NatureScot Science Quarterly Newsletter - Issue 37 - November 2021

Welcome from the SAC Chair

Pete Higgins

I write this as I head for COP26 in Glasgow. I do so with the genuine trepidation many of us feel, as we hope that by the time we reach November 12th (or possibly the early hours of November 13th) we will have committed to a significant course of action to combat the climate and associated biodiversity emergencies. The headline banner states: ‘The COP26 summit will bring parties together to accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.’ I earnestly hope that the commitments we need are agreed, and actions are 'accelerated'.

My colleagues and I have various commitments at the COP, mostly around sustainability and environmental education. However, we are well aware that whatever the outcomes, the conference is just one (albeit vital) event in a journey. In advance, we have spent much time over the past year developing and now running two MOOCs (massive open online courses), supported by the British Council. One of these is 'Live at the COP', and in mid-November we are hosting a UN University ‘global' on-line conference on sustainability education. I am sure that many of you reading this will also be looking over the COP26 horizon to COP15 in China and beyond, and working to make your own contributions to the process - through science, advocacy and a range of other work.

I am delighted that several colleagues from NatureScot will be present in the UN-controlled ‘Blue Zone’ - chairing, presenting, and perhaps most importantly exhorting and encouraging COP delegates to do the right thing, and specifically to consider the significance of the natural world in stabilising our climate, and the dire impacts on nature of global heating.

To support their work, and other NatureScot staff, we have crafted briefing lines, and the top three are:

- All life on earth – plants and animals including humans – is interconnected. Humanity is a part of nature and we must support nature in order to support humanity.

- The twin crises of climate change and nature loss are intertwined and must be tackled together. We need nature to lessen the effects of climate change and nature needs us to manage climate change to avoid its collapse.

- The science is clear, that we may be approaching a tipping point for nature and for the climate, but it is not too late to act and to take positive actions for nature and the natural world.

And that brings me to the science, for it is at the heart of the underpinning of our understanding of what is happening, and what needs to be done. Along with the science, it is equally important and urgent that we effectively communicate both the dire consequences of inaction, and the enormous benefits of positive commitments and action. I wish everyone committed to this endeavour, whatever the contributions, the utmost success.

And regarding ‘endeavour’, let me congratulate some colleagues: Jeanette Hall and David O’Brien on being elected Fellows of the Linnaean Society; David for passing his PhD viva in the same week he learnt of becoming a FLS; and Colin Bean on being elected a Fellow of the Freshwater Biological Association. These are special distinctions. I was also very pleased to see the appointment of the University of Edinburgh’s Professor Mathew Williams as Chief Scientific Adviser for Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture. Mathew is expert in studying interactions between terrestrial ecosystems and climate systems, disturbance and management. You can be sure we will be working with Mathew - and indeed many of you dipping into our newsletter.

Enjoy the great selection of our science work here.

Estimating bog breathing using interferometric satellite radar (InSAR)

Stephen Varwell and Henk Pieter Sterk

A new report published in July, looks at the use of satellite technology to monitor how bogs ‘breath’ and whether this method can be used to estimate peatland condition and assess restoration progress across Scottish bogs.

Seasonal changes in surface - uplift and subsidence due to (but not limited to) changes in soil moisture conditions and water level – have been measured in the field with various techniques in the past, and accepted as a good indicator of peatland condition.

In the report (Report 1269), the team has used InSAR to actually measure these peatland surface motion rates, granting us the ability to see how several key Scottish peatland sites ‘behave’ over time.

From the InSAR, surface motion characteristics were obtained. Combining these characteristics from the long-term trends enabled the authors to formulate classes that could be linked to peatland condition. These classes ranged from degraded peatlands, with negative trends and no seasonal timings, all the way to highly fluctuating peat surface levels that have a net ‘growth’ trend, which are generally associated with near natural, Sphagnum dominated vegetation cover. Intermediate classes, such as peatland margins and rewetted (restored) peatlands were also manually assigned.

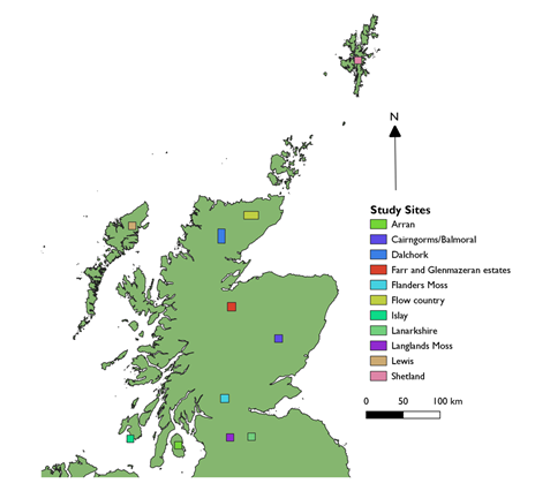

A total of 11 focus sites were used to test the methods and link known peatland condition and restoration histories with the InSAR patterns.

