Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) Specialist Report - Conservation Breeding

This report should be cited as: Barclay, D. Senn, H. (2023). Scottish Wildcat Action final report: Conservation Breeding, NatureScot, Inverness.

Authors and institutions: David Barclay, Royal Zoological Society of Scotland

Dr Helen Senn, Royal Zoological Society of Scotland.

Year of publication: 2023

Keywords:

Breeding; captive; ex-situ; zoos; population; programme; studbook; management.

Background to SWA

The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP) was published in 2013 following the input of over 20 partner organisations. This led to the establishment of the Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) project that ran from 2015-2020, funded by the Scottish Government, National Lottery Heritage Fund and others. SWA operated with a team of project staff managed by NatureScot, and associated work was carried out by various partner organisations. The overall work programme was steered by a group made up of ten of the partners. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Cat Specialist Group reviewed the work of the SWA, and other ongoing wildcat conservation work, and provided recommendations for future action (Breitenmoser et al., 2019). A wide range of topics relevant to wildcat conservation were covered during the SWA, and have now been published as a series of reports, of which this is one. These outputs will inform the next phase of wildcat conservation work in Scotland, including the SavingWildcats ‘SWAforLife’ project that runs from 2019-2026.

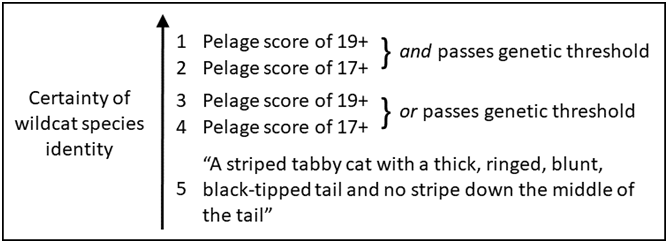

Wildcats hybridise with domestic cats and we use a combination of morphology and genetics to distinguish wildcats from domestic cats and their hybrids. The method applied is generally determined by the practicalities of management. For example, it is much easier to have high confidence in the pelage scores from a sedated cat, than from a camera-trap image taken at night. Genetic and pelage results can only be generated jointly in certain scenarios. Therefore, identifications under different situations have different levels of confidence associated with them. We therefore set different thresholds for identification of wildcats based on the ability to distinguish pelage and genetic characteristics in different situations. The confidence hierarchy, and the definitions used in this report, are given below.

A ‘wildcat’ in this report is defined as a cat with a 7PS pelage score of 17+ and that passes the genetic threshold for the genetic analyses. However, the thresholds for one can be reduced if it passes the other. See the scoring matrix in the main text for further details.

Background

For species whose wild populations are threatened by extinction, like that of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland, captive breeding programmes can act as a vital conservation support tool. A captive (conservation) breeding programme was identified as a valuable resource in the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP) (Anon., 2013) under objective 3: “taking forward work to underpin a wider conservation programme”. Two projects were launched as part of a long-term “ex-situ” programme ensuring that captive populations of wildcats remained as an integral part of their conservation actions. Since 2015 Scottish Wildcat Action (SWA) partners the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) have managed the UK’s Wildcat Captive Breeding Programme, which is part of the wider European Associations of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) Felid Taxon Advisory Group (Felid TAG) as a Monitoring Programme (Mon-P). In the last five years RZSS, working closely with captive holders across the UK and with specialists in Europe, has implemented a range of population management techniques to develop the captive breeding programme and ensure it has the potential to support future wildcat reinforcement.

Summary of work

- Assessing genetic status of captive population: RZSS took over management of the Scottish Wildcat Breeding Programme in 2015. Between 2015 and 2017 captive samples were acquired from all fertile captive wildcats held in UK collections that were included in the Scottish Wildcat Studbook. Following genetic screening using the Wildcat Hybrid Scoring Protocol (Senn and Ogden, 2015), results were used to support population management decisions.

- Acquisition of more wildcats of known genetic status to increase genetic diversity of captive population: RZSS engaged with landowners and gamekeepers from 22 estates out-with the SWA Priority Areas (PAs) to assess sites for potential wildcat presence and to collaborate with landowners in the event of accidental trapping of suspected wildcats. To date, 13 suspected wildcats were screened to assess hybrid genetic status, pelage and disease. From the 13 suspected wildcats, only two have been kept and included in the conservation breeding programme.

- Update of captive husbandry guidelines: In 2016 RZSS published Wildcat Captive Husbandry Guidelines (Barclay et al. 2016) and disseminated these to all wildcat holders. The guidelines identified the recommended standards for captive wildcat management, housing, breeding, veterinary care and welfare. Following the publication of these husbandry guidelines, RZSS undertook further work to explore the additional management challenges relating to conservation breeding for reintroduction. This work will be refined further with input from international specialists as a support tool for future conservation breeding for release.

- Captive breeding: Following breeding programme best practice guidance from the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA) during the period from August 2015 to October 2019, the captive wildcat breeding population increased by 67.2% from 64 animals (24.40)[1] to 107 animals (47.60). This population growth was supported by new captive holders joining the breeding programme, which has increased the enclosure space for new wildcat breeding pairs. Annual breeding success from the five breeding seasons between 2015 and 2019 has resulted in an average annual offspring survival rate of 85%. Currently all wildcats in the breeding programme are available for continued breeding following the genetic and pelage assessments carried out in 2017 as detailed in the Wildcat Hybrid Scoring Protocol. Population management is undertaken using the Single Population Analyses and Record Keeping System (SPARKS) and Pedigree Analyses and Management Software (PMx), following best practice population management guidance (EAZA, 2019).

1Male / Female

Acknowledgements

The SWA project was supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

It was also funded by the Scottish Government, NatureScot and the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. Support and resources for associated work was also provided by all the Steering Group members: Cairngorms National Park Authority, Forestry and Land Scotland, National Museums Scotland (NMS), Scottish Land & Estates, NatureScot, Scottish Wildlife Trust, The National Trust for Scotland, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, The Scottish Gamekeepers Association, The Scottish Government, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU). In addition, Jenny Bryce and Fiona Strachan helped develop the project while Eileen Stuart, Alan Bantick and Andrew Kitchener chaired the Steering Group.

Additional sponsors, funders and contributors to SWA work included Aigas Field Centre, Ailsa Black, British Association for Shooting and Conservation, Cairngorm Brewery Company, Chester Zoo, Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, John Muir Trust, Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, Lukas Ruiter Production, MyPetOnline, NFU Scotland, petDetect, RSPB, Scotland The Big Picture, Swift Ecology and The Highland Council.

We are also very grateful to the many academics, landowners and managers, farmers, foresters, keepers, captive collection managers, veterinary specialists and others who contributed valuable time and effort, members of the public who contributed funds and support, and in particular the many volunteers who got involved in the project.

The work carried out under the Scottish Wildcat Breeding Programme has been supported by all captive holders. The success of population management programmes is attributed to a collaborative approach, good communication and effective management and we are extremely grateful to all holders for staying committed to the wildcat breeding programme ensuring that the UK captive population remains a highly valuable resource to support long-term conservation. We would like to specifically thank SWA supporters and wildcat holders Aigas Field Centre, Chester Zoo and the Aspinall Foundation for their additional contributions and investment in captive wildcat management. We would also like to thank our European colleagues at the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) and Nordens Ark (Sweden) for their expertise, advice and support toward wildcat conservation in Scotland. Finally, we would like to thank Alexander Sliwa and André Stadler (chair and co-chair) of the EAZA Felid Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) for their specialist advice in captive population management, which has provided valuable support in the continued development of this captive breeding programme.

1. Introduction

The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan (SWCAP) included various ex-situ measures (recognising that these actions are just the start of a long-term programme), which highlighted an integrated approach and determination to develop effective long-term strategies for wildcat conservation in Scotland (Anon., 2013). The SWCAP identified a range of actions to deliver a pragmatic and collaborative approach towards captive management, ensuring that it remains a key element of wider conservation efforts.

The SWCAP identified the following ex-situ measures, led by Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS):

3.1 – Develop a captive breeding programme for wildcats with a view to reinforcing populations in the wild in the future. N.B. this will require that the risks to wildcats have first been addressed in potential release locations.

Given the increase in extinction trends for globally threatened species, the number requiring conservation breeding programmes (CPBs) is likely to increase dramatically (Conde et al., 2013). It is also recognised that captive breeding represents one of a myriad of tools conservation biologists have at their disposal to help prevent the extinction of a species, subspecies or population (Leus, 2011). However, captive breeding as a tool is not new to species conservation and has been a recommendation from the International Union for Conservation on Nature’s (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (SSC) for at least the last 32 years. This is evident from the 1987 IUCN Policy Statement on Captive Breeding, which states:

“Management to best reduce the risk of extinction requires the establishment of supporting captive populations much earlier, preferably when the wild population is still in the thousands. Vertebrate taxa with a current census below one thousand individuals in the wild require close and swift cooperation between field conservationists and captive breeding specialists, to make their efforts complementary and minimise the likelihood of extinction.”

