Guidance - Guide to Hydro Construction Good Practice

This guidance is for everyone involved in the development and construction of a hydro scheme. It directs to the appropriate sections of existing guidance, provides advice to help minimise construction impacts and highlights legislative compliance requirements. It is a joint publication between NatureScot, SEPA, Scottish Renewables and the Association of Environmental Clerk of Works.

Published: 2020 (Refresh of Version 3)

1. Introduction

The Scottish Government, NatureScot (rebranded from SNH) and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) support hydro development as a key means of tackling climate change. However, protecting out natural heritage should be a key priority during any development. Development must not come at the cost of damage to and loss of Scotland’s valued habitats and wild landscapes. In the long term, the impact of some of these schemes could also damage rural economies where these are dependent on the quality of the landscape and natural heritage as visitor attractions.

1.1 Using this guide

This guidance has been developed to direct all stakeholders involved in development and construction of a hydro scheme to the appropriate sections of existing guidance, as well as provide a level of standing advice to help minimise construction impacts and highlight legislative compliance requirements.

We recommend this guide is presented to anyone working on a hydro construction site, and that owners of the scheme, or those responsible for carrying out construction work, ensure all parties understand and agree to adhere to these standards before construction commences.

SEPA and NatureScot should be contacted if anyone developing or constructing a hydro scheme has any questions about pollution prevention or natural heritage aspects (as per our NatureScot and SEPA Service Statements), or if you intend to make changes to pre-agreed plans.

A list of the existing guidance documents to which this document refers can be found in Section 9.

2. General pre-construction considerations

Serious environmental harm can come from construction sites. For example, excavations can damage habitats and construction works can disturb and displace species. Without adequate mitigation measures, the water environment and surrounding habitats can become polluted as falling rain picks up and deposits silt. This silt can clog fish gills and it can prevent sunlight reaching aquatic plants and smother riverbed organisms. Should such incidents occur, site operators must take all measures to control and prevent further runoff. They must also contact SEPA and affected water users.

A construction strategy should be informed by the application stage survey and assessment work undertaken. Mitigation schedules and implementation plans, in the form of Construction / Environment Management Plans (CEMP) and Construction Method Statements (CMS), should guide work on site and be available for all contractors (further information in Section 5 below).

Getting pre-construction right will minimise pollution of the environment, harm to human health and unnecessary damage to nature conservation interests. It will also reduce risk, cost and delay, and increase stakeholder confidence in the project.

There may also be implications through the Waste Management Licensing (Scotland) Regulations 2011, not least through the movement and disposal of peat or forestry waste, depending upon the nature of the site. In these cases operators must produce and comply with a peat management plan or waste management plan, and all appropriate waste licences or exemptions must be in place before operations begin. The approach should be to minimise excavation of peat during construction.

Water related regulations

All hydropower schemes require a water use licence under the provisions of Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (as amended) (CAR), which authorises all abstractions and the construction and operation of all impoundments, intakes and abstraction return structures related to the scheme. The CAR water use licence and the planning permission together will control the construction requirements and risks.

In terms of construction phase surface water run-off you do not need to apply to SEPA for a construction site licence provided that you operate the site in accordance with the general binding rules (GBRs) specified in CAR, and the construction site does not:

- exceed 4 hectares in area;

- contain a road or track length in excess of 5km; or

- include any area of more than 1 hectares or any length of more than 500 metres on ground with a slope in excess of 25 degrees.

Details of these rules can also be found in the CAR practical guide. SEPA would still expect that a comprehensive CEMP is produced detailing how compliance with the General Binding Rules will be achieved, and the water environment protected.

If your construction site exceeds any of the above thresholds, you must apply to SEPA for an authorisation to discharge surface water run-off from the site.

Further details of the issues to consider at this stage can be found on pages 9-11 of SEPA’s Good Practice Guide: Temporary Construction Methods. It is essential that all relevant staff are aware of the requirements of the relevant CAR water use licence, and that a copy of the licence is readily available on site for consultation.