Overview map showing the 11 project focus sites:

Arran

Cairngorms/Balmoral

Dalchork

Farr and Glenmazeran estates

Flanders Moss

Flow Country

Islay

Lanarkshire

Langlands Moss

Lewis

Shetland

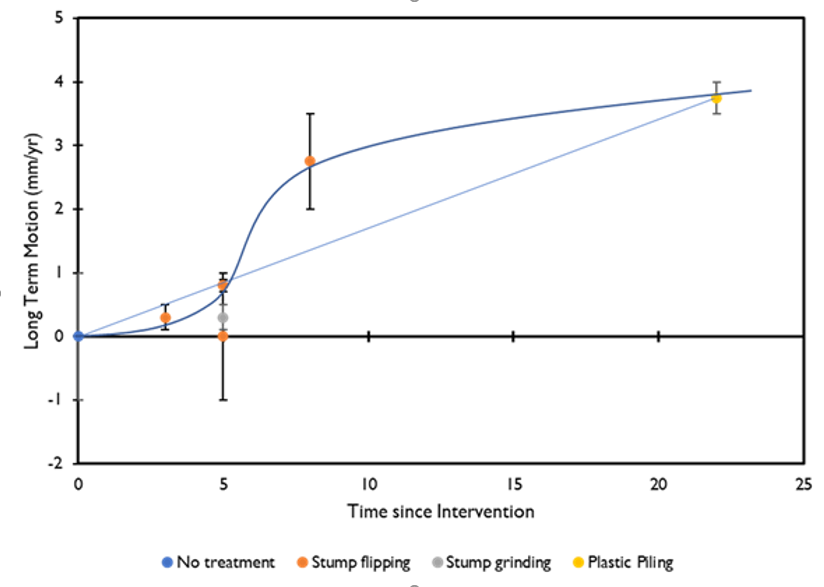

One of the major outcomes of the report includes a first link between long-term peatland surface motion across various restoration intervention timings - in this case at Flanders Moss.

To look at this in more detail, the team has examined different types of interventions over time. The graph below shows the time since intervention (different techniques were applied 22, 8, 5 and 3 years prior to the data collection) plotted against the long term motion (standardized against the areas where no treatment was applied). The main observation from this result that is interesting for future monitoring guidelines, is that it can take well over 5 years before any effect on the peatland surface motion characteristics can be observed. For Flanders Moss, this was the case with stump flipping interventions that show a large jump in overall surface motion after 5 to 8 years.

Graph showing peatland surface motion plotted against time since intervention.

Of course, Flanders Moss is only one of the 11 sites mentioned in the report, and a lot of the results are very site specific. However, the outcomes provide an exciting insight into what the future might bring for Peatland Action and NatureScot in general, as these kind of remote sensing platforms have the possibility to assist in our monitoring and assessment techniques. The report lists numerous potential future applications, ranging from carbon accounting and fire risk assessments, to using the technique across other soil types and in combination with other remote sensing (and field-based) methods.

The next step for Peatland Action team is to scope out the possibilities of this data for our restoration and monitoring applications across the Scottish peatlands, but also to inform partners across the (scientific) peatland community about potential collaborations and upscaling steps in the future.

Initial findings from the Learning in Local Greenspace Project

Sue Munro

Learning in Local Greenspace was a project emanating from Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 2020. This collaborative project was led by NatureScot but involved many partners over the course of its life from 2015-2020. The aim of the project was to support teachers to take learning out into a local greenspace over a sustained period of time in order to embed outdoor learning at the schools. The target was to work with 100 schools in the 20% most disadvantaged areas across Scotland have access to quality greenspace for outdoor learning. Over the course of the project we worked with 115 schools (94 primary, 16 secondary and 5 additional support needs schools) across 12 local authorities.

