Ecological and practical interpretation of legal definitions: disturbance, breeding sites and resting places of beavers

Reviewed: March 2023

Policy Summary

Introduction

Beavers are protected under the Conservation (Natural Habitats &c.) Regulations 1994 as European Protected Species (EPS). The Regulations set out a number of offences in relation to all EPS but we need to be clear about how they apply to different species which often have very different characteristics and ecology. This paper has been developed to provide guidance to practitioners on what some of these terms mean in relation to beavers, and particularly in relation to what we consider could be offences in terms of disturbance to beavers and what constitute breeding sites and resting places and how they could be damaged or destroyed. A detailed consideration of ecological definitions and legislative interpretation of structures and of disturbance are provided in Annexes 1 and 2 respectively.

Please note that this is guidance only and that ultimately it is the role of the courts to interpret and apply the law. If in doubt you may wish to seek your own legal advice.

The Law

The Law sets out offences in relation to beavers and some of the structures or places they use. This includes offences in relation to disturbance of beavers in certain circumstances including while it is breeding or caring for young, as well as an offence of damaging or destroying a beaver’s breeding site or resting place.

Structures and places used by beavers

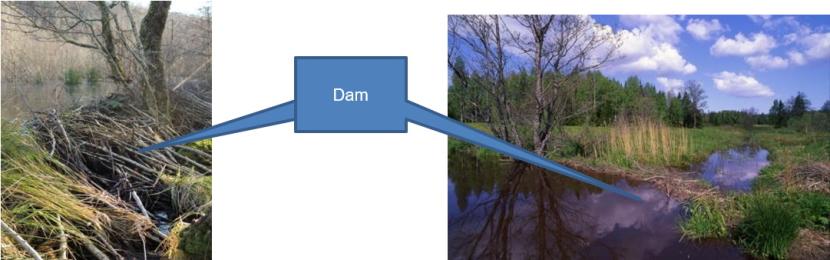

A breeding pair or family unit of beavers can build a number of different structures within a territory including simple and chambered burrows, lodges and dams. Some of these structures can provide an ecological function associated with survival and reproduction. Each territory may have some or all of these structures or may have multiples of one but none of another. Dams can be used for a number of functions including to raise water levels around lodges or burrow entrances to protect themselves.

Disturbance

Beavers demonstrate a capacity to tolerate and actively use human-dominated landscapes. We consider that disturbance offences are unlikely to occur as a result of normal day-to-day activities and land-use practices providing that those actions avoid damage to breeding sites or resting places (see below). This would include dams that protect them.

Which structures are breeding sites or resting places and what actions could damage or destroy them?

We advise that lodges or chambered burrows within an active beaver territory could constitute breeding sites or resting sites and could be considered such throughout the year. This means we consider them as being ‘protected’.

We advise that removal of dams or manipulation of dams protecting breeding sites or resting places is likely to affect the water levels around such sites and could constitute damaging or possibly destroying the site itself (or its ecological integrity) and/or disturbing beavers. Therefore, unless carried out under a licence, these actions could constitute an offence

We advise that the removal of any dam, other than one that has been very recently built (as a guide we would say less than 2 weeks old), risks damaging or destroying a breeding site or resting place or disturbing beavers. This is because it can be very difficult to know if a breeding site or resting place is present, and particularly chambered burrows, because they may not be visible. Expert advice may sometimes be able to ascertain this.

Summary

The table below provides an overview of the link between the Habitats Regulations offence, what we currently recommend requires a licence through our guidance for land-managers and the relationship to breeding sites and resting places.

|

Structure |

Legal definition |

Activities that could constitute an offence (unless sunder licence) |

Offence |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Lodge Chambered burrow Natal dam

|

Breeding site / resting place |

|

|

Annex 1 – Ecological and practical interpretation of legal definitions: breeding sites and resting places of beavers

1. Introduction

Beavers are protected under the Conservation (Natural Habitats &c.) Regulations 1994 as European Protected Species (EPS). The Regulations set out a number of offences in relation to all EPS but we need to be clear about how they apply to different species which often have very different characteristics and ecology. This paper has been developed to provide guidance on what some of these terms mean in relation to Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), and particularly in relation to what we consider to constitute breeding sites and resting places for beavers. This is important to provide guidance for practitioners and development of licensing advice and delivery. Please note that this is guidance only and that ultimately it is the role of the courts to interpret and apply the law. If in doubt you may wish to seek your own legal advice.