Species related regulations

NatureScot can licence, for certain specific purposes, actions that would otherwise constitute an offence against a protected species.

Hen harrier (Circus cyaneus) Of the UK's birds of prey, this is the most intensively persecuted. Please report any sightings to NatureScot.

Explore the A–Z guide to find out about licensing for a specific protected species, including how to apply for each type of license.

Any advice on natural heritage needs to be balanced with the technical design and other considerations involved in the project. The planning authority, regulatory authorities and their advisers cannot take any liability for the final design of the project, or any changes made as a result of our advice. It is the applicant's responsibility to design the project taking into account environmental, health and safety, technical and engineering considerations.

2.1 Understanding topography

You should consider topography early in the process, from reviewing current maps and detailed ground surveys. This information is important to assess the potential catchment area for expected surface water run-off, as this will be required when sizing culverts, spacing off-lets, settlement lagoons, and drainage system treatment trains. It also gives an indication of habitat types, underlying soils, geology and contours.

Access tracks and associated infrastructure - including pipeline routes - should avoid water bodies, including Ground Water Dependant Terrestrial Ecosystems (GWDTEs, e.g. groundwater fed wetlands, such as flushes etc.) wherever possible. It is important that you consider access to and from borrow pits in terms of forming routes over sensitive habitats and impact on soils.

You should identify routes that avoid, do not fragment, and will not damage areas of high Earth Heritage value (e.g. Geological Conservation Review sites). Where avoidance is not possible, understand the qualifying features to ensure construction practices reduce impacts. Compensate where required.

2.1.1 Working on steep ground

Without due consideration and professional management the construction of infrastructure on or across steep ground could lead to catastrophic failures with potentially serious physical, costly and environmental results.

You should carry out a comprehensive ground investigation to characterise the ground conditions. Important information for track construction comes from peat/topsoil probing, trial pitting, in-situ shear vane tests, and particle size distributions. This information provides key details to allow a full understanding of the ground make-up.

Where it is necessary to drill through, or excavate a cutting through the bedrock or unconsolidated overburden (sediment or peat and soil), a geotechnical survey should consider:

- the geometry and form of the slope;

- the condition and properties of the constituent materials; and

- an assessment of the risk of slope failure.

It is critical that the conclusions and / or recommendation from a geotechnical assessment are referred to in the CEMP and that all contractors on site are made aware of potential risks.

2.1.2 Working on peat

Avoiding areas of peatland in the design and construction of a hydro-electric scheme and its associated infrastructure will reduce disturbance to this sensitive habitat, lower carbon losses, and minimise soil and drainage management issues that could have an impact on development costs and timings.

Peat landslides are a characteristic landscape response of peat uplands to intense rainfall events, but can also arise from inappropriate construction practices. Terrestrial habitats in the path of a peat landslide may be damaged by ground displacement and by burial, and aquatic habitats damaged by debris in watercourses. In addition, the displacement and break-up of peaty debris after a landslide event will result in depletion of the stored carbon.

The Planning Authority should expect developers to demonstrate that site specific peat stability information has been properly recorded, analysed and presented. For example if a developer's site investigation/survey identifies any area of high or medium risk in relation to a potential peat landslide incident, then it is expected that the submitted information will include detailed proposals of mitigation measures that reduce those risk levels to an acceptable or manageable level.

Specific site management plans should also address the risks associated with peat landslides following construction and after restoration works are complete.

Further information can be sourced in the Scottish Government’s ‘Peat Landslide Hazard and Risk Assessments: Best Practice Guide for Proposed Electricity Generation Developments (Second Edition)’.

2.2 Landscape and visual impacts

Impacts arising from the construction phase of a hydro scheme can range from infrastructure development to modified habitats; including excavations; draw-down scars; railings and (coloured) pipework; stockpiling; and water course and drainage re-alignments. Temporary and permanent track construction, temporary site compounds, material storage and vehicle presence can all add up to reduce visual amenity on a site, even on a temporary basis, particularly in landscape designations (National Scenic Areas) or in wild land areas. Tracks specifically can be a significant visual intrusion in the local landscape.