The final year of the project was seriously affected by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. This not only reduced the support that we and our partners could give to schools, but also impacted the evaluation of the project. Our evaluation was a simple one – to ask a short set of questions of as many teachers from the participating schools at the beginning and the end of the project as possible and analyse the difference. To supplement this we also commissioned an external consultant to interview our partners and a sample of teachers from the schools. Despite the impact Covid-19 has had on this project it is pleasing to see there are many positive trends coming through the data:

- The percentage of teachers feeling fairly or very confidence has improved by 31% (baseline 54%, post-project 85%)

- The percentage of teachers taking learning outdoors in their local greenspace on a fairly regular/very regular basis has risen by 21% (baseline 28%, post-project 49%)

- The percentage of teachers taking learning outdoors in school grounds on a fairly regular/very regular basis has risen by 31% (baseline 53%, post-project 84%)

- The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils’ connection to nature is good or excellent has risen by 18% (baseline 19%, post-project 37%)

- The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils engagement in learning outdoors is good or excellent has risen by 23% (baseline 56%, post-project 79%)

In addition to the data gathered, our partners provided us with a useful array of qualitative material. Some of the most powerful material have been quotes from the participants in the project. Here are just a few of the many we have gathered:

I don’t feel as stressed when I am out but when I am in class I get stressed. (Primary school pupil, West Dunbartonshire)

I felt engaged with the wildlife. (Secondary school pupil, Glasgow)

I used to think the woods were scary but now I enjoy them. (Primary school pupil, South Lanarkshire)

Outdoor learning is essential for learning and raising the attainment in our area. The children love investigating and exploring outdoors though we could do with a more inviting area for outdoor learning to enhance their experience. (Primary school teacher, South Ayrshire)

Over the autumn we will finish analysing all the quantitative and qualitative data we have gathered and write up a final report on the project. We will use the findings from this report to develop our future support for outdoor learning to help spread the multiple benefits of learning in local greenspace to other schools across Scotland.

Scottish Invasive Species Initiative – Monitoring invasive plant control

Vicky Hilton

Over the last four years here at the Scottish Invasive Species Initiative we’ve been working to control key riparian invasive species (Giant hogweed, Japanese knotweed, Himalayan balsam and the American mink) across one third of Scotland. The aim of the project is to embed this control work at a community level ensuring sustainability and a legacy to the project

In addition to the public-facing volunteering and education work we’ve been doing, behind the scenes there is also work being undertaken to assess the impact of our control works. Within the plant treatment sections on each river we monitor several spots annually using plant abundance surveys and fixed-point photography. Invasive plants are renowned for their stubbornness and require several years of repeat treatments to deplete rhizomes or persistent seed banks, so monitoring is essential to record progress and success. We are now starting to share some examples of our experiences, treatment schedules and results as a series of Site Studies.

Showing 2019 picture of before and 2021 picture after knotweed clearance

In the first site study – Japanese knotweed at Dunkeld Bridge on the River Tay – multiple treatments were carried out in the first year by a group of partners which resulted in a significant reduction in the abundance of Japanese knotweed - limited to small, stressed regrowth by year three. This suggests the rhizomes have significantly depleted energy reserves and that the regime of control works was successful. This was further evidenced by the much-reduced level of control work required each year - the volume of pesticide used on the site decreased by 97% and the hours of control work required reduced by 93% (from 2019 to 2021). This site is now under control and the required future control works are now minimal.

We hope that by sharing examples such as this showing that with partnership working and a successful control schedule invasive plant management need not be demoralising and seem like a thankless task, especially for community groups and land managers. We hope these site studies will be exemplars of the resource and effort needed and provide inspiration that good results can be achieved within two or three years (depending on the species).

The Dunkeld Bridge Site Study can be read on the website. Further site studies will be added to the Case Studies webpage later this year.

Contact the team – [email protected]

Tracking the Bean Geese of Central Scotland

Michael Thornton

The Taiga Bean Goose is one of Scotland’s rarest migratory birds, with only one small population, amounting to less than 300 birds, wintering on the Slamannan Plateau in central Scotland. It remains one of the few declining goose species in Europe, with an estimated population of 100,000 in the mid-1990s, declining to 63,000 in 2009. It is on the IUCN Red List of Threatened species, breeding in Scandinavia and western Russia, and wintering mainly in southern Sweden, Denmark and, to a lesser extent, in northern Germany and Poland. Small numbers also winter in western Denmark, the Netherlands and Britain. The loss, fragmentation and degradation of suitable habitat to forestry and infrastructural development is considered to be one of the principal threats affecting this species. An international Action Plan provides details for the conservation of Taiga Bean Geese.

