NatureScot Research Report 1343 - Source to Sea - enabling coherent, efficient and synergistic outcomes

Year of publication: 2023

Authors: Celeste Kellock (NatureScot; University of Stirling), Chris Leakey (NatureScot), Christian Schröder (University of Stirling), Nicola Melville (SEPA), Janet Khan (SEPA), Scot Mathieson (SEPA)

Cite as: Kellock, C., Leakey, C., Schröder, C., Melville, N., Khan, J. and Mathieson, S. 2023. Source to Sea - enabling coherent, efficient and synergistic outcomes. NatureScot Research Report 1343.

Preface

NatureScot, SEPA and the University of Stirling recognise that more needs to be done to address the twin climate and biodiversity crises. This report explores the potential to build on existing good practices, to enable more effective, coherent management of land, freshwater and sea, and to target action to where we can achieve improved outcomes for the environment and society in Scotland. The report is based on a collation of expert insights, experiences and recommendations from a broad community of relevant people and organisations across multiple sectors and specialisms, collected across a series of workshops and other discussions. The authors are very grateful to all of those who generously contributed their time and ideas.

This report provides a helpful, early think-piece to stimulate more discussions, and to help inform future approaches to source-to-sea thinking in Scotland. We will continue to discuss the recommendations further, within and between our organisations, and with Scottish Government.

Keywords

source to sea; land-use; marine; collaboration; environmental management; connectivity; water; soil

Background

This report is the result of an internship project between NatureScot, SEPA and the University of Stirling. The objective was to open dialogue, exploring and promoting opportunities for more coherent source-to-sea management in Scotland, including a high-level review of land-sea connections in Scottish policy. This was partly achieved through two core workshops. The workshops were supplemented by discussions with environmental practitioners and policy contacts within NatureScot, and with other agencies, government departments and researchers, to gauge ambitions, opportunities and challenges for more holistic management across environmental systems. The potential for a step-change in action addressing the non-energy dimensions of the climate and nature crises is the primary driver, while also recognising the many positive synergies with social and economic outcomes.

This project report aims to:

- Highlight opportunities for more holistic environmental management from land to sea in Scotland.

- Explore multiple benefits of the source-to-sea approach, showing how it can contribute to multiple strategies, policies and goals, across the environment, society and economy.

- Convey how policies could better enable integration and coherent management decisions that reflect the connectivity of land, freshwater and sea.

- Investigate the extent of source-to-sea management intent within current Scottish policy drivers.

- Explore the challenges to, and solutions for, source-to-sea approaches.

- Develop recommendations for progressing source-to-sea approaches.

While focussed on Scotland, dialogue and insights have been wide-reaching, with examples and inspiration from around the UK and internationally. Many of the conclusions and recommendations are relevant to other countries and regions.

Main findings

- There is no room for complacency in addressing the twin nature-climate crisis. There is raised ambition on net zero, to halt biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation, and a greater appetite and opportunity for nature restoration and recovery, but ambition must be partnered with action. Recognising deficiencies in our current approaches can unlock new opportunities to deliver existing commitments in an efficient and timely manner.

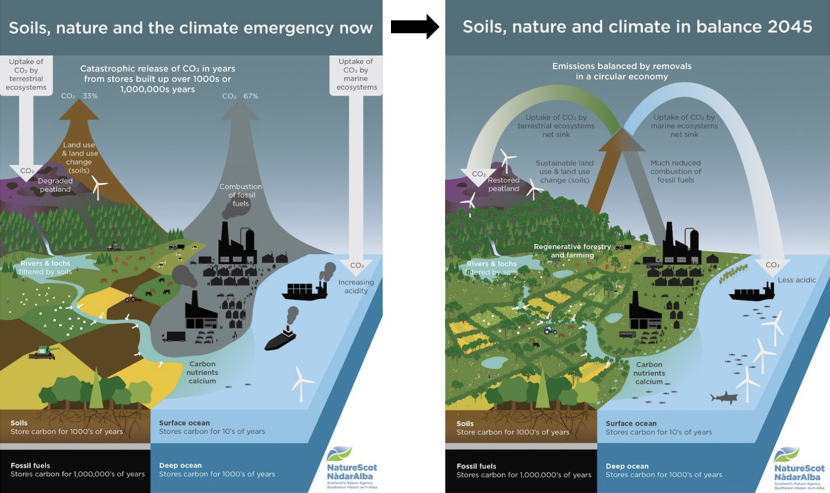

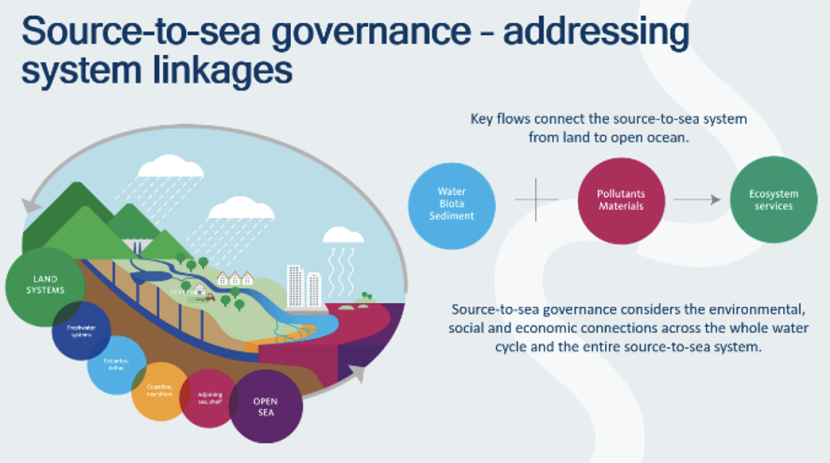

- The entwined challenges for climate and nature are underpinned by cumulative disruption to the fundamental biophysical processes and systems of Earth, from regional to planetary scales. Solutions therefore need to address those disrupted systems (see Figure 1); source-to-sea approaches that avoid fragmenting the components of the system should be an important part of our response.

- The fragmentation of environmental management frequently separates work on land, freshwater, estuaries, coasts and seas, overlooking their inherent connectivity via the water environment. Water itself is a fundamental ecosystem attribute but is also the medium for a multitude of biophysical flows. Some ‘flows’ are anthropogenic (e.g. contaminants); other flows are natural (e.g. species, carbon, nitrogen, organic matter) but human activity can cause them to become unbalanced and detrimental to nature and people.

- Despite some limited success with integrated approaches, such as catchment scale management, working across these geographical units, specialisms and sectors remains the exception. Better recognition and communication of the multiple benefits of an action, across environmental, social and economic interests, can inspire new and expanded partnerships across disciplines, sectors and geographical jurisdictions.

- Scotland already has key government strategies, such as the Land Use Strategy, National Planning Framework 4 and the Blue Economy Vision, giving direction for multiple benefits arising from better integration of governance from land to sea. However, their clear intent for a connected approach is not always realised at an operational level. Some issues fall between the gaps, and opportunities are missed to incentivise better upstream-downstream outcomes. Often, we fail to recognise and celebrate (sometimes distant) benefits of positive changes on land and in freshwater, thus understating the true value of nature and our actions.

- With scope for regulatory, technological and behavioural solutions, to name a few, the solutions proposed in this report are not just for NatureScot. These challenges are fundamentally tied to the biophysical processes of Earth systems and the potential for nature-based solutions are plentiful. Through a source-to-sea approach we can find synergy with blended solutions from a variety of sectors and specialisms.

- There is considerable appetite to embrace source-to-sea approaches, amongst public bodies, charitable and private sectors, to plug gaps in our environmental management systems and to create synergies and efficiencies through joint action. The source-to-sea narrative can lend itself to creative engagement, to capture public attention and connect communities to the wider environment, but also to coax professionals from narrow silos and embrace new ways of working.

- Source-to-sea action can deliver multiple long-term benefits that include social and economic outcomes, as well as environmental. Some benefits will be place-based while others will be diffuse and not place specific; some may transcend jurisdictional and geographical boundaries, such as when mitigating climate change. As such, source-to-sea approaches can help us maximise positive impact from our investments and efforts, with benefits that span health, well-being, food security, climate resilience and more.

- Moving beyond piecemeal interventions from fragmented governance systems is challenging and may even seem radical, but is necessary to address the systemic problems effectively and efficiently. Enabling actions include (a) the merging and coordination of data sets, models and evidence tools, (b) embracing communication and engagement methods that make best use of creativity, and insights from psychology and sociology, and (c) unlocking the opportunities for upstream-downstream flows in green investment and nature-based solutions. However, behind these and other enablers lies one common need: to encourage collaboration and coordination between sectors, between disciplines and between actors along the full extent of the source-to-sea continuum.

- Recommendations for progress in the adoption and implementation of source-to-sea approaches are made, for NatureScot and for Scotland generally, but have broader geographic relevance. Some suggestions fall within the remit of regulation and policy-led interventions, while others call for enhanced communication, diverse partnerships, and for advances in science and data coordination to help prioritise our efforts and inform decision-making. These recommendations (section 9.5 and 9.6 of full report) are many and varied, including:

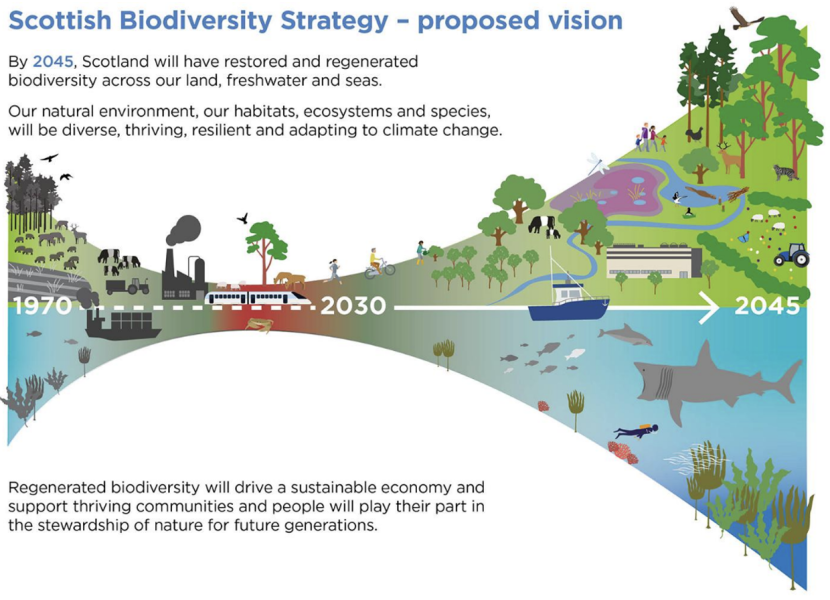

- Identifying timely opportunities to influence emerging government strategies and plans (Scottish Biodiversity Strategy, national and regional marine plans, and post-EU-exit agricultural reforms).

