The Role of Protected Areas in Climate Change Mitigation/Adaptation Climate change and protected areas - 2020

CLIMATE CHANGE AND PROTECTED AREAS: IMPLICATIONS, OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

Purpose and Background

- This is a desk based review for the NatureScot Protected Areas Committee as part of its strategic review of “how best to deliver maximum value from Scotland’s protected area network in line with our statutory responsibilities and within budgetary constraints”.

- This paper considers:

- The implications of climate change on protected areas and the protected areas network.

- How protected areas currently help mitigate climate change.

- How we can minimise impacts of climate change on protected areas and maximise their contribution to tackling climate change.

- Challenges to implementation.

- With respect to the implications of climate change on protected areas this paper should be read in conjunction with the ClimateXChange report by Brooker et al. in 2014 which looked in detail at risks posed by climate change to notifiable features on our protected areas.

- In this paper ‘protected areas’ means the totality of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), European sites (Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Areas (SPA)) and Nature Conservation Marine Protected Areas (NCMPA). Appendix 1 provides summary details of the extent and nature of our protected areas resource, and relevant legislation and policy.

- The terms ‘climate mitigation’ and ‘climate adaptation’ are used in accord with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change definitions.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF CLIMATE CHANGE FOR PROTECTED AREAS AND THE PROTECTED AREAS NETWORK

- The global nature of climate change, and other major drivers of biodiversity loss (IPBES 2019) presents direct and indirect challenges to individual protected areas and networks of protected areas. As climate change progresses, our current protected areas will likely continue to represent nature across a wide range of physical conditions – across all parts, altitudes, and aspects of the country, and under diverse management practices. They may however cease to support the same quality of features they were selected for in the 1980s-2010s (e.g. the species composition of a habitat or community may change).

- Climate change is impacting upon biological and geological protected features, their function and management, and in both the marine environment and on land. We can expect to see further changes in the distribution of species and their habitats as the result of either gradual change in environmental parameters or severe weather events. Some changes will be direct e.g. a place becomes too hot/ wet/ dry for species to survive (alongside non-climate pressures); others will be indirect, e.g. through the impacts of other species through changes in competitive advantage (including invasive non-native species (INNS) and pathogens) or people responding to climate change.

- Climate change will increasingly challenge our ability to maintain our current range of protected areas features in the same places and conditions that they have been previously. More broadly it has the potential to adversely impact on the integrity of those sites, and the coherence of the wider network, as well as the ecosystem services they provide.

- Various initiatives have modelled future species distributions based on their climate envelopes (the geographic area with suitable climatic conditions) and how this will shift as climate change progresses. These indicate that some species will no longer occur in or near the protected areas for which they were designated in the 20th century (e.g. the Wallace Initiative provides interactive mapping of species distribution under different temperature change scenarios).

- Recording environmental change over many years is a challenge in itself. Monitoring and attributing observed changes to climate change is even more challenging due to confounding effects such as nitrogen deposition and the influence of management. We have recorded changes in which climate is likely to be playing a role e.g. changing wintering patterns of geese, prey distribution changes, breeding success of seabirds and duration extent of snowbeds (Rivington 2019). Extreme weather events also impact on our direct management of protected areas – e.g. flash flooding destroying infrastructure.

- To gain a better understanding of protected areas vulnerability to climate change, NatureScot and ClimateXchange completed a pioneering climate change risk-based assessment of terrestrial protected areas features (Brooker 2014). This identified our montane and coastal features, and wetlands in the central belt, as being at relatively higher risk due primarily to altitudinal shift, coastal retreat, drought and surrounding land-uses.

- Additionally, NatureScot and partners in the Dynamic Coast (Scotland’s Coastal Change Assessment) have mapped coastal boundary change over time and modelled future climate change informed scenarios, which indicate significant change in many coastal protected areas.

- The impacts of climate change on protected areas therefore present a number of challenges for future work in this area. The next sections consider the role of protected areas in climate change mitigation and subsequently on how we can minimise impacts and maximise beneficial contribution of protected areas to help tackle climate change.

PROTECTED AREAS AND CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION

- Our protected areas currently help to mitigate our climate impacts directly;

- as substantial stores of carbon (and other greenhouse gases) in soils and vegetation that, under different management, might easily be released to the atmosphere;

- as sequesters of atmospheric carbon, and

- by maintaining and supporting natural solutions to climate related issues, for example in flood attenuation.

- Many protected areas also support local production of food and materials and/or provide opportunities for people to connect with nature close to where they live – helping reduce transport and travel emissions.

- Quantifying the contribution of protected areas’ habitats to climate change mitigation is challenging and currently incomplete. Their contribution depends greatly on their ecological status and management – under different management habitats may be net sequesters or emitters of carbon and other greenhouse gases (e.g. Field et al., 2020). Despite many (at least terrestrial) protected areas being small in size, collectively they represent a significant proportion of our land and sea area – and therefore a potentially significant contribution to tackling climate change.

- Different habitats have different carbon storage capacities, which may be significantly influenced by their management (see Table 2). Our protected areas contain significant areas of carbon-storing habitats including peatlands (>350,000ha), woodlands (80,000ha), undisturbed soils, saltmarsh (5,500ha), marine burrowed mud (>193,810ha) and maerl beds (2,432ha) (data derived from Habitat Map of Scotland and the Geodatabase of Marine Features in Scotland).

