Renfrewshire Council - Deer Management Statement

Tom Edwards, December 2022

1. Purpose

The purpose of this statement is to inform Renfrewshire Council’s production of a Deer Management Statement that will establish a framework for the Council to fully consider its deer management responsibilities. Contextual information is also provided summarising: the current national law and policy on deer management; available information about deer in Renfrewshire; and the responsibilities that the Council has to manage deer under current legislation both as a landowner/manager, and as a public body.

2. Background

2.1 What is the law on deer management?

The key piece of legislation on deer management is the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996 [the Act]. The Act has been amended several times, most significantly in 2011 and 2016.[1] The Act sets closed seasons during which deer may not be taken and minimum requirements for firearms for killing deer. It also prohibits certain methods of killing or taking deer to protect their welfare. The Act established the Deer Commission for Scotland as an NDPB to advise Government on deer management. In 2011 the functions of the Deer Commission for Scotland under the Act were transferred to NatureScot[2]. The Act gives NatureScot powers to secure deer management by: requiring landowners to produce a deer management plan; negotiating a control agreement with landowners to implement specific deer management measures; and, where a control agreement cannot be negotiated, to apply to Scottish Ministers to make a control scheme requiring specific deer management measures. These powers are available under the Act where deer and/or current deer management (or lack of) are causing (or are likely to cause) damage to woodland, agriculture, deer welfare or the natural heritage; damage to the public interest; injury to livestock; or where deer are a danger or potential danger to public safety e.g. because of deer vehicle collisions or the risk of deer vehicle collisions (DVCs).

An amendment to the Act in 2011 required NatureScot to produce a Code of Practice on Deer Management, to provide practical guidance on sustainable deer management, and to give examples of circumstances in which NatureScot would use its powers under the Act.

The Code of Practice on Deer Management [the Deer Code] was approved by the Scottish Parliament on the 14 December 2011. It is not an offence to breach the Code, however, compliance with it is a consideration for NatureScot in deciding whether to use powers under the Act (Scottish Natural Heritage 2011).

2.2 What is the Scottish Government and NatureScot’s policy on deer management?

The Scottish Government and NatureScot’s key policy on deer management is ‘Wild Deer a National Approach’ [WDNA]. This strategy document was first published in 2008, and then reviewed and revised in 2014. The revised document was accompanied by an Action Plan setting out actions to be implemented between 2015 and 2020. WDNA sets the following vision for deer management in Scotland to be achieved by 2030:

“There will be widespread understanding and achievement of sustainable deer management.

- Deer will be valued as part of Scotland’s natural heritage, in balance with their habitats and will contribute to a high quality, robust and adaptable environment;

- Deer will be a resource for diverse sustainable economic development with adverse impacts on other land being minimised;

- Deer management will promote social well-being through enjoyment of the outdoors and healthy lifestyles.

Wild deer will be managed in an inclusive way with knowledge used to underpin all decisions.” (Scottish Government 2015)

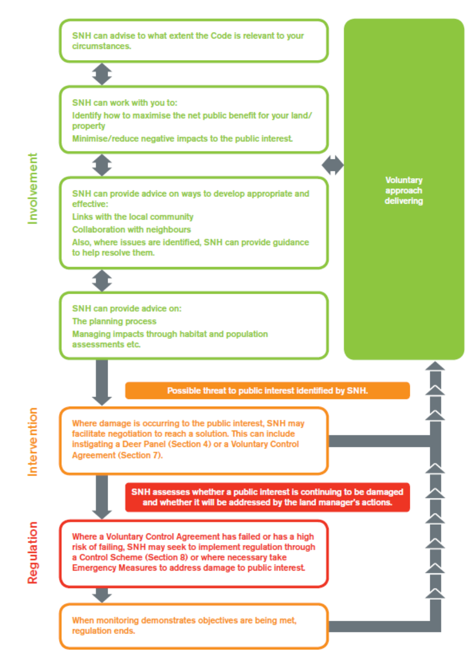

NatureScot’s policy is to secure sustainable deer management through a voluntary approach which seeks a partnership with deer managers and encourages effective collaboration between neighbours. NatureScot will only seek to use its powers under the 1996 Act where this approach has been attempted and exhausted. NatureScot’s approach to deer management is summarised in a flow diagram in Chapter 5 of the Deer Code which has been reproduced in Appendix 3 of this document.

WDNA highlights other relevant Scottish Government policies and objectives which achieving deer management can make a contribution towards implementing and meeting. These include in particular the policies and measures the Scottish Government is committed to tackle the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. These measures include:

- Climate Change Targets to reduce Scotland's emissions of all greenhouse gases to net-zero by 2045[3]

- Scotland’s Climate Change Plan, which sets out the measures which need to be implement to achieve net-zero. The measures include increasing woodland creation from 12,000 hectares in 2020-21 to 18,000 hectares per year from 2024-25 (Scottish Government 2020a).

- The Scottish Government’s Biodiversity Strategy, which set a challenge of restoring 15% of degraded ecosystems. The Scottish Government will publish a new biodiversity strategy in 2022 (NatureScot 2020a). The Scottish Government consultation paper on a revised strategy proposed two objectives of reversing biodiversity loss by 2030; and restoring and regenerating biodiversity by 2045. Among the outcomes proposed for 2030 were that there would be large-scale regeneration of woodland, achieved by reducing deer grazing and browsing impacts; and that the number of deer and their impacts is reduced to enable peatland restoration, natural regeneration of woodlands and increased structural diversity in the uplands (Scottish Government 2022a).

2.3 Recent and future policy developments

2.3.1 Lowland Deer Panel

NatureScot convened a Lowland Deer Panel in January 2018 to answer five key questions on deer management in the Lowlands. The panel was remitted to make recommendations within the scope of the existing legislative framework. The panel reported in February 2019, its main recommendations were that:

- NatureScot should work more extensively with Local Authorities to ensure they were aware of their responsibilities under the Deer Code

- Collaborative deer management in the lowlands should continue, with the structures to deliver it varying according to the species present, with collaboration over larger areas where herding species (red, sika, fallow) are present, and more locally where only roe deer are present (Lowland Deer Panel 2019)

2.3.2 Deer Working Group

The Scottish Government appointed an independent Deer Working Group in October 2017 to recommend changes to ensure effective deer management in Scotland that safeguards public interests and promotes the sustainable management of wild deer.

The Deer Working Group (2020) submitted its final report in December 2019. The >350 page document provides a comprehensive review of all aspects of deer management in Scotland, and made 99 recommendations for changes to law and policy.

The Group considered the specificities of managing deer in the urban environment, e.g. the fact that there are a large number of property owners, with little or no experience or interest in managing deer, and also the challenge of managing deer using high-velocity rifles in densely populated areas. The Group considered whether this warranted a different approach, where local authorities would become the deer authority in certain designated areas, with a range of regulatory powers e.g. to licence deer control. It stopped short of recommending this.

