Improving Condition Protected Areas Review - Condition Think-piece

Approaches for Improving Condition and biodiversity safeguard/enhancement

A think piece for discussion – by Colin A Galbraith and David Stroud.

1. Origin of the think piece and overall purpose

This paper considers issues identified by the Board of NatureScot who undertook a Deep Dive of their work on Protected Areas, recognising that there are significant challenges ahead in the monitoring and management of these areas. The Board commissioned their Protected Areas Committee (PAC), a sub-group of the Board, to consider:

'How best to deliver maximum value from Scotland’s protected area network in line with NatureScot’s statutory responsibilities and within budgetary constraints.'

The Board suggested that the following key areas should provide the framework for their consideration:

- Resourcing

- Improving Condition through new and existing mechanisms

- The potential of using protected areas as catalysts for the development of ecological networks

- How to achieve cultural shifts across the rural sector in the perception of protected areas as being either a constraint on activity or simply a source of funding

- Achieving greater public support for protected areas

- The implications of climate change, both as a means of reducing the scale and impacts of climate change and in terms of ecological response as systems become more dynamic.

The PAC agreed to focus their investigation around three themes and to commission “think pieces” for each as follows:

- Lessons which can be learnt from behavioural sciences for stakeholder and wider public engagement with protected areas

- The role of protected areas as a catalyst for and contributor to Ecological Networks

- Approaches for Improving Condition and biodiversity safeguard/enhancement

This paper is one of the series of three think-pieces addressing the issues involved and suggesting options or potential solutions to address them. It specifically considers:

“Approaches for improving condition and biodiversity safeguard/enhancement”

It is intended that this paper will form the basis of a webinar and that it will be used as part of the PAC’s investigations to inform the development of the 2022-2026 NatureScot Corporate Plan.

It is drafted to prompt discussion and summarises important underpinning issues. It addresses three key questions given by NatureScot staff to help focus the work; discusses options and priorities for the future and suggests the development of a trial of new approaches to setting management objectives and for the monitoring of protected areas.

Although focussing on protected areas in Scotland, the issues raised are common to protected areas at the European and at the global level in many cases.

2. Underpinning issues

2.1. The legal basis

Protected areas have long been a cornerstone of nature conservation practice, with a raft of legislation at a range of scales, including local, Scottish, UK, EU, European and global. The legal obligations are similarly varied, with protection in many cases being delivered through planning constraints.

This has resulted in a variety of “types” of protected area depending on their legislative origin and their particular features of importance. For example, within Scotland at present, a protected area could be an SSSI, (Scottish/UK legislation), National Nature Reserve (Scotland/UK legislation), Special Protection Area (SPA - EU Birds Directive), Special Area of Conservation (EU Habitats Directive) and a Ramsar Site (Ramsar Convention – Global legislation). It could also sit within a landscape designated as a National Scenic Area or National Park. Importantly, over recent years the development of protected areas in the marine environment has gathered pace with several important large areas now designated as Marine Protected Areas, (Scottish/UK/EU legislation), hence consideration of the issues surrounding protected areas in this paper relates to both marine and the terrestrial environments.

A key issue to consider now is how such a multitude of designations might be used to maximum effect in safeguarding and enhancing the biodiversity of such sites in a cost-effective and acceptable way and to deliver national and international obligations.

2.2 Brexit

Over recent decades much of the fundamental legal underpinning and requirement to monitor protected areas across the UK has originated from EU legislation. Four key pieces of legislation have been the Birds Directive (2009/14/EC), the Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92/43/EEC), the Water Framework Directive (Directive 2000/60/EC), and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, (Directive 2008/56/EC). Each of these Directives, and associated legal test cases that have come with their implementation have helped to steer the selection of protected areas and the level of protection afforded in each case.

With the UK now having left the EU, this previous baseline of protection has been removed, creating a new, and perhaps more uncertain situation although continuity legislation aims to create continued and equal protection for previous Natura sites under UK legislation. Whilst multiple legislative constraints still exist at many sites, albeit not directly derived from EU legislation, this changing situation, may provide something of an opportunity to introduce new approaches to protected area management and monitoring in particular.

Whilst the original modus of EU Directives was to allow a degree of flexibility in how they were implemented, the legal test cases related to them, linked to institutional culture across Europe perhaps led to a particular style and at least to a perception of inflexibility in how they should be implemented. The challenge and opportunity is now to consider how a new approach and greater flexibility can be developed that still ensures the effective management of these areas whilst responding to new challenges.

2.3 The twin emergencies of biodiversity loss and climate change impacts

Scotland, like much of Europe, is facing the inter-related crises of biodiversity loss and climate change impacts, (For example see the EU Biodiversity strategy) hence it is important to look more widely at how best to maintain and enhance biodiversity on protected areas, whilst also considering their role in developing nature-based solutions to climate change, and to do this as a key part of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

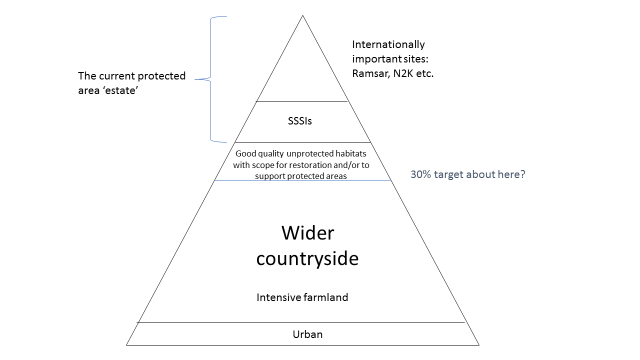

The recent international proposal to have 30% of land and sea by 2030 within protected areas (See Figure 1 below), is likely to gain prominence in the coming years as various global initiatives to tackle the twin emergencies are debated. Importantly, Scotland has probably already achieved this level of protection for marine protected areas.

Pyramid diagram of terrestial land use with protected areas at the top and urban areas at the bottom. The largest section in the middle being wider countryside (including intensive farmland).

Note that this target has probably already been met for marine areas around Scotland.

Perhaps the key challenge may be described as:

To manage protected areas in a cost-effective and flexible way in a rapidly changing environment, whilst still maintaining the overall cohesion and resilience of biodiversity in that area.

Whilst the need for action to maintain and enhance biodiversity, and also to tackle climate change is clear, it is not simple to fully evaluate the impact of changes on protected areas or to decide how they may need to be managed in future. Climate induced changes to the ecology of protected areas across Europe are dramatic, complex and happening at an unprecedented rate, (European Environment Agency 2020), for example, with this change happening in soft coastal areas, rivers, uplands and particularly noticeably in the marine environment.

Indeed, this rate of change is a key factor impacting on such areas.

