and managing varied local priorities.

Lack of market evidence for premiums for products produced under existing agricultural standards.

Illustrative Investment Structure

Sustainable farming and land management practices can be supported through an Agricultural Standard and kitemark scheme. Through this approach, farmers can be encouraged to commit to specified practices where certification can be expected to result in increased sales and/or margins. Farmers may also be able to access new revenue streams through conservation payments or benefit directly from additional revenue streams linked to interventions.

Agricultural Standards and other kitemark models are a potential gateway from intensive land uses to sustainable practice including organic farming. This approach has been used successfully by organisations including LEAF (Linking Environment and Farming), the Soil Association and the Pasture Fed Livestock Association.

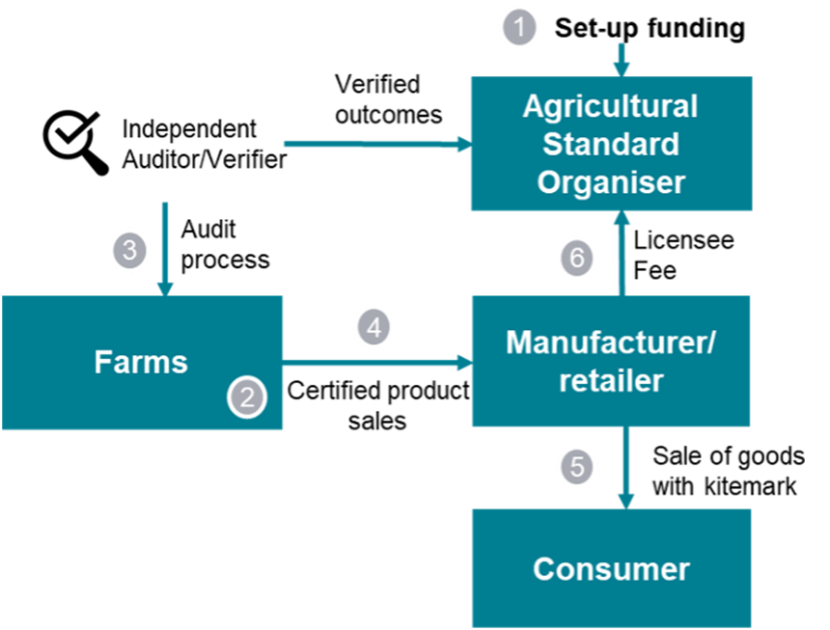

Agricultural Standards

An Agricultural Standard may be piloted at a local scale and grown over time or established at a national level. This may be limited to a single flagship product or designed to support all products from a given region. Revenues are generated through membership fees and/or licensee fees from manufacturers and retailers.

- Under this structure, funding is provided to set up the Agricultural Standard and develop a network of participating farmers, brands/retailers and consumer engagement.

- Participating farms commit to and carry out specific sustainable land management practices e.g., maintaining a portion of land as nature-friendly habitat.

- An independent auditor verifies compliance with the scheme.

- Agricultural products certified under the Agricultural Standard are sold to manufacturers/ retailers.

- Consumer products carrying the Agricultural Standard kitemark are purchased by consumers.

- Manufacturer/retailer pays the Agricultural Standard provider a licensee fee based on percentage of certified product sales revenue.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Medium |

|

|

Scale of opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

High |

|

|

Replicability |

High |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Low |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

High

|

|

Recommendations for future development

Organisations such as Tweed Forum that bring together regional stakeholders are well-placed to lead the development of an Agricultural Standard, working with farmers and other producers to provide positive environmental outcomes. Key recommendations for future development include:

- Identify target environmental benefits and participant activities, working with farmers to create a realistic, attractive and scalable structure.

- Carry out market research on consumer demand for nature-friendly products to identify product opportunities and potential price differentials.

- Carry out market research on suitable products, producers and retailers to engage with a pilot scheme.

- Identify a suitable operator, accreditor and seek funding to develop a pilot programme.

Natural Flood Management (‘NFM’) and Water Environment

Investment in NFM and the Water Environment was identified as a medium-term opportunity in the Scottish Borders.

Further engagement work with key stakeholders and beneficiaries will support development of this opportunity.

Opportunity Summary

Across the Tweed catchment, 8% (4,575) of properties are at risk of flooding (NatureScot Research Report 1284). The attenuation capacity of upland areas has been impacted by processes including peatland erosion, agricultural improvement and monocrop forestry.

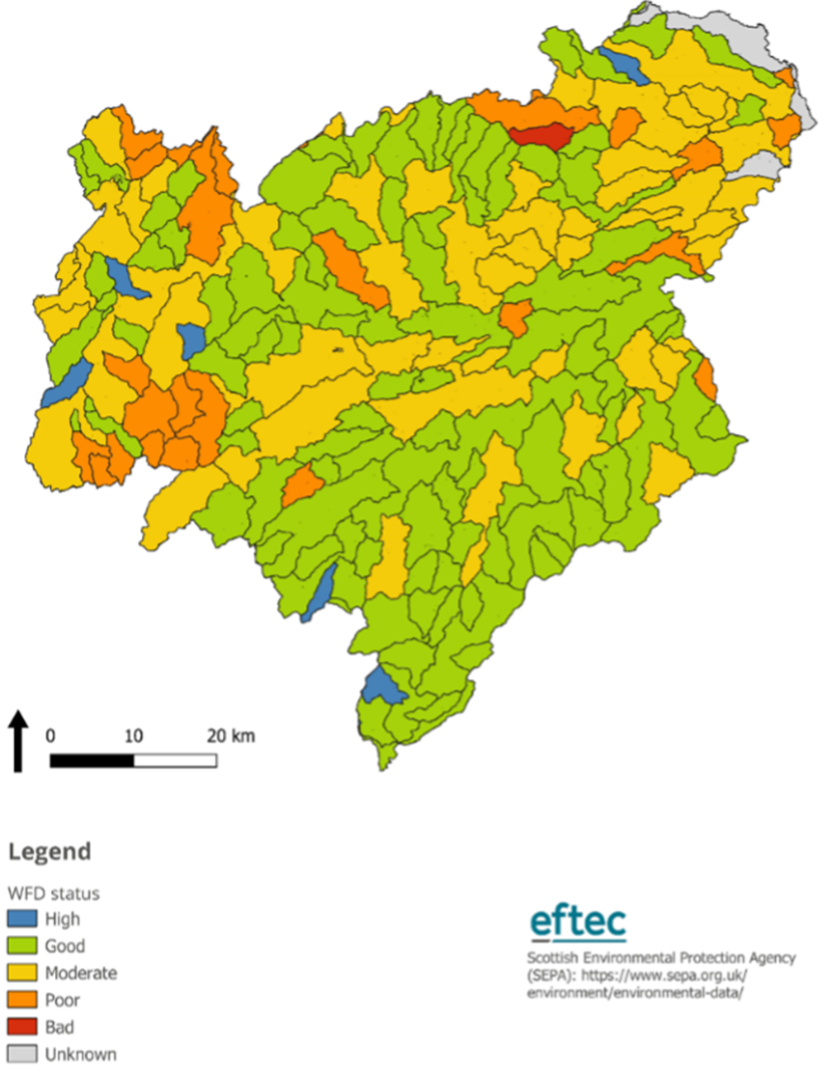

Water bodies are mostly in ‘Good’ condition across the Tweed catchment (SEPA, 2020). However, key pressures arise where there are man-made barriers to fish migration and rural diffuse pollution.