The Group made two recommendations which specifically referred to local authorities. These were that NatureScot should work to develop deer management at a local authority level as an intermediate level between the national and local levels (recommendation 91); and that NatureScot should appoint a panel of public sector representatives for each local authority area to advise on deer management recommendation 94). The Group suggested that these panels should include representatives of Scottish Forestry; Forestry and Land Scotland; the Scottish Government Rural Payments and Inspections Directorate; and Police Scotland; as well as representatives to cover local authority responsibilities for roads, venison dealer licensing and planning.

The Scottish Government (2021a) published its response to the Deer Working Group’s report in March 2021. The Government accepted almost all of the recommendations the Group made. It said it will take forward the recommendations for legislative change in the current Parliament (i.e. before 2026), and that there will be public consultation before any proposals for legislation are introduced to the Scottish Parliament. The Government said that while legislative proposals are being developed, it will implement the Group’s recommendations which do not involve legislative change, prioritising those which support the achievement of climate and biodiversity targets. On the recommendations referred to above, the Government has accepted recommendation 91, and that NatureScot will develop proposals for Local Authorities (or a similar alternative such as Regional Land Use Partnerships) as an intermediate level for deer management. The Government has not accepted recommendation 94 on the establishment of local authority panels. It has said it will consider this recommendation further once it has developed its policy on an intermediate level of deer management through the implementation of recommendation 91.

A recent Parliamentary Question asked the Scottish Government for an update on plans to introduce legislation on deer management. The Scottish Government said in response that it was progressing with implementing the recommendations of the Deer Working Group. For the recommendations which require legislative change, the Government reiterated its commitment to introduce legislation in the current Parliamentary session, that it would provide more detail on the timing in due course, and that it would consult on its legislative proposals (Scottish Parliament 2022).

2.4 What deer are present in Renfrewshire?

Available information suggests that the main deer species regularly present in Renfrewshire is the roe deer. Roe deer are one of Scotland’s two native species of deer, the other being the red deer. Two other introduced species of deer, sika and fallow, are present in Scotland. A fifth species, also introduced, the Muntjac, is expanding its range Northwards in England, but is not currently thought to be established in Scotland.

The National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Atlas of Scotland has 276 records of roe deer in Renfrewshire since 1990. The records are well spread, with some concentrations in a corridor running Southwest from Paisley towards Lochwinnoch. These concentrations are likely an artefact of recorder effort, rather than reflective of actual density and distribution. The NBN Atlas also has one record of a Red deer from the area around Lochwinnoch from 2019.

The British Deer Society carries out periodical deer distribution surveys. The most recent survey was in 2016. The results report presence or absence of deer within 10km grid squares (hectads). The results of the 2016 deer survey showed that roe deer were present in all of the 10km squares within Renfrewshire (British Deer Society 2016[4]). The survey reconfirmed[5] Red deer in grid square NS47, which is partly within Renfrewshire, and also showed that Red deer had been recorded in previous surveys (either 2007 or 2011) in NS26 and NS37, also partly in Renfrewshire.[6] Previous BDS surveys have recorded Fallow deer in grid squares NS35, a small part of which is in Renfrewshire, and NS36, which is mainly in Renfrewshire. Sika deer were not recorded in Renfrewshire.

There is very limited information available on numbers or densities of deer in Renfrewshire, or in lowland Scotland in general. Nature Scot has carried out two deer counts in Renfrewshire, at Gleniffer Braes in January 2012, and a count focussed on greenspaces in the urban and peri urban areas of Bishopton, Erskine and Renfrew in December 2022.[7] The 2012 count was done to inform the response to public safety concerns over deer vehicle collision risk on roads surrounding Gleniffer Braes Country Park. A total of 34 roe deer were counted in an area of around 4km2. The 2022 count was done as a snapshot of deer presence/absence in an area around Renfrew town, where the presence of deer had been identified by local community members. A total of 23 roe deer were counted, most of which were on farmland on the urban fringe, rather than within urban or peri urban areas. This is not a high number given the area and the habitats counted.

Due to the nature of the terrain, often being flat with limited vantage points and the fact that deer spend much of their time in woodland and other concealing habitat, it is not feasible to try to establish the size of roe deer populations in the lowlands by direct counting. Instead, the approach of NatureScot and other deer managers is to manage deer according to the impacts they are having, e.g. by monitoring the impacts of deer browsing on trees, or the rate and locations of deer vehicle collisions. Where impacts are at an unacceptable level, further management measures are put in place to attempt to reduce impacts, with ongoing monitoring to assess whether management is having the desired effect.

2.5 Deer habitat in Renfrewshire

Deer are naturally woodland animals. Red deer in parts of Scotland have adapted to living on the open hill. In other areas, Red deer live in woodland. The ranges of the other three species present in Scotland, Roe; Fallow; and Sika are closely linked to woodland. Deer use woodland or dense scrub to lie up during the day or for refuge when disturbed, moving to open ground to feed at dawn and dusk. The increase in woodland cover in Scotland over the last century has allowed deer of all species to increase their range and numbers.

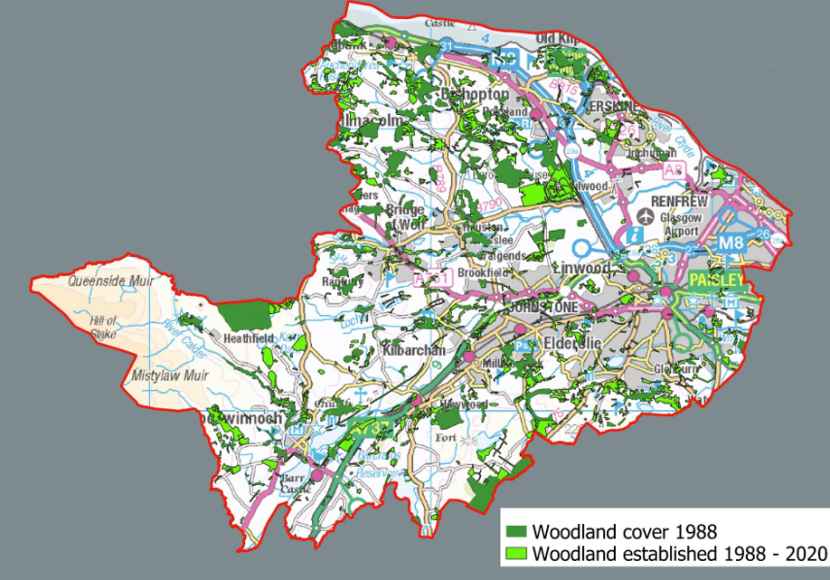

Woodland cover has more than doubled in Renfrewshire from 1988 - 2020[8], as is shown in the table below.

|

Year |

Woodland area, all types (hectares) |

% of Renfrewshire Council area |

|---|---|---|

|

1988 |

1,563 |

6% |

|

2020 |

3,387 |

13% |

Sources: Land Cover Scotland 1988 and National Forest Inventory for Scotland 2020

Woodland cover in Renfrewshire as a proportion of its area remains below the national level: 13% for Renfrewshire compared to 19% for Scotland[9]. Nonetheless, the increase in woodland cover and the development of woodland habitat corridors, e.g. along former railway lines; cycle networks, have allowed deer to expand their range into greenspace throughout the urban areas of Renfrewshire.