2. The Law

In summary, under the Habitats Regulations, it is an offence to deliberately or recklessly:

- Capture, injure or kill a beaver;

- Harass a beaver or group of beavers;

- Disturb a beaver while it is occupying a structure or place which it uses for shelter or protection;

- Disturb a beaver while it is rearing or otherwise caring for its young;

- Obstruct access to a breeding site or resting place of beavers, or otherwise to deny the animal use of that site or place;

- Disturb a beaver in a manner that is, or in circumstances which are, likely to significantly affect the local distribution or abundance of the species;

- Disturb a beaver in a manner that is, or in circumstances which are, likely to impair its ability to survive, breed or reproduce, or rear or otherwise care for its young.

It is also an offence to:

- Damage or destroy a beaver’s breeding site or resting place (note: this does not need to be deliberate or reckless to constitute an offence);

- Keep, transport, sell or offer for sale or exchange any wild beaver or any part or derivative of one (if obtained after 10 June 1994).

Note: the Regulations also list a number of exceptions and defences to these offences, but these are not considered here. For a full list of these the legislation itself should be consulted.

3. Beaver ecology

Beavers live in social family groups. Mating takes place in water between late December and the end of February. A family group consists of a breeding pair with a litter of kits from that year and the previous year (sub-adults). A breeding pair has a single litter of kits (usually 2-4) per year, born between April and mid-June. Sub-adults are non-breeding until they disperse and find a new territory and partner. Kits are dependent on their mother until aged around 62 days old1. By this time they have fully developed locomotion as well as grooming and defensive (escape) behaviours. They exhibit all the main social behaviours and can eat mainly solids, handle twigs/stalks, and peel bark. At around 2 years beavers become sexually mature and usually disperse from the natal territory seeking a mate to establish their own territory.

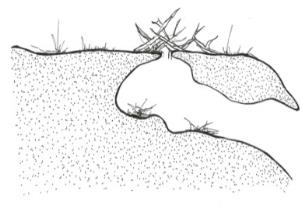

A breeding pair or family unit will defend their territory against other non-related beavers. They can also build a number of different structures within a territory including simple and chambered burrows, lodges and dams. Some of these structures provide an ecological function associated with survival and reproduction (i.e. shelter from weather and predators2, place to rest, to give birth (parturition), rear dependant young (kits) and provision food for overwintering). Each territory may have some or all of these structures or may have multiples of one but none of another. For example, not all territories have dams. Not all have lodges either, some may have lodge(s) and a mixture of simple and chambered burrow (s) and some may just have various burrows. Some territories will have a food cache of some sort to sustain the family group over the colder winter period. Dams can be used to raise water levels around lodge or burrow entrances to protect themselves or to protect food caches or improve access to food. Beavers can also dig canals to provide better access to foraging areas.

1 (Kit Dependency Period = 01 April to 16 August. This has been defined primarily as a management tool to avoid welfare impacts when carrying out (licensed) lethal control where kits aged 62days+ would reasonably be expected to survive were the adults removed.)

2 In Scotland, predators of beavers are likely to include foxes, pine martens and American mink

4. Breeding sites and resting places

While Article 12(1) of Habitats Directive explicitly refers to the protection of breeding sites and resting places of species listed in Annex IV(a), it does not define them. European Commission guidance3 provides generic definitions to help prepare species-specific definitions and considers that breeding sites and resting places are necessary for protection because they are crucial to the life cycle of the animals in question. It also states that the aim of protection is to safeguard the ecological functionality of those sites.