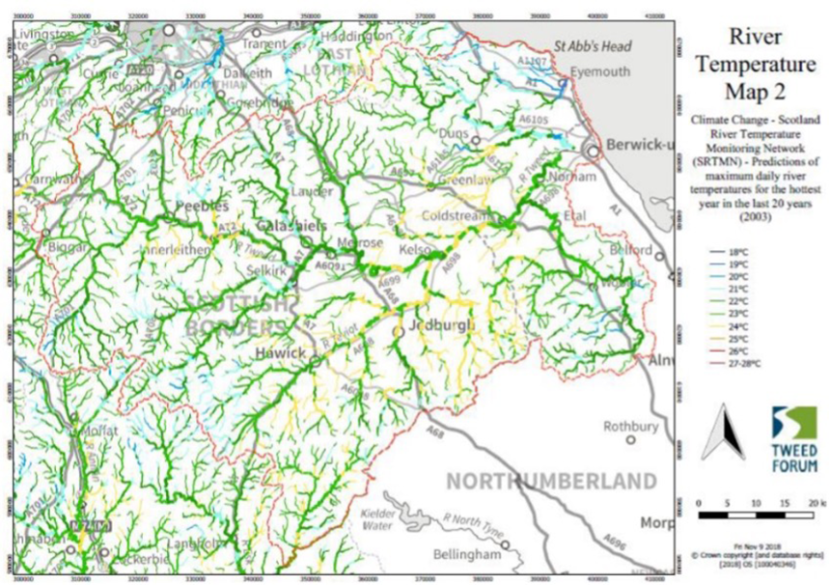

With low native woodland coverage, exposed riparian zones have seen increasing water temperatures and associated falls in fish stocks. This is relevant in a region where sport fishing represents a key driver of tourism. Watercourses are also subjected to other pressures including weirs, invasive non-native species, topsoil and nutrient run-off and dredging.

Tweed Forum has identified the benefits of landscape scale intervention to manage the impact of changing land use on the water environment across the catchment and has led pioneering NFM projects across the catchment, including most recently on the Eddleston Water (Tweed Forum, 2021).

Key Barriers to Investment

One of the key barriers to investment in NFM and water environment interventions in the catchment has been identified as a lack of engagement from beneficiaries. Although the Scottish Borders Council flood protection scheme represents a source of funding, no further beneficiaries willing to pay for or invest in NFM outcomes have been identified to date.

Scottish Water was identified as a key beneficiary of this type of intervention (through water quality improvements), with the headwaters of the Tweed catchment providing water to the City of Edinburgh, but neither the Project nor Tweed Forum has been successful in engaging with Scottish Water to discuss these opportunities further.

Low beneficiary engagement may be ascribed to several key factors. In the first case, water quality across the catchment mostly meets regulatory standards, limiting interest from regulated entities in arrangements to deliver impact. Additionally, nature-based solutions for NFM and water environment (e.g., water quality) have a limited track record compared to traditional hard engineered solutions. This creates a barrier for water utilities aiming to ensure that customer funds are used to deliver proven and reliable outcomes. This is compounded by the need for attribution and measurement of benefits in most funding structures for NFM interventions. With the low population densities across the Scottish Borders region, the case for large scale, measurable and concentrated intervention is difficult to prove.

Illustrative Investment Structure

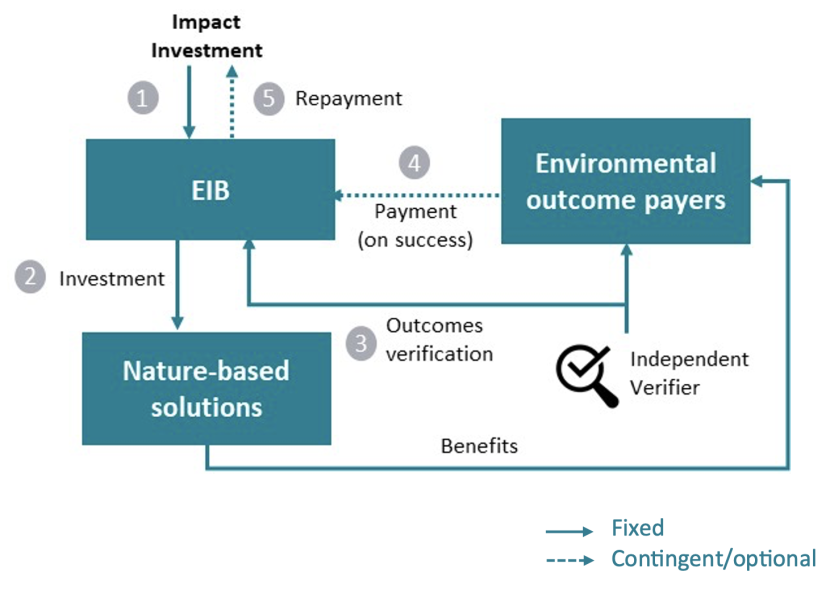

Where a key beneficiary can be identified, an Environmental Impact Bond (EIB) structure can attract upfront funding for delivery of nature-based solutions, with revenue generated from “outcome payers” upon successful performance.

Environmental Impact Bond

A EIB structure could enable private investment into the delivery of NFM and water environment interventions across the Tweed. This is achieved through the transfer of asset performance risk to investors with the agreement of a payment-for-success mechanism with a key beneficiary or beneficiaries. In this regard, the EIB mechanism relies on the identification of beneficiaries willing to pay for outcomes, and impact investors willing to take on a portion of performance risk.

To support the costs of ongoing monitoring and measurement and cover transaction costs associated with the mechanism, an EIB would likely look to raise a minimum of c.£10million.

- An EIB is set up based on contractual obligations of outcome payers to pay for specific environmental outcomes once verified. Assured by these contracts, impact investors provide upfront investment by subscribing to the EIB.

- The EIB is used to fund the implementation and operation of nature-based solutions to deliver the target outcomes. During the period of the EIB, it may pay a basic return to investors.

- An independent verifier confirms the environmental outcomes after a specific time period (this may need to be a period of several years).

- Outcome payers remunerate the EIB for the delivery of verified outcomes, based on performance against pre-agreed metrics.

- The proceeds received from outcome payers are used to repay investors. Investor returns are linked to the performance of the intervention against expectations – higher returns in the case of outperformance, and lower or nil returns in the case of underperformance.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Low |

|

|

Scale of opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

Low |

|

|

Replicability |

Medium |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Low |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

High |

|

Recommendations for future development

Further engagement with beneficiaries of water environment interventions is key to the further development of this approach. This includes further mapping of the beneficiaries of interventions, and the ecosystem services from which they benefit (or environmental hazards to which they are currently exposed). This model may be more appropriate in other regions of Scotland where issues are more severe, or where willing outcomes payors can be identified.

Riverwoods

Investment in riparian woodlands, or ‘Riverwoods’ as explored by the Scottish Conservation Finance Initiative, was identified as a medium-term opportunity for private investment in the Scottish Borders.

Riverwoods may be delivered through the funding models explored for woodland creation, nature-friendly farming and for investment in NFM and water environment.