- Proper integration of terrestrial and marine governance systems, such as the dovetailing of processes for marine plans and local development plans, should go from ‘nice to do’ to ‘must do’. Similarly, land management strategies (farming, forestry and upland) need to be integrated.

- Evidence and data priorities, including; connecting existing datasets, enhancing spatial and temporal resolution of data, and incorporating pressures originating on land when evaluating marine cumulative effects. Recognising and enabling the important role of social science can help unlock multiple benefits across these socio-ecological systems.

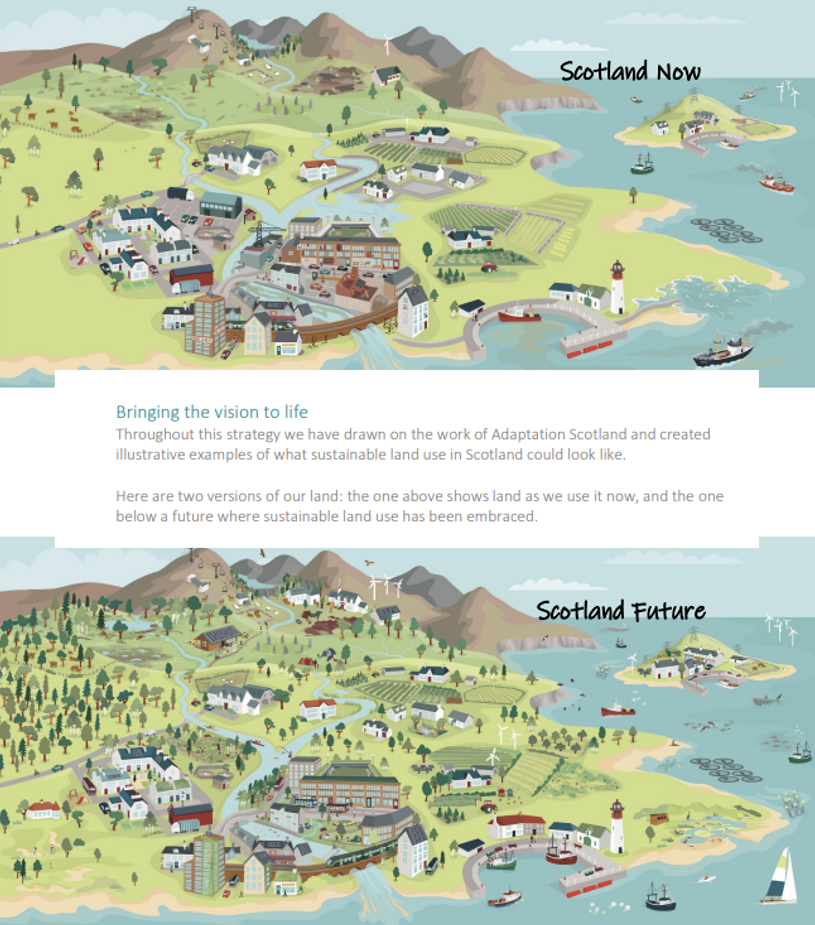

Two images comparing the current situation with future ambitions, as regards the interaction of soils, nature and climate, thereby promoting timely and positive action to re-balance earth-system processes. Source-to-sea approaches should play a fundamental role in this necessary step-change to address the twinned climate and nature crises. Within this, the future scenario includes much greater use of regenerative farming and forestry, significant land-use change with expansive areas of restored natural habitat, and more sustainable practices where industries to operate.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank NatureScot for hosting and funding the internship, and SEPA and the University of Stirling as the employers of the rest of the core team in this partnership. Participants in workshops and many valuable conversations are far too many to name, from within NatureScot and from a wide variety of public, academic and third sector organisations. Similarly, we are grateful to those actively contributed to delivering our workshops, as speakers, facilitators and scribes (detailed in the annexed workshop reports). Artist Jenny Capon provided the excellent graphic recording of our final workshop.

1. Introduction

Nature and climate continue to exhibit negative trends or a degraded status due to anthropogenic actions, threatening tipping points from which it will be hard or impossible to recover. We cannot solve the climate crisis without also solving the nature emergency, and vice versa. Our progress with both is hindered by fragmented policy and management systems that adopt convenient environmental boundaries between land, freshwater, coastal and marine systems. These systems are inherently connected, most notably via biophysical flows through soils and the water environment, yet we have limited interaction between processes, sectors and organisations working within these silos. The consequences of source-to-sea flows can manifest at local, catchment and regional seas scales, but also contribute to planetary-scale processes such as the carbon and nitrogen cycles. To address the climate-nature crisis we must mobilise and utilise collaboration and communication between biophysical systems and sectors, moving towards a more holistic approach for land to sea management. Figure 1 illustrates the need for source-to-sea approaches in addressing the broken circularity of biophysical processes of planet Earth. For instance, burning fossil fuels and large-scale land-use change are at the heart of our broken carbon cycle. This is further exacerbated by a lack of nutrient circularity within the system leading to less biodiverse, simpler, more degraded and compacted soils heightening vulnerability to climate change. Source-to-sea approaches are essential to tackling this land-based dimension, which represents a substantial portion of Scotland’s net emissions. The National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory shows that land based emissions comprised 48% of Scotland’s total net emissions in 2021 (NAES, 2023).

Connections across the land – freshwater – coastal - marine systems are central to the source-to-sea approach, which fosters the understanding that altering an area of the environment can have an effect elsewhere (Mathews et al., 2019). Positive and negative impacts could, and often do, alter water quantity, quality, temperature and chemical properties. There are social, environmental and economic risks associated with using a siloed and fragmented approach to address the nature-climate crisis, including missed opportunities to help people and nature adapt and be resilient to extreme climate events that are already locked in. In the UK there has been a general net loss of nature since the 1970 baseline; in Scotland, 49% of species have decreased in abundance and 11% of species are threatened (Walton et al., 2019). We have several government strategies that mention land to sea connections but limited implementation or co-ordinated holistic action on large scales at present.

The global climate-nature emergency is prompting increasing ambition and investment in the blue economy (Scottish Government, 2022a), biodiversity (Scottish Government, 2023a) and nature finance (Scottish Government, 2022b), all of which span terrestrial-marine environments. A holistic, source-to-sea approach ensures that we consider upstream and downstream impacts so that our actions and investments work in harmony to achieve common climate and nature goals, and do not have negative impacts elsewhere in the system that will require additional resources to fix. Source-to-sea management enables us to realise and nurture synergies and efficiencies between departments, organisations and actions to produce system wide benefits for society, the economy and the environment. A holistic approach can align policy objectives whilst enabling better policy implementation.

2. Methods

2.1 Workshops and dialogue

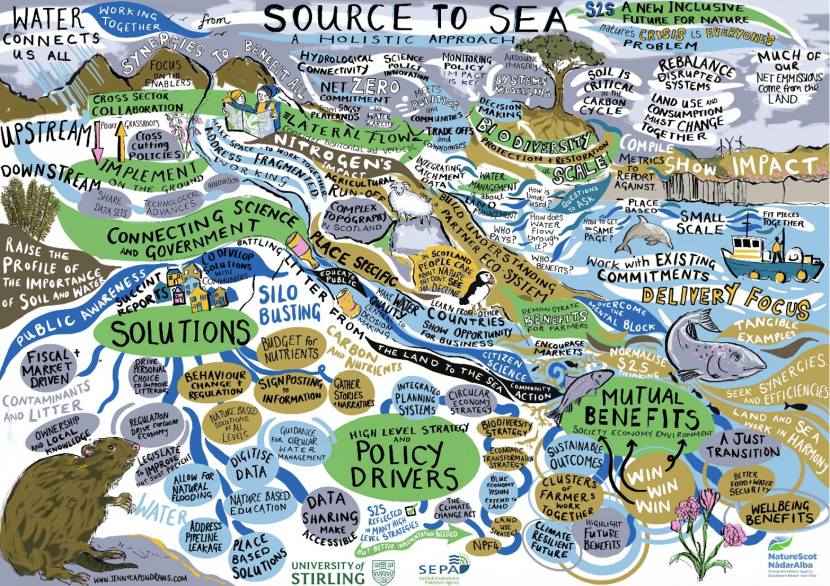

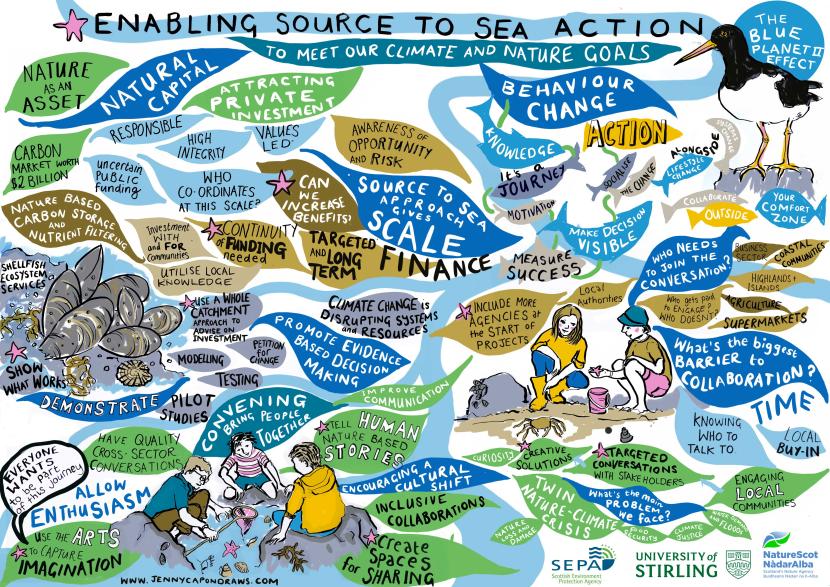

Two workshops provided key opportunities to share and gather insights across a diverse group of policy contacts, researchers and practitioners from terrestrial, freshwater and marine disciplines. Details of these workshops, including full reports, are detailed in Annex 2 and Annex 3. The second workshop included graphic recording by an artist to produce a visual note of key messages (see Figures 6 and 7) and are available for separate download.