How the track is designed and constructed in the topography, including route, material use, width, passing place location and verge formation can help minimise the impacts of the scheme.

Central vegetated strips along the length of a track can significantly reduce visual impact. Minimising exposed areas of ground, efficient and tidy working and limiting un-necessary plant and infrastructure, as well as the sensitive siting of stockpiles can help mitigate impacts during this period.

2.3 Weather

Since the winter months are generally wetter, there will be additional challenges in terms of managing run off and storm events. Snow and ice cover will restrict access and increase risks on site. Failure to plan for flood events can result in considerable damage on site, construction delays and pollution. Drainage issues are discussed in Section 4 below.

Extended periods of dry weather can make it difficult to manage dust from vehicles and tracks, and vehicle movements may have to be limited. In these instances you should install suitable mitigation such as dust suppression sprays.

2.4 Requirements of wildlife and Timings of Works

You must take into consideration the time of year and scheduling of construction in order to minimise impacts on the surrounding environment. Therefore, you should be aware of the different issues likely to arise at different times of year, particularly in the context of planning for work that may disturb species e.g. breeding or roosting times, or from lighting requirements on site.

Protected species such as badgers, red squirrels, invertebrates, otters and bats are more active at different times of year, and information on this can be found on the standing advice pages of NatureScot (calendar). You should take particular care during the salmonid spawning and incubation period (Oct-May). At other times of the year, you may need to consider the presence of other species such as lamprey.

As filter feeders, freshwater pearl mussels are also extremely vulnerable to water pollution and engineering work in rivers – e.g. construction of weirs or deepening of pools. Ensure appropriate surveys have been undertaken to determine presence and mitigate impacts appropriately.

2.5 Riverbed disturbance

You should carry out any work in or near a watercourse at times of low flow and outwith spawning periods, with appropriate protective measures to minimise the opportunity for siltation, and after consultation with SEPA.

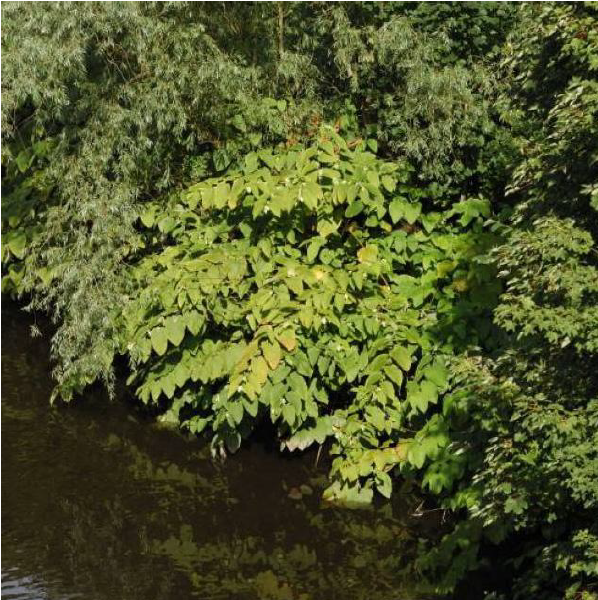

2.6 Invasive and non-native species

Managing land inhabited by a non-native species, in a timely and appropriate way, can help avoid:

- Excessive development costs

- Physical damage to buildings and hard surfaces

- Harm to the environment.

- Reputational damage

- Compensation claims

- Prosecution

Making sure staff can identify non-native species which are present on site (on land and in the water) can reduce waste costs and improve how you manage the site. An Environmental clerk of works can oversee the management of non-native species.

