NatureScot Research Report 1271 - Case studies in Large Scale Nature Restoration and Rewilding

Year of publication: 2022

Authors: Underwood, S., Kaczor, K., Roberts, V., Tooze, G., Rayment, M., Smith, M., Fry, C., Swindlehurst, S., Armstrong, S. and James, N. (LUC in association with ABPMer, Accelar and Rayment Consulting Ltd.)

Cite as: Underwood, S., Kaczor, K., Roberts, V., Tooze, G., Rayment, M., Smith, M., Fry, C., Swindlehurst, S., Armstrong, S. and James, N. 2022. Mainstreaming Large Scale Nature Restoration. NatureScot Research Report No.1271.

Keywords

biodiversity; climate change; green finance; land use; nature; rewilding; socio-economic

Background

The research explores barriers and opportunities to large-scale nature restoration projects (LSNR) and rewilding through case studies. Within the literature a range of terminology is used to describe nature restoration at the landscape scale, however the projects included in the study include a broad spectrum of approaches and project scales, which may not be all recognised as ‘rewilding’. The approach involved the evaluation of 25 case studies, ten of which were explored in greater detail and were informed by one-to-one interviews. The research included analysis of how LSNR / rewilding can be financed using a variety of different financing mechanisms. The research also sought to identify the potential socio-economic impacts of projects, however it needs to be noted that the evidence base is incomplete, and the data is mostly qualitative.

Main findings

Project aims, objectives & timescales

- LSNR / rewilding projects have varied principal aims and objectives, including restoring habitats and natural processes, enhancing carbon sequestration and storage, and moving to models of land management which are environmentally and economically sustainable.

- All case study projects had broader aims and objectives which reflect the multi-benefit character of nature restoration projects covering social and economic as well as environmental objectives.

- Most projects are driven by a focus on restoring natural processes or habitats that are being lost. Several projects focus on aspects of climate mitigation including peatland restoration or woodland creation and regeneration. A number of projects aim to increase the diversity and resilience of ecosystems to climate and other changes.

Project benefits

- LSNR / rewilding projects potentially have a range of economic impacts, directly and indirectly, positive and negative. Overall, most of the case studies do not have quantitative data to enable assessment of overall net effects on employment/income on the land affected or in the wider economy compared with the baseline. These data do not appear to be routinely captured.

- Social benefits are identified in relation to employment, volunteering, recreation, education and engagement, with mental health benefits from employment and flood risk reduction.

- Learning from other projects nationally and internationally is beneficial for project management and development, and knowledge sharing needs to be supported.

Issues and barriers

- A persistent barrier to effective implementation is that of translating a vision into a functional delivery framework that is underpinned by sufficient staff and funding.

- Engagement with local stakeholders is important to overcome areas of potential conflict or perceptions of impacts of land management change on surrounding areas. This needs to be supported by ongoing engagement.

- Funding related barriers include lack of alignment of project aims with existing funding schemes and short-term funding cycles being out of step with the long-term project aims.

- Project funders vary significantly in their administration and reporting requirements and although some appear burdensome, most of the detailed case studies did not suggest it had been a barrier to project delivery. It can often be difficult to capture changes at the scale at which LSNR / rewilding projects operate because monitoring data is typically spatially discrete, although some projects have involved academics in monitoring and evaluation of benefits.

- Upland LSNR typically face fewer barriers, however deer management is an issue for the Scottish Highlands, particularly where projects focus on woodland expansion, but also in relation to peatland restoration.

Delivery mechanisms

- The most straightforward pattern of project implementation appears to be for owner-occupied estates which, subject to the influence of regulators, are under the control of a single owner.

- Partnership working tends to be beneficial to project delivery, however this requires significant time inputs to influence landowners to bring about land management change.

Fitting LSNR / rewilding with the wider environmental policy context

- In lowland agricultural LSNR projects, the role of agri-environment funding is significant in the delivery of the projects which reduce the area of productive agricultural land.

- Coastal realignment projects can include significant engineering work to reflect the dynamic coastal edge and management of natural processes. The disruptive nature of significant engineering work may require additional mitigation for protected species impacted by the works.

- Green finance is evolving, both for wider environmental outcomes and specifically within nature restoration. One of the main challenges with ecological financial markets is that they are not yet widely understood in terms of the benefits they deliver and the investment vehicles that are required to support them.

- The report includes a set of recommendations for further work on the potential of LSNR / rewilding.

Acronyms

|

AES |

Agri-Environmental Scheme |

|

AONB |

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty |

|

ATN |

Associação Transumância e Natureza |

|

BNG |

Biodiversity Net Gain |

|

CAP |

Common Agricultural Policy |

|

CS |

Countryside Stewardship |

|

CSGN |

Central Scotland Green Network |

|

DofE |

Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme |

|

EA |

Environment Agency |

|

ELM |

Environmental Land Management |

|

ELP |

Endangered Landscapes Programme |

|

ERDF |

European Regional Development Fund |

|

ES |

Environmental Stewardship |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

FBT |

Farm Business Tenancy |

|

FCS |

Favourable Conservation status |

|

FTE |

Full Time Equivalent |

|

GES |

Good Ecological status |

|

HOWL |

Highland Outdoor and Wilderness Learning |

|

ICM |

International Commission on Management of the Oostvaardersplassen |

|

IDB |

Internal Drainage Board |

|

LCA |

Landscape Character Area |

|

LNP |

Local Nature Partnership |

|

LSNR |

Large-scale Nature Restoration |

|

NCA |

National Character Area |

|

NE |

Natural England |

|

NFM |

Natural Flood Management |

|

NIA |

Nature Improvement Area/s |

|

NLCA |

National Landscape Characteristic Area |

|

NNR |

National Nature Reserve |

|

NPF4 |

Fourth National Planning Framework |

|

NUC |

Northern Upland Chain |

|

MWT |

Montgomery Wildlife Trust |

|

PES |

Payments for Ecosystem Services |

|

PROW |

Public Rights of Way |

|

RLUP |

Regional Land Use Plans |

|

RTE |

Regulated tidal exchange |

|

SAC |

Special Area of Conservation |

|

SCI |

Site of Community Interest |

|

SEPA |

Scottish Environment Protection Agency |

|

SNH |

Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) |

|

SPA |

Special Protection Area |

|

SRDP |

Scotland Rural Development Programme |

|

SSSI |

Site of Special Scientific Interest |

|

SWFBI |

South West Farmland Bird Initiative |

|

TEK |

Traditional Ecological Knowledge |

|

TENT |

The European Nature Trust |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UXO |

Unexploded ordnance |

|

WWNP |

Working with natural processes |

|

WWT |

Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust |

Acknowledgements

The project team would like to express their gratitude to the individuals who generously gave their time to provide information for interviews undertaken for the case studies and green finance elements of this research.

Introduction

LUC in association with ABPmer, Accelar, and Rayment Consulting Ltd were commissioned by NatureScot in September 2020 to review large-scale nature restoration (LSNR) and rewilding case studies.

The report sets out the findings from 15 high level and ten more detailed case studies. This includes an analysis of key opportunities and barriers from existing projects. This is followed by a discussion of approaches that could help mainstream LSNR and rewilding projects, including green finance models.

Project context

Within Scotland, the key policy context for the study includes the climate emergency and biodiversity crisis, both of which were declared by the First Minister of Scotland in May 2019. The Scottish Government has set ambitious targets for achieving net zero emissions to address the climate emergency, supported within the Climate Change Plan Update (2020), which sets out key ambitions to increase woodland creation to 18,000 hectares a year in 2024/25 and increase levels of peatland restoration (Scottish Government, 2020). Likewise, there are national, EU and global targets to address the biodiversity crisis, including the Scottish Biodiversity Statement of Intent (published December 2020) (Scottish Government, 2020), EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (European Commission, 2020) and the updated post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2020).