These events and the dialogue they generated were supplemented by a literature review and by numerous other conversations throughout the project, with relevant experts and organisations across the public, private and charitable sectors.

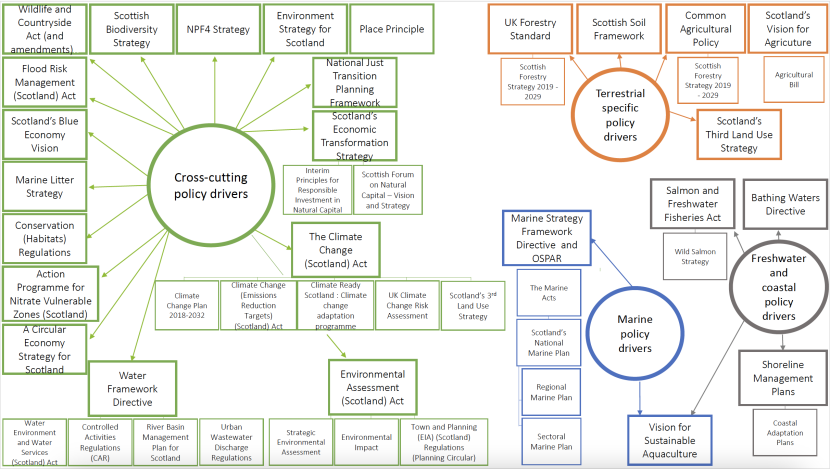

2.2 Mapping policy drivers

A map of strategic policy drivers was created to show the main terrestrial, freshwater, coastal and marine policy drivers, to highlight cross-cutting strategies that aim to foster land to sea connections, and to direct some of our targeting of policy contacts for dialogue and workshop attendance. This exercise is not exhaustive but includes key and overarching policy drivers in Scotland across the land to sea interface (Figure 2).

An image showing some of the key areas of Scottish Government strategy and policy that already indicate intent and ambition for approaches that coherently consider the inherent connectivity of land and sea via the water environment. This is not a comprehensive analysis, but an exercise that has informed the direction of this project. Some of these policy drivers are cross-cutting by definition, others ostensibly exist for terrestrial, freshwater, coastal or marine outcomes, but actually have broader relevance.

Full size diagram of existing and emerging policy drivers for source-to-sea action.

3. Discussion

3.1 Global context of source-to-sea engagement

The source-to-sea approach is growing globally, fostering connectivity, communication and collaboration between upstream and downstream actors, and across sectors. The Action Platform for Source-to-Sea Management plays an integral role in bringing together organisations committed to more holistic environmental management, currently spanning forty organisations over six continents. The source-to-sea approach is gaining international traction; the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) have created a Source to Sea Pollution Unit and set related ambitions in their 2022-25 Strategy (UNEP, 2022); and the UNECE Global Workshop on Source-to-Sea Management (UNECE, 2022) held in Geneva in 2022 brought together interested practitioners from numerous countries and several continents. Source-to-sea also formed part of Interactive Dialogue 3 on Water for Climate, Resilience and Environment (United Nations, 2023) at the UN Water Conference 2023.

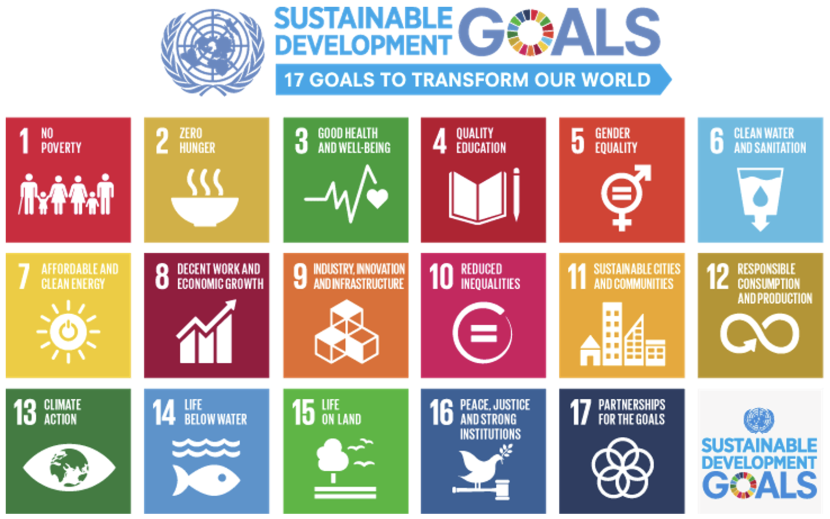

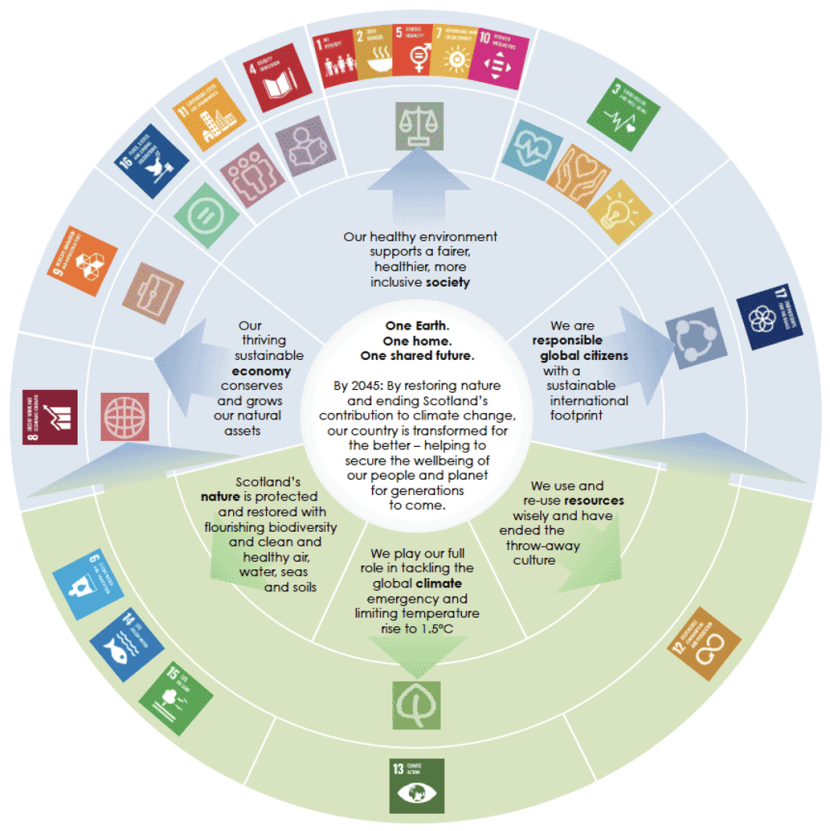

In 2015, all UN member states adopted the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, centred around 17 sustainable development goals (Figure 3). Scotland’s National Performance Framework (NPF) serves to localise the global SDGs. In the UKs Voluntary National Review 2019 (UK Government, 2019), the importance of interlinkages between the SDGs and sectors highlights the central role collaboration plays in achieving national and international goals.

The ‘SDG Network Scotland’ supported a national review to drive action (Scottish Government, 2020a) on the SDGs. It emphasised the importance of partnership and collaboration for achieving national outcomes, and it was recognised that there is more that can, and needs to be done, to work across boundaries for positive change. One of the fundamental challenges highlighted is the need for more "intensive, multi-partner cooperation across all aspects of delivery” (Scottish Government, 2020a). Similar conclusions were also made through the Christie Commission review of public services in Scotland (Christie Commission, 2011) but the implementation of the recommendations remain incomplete. A source-to-sea approach is a promising means of helping to meet this challenge, working across social, environmental, and economic issues. Water is central to achieving all SDGs, without which the health of our society, environment and economy would all decline. Ultimately, plans to achieve SDG targets could be undermined if we do not consider upstream-downstream processes.

- This approach is most immediately relevant to targets across SDGs 6 and 14 (‘Clean Water and Sanitation’, and ‘Life Below Water’). For example:

- By taking a source-to-sea approach we can increase water security and access by upstream and downstream actors collaborating to achieve sustainable storage and flow of water.

- Collaborations with planners (terrestrial-coastal-marine) and landowners can minimise pollution flows and improve soil functions (e.g. reducing soil compaction) that influence water quality and flow while also providing benefits for biodiversity and building resilience against climate change. There are many opportunities for nature-based solutions; these can be identified in piecemeal fashion but would be most effectively progressed by more fundamentally embedding the economy in outcomes for nature (e.g. Dasgupta, (2021).

A graphic of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

However, the benefits of a holistic source-to-sea approach can span much further, synergistically and simultaneously working across multiple SDGs (see Figure 3). A more holistic approach builds capacity for sustainable, environmentally and ecologically productive food systems (SDG2) while also addressing the land to sea flow of chemicals and excess nutrients, minimising the contamination of water and soils to ensure that we have an environment that can promote good health and wellbeing, and access to green and blue spaces (SDG3). This approach is designed to facilitate increased circularity of resources (i.e. nutrients, materials) to improve the sustainability of consumption and production and minimise environmental pollution and degradation. Through collaborative action, supply and demand can be built across all levels to reduce, recycle and reuse resources (SDG12).

A source-to-sea approach should improve the sustainability of developments across urban and rural environments through creating efficiencies in the planning process that enable a more climate resilient environment to grow and evolve. Blending place-based and source-to-sea approaches can support communities and protect the cultural and natural heritage within them (SDG11). Water is intrinsically linked to life on land and sustainable water management is essential to maintaining and restoring diverse and resilient systems on land, and nature-based solutions on land have enormous potential to help manage downstream pressures and effects (SDG 15). Strengthening resilience to address the climate-nature crises is a cross-cutting challenge that requires inclusive and collaborative action from land to sea, at national, regional and local levels (SDG 13).