Opportunity Summary

Riverwoods is an initiative to create a network of riverbank woodlands supporting healthy and resilient river systems, able to adapt to Scotland’s changing climate. This has been identified as a high ecological priority by the Tweed Forum.

Multiple benefit analysis carried out in the Eddleston catchment demonstrated the range of NFM, water quality and environment, biodiversity and amenity benefits provided. This is in addition to other known benefits (e.g., carbon sequestration).

Ongoing work led by Tweed Forum has identified an approximate cost of £10 million to deliver 200km of riparian woodland (width of 50m) in the Tweed (Tweed Forum, 2020). This may be subsidised by further productive woodland.

Priority areas include Upper Tweed, Ettrick and Yarrow, Teviot, Bowmont and Leader/Gala as priority catchments for diffuse pollution, provision of flood protection or as part of the Borders Forest Trust Wildwood area.

The Tweed’s riparian woodlands could be supported by identifying and engaging with the beneficiaries of the multiple outcomes delivered as well as the relevant landowners/land managers. Tweed Forum has also identified prospective funders interested in increasing the resilience of fisheries through riparian woodland planting. Riparian planting has also been delivered in the UK as part of nature-based solutions projects such as integrated constructed wetlands for water quality located on rivers alongside wastewater treatment plants to clean the outflow.

Key Barriers to Investment

The following key barriers to investment and scale have been identified:

- As a linear landscape feature, land suited to riparian woodland is typically distributed across a range of landowners, creating stakeholder complexity to deliver at scale.

- Riparian woodland provides multiple recognised benefits. Stacking and monetising these is often complicated, with specific barriers to each revenue stream.

- While NFM and water environment benefits are established, measurement and attribution can be complex, as can beneficiaries’ engagement.

- Carbon benefits may only be monetised where additionality can be demonstrated.

- Monetising biodiversity benefits requires policy development.

Illustrative Investment Structure

Riverwoods was identified as an opportunity to demonstrate the use of blended finance under the Scottish Conservation Finance Project’s The £1 Billion Challenge (Scottish Conservation Finance Project, 2020). Blended finance is the use of private repayable finance alongside concessionary or ”first-loss” capital to support a project. By structuring finance in different tiers of capital, mainstream investors can be attracted to projects due to the lower risk of losses provided by the public and/or philanthropic capital tiers.

While not exhaustive, key models explored in this report that may be applied to Riverwoods include the Scotland Carbon Fund, TIMO structures, EIBs and Habitat Banking. While each of these structures have unique challenges, several have the potential to be “stacked” to increase and diversify revenue streams to attract more investors to riparian planting projects. In addition, while no specific market or product (e.g., credit) for riparian woodland currently exists, further policy development could unlock a bespoke model for the delivery of riparian planting.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Medium |

|

|

Scale of Opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

Medium |

|

|

Replicability |

Low |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Low |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

High |

|

Recommendations for future development

- Delivery as part of wider woodland creation schemes based on agri-environment and/or carbon revenues.

- Explore opportunities to pilot stacked revenue stream development and multiple benefit monetisation, especially involving beneficiaries in the recreational fishing sector.

Nature-based Tourism

Nature-based Tourism was identified as a medium-term opportunity for investment in natural capital in the Scottish Borders.

Opportunity Summary

Nature-based tourism presents a significant opportunity with 3.3 million visitors to the Tweed annually. The natural capital of the Tweed catchment was identified as a primary driver of tourism in the Scottish Borders with popular recreational activities including mountain biking, hiking and fishing (NatureScot Research Report 1284). This relationship underpins the case for investment in natural capital by the sector.

Tourism Business Improvement Districts (TBIDs) can be used to capture and direct investment to maintain and enhance natural capital for residents and visitors. Alternative levy mechanisms such as taxes on local visitors or charges on fishing permits could be applied in a similar way.

GoTweedvalley is Scotland’s second TBID and was implemented to create a cohesive tourism destination marketing strategy to promote the Tweed valley. Through the TBID, 103 businesses will provide (expected) levies of £70,000 p.a. to invest in a range of schemes over five years (Tweed Valley Tourism Bid, 2020).

GoTweedvalley TBID aims to attract visitors to grow adventure tourism revenue streams. TBID revenues could be used to support larger capital investment in supportive tourism infrastructure or investment in the natural capital assets that underpin tourism opportunities.

Table 2. GoTweedValley business plan (2021-25) extract.

|

Breakdown |

Expenditure (5 year Total) |

|

Management and Organisational |

£125,000 |

|

Marketing and promotion |

£112,500 |

|

Infrastructure |

£40,000 |

|

Corporate Tourism |

£30,000 |

|

Contingency |

£17,500 |

|

Events and Festivals |

£15,000 |

|

Support and Advocacy |

£10,000 |

|

Total |

£350,000 |

Tweed Valley TBID

Key Barriers to Investment

The following key barriers to investment and scalability have been identified:

- The scale of funding available through the GoTweedValley TBID is currently limited. However, this may grow over time should this model gain traction with local tourism providers.

- Existing TBID mechanisms only allow for a five-year repayment horizon, limiting the term for investment.

- Limited appetite and financial capacity of businesses for levies, with many strained by the Covid-19 pandemic.

- TBID activities need to provide universal benefits to participating businesses, limiting the nature-based interventions that can receive direct support.

Illustrative Investment Structure

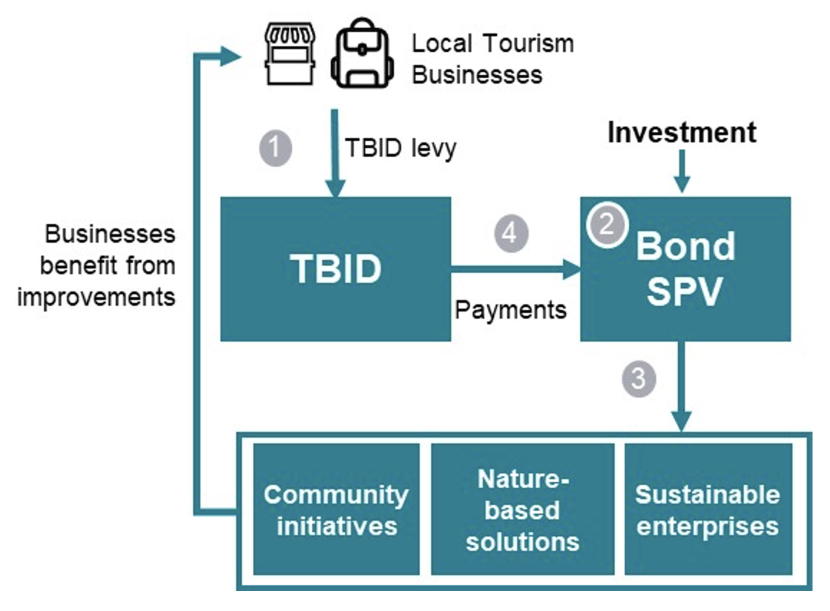

A TBID uses a revolving five-year business levy to support collective initiatives. Levy revenues could be leveraged to attract private investment.

A TBIDs five-year voting horizon limits the scale of investment that can be secured. A ‘licence based’ model with a longer review horizon may be used to increase the scale of opportunity.