At an international level, UN Member States are implementing a Decade on Ecosystem Restoration to realise the benefits of ecosystem restoration to increase social, economic and ecological resilience and to ensure that healthy ecosystems play a critical role towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration is running from 2021 – 2030, aligning with the deadline for the Sustainable Development Goals and the timeline for the last chance to prevent catastrophic climate change.

Definitions

This study has used the terminology LSNR (Large-Scale Nature Restoration) to reflect the aims and scope of the study. Within the literature a range of other terminology is used, principally ‘rewilding’, and further discussion on definitions is provided in Context for Large Scale Nature Restoration / Rewilding section.

Project aims

The aims of the project are as follows:

Draw lessons from a selection of existing LSNR / rewilding projects in the UK and the rest of Europe on approaches to the development of LSNR / rewilding.

- Identify the opportunities, incentives and obstacles to LSNR / rewilding projects in Scotland.

- Explore how LSNR could be rolled out under future agricultural and land use policy– and approaches to blend public and private finance for LSNR / rewilding projects.

- Outline how these projects could be delivered, considering potential socio-economic impacts.

Structure of the report

The structure of this report is as follows:

- Methodology

- Project context

- Study findings

- Green Finance

- Recommendations

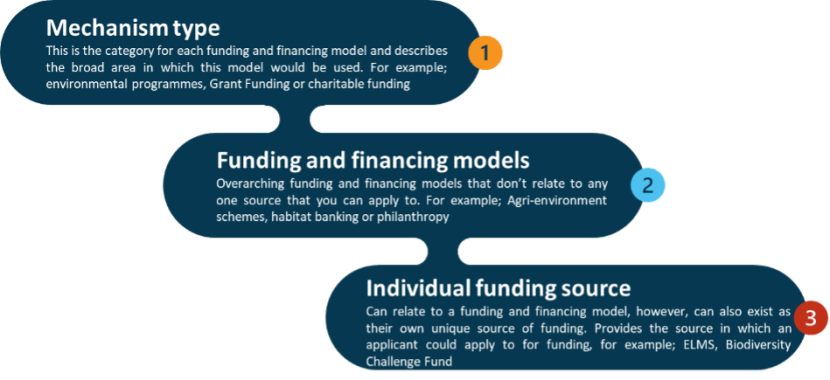

The ten detailed case studies and 15 high level case studies are included as Annex 1 - Detailed Case Studies and Annex 2 - High Level Case Studies of this report respectively. Annex 3 - Long list of funding models includes the long list of funding models (which is supported by a separate Excel spreadsheet). Annex 4 - Short-Listed Profiles Chosen for Further Research includes short-listed profiles chosen for further research. Annex 5 - Green Finance Stakeholder Interview Discussion Points provides an overview of the finance interview structure. Annex 6 - Case Studies Interview format provides an overview of the structure for the ten detailed case study interviews.

Methodology

This section of the report describes the approach to the research. It sets out the approach to identifying and selecting the case studies, summarises the key characteristics of the case studies and the approach to data collection and analysis.

Identifying and selecting the case studies

The first stage in identifying potential case studies was based on a review of information from previous Large Scale Nature Restoration (LSNR) and rewilding projects, internet searches (including the Rewilding Europe website) and suggestions from the project team and steering group based on existing knowledge. The long list of case studies was then collated in a table which recorded summary information available for each case study.

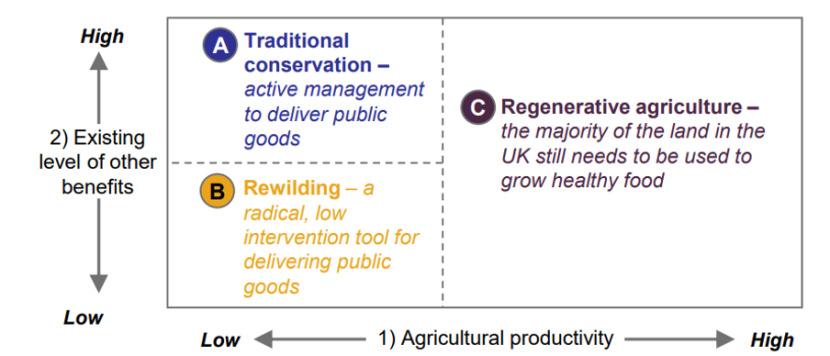

Project scale was discussed at the project inception meeting in order to identify parameters for identifying the case studies. Different scales were identified for lowland and upland projects. The scale for lowland projects was initially set as over or around 1,000 hectares (ha) and the scale for upland projects set as over 10,000 ha. However, it was recognised that flexibility was required within these parameters. The review of the case studies in the lowland context identified that these projects were typically below 1,000 ha. The spectrum of projects to be included was also agreed to include both more ‘natural’ projects and those including a higher proportion of land managed for agriculture, based on project specifications and early discussions with NatureScot.

This process led to the creation of a ‘long list’ of candidate LSNR and rewilding projects, all at different points along a continuum in terms of delivery stage and ambitions. The term ‘large-scale nature restoration (LSNR) was used to reflect the fact that not all of the projects reviewed could be characterised as ‘rewilding’ (see Guiding principles for rewilding section).

Summary information on the project scale, location and type was gathered for just over 70 projects. An initial review including the availability of information on the candidate project and feedback from the project steering group was used to identify 15 high-level case studies and ten detailed case studies. The projects were selected to ensure they covered a range of geographic locations, habitat types, project types and scales and a variety of organisations/partnership approaches (public sector, private sector, NGOs, protected landscapes). No suitable community-led project was identified.

The characteristics of the selected case studies are summarised in Table 2.1 below.

| - | Location | Land type | Project type | Project area (ha) approx. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alladale Estate |

Sutherland, Scotland |

Upland |

Rewilding*, peatland and woodland restoration, species reintroduction |

9,000 |

|

Balcaskie Estate |

Fife, Scotland |

Lowland |

Sustainable farming, agroecology |

1,800 |

|

Bunloit |

Inverness-shire, Scotland |

Upland |

Sustainable land management for climate change and biodiversity, rewilding* |

500 |

|

Glen Affric |

Inverness-shire, Scotland |

Upland |

Woodland restoration |

14,500 |

|

Glen Tanar |

Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

Upland |

Sustainable land management |

10,000 |

|

Great Fen |

Huntingdon, England |

Lowland |

Wetland restoration |

3,000 |

|

Great Trossachs Forest |

Trossachs, Scotland |

Upland |

Woodland restoration |

4,400 |

|

Knepp Castle Estate |

West Sussex, England |

Lowland |

Rewilding*, sustainable land management |

1,416 |

|

Steart |

Somerset, England |

Coastal |

Coastal management with nature-based solutions |

400 |

|

Sunart Oakwoods |

Argyll, Scotland |

Upland |

Woodland restoration |

10,000 |

|

Temple Farm |

Wiltshire, England |

Lowland |

Nature-friendly farming, agri-environment and sustainable land management |

800 |

|

Thorneythwaite Farm |

Cumbria, England |

Upland |

Sustainable land management |

122 |

|

Greater Coa Valley |

Portugal |

Upland |

Rewilding*, species reintroduction, habitat creation and management of fire risk |

100, 000 |

|

Central Apennines |

Italy |

Upland |

Rewilding*, habitat connectivity |

100,000 |

|

Oostvaardersplassen |

Netherlands |

Lowland |

Rewilding*, wetland with species reintroduction |

5,600 |

| - | Location | Land type | Project type | Project area (ha) approx. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cairngorms Connect |