As well as changes in woodland cover, changes in farming practices also have an effect on deer habitat, e.g. a decline in livestock farming can improve the suitability of open habitats for deer grazing. Change in farming was investigated by analysing information from the agricultural census on Renfrewshire and the agricultural “parishes” within it[10]. Information was analysed on areas of crops and grass, and the type and number of livestock kept, from agricultural census returns for 1990 and 2020.

The main changes have been a reduction in the area of rough grazing; an increase in improved grassland and woodland on farms; and a reduction in numbers of both sheep and cattle. The number of sheep kept in Renfrewshire declined by nearly 34%, from 29,136 to 19,154. The proportional decline in sheep numbers is particularly pronounced in the Kilbarchan parish in percentage terms, declining 81%, and in terms of numbers in the Lochwinnoch parish, declining by over 5,000 head. The number of cattle kept in Renfrewshire declined by 40% from 18,134 to 10,899 over this same period.

The decline in sheep numbers is in line with the national trend, with a 32% decline in the number of sheep kept in Scotland from 1990 to 2020. For cattle, the reduction is more than double the level of decline seen nationally (19% reduction from 1990 to 2020). The reduction in livestock numbers is likely to have increased and improved the area of habitat available to deer in Renfrewshire.

2.5.1 Deer habitats on land owned or managed by Renfrewshire Council

Renfrewshire Council owns and manages over 700 hectares of parks and greenspace. Council owned and managed land includes c.480 hectares of Countrypark and 150 hectares of woodland.[11] The Council also owns and manages two Local Nature Reserves which cover 17 hectares. The Council has several policies and initiatives which seek to increase the area of woodland in Renfrewshire for example the adopted Renfrewshire Local Development Plan (2021) outlines the delivery of the environmental spatial strategy which includes –

POLICY ENV 2: Natural Heritage, which requires Development proposals to consider the potential impacts on natural heritage. Proposals require to protect and restore degraded habitats, enhance and promote access to Renfrewshire’s natural environment and minimise any adverse impacts on habitats, species, network connectivity or landscape character.

The Renfrewshire Local Development Plan Delivery programme 2022 also sets out a series of actions such as the preparation of a Green Network Strategy, to identify greenspaces across Renfrewshire and opportunities for their protection and enhancement. The Renfrewshire Planning and Development Tree Policy (2022) also aims to protect and enhance trees and woodland across Renfrewshire. The Renfrewshire Biodiversity Action Plan also sets out sets out a positive and ambitious approach to biodiversity conservation and promotion.

2.6 Why manage deer?

Deer have an effect on our countryside and us in different ways at different times. These effects are described as impacts. Effective deer management aims to reduce negative impacts, and/or improve positive impacts. As explained in section 2.2 sustainable deer management can make important contributions towards meeting the public policy objectives to address the climate and nature crises.

Examples of deer management measures which local authorities could implement are shown in the table below.

|

Management measures |

Example |

|---|---|

|

Vegetation palatability, taste based repellents |

Planting / managing palatable and unpalatable plant species to encourage / discourage deer in certain areas. Using taste based repellent chemicals to discourage deer from eating certain plants |

|

Vegetation management |

Controlling road-side vegetation so that deer by the road can be more easily seen by motorists |

|

Road signage |

Warning signs to alert motorists to deer hazards at Deer Vehicle Collision hotspots |

|

Wildlife bridges / underpasses |

Provision of crossing points over or under roads and railways to allow deer and other wildlife to cross safely |

|

Individual tree protection |

Use of tubes, tree guards or cages to protect individual trees from deer browsing |

|

Fencing |

Deer fencing to prevent deer accessing sensitive habitat e.g. newly planted woodland, to prevent deer crossing a road, or to funnel deer movements towards a safe crossing point |

|

Scaring |

Use of auditory or visual scaring techniques to discourage deer from particular areas |

|

Responsible public access |

Providing information to the public e.g. in parks regularly used by dog-walkers, to advise the public of the presence of deer and of the need to keep dogs under close control |

|

Lethal control |

Local authorities could arrange culling of deer either by contacting: Members of a local deer management group / Lowland Deer Network Scotland Contracting a professional deer controller (this is the approach often taken by Forestry and Land Scotland) Training staff in deer control (the Deer Stalking Certificate) NB: NatureScot holds a register of fit and competent individuals who have the requisite level of skills and experience to carry out deer control safely and effectively. |

2.7 What information is needed to inform deer management?

Three main types of information can inform deer management:

- Information about deer impacts: e.g. deer vehicle collisions, assessments of deer impacts on biodiversity; forestry, farming, greenspace and domestic gardens

- Information about deer: e.g. range; density; numbers; sex ratio; reproductive rate; health

- Information about deer management: e.g. ; location, condition and date of erection of deer fences; number, sex and location of deer culled; carcass weight and condition of culled deer; number of people employed in deer management; income generated by recreational deer stalking

There is currently limited information of all three types available to inform deer management in Renfrewshire. McMorran et.al (2019) investigated the availability of information on deer management in a pilot area in the Stirling and Falkirk area. They identified a number of gaps in information in all three of the above areas, and made some recommendations for improvements in data collection. These recommendations were endorsed by the Lowland Deer Panel. However, it is unlikely that the availability of information to inform deer management is going to change substantially in the near future, due to public sector resource constraints.

Where there are gaps in the information available to deer managers, decision making should follow the precautionary approach. This means that decisions about how to manage deer should not be deferred, they should be made on the basis of the information that is available. An adaptive approach could also be adopted, with management being revised in the light of new information and depending on the results of previous measures.

3. Current deer impacts and deer management in Renfrewshire

3.1 Deer impacts in Renfrewshire

There is very limited information available about the positive impacts that flow from deer management in Renfrewshire e.g. the economic benefits from recreational stalking or venison sales; or the intangible benefit from the enjoyment and appreciation people feel from seeing wild deer. It is possible to say more about the negative impacts that deer can have, and the table below identifies potential negative impacts, and comments on what is known about impact levels in Renfrewshire, based on available information.