Despite the extensive experience of ex-situ collections (i.e. zoos and private facilities) in maintaining animal collections through breeding programmes, many challenges still exist in their application as source populations for reinforcement or reintroduction projects. It is well documented that reintroduction attempts of a variety of captive-reared endangered species or populations into the wild have historically had mixed success (Griffith et al., 1989; Wolf et al., 1996, 1998; Fischer and Lindenmayer, 2000; Frankham, 2008; Fraser, 2008). However, past studies, for example by Wolf et al. (1996), found that up to 53% of avian and mammalian reintroductions were successful in leading to apparently self-sustaining populations. With regards to felids, other studies have also highlighted previous success with using captive populations. Breitenmoser (2001) recorded the outcome of two reintroduction projects using only captive-bred wildcats (Felis silvestris) and lynx (Lynx lynx) as being successful with the outcome of one other lynx project uncertain. More recently the highly successful Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) reintroduction projects, where wild populations have grown from 92 individuals to over 680 by the end of 2018, have also shown the significant recovery potential when using captive-born animals (Simón Mata, 2018). Captive breeding to support future reintroduction has been recommended in both the 2004 report The Scottish Wildcat: Analyses for Conservation and Action Plan (Macdonald et al., 2004) and the current SWCAP (Anon., 2013), highlighting again its valuable role in wildcat conservation.

1.1 UK wildcat captive breeding programme

In their simplest form, captive breeding programmes are long-term insurance policies that can, when needed, play a vital role in supporting species conservation efforts. More specifically, captive populations can maintain physically and mentally fit populations with a high level of genetic diversity that can act as potential source populations for species recovery projects. In situations like this, when conservation support is the primary focus (e.g. reinforcement / reintroductions), breeding programmes are often referred to as conservation breeding programmes, emphasising the more direct role of the population in species conservation. Given the breeding programme’s close alignment with current wildcat conservation efforts, including reintroduction planning, the terminology for this report will use conservation breeding programme as opposed to captive breeding programme. To support the development of a wildcat conservation breeding programme, the following actions were recommended in the SWCAP under project 3.1.

3.1.1 - Assess the genetic status of the current captive population

3.1.2 - Acquire more wildcats of known genetic status to increase the diversity of the captive population.

3.1.3 - Update the existing wildcat husbandry manual and disseminate to all holders. Standards will be a condition of participation in the captive breeding programme.

3.1.4 – Captive breeding.

A UK studbook, which is both a historical and living dataset of all wildcats held in captivity, has been in existence, in some form, since it was established privately in the late 1990s / early 2000s. The studbook remained in private hands until 2007, when it was taken over by the Aspinall Foundation. During this time the UK studbook for wildcats was accepted as an official Monitoring Programme under the EAZA Felid TAG. This development gave the studbook increased credibility, as well as access to a wider support network from European specialists in population management. In 2015, shortly after the launch of the SWCAP, the studbook was taken over by RZSS Highland Wildlife Park. Since 2015, the wildcat studbook has been developed to function as an effective conservation breeding programme, working closely with UK wildcat holders, the European zoo community, specialist advisory groups and European best practice guidance.

2. Methods

Successful management of breeding programmes can be affected by a variety of factors including species, space, breeding success, quality of data, programme status, population size, demographics, genetic status and level of communication. It is also vital that programmes have a collaborative approach between its members (species holders) to ensure consistency with animal management, breeding, welfare and imports/exports. The methodologies described below highlight a range of techniques synonymous with best practice captive population management, as well as newer/innovative techniques that support population development. It is important to note that despite the UK wildcat being the same subspecies, Felis silvestris silvestris, (Kitchener et al., 2017) as the European (mainland) wildcat, the breeding programme is currently specific to the British population.

Despite captive wildcats having previously been exchanged and bred, significant challenges still existed that restricted the UK population functioning effectively as a conservation breeding programme. From 2015 onwards, and in support of the SWCAP, RZSS implemented a range of actions to develop the captive population and ensure it functioned with greater long-term sustainability and genetic management as the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Breeding Programme.

2.1 Assess the genetic status of the current captive population

One of the greatest threats to wild-living populations of wildcats is introgressive hybridisation with domestic and feral cats, Felis catus. In order to implement a standardised system for assessing the level of hybridisation and how it should be integrated into wildcat conservation efforts, including the conservation breeding programme, a Wildcat Genetic Hybrid Scoring Protocol was published in 2015 by RZSS (Senn and Ogden, 2015). In the absence of whole genome sequencing, the hybridisation genetic test would assess a sample of genetic markers, based on 35 SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphism) DNA markers and one mitochondrial marker, to estimate the extent of hybridisation with a measured degree of confidence (Senn and Ogden, 2015). Data from this work and subsequent study (Senn et al., 2011), based on samples collected from across Scotland, highlighted that the wild-living cat population in Scotland is a hybrid swarm (see SWA specialist report Genetics and Morphology).

Using the available genetic data, a pragmatic approach was adopted in the Wildcat Hybrid Scoring Protocol for determining wildcats that would be valuable for further conservation breeding based on both a genetic cut-off between wildcat and domestic cat types and their phenotypic (pelage) characteristics (Kitchener et al., 2005). Each genetic score provided an estimate of hybridisation “Q” and a lower boundary and upper boundary for that estimate (LBQ and UBQ). As a general principle, wildcats would be selected for continued conservation breeding when there was a low chance of them being a first-generation backcross based on their genetic scores. This would result in a genetic hybrid score of a minimum LBQ of 75%, or in the worst-case scenario, the equivalent of one of its four grandparents being a domestic cat.

The details of this test and an explanation of its power to detect hybridisation can be found in Senn and Ogden (2015). Pelage scoring used seven pelage characteristics identified by Kitchener et al. (2005) as discriminatory between wildcats and domestic cats and their hybrids. For each of the seven characteristics, the character scale was from one to three, where one is a domestic cat characteristic, two intermediate and three being a wildcat characteristic. This would give a maximum score of 21 for a wildcat based solely on pelage markings, but a lower threshold of 19 was set for identifying wildcats by Kitchener et al. (2005). Both genetic scores and pelage scores were combined in a scoring matrix, which resulted in three possible outcomes; accept into conservation breeding programme, monitor breed (then evaluate offspring) or reject. The scoring matrix can be seen in Tables 1a and 1b.

|

Matrix 1 |

- |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- |

- |

Fail (UBQ<0.75) |

Uncertain (UBQ>0.75 & LBQ<0.75) |

Pass (LBQ>0.75) |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

<16 |

Reject |

Reject |

Monitor* |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

16-18 |

Reject |

? Go to sub-matrix 2 (Table 1b) |

Accept |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

>18 |

Reject |

Accept |

Accept |

|

Sub-matrix 2 |

- |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

- |

- |

Uncertain in Matrix 1 & Q<0.75 |

Uncertain in Matrix 1 & Q≥0.75 |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

16 |

Reject |

? Go to committee |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

17 |

Reject |

Accept |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

18 |

? Go to committee |

Accept |

In order to identify the presence of hybridised individuals within the captive population and remove those that failed the necessary genetic/pelage criteria, a wildcat hybridisation screening project was launched in 2015 for all breeding wildcats registered in the studbook. To ensure consistency in the sample collection process, two separate protocols were developed by RZSS. The first, a Scottish Wildcat Genetic Sampling Protocol (Appendix 1 - Scottish wildcat Genetic sampling protocol, Barclay, 2015a) and the second an RZSS Protocol for Wildcat Pelage Scoring (Appendix 2 - RZSS Protocol for wildcat pelage scoring, Barclay, 2015b).

All collectors were contacted by the RZSS Wildcat Breeding Programme Coordinator and requested to submit a combination of genetic samples and pelage images following the above protocols. It was made clear to wildcat holders that the testing and scoring of these samples would be a requirement for participation in the long-term conservation breeding programme. In situations where people were unable to collect blood samples or pelage images, plucked hair samples that had intact follicles and thus enough DNA for analysis, were accepted as a minimum requirement. In these situations the genetic score would be used alone until further assessments were possible or where offspring (if the outcome was monitor breed) could be subsequently screened.

Samples were sent to RZSS’s WildGenes laboratory, where they were given unique identification numbers (“WCQ” prefix) and recorded on a database. Samples were then processed for DNA extraction and the subsequent wildcat hybrid scoring analysis. All final genetic scores were recorded in the database.