Many source-to-sea benefits can also help address SDGs 1 (‘No Poverty’), 8 (‘Decent Work and Economic Growth’), and 9 (‘Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure’), e.g. creating green economic growth and jobs for different skillsets, facilitating skills sharing and development, developing innovation and technologically advanced tools and models, and through creating more sustainable urban and rural environments that benefit different communities and cultures. Opportunities to achieve sustainable development outcomes across the source-to-sea continuum have previously been evaluated for the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (Berggren and Liss Lymer, 2016), and recently discussed on international panels at the UN Water Conference (IUCN, 2023a).

At the Convention for Biodiversity 15th Conference of Parties (CBD COP15), the UK adopted the Global Biodiversity Framework, committing to conserve and sustainably manage at least 30% of the world’s lands, inland waters, coastal areas and the ocean, and restoring 30% of each of these degraded environments. Other targets relate to reducing flows of nutrients, hazardous chemicals, invasive species and reductions in food consumption and waste (JNCC, 2022). The strength of a more holistic approach is the ability to maximise benefits from time and financial investments, by recognising where action against one target will also support delivery of another target.

Despite source-to-sea approaches having benefits across the land to sea interface, benefits (and the cost of achieving them) are not always shared equally. For instance, actions to curb the majority of pollution and contamination in the marine environment needs to originate on land (e.g. nutrient influxes, bacterial loads, and litter), raising challenges in environmental justice, accountability, jurisdiction and the distribution of wealth and power. At a national scale we must overcome the barriers to inter-departmental coordination, but such challenges are particularly pronounced when source-to-sea flows cross international boundaries, highlighting environmental justice issues described by Gupta et al. (2023) and Rockström et al. (2023).

3.2 Guidance and principles

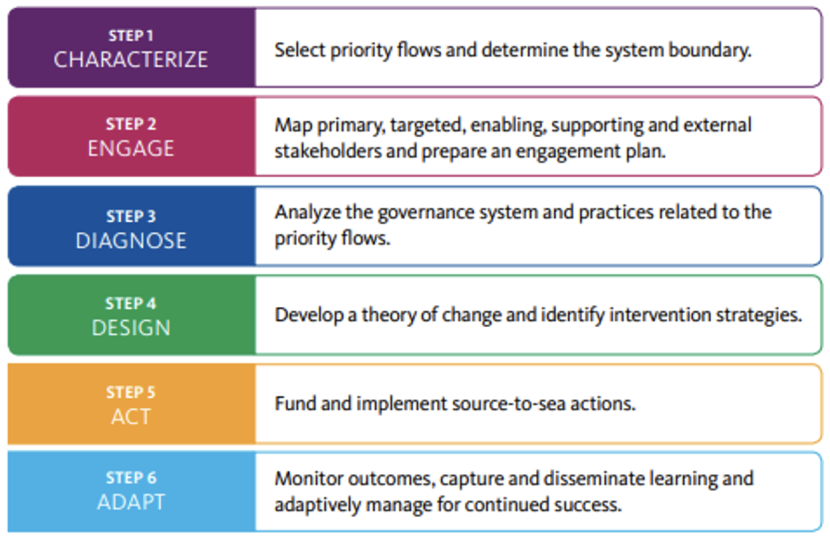

The secretariat for the Action Platform for Source-to-Sea Management is hosted by the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), with a source-to-sea department that have produced valuable resources for source-to-sea action and management, including a ‘Guide for Practitioners’ (Mathews et al., 2019).

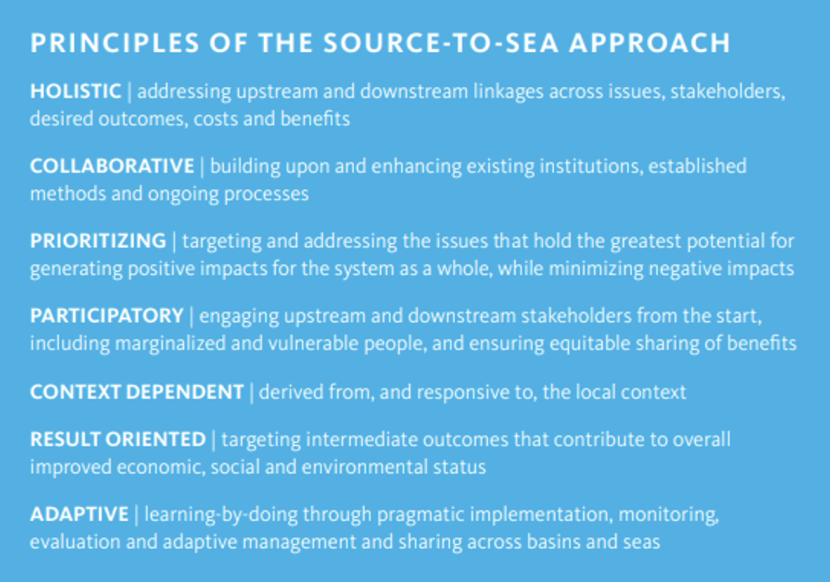

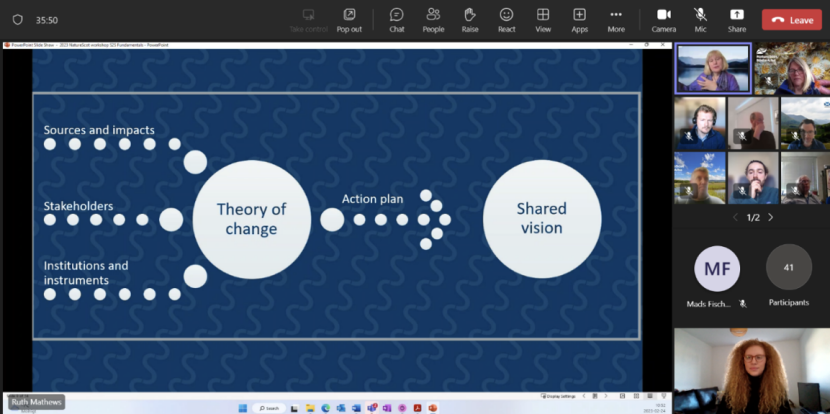

SIWI’s six-step guide to implementing a source-to-sea approach (Figure 4), and Principles (Figure 5) can be adapted to suit the scale and location of the project. For example, shorter term pilot projects demonstrating local and regional use in Vu Gia-Thu Bon River Basin, Hoi An (Mathews and Groeneweg-Thakar, 2020) and Lake Hawassa, Ethiopia (Weinberg et al., 2020), incorporated source-to-sea thinking in national governance. In 2011, Sweden created the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM), responsible for managing the sustainable use of Sweden’s marine and freshwater environments. SwAM’s remit is inclusive of watercourses, lakes, seas and fishing resources; they actively aim to work from source-to-sea, employing a holistic ecosystem-based approach to ensure management tools work together to achieve common goals from land to sea (SwAM, 2020). This is one example of structural change to improve implementation of holistic water management at a governance level.

A six-step diagram from practitioner’s guidance published by the global Source-to-Sea Action Platform (Mathews et al., 2019), showing a step-wise approach of (1) characterise flows, (2) engage stakeholders, (3) diagnose governance systems, (4) design interventions, (5) take action, and (6) monitor and adapt. These steps can be tailored to different geographical contexts and scales.

An extract box from practitioner’s guidance published by the global Source-to-Sea Action Platform (Mathews et al., 2019), showing principles which can be applied to different geographical contexts and scales.

3.3 Scottish policy drivers

The policy-mapping exercise included a high-level review of the extent to which strategic Scottish policies and strategies are, or whether/how they could be, promoting and delivering source-to-sea approaches. Policy drivers spanned government plans, strategies, published visions and some legislation. This was not an exhaustive exercise and reflects just one of many possible ways of grouping and characterising policy drivers. Figure 2 provides a visual depiction of those deemed to be cross-cutting and indicative of existing intent for connected governance approaches from land to sea.

Despite numerous existing policies, plans and strategies demonstrating good intentions for source-to-sea approaches, it is readily concluded that implementation is the exception rather than the rule. Some policy drivers give a very clear direction for integrated approaches (e.g. Scotland’s 3rd Land-Use Strategy); others are more subtle in their ambitions, but nevertheless provide an entry point for more ambitious and coherent governance across environmental systems.

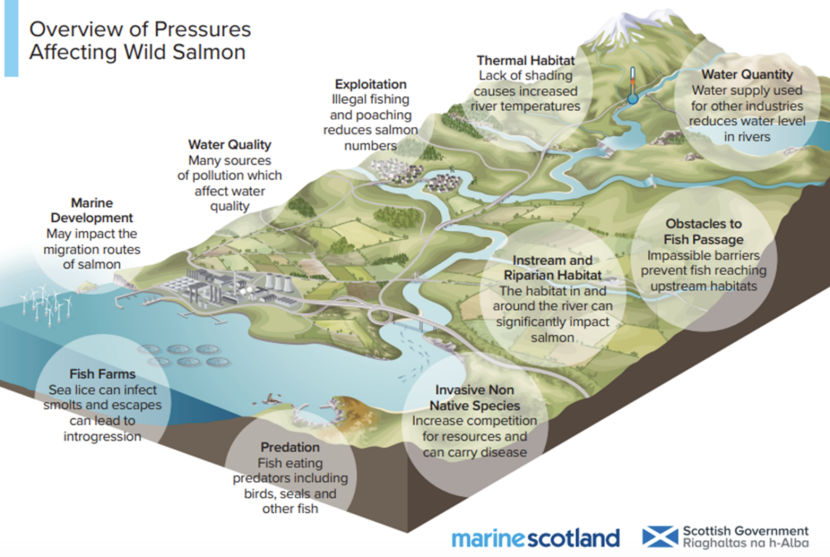

In almost all cases we identify actions that can clarify or strengthen policy intent and facilitate better or more consistent implementation. The clearest ambitions, and most of the best examples of successful implementation, arise where pressing issues are so obviously entwined in a biophysical source-to-sea flow as to be unavoidable in the search for solutions. For example, coastal bathing water quality is inseparable from land and urban-sourced inputs and their management, and the well-known migratory life-cycle of wild salmon makes them excellent exemplars for source-to-sea species conservation. This is not to say that even these issues have fully and consistently accomplished source-to-sea management approaches, such are the institutional and professional challenges of working across multiple departments, sectors and disciplines. The review of policy drivers and recommendations is available in Annex 1.

