NatureScot Research Report 1296 - Learning in Local Greenspace - an evaluation report

Year of publication: 2022

Authors: Munro, S.A. (NatureScot)

Cite as: Munro, S.A. 2022. Learning in Local Greenspace - an evaluation report. NatureScot Research Report No.1296.

‘I love these outdoor adventures and learning about all the plants and animals, It’s our job to look after them’ – Primary pupil, Fife

Keywords

Outdoor learning; greenspace; school; disadvantaged areas; nature connection; collaboration; biodiversity strategy

Background

Learning in Local Greenspace (LILG) was a project that arose from Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 2020. This collaborative project was initiated and led by NatureScot and involved many partners over the course of its implementation from 2015-2020.

The LILG project supported schools in some of the most disadvantaged areas of Scotland to identify and use a local greenspace for outdoor learning. The approach identified and removed barriers to outdoor learning and helped build teachers’ confidence to take learning outdoors regularly in their local greenspaces. The overall intention was to embed outdoor learning in regular teaching practice at the project schools.

The project took an innovative approach of bringing partners together to support schools in a strategic co-ordinated way over a sustained period of time. It supported 115 schools (94 primary, 16 secondary and 5 additional support needs schools) across 12 local authorities and engaged over 6000 pupils and more than 500 teachers. It achieved this despite its modest budget, which translated into an average of just over £3,400 per school over the life time of the project.

Despite being considerably affected by the global pandemic in its final year, the project successfully met its aim to ‘Increase secondary and primary schools’ access to greenspace and nature for outdoor learning as part of the wider ‘Learning for Sustainability’ agenda.’ It also exceeded its target of ‘100 schools in the 20% most disadvantaged areas across Scotland have access to quality greenspace for outdoor learning’ with 115 eligible schools taking part in the project. In addition, at least a further 32 schools benefitted from some support through the project.

NatureScot is using the learning from this project to develop its future support for outdoor learning.

Main findings

- Good progress was made on reducing barriers to outdoor learning

- The percentage of teachers taking learning outdoors in their local greenspace and school grounds on a fairly regular/very regular basis has risen by 21 percentage points and 31 percentage points respectively

- The percentage of teachers feeling fairly or very confident has improved by 31 percentage points

- The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils’ connection to nature is good or excellent has risen by 18 percentage points

- The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils engagement in learning outdoors is good or excellent has risen by 23 percentage points

- Local greenspaces have been improved for local communities and their biodiversity enhanced

- A suite of resources to support outdoor learning has been developed

- The project has helped partner organisations to work more collaboratively to support outdoor learning in a more strategic way and changed their view of the value of using local greenspaces for outdoor learning

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the partners that collaborated with us to develop this project. We would also like to thank the many partners, local authority departments, community groups, parents and volunteers that helped support the schools either directly or indirectly in their outdoor learning in their local greenspaces. We are grateful for all the funders that match funded our partners that made this work possible. Lastly we would like to thank all the schools for taking a leap of faith to take their learning off site and into a local greenspace and for all their hard work and enthusiasm.

Abbreviations

Career Long Professional Learning (CLPL)

Geographical Information Systems (GIS)

General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS)

Independent Deeper Project Evaluation (IDPE)

Learning in Local Greenspace (LILG)

Open Air Laboratories (OPAL)

Outdoor Learning in Nature (OLIN)

Introduction

Learning in Local Greenspace (LILG) was a project that arose from Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 2020. This partnership project was initiated and led by NatureScot but involved many partners over the course of its implementation from 2015-2020, though because of the pandemic, work with some schools continued into early 2021.

The details specified in Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 2020 are as follows:

Big Step 3 - Quality greenspace for health and education benefits

Outcome: Improved health and quality of life for the people of Scotland, through investment in the care of greenspace, nature and landscapes.

Priority Project 6: Taking Learning Outdoors

Aim: Increase secondary and primary schools’ access to greenspace and nature for outdoor learning as part of the wider ‘Learning for Sustainability’ agenda.

Target: 100 schools in the 20% most disadvantaged areas across Scotland have access to quality greenspace for outdoor learning.

The LILG project got pupils learning regularly in their local greenspaces close to their schools and helped build teachers’ confidence to take learning outdoors. The overall aim of the project was to support schools to identify and use a local greenspace over a sustained period of time in order to embed outdoor learning in regular teaching practice. It focussed in disadvantaged areas across Scotland, supporting 115 schools (94 primary, 16 secondary and 5 additional support needs schools) across 12 local authorities and engaging over 6000 pupils and more than 500 teachers.

This report provides an overview of the project, the outcomes, the main findings and lessons learned for supporting outdoor learning in Scotland in the future.

‘We have been wanting to use that greenspace for years. There have been several times that we went and looked at it closely, but we were always a bit unsure of it. It’s been great to be able to utilise such a good space, especially as it is right on our doorstep.’ – Primary School Teacher, West Lothian

Context

Outdoor learning has been shown to have many positive outcomes. It can improve health and wellbeing, improve behaviour and engagement in learning which in turn can lead to improvements in attainment. As well as being a great platform for learning everything from maths and literacy to science, social subjects and expressive arts. Pretty much anything can be taught outside in the best classroom of them all – nature.

Outdoor Learning has been an explicit part of our curriculum since the publication of Curriculum for Excellence through Outdoor Learning in 2010 and a formal requirement of teachers, as a part of Learning for Sustainability, since 2013 through the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) Standards for teachers. A specific ambition for this project was to provide support for teachers to help them deliver good quality outdoor learning experiences in nature for pupils at all stages, as part of a place-based progression.

The Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 2020 also highlights a number of key pressures on biodiversity which are also highly relevant to the genesis of the project including:

- Disconnection with nature

- Lack of recognition of the value of nature

- Climate change

People’s disconnection from nature often leads to a lack of recognition of the value of nature and therefore can impact on the lifestyle choices made by people which ultimately can accelerate climate change. It has been shown that by immersing young people in nature on a regular basis it can foster a connection to nature and they can grow to value it. This is often taken forward into adulthood which can influence pro-environmental and pro-conservation behaviours which will be needed to tackle the linked emergencies of climate change and biodiversity loss. The recent Dasgupta Review highlighted our failing and unsustainable relationship with nature. It concludes that “Every child in every country is owed the teaching of natural history, to be introduced to the awe and wonder of the natural world, and to appreciate how it contributes to our lives.” (Dasgupta, 2021, p. 498). What better way to achieve this than through getting young people out into a local greenspace on a regular basis for their lessons?

In addition to tackling the climate and biodiversity emergencies, this project has heightened the awareness of the importance of being in nature for health and wellbeing. The last year of the project took place during a global pandemic. Whilst this put the brakes on the project due to lockdown restrictions, lockdown found many ordinary people rediscovering the restorative power of nature as families and individuals alike sought solace in walks in their local greenspace. When restrictions were lifted sufficiently, many of our schools were quick to get their young people back out into their local greenspace where local restrictions allowed, both for the benefit of pupil and teacher wellbeing.

‘I don’t feel as stressed when I am out but when I am in class I get stressed.’ Primary pupil, West Dunbartonshire

Project Overview

Objectives and scope

Six objectives were established in a co-design process with partners. These were:

- To identify and remove the specific barriers (perceived or actual) to a school undertaking quality outdoor learning across a range of curricular areas on a regular and frequent basis

- To ensure interventions with the schools are self-sustaining into the future

- To improve the health and quality of life for the pupils attending the target schools

- To raise attainment in target schools

- To improve local greenspaces for local communities and enhance biodiversity

- To safeguard the legacy of the project

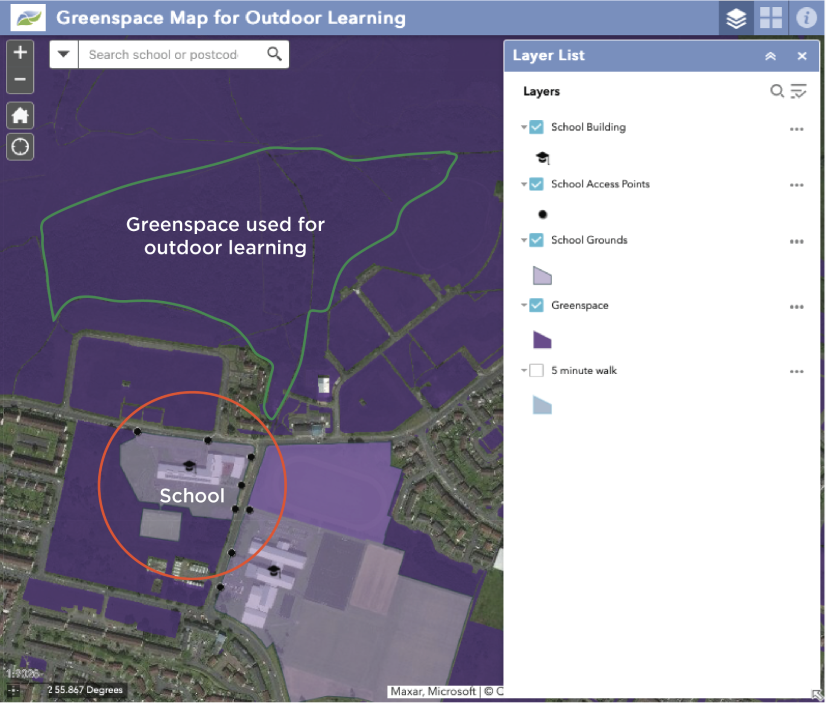

During the project initiation in 2015, an initial Geographic Information System (GIS) feasibility study was conducted to look at the available data on proximity of greenspace that could potentially be used for outdoor learning for schools serving the most disadvantaged areas of Scotland. This exercise helped us set definitions and explore the logistics of the project. It also sowed the seed for one of our legacy resources – The Greenspace Map for Outdoor Learning. A small pilot exercise in West Dunbartonshire also helped us test the data and definitions and explore possible approaches.

We started to engage partners in the development of the project by inviting a wide range of stakeholders actively involved in outdoor learning in Scotland to attend a partner engagement workshop in September 2015. At the event we discussed the Scotland’s Biodiversity Route Map project, looked at our findings from the GIS analysis and the West Dunbartonshire pilot and started to explore how we might be able to work together to achieve the target. The workshop had a positive reception and we followed it up with a series of one-to-one meetings with the various stakeholders to look for potential synergies between what they were doing to support outdoor learning and what we were wanting to achieve through the Learning in Local Greenspace project. A second stakeholder workshop was held in February 2016 - a partner project planning workshop - to explore how the project could be implemented in practice.