|

Negative Impact |

Private / Public Interest |

Impact in Renfrewshire |

Trend, Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

|

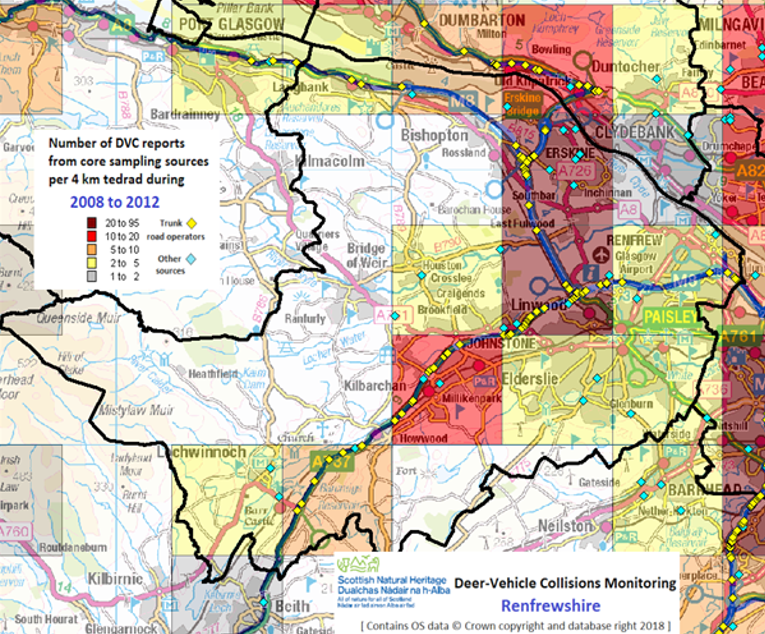

Deer vehicle collisions |

Both |

There were 107 Deer Vehicle Collisions recorded in Renfrewshire in the 5 years 2008 to 2012. This increased to 167 in the 5 years 2013 to 2017.[12] A high proportion of collisions are recorded on the M8 or the A737 accounting for 68% and 56% of records in these time periods (See Appendix 2, Maps 2 and 3) In 2012, concerns over DVCs on the B775 near Gleniffer Braes Country Park were reported to NatureScot. NatureScot sought to enter into discussions with Renfrewshire Council on how pro-active deer management can be instigated to reduce negative impacts from occurring. As part of this a deer count was conducted in and around Gleniffer Braes. In 2021, Renfrew Community Council and members of the local community raised issues with Renfrewshire Council and NatureScot around the perceived displacement of deer, which it was thought was at least partially linked to clearance of woodland and other development around the Renfrew area. An increased risk of DVCs from displaced deer was one of the concerns raised, as well as general concerns about deer welfare. Renfrewshire Council agreed to work with NatureScot to develop a Deer Management Statement in response. |

Worsening, High. It is highly likely that recorded DVCs are an underestimate due to under reporting. There is known to be a reporting bias from the trunk road network. |

|

Deer welfare – deer health and condition |

Both |

In certain urban sites there can be animal welfare concerns and the physical condition of deer can be poor compared to other areas.[13] Where deer occur at high density individual deer can experience welfare problems from parasites / disease. |

Uncertain, likely to be relatively low. Nature Scot has produced best practice guidance on managing deer in urban areas.[14]

|

|

Deer welfare – poaching, antisocial behaviour, interactions with dogs |

Both |

There were no recorded crimes in 2017/18 involving deer in the Police Scotland Renfrewshire and Inverclyde Division area in 2017/18, three in 2018/19 and none in 2019/20.[15] It is not possible to obtain a breakdown of incidents recorded by Police Scotland for the Renfrewshire specifically.[16] |

Uncertain. |

|

Natural Heritage |

Public |

There are ten Sites of Special Scientific Interest and two Special Protection Areas in Renfrewshire.[17] None of these SSSIs and neither of the SPAs are designated for features which would be likely to be negatively impacted by roe deer grazing or browsing, and overgrazing / undergrazing is not listed as a pressure affecting any of the sites.[18] Council owned and managed land includes part of Muirshiel Regional Park/Country Park; Gleniffer Braes Country Park; and Castle Semple Country Park. Together, the three Country Park’s contain around 200 hectares of woodland. The Council also owns West Tandlemuir farm in the Muirshiel Regional Park which extends to almost 1,400 hectares. The Council also owns three Local Nature Reserves, which together contain a further 11 hectares of woodland.[19] There has not been any HIA within the woodlands at these sites. Renfrewshire Council has also identified 106 sites of importance for nature conservation. Renfrewshire Council has an ownership interest in only 16 of the 106 SINCs. All 106 sites have the potential to be part of Roe Deer home ranges. In addition to the above sites, roe deer are present at the RSPB’s Lochwinnoch reserve (also part of Castle Semple Country Park), and the Scottish Wildlife Trust’s reserve. No deer issues have been recorded at either site.[20] |

No impact on designated features of protected areas. Impact on other natural heritage sites not known. May be locally moderate to high where sites contain woodland. Establishment of new trees / woodland likely to require individual protection or fencing. |

|

Trees and woodland |

- |

Around 13% of Renfrewshire is wooded, with a total area of 3,387 hectares listed in the National Forest Inventory in 2018. Only 5% of this woodland is within the National Forest Estate, and the remainder is in a mix of private and other public ownership. [21] Deer control by Forest and Land Scotland is keeping impacts on restocked conifers on the National Forest Estate within tolerable levels, but impacts on unprotected planted broadleaves are high, even where there is an active programme of deer control. As part of the commitment for Renfrewshire to become net zero by 2030, the Council is involved in creating wildlife-friendly environments. An initial set of eight locations have been selected, and works include new native tree planting.[22] |

Available information suggests impacts on unprotected planted trees or regeneration are likely to be at least moderate, and may be locally high. |

|

Parks / amenity |

Public |

Renfrewshire Council owns and manages around 30 hectares of parks and several hundred hectares of other greenspace (school grounds; golf courses; woodland and other greenspace).[23] Tree planting at Muirshiel, Parkhill, Gleniffer and Barwood have all used tree protectors. There is no systematic recording of impacts. |

Uncertain, likely to be relatively low. Potential for locally high impact where e.g. new amenity planting occurs close to areas with high roe deer density |

|

Private gardens |

Private |

An allotment association was contacted and reported no negative impacts from deer. |

Low. |

|

Farming |

Both |

The main deer species in Renfrewshire is roe. Whilst damage to farm land by roe deer can be locally significant e.g. browsing of a crop close to the edge of a woodland with a high density of roe deer, in aggregate the impact on farming interests from roe deer is likely to be low. |

Uncertain, likely to be relatively low. |

3.2 What deer management does Renfrewshire Council undertake currently?

Decisions on the need for deer fencing or other tree protection are taken on a site by site basis on the land which the Council owns / manages. The Council has not undertaken culling of deer on the land it owns. The Council has not currently put up any deer warning signs on roads for which it is the roads authority.

3.3 What deer management is carried out by others in Renfrewshire?

NatureScot can request an annual cull return from deer managers, which provide details of deer culled on a particular area. Landowners and deer managers are only required to submit a return if requested by NatureScot.

NatureScot receives two cull returns from Renfrewshire. For the five years 2015-16 to 2019-20 the two returns show a combined annual average cull of 35 roe deer.[24] This is highly likely to be a very significant underestimate of the number of roe deer culled in Renfrewshire each year.