3.4 Solutions, challenges and enablers in implementing source-to-sea approaches

Identifying solutions, challenges and enablers will help us make progress in leveraging a source-to-sea approach to aid delivery of Net Zero, Biodiversity and Just Transition targets (among others), allowing us to maximise benefits from our actions and investments (public and private). There are many types of solutions and enablers to source-to-sea action.

This section details key messages emerging from workshops and other dialogue. A graphic recorder created images during the second workshop, to highlight key messages and enablers (Figures 6 and 7); these images are available for separate download.

3.4.1 Solutions

Solutions are broadly placed in several categories; nature-based solutions, technical, regulatory, behavioural, and circularity, although there is much overlap between these themes. Solutions can act independently but synergies can be found when different solutions are brought together.

Nature based solutions

- Ecological complexity supports carbon and nutrient cycling processes on land and in coastal and marine environments, as well as overall ecosystem resilience to challenges. Targeted restoration and recovery of species and habitats supports this, but can also be supported through multi-trophic food production systems that, for example, minimise and make use of nutrient and organic waste. Pilot studies could usefully evidence the benefits and profitability of multi-trophic and regenerative agriculture and aquaculture.

- Source-to-sea flows from our food systems should be a fundamental environmental management issue, for example minimising fertiliser inputs and targeting downstream solutions (e.g. habitat restoration or seaweed/shellfish production) where residual impacts remain. Seaweed cultivation may be particularly appealing for bioremediation of nutrients and other waste, due to diverse potential uses, as food, fertiliser and other products. However, upstream and downstream conditions have to work in harmony for system-wide outcomes.

- Protecting and restoring marine, coastal and lowland habitats, such as biogenic reefs, seagrass, saltmarsh and wetlands, can provide multiple benefits such as coastal defence, flood management, nutrient and contaminant uptake, and (blue) carbon storage.

- Urban surface water management that incorporates blue and green spaces, such as community allotments, riparian habitat buffers, green roofs, Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS), contaminant traps and other semi-natural and green infrastructure solutions, may be primarily designed for flood and waste management, but can also provide habitats, nature networks and wellbeing benefits.

- Land-use and management should avoid undermining, and ideally support, marine restoration and recovery efforts (e.g. avoiding or minimising excess nutrient discharge that seagrass beds are sensitive to (Boesch, 2002; Burkholder et al., 2007).

- Moving from static inventories of blue and green carbon, to monitoring of blue carbon sequestration, transport and storage characteristics across connected environments, could lead to further investment in nature restoration and catchment processes.

Technical solutions

- Connecting existing but separate marine, freshwater and terrestrial datasets would stimulate collaboration and scientific advances in necessary areas. Many flows from land to sea are natural (carbon, nutrients, water) but connected datasets combined with recent advances in modelling can identify harmful flow imbalances. Modelling and analytical data should be available outwith academia, to guide nutrient budgeting and other aspects of land management.

- Technical innovation and circular business design can tackle some problems at the source, e.g. washing machines capturing micro-fibres. However, waste is ideally (a) minimised, and (b) viewed a resource for re-use and even traded between businesses.

- Best use could be made of information technology, with an accessible database of example solutions, including additional benefits, implementation procedures, costs and timescales.

- Use scientific techniques to target efforts that can increase water quality, e.g. eDNA to track disease, sources of microbial contamination and invasive non-native species.

- Modern low-impact technical agriculture solutions (e.g. no-till; cover crops; intercropping; data-enabled chemical inputs), prioritising investment to regions and catchments with greatest risks to downstream environments.

- Target and minimise pesticide use through developing a better understanding of pests and diseases.

- Retro-fit water systems in houses and businesses to use grey water (capturing first flush) for toilet systems and implement slow trickle drains. Standardise these systems within building regulations for new builds.

- Digitising and real-time data for adaptive management (e.g. digital twins and Internet-of-things technology), LiDAR coverage for freshwater, coastal and marine environments may be able to help with this e.g.:

- To help farmers improve resource efficiency, including water.

- For heightened responses to combined sewage overflows, knowing where and when the problems exist.

- Monitoring environmental signals that can help predict and manage low-flow events.

- Modernising septic tanks and water treatment facilities.

Regulatory solutions

- Regulate for circular economy outcomes through business plans, such as for wastewater treatment facilities transitioning to view nutrients as a resource rather than waste. For example, chemical fertilisers could be regulated to contain a minimum percentage of recycled nitrogen, as adopted by Denmark. A ‘polluter pays’ principle could incentivise producers to avoid unnecessary fertiliser applications and to use techniques that minimise loss to the water environment. Financial incentives for nutrient recovery could also be built into this.

- Target 7 of COP15 (“Reduce pollution risks and the negative impact of pollution from all sources, by2030…”) was not agreed upon by the UN delegation, but there remains an opportunity for Scotland to take the ambition forward. For instance, we could elevate our ambitions to address nitrogen waste and nitrogen flows from agriculture, including rules on green cover-cropping.

- Management requirements for anaerobic digestion, including but not limited to methane.

- Build accountability for terrestrial and upstream actors affecting the condition of downstream and marine environments, through planning mechanisms, polluter pays schemes or environmental liability regulations.

- Ensure that River Basin Management Planning (RBMP) and Regional Spatial Strategies (RSS) give adequate granularity to their considerations. For example, small water bodies are often overlooked in broadscale monitoring and reporting, and therefore in regulatory and specific management activities. Small water bodies are important for biodiversity recovery, local flood defences and water retention.

- Emerging policies and regulations for agricultural, agri-environment schemes and biodiversity present great opportunities to raise and regulate standards for efficient water use and storage.

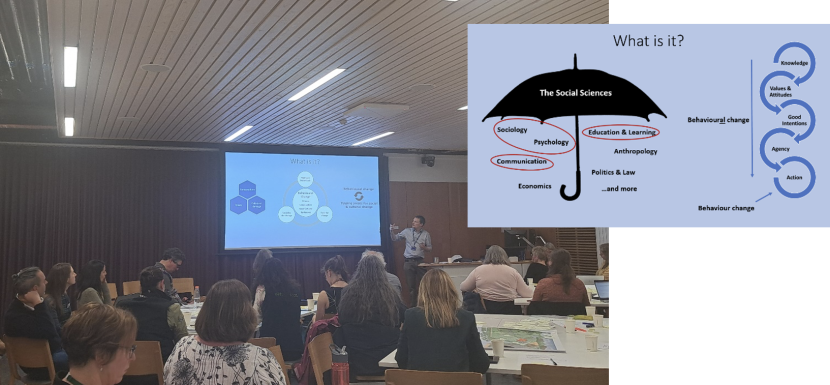

Behavioural change solutions

- Education could better represent nature-based solutions, driving behavioural change and a legacy of impact in future generations. Education is not just for school, and should also be filtered through businesses, work places and communities to ensure a multi-generational drive and commitment to nature. Examples of areas on which public knowledge is perceived to be low are: that dry SUDS are designed to flood; natural flood management; sustainable water use; sources of carbon and nutrient imbalances; and the day-to-day human choices with consequences across the land to sea continuum (beyond litter and plastic).

- Co-development of relevant solutions with communities and stakeholders can help to shift understanding and attitudes that can ease the pathway for new regulation or policy. Place-based approaches that recognise the different challenges locations face will be beneficial and help us to look at catchments as (a) food production units from source-to-sea, (b) habitats that some animals must be able to move through, and (c) underpinning the flow of water, with an appreciation of where and how it must be managed.

- Shifting behaviour across levels (consumers, retailers and suppliers) around packaging is necessary, to reduce sources and to make best use of unavoidable waste as a resource, thus minimising waste in the environment and the risk of downstream pollution. People need help to better understand what can be recycled and how. Increased collaboration between producers, environmental charities and education can facilitate this.

- Linking consumption and waste patterns (generally, not just plastic) with ecosystem resilience to provide a better societal appreciation of the need for behaviour change (i.e. better communicate outcomes of IPBES work on indirect drivers of biodiversity loss).

- Labelling/standards/accreditation schemes could also reflect source to sea outcomes i.e. incorporating nature-based solutions and whole system benefits into food systems and land use management. For consumer awareness, labelling schemes should be bolstered by communication (not marketing) campaigns.

- Move away from short term fixes and communicate the long-term scale of economic and social investments. Public and private investments should be based on building resilience instead of reactive spending.

- Price is often a strong mechanism for changing behaviour. Mandatory charges on certain goods, e.g. disposable coffee cups, can be effective quickly, but can also enable the formation of better long-term habits.

- Showcase businesses that are doing well; good practice should be rewarded.

- Help consumers align product quality with environmental sustainability and health outcomes, helping shift consumers demands to ‘less but better’ (e.g. more sustainable meat and fish options). This will help to drive the supply / demand cycle for more sustainable, regenerative and connected farming from land to sea.

- Allotments and local food cooperatives can improve understanding around seasonal production and connect people with the food they eat, but also present opportunities to engage people in a broader (source-to-sea) understanding of food system impacts.

Circularity solutions

- Focus on transitioning from ‘waste to ‘resource’, particularly regarding the reuse and recycling of excess nutrients. Many examples of circularity are embedded within solutions under other categories above.

- Consistent segregation of waste/ by-products, encouraging public confidence that recycling is actually happening (countering media reports of poor implementation in recycling centres).

- Local recycling of fishing nets and gear, connected to nascent business opportunities for their re-use/recycling, linking to a behaviour change that encourages fishers to donate spent/damaged nets.

- Provide guidance and advice for circular water management and effective water storage, recognising the need for tailored place-based solutions. For instance, irrigation pools in agriculture should help efficient water use through different seasons (also helping with nutrient management and other run-off issues, and/or flood or drought prevention elsewhere in the system).

- Reinvigorate producer responsibility in circular economy approaches. This will require increased collaboration and cooperation between businesses, innovators and investors to move waste up the value chain. It is important to create and incentivise markets for unavoidable waste.

3.4.2 Challenges

A key challenge to overcome is ensuring opportunity for coordination and collaboration between different departments, divisions and specialisms of environmental policy, management, regulation, and conservation practice. The need to structure work and organisations into manageable and definable chunks has led to teams and work plans focussed on agriculture, or on forestry, upland management, coastal habitats or issues that are specific to the marine space. With the exception of a few specific topics (e.g. salmon conservation) that can unlock dialogue across these areas, all too often the inherent connectivity of these environments is overlooked.