Governance

A National Steering Group was formed to shape the project and get stakeholders on board. Representatives were from NatureScot, Education Scotland, Learning through Landscapes (formerly Grounds for Learning), Scottish Forestry (formerly Forestry Commission Scotland), National Trust for Scotland, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Conservation Volunteers, John Muir Trust and East Ayrshire Council.

Project funding

For the first years of the project, partner support were managed through negotiating clauses into existing funding agreements with partners. This changed in 2018 when NatureScot moved its funding structure away from separate framework agreements towards a challenge fund model. The new Outdoor Learning in Nature (OLIN) Challenge Fund opened for two rounds of applications in 2018. The majority of the successful OLIN projects were adopted into the LILG project.

The OLIN Fund provided £390,500 for 18 projects contributing to LiLG. While these 18 projects worked with at least 147 schools, greatest effort was focused on the 115 project schools that had been identified. The total spend of the OLIN fund for each of the 147 schools averages out to £2,656 per school. In reality, this figure will be closer to £3000 per school for the 115 project schools that had the greater intervention.

In addition to the OLIN funding, there was a separate project budget to spend on such items as seed fund, school resources, resource development, workshops and events. The total project budget spent was £47,797. On average, the project budget per school was the equivalent of £416 per project school over the course of the project.

Overall, the average project cost was therefore in the order of £3,400 per school. This excludes NatureScot staffing costs and match funding sourced by project partners.

Project partners

We worked with a variety of partners throughout this project. Some of the partners were involved for the first few years, some came on board once the new OLIN challenge fund started and some were involved throughout. Initially we worked with the following partners to develop and establish the project:

- Education Scotland

- Forestry and Land Scotland (community rangers)

- John Muir Trust

- Learning through Landscapes

- Learning Outdoors Support Team (LOST) East Ayrshire Council

- National Trust for Scotland

- Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

- Scottish Forestry (education)

- The Conservation Volunteers

Once the Outdoor Learning in Nature (OLIN) fund was established we worked with 18 OLIN partners to deliver the project. The OLIN funded partners and projects involved in the LiLG project can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. OLIN partners and OLIN projects involved in the LILG project

| Organisation | OLIN Project |

|---|---|

|

Aigas Trust |

Nature days: Pay it Forward Project |

|

Arts and Communities Council and Rock Solid |

Dundee Learning in Nature |

|

Beasties, Bugs and Bairns |

Make IT Wild |

|

City of Edinburgh Council |

The Outdoor Learning Map |

|

Edinburgh and Lothian’s Greenspace Trust |

Learning in Edinburgh Local Greenspace |

|

FrogLife |

Springburn Partnership |

|

Jupiter Artland Foundation |

Orbit |

|

Learning through Landscapes |

Learning in Local Greenspace |

|

North Ayr Cluster of Schools (South Ayrshire Council) |

North Ayr School Cluster |

|

Royal Caledonian Horticultural Society |

Grow and Learn in Nature |

|

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds |

Let Glasgow Flourish |

|

Seven Lochs |

Outdoor Learning @ Seven Lochs |

|

South Lanarkshire Council |

Growing Up Wild |

|

The Ecology Centre |

Muddy Books |

|

The Leamy Foundation |

Learn and Grow |

|

Under The Trees |

Nature's Ambassadors 2018/20 |

|

Urban Roots |

Southside Schools Digging into Nature |

|

Youth Vision |

Learning in Forests |

Rollout of the project

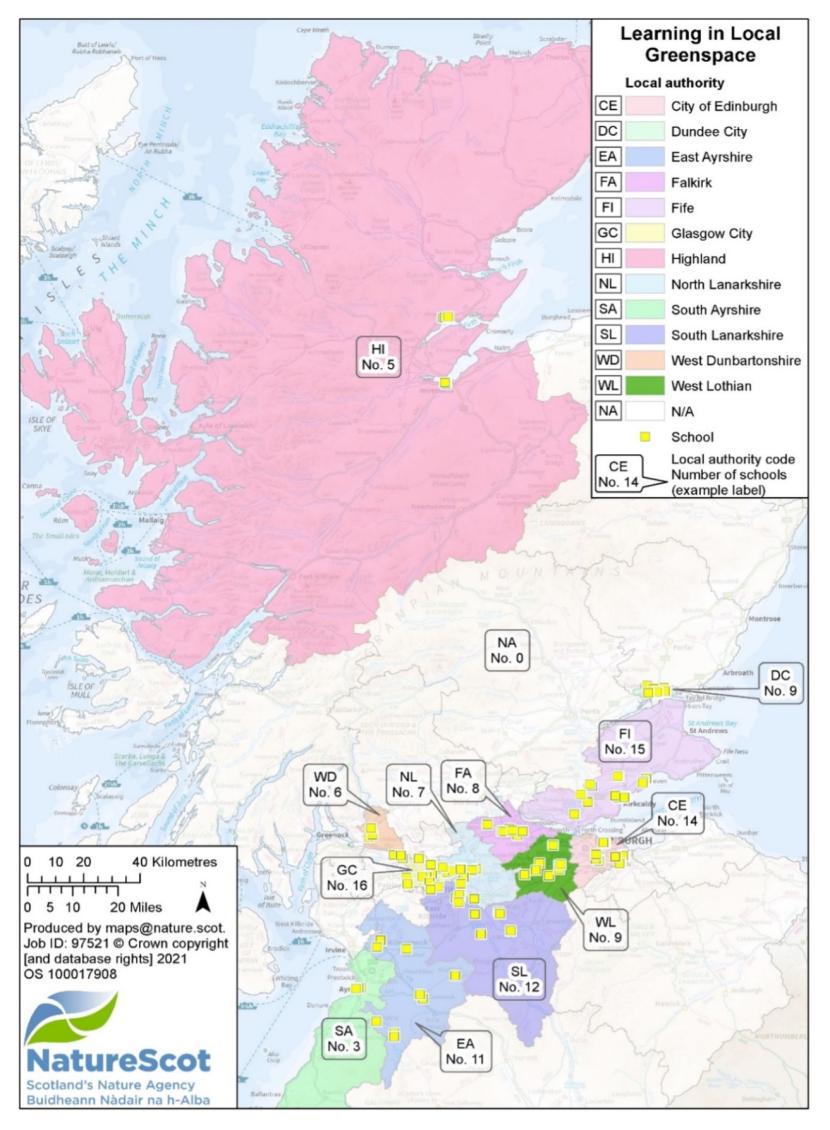

Officially 115 schools signed up to the project from 12 different local authorities (see Figure 3 for the location of the schools). These consisted of 94 primary schools, 16 secondary schools and 5 additional support needs schools. A full breakdown can be seen in Table 2.

| Local Authority | Primary | Secondary | Supported | Total Schools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dundee |

6 |

3 |

0 |

9 |

|

East Ayrshire |

10 |

0 |

1 |

11 |

|

Edinburgh |

10 |

3 |

1 |

14 |

|

Falkirk |

8 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

Fife |

13 |

1 |

1 |

15 |

|

Glasgow |

11 |

5 |

0 |

16 |

|

Highland |

5 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

North Lanarkshire |

5 |

2 |

0 |

7 |

|

South Ayrshire |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

South Lanarkshire |

8 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

West Dunbartonshire |

6 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

West Lothian |

9 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

Total |

94 |

16 |

5 |

115 |

Getting schools to sign up took time. Initially it was slow to achieve the numbers we had set ourselves. This was in part due to the iterative nature of developing the project and partly because schools were nervous about ‘signing up’ to something. However, once the OLIN funding was established we quickly met our target through the two rounds of the programme.

The map shows mainland Scotland divided into local authority areas. Each local authority where schools took part in the project are highlighted in a different colour.

The location of the project schools are marked by yellow squares. The distribution of the schools is shown to be predominantly across the Central Belt of Scotland, with further clusters in Dundee and north east Highland.

In addition, labels pointing to each of the 12 local authorities involved in the project show the number of schools that participated. These are:

City of Edinburgh: 14

Dundee City: 9

East Ayrshire: 11

Falkirk: 8

Fife: 15

Glasgow City: 16

Highland: 5

North Lanarkshire: 7

South Ayrshire: 3

South Lanarkshire: 12

West Dunbartonshire: 6

West Lothian: 9

The 115 schools that signed up to the project received a basic ‘goodies’ pack of resources to help support their outdoor learning. This generally consisted of:

- A class pack of 10 laminated Open Air Laboratories (OPAL) survey packs

- A class pack of 30 LiLG magnifying glasses

- A minimum of two LiLG bags for helping to transport outdoor learning equipment between the school and the greenspace

There was some local variation on distribution of resources depending on the discretion of the partners involved in helping with this. Some spare resources were also distributed at events and the plan was to do more of this before Covid intervened.

In addition, each school was offered a £250 seed fund with which they could buy outdoor learning equipment or resources of their choice. For example it could be spent on wellies, waterproofs, field equipment, survey resources etc.

A total of 98 schools accepted the seed fund. That is a total of £24,500 spent on outdoor learning equipment and resources through this means. Some opted not to take the seed fund due to the additional paperwork involved.

As well as the resource ‘goodies’ pack and seed fund, the schools were pointed to our online project resource, Beyond Your Boundary – easy steps to learning in local greenspace and its associated supporting documents (a greenspace audit, a questionnaire to inform the action plan and an action plan template). The schools were also kept in touch with the project via a regular project newsletter. In addition all the schools received a certificate at the end of the project.

Through the course of the project, NatureScot ran a number of events and opportunities to engage and support partners and schools. These included:

- Annual Partner Workshop (2015 - 2018)

- Sharing Practice Event (April 2019)

- Camera Trap Competition (Autumn 2019)

- Let’s make a difference for the planet! (November 2019)

- End of project webinar (November 2020)

School support from partners broadly fell into two categories:

- Supported sessions

- Career Long Professional Learning (CLPL)

Supported sessions were where a partner would take a class or group of pupils, along with their teacher, to the local greenspace and lead an outdoor learning session. Generally there would be consultation and planning session with the teacher ahead of the lesson. The lessons themselves would be an opportunity for the teacher to learn how to manage the group on the walk to the site and throughout the lesson and use the greenspace to its best advantage. They could also pick up ideas for other lessons. The partner would encourage a teacher to gradually take more of the lesson over a period of time as their confidence grew.

