NatureScot Research Report 1313 - Teaching, learning and play in the outdoors: a survey of provision in Scotland in 2022

Year of publication: 2023

Authors: Mannion, G., Ramjan, C., McNicol, S., Sowerby, M. and Lambert, P. (University of Stirling)

Cite as: Mannion, G., Ramjan, C., McNicol, S., Sowerby, M. and Lambert, P. (2023) Teaching, Learning and Play in the Outdoors: a survey of provision in 2022. NatureScot Research Report 1313.

Keywords

Outdoor; learning; outdoor play; education; school; pre-school; early years; Curriculum for Excellence; Learning for Sustainability; professional learning

Background

The provision of outdoor educational and play-based experiences are entitlements in Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence for children aged 3-18 (Scottish Executive, 2004; Learning and Teaching Scotland, 2010; Scottish Government, 2016a). Outdoor learning is also embedded across the Professional Standards for teachers by the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS 2021). Within the curriculum, outdoor learning can be an approach in any subject and in interdisciplinary learning. Alongside ‘global citizenship’ and ‘sustainable development education’, outdoor learning is a core component of ‘Learning for Sustainability’ (Scottish Government, 2012). Outdoor learning and play are keystone elements of Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence. They contribute to a wider set of policy imperatives dedicated to improving young people’s health, wellbeing, and educational outcomes, achieving the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, and Scotland’s target to become a Nature positive, Net Zero country.

This survey of outdoor learning builds on two previous surveys funded by NatureScot and partners, which assist us in understanding the duration, focus and locations of provision. Conducted in 2022 as the pandemic eased, the findings are timely allowing us an opportunity to reflect on changes in provision, supports for practice, and targets set by government in the Action Plan for Learning for Sustainability (Scottish Government, 2016).

This report provides an in-depth picture on teaching, learning and play provisions in early years and in primary schools, replicating an approach taken in both 2006 and 2014. We report here on circa 200 outdoor learning events provided by staff working in 19 early years centres and 25 primary schools randomly sampled across diverse catchment areas. This cross-sectional survey allows for comparison over time. Secondary school participation in the survey was too limited to include here. The low response rate from secondary schools most likely reflects a sustained period of pressure and stress in this sector as they returned to examinations after Covid.

Findings indicate sustained uplift in outdoor provision in early years settings but considerable decline to an average of 7 minutes per week in the primary school sector when comparisons are made with previous surveys. In addition, in 2022, we asked participants to self-report on professional learning experiences and confidence levels with respect to outdoor learning and play and Learning for Sustainability. Findings show low and inconsistent levels of professional learning and confidence across both sectors. Taken together, our analysis provides a critical starting point: further action is needed to improve outdoor learning provision and Learning for Sustainability, particularly through policy change and enhanced support for pre- and in-service professional learning opportunities in these areas.

Main findings

Early Years’ provision outdoors has increased compared to 2014 survey findings. As in 2006 and 2014, this 2022 survey of outdoor provision occurred over a two-week period within May and June. We had 19 randomly sampled settings participating. The survey showed that on average 39% of the time at the centre was spent outdoors. This figure has risen from 23% in the 2006 survey, and from 36% in 2014. Early years provision continues to focus strongly on ‘play’ (as in 2014). 2022 data show a small increase in ‘off-site’ provision in woodland locations.

Primary Schools’ outdoor provision has decreased compared to 2014. As in previous surveys, we captured durations of all outdoor learning events (not Physical Education) for an eight-week period in May-June. The 25 randomly sampled schools provided considerably less time outdoors compared to 2014. In 2014, the duration ‘per pupil per week’ was 30 minutes. In 2022, this was 7 minutes. Covid restrictions meant residentials were very uncommon, but this only accounts for part of the decline.

Primary Outdoor Provision Location and Focus. Use of grounds, visits to locations beyond the grounds, and beyond the local area were all down in 2022. Proportionally, by distance, 87% of the time outdoor was spent in school grounds or up to 1km from the school. By location, visits to woodlands accounted for 18% of the time spent outdoor and visits to local greenspaces (parks and gardens) accounted for 12%. Health and wellbeing, science and mathematics are the top curricular areas. ‘Practical activities’, ‘teamwork’, ‘nature’ and ‘play’ were the main foci. Less than 30% of outdoor events addressed Learning for Sustainability.

Secondary Schools. Only two secondary schools took part in the survey. These data are not reported upon as a result. Difficulty in recruitment was likely due to on-going pressure on the sector, pupil and staff absences, Covid restrictions, and the return to examinations at the time of the survey.

Practitioner Confidence. Considerable numbers of staff across primary and early years lack confidence in facilitating outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability. Early years practitioners reported higher confidence levels than school staff with respect to both outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability. Primary teachers had higher confidence in outdoor learning (62.9%) than in Learning for Sustainability (40.3%).

Professional Learning. Staff in receipt of lower levels of training also report lower confidence in outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability. Provision of between 6 and 10 training sessions (where each ‘session’ considered to be approx. a half day event) was associated with increased confidence in outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability. Participants who reported higher confidence worked in settings that had greater provision.

Perception of Provision Post-Covid. A little over half of all practitioners surveyed felt that provision had increased compared to pre-Covid. Just less than a third of respondents felt that provision has decreased.

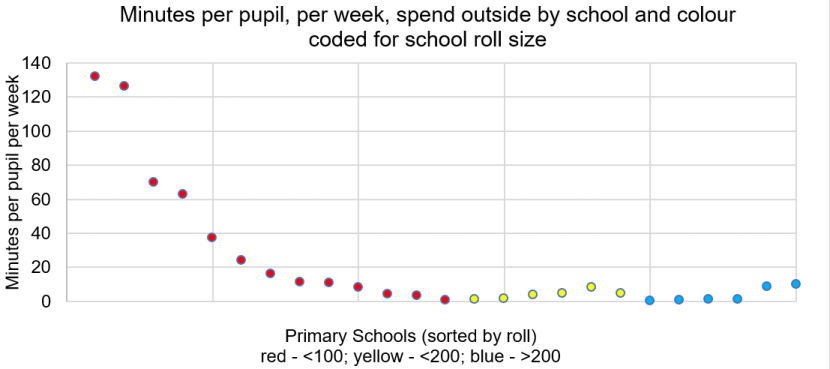

School Size and Outdoor Provision. There is a notable variation in provision. Schools providing more outdoor learning time tended also to be smaller in roll. All schools offering more than 10 minutes per week of outdoor provision had a roll of less than 100 pupils.

Outdoor learning continues to be experienced by teachers as curriculum-enhancing. Teachers’ reports overwhelmingly indicate outdoor learning enhances engagement and active learning, and was seen to render lessons more enjoyable and relevant. Our survey shows greenspace use for outdoor learning meets the need to provide for a wide variety of subject areas and for Learning for Sustainability, and that there is also improved engagement compared to indoor lessons.

Summary Recommendations

- Across all sectors of education, the provision of outdoor learning and play needs to be expanded to provide for the experiences and outcomes outlined in Curriculum for Excellence.

- Evidence suggests that an essential support for the expansion of outdoor provision will be the opportunity to engage in high quality professional learning. Linking professional learning for outdoor provision and Learning for Sustainability will be necessary to increase teacher confidence and expertise in both areas.

- In early years, greater support for off-site visits and use of local areas will further expand provision.

- In primary schools, there is a need to increase all types of outdoor provision: in school grounds, off-site, in local areas, and through day-long, and residential trips. Larger schools, schools in urban areas, and schools in areas of deprivation will need targeted support.

- Increased use of natural greenspaces and ‘local nature’ by all sectors will further enhance provision especially learner engagement, challenge and enjoyment.

- Further research is required to understand the links among quality outdoor provision, curriculum policy enactment, and wider policy priorities, including young people’s participation and rights, biodiversity loss, and climate change.

- Further surveys are needed to understand outdoor provision in secondary schools and in special school settings.

Acknowledgements

The research was generously funded by a consortium of government-funded agencies. The main funder was NatureScot, with further support from Scottish Forestry, Historic Environment Scotland, Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park Authority and the Cairngorms National Park Authority. Staff from each funder formed an advisory group which informed the work.

This research would not have been possible without the generous support of the teachers and early years practitioners who gave their time and efforts to provide the information presented here.

Thanks are due also to the 18 local authority staff for supporting and promoting the research to all the schools and early years establishments in their local authority areas.

We are grateful for responses to our requests for inputs of relevance from across the research community networks in OL and Learning for Sustainability in Scotland.

Abbreviations

Additional Support Needs: ASN

Curriculum for Excellence: CfE

General Teaching Council for Scotland: GTCS

Higher Education Institutions: HEI

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education: HMIE

Information and Communications Technology: ICT

Initial Teacher Education: ITE

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: OECD

Physical Education: PE

Social Index of Multiple Deprivation: SIMD

Learning for Sustainability: LfS, capitalisation used throughout to denote the policy context specific to Scotland.

Outdoor learning: Herein, the term includes all kinds of provision for learning and play outdoors: outdoor learning, education in outdoor settings, outdoor education including residential-based outdoor provision, outdoor play. It did not include breaktime activity or timetabled outdoor physical education for schools in the survey.

