A Biodiversity Metric for Scotland's Planning System - Key Issues consultation

This consultation on the development of a Scottish biodiversity metric is open until Friday 10th May. Responses should be submitted through the Scottish Metric Issues survey. If you have difficulties submitting comments, or questions about this consultation, please email [email protected]

1. Introduction

This paper outlines work that NatureScot is undertaking to develop a biodiversity metric for Scotland’s planning system, to support delivery of National Planning Framework 4 policy 3(b). This work has been commissioned by the Scottish Government.

This paper alerts stakeholders and anyone interested in the development of a biodiversity metric for planning to the scope of the work that is to be undertaken. It provides an opportunity to contribute to this work. It invites comments on the key issues and priorities that have been identified by NatureScot at this stage. Details on how you can contribute your views are provided in section 4.

This paper does not propose solutions or reach conclusions on specific aspects of the Scottish biodiversity metric to be developed, as these are yet to be fully assessed. While work on developing a Scottish biodiversity metric is ongoing, we highlight here the advice set out in the Scottish Government’s Draft Planning Guidance: Biodiversity.

"4.12. In the meantime, the absence of a universally adopted Scottish methodology / tool should not be used to frustrate or delay decision making, and a flexible approach will be required. Wherever relevant and applicable, and as indicated above, information and evidence gathered for statutory and other assessment obligations, such as EIA, can be utilised to demonstrate those ways in which the policy tests set out in NPF4 have been met. Equally, where a developer wishes to use an established metric or tool, the planning submission should demonstrate how Scotland’s habitats and environmental conditions have been taken into account. Where an established metric or tool has been modified, the changes made and the reasons for this should be clearly set out."

1.1 Background

Scotland’s National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) places the twin climate and nature crises at its heart. One of its key themes is improving biodiversity, reflecting one of the six national outcomes – “securing positive effects for biodiversity” – that the national planning framework must address. Key to delivering this is NPF4 policy 3, which aims to protect biodiversity, reverse biodiversity loss, deliver positive effects from development and strengthen nature networks.

Policy 3(b) includes a requirement for all national, major and EIA development to include “significant biodiversity enhancements” that leave nature in a “demonstrably better state than without intervention”. NPF4 does not specify a particular approach for demonstrating biodiversity enhancement other than requiring best practice methods to be used. In the absence of an established Scottish metric a range of approaches are being adopted, potentially leading to confusing or conflicting outputs depending on the particular methodology used. Ultimately this could undermine delivery of NPF4 objectives.

One approach that has been widely applied in Scotland (either with or without adaption), is England’s biodiversity metric tool (often referred to as the ‘Defra metric’ or England’s statutory biodiversity metric). This was developed to deliver biodiversity net gain requirements under England’s planning system, and was subject to review by Scottish Government commissioned research into Approaches to measuring biodiversity in Scotland. This research concluded that, with refinement, England’s metric could be adapted for planning and development use under Scotland’s planning system. While the research examined a, now superseded, version of England’s metric (version 3.1), its findings and conclusion are considered to remain valid and applicable to the metric’s current version.

An overview of England’s statutory biodiversity metric is provided in Annex A. An understanding of its broad approach and component parts for assessing biodiversity will aid understanding of the issues identified in this paper. This paper does not discuss the detail of its methodology, and the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs pages of the UK Government website should be referred to for this.

1.2 The Scottish Government's Commission

The Scottish Government’s Planning, Architecture and Regeneration Division have commissioned NatureScot to develop a Scottish biodiversity metric that supports delivery of NPF4 policy 3(b). The commission’s requirements include:

- drawing on the 2023 SRUC review of Approaches to measuring biodiversity in Scotland, and existing practice and experience in Scotland;

- testing approaches across a range of development types (including onshore wind and housing);

- consulting on draft outputs prior to finalisation; and

- establishing a metric suitable for use within the existing Scottish statutory and policy planning framework

The metric will only apply to development on land (including the inter-tidal), and not the marine environment.