- The extent of carbon stored in marine habitats and surface sediments of inshore MPAs has been estimated at 57.2 Mt (Burrows 2017) [For context, NatureScot’s operational emissions in 2018/19 were 1,073 tonnes CO2; and the top 10cm of marine sediments across the entire Extended Economic Zone hold c.1,515 Mt C (Smeaton 2020)]. We don’t have a comparable figure for terrestrial protected areas, but our understanding of the relative contributions of different habitats (e.g. Table 2, and Alonso 2012) is improving. Coupled with the understanding that better ecological health equates with lower emissions (e.g. Scottish Government 2015, s4.41), this provides a strong indicator of direction for immediate options and actions.

| Habitat | Vegetation | Soils | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Non irrigated arable land |

2.36 |

63.9 |

66.26 |

|

Bioenergy crops |

2.9 |

74.6 |

77.5 |

|

Green urban areas‐sport & leisure facilities |

8.32 |

91.3 |

99.62 |

|

Complex cultivation patterns, fruit trees, land principally occupied by agriculture, transitional woodland‐scrub |

14.7 |

88.4 |

103.1 |

|

Moors ‐ heathland |

7.11 |

103 |

110.11 |

|

Natural grasslands ‐ pastures |

3.1 |

121 |

124.1 |

|

Inland and salt marshes |

8.44 |

143 |

151.44 |

|

Coniferous forest |

59.1 |

107 |

166.1 |

|

Mixed forest |

78 |

124 |

202 |

|

Broadleaved forest |

111 |

162 |

273 |

|

Peat bogs |

7.15 |

576 |

583.15 |

- Current policy and management for protected features typically supports the long-term retention of this stored carbon by preventing destruction, disturbance and other land or coastal/marine management likely to cause the release of carbon. Due to the near absence of intensive agricultural, forestry and other land/ sea-uses, protected areas are generally not considered high contributors of carbon emissions – with the exception of peatlands in unfavourable condition.

MINIMISING IMPACTS AND MAXIMISING THEIR CONTRIBUTION(S) TO TACKLING CLIMATE CHANGE

Building Resilience and Climate Change Mitigation

- Our protected areas individually and collectively offer many opportunities to support greater climate adaptation by -

- building the resilience of nature,

and climate mitigation by -

-

- securing stored carbon, and

- increasing the sequestration of carbon.

- We must also consider how we will mitigate operational emissions by protected areas managers (including ourselves) and those we encourage to visit.

Building the resilience of nature

- Protected areas have been a key part of our long-term effort to help maintain a healthy, functioning environment - widely regarded as an essential measure in ensuring nature can adapt to climate change. Maintaining the health of protected areas features is regarded as a key factor influence on their resilience (Brooker 2014), and much effort has been spent improving the condition of protected features (e.g. to achieve the target of 80% of biological sites in favourable condition) (a Scottish Government National Indicator).

- For both terrestrial and marine protected areas adaptation there is a strong commonality (see comparison in Table 1) in the expressed needs for building resilience which can be abbreviated to – more, bigger, better and joined-up (Lawton 2010, recent work by the Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership (MCCIP)). MCCIP didn’t propose ‘more’ or ‘bigger’ but did propose flexible site boundaries and protection outside of sites for priority features.

| Terrestrial (Lawton 2010) | Marine (Summarised from MCCIP report cards)(S Cunningham, NatureScot) |

|---|---|

|

Improve the quality of current sites by better habitat management |

Maintain/restore features in MPAs Monitoring and management of Invasive Non Native Species |

|

Increase the size of current wildlife sites |

Flexible site boundaries |

|

Create new sites |

Completion of site designation programme |

|

Enhance connections between, or join up, sites, either through physical corridors, or through ‘stepping stones’ |

Management across regions, not in isolation |

|

Reduce the pressures on wildlife by improving the wider environment, including through buffering wildlife sites |

Reduce/remove pressures in MPAs Manage external pressures Protection outside of sites – of Priority Marine Features (PMF) |

|

- |

Monitoring and Research |

- The role of our protected areas in building these three arms of resilience is discussed below.

More and bigger protected areas

- Increasing the extent of land and sea managed for nature, provides more opportunity for larger, more diverse and more robust populations of species across more of their suitable ranges – making those populations and their communities more dynamic, and resilient to both gradual change and stochastic events.

- Whilst the current extent of protected areas is greater than at any time in the past, there have been continuing calls for more and bigger protected areas (e.g. Lawton 2010), and for extending protected area coverage to ‘at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water and 10% of coastal and marine areas’ (Aichi Target 11); to 30% (EC 2020, Baillie 2018, Roberts 2020); and to 50% (Wilson 2016) of all land and sea.

- The extent in Scotland of all protected areas meeting the IUCN definition (IUCN NCUK 2012) was 22.7% (from our 2018 Aichi Target 11 Report) and 18% of the sea (NatureScot Board/178/14, 2019). With new marine protected areas we are on course to meet the EU’s targets in the emerging Biodiversity Strategy (EC 2020) for 30% of the sea under protection for nature but will have some ground to make up to reach this figure for terrestrial protected areas.

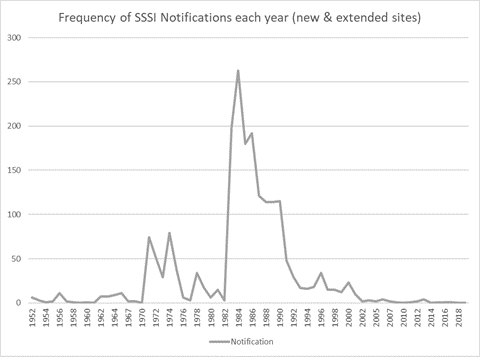

- Increasing the extent of protected areas is not without its challenges - statutory designation programmes demand high resource commitments for their establishment and subsequent management. (There have been relatively few terrestrial designations in the 21st Century. Appendix 1, Fig 4 shows the trend in SSSI designation).