Introduction

Context

In this section, for the period since the last national survey (published in 2015), we refer to some of the outputs and practices of relevance to outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability. We refer to some relevant policy initiatives, research outputs (from researchers based in Scotland), and developments in professional learning and teacher education. Our contextualising summary is of course partial.

Policy

Following critical commentary from an OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) report published in 2021, the Scottish education system has been under review. Pre-Covid, ongoing review and change has characterised the curriculum implementation process in Scotland with policy initiatives such as the National Improvement Framework (NIF) (Scottish Government, 2023), the Scottish Attainment Challenge (SAC) (Scottish Government, 2021a) and Scotland's Race Equality Framework (Scottish Government, 2016b). December 2022 saw the completion of the ‘National Discussion on Education’ led by independent facilitators. Commentators agree there has been increased bureaucratic demand on teachers taking time away from quality teaching and learning, including outdoor provision. In the ‘refreshed narrative’ of Curriculum for Excellence, Learning for Sustainability is an entitlement, whilst using the outdoors and our built and cultural heritage are positioned as key to supporting learning.

In the period between our surveys of outdoor learning, we have also seen increased emphasis on school-based core curricular areas and in improving outcomes for the less advantaged. The Scottish Attainment Challenge set out to address the poverty related attainment gap in Scottish schools. This policy was introduced in 2015 and is described as: “Prioritising improvements in literacy, numeracy and health and wellbeing of those children adversely affected by socio-economic disadvantage” (Scottish Government, 2021a). In a minority of cases, funding helped with the development of ‘outdoor learning, Green Gyms, and community gardens’ (Scottish Government, 2021a) as measures contributing to improving health and wellbeing of pupils. The majority of initiatives focused on literacy and numeracy interventions and approaches to improving health and wellbeing.

Since the last survey in 2014, Curriculum for Excellence through Outdoor Learning (2010) and Learning for Sustainability (Scottish Government, 2012) have been part of the Scottish policy landscape. In early years, the Scottish Care Inspectorate – the regulatory body – have provided guidance in ‘My World Outdoors’ which identifies it as an expectation that children have “daily opportunities to spend time outdoors” and “explore the natural environment” (Care Inspectorate, 2016, pg. 11). Outdoor experiences are also built into curriculum guidance ‘Realising the Ambition’ (Scottish Government, 2020):

“Take me outdoors frequently to help me learn about my wider world. Experiencing fresh-air and being outdoors in different weathers and natural environments develops my understanding of life and benefits my wellbeing.”

Alongside policy, civic organisations and charities have continued to press for outdoor learning and play to be made a priority. In 2018, for example over 50 education, healthcare, governmental and environment groups created Scotland’s National Outdoor Play and Learning Position Statement (Inspiring Scotland, 2022). The revised GTCS standards continue to position outdoor learning, sustainable development education, and citizenship education as an ‘entitlement’ for all pupils (GTCS, 2021). In Scotland, there is currently a cross-party Bill in progress aiming to ensure that young people have opportunity to experience residential outdoor education to an approved educational standard, raising a debate about how best to support increased quality and duration of provision across all location types. Our current study sets out to inform on-going discussion about outdoor learning as a core feature of education in the Scottish curriculum, the degree of progress being made towards the entitlement to outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability, and the degree of readiness of staff to enable this to happen in their local contexts.

Research Outputs on Outdoor Learning (Scotland)

In research, there has been considerable growth in activity, with many notable Scotland-based research contributions in the period 2015- 2022. In this introduction, we cannot comprehensively include all of the research outputs and activity. It bodes well that there are many active early career and experienced researchers now inquiring into aspects of outdoor learning, outdoor play, and Learning for Sustainability.

As part of the refresh of the Learning for Sustainability (2030) Action Plan, the Scottish Government commissioned a team based at the University of Dundee to investigate understandings and experiences of Learning for Sustainability from the perspective of practitioners and young people. The report (Scottish Government, 2023a) suggests that:

“young people believe they should have far greater opportunities for outdoor learning and that this will support the synergy of practice and theory allowing them to relate LfS to the outdoors in their school and community settings”

The report identifies a need to:

“enhance opportunities for outdoor learning so they are more frequent and broader in scope”

This important research highlights the opportunities that outdoor provision can offer in helping young people to access their entitlement to Learning for Sustainability. Taking a connected approach to outdoor provision in relation to Learning for Sustainability has the potential to impact on practice across all learning sectors.

In the summary volume, Scottish Education there are now chapters on Learning for Sustainability and outdoor learning (see Higgins and Christie, 2018; Higgins and Nicol, 2018) reflecting the now widely accepted mainstream position of these topics for practitioners and academics alike. In 2020, the Educational outcomes of Learning for Sustainability: literature review (Christie and Higgins 2020) provided us with valuable summaries of the evidence-informed outcomes of Learning for Sustainability provision. Learning for Sustainability pedagogies which include outdoor elements, are seen, for example, to contribute to learners’ overall development (knowing themselves and the world around them), their understanding of citizenship, their academic learning (through for example reducing stress, improving wellbeing), and their skills for life and work (for example critical thinking). Christie and Higgins (2020) suggest that while there is not currently any academic literature to suggest that Learning for Sustainability has a direct impact on the poverty related attainment gap, they indicate how Learning for Sustainability can raise “awareness of the relationship between a sustainable future and a more equal society” (Christie and Higgins, 2020, pg. vii). There is still scope for a discrete review of the outcomes of outdoor learning akin to this review.

In relation to outdoor learning provisions, a few research outputs are worthy of note. On the topic of staff development, Christie et al.’s (2019) article showed that Learning for Sustainability is misunderstood by many staff in schools in line with evidence from this study. Other research contributions from staff working in the Scottish Higher Education context include Barrable’s (2022) volume on nature-based learning via greenspace use. We note Dunkley and Smith (2019) research contribution on young people’s experiences of national parks visits and Dunkley’s (2022) paper on role of citizen science in education for sustainability. Gray’s (2022) paper highlights the contribution of garden-based learning to wellbeing and sustainability. Gray and Colucci-Gray (2019) attended to the role of outdoor experience in student teachers’ development whilst Mannion (2020) and Lynch and Mannion (2021) identify the features of a more place-responsive research and pedagogy needed for educators in outdoor learning. Scrutton’s many outputs included research that investigates the personal and social benefits of adventure education, residential adventure education, which more especially accrued to learners from deprived areas (Scrutton, 2015). With authorship from Scotland, the international PLaTO (Play Learn and Teach Outdoors) initiative gathered 22 researchers to provide an original ‘harmonised taxonomy’ of terms for outdoor learning and play. In early years, outdoor play and learning have gained attention in both research and in advice for practice (MacQuarrie et al, 2015, Robertson, 2014, 2017).

Reflecting on the position of outdoor provision in the school inspection context, Beames and Polack (2019) looked at Her Majesty’s Chief Inspectors’ reports (for 2011 – 2018) for mentions of outdoor learning across over 800 schools. They reported that only about one third of secondary school inspection reports mentioned outdoor learning in ‘grounds, local green space or local community during school hours’ while nearly ¾ of primary schools’ reports had such a mention. These data support the view that there is a need to address how inspections are conducted on outdoor and Learning for Sustainability provision. Their evidence suggests substantial numbers of schools may not be providing much in these curricular areas in line with our findings herein.

There are various networks of practitioners, policy actors, school-linked providers, and researchers in outdoor learning in Scotland. These include the National Network for Outdoor Learning, the Scottish Government Outdoor Learning Group, and the Outdoor Learning Research Network. Through doctoral training and research, Scotland also has a valuable and enviable pipeline in the form of expertise amongst early career outdoor learning-focused researchers. Many outdoor learning-related doctorates have been completed or are in-train across HEIs with some in receipt of funding. These include, for example, Masters’ (ongoing) study of the eco-social, health-related and population-wide outcomes of the work of environmental organisations (such as the John Muir Trust and Keep Scotland Beautiful), Mackie’s current study on the role of natural heritage in supporting learning for sustainability (Magnus Magnusson scholarship funded), Ramjan’s (ESRC-funded) study of ecological citizenship and the role of citizen science in schools (2023), Arts’ (2022) study of the interactions of people, technology and nature, Fenwick’s (2021) study of the intricate relationship of outdoor learning with the curriculum, Baker’s (2015) study on policy development of outdoor learning in Scotland, and Mattu’s (2016) study of primary school visits to farms. This growing body of research evidence provides a wide range of findings that can be drawn on to inform ongoing policy and practice in Scotland.