The commission’s focus is on adapting England’s statutory biodiversity metric to better reflect Scotland’s different legislative, policy and environmental context. England’s statutory approach prescribes that a mandatory level of biodiversity net gain (calculated by the statutory biodiversity metric) is able to be delivered before planning consent can be granted. Scotland’s policy led approach to delivering biodiversity enhancement is less rigid, with the policy requirement to be considered within the overall planning balance. Scotland’s metric must therefore be suitable for informing professional judgement and evidence-based decision-making when consenting development.

England’s metric is a tried and tested approach that has been refined through a number of formal iterations, in addition to being adapted independently by others. The 2023 SRUC review examined the metric’s approach and main components, and sets out 17 recommendations to improve its application in Scotland. These address:

- omission – of Scottish data or a methodology that needs to be filled;

- adjustment – to better reflect the Scottish environment and policy context;

- improvement – to strengthen the robustness and transparency of the metric; and

- support – to ensure the skills and capacity required are available.

Many of these are discussed in section 2, with more detail to be found in the SRUC report.

The commission’s final outputs will include:

- a Scottish biodiversity planning metric tool (hosted on the NatureScot website), which is based on current understanding of science and evidence, clear and transparent in its workings, accessible and easy to use by relevant professionals with outputs understandable by decision makers, and which informs siting and design of development as well as evidence-based decision making;

- a user guide supporting the metric (together with any supporting information); and

- recommendations on any requirements for maintaining and updating the metric and supporting information.

Stakeholder Engagement

Having been widely applied voluntarily across the UK for a number of years (and now mandated in England), there is a range of experience in applying England’s metric to learn from. The commission will draw on this existing knowledge base (particularly of the English metric’s use within Scotland), through desk study, case studies and seeking the views of stakeholders. NatureScot is keen to hear the views of planning, development, land management, professional, NGO and research interests, and learn from the experience of applying England’s metric.

This issues paper is the first opportunity to provide comments on the range of issues initially identified, and consider if there are any additional issues that require consideration. There will be further opportunities to contribute to the development of the Scottish metric as the work progresses. These future opportunities include:

- an initial roundtable discussion with a representative group of key stakeholders;

- input through established fora, including the Scottish Government’s Biodiversity Technical Advisory Group, the Peatland Expert Advisory Group, and the Linear Infrastructure Environmental Management Group (other relevant groups may be identified through the course of this work);

- contributing to testing application of the metric across a range of development types;

- open ‘invitations to comment’ published on NatureScot’s website; and

- targeted discussions with stakeholders bringing specific technical expertise or experience to an issue.

Updates on the work will be provided on the NatureScot website at key stages, signalling emerging thinking and approach, particularly where this will support best practice in the interim period before a Scottish metric is established. It is intended to complete the work within 12 months, although there are unknowns with the complexity and scale of work that may be required on some of the metric’s components.

2. Key Issues

The SRUC report provides a good starting point and analysis for identifying the range of issues that will need to be addressed when adapting England’s metric for Scotland. These, together with other issues identified from our own understanding of the metric, suggest the following issues require examination.

2.1 The principles and rules underpinning the metric's approach

England’s metric sets out four metric rules and nine principles to guide its use and application, and a set of ‘trading rules’ determining levels of habitat compensation. These are complemented by working practices set out in the guidance and supporting information on the UK Government website, such as when trading rules do not apply, and the treatment of habitats within the planning application (‘red line’) boundary. Together these frame how the tool is applied in practice.

The metric rules, principles and trading rules will require review to ensure they achieve the best outcomes for Scotland. This will include the need for any clarification on how they should be interpreted and applied, or additional rules or principles established.

The SRUC review notes the renewables industry concern with the English metric’s approach to calculating biodiversity uplift based on a baseline incorporating all habitats within the planning application’s red line boundary. Wind farm sites can incorporate an extensive area within their boundary (with upland sites often including irreplaceable peatland habitat), large areas of which may not be impacted but would still trigger a requirement for an uplift in biodiversity.

The principles, rules and working practices that underpin the metric’s use will all be reviewed for their applicability in Scotland, and ensure they enable the most appropriate biodiversity enhancement to be delivered.