CLPL took various forms. It could be more informally in the planning meeting for the supported sessions as outlined above, or as a twilight session or whole day formal event for several teachers. During the pandemic these were done in a virtual online format.

Covid-19

It cannot be overstated what an impact Covid-19 had on the project. It clearly affected almost all of the objectives and is likely to have a big impact on outdoor learning for some time to come due to the added barriers that it presents through stringent Covid restrictions.

One of the main impacts was the closure of schools and move to home learning. This immediately stopped all outdoor learning and all support from OLIN partners ceased. Gradually as partners and schools began to take stock of the situation, some limited support was again provided to schools where possible. These largely included the development of online resources or virtual CLPL. Even when pupils returned to school, partners were largely unable to pick up where they had left off (e.g. by continuing supported sessions and face-to-face CLPL), due to stringent restrictions put in place by local authorities. In response to the situation, NatureScot worked with OLIN partners to amend the expectations of the Funding Agreements and extend the terms of the agreements where necessary to March 2021.

2020 was going to be the ‘grand finale’ of the project. With all the schools signed up NatureScot had planned several large scale events including a camera trap prize giving and various regional celebration events for school. In the end these were reduced down to ‘virtual’ events. A ‘virtual’ prize giving for the schools taking part in the camera trap competition was devised instead. The celebration events were reduced down to a single webinar giving a snapshot of some of the activity that had taken place during the course of the project.

Clearly the pandemic effected everyone’s health and wellbeing to a greater or lesser extent, with concerns that it will also have increased some of the deep seated inequalities we see in Scotland. The eligible schools taking part in this project were all serving some of Scotland’s most disadvantaged areas, so support has been targeted at the right areas. Nevertheless, it was always likely that several of the objectives of the project would be significantly adversely affected by the pandemic, not least the objectives, ‘to improve the health and quality of life for the pupils attending the target schools’ and, ‘to raise attainment in target schools’.

‘I feel calm, free and not enclosed.’ Primary pupil, West Dunbartonshire

Evaluation

The evaluation of the project had two strands:

- The project evaluation that was set up at the start of the project which was based on a short, simple set of questions that would be asked of a sample of teachers from each participating school at the beginning and end of the project.

- An independent deeper project evaluation (referred to as the IDPE throughout) that was conducted by Walter Patterson Consultancy, 2021 (unpublished). The consultancy interviewed a teacher from a small sample of schools and 18 partners at the end of the project to capture their views of the project.

In addition, other sources such as OLIN reports and project information gathered over the course of the project have also been drawn on to provide insight and ‘colour’ to supplement the findings of the two formal evaluations. Each of these strands were used to assess the extent to which the objectives and outcomes had been met through the project.

The evaluation of the project was also impacted by the global pandemic. Teachers were under immense pressure during the post-project evaluation which meant we did not get as many responses as we had hoped. As a result the original plan of conducting a statistical analysis of the project evaluation results was not possible as the sample size was too small. The project evaluation is therefore presented as a simple comparison of percentages.

What has been delivered and why does it matter?

The project met and exceeded its target with 115 eligible schools taking part and a good deal more (at least a further 32 schools) also benefitting from support. Key outcomes from this work are summarised below with key findings from the evaluation presented in the next section.

Supporting schools serving disadvantaged areas

The project has worked with at least 115 schools serving some of Scotland’s most disadvantaged areas. This has opened up free, often untapped, rich teaching assets for these schools to use – local greenspaces. We have provided resources and support to these schools over a sustained period of time in order to embed a culture of outdoor learning at these schools.

Supporting teachers

The project has worked with at least 500 teachers. These teachers will take their learning forward and teach many other pupils over the course of their careers in outdoor settings. It is hoped those teachers that have realised the power of outdoor learning will help support other colleagues in their current school and in any other school they move to in the future in their outdoor learning practice.

- The percentage of teachers feeling fairly or very confident has improved by 31 percentage points (baseline 54%, post-project 85%)

- The percentage of teachers taking learning outdoors in their local greenspace on a fairly regular/very regular basis has risen by 21 percentage points (baseline 28%, post-project 49%)

- The percentage of teachers taking learning outdoors in school grounds on a fairly regular/very regular basis has risen by 31 percentage points (baseline 53%, post-project 84%)

‘All participating teachers acknowledged that they benefited from important informal professional development delivered by staff of their partner organisation during outdoor learning sessions.’ (Source: IDPE, section 4.6)

Benefiting pupils

The project has supported at least 6,000 pupils. The sustained support that has been provided to their schools should mean that many of these pupils will continue to get frequent outdoor learning both in school grounds and their local greenspace. This should nurture a connection to nature which in turn should allow these young people to value nature and in time to make more pro-environmental and pro-conservation behaviours. It should also help engage them with their learning and therefore raise their attainment.

- The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils’ connection to nature is good or excellent has risen by 18 percentage points (baseline 19%, post-project 37%)

- The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils engagement in learning outdoors is good or excellent has risen by 23 percentage points (baseline 56%, post-project 79%)

‘I love these outdoor adventures and learning about all the plants and animals, It’s our job to look after them’ – Primary pupil, Fife

Developing a Legacy

The resources developed through this project have left a legacy of materials to support outdoor learning in a local greenspace for any teacher to use.

- The project internet page

- Beyond Your Boundary: easy steps to learning in local greenspace and its associated supporting documents (greenspace audit, questionnaire to inform action plan and action plan template)

- Beyond Your Boundary: 6 steps to using local greenspace for outdoor learning (professional learning)

- Greenspace Map for Outdoor Learning

- A suite of case studies

- End of project webinar

Data © Crown copyright [and database rights] 2022 OS 100017908, © Maxar, Microsoft; Application © Esri

‘Our project is going to leave an ever-lasting memory with our young people, adults, and us at UTT who have been involved. We have thoroughly enjoyed our last 2 years and will be sad it has come to an end. We are so proud of all our young people, the personal struggles they have overcome, the confidence our teachers have gained. This project will leave an ever-lasting impact. We are incredibly grateful that we got to continue our project on this term, and got to spend time with our schools, especially after everything 2020 has thrown at us so far. We keep up to date with our schools via their online social media and are so happy to see them going outdoors and visiting tier 2 [local greenspace] and tier 3 [nearby countryside] sites and tagging us into their activities.’ – Partner, Falkirk

Key Findings from the evaluation

The key findings from the project evaluation will be presented under the output/outcomes relating to each of the six project objectives as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Project objectives, outputs and outcomes

| Objective | Output/outcome |

|---|---|

|

Objective 1. To identify and remove the specific barriers (perceived or actual) to a school undertaking quality outdoor learning across a range of curricular areas on a regular and frequent basis

|

1a. Greenspaces are more accessible from school grounds 1b. Greenspace quality are improved for outdoor learning, play and use by the community 1c. Teachers of target schools have the confidence to deliver outdoor learning 1d. Teaching resources and equipment have been sourced 1e. Other barriers to outdoor learning have been removed 1f. The schools’ unique set of barriers were identified and removed effectively |

|

Objective 2. To ensure interventions with the schools are self-sustaining into the future

|

2a. Pupils entitlement to regular, frequent outdoor learning experiences at all stages of learning is realised 2b. Teachers feel confident to lead outdoor learning unsupported by partners 2c. The number of teachers taking learning outdoors has increased 2d. Teachers are more likely to take learning outdoors in the future |

|

Objective 3. To improve the health and quality of life for the pupils attending the target schools |

3a. Pupils are more connected to their natural environment 3b. Pupils health and well-being are improved |

|

Objective 4. To raise attainment in target schools |

4.School attainment is raised |

|

Objective 5. To improve local greenspaces for local communities and enhance biodiversity |

5.Local greenspaces are improved for local communities and biodiversity is enhanced |

|

Objective 6. To safeguard the legacy of the project

|

6a. A range of project resources and reports made available on the internet to enable others to use in the future 6b. Local networks of organisations supporting outdoor learning and greenspace improvements work together more effectively as a team |

The findings are presented in a series of tables below by objective. Further detail on the evidence for each outcome/output are presented in Annex 1-6.

Objective 1 findings

Objective 1: To identify and remove the specific barriers (perceived or actual) to a school undertaking quality outdoor learning across a range of curricular areas on a regular and frequent basis. (See Annex 1 for evidence)

| Outcomes/outputs | General summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

1a. Greenspaces are more accessible from school grounds |

Access to greenspace seemed to be a major barrier for some teachers initially, though only in terms of perceived distance from the school rather than other access issues. However, the project evaluation suggests that teachers’ perceptions of access to local greenspace improved over the course of the project. Perhaps their perception at the start of the project was that either the greenspace was too far away to be a viable option, or that they were not aware that there was a suitable greenspace close by. Perceptions were likely to have been changed by the partners taking the teachers and classes to the local greenspace and demonstrating that this was an achievable and beneficial exercise and worked within the confines of the school timetable. |

Partial success |

|

1b. Greenspace quality are improved for outdoor learning, play and use by the community |

Whilst the quality of the local greenspace varied considerably, the perception of poor quality greenspace was seen as being a major initial barrier by the partners and the most intransigent of barriers in their view. In addition to a lack of biodiversity, and signs of drinking dens and drug misuse, the IDPE report also mentioned dog faeces, litter, fly tipping and the use of quad bikes/trail bikes as being issues mentioned by partners. The partners and schools have worked together to overcome this barrier sufficiently to use the sites for outdoor learning and the issue has been used as a learning opportunity. |

Partial success |

|

1c. Teachers of target schools have the confidence to deliver outdoor learning |

Both the teachers and partners agreed that teacher confidence seemed to be a major barrier to outdoor learning at the start of the project. However, the evidence shows this was the barrier that was perhaps most successfully overcome through the project. Both the project evaluation and the IDPE provide compelling evidence to support this. |