Levies are paid by all (tourism) businesses in the TBID area, calculated as a percentage of business rates.

TBID and Bond Model

- Businesses vote on the creation of a TBID in a specified area, based on a pre-defined business plan and levy, and commit to paying levies to the TBID over several years.

- The TBID leverages its projected TBID revenues to issue a bond instrument, potentially via a separate SPV to which it provides guarantees and/or payments. The size of issuance depends on the scale and certainty of the potential revenue streams.

- Bond proceeds are used to finance shared nature-based infrastructures, sustainable enterprise or community initiatives providing benefits to all participating businesses.

- Bond investors are repaid by TBID levies over the term of the TBID. Any returns generated by investee projects are returned to and recycled by the TBID.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Low |

|

|

Scale of Opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

Medium |

|

|

Replicability |

Medium |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Low |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

Medium |

|

Recommendations for future development

Further growth of the tourism sector and the increasing recognition of businesses of their reliance on a well-functioning natural environment will expand the opportunity for NBS-focused TBIDs. The model will also benefit from:

- Development of TBID structures across Scotland, building on the precedent established by VisitInvernessLochness TBID and the GoTweedvalley TBID.

- Engagement with participating businesses to determine the scope and appetite for investment in specific nature-based solutions, and local natural capital priorities for participating businesses.

- An enterprise investment fund to support nature-based tourism enterprises was also identified as a potential opportunity for the use of finance. To develop this idea, further research into the investment needs of existing enterprises across the Tweed catchment is required.

- Evaluation of a more established, wide scale tourism levy for nature.

Biodiversity Offsetting

Biodiversity offsetting was identified as a longer-term opportunity in the Scottish Borders. While existing activity is innovative it is likely to require policy change and increased development demand to mature.

Biodiversity offsetting mechanisms are limited by the current policy environment. Policy change could support the development of this opportunity in the medium to long term.

Opportunity Summary

Biodiversity offsetting presents a key opportunity for strategic regional investment in natural capital that could be replicated across Scotland.

Biodiversity offsetting is currently delivered on a ‘no net loss’ basis in the Scottish Borders under local planning policy using section 69 and 75 agreements. This is led by Scottish Borders Council (‘SBC’).

SBC has secured £1.76 million over 11 years supporting a total of 13 offset schemes to date. Demand is hard to predict and has been primarily generated by windfarm development.

Biodiversity offsets across the Scottish Borders are currently delivered:

- On a qualitative basis;

- On aligned landowner land with limited long-term protections;

- On an ad-hoc basis; and

- Post-development, exposing the offset to delivery risks.

A strategic, quantified approach supported by a suitable policy mechanism could facilitate investment while supporting more cost efficient and ecologically impactful offsets while safeguarding the mitigation hierarchy.

Key Barriers to Investment

The following key barriers to investment and scale of this approach have been identified:

- There is currently no national policy for biodiversity mitigation from land use change. Internationally, standardised biodiversity offsetting or net gain policy has been a key prerequisite to the development of offset markets.

- Demand for offsets in the Scottish Borders has been driven by windfarm development. Development demand is inconsistent and hard to forecast in the region.

- Assessment of biodiversity mitigation is currently carried out on an ad hoc and qualitative basis (although like-for-like offsetting is targeted). Qualitative assessment may undermine credibility in negotiation with outcome payers (and subsequently investors).

- With a total population of c.115,000, the Scottish Borders is the 7th least populous council area in Scotland. As such, the demand for offsetting may be comparably lower than that of more densely populated regions (National Records of Scotland, 2019).

Illustrative Investment Structure

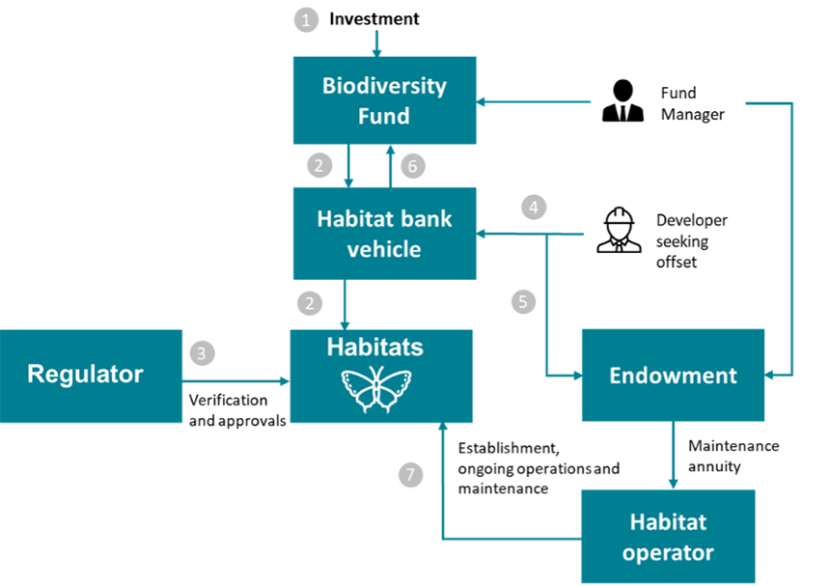

A market-based approach to conservation, Habitat Banking enables upfront investment in the creation and/or restoration of habitats to mitigate habitat loss elsewhere in the future as a result of development.

Habitat Banking

- Under this structure, investment is raised into a Biodiversity Fund.

- The Biodiversity Fund in turn invests into an SPV, known as the ‘Habitat Bank’. The Habitat Bank delivers nature restoration, either through land purchase, or through covenant agreements with long term landowners.

- The regulator (or an accredited, independent auditor) verifies and approves registration of the habitat bank and future offsetting delivered. This is likely to include a quantitative assessment of the biodiversity value of the habitat. Policy change could enable the commodification of value as ‘credits’, improving fungibility.

- To fulfil planning obligations (under section 69 and section 75 or future policy agreements) or under voluntary arrangements, developers make payments to the Habitat Bank for biodiversity offsets in accordance with the mitigation hierarchy.

- A portion of income received from developers can be captured to provide an endowment for the long-term management of the habitat site.

- Remaining funds are used to repay investors through the Biodiversity Fund.

- The site is managed by an operator on an ongoing basis, funded by the endowment.

Model assessment

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Maturity of business model |

Medium |

|

|

Scale of Opportunity in the Scottish Borders |

Low |

|

|

Replicability |

Medium |

|

|

Investment readiness in Scotland |

Low |

|

|

Social and environmental outcomes |

Medium |

|

Recommendations for future development

- The development of effective biodiversity policy to support a Habitat Banking market in Scotland is key to the further market development.

- Any future policy should be sensitive to local and regional needs and provide flexibility to allow the development of the market.

- Any future policy should be quantitative and clear for market participants. National policy may be designed for implementation at a regional level to ensure sensitivity to localised needs and priorities.

- Net gain policy should be considered as a legal requirement for all residential, commercial and infrastructure development, which if effectively designed can streamline planning while delivering net gains for the environment.

Other Investment Models

A range of additional investment models were considered as part of the assessment of opportunities in the Tweed catchment. While each of these could support Natural Capital investment, key barriers to deployment may prevent practical implementation at this stage.