- There are however a range of potential alternative approaches. For instance, there is growing interest in the use of Other Effective area-based Conservation measures (OECM) – a concept accepted by the IUCN (Dudley 2013, IUCN-WCPA 2019). These include private protected areas (PPA) and community conserved areas (CCA) which are areas of land managed for nature without statutory designation but under policy or contractual arrangements, or by individuals or groups. ‘Ground-up’ approaches like PPA & CCA offer people more opportunity to connect and engage more deeply with, and take direct responsibility for nature and its management. Management measures are still in development for many Nature Conservation Marine Protected Areas (NCMPA) in relation to fishing but legislation and other management mechanisms are in place to control development, including aquaculture and renewables. OECM have been collated for NCMPA (Marine Scotland 2018) but not for terrestrial protected areas (which are far more varied and complex).

Better managed protected areas

- Protected areas are, in general, better managed for nature and in better condition than other, non-protected, areas. However, we focus protection and management on specific features with little or no account taken of other habitats or species populations which function alongside, or are part of the same ecosystem, as the protected feature. A more holistic approach to conserving nature within protected areas boundaries could better support the resilience of nature within them and more widely, and provide more obvious use of protected areas in developing an ecological network.

- Our current management aims to achieve ‘favourable condition’ of protected features – and is the basis for measuring and reporting progress on a Scottish Government National Indicator. This measure is founded on maintaining features that were first notified as early as 1952, in a form of unending stasis – reflecting a time of greater (perceived) stability.

- The Protected Areas for Nature Review expert panel (Pepper 2014) expressed considerable doubt over the ability and wisdom of continuing to try and arrest seral change (for example from ‘open water’ to ‘marsh’ to ‘grassland’ to ‘scrub’ to ‘woodland’), and change attributable to changing climatic variables – and essentially ‘fighting against nature’. This concern persists and is gaining voice (Mezquida 2020). Climate change is likely to exacerbate current trends and bring new pressures. Addressing this issue will be challenging and complex and, under current legal provisions, failing to maintain a designated feature could increase the risk of legal challenge.

- In response to concerns around greater acceptance of change (i.e. losing some current protected features) and the increasing likelihood of unpreventable change, there may be an approach that recognises and prioritises sites and features by their rarity and irreplaceability. In the case of SSSI selection, features are selected (from Bainbridge 2013, s4.6) by

“the exemplary site principle” – adequate representation, in the form of the best examples, of countrywide variation in habitats and species – typically the more widespread and relatively common features; or

“the critical standard principle” – all examples above a defined quality – typically the rarer and less replaceable features

- An adaptive strategy might recognise these differences and apply different approaches – prioritising efforts to maintain the critical standard features as they are, but allowing more change on sites supporting exemplary features. A similar distinction is possible for geo-diversity sites. NatureScot could communicate the relevant approaches through SSSI Site Management Statements and/or SAC Conservation Advice Packages.

- Continuing to prioritise investment in the best protected and most secure features could also be considered to be failing to address the problem – that most biodiversity is outside of protected areas and the rate of loss from these areas is relatively high (e.g. Boatman 2015, Mora 2011). We may need to rethink how we measure the performance of protected areas and establish new measure(s) more reflective of a new forward- looking approach and needs.

Better connected protected areas

- There is a clear rationale for the general principle of better connecting nature – increasing meta-population sizes and providing increased scope for species movement through and/ or over relatively hostile intervening areas. The potential benefits to nature (and people) of developing an ecological network are widely recognised and it has been proposed many times, and was included in a Scottish Government National Planning Framework.

Delivering on the concept has met various challenges, including from within the environment sector. As a result, to date, effort and success in better-connecting terrestrial protected areas (or improving the connectivity of nature areas) has been limited. From a marine perspective however, NCMPA were selected such that they would form an ecologically connected network alongside existing European Sites and SSSI.

- For some protected area features, habitat networking may take too long to implement (e.g. for species requiring mature woodland) (NatureScot website). Such connectivity is often envisaged as continuous habitat but could also be achieved through development of habitat ‘corridors’ and ‘stepping stones’, and/or through changes in the type and intensity of management of the land, e.g. through greater ‘land-sharing’ (integrating intensive agricultural production and biodiversity conservation in larger, extensive landscapes).

- Protected areas have been cited as potential core areas or ‘hubs’ in the development of an ecological network (e.g. Lawton 2010). As current biodiversity hotspots, this is a potentially valuable role and fits with the early vision of SSSI as biogenetic refuges from which the wider countryside might, at a future time, be repopulated (NCC 1989).

- How such improved connectivity is achieved will vary between landscape types. Drawing on a submission to the Protected Areas for Nature Review, we might consider three landscapes and the most appropriate approach in each (recognising there will be overlaps).

- In urban and peri-urban landscapes with little space for nature – and relatively few and small protected areas – explore all opportunities to increase space for nature, e.g. green roofs and walls, wildlife gardening, wilder parks and wildlife corridors along linear infrastructure and waterways.

- In the uplands with more or less continuous semi-natural habitats and relatively large protected areas - build landscape-scale approaches that tackle, on a wide front, the main pressures on biodiversity and ecosystem services – deer management, stock grazing, controlled burning and wildfire, large-scale land conversion. Established examples include Cairngorms Connect, the Coigach - Assynt Living Landscape and The Great Trossachs Forest and Mar Lodge NNRs.

- In intensively managed lowlands and marginal hill ground where protected areas may be large or small, with boundaries drawn tightly around features and sharply defined by sudden transitions to unsupportive land management – seek opportunities to extend/ buffer protected areas and increase their connectivity by physically linking them or by creating corridors or stepping-stones between them. In short, build an ecological network. An example of this is the Central Scotland Green Network, a National Planning Framework initiative and the largest greenspace infrastructure project in Europe, aims to “connect green and blue spaces in towns and cities with the wider countryside and coast” and likely connecting many nature areas with new habitat.

