NatureScot Research Report 1338 - Valuing the health and well-being benefits of the NHS outdoor estate in Scotland

Year of publication: 2023

Authors: Alison Holt1, Charles Cowap2, Natalie Johnson1 and Rhiannon Tudor Edwards3

1Natural Capital Solutions, 2Independent consultant, 3Bangor University

Cite as: Holt, A., Cowap, C., Johnson, N. and Tudor Edwards, R. 2023. Valuing the health and well-being benefits of the NHS outdoor estate in Scotland. NatureScot Research Report 1338.

Keywords

natural capital; health and wellbeing; NHS; outdoor estate; natural capital accounting; tools; ecosystem services

Acknowledgements

The research was commissioned by NatureScot with support from Public Health Scotland. Funding was provided by Scottish Government as part of the programme of work being taken forward to implement the NHS Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy 2022-26.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Emma McIntosh and Professor Mary Lynch for their contribution on the expert panel. The authors would like to thank Dr Catherine Lawrence for contributing to the final report. The authors would also like to thank Kalpa Pisavadia for production of Figure 5.

Summary

Background

Spending time in green space and access to green space for associated physical exercise, recreation and social networking provides benefits to physical health, mental health and well-being across the life-course. The NHS in Scotland own a considerable outdoor greenspace estate across 14 Health Boards, 7 special Health Boards and Public Health Scotland. The 7 special Health Boards have a special function which covers the whole of Scotland and one public health body which is legally constituted as a Health Board. These are NHS Education for Scotland; Scottish Ambulance Service; NHS National Waiting Times Centre; Healthcare Improvement Scotland; National Services Scotland; NHS 24; The State Hospitals Board for Scotland and Public Health Scotland. It consists of 4.7 million square metres of buildings often part of larger estates rich in greenspace, parks and woodlands. This land is part of the public realm and as institutional ground is, under Scottish Government draft regulations, to be included and considered in local authority open space strategies. This offers opportunities for moving hospitals, health and social care sites from downstream providers of acute and general care to upstream enablers of prevention through the provision of healthy environments and ecosystem services.

The importance of natural capital in delivering such health benefits is recognised by NHS Scotland in its Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy (2022-26). The strategy puts forward actions and targets to address climate change impacts, to achieve net zero carbon, and to enhance biodiversity in response to the climate emergency and the need for environmental sustainability, but also recognising that doing so will have a positive impact on human health. Fulfilling these actions will create opportunities for health co-benefits, reduction of health harms and can address health inequalities. It also emphasises NHS Scotland’s role as an anchor organisation, and the strategy sets goals to manage the NHS outdoor estate as a public asset for improvements in public health, and reduction of health inequities.

The opportunity and the challenge

Public Health Scotland and NatureScot have been working with Scottish Health Boards through the Green Exercise Partnership and four NHS Greenspace for Health Partnerships to help deliver infrastructure improvements and activate the outdoor estate. There is also an initiative to create a geospatial data base of the natural capital assets of the NHS Scotland outdoor estate. The remaining challenge is how to identify, measure and value these benefits and the costs of releasing and developing these existing and potential benefits in future. This will inform the opportunity to strengthen the NHS Scotland’s role as an anchor organisation. The aim of this project was to explore the development of a tool or set of tools that can quantify and value the health and well-being benefits related to the use of the NHS outdoor estate.

Our approach

We used a mixed-methods approach to establish a methodology for valuing the health and well-being benefits associated with the NHS outdoor estate. This was achieved through:

- A survey of key personnel in NHS Scotland which has informed an understanding of our proposed taxonomy of uses associated with the NHS outdoor estate.

- The development of a conceptual logic chain of the relationships between natural capital, activities in greenspace, health and well-being benefits and their value.

- A targeted rapid literature review of the scientific and grey literature to reveal metrics of health and well-being benefits and the value from activities akin to those that occur on the NHS outdoor estate.

- A consultation with academic health economists to discuss the appropriateness and robustness of the valuation methods identified in the review, and how NHS Scotland can best approach the valuation of these benefits across the estate and the data required.

Our findings

Survey of uses and users

A survey of uses and users has revealed a wide range of uses and users, although the predominant use across all user categories is walking. Future work could refine this use into the purpose and nature of the activity (e.g. walking in order to travel between buildings v walking as a stretching fitness activity v walking as a necessary component of another activity).