Success |

|

1d. Teaching resources and equipment have been sourced |

Both the teachers and partners agreed that appropriate clothing and footwear for pupils seemed to be a major barrier to outdoor learning. This was tackled in a variety of ways, and appears to have been resolved for some schools, but was still an issue for a few schools at the end of the project. Due to Covid-19, this barrier is once again going to be an issue for schools due to the restrictions on sharing equipment. In conclusion, good progress had been made before lockdown but the situation has been exacerbated by Covid-19. The ‘goodies packs’ and seed fund were made good use of by the schools to support outdoor learning. |

Partial success |

|

1e. Other barriers to outdoor learning have been removed

|

In addition to the barriers already discussed above, a number of other barriers were also mentioned:

Two of these issues were identified as significant barriers to outdoor learning – availability of adult helpers/staffing and parental concern. The barrier relating to the availability of adult helper was seen in the comments made by teachers in the project evaluation, whilst the partners also highlighted this as a major issue in the IDPE. This would seem to be an on-going issue at the end of the project and one that has very much been exacerbated by the Covid-19 situation. The issue about parental concern however, which was raised by partners has seemingly been fully resolved. The key learning point with this issue would seem to be to ensure this is factored into future projects through better communication and involvement of parents before the start of a project. The other barriers - Time/effort/timetabling, Bureaucracy and Other priorities/distractions – seemed to be of less concern and certainly seem to have been exacerbated by Covid-19 so have considered these as neutral barriers in the context of this project though it will be important to consider in future projects. |

Partial success |

|

1f. The schools’ unique set of barriers were identified and removed effectively

|

It would seem that whilst the partners thought the NatureScot method of identifying and addressing the schools barriers to outdoor learning was sound, the reality was that it was largely left to the partners to identify the barriers and they largely chose to use their own ways of doing this. The methodology is there for others to use as part of the legacy of this project. In conclusion this can probably be viewed as a partial success. |

Partial success |

|

Objective 1 |

CONCLUSION |

Partial Success |

'The community gardener asked us to come and look at the space one time, so we had a wee wander up, and we were amazed that between the multies there was this fantastic little space, and then when Ross came along, he showed us some opportunities on how we could use it.’ – Primary School Teacher, Dundee

Objective 2 findings

Objective 2: To ensure interventions with the schools are self-sustaining into the future. (See Annex 2 for evidence)

| Outcomes/outputs | General summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

2a. Pupils entitlement to regular, frequent outdoor learning experiences at all stages of learning is realised |

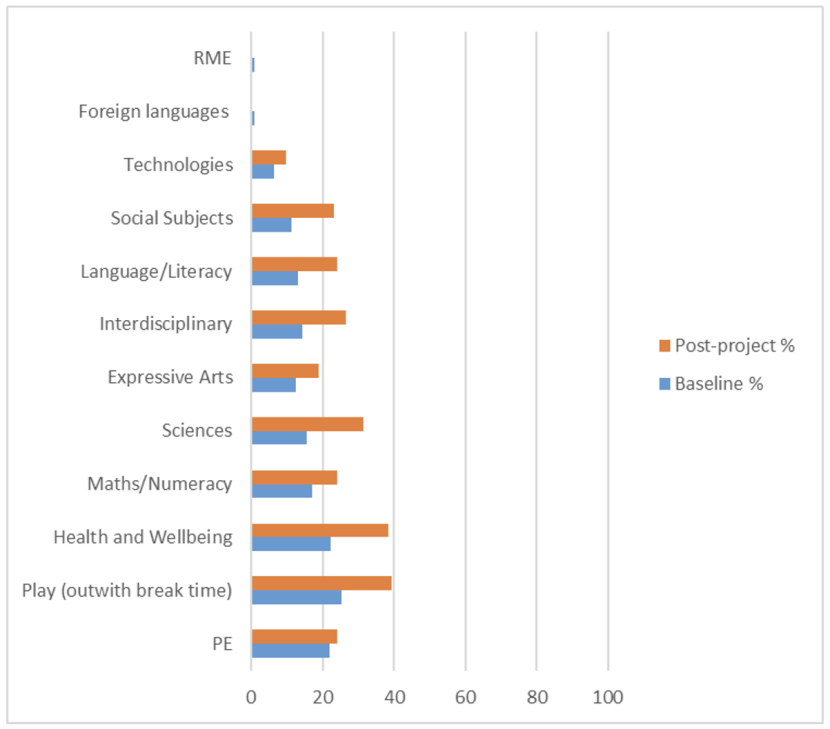

There is a clear increase in the frequency of outdoor learning during the project in both local greenspaces and in the school grounds. You would expect the frequency of use of the school grounds to be higher than the local greenspace due to the distance from the school. The broad pattern of frequency of the curriculum areas that are taught through outdoor learning have stayed much the same during the project, though clearly the frequency has gone up between the baseline and the post project data. Interestingly the pattern between the subjects taught in the school grounds and those in local greenspace is somewhat different. Though RME and foreign languages are rarely taught in either outdoor setting, and technologies is also not so popular, all the other subjects were well represented in outdoor learning in local greenspaces. There is a clear ranking in subjects taken through outdoor learning in school grounds, from PE, play, health and wellbeing, maths/numeracy and interdisciplinary which are the most popular, through to technologies and foreign languages/RME being least popular. However, when it comes to the subjects being taught in local greenspace, there is far less of an obvious hierarchy. The most popular curriculum areas conducted in a local greenspace by the end of the project were play, health and wellbeing, science, interdisciplinary, PE, maths/numeracy and language/literacy. All of the subjects taught in the local greenspace went up in frequency except foreign languages and RME. |

Success |

|

2b. Teachers feel confident to lead outdoor learning unsupported by partners |

The IDPE comments together with the high levels of confidence seen in outcome 1c would suggest that generally teachers did get to a point where they felt confident to lead outdoor learning without support from a partner. |

Success |

|

2c. The number of teachers taking learning outdoors has increased |

The project worked with 500 teachers. The IDPE suggests there have been other teachers across some of the schools that have engaged in outdoor learning that were not directly involved in the support provided by the project. This figure could therefore be an underestimate. |

Success |

|

2d. Teachers are more likely to take learning outdoors in the future

|

There is a clear link with this objective and what we have already seen in outcome 1c. Teacher confidence to take learning outdoors has clearly improved through the course of the project. The IDPE indicates that teachers do intend to take learning outdoors in the future, but clearly shows that Covid-19 has presented an additional barrier. |

Success |

|

Objective 2 |

CONCLUSION |

Success |

‘I’ve become so much more confident working with the children outside. I definitely want to continue doing more of this next year.’ – Primary School Teacher, Fife

Objective 3 findings

Objective 3: To improve the health and quality of life for the pupils attending the target schools. (See Annex 3 for evidence)

| Outcomes/outputs | General summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

3a. Pupils are more connected to their natural environment

|

Both the project evaluation and the IDPE give a strong indication that teachers believe their pupils’ connection to nature and their environment has improved. |

Success |

|

3b. Pupils health and well-being are improved |

Teachers’ perceptions of their pupils’ physical health is that it has declined slightly over the course of the project. It is very likely that this could be due to the impact of the pandemic and lockdown restricting children’s physical activity more generally. Teachers’ perceptions of their pupils’ emotional well-being however is that it has risen very slightly over the course of the project. It is also very possible that this results could too have been skewed by the impact of the pandemic. General comments made by teachers in the post-project evaluation were far more positive on this aspect. By far the most general comments made were relating to the positives of outdoor learning on pupils’ emotional wellbeing. |

Partial success |

|

Objective 3 |

CONCLUSION |

Success |

‘My class goes out at least once a week, but we vary the curriculum area ... It has helped to raise attainment in my class and pupil's health and wellbeing.’ – Primary School Teacher, West Lothian

Objective 4 findings

Objective 4: To raise attainment in target schools. (See Annex 4 for evidence)

| Outcomes/outputs | General summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

4. School attainment is raised |

Teachers’ perceptions of their pupils’ attainment is that it has fallen over the course of the project. However, it is very likely that this is due to the impact of the pandemic and lockdown restricting children’s schooling more generally. We also explored teachers’ perception of their pupils’ engagement in learning in the classroom and in the outdoors. Teachers’ perceptions of their pupils’ engagement in the classroom is that it has fallen over the course of the project. Again, it is likely that this could be due to the impact of the pandemic. However, teachers noted how after an outdoor learning session, pupils were more engaged in the classroom afterwards. In contrast, teachers’ perceptions of their pupils’ engagement in learning in the outdoors is that it has clearly increased over the course of the project and this is one of the key successes of this project. |

Partial success |

|

Objective 4 |

CONCLUSION |

Partial success |

‘As this is now a priority for our school this year I feel that there will be great progress made which will have a positive impact on attainment, wellbeing and overall engagement of the pupils within our school.’ – Primary School Teacher, North Lanarkshire

Objective 5 findings

Objective 5: To improve local greenspaces for local communities and enhance biodiversity. (See Annex 5 for evidence)

| Outcomes/outputs | General summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

5. Local greenspaces are improved for local communities and biodiversity is enhanced |

A range of greenspaces were used by the schools and a variety of approaches to their use were also adopted by the project schools. There was no requirement by the project of the schools to make positive improvements to the greenspace. Some schools adopted the ‘leave no trace’ principle and used the greenspace as they found them. Others felt it was necessary to give the site a ‘tidy up’ before it was safe to use. This might require a litter pick or to arrange to get fly tipping or evidence of anti-social behaviour removed. Other schools actively made improvements to the biodiversity of their site through for example tree planting, the creation of wild flower meadows, or the creation of bug hotels and placing of bird boxes. We did not actively measure or monitor the extent to which this happened, though the partners frequently reported on this activity happening. We would therefore conclude that the project did have a positive impact on many of the local greenspaces used for the benefit of both the school and the local community during this project and we would expect this to continue as the schools continue to use their greenspaces in the future. |

Success |

|

Objective 5 |

CONCLUSION |

Success |

‘Our greenspace learning … has resulted in a bug hotel and the beginning of a bee corridor at the Cathedral. We have lots more ideas, hoping we get to spend next year developing the space further.’ – Primary School Teacher, Highland

Objective 6 findings

Objective 6: To safeguard the legacy of the project. (See Annex 6 for evidence)

| Outcomes/outputs | General summary | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

6a. A range of project resources and reports have been developed and made available on the internet to enable others to use in the future |

NatureScot produced a number of legacy resources as have already been outlined in the section on Developing a Legacy above, and a number of partners also produced a variety of resources. Through the evaluation we know the Beyond Your Boundary resource was well rated by those that used it, but unfortunately amongst the sample of teachers interviewed for the IDPE it was not well known about amongst the project schools despite constant efforts to promote it through a variety of means. |

Success |

|

6b. Local networks of organisations supporting outdoor learning and greenspace improvements work together more effectively as a team |

The IDPE concluded that the majority of partners made some useful collaborations with other organisations in delivering their support for the project schools. These ranged from collaborations with national organisations to local authority departments to small local groups This project has changed the way that partner organisations support outdoor learning and changed their view of the value of using local greenspaces for outdoor learning rather than simply resorting to using school grounds. It would also seem that the project has provoked more thought into what is necessary to make real lasting change and embed outdoor learning at schools. |

Success |

|

Objective 6 |

CONCLUSION |

Success |

‘The project is and was worthwhile, and if funding could be found, we suggest revisiting the aim of Learning in Local Greenspace by supporting schools to find and use their local spaces for quality outdoor learning.’ - Partner

The overall rating for the project is therefore a success (especially given the impact of Covid-19).