There are risks that issues fall between the cracks of different management and regulatory systems, such that an action or inaction in one part of the system undermines policy or action in another part of the system. There are also missed opportunities to work together, to gain efficiencies and synergies in outcomes and spending, in both preventative measures and the growing sphere of nature restoration. Of course, there is also the likelihood that some of the benefits of positive interventions go unmonitored or unrecognised, by purely focussing on the immediate environment around an action. It may also be possibly to optimise interventions and achieve greater funding and public support if the full upstream-downstream spectrum of benefits is recognised.

Many of the additional challenge areas below, identified through workshops and dialogue, have roots in the silos of administrative structure and institutional culture that have formed around us.

Communication

- The earth, freshwater and marine sciences, natural and social, often do not communicate effectively, generally working in different units, addressing different questions using different language.

- Efficient communication of research and policies needs to be extended to communities, business sectors and others to ensure inclusivity, understanding and implementation, and to enable cross-sector and cross-discipline collaboration.

- Many of the issues are out-of-sight to most people, or otherwise too intangible (unlike large pieces of litter) for it to be intuitively obvious how distant actions and choices (on land, in homes, at work, and more) are manifesting in a geographically separate impact. Great communication and engagement techniques can overcome these hurdles; insights from the psychology and sociology of influencing people can help.

Regulation and incentives

- Recognition of connectivity between upstream-downstream environments mainly exists at a strategic level and needs to be better implemented. The scope for efficiencies, multiple benefits and positive long-term outcomes ought to attract voluntary action, but to build momentum and accelerate toward these outcomes may require some initial incentives and regulations. However, these can be time and resource intensive to establish, so targeted effort is needed. This may be helped by identifying issues for which cross-departmental strategies, policies, stakeholders, and communities can be most easily aligned with common goals.

- The impacts of excess nutrients, contaminants and microbial activity in wastewater flows and land run-offs are likely to be temporally and spatially variable. Blanket regulatory instruments may therefore not be appropriate, requiring a more nuanced, data-led and real-time approaches for a proportionate solution.

- The approach to designation of shellfish protected areas may limit the opportunities for the aquaculture industry to expand. The relatively blunt tool limits capacity to identify the type and source of contamination, and therefore the associated risk. Consequently, the opportunities to address problems at source are limited, but also the opportunity to identify potential production sites in areas of lower water quality. This includes the potential for shellfish production for purposes other than human food production, which may allow for the sustainable expansion of the sector while harnessing the ecosystem services of bivalve filtration feeding to improve local water quality.

- Markets for nature-based solutions (e.g. carbon and nutrient trading) have huge potential to help plug the funding gap for nature restoration and associated carbon sequestration, among other benefits. However, to ensure consistency, fairness and to guard against ‘greenwashing’ these need to become regulated, and with simple enough structures and processes to be governed from outside financial institutions. A source-to-sea approach to green investment will mean unlocking the opportunities for upstream-downstream flows of investment that reflect the relationship between those taking action and those benefitting from or impacted by that action.

- It may be questioned whether the principle of ‘polluter pays’ for remediation of impacts has been lost or marginalised, and whether it can be given a stronger foundation in legislation and associated monitoring and enforcement.

- The short to medium term business costs of inaction may compare favourably to the costs of action to address the climate-nature crisis. In these situations, (a) what action needs to be forced by regulation, and (b) how can we best incentivise investment for long-term outcomes?

- SUDS (sustainable urban drainage systems) guidance is available but poorly or inconsistently applied or regulated, with poor recognition of their multiple benefits when done well.

Research, innovation and data (technical and academic)

- Better understanding is needed of the fate of carbon when transported from land to sea (whether it is lost to the atmosphere or stored in marine sediments; for the latter, understanding vulnerability and sensitivity to re-release is also important).

- Impacts on human health and well-being are hard to directly associate with environmental variables, particularly when trying to showcase positive health benefits of access to nature-rich water environments.

- Distribution of microplastics and related toxins in fauna and humans and understanding population-level (rather than individual) effects, are not yet well understood.

- Effects on food-webs are complex, and consequences for specific species and habitats are not always predictable. There is a risk that the science gets stuck trying to resolve points of detail rather than concentrating on cruder (but reliable) indicators of ecosystem health. Related to this are fundamental challenges about the burden of evidence required to trigger regulatory interventions.

- Car tyres degrading and the breakdown of larger plastics into microplastics were identified as challenges of note, but limited scientific detail.

- Innovation is expensive and requires investment. For example, high fertiliser costs should drive innovation for more cost-effective and low-impact seed treatments.

- Terrestrial, freshwater, coastal and marine data sets and system models are often as fragmented as the governance processes. Bringing datasets and models from these different environments together, with functionality to analyse biophysical flows and related impacts via the water environment, is an important challenge for developing a useful evidence base and decision-support tool.

- Including and accelerating the delivery of quality-assured private sector and academic data into publicly accessible repositories, to support responsive and adaptive management. The costs of data management and any concerns about data sensitivity and confidentiality will need to be addressed.

A graphic illustration from our second source-to-sea workshop, displaying key messages on the source-to-sea approach, including solutions, policy drivers and multiple benefits. This image was produced by artist Jenny Capon.

Full size graphic illustration of key messages on the source-to-sea approach.

A graphic illustration from our second source-to-sea workshop, displaying key messages on enablers for the source-to-sea approach, including funding, collaborations and creative engagement. This image was produced by artist Jenny Capon.

Full size graphic of key messages on enablers for the source-to-sea approach.

3.4.3 Enabling actions

Primary enablers to implement a source-to-sea approach, emerged from workshop discussions under the following themes: advancing data, evidence and shared knowledge; behavioural change; skills and ways of working; natural capital approaches; stimulating investment; and enhancing cooperation and collaboration. The graphic recorder also developed imagery that focusses on enablers (Figure 7).

Advances in data, evidence and shared knowledge

In relative terms, the general health of Scotland’s water environment is often good, but there remain opportunities to do better and there are risks to address, to improve economic, health, social and ecological conditions associated with rivers, lochs, estuaries and seas. Existing scientific reporting can identify some pressures on the source-to-sea system that create imbalances in natural biophysical flows and introduce other unnatural and harmful flows. However, (a) standard national and regional surveillance designed for broadscale reporting may be of insufficient spatial and temporal resolution to identify local or temporary issues, or to inform the detail of a management intervention, and (b) we are limited by the fragmentation of data and modelling systems across different environmental units across the land to sea continuum. Better understanding and addressing these two key limitations would enable a step-change in source-to-sea approaches. These may be further enabled by development of new indicators, for environmental receptors but also for signalling effects on local communities and businesses.

Better connection and coordination of science across the UK and globally would be beneficial, for collaborative approaches and the avoidance of duplicated effort. Open access tools, models and datasets, and consistent methods, to assess flows across the land – sea interface are important as decision-support tools and for proof-of-concept to unlock policy and regulatory progress. Through this project, it was discovered that institutions in Northern Ireland, England and Scotland all had common scientific goals but were working in isolation of one another. The time is right to convene scientific minds across borders, in collaboration with policy contacts and policy influencers, to give direction to the supporting science and to ensure efficiency and timely process through coordinated and well-known programmes of work. Scientific tools may well need to adapt to suit the conditions and data availability in different national and regional contexts, but ideally would occur within a common framework.

We cannot address every issue at once, so some prioritisation is necessary, finding the right balance between the ease, cost and impact of available solutions. Imperfect knowledge should not be allowed to hamper informed progress, but we should also identify where better knowledge is most important and achievable, so that we can instigate an iterative cycle of improving governance.

Behavioural change

Behaviour change is identified above as a solution in its own right, but is also an enabler of broader change. It should be sought at every level (individuals-communities-businesses-institutions) to achieve a holistic approach to environmental management and to fully address the climate-nature crisis. A mix of sociology, psychology, communication and education are required. Behaviour change is the outcome of a longer process of behavioural change; this is the journey from knowledge to action; it does not exist in isolation, but interacts with and catalyses related changes in politics, economics and business. Behavioural science recognises different levers (e.g. Leakey, 2022): Motivating individuals can be done through education and knowledge, experience and emotional triggers (first hand experiences or through engaging literature, arts and visuals), or a financial incentive or disincentive. However, to achieve lasting motivation and change many other enabling conditions are necessary, and social influence can play a large role here. People are often influenced by those around them, and we need visibility of positive change to reach a tipping point that triggers shifts in social norms and larger scale societal change. Some hurdles may remain though, so we must also recognise where regulation, financial support, technology and access can help ease the change.