Use can be influenced not only by the natural physical nature of the outdoor estate, but also by facilities and specific initiatives that directly or indirectly support its use. Examples include cycling facilities, not only suitable paths and routes but also secure storage facilities and maintenance equipment. Uses can also be categorised by users and other stakeholders, site characteristics, awareness of potential and other drivers of participation.

The predominant uses identified by respondents included: walking, secure bicycle storage, active travel to and from work, picnic areas, informal recreational gardening, cycling, running, informal social gatherings, outdoor therapeutic interventions or rehabilitation and organised fitness sessions.

The survey has also shown a reasonable level of awareness of the potential of the outdoor estate, with scope to extend this and build on it in securing greater engagement with the outdoor estate. Other organisations, for example local authorities, health and well-being and other charities and local groups, are also involved in the use of the estate, and it should be possible to build on this in the development of future uses of the estate.

Relationships between natural capital and health and well-being

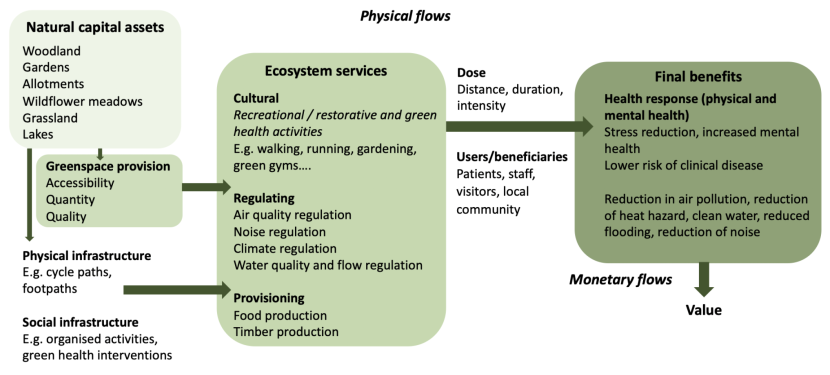

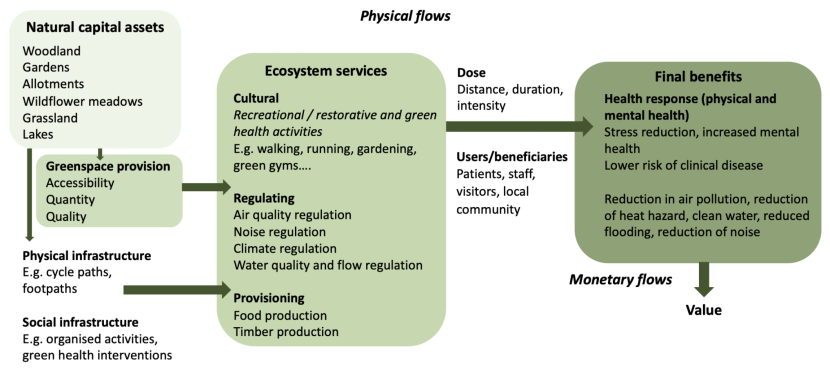

A conceptual model (natural capital logic chain, see below) has been created that describes the pathway to valuing the health and well-being benefits of the NHS outdoor estate.

The above diagram shows the relationships between the natural capital assets (different greenspace types e.g. garden or woodland); the cultural ecosystem services such as recreation or restorative green health activities (e.g. walking, running, birdwatching), and provisioning and regulating services (e.g. air quality, noise and climate regulation) that give rise to health and well-being benefits (increased mental health and happiness, lowering risk of chronic diseases, including health benefits from reducing pollution, noise, heat and flood hazards). It also outlines the beneficiary groups (patients, visitors, staff and local community users) and emphasises that the health and well-being benefits and the regulating service benefits to these groups will vary depending on the type, spatial location, accessibility, quality and quantity of greenspace, the infrastructure that is provided (e.g. cycle paths, footpaths) and organised activities available (e.g. green gyms or practical conservation). All these elements need to be measured to enable a valuation of the natural capital benefits, i.e., the greenspace characteristics as well as the human use and benefits.