3. Environmental Clerk Of Works

An Environmental Clerk of Works (EnvCoW) monitors the compliance of a project and they frequently also advise on the effective environmental management during its lifecycle. There are two types of EnvCoW: auditors and advisers, the applicability of which are project dependent. The consenting body is responsible for determining which role it considers most suitable for a consented project, taking into consideration various factors, including significance of environmental risk and resource availability. However, a developer, or contractor can also engage an EnvCoW of their own volition, without the requirement of a planning condition, to help support the project by allowing it to progress more smoothly.

For details about the role of the EnvCoW, please refer to Good Practice During Wind Farm Construction which outlines key considerations of the role and benefits it can offer. Further details and context of the role, such as reporting mechanisms, skills and experience, are located in the Association of Environmental Clerk of Work’s Environmental Clerk of Works Good Practice Guidelines for Planning Authorities.

4. Construction drainage

You must ensure that the site is finished in such a way as to minimise risks post construction. This should be addressed through suitable construction practices, appropriate drainage, staff training, and monitoring of the site and environmental receptors.

Silt fencing is poorly located and is being very overwhelmed, providing no mitigation for silt pollution. Installed mitigation is not working at a point further upstream, closer to the source of the pollution.

Pre-earthworks drainage

This is the term generally given to cut-off/diversion ditches that are installed ahead of the main earthworks activities. They minimise the effects collected water can have on the stripped/exposed soils during earthworks. These drainage ditches intercept any surface run-off and direct it through the works without it mixing with “construction” drainage. They should be installed on the high-side of the areas that will be affected, immediately before construction operations begin. They should generally follow the natural flow of the ground and have a shallow gradient. Section 3.3 of SEPA's Good Practice Guide: Temporary Construction Methods provides useful information on their design and construction.

Site drainage management should be detailed in the CEMP. If the site requires a SEPA CAR construction site licence, the associated conditions will cover many of these aspects to ensure compliance with relevant water legislation. The Pollution Prevention Plan (PPP), written as part of the licence application and reviewed by SEPA, will provide the practical site detail.

Some general information is supplied below:

- Follow the CEMP and CMSs and any Pollution Prevention Plan (PPP) for the development;

- Install the drainage and mitigation measures appropriate for the area being worked. These must be in place before any construction work commences in that area;

- Treat all surface water from construction sites via appropriately sized, sustainable drainage systems. The appropriate CIRIA manuals (The SUDS Manual, Control of Water Pollution from Construction Sites, Guidance on construction SuDS and Control of Water Pollution from Linear Construction Sites) should also be consulted. Ciria’s ‘Guidance on the Construction of SuDS’ provides further guidance on the selection of the most appropriate treatment system ;

- Keep clean water flows clean by not allowing them to mix with construction drainage. (Page 16 of Good Practice Guide: Temporary Construction Methods describes this in more detail);

- Do not allow direct ditch discharge into watercourses, lochs, or sensitive wetlands;

- Minimise any effects on natural flora and fauna to ensure there are no impacts on any species, surrounding designated sites or sensitive habitats i.e. GWDTEs;

- Ensure flash wash-out events will not affect partially completed infrastructure sections; and

- Limit the size of excavations, such as minimising the length of penstock that will be excavated and construct in sections; limiting the amount of bare soil exposed at any one time.

You should consider the phasing of your development carefully. Your drainage system will be more effective in dealing with surface water run-off if sediment is prevented from getting into the water in the first place.

4.1 Direct impacts on the water environment

4.1.1 Intakes, outfalls and impounding works

The design and construction of a hydro scheme will require work in or near the water environment and can cause significant adverse impacts. Section 5 of SEPA’s Good Practice Guide: Intakes and Outfalls provides advice on issues to be considered when designing these structures. It will be a condition of the CAR hydropower water use licence that they are built in accordance with the design drawings.

Failure to build in accordance with the designs would constitute a breach of the CAR hydropower water use licence and could result in SEPA taking enforcement action, which may include requiring the removal of the structure. This would incur significant expense and delay.

4.1.2 Isolating working areas

It is usually necessary to isolate working areas during the construction of these structures. For details of measures you could take to minimise impacts, consult section 3.4 of SEPA’s Good Practice Guide: Temporary Construction Methods.