In 2006, NatureScot designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) to safeguard the population on its wintering quarters on the Slamannan Plateau, and introduced a management scheme to support beneficial land management for the species within the protected area.

The conservation of any migratory species requires a good understanding of their habitat requirements throughout its annual cycle, so that effective conservation measures can be implemented. Although previous work using satellite tag data has described the migration routes and breeding areas of the Slamannan Bean Geese, there has been little work investigating their wintering habitat requirements on the Slamannan Plateau. A research project, carried out by NatureScot, Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, Bean Goose Action Group and Edinburgh Napier University, aimed to better understand their wintering habitat requirements during the four months they spend on the Slamannan Plateau. In addition, the project team wanted to understand how the population’s current distribution matches with the protected area that was designated for them over ten years ago.

The study used state-of-the-art satellite tags, as well as field count data, collected by dedicated volunteers to identify their wintering habitats and foraging distribution. The satellite tags allowed the research team to identify specific fields individual geese were using, while the field count data showed how the population was using the wider landscape.

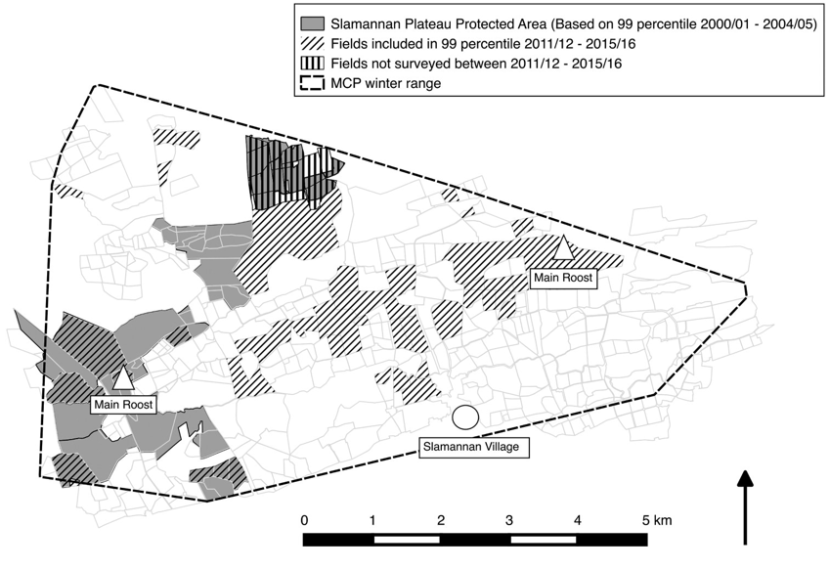

The results of this study revealed that the geese used a very small wintering area on the Slamannan Plateau, with individual ranges occupying less than 2 km2. Over the five winters of the study (2011/12 – 2015/16), the entire population used less than 20% of the grassland fields available to them in the study area, and the tagged geese regularly used the same small number of fields each winter, possibly offering the safest and least disturbed foraging habitats. The study also found that the geese strongly select improved pasture foraging habitats, most likely providing them with highly nutritious grassland swards.

When the protected area was designated for the geese, the majority of the population roosted and foraged within its boundaries. However, this research has shown that their distribution has shifted to areas largely outside the protected area (Fig. 1). The management scheme to maintain suitable goose habitats within the protected area was no longer directly supporting habitats now being used by the geese, and therefore the scheme was closed in 2018.

This work has highlighted the importance of on-going monitoring of priority species to ensure that conservation measures match habitat use and needs. For bird species using highly modified habitats, such as agricultural land, flexible species conservation measures should ideally track shifts in their distribution. However, implementing these is challenging when movements are so variable, and potentially influenced by factors we do not yet fully understand. This research has just been published in Bird Study.

Figure 1: The majority of the Bean Goose population foraged within the Slamannan Plateau protected area (solid grey) when it was designated in 2006, but had shifted to forage largely outside of the protected area ten years later (hatched area).