In one important study Johnston et al. (2013) assessed the potential impacts of climate change on the UK SPA network by linking distributions of SPA qualifying species to current climate models and then running these forwards to 2050. Broadly, their findings were that: 1) in 2050 every SPA still ends up as internationally important for one or more species; but 2) these were largely not their current feature list as species distributions moved considerably. Thus, the national SPA network could potentially act as just that – a network of good semi-natural habitat ‘nodes’[1]. However, this is at variance with future site management focussed just on existing qualifying species.

This situation is occurring within a relatively fixed legal system of boundary determination on protected areas and of management that focusses on existing legal “features” within site boundaries derived in the 20th Century. Looking to the future it will remain important be clear about the overall purpose of protected areas and to build in a level of flexibility whilst supporting effective conservation action to allow these areas to maintain resilience but to adapt to these changes. The challenge is how to do this?

2.4 Challenges in setting management targets and measuring success

Protected areas should always have clear management objectives, sometimes supported by legal documents such as SSSI citations that indicate the focus of the legal requirement in that area, i.e. documents that define the ‘purpose’ of the site. Whilst this necessarily means that the conservation needs of the listed “features” will take priority, it may, consequently downplay the conservation needs of other ecological interest on that area. This approach, linked to climate induced changes can make taking a holistic and “climate flexible” approach to management difficult in practice in a resource limited world. A focus on features does not in itself preclude taking a more holistic approach, but it seems that simply put, at present conservation action and resources have to be directed to the legally defined feature, ahead of other considerations.

How then can targets for management be set when the area and ecology of a site may change rapidly due to climate change, perhaps in combination with other factors? Fundamentally many habitats are, by nature, transient or part of a succession, so how do we cope with this?

Some options, which essentially form a continuum, and which are explored further later in this paper are:

- Maintaining the status quo: manage for the legally defined features as now, and try to arrest any ecological change - keep things as they are now.

- Progressive change: manage the legally defined features but allow them to change over time.

- Natural processes: manage on a “whole site” basis using the existing boundaries of the protected area. The assumption here is that the whole site is of importance and that overall resilience is important.[2] Note that management objectives can of course be expressed in a range from highly prescriptive (as they are now – ‘absolute’ or quantitative) to more accommodating and flexible.

- Boundary flex: Develop a system of boundary change and flexibility for the protected area that ensures the overall maintenance of the feature/site set within a larger sympathetically managed landscape.

- The wider network: Consider sites as nodes in wider ecological networks and evaluate ‘condition’ and management objectives in this broader context.

Clearly none of these options are simple, and many would require a radical change in conservation practice, and the legal basis for it, in both the terrestrial and marine environments.

Defining and agreeing management objectives[3] and then measuring the success of management of any protected area therefore requires clarity at the outset on what the area is being managed for and which approach from the list above is being used to determine measurable management targets, so that “success” and cost-effectiveness can be effectively judged.

2.5 Monitoring and what to measure – developing a risk based approach

Several factors are fundamental in determining the shape of any monitoring programme on protected areas.

Firstly, it is important to decide what the results of monitoring will actually be used for. For example, will they be used to inform the local management of the area only and if so what features will take priority for management (existing legally defined features, the whole site or some other combination?) or will the results also have a wider use in terms of national or international collation and reporting. The results of monitoring at present may of course need to have multiple uses, for example at the local level, national assessment, and international reporting.

Secondly, the approach to monitoring may be determined by the extent of the protected area and on the management approach being taken.

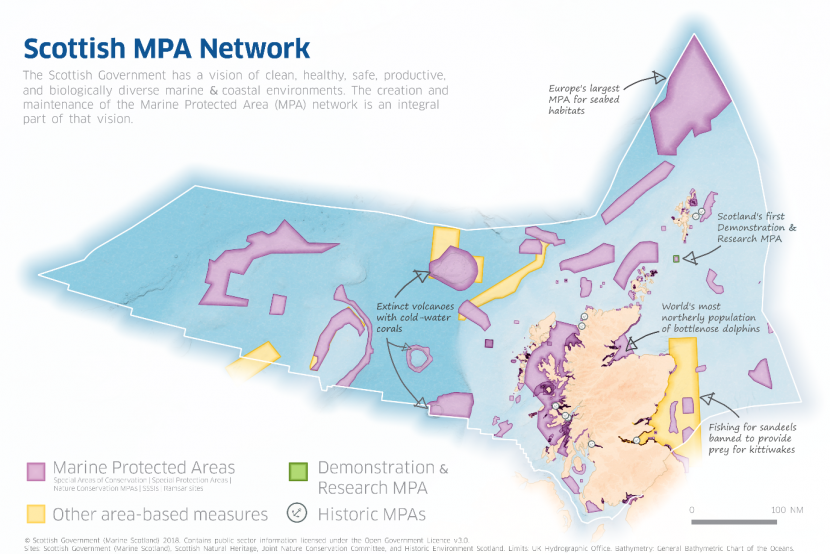

Map 1 published by Marine Scotland shows the size and distribution of Marine Protected Areas, emphasising that these areas are typically extremely large and of variable shape. Developing a monitoring programme for protected areas on this scale is therefore unavoidably challenging and expensive. A coherent monitoring programme has, however, been developed for Scottish Marine Protected Areas.

It is particularly important therefore to determine if monitoring is to address:

- Particular features (only) within a site.

- Whole sites (all features).

- A portfolio of sites (a number of areas holding similar features but not necessarily ecologically connected).

- A network of sites (a number of ecologically linked areas).

Such monitoring needs to be set alongside observed changes detected outwith the protected area system, so that it is part of a wider (national) framework for natural capital assessment.

Thirdly, there are judgements to be made about the intensity of monitoring required in each case; so how often or at what level of detail is data required, and with what certainty of detecting specified change? This may of course be guided by the questions being asked to inform management; by the relative fragility of the area, and by what rate of ecological change is already being observed. It may also be informed by the degree of threat any area is under, so for example it may be desirable to monitor a fragile and threatened habitat, or rare and ecologically sensitive species, more frequently and in greater detail than a habitat or species that is known to be stable and not threatened. Developing a tiered approach based on “risk” to inform monitoring intensity undoubtedly merits further consideration.

Fourthly, there are further judgements about the level of risk that is acceptable in not having accurate and timely information about the status of any area. This may vary depending on the focus of the monitoring programme; so for a portfolio of sites or a network, then a “risk based approach” may mean that only a proportion of the areas involved may be monitored, with assumptions made about how the results from this activity may relate to other areas in the network. Alternatively, if the focus of the monitoring activity is a particular site or feature, then clearly each would need to be monitored.

An observation in passing – NatureScot along with other Agencies across the UK is now the custodian of a unique data set regarding the state of protected areas. Some of this data is collected on a periodic basis and may have a patchy geographical coverage, however, it is the result of long-term, planned monitoring activity. At the global level, such long-term data sets are very rare and valuable assets. As protected areas change over time then having a clear set of baseline data will be invaluable.

The key overall point is that the approach used to monitor protected areas will be determined, at least in part, by the level of risk deemed to be acceptable, hence being clear on this aspect before commencing monitoring is important.