Landscape Enterprise Networks (LENs)

LENs projects aim to link the management of and investment in landscapes to the needs of businesses and society as a whole. LENs projects focus on aggregating linkages between the providers and beneficiaries of ecosystem services

- Linking beneficiaries to providers allows them to impact the management of landscapes to support the needs of their businesses, enabling them to influence assets, services and risks relevant to their business from the landscapes in which they operate.

- LENs aggregates the supply of ecosystem services, reducing the transaction costs of contracting with multiple landowners across a landscape, and aggregates demand among multiple investors, creating collaborative value chains that avoid trade-offs between ecosystem services and minimise piggybacking of non-investing beneficiaries.

- LENs approaches hinge on the identification and matching of suitable buyers and sellers of ecosystem services. The Project identified a limited network of potential beneficiaries that may be willing to pay for environmental outcomes across the Scottish Borders, restricting further development of the LENs approach.

- The ability to attract private investment to deliver interventions is dependent on clear evidence of demand for the outcomes from paying beneficiaries. Where a bespoke LENs structure is established, there may be an opportunity for finance.

Place-based trust

- An independent vehicle is established to provide strategic management of assets funded through an endowment and/or relevant natural capital revenue streams.

- This model is suitable for managing assets and co-ordinating projects which can be governed by a single entity (e.g., urban greenspace, community woodlands, Marine Protected Areas etc).

- Tweed Forum currently performs many of the functions of a place-based vehicle effectively within the project area.

EnviroCAT Bond

- A catastrophe bond is used to finance natural assets to decrease the likelihood of insurance trigger events.

- Well suited to large scale financial risks and defined interventions but requires close cooperation and engagement with the insurance and/or reinsurance sectors.

- This approach requires a minimum scale of environmental (and financial) risk to support the case for development. The Project did not identify a suitable case for development in the Scottish Borders.

Assessment of Investment Priorities

The overall assessment of each natural capital business model has been refined through market analysis and engagement with local and national stakeholders. Table 3 details the ranking of each opportunity against the five key assessment criteria outlined in Longlist Opportunities for Investment section.

Table 3. Opportunity Assessment Matrix.

|

Opportunity Theme |

Maturity of business model |

Scale of opportunity in Borders |

Replicability |

Investment in Scotland |

Social and environmental benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Woodland Creation |

High |

High |

High |

Medium |

High |

|

Peatland Restoration |

Medium |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

Nature Friendly Farming |

Medium |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

NFM and Water Quality |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

High |

|

Riverwoods |

Medium |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

High |

|

Tourism |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

Low |

Medium |

|

Biodiversity |

Medium |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

Medium |

The opportunity for a Scotland Carbon Fund to support investment in peatland restoration and woodland creation was identified as the highest priority for further investigation for the remainder of the Facilitating Local Natural Capital Investment project. The structure was selected based on the opportunity to deliver landscape scale change both across the Tweed catchment and nationally, while facilitating market development in the two highest priority investment opportunities.

Existing market infrastructure under the Woodland Carbon Code and the Peatland Code was also considered sufficient to support a pilot programme without the need for further policy development or an extended period of stakeholder engagement.

Priority Investment Structure - Scotland Carbon Fund

Scotland Carbon Fund

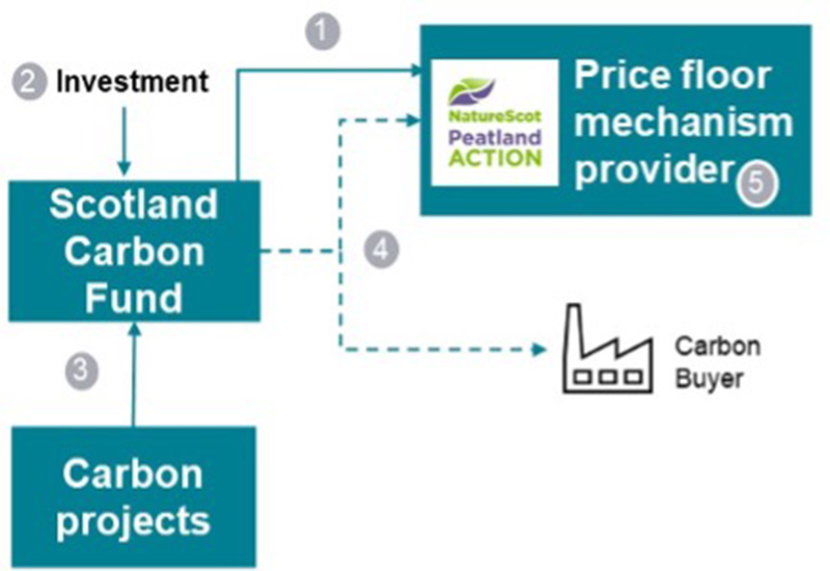

The opportunity for a Scotland Carbon Fund, supported by a price floor mechanism, was selected for further research and application to a case study project in the Tweed catchment.

The leverage of private capital through the fund will facilitate efficient, large scale habitat restoration to sequester or avoid carbon emissions and deliver a range of additional ecosystem benefits. The fund vehicle achieves this by providing carbon market liquidity and transparency, reducing the friction costs of transactions and attracting more investment to the sector through scale and project diversification. Market development will also promote competition driving efficiencies in the sector.

A price floor mechanism can be used to further the benefits generated by reducing the cost of capital to the fund and encouraging development of the market.

In this section we consider the Scotland Carbon Fund, price floor mechanism and aligned tools in further detail. Model structure options section provides a summary of structural options for the fund while Price Floor Mechanism section considers the function of a price floor as a policy tool in supporting market development. Benefits / Outcomes section summarises the expected benefits and key target outcomes of this approach, with an indicative fund structure explored in Indicative Structure section. Finally, Further Mechanisms section provides an introduction to key aligned tools enabled by the fund, including mechanics around revenue shares, endowments and conservation dividends.

Model structure options

Three distinct financing mechanisms were considered to support the delivery of carbon offset projects across woodland and peatland landscapes, considering both project finance and liquidity structures.

Project Finance

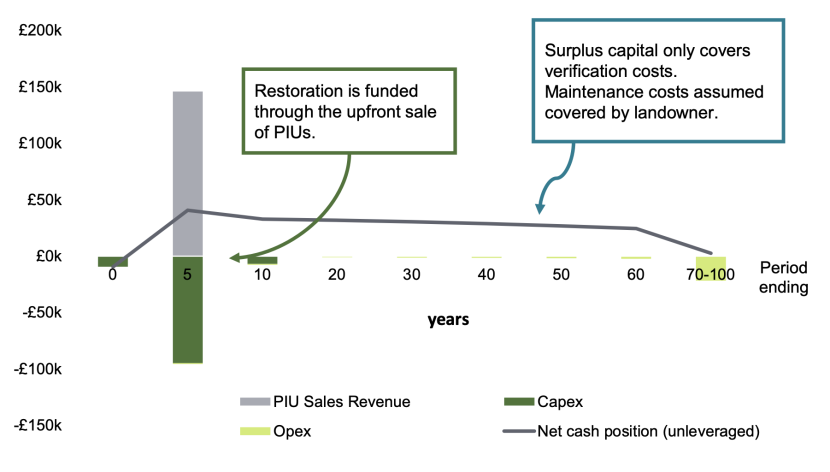

A traditional project finance vehicle provides funding to support capital delivery works (e.g. habitat restoration) in advance of revenue generation.