Young People’s Research

Young people’s own research about outdoor provision and Learning for Sustainability are increasing in scope and criticality especially in relation to the climate and nature emergencies. Teach The Future – an amalgam of young people’s environmental groups with support from the National Union of Students and active academic researchers – reviewed policy in Scotland. They seek fulfilment of the commitments to outdoor learning made in the Vision 2030+ action plan and call on the Scottish Government to ensure education in the outdoors is linked to ‘connection to nature’ and learning about the ‘climate emergency and ecological crisis’ (Teach the Future, 2020). In 2022, Scottish Government supported young people themselves in researching Learning for Sustainability via a Children’s Parliament inquiry (Children’s Parliament, 2022). 132 children aged 2-13 investigated provision and summarized young people’s views about the Learning for Sustainability curriculum with a focus on outdoor learning. Adopting a rights-based approach, these young researchers also focus on response-making to climate change, reminding civic bodies that young people have a right to an education that helps them develop respect for the natural environment and have a right to express a view about and help shape the curriculum they experience. Two of the Children’s Parliament’s ‘Calls to Action’ state:

- All children should have the chance to learn outdoors throughout the school year.

- Children should be able to regularly learn about climate change and sustainability outside in nature.

- Being able to learn outdoors should not depend on where your school is based: every school in Scotland should have outdoor spaces to learn and play in.

- All children should have the opportunity to go to an annual outdoors school camp.

- Outdoor learning should be part of every school subject.

- Teachers should plan outdoor learning into all their subjects at the start of each term.

(Children’s Parliament, 2022, pg. 18)

Professional Learning for Schools and Practitioners

In Initial Teacher Education (ITE), there are signs that outdoor learning is gaining recognition as part of pre-service provision. We note the appointments of ITE staff in some HEIs with considerable or complete attention being paid to outdoor learning in their role specification. Across ITEs, we see the use of outdoor spaces in, or near the campus of universities – such as greenspaces, woodlands, urban locations, zoological gardens, parks etc. – being used for teacher education experiences. On some campuses, discrete locations are developed or set aside for pre-service ITE outdoors that include greenspaces and bluespaces with specialist staff leading developments. Queen Margaret University exemplify this trend, having worked in partnership with Architecture and Design Scotland (A&DS) and NatureScot to develop dedicated outdoor learning spaces on campus, including the creation and use of a Wee Forest (a tennis court sized, densely planted native woodland, part of the ‘Tiny Forest Global Family’). Approaches to outdoor woodland education forms part of teacher education in some contexts. We note that pre-service education will feed around 3,000 new staff into the school sectors annually out of a staff of some 50,000 Scotland-wide. Thus, changing the school staff capabilities at scale even in the medium term, will require substantial attention to in-service education and professional learning.

In-service Supports and Professional Learning

A growing number of bodies support in-service professional learning in Scotland. These include social enterprise organisations, charities and private companies. NatureScot have directly supported over 100 schools is disadvantaged communities to access local greenspace through their ‘Learning in Local Greenspace’ project (NatureScot, 2022). Other organisations have received funding from NatureScot to enhance or enable outdoor provision, such as Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Eòlas Outdoor learning, Under the Trees, and Urban Roots. As one of the main providers, Learning through Landscapes (LtL) continue to provide considerable in-service provision both in-person and online for schools wanting to develop grounds and / or their local outdoor provision. The wide range of training opportunities ensures schools have many go-to organisations for high quality provision and whole-school development. Some, such as LtL, have a strong history of developing programmes based on research evidence. This has led to long term courses, and some are accredited by General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS), as well as shorter in-service days focused more tightly on specific areas of curriculum.

Many local authorities, with support from the Scottish Advisory Panel for Outdoor Education (SAPOE), have developed materials and programmes to support staff in provision. This has included online learning, and in-person training. We are aware of a number of authorities with training or support programmes (for example, Fife, East Ayrshire, Dundee, Dumfries and Galloway, Falkirk and Edinburgh). SAPOE’s (revised in 2021) ‘Going Out There’ guide to safe practice for off-site visits continues to provide user-friendly framework for schools in terms of risk assessment and planning.

Many grassroots and independent providers offer support for in-service staff. This is especially noticeable in the early years sector and in woodland learning and forest school type training. There is a thriving ‘Outdoor Woodland Learning’ (OWL) network with groups across the country providing training and support especially in the area of Forest Kindergarten provision. Of note too is Juliet Robertson’s world-renowned provision of support for outdoor learning for all sectors via Creative Star whose website is now in receipt of over 1 million visits; thousands of educators have benefited over the years from her workshops and training. The HEI sector offers a number of master’s level programmes for in-service staff where outdoor learning can be an optional focus. Many opportunities exist for targeted professional learning for early years practitioners via private and statutory bodies. For example, in some Further Education colleges and in University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) students may avail of an award in Forest Kindergarten.

Educational Self-Evaluation and Inspectors’ Review,

Through the Scottish ‘self-evaluation’ framework How Good Is Our School, establishments are pressed to internally and transparently demonstrate developments towards outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability across the life of the school or establishment. In 2022, the inspectorate of schools and early years settings carried out a thematic review of ‘Successful Approaches to Outdoor Learning’ (HMIE, 2022). Using 35 case studies selected to exemplify effective practice, the HMIE review usefully identified features and approaches that were supportive. The document identified some key inputs and supports including leadership, professional learning and partnership working with practice often focusing on wellbeing. The report encourages outdoor curriculum-making through dialogue with learners and active engagement with pupil views. Further, HMIE suggested that the Covid pandemic had ‘accelerated the breadth and depth of outdoor learning’ (pg. 4). In our survey of randomly selected establishments, 58% of early year and 61% of primaries also believed that provision had increased compared to pre-pandemic levels. However, our survey of provision indicates that for our randomly sampled primary schools, provision had very considerably decreased compared to 2014 levels.

Summary

The policy environment has had mixed effects on outdoor provision over time, sometimes with the effect of decreasing its importance. All core educational policy initiatives, such as the Attainment Challenge, need to explicitly encourage outdoor provision enhancement. The growth of an outdoor learning research community in Scotland bodes well, but the ever-present challenge to link research and policy with practice remains. Young people’s own research sets out a clear call for more regular outdoor provision that connects with nature and addresses the climate emergency. Evidence in our survey on school and early years pre-service and in-service education shows there is scope for a more comprehensive offer to support staff confidence and expertise. Whilst closer working arrangements between in-service professional learning providers have arisen through the Covid period (especially via online), the challenge of structures, routines and funding for a system-wide approach to teacher professional learning on outdoor provision and Learning for Sustainability remains. Post-Covid, the factors that hinder or support provision include, leadership at school and local authority level, access to usable outdoor spaces, timetabling constraints, and the prioritisation of health and wellbeing, amongst others. Contemporary policy and research suggests that further alignments between Learning for Sustainability and outdoor provision are possible and probable. For these links to be made in practice, at this time of climate crisis and nature emergency will require a range of measures and supports. The evidence from this survey on, inter alia, outdoor provision, levels of staff confidence, and staff competence provides some direction for the prioritisation of these measures and supports.

Methodology

Research design

The survey set out to provide an understanding of the changing nature of the scope and range of formal outdoor experiences arranged by schools and pre-school centres. ‘One-off’ surveys of teacher beliefs or judgement of levels of provision would clearly provide inadequate data sets that would not be reliable or comparable between schools or between subsequent survey waves. Instead, our cross-sectional survey approach, replicated in 2006, 2014 and 2022, on outdoor provision is internationally distinctive in that it requires schools and pre-school centres to provide weekly updated records for each individual outdoor learning event both on and off school or pre-school centre sites with a record of its location, duration, focus, curriculum area, amongst other aspects. The design of the research is based on the view that teachers themselves are well placed to self-report on formal outdoor provisions. With data now available for 2006, 2014, and 2022, we have opportunity to look at changes across a range of measures including, for example, cost, location, and curricular focus. For further information on other elements of the research design, see also Mannion et al. (2015).

For the purposes of the survey, we took outdoor learning provisions to mean formally delivered educational experiences that took place outside the school building, capturing activity in the school grounds, in local areas and further afield, and residentiallywhether delivered by teachers or other staff. It should be noted that in 2022, residential trips and trips away in buses were rare or non-existent due to Covid restrictions. In early years settings, outdoor provisions captured time spent in the outdoors of the nursery as well as organised trips into the nursery grounds or offsite. The survey approach seeks to capture all outdoor educational activity across all subjects and interdisciplinary themes inclusive of play time in early years but not breaktime or PE in schools.

Survey instrument

The 2022 survey was developed through a sequence of pilots for validity, accuracy, user-friendliness and use in the digital platform. The survey went online for the first time in 2022 to make reporting easier including with the use of mobile devices. The instrument was piloted by research staff, individual teachers and selected settings ahead of time. For schools, the survey was time-limited, as in 2006 and 2014, and was conducted over an eight-week period in May and June ensuring comparability. In early years settings, as in 2014, we took a two-week window for data capture due to the nature of provision where there is often an easy flow of children indoors and outdoors over the period of the pre-school session.

Otherwise, in 2022, we re-used the same core elements of survey instruments used in 2006 and 2014 (see previous survey in 2014 for details here). This allowed us to make comparisons with past provision on the durations, types and locations of outdoor provisions, their associated purposes and foci, and how areas of deprivation were impacted. We also asked about the leadership of events, how costs were met, distance travelled from school, and the respondents’ views on engagement and enhancement of learning. As in past surveys, we did not survey for Physical Education or for activity at break times at school level. Schools were asked not to record track and field games or sports except for adventure sports (such as mountain biking or skiing). We included beach and seaside environments as a new option in the approach to location. We separately surveyed for ‘challenge’ and enjoyment’ where in the past these had been co-joined.