2.2 The habitat classification system

England’s metric is founded on the identification of individual habitats, which drives the subsequent calculation of biodiversity units. It uses a range of habitat classification systems, in addition to a few habitats stipulated by the metric itself (see Table 1).

Table 1: Overview of the habitat classification systems used in England’s statutory biodiversity metric

| Broad Habitat | Classification system | Geographic Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Most terrestrial habitat | UKHab Level 4 | UK wide |

| Lakes | Water Framework Directive Lakes typology UK | European |

| Intertidal, coastal & shore habitats | European Nature Information System (EUNIS) Level | European |

| Waterways | UKHab with Ditches / Culverts being metric specific | UK wide |

| Green roofs, Urban trees | Metric specific | UK wide |

| Hedgerows | Metric specific (draws from the Hedgerow Survey Handbook) | UK wide |

Most terrestrial habitats are based on the UK Habitat Classification System (UKHab), using UKHab Level 4. While this level aligns with UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) Priority Habitats, Level 5 is typically required to identify Habitats Directive Annex 1 habitats. Level 4 results in the amalgamation of a number of habitats of different value, so the higher biodiversity value of some habitats is not readily recognised. The SRUC review also notes that although the metric includes a Technical Supplement listing Annex 1 habitats against the Level 4 classification, it is considered inconsistent and incomplete.

To assist ecologists more familiar with applying the Phase 1 Habitat Classification system, the metric includes an option to input habitats using Phase 1 data. A correspondence table then translates these to the UKHab classification. The SRUC review recognises the difficulty of translating different habitat classification systems. But it considers the Phase 1 / UKHab correspondence overly simplistic, typically making single links between the two classifications, and some translations being considered inappropriate (which will result in erroneous estimations of biodiversity units).

UKHab does not appear to be as widely applied in Scotland as in England (reflected in concerns with the limited capacity of trained UKHab surveyors in Scotland), and there is some debate about how well it captures all Scottish habitats. It is also the case that for developments requiring a more detailed ecological assessment, the National Vegetation Classification (NVC) is commonly required. There is no correspondence table within the metric translating NVC to UKHab, which may result in dual surveys being undertaken with the associated inefficiencies this brings.

Further consideration of the most appropriate habitat classification systems underpinning all aspects of the metric will be required, including the review of correspondence tables to ensure appropriate translation between classifications. Ensuring the selected approach is able to be delivered with appropriate capacity in Scotland, and integrates with established practice, will be important.

2.3 Irreplaceable Habitats

Irreplaceable habitats are habitats which are very difficult (or take a very significant time) to restore, recreate or replace once destroyed. This is a reflection of their age, uniqueness, species diversity and / or rarity. There is no formal list of Scottish irreplaceable habitats, but England’s metric identifies ancient woodland, ancient and veteran trees, blanket bog, limestone pavements, coastal sand dunes, certain saltmarsh habitats and lowland fens as irreplaceable.

The metric’s approach is to set aside any irreplaceable habitats that are impacted by a development, removing them from the metric’s calculation and instead requiring them to be given bespoke consideration. This approach reflects the impossibility of achieving a net gain for habitats considered so difficult to recreate and of such high value. Irreplaceable habitats that are not impacted by a development, and therefore continue as existing or are enhanced, are included within the tool.

The SRUC review considered that all irreplaceable habitats should be recognised in a Scottish metric. It noted that some, such as ancient woodlands and veteran trees, are not classified as a habitat in their own right and are therefore not readily identified in a habitat based metric tool. The application of existing spatial datasets (such as the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland and Caledonian Pinewood Inventory), in the tool may allow for the capture of relevant irreplaceable habitats.

The approach to irreplaceable habitats within the tool needs to be reviewed and confirmed, and a definitive list of which Scottish habitats are considered as irreplaceable needs to be produced and agreed.

2.4 Habitat Distinctiveness

Habitat distinctiveness seeks to capture differences in the conservation value of different habitats. For all habitat types, the higher the level of distinctiveness that is assessed, the larger the multiplier that is applied.