4.1.3 Watercourse crossings

You should give careful consideration to the location of watercourses and drainage pathways when determining the route of roads and other infrastructure. Avoid watercourse crossings where possible, but if they are absolutely necessary, section 3.7 of Good Practice Guide: Temporary Construction Methods provides the appropriate advice.

All watercourse crossings must be carried out in accordance with CAR. Authorisations range from general binding rules through to complex licences, and details can be found in section 5 of the CAR Practical Guide. You can also refer to good practice guide for river crossings for further guidance on this topic.

4.2 Indirect impacts on the water environment

4.2.1 Excavation Areas

Excavation activities are the primary source of sedimentation during construction. Due to the generally steep inclines and proximity to the water environment, designing and building effective drainage for hydro sites can be challenging; however, you must have drainage installed prior to works commencing. Follow the detail of the site CEMP, CMSs or the requirements of the PPP.

4.2.2 Peat management

Surplus peat management can be a key consideration of the construction phase. A Peat Management Plan should be drafted and followed. This should provide clear information on quantities, management and reinstatement of peat material and any waste issues that can arise during developments on peatland. Peat drains can be numerous and difficult to manage when they interact with infrastructure.

4.2.3 Access road and cable trenching

Where a hydro scheme is proposed in an upland area, you should consult the NatureScot publication Constructed Tracks in the Scottish Uplands and the floating road guidance FCE/SNH Floating Roads on Peat in addition to the drainage section of this guidance. You should also consult Good Practice during Wind farm Construction for more details on this.

4.2.4 Permanent track drainage

Appropriate measures (through the use of track edge drainage, side ditches and culvert options) are required to remove surface water from this area. Appropriate SUDS should be incorporated to reduce run-off rate and improve water quality. Refer to the SUDS manual or the local SEPA office for specific advice.

The type of material used for the construction of access tracks should be carefully considered to ensure that it is not easily crushed into fine particulates that can be washed offsite and result in pollution of the water environment.

4.2.5 Pumping

Where there is a significant build-up of water in the construction area you may need to pump this to avoid further build up, or to allow works to progress in that area. Section 3 of SEPA’s Good Practice Guide: Temporary Construction Methods provides further details on this. The disposal of the pumped water must comply with your SEPA construction site licence and PPP, and should not be to peatland or other sensitive areas.

4.2.6 Site compound

Most hydro developments need a site compound during the construction stage of the project. Where site facilities include mess and toilet facilities for the site workers, the effluent system design will depend on the sensitivity of the adjacent area. Where soakaways are proposed they should be kept as far away from watercourses as possible.

Note that any local abstractions of water for use in the compound should comply with GBR2 if less than 10m3per day. If greater than this volume, a CAR registration or licence will be required.

4.2.7 Oil storage

Bulk fuel and oil storage will normally be within the site compound. This should comprise suitably bunded areas, designed and constructed to meet the requirements of SEPA's Pollution Prevention Guidelines and the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (as amended). GBR 28 Advice on appropriate storage is available on page 18 of Pollution Prevention Guidelines 5: Works and Maintenance in or near Water.

4.2.8 Maintenance

Designing and installing the required drainage is essential, and appropriate monitoring and maintenance is also extremely important. You should consider the following points:

- Properly plan and map silt mitigation for the site. Number all the different treatment areas on the site, e.g. silt pond 1 (SP1), drainage ditch 2 (DD2) etc. This will prove useful when inspecting, recording and informing staff of problem areas;

- Plan and map the potential environmental receptors, for instance existing drainage ditches, small watercourses adjacent to or impinging on the site, sensitive habitats;

- Record details of the weather, inspections and maintenance carried out;

- Monitor and maintain all ditches, ponds, pipes, silt fences on a regular basis. Monitoring should be carried out in accordance with the weather conditions – for example, more frequent inspections should be carried out during and after periods of heavy rainfall;

- Check the watercourse(s) downstream of the construction area for signs of discolouration, sediment build up;

- Check any permanent settlement lagoons for leakage;

- Lower the lagoon water levels following periods of heavy rainfall;

- Check any ditches for blockages, and keep them clear and in good order. Any growing vegetation in ditches should be left as this will aid in the filtering of some of the sediments.