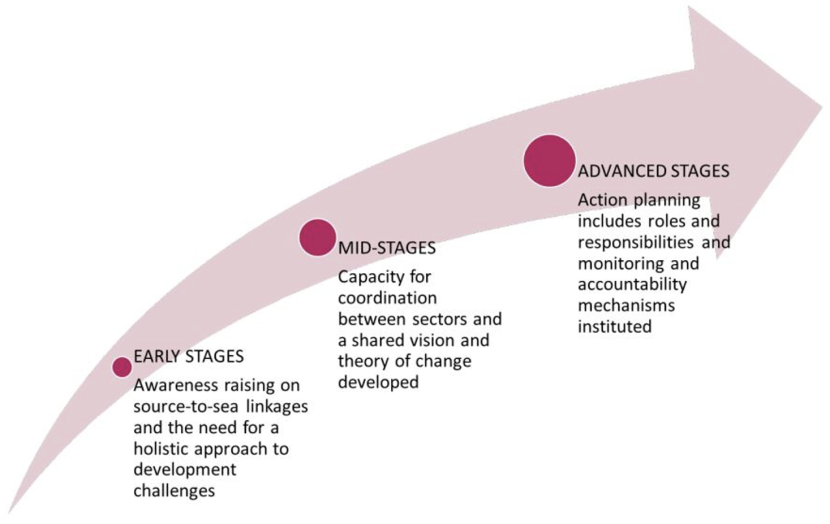

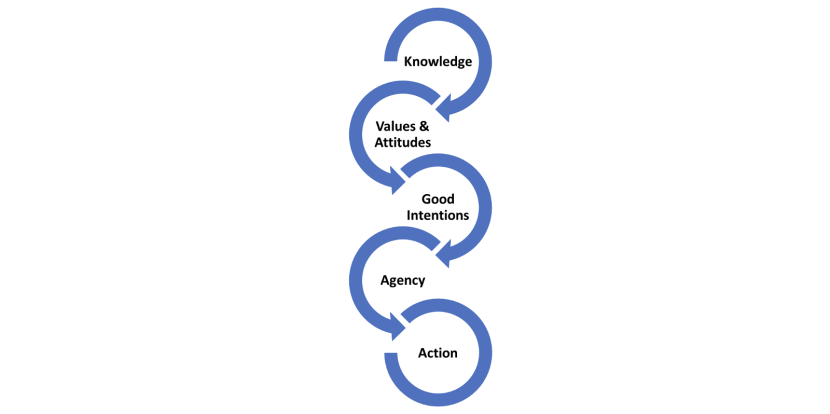

Ocean literacy is a concept well aligned with that of behavioural change, with a dedicated outcome in Scotland’s Blue Economy Vision (Scottish Government, 2022a), but will require multi-sector action to deliver. Increasing ocean literacy is key to society’s understanding of the impacts our actions can have on downstream environments. However, ocean literacy is about much more than knowledge and understanding, extending to shifts in public attitudes and actual actions and choices in daily life (see McKinley et al., 2023). The accumulation of these changes has its own impact, but also influences the ‘social license’ and consumer demands to which governments and businesses respond, respectively. Initial progress in this can help move us through the ‘source-to-sea management readiness levels’ described in practitioners guidance (Mathews et al., 2019) (Figure 8). Mixed levels of ocean literacy in Scotland (BMG Research, 2022) highlights the need for continued efforts to educate, communicate and influence people about the impacts of upstream activities on downstream environments, and potential solutions.

A diagram of three sequential levels of source-to-sea readiness (Mathews et al., 2023), from awareness raising, to building capacity, and to action planning.

Education and knowledge can be gained from schools, colleges, universities, environmental campaigns, the news, media, participatory engagement of communities, and more. Multi-tiered learning will have the most effective outcomes i.e. children and adults engaging with the same topic. Environmental charities are the most active advocates in this space. For example:

- Keep Scotland Beautiful’s ‘Upstream Battle’ Campaign took a source-to-sea approach to the most tangible of negative land to sea flows: marine litter. They sought to avoid the common issue of focussing on symptoms in coastal/marine environments, instead looking upstream to the source of litter for the Tay and Clyde catchments (Keep Scotland Beautiful, 2023).

- Surfers Against Sewage have raised awareness of large volumes of contaminated effluent, often from sewage or agricultural and urban run-off, entering the UKs rivers, estuaries and marine waters. Campaigns and tools, such as the ‘Safer Sea and Rivers Service’ (Surfers Against Sewage, 2023), have highlighted the harmful effects of poor water quality to society and the extent of the challenge.

- The Marine Conservation Society also sought to influence policy across the land-sea interface, in particular targeting the flow of chemicals (‘Stop Ocean Poison’) and the transport of micro-fibres (‘Stop Ocean Threads’).

- Fidra have developed campaigns on source-to-sea issues as diverse as ‘Sewage Free Soils’, nurdles, artificial grass, salmon farming and various chemical contaminants.

These charities provide educational resources, communicate issues and solutions effectively and influence behavioural change by moving people through the steps from knowledge to action (Figure 9). Education, communication, and access are valuable mechanisms that third sector organisations and some academic outreach use to stimulate behavioural change, that could be better adopted more widely or to target other issues. Working with relevant local interest groups, such as surfers, wild swimmers and kayakers, can be a powerful way of building community support and amplifying source-to-sea messages. Identifying opportunities for these groups to engage meaningfully with policy development or specific decisions are valuable, for voices to be heard and management processes understood.

Behaviour change (human actions and choices) is part of the solution to source-to-sea issues, and can act synergistically with changes to governance or economic systems. However, people often require more than just knowledge to make the leap to behaviour change, so we often need to help them shift their attitudes, develop good intentions or find agency, before they will actually make behaviour changes. This process can be referred to as behavioural change. There is also an important sociological element, as people are heavily influenced by their awareness of the actions and choices of people around them.

Behavioural responses can also be shifted through collaborative story-telling and the arts and can be done in ways that ensure underpinning scientific integrity is not lost. This may be through books, art, social media, or films. Increased collaboration between artists and academia, government, private and public bodies, provides an accessible method of communication that can reach new audiences in new ways, making it an incredibly useful tool for social change. Whether through the arts or other routes, funding for inclusive communication and engagement activities could be included more regularly in association with different projects, particularly in the public and academic sectors. A source-to-sea ‘story’ to our environmental challenges and solutions has the potential to reach a greater variety of people than campaigns on a single-issue or narrow geography, also supporting a greater appreciation of complex realities that are often overlooked.

Skills and ways of working

To transition to a more holistic approach, we must assess the skills and workforce resources required to deliver the strategic aims of cross-cutting policies and strategies. Many useful skills for source-to-sea implementation may be practical, technical or academic, and it would be useful to identify and prioritise skills development and workforce plans in these areas.

However, ‘softer skills’ are also required to generate an institutional and collaborative culture across organisations, to support the paradigm shift to less fragmented ways of working. People have a tendency to be comfortable in specific knowledge ranges and departmental and disciplinary silos. Moving beyond this requires a change in attitude at all levels and across all sectors, not just in our personal lives but in our work. The time and resources to come together to discuss and resolve cross-cutting issues is often not built into the current work systems. Source-to-sea thinking is just one possible vehicle of such change, but which seems to have a compelling and inspiring narrative that can stimulate a change in mind-set. Even in the workplace, creativity and an openness to new ideas can engage and inspire people to strive for a better future.

Natural Capital approaches

Natural capital research, data and tools are more advanced for terrestrial than marine assets, presenting an obstacle to realising, and sustaining, the full potential and value of our ecosystem services. A majority of current models are focussed on siloed environments and are therefore unable to account for the source-to-sea benefits of actions in any one part of the system. The current Natural Capital Asset Index (NCAI) for Scotland (NatureScot, 2022a) is a useful tool for tracking broadscale changes in the capacity of Scotland’s terrestrial natural assets, to provide benefits to people. This index includes freshwater environments and some coastal habitats, but not marine environments. A feasibility study for building a marine natural capital asset index for Scotland (Tillin et al., 2019) found that while a NCAI for the marine environment is technically feasible there are challenges to making progress. Key issues include differences in the spatial and temporal resolution of terrestrial, coastal and marine data, resulting in disjointed datasets that do not easily communicate with one another. In the longer term, greater coherence and compatibility between terrestrial, freshwater and marine data sets may make a single connected NCAI possible; as data improves it may also be possible to have regional-scale indexes that are more useful for informing management. Regional indexes and mapping tools would likely be better suited to displaying land to sea connectivity and would enable an influence on regional policy and management processes.

In the meantime, collaboration within and between organisations across the land – sea interface (public bodies, research, communities), could develop models of biophysical flows that can connect separate terrestrial and marine indices, accounts and maps of natural capital. This should aim to allow interrogation of how different flow scenarios and interventions would affect upstream/downstream assets of nature and the benefits they provide to people.

NatureScot, in partnership with Liverpool John Moores University, are developing a Landscape Natural Capital Decision Support Tool that will be a user-friendly, non-technical web app designed for organisations, landowners, and other environmental practitioners to evaluate how best to use their land. Building on scientific knowledge and an adapted version of the EcoservR model, it will encompass environmental and social pressures and demands so that the user can make place-based decisions. This tool will enable practitioners to realise the best use of their land for maximum environmental benefits. There is the potential to expand the remit of this tool in further development phases to include coastal environments and habitats; such an adoption of source-to-sea principles could be transformative for managing upstream-downstream pressures within different catchments.

The benefits to human health, both physical and mental, of access to quality ‘blue space’ is increasingly accepted (e.g. World Health Organisation, 2021; BMG Research, 2022), but hard to measure and therefore difficult to use as a lever for positive change. Upstream blue spaces, such as rivers and canals have also been found to have positive health effects (McDougall et al., 2022). Wellbeing effects are also likely to be influenced by access, culture and location, so there are geographic drivers to variable benefits and place-based influences. Pan-European research initiatives, such as Blue Health, are trying to identify links between urban blue spaces, climate and health to inform the design, planning and management of water environments (University of Exeter Medical School, 2020). Research associated with this project has developed a framework for evaluating the development of urban bathing water initiatives (Wuijts et al., 2022) to help link governance conditions to the development of attractive urban bathing water sites. Often poorer communities have more restricted access to desirable blue/green spaces, creating a social justice issue that compounds other drivers of health inequalities. Greater awareness of opportunities to delivery source-to-sea synergies between environmental and wellbeing outcomes should help to prioritise actions and investment.

Stimulating investment in nature and sustainability

A branch of natural capital thinking relates to stimulating private investment in nature. The National Strategy for Economic Transformation (Scottish Government, 2022c) aims to establish a ‘values-led, high integrity market for responsible private investment in natural capital’. This has been followed by the Interim Principles for Responsible Investment in Natural Capital (Scottish Government., 2022b), to steer toward a holistic approach to natural capital investments. Key aspects cover:

- Actions to deliver benefits for the environment, society and the economy.

- Investments and uses of natural capital benefitting public, private and community interests.

- Encouraging engagement between investors and land managers with communities.

- Open collaboration between investors and land managers, landowners and public bodies.

- Working across existing Scottish Government policies and aligning with the Paris Agreement and UN principles for Responsible Investment.

- Encouraging collaborative partnerships rather than sole private land ownership.

Woodland (Woodland Carbon Code, 2019) and peatland (IUCN, 2023b) carbon codes are examples of current markets that will continue to adapt and change as science and knowledge progresses in this area. Scotland currently has over 80% of the habitat restoration potential under both codes in the UK, with interest and investment opportunities even where commitments are long term (around 40 years). Private funding is trying to build in some permanence to their investments (i.e. protecting restored habitats to ensure a lasting legacy from investment). A saltmarsh carbon code and others are also in development in the UK. Nutrient trading schemes are also in development in some countries, which are inherently designed around a source-to-sea flow. These schemes can be either government or business led, but are ideally public-private collaborations that stimulate responsible investment, represent sustainable economic activity and help deliver public benefits.