Facilitating NatureScot’s Use of Genetic Technologies

Brodie Thomas

I have recently joined NatureScot to facilitate the use of genetic technologies within the agency. My role focuses primarily on how environmental DNA (eDNA) can be used as a monitoring tool. eDNA has the potential to revolutionize monitoring as it can be relatively inexpensive, time-efficient and non-invasive. eDNA can be extracted directly from environmental sources e.g. air, water, soil and sediment. Within environmental sources, there is organismal DNA (when the whole organism is present in the sample e.g. bacteria) or extra-organismal DNA (bodily secretions e.g. mucus, skin, faeces that are left behind by animals as they move through an environment). Once the DNA is extracted, specific species and/or a wider array of taxonomic groups can be targeted, and we can detect their presence or absence from the environmental sample.

eDNA has repeatedly shown to outperform traditional sampling methods for some species; particularly improving the detection of elusive, or cryptic, species. It gives a truly good account of species richness in a given area. However, eDNA is far from perfect, particularly when it comes to estimating abundance, but it does offer another approach to monitoring biodiversity. The more evidence generated the better we can respond to environmental changes and improve management. I believe this technique has a bright future and I’m very excited to develop its incorporation into monitoring within NatureScot. I’ll also have the chance to work on a wide range of DNA-related topics within NatureScot – including getting to grips with the thorny issue of gene editing.

About me!

I’ve always had a strong connection with nature and this came from growing up in the South Wales valleys, where long mountain walks were the norm. I stayed in Wales for the majority of my life and after completing my schooling, studied Biochemistry at Cardiff University. Upon graduating, I dabbled with the idea of teaching Science and decided to gain some work experience before committing myself to teachers’ training. After a year of working as a school science technician, I decided to undertake a PGCE in Secondary Chemistry. I taught in Wales for a time before making my international debut in teaching overseas. My first international role was in Yangon, Myanmar. I arrived just before the country started to open up to visitors following a landslide victory by the National League for Democracy in 2015. I loved my time there, and stayed for three years. I then had the opportunity to teach in New Zealand, and was lucky enough to experience the plethora of unique flora and fauna the country has to offer.

Through new hobbies and experiences, like scuba diving and hiking. I became more exposed to the myriad of issues affecting our planet. This inspired me to start environmental clubs in the schools that I taught in, helping students to reconnect with nature and spread awareness. However, I felt I wanted to do more and in 2020 decided to leave teaching in New Zealand to travel and volunteer in grassroots conservation programmes. The eruption of COVID-19 quickly ended this experience, and I had to return to the UK. I applied for an MSc in Ecology and Conservation in Aberdeen, and completed it in August his year.

Throughout my MSc course, I found myself drawn towards molecular ecology and as a result, a large majority of the projects I undertook were molecular based, including my thesis. This strong focus on molecular biology through my undergraduate and postgraduate education has led me to where I am today!

Long-term research informs conservation action for Scotland’s red-billed choughs

Sarah Fenn, Amanda Trask and Jane Reid

The red-billed chough population in Scotland is in a perilous state, with fewer than 50 breeding pairs remaining on Islay, Colonsay and Oronsay. Working closely with colleagues Eric and Sue Bignal (Scottish Chough Study Group), Pat Monaghan (University of Glasgow), Davy McCracken (SRUC) and NatureScot staff, we are striving to provide the strong scientific basis required for effective, evidence-based conservation measures to sustain this population.

To understand what drives changes in population size, we previously used long-term monitoring data to quantify variation in chough survival and breeding success among areas and years on Islay. This work highlighted that low survival in the pre-breeding years is a key factor affecting the current status of the population, and guided a multi-year (2010-present) programme of supplementary feeding targeted at this sub-adult stage. We have now shown that this intervention has successfully reduced the immediate risk of population extirpation, but is not a long-term solution (Trask et al. 2019; Fenn et al. 2020, 2021). Our report to NatureScot (Trask et al. 2020) sets out key elements of the conservations strategy that are now required to ensure longer-term population persistence.

Our recent review of our long-term work highlights the value of successfully integrating science and conservation (Reid et al. 2022). This case study illustrates a mutually beneficial interaction between pure and applied research - how scientific advances achieved through the long-term studies can inform conservation actions, and how conservation-motivated analyses advance our fundamental understanding of population processes.

Our recent work was facilitated by two NERC-NatureScot CASE PhD studentships, awarded to Sarah Fenn and Amanda Trask. We hope our study and approaches can inspire wider work on other endangered populations. The challenge now is to ensure that our understanding of the drivers of population change is translated into effective and sustainable land management programmes, reversing the chough decline and benefitting biodiversity on the beautiful island of Islay.

References

Fenn, S, Bignal, EM, Bignal, S, McCracken, DI, Trask, AE, Monaghan, P, Reid, JM (2021) Within-year and among-year variation in impacts of targeted conservation management on juvenile survival in a threatened population. Journal of Applied Ecology online.