3 European Commission (2007), Guidance document on the strict protection of animal species of Community interest under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC, paragraphs II.3.4.b) (52)-(65)

Breeding sites are defined in the guidance as, ‘the areas needed to mate and give birth in and covers also the vicinity of the nest or parturition site, where offspring are dependent on such sites’. Areas required for courtship, mating, parturition and rearing dependent young may be covered but depends on the life history requirements of the species concerned.

The Guidance defines resting places “as the areas essential to sustain an animal or group when they are not active”, and “will include structures created by animals to function as resting places’’. Places may include structures and habitat essential for survival including those required for resting, sleeping or recuperation and hiding, protection or refuge. Beavers build a variety of specific structures (see section 5 below) for all of these elements and to provision the family group overwinter.

For wide ranging species such as otters or bats the guidance states that it may be appropriate to restrict the definition of a breeding site or resting place to a clearly delimited locality e.g. the roost of a bat or the holt of an otter. It is appropriate to follow a similar approach for beavers, where there are a number of key structures used or built by beavers that could either constitute breeding sites or resting places or be necessary to maintain the ecological function of such places.

Beavers use a lodge or chambered burrow to give birth in and rear young (kits) – this is referred to as the natal lodge or burrow. During this time, the adult male and sub-adults (i.e. kits of the previous 1-2 years) may make use of other structures elsewhere in the territory at different times, coming and going from the natal lodge. Some lodges or burrows are used year on year, some are not. Likewise, some may always be used for giving birth and rearing dependant young and some may not. Lodges or chambered burrows can also be important to beavers not just for breeding but for their survival particularly through the winter. In taking account of this associated temporal variance in structure occupancy and function, we would consider that such structures would constitute breeding sites or resting places (and are therefore protected) while a territory is active, and therefore regardless of whether they are physically occupied at a particular point in time. An absence of kit sightings during the Kit Dependency Period does not necessarily means they are not present.

Dams built by beavers can perform a number of different functions, including maintain a water level that will protect entrances to natal lodges or burrows that might be present. Given this, the removal of any such dam could compromise the ecological functionality of that site (i.e. meaning that it cannot or will not be used for breeding or as a resting place).

5. Practical definitions of breeding sites and resting places for beavers in Scotland

The following sub-sections and their corresponding tables detailed below provide details on the main types of structures or places used by beavers including their characteristics and ecological function. Guidance is then provided in reference to the legal definitions above, specifically if and how they may be legally protected.

5.1 Lodge

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site or resting place? |

|

|

Identification Practicalities and function of dams |

Lodges are sometimes obvious but can be difficult to find particularly amongst vegetation, scrub or woodland or if situated on a larger body of water. Expert advice and a systematic search may be necessary to discount presence of a lodge. Establishing occupancy and use may also require systematic monitoring. |

5.2 Chambered burrows

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site or resting place? |

|

|

Identification Practicalities and function of dams |

It can be very difficult to know if a chambered burrow is present at any particular site. Even if its presence can be confirmed it will also be difficult to ascertain if it is a natal burrow or not. Expert on-site advice or monitoring may sometimes, but not always, be able to help clarify likely presence or use of such a site. In practice this means that removal of anything but very recently built dams could damage or destroy the ecological function of any such site and therefore be considered as damaging or destroying a breeding site or resting place. |

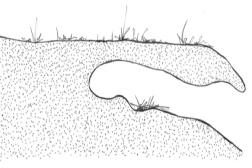

5.3 Simple burrow

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site or resting place? |

x Not considered as a breeding site because it is not specifically associated with parturition or dependant kits x Not considered as a resting site because simple burrows are not likely to be essential for survival |

|

Identification Practicalities and function of dams |

It can be very difficult to know if a simple burrow is present at any particular site because it may not be visible. If an entrance can be found and inspected then the absence of any chambers and short length would confirm this as a simple burrow. This may be difficult to ascertain unless there is particularly low water levels or if there has been a collapse/partial collapse of the roof of the burrow. Expert on-site advice or monitoring may sometimes, but not always, be able to help clarify likely presence or use of such a site. If the presence of a simple burrow is confirmed then removal of a dam protecting the entrance would not be considered an offence. |

6. Dams

Beavers will often, but not always, build dams, Dams can perform a number of functions including to open up areas to foraging. However, they often serve to stabilise water levels to protect burrows or lodges that could function as breeding sites or resting places by maintaining water levels around them. Removal of dams, and the resulting loss of water level, can therefore compromise the integrity (or the continued ecological functionality) of such sites.