Currently, under the Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code, pre-verified credits (termed ‘pending-issuance units’ or ‘PIUs’) may be sold early in the project life, in advance of verification. This upfront or ‘ex-ante’ sale of pre-issuance carbon units to support long term financing removes the need for project finance by bringing forward lifetime carbon revenues to the start of the project.

Therefore, instead of requiring funding for capital delivery works, project developers require liquidity to ensure that credits can be sold easily at a suitable price to support viable project delivery. The Scotland Carbon Fund is designed to be this liquidity provider.

Liquidity Structures

The project considered the options for both short and long lifecycle vehicles to provide liquidity to market participants. It was identified that a long-term vehicle was best suited to supporting restoration activity.

Short term liquidity

A liquidity vehicle aims to support project delivery by facilitating market transactions in PIUs. This provides benefits including market transparency, efficiency and price discovery. By providing a reliable and straightforward source of demand for PIUs in the market and reducing friction costs for sellers, a fund will provide access to more buyers, and at a greater scale.

A short-term liquidity vehicle purchases, aggregates and sells pre-issuance units to corporate offtakers within 1-3 years. The vehicle provides a return to its investors based on a margin between the PIU purchase and ultimate sale price of aggregated credits. This model is highly speculative and relies on short term market price increases to generate returns for investors.

Long term liquidity

Unlike a short-term vehicle, the equity fund will look to buy and hold either all, or a portion of, PIUs purchased through to verification as Woodland or Peatland Carbon Units (W/PCUs). Investor returns are driven by the increase in value of credits over time and through verification. In this way, the vehicle can afford to pay a higher price for the purchase of PIUs than the short term vehicle, thereby passing more value through to the underlying project and its stakeholders. Additionally, the project (or landowner) may form an agreement with the fund to share in the upside of `the long-term growth in the value of carbon credits based on their own risk appetite.

Table 4. Target fund models.

|

Type |

Description |

Type of capital |

Lifecycle |

Investor Risk Profile |

Indicative Investor Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Short term |

PIUs are purchased upfront and sold within 1-2 years to corporate offtakers |

Equity |

Short (2-5 years) |

High |

15%+ |

|

Long term |

PIUs are purchased upfront to cover delivery costs, and a portion are held by the fund for sale over time |

Equity |

Long (5+ / Evergreen) |

Medium/ high |

5-15% |

The equity fund structure was selected as the most suitable approach for the Scotland Carbon Fund, providing liquidity to market participants, flexibility for sellers and passing through maximum value to the project. The lower end of the spectrum for the investor return is likely to rely on a floor price mechanism to provide greater price certainty.

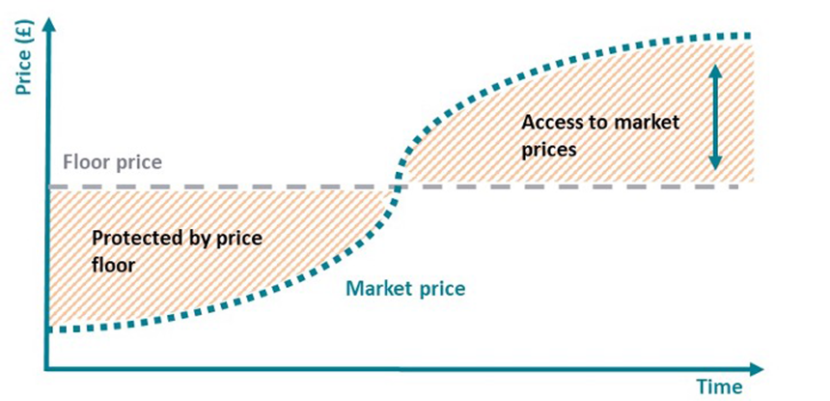

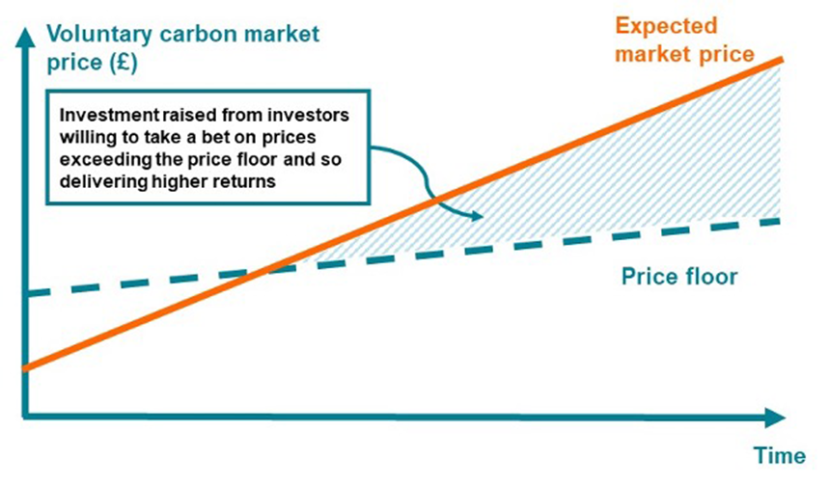

Price Floor Mechanism

A price floor mechanism is a form of guarantee that increases the opportunity to attract private investment. Price floor mechanisms are used to accelerate market development by removing the risk that prices fall in the future through a guarantee to recipients. The market function of a guarantee mechanism is reflected in Figure 13 below:

A Carbon Guarantee would mitigate against the risk of the public sector crowding out private funds, a problem often seen with standalone upfront grant programmes and reportedly a current issue with the design of the Peatland Action programme in Scotland (as explored by Professor Mark Reed in Annex 3).

Key benefits include:

- Providing certainty to investors/developers over future revenues.

- Mitigating market risk for investors at the fund level thus enabling the fund to access a lower cost of capital as investors are satisfied with a lower target return.

- This mechanism may allow for the targeting of specific outcomes by setting guarantee qualification criteria accordingly e.g., targeting more biodiverse projects.

Precedent Guarantee Mechanisms

Price floor mechanisms have been used to accelerate development of new markets in other contexts. Key recent examples in the UK include the Feed-in-Tariff for renewable energy and the Woodland Carbon Guarantee (in England only) and are detailed below. Under these structures, price floors are set by government agencies to support market development. Floor-pricing can be set by the guarantor either as a fixed price for all guarantee recipients or at different prices for recipients up to a maximum price, awarded via competitive reverse auctions.

Feed in Tariff (FiT)

The FiT was a UK government programme introduced in 2010 designed to promote uptake and financing of renewable energy generation technologies by providing market access and price certainty for energy generated alongside subsidy payments. Guaranteed prices are set centrally at fixed tariff rates (based on technology type), providing revenue for 20 years.

Woodland Carbon Guarantee (WCG)

The WCG is a £50 million government scheme designed to stimulate woodland creation in England through a guaranteed price for Woodland Carbon Units generated by 2055/56. Projects compete in reverse auctions for price floor agreements, bidding below a maximum (reserve) price determined by the Forestry Commission which runs the scheme.