Cairngorms, Scotland |

Upland |

Peatland and woodland restoration |

60,000 |

|

Forsinard Flows |

Sutherland, Scotland |

Upland |

Peatland restoration |

21, 000 |

|

Holnicote Estate |

Somerset, England |

Lowland |

River restoration |

4,000 |

|

Pumlumon |

Mid - Wales |

Upland |

Peatland restoration, native woodland expansion and sustainable land management |

40,000 |

|

South west Norway |

Norway |

Upland |

Natural woodland regeneration |

Undefined Regional scale |

|

The Northern Upland Chain Local Nature Partnership |

Northern England |

Upland |

High nature value farming |

105,000 |

|

Tweed catchment |

Borders, Scotland |

Lowland |

River restoration |

500,000 (catchment area) |

|

Wallasea Island |

Essex, England |

Coastal |

Coastal management with nature-based solutions, restoration of wild habitats |

850 |

|

Wild Ennerdale |

Cumbria, England |

Upland |

Woodland restoration, sustainable land management |

4,750 |

|

Wild Ken Hill |

Norfolk, England |

Lowland |

Rewilding*, restoration of natural systems, sustainable land management, regenerative farming (agroecology) |

1,600 |

*Rewilding is mentioned for projects where ‘rewilding’ is an explicit objective. However, other projects can also contribute to rewilding landscapes.

Information collated for each case study

Information was collated for the 15 high level and ten detailed case studies. The latter includes the following information:

- Administrative and socio-economic context;

- Landscape and land-use context for the surrounding area;

- Environmental baseline prior to the LSNR restoration;

- Level of ambition in restoration/rewilding including vision, objectives and aims;

- Environmental and ecological impacts;

- Social impacts, including information on community engagement;

- Economic impacts;

- Key barriers and opportunities including land tenure, community opposition and integration with other land management aims;

- Partnership models and funding; and

- Additional resources.

Detailed case study interviews

Interviews were undertaken for the ten detailed case studies. The purpose of interviews with representatives of each LSNR project was to focus on key issues emerging from the desk review, exploring key barriers, local community and economic effects and different funding models. Interview questions were identified based on the review of the existing case study information, to reflect any information gaps or areas of interest and the project research questions.

The invitation to interview included a detailed project briefing paper. Once accepted, interview questions were developed and tailored for each case study and then sent to the interviewee prior to the interview. Interviews were conducted between December 2020 - January 2021 and took place via Microsoft Teams. Data obtained through the interviews were fully compliant with GDPR and all participants were provided with, and agreed to, LUC's privacy statement. An overview of the main interview topics is provided in Annex 6 - Case Studies Interview format.

The information collected through the interview process is wholly qualitative. It is also important to note that the views expressed by the consultees are not necessarily reflective of the organisation they represent; but are based on their own professional experience of the LSNR project. To maintain confidentiality and for data protection purposes, the names of the individuals interviewed for this research have been withheld.

All interviewees were given the opportunity to review the information for each case study to ensure they were content with how the information they contributed is presented.

Approach to the analysis

The project findings are structured around a number of research questions which were defined at the start of the study. These have been further expanded where appropriate to reflect issues which have been identified from the case study review process. The analysis of the case studies explores key opportunities and barriers identified from the case studies as per the research questions listed below and relates them to the Scottish context.

Research questions (grouped by themes):

Project aims, objectives and timescales:

- What are the principal drivers, aims and objectives of LSNR / rewilding projects?

- How have initial projects ‘seeded’ future projects?

- Over what timescale are projects planned, and implemented?

Have projects taken account of future environmental change (e.g. climate, increased risk of disease / pathogens) or are they aiming to restore existing or past ecosystems? How is resilience ensured?

Project benefits:

- What are the main benefits (environmental, economic and community) or services that have been delivered by different kinds of projects?

- What lessons are there in terms of optimising community and local economic impacts associated with projects?

- How do you ensure achievements and benefits are secured long-term? How do you avoid losing benefits derived from the project? Does this require loose/adaptive management?

Issues and barriers:

- What are the key barriers that have been encountered by projects in Scotland and elsewhere and how have these been overcome?

- Were there any conflicts between restoration measures and other conservation interests or other land uses? What value was attached to the pre-existing biodiversity or landscape and was this seen as a barrier to change?

- What is the influence of land tenure (owner occupied, tenanted, community owned)? Are there specific barriers or opportunities that apply to schemes in lowland agricultural areas, in the Highlands, in areas with crofting or common grazings, on the coast or within the Central Belt?

- Did the projects encounter any cultural barriers, for example perceptions around the role of land managers or established land uses – and how were these overcome?

- Was deer management critical to nature restoration? How was management of deer achieved and funded? Is deer management placed on a sustainable footing for the future?

Delivery mechanisms:

- Are there particular partnership / delivery models that make it easier or more difficult to initiate and deliver these projects?

- How are successful projects facilitated and developed? How is momentum maintained?

- What kinds of funding models have proven successful in delivering projects? What novel models offer potential to combine public and private finance, tapping into emerging markets for carbon or other environmental ‘goods’?

Fitting LSNR / rewilding with the wider environmental policy context:

- What policy changes are needed to make LSNR / rewilding in Scotland more attractive to landowners, land managers and communities?

- How can LSNR / rewilding projects form part of high nature value farming initiatives? Should LSNR focus on low quality or marginal farmland?

- Is there scope to deliver LSNR / rewilding within broader management or delivery vehicles such as biospheres, national parks, National Scenic Areas or the Central Scotland Green Network (CSGN)?

Local economic impacts

The economic impacts of LSNR / rewilding projects have been identified through exploration within the detailed case study interview questions. Broadly the economic effects depend on:

- Land management practices and associated employment and expenditures;

- Changes in the delivery of ecosystem services (provisioning, regulating and cultural services) and the opportunities they provide for local businesses; and

- Other effects (e.g. damage from pests and predators, effects on land prices, community reactions etc.)

Large-scale nature restoration involve changes in land management which are likely to have direct impacts on employment and purchases of goods and services (impacting on local supply chains). To assess economic impacts, we need to examine:

- Changes in employment in existing land management sectors (agriculture, forestry, game management etc.).

- Changes in expenditures on purchased goods and services (contractors, machinery, equipment, materials, chemicals, other services etc.), especially locally sourced services.

- Employment and expenditures– including capital operations (e.g. restoration works, fencing etc.) and ongoing management operations (e.g. monitoring, deer management etc.).

Higher levels of employment and expenditure increase the cost of managing land but also its impact on local economies (in terms of jobs and local incomes). Restoration involving lower levels of management interventions (e.g. natural regeneration of forests) may be cost effective in meeting conservation priorities but can have negative impacts on local economies. However, there can be new opportunities arising from these projects particularly in areas with declining economies.

Ecosystem Services

In relation to ecosystem services, LSNR / rewilding can be expected to affect:

- Provisioning services – e.g. output of food, timber and other materials. There may be changes in the volume (e.g. reduced food output), type (e.g. replacement of commercial breeds with conservation livestock, farming with wild food) and value of outputs. There may also be changes in the way produce is processed and marketed (e.g. potential growth in small-scale local processing businesses).

- Regulating services – e.g. carbon sequestration, water purification, flood management – which may have market values (e.g. traded carbon) or wider benefits for society.

- Cultural services – e.g. recreation, tourism, education, scientific benefits. Tourism impacts may involve increases in general visitor numbers as well as more specialist interests (nature watching, hunting, fishing, scientific study). These may have positive impacts through visitor expenditures on site and in wider local economies. LSNR / rewilding projects may also have a marked impact on other non-marketable cultural services (e.g. sense of place, aesthetics).