Fenn, SR, Bignal, EM, Trask, AE, McCracken, DI, Monaghan, P, Reid, JM (2020) Collateral benefits of targeted supplementary feeding on demography and growth rate of a threatened population. Journal of Applied Ecology 57, 2212-2221.

Reid, JM, Bignal, E, Bignal, S, McCracken, DI, Fenn, SR, Trask, AE, Monaghan, P (2022) Applying population and evolutionary ecology to conservation strategy through long-term studies of red-billed choughs. Journal of Animal Ecology in press.

Trask, AE, Fenn, S, Bignal, E, McCracken, DI, Monaghan, P, Reid, JM (2019) Evaluating the efficacy of independent versus simultaneous management strategies to address ecological and genetic threats to population viability. Journal of Applied Ecology 56, 2264-2273.

Trask, AE, Bignal, E, Bignal, S, McCracken, DI, Fenn, SR, Monaghan, P, Reid, JM (2020) Conservation strategy for red-billed choughs in Scotland: Assessment of the impact of supplementary feeding and evaluation of future management strategies. Commissioned Research Report for Scottish Natural Heritage.

Moths – Trends and Indicators – latest results for Scotland

Simon Foster

In 2019, we took a big step forward in using data from a range of moth surveys in Scotland to allow us to look at changes in numbers and their distributions. Using methods developed by Dennis et al. 2013 we can look at trends from variety of species. With the latest data available, we have updated the results to provide the current state of moths in Scotland.

Moths play an important role in telling us about the health of our environment, since they are widespread, found in many different habitats, and are highly sensitive to environmental changes. Their value as part of the food chain, and in providing pollination services as well as providing cultural services, make them particularly useful indicator species. This latest indicator also contributes to the Marine and Terrestrial Indicators.

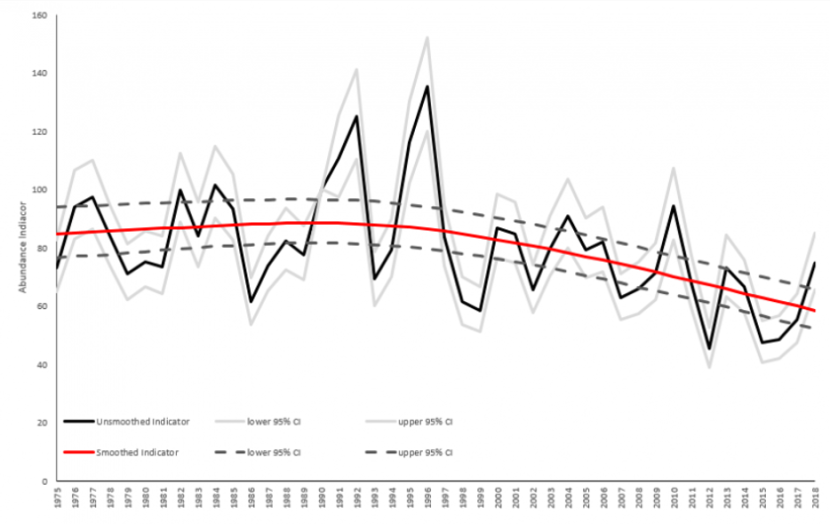

On average, moth abundance has declined by 29% since 1975, and almost halved since 1990 (46% decline to 2018). Over the last 29 years, almost five times as many species have significantly decreased in abundance compared to species showing significant increases (87 vs 18 species).

Multi-species indicator of change in abundance of moths in Scotland for 1975-2018, with 95% confidence interval, and smoothed indicator shown in red. The indicator is scaled with respect to a 1990 baseline year.

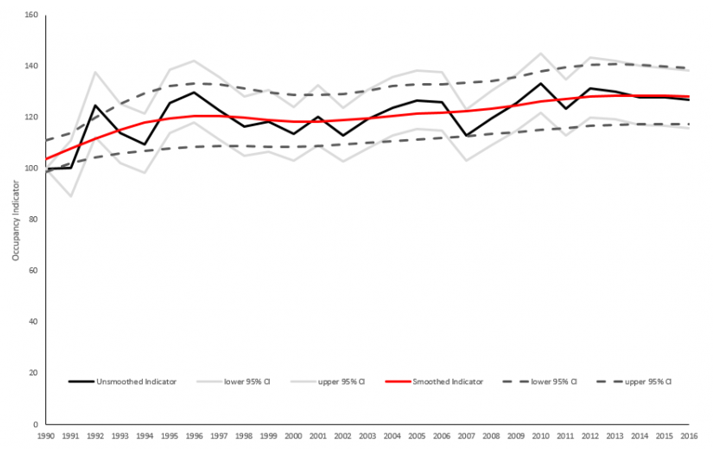

Whilst abundance has declined, occupancy has increased. A multi-species indicator for moth distribution change shows that moth occupancy has increased by 16% for 1990-2016, with almost twice as many species significantly increasing than significantly decreasing in distribution (78 vs 41 species). Short-term change suggests that overall increases in occupancy continue (9% increase for 2007-2016).