A Peatland Carbon Guarantee for a Scottish Carbon Fund

Scotland has committed to delivering £250 million of funding to Peatland Restoration through the Peatland Action programme by 2030. A portion of this could be used to provide a price floor mechanism to help deliver this target by leveraging private sources of finance. A price floor mechanism may be used to reduce private investor risk, attracting investment at a lower cost and so reducing market friction costs. Where market prices rise in the future beyond the guaranteed price level, guarantee holders will sell PCUs into the market instead of to the guarantor, thus potentially reducing the financial burden on the public sector.

This report proposes that the price floor mechanism will be most effective when delivered alongside the Scotland Carbon Fund. This differs from the approach taken by the Woodland Carbon Guarantee operating in England which operates through a reverse auction system working with landowners and project developers. A fund level structure is expected to provide a more streamlined and straightforward funding process with fewer friction costs for participants, thereby increasing the proportion of the carbon payment delivered to the project. Importantly, a fund level structure is expected to attract investment on a more competitive basis. By aggregating investment opportunities, the fund can drive competition amongst prospective investors. Aggregation also may provide access to the most cost-effective forms of capital including institutional investment. Institutional investors typically have a minimum investment value and specific risk and management requirements. This can be delivered at the fund level in a way that is not economical on a project-by-project basis.

While this section is focused on the opportunity for peatland restoration, in practice this approach may also be applicable to other landscapes (e.g., woodland). Further analysis of woodland creation case studies would need to be carried out to refine the fund structure to suit the specific characteristics of the woodland carbon market.

How it works?

- A price floor is set by the Scottish Government and awarded to the Scotland Carbon Fund for a certain volume of PCUs.

- The carbon fund raises finance from impact investors seeking exposure to UK carbon markets.

- Projects sell PIUs to the fund, with proceeds of sale funding site delivery.

- Income is generated by the fund from the sale of:

- PIUs to corporates or brokers;

- PCUs to corporates for use as offsets; or

- PCUs to the guarantor where the market price is below the guarantee price.

- The guarantee reduces downside risk for the fund’s investors, enables cheaper finance to be accessed and as a result higher PIU prices are offered to projects, thereby stimulating market supply.

This mechanism has been endorsed in principle by the UK IUCN Peatland Code team as an important means of expanding Scotland’s peatland carbon market and overcoming barriers to market growth (as explored in Annex 3).

Investor Implications

Investors in the Scotland Carbon Fund are exposed to two main forms of risk, project and market risk.

Project risk relates to the risk that PIUs are not successfully verified as W/PCUs due to failure to comply with the terms of the management agreement under the Peatland Code / Woodland Carbon Code. Where PIUs are not verified, the investor will lose out on their investment (as W/PCUs cannot be sold). Project risk can be mitigated by diversifying across a portfolio of projects and through other tools, such as contractual agreements with landowners.

Market risk relates to uncertainty in the pricing of PIUs and verified carbon units (PCUs for Peatland Code projects and WCUs for Woodland Carbon Code projects) in the voluntary carbon markets. This is driven by a range of external economic factors such as inflation. Where a price floor is agreed, the risk to investors falls, as shown in Figure 15. As illustrated, investor is only exposed to market risk above the price floor (shaded in blue). If the price of carbon rises above the price floor the investor benefits from the market pricing; should the price fall, the investor is protected by the price floor mechanism.

Under normal market conditions, the target or ‘risk adjusted’ return required to attract investors is proportionate to the perceived risk taken. By reducing market and project risk and aggregating opportunities, the target return required to attract investment can be reduced. At the same time this may make the fund more attractive to more and larger scale investors.

Government spending under a price floor

Table 5. Illustrative floor price mechanism.

|

Funding Round |

Starting Floor Price (£/ carbon unit) |

Year 1 Price |

Year 5 price |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Round 1 |

£15 |

£15.38 |

£16.97 |

|

Round 2 |

£13 |

£13.33 |

£14.71 |

|

Round 3 |

£11 |

£11.28 |

£12.45 |

As depicted in Table 5, the price floor is set in individual funding rounds. A starting floor price for a given funding round is set based on analysis of market needs. Future starting floor pricing may be adjusted over time to respond to changing market conditions (e.g., falling restoration costs). Once set, the floor price inflates from the starting price overtime, in line with RPI. Floor pricing can also be designed to prioritise / rewards specific project qualities.

Table 6. Illustrative government spending based on annual carbon price growth to support a £50m fund. 'Government Expense over life' discounted at 3.5%. Modelled fund assumptions are identical to those detailed in Indicative Structure section.

|

Annual Carbon Price Growth Rate |

Investor IRR (30 years) |

Government Expense over life (NPV) |

|---|---|---|

|

0% |

3.5% |

£39 million |

|

5% |

5.2% |

£1.79 million |

|

10% |

9.3% |

£nil |

|

15% |

11.0% |

£nil |

Under all scenarios, it has been assumed that the guarantee is able to leverage 1.3x of upfront private investment on a Net Present Value (“NPV”) basis. In the “worst case” illustrative scenario, carbon market prices are flat or decline and the price floor is fully exploited, investors receive a return of 3.5%. This is achievable with 45% percent of PIUs sold upfront to generate a return.

If market prices rise by greater than 6.38% p.a. it is expected that all of the guarantee holders will sell entirely in the market, and not exercise any rights to the price floor guarantee. This will result in a future windfall to the guarantor of the full value underwritten, which can be recycled or used to support the sector. In the case that prices rise by 5% per annum, the total value of government payments under the guarantee would be less than £2 million on an NPV basis.

Benefits / Outcomes

Despite significant interest from private investors and carbon offtakers, inadequate supply of suitable projects limits uptake of either the Peatland Code or Woodland Carbon Code, the latter particularly in relation to nature-friendly forestry planting and practices. Used in conjunction, the proposed Scotland Carbon Fund and Price Floor Mechanism could help to overcome many of the key barriers to project delivery identified. These include:

- Carbon pricing – prices paid for PIUs are too low to incentivise action or compensate for revenues foregone and do not account for value of other ecosystem services provided.

- Price uncertainty – carbon prices are volatile and highly project-dependent while voluntary carbon markets lack transparency and are complex to access, generating uncertainty for landowners and project developers.

- Contractor availability – a limited body of skilled contractors are available to carry out peatland restoration work. Underinvestment is driven by uncertainty over market demand.

- Agri-environment income uncertainty – landowners are concerned that actions may limit eligibility for agri-environment scheme revenues now or in the future.

- Design of public funding programmes – capital grants (e.g., Peatland Action) are often considered as substitutes for carbon financing.

- Contract length – landowners are concerned by the length of contracts without attached revenues and the risk that entering into a long-term commitment may depress land values.

Table 7 explores how the proposed market mechanisms can overcome these barriers.

Table 7. How the Scotland Carbon Fund and Price Floor Mechanism overcome key barriers to market development.

|

Barrier |

Scotland Carbon Fund |

Price Floor Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

|

Carbon Pricing |

|

|

|

Price Uncertainty |

|

|

|

Contractor Availability |

|

|

|

Agri-environment income uncertainty |

|

|

|

Design of public funding programmes |

|

|

|

Contract Length |

|

|

Key stakeholder outcomes

By overcoming these barriers, the delivery of private investment through the Scotland Carbon Fund would provide significant benefits to a broad range of stakeholders, especially if supported by a price guarantee mechanism. The proposed structures have the potential to be delivered in line with, and further the goals and principles of the Just Transition. Some of these beneficiaries are explored below.