Lessons learned and next steps

Despite the significant impact of the Covid pandemic the project has been largely successful and provides a firm foundation for increasing our work with schools in future. This concluding section of the report outlines what we learned from the project and identifies some potential next steps.

Lessons Learned

The key lessons learned are as follows:

Working with Schools

- Having someone from the local authority education department on board helps to open doors to schools.

- Communication with head teachers on the role and importance of outdoor learning is vital.

- Keep paperwork and processes for schools as simple as possible and ensure those directly supporting the schools e.g. the partner organisations, are responsible for managing contacts and acting as a go between where possible.

- The turnover of staff in schools is significant and this needs to be built into the project design, implementation and evaluation. The situation in schools can literally change overnight so nothing is guaranteed and you need to be prepared for this and adapt accordingly in case a school pulls out of a project with little or no warning. Over reliance on one, or a small number of schools for an evaluation for example should therefore be avoided.

Project development

- Stakeholder engagement and co-production was vital to the success of the project.

- Establishing robust, discrete aims, objectives, outputs and outcomes from the project and mapping these to each other and the evaluation as early as possible is really important. This can take time in a co-design project and should be checked periodically to ensure the objectives and outputs/outcomes are still fit for purpose.

- It was a useful to do the initial GIS analysis to look into the feasibility of the project, the target and to determine definitions.

- Testing thinking through an early pilot was a worthwhile exercise.

- Being aware of potential synergy between this project and other initiatives on the ground (opportunity mapping) through the development of the project was useful.

- Ensure adequate staff resource for projects of this scale and complexity

- Projects of this scale should have a dedicated funding mechanism which should be designed in tandem with the project from the outset.

Project monitoring and evaluation

- The data we collect in large school projects will never be perfect because there are so many variables involved and different people interpret and record this in different ways. However, to help make the data better it would have been useful to have a standard mechanism for reporting built into the funding rather than relying on each project to report in their own way.

- Further discussion with Education Scotland would be useful to explore the role and focus of future quantitative and qualitative research in a small number of schools for future projects.

- There is scope to use emerging methodologies to assess changes in connectedness to nature among both pupils and staff

Recommendations and Next Steps

As part of the IDPE the partners were asked what they thought NatureScot could do to help embed outdoor learning. A variety of ideas were forthcoming. These included:

- The Beyond Your Boundary resource should be complemented by a series of short printable guides that address specific situations and make the guidance more accessible to busy teachers.

- Make some video case studies

- Develop a flyer for parents that explained what outdoor learning is and its value to their child’s education and school experiences.

- Support the provision of experienced outdoor learning leaders to stimulate greater engagement on the part of schools.

- Provide funding explicitly for CLPL for teachers.

- ‘Front-load’ teacher training in NatureScot projects. Training might also be extended to include adult helpers and classroom assistants.

- A future NatureScot project might focus on the connections between issues in local greenspaces and more global concerns about sustainability.

- Future projects in schools could consider engaging fewer schools but for a more sustained period to ensure that outdoor learning became embedded in the learning practices of the school.

It will be important that the legacy of this project is maintained and promoted and that future work with schools takes into account the learning and partners’ suggestions made.

In considering its plans to build on this work as part of the next biodiversity strategy, NatureScot should continue to take a collaborative and long-term approach to the embedding of outdoor learning across all Scottish schools. Direct support of the kind offered via this project will also be important, especially if outdoor learning is to be better embedded in secondary schools. A step change in investment in this work would be required to reach all schools, e.g. at a similar level to the Active Schools programme.

In addition, it will be important to work strategically with key partners as follows:

- Education Scotland on links to outdoor learning in the curriculum and inspection process.

- General Teaching Council for Scotland and others on initial teacher training and CLPL.

- Universities on research to better understand the mechanics at play that allows some schools to embed outdoor learning so effectively whilst others seem so resistant.

- Working with environment sector partners in a strategic way that maximises the impact of our individual skills and resources

References

Dasgupta, P. 2021. The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. (London: HM Treasury).

Learning and Teaching Scotland, 2010. Curriculum for Excellence through Outdoor Learning

The General Teaching Council for Scotland, 2012. Archive: 2012 Professional Standards.

The Scottish Government, 2015. Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 2020.

Walter Patterson Consultancy, 2021. Learning in Local Greenspace: An Evaluation on behalf of NatureScot, unpublished.

Annexes

Annex 1 - Evidence to support key findings for objective 1

Objective 1: To identify and remove the specific barriers (perceived or actual) to a school undertaking quality outdoor learning across a range of curricular areas on a regular and frequent basis

Output/outcome 1a

Greenspaces are more accessible from school grounds: partial success

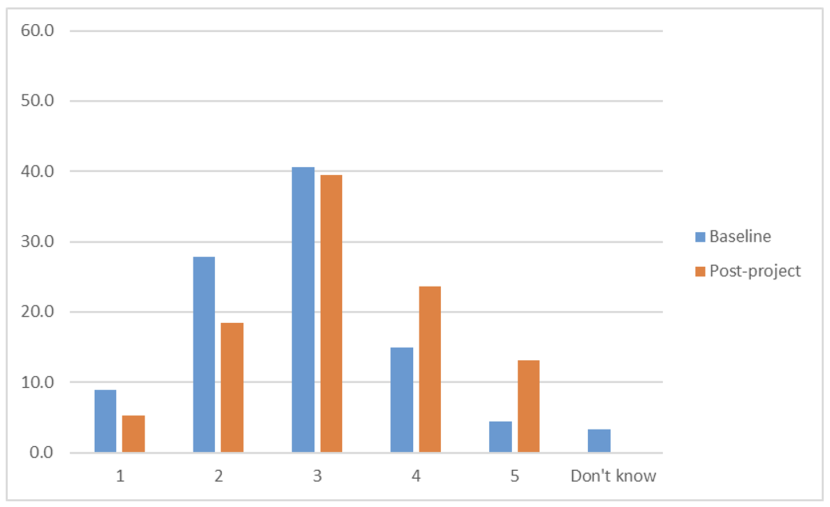

Project evaluation evidence

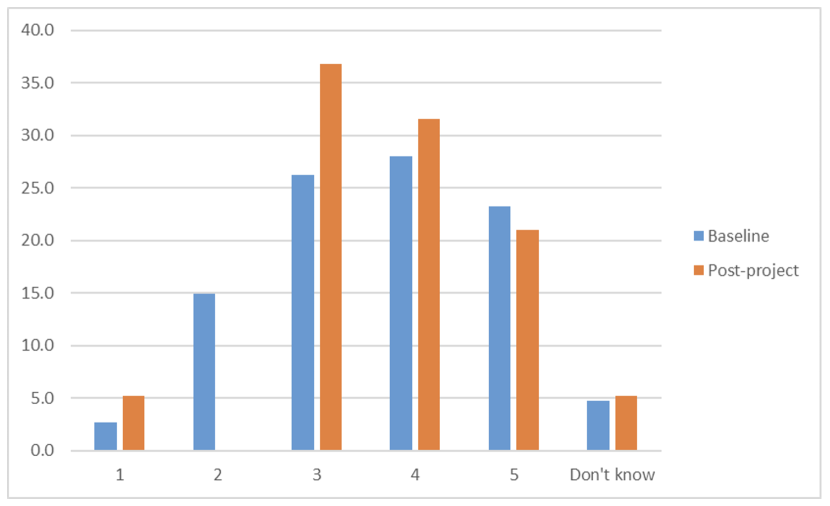

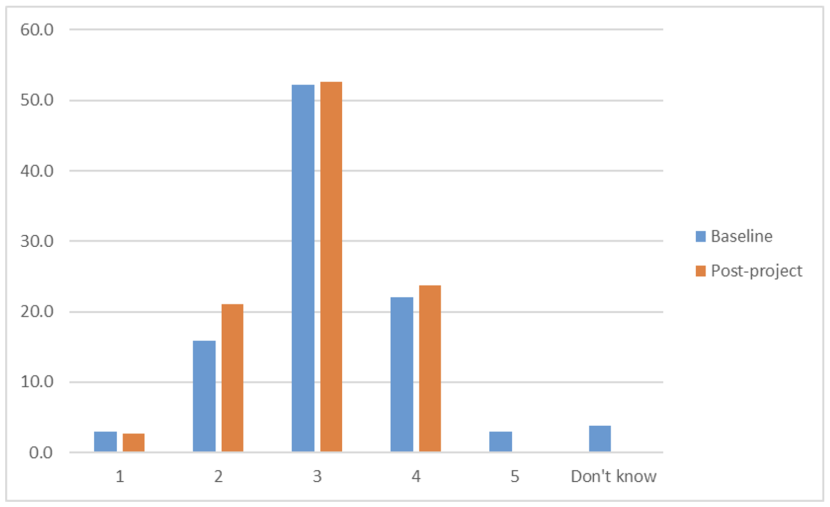

Teachers were asked, ‘On a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 is very poor and 5 is excellent) how would you rate the accessibility of your local greenspace for outdoor learning?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing categories 1-5 and an option for ‘don’t know’. The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that there is a higher proportion of teachers at the end of the project that think the accessibility of their local greenspace is average to good than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe the accessibility of their local greenspace is average to excellent (scores 3-5) has risen by 11.8 percentage points (baseline = 77.7% and post-project = 89.5%).