In the upland red deer range (broadly, North and West of the Highland Boundary Fault) there is an established network of Deer Management Groups. These are voluntary groupings of landowners and deer managers, who meet to agree and discuss their deer management plans; and which act as a forum for resolving any conflicts which arise if there are competing deer management policies of individual owners.[25] The logic to these groups is that they are managing red deer, a herding species, whose populations range across the boundaries of even the typically large landholdings of the Highlands. In the lowlands, as noted above, the main species present, roe deer, are a territorial and not a herding species. The area over which collaborative deer management would be appropriate is therefore much smaller. That said, the average size of landholdings is also smaller and there remains a logic to collaborative deer management between neighbouring properties, just at a smaller scale. The analogue to Deer Management Groups in the lowlands is the Lowland Deer Network Scotland, which provides fora through its constituent deer groups for those who are interested in deer management to work together. There are currently eight groups active in lowland Scotland, but none which covers Renfrewshire.[26]

At present, there is no requirement in Scotland to pass a formal test or qualification to be able to cull deer, except for out of season or night shooting. NatureScot keeps a register of persons who are “fit and competent” to control deer who are eligible to apply for such authorisations. There is currently one person listed and one person who has been listed but whose listing has lapsed living in Renfrewshire, and a further 35 people who are either currently listed or who have been recently listed who live nearby (23 people currently listed and 12 who have been recently listed).[27] The number of people who take part in deer stalking who live in and around Renfrewshire is not known, but is likely to be higher than this.

4. Future deer management by Renfrewshire Council

4.1 How should the Council decide whether deer management is required?

Whilst until now Renfrewshire Council has not had a formally adopted policy or plan in place in relation to deer management, the Council takes its deer management responsibilities seriously. The Council will manage deer in accordance with an agreed deer management statement, which will set out how the Council will manage deer in accordance with the Deer Code. This statement will be the first step in adopting more detailed policies on deer management, and in implementing deer management actions in a consistent way, following an agreed process. In order to decide whether deer management is required, the Council should consider the information available to it. Decisions should be reviewed when new information is available, and in some situations, the Council may need to collect or commission information to support its decision making. The diagram overleaf illustrates an iterative decision-making process the Council could follow.

Figure 1 – A Decision Making Process for Deer Management

Note: under the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996 “damage” includes situations where deer and/or current deer management (or lack of) are causing (or are likely to cause): damage to woodland, agriculture, deer welfare or the natural heritage; damage to the public interest; injury to livestock e.g. where deer compete with them for food; or where deer are a danger or potential danger to public safety e.g. because of the occurrence of or the risk of deer vehicle collisions.

4.2 How does the Deer Code apply to Renfrewshire Council?

Chapter 1 of the Code states that it applies to all land managers who own or manage land where wild deer occur. Renfrewshire Council directly manages over 700 hectares of nature reserves, greenspace and parks, which include around 150 hectares of woodland.[28] The Code therefore applies to Renfrewshire Council.

Chapter 2 of the Code poses some questions, to help determine what deer management actions are relevant. The table below shows these questions, together with commentary in relation to Renfrewshire Council.

|

What species of wild deer occur on your land? |

Roe deer occur widely on land owned/managed by the Council. |

|---|---|

|

How often are there wild deer present on your land? |

Deer are present throughout the year |

|

What is the density and distribution of the wild deer population on your land? |

Roe deer occur widely. There is no information about deer densities. |

|

What is the health of the wild deer population on your land? |

Roe deer are widespread in urban and peri-urban areas in Renfrewshire. Whilst roe deer have adapted to live in these areas, they may be less than ideal deer habitat – deer are disturbed more often than they would be in rural locations, including more frequent interactions with dogs; and the ability of deer to access areas in which to feed may be restricted by development and roads. |

|

How mobile are the wild deer which occur on your land? |

Deer territories span across ownership boundaries. Roe deer are resident and do not move large distances seasonally. Male deer and young deer will move to establish new territories, and during the mating season. |

|

What effect are the wild deer having on your own land? |

There is no information available e.g. from herbivore impact assessment, to quantify this. Impacts are likely to be low across most land and habitat types, but may be locally high in woodland, especially in areas of tree planting / regeneration. |

|

What effect are the wild deer on your neighbouring land? |

Available evidence suggests that deer can have high impacts in places e.g. browsing damage to young trees. The trend and severity of such impacts will depend on what deer management is undertaken, if any. |

|

Can wild deer on your land move onto public roads and into green spaces? |

Yes |

Chapter 3 of the Code sets out what actions are needed to deliver sustainable deer management. Actions are divided into those which MUST be done to comply with the law, actions SHOULD be taken to avoid regulatory action by NatureScot, and actions which are ENCOURAGED as they demonstrate good practice in deer management.

Chapter 4 of the Code explains how landowners should collaborate to achieve sustainable deer management. Collaborative deer management in the lowland context was considered in detail in the report of the Lowland Deer Panel. The panel concluded that the scale over which collaboration was required depended on the species present. Where roe deer is the main species, as in Renfrewshire, the panel concluded that collaboration was appropriate at a local level.

Chapter 6 of the Code explains how it applies to Public Bodies. It states that Public Bodies should demonstrate good practice in the way they collaborate over deer management with neighbours. Additionally the Code states that Public Bodies must consider the Code when making regulatory decisions that could have an effect on deer, for example, local authorities should consider the implications of planning decisions on deer.

4.3 What MUST Renfrewshire Council do?

4.3.1 What MUST Renfrewshire Council do to manage deer?

The actions listed in the Code which MUST be undertaken largely relate to compliance with legislation and the Code can be read as presupposing that deer management by culling is already occurring. The legal requirement to comply with the provisions of the 1996 Act e.g. on close seasons, and with Firearms legislation, would only become applicable if deer were being managed by culling on land where the Council is responsible for deer management.

4.3.2 What MUST Renfrewshire Council do to regulate sales of venison?

Under section 33 of the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996, local authorities have powers to grant venison dealer licences. Each Local Authority is required to send a list of venison dealers in to NatureScot every year on the 1st January. Venison dealers are required to keep records of the deer they buy, including the species and sex, for at least three years. Under section 36 of the Act, it is an offence to sell venison without a venison dealer’s licence, or that has not been purchased from a licensed venison dealer.[29]

The Deer Working Group reported that in 2018 there were 178 licenced venison dealers in Scotland. The Group also found that 12 local authorities were not making returns of venison dealers in their area to NatureScot, including Renfrewshire.[30]

4.4 What SHOULD Renfrewshire Council do?

It is more relevant to consider the actions which the Code says the Council SHOULD be taking. The actions which are most relevant to the Council are listed in the table below with some commentary.

|

ACTIONS IN THE CODE |

IMPLEMENTATION BY RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL |

|---|---|

|

Actions to ensure that wild deer welfare is safeguarded Take account of the impact on the welfare of deer in planning decisions relating to the layout and management of public places and amenity planting. |