Multi-species indicator of change in distribution (occupancy) of moths in Scotland for 1990-2016, with 95% confidence interval, and smoothed indicator shown in red. The indicator is scaled with respect to a 1990 baseline year.

Differences between species’ changes in abundance and distribution may be explained by opposing influences of climate facilitating species’ range expansions, whilst for some species this is countered by negative impacts from habitat changes and land management practices which may be driving population declines.

The indicator provides us with the most up to date trends on moths, but it should be noted that some species are still not represented by the indicator, particular those which are rare or restricted. Butterfly Conservation are working on addressing some of these gaps in the future. Species’ occurrence records for macro-moths in Scotland were obtained from the National Moth Recording Scheme database, which were collated from recording by volunteer observers.

For Scotland, there are around 1.4 million records for 1970-2016, covering 545 species, from 12,106 1-km grid squares. This is a great testimony to the painstaking work of everyone kindly submitting records.

One Earth. One home. One Shared Future – Scotland’s Environment strategy

Simon Foster

In February 2020 the Scottish Government published the Environment Strategy vision. This sets out the long-term ambitions for Scotland’s natural environment and our role in tackling the global climate and nature crisis. The summary of the vision is:

By 2045: By restoring nature and ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change, our country is transformed for the better - helping to secure the wellbeing of our people and planet for generations to come.

In February 2021 the Environment strategy: initial monitoring framework was published. This identified an initial set of indicators for the Environment Strategy Monitoring Framework and outlined high-level plans for reporting progress. The Monitoring Framework will be maintained as a live framework. It will be updated, as necessary, to reflect developments in policy and evidence. This initial selection of indicators draws on an analysis of existing environmental indicators and in-depth discussions with a wide range of partners and stakeholders. This process has highlighted a wealth of relevant environmental data we can draw on. It has also identified some areas where additional work is needed to develop robust measures of progress. These areas will be explored as the Monitoring Framework is further developed.

In November 2021, the Environment Strategy: Initial Monitoring Framework website went live. Scotland's Environment Strategy provides an overarching framework to bring strategies and plans together, and identify new strategic priorities and opportunities. It will help to guide us as we protect and restore Scotland's natural environment and strive to live within our planet's sustainable limits. In doing this, we will support the wellbeing of people in Scotland and strengthen our economy.

Monitoring Framework Overview

In developing the Environment Strategy Initial Monitoring Framework, a set of high-level indicators that provide a strategic and accessible overview of progress towards each outcome was chosen. Additional indicators will be explored as the Monitoring Framework is further developed. The initial set of indicators for each outcome is shown in the graphic below.

The website contains a wealth of information, including the Environment Outcomes Hub. The Monitoring Framework includes nineteen high-level indicators. There are between two and five indicators for each of the six outcomes.

The indicators were selected to help tell a strategic story of progress towards each outcome. However, given the broad scope of the Environment Strategy outcomes, the indicators alone cannot provide a complete picture of progress. The indicator data should therefore be considered alongside wider sources of evidence in assessing progress towards the Environment Strategy outcomes.

This work will be integral to measuring Scotland’s progress towards the Environment Strategy Vision. The indicators and measures will be regularly updated and will evolve over time as new, improved methods and data become available.

Seabirds and climate change

Dr Lucy Quinn, Marine Ornithology Adviser

NatureScot are pleased to announce the publication of a number of related reports on how climate change is predicted to affect seabirds by 2050. This BTO and RSPB-led project is part of a wider Marine Protected Area Management and Monitoring (MarPAMM) project which primarily concentrates on the INTERREG VA area, covering western Scotland, Northern Ireland and part of the Republic of Ireland.