Other Effects

Other effects which need to be considered include:

- Impacts from pests and predators – concerns have been expressed about the reintroduction of large predators such as lynx and wolf and damage caused by other species such as beaver. Effects on populations of herbivores and the impacts of non-native species also need to be considered.

- Effects on land prices and land value – these depend on the effects of changes in ecosystem services identified above and could be negative (e.g. reduced agricultural land values) or positive (e.g. enhanced tourism, countryside sports, payments for public goods such as carbon credits). Land value is important given that the capital value of land is often used as a lever for other funding / loans. The impact of woodland planting for instance under the current capital value approach can affect the ability to obtain funding or loans: a broader approach of natural capital valuation would be beneficial here.

- Community impacts – LSNR / rewilding projects and their associated economic impacts may affect local communities positively or negatively, by changing the identity and perception of the local area and its people, and the relationship communities have with an area.

Sensitivities

The report has drawn on a range of information from desk-based review and interview responses. The case studies highlighted a number of sensitivities, particularly around conflicts between land management aims and between key players within different projects. The case studies were based on interviews with key contacts, but did not gather the wider views of surrounding land managers or communities and their perceptions of the case study projects.

Context for Large Scale Nature Restoration / Rewilding

Defining large scale nature restoration and exploring terminology

Ecosystem restoration (also referred to as landscape-scale or large-scale nature restoration) is defined as a process of assisting the recovery of ecosystems that have been degraded, damaged or destroyed (Gann, et al., 2019). Large-scale restoration of nature can significantly contribute to addressing the biodiversity and climate crises through the deployment of ecologically viable nature-based solutions, improving the conservation status and the connectivity of European sites (e.g. Special Protection Areas and Special Areas of Conservation), protecting and restoring carbon sinks and enhancing the functionality of biodiversity and ecosystem services (Fernandez et al., 2020).

Within the discourse of conservation and more recently ecosystem restoration, the terminology has been evolving rapidly. The boundaries between different terms are often blurred and unclear. Rewilding, as one of the newest terms, is a specific form of ecological restoration that promotes self-sustainable ecosystems that provide important services to people and nature while requiring minimum human management in the long term (Fernandez et al., 2020).

Rewilding as a term emerged from the Wildlands Project, which was founded in 1991 and had the aim of creating North American core wilderness (Jørgensen, 2015). (The concept of wilderness has been the subject of debate on the American continent in particular with regards to first nations’ original use of the land.) The project focused on securing large-scale and well connected core areas and releasing keystone species such as wolves. The approach later became known as 3Cs approach (core areas, corridors and carnivores) (Lorimer, et al., 2016). The term rewilding is considered as controversial for a number of reasons. There are concerns often raised by communities within the locality of projects who have the perception that rewilding projects can lead to displacement. Historically, some conservation activities have led to displacement of local populations, as the areas have become protected for wildlife, watersheds, reefs, forests or rare ecosystems, while in others humans and wildlife have coexisted. There can be generalisations asserting a definite conflict between nature and human presence in protected areas, which is equally true for an assumption that harmonious and sustainable relationships between nature and humans can and will prevail (Agrawal & Redford, 2009).

Accordingly, it has been argued that rewilding, as a term, has been applied to a range of visions and land management practices and therefore has lost its original meaning (Jørgensen, 2015). However, broadly speaking when rewilding is used to describe a project, it usually points to a long-term aim of maintaining or increasing biodiversity, while simultaneously reducing the impact of present and past human interventions through restoration of species and ecological processes (Lorimer, et al., 2016). Rewilding also stresses the emotional experience and perception of wild nature and wild ecosystems without human intervention. In fact, conventional restoration projects often aim to minimise human intervention, however some level of management is critical to replace ecosystem processes that have been lost due to human activities or to maintain important aspects of cultural landscapes (Perino, et al., 2019). Therefore, it is difficult to clearly differentiate between large-scale nature restoration and rewilding; hence various types of projects along a spectrum were investigated in this research.

In Europe, unlike in North America, greater importance is afforded to large-scale nature restoration through approaches such as naturalistic grazing, which includes grazing hardy animals outside of a field-based farming system, or reestablishing a population of large herbivores. The second approach focuses on enabling large herbivores such as cattle, horses, wild boar, beavers or bison, to graze and browse and through this restore or create complex and species rich ecosystems on reclaimed areas or those previously used for agriculture or forestry (Lorimer, et al., 2016). In Europe, agricultural activities may continue to some extent within the 'restored' landscape. For this reason, the project also looked at farms, and the type of farming systems that are found in nature restoration projects.

The definition of ‘large scale’ was explored early in the project inception and it was recognised that this varies within the landscape context. Although indicative thresholds were set to guide the case study selection of greater than 10,000 ha for upland examples and greater than 1,000 ha for lowland examples a more flexible approach was then applied. ‘Large-scale’ case studies are partly dependent on land ownership and the development of collaborative partnerships. Land ownership patterns vary in different geographical locations with the largest case studies in Scotland being within the Highlands. Large-scale collaborative projects identified within Britain included Cairngorms Connect, the Northern Upland Chain Nature Partnership, Pumlumon, the Great Trossachs Forest and Sunart Oakwoods.

Within this chapter the term ‘rewilding’ is used where it is referred to in the relevant literature sources, however this report uses the term ‘large-scale nature restoration’, reflecting the broader scope of the study and recognition of the various stages and degrees of nature restoration represented within the case studies. Table 3.1 below illustrates the EU Biodiversity Strategy four-tier ecosystem restoration model. This model illustrates the different stages which may be relevant to the case studies included.

Table 3.1. EU biodiversity strategy four-tier ecosystem restoration model

|

- |

Types of areas |

Baseline |

|---|---|---|

|

Level 1 |

Satisfactory abiotic conditions. Key species, properties and processes of ecosystem patches and their functions, at site level and at landscape level, are in good to excellent condition. |

‘wilderness’ areas and N2000 habitats and species in Favourable Conservation Status (FCS), rivers and lakes in good ecological status (GES), marine ecosystems in GES |

|

Level 2 |

Satisfactory abiotic conditions, some disrupted ecological processes and functions, either at site level or at landscape level or at both levels. Reduced or declining diversity and key species, compared to L1 but retains stable populations of some native species. |

N2000 habitats and species not in FCS |

|

Level 3 |

Highly modified abiotic conditions, many disrupted ecological processes and functions, either at site level or at landscape level or at both levels. Dominated by artificial habitats but retains some native species and stable populations. |

Non-protected rural areas, not including intensive agriculture |

|

Level 4 |

Highly modified abiotic conditions, severely reduced ecological processes and functions, both at site level and at landscape level. Dominated by artificial habitats with few and/or declining populations of native species; traces of original ecosystem hardly visible. |

‘heavily modified ecosystems’ (e.g. Intensive agriculture, build urban areas, roads, airports, brownfield areas, heavily modified water bodies); heavily degraded ‘natural’ and ‘semi-natural’ ecosystems |

Adapted from Lammerant et al. (2014)

Key barriers and opportunities

Environmental and ecological

Nature restoration directly targets restoring ecological functions and processes instead of particular biodiversity compositional states, and as a result the effects of restoration may be indirect and unexpected (Perino, et al., 2019). Restoration efforts often mainly target vegetation, such as removal of non-native plants and purposeful planting of desirable native species. Such an approach hopes to restore the plant community and allow other services to recover in their own time (Kaiser-Bunbury, et al., 2017). It is suggested that for successful nature restoration, ensuring long-term protection of biodiversity and landscapes and utilising a flexible approach to the project are crucial (Perino, et al., 2019), so is realising that ecosystems are dynamic and are constantly changing (Carver, et al., 2021). It is also shown by Macmillan (2021) that rewilding is likely to generate significant environmental benefits when comparing to competing land uses especially in terms of ecosystem processes, biodiversity and climate change mitigation. However, this may differ by location, and in areas such as upland SACs, SPAs or SSSIs, it may be more uncertain (Macmillan, 2021), depending on the nature of the restoration project and the requirements of key species.