In 2022, we additionally asked respondents a number of new questions, asking them to self-report on the nature and extent of their professional learning and training in outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability and about their confidence levels in this provision. We also asked about respondents’ appraisal of whether provision had changed due to Covid.

Data collection process

After gaining local authority agreement, schools and early years centres were approached and asked to voluntarily participate as in 2014. Head teachers and individually responding teachers and early years practitioners were provided with survey information and gave consent via the online documentation. We assured participating establishments of anonymity in reporting. Uptake was lower for survey participation in 2022 than in 2014. 18 participating local authorities consented for us to approach schools and early learning and childcare settings, of these, returns were provided by settings across 16 local authority areas. 19 pre-schools and 34 primary schools consented to take part in the outdoor provision survey and provided returns. Just over 100 early years practitioners and school staff provided returns on their experience of professional learning. For secondary schools and ASN settings, participation was too low to report. It is worth noting that the sampling approach required voluntary participation. This means that interested establishments taking part possibly offered more outdoor provision than a non-voluntary sample. Indeed, in the evaluation of our survey, see Annex 3, five out of seven establishments suggested that their outdoor provision was likely greater than other similar settings that they were aware of.

Detailed advice on ‘what to survey’ was given to schools at the outset. Schools were provided with supportive live online and recorded workshops and some in-person advice. Schools were reminded regularly about the submission of returns online and were given support in this. Returns were captured directly onto digital databases via the online survey tool. We evaluated the process again in 2022 asking respondents about how confident they felt they had been in reporting. Most (71%) suggesting they were somewhat or extremely confident that all or nearly all outdoor activities had been captured in the survey, and that most (86%) found the digital survey easy to use.

Summary of Participants

Returns on the topic of professional learning were made from 108 teachers, from 58 schools and early years settings. See breakdown in table 1 below:

|

Settings |

Early Years |

Primary |

Secondary |

ASN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Practitioners (n) |

24 |

62 |

3 |

19 |

|

Schools (n) |

19 |

34 |

3 |

2 |

Of those who responded, 18.5% were early career practitioners (probationer-5 years), 50% were mid-career (6-17 years), and 31.5% were late-career (18-38 years).

|

Urban/Rural Classification |

Primary -Number of Schools |

Primary -Percentage (%) |

Early Years -Number of Settings |

Early Years -Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Urban |

12 |

35 |

11 |

58 |

|

Town |

5 |

15 |

2 |

10 |

|

Rural |

17 |

50 |

6 |

32 |

Participating establishments were located in urban and rural areas. Primary schools were located predominantly in rural (50%) and small town (15%) locations, while urban early years settings represented just over half (58%) of our sample. There were no settings found in large urban areas. A geographic spread was also evident, with participants from the central belt, southern and northern Scotland involved.

|

Returns/Year |

2006 |

2014 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Early Years Establishments (n) |

13 |

13 |

19 |

|

on-site |

121 |

243 |

71 |

|

off-site |

9 |

13 |

15 |

|

Primary Schools (n) |

8 |

26 |

25 |

|

Non-residential |

111 |

249 |

118 |

|

Residential |

2 |

9 |

1 |

|

Secondary Schools (n) |

9 |

14 |

2 |

|

Non-residential |

102 |

142 |

44 |

|

Residential |

14 |

36 |

0 |

|

ASN Settings (n) |

n/a |

n/a |

1 |

|

Non-residential |

n/a |

n/a |

17 |

|

Residential |

n/a |

n/a |

2 |

For early years settings, the number of establishments contributing has increased since 2014. The number of on-site activities recorded has reduced (243 in 2014 to 71 in 2022) and the number of off-site activities recorded has increase marginally. This is likely to be due to the online recording approach taken in 2022. For primary schools, while the number of schools contributing remained similar, the number of both on-site and off-site activities recorded were markedly reduced. The number of secondary schools contributing was reduced to 2, and there was 1 ASN setting contributing. Due to the small number of returns from secondary and ASN settings, only early years and primary school findings will be reported upon hereafter.

Settings in all SIMD quintiles were represented in our sample. For primary schools, in 2022 there were fewer participating schools from the lowest quintiles with 7.69% in the lowest and 19.23% in SIMD 2 compared with 19.23% and 23.08% in 2014. The majority of primary schools were in SIMD 4 (46.15%).

Findings

Section 1: Outdoor Learning Provisions

Duration of outdoor provision: Early Years

Early years practitioners were asked to record the number of children and the duration outdoors in their settings over two (non-consecutive) weeks during May and June 2022.

|

OL Provision/Year |

2006 |

2014 |

20222 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Outdoor learning hours (on-site) |

3246 |

3811 |

6520.5 |

|

Time at pre-school centres |

14105 |

10647 |

16657 |

|

Outdoor learning hours (off-site) |

n/a |

261.25 |

408 |

|

Percentage of day |

23% |

36% |

39% |

The overall time outdoors has increased for early years children since 2014. 39% of the day was spent outdoors for children in 2022 versus 36% in 2014 and 23% in 2006.

Duration of outdoor provision: Primary School

Primary school participants were asked to record the number of children and the duration of time outdoors for an eight-week period during May and June 2022.

|

(-) |

2006 |

2014 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Outdoor learning hours |

3390 |

22366 |

3539 |

|

Roll |

1343 |

5615 |

3559 |

|

Average hours per pupil during 8-week period |

2.52 |

3.98 |

0.99 |

|

Minutes/pupil/week (rounded) |

19 |

30 |

7 |

|

Not including residential |

n/a |

24 |

7 |

For primary schools, time spend outdoors was lower in 2022 than in both previous surveys. Our measure across all surveys for duration has been ‘per pupil, per week’. This was 7 minutes in 2022 for primary schools down from 30 minutes in 2014. Certainly, some of this reduction will be due to reduced residential visits (rendered impossible due to Covid). However, the non-residential figure for 2014 was 24 minutes. Hence, even after stripping out the time for residential provision, this represents a notable two thirds reduction in outdoor duration for pupils in 2022 compared to 2014. We select other aspects of the analysis below to explain some of this further reduction.

Practitioner confidence and outdoor provision

Outdoor learning duration is associated with practitioner confidence in our analysis – we report on this link in Section 2 (below).

Range of Duration Per Week and School Size

School roll size is also associated with outdoor learning duration. We noticed, as in previous years that a small number of schools provided a lot of outdoor events and that these high providers were generally smaller schools.

The range of time spent outdoors varied considerably across the settings in this survey. The shortest amount of time was 0.15minutes per pupil per week, with the longest 132 minutes per pupil per week. This is similar to the range found in 2014 (0.83 minutes per pupil per week – 142 minutes per pupil per week).

School Size. The mean roll in 2014 was 216 (rounded) with a median of 201, in 2022 this was a mean of 142 (rounded) with a median of 98. This suggests that the school size in the 2022 sample is notably smaller than that of 2014 sample.

The following scatter graph (figure 1) allows us to show an association between the size of the school and outdoor duration (average roll as per Scottish Government School Level Summary Statistics, 2021b).

In this survey, pupils spent less than 10 minutes outdoors (per pupil, per week) in schools with an average school roll of 202. However, for those who spent more than 10 minutes per week outdoors, the average school roll was 32. All children who spent more than 10 minutes outdoors had a school roll of less than 100. This indicates that, similar to the findings in 2014, smaller schools tend to provide more outdoor learning events.

Scatter plot showing the number of minutes spent outdoors per pupil, per week by school, sorted on the size of school. Y-axis shows the number of minutes per pupil per week, x-axis shows the schools (n=25) sorted by school size (<100 pupils, <200 pupils, >200 pupils).

Graph shows that the vast majority spent less than 20 minutes outdoors per pupil per week. Only those in the small schools (<100 pupils) spend more than 10 minutes per pupil, ranging from (rounded) 24 minutes to 132 minutes.

Areas of Deprivation and Outdoor Learning

Findings in surveys in 2014 and in 2022 show schools located in more deprived areas offer less outdoor provision. In our analysis here, we take event / trip / lesson duration as a quasi-measure of this phenomenon. We can see that the longest outdoor event duration is found in the highest SIMD quintile. [Quintile 1 represents schools located in the most deprived 20% of catchment areas and quintile 5 being in the least deprived.]

|

SIMD Quintile |

2014 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

1.8 |

0.7 |

|

2 |

0.8 |

1.7 |

|

3 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

|

4 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

|

5 |

2.7 |

1.8 |

Location of Outdoor Learning: Early years

Early years providers were asked to identify the location of all outdoor provision that the children were engaged in during the survey period.

|

Location |

2006 |

2014 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Within setting grounds |

90.80% |

94.80% |

85.06% |

|

Farm/Farmland |

0.60% |

0.80% |

1.15% |

|

Public park |

1.60% |

1.80% |

0% |

|

Urban/civic area |

4.50% |

0.80% |

1.15% |

|

Woods/forests/wildlife area |

2.50% |

2.40% |

12.64% |

Overall, we recall that early years outdoor learning duration has risen. In this sector, provision within the grounds remains the dominant location. Notable in 2022 is an over 5-fold increase in the proportion of outdoor learning taking place in woodland areas. This aligns with our perceived sense of sustained interest and training in the delivery of outdoor learning in woodland type environments by staff in this sector.