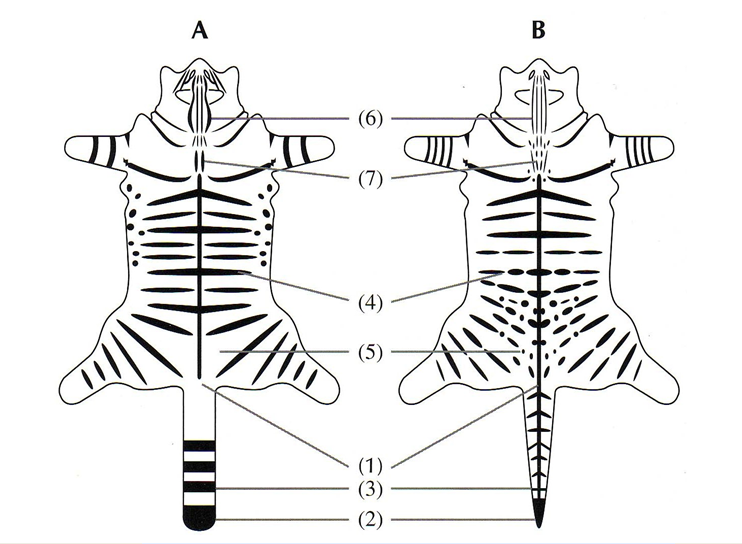

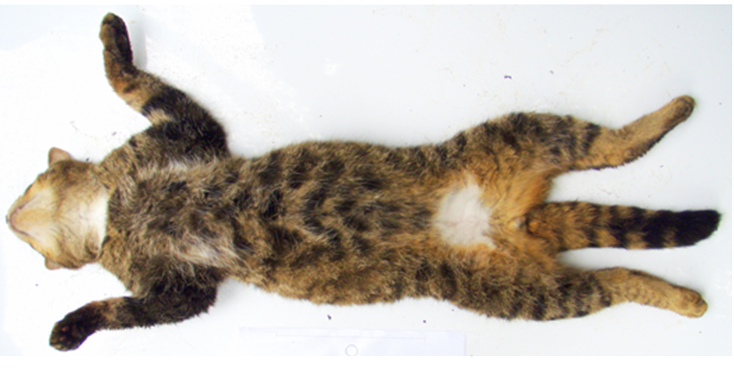

Pelage images were predominately sent to the breeding programme Coordinator and recorded, as per individual holder, in a breeding programme database or, in some situations, sent directly to Dr Andrew Kitchener at National Museums Scotland for independent scoring. Pelage scoring followed the protocol’s seven-point scoring system (7PS) with a maximum score of 21/21, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 2.

A diagram of a wildcat and tabby domestic cat pelage laid flat showing the seven characteristics that can be used to help distinguish between them.

|

No. |

Character |

Score 1 |

Score 2 |

Score 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Extent of dorsal line |

Absent / covers entire tail |

Continues onto tail |

Stops at base of tail |

|

2 |

Shape of tail tip |

Tapered to a point |

Intermediate |

Blunt |

|

3 |

Distinctness of tail bands |

Absent / joined by dorsal line |

Indistinct or fused |

Distinct |

|

4 |

Broken stripes on flanks & hindquarters |

> 50% broken / no marking |

25–50% broken |

< 25% broken |

|

5 |

Spots on flanks & hindquarters |

Many / no marking |

Some |

None |

|

6 |

Stripes on nape |

Thin / no stripes |

Intermediate |

4 thick stripes |

|

7 |

Stripes on shoulder |

Indistinct / no stripes |

Intermediate |

2 thick stripes |

Means of verification for successful delivery of this action was measured by both the recording of samples (including individual genetic scores) in the database (RZSS, 2019b) and in the recording of genetic scores in the Scottish Wildcat Studbook (Barclay, 2019) to support an updated studbook, which in turn supports future breeding recommendations.

2.2 Acquire more wildcat of known genetic status to increase the diversity of the captive population

Wherever possible, zoos and aquariums should strive to have self-sustaining animal populations (EAZA, 2019). However, sustainability can be restricted by several factors, including population size, reproduction, survival rates and the genetic status of the population. When populations are small and relatively closed, they can have a range of genetic problems that can affect overall health and usefulness of the population (Wilcken et al., 2005). Therefore, maximising the genetic health and adaptability of a population requires maintaining as much as possible of the genetic diversity that was present in the wild-born founders of a captive population (Putman and Ivy, 2013).

In order to increase the genetic diversity of the captive wildcat population, and thus increase its overall health, sustainability and value as a conservation tool, RZSS collaborated with a range of conservation stakeholders to source additional wildcats that met the necessary (genetic and pelage) criteria for inclusion in the conservation breeding programme.

At the time of action and implementation (2014), there was a lack of clarity over the accepted taxonomy of wildcats in Scotland. While some considered wildcats in Scotland a separate subspecies, Felis silvestris grampia, many felt there was insufficient evidence that the population in Scotland is a distinct subspecies, but instead viewed it as synonymous with Felis silvestris silvestris from mainland Europe. Without a consensus on taxonomy, the option of importing new genetic stock (founders) from the European captive population was put on hold. Instead we decided to focus on the potential for wild capture of wildcats in Scotland from areas where no other conservation action was in place and where threats were known to exist. As a European Protected Species with full legal protection in Scotland the live-capture, removal, possession and sampling of wildcats (Felis silvestris) is restricted by law. Following a best practice approach and adhering to necessary legal mechanisms, an application to NatureScot’s Species Licensing department was submitted.

Following this application for a Wildcat Animal License, RZSS engaged with several private estates and landowners out-with the SWA Priority Areas (PAs). Through direct communication with gamekeepers and land managers, discussions were held to assess sites for potential wildcat presence, opportunities for camera-trapping surveys, accidental captures, sightings and potential for live capture. RZSS undertook the development of an RZSS SWCAP Trapping Plan (Appendix 3 – SWCAP Trapping Plan 2017, Barclay and Harrower, 2017) to ensure a structured and best practice approach to camera trapping and live capture. The RZSS SWCAP Trapping Plan was based on previous wildcat camera trapping surveys (Kilshaw et al., 2015), SWA TNR (Trap, Neuter, Release) protocols, SWA Guide to Camera Trapping (SWA, 2019) as well as close consultation with veterinary professionals.

In 2017, as another means of adding new (founder) genetic diversity to the conservation breeding programme, RZSS implemented a trial semen collection project. The objective was to trap living known male (suspected) wildcats in the SWA PAs, conduct full health screening, including for diseases, genetic sampling and pelage scoring, and then collect semen samples that could be used for future artificial insemination with captive females. This work followed the RZSS Conservation Breeding Strategy, which identified the long-term approach for the captive population as a support tool for future reintroduction (Barclay, 2017). Working closely with SWA field teams and following the RZSS SWCAP Trapping Plan (Barclay and Harrower, 2017), camera trapping, live trapping and sampling of individuals was conducted in the winter of 2017 across the SWA Northern Strathspey PA.

Means of verification for successful delivery of this action was measured by acquisition of a Wildcat Animal License, a number of meetings with landowners, development of a wildcat sampling and trapping database, inclusion of genetic scores in the RZSS WildGenes Sample Master Database, independent scoring of pelage, addition of suitable wild-caught wildcats in the conservation breeding programme and the addition of suitable wild-caught animals into the Scottish Wildcat Studbook dataset.

2.3 Update the existing wildcat husbandry manual and disseminate to all holders. Standards will be a condition of participation in the captive breeding programme

Good animal husbandry is a prerequisite for good population management (EAZA, 2019). Therefore, it is vital to have a consistent and best practice approach that promotes optimal conditions for animal husbandry, well-being, enclosure design, veterinary care, breeding and animal welfare that accurately reflects the current requirements for any given species. As with other established breeding programmes in the European and international zoo community, this is achieved through the development of species-specific best practice guidelines (formerly known as husbandry guidelines). To ensure guidance is effective and current, it is best practice to review these documents routinely, for example every five years (EAZA, 2019).

Previous management guidance for Felis silvestris was available (Lyons, 1996), but at the time of the SWCAP launch this document was already 17 years old and unlikely to accurately represent current wildcat management practices or recent developments in animal care.

From 2015 to 2016 the RZSS Breeding Programme Coordinator undertook a thorough review of current wildcat management practices, following best practice guidance from the EAZA Population Management Manual (EAZA, 2015a), to compile new Scottish Wildcat Captive Husbandry Guidelines (Barclay et al., 2016).

Means of verification for successful delivery of this action was measured by the publication of the Scottish Wildcat Captive Husbandry Guidelines (Barclay et al., 2016) and its dissemination to all captive holders of wildcats in the UK.

2.4 Captive breeding

The management and development of the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Breeding Programme followed best practice guidance set out by EAZA’s Managing Zoo Populations: Compiling and Analysing Studbook Data (Wilcken et al., 2005) and EAZA’s Population Management Manual (EAZA, 2015a). Software used in the management of the studbook included SPARKS and the PMx. This guidance was also complemented by institutional experience from RZSS over ten years of European and international breeding programme management experience from the RZSS breeding programme coordinator, previous population management training and close consultation with European specialists in animal/population management.

For effective breeding programme management there must be access to good quality data. Without it the pairing of new breeding animals, genetic analysis, long-term planning and sustainability are all significantly restricted. When RZSS took over the management of the studbook (2015), the known pedigree of the population was 7%. In other words, the data available would only allow for complete family histories to be traced for 7% of the population. This was a result of historical acquisitions from unknown sources, poor record keeping, unknown breeding pairs and inaccurate assumptions of relatedness between animals. However, molecular genetic data can be used to determine the identities of animals with unknown ancestry and correct errors in the studbook (Witzenberger and Hochkirch, 2011; Fienieg and Galbusera, 2013). In order to rectify this significant gap in data, RZSS implemented a project focused on reconstructing the pedigree by developing a wildcat molecular studbook. As a relatively new technique for captive population management, there is no one-size-fits-all application, although other examples do exist to help inform the most appropriate approach.

In order to reconstruct the studbook, it was necessary to obtain high-resolution genetic data from all living cats in the captive breeding population. To this end “ddRAD” genomic libraries were prepared for all samples of living wildcats from the captive collection and a number of reference samples (N=129). The methodology of library construction and SNP detection is described in Senn et al., 2019.