2.6 Ecosystems, ecosystem processes and Natural Capital

Ecosystems are critical in providing food, energy, medicines, sustaining air, water and soil quality and are the sinks for anthropogenic carbon emissions. These provisions are vital for human existence and for a good quality of life, as indeed are some of the intangible elements of ecosystems, providing for our overall wellbeing (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005).

Whilst protected areas in both terrestrial and marine systems in Scotland focus on particular features or characteristics for protection, it is timely to ask whether and how these areas contribute to wider environmental functioning and ultimately to the wellbeing of the Scottish population, and how this contribution might be measured and “valued”. The concept of “Natural Capital” (Helm 2015) has gained real traction with governments across the world and is helping to focus efforts to evaluate ecosystems. It is important that we are able to assess the contribution the Scotland’s protected areas make at the local and national levels. The question is how?

With the impacts of climate change and the need to assess conservation action at a wider scale then it seems desirable to consider the ecosystems represented on protected areas in relation to the wider systems of which they are a part and then to evaluate the health of the site in the context of those wider systems. Clearly focussing on ecosystem characteristics such as condition, function and resilience all play a part in measuring overall ‘health’.

Measuring ecosystem ‘health’ is a significant scientific and practical challenge, especially as it would need to be done at a time when resources to develop and test any new methodologies are particularly limited. That should not, however, rule out such consideration and some good examples of ecosystem assessment and monitoring have existed for some time, for example in assessing the overall health and significance of river ecosystems (Maitland et al. 1994) and in legislation requiring the active monitoring of rivers.

The challenge is to utilise such approaches to ecosystem evaluation to help develop an overview of the resource and to be able to report on this when required by government and others with a key aspect being communication to the public, local communities and stakeholders about the value of healthy ecosystems and what they deliver.

2.7 Cost effectiveness

Developing innovative, cost effective approaches to monitoring and to overall protected area management, whilst enabling a reliable evidence base to be maintained is a key aim. At a time of real financial constraint, this is likely to mean that current monitoring practices need to adapt; probably through incremental change rather than suddenly adopting a completely new system.

Monitoring on protected areas currently tends to be either undertaken or organised by a range of organisations. This begs the question whether there is room for more sharing of effort across government, agencies and with the non-government sector? Whilst individuals and organisations may differ in their interpretation of data and information, having a coordinated effort on data collection and a shared understanding of the meaning of particular datasets would, in itself be a significant achievement. Enhancing the buy-in to monitoring by the various stakeholders, owners and managers of protected areas, in partnership with NatureScot, could be a key aim as part of delivering the 30% by 3030 challenge and importantly, could prove to be a significant contribution to enhancing cost-effectiveness.

2.8 Professional survey, volunteer effort, citizen science and remote sensing

Over the last few decades monitoring of protected areas has been undertaken by a mix of surveys of specific features, mostly undertaken by ecological or geological professionals, with national level surveys mainly delivered by organisations utilising the efforts of volunteer workers e.g. of birds (British Trust for Ornithology and the Scottish Ornithologists Club), mammals (The Mammal Society) or invertebrates (Biological Record Centre), each adding essential context and site based information. Other than for SPAs[4] and ornithological features on Ramsar Sites, volunteers have not been used extensively in focussed surveys on protected areas and a question to consider is whether they could be more engaged in future, especially if they are already involved in other ways in the management of particular areas. As is apparent through bird monitoring, this would beneficially reinforce local community engagement with site conservation issues.

The use of remote sensing may have an important role to play in future at least in providing an overview of change in habitat extent and possibly in terms of habitat quality as the accuracy of interpretation increases. Indeed the use of satellite technology in ecological survey and monitoring is advancing rapidly, (Willis 2015) for example, and the use of drones for aerial survey (Hodgson et al. 2018), or the use of Environmental DNA (E DNA) each have the potential to shed light on existing and previous species presence in a particular area (Ruppert et al. 2019). It would be timely and appropriate to review the utility of novel or “nearly new” techniques to ascertain if they could be used in a cost-effective way to add value to the overall monitoring effort. However, it should always be demonstrated that new techniques actually effectively monitor the feature of concern. Thus, for the presence of saltmarsh monitored through earth observation images for example, does not and cannot inform on the status of breeding waterbirds there.

2.9 Data collation, reporting and wider communication.

The result of monitoring activity is the production of large quantities of data and information. A lack of a national biodiversity data sharing infrastructure has resulted in these data often being held in silos’ by the organisations who undertook the original data collection (although bird data for protected areas is widely available). There is, however, considerable scope to exploit technology, as well as develop better data sharing agreements to maximise access to, and use of environmental information to inform the future management of protected areas. The 24 recommendations set out in the Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum (SBIF) Review (2018) would create a national infrastructure to support a definitive evidence base for Scotland’s biodiversity. A key area of focus within the SBIF Review is to enhance the role, and sustainability of Scotland’s Local Environmental Record Centres to develop their niche as “regional data and information hubs”. Could creating a sustainable network of such hubs, providing complete coverage across Scotland, better inform the overall management of protected areas?

2.10 Knowledge and scientific judgement

The reliable interpretation of management effectiveness through a monitoring programme on protected areas requires that those undertaking the work have the necessary skills and experience to make judgements about the meaning of the results. Developing and maintaining such professional expertise linked to a clear decision making process on protected area management is therefore a key part of having an operationally effective scheme, enabling the correct interpretation of data and information collected. This is especially the case if any new monitoring scheme was to be introduced where it would undoubtedly be necessary to cross check the veracity of new results alongside results from existing monitoring activities. This is true also if a trial of new techniques were to be undertaken, where having specialist knowledge to help interpret the results would be critical.

3. Key questions

The following part of this think-piece takes the issues highlighted in the previous section as context for discussion around the three key questions that have been identified and agreed with NatureScot staff as the core of the approach for discussion.

3.1 Question 1.

How can we make better use of the legislation to safeguard not only the rare and vulnerable on protected areas but also biodiversity more generally in a changing environment?

3.1.1 Defining the purpose

As mentioned earlier, it is important to be clear about the purpose of each protected area or portfolio of protected areas. The current legal system, for example based largely on SSSIs in the terrestrial environment, does focus strict legal protection on particular features, however, this does not in itself preclude protection for other biodiversity or for provision of ecosystems services and wider nature-based solutions. The SSSI system includes the concept of “areas of search” segmenting the country and then aiming to ensure that particular features are selected in each of these, thereby striving to ensure representation across as large a geographical spread as possible. This approach has merit in terms of ensuring representation across the country but does focus management action on those features most “valued” for a range of reasons. It does not necessarily produce a “network” of protected areas but does produce portfolios of protected areas sharing similar features.

3.1.2 Selection

A different approach to site selection has been used in classifying Special Protection Areas (under the EU Birds Directive) compared to SSSI selection, where for SPAs, a list of “suitable areas” is drawn up and then the “most suitable” ones are put forward by government for classification, informed by a formal sufficiency assessment.