The above diagram shows the relationships between the natural capital assets (different greenspace types e.g. garden or woodland); the cultural ecosystem services such as recreation or restorative green health activities (e.g. walking, running, birdwatching), and provisioning and regulating services (e.g. air quality, noise and climate regulation) that give rise to health and well-being benefits (increased mental health and happiness, lowering risk of chronic diseases, including health benefits from reducing pollution, noise, heat and flood hazards). It also outlines the beneficiary groups (patients, visitors, staff and local community users) and emphasises that the health and well-being benefits and the regulating service benefits to these groups will vary depending on the type, spatial location, accessibility, quality and quantity of greenspace, the infrastructure that is provided (e.g. cycle paths, footpaths) and organised activities available (e.g. green gyms or practical conservation). All these elements need to be measured to enable a valuation of the natural capital benefits, i.e., the greenspace characteristics as well as the human use and benefits.

Rapid evidence review

The rapid evidence review was used to find existing metrics that are used to value health and well- being benefits, that would be appropriate for use in the context of the NHS outdoor estate. The focus was placed largely on the cultural services in the review, because there are fewer metrics available at present and it is a fast growing area of research. Regulating services that give rise to health and other benefits are better studied and there are already good metrics available. The searches were limited to research and grey literature published in the English language between 2000-2022. One hundred and sixty-five studies met the inclusion criteria for review. Seventy percent of these papers were focused on quantifying the physical or mental health benefits of activity in a range of greenspaces (e.g. woodland, gardens, parks), and 30% were focused on valuing the benefits from recreational activity, gardening, conservation and ecotherapies.

Overall, the studies quantifying benefits find a positive link between activity in greenspace and an increase in health and well-being, but they are of mixed quality. The largest proportion of the studies focussed on general activities in greenspace, but the second largest on gardens or allotments. The review also demonstrated that there are relatively few studies that have tackled valuing the health and well-being benefits of activities in greenspace. The studies reviewed employ a wide range of valuation methods ranging from the Travel Cost Method (TCM), Contingent Valuation (CVM) and Willingness to Pay (WTP) to QALYs, DALYs and Social Return On Investment (SROI). This suggests that a broad range of valuation methods are applicable. The review has provided some scope for transferring these benefits to the NHS outdoor estate cases, but only in very particular circumstances.

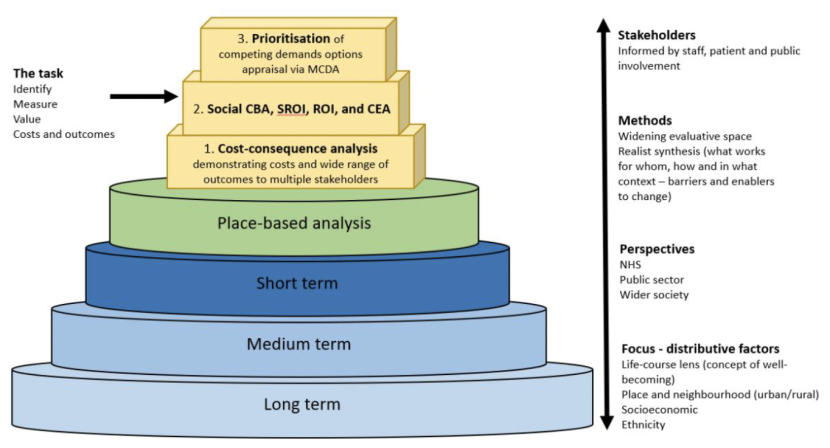

Proposed building blocks framework for evaluation and valuation of health and well-being benefits

Following a meeting with three leading experts in the field of Health Economics we have proposed a “building blocks” framework for the evaluation and valuation of the health and well-being benefits from the NHS outdoor estate. The framework provides a pathway towards a robust assessment of the benefits, ensuring that these benefits are considered fairly alongside other priorities in NHS estate business cases. The framework has been constructed recognising the importance of time-horizons in public health and preventative interventions. Many benefits to physical and mental health and the life-time health opportunity architecture of the population involve costs now and benefits many years in the future. It, therefore, encompasses short term metrics of e.g. greenspace use, as well as methods that will capture the longer term benefits. The framework is also place-based in accordance with guidance in the HM Treasury Green Book, which is linked to the concept of NHS estates as anchor organisations recognising the social, economic and environmental factors that help create good health within local neighbourhoods, playing a key role in addressing health inequalities. The framework supports that the NHS Scotland outdoor estate move from downstream providers of care to upstream preventers of ill-health and disability.