The English metric varies its approach and criteria applied in rating distinctiveness between the different broad habitat types. For example, terrestrial habitat distinctiveness is based on habitat type, conservation status of the habitat, its rarity and potential vulnerability (within the context of England). Intertidal and rocky shore habitats take into account the rarity and sensitivity of different substrates. Waterway habitats reflect their priority river habitat classification.

The SRUC review considered that the general approach of England’s metric is transferrable to Scotland, but adaptions would be needed. For terrestrial habitats Scottish data will need to present rarity within the Scottish context. For waterways, although England’s Priority Rivers map does not extend to Scotland, SEPA’s Water Classification Hub provides five condition categories that could be applied to distinctiveness.

The review also identified that some valued habitats are not currently recognised in the habitats included in the metric, and in filling these gaps an appropriate distinctiveness rating will need to be established.

The general approach of the English metric to distinctiveness will be reviewed but is likely to remain appropriate. A re-assessment of habitats applying appropriate Scottish spatial datasets will be required, followed by testing of the resulting rankings.

2.5 Habitat Condition

Habitat condition seeks to assess a habitat’s current quality against its ecological optimum state. This is based on the habitat’s physical attributes (e.g. vegetation structure), and biological attributes (e.g. the presence of positive and negative indicators).

To standardise the assessment of condition, England’s metric provides a condition assessment sheet for each broad habitat category, each with a set of criteria specific to that habitat. The criteria are simple statements which are answered with pass or fail (or in the case of intertidal and woodland habitats, a score of 1 to 3). The answers determine the habitat’s categorisation as either good, moderate or poor condition. Some habitats also include essential criteria which must be met if the habitat is to be considered to be of a certain condition.

Condition assessments are not required for a small number of habitats considered to be of low or very low distinctiveness, or in cropland habitats and a variety of arable field margins. These are automatically assigned poor condition.

The SRUC review notes that the metric’s habitat base results in limited recognition of species-based interventions, such as the provision of artificial nest sites for individual species. Recognition of these within the condition assessments, or expanding condition criteria to include a wider range of species indicators, could incentivise a broader range of biodiversity enhancements.

The SRUC review found the assessment criteria largely applicable to Scottish habitats, reflecting their basis in a number of UK standards. However the characteristic species identified were considered to require refinement (noting some species included have a restricted range), and the criteria based on the number of species present may need calibrating with Scotland’s (often harsher) environmental conditions. Expanding the list of negative indicator species for freshwater and intertidal habitats could also be considered.

The review also noted that the MoRPh methodology’s application to river condition may require refinement to better reflect Scottish rivers. The limited capacity of accredited MoRPh assessors in Scotland to undertake assessments was also highlighted.

The SRUC review also noted that condition criteria do not include pests and pathogens, other than for some woodland habitats. As other habitats can also be severely degraded by pests and pathogens, and the risk of this is increasing with climate change, it was considered that including pest and pathogens may improve the condition assessment.

The condition assessment criteria will be reviewed for each of the habitats to ensure they adequately reflect Scottish conditions and the pressures they face, and are refined where appropriate. The suitability and practicality of applying the MoRPh River Assessment methodology in Scotland will also be examined.

2.6 Strategic Significance

The strategic significance component seeks to capture the local significance of a habitat based on its location and habitat type. This is based on a habitat’s identification in a Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS), that are being prepared across England, or in an alternative strategy specified by the planning authority where a LNRS has not been published. Identification in adopted plans and strategies should help deliver established priorities.

The LNRS reflects England’s planning framework, without a direct comparable in Scotland. However some of the alternative strategies recognised in the metric’s guidance have a Scottish equivalent. The SRUC review also identifies Local Biodiversity Action Plans, Local Climate Change Strategies, Catchment Management Plans, Land use strategy pilots, spatial targeting of Agri-Environment and Climate Measures and opportunity mapping as potentially applicable.

The SRUC review also notes that while giving weight to actions in adopted plans and strategies is important, retaining some flexibility may be appropriate. This reflects that relevant strategies vary in approach and suitability, with many predating the NPF4 requirements. Allowing for actions that are not identified but nonetheless considered to be ecologically desirable (such as enhancing connectivity between habitats), will aid delivery of Scottish priorities and objectives. This may also mitigate the absence of ecological connectivity being directly accounted for in the metric (since it was removed from an earlier version).