5. Environmental management plans

The use of Construction and Environmental Management Plans (CEMPs) to guide a development is very helpful to ensure consistency across a project and make everyone involved aware of their responsibilities and the sensitivities. It should prove that the risks to the environment from the construction of the scheme have been identified and appropriate mitigation put in place.

All staff must be made aware of the CEMP and carry out activities in accordance with it, and it must be clearly visible on site throughout the construction process.

The CEMP and any associated plans, such as a Peat Management Plan, must be specific to the site and in plain, easy to understand language. An accompanying site plan highlighting sensitive receptors and the location of all infrastructure on site should also be available (see Figure 1 below). Plans should be flexible and allow for fine tuning and amendment as situations arise and conditions change on site. Where changes are made, it may be necessary to consult the planning authority or SEPA to ensure compliance. For further guidance see Good Practice during Wind Farm Construction.

6. Reinstatement and restoration

The aim of reinstatement is to restore the original function (e.g. carbon store and sequestration) of the habitats on or around site i.e. wetlands or downstream water courses. This is to prevent or minimise impacts on the water environment, vegetation and soils - and species dependent on them - during the construction and operational phases of the scheme.

Habitat management and reinstatement measures should not have an adverse impact on sites of known archaeological or geodiversity interest.

Key points:

- All reinstatement should be carried out in accordance with the associated planning consent conditions.

- Reinstatement and restoration works should be identified in the CEMP, HMP, and associated documents. These will require due consideration throughout the construction process and could work hand-in-hand with the site’s surface water management plans, including any requirements outlined in a PPP.

- Suitable material for reinstatement must be stored and managed appropriately, near to source or the site compound but with suitable buffers from watercourses and other sensitive receptors. While storing peat, the different horizons of peat (turves, acrotelmic and catotelmic) should be kept separate with any turves facing green side up.

- Reinstatement of material should be completed as efficiently as possible.

- Restoration of a peatland can take from 5 to 30 years depending on the initial condition. Raising the water table to, or near to, the surface is critical to successful peatland restoration.

- When peat is reinstated this should match the surrounding peat horizons with catotelmic peat placed to the same depth as the surrounding catotelmic peat and peat turves placed on top, vegetation side up. Reinstated peat depths should match the surrounding topography to maintain the hydraulic flows and ensure the peat stays wet.

- Preserving the top vegetated turves and reinstating these right side up are most crucial for achieving a successful restoration.

- Long-term monitoring is essential to ensure successful restoration. Monitoring can also help to develop cost-effective techniques and methods by reducing wasted effort and allowing measures to be targeted at the right habitats / locations.

6.1 Track reinstatement

The area affected by the track should be limited to as narrow a corridor as possible, although there may be some benefit in widening the corridor where this allows engineered slopes to be blended into the surrounding landform. A narrow corridor may need steep cut and embankment slopes that would contrast with surrounding areas of hillside and could prove difficult to re-vegetate successfully. There must be a balance between; the sensitivity of the site; the steepness of the slope; erosion potential; and landscape and visual impacts.

By grading out the areas of cut and fill it will be possible to blend them into surrounding slopes, achieve more successful re-vegetation and reduce the risk of erosion. This will significantly improve the appearance of the track, though it could result in more extensive areas of habitat disturbance. Coir matting should be used on steep ground, and pinned if necessary.

6.2 Reinstatement techniques on bare peat

NatureScot has developed Peatland Action resources which links to reinstatement techniques.

7. Sustainable forest management

The Scottish Government expects all forestry plans and operations to comply with the UK Forestry Standards.