Location of Outdoor Learning: Primary

As in 2014, we surveyed for location of outdoor events. While the overall duration for primary schools per pupil per week has decreased, the table 8 (below) shows that the proportion of the total time for primary within school grounds has remained around the same level as 2014. Only one residential trip was logged, showing severe decline in residential provision, presumably due to Covid which resulted in the residential centres closing.

|

Location |

2006 |

2014 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Within School Grounds |

25% |

39% |

38% |

|

Beyond School Grounds |

60% |

36% |

55% |

|

Residential |

15% |

25% |

7% |

Only one residential trip was recorded in 2022, as such only non-residential figures will be reported hereunder. The single residential trip recorded was from a SIMD 2 (quintile) area, and reported 4 days of activities for 12 pupils, including hiking, mountain biking, high-ropes course and water sports. This resulted in 234 pupil-hours of activity and was from a small school (less than 100 pupils on the school roll).

The overall duration of outdoor provision is down. The increase in the proportion of lessons / events / visits ‘beyond the school grounds’ compared to 2014 suggests that, in the absence of residential provision, schools appear to have sought to provide outdoor learning events more locally.

Primary school teacher respondents were additionally asked to identify the type of setting utilised. The table below show the proportion of time and the average duration of time spent at each location type. Table 9 shows how proportions of total 'child hours’ differed across the two survey years.

|

Location Type |

2014 child-hours |

% |

2022 child-hours |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Beach/coastal |

n/a |

n/a |

93 |

3% |

|

Farmland |

228 |

1% |

91 |

3% |

|

Public park/garden/green space |

2461 |

15% |

402 |

12% |

|

School grounds |

8783 |

52% |

1353 |

41% |

|

Urban area |

2257 |

13% |

48 |

1% |

|

Wildlife area/Nature reserve/National park |

1910 |

11% |

44 |

1% |

|

Woodland |

955 |

6% |

594 |

18% |

|

Other |

194 |

1% |

680 |

21% |

|

total (rounded) |

16787 |

100% |

3305 |

100% |

Table 9 (above) shows that for many locations the durations of time spent in various locations went down from 2014, including farms and national parks and nature reserves. It was also reduced for ‘School Grounds’ activities, though this remained the top location for activities with 41% of events occurring there. The proportion of activities taking place in ‘Woodland’ areas has increased from 6% in 2014 to 18% in 2022 but time spent there is much reduced. 'Other’ activities such as urban visitor attractions were also visited proportionally more often in 2022 (21% in 2022 vs 1% in 2014). These mainly urban locations may have been sought out as a replacement for residential visits in 2022. This analysis provides another window on how time outdoors was both re-shaped and lost in 2022 compared to 2014.

|

Location Type |

2014 minutes per pupil (rounded) |

2022 minutes per pupil (rounded) |

|---|---|---|

|

Beach/coastal location |

n/a |

2 |

|

Farmland |

3 |

2 |

|

Public park/garden/greenspace |

29 |

7 |

|

School Grounds |

102 |

23 |

|

Urban area |

26 |

1 |

|

Wildlife Area/Nature Reserve/National Park |

22 |

1 |

|

Woodland |

11 |

10 |

|

Other |

2 |

11 |

|

Total roll |

5154 |

3559 |

Table 10 shows the minutes outdoors per pupil for all of the survey period (May and June) and compares 2014 with 2022. The data show how overall, the minutes spent outside per pupil has decreased in most settings, except 'other'. Time outdoors in woodland areas are relatively similar, despite the proportion of events spent in these areas increasing. We can surmise that it was local woodland which provided opportunity for sustained visitation here whereas further flung wildlife areas and national parkland became less accessible during Covid since transport would not allow adequate social distancing. School grounds, parks/gardens/greenspace locations exhibit similar average reductions in 2022.

Table 11 shows the duration of events, lessons or trips. Data show that for many locations the durations of events were stable for core categories (such as school grounds) but was reduced for locations beyond the local (such as farms and national parks / nature reserves). This analysis provides another window on how time outdoors was lost in 2022 compared to 2014; outdoor learning time beyond the grounds and beyond the local area was not only less common it was shorter in duration (for example via visits to farms and to national parks).

|

Location Type |

2014 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|

|

Beach/coastal location |

n/a |

1.3 (78) |

|

Farmland |

3.8 (228) |

2.6 (156) |

|

Public park/garden/greenspace |

1.8 (108) |

1.7 (102) |

|

School Grounds |

1.0 (60) |

0.9 (54) |

|

Urban area |

2.2 (132) |

2.1 (126) |

|

Wildlife Area/Nature Reserve/National Park |

4.0 (240) |

2.9 (174) |

|

Woodland |

3.0 (180) |

2.3 (138) |

|

Other |

n/a |

3.6 (216) |

[Note 1: We recorded ‘beach/coastal’ visits for the first time in 2022 as a new category.]

[Note 2: ‘Other’ locations included a sculpture garden, mixed locations (residential/semi-urban) and visitor ‘pay on entry’ attractions such as the Falkirk Wheel.]

Table 11 helps us understand something about how long outdoor lessons / visits lasted. Data analysis shows that school grounds events are, perhaps expectedly, shorter when compared to all other location types. Our analysis here is that compared to 2014 provision is down considerably, but two further changes are worth noting: firstly, the portfolio of outdoor locations visited in 2022 changed (with wildlife areas and national parks receiving less visits for example). Secondly, there are both fewer trips overall and these are, on average, shorter in duration in 2022.

Distance from school

Primary participants were asked to tell us how far from the school they travelled for the outdoor activities that they recorded.

|

Distance |

Events |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

On site |

66 |

56% |

|

up to 1km |

36 |

31% |

|

1-5km |

6 |

5% |

|

6-10 km |

3 |

3% |

|

10 km+ |

7 |

6% |

|

Total |

118 |

100% |

Table 12 (above) shows relative use of locations at various distances from school. Here, all non-residential events are considered.

In 2022, for 25 schools, we recorded 66 on site events. The figure for 2014 on site was 182 events for a similar 26 schools. We notice the sustained emphasis on grounds use and near-local areas (less than 6km) in primary schools with less than 10% going 6km or more in 2022. The majority of all non-residential, primary outdoor provision takes place in the school grounds or very close to the school. Compared to 2014, location spread is similar. 92% of events were on site or up to 5km away in 2014 and in 2022 combined.

Costs of Provision Outdoors

Participants were also asked to tell us how the costs of outdoor provision were met. Table 13 shows the breakdown of activity costs and how these were met.

|

Cost |

Events |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

no cost |

97 |

80% |

|

parent council |

6 |

5% |

|

school funds |

11 |

9% |

|

grant funding |

0 |

0% |

|

Pupils |

5 |

4% |

|

Other |

3 |

2% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

Note: more than one option could be picked which leads to total discrepancy - true total 118 events

As in 2014, the vast majority of outdoor activities were delivered at no cost, and those that did have a cost were covered by either the parent council or school funds, only a small proportion were directly paid for by parents or pupils. Further analysis showed that the activities paid for by parents/pupils or pupil council/school funds were mostly those activities that took place beyond the school grounds, such as visits to a sculpture garden or the Falkirk Wheel.

Focus of outdoor provision: Early years

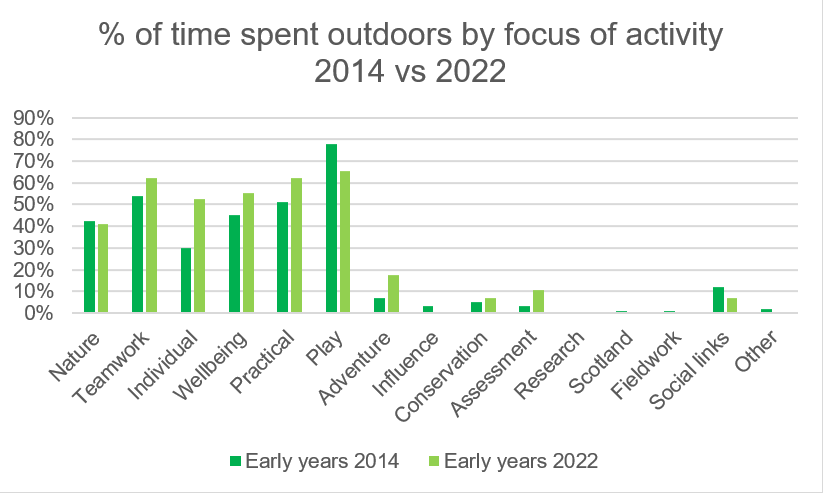

Bar chart showing the proportion of events under each focus in the 2014 and 2022 sample. Note that percentages do not add up to 100 as more than one option could be picked for the focus of activity.

