Understanding the Indirect Drivers of Biodiversity Loss in Scotland - A Summary

The Background

Global biodiversity is in unprecedented decline, Scotland’s biodiversity is also declining and Scotland ranks in the lowest 15 % of countries in terms of the intactness of its biodiversity. These declines have been shown to be the result of land/sea use change, resource extraction, pollution, invasive alien species and climate change – the so-called “direct drivers” of biodiversity loss.

What do we mean by “Indirect Drivers” and their impact on biodiversity?

The direct drivers are symptoms and indicators of overconsumption linked to our current and past unsustainable use of resources, but it is the underlying “indirect drivers” that need to be addressed to prevent further biodiversity loss; the same ones also drive climate change as highlighted in the recent IPCC report. In effect, to stop further loss we need to address the societal values and behaviours that have led to Scotland substantially exceeding its share of our planetary boundaries (the safe operating space for humanity that allows future generations to thrive).

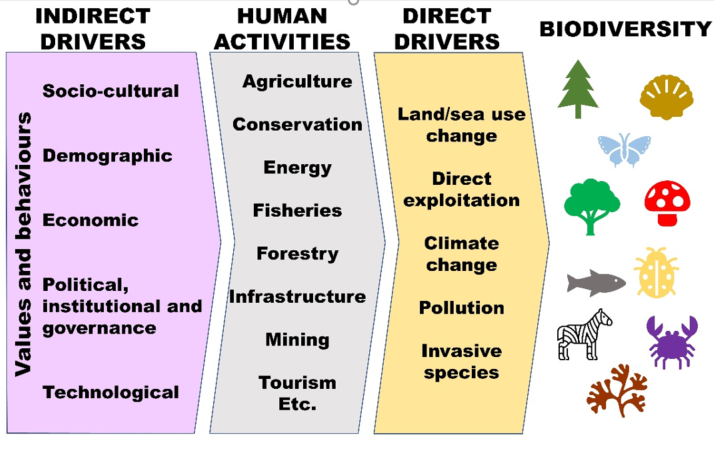

Infographic illustrating how a list of indirect drivers (values and behaviour across socio-cultural, demographic, economic, political, institutional and governance, and technological) feed into human activities across agriculture, conservation, energy, fisheries, forestry, infrastructure, mining, and tourism etc. and these in turn feed into a list of the direct drivers (land/sea use change, direct exploitation, climate change, pollution, and invasive species). All ultimately impacting on biodiversity.

The Report

The full report uses the 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services as the framework to help understand how the indirect drivers are affecting global and Scottish biodiversity and start to identify possible actions that could be taken to prevent further loss. The findings are summarised below under the five key “indirect drivers” and will be familiar to readers of The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review.

1. Socio-cultural drivers

Scotland is a comparatively wealthy country (mid-ranked within the OECD) with high levels of consumption and with only a small proportion of the population very interested/concerned about biodiversity. To prevent ongoing national and global impacts on biodiversity we should frame decision making in terms of how it will affect future generations, build nature connection and pro-environmental behaviours, as well as shifting to measuring wellbeing rather than consumption. The media has a critical role to play in informing debate based on sound evidence.

2. Demographic drivers

Projections for Scotland’s population are relatively stable, but there will be continued urban growth and decline in remote rural areas. Development needs to be carefully planned and managed to minimise direct impacts on biodiversity as well as indirect impacts such as building on farmland which can result in food production, and its biodiversity impacts, shifting elsewhere. To deliver change there is also a need to build biodiversity related skills in the environmental and farming sectors as well as to foster nature connections in children to empower them for future decision making.

3. Economic drivers

Global trade is linked to 30% of threatened species, and the UK is the 5th ranked country in terms of exporting its biodiversity impact. Supply chains should shift to more sustainable production supported by improved certification schemes and moving to a zero-waste society. Within Scotland, regulations and incentives need reform to shift agriculture, forestry and fishing practices to boost nature restoration whilst preventing perverse outcomes, for example in the emerging carbon market. Decision making by all actors has to move away from a narrow focus on economic performance and towards adopting indicators of sustainability, wellbeing and equity to prevent further biodiversity loss.

4. Political, institutional and governance drivers

Biodiversity has to be mainstreamed and integrated across all sectors of the policy arena to stop further loss. Incentives for fossil fuel use need to be removed and any continued use made more efficient through incentivising public over private transport. Further strict protection is necessary for protected areas. Outside these areas, shifting to results-based payments for land management, and including biodiversity outcomes in resource management such as setting fishing quotas, all have a role to play in halting biodiversity loss. The necessary societal changes may have different impacts across the population, so a concentration on equity will contribute to a Just Transition. Improving democratic structures will facilitate deliberation on complex, interconnected environmental and social issues allowing for more inclusive decision making and reducing the influence of vested interests

5. Technological drivers

Technological innovations have helped to reduce pollution and allowed us to exploit renewable energy and are now being harnessed to build a circular economy. However, mechanisms need to be strengthened to support the adoption of technologies that improve sustainability and reverse biodiversity loss. For instance, using biomass for energy has to be assessed in terms of it competing for land directly with biodiversity or indirectly by shifting food production elsewhere. Interlinking local knowledge with technical and scientific knowledge will better protect and restore biodiversity and other resources.

Restoration

Successfully addressing the indirect, and hence direct, drivers of biodiversity loss will stop the biodiversity crisis worsening. However, only a proportion of species and habitats will regenerate on their own; the others will require substantial restoration efforts. This may entail difficult decisions as to which habitats to prioritise and whether priority should be given to improving local biodiversity or halting global biodiversity loss through concentrating on carbon sequestration or onshoring food and timber production. Ultimately, decision makers have to work through the local, national and global consequences of their decisions in how they will impact biodiversity and to decide where to make trade-offs between continued production and restoration.

The policy landscape

The implementation of a range of Scottish policies has started to address these indirect drivers including implementing the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals through the National Performance Framework, joining the Wellbeing Economy Alliance, setting up the Just Transition Commission and the publication of both the National Strategy for Economic Transformation and the Environment Strategy. Anticipated legislation which would consider the indirect drivers includes the forthcoming Natural Environment Bill, and Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill. There is also policy development around the blue economy strategy, and land use, including agricultural support, deer and grouse moor management. However, combatting the indirect drivers will be a long road. Change will need to be driven by individuals, communities, civic society, business, and local, Scottish and UK governments, as well as through international institutions, with each set of actors having more or less influence on each set of drivers.

Proactive or reactive changes

The Stern review on the Economics of Climate Change clearly showed that the costs of inaction on climate change substantially outweigh the costs of action; the biodiversity crisis can be seen in the same way. We need to align Scotland’s consumption as much as possible with its ability to produce across sectors such as farming, forestry and fishing. Enabling the societal changes that will return humanity to living within its planetary boundaries will need national and international consensus, but as Scotland has been at the forefront of setting targets for emissions reduction there is the potential to play a leading role in tackling biodiversity loss on the global stage.

Authors: Robin J Pakeman, Antonia Eastwood, Dominic Duckett, Kerry A Waylen and Jon Hopkins, The James Hutton Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH.

Contact: [email protected]

Read the full NatureScot Research Report 1309 - Understanding the Indirect Drivers of Biodiversity Loss in Scotland.