IDPE evidence

‘While around half of the participating schools had identified local greenspace suitable for use prior to this project, the remainder relied on the partner organisation to identify and audit greenspaces that could be safely used by the school. However, in a few cases, the distance between the school and the greenspace limited the amount of time spent in outdoor learning.’ (Source: IDPE, Appendix 1)

Quote

‘The community gardener asked us to come and look at the space one time, so we had a wee wander up, and we were amazed that between the multies there was this fantastic little space, and then when Ross came along, he showed us some opportunities on how we could use it.’ – Primary School Teacher, Dundee

Output/outcome 1b

Greenspace quality are improved for outdoor learning, play and use by the community: partial success

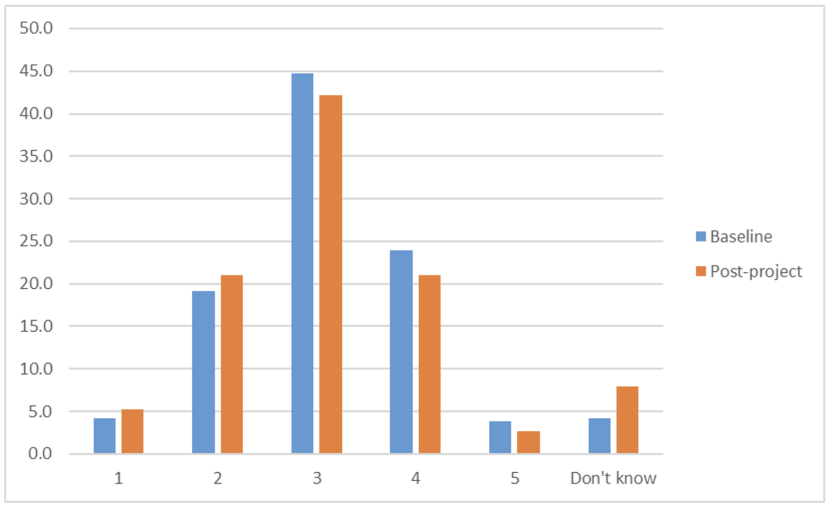

Project evaluation evidence

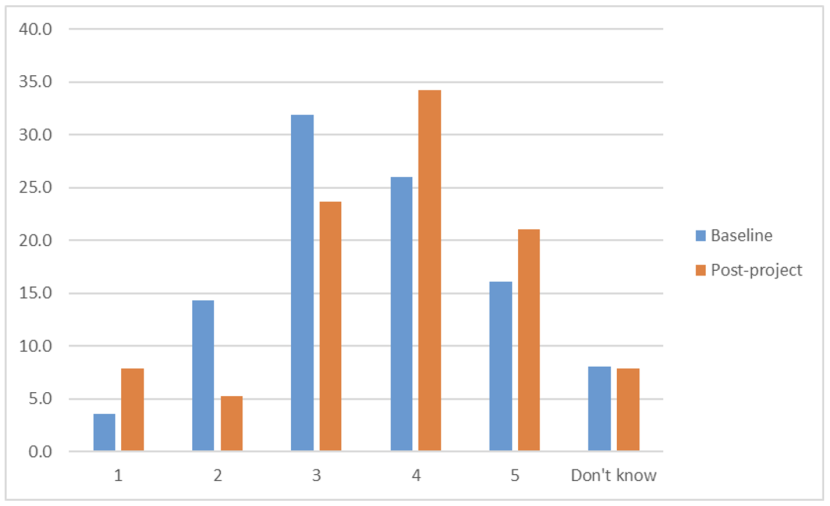

Teachers were asked, ‘On a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 is very poor and 5 is excellent) how would you rate the quality of your local greenspace for outdoor learning?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing categories 1-5 and an option for ‘don’t know’. The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that there is a higher proportion of teachers at the end of the project that think the quality of their local greenspace is good to excellent than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe the quality of their local greenspace is good to excellent (scores 4-5) has risen by 13.2 percentage points (baseline = 42.1% and post-project = 55.3%)

IDPE evidence

‘In general, the local environments accessed by pupils were safe although one school reported finding evidence of drug misuse. (Source: IDPE, section 4.3)

‘A range of approaches was adopted by partners to address issues with local greenspace. In some cases the removal of litter from sites was taken on by pupils and teachers as an element of caring for the environment, while in others help was sought from community groups (e.g. Community Payback) to help clean sites of illegal tipping and broken glass.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.4.3)

Quote

‘Outdoor learning is essential for learning and raising the attainment in our area. The children love investigating and exploring outdoors though we could do with a more inviting area for outdoor learning to enhance their experience.’ Primary Teacher, South Ayrshire

Output/outcome 1c

Teachers of target schools have the confidence to deliver outdoor learning: success

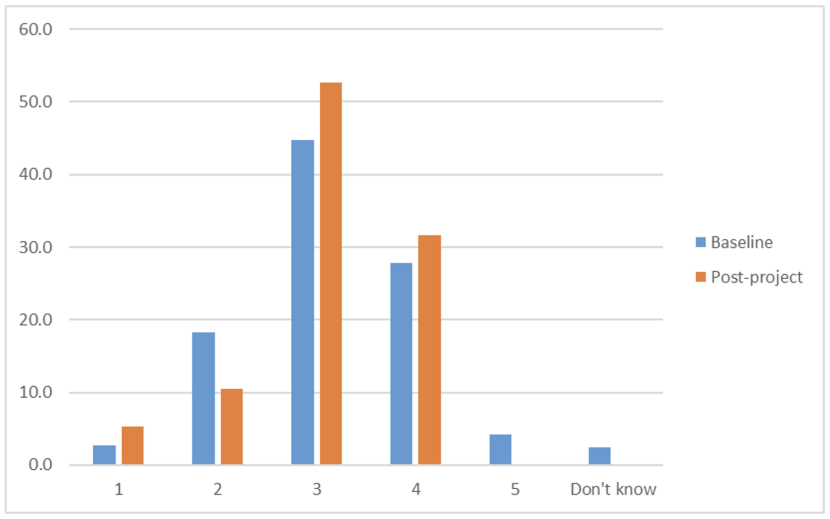

Project evaluation evidence

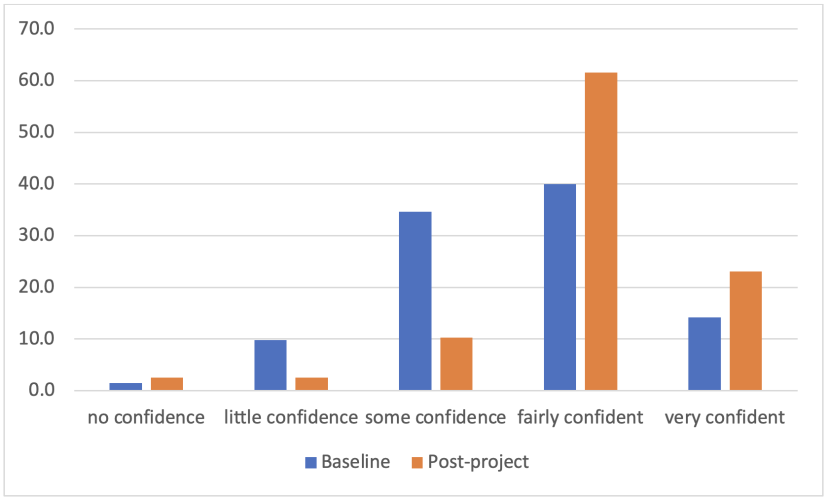

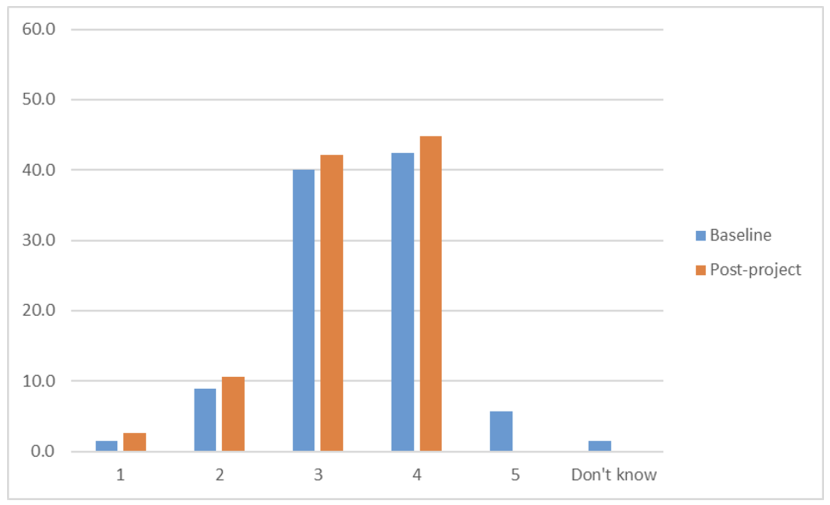

Teachers were asked, ‘How confident do you feel to take learning outdoors?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing five categories from no confidence to very confident. The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that that there is a higher proportion of teachers at the end of the project that rate their confidence to take learning outdoors as fairly confident to very confident than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe they are fairly or very confident to take learning outdoors has risen by 30.5 percentage points (baseline = 54.1% and post-project = 84.6%)

IDPE evidence

‘Staff in a majority of schools stated that they had been hesitant about engaging their pupils in outdoor learning due to their own lack of experience of outdoor learning or their unfamiliarity with aspects of the natural world. However, the support of their partner organisations contributed very effectively to overcoming this barrier. (Source: IDPE, section 4.2)

‘…there were different approaches taken to improving teacher confidence and allaying their doubts about the value and usefulness of taking learning outdoors. One approach was to ‘front load’ the project by providing teachers with some training and familiarisation with the purpose and implementation of outdoor learning. Another was to immerse the teachers in the outdoor space in sessions with their pupils that were devised and led by the partner organisation.