Dedicated pedigree reconstruction software Sequoia (Huisman, 2017; Huisman, 2019) was then used on multiple independently selected batches of SNPs from a long list of 11,757 SNPs, to test for stability in pedigree reconstruction. An eventual reconstruction was conducted using a list of 2230 SNPs with a MAF (minimum allele frequency) of >0.02 and a low level of missingness in the 129 animals analysed (the SNPs had 0 or 1 missing datapoints across the 129 individuals). This work was carried out with close collaboration between RZSS WildGenes laboratory and the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Breeding Programme.

Whilst work was underway to develop the molecular studbook, additional activities were undertaken to increase the captive population and the number of captive holders. With the breeding programme showing a clear intention to support long-term conservation measures, including planning for reintroduction, it was important to ensure that this message was visible to the wider zoo community both in the UK and Europe. Also, if the captive population was at some point in the future to be used as a source population for wildcat reintroductions, it would need to be robust enough in numbers to allow for the removal of animals whilst still retaining a level of sustainability. As a tool to encourage increased support from zoos and private holders and thus more space for exhibiting and breeding wildcats, several articles were written for publications in 2015, 2016 and 2019.

RZSS used SPARKS to manage the studbook dataset and record key events and information, such as births, deaths, transfers, parental sex, individual identifiers etc. PMx was used, following the import of SPARKS datasets, to allow population analysis, monitoring of population development and the development of annual breeding and transfer recommendations. Annual reports, detailing the developments in the programme, were also prepared to ensure captive holders were kept informed on all aspects of population management and conservation efforts. Annual meetings were organised to ensure there was the opportunity for face-to-face contact with the coordinator and holders, as well as more detailed presentations on the development of the programme. The breeding programme coordinator also engaged with the wider European zoo community through EAZA, as well as annual attendance and engagement with the EAZA Felid TAG.

Successful delivery of this action was measured by the development and implementation of the molecular studbook, increase in the captive population recorded in SPARKS, increasing the number of captive holders, dissemination of annual breeding and transfer recommendations, publication of wildcat breeding programme articles and improved data quality recorded in the PMx analysis programme.

3. Results

3.1 Assess the genetic status of the captive population

RZSS took over the management of the Scottish Wildcat Studbook (and now conservation breeding programme) in 2015 when the dataset was transferred from the Aspinall Foundation to RZSS Highland Wildlife Park. This event was approved by the EAZA Felid TAG, with RZSS being recorded as the holders on the Felid TAG Member and Advisor Database.

Between 2015 and 2017 genetic samples were collected from all fertile wildcats in the UK captive breeding population and genetically tested using the scoring matrix (Table 3) as detailed in the Wildcat Hybrid Scoring Protocol (Senn and Ogden, 2015). All genetic scores are recorded in the RZSS WildGenes Master Sample Database and in the Scottish Wildcat Studbook (Barclay, 2019). Of the 72 captive cats sampled, two were removed from breeding via sterilisation (for failing the genetic/pelage matrix), six were recorded as monitor breed (for possessing a borderline genetic score and in absence of pelage score) and 64 passed for continued breeding. In addition to genetic assessment, pelage images were also collected and scored independently to RZSS by Dr Andrew Kitchener of National Museums Scotland and recorded in the studbook.

|

Matrix outcome |

% |

|---|---|

|

Pass |

89 |

|

Monitor breed |

8 |

|

Fail |

3 |

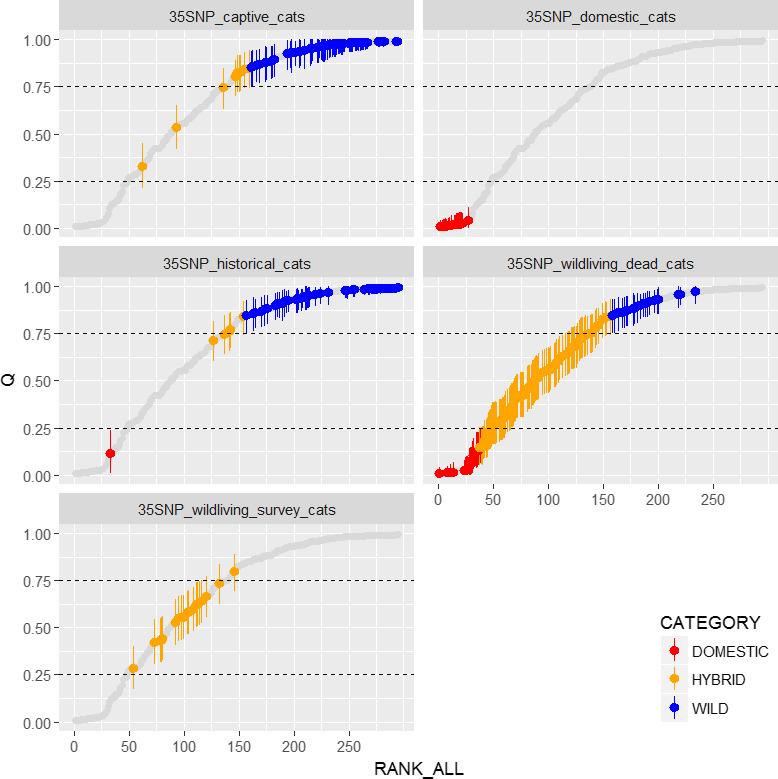

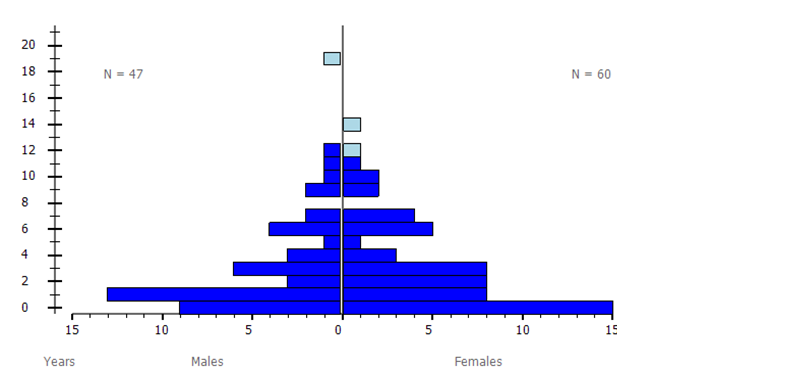

Genetic work conducted at RZSS shows that wild-living cats in Scotland show a hybrid swarm structure, but the historical wildcat population and cats in captivity are at the “wildcat end” of the continuum (Figure 2, Senn and Ogden, 2015, Senn et al., 2019). All cats in captivity have also been analysed via higher resolution genomic “ddRAD” methods, which show highly concordant results with the 35 SNP methodology (Senn et al., 2019). Results from this work have informed the annual breeding recommendations for 2017, 2018 and 2019.

Figure 2. Plot showing the genetic scores of each cat in the captive population (top left panel) against a number of other reference populations. Each point represents a cat and its height on the Y axis represents the portion of genes which are from wildcat as opposed to domestic cat (Q). Blue dots represent wildcats, orange hybrids and red domestics. Full details can be found in Senn et al. (2019). The two lowest scoring cats were excluded from the breeding programme and the other cats in orange (which are borderline) we placed in a “monitor breed category” subject to further future confirmatory testing.

Five plots showing the range of genetic scores (with confidence boundaries) from five datasets. These are captive cats; domestic cats; cats from the historical cats (historical wild-living population); wild-living dead cats (current wild-living population); wild-living survey cats (current wild-living population mainly sampled through live-capture). Most captive cats meet the genetic threshold for wildcats; all cats in the domestic cat dataset meet the genetic definition of domestic cats; most historical cats meet the genetic threshold for wildcats; the wild-living dead cat dataset shows a full range of genetic scores from domestic cat to wildcat; the wild-living survey cats are all hybrids.

3.2 Acquire more wildcats of known genetic status to increase the diversity of the captive population

RZSS received the first wildcat trapping licence in March 2015, which gave the necessary legal provisions for wildcat capture, sampling, possession and, where necessary, inclusion in the breeding programme. To date RZSS has held 22 individual meetings with landowners, land managers or gamekeepers out-with Priority Areas to discuss site assessments for potential wildcat presence and live capture.

RZSS developed a guidance document for site surveys and, where necessary, live capture. This document was finalised as the SWCAP Trapping Plan (Barclay and Harrower, 2017). An RZSS Wildcat Sampling and Trapping Database was also developed to store all critical information, e.g. capture location, sex, pelage score, genetic score, health, measurements, age, etc., on animals that were either acquired by RZSS through accidental trapping or for animals that were specifically trapped by project staff. In 2016 RZSS completed the construction of two large off-show, natural conservation breeding enclosures at RZSS Highland Wildlife Park (Figure 3), as well as three individual wildcat quarantine facilities for temporary holding during screening.

An aerial photograph of two off-show conservation breeding enclosures, showing fencing surrounding areas of juniper scrub habitat with grasses, heather and birch trees.