If the aim in future is to take a holistic approach to site selection this would require a change in the basis for the selection of protected areas by moving from a focus on features to “whole site biodiversity” selection, where perhaps areas of high overall levels of diversity or interest could be selected. (Note of course that some areas of low overall ecological diversity can still be of real value and of conservation significance, as can some areas where ecological recovery is required).

One area for discussion is whether a system of “suitable and then most suitable” biodiversity areas has any traction in terms of future conservation action or perhaps considering whether those areas with the greatest potential, may have merit in some cases? Is this worth exploring further?

3.1.3 Protected areas as part of the landscape

It is important to view protected areas in the context of the surrounding landscapes and seascapes, along with the policies and practices that are in place there to maintain or enhance biodiversity overall. Greater connectivity could prevent these areas being perceived as isolated “islands”, so that they are seen as an integral part of the overall landscape and seascape and part of a wider network of conservation management. Consequently, developing a landscape scale approach to the wider conservation of biodiversity could be valuable and for example, would fit with Governments land-use strategy (Scottish Government 2016) and other initiatives at this scale in the marine environment – see Map 1 above.

3.1.4 Flexibility and indicators

Before developing new legislation, it is important to consider what is preventing the use of current legislation to stimulate action to protect other biodiversity on protected areas? It can be argued that current legislation could be used to do this; for example the text of the EU Directives have requirements[5] and a degree of flexibility that has not really been fully exploited, however, perhaps new approaches can be developed now. Further engagement with the Council of Europe’s Pan-European Biological and Landscape Diversity Strategy would be useful in this context. Similarly, further examination of the use of indicator species, especially those either at high tropic levels or widely ranging, and their place in wider biodiversity assemblages could prove useful. So for example, protected areas for golden eagles Aquila crysaetos also encompass habitats used by many other upland species, whilst Marine Protected Areas for harbour porpoise Phocoena phocoena also help protect many other marine species and habitats. This, so called “umbrella effect” has been examined in detail across the Natura network.

Indeed, the wider Marine Conservation Strategy for Scotland includes a three pillar approach of conservation of species, sites and wider seas policies and measures, thereby utilising a mix of mechanisms in a complimentary way.

Would it be useful to explore the value of indicators and the “umbrella effect” in more detail, especially as indicators of wider ecological health and change?

3.1.5 Reporting and international action

The issues being considered in the context of managing protected areas in Scotland are common to other parts of the world, for example in Norway and Sweden (Fauchald et al. 2014), and in New Zealand, as well as across the countries of the EU where the legislative base is still more or less in common with that in Scotland.

A common challenge is how to put in place legislation that maximises the protection of nature; ensures resilience through adaptation to climate change; and where feasible that also helps mitigate the effects of climate change through carbon storage and sequestration. At the time of writing there is a very active global debate about nexus of biodiversity conservation, climate change reduction and sustainable development more generally (e.g. IPBES 2019). These issues and the wider debate are of direct relevance to the issues being considered here. It is important that the use and evolution of legislation learns from examples in other countries and that work undertaken in Scotland, in turn, helps to inform the ongoing international debate.

Further work to more fully evaluate the nature of legislation being implemented in other countries could be undertaken to inform actions in Scotland. Significantly, 2021 and beyond will be a key period to agree and implement new global, Post-2020 Biodiversity Targets (for 2030). How can this window of opportunity be used to focus and support any new initiative?

Given the coincident timing on the global debate on 2030 targets and the arrival of Brexit, it can be argued that although the next few years represent a period of some uncertainty, they are also an opportunity to introduce changes in legislation if required or to “reset” how the current legislation is implemented. For example, what level of reporting (e.g. at the Scottish or UK level) will be required and how will this influence the monitoring of protected areas on the ground?

In summary a new approach to the selection and management of protected areas, perhaps with multiple management objectives could be developed to include a more holistic approach to biodiversity conservation, but this will need further analysis in terms of legislative change that might be required. Further work to explore the value of indicators would be useful as would landscape scale studies to place protected areas in a wider context[6]. Comparing the scale of management and monitoring in the marine environment with that on terrestrial sites could prove valuable in setting wide scale management objectives. The next few years are a key time to develop new approaches.

3.2 Question 2.

Are we measuring the right things in our current natural feature focus on condition to give us a sense of overall health and change on our protected areas?

3.2.1 Assessing the health of protected areas

As highlighted earlier, the data to be collected and assessments to be carried out depends on the particular questions being asked, hence it is crucially important to be clear on what level of information is required, and how often in needs to be collected at the outset of any monitoring programme. If the primary intention is to produce an assessment of the “overall health” of the protected area network then several questions need to be considered:

Firstly, what does “environmental health” look like and how can it be measured especially given ecological succession and possible competition between features? This is not simple as the multitude of habitats and species found on protected areas are likely to have varying levels of “health” with some doing well and some not at any point in time. Whilst it is tempting to suggest developing indicators of health, for example the presence of particular species/species assemblages or ecosystem processes that could be monitored as proxies for overall health, this would be complex and would require that the ecological relationship from these indicators to the rest of the ecosystem is clearly known. At a simple level this approach is probably used already to an extent, so for example, we might consider a river with breeding salmon Salmo salar, to be in a better state that a comparable one without. Similarly, a peatland with active peat formation is considered in a better state than one where peat is not forming.

It would be valuable to review whether the different approaches used to monitor various ecosystems and ecosystem services provide an insight into how methods could be adapted in a cost-effective way to assess health. Comparison of the various techniques used in the terrestrial and in the marine environment would be useful in this respect. Some approaches focus on the “state” of a system whilst others on “processes and pressures”. Being clear on the merits and cost-effectiveness of differing techniques would therefore be valuable in advance of launching any new approach.

Further thought could, however, be given to developing a series of indicators of “health” for protected areas by using a mix of the species assemblages, habitats and ecosystem processes as proxy for the overall health of the system. As a starting point it is important to clarify if the present system of legally identified “features” being monitored could act as indicators of wider health if the ecological relationships from the feature to the whole protected area was elaborated. Of course indicators do not have to be about the habitats, species and processes, they could also be structured around the activities impacting on protected areas and what we know about the pressures they exert. These could then also feed in to any overall evaluation and assessment.

3.2.2 Making an overall assessment

How can an overall assessment of the condition of protected areas be made? This implies that some level of cumulative assessment of individual protected areas would be undertaken. This is currently expressed as the number of features in a particular state such as “favourable”, “unfavourable” or “favourable recovering”. To extend the current system would require a new methodology to produce an overview assessment for a network of sites. Whilst difficult, this is an important piece of work, especially as the wider challenge is to be able to answer the question:

“What difference do protected areas make and is there an improvement in the health of these areas compared to other similar areas that are not part of the protected area network”?