Large herbivores play an important role in providing dung and carrion, facilitating seed dispersal, and modifying the physical and biotic environment in many ways e.g. by grazing, trampling, and building dams (by beavers). In rewilding, they play a key role in restoring trophic interactions (Carver, et al., 2021). Due to the absence of top-down control by carnivores, high densities of large herbivores can negatively impact the abundance and diversity of other species groups (Perino, et al., 2019). Therefore, management of herbivores is necessary to enable restoration of other species. Most natural habitats across the UK are under pressure from deer (Fuller & Gill, 2001) – and notably so in the Scottish Highlands. Hence, deer management is an issue and achieving sustainable numbers is critical to the restoration process.

Studies have suggested that there are a number of risks and uncertainties specifically associated with rewilding mainly because of its experimental nature (Lorimer, et al., 2016). Some of the key risks are linked to species introductions and reintroductions, such as a depletion of donor populations, risks of introducing disease, or low genetic variability among the introduced individuals (ibid.). Uncertainties relate to effects of bringing species back or taxon substitution, where similar species are introduced instead of the original ones (ibid.). There are also limitations linked to the status of animals, in terms of whether they are kept or not kept and protected by the 1976 European Convention which requires ensuring that animals are free from hunger, thirst, discomfort, pain, injury and disease; additionally leaving animals to die may have a negative public response (Lorimer, et al., 2016). Scotland has legislation for this through the Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations (NSFR, 2014) Permissions and licensing are provided by NatureScot and the Scottish Government. One of the examples illustrating this issue is Alladale Wilderness Reserve in Scotland, where the vision of the project has been restricted by existing regulations, under which the reserve has a zoo status and requires keeping elks separate from predators (Lorimer, et al., 2016).

Additional obstacles in nature restoration, identified by Sandon et al. (2019), are linked with conservation policy, which serves as an institutional barrier to rewilding. Specifically, it requires the maintenance of the UK’s 77 Habitats Directive Annex I Habitats. This Directive is based on a fixed date baseline of 1994 and as a result promotes a static and preservation focused conservation approach to ensure that the species are in a ‘favourable condition’ (Sandom, et al., 2019). This approach however fails to recognise the natural dynamism of habitats and species, and the need for adaptive approaches. Moreover, landscape management policies do not provide sufficient opportunities for nature restoration to be implemented on a broader scale, because they incentivise damaging agricultural activities on lower quality soils, hindering opportunities for nature to flourish (Perino, et al., 2019). Measures to mitigate the adverse effects of these agricultural activities, such as agri-environment schemes, have been historically underfunded (RSPB, 2018).

Resilience to climate change

It is important to recognise that future climate change will present challenges to the meaning of ‘restoration’. Climate change impacts pose significant uncertainties to rewilding projects, and they need to be considered at the planning stage to ensure that the project’s potential to absorb, ameliorate and tackle the effects of climate change is exploited (Carver, et al., 2021). The focus should be on creating functioning ecosystems in good condition, rather than restoring a particular ecosystem which may no longer be viable within a changing environmental context. There are also opportunities for nature-based solutions with the restoration of natural processes and habitats that contribute to the resilience of society and the environment to climate change, such as reducing flood risk or safeguarding carbon stores.

Social

Humans cannot be separated from nature. When making plans to restore nature, humans, their impacts and relation to the place must be included (Jørgensen, 2015). Over the centuries, humans have influenced species composition and their networks by hunting, harvesting and planting selected species for agriculture and forestry (Perino, et al., 2019). Intensification of agricultural practices and simplification of landscapes from the 20th century has had a severe impact on biodiversity (Wilson, et al., 2009). However, it is also suggested that rewilding requires a paradigm shift in the co-existence of humans and nature so that fully functioning trophic systems are possible and degradation and overexploitation of ecosystems are no longer accepted (Carver, et al., 2021).

In Scotland, large-scale nature restoration has not been positively embraced in all locations, especially by local communities, as it is potentially reminiscent of the forced displacement that took place during the Clearances of the Highlands in the 19th century (Lorimer, et al., 2016). Research conducted by McMorran, Price and Warren (2008) has highlighted that the Clearances of the Highlands still provoke powerful emotions. These became particularly apparent during the long process of identifying Wild Land Areas. Some local people have strongly objected to labelling land on which generations of their ancestors had lived and worked as ‘wild’ as they felt that this equalled to erasing human history from the picture (McMorran, et al., 2008). Careful consideration of the value attached to cultural landscapes and recognition of the fact that nature restoration may be in conflict with the current norms (e.g. of those living locally and those who derive benefits from a landscape who may live elsewhere) are needed. Taking such approach may result in a conclusion that a project is not appropriate in a certain location (Lorimer, et al., 2016). Resistance to nature restoration from landowners and occupiers was mentioned by multiple studies reflecting a variety of cultural, economic, and practical factors (Sandom, et al., 2019). Landscape-scale projects will require collaboration and long-term commitments from individual landowners in order to apply more ambitious nature restoration plans (ibid.). It is important to have a thorough understanding of interacting ecosystem processes leading to resilience, and of the socio-economic context in which an ecosystem restoration project will take place (Perino, et al., 2019). There is the potential for establishing partnerships, which will often be required for LSNR, and these should include local communities, landowners, farmers and other stakeholders. If a consensus is not found, and a project is imposed against the will of public groups, there is the potential for serious conflicts (Lorimer, et al., 2016). Moreover, not only local partnerships, engagement and support are crucial for the success of a rewilding project, but also inclusion of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and other local knowledge. As these can help inform adaptive management framework and gathering evidence (Carver, et al., 2021).

Economic drivers and impacts on rewilding

It is suggested that rewilding can outperform low-yielding forest plantations in terms of sequestered carbon which remain in-situ (Svenning, 2020), and emissions from, for example, soil disruption, would potentially be diminished (Macmillan, 2021). Moreover, LSNR / rewilding can provide numerous secondary benefits for Scotland as illustrated by development of green finance options, including Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES), biodiversity banks and carbon credits / offsetting, in addition to tourism related benefits (Svenning, 2020). There is scope to further develop and capitalise on nature-based tourism, which is currently worth at least £1.4 billion annually to the Scottish economy and supports approximately 39,000 full-time jobs (NatureScot, 2019). To give an example, currently tourism associated with sea eagles on the island of Mull attracts visitor spending of about £2 million annually and dolphin watching off the east coast another £4 million. Reintroductions of species could deliver similar profits and for example, a beaver release site was estimated to be worth around £2 million to the local economy (Bryden, et al., 2010).

Economic barriers to such projects include subsidy policy which has traditionally focused on supporting production and associated activities rather than seeing the different values of the ecosystem services (Sandom, et al., 2019). Another barrier is the inheritance tax relief which allows for land and property occupied for agricultural purposes to be passed to the next generation free of tax, but only when agricultural activities are continued; hence it does not apply to land used for conservation purposes (ibid.). A further barrier is the cost of acquiring the area of land needed, as well as the opportunity costs/income foregone of long-term changes in land use, particularly on more productive agricultural land or where current land uses are heavily subsidised by landowners.