These enclosures were designed to ensure minimal disturbance, retention of key natural behaviours, and future holding and breeding of wild-caught individuals. To date and following 22 meetings with landowners, 13 potential wildcats (i.e. prominent wildcat features at time of identification) have been genetically screened (including genetic sampling and pelage scoring) by RZSS as part of this action. All animals that have been genetically screened as a result of this action are shown in Table 4.

|

Cat ID |

Genetic ID |

Trap / acquisition date |

Method obtained |

Trap No. |

Behaviour |

Age class |

Sex |

Genetic score Q + 90% confidence interval |

Pelage score (out of 21) |

Wildcat or hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cat (1) |

WCQ0901 |

24/03/2015 |

OP-mink trap |

n/a |

calm |

18-24 months |

female |

44.8 (33.6 - 56.1) |

12 |

hybrid |

|

Cat (2) |

WCQ902 |

27/07/2015 |

OP |

n/a |

calm |

~ 6 weeks |

female |

23.9 (13.1 - 35.6) |

Too young for markings to be scored |

hybrid |

|

Cat (3) |

WCQ903 |

10/09/2015 |

OP (welfare organisation) |

n/a |

calm |

1-2 yrs |

female |

62.6 (50.1 - 74.5) |

13 (2 markings not scored) |

hybrid |

|

Cat (4) |

WCQ904 |

15/09/2015 |

OP |

n/a |

aggressive when trapped |

1-2 yrs |

female |

33.2 (21.9 - 45.1) |

13 |

hybrid |

|

Cat (5) |

WCQ905 |

16/11/2015 |

OP |

n/a |

Calm |

~ 5 months |

female |

29.6 (18.5 - 41.5) |

13 |

hybrid |

|

Cat (6) |

WCQ906 |

09/11/2015 |

OP |

n/a |

Calm |

~ 5 months |

female |

38.3 (26.7 - 50.2) |

n/a - never photographed at vets |

hybrid |

|

Cat (7) |

WCQ907 |

23/11/2015 |

OP |

n/a |

n/a |

2-3 months |

n/a |

20.6 (10.8-31.5) |

n/a - never photographed at vets |

hybrid |

|

Cat (8) |

WCQ908 |

12/01/2016 |

OP |

n/a |

calm |

3-4 months |

female |

62.6 (50.5 - 74) |

16-18 (young cat so pelage un-reliable) |

hybrid |

|

Cat (9) |

WCQ909 |

05/09/2016 |

OP |

n/a |

calm |

3-4 months |

female |

65.1 (53.5 - 76.1) |

14-15 |

hybrid |

|

Cat (10) |

WCQ913 |

13/11/2017 |

TG |

1 |

calm |

6-9 months |

female |

12.1 (3.1 – 22.5) |

11 |

hybrid |

|

Cat (11) |

WCQ0915 |

20/01/2018 |

OP |

n/a |

calm |

1-2 years |

female |

79.9 (69.6 - 88.9) |

17-20 |

wildcat |

|

Cat (12) |

WCQ1185 |

16/01/2019 |

OP |

n/a |

slightly aggressive |

~ 8 months |

male |

24.5 (14.3-35.5) |

10.5 |

hybrid |

|

Cat (13) |

WCQ1227 |

11/03/2019 |

OP |

n/a |

calm |

~ 4-6yr |

male |

70.1 (59.3-80.1) |

18 |

wildcat |

Two of these animals, reported by SWA project officers, were genetically screened by RZSS, but not held on site. Of the remaining 11 potential wildcats, acquired via accidental trapping on estates, opportunistic capture or targeted capture, all were screened, including disease screening, pelage scoring and genetic testing. Of these 11 individuals, only two passed the necessary pelage and genetic criteria (Cat 11 and Cat 13) and have been included in the conservation breeding programme. Both individuals (one male and one female) are currently held by RZSS. The female, trapped in 2018, has successfully bred twice in the RZSS conservation breeding enclosures, with one of her daughters also reproducing and one of her sons siring another litter. Both animals, and their genetic and pelage data, are included in the current Scottish Wildcat Studbook (Barclay, 2019) and are included in current breeding and transfer recommendations for 2019/2020. Furthermore, all genetic scores from these (13) individuals are recorded in the RZSS WildGenes Sample Master Database. In addition to the screening of cats acquired through accidental trapping, opportunistic capture or targeted capture, eight camera-trapping exercises were conducted, yielding five additional images of potential wildcats at five separate locations. This resulted in one live capture, two unsuccessful live captures and two cats for which live capture was deemed unnecessary. Equipment support was also given to three individual estates to support their own wildcat camera-trapping surveys, although this yielded no high pelage-scoring individuals worthy of screening. Four additional public sightings were reviewed for live capture potential; two were of cats inside a PA boundary and two others were not pursued due to low pelage scores.

In 2017, using the SWCAP Trapping Plan (Barclay and Harrower, 2017) and support from SWA field teams, two high-scoring wildcats were identified in the Northern Strathspey PA for a trial semen collection project. Following a two-week camera-trapping and live-capture exercise, both individuals were trapped alive and sampled for disease screening, genetic screening, pelage scoring and semen collection. Both target cats failed the genetic/pelage matrix and as a result semen samples were not stored. A third (non-target) female cat was also trapped during this exercise. Following pelage assessment of the non-target female (17+/21) she was released. Disease screening of one (high-scoring pelage) male trapped for semen collection did, unfortunately, show a positive result for feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and was later re-trapped and euthanised. The genetic, pelage and disease results of these cats are shown in Table 5.

|

Cat ID |

Genetic ID |

Sex |

Pelage score from project officer (based on camera trap image) |

Pelage score during field trial (as per protocol) |

Genetic score (Q) |

Positive disease tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cat 1 |

WCQ0910 |

male |

17/21 |

19-20/21 |

0.620 |

FIV |

|

Cat 2 |

WCQ0911 |

male |

18/21 |

12-16/21 |

0.322 |

none |

|

No ID |

WCQ0912 |

female |

n/a |

17+/21 (when in trap) |

0.236 |

none |

3.3 Update the existing wildcat husbandry manual and disseminate to all holders

New Scottish Wildcat Husbandry Guidelines (Barclay, 2016) were completed and disseminated to all current captive Scottish wildcat holders in November 2016. These guidelines set out recommended standards for enclosure design, husbandry and management and veterinary management for wildcats held in the breeding programme. Captive holder meetings also took place in September 2016, October 2018 and December 2019, allowing further discussion, review and guidance with regards to captive husbandry. These guidelines are distributed to all new or potential collectors wishing to add wildcats to their collection. The guidelines are also available to the wider EAZA community via the EAZA Felid TAG webpage, which is accessible to all EAZA members across Europe. The guidelines have also been shared with several European wildcat holders in the absence of (mainland) European wildcat captive husbandry guidance documents.

3.4 Captive breeding

In 2018 the first wildcat molecular studbook was completed by RZSS, leading to a reconstructed pedigree, based on molecular data and historical studbook data, and giving an increase in known pedigree for the breeding population from 7% to 100%. The molecular studbook estimated there are 26 wildcat founders represented in the breeding programme (Table 6) of which 14 were inferred from historical studbook data, 8 were known founders and 4 were confirmed from molecular data. This data has proved vital in allowing more effective management of the breeding programme and more accurate breeding recommendations. Based on the updated studbook data (including molecular data) and population analysis, annual breeding recommendations were developed and disseminated to all captive holders in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019, detailing the annual transfers of wildcats between holders, as well as new breeding pairs and those animals that should not be bred from in a particular year. In 2018 and 2019 the recommendations were significantly enhanced using the molecular studbook dataset.

|

Activity |

October 2019 |

|---|---|

|

Population |

107 (47.60) |

|

Known pedigree |

100% (reconstructed) |

|

Gene diversity |

89.3% |

|

Founders |

26 |

In 2015, 2016 and 2019 wildcat breeding programme articles were submitted and published in EAZA’s Zooquaria publication (EAZA, 2015b), the Association of British and Irish Wild Animal Keepers (ABWAK) journal Ratel (ABWAK, 2016) and the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums publication BIAZA NEWS (BIAZA, 2019). These articles have played an important role in increasing the awareness of wildcat conservation efforts in Scotland, as well as acting as a call for support from potential new wildcat holders across the UK.

RZSS has hosted annual wildcat holders’ meetings in 2016, 2018 and 2019 and presented on current conservation efforts, field research and breeding programme developments. The breeding programme coordinator has also presented wildcat conservation and breeding programme updates to the EAZA Felid TAG in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 and a wildcat captive breeding for reintroduction presentation to the EAZA Conservation Translocation Working Group (CTWG) in 2015. In 2017 the breeding programme coordinator presented at the first International Small Cat Summit and in 2019 at the ABWAK Small Cat Workshop. In 2016 RZSS also gave a presentation on current wildcat conservation efforts and the role of wildcat conservation breeding for reintroduction to Iberian lynx project staff at breeding centres in Doñana, Spain, and in Silves, Portugal.

Aside from ex-situ-based meetings and conferences, RZSS has presented at several SWA meetings, workshops and forums, ensuring that all wildcat stakeholders in Scotland are well-informed and updated on developments within the breeding programme.