Renfrewshire Council’s Local Development Plan was adopted in December 2021.[31] Some of the areas zoned for housing in the plan, e.g. around Brookfield, Dargavel, Erskine, Gleniffer/Dykebar are likely to have roe deer populations.[32] When development begins, deer will move. The need to manage deer on sites which are being developed should therefore be considered. For example, the Council could request information on deer as part of the assessment of planning applications, and set conditions on permissions to ensure that any implications arising from developments are addressed. E.g. a requirement for the developer to produce a deer management statement or deer management plan.[33] The Council should consider deer impacts when the local development plan is next reviewed. The Council should also consider whether developments provide an opportunity to create infrastructure which will help to mitigate deer impacts, e.g. providing wildlife bridges or underpasses to enable deer and other wildlife to cross roads/railways and reduce collision risk.[34] NatureScot has produced guidance on assessing and managing deer at development sites, and the Council should follow this guidance in considering how to take account of impacts on deer arising as a result of development.[35] |

|

Actions to protect and enhance the environment Manage levels of grazing, trampling and browsing to deliver the favourable condition of natural features within designated sites. |

Features on the designated sites where the Council is a landowner are not susceptible to being affected by overgrazing / browsing by deer, and so this does not apply in Renfrewshire. |

|

Actions to protect and enhance the environment Manage grazing levels designed to prevent loss or damage to Scotland’s biodiversity, especially those key species and habitats identified in the Scottish Biodiversity List. |

There is no information available about the extent to which deer are negatively impacting on biodiversity on land owned/managed Renfrewshire Council and/or on neighbouring land. The Council should consider the need to collect information about deer impacts on the land it owns and manages. Assessments should focus on sites where woodland is a significant component (as woodland is the habitat most likely to be affected by roe deer), and especially on any sites where the woodland structure is known to be poor.[36] The relevant survey method is the Woodland Grazing Toolbox.[37] The Council should consider the need to train staff in this survey method. |

|

Actions to protect and enhance the environment Follow the Invasive Non-native Species Code to prevent further establishment of non-native species. |

Available information suggests Sika deer and Fallow deer which are non-native species are not present in Renfrewshire. The Council should have a procedure in place to record and report any sightings of Sika or Fallow deer on Council owned/managed land, which would then be a trigger for a decision on whether management was required. Muntjac deer are another non-native species which are not currently considered to be established in Scotland. They are spreading Northwards in England and are present in Northumbria and Cumbria. The same procedure should apply should there be reports of Muntjac on land which the Council owns or manages.[38] |

|

Actions to support Sustainable Economic Development Take account of other economic activities when managing wild deer and minimise negative impacts on them (e.g. food production, forestry, tourism and other rural businesses). |

The Council should consider the implications of its decisions on deer management on its own land for its neighbours. |

|

Actions to support social well-being Contribute to co-ordinated action to reduce road safety risks |

Deer Vehicle Collisions are increasing in Renfrewshire. The Council does not currently have a policy in relation to Deer Vehicle Collisions. The Council should use Deer Vehicle Collision maps, and other information sources, such local reports, to identify any hotspots within its area for which it is the Roads Authority. It should consider erecting deer warning signs at any such hotspots, and the need for additional measures, e.g. fencing, management of road verge vegetation. Where the risk of DVCs remains high after these measures have been implemented, the Council should collaborate with its neighbours to ensure that additional deer management is undertaken to reduce the risk of Deer Vehicle Collisions to an acceptable level. NatureScot has produced guidance on deer management measures which can reduce the risk of DVCs.[39] |

|

Actions to support social well-being Be appropriately trained, equipped and aware of health and safety risks associated with your deer management |

If the Council decided to use its own staff to cull deer, they should be appropriately trained[40] and work to site specific risk assessments. If the Council decided to secure deer control via a third party it should consider only using persons from the Fit and Competent Register kept by NatureScot[41]. There is currently only one person listed on the register who lives in Renfrewshire itself, but there are a further 23 authorised persons on the register who live nearby, mainly in Glasgow. [42] |

|

Actions to support social well-being Contribute to action to reduce negative impacts of deer on green spaces, public areas and gardens |

Information from an allotment association was that deer are having no impact on its site. No other information about deer impacts on green spaces, public areas and gardens is available. If high impacts are identified from deer which are likely to be resident on land which the Council owns or manages, the Council should consider what deer management is appropriate to address the damage. |

|

Actions which should be undertaken by Public Bodies Demonstrate good practice in collaborative deer management |

The Council should take an active role in collaborating on deer management with neighbouring landowners and deer managers. As a minimum there should be a designated point of contact within the Council with whom deer issues can be raised, and there should be an entry for deer in the A to Z section of the Council’s website. |

|

Actions which should be undertaken by Public Bodies Consider the impact of regulatory decisions on deer |

The Council should consider the impact of regulatory decisions it makes on deer, e.g. it should consider how planning decisions affect deer as described above |

4.5 What further actions COULD Renfrewshire Council take?

The focus of this Deer Management Statement is ensuring that the deer management carried out by Renfrewshire Council meets its requirements. The Code proposes a number of additional actions which could be taken to demonstrate good practice in deer management. Two examples of these actions are given below, with commentary.

|

Examples of actions to be ENCOURAGED under the Code |

Comment |

|---|---|

|

Promote training and on-going professional development of those involved in deer management. |

The Council could offer staff the opportunity to undertake training in herbivore impact assessment methodologies, deer management and/or the opportunity to obtain Deer Stalking Certificate qualifications. HIA could also be contracted out to ecological consultants as required. |

|

Provide information, such as where wild deer are likely to be seen, and encourage people to understand more about wild deer and their management. |

Public enjoyment of wildlife, including deer, is promoted by the Council’s ranger service, including e.g. signage, guided walks and education outreach. |

NatureScot (2017) has defined 14 public interest actions for deer management. The table overleaf lists these actions, and comments on how they might be delivered by Renfrewshire Council in respect of its own land.

|

Key Public Interest |

Comment |

|---|---|

|

The features for which sites are designated are not susceptible to being negatively impacted by deer, so this action is not applicable. |

|

As part of the commitment for Renfrewshire to become net zero by 2030, the Council is involved in creating wildlife-friendly environments. An initial set of eight locations have been selected, and works include new native tree planting.[43] |

|

Renfrewshire Council manages over xxxx hectares of greenspace which include several hundred hectares of woodland. As noted above, the Council is involved in creating wildlife friendly habitats some of which will include tree planting. |

|

There is limited information available about deer impacts in the wider countryside. Deer impacts may be locally high on sensitive habitats / features e.g. unprotected broadleaved tree plantings or regeneration. As set out in Table 4 above, Renfrewshire Council should consider the need to collect information about deer impacts on sites it owns and manages. |

|

Renfrewshire Council has set a target for Renfrewshire to become net-zero by 2030. As noted above, the Council is involved in creating wildlife friendly habitats, including treeplanting and woodland creation as part of the work to meet this target. The Council is also considering opportunities to store and sequester carbon on land it owns and manages. This includes investigating the feasibility of peatland restoration on land the Council owns in Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park. |