There is some change in the focus of activity from 2014 to 2022. In 2014 the most cited focus was ‘play’. In 2022 it was also ‘play’, at around 65% of activities compared to around 80% in 2014. The percent spent focussed on ‘teamwork’ increased from just over 50% in 2014 to just over 60% in 2022. ‘Individual’, ‘wellbeing’ and ‘practical’ focus also increased in 2022 compared with 2014.

The substantial increase in the time spent focused on ‘individual’ growth and development is apparent in early years provision. This likely reflects sustained and perhaps increasing support for child-centred, child-led, self-directed or forms of free-choice outdoor learning in this sector. Whilst the profile of outdoor foci is mostly similar to that of 2014, proportionally less time was spent focusing on ‘play’ and ‘nature’ in 2022 (though overall time outdoors went up). Increases are found in activities focused on ‘wellbeing’, ‘adventure’, ‘teamwork’, ‘practical activities’, and also ‘assessment’.

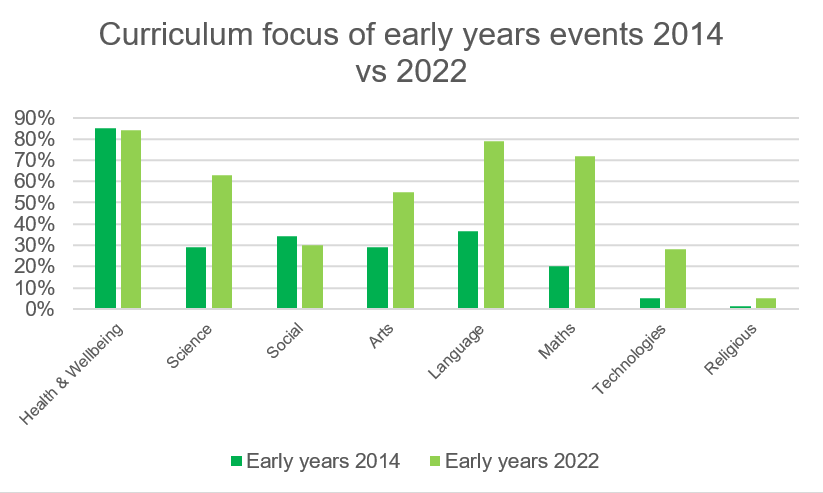

Bar chart showing the different curriculum foci of early years events in 2014 vs 2022. On the x-axis is the different curriculum foci (health & wellbeing, science, social sciences, arts, language, maths, technologies, and religious studies). On the y-axis is the proportion of events where the given curriculum foci was mentioned.

In both years, health and wellbeing was the most common focus of outdoor events. Social sciences went down slightly in 2022 (30% vs 24% in 2014), though all other foci increased. This may suggest outdoor learning was more varied in 2022 that 2014.

For curricular foci, we see in 2022 practitioners are utilising outdoor contexts for a wider variety of curriculum areas compared to 2014. ‘Health and wellbeing' remains the most popular curricular category for outdoor play and learning. However, there are notable increases in selections of ‘maths’, ‘language’, ‘arts’ and ‘science’, suggesting a substantial broadening of curricular connections made in relation to outdoor provision. This is likely occurring at least at times through play and / or through self-directed learning (given the data in figure 2).

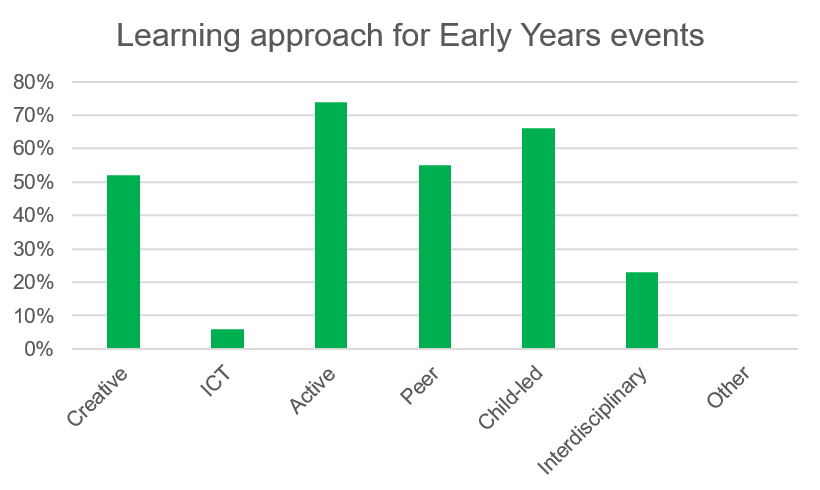

Bar chart showing the learning approach for the early years’ events. On the x-axis are the different learning approaches (creativity, ICT, active learning, peer learning, collaborative learning, Reggio Emilia (child-led), interdisciplinary, and ‘other’). On the y-axis are the proportion of events which used a given approach. Note more than one option can be chosen for an event therefore percentages will not sum to 100%.

The most cited approach was active learning, followed by child-led learning, and peer learning. No practitioner chose ‘other’, and of the chosen approaches, the least cited was ICT.

Active, creative, and child-led approaches are the most common, with ICT and interdisciplinary learning the least common approaches taken in early years outdoor events.

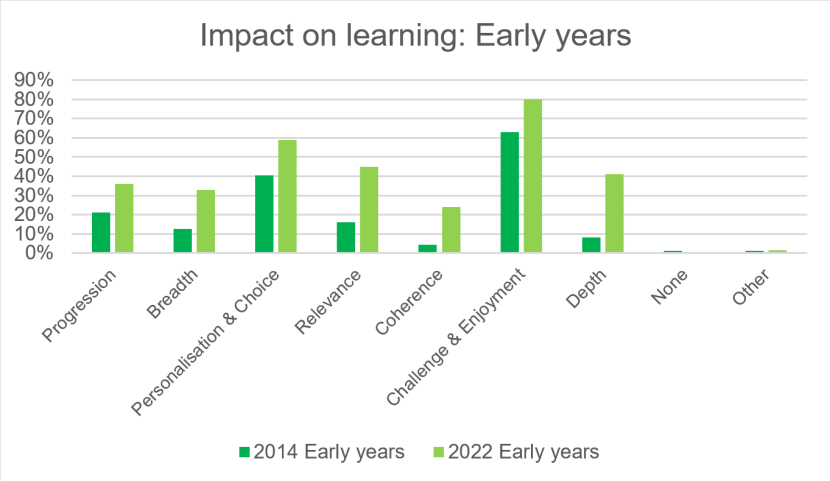

Bar chart showing impact on learning of the early years’ events. On the x-axis is the different types of impact on learning (progression, breadth, personalisation & choice, relevance, coherence, challenge & enjoyment, depth, none, and other). On the y-axis is the proportion of events practitioners assigned that impact to. Note that more than one option could be chosen therefore percentages do not sum to 100%.

The most cited impact on learning for early years events was challenge & enjoyment and then personalisation & choice, followed by relevance and depth. All identified impacts have increased since 2014.

We asked about whether each of the principles of Curriculum for Excellence (figure 5) had been enhanced by going outdoors. ‘Enjoyment’, ‘challenge’, ‘relevance’ and ‘depth’ are the most commonly noted enhancements via outdoor learning, with ‘personalisation/choice’ and ‘coherence’ somewhat receiving fewer mentions.

Focus of outdoor provision: Primary School

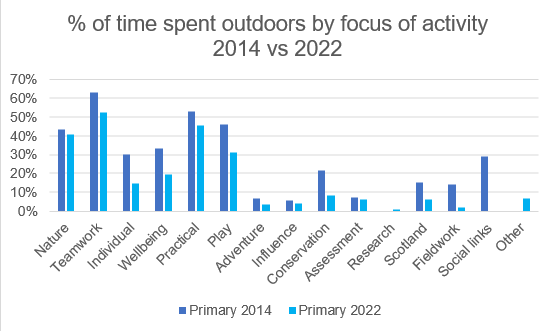

Bar chart showing the percentage of hours spent outdoors over focus of activity in the 2014 and 2022 sample. Note that percentages do not add up to 100 as more than one option could be picked for the focus of activity.

The figure suggests some change in the focus of activity from 2014 to 2022. In 2014 the most cited focus was ‘teamwork’ with just over 60% of hours, this reduced in 2022 just over 50% of the hours spent outdoors having the focus of ‘teamwork’ attached, thought it remained the highest cited focus. The time spent is down overall in 2022, with the exception of ‘other’, suggesting the focus may have narrowed now in comparison with 2014

For Primary school events, the most common focus categories were ‘teamwork’ and ‘practical activities’, ‘play’ and ‘nature’. Least important in these cases were research and fieldwork.

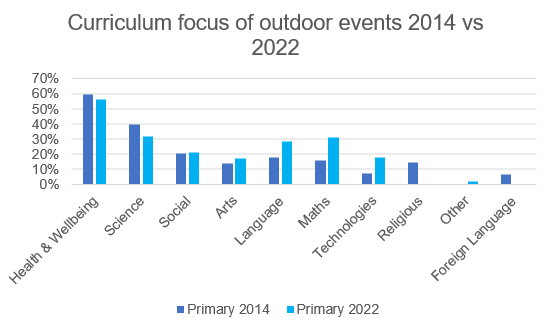

Bar chart showing the proportion of events where each curriculum foci was identified. On the x-axis is the different curriculum foci (health & wellbeing, science, social science, arts, language, maths, technologies, religious studies, other, and foreign language). On the y-axis is the proportion of events where the given foci was identified.