Developers intending to construct a hydro scheme which will affect a forest are encouraged to include Scottish Forestry in pre-application discussions at the earliest possible stage of the project. Additional information is available in the Guidance for implementation of the Control of Woodland Removal Policy.

7.1 Felling requirements

Any tree felling carried out without a felling licence or other valid permission is an offence unless it is covered by an exemption. It is therefore essential to check the area to be felled has either been formally consented, either through the development management process or through a felling licence issued by Scottish Forestry.

With regards to the use of trees and wooded material on development sites, you should refer to SEPA’s Guidance Note on The Use of Trees Cleared to Facilitate Development on Afforested Land. Mulching of significant amounts of forestry waste is unlikely to benefit from a waste exemption, and the local SEPA office can provide advice on this.

8. Recreation and access

Sites chosen for hydro-electric development are often used for outdoor recreation. The development could be an opportunity to create a legacy of improved provision for outdoor recreation.

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 (LRSA) establishes statutory rights of responsible access on most land. These are accompanied by rights of way that apply to particular routes and are established under common law. Scottish access rights include crossing over land and non-motorised recreational activities like walking, cycling and horse riding, and will normally apply across the whole area of a planned development.

Access rights include non-motorised activities on inland water, such as canoeing.

The LRSA also places a duty on land managers to manage their land and operations in a way that is responsible with regard to access.

8.1 Managing access during the construction phase

You have an obligation relating to the safety of the public under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and the Construction (Design and Management) Regulation 2007 (CDM). Access rights become suspended on land where construction work is being carried out, except for routes that are core paths or rights of way. The Scottish Outdoor Access Code underlines that restrictions should be kept to the minimum area and the minimum duration that is reasonable and practicable.

Management arrangements should be flexible enough to take reasonable account of public access requirements and adapt as the site develops. Access controls should be focused on where actual risks are present.

This ensures limitations on access are seen to be proportionate and credible by recreational users, and is likely to encourage greater compliance by the public and be more effective in meeting safety needs.

Effective communication with the public will be very important. You can use a range of mechanisms to manage access during construction, including informal, proportionate and short-term limitations on access, providing signposted alternative routes and active management of access where work is underway. It may be helpful to identify and advertise a key point of contact for members of the public regarding access issues. You should set out arrangements for access provision and management in an Access Management Plan.

8.2 Managing access in the operational phase

Any new access infrastructure installed on the site will require periodic maintenance, but access management is unlikely to have other long term implications. Public access will often share vehicular tracks with maintenance traffic. This position is common to a wide range of tracks used for forestry and upland estate management and is unlikely to require any special provision.

The Scottish Outdoor Access Code encourages managers to support public access across dams and respond to information requests about water discharges, to support access rights for canoeists.

9. Further information

Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Act (2005)

Pollution Prevention Guidelines relevant to construction

SEPA Water Activities guidance

Position Statement: Sediment Management

Guidance for construction site licences

The Use of Trees Cleared to Facilitate Development on Afforested Land

NatureScot: Hydroelectric Schemes and the Natural Heritage

FCE / SNH Floating Roads on Peat

NatureScot: Constructed Tracks in the Scottish Uplands

Forests and Water Guidelines (5th Edition)

Good practice during Windfarm Construction

Guidance for implementation of the Control of Woodland Removal Policy

Guidance on the assessment of peat volumes, reuse of excavated peat and the minimisation of waste

CIRIA Publications - available from the CIRIA website.

- Control of Water Pollution from Construction Sites – Guide to Good Practice (SP156);

- Control of Water Pollution from Construction Sites –Guidance for Consultants and Contractors (C532);

- Control of Pollution from Linear Construction Projects – Technical Guidance (C648);

- Control of Pollution from Linear Construction Projects – Site Guide (C649); Environmental Good Practice – Site Guide (C650);

- The SUDS Manual (C697);

- Guidance on the construction of SuDS (c768)

Contacts

Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA)

Association of Environment Clerk of Works