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site or resting place? |

X Removal of dams that do not protect natal lodges or chambered burrows would be unlikely to result in damage or destruction of breeding sites or resting places (but note below re. practical difficulties in ascertaining this) |

|

Identification and practicalities |

Dams are usually very apparent if the watercourse can be appropriately walked/surveyed. Due to the difficulties in identifying whether or not breeding sites or resting places may be present (and particularly whether or not burrows may be present and ‘protected’ by the water levels behind any dam) we consider that removal of anything but very newly built dams runs the risk of committing an offence by damaging the ecological functionality of such sites. This means that dams should not be removed, other than under licence, unless;

|

7. Other structures or features made or used by beavers

There are a number of other structures or features made or used by beavers that do not in themselves constitute breeding sites or resting places. They are included here for completeness.

7.1. Temporary nest (or couch)

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site |

X Not associated with parturition or dependant kits |

|

Resting place |

X Temporary nests are not likely to be essential for survival |

7.2 Food cache

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site |

x Not specifically associated with parturition or dependant kits |

|

Resting place |

x Is not a place used for resting. |

7.3 Canals

|

Characteristics |

|

|---|---|

|

Function |

|

|

Breeding site or resting place |

x Not specifically associated with parturition or dependant kits and would not constitute a resting place |

Annex 2 – Ecological and practical interpretation of legal definitions: Disturbance

1. Introduction and legislative context

This guidance sets out SNH’s view of what might constitute disturbance to beavers in a range of circumstances. It places this within the context of the behavioural and ecological adaptations shown by beavers, drawing on experience from other European countries and regions where relevant. Where there may be a need to develop practical guidelines or best practice approaches, we will work with land managers and industry sectors to assist them in this process.

Please note that this is guidance only and that ultimately it is the role of the courts to interpret and apply the law. If in doubt you may wish to seek your own legal advice.

1.1 Legislative context

When the beaver becomes a European protected species (EPS), the Habitats Regulations1 will protect animals from various actions including disturbance under certain circumstances such that, it will be an offence to deliberately or recklessly:

- harass a beaver or group of beavers

- disturb a beaver while it is occupying a structure or place used for shelter or protection

- disturb a beaver while it is rearing or otherwise caring for its young

- disturb a beaver in a manner or in circumstances likely to significantly affect the local distribution or abundance of the species

- disturb a beaver in a manner or in circumstances likely to impair its ability to survive, breed or reproduce, or rear or otherwise care for its young

This paper considers only consider those offences that relate to disturbance or harassment impacts. It refers in places to breeding sites and resting places of beavers. These have been defined in Annex 1 but can be taken as being beaver lodges or chambered burrows but the role of dams in protecting them is also important.

1 In Scotland, the Habitats Directive is translated into specific legal obligations by the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994,as amended. This legislation usually referred to as the Habitats Regulations, covers requirements for species requiring strict protection, and introduces the term ‘European protected species’.

2. What is disturbance?

Article 12(1)(b) of the Habitats Directive prohibits deliberate disturbance of protected species especially at sensitive times such as during their breeding periods or when they are rearing young. It does not define activities that could cause illegal disturbance for beaver since species vary ecologically, biologically and behaviourally in a given situation.

Guidance from the European Commission on the strict protection of animal species advocates taking a species-by-species approach when considering what constitutes illegal disturbance under the Directive, recognising that:

- some forms of disturbance will have little detectable impact on a species, but factors like the intensity, duration and frequency of repetition of disturbances, can transform a minor disturbance into a harmful one.

- different species will have different sensitivities or reactions to the same type of disturbance.

- factors causing disturbance for one species might not create disturbance for another.