- In the marine environment the importance of connectivity has been recognised, e.g.in the NCMPA selection guidelines. Connectivity is generally on much larger geographic scales than in the terrestrial environment with ongoing research and thinking looking at connectivity amongst and outside NCMPA (e.g. Gallego 2013, Millar 2019).

- Planning for a network based on protected areas should first consider the fundamental choice of achieving ecological functionality rather than focusing on existing protected features. Better connectivity may not mutually-support the features of nearby protected areas and provide a poor justification based on those features (e.g. there may be little or no benefit to features from investing resources to better connect a calcareous grassland with an open-water goose roost), but improved connectivity could provide multiple benefits for other species and the supply of ecosystem services.

Securing stored carbon and increasing carbon sequestration

- Our protected areas contain significant extents of carbon-rich soils, peatlands and marine sediments. Our management of these habitats aims to improve their condition and, in general, means it is well aligned with that required to improve their resilience as an adaptive management response to climate change (and other drivers of biodiversity loss), and increase their contribution to climate change mitigation.

- The following habitat groups offer the greatest potential for increasing carbon storage and sequestration. Note that the opportunities they offer are subject to varying risks (of re-release of carbon).

Peatlands

- The only known significant source of direct carbon emission from our protected areas is from degraded terrestrial peatland. Intact and ecologically functioning peatland is more likely to be sequestration-neutral (for CO2 and other greenhouse gases – often measured collectively as CO2 equivalent or CO2e) or may sequester up to 3t CO2e /ha (Birnie 2013, p13). Degraded peatlands are gross emitters at rates of around 2 to 5t CO2e/ha (Birnie 2013, Evans 2017). For comparison, drained and industrially extracted peatland may release nearly 14t CO2e/ha (Evans 2017).

- Our protected areas collectively contain an estimated 7,277 Million m3 of peat – almost 30% of all peat in Scotland (from GIS analysis of JHI Peat Depth Survey data). There is scope to improve the condition, and carbon sequestration ability, of a significant area of peatland within protected areas. Whilst the actual extent and scope for improvement is incalculable, with uncertainties including existing condition, accessibility and subsequent performance, analysis provided by Peatland Action (February 2020) indicates 155,000ha within SSSI alone. If this was restored to full functionality it could sequester up to 775,000t CO2e pa (based on eliminating emissions of 2t/ha, and sequestering 3t/ha).

- Given the extent of peatland and other peat soils and the potential for massive carbon release / sequestration, there is a strong incentive to prioritise peatland restoration both to keep carbon, sequestered over millennia, securely stored in the ground and increase its contribution to climate mitigation. NatureScot operates, and has benefited from, the ‘Peatland Action Fund’. This initiative to restore degraded peatlands is funded by the Scottish Government to meet one of its Climate Change Action Plan commitments and ambition to restore 250,000 hectares of peatland by 2030.

Woodlands

- Land supporting existing established woodland may offer little new sequestration potential, and within protected areas expansion of woodland may conflict with the conservation of other habitats. However, within our protected areas, and especially the larger upland sites selected on a ‘whole topographic unit’ basis, there is scope for diversification and establishment of high-carbon habitats, such as native woodland, on the lower slopes. We are expanding native woodland in such manner on lands we manage at Creag Meagaidh, Beinn Eighe and Craigellachie, and planning for expansion at Cairnsmore of Fleet.

- Increasing woodland cover, and prioritising towards old growth, would help secure long-term retention of carbon and support a nature rich future. Use of natural regeneration avoids many of the initial carbon-costs of commercial afforestation methods – requiring minimal or no ground preparation, very little transport of materials and, in some cases, no fencing materials. A large proportion of carbon captured in a commercial conifer crop is released at, or shortly after, felling. Naturally-regenerating woodland without fences begins to sequester carbon from day 1 and, as it is typically established with longer-term objectives, keeps sequestered carbon stored for longer.

Coastlands

- Saltmarsh and mudflats are valuable for sequestering and storing carbon. The carbon stored in these soft deposits may also be re-released through coastal erosion, a risk that may increase with climate change and rising sea-levels and increased storminess. There is limited practical (and acceptable) scope for increasing their extent within protected areas. Creation of habitat on adjacent land through managed shoreline retreat could be an option on some sites.

Marine habitats

- Through the Blue Carbon Forum we work with Marine Scotland and other partners to improve understanding of carbon storage, sequestration and management in marine habitats. Work is underway to understand the implications of human-activity induced carbon release, for example from trawling over marine burrowed muds, which will inform future policy and management decisions (e.g. Turrell 2020).

Reducing operational emissions

- Active management, monitoring and use of protected areas generates emissions from protected areas managers, including NatureScot, and by visitors.

Protected areas management emissions

- Management of terrestrial protected areas by their private, other public body or eNGO landowners/managers generates greenhouse gas emissions. Potentially significant sources of emission from the management of protected areas include -

- muirburn - but for well managed and recovered burns the evidence on related emissions is inconclusive (Chapman et al 2017);

- aerial herbicide treatment (bracken spraying)

- livestock grazing – though such grazing may be integral to maintaining favourable condition of the protected area features;

- goose management scheme fertiliser applications - schemes fund the application of up to 1,552.5t of artificial NPK (its manufacture and transport are energy intensive); and

- monitoring activities such as helicopter-borne deer counts.

- Other than for the protected areas we manage directly, our influence over land managers’ emission-related choices is through advice or incentive (directly through management agreements or indirectly through Scottish Government support for land management).

- Through post-Brexit reforms of agricultural payment schemes there could be opportunities to further consider incentives or approaches to support emissions reductions in land-management activities.

- NatureScot is actively exploring the potential of new technologies in Earth observation, environmental DNA sampling, and alternatives to helicopter surveys of large grazing animals.

Visitor emissions

- We encourage people to visit protected areas we manage (as nature reserves) and due to their location, the vast majority use private cars for transport. We are separately looking at diverse options to encourage virtual-visiting, active and low-C travel, and support staycation options.