To ensure these principles promote and enable a robust source-to-sea approach that helps address the climate-nature crises and contributes to inclusive social and economic benefits:

- Be explicit in promoting actions with upstream-downstream benefits. Encouraging open communication, cooperation and collaboration between land managers, investors, landowners and public bodies throughout a catchment / across the land-sea interface can enable diverse natural capital benefits to be realised.

- Ensure that the principles for sustainably and ethically managing carbon resources can be applied to the management of other resources as markets develop, i.e. if nutrient trading comes to fruition, this will help future proof the principles.

Private organisations run a higher risk of ‘greenwashing’ (perceived or real) and being seen as ‘green lairds’. Companies therefore want to protect their reputation, and we all should be motivated to ensure responsible access to emerging carbon and biodiversity markets (and potential nutrient markets). Overall, there are huge opportunities but also risks in the emergence and growth of green finance mechanisms, but steps are being taken to develop codes, standards and regulations to manage the risks accordingly.

More broadly, the private sector has a vital role to play in the adoption of a source-to-sea approach: from the fundamentals of their supply chain and circular economy outcomes, to environmental impact mitigation, investment in their natural capital dependencies, corporate culture and how and why they engage with stakeholders, communities and places connected to or affected by their business. It is important to consider levers of change at all stages in the life cycle of a product or service, from sourcing materials, to manufacturing, retail, consumers, household technologies, and wastewater treatment. Affected stakeholder groups are also wide ranging, from anglers, to seafood consumers, water-based and coastal recreation, biodiversity and more. Supply and demand for increased sustainability investment and innovation from organisations, industry and the government is growing. The Dornoch Environmental Enhancement Project is an interesting example of place-based investment in nature, as part of a more sustainable business model, and is detailed further in the case-examples section below.

Investment in nature is not just for the private sector though, and the Scottish Government have made a commitment and considerable investment of public funds to nature-based solutions, particularly for peatland restoration and woodland creation. Despite this, the funding gap for Scotland from 2021-2030 has been estimated at around £20bn (Green Finance Institute 2021). Public bodies do not have the capacity to finance all actions necessary to meet our environmental and societal targets, so collaboration with the private sector is key to unlocking funding for action. There are multiple funding schemes, some public-money and some a public-private blend, that aim to address the climate-nature crises:

- Nature Restoration Fund

- Marine Fund Scotland

- Scottish Marine Environmental Enhancement Fund

- Forestry grant scheme

- Peatland Action Fund

- Agri-Environment Climate Scheme

- Catchment restoration fund (in development)

- Green jobs fund

- Facility for Investment Ready Nature Scotland

The Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) acknowledges that transformational change is required across land, freshwater and seas by 2045 to meet the aims of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy. Priority themes span across the source-to-sea continuum: habitat and species, freshwater, coastal and marine, invasive non-native species and urban. More deliberately encouraging applications / actions that work across the themes could facilitate a source-to-sea approach through the core of this fund, to help optimise benefits from investments.

The Facility for Investment Ready Nature Scotland (FIRNS) addresses barriers to scaling investment in nature. It aims to: value and monetise ecosystem services derived from the restoration of natural capital assets and generate social and economic benefits that align with the Just Transition principles. Applicants are encouraged to co-create projects that share benefits with community interests, encouraging collaboration, communication and benefits across different sectors. The scheme aligns with the Interim Principles for Responsible Investment in Natural Capital, aiming to grow markets across rural, urban and marine settings. By creating a focus on the connections between markets (urban, rural, marine) FIRNS could stimulate more holistic source-to-sea management.

Funds focussed on specific environments (e.g. forestry, or agri-environment) still have the potential to recognise the upstream-downstream impacts / benefits. It would be beneficial to have funding for agricultural environments that specifically recognises the ecosystem services provided by upstream-downstream connections and focusses on the synergies/impacts between upstream-downstream biodiversity and food systems, i.e. agriculture and shellfish.

Enhancing cooperation and collaboration

To create positive change, management approaches and common goals need to be shared between sectors and supported and understood by communities. Community-based advocacy and action, alongside NGOs and the private sector are capable of stimulating source-to-sea collaboration and implementation, but to reach a critical mass of coordinated action it is often desirable to also have the support from public bodies and government. In particular, environmental practitioners, central and local government can provide valuable support for changes to policy and practices that alleviate negative source-to-sea flows (Mathews et al., 2019). Public and academic funding mechanisms are encouraging cross sectoral collaboration and communication, so we should ensure that these remain core priorities. By motivating actors to work not only across sectors, but across environments (land-freshwater-coastal-marine) synergies can be realised and more perspectives, solutions and funding opportunities can emerge for effective action, including monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Public and charitable bodies don’t always have equivalent financial resources to (some) businesses but can come together in (sometimes large and diverse) partnerships to build ambition and unlock funding opportunities to deliver exciting projects. These efforts need not be explicitly tied to the delivery of existing policy and often help give shape and detail to emerging and future policy. A prominent and current example of particular relevance to source-to-sea outcomes is the Riverwoods project, led by Scottish Wildlife Trust with a diverse suite of public bodies and other partners; further details are provided as a case-example in the next section.

Projects such as Riverwoods present opportunities to demonstrate and communicate the connections and flows from land to sea to different audiences. Proof of concept projects will generate more funding for source-to-sea action which can act as a mechanism for delivery across policies and strategies. We must consider the role of Riverwoods in connecting habitats and nature networks for biodiversity, coordinating actions from land to the sea and vice versa. Planning (terrestrial and marine), land-use strategies and the partnerships that drive them, should all recognise the shared relevance of such projects, to also share coherent policies that help address the climate-nature crises through implementation that is place-based but deliberately connected to seemingly distant but relevant environments.

3.5 Case examples

3.5.1 Further UK examples of connected action

There are several projects that provide great examples of connected action across (part-of) the source-to-sea continuum. These projects are the exception rather than the rule, so greater support and encouragement needs to be provided for source-to-sea management. Public bodies, including government, have an important role in stimulating greater implementation of source-to-sea action, to help accelerate and sustain action to address the nature-climate crises.

Garrell Burn (Scotland) – Local to Catchment Scale

A collaboration between North Lanarkshire Council, SEPA and George Leslie engineering contractors set out with an aim to return salmon to the Garrell Burn for the first time in over 100 years. This involved the re-naturalisation of the Garrell Burn from a canalised channel to a re-meandering burn with improved wetland habitat surrounding it and the installation of fish ladders below weirs (North Lanarkshire Council, 2022).

Further collaboration with the Clyde River Foundation has provided monitoring in the catchment that has identified salmon fry further upstream in the river, highlighting successful measures have been taken. The project and collaborations have also improved wetland habitat, community engagement and public access to the river, developing benefits across biodiversity and the community (North Lanarkshire Council, 2022).

This project delivered on aims to improve the river habitat of the Garrell Burn from ‘poor’ to ‘good’ under Scotland’s River Basin Management Plan (SEPA, 2022) and is a great example of relatively small-scale changes that can provide significant source-to-sea benefits for biodiversity.

Dornoch Environmental Enhancement Project (DEEP)

DEEP is an example of a local multi-sector collaboration for nature within Scotland, delivered through a partnership between Glenmorangie, Heriot-Watt University and the Marine Conservation Society. Native oysters were once abundant in the Dornoch Firth until overfishing in the 19th century resulted in population collapse (Marine Conservation Society, 2023), inspiring a shared vision to restore a native oyster bed to enhance biodiversity, improve water quality downstream of the distillery’s discharge and increase carbon storage/climate change mitigation. Following a proof of concept phase, the project aims to reintroduce four million oysters to the Dornoch Firth (McVeigh, 2023). Recent research also suggests oyster restoration can be coupled with sustainable fisheries management to provide economic opportunity while enhancing biodiversity in sea lochs (Kennon et al., 2023), while also providing the primary intended ecosystem services of bioremediation of waste and excess nutrients. This intervention is rightly preceded (as per the mitigation hierarchy) by Glenmorangie reducing impacts on water quality using a new anaerobic digestion plant. This reduces biological load to the Firth by 95%, which means that oyster bed restoration aims to filter the residual 5% (McManamon, 2021). Research on the carbon sequestration capacity of oysters is complex and ongoing, with early assumptions of their potential as carbon sinks being drawn into question, so it is important that restoration efforts maintain a broad view of diverse benefits.

In this collaboration, each party brought their expertise (funding, research and field work, community support and advocacy) to ensure successful delivery and communication of the work. Effective communication can alleviate the lack of general awareness regarding land to sea flows, i.e. how food and drink production on land is impacting food production and environmental condition in the marine and coastal space, and how both can work together to create a more balanced, sustainable and productive environment. This project showcases success and benefits of coming together across the land-sea interface to achieve a shared vision with multiple benefits for the environment, society and the economy. The whisky industry in Scotland generates billions of pounds in revenue every year and provides thousands of jobs throughout rural communities (Scotch-whisky.org, 2019). This industry also relies heavily on high water quality and quantity to produce the spirit; so this is also an example of a direct dependency of a business on the health of the natural environment.

Riverwoods

Riverwoods is built on three principles; collaboration, innovation and action, and is designed to contribute to the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration. The multiple benefits of riverbank woodland environments for people and nature are at the core of this work and there is an aim to form partnerships and collaborations with organisations and individuals to accelerate the pace of change (Scottish Wildlife Trust, 2021). Funding is diversified across public, private and charitable sources, and is attracting additional funding through the voluntary carbon market and Woodland Carbon Code (Ogilvy et al., 2022).

Riverwoods operates on a catchment scale incorporating deer management, forestry, rivers, beavers, and promoting nature-based solutions in ways that do not unduly impact agricultural production. Different types of woodland will be developed in floodplains, riparian zones and gorges. There are multiple benefits to river woodlands that the project aims to capture: improving water quality, drought adaptation, alleviating flood risks, storing and sequestering carbon, maintaining sustainable soil health and structure, conserving biodiversity and ecosystems and improving health and wellbeing. There is an emphasis in the evidence review for this study on ensuring the appropriate and strategic placement in catchments (Ogilvy et al., 2022), akin to ‘planting the right tree in the right place’ and taking a place-based and landscape scale approach.