- the sensitivity of a single species might be different depending on the season or during certain periods in its lifecycle.

Domestic caselaw also provides some assistance in that Article 12(1)(b) only gives protection to the species and not to habitats, and the prohibition relates to the protection of the ‘species’ rather than specimens of species. In addition, whilst there is no requirement for the disturbance to be significant for an offence to be committed, some negative impact on the species is required to judge whether it constitutes a prohibited disturbance of the species.

Article 12(1)(b) is transposed into Scots law by regulations 39(1) and (2) of the Habitats Regulations 1994 (as amended) which detail certain circumstances in which EPS can be disturbed as previously outlined in section 1.1 above.

3. Behavioural and ecological context of beavers

The behavioural and ecological adaptations displayed by beavers are of particular importance when considering disturbance. Beavers are a semi-aquatic mammal very much hefted to freshwater with the majority of their activity within 20m of the bank. Their diet is diverse and seasonal, utilising aquatic and herbaceous vegetation which allows them to occupy a range of habitats including, although not necessarily dominated by, riparian woodland. They build a number of different structures (e.g. lodges, burrows, dams, canals, food caches) using lodges and burrows to shelter, rear young, overwinter and seek protection from predators. These structures are robust with the only access, usually through an underwater entrance(s) and will have some form of sub-surface burrow. Beavers are excellent swimmers and are able to dive underwater for up to 20 minutes. They possess therefore a number of physiological adaptations that allow them to avoid predation and mediate disturbance.

They have established territories in many urban landscapes with suitable habitat including a number of cities across Europe such as Bratislava, Trondhiem, Berne, Munich and Vienna. They occupy a range of natural as well as heavily-modified freshwater environments such as ornamental and fish ponds, canals, recreation areas and agricultural and forestry ditch systems, much which are associated with anthropogenic activity. A number of experienced specialists, from a range of European countries and regions have been contacted, and asked whether land management practice and use (e.g. forestry and agricultural operations) are influenced by the presence of beavers, particularly during the breeding season. In Bavaria, for example, forestry operations are considered unlikely to disturb beaver and as such disturbance-free protection zones are not used, nor are they applied to agricultural operations. Further evidence from a range of countries indicates that disturbance-free protection zones are not routinely used as a management tool for beaver (see Annex 1), which aligns with our own assessment that this particular method is not necessary as standard practice for beavers in Scotland.

These examples highlight that in many instances, beavers appear undisturbed by the presence, activity and noise generated by people and associated industry, recreation and other municipal activities. They demonstrate a capacity to tolerate and actively utilise human-dominated landscapes where they may readily establish territories, modify habitat and create structures for shelter and protection or for water level regulation all of which sets them apart from many other species.

4. Disturbing a beaver

Disturbance has been defined for a number of other species in Scotland. The Scottish Marine Wildlife Watching Code was specifically developed to minimise disturbance to cetaceans (EPS) as well as seals, basking shark and seabirds. Much of its definition of disturbance is analogous to beavers:

- The result of direct or indirect interaction with people that changes the behaviour of any animal or changes the environment, which in turn affects the well-being or survival of an animal in the short, medium or long-term.

Whilst the law does not define disturbance in relation to beaver, and it is for the Courts to assess whether an offence has been committed as a result of an activity, it is possible to give broad examples of disturbance and what might constitute an offence under the Regulations which take account of the distinctive behavioural and ecological adaptations described previously.

For beavers, disturbance would be likely where any human action leads to a change in beaver behaviour or activities which has a harmful impact on individual welfare/survival and or dependent young. Beavers routinely demonstrate a capacity to occur in and adapt to areas with major human development and industry and tolerate high levels of activity. Disturbance to beavers would not include for example, infrequent, short term responses e.g. startle response where a beaver might swim away from walkers using a riverbank footpath perhaps, as this would not result in a longer term behavioural changes or welfare impacts.