Challenges to implementation

- Our approach to protected areas has not changed significantly since it was developed in the mid-20th Century and is therefore not necessarily ideally suited to address the current global drivers of biodiversity loss, including climate change, and which have no respect for boundaries. Some of the challenges, and opportunities are for how we best use our protected areas resource in tackling climate change are considered below.

Protected area legislation and associated guidelines and policy

- Our legislation now provides NatureScot and other authorities with strong measures to deter illegal damage and (in certain circumstances) require restoration of damage that does occur. With this strengthening has also come a focus on specifically defined features and human activities - a trend most apparent in the SSSI legislations of 1949, 1981 and 2004. Affording higher priority to non-feature nature or broader ‘ecosystem health’ improvements within protected areas may be compatible with the current legislation, but would require substantial rethinking of current policies and priorities (and resources) for protected areas management and our (casework) responses to development and management proposals.

- Current guidelines do not provide for the selection of protected areas based on ecosystem services other than nature conservation. It may be a small and relatively achievable step to extend the guidelines to include selection of, for example, carbon-rich habitats for their role in storing and/or sequestering carbon – as recognised in the EU Biodiversity Strategy and its 30% protected areas target (EC 2020).

- For some wide-ranging detrimental pressures, such as elements of climate change, atmospheric pollution, nitrogen deposition and acidification, the protected areas approach alone is an inadequate response. A change in approach to using protected areas more holistically to support biodiversity conservation would help build the resilience of wider nature, and may be achievable with a small change in policy.

- The UK approach to protected area boundaries has been to draw them tightly around selected features. With few exceptions there is little ‘spare’ room within protected areas for climate beneficial land-use changes that would not impact protected features. To achieve aspirations for bigger and better connected protected areas (and features) protected areas managers will likely need to look for opportunities in the wider landscape – and work with new stakeholders and partners. Protected areas managers need to be trained, resourced and empowered to pursue such opportunities.

- The emerging new EU Biodiversity Strategy sets out aspirations not only for increased coverage of protected areas but also strict protection for some habitats such as ancient woodlands and peatlands. This could form the basis of a new policy direction for Scotland, and provide a strong direction for extending protected areas or applying new approaches and thinking such as OECM.

Adaptive management

- Protected areas managers, supported by the relevant authorities and associated management incentives, should be required to specifically consider and address the likely impacts of climate change in management plans (or equivalents). Relevant support materials have now been produced and are freely available (e.g. Gross 2016, Natural England 2019, Mezquida 2020).

- We will need an adaptive approach to site management as climate change progresses. It is unlikely we will have the resources to maintain all of our protected features where they are and in the condition they are (as if in stasis). Indeed, many important but unseen aspects of our protected areas (e.g. mycorrhizal and invertebrate communities) may change irrespective of our success in maintaining the macro features.

- There were good reasons (e.g. clarity in law, resource management) for adopting a feature based approach to protected areas but it may now be limiting the scope of ambition and flexibility in how we use them as a mechanism to influence wider change and benefit. An alternative and more holistic approach focused on ecosystem functioning and health, remembering that protected areas are typically good places for a wide range of species, could greatly increase our protected areas contribution to biodiversity conservation and build nature’s resilience to climate change.

- This may pose challenging choices, for example, whether to allow the development of a higher-carbon storing habitat over a lower carbon one, either or both being protected area features. It is not an entirely new conundrum – we face it when trying to achieve favourable conservation of features on the same site that require different and conflicting management regimes e.g. heavier or lighter grazing; but climate change and other pressures may exacerbate the challenge for site managers. As above, we may require a more adaptive approach to management.

- Together with a more adaptive approach to management, we will require more than just a single measure of the performance/effectiveness of protected areas management and its implication for biodiversity and ecological health of these areas.

More and bigger protected areas

- Increasing the coverage of protected areas, whether by designating more areas, enlarging existing ones or a combination of both is likely to be extremely challenging, expensive and contentious.

- From a legal perspective, the current framework could potentially facilitate designation of new sites but enlarging existing protected areas could be more problematic. The legislation currently focusses on evidence of special protected features and to facilitate a more holistic approach to improving resilience and reflecting dynamic change might require revisions to existing selection guidelines or the underpinning legislation. This could potentially mean considering the designation of sites for potential value rather than existing value. Any revised approach would also need to consider the impacts of potential loss or de-designation of sites as climate change results in the loss of protected features.

- There are a range of approaches that could secure greater protected area coverage. Further guidance from the EC in terms of reaching the ‘thirty by thirty’ target as part of the EU Biodiversity strategy 2030 should be forthcoming later this year and should help clarify potential approaches in this respect.

- Securing the management of additional land and sea could be achieved by alternative approaches or OECM (para 28). For this, NatureScot could use its options to purchase, lease or enter an agreement over land. Government land-use support schemes could potentially be adapted/ re-prioritised to support OECM areas.

- In the marine environment, in accord with National Marine Plan policies, priority marine features (PMF) outside of MPAs are protected from significant impacts on their ‘national’ status and work to expand this level of protection through the use of fisheries management measures (OECM) is ongoing.

Stakeholders

- Achieving sufficient response in land-use change to significantly support climate mitigation and adaptation will require radical changes in the perception of protected areas, and much wider support across the land management community. In developing a new approach, protected areas provide significant opportunities to engage with land-managers and communities across the country, and to build new relationships and encourage and support change.

- Land managers, like nature conservationists, are facing an, as yet, poorly defined challenge to their established ways of working. As we use many of the same practices, at differing levels of intensity, we might learn more and faster through greater communication and sharing with protected area land managers. For example, we could provide easier access to relevant information, offer demonstrations and share experience.