Funding/Partnerships

As mentioned briefly before, successful large-scale ecological restoration will require partnerships from across the area designated for a project. Establishment of partnerships may take time and will demand resilience considering different organisational structures, staff turnover and short-term funding. Moreover, it is crucial to bring all stakeholders on board, establish trust with them and ensure that they are aware of the availability of external funds that can support conservation land uses. Some of the key obstacles to overcome will include finding institutional strategies that secure long-term conservation outcomes that can be continued beyond the funding period and provide income to support the longevity of the project. Where community-based projects are to be taken forward, there may be different support needs and partnership working required to bring these to fruition. Large-scale nature restoration projects are considered to be complex due to their nature of blended governmental and private tenure and management requiring the creation of hybrid institutions and evolving partnerships (Adams, et al., 2016). In fact, large-scale projects may originally be less profitable for landowners (Adams, et al., 2016), hence government involvement and funding are crucial. The case studies identified that there are a range of additional economic benefits that can be realised through LSNR / rewilding projects, such as contributing to local supply chains; these should be considered (and quantified if possible) when developing a project. Diverse landscapes can support a greater range of income streams as shown by the examples of Knepp Estate or South West Norway.

Guiding principles for rewilding

Carver et al. (2021) have drawn on a global advisory group of rewilding experts to outline a definition and a series of ten guiding principles for rewilding. The principles explicitly state that rewilding sits upon a continuum of scale, connectivity, and level of human influence, and aims to restore ecosystem structure and functions to achieve a self-sustaining autonomous nature. It recognises that the context for rewilding projects is key to success and implementing site-specific interpretations will be most successful at achieving the aims of rewilding. The principles are set out below and include additional description and interpretation within the Scottish context and in relation to socio-economic implications.

|

Principle |

Key elements |

Possible socio-economic implications |

What are the barriers and opportunities for mainstreaming? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Rewilding utilizes wildlife to restore trophic interactions. |

The presence of large herbivores, apex predators, and keystone species should regulate species populations and result in self-sustaining ecosystem |

Re-introduction of apex predators raises risk or perceived risk of conflicts with socio-economic interests, e.g. through predation of livestock. As well as costs of damage inflicted, this has implications for management of perceived conflicts, and may require schemes to manage conflicts, avoid damage or compensate for losses. Incorporating large herbivores into self-sustaining ecosystems is likely to require less human management than livestock farming systems, with limited costs, employment or revenues, though establishment will have cost and labour implications, and there may be opportunities for sales of high value meat at low volume. Predators and large herbivores may be attractive to visitors and help to enhance tourism revenues, with positive economic impacts. |

What tropic levels are missing? What keystone species could play a role in the ecosystem? What are the i) ecological, ii) physical iii) landownership and iv) societal barriers to restoring the damage? |

|

2. Rewilding employs landscape-scale planning that considers core areas, connectivity and co-existence. |

Core areas with self-sustaining natural ecosystems Connectivity between core areas Coexistence between wild species humans, and livestock |

Landscape-scale planning for rewilding requires skills development and creates new employment opportunities for specialist landscape planners. |

What are the i) ecological, ii) physical and iii) landownership barriers to establishing core areas and connected zones? |

|

3. Rewilding focuses on the recovery of ecological processes, interactions and conditions based on reference ecosystems. |

Reference point of a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem

|

Ecosystem restoration requires capital works, incurring costs and generating employment, and sometimes revenues (e.g. sale of non-native timber) Recovery of ecosystem processes should enhance the delivery of a range of ecosystem services, with benefits for people and the economy – e.g. enhanced regulation of water quality and flows should reduce damage costs and investment in flood defences/ water treatment infrastructure. |

What is the ecological reference point? What native species or habitats should be being sought? |

|

4. Rewilding recognizes that ecosystems are dynamic and constantly changing. |

External and internal change over time is a fundamental attribute of ecosystems. Rewilding should provide space for this natural change. |

Linked to 3., dynamic ecosystems should be more resilient to future change (e.g. as a result of climate) and maintain ecosystem service delivery and its socio-economic benefits over time |

What are the current and future threats to the ecosystem (storms, floods, wildfire and large-scale changes in climate, agricultural land use change, agricultural impacts on water quality, aquaculture, shipping, flood defence etc.)? How does the project aim to respond to these threats? |

|

5. Rewilding should anticipate the effects of climate change and where possible act as a tool to mitigate impacts. |

Rewilding projects have medium to long-term timescales and should have the capacity to absorb, ameliorate and or tack the effects of climate change. Habitat connectivity is important to this. |

Restoration of ecosystems such as forests and peatlands can be a cost-effective means of mitigating climate change, reducing climate impacts and costs, and attracting carbon market investment, as well as enhancing ecosystems resilience to climate change, linked to 3 and 4. |

What are the opportunities within the landscape for climate change adaptation and mitigation? |

|

6. Rewilding requires local engagement and support. |

Rewilding should be inclusive of all stakeholders and encourage public understanding, and address barriers to acceptance. |

Community and stakeholder engagement are integral to rewilding, building a significant social dimension; effective engagement should help to ensure that rewilding delivers socio-economic benefits, including benefits for recreation. Volunteering plays an important role in some projects. |

What are the characteristics of the local community and population? Who are the key stakeholders? How are the local community engaged with the LSNR? What barriers and opportunities are there? |

|

7. Rewilding is informed by science, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and other local knowledge. |

Local knowledge can inform rewilding projects, although care should be taken to acknowledge knowledge gaps. Projects can form the basis for knowledge generation, data and information of use to further projects. |

Implications for skills and employment for scientists, and engagement of local communities to ensure that rewilding benefits from local knowledge |

What existing knowledge is there about the area (e.g. designations), what is the local community’s level of engagement with the ecosystem? What knowledge can the local community provide that would be beneficial for the project? |

|

8. Rewilding is adaptive and dependent on monitoring and feedback. |

Monitoring is essential to understand whether rewilding is working as planned. Rewilding projects should use data to identify problems and possible solutions. |

Implications for skills and employment for ecologists engaged in monitoring of rewilding schemes, and communications specialists engaged in community engagement and feedback |

What monitoring and feedback is required? What ways are there to ensure monitoring and feedback? |

|

9. Rewilding recognises the intrinsic value of all species and ecosystems. |

Natural ecosystems provide ecosystem services, but rewilding should primarily be an ecocentric rather than anthropocentric activity. |

Biodiversity policies recognise that natural ecosystems have intrinsic value as well as being important for delivery of ecosystem services of benefit to people; rewilding may deliver intrinsic values more cost-effectively than human interventions |

How much can human control be removed? What management interventions are likely to be required? |

|

10. Rewilding requires a paradigm shift in the co-existence of humans and nature. |

Society should no longer accept degraded ecosystems and over exploitation of nature. |

Important role of awareness raising and engagement to encourage people to rethink their relationship with nature and support this paradigm shift |

What are the opportunities for changing public perception of degraded and exploited ecosystems? |

Land ownership, land valuation and land taxation system in Scotland

Land ownership in Scotland may pose certain challenges to large-scale nature restoration projects, as a significant proportion of land is concentrated in few hands. The Scottish Government has aimed to map who owns which part of the country and so far, only managed to register about a third of the country’s total land mass. It is estimated that 57% of rural land is in private hands, with approximately 12.5% owned by public bodies, 3% under community ownership and 2.5% owned by charities and other third sector organisations. It is suggested that as much as over a half of the country’s rural land is owned by only 423 people. By far the biggest landowner is the Scottish nation, on behalf of which, government agencies and other public bodies manage the land (Scottish Government, 2014).

One of the key issues linked with private landowners is that they often are absentee landlords living elsewhere, not paying much attention to the land. According to Registers of Scotland (RoS) 6% of landowners are registered with an address outside of Scotland. The vast majority of these live elsewhere within the UK, however about 25% of these landowners live overseas. Hutcheon (2016) cites sources estimating that 750,000 acres of land are owned in overseas tax havens, while another separate RoS data suggests that offshore companies own property in Scotland worth £2.9bn. Owning property through tax havens means that the landowners do not pay inheritance duties and capital gains tax (Picken & Nicholson, 2018).