Specific examples of actions that might amount to illegal disturbance where there is an effect on welfare and survival (including local distribution and abundance of animals) are difficult to predict in advance as they are reliant on the specific circumstances and tolerances inherent to a particular individual or family group at that moment in time. However, there are a number of broad principles that apply to the type and level of action or activity that would be necessary to cause disturbance to beavers. These are outlined in the sections below with respect to the individual offences.

4.1 Deliberate or reckless disturbance

Regulation 39 (1) b makes it an offence to deliberately or recklessly disturb a beaver. Deliberate disturbance refers to the intentional act knowing that it will or may have a particular consequence, i.e. disturbance of the beaver. So, anyone carrying out certain activities which they consider likely to cause disturbance of beavers could very well be committing an offence under the Habitats Regulations. There has been considerable case law associated with what constitutes ‘recklessness’ and while ultimately only a court can definitively decide whether or not a particular action was reckless, it would appear to arise:

- if a person was aware of the likelihood that disturbance would result from his actions, but proceeded with the action regardless of its consequences; or

- if a person undertook an action in circumstances where any reasonable person could be expected to have foreseen the potential for disturbance but proceeded without regard to the consequences.

4.2 Harass a beaver or group of beavers

Beavers are particularly tolerant to human activity, as previously discussed. Some activity or circumstances may cause a beaver to temporarily alter its behaviour i.e. stop feeding, swim away, dive, change direction etc, none of which would have an impact on welfare or survival. However, action which is of a repeated and sustained nature could go beyond a temporary change, and so amount to harassment, and may result in impacts to welfare or survival.

4.3 Disturb a beaver while it is occupying a structure or place used for shelter or protection

Beavers build a number of different structures in which they can shelter, seek protection, give birth and raise young. They will usually have multiple examples of these breeding sites and resting places in a single territory. Frequency of use, ecological function and speed of construction varies for each of these structures. Beavers can build short burrows (with no end chamber) quickly in a few hours, whereas a more complex burrow or lodge takes longer. They will utilise short burrows perhaps for a few hours during a single night, or temporarily for a few weeks / months and will also use a lodge/chambered burrow for extended periods in which to give birth and rear young (kits) or to overwinter as a family group.

Action or activity that prevents a beaver from seeking shelter or protection from one particular structure may not necessarily have an impact on welfare or survival if other structures are available. Where a beaver is actively flushed repeatedly or access is prevented to all of these structures, or to one which serves a key ecological function (e.g. breeding site or resting place), then this could potentially result in impacts to welfare and survival. And as such, may disturb a beaver while it is occupying a structure or place used for shelter or protection.

4.4 Disturb a beaver while it is rearing or otherwise caring for its young

Beavers use a lodge or chambered burrow in which to give birth and raise their young, which are dependent on their mothers for the first few months. While they are known to move their kits to different structures, perhaps in response to sudden water level rise, this is more likely to be exceptional. Removing a female that has given birth, preventing access to a natal lodge/chambered burrow where kits are located, or damaging a natal structure (breeding site which may include a natal dam) could result in impacts on welfare and survival and as such may disturb a beaver while it is rearing or otherwise caring for its young.

4.5 Disturb a beaver in a manner or in circumstances likely to significantly affect the local distribution or abundance of the species

Beavers need access to certain base requirements such as freshwater, suitable habitat in which to feed and build shelter and other associated structures e.g. dams, food cache. Preventing access to many of these is likely to significantly affect the local distribution or abundance.

4.6 Disturb a beaver in a manner or in circumstances likely to impair its ability to survive, breed or reproduce, or rear or otherwise care for its young

Beavers need access to aquatic and herbaceous vegetation in order to survive. During the winter much of this vegetation is reduced and so they rely on more woody material that has usually been collected by the family group during the autumn months and stored in a food cache(s). This cache is located close to the lodge or chambered burrow that the family group will overwinter in. Food caching can therefore be an important factor in surviving the winter, and ensuring sufficient body condition to be able to breed the following year. Any activity that prevents this behaviour or removes the cache could impair the beavers’ ability to survive and reproduce and care for their young.