- Ultimately, the actions we consider necessary will require significant public and land-manager support to help secure adequate resources. Remembering that for most people ‘environment is a local matter’ – the presence of a protected area within a short walk (or sail) of most people, makes our protected areas network a far-reaching, diverse and under-utilised resource for connecting people and nature where they are.

- There is a need for a more strategic approach to improve engagement and understanding of the importance and value of protected areas. The increasing relevance of the role of protected areas in climate mitigation and adaptation and addressing biodiversity loss needs to be better articulated. Approaches such as Natural capital assessments and nature-based solutions may help in this messaging.

Competition for land

- Our current approach originated during and to address a post-war ‘land-grab’ at the start of a period of significant intensification of land-use for agriculture and forestry. We may now be experiencing renewed pressure for land and seabed use to meet the new demands of a carbon zero economy. New demands for land for biofuel crops and solar arrays, wind, hydro and tidal-flow turbines and associated infrastructure, could drive upwards the value of the currently less economically productive land, which includes many of our protected areas. This could push options for securing more land for more, bigger and better connected nature areas, beyond our budgets.

Unforeseen consequences

- Climate change is only one driver of change to nature and protected areas are only one part of nature. In designing and implementing new approaches in relation to protected areas we need to ensure that we recognise the complexity of these interactions and understand them better. We need to be mindful of the potential implications of our actions in addressing one driver and the risks in relation to others. An example might be the potential risks of increasing connectivity in terms of the spread of INNS and new pests and pathogens.

Conclusion

- Our protected areas are vital for nature and emphasis on their importance to both the biodiversity and climate crises is increasing. Climate change is and will continue to put pressure on our protected areas. We need to consider the relevance of current measures to consider their health and value and whether they are appropriate and sufficiently dynamic and holistic. We also need to ensure that management of these sites can make them sufficiently resilient to climate change. This means being adaptive and the consideration of land and land-management beyond site boundaries.

- The current suite of protected areas cover some of our most biodiverse habitats and those of the greatest value in terms of sequestering and storing carbon, but they do not protect all such habitats nor do they reflect areas or habitats with the greatest potential in this respect.

- We need to recognise that climate change will result in winners and losers within and between sites in terms of the nature they hold. We will need to make difficult decisions as to desired outcomes, but with a more holistic viewpoint and in consideration of ecosystem health and natural capital. Carefully balancing one protected feature against another and ‘gardening’ to maintain such balances may offer little value.

- Increasing emphasis on the importance of protected areas, and delivering more, bigger, better managed and better connected protected areas presents multiple challenges but also multiple benefits. However we have to be mindful that protected areas are not a panacea nor is climate change the only driver. Protected areas are part of the solution to a nature-rich future but we have to be consider their role in the wider countryside and the other drivers of biodiversity loss.

- Climate change means change, but our approach to protected areas is rigid. The framework and rationale behind protected areas as we know and use them, particularly from a terrestrial perspective, is arguably not fit-for-purpose and outdated. Marine protected areas, having their roots in more contemporary thinking, have been developed and are being implemented with conscious consideration of climate change, ecosystem services and ecological connectivity.

- For terrestrial protected areas however, the need to ‘update’ our approach to better address the current drivers of biodiversity loss, including climate change, has been recognised and the subject of reviews, both here and elsewhere. We are dealing with embedded and complex arrangements and no obviously easy and risk-free route towards a new approach has yet been described. Meanwhile, our options and time to act and have meaningful effect are reducing as climate change continues apace.