In both years, health & wellbeing was the focus mentioned most, though it went down slightly from 59% in 2014 to 56% in 2022. Science also slightly went down from 39% in 2014 to 32% in 2022. With the exception of religious studies and foreign languages which were not selected in 2022, all others increased. In particular maths and languages increased going from 16% and 19% in 2014 to 31% and 28% respectively. This goes some way towards suggesting a broadening of curricular connections made in relation to outdoor learning.

‘Health and wellbeing' remain the most popular curricular focus for outdoor provision. There are notable increases in reflections on maths, language, technologies and a small reduction in the proportion of events on science. This also goes some way towards suggesting a broadening of curricular connections made in relation to outdoor learning, however, not as broadly as the early years reflections.

Themes across Learning: Primary School

In primary schools, we asked respondents to identify whether the outdoor events connected to any of the CfE ‘themes across learning’. In 2014, these were ‘Enterprise in Education’, ‘Education for Citizenship’, ‘International Education’ and ‘Sustainable Development’. In 2022, the theme of ‘Learning for Sustainability’ replaced SD to reflect the changed policy context. In their responses, teachers identified Learning for Sustainability as linked to less than a third of events (28%). This is similar to 2014 figures for ‘Sustainable Development’. However, ‘Education for Citizenship’ as a theme shows a considerable reduction in the number of mentions in 2022 compared to 2014, from 25% in 2014 to only 8% in 2022. Many of the outdoor events described did not connect to these pre-identified themes, with many respondents choosing ‘none of these’ or ‘other’ when commenting on the theme of learning for the event.

Outdoor Learning Impacts

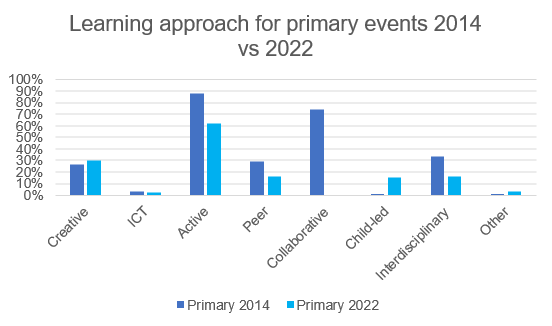

Primary staff were invited to connect their outdoor provision to CfE ‘approaches to learning’. Whilst outdoor learning was seen as enhancing or affording ‘active learning’, the collaborative dimension noted in 2014 has seen a reduction in mentions. Interdisciplinary approaches also saw a slight reduction. These changes in emphasis could be accounted for by new imperatives in the Covid period and the need to physically distance.

Bar chart showing the learning approaches identified for the primary events in survey years 2014 and 2022. On the x-axis are the different learning approaches (creativity, ICT, active learning, peer learning, collaborative learning, Reggio Emilia (child-led), interdisciplinary, and ‘other’). On the y-axis are the proportion of events which used a given approach. Note more than one option can be chosen for an event therefore percentages will not sum to 100%.

In both survey years the most cited approach was active learning. In 2014, the second highest cited approach was collaborative, however no practitioner chose this approach in 2022, perhaps due to Covid restrictions.

However, going outdoors tends to result in lessons being perceived by staff as generally active, creative and interdisciplinary approaches to learning in 2022.

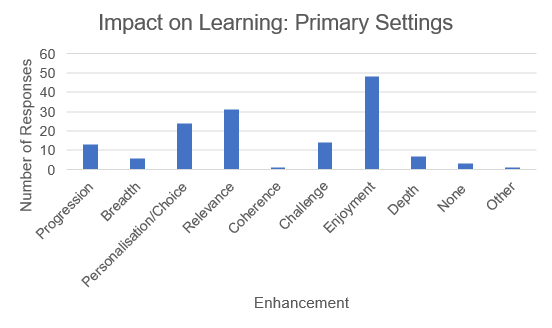

Bar chart showing impact on learning of the primary event. On the x-axis is the different types of impact on learning (progression, breadth, personalisation & choice, relevance, coherence, challenge, enjoyment, depth, none, and other). On the y-axis is the proportion of events practitioners assigned that impact to.

The most cited impact on learning for primary events was enjoyment followed by relevance, and personalisation & choice. Coherence and ‘other’ were not selected by any respondent.

Going outdoors appears, through the lens of teachers’ views, to create an enhancement of features of learning, in particular making learning more enjoyable and relevant. Enjoyment, relevance and personalisation/choice are the three most commonly reported enhancements of learning, with coherence and breadth being the less commonly reported. In 2022, we separated ‘challenge and enjoyment’ into two separate records and asked participants to select the enhancement that resonated most with them. Doing so means that we can notice that learning outdoors is seen to more commonly enhance ‘enjoyment’ but was less commonly connected to experiences of ‘challenge’. We also note that these enhancements can be understood to co-specify or coalesce. For example, the freedom to roam and choose activities outdoors could be connected to increased enjoyment, and the creation of relevance of tasks.

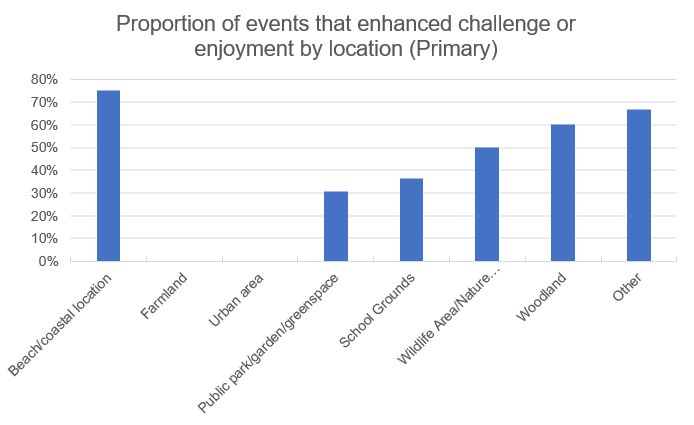

Bar chart showing the proportion of events, by location that were identified as enhancing challenge or enjoyment. On the x-axis is the different locations (beach/coastal location, farmland, urban area, public park/garden/greenspace, school grounds, wildlife area/nature reserve, woodland and other). On the y-axis is the proportion of practitioners that identified challenge or enjoyment as enhancements.

Beach/coastal locations have the highest identified enhancement with 75%, followed by other, woodland (60%) and wildlife areas/nature with 50% of events in these locations identified as enhancing challenge or enjoyment. Farmland and urban areas were not identified by any respondent.

The graph above (figure 10) suggests that many greenspaces were felt to enhance challenge or enjoyment for pupils. Over half of the outdoor events that took place in woodlands (9 out of 15 events) and bluespaces (3 out of 4 events) were felt to enhance challenge or enjoyment for pupils, while less than half of activities held in the school grounds (25 out of 69 events) were felt to offer the same enhancement. The data on engagement (below) relates.

Early Years Settings

|

Perceived Engagement |

% logs |

|---|---|

|

similar |

24% |

|

more engaged |

50.67% |

|

far more engaged |

25.33% |

Primary Schools

|

Perceived Engagement |

% logs |

Average duration in hours (mins) |

|---|---|---|

|

similar |

14.78% |

1.5 (90) |

|

more engaged |

57.39% |

1.6 (96) |

|

far more engaged |

27.83% |

1.2 (72) |

Participants reported that events in outdoor settings enhanced engagement more than similar lessons indoors, in line with 2014 results. Learner engagement is reported as enhanced across all location types (tables 14 and 15). When engagement is considered across the locations of outdoor provision (table 16), it is clear that pupils are considered to be ‘more’ or ‘far more’ engaged across all outdoor locations.

|

Location |

(Number) and % that said ‘more’ or ‘far more’ engaged |

Total number of events |

|---|---|---|

|

Beach/coastal location |

(5) 100% |

5 |

|

Farmland |

(2) 100% |

2 |

|

Other |

(6) 100% |

6 |

|

Urban area |

(3) 100% |

3 |

|

Wildlife Area/Nature Reserves/National Park |

(2) 100% |

2 |

|

Woodland |

(14) 88% |

16 |

|

School Grounds |

(59) 84% |

70 |

|

Public park/garden/greenspace |

(10) 71% |

14 |

Section 2: Practitioner Confidence and Professional Learning

Professional confidence in outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability

Participants were asked how confident they were with taking learning outdoors and with delivery of Learning for Sustainability, as well as training they had received regarding these. Participants across both settings reported feeling confident in outdoor learning. Confidence was somewhat higher for early years practitioners, with 9 out of 10 participants here suggesting they have some confidence taking learning outdoors. Confidence in Learning for Sustainability was reported to be lower in both settings, in primary settings in particular, less than half of our participants reported that they were confident in Learning for Sustainability.

|

Setting |

Confident taking learning outdoors |

Confident in Learning for Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

|

Early years |

91.67% |

70.83% |

|

Primary |

62.90% |

40.32% |

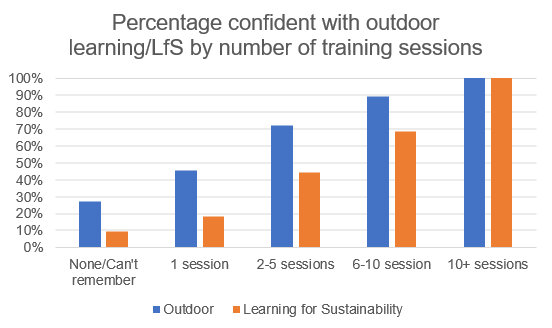

It was found that the proportion of those who were confident with outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability increased with training provision (figure 11). Respondents reported on the number of ‘sessions’ which was taken to mean a half day input or similar. When participants received 6-10 ‘sessions’, a high majority were confident with both outdoor learning (89%) and Learning for Sustainability (68%). When participants had received 10+ ‘professional learning’ sessions, all reported feeling confident with taking learning outdoors, and delivering Learning for Sustainability (n=13).