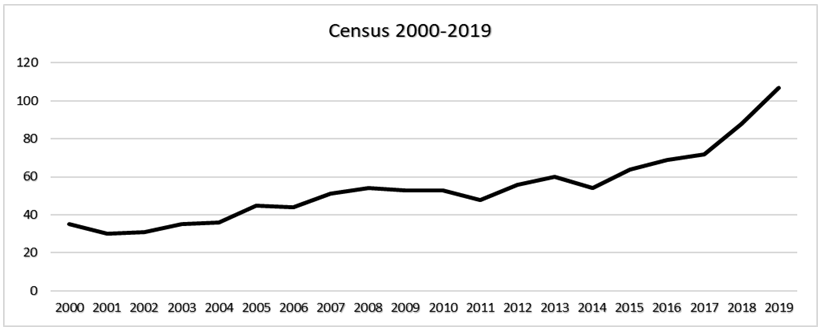

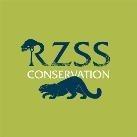

As a result of the communications outlined above and in line with breeding programme best practice guidance (Wilcken et al, 2005) and EAZA’s Population Management Manual (EAZA, 2015), RZSS has been able to significantly develop the captive wildcat population in the UK. This has been evidenced by the updated studbook dataset (Barclay, 2019), using SPARKS, and by data available from PMx (Barclay, 2019). From August 2015 to October 2019 the captive wildcat breeding population in the UK has grown by 67.2%, from 64 (24.40, male.female) to 107 (47.60) individuals (data as of Oct. 2019, Figures 4-5, Table 7), all of which are suitable for further breeding following genetic and pelage assessments (Barclay, 2019).

A line graph showing the increase in the population size of the captive breeding population between 2000 and 2019. A relatively rapid increase is visible from 2017.

A horizontal bar graph showing the age distribution of the breeding population as at 1st Oct 2019, with males to the left and females to the right. The population is dominated by younger age classes under three and the oldest individual is a male at 18 years of age.

The number of wildcat holders (with breeding animals) has grown by 26% from 20 to 27, with 18 having signed management agreements with the programme. Annual average offspring survival between 2015 and 2019 was recorded at 85% and, when comparing the breeding success from year 2015 directly to 2019, there was an increase in birth numbers of 200% (Barclay, 2019).

|

Activity |

August 2015 |

October 2019 |

|---|---|---|

|

Population |

64 (24.40) |

107 (47.60) |

|

Holders (with breeding animals) |

20 |

27 |

|

Known pedigree |

7% |

100% (reconstructed) |

|

Births |

8 (4.4) |

24 (9.15) |

|

Management agreements |

0 |

18 |

|

Additional founders |

0 |

2 |

Since taking over the studbook in 2015, RZSS has put in place the necessary framework for it to function as a well-managed conservation breeding programme that can support conservation projects like that of SWA. Working closely with captive holders across the UK, conservation stakeholders and population management specialists across Europe, RZSS has implemented a range of population management techniques to ensure it has the capability to act as a valuable tool for future wildcat reinforcement.

4. Discussion

Following the implementation of the project actions 3.1.1, 3.1.2, 3.1.3 and 3.1.4, RZSS has been able to successfully deliver a range of outputs that have significantly improved the quality, knowledge, awareness, support and long-term sustainability of the Wildcat Conservation Breeding Programme. Progress of all individual actions should be considered complete and as 100% successful (Table 8). The work, led by RZSS, emphasises the importance of a collaborative approach between all ex-situ stakeholders and the success that can be achieved when delivered effectively.

|

Action no. |

Action name |

Completion rate (%) |

Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

|

3.1.1 |

Assess the genetic status of the current captive population |

100 |

High |

|

3.1.2 |

Acquire more wildcats of known genetic status to increase the diversity of the captive population. |

100 |

High |

|

3.1.3 |

Update the existing wildcat husbandry manual |

100 |

Medium |

|

3.1.4 |

Captive breeding |

100 |

High |

Key elements that played a significant role in the delivery of the above actions can be identified as development and implementation of new genetic techniques, population development via best practice management, increasing gene diversity via acquisition and breeding of founders, and the development of new best practice management guidance. The work highlights the importance of combining shared learning from previous models and the exploration/development of new techniques to enhance conservation breeding programme management.

As a point of reference for the wildcat conservation breeding programme, it is possible to look to other successful models of cat conservation breeding programmes, and when needed, to successful reintroduction projects. To date the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) recovery project in Spain and Portugal is arguably one of the most successful felid conservation projects. Fortunately, there have been several similarities (as evidenced by action outputs in this report) in the approach taken for both Iberian lynxes and wildcats. Molecular work, effective population management, breeding of wild-caught animals, engagement with the wider European zoo community, close collaboration with field and research teams, integrated approaches between ex-situ and in-situ stakeholders, and publication of best practice guidance to ensure long-term replicability, have all been core elements in both projects. It goes without saying that wildcat conservation breeding for reintroduction efforts are far behind those for the Iberian lynx, following years of successful reintroductions, but with an effective framework in place, wildcat recovery across Scotland has the potential to mirror some of the successes already seen with the Iberian lynx.

Despite the successes of the project, there were some challenges. It is widely recognised that the wild-living cat population has, regardless of conservation efforts, continued to decline during the past five years. This, combined with extensive levels of hybridisation, meant that the identification and sourcing of valuable wildcats (genetically and phenotypically) for inclusion in the conservation breeding programme was incredibly difficult. In addition to this, many cats that were monitored during the project and subsequently sampled (albeit latterly) were identified as having high (17+) phenotypic characteristics, but low genetic scores (LBQ<75%). This highlights the need for quicker assessments (genetic and pelage) in the future to ensure that resources are not wasted with non-target animals. This should also be considered for future conservation and or recovery efforts, especially in relation to release site assessments. Areas assessed for future release should have low levels of hybrid cats and a source (i.e. local domestic cats and feral cats) that with suitable resources can be controlled, thus clearing the way for reinforcement or reintroductions.

Obtaining genetic samples from entire captive populations is a rare event in the zoo community. This is often due to restrictions or challenges relating to institutional protocols, CITES (Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species) permits, sample transport, institutional support and/or individual veterinary restrictions. Although RZSS achieved this, albeit with just a UK population, it still took around two years to acquire all the samples. Using this project as a model for other small cat or small carnivore programmes, a recommendation would be to collect genetic samples (blood and hair) from all individuals at any opportunity, be it routine health screenings, restraints, transfers, veterinary treatments etc. This recommendation complements the EAZA Biobank Strategy, which aims to preserve captive samples as a primary resource for genetically supporting population management and conservation research, as well as to connect researchers to available samples. RZSS currently recommends that, as a minimum, all captive wildcat holders collect hair samples from all animals that are available for long-term genetic monitoring.

The current status of the captive wildcat population has improved significantly by the actions detailed in this report. Continuation of these results should be a priority for future wildcat conservation efforts and additional resources and investment should be allocated to develop them further.

5. Conclusion

Wildcats have been held in UK captive collections for at least 45 years. However, it is highly unlikely that in the early 1970s researchers were exhibiting the species with the intention that they could be a potential resource for future recovery. Despite the reasons behind the historical management of captive wildcats, the work delivered by RZSS reiterates that, with effective population management practices, conservation breeding programmes are a valuable resource that can actively support current conservation efforts. Further support for using conservation breeding programmes to support wildcat recovery was documented in the 2019 status review conducted by the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group chairs (Breitenmoser et al., 2019). The Scottish Wildcat Conservation Breeding Programme continues as a well-managed programme that supports an integrated approach to wildcat conservation. With the continued decline of wild-living wildcats in Scotland over the last five years, there is the possibility that long-term conservation actions will be significantly influenced, if not reliant, on the availability of captive stock for reinforcement or reintroductions.

The evidence available to date, regarding the wild-living wildcat population, indicates that the wildcat in Scotland is on the verge of extinction and can no longer be considered viable (Breitenmoser et al., 2019). Breitenmoser et al. (2019) emphasise the need for a step change in conservation planning, stating;

“The recovery will only be possible with the support of reintroduction/reinforcement projects”

To address these recommendations and as a means of continuing and bolstering the conservation breeding programme actions from SWA, RZSS (in collaboration with NatureScot, Forestry and Land Scotland, Cairngorms National Park Authority, Nordens Ark [Sweden] and the coordinating partner of the Iberian lynx recovery project Junta De Andalucía [Spain]) have launched a second-phase project focused on wildcat population reinforcement. Benefiting from the significant SWA legacy, the project will put a robust platform in place for the long-term recovery of this iconic threatened species.

6. References

ABWAK. 2016. Ratel: Journal of the Association of British and Irish Wild Animal Keepers. Vol. 4. No. 2. June 2016.

Anonymous, 1987. IUCN Policy Statement on Captive Breeding. SSC Captive Breeding Specialist Group.

Barclay, D. Williams, R. Girling, S. Richardson, D. Neff, A. 2016. Scottish Wildcat Captive Husbandry Guidelines. RZSS

Barclay, D. 2015a. RZSS Genetic Sampling Protocol. Unpublished, RZSS.

Barclay, D. 2015b. RZSS Protocol for Wildcat Pelage Scoring. Unpublished, RZSS.

Barclay, D. 2019. Scottish Wildcat Studbook, SPARKS v1.6.

Barclay, D. Harrower, B. 2017. RZSS SWCAP Trapping Plan. Unpublished, RZSS.

BIAZA. 2019. BIAZA NEWS. The Magazine for Britain and Ireland’s best zoos and aquariums. Issue 23. Summer 2019.

Bourgeois, S., Senn, H., Kaden, J., Taggart, J. B., Ogden, R., Jeffery, K. J., McEwing, R. 2018. Single‐nucleotide polymorphism discovery and panel characterisation in the African forest elephant. Ecology and Evolution, 8(4), 2207–2217. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3854

Breitenmoser, U. Breitenmoser-Wursten, Ch. Carbyn, L.N and Funk, S.M. 2001. Assessment of carnivore reintroduction. In: J.L. Gittleman, S.M Funk, D. Macdonald and R.K. Wayne. Carnivore Conservation – Conservation Biology 5, Cambridge Press, Cambridge. Pages 241-281

Breitenmoser, U. Breitenmoser-Wursten, Ch. Lanz, T. 2019. Conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the conservation status and assessment of conservation activities.