Part of the answer in determining how to measure “change” might lie in agreeing the scale, frequency and nature of the assessment that is required as well as determining both the desired extent of detectable change and the statistical confidence of its detection[7] through power analysis (Legg & Nagy 2006). This will require a clear and agreed decision making process to ensure buy-in from the multitude of stakeholders involved. In determining the level and frequency of assessment and reporting required it is important to note that publishing the overall condition of protected areas across Scotland forms part of the Scottish Government’s suite of Performance Indicators and that there is a range of other international and legislative reporting commitments, for example, relating to the marine environment e.g. Marine (Scotland) Act and to OSPAR.

Ensuring that the monitoring of protected areas meets the requirements for such reporting will be an important factor in the design and implementation of any proposed changes to monitoring.

3.2.3 Developing new approaches

In considering any new system of monitoring it would be useful to clarify if any post-hoc analysis of the previous rounds of Site Condition Monitoring (SCM) has been undertaken to consider what level of ecological change has actually been detected, and what the impact of less frequent or different survey techniques would have been? SCM, has of course, produced an invaluable baseline of information that can act as a future reference source for protected areas across Scotland and the UK, albeit that this information needs to be set in the context of wider environmental changes across the country. In order to learn from the monitoring work undertaken over the past decade this post-hoc analysis could be undertaken as preparation for any change in methods in future.

Monitoring in future could perhaps take several forms and could be structured into a clear “risk based” approach, where broad scale survey detects any gross change in extent or quality and this is then supported by back up detailed survey to investigate significant change? Could the broad scale survey be undertaken in a different and more cost-effective way than at present? An example might be where the broad scale survey was undertaken via remote sensing and more detailed survey put in place where necessary to support this assessment? Alternatively, could the broad scale work on some sites at least be undertaken via a “citizen science” approach, (note this will probably not be possible for many offshore marine ecosystems given the scale and nature of these protected areas, however, such an approach has been effectively used in inshore areas).

For example, for protected areas that have a history of relative stability then:

- Establish baseline(s). At the simplest level assess the extent of the habitats and other features possibly via satellite imagery/citizen science etc. (Note again that this will probably not be possible for many offshore marine ecosystems. Note also that it could be argued that existing Site Condition Monitoring provides an effective baseline).

- If significant change (positive or negative) from the baseline is detected then undertake a rapid on the ground assessment of “quality” (based on indicators as mentioned above?)

- If significant change is detected or suspected (scientific judgement should be recognised as a key part of this decision making approach), then further detailed survey should be undertaken.

The results from this tiered and risk-based approach should be assessed in relation to any changes of similar features in the wider countryside so that any changes are set in this context, and linked to a mechanism to trigger management action to attempt to remedy any deterioration in quality based on the original management objectives for the protected area. There is an important question of scale in relation to the changes monitored, the factors causing them and the appropriate level of response. So for example, international action may be required to limit the effects of climate change as well as locally based action to tackle particular impacts or pressures.

Developing the use of citizen science in this way has an important benefit in engaging stakeholders in the monitoring and management of these areas. Various conservation projects have shown that people tend to value more those areas and projects that they feel part of (Roy at al 2012), hence getting wider involvement in monitoring protected areas could be beneficial overall.

As discussed previously, if a portfolio of protected areas holding similar features and facing similar threats is being monitored, then a risk based approach could lead to a sampling regime being developed that monitors a subset of areas in detail and does not monitor others unless significant change is detected in the focal areas. The focal areas would therefore act as proxy for the whole portfolio. Historically such approaches have, however, been criticised for being locally specific with limited value in extrapolation.

In summary, a risk-based, tiered approach to monitoring could be developed that incorporates a wider assessment of the overall protected area and that includes off-site contextual changes and other relevant factors. The assessment of “environmental health” is a complex area but developing a series of indicators may be useful. Assessment of ecosystem processes may be useful in some situations as a proxy for overall condition. The development of any new approach to monitoring, for example utilising a mix of professional survey and citizen science should be dovetailed with existing monitored activities to ensure comparability of the data and information collected.

3.3 Question 3

How do we ensure any financial investment in management on protected areas is optimal from a biodiversity perspective in a rapidly changing climate?

3.3.1 Agree the management aims and objectives

The onset of rapid climate change, (over the last 100 years we have witnessed changes associated with a 1C increase and over the next 30 years we will witness the changes associated with a further 1C), has meant that ecological change is now evident in many protected areas leading to a renewed focus on the overall effectiveness and purpose of such sites (Gaston et al. 2006; Johnston et al. 2013). The rate of such ecological change is likely to continue and increase. It is widely accepted that in order to allow species and habitats to survive there will need to be an increased focus on site-scale adaptation, through site management and threat reduction, so as to sustain biodiversity. This will help maintain populations within these areas and allow their spread elsewhere. For example, Ausden et al. (2014) explore in detail such challenges in managing and restoring wetlands in response to climate change.

The challenge is to minimise threats to these areas and to maximise their overall resilience, so that species and habitats can adapt at a pace that still allows their overall survival. This is a fundamental challenge that is at the core of the “biodiversity emergency”. It is important therefore to be clear what the management goals are for each protected area and how these relate to the wider, national, adaptation strategy for the species and habitats concerned.

Actions that would help achieve a cost-effective and focussed approach to management are:

- Agree clear targets for biodiversity on each protected area and across the portfolio of such areas, (and consequently test the diversity and hence resilience of sites at a ‘bigger-than-site’ scale).

- Consider further the purpose of the overall portfolio management with options being to manage for:

- Features as per the legal focus only, or legal features alongside:

- Whole of biodiversity or

- Whole of biodiversity, carbon sequestration and storage, or

- Whole of biodiversity, carbon sequestration and storage, climate change adaptation plus other economic interests.

These objectives may not be mutually exclusive, but it is important to be clear what the primary management and monitoring objectives are for any area.

Note also that as ideas and concepts relating to the monitoring and management regime are developed, current legislation still needs to be implemented – hence any change that might be suggested to the overall “purpose” of protected areas is likely to take some considerable time to achieve. The wider context is important here, however, and the transition to a net zero economy, in which land use plays a vital role is likely to become increasingly prominent Incremental change or at least change in parallel with continued delivery seems the most likely scenario as there will be multiple other legislative priorities for government over coming years, hence the chance of radical change is perhaps limited at this time, however, the lead up to 2030 may enhance the level of priority given to any change in future?

Perhaps the approach needs to be ‘what can be done within the flexibility afforded by current legislation’ (including considering its interpretation to date) and then – ‘what changes need to be made to legislation to take account of environmental change and the transition to, and maintenance of, a net zero economy’

3.3.2 Focus on resilience

A theme underpinning this think piece is to suggest that effort should be directed to maintain and enhance the resilience of protected areas in order to attempt to “smooth out” any change and give biodiversity time to adapt. This may or may not prove to be possible given the rate of change already being seen but it is an underpinning principal for action. The implication of this approach is that known threats should be the focus of activity, supported by professional judgement on the practicality of any management put in place.