The Scottish Land Commission report suggests that land value taxation could help deliver Scotland’s land reform objectives and to introduce a more progressive and equitable system (Scottish Land Commission, 2018).

Study findings

The following chapters set out the findings of the 15 high level case studies and ten case studies selected for detailed analysis of Large-Scale Nature Restoration (LSNR) and group the research questions by theme:

- Project aims, objectives and timescale

- Project Benefits

- Issues and Barriers

- Delivery mechanisms

- Fitting large-scale nature restoration and rewilding within the wider policy context

The findings on the 25 case studies are followed by Green Finance section, which explores issues around green finance.

Project aims, objectives and timescale

What are the principal drivers, aims and objectives of LSNR / rewilding projects?

Project baseline

Understanding the environmental baseline before the start of aproject is important for measuring the degree of change which the project brings about.. A landscape which already includes a higher proportion of the features or habitats that directly support the project vision will provide a different starting point to a highly managed landscape that has lost the majority of the habitats or species which the project is seeking to restore.

Within the fifteen high-level case studies, there appears to be some distinction particularly between Highland Scotland, which include a core of existing habitats, (such as native woodland), and those which are located in more intensively managed arable or pastoral landscapes and are seeking to create habitats from a less biodiversity rich baseline.

Case studies where existing native woodlands were identified as part of the baseline include Alladale, Bunloit, Glen Affric, Glen Tanar, Great Trossachs Forest, Sunart and Thorneythwaite Farm. The benefit of existing native woodland are that it provides a key seed source for natural regeneration and ecosystem restoration, supporting the project alongside actions such as woodland planting and grazing management. However, the degree to which the quality of the environmental baseline influences the vision and ambition of the project is not clear, from the current sample. Some of the examples within the fifteen case studies include projects with high levels of ambition for nature restoration which are not based on existing high quality habitat such as Great Fen, Knepp Castle, Steart and Oostvaardersplassen.

Another factor identified from the case studies and linked to the existing environmental baseline is the association with existing protected areas. From the high level case studies, those with existing national or international conservation designations include Alladale (SAC), Glen Affric (SAC and SPA), Glen Tanar (SAC), Great Fen (NNR), Great Trossachs Forest (designated a NNR during the project operation), Sunart (SAC), and Thorneythwaite (SAC). (Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs), were developed under the European Commission ‘Habitats Directive’ (Directive 92/43/EEC) and the ‘Birds Directive’ (Directive 79/409/EEC). SACs are strictly protected sites designated under the Directive 92/43/EEC (the ‘Habitats Directive’). SPAs are strictly protected sites classified in accordance with Article 4 of Directive 2009/147/EC (the ‘Birds Directive’) for rare and vulnerable birds (identified in Annex II of the Directive) and also for regularly occurring migratory species. These Directives resulted in legislation being adopted into Scots law through The Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994 as amended. Collectively, SPAs, SACs and Ramsar sites will be referred to as ‘European sites’ in this report.) From the international examples the Central Apennines includes the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Parks. As an alternative driver, land abandonment in the Greater Coa Valley means that nature restoration provides a good opportunity to change and boost the local economy.

Project vision and aims

The vision of eleven of the high-level case studies is the restoration of naturally functioning ecosystems. This is the case for Alladale, Bunloit, Glen Affric, Great Fen, Great Trossachs Forest, Knepp Castle, Steart, Sunart and the three international examples of the Greater Coa Valley, Central Apennines and Oostvaardersplassen. However, within these examples there are also varying levels of economic productivity from agriculture and forestry. Examples which are seeking to maintain a higher proportion of other traditional land uses include Glen Tanar which seeks to maintain farming, forestry and sporting activities. Balcaskie and Temple Farm are incorporating areas of high nature value alongside larger areas of agricultural production.

For the detailed case studies, the aim of restoring biodiversity or supporting the recovery of natural processes was common to all the projects examined in greater detail, though their emphasis and focus varied considerably.

Several were focused on areas where peatland restoration and management is a key objective. These included Forsinard Flows in Caithness where a key objective was to restore peatland damaged by coniferous plantations established in the 1970s and 1980s, and Pumlumon and the Northern Upland Chain, both of which have extensive areas of blanket bog and peat which had been damaged by past land management practices such as drainage.

Other projects are focused on the water environment, aiming to restore natural river systems, enhance riparian habitats and, across the wider catchment, tackle issues such as flooding or poor water quality. The Tweed Forum, for example, which is a partnership approach rather than a project as such, has worked across the Tweed catchment, facilitating a wide range of projects focused on the water environment. At a smaller scale, the Holnicote Estate has sought to deliver sustainable flood management, initially focused on the river itself but more recently extending into management of the wider catchment. Similarly, the Wild Ennerdale project looks to restore natural processes along the catchment that serves Ennerdale Water.

One case study project, Wallasea Island in Essex, was in part designed to create coastal and particularly intertidal habitats to compensate for losses elsewhere caused by sea level rise.

In contrast to these NGO and public agency led projects, Wild Ken Hill provides an example of a private estate where the decision to change direction reflected a desire to address radically the climate and ecological emergency and, in the face of commercial challenges, to put the farm business on a more sustainable footing.

Excluded from this list is the example of south-west Norway which does not have aims as such but is the product of patterns of land ownership and management, a sustainable approach to deer management, a high level of economic support and devolution of decision making to rural communities.

Wider project objectives

All projects have a broad range of environmental, social and local economic objectives and are designed to deliver multiple benefits. Common amongst these objectives are the following themes:

- Creating new opportunities for public access and recreation, including in areas where opportunities to experience nature were previously limited: The Wallasea Island project, for example, aimed to provide an extensive area of accessible coastal land for the quiet enjoyment of nature and open space through the creation of new coastal wetland habitats of high value for wildlife.

- Raising public awareness of key climate and / or biodiversity issues, such as the importance of managing the carbon captured and stored in peatland: the Forsinard Flows project, for example, aimed to restore blanket bog while promoting and developing knowledge about the role of peat and carbon storage.

- Demonstrating the potential to move to more environmentally and economically sustainable forms of land management in areas where farm incomes have been low and declining: The vision for the Northern Uplands Chain Local Nature Partnership (LNP), for example, is to produce locally distinctive, high-quality food in a way that secures the long-term economic viability of High Nature Value farming and that is characteristic of the uplands. Ken Hill Estate aimed to demonstrate use of 'rewilding' as a tool for environmental benefit and as a way for landowners/managers to reinvigorate businesses. South-west Norway provides an interesting example of how an environmentally and economically sustainable model could work.

- Building resilience to climate change and other land management or economic changes: The Pumlumon project, for example, aimed to use peatland restoration to increase water storage and reduce the risk of downstream flooding in an area of Wales with high rainfall and projected increases due to climate change. Wallasea Island aimed to deliver a more sustainable approach to managed coastal realignment in the face of sea level rise due to climate change.

- Building partnerships, supporting dialogue, demonstrating and sharing best practice and facilitating change: The Tweed Forum, for example, aimed to engage a wide range of stakeholders from government, agencies, local communities, interest groups and landowners.

- Supporting local economic diversification including a focus on new local businesses and ecotourism: Most projects aimed to use nature restoration to support sustainable tourism and recreation by creating new access opportunities, habitats or enhanced landscapes. Pumlumon, for example, aimed to create a new wildlife-based attraction while new ecotourism businesses were an important element of Ken Hill Estate's new business model.