While highlighting the role of strategic significance in helping to prioritise which habitats are created where, and contribute to nature networks, the SRUC review also considers the multipliers relatively low and therefore providing limited weight.

A review of which Scottish strategies are relevant to assessing strategic significance is required, along with the multipliers to be applied, to support delivery of established Scottish and local priorities for biodiversity.

2.7 Technical Difficulty Risk Factor

England’s metric takes into account the uncertainty in the effectiveness of techniques for creating or enhancing a habitat post-intervention. It applies a multiplier that reflects an ‘average’ assessment of the habitat’s ecological constraints and technical difficulty to achieve this. Differences in the risk between creating a new habitat or enhancing an existing one of the same type are reflected in different risk multipliers being applied for the same habitat.

The greater the difficulty, the smaller the multiplier that is applied. As this is a fraction of 1, its effect is to reduce the number of biodiversity units calculated. Technical difficulty needs to be considered in tandem with the temporal risk (time to target condition), as both impact the biodiversity units calculated.

The SRUC review concludes that the factors considered in allocating risk are comprehensive and relevant to Scotland. However risk multipliers may need refinement to account for different ‘average’ conditions in Scotland impacting on difficulty, such as restricted accessibility, greater exposure and high levels of deer browsing. Site conditions are also considered to vary more than in England, suggesting a single difficulty rating for each habitat may be less appropriate in Scotland. The ability to provide more flexibility and vary the multiplier in the Scottish metric, based on site specific issues and professional advice, could also be considered.

It is also noted that there is a need for the identified risk to be regularly re-appraised to take account of technological advances and reflect practical experience.

The metric’s approach to treating a change in broad habitat type as either creation or enhancement also requires consideration, as the respective multipliers can be very different. The SRUC review considers the approach needs to be clarified, and that additional guidance outlining what habitat change is appropriate would aid consistency. This could be more enabling of the restoration of valued degraded habitats. For example the removal of coniferous plantation from former blanket bog results in very different biodiversity units being calculated depending on the classification of the habitat and whether it is treated as an enhancement or creation.

The approach to identifying and assessing technical difficulty, and the multipliers applied, will be reviewed to ensure they reflect the Scottish context. Guidance on the consideration of habitat enhancement and creation will also be reviewed.

2.8 Temporal Risk Factor

England’s metric takes into account the average time it takes for a newly created or enhanced habitat to reach a specified target condition by applying a multiplier that reflects this time lag. Differences in the time lag attributed to different habitats reflect their ecological character, whether they are being created or enhanced, and the target condition being sought. For example, the creation of a habitat in good condition will take longer than achieving poor condition.

The longer the time lag to reach the intended condition, the smaller the multiplier that is applied. As this is a fraction of 1, the multiplier will reduce the number of biodiversity units calculated. Temporal risk needs to be considered in tandem with the technical difficulty risk factor, as both impact the biodiversity units calculated. When creating habitats this may result in a tendency to seek poorer condition habitats that are easier to achieve and within a shorter timescale if this results in more biodiversity units being calculated. This will discourage the creation of more valued (higher distinctiveness) habitats.

Where habitat is created or enhanced in advance of post-intervention, the metric tool adjusts the temporal multiplier to reflect the shorter time lag. In the opposite case of a delay in creation or enhancement, the time lag to target condition is extended, decreasing the multiplier and resultant biodiversity units.

The SRUC review questions the appropriateness of an average time to reach a target condition (similar to the technical difficulty multiplier). The variation in environmental conditions across Scotland, such as elevation, exposure and soil conditions, will significantly impact the time habitats take to develop. Similar to the technical difficulty factor, the ability in the Scottish metric to vary the multiplier, based on site specific conditions, proposed techniques and professional advice, could be considered.

The approach to identifying and assessing temporal risk (time to target condition), and the multipliers applied, will be reviewed to ensure they reflect the Scottish context.