Current legislation enables action to tackle existing threats to native biodiversity, for example over grazing in the uplands or damaging fishing activities in sensitive parts of the marine environment. Dealing with known threats may in fact be a relatively cost-effective way to help the resilience of these areas in the short-term, thereby contributing to wider ecosystem condition and to the “whole biodiversity” approach mentioned earlier.

It is important also to take account of the spatial aspects of individual protected areas and of the wider portfolio when considering the practicalities of management, boundary flexibilities and change, alongside adjacent ecosystems when determining how resilience might be enhanced. Dealing with resilience in this way, at the landscape and seascape scale will throw up new and complex challenges, hence it is suggested that a trial of such an approach is developed to test the practicalities involved in a range of possible scenarios covering a range of options on how resilience could be enhanced.

3.3.3 Strengthen the link from monitoring to management action

Building on the earlier discussion, it is clearly important to ensure that the results of monitoring inform management action. If possible, consider how management information will be used at the outset of any monitoring scheme as this can influence how the monitoring programme is framed. Alongside this, consider how decisions about management will actually made. Having such a process in place will avoid ad hoc management actions and will progressively systematise the use of monitoring to underpin management action.

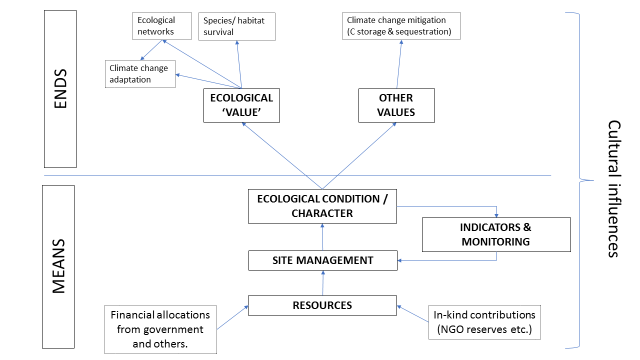

Figure 2 presents a conceptual framework showing the linkages from management actions (Means) to the ecological and other outcomes (Ends).

Assessing the effectiveness of adaptive management is a key part of the monitoring cycle, and ensuring that management is being effective when viewed against the original objectives for any area will inform future actions – hopefully in a cost-effective way. Indeed, such a process has been undertaken in several countries and at the global level with a range of methodologies available to do this (Leverington et al. 2010).

Such assessment should be undertaken at a variety of geographical scales and over a range of timescales. Developing a cost-effective, approach to assessment is important and could be one of the key areas to be trialled as part of taking forward a new approach to protected area management and monitoring.

It is important to note that whilst the focus of this discussion paper is on the situation in Scotland and on the work of NatureScot, a wide range of other government Departments, NGOs and private landowners and managers are involved in managing protected areas, hence it is important to consider how best to share the results of monitoring. Getting this communication and involvement right is crucial to getting “buy in” and real involvement from owners and other stakeholders. Similarly, given the presence of cross-border sites and the changing distribution of species with many moving northwards, alongside the need to coordinate and report at the UK level, then communication across the UK remains important.

3.3.4 Cost-effectiveness

There have been a number of assessments produced reviewing the value of protected areas at the global level (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2008) and investigating the cost-effectiveness of management actions. The publication of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005) highlighted the need to assess the value of ecosystems and of the management that maintains them in a broader way than simply monetary value. Clarifying the role and both economic and non-market values of ecosystem services is consequently a key part of assessing the value of protected areas at the global level (IPBES 2019). The developing science of Natural Capital and how to assess this in relation to protected areas within Scotland is, consequently, a theme worth exploring further.

Importantly, the costs of biodiversity loss overall will be evaluated within the Review of the Economics of Biodiversity: “the Dasgputa Review” that was commissioned by the UK Government (UK Government 2019). This incorporated the multiple values of ecosystem functions into economic incentives that could result in better ecological, economic and social outcomes, if set at a level that conservation of ecosystems can compete with the production in agriculture and forestry for example. Clearly, this analysis is highly relevant here and worthy of further exploration in terms of the value of protected areas and the cost of their management across Scotland.

Put simply, this is an area in need of much further exploration and evaluation. Indeed, it is worth considering a “Natural Capital and management cost audit” of protected areas, where even a small scale trial would help to reveal what is there, how to value it, and the cost of maintaining it, taking account of the wider use of the land and sea.

3.3.5 A new phase of management?

Protected areas form the core of nature conservation action around the world with a huge variety of legislative and cultural frameworks governing how protection works in each case. There have always been challenges to address in the management of these areas but with the onset of rapid climate change in particular, the level of urgency to reassess their purpose and to explore multiple management objectives has been significantly heightened. For example, the multi-use of protected areas in the context of climate change in North America.

It would be useful to consider a similar approach here. The decade to 2030 is likely to be a period of real and perhaps unprecedented opportunity in terms of global understanding of the biodiversity crisis (building on the work of IPBES). The next decade will be critical to find and implement solutions to the interrelated emergencies on biodiversity loss and climate change.

When considering where protected areas fit in future in terms of multiple management objectives and how to value their management, then clearly further work is required, but the examples of site selection and management in Scotland can help inform the global debate on these topics. It is important now to examine in detail the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, that will, in time provide a global framework for action; and to consider also how to help shape the UK’s input to the Convention on Biodiversity global conference scheduled for 2021. Whilst these processes may seem a bit distant, they do provide an opportunity to quality check what is being done in Scotland compared to other countries.

Indeed, it is worth considering the merits of organising an international event to explore further the issues discussed in this paper. They are common across many countries and it seems likely that others would be interested in joining such an event.

In summary, historically protected areas have formed a key part of the effort to conserve biodiversity and are central to the requirements of CBD. With the developing impact of climate change it is timely to consider whether and how multi-faceted management objectives could be agreed for such sites. Maintaining the resilience of these areas is a priority and tackling known threats may be a cost-effective way of doing this. It would be useful to further evaluate the Natural Capital resource held on protected areas alongside an audit of management effectiveness. Note that there is already a huge global literature on assessing management effectiveness on protected areas.

4. Discussion and key questions for the Webinar

This think piece has addressed three key questions, summarised as;

- How to make use of legislation?

- Are we measuring the right things?

- How to optimise spending?

Given the twin emergencies of global biodiversity loss and increasing climate change linked to the current financial recession, alongside the Covid epidemic and the developing Green recovery, then these questions are timely and well-focussed. As biodiversity disappears from many wider areas then the need for nature conservation has never been greater. Protected areas are vital in terms of maintaining biodiversity, but also in terms our collective wellbeing – something brought to the fore in the recent Covid lockdown period.

4.1. Addressing the Key Questions

The answers to the three key questions being posed are necessarily complex and somewhat fragmented at this stage, however some common themes emerge.