Appendix 1 Notes on Protected areas data and policy

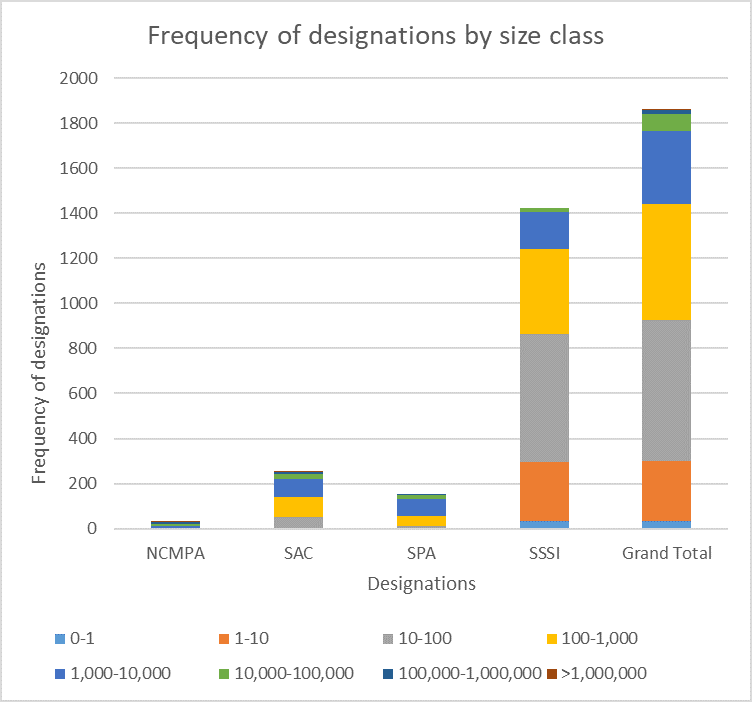

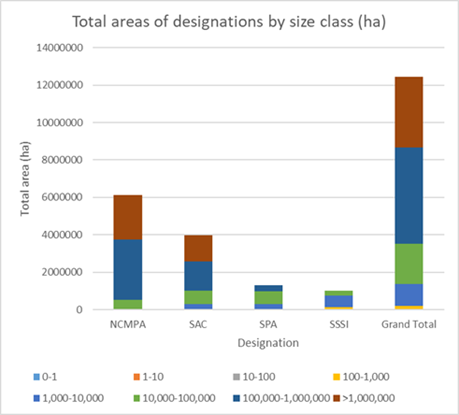

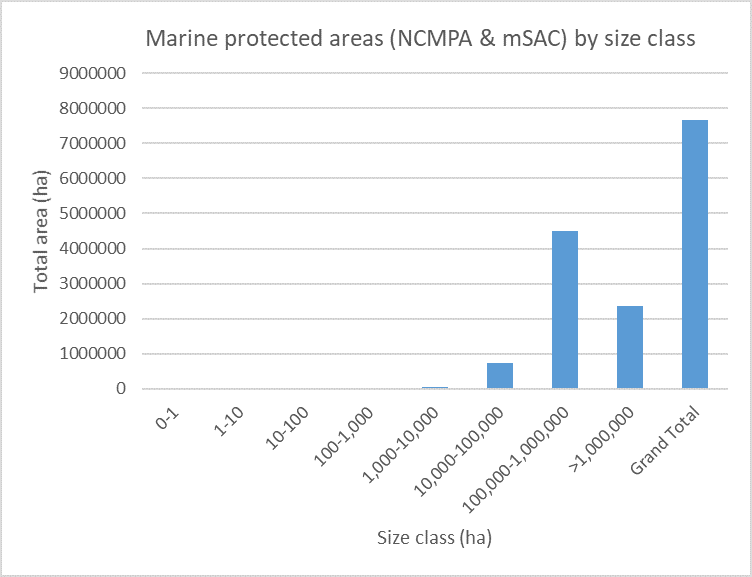

- Our system of regulatory protected areas currently comprises around 1,860 SSSI, SAC, SPA, NCMPA extending to (nett) more than 1,387,000 ha of land (above MHWS)(17.6%) and more than 10,879,000 ha of intertidal and marine (17.6%). If currently planned marine protected areas proceed the extent of protected areas in the marine environment will rise to 30%.

- A relatively small number of NCMPA and marine SAC makes a disproportionately large contribution to the total area. Conversely, a much larger number of smaller terrestrial protected areas makes a disproportionately small contribution to the total area.

- Protected areas are defined in law to protect specified features within geographically defined areas. The selection and definition of all these protected areas is based on the occurrence of special interests at, or prior to, that time.

- The selection, designation and subsequent management of protected areas involves primarily NatureScot and the respective landowners and managers or, in the case of marine sites, significant user groups. With the exception of those we manage directly, there is little engagement with the wider community.

- The majority of terrestrial protected areas are parts of private working farms and estates. Nature conservation aspirations may be supported and/or compromised by other land-use objectives.

Relevant legislation, policy and commitments

- Designations over the last 20 years of new European sites and NCMPA has been driven by the needs of relevant legislation (see Dorin 2020) and policy. For SSSI only, the legislation provides for NatureScot to vary boundaries and features and the scope of protection. Scottish Ministers legally designate NCMPA and European Sites. Protected areas policy is set by Scottish and UK Governments for European sites and NCMPA, and by NatureScot for SSSI. Three policies specifically and directly involve NatureScot -

- Develop a new approach to protected areas (a NatureScot key deliverable).

- Improve the condition of protected nature sites (a Scotland Performs National Indicator).

- Carbon net-zero by 2045 (NatureScot commitment to Scottish Government).

Figures 1 to 3 give an indication of each protected area designation’s contribution to the protected areas system by frequency and total area.

SSSI policy

- NatureScot SSSI policy (2010) refers to climate change and provides for flexibility in our use of the SSSI series - which could be used to adapt the series to reflect observed climate change effects (but not in anticipation of such effects). It states that

“SNH will keep the details and boundaries of sites under review and take such actions as it deems necessary. This will help maintain the credibility of the series, and ensure that it continues to meet its statutory and functional purposes.”

- In relation to climate change it states that

“As we face up to climate change and other environmental challenges, working ecosystems are the greatest inheritance we can leave for our children. We must use them wisely and within their capacity to replenish themselves – for they are easily lost and very much harder and costly to restore, if indeed that is possible. Our SSSIs are at the heart of these ecosystems, providing a stock of near-natural environments where the complex interactions of nature are maintained.”

- Since 2010 we have designated only one wholly new SSSI (5ha) and extended three (537ha). Figure 4 shows the counts of new land being notified as SSSI in each year from 1952 to 2019.

NCMPA policy

- NCMPA are designated under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 which specifically mentions climate change adaptation and mitigation – and in 2010 was the only UK marine conservation legislation to do so (Frost 2016). It places a duty on Ministers and public authorities when exercising their duties in relation to the Scottish marine area, to protect and enhance the marine environment. Additionally, it provides that Scottish Ministers may, when considering designation of an NCMPA, have regard to the extent to which doing so will contribute to the mitigation of climate change. The National Marine Plan also sets out relevant climate change policies.

References

Alonso I, Weston K, Gregg R & Morecroft M. (2012) Carbon storage by habitat - Review of the evidence of the impacts of management decisions and condition on carbon stores and sources. Natural England Research Reports, NERR043.

Baillie J, Zhang Y-P. (2018) Space for nature. Science 361, 1051.

Bainbridge I, Brown A, Burnett N, Corbett P, Cork C, Ferris R, Howe M, Maddock A, Mountford E, Pritchard S (Editors). (2013) Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs Part 1: Rationale, Operational Approach and Criteria for Site Selection. JNCC.

Birnie RV and Smyth MA (2013) Case Study on developing the market for carbon storage and sequestration by peatlands. NE0136 Technical Annex. Crichton Carbon Centre.

Boatman ND, Parry, HR, Bishop DJ, Cuthbertson AGS (2015). Impacts of Agricultural Change on Farmland Biodiversity in the UK. In Hester RE, and Harrison RM (eds), Biodiversity under threat, RSC Publishing, Cambridge. 1-32.