- Enhancing environmental quality – soils, landscape, water quality and air quality: Ken Hill Estate, for example, identified 'recovered' soils as a key objective in achieving its new model of land management. River and peatland projects aimed to address issues of soil erosion and improve water quality.

Many of these objectives underpinned the broader aims of the projects and should not therefore be regarded as secondary objectives.

How have initial projects ‘seeded’ future projects?

The initial short-term project examples of Holnicote Estate and Forsinard Flows are useful to illustrate discussion of how one project may 'seed’ other projects and to understand whether this can lead to greater gains in the future.

It is not as simple as an initial project leading to greater gains. However, what emerges is that an initial project generates momentum for further nature restoration work in a given area, often with wider stakeholder engagement and improved access to funding as there is a track record of action being taken on the ground. The wider policy context is also of particular importance, including the focus on achieving climate change targets and the role of peatland restoration to sequester and store carbon (mostly led by the Peatland ACTION project in Scotland). The ongoing peatland restoration work by the RSPB at Forsinard Flows demonstrates these points, with a longstanding focus on peatland restoration meaning they hope to now be in a place to secure a 5-year funding programme for peatland restoration with the Scottish Government - a vast improvement for project planning and restoration success from the current annual grant system. Long-term planning is vital to effectively deliver larger scale projects and sustain the benefits. It is also important for operational delivery of peatland restoration; by providing job security, it encourages key contractors to make investments in equipment.

River restoration and natural flood management work at Holnicote Estate has evolved in a short space of time from focusing on minimising flood risk through conventional, in-channel engineering to restoring natural river functions through a pioneering approach that works with natural processes to restore the water connection to its floodplain, delivering greater benefits for floodplain function, biodiversity and local communities. The evolution of thinking at Holnicote Estate of a joined up, landscape-scale intervention has developed in tandem with local partners (e.g. Exmoor National Park) and the project aims and objectives fortunately aligned with those of available funding sources (EU Interreg 2 Seas Co-Adapt) to enable the project to begin when it did in 2018.

Over what timescale are projects planned, and implemented?

The timescale of the visions set out for the high-level case studies is not always clear from the available information. It can however be inferred to some extent from the ambition of the project; for example, those based on restoring woodland are based on the long-term timescale of tree growth (Sunart. or Glen Affric, as a woodland LSNR is based on a 150 – 200-year timescale. Great Fen, which is a wetland project, has a 50-year timescale. It is also recognised that flexibility is a key element of LSNR, as illustrated by the approach at Wild Ennerdale where high-level management plans at a landscape-scale allow space for natural processes to occur and for dynamic and perhaps unexpected change. Therefore, it is recommended that long-term projects are regularly reviewed and allowa level of flexibility.

The interview process for the detailed case studies enabled discussion of projects’ timescales. Both Forsinard Flows and Holnicote Estate Flood risk demonstration projects ran over short, discrete time scales (approx. 5 years), which aligned solely with funding sources. However, there has been, and continues to be, ongoing work to restore habitats at both sites (peatlands at Forsinard Flows and rivers at Holnicote Estate). The methods and approaches continue to evolve, with a shift to a new approach of Stage 0 restoration being piloted at Holnicote Estate (EU funded and 5-year project timescale from 2018-2023).

Wallasea Island, a coastal project, was initially intended to run over a shorter timescale than what transpired (currently 17 years). The initial planning permission was granted to 2019, 10 years on from the original consent for imported fill. However, the focus has been on the outcomes and how to deliver the project, rather than the timescale, and the method of delivering outcomes has evolved and developed over time. An adaptive approach can be hugely useful, with the focus on the desired outcomes rather than the method of delivery. Projects should not be fixed to a rigid timescale. Similarly, the Pumlumon Project began in 2007 after a long gestation period and is ongoing. (It should be noted that there is another, more recent project (commenced 2017) in a similar area to the Pumlumon Project. 'Summit to Sea' is being hosted by RSPB Cymru, and Montgomeryshire Wildlife Trust - who lead the Pumlumon Project - are one of the project partners alongside many other partners (e.g., The Woodland Trust, PLAS Marine Special Area of Conservation, Marine Conservation Society, Whale and Dolphin Conservation). The projects are two separate projects, but their aims are aligned.) It has been sustained through 5-year windows of funding much the same as the discrete project timeframes of Holnicote Estate and Forsinard Flows but is leading the way in exploring private financial models and new markets to support restoration, expanding upon the PES approach first adopted there.

Projects that have a longer-term, or indefinite timescale include the Tweed Forum, Wild Ennerdale, Northern Uplands Chain LNP and Cairngorms Connect. Due to their nature of being a partnership group combining key stakeholders, they are not defined projects as such and instead provide an approach to land management and a mechanism for delivery of specific projects. Tweed Forum and Wild Ennerdale are longer-standing partnerships that have been running successfully for 30 years and 20 years respectively, whilst Northern Uplands Chain LNP and Cairngorms Connect were established more recently, in 2012 and 2014 respectively. Although the Cairngorms Connect partnership is relatively new, its ambitions are long-standing with the foundations based upon a long history of management of the four individual partners across the project area. The Wild Ken Hill project began recently (2018-2019) and, with its long-term ambition, has no discrete time frame.

Working with natural processes requires an open and flexible approach. The Wild Ennerdale partnership consider natural processes to be the fifth partner in the project, and shy away from fixed timescales in which objectives must be achieved, to allow space for ecosystem processes to unfold and for management to respond accordingly. Their stewardship plan is based around a set of 15 principles that guide management decision making, with an overarching principle that any action taken should fit within, and refer back to, the vision at all times. The flexibility in approach is also important given the nature of discrete funding cycles which tend to fund LSNR projects. Furthermore, project teams or partnerships may be required to adapt project aims slightly to 'fit' with a potential funding source.

South-west Norway is unique insofar as it is not a discrete project or even a partnership, rather a set of circumstances at the regional scale that have allowed the unfolding of a process of natural woodland regeneration, over a long timescale. Regeneration has progressed since the 1950s and 1960s, though it has taken place more rapidly in the past 10 years. Eventually the woodland regeneration will slow as the extent of land available to regenerate is finite. One discrete active restoration project discussed was that of Hjerkinn (similar to Cairngorms plateau) which is largely government funded and has run in two phases from 2006-2020. The project involved restoring an active military range ,which required all vegetation to be removed due to the presence of unexploded ordnance. There were some key lessons learnt around techniques for restoration of blanket bog and woodland at 1000m above sea level, which could be of relevance to the Cairngorms.

Have projects taken account of future environmental change (e.g. climate, increased risk of disease / pathogens) or are they aiming to restore existing or past ecosystems? How is resilience ensured?

The emphasis of most projects is on moving towards land management practices that reflect and restore natural processes. In some cases, this represents changes to patterns of land management, and the restoration of ecosystems which existed in the past. In others, it means a radical change in land management and the creation of new ecosystems and habitats. Ken Hill Estate, for example, has developed a model which closely reflects the characteristics of three soil types present across the land holding. Areas of poor, sandy soil which were in arable cultivation until recently, provide a focus for rewilding. Areas of poorly draining soils are being used to restore fen woodland, while more productive soils provide the basis for regenerative agriculture alongside traditional conservation methods. The resulting pattern of land management is the product of working with the environment rather than a deliberate attempt to restore a landscape that has been lost. At the other end of the scale, the Wallasea Island Project has created a new and dynamic coastal landscape in an area that was previously under arable cultivation. The aim here is to create intertidal habitats to compensate those being lost elsewhere as a result of sea level rise and coastal squeeze. The project has created an artificial coastal landscape of excavated lagoons, sea wall breaches and areas of higher ground. It is again a solution based on working with natural processes but through the creation of a new and dynamic ecosystem.