Conde DA, Colchero F, Gusset M, Pearce-Kelly P, Byers O, Flesness N, et al. 2013. Zoos through the lens of the IUCN Red List: A Global Metapopulation Approach to Support Conservation Breeding Programs. PLoS ONE 8(12): e80311. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080311

EAZA. 2015a. EAZA Population Management Manual. EAZA.

EAZA. 2015b. Zooquaria. Quarterly publication of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. Issue 91. EAZA.

EAZA. 2019. EAZA Population Management Manual: Standards, procedures and guidelines for population management within EAZA. EAZA.

Fienieg, E. Galbusera, P. 2013. The Use and Integration of Molecular DNA Information in Conservation Breeding Programmes: A Review. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research. 1(2). 2013.

Fischer, J., and D. B. Lindenmayer. 2000. An assessment of the published results of 22 animal relocations. Biological Conservation 96:1–11.

Frankham, R. 2008. Genetic adaptation to captivity. Molecular Ecology 17:325–333.

Griffith, B., J. M. Scott, J. W. Carpenter, and C. Reed. 1989. Translocations as a species conservation tool: status and strategy. Science 245:477–480.

Huisman, J. 2017. Pedigree reconstruction from SNP data: parentage assignment, sibship clustering and beyond. Molecular Ecology Resources. 17, 1009-1024.

Huisman, J. 2019. Sequoia: Reconstruction of multi-generational pedigrees from SNP data.

Jone, K. 2015. RZSS Animal License. Species Licensing, Scottish Natural Heritage. Unpublished.

Kilshaw K., Johnson P. J., Kitchener A. C. and MacDonald D. W. 2015. Detecting the elusive Scottish wildcat Felis silvestris silvestris using camera trapping. Oryx 49(2), 207–215.

Kitchener A. C., Yamaguchi N., Ward J. M. and MacDonald D. W. 2005. A diagnosis for the Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris): a tool for conservation action for a critically endangered felid. Animal Conservation 8, 223–237.

Kitchener A. C., Breitenmoser-Würsten Ch., Eizirik E., Gentry A., Werdelin L., Wilting A., Yamaguchi N., Abramov A. V., Christiansen P., Driscoll C., Duckworth J. W., Johnson W., Luo S.-J., Meijaard E., O’Donoghue P., Sanderson J., Seymour K., Bruford M., Groves C., Hoffmann M., Nowell K., Timmons Z. and Tobe S. 2017. A revised taxonomy of the Felidae. The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. Cat News Special Issue 11, 80 pp.

Leus, K. 2011. Captive breeding and conservation, Zoology in the Middle East, 54:sup3, 151-158, DOI: 10.1080/09397140.2011.10648906

Lyons, J. 1996. Management Guidelines for The Welfare of Zoo Animals. Wildcat (Felis silvestris). Edinburgh Zoo. The Federation of Zoological Gardens of Greta Britain and Ireland. 1st Edition. ISSN: 0963-1712.

Simón Mata M.A., 2018. CENSO DE LAS POBLACIONES DE LINCE IBÉRICO AÑO 2018. Life+IBERLINCE, Recuperación de la distribución histórica del Lince ibérico (Lynx pardinus) en España y Portugal. (LIFE10NAT/ES/570)

Macdonald D. W., Daniels M. J., Driscoll C., Kitchener A. and Yamaguchi N. 2004. The Scottish wildcat: analyses for conservation and an action plan. Executive summary. 1–6 pp.

Peterson, B. K., Weber, J.N., Kay, E.H., Fisher, H.S., and Hoekstra, H.E. 2012. Double digest RADseq: An inexpensive method for denovo SNP discovery and genotyping in model and non‐model species. PloS One, 7(5), e37135.

Putman, a. Ivy, J. 2013. Kinship-Based Management Strategies for Captive Breeding Programs When Pedigrees Are Unknown or Uncertain. Journal of Heredity. 2014:105(3):303-311

SWA. 2019. Guide to Camera Trapping: Scottish Wildcats.

Senn H. V. and Ogden R. 2015. Wildcat hybrid scoring for conservation breeding under the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan 2015. Royal Zoological Society of Scotland,

Senn, H. Ghazali, M. Kade, J. Barclay, D. Harrower, B. Campbell, R. Macdonald, D.W. Kitchener, A. 2018. Distinguishing the victim from the threat: SNP-based methods reveal the extent of introgressive hybridisation between wildcats and domestic cats in Scotland and inform future in-situ and ex-situ management options for species restoration. Evolutionary Applications. 2018; 1-16.

SNH (Scottish Natural Heritage) 2013. Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan. 12 pp.

Wilcken, J. Lees, C. Christie, S. 2005. Managing Zoo Populations: Compiling and analysing studbook data. 1st Edition. EAZA.

Witzenberger K.A., Hochkirch A. (2011) Ex situ conservation genetics: a review of molecular studies on the genetic consequences of captive breeding programmes for endangered animal species. Biodiversity and Conservation 20: 1843–1861.

Wolf, C. M., B. Griffith, C. Reed, and S. A. Temple. 1996. Avian and mammalian translocations: Update and reanalysis of 1987 survey data. Conservation Biology 10:1142–1154.

Wolf, C. M., T. Garland, and B. Griffith. 1998. Predictors of avian and mammalian translocation success: reanalysis with phylogenetically independent contrasts. Biological Conservation 86:243–2

7. Annexes

7.1 Appendix 1: Scottish wildcat genetic sampling protocol

Please follow the guidance below for blood sampling of wildcats which will be used to identify genetic status of individual cats and to inform captive breeding recommendations.

Protocols for such samples include the collection of 1-2ml of whole blood into EDTA tubes (purple) by a qualified veterinary surgeon. It is requested that sample tubes are inverted ~ x15 to prevent clotting (as clotted blood yields poor DNA). Each tube should be labelled with

- House name

- Local ID number (where appropriate)

- EAZA studbook number (where appropriate)

- Sex

- Institution

- Date of sampling

Such samples should be posted first class, with each tube double bagged in individual zip lock bags (this ensures that blood can still be recovered if the tubes are damaged), and all tubes placed within one larger bag. PAD WELL. Send email to [email protected] and [email protected] to say that you are posting samples. Post 1st class to:

Wildgenes,

RZSS,

134 Corstorphine Road,

Edinburgh

EH12 6TS

Please remember to include contact details with the parcel so we know who it came from.

7.2 Annex 2 - RZSS Protocol for wildcat pelage scoring

To ensure accurate and consistent assessment of wildcat, or suspected wildcat, pelage (coat markings) a reliable photographic record must be collected.

Below is a guide to the key images that should be taken at as high a resolution as possible, e.g. at least 2-3Mb file images.

Top tips:

- if possible photograph the cat against a white or pale standard background - if the fur is wet or ruffled, try to dry it using paper towels and smooth the fur flat - include the label on as many of the record photos as possible - if a dead cat is collected for later examination, put label in a small plastic bag inside the bag with the cat.

Essential images:

ID Label:

(Location and/or grid reference, date, collector name, studbook details (where relevant) and contact details (obscured below):

Please send your images to both:

Dr Andrew Kitchener, Principal Curator of Vertebrates, National Museums Scotland

[email protected]

David Barclay, Cat Conservation Project Officer, RZSS

[email protected]

7.3 Annex 3 - SWCAP Trapping Plan 2017

SWCAP Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris) camera and live trapping plan

Background

Working as part of the Scottish Wildcat Action plan, RZSS staff will conduct monitoring surveys to assess key sites across Scotland for the presence of wildcats. This work aims to highlight key locations where wildcat presence has been identified and where targeted live trapping can take place, with a view of acquiring wild caught individuals for the RZSS conservation breeding programme. Under the RZSS Animal license (93984) issued by SNH, valid to 31st Dec 2020 RZSS are permitted to undertake live capture and sampling of wild living wildcats as well as the captive breeding of any wildcats that pass a genetic and pelage scoring assessment.

Detect wildcat presence using camera trapping surveys to allow for targeted wildcat live capture.

Survey site agreements

Prior to any surveys taking place, signed agreements will be put in place between RZSS and the survey location landowner. Once an agreement has been signed (following the RZSS “Landowner and Manager trapping agreement”) and survey dates agreed between RZSS wildcat agents and the landowner/land manager; surveys can commence.

Camera trapping methodology

As documented in camera trapping publications (Ancrenaz et al, 2012) there is no defined model for assessing species presence and surveys that attempt to do so often suffer from a high risk of missing the target species, especially if they are rare. The methodologies for the purpose of this plan need to remain flexible due to the need to assess presence only and not other factors such as population size or density. This is to cater for new information, limited resources and the wide variety of factors affecting potential survey locations, i.e. useable habitat, prey availability and landowner permission.