4.7 Conclusion

In summary, disturbance impacts to beavers are unlikely to occur where human action avoids physical damage to key beaver built structures (i.e. breeding sites and resting places) or the dams protecting them and allows access to these and associated suitable foraging habitat, and that avoids any interruption of normal ecological behaviour that goes beyond a short-term temporary period.

5. Practical advice

The adaptive abilities of beaver, referred to above, are fundamental when considering what activities may disturb beavers and therefore what practical steps may be necessary to minimise the risks. Experience sought from a range of countries and regions across Europe indicates that disturbance-free protection zones are not routinely used as a management tool for beaver (see Annex 3). Instead, the advice outlined in section 3 above should be used as a key starting point by land managers when undertaking activity in close proximity to beaver built structures (i.e. breeding sites and resting places) and when thinking about how activity may negatively influence the normal ecological behaviour of beavers. SNH will work with land and fisheries managers across sectors to assist them in this process, as required.

Annex 3 – Disturbance: Experience from Europe

Disturbance distances are often used as a management tool to minimise the impact to sensitive bird and mammal species from human activity, most notably built or renewable development or forestry operations. This usually makes use of disturbance-free protection zones often around the species place of shelter or breeding site. The distance used is specific to the individual species tolerance to the human activity and their ecological requirements and takes into account the level of protection afforded to the species in question. Examples include badger, wildcat, white-tailed and golden eagles as well as other EPS species such as otter and cetaceans. SNH were asked whether a disturbance distance zone would be applicable to beavers.

Understanding how disturbance of beavers is dealt with elsewhere in Europe is helpful, particularly in assessing whether the use of disturbance distance zones are applied for beaver. A number of European specialists were asked whether land management practice and use (e.g. forestry and agricultural operations, infrastructure / development and recreation / tourism) are influenced by the presence of beavers, particularly during the breeding season. Details were requested on any disturbance distance zones, or alternative approaches, that are used.

Switzerland (not in the EU and therefore not subject to the legal requirements of the Habitats Directive directly), was the only example where a zone was specifically used to minimise disturbance from felling activity, where a protective zone is placed around a lodge or burrow (approx. 2-3x tree height) where no tree felling is advised, mostly to avoid impacts from trees falling on them (pers. comm. Christof Angst1). However, in Bavaria, Germany, for example they do not use zones for forestry operations as they believe that beavers are unlikely to abandon burrow/lodge (pers. comm. Gerhard Schwab2).

A number of the countries contacted have legislation or policy that tends to minimise the overlap, and therefore potential conflict, between certain land use, built development and beavers primarily due to the restricted activity of beavers most of which is within 20m of the river bank. This removes therefore the need to routinely manage the risk of disturbance. Examples include:

- Bavaria - policy of no built development on rivers, creeks, floodplains. Payments are given to farmers who do not farm (or improve) within 5m of the river bank. In other parts of Germany, a mandatory unfarmed 5m buffer strip from the river bank is required (pers. comm. Gerhard Schwab).

- Denmark - 150m ‘protection line’ buffers from the river bank are applied to lakes with a surface area >3ha or other registered watercourses, within which the placement of building / caravans etc is prohibited. Farming / building is prohibited in rural areas within a 2m riparian zone along open and natural watercourses and lakes (pers. comm. Henning Fjord Aaser3)

- Switzerland - No built development is allowed within 6-12m of the riverbed depending on width of river (pers. comm. Christof Angst).

There were some specific circumstances where zones were used in some regions/countries, however these were more about minimising the remote risk of injury to people rather than protecting beavers per se:

- Bavaria – Swimmers to avoid (> 50 m) beaver lodges with young in early to mid-summer to remove the remote chance of being bitten (pers. comm. Gerhard Schwab)

- Switzerland - Swimmers advised to keep their distance from beavers to avoid potential for injury (pers. comm. Christof Angst).

1 Biologist Centre Suisse de Cartographie de la Faune (CSCF)

2 State Beaver Manager, Southern Bavaria

3Chief Adviser, Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark

Some counties contacted (i.e. Norway and Switzerland) are not within the EU and therefore do not need to apply the Habitats Directive, nevertheless their experience is still useful.