Firstly, it is important to be clear about the purpose of the protected area portfolio and from this to be clear about the management aims of every site – what is it trying to conserve.

Moves to protect “whole biodiversity” and ecosystem services are undoubtedly right but it might be complex to shift from the current legally defined approach. Is such a change really a medium-term objective?

Climate change and other pressures are now causing rapid change, hence the need to consider how protected area boundaries are set and modified over time. This activity needs to sit within a context-setting national adaptation strategy.

Taking a landscape approach that better integrates the management of protected areas with that of surrounding countryside, including restoration where feasible, will become even more important if current trends of biodiversity loss continue. Developing scenarios for managing sites in a changing environment could provide valuable context and help focus the need to develop true networks across the landscape and seascape in future. Whilst the focus of this think piece is protected area management and monitoring, it is clear also that we have to get better at integrating such areas in to the wider environment, whether that be as nodes for building ecological networks or as areas ‘leading by example’ in terms of management for a nature rich future.

4.2. Monitoring Requirements

Monitoring methods will need to adapt to be more efficient given the pressure on resources overall. Developing a risk-based approach alongside greater use of new technologies with the use of citizen science supported by the essential input and judgement of professional ecologists could be explored further in combination rather than as separate lines of approach. Similarly, further work on the role of indicators as proxy of overall condition would be valuable.

It is important to consider how ready for change the wider scientific monitoring community is. Understanding this may well be significant, especially if new systems, perhaps using citizen science, for example, are to be introduced to help measure the overall effectiveness of management on protected areas. Optimistically, could a new partnership with a range of non-government organisations and with the managers of land and sea be developed, working with the Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum (SBIF), where the efforts on data and information collection are shared with the results being pooled – along the lines of existing volunteer based schemes to monitor a range of species? Noting of course that good progress has already been made here in building partnerships but could more be done to formalise this?

The link from monitoring result to management is key and could be strengthened with a clear decision-making process spanning all the stakeholders involved. Indeed, stakeholder involvement is key to future monitoring and management, and maintaining effective communication with the various stakeholder groups involved should be built into any forward plan of action.

It is important to further investigate how multiple management objectives (to manage for carbon, biodiversity and existing economic interests, for example) can be aligned and any trade-offs in land management agreed. Management should be focussed on maintaining resilience on individual areas and across the portfolio, meaning in particular tackling known threats now – time is short.

The collation and storage of data and information derived from monitoring on protected areas is a valuable baseline resource and as such consideration could be given to how it is accessed and used by the wide variety of stakeholders. The feasibility of initiatives such as developing the SBIF, and enhancing existing or creating new Record Centres could be explored further as any new approach to monitoring is introduced.

Many of the issues discussed above could be further explored via a practical trial that examined a selection of protected areas including both terrestrial and marine areas in terms of their management objectives; the ecological and geological resources they hold, options for monitoring and how to measure the cost-effectiveness of management. This could also pilot a national or regional- scale adaptation strategy for species or habitats on protected areas known to be at high risk from climate change. This would provide context for adaptation through management at individual sites and could see Scotland take a leading role in the practical application of such an approach.

The head points for such a trial are presented in Annex 1.

Finally, the year 2021 will hopefully be a key year for biodiversity and climate change and the climate change conference scheduled to take place in Glasgow in late 2021, along with the CBD Conference also scheduled for 2021 provide real opportunities to influence the wider agenda on protected areas and to learn from other countries.

4.3. Key questions for the webinar to discuss:

1. Does the range of issues presented in Section 2 of this paper effectively summarise the situation and are the key risks identified?

2. Are we currently maximising the use of current legislation, and if not what enhancements can be made to include the protection of a wider suite of biodiversity interest?

3. What do we consider to be favourable condition or ecosystem health? From this, developing clarity on the purpose of protected areas then leads on to what we monitor and how we manage.

4. Is the focus on maintaining the resilience of protected areas correct and how should this be achieved when delivering multiple management objectives?

5. Would it be useful to trial the combination of monitoring methods outlined here, and if so, how should this be done in practice to encompass terrestrial and marine sites?

6. What role could monitoring ecosystem processes and a Natural Capital assessment make in informing the management of protected areas?

7. Are enhancements needed to the current protected area management assessment methodologies – especially in light of climate change and other impacts?

Footnotes

[1] Whilst the Johnston et al. study involved predictive modelling, a recent continental-scale analysis of non-breeding waterbird distribution demonstrated that such redistribution within a protected area network is currently happening. Smew are abandoning SPAs in central and southern Europe and occupying SPAs classified for other species in northern Europe (Pavón-Jordán et al. 2015).

[2] Such an option could include forms of ‘rewilding’ where natural processes are allowed to dominate.

[3] Including non-intervention, should that be an option

[4] The third SPA review (Stroud et al. 2016) reported that 72% of all 1,516 interest features across the network were monitored through UK scale ‘citizen science’ schemes

[5] For example, Article 3 of the Birds Directive and Article 10 of the Habitats Directive

[6] in particular, in relation to the potential for restoration of surrounding areas, thus enhancing connectivity

[7] e.g. 95% certainty of detecting a 10% change in abundance

5. References

Ausden, M., Hirons, G., Lock, L. & White, G. (2014). Managing and re-creating wetlands in Britain for potential colonists. British Birds 107(3): 726-755.

EC Directive on the conservation of wild birds

EC Directive on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora

EC Marine Strategy Framework Directive

European Environment Agency 2020. State of nature in the EU. Results from reporting under the nature directives 2013-2018. EEA, Copenhagen. 142 pp.

Fauchald, O.K., Gulbrandsen, L.H. & Zachrisson, A. (2014). Internationalization of protected areas in Norway and Sweden: examining pathways of influence in similar countries. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 10(3): 240-252. DOI: 10.1080/21513732.2014.938122

Gaston, K.J., Charman, K., Jackson, S.F., Armsworth, P.R., Bonn, A., Briers, R.A., Callaghan, C.S.Q., Catchpole, R., Hopkins, J., Kunin, W.E., Latham, J., Stoneman, R., Stroud, D.A. & Tratt, R. (2006). The ecological effectiveness of protected areas: the United Kingdom. Biological Conservation 132: 76-87.

Helm, D. (2015). Natural Capital - Valuing Our Planet. Yale University Press; 277 pp. ISBN 978-0-300-21098-9.

Hodgson J.C., Mott, R., Baylis, S,M., Pham, T.T., Wotherspoon, S., Kilpatrick, A.D., Segaran, R.R., Reid, I., Terauds, A., Koh, L.P. (2018). Drones count wildlife more accurately and precisely than humans. Pp 1160-1167, in: Methods in Ecology and Evolution. John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of British Ecological Society.

IPBES (2019). The global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Summary for policymakers. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany. 60 pp..