Whichever approach (or combinations of these) was used the universal report from the partners was of transformation in teacher attitudes. A few partners mentioned doubting teachers changing to become passionate advocates of outdoor learning in their school.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.4.1)

Quote

‘I’ve loved learning all of the little games to play in the woods that help focus the children for the day’s tasks or consolidate learning – great fun!’ – Primary School Teacher, Fife

‘They enjoy outdoor learning and as the term has progressed their listening skills have improved and I feel more confident taking them outside.’ Primary School Teacher, West Dunbartonshire

Output/outcome 1d

Teaching resources and equipment have been sourced: partial success

Project evaluation evidence

N/A

IDPE evidence

‘For a few schools… [clothing and footwear] still remained a barrier at the end of the project. Almost all partners had worked with their schools to find a way of providing pupils with access to appropriate clothing and footwear. Some partners had accessed additional funding for themselves that enabled them to equip their schools with the necessary clothing and footwear or create a loan bank for that purpose. Others had helped the schools identify pockets of funding to purchase equipment for themselves, including the £250 provided by NatureScot and Pupil Equity Funding (PEF) where it was available.

However, where clothing/footwear was made available on a loan basis, this had to cease when the pandemic arrived in the spring of 2020. It was also noted by more than a few partners that some pupils chose fashion over comfort, even when suitable outdoor clothing was available to them.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.4.2)

‘Most teachers appreciated and made good use of the class sets of magnifiers made available to them. They also stressed the importance of appropriate clothing and footwear. Schools also benefited from loan of equipment such as binoculars from their partner organisation.’ (Source: IDPE, section 4.7)

‘A range of project resources and reports were made available on the internet to enable others to use in future. Most partner organisations mentioned preparing ‘legacy packs’ of resources for schools to use to continue taking young people outwith the school grounds for learning purposes. The curtailment of planned outdoor activity due to Covid-19 had provided scope for partner organisations to fulfil their obligations to NatureScot by adapting their resources for online use.’ (Source: IDPE, Appendix 1)

Quote

‘It was great to see the resources that could be used for a bug hunt. It gives me more confidence to take the children out and make sure the lesson is purposeful’ – Primary School Teacher, Glasgow

‘Resources supplied by LILG have also facilitated further outdoor learning.’ Principle Primary School Teacher, South Lanarkshire

Output/outcome 1e

Other barriers to outdoor learning have been removed: partial success

Project evaluation evidence

‘Our main barrier is staffing; we struggle to have sufficient staff to take kids off site or support individuals who require it.’ Primary School Teacher, Glasgow

‘A continuing demand to raise attainment means that often there is less time for outdoor learning.’ Primary School Principle Teacher, South Lanarkshire

‘The current barriers are actually the same as before, time in the day and parent helpers. Lunch now starts at 11.45, so spending a morning out of school is difficult as by the time we walk to our nearest safe local greenspace it can take between 10 and 30 minutes, depending on the primary class going. So just as we get there and start to get excited about the area, we need to leave.’ Primary School Teacher, Glasgow

‘Process to get pupils out of school even across the road is tedious and long which is a barrier to accessing outdoor learning.’ Secondary Teacher, Fife

‘New school being built on our playground at present plus lockdown has impacted on amount of outdoor learning this year.’ Primary School Teacher, West Dunbartonshire

IDPE evidence

‘The arrival of the pandemic worsened the position of adult helpers, as Covid-19 protection did not allow adults other than teachers to have contact with pupil groups.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.4.5)

‘Almost all partner organisations recognised the concerns of parents and provided the school with detailed information to pass to concerned parents. Most partners acknowledged that it would have been helpful to the project to have planned that parents should be invited to be present to see first-hand the activities of the children. By the end of the project this anxiety on the part of parents was no longer a barrier, although for a few there remained issues where parents did not return signed permission forms in a timely manner.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.4.4)

Quote

‘We want to make going outdoors easier for staff. This year the management team created a policy of being able to just go to [Park H] and [Park C] without prior written notice to parents/carers. The hope would be that this would allow for classes to go on the spur of the moment when the weather broke or to address subjects that come up during the school day. This hadn’t really happened in most classes, but each class had also signed up to the RSPB Wild Challenge and I’m sure had we remained open, more classes would have been using our green spaces to deliver learning’ – Primary School Teacher, Glasgow

Output/outcome 1f

The schools’ unique set of barriers were identified and removed effectively: partial success

Project evaluation evidence

N/A

IDPE evidence

‘There was general agreement among the partner organisations that the NatureScot questionnaire and the Action Plan template provided a helpful resource that schools ought to be using in their planning for outdoor learning. However, partners were also confident enough in their own processes and experience of planning to opt to favour using this over the provided NatureScot resource.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.5)

Annex 2 - Evidence to support key findings for objective 2

Objective 2: To ensure interventions with the schools are self-sustaining into the future

Output/outcome 2a

Pupils entitlement to regular, frequent outdoor learning experiences at all stages of learning is realised: success

Project evaluation evidence

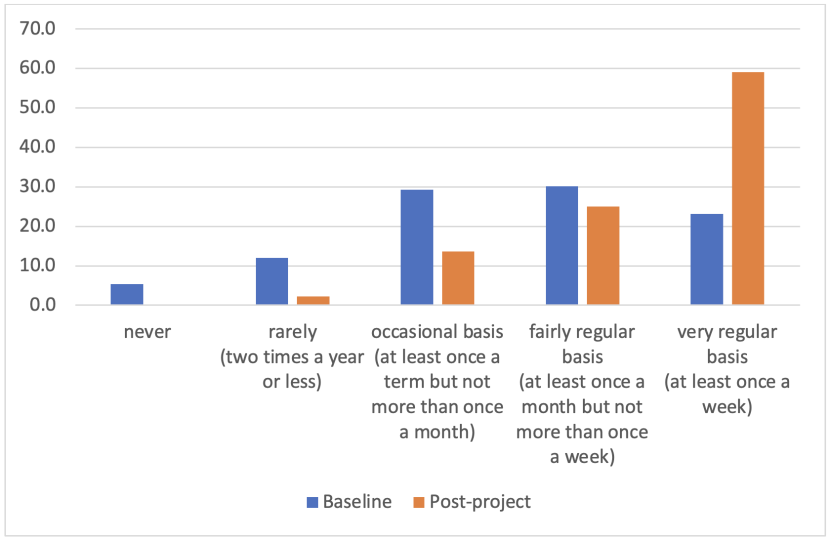

Teachers were asked, ‘How often do you use your establishment grounds for learning?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing five categories from never to very regular basis (at least once a week). The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that that there is a substantially higher proportion of teachers at the end of the project that use their establishment grounds for outdoor learning on a very regular basis than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe they take learning out into their establishment grounds on a very regular basis has risen by 35.9 percentage points (baseline = 23.2% and post-project = 59.1%)

Teachers were asked, ‘How often do you use your local greenspace for learning?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing five categories from never to very regular basis (at least once a week). The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that that there is a higher proportion of teachers at the end of the project that use their local greenspace for outdoor learning on an occasional basis to very regular basis than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe they take learning out into their local greenspace on a very regular basis has risen by 19.2 percentage points (baseline = 9% and post-project = 28.2%)

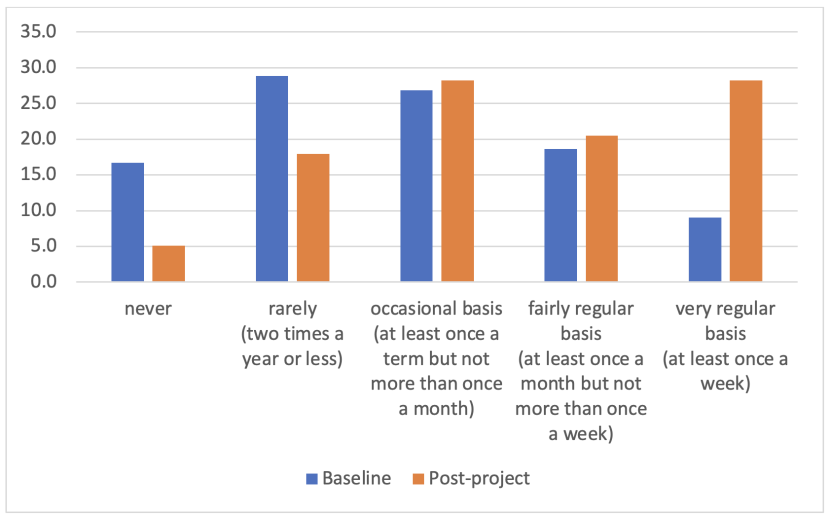

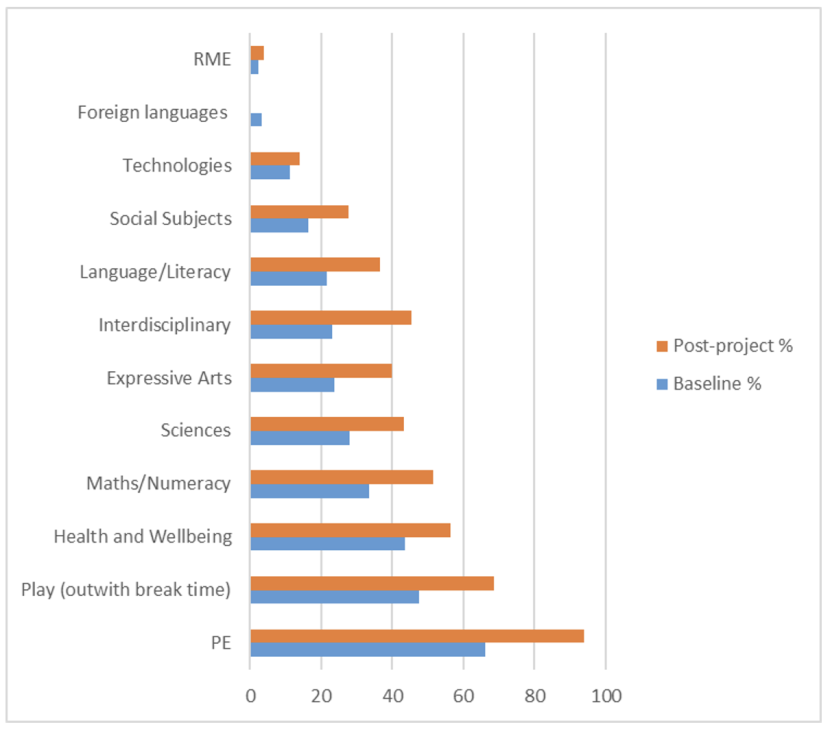

Teachers were asked, ‘Considering all the outdoor learning sessions you conducted in your establishment grounds over the course of last year, note which curriculum areas were covered on a regular basis (i.e. once a month or more), occasional basis (less than once a month), never or I don’t teach this’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph where the x axis is a percentage scale. The y axis shows 12 curriculum areas (RME, foreign languages, technologies, social subjects, language/literacy, interdisciplinary, expressive arts, sciences, maths/numeracy, health and wellbeing, play outwith break time and PE). The graph shows that that there is a higher proportion of teachers teaching each of the subjects in their school grounds at the end of the project than at the baseline, except for one subject (foreign languages). There is also a clear increase in popularity of the subjects for teaching out in the school grounds as you descend through the list of curriculum areas (i.e. RME and foreign languages being the least popular subjects to be taught outside, through to Play and PE being the most popular).