Bar chart showing the proportion of participants confident in taking outdoor learning/Learning for Sustainability by the number of professional learning sessions taken. On the x-axis is the number of professional learning sessions completed (none/can’t remember, 1 session, 2-5 sessions, 6-10 sessions, and 10+ sessions) and on the y-axis the percentage who answered ‘confident’ or ‘very confident’ to the questions on taking learning outdoors/Learning for Sustainability.

Bars indicate that participants were more confident in taking outdoor learning than taking Learning for Sustainability. For both types of learning, the proportion who were confident increased as the number of training sessions increased. By 10+ sessions 100% of participants reported being confident in both outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability.

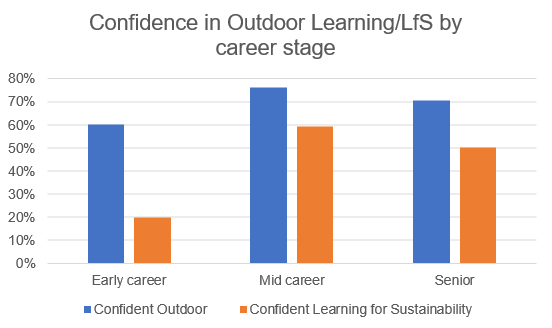

Confidence also differed by career stage, with mid-career practitioners being the most confident across both settings, see figure 12 below.

Bar chart showing the proportion of participants confident in taking outdoor learning/Learning for Sustainability by career stage. On the x-axis is the career stage (early career, mid-career, senior) and on the y-axis the percentage who answered ‘confident’ or ‘very confident’ to the questions on taking learning outdoors/Learning for Sustainability.

Bars indicate that participants at all career stages were more confident in taking learning outdoors than in Learning for Sustainability. For both type of learning, participants in the mid stage reported being confident in the highest proportions, while early career practitioners reported being confident in the lowest proportions.

These findings suggest that early career and senior stage practitioners could most benefit from increased professional learning provision relating to both outdoor learning and Learning for Sustainability. However, we can also suggest that all educators would benefit from robust progressive pre- and in-service education and professional learning involving 10 or more linked ‘sessions’.

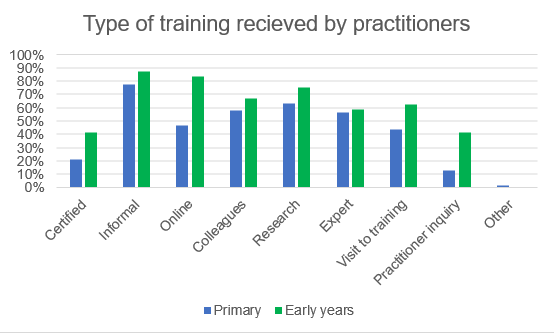

Bar chart showing the proportion of respondents who received each type of professional learning. On the x-axis is the different types of professional learning (certified, informal, online, colleagues, research, expert, visit to training, practitioner inquiry, or other). On the y-axis is the percentage of respondents who received the given type of professional learning in their career.

The bars show that for both early years and primary school practitioners, informal professional learning is the most common. It also shows that certified professional learning is the least common. Early years practitioners reported online and practitioner inquiry professional learning sessions in higher proportions than primary practitioners (83% vs 47% and 42% vs 13% respectively).

Informal professional learning opportunities, such as learning from or observing peers, alongside online provision was the most common professional learning received by participants. Practitioner enquiry and certificated/formal professional learning was least commonly received.

Practitioner confidence and outdoor provision

Duration outdoors for the establishment is associated with individual practitioner confidence in our analysis. The average pupil-hours (see Section 1) were higher in schools where staff stated they were confident compared to those who were not (198 rounded hours versus 50 rounded hours). Thus, higher confidence is associated with a considerable increase in provision. A similar association is found for Learning for Sustainability. Interestingly, individual practitioners who reported they were confident in delivering Learning for Sustainability reported higher average outdoor pupil-hours for their whole school than those who did not (222 rounded hours vs 78 rounded hours) suggesting individual practitioner confidence possible support mechanisms at work between whole-school contexts, individual practice, and levels of training.

Section 3: Perception of Provision Post-Covid

Perceived changes in provision

Participants were asked to comment on any perceived impact of the pandemic on outdoor provision in their settings.

|

Setting |

reduced |

same |

increased |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Early Years |

3 |

7 |

14 |

|

% |

12.50% |

29.17% |

58.33% |

|

Primary |

5 |

19 |

37 |

|

% |

8.20% |

31.15% |

60.66% |

Just over half of participants believed that their outdoor provision increased in comparison with pre-pandemic levels.

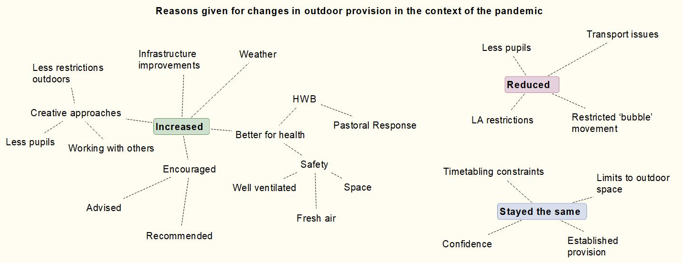

There are three categories of changed provision in the context of the pandemic, increased, stayed the same and decreased. In the responses from participants who perceived an increase, they gave weather, infrastructure improvements, creative approaches, encouragement and health benefits as their reasons. For those who suggested that outdoor provision had stayed the same, they stated confidence, timetabling constraints, limits to outdoor space and existing, established provision as their main reasons. Finally, for the participants who suggested provision had fallen, they suggested lower numbers of pupils in school, local authority restrictions, transport issues and restrictions on pupil movement due to ‘bubble’ structures as their main reasons.

Reasons for perceived increased provision post-Covid

Respondents noted how outdoor spaces were seen as better for the health of pupils. These comments referred to the benefits of fresh air, space and adequate ventilation in limiting the spread of Covid. There were also references to pastoral care and health and wellbeing more broadly.

Staff often referred to how they had been encouraged to go outdoors more by other staff from school and at local authority level. This suggests that the nudge-like impetus to go outdoors had a supportive effect on provision. One participant suggested that while provision had increased early in the pandemic, it had fallen back to normal as a result of staff confidence levels.

Creative approaches to learning were associated with taking pupils outdoors, which enabled small groups and classes to work together in ways that were not possible indoors. Also, having fewer pupils in school during periods of the pandemic enabled outdoor provision to be easier. Good weather and improved infrastructure also increased provision according to reports here.

Reasons given for reduced provision

Various forms of restrictions were found to reduce provision. For example, limitations were placed on group size. Restrictions on pupil movement meant that outdoor provision became more challenging for some settings.

At times, pupils were obliged to spend time learning at home which of course reduced scheduled outdoor learning via school. Some schools provided outdoor learning tasks which were offered to pupils learning at home and these were found to be somewhat successful given the situation.

Reasons given for provision staying the same

For some, existing provision was felt to be of a high-quality and this did not change due to Covid. For others, the desire to increase outdoor learning was prevented or limited by inadequate infrastructure (e.g. physical spaces) or through timetabling.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This third survey of outdoor provision in Scotland allows for some comparisons across the two sectors for which data were forthcoming: early years and primary schools and between surveys (in 2006, 2014, 2022). We can also reflect on the analysis of professional learning experience of the 100+ practitioner/teacher respondents.

Early Years

In early years, the increase in duration is noticeable across the three survey dates (2006, 2014, 2022). Many factors are in play here. This increase can partly be understood as connected to practitioners’ reported confidence levels and professional learning opportunities which were higher than in primary. In addition, early years experts report that outdoor woodland professional learning for early years practitioners has become quite commonplace. Relatedly, we note increased early years provision in woodland in our survey.

In tandem, we see that outdoor learning and play is now more culturally expected as a norm than in 2014 by most staff and parents. In the early years sector, there are now cultural expectations, policy imperatives around outdoor learning and play. There is also considerable sectoral growth, funding, and professional learning opportunities (pre- and in-service) all of which align to support practitioners in outdoor provision.

Primary Schools