Johnston, A., Ausden, M., Dodd, A.M., Bradbury, R.B., Chamberlain, D.E., Jiguet, F., Thomas, C.D., Cook, A.S.C.P., Newson, S.E., Ockendon, N., Rehfisch, M.M., Roos, S., Thaxter, C., Brown, A., Crick, H.Q.P., Douse, A., McCall, R.A., Pontier, H., Stroud, D.A., Cadiou, B., Crowe, O., Deceuninck, B., Hornman, M. & Pearce-Higgins, J.W. (2013). Observed and predicted effects of climate change on species abundance in protected areas. Nature Climate Change 3: 1055-1061.

Legg, C.J. & Nagy, L. (2006). Why most conservation monitoring is, but need not be, a waste of time. Journal of Environmental Management 78(2): 194-199.

Leverington, F., Costa, K.L., Pavese, H. et al. 2010. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environmental Management 46: 685–698.

Maitland, PS., Boon, P.J. & McLusky, D.S. (1994). The Freshwaters of Scotland. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. 639 pp.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC.

NatureScot (2020). Peatland Condition Assessment. Accessed October 2020.

Pavón-Jordán, D., Fox, A.D., Clausen, P., Dagys, M., Deceuninck, D., Devos, K., Hearn, R.D., Holt, C.A., Hornman, M., Keller, V., Langendoen, T., Ławicki, L., Lorentsen, S.H., Luigujõe, L., Meissner, W., Musil, P., Nilsson, L., Paquet, J.Y., Stipniece, A., Stroud, D.A., Wahl, J., Zenatello, M. & Lehikoinen, A. (2015). Climate-driven changes in winter waterbird abundances in relation to EU protected areas. Diversity and Distributions 21: 571-582.

Roy, H.E., Pocock, M.J.O., Preston, C.D., Roy, D.B., Savage, J., Tweddle, J.C. & Robinson, L.D. (2012). Understanding Citizen Science & Environmental Monitoring. Final Report on behalf of UK-EOF. NERC Centre for Ecology & Hydrology and Natural History Museum.

Ruppert K.M., Kline, R.J. & Rahman, M.S. (2019). Past, present, and future perspectives of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: a systematic review in methods, monitoring, and applications of global eDNA. Global Ecology and Conservation 17: e00547.

Scottish Government – (accessed October 2020). Environmental health indicators.

Scottish Government (2016). Getting the best from our land: a land use strategy For Scotland 2016 – 2021.

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2008). Protected Areas in Today’s World: Their Values and Benefits for the Welfare of the Planet. Montreal, Technical Series 36: i-vii + 96 pp.

SEPA Aquatic monitoring strategy. Accessed October 2020.

Stroud, D.A., Bainbridge, I.P., Maddock, A., Anthony, S., Baker, H., Buxton, N., Chambers, D., Enlander, I., Hearn, R.D., Jennings, K.R, Mavor, R., Whitehead, S. & Wilson, J.D. - on behalf of the UK SPA & Ramsar Scientific Working Group (eds.) (2016). The status of UK SPAs in the 2000s: the third network review. 1,108 pp. JNCC, Peterborough.

UK Government (2019). The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review.

Willis, K.S. (2015). Remote sensing change detection for ecological monitoring in United States protected areas. Biological Conservation 182: 233-242.

Annex 1. Towards a pilot of some key approaches to management and monitoring

The ideas discussed in this short paper could, if taken together form the basis of a new, innovative and possibly more cost-effective way to undertake the management and monitoring on protected areas. They would, however, represent a significant change and that change would not be risk free. In order to test drive some of the approaches it is suggested that a trial is undertaken at a regional level to help evaluate the practicalities involved. The following outlines the key aspects that could be piloted in this way.

In essence the trial would take a risk based approach at the regional portfolio level including marine and terrestrial protected areas, and would quantify biodiversity on protected areas; evaluate the use of indicators as a proxy for overall biodiversity, and test how to develop multi- output management goals (“biodiversity plus”). It would include a test of monitoring methodologies using remote sensing in combination with professional survey, and citizen science/owner and manager involvement. The trial would:

1. Biodiversity assessment

Take stock of current portfolio with a Natural Capital audit of a selection of sites in terms of their multi-use value. Key questions include;

- What biodiversity is actually held on site (s) in addition to the legally defined features?

- Do the existing legally defined features act as indicators or not?

- How much carbon is stored and being sequestered – is it worth managing the site for carbon in addition to biodiversity?

- How to assess other value including ecosystem processes – flood prevention – food – aesthetic value etc.

In essence this would mean undertaking an ecosystem assessment to determine the value of changing the focus from “features” to the whole of biodiversity or to “ecosystems and ecosystem processes”.

2. Management goals

Test defining multiple management goals in relation to: biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services – what would be protected and how would this be monitored? Specifically choose a selection of upland, lowland, coastal and marine sites and undertake as a practical “real world trial “taking account of constraints and opportunities as well as the costs and benefits of differing approaches. Importantly, the trial could include an assessment of the effectiveness of management on particular protected areas and across a wider portfolio of sites.

3. Climate change adaptation

Pilot a national or regional-scale adaptation strategy for species or habitats on protected areas known to be at high risk from climate change. This would provide context for adaptation through management at individual sites and across the wider portfolio of protected areas. Such a trial could see Scotland take a leading role in the practical application of such an approach.

4. Develop a Regional trial of monitoring methods.

Trial using satellite, aerial, professional survey and citizen science in combination. Consider also data collation, access and feedback to inform protected area management as well as the need to report at the Scottish, UK and international levels.

Origin of the think piece and overall purpose

This paper considers issues identified by the Board of NatureScot who undertook a Deep Dive of their work on Protected Areas, recognising that there are significant challenges ahead in the monitoring and management of these areas. The Board commissioned their Protected Areas Committee (PAC), a sub-group of the Board, to consider:

The legal basis

Protected areas have long been a cornerstone of nature conservation practice, with a raft of legislation at a range of scales, including local, Scottish, UK, EU, European and global. The legal obligations are similarly varied, with protection in many cases being delivered through planning constraints.

This has resulted in a variety of “types” of protected area depending on their legislative origin and their particular features of importance. For example, within Scotland at present, a protected area could be an SSSI, (Scottish/UK legislation), National Nature Reserve (Scotland/UK legislation), Special Protection Area (SPA - EU Birds Directive), Special Area of Conservation (EU Habitats Directive) and a Ramsar Site (Ramsar Convention – Global legislation). It could also sit within a landscape designated as a National Scenic Area or National Park. Importantly, over recent years the development of protected areas in the marine environment has gathered pace with several important large areas now designated as Marine Protected Areas, (Scottish/UK/EU legislation), hence consideration of the issues surrounding protected areas in this paper relates to both marine and the terrestrial environments.

Disclaimer: Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) has changed its name to NatureScot as of the 24th August 2020.

At the time of publishing, this document may still refer to Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) and include the original branding. It may also contain broken links to the old domain.

If you have any issues accessing this document please contact us via our feedback form.