Brooker R, Castellazzi M, Gimona A, Poggio L, Ahrends, A, Ellis A, Bond C, Harding A, Kirkbride V, Wignall R & Rowan J. (2014) Summary Report: Climate Change Risk-Based Assessment for Notifiable Features in Scotland. Climate Xchange

Burrows MT, Hughes DJ, Austin WEN, Smeaton C, Hicks N, Howe JA, Allen C, Taylor P & Vare LL. (2017) Assessment of Blue Carbon Resources in Scotland’s Inshore Marine Protected Area Network. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 957.

Cantarello E, Newton AC & Hill R. (2011) Potential effects of future land use change on regional carbon stocks in the UK. Environmental Science & Policy, 14(1), pp.40–52. in EcoServ-GIS v3.3 Technical Report: “Carbon Storage Service”

Chapman S, Hester A, Irvine J, Pakeman R. (2017) Muirburn, Peatland and Peat Soils – An evidence assessment of impact. ClimateXchange/ The James Hutton Institute.

Crofts R, Dudley N, Mahon C, Partington R, Phillips A, Pritchard S, Stolton S (2014) Putting Nature on the Map: Summary of a Report and Recommendations on the Use of the IUCN System of Protected Area Categorisation in the United Kingdom: IUCN National Committee UK.

Dudley N, Shadie P, Stolton S (editor) (2013) Guidelines for applying protected area management categories including IUCN WCPA best practice guidance on recognising protected areas and assigning management categories and governance types. IUCN.

Dorin A (2020) Types of Protected Area. Protected Areas Committee: Information Paper (unpublished). Scottish Natural Heritage. A3127857

EC/ European Commission (2020) EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 - Bringing nature back into our lives. Communication from the Commission to The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee & The Committee of the Regions.

Evans C, Artz, R, Moxley J, Smyth M-A, Taylor E, Archer N, Burden A, Williamson J, Donnelly D, Thomson A, Buys G, Malcolm H, Wilson D & Renou-Wilson F. (2017) Implementation of an emission inventory for UK peatlands. Report to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

Field RH, Buchanan GM, Hughes A, Smith P, Bradbury RB (2020) The value of habitats of conservation importance to climate change mitigation in the UK. BIOL CONS 248

Frost TM, Bayliss-Brown G, Buckley P, Cox M, Dye SR, Sanderson WG, Stoker B and Harvey NW. (2016) A review of climate change and the implementation of marine biodiversity legislation in the United Kingdom. Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 26: 576–595.

Gallego A, Gibb, FM, Tulett, D, Wright PJ. (2013). Connectivity of benthic priority marine species within the Scottish MPA network. Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 4 No 2. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Gross JE, Woodley S, Welling LA & Watson JEM (Editors). (2016) Adapting to Climate Change: Guidance for protected area managers and planners. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 24, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

IPBES (2019): Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

IUCN NCUK (2012) Putting Nature on the Map - identifying protected areas in the UK: A handbook to help identify protected areas in the UK and assign the IUCN management categories and governance types to them, IUCN National Committee for the United Kingdom.

IUCN-WCPA Task Force on OECMs (2019) Recognising and reporting other effective area-based conservation measures. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

Lawton JH, Brotherton PNM, Brown VK, Elphick C, Fitter AH, Forshaw J, Haddow, RW, Hilborne S, Leafe RN, Mace GM, Southgate MP, Sutherland WJ, Tew TE, Varley J, & Wynne GR. (2010) Making Space for Nature: a review of England’s wildlife sites and ecological network. Report to Defra.

Marine Scotland (2018) Marine Protected Area Network - 2018 Report to the Scottish Parliament. Annex 3: Other area based measures

Millar, H., O’Hara Murray, R., Gallego, A., Gormley, K. & Kent, F. 2019. Connectivity of selected Priority Marine Features within and outwith the Scottish MPA network. Scottish Natural Heritage Research Report No. 1048.

MCCIP / Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership (2013) How can marine protected areas and networks help address climate change?

MCCIP Report Cards (2020) MCCIP website

Mezquida JAA, Santos MM & Múgica de la Guerra M. (2020) Protected Areas in the Face of Global Change. Climate Change Adaptation in Planning and Management. EUROPARC-Spain.

Mora C & Sale P. (2011) Ongoing global biodiversity loss and the need to move beyond protected areas: A review of the technical and practical shortcomings of protected areas on land and sea. Marine Ecology-Progress Series. 434. 251-266.

Natural England & RSPB. (2019) Climate Change Adaptation Manual - Evidence to support nature conservation in a changing climate, 2nd Edition. Natural England.

NCC (1989) Guidelines for selection of biological SSSIs. Nature Conservancy Council, Peterborough.

Roberts CM, O’Leary BC, Hawkins JP. (2020) Climate change mitigation and nature conservation both require higher protected area targets. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375: 20190121.

Pepper S, Benton T, Park K, Selman P, Thomson J and Trench H. (2014) Protected areas for nature – review. Report to Scottish Natural Heritage

Rivington M, Spencer M, Gimona A, Artz R, Wardell-Johnson D and Ball J. (2019) Snow Cover and Climate Change in the Cairngorms National Park: Summary Assessment. James Hutton Institute.

Scottish Government (2015) Scotland’s National Marine Plan. A Single Framework for Managing Our Seas.

Smeaton C, Austin W & Turrell WR. (2020) Re-Evaluating Scotland's Sedimentary Carbon Stocks. Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 11 No 2.

Turrell WR. (2020) A Compendium of Marine Related Carbon Stores, Sequestrations and Emissions. Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 11 No 1.

Wilson EO. (2016) Half-Earth. Our Planet’s Fight for Life. Liveright / W.W. Norton.