Nature and the environment – the Scotland Carbon Fund structure provides increased opportunity for peatland restoration and woodland creation with associated biodiversity, water environment and carbon benefits. The fund could provide market leadership in voluntary carbon quality to ensure counterparts follow robust standards.

Communities – the fund investment criteria can be structured to reward community benefits such as public access, ownership or where appropriate, enterprise, in line with the principles of the Just Transition. Where community ownership is promoted (through the Scotland Carbon Fund or aligned vehicles) local participation will facilitate the reinvestment of profits within the community.

Landowners and managers – the proposed structure for the Scotland Carbon Fund resolves key barriers to market participation faced by landowners, as explored in Table 6. This includes increased flexibility of compensation with the accommodation of both an upfront payment and/or annualised maintenance revenues. The Scotland Carbon Fund may also be designed to promote or prescribe specific payment structures to align landowner incentives to the delivery of specific environmental (or social) outcomes.

Project developers and contractors – benefit principally from the scale up and aggregation of the market and greater certainty of ongoing market demand. The Scotland Carbon Fund is also complementary to developers by driving demand, providing liquidity and reducing the ‘friction’ costs of transaction. Particularly relevant in the case of peatland restoration, this will enable investment in equipment and training of specialist delivery providers. Finally, where successful, this model builds the business case and mechanism for further restoration (or creation) markets.

Government and public policy – benefit through not only the progression of national targets for climate and nature, but also improved efficiency of public spending on restoration. Under the proposed model, public spending is reserved for targeted and impactful interventions with a larger share of the market serviced with private funding. The price floor mechanism has the potential to reduce overall public spending if existing publicly funded grant schemes are applied, and private finance assumes the risk of delivery (with a price floor mechanism only linked to verified credits). Implemented together, these mechanisms can remain flexible and responsive to target changing priorities. The proposed structure also offers wider benefits, including green job creation, growth of the restorative economy and increased engagement from more mainstream institutional investors in natural capital markets. This can be achieved while maintaining alignment with wider priorities for Scotland’s natural capital, with the option for NatureScot and other partners to be involved in fund governance and oversight (if preferred).

Key risks and mitigations

While this project has identified the significant opportunity for a Scotland Carbon Fund to facilitate increased private investment into Scottish peatland and woodland, there are risks to the successful delivery of this model. Table 8 sets out the key risks, and proposed mitigants to the successful operation of the Scotland Carbon Fund.

Table 8. Key risks and mitigants to the success of the Scotland Carbon Fund.

|

Risk |

Risk level |

Mitigating factors |

|---|---|---|

|

Lack of landowner and project developer awareness or capacity to take advantage of the Scotland Carbon Fund. |

Medium |

|

|

Fund seen as private sector profiteering enterprise. |

Medium |

|

|

The value of PIUs of later vintages is heavily discounted by the market. |

Medium |

|

|

The Scotland Carbon Fund is unable to attract private investment for initial capitalisation. |

Low/ Medium |

|

|

Lack of demand for credits from carbon market offtakers. |

Low |

|

|

Investor appetite is weighted towards shorter investment terms.

|

Low |

|

|

Projects are economically unviable based on carbon revenues alone.

|

Low |

|

Indicative Structure

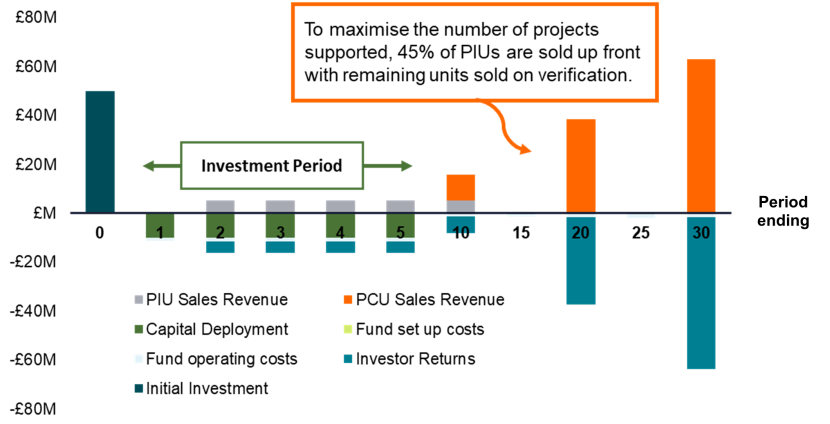

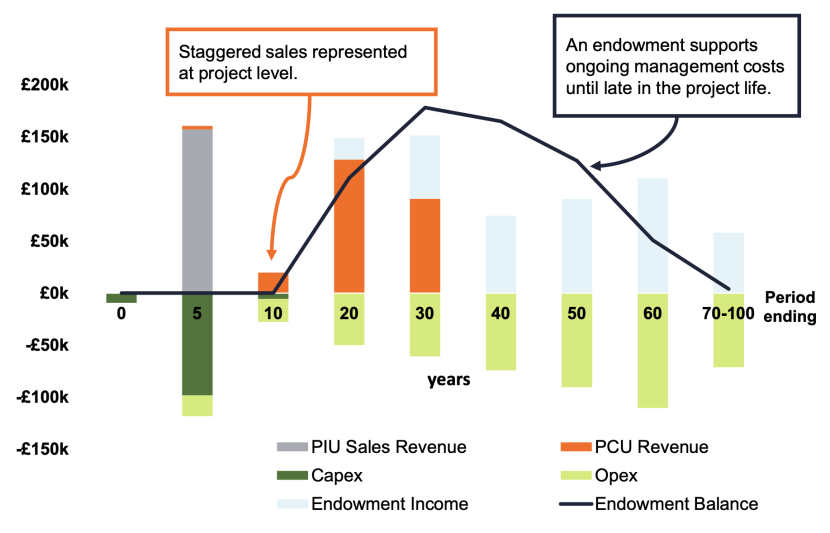

As an investment vehicle, a Scotland Carbon Fund would operate as a “market maker” providing liquidity to market participants. The function and operation of the fund vehicle is illustrated in Figure 16. which displays the projected lifetime cashflows of a £50 million Scotland Carbon Fund focused on peatland restoration.

As depicted, the proposed fund has a 30-year lifecycle, with capital raised and deployed within the first 5 years and investment returns realised by year 30. The model assumes that the fund is able to deploy a total of £50 million within the first 5 years, purchasing PIUs from peatland restoration projects across Scotland. In this illustrative structure, 45% of PIUs purchased are sold to market offtakers prior to verification with the remaining PIUs held until maturity as PCUs (In a shorter-term fund, a greater proportion of PIUs are sold upfront, in advance of verification). Sales are structured so that PIU vintages associated to abatement beyond the fund life are sold first, so that near-term PCUs can be verified and monetised. Profits from the sale of carbon units are used to repay investors.

Modelled assumptions are summarised in Table 9. Key outputs are summarised in Table 10. As detailed, the £50 million fund illustrated would support the restoration of 35,000ha of degraded peatland, abating 5.4 million tCO2e over 50 years.

Table 9. Scotland Carbon Fund modelled assumptions.

|

Key assumptions |