2.9 Spatial Risk Factor

England’s metric seeks to encourage on-site delivery of biodiversity where possible, which is reflected in Scotland’s approach. It does this by applying a ‘penalty’ multiplier when habitat creation or enhancement is delivered off-site and outwith the same Local Planning Authority, National Character Area, Marine Plan Area or waterbody that the site sits within. If it is delivered in a neighbouring area a multiplier of 0.75 is applied, and beyond these a multiplier of 0.5. As these multipliers are a fraction of 1, these multipliers will result in a reduction of the number of biodiversity units calculated.

The SRUC review recognises that as the metric applies an English framework, appropriate Scottish equivalents require identification. Scottish planning authorities vary greatly in size, with English rural authorities generally smaller than their Scottish equivalent. The size range of Scottish authorities may not deliver the intention behind the approach, and alternative approaches require consideration including the application of Scottish Landscape Character Types or a simple distance multiplier.

An approach to factoring in spatial risk that reflects Scotland’s context and available framework will be developed. This should aim to support the delivery of established policy objectives.

3. Developing a Scottish Metric

NatureScot is keen to establish a metric suitable for Scotland’s planning system as soon as possible, building on the understanding gained from the development of England’s metric and the experience of practitioners applying its approach in Scotland. The tool will support delivery of NPF4 policy 3(b) through applying a consistent and proportionate approach to inform decision making, and delivering appropriate biodiversity enhancement.

The work will be taken forward in a phased approach. The first phase will address the foundations of the metric tool, along with prioritising peatland considerations to tie in with parallel work being undertaken by the Peatland Expert Advisory Group (to support delivery of the Onshore Wind Sector Deal). This includes:

- the principles, trading rules, approach and assumptions that guide application of the tool;

- the habitat classification system(s), watercourse / river assessment methodology, identification and treatment of irreplaceable habitats, and consideration of habitats within the ‘red line boundary’, that provide the tool’s building blocks; and

- the identification and treatment of peatland habitats in terms of their Distinctiveness rating, and Risk Factors applied by the tool.

The second phase of work will review each of the tool’s components, focusing on the issues highlighted in the SRUC report and identified by stakeholders. This includes:

- the approach to assessing Distinctiveness, consideration of relevant Scottish datasets to inform this, and appropriateness of the individual habitat multipliers;

- the appropriateness of Condition criteria in the Scottish context and multipliers by appropriate habitat experts;

- the approach to assessing Strategic Significance that is tailored to Scottish priorities and the supporting framework;

- the overall approach to assessing risk, and consideration of the Technical Difficulty Risk and Time Risk factors; and

- the approach to assessing Spatial Risk and associated multipliers.

The final phase of work will include consultation on the draft finalised tool, guidance and supporting information prior to publication on the NatureScot website. The requirements for maintaining and updating the metric tool in the future will be set out, and initial capacity building in support of the metric’s application provided.

4. Providing Your Views

For each of the nine components and issues identified in section 2 we are seeking views on:

i. Do you agree with the issue(s) identified?

ii. Are there any other issues relating to this aspect of England’s metric that we need to consider?

iii. If you have ideas or solutions for addressing the issues identified, please outline your approach.

On the phased approach and priorities for addressing the components of the metric:

iv. Do you have any comments on the phased approach set out, and priorities indicated?

Responses should be submitted through the SmartSurvey website by Friday 10 May.

If you have any difficulties accessing the SmartSurvey form, you can email: [email protected]

Annex A

England's Statutory Biodiversity Metric

This annex provides an overview of England’s statutory biodiversity metric, the adaption of which provides the starting point for developing a Scottish biodiversity metric for planning. It does not provide detailed information on its methodology and application. This, and guidance on its use, can be found on the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs pages of the UK Government website.