Previous wildcat methodologies, Kilshaw & Macdonald (2011), Hetherington & Campbell (2012), have shown success in determining presence of wildcats using two cameras per location with spacing ranging from 0.5 – 1.5 km2 within 4 x 5 km2 grids over a 60-day survey period. It was also found from one of these surveys (Hetherington & Campbell 2012), using two camera traps per location, that a survey period of 21 days captured images of around 50% of the individual cats caught on camera over a longer, 60 day, survey period. As stated in the “Handbook for wildlife monitoring using cameras” (Ancrenaz et al, 2012) surveys aiming to detect distribution and occupancy require a minimum of 10 cameras to be used, (20 if species are rare and difficult to detect) placed in grids pre-determined by habitat variety. For very rare species the recommendation suggests two cameras per camera location are used. When using a grid system for distribution and occupancy Ancrenaz et al (2012) states that there is no need to sample all grids but the total should be representative of study area.

Taking into account the previous methodologies from wildcat surveys and additional recommended survey techniques that highlight the difficulties of presence/absence surveys we will use a combination of two methodologies to ensure a robust approach towards locating wildcats. The primary methodology will be a structured survey using a grid system (dependent on size of study area) based on Ordnance Survey tiles. In addition to this we will also allow for a more targeted survey which can be used for key wildcat sites anywhere there is accurate and recent information to suggest wildcat presence. These intensive, targeted surveys will be used for live capture, sampling and semen collection.

Structured survey methodology

As a rule, the structured survey methodology will follow the two area criteria below:

Areas > 5km2 (500 hectares), cameras will be placed using OS squares at a density equating to one camera per 2km2.

Areas < 5km2 (500 hectares), cameras will be placed using OS squares at a density equating to one camera per 1km2.

All cameras will be set to capture still images as opposed to video capture given the 30 day duration of cameras being set.

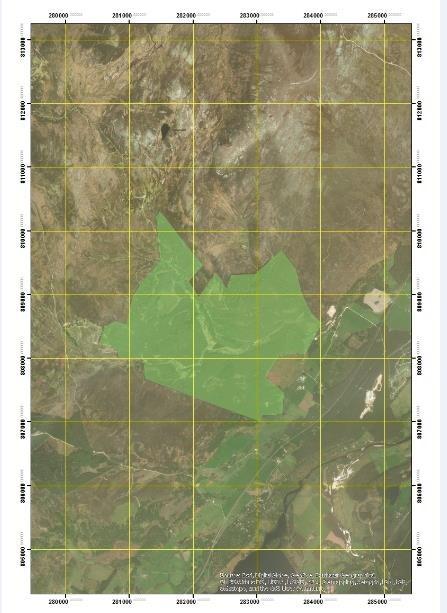

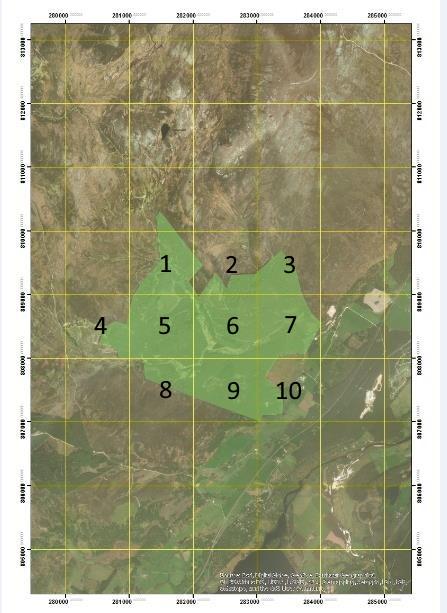

Using Geographical information system (GIS) and the 10km x 10km tile system (Figure 1), survey sites will be labelled following this reference system. For example, “Survey 1 – Name of estate NH80 or Survey 1 – Name of estate NH80/NH81”.

After survey sites have been identified (Figure 2) using the 10km x 10km identification reference a more detailed 1km x 1km tile system will be applied to the survey site using GIS, shown on the right, to pin point preferred survey location, camera location and preferred habitats.

This 1km2 x 1km2 grid system will be used in conjunction with “suitable” & “unsuitable” habitat where tiles containing unsuitable habitat, Kilshaw et al (2015), will be eliminated from camera locations.

- Suitable habitat – woodland (coniferous, broadleaved / mix woodland), scrub and pasture/grassland

- Unsuitable habitat – arable, urban/suburban, heather moorland, bog and montane. (Kilshaw, et al., 2015)

Only numbered tiles (containing suitable habitat), as shown on the left, will be used as camera locations with exact locations of the cameras flexible to within 100 – 200m of the tile center, taking into account preferable wildcat habitat features, shown below.

- Wildcat habitat features – small animal trails, cat faeces, potential den sites, cat paw prints, holes in animal fencing, natural funnels (walls, fence lines)

Despite previous surveys often using two cameras per camera location, the structured survey methodology will only use one per location in order to maximize coverage and available resources. Given the need for quick data collection and to enable live trapping should wildcats be found, a survey duration of 30 days will be used. Taking into account the camera trapping survey in 2012 (Hetherington & Campbell) where 50% of cat images were captured within the first 21 days of a longer 60-day survey (using two cameras per location) this survey aims to capture a minimum of 50% of cats in any given area. All cameras used will be baited using rabbit, pheasant or quail to maximize capture probability. All cameras will be set to image mode.

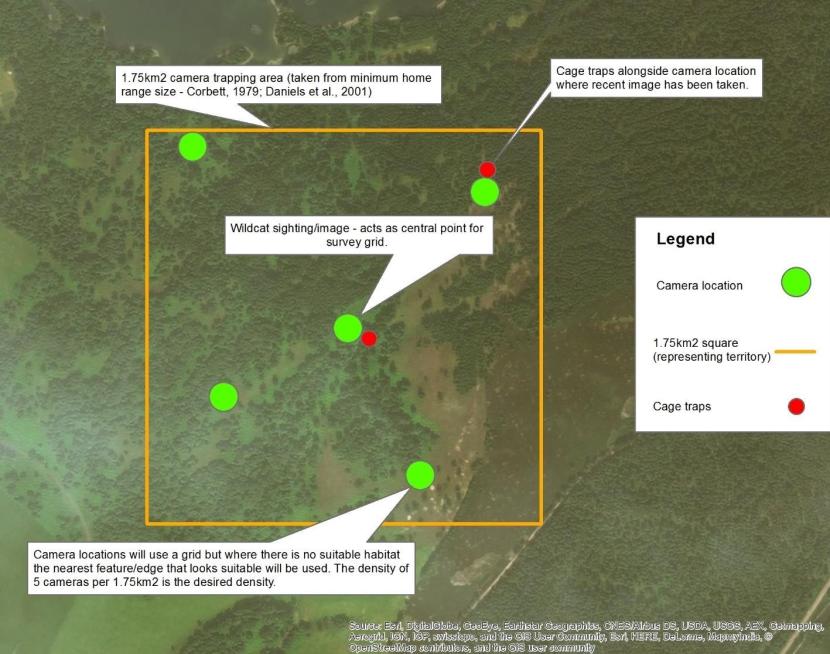

Targeted survey methodology

The targeted methodology will be used when reliable and new information is provided on wildcat sightings providing RZSS can operate within that area and an agreement with the landowner is in place. After acquiring the exact location of the sighting, image or evidence of wildcat presence, cameras will be set up around wildcat habitat features at a density of five cameras per 1.75km2 with the exact location as the central point (where possible) as shown below, based on the minimum home range of female Scottish wildcats (Corbett, 1979; Daniels et al., 2001). In instances where the sighting is on the edge of suitable habitat, the box may be adjusted to encompass the most suitable nearby habitat whilst retaining the sighting location with the 1.75km2. In particular situations where an area cannot be covered by a square the ebullient size of a minimum territory may be represented in other shapes.

Cameras used during targeted surveys, at the five cameras per 1.75km2 density, will be baited using rabbit, pheasant or quail, and checked / re-baited once per week until footage is collected confirming wildcat presence. For targeted surveys all cameras will be set to video mode (15 second clips) for greater accuracy in cat identification. Once wildcat presence is confirmed live capture can commence.

Live trapping methodology

Following the confirmation of wildcat presence and agreement by all involved, cage traps will be set to conduct live capture. Live cage traps will only be set and monitored by RZSS wildcat agents signed on to the current RZSS/SNH Animal license and in full accordance with accompanying health and safety guidelines/risk assessments.

Prior to activation cage traps may be setup, baited and securely tied open to help habituate target cats to them prior to trap activation. Cage traps will be active for one week periods at any one time with further activation being reviewed following the first week. Traps will be baited with rabbit, pheasant, quail or chicken meat and re-baited weekly should efforts continue for more than a week.

Traps will be covered using either waterproof sheeting or wooden boards and disguised using nearby vegetation to ensure any animal captured is sheltered from the elements. Cage traps when active will be paired with a GPRS camera (allowing remote email access to images) and a standard camera trap (to monitor nearby activity). The GPRS cameras will be set to automatically send images via email every four hours (six times per day) that will provide evidence of the trap being triggered or not. This method will reduce the amount of staff time needed to physically visually check cage traps whilst reducing human scent and disturbance around trapping locations. In the event where no images are received within a 12hr period of the trap being active RZSS staff / wildcat agents will go and check the trap visually. A timetable will be used to ensure that there is at least one member of the RZSS Wildcat agent team providing cover whilst the traps are set. If there is any doubt over availability i.e., during a weekend, then the traps will be de-activated.