Teachers were asked, ‘Considering all the outdoor learning sessions you conducted in your local greenspace over the course of last year, note which curriculum areas were covered on a regular basis (i.e. once a month or more), occasional basis (less than once a month), never or I don’t teach this’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph where the x axis is a percentage scale. The y axis shows 12 curriculum areas (RME, foreign languages, technologies, social subjects, language/literacy, interdisciplinary, expressive arts, sciences, maths/numeracy, health and wellbeing, play outwith break time and PE). The graph shows that that there is a higher proportion of teachers teaching each of the subjects in their local greenspace at the end of the project than at the baseline, except for two subjects (RME and foreign languages). There is also a more even spread in popularity of the subjects for teaching out in the local greenspace. The least popular subjects to teach in a local greenspace are RME and foreign languages, whilst the most popular subjects are Play and health and wellbeing.

IDPE evidence

‘For those pupil groups participating in the project there was regular and frequent outdoor learning experiences. However, in all but two schools the engagement was not across all stages – either restricted to one- or two-year groups, or to pupils selected by the school as requiring an alternative curriculum, or pupils with additional support needs.’ (Source: IDPE, Appendix 1)

Quote

‘I can’t believe how many maths activities we did with so few resources. The children were all on task.’ – Primary School Teacher, Fife

‘We get to do a bunch of different things and we are outside a lot more so it’s better.’ Primary Pupil, Glasgow

Output/outcome 2b

Teachers feel confident to lead outdoor learning unsupported by partners

Project evaluation evidence

See evidence under outcome/output 1c.

IDPE evidence

‘…the support of their partner organisations contributed very effectively to overcoming this [teacher confidence] barrier. One teacher expressed the view that newly qualified teachers whom she had met did not appear to have received effective teacher training in outdoor education.’ (Source: IDPE, section 4.2)

‘Teacher experiences of outdoor sessions planned and managed by a partner led to their improved confidence and to the acceptance of responsibility for planning and leading on their own.’ (Source: IDPE, section 3.4.1)

Quote

‘I felt that being able to observe and then team-teach alongside yourself was beneficial in ensuring I felt confident in taking the children out with the school grounds and delivering teaching and learning. Through team teaching I was able to understand the planning more in-depth and use this more effectively. This was also helpful in terms of safety for children with complex additional support needs and ensured I felt confident supporting those children out-with the school grounds.

The routines and expectations you started with the class have been helpful in the continuation of Outdoor Learning sessions. I now take the children out at least once a week and have a dedicated 'Forest Friday' morning in my planning. The resources and Outdoor learning map Kirsten shared have aided with future lesson planning.

The sessions inspired me to read and research further within the field of Outdoor Learning and build upon my knowledge and understanding. I really loved our Outdoor learning Sessions. Not sure I would have the confidence I have now without them!’

– Primary School Teacher, Edinburgh

Output/outcome 2c

The number of teachers taking learning outdoors has increased: success

Project evaluation evidence

‘More children and classes are spending an increasing time in our school grounds. Our planning now incorporates some OL. Our main barrier is staffing; we struggle to have sufficient staff to take kids off site or support individuals who require it.’ Primary School Teacher, Glasgow (source: post-project evaluation)

IDPE evidence

‘There is evidence from staff in all schools that their engagement in Learning in Local Greenspace has generated interest in outdoor learning by other members of the teaching staff, particularly younger teachers. In one school, learning outcomes devised for this project were passed to the other P1/2 teachers who then took their own classes out informally to implement some of the learning experiences of the original group. However, it is not clear how all schools will capitalise on this enhanced interest to embed outdoor learning more fully in the school curriculum. As stated above, in one school outdoor learning without the participation of a partner organisation has increased, taking place in the school grounds. All teachers with an interest in increasing the role of outdoor learning in the curriculum stressed the need for appropriate CLPL for a wide range and large number of school staff.’ (Source: IDPE, section 4.8)

‘In Rxxx PS, which had run the project with a selected group of pupils in P1-P4 who had additional needs, outdoor learning has been extended to pupils in P5-P7 who have similar needs.’ (Source: IDPE, section 4.5)

Quote

‘Commencing at start of February 2021, as part of our agreed temporary lockdown actions; ‘Outside-Inside Coffee Catch-up’ sessions. These informal sessions occur weekly on Friday afternoons, and each presents a different theme/aspect of Outdoor Learning. We have encouraged a range of practitioners to share their practice and the sessions remain a positive and dynamic close to the week with around 15 – 25 teachers in attendance most weeks. We now have 75 members of our TEAMS group, and it is hoped that this collective will continue to use to group to share and inspire each other to get outdoors as a professional network.’ Partner, Edinburgh

Output/outcome 2d

Teachers are more likely to take learning outdoors in the future: success

Project evaluation evidence

‘There is continuous development of outdoor learning throughout our school and we hope to continue this. We have created a support document for staff with practical advice and support to help implementation further.’ Primary School Teacher, Fife (source: post-project evaluation)

IDPE evidence

‘Most teachers were keen to continue some form of learning in the outdoor environment but recognised that recent disruption to education brought about by the COVID-19 situation had pushed such plans further into the future. They identified support from their headteacher as crucial to the continuation of outdoor learning as well as support from sufficient numbers of their colleagues. ...’

‘…Teachers who participated now value the additional dimension which outdoor learning brings to pupil experiences. They understand that for many pupils, development of their literacy and numeracy skills, along with an enhanced appreciation of soft skills such as teamwork, self-reliance, self-confidence, tackling the new, and other aspects of the affective domain, are important outcomes of learning outdoors. Schools which noted the value of this additional dimension to learning are keen to continue, expand where possible, and enhance the pupil experience.

However, since March 2020, there has been very little opportunity for schools to plan and implement more widely the outdoor learning experience for pupils. With the absence of pupils from schools for very long periods of time since March 2020 teaching staff have had to concentrate on supporting pupils at a distance, an approach which does not lend itself readily to learning in the outdoors.’ (Source: IDPE, section 4.5)

Quote

‘I’ve become so much more confident working with the children outside. I definitely want to continue doing more of this next year.’ – Primary School Teacher, Fife

Annex 3 - Evidence to support key findings for objective 3

Objective 3: To improve the health and quality of life for the pupils attending the target schools

Output/outcome 3a

Pupils are more connected to their natural environment: success

Project evaluation evidence

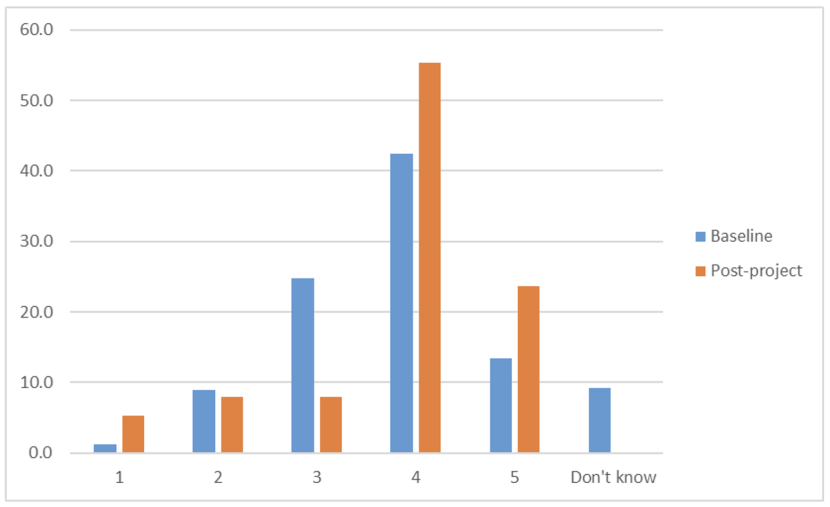

Teachers were asked, ‘On a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 is very poor and 5 is excellent) how would you rate your pupils' connection to nature and their environment?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing categories 1-5 and an option for ‘don’t know’. The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that that there is a higher proportion of teachers at the end of the project that think that their pupils’ connection to nature and the environment is good to excellent than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils’ connection to nature and their environment is good to excellent (scores 4-5) has risen by 17.5 percentage points (baseline = 19.4% and post-project = 36.9%)

IDPE evidence

‘Respondents reported very positively on the reactions of pupils to their exposure to aspects of their local natural environment, including a sense of ‘ownership’ of the spaces in which they had improved its quality and contributed to its biodiversity. Pupils enhanced their knowledge of the natural world, often from a very low base.’ (Source: IDPE, Appendix 1)

Quote

‘The children all (at one time or another) began to ask more questions – they had a heightened sense of wonder, asking and wanting to know more about the names of flowers, bugs, trees etc. They tried to match leaves to trees, and considered shapes, colour and so on. They were all fascinated when they saw thousands of fern spores floating through the air, wondering what kind of magic it could be.’ – Primary School Teacher, South Lanarkshire

‘I used to be scared of everything in nature but now I’ve been out more I like it.’

- Primary pupil, Glasgow

Output/outcome 3b

Pupils health and well-being are improved: partial success

Project evaluation evidence

Teachers were asked, ‘On a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 is very poor and 5 is excellent) how would you rate your pupils' physical health (e.g. days off sick)?’ The baseline data (blue) and post-project evaluation data (orange) are presented on a bar graph with the x axis showing categories 1-5 and an option for ‘don’t know’. The y axis is a percentage scale. The graph shows that that there is a lower proportion of teachers at the end of the project that think that their pupils’ physical health is average to excellent than at the baseline.

The percentage of teachers that believe their pupils’ physical health is average to excellent (scores 3-5) has fallen by 6.8 percentage points (baseline = 72.6% and post-project = 65.8%).