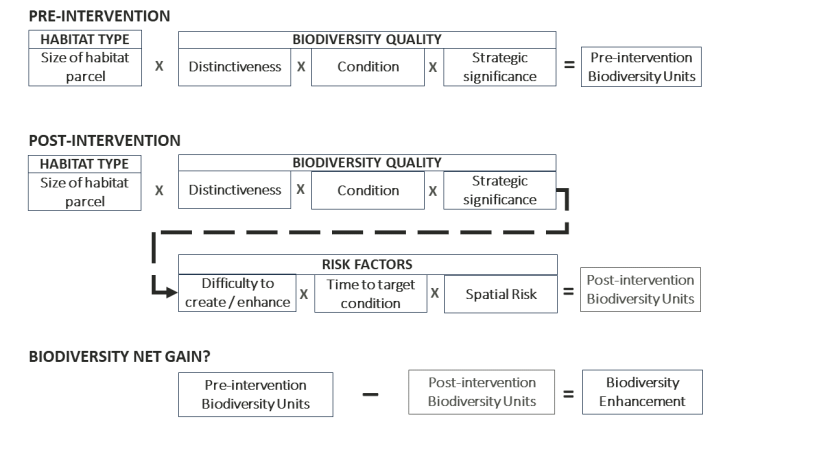

Under England’s planning system, most development (unless exempted) can not be granted planning permission unless it can show that it will provide at least a 10% uplift in the biodiversity value of the site (i.e. delivering ‘biodiversity net gain’). Biodiversity value is measured in standardised ‘biodiversity units’, which are required to be calculated using the statutory biodiversity metric tool. This is an Excel spreadsheet created tool, that provides a standardised approach to quantifying the level of biodiversity on a development site pre-intervention, and what is intended to exist following development (post-intervention). The tool is founded on habitats as a proxy for measuring biodiversity (rather than an alternative such as species or ecosystem health), and the application of a set of pre-determined multipliers. These multipliers have been established based on current scientific understanding and expert opinion of habitats under ‘average’ environmental conditions in England.

For the site in question, the metric seperately calculates the biodiversity value (in biodiversity units) of what currently exists pre-intervention, and what will remain or is planned to be established post-intervention. It does this by multiplying the area or linear extent of each different habitat identified on the site, by pre-determined multipliers for each of the metric’s component parts – Distinctiveness, Condition, Strategic Significance and three Risk Factors. The biodiveristy units calculated for the three different forms of habitat - area of habitat (ha), length of hedgerow (km) and length of watercourses (km) - are processed separately, and can not be summed, traded or converted between them.

For calculating biodiversity units for the baseline, a site’s habitats are identified and their condition is assessed. The habitat type identified determines the level of distinctiveness, and informs the level of strategic significance, to be applied. The extent of each habitat is then multiplied by the appropriate pre-determined multipliers (for distinctiveness, condition and strategic significance), to calculate the number of pre-intervention biodiversity units of the site.

This is repeated for the habitats that will exist post-intervention, but with an additional set of predetermined ‘risk factors’ applied to account for the uncertainty, time-lag and any separation between existing and future biodiversity. Each habitat type has pre-determined levels of difficulty assigned in either creating or enhancing them, and the average time required to reach a defined condition. The spatial risk factor is determined by where in relation to the development site the habitat is being delivered, penalising off-site in favour of on-site provision. Each of these risk multipliers are applied to the habitats that will be enhanced or created post-intervention (existing habitats that remain unchanged are not exposed to risk).

The difference in biodiversity units between the pre-intervention score and post-intervention score indicates whether biodiversity net gain will be delivered, and the scale of uplift that will be achieved.

To apply the metric tool, a competent person is required to identify and classify the extent of different habitats within the site and assess their current condition (based on ecological survey), and establish their strategic significance (based on a review of the Local Nature Recovery Strategy or alternative strategy). This establishes the pre-intervention score. They also need to establish what habitats will remain, be enhanced or created and the condition it is intended to achieve post-intervention, and the strategic significance of these habitats. Inputting this information in to the metric tool automatically assigns the pre-determined multipliers for each habitat in calculating the appropriate number of biodiversity units.

It is recognised that the metric has limitiations. While it is underpinned by ecological evidence and expert opinion, it is still applying a relatively simply and broad-brush approach to calculating change in biodiversity. Habitat as a proxy for biodiversity does not consider landscape structure, and the intricacies, complexities and functioning of ecosystems that biodiversity depends upon. Nonetheless the metric provides a useful tool for informing decisions on delivering the policy’s requirements when appropriately applied.