|

The Council should have a procedure in place to record and report any sightings of Sika or Fallow deer on Council owned/managed land, which would then be a trigger for a decision on whether management was required. A similar procedure should apply should Muntjac deer ever become established in Renfrewshire |

|

This is, or may be applicable to deer management on Council owned/managed land |

|

The economic impact of deer management in Renfrewshire is not known, but is likely to be relatively limited. The Council is developing a deer management statement which will identify the actions the Council will take to minimise the economic costs of deer |

|

Renfrewshire Council is committed to ensuring that staff / contractors involved in deer management on Council owned/managed land have the appropriate qualifications, training and equipment. |

|

Renfrewshire Council encourages appropriate public access to the land it owns and manages to encourage public enjoyment of the countryside and for health and wellbeing benefits. Deer management on land owned and managed by the Council will be consistent with this. |

|

Renfrewshire Council will communicate effectively with neighbouring land owners/managers about deer management issues. It will identify a point of contact within the Council with whom deer issues can be raised. |

|

Renfrewshire Council is committed to ensuring that deer management on land it owns/manages takes into account deer welfare |

|

Renfrewshire Council is developing a deer management statement which will set out the Council’s approach to deer management. |

5. Recommendations

- Renfrewshire Council should adopt an iterative approach to deer management. The first step in this approach is to begin gathering information on deer impacts. Once this information is available, the Council should consider what further deer management measures are required. The effectiveness of any management should be monitored.

- Renfrewshire Council should consider the effects of proposed development on deer as part of the development planning process.

- Renfrewshire Council should consider the effects of proposed developments on deer in its role as planning authority. It should ensure that developers provide it with information in order to allow it to assess this. Where developments are likely to have an adverse impact on deer, the Council should require developers to address them through the production of a deer management statement.

- Renfrewshire Council should consider opportunities to create green infrastructure to allow deer and other wildlife to safely cross transport corridors

- Renfrewshire Council should consider training officers in Herbivore Impact Assessment (HIA), or contracting in ecological consultants to carry out HIA on a site by site basis. Making initial assessments of sites the Council owns and manages where woodland is a significant component would be an obvious first step in adopting an iterative approach to deer management in recommendation 1.

- Renfrewshire Council should develop a procedure to record and report any sightings of Fallow, Sika or Muntjac deer on Council owned/managed land, which would then be a trigger for a decision on whether management was required.

- Renfrewshire Council should have a nominated point of contact for deer issues.

- Renfrewshire Council must submit an annual return on the number of licenced venison dealers within its area to NatureScot each year, as required by the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996

6. References

Armstrong, H. Black, B. Holl, K. & Thompson, R. 2020. Assessing Herbivore Impacts in Woodlands: An Observation-based Method.

British Deer Society. 2016. Deer Distribution Survey 2016.

British Deer Society. 2022. Personal Communication.

Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019

Conservation Evidence. Install overpasses over roads/railways.

Conservation Evidence. Install tunnels/culverts/underpass under roads.

Deer (Scotland) Act 1996

Deer Working Group. 2020. Final Report.

Forestry Commission. 2018. Forestry Statistics 2018.

Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016

Lowland Deer Network Scotland. 2022. Personal communication.

Lowland Deer Panel. 2019. Report to Scottish Natural Heritage, February 2019.

McMorran, R., Gibson-Poole, S. & Hamilton, A. 2019. Lowland deer management: assessing the delivery of public interests. Scottish Natural Heritage Research Report No. 1069.

NatureScot 2020a. Scottish Biodiversity Strategy post 2020 - A Statement of Intent.

NatureScot. 2022. Personal Communication

Police Scotland. 2019. Personal Communication

Renfrewshire Council. 2019 APSE performance networks - service profile data 2018/19

Parks, open spaces and horticultural services. Unpublished dataset.

Renfrewshire Council. Biodiversity areas in Renfrewshire. Available

Renfrewshire Council. Climate change action to make Renfrewshire net zero. Available

Renfrewshire Council. Enjoying Nature in Renfrewshire. Available

Renfrewshire Council. Preparation of the next Local Development Plan.

Renfrewshire Council. Renfrewshire’s plan for net zero. Available

RSPB Scotland. 2022. Personal Communication

Scotland’s Environment Web: Protected Nature Sites. Available

Scottish Forestry. 2020. Personal Communication

Scottish Government. 2015. Scotland’s Wild Deer a National Approach, Including 2015-20 Priorities

https://www.gov.scot/publications/wildlife-crime-scotland-2018-annual-report/ (published 23 December 2019)

https://www.gov.scot/publications/wildlife-crime-scotland-2019-annual-report/ (published 23 December 2020)

https://www.gov.scot/publications/wildlife-crime-scotland-2020-annual-report/ (published 1 April 2022)

Scottish Government. 2020a. Securing a green recovery on a path to net zero: climate change plan 2018–2032 – update. Available

Scottish Government. 2020b. Protecting Scotland, Renewing Scotland: The Government's Programme for Scotland 2020-2021.

Scottish Government. 2021a. Scottish Government Response to the Report from the Deer Working Group on ‘The management of wild deer in Scotland’. Online. Available

Scottish Government. 2022 Personal Communication

Scottish Government. Undated. Deer Working Group. Available

Scottish Natural Heritage. 2011. Code of Practice on Deer Management. Available at: Code of Practice on Deer Management. 2011. Scottish Natural Heritage. Available

Scottish Natural Heritage. 2012. Roe deer count report, Gleniffer Braes Country Park. Unpublished report.

Scottish Natural Heritage. 2017. Deer Management Plans: Delivering the Public Interest. Available

Scottish Natural Heritage. 2019. Lowland Deer Panel. Report to Scottish Natural Heritage February 2019. Available

Scottish Wildlife Trust. 2022. Personal Communication.

SSPCA. 2022. Personal communication.

Watson, P. Putman, R & Green, P. 2009. Methods of control of wild deer appropriate for use in the urban environment in England. Deer Initiative Research Report 09/4.

Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011

Footnotes

[1] By Part 3 of the Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011 and Part 8 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016.

[2] Scottish Natural Heritage is still the legal entity under the Natural Heritage (Scotland) Act 1991. It rebranded as Nature Scot in 2020, and so is referred to as NatureScot throughout this document.

[3] Set in the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019

[4] British Deer Society. 2016. Deer Distribution Survey 2016 – Roe deer Red deer Fallow deer and Sika deer

[5] Reconfirmed means that as well as being recorded by the survey in 2016, they were also recorded there in one of the previous surveys of either 2007 or 2011.

[6] NS47 is mainly in West Dumbartonshire, and includes the Kilpatrick Hills where red deer are known to be present. NS26 is mainly in Inverclyde and North Ayrshire, and also includes part of the Renfrewshire Hills. NS37 is divided between Inverclyde, Argyll and Bute, West Dumbartonshire and Renfrewshire.