The project produced a number of outputs which can be found online. The first was a review of climate change mechanisms that affect seabirds, whether these are direct effects such as increased rainfall flooding burrows, or indirect, such as temperature-mediated changes on prey populations. Secondly, the project modelled changes in abundance for seabird species both at the INTERREG VA scale and the wider UK scale, using both terrestrial and oceanographic climate data. Of the 19 seabird species modelled, 14 are predicted to decline by 2050. Arctic skua is predicted to no longer be a breeding species within the UK and large-scale losses are also predicted for puffin, fulmar, storm petrel and some tern species. Despite the majority of species being predicted to decline some, such as black-headed gull and shag, are expected to increase. Thirdly, the project modelled distribution change for seven seabird species. Five of these are expected to decline significantly during the breeding season: kittiwakes, guillemots, razorbills, sandwich terns and Arctic terns. Finally, the project summarised the vulnerability of each species to climate change, and considered potential species and habitat climate change adaptation options available. These may be counteracting adaptation options, such as creating new intertidal or single habitat for terns, or compensatory adaptation responses not directly relating to climate change, such as managing recreational use of coastal habitats to reduce human disturbance.

Large-scale changes are predicted for our UK seabird species and the implications of this project’s results will be discussed further within NatureScot to help inform our management plans and wider strategic seabird conservation work.

Scotland’s first seagrass restoration handbook

Flora Kent, Marine Enhancement Adviser, NatureScot

NatureScot has developed Scotland’s first seagrass restoration handbook. This important resource titled, Seagrass restoration in Scotland - Handbook and Guidance, provides practical information as well as guidance on aspects such as site suitability, licensing and monitoring. The handbook has been developed by NatureScot in collaboration with Marine Scotland and Project Seagrass. The handbook includes a review of the research into different restoration techniques including seed development, biosecurity treatments and the impact of predators. Monitoring techniques are also reviewed and the handbook provides recommendations, such as on indicators of ecosystem health and blue carbon sampling.

Seagrass beds are a Priority Marine Feature in Scotland and provide a range of ecosystem services, including blue carbon and biodiversity benefits. Protection and enhancement of these vital yet sensitive beds is therefore important in the face of the climate and biodiversity crises. Providing seagrass restoration guidance with a strong evidence base is integral to our wider work on nature based solutions and marine enhancement.

NatureScot have been working with researchers, NGOs and community groups to develop the evidence required to support advice on restoration activities in Scotland. For example, we have supported a seagrass genetics project in collaboration with the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and a habitat suitability MSc project with the University of Edinburgh. The seagrass handbook provides a review of such research but also highlights knowledge gaps.

Research Reports Published in May – June 2021

NatureScot Research Report 1269

Using peatland surface motion (bog breathing) to monitor Peatland Action sites

Interferometric satellite radar (InSAR) provides a means of measuring peatland surface motion continuously and is not limited by scale or cloud cover. Previous InSAR investigations demonstrate the potential for InSAR to quantify surface motion and hence peatland condition. Time series of peatland surface motion has been related to precipitation, water level and vegetation composition. Validation in the Flow Country during the NERC funded InSAR ToPS project has also shown that ground motion derived from InSAR causally relates to motion on the ground. Using the Intermittent Small Baseline Subset (ISBAS) data processing approach, allows us to gain excellent coverage over forested and rural areas. This is a key step in being able to access the full spatial and temporal coverage of InSAR required to determine continuous characterisation of peatland surface motion.

A reliable national scale approach to measuring peat condition based on InSAR has the potential to provide: a better estimate of the amount and distribution of peatland and associated carbon inventories; a means of assessing the impact of investment in peatland restoration; and the potential to identify areas at high-risk of peat instability, fire and erosion. This project seeks to evaluate these applications over selected peatland sites in Scotland.

NatureScot Research Report 1270

Infaunal and PSA analyses of benthic samples collected from the Sound of Barra in 2018

This report presents the findings of the analysis of 72 seabed samples collected off the Outer Hebrides in 2018. Sampling was carried out to improve knowledge of the distribution and condition of species and habitats of conservation importance within and around the Sound of Barra SAC. Analysis was undertaken to determine the current condition and distribution of maerl and coarse sediment habitats on the eastern side of the sound.

NatureScot Research Report 1274

Survey of the Tayside Area Beaver Population 2020-21

The Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) has officially been accepted as reintroduced to parts of Scotland, and was made a European Protected Species in May 2019. Previous commissioned population survey work has demonstrated a growing population size and range (Campbell et al. 2012; Campbell-Palmer et al. 2018).

This study provides details of the latest survey carried out from late 2020 to early 2021. It describes the methodologies and results to determine the current distribution, territory number and associated population estimate. Evidence of a range of human land-use conflict issues were reported, along with evidence of increasing mitigation measures. Recommendations for future survey actions are made.