[7] NatureScot (2012) Roe deer count report, Gleniffer Braes Country Park. Unpublished.

[8] Analysis of all types of woodland in the Land Cover Scotland 1988 and the National Forestry Inventory for Scotland 2020 datasets. See also Map 1 in Appendix 2.

[9] Forestry Research. 2020. Forestry Statistics 2020. Available

[10] Agricultural parishes are administrative units used in the agricultural census to provide local level census information.

[11] Renfrewshire Council. 2019

[12] Analysis of Deer Vehicle Collision data available from NatureScot Natural Spaces website

[13] Green, P (2008) cited in Watson et. al (2009)

[14] NatureScot. Best Practice Guides. Deer in towns. Part 1 Available and Part 2

[16] Police Scotland. 2019. Personal communication.

[19] Figures derived from analysis of the National Forest Inventory for Scotland 2020, clipped to the sites boundaries in GIS.

[20] RSPB Scotland and Scottish Wildlife Trust (2022). Personal communications.

[21] GIS analysis of the National Forest Inventory 2020 and GIS shapefile of the National Forest Estate, clipped with the boundary of Renfrewshire Council.

[22] ArcGIS StoryMaps

[23] Renfrewshire Council. 2019

[24] One of the returns is from Forestry and Land Scotland for deer culled on the National Forest Estate, so covers more than one landholding.

[25] As an example, the deer management policies of neighbouring owners could come into conflict where one neighbour wants low deer numbers, because they want natural regeneration of woodland without fencing, whilst another neighbour wishes to maintain relatively high deer numbers for recreational deer stalking.

[26] Lowland Deer Network Scotland. (2022) Personal communication.

[27] NatureScot. (2022) Personal communication. Fit and competent certification lasts for five years, and must then be renewed for an authorised person to remain on the register.

[28] See section 2.5 above

[29] There is a derogation allowing local sales of venison by hunters who supply small quantities of wild game or wild game meat directly to the final consumer or to local retail establishments directly supplying the final consumer.

[30] Deer Working Group. (2020) Final Report, Section 11.4 and Figures 25 and 26.

[32] Based on a comparison of the areas zoned in the maps accompanying the plan with aerial photography.

[33] For an example of such a requirement, South Lanarkshire Council’s Planning Committee proposed that a deer management statement be a planning condition for the Kypemuir wind farm extension (Report to Planning Committee, 29 January 2019, Application Reference: P/18/1013). This recommendation was followed and the Energy Consents Unit’s Decision Letter of 13 September 2019 includes a requirement for the developer to produce a deer management statement at paragraph 54 (Reference ECU 00000541)

[34] For a review of the effectiveness of wildlife bridges see, Conservation Evidence. Install overpasses over roads/railways. Conservation Evidence. Install tunnels/culverts/underpass under roads Available

[35] Scottish Natural Heritage. 2016. Guidance - Planning and Development - What to consider and include in Deer Assessment and Management at Development sites. Available

[36] Indicators of poor woodland structure would include e.g. absent or poorly developed understorey vegetation, or an uneven age structure dominated by mature trees.

[37] The Woodland Grazing Toolbox has been developed by Scottish Forestry, and is a guide to developing a woodland grazing plan. As well as advice on developing a plan, it contains a methodology for assessing herbivore impacts in woodland: Armstrong et. al (2020) Assessing Herbivore Impacts in Woodlands: An Observation-based Method. Available

[38] British Deer Society. 2016. Deer distribution survey: Muntjac. Available The Deer Working Group’s report also discusses Muntjac at section 17.3

[39] NatureScot. Deer Vehicle Collisions (webpage). Available

[40] The recognised training which assesses competence in deer management is the Deer Stalking Certificate (DSC), which has two Levels. Achievement of Level 2 is generally regarded as a satisfactory level of competence for a person to go out and manage deer on land belonging to a third party e.g. it is normally required by Forestry Commission Scotland for contractors/recreational stalkers in order to manage deer on the National Forest Estate.

[41] Essentially competence is demonstrated by having a DSC Level 2 qualification, or DSC Level 1 with supporting references. Further details are available on the NatureScot website

[42] NatureScot. 2022 Personal communication.

[43] ArcGIS StoryMaps

7. Appendices

7.1 Appendix 1 – Information requested and meetings held in preparing this statement

Meetings

7 April 2021 – Inception meeting with Susan Dickson and Pauline Newton from Renfrewshire Council, and Kevin McCulloch from NatureScot.

Information requested from Nature Scot

- Details of any deer counts / monitoring involving SNH in Renfrewshire?

- Cull returns received from properties in Renfrewshire

- Authorisations granted in Renfrewshire for night shooting, shooting out of season.

- Fit and competent persons within Renfrewshire

- Deer Vehicle Collision maps for Renfrewshire

- Summary details, if available to NatureScot, of any complaints raised in relation to deer?

- Details of any Herbivore Impact Assessment carried out on designated sites in Renfrewshire, and whether any designated sites in Renfrewshire in unfavourable condition due to deer impacts?

Information requested from Renfrewshire Council

- Details of land owned/managed by the Council

- Details of any policy on deer management the Council has

- Details of any herbivore impact assessment carried out, and any deer impacts recorded in on trees, woodland, or in greenspaces or in public parks

- Details of the Councils policy in respect of Deer Vehicle Collisions

- Whether the Council submits a return to Nature Scot on licensed venison dealers in Renfrewshire

Other information requests

Amey – Information on deer management and deer impacts on the trunk road network in Renfrewshire

British Deer Society – contacted by email requesting any additional information on distribution of deer in Renfrewshire.

Forestry and Land Scotland – information on deer management on its landholdings in Renfrewshire. No response was received.

Glasgow Airport – information on any deer management carried out in and around the airport. No response was received.

Growing Glen Burn & Erskine Community Allotments – whether deer present on and having any impacts on allotment sites.

Lowland Deer Network Scotland – whether it has any members from Renfrewshire.

RSPB Scotland – contacted to ask for information about deer, deer management and deer impacts at their reserve in Renfrewshire.

Scottish Forestry – Information on deer impacts on private forestry and woodland planting proposals in Renfrewshire. No response was received.

Scottish Government Rural Payments and Inspection Department – statistical information on farming in Renfrewshire.

Scottish Land and Estates – whether any of its members in Renfrewshire could provide any information on deer management on private landholdings. No response was received. A private landowner known to carry out deer management in Renfrewshire was also contacted through their agent. No response was received.

Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SSPCA) – requested information on any callouts or reports related to deer welfare in Renfrewshire.

Scottish Wildlife Trust – contacted to ask for information about deer, deer management and deer impacts at their reserve in Renfrewshire.

7.2 Appendix 2 – Maps

7.3 Appendix 3 – NatureScot’s approach to deer management

This diagram illustrates the approach that NatureScot follows to achieve sustainable deer management. Initially NatureScot will become involved and offer guidance and support, but where a threat to public interest is identified, then NatureScot can move to Intervention, and finally Regulation.