The framework is designed to capture qualitative and quantitative (non-monetary) valuation of the health and well-being benefits so they can be used in decision-making, recognising that it won’t be possible to estimate a monetary value for all of these benefits, and that monetary valuation is only one way of capturing these benefits. It takes a realist valuation approach understanding that socio- economic factors will impact on whether a green health intervention will work. It integrates the natural capital accounting approach and a novel health economics approach to measuring health and well-being benefits from the natural environment (borrowing methods from environmental economics).

The framework is an integrated and modular approach consisting of three steps:

- Step 1 uses a cost consequence framework that captures costs and impacts associated with the outdoor estate activities and interventions. This aligns with guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the evaluation of public health interventions which emphasises the appropriateness of cost consequence and cost benefit analysis, taking a wider intersectoral perspective on the identification, measurement and valuation of costs and benefits.

- Step 2 uses a social cost benefit, social return on investment (SROI) framework, centred on the NHS outdoor estate, for evaluating and valuing the benefits associated with it, using the Treasury Green Book as a benchmark.

- Step 3 is concerned with the prioritisation of competing demands at the whole estate level using multi-criteria decision analysis, for the assessment of competing demands on NHS estates.

Practical application of the framework

Data

Greenspace assets: Any approach to valuation will require data on each element (natural capital assets, ecosystem services (cultural, regulating and provisioning) and final benefits) of the conceptual model of the relationships between natural capital assets and health and well-being benefits outlined above. The spatial database of the outdoor greenspace at each of the Health Boards is key to understanding the potential to supply health and well-being benefits. This will aid assessments of quantity, quality and accessibility of these greenspaces and how it influences patient, staff and local community use. This is understanding supply in relation to demand both by physical location, but also considering the social and economic reasons that may make sites accessible and attractive or not. NHS estates will have to be carefully managed for the range of different uses and user groups. A spatial analysis of the greenspaces could inform zoning of the outdoor estate within larger sites. Data on the types of users attracted to the estate greenspaces could be gathered as part of an annual survey of well-being benefits related to greenspace (see below).

Use: Data is required on how the site is being used (e.g. gardening, walking, green gym, outdoor therapeutic interventions, bird watching etc) and by whom. We recommend a survey of use, by different zones at sites throughout the year, and a register of organised health interventions recording the numbers of participants involved in the activity. There are innovative technologies that can help monitor use (e.g. counters on footpaths and cycle paths, sensors on benches, innovative smartphone apps).

Health and well-being benefits: There is a requirement for primary data collection across a range of activities to understand the uses and benefits associated with the NHS greenspace beneficiaries, rather than using existing studies for benefits transfer (the available valuation studies are generally at the wrong scale and too generic for robust benefits transfer to the NHS outdoor estate). However, benefits transfer may be appropriate for specific green health interventions, such as therapeutic gardening, where activities are very similar and take place at a similar scale. Understanding the benefits and their value is, therefore, contingent on gathering data by survey. A well designed annual survey of well-being related to greenspace is recommended. This should also be used to gather important data on the users, such as user type (patient, staff, visitor or local user), gender, ethnicity and socio-economic circumstances. Spotting the gaps in users will enable NHS boards to take appropriate action to establish equality of accessibility.

The health and well-being benefits associated with the provisioning and regulating services can be captured using benefits transfer as in natural capital accounting. A good guide for economic methods is provided in the Defra ENCA ecosystem services data book.

Where to start?

Capturing the value of all the possible health and well-being benefits, across all activities and beneficiaries associated with NHS Scotland’s outdoor estate will be challenging. Consequently, it is sensible to focus initially on using the proposed framework to evaluate situations where there are relatively easy wins, while data is gathered for dealing with the rest. We suggest an initial focus on staff health and well-being (mental and musculoskeletal health), and some specific green health interventions (e.g. gardening and social and green prescribing) in relation to all users.

We also suggest testing out the framework on some pilot NHS Health Board sites and focusing on gathering data as recommended with a focus on different user groups, benefit types and green health interventions (as above) to create learning that can be rolled out across all the Health Boards. This will generate data on benefits transfer that can more easily be applied to other NHS estates.

Conclusions

There is no quick route to valuing the health and well-being benefits of the NHS outdoor estate in a robust way. There may be some quick wins using benefits transfer from other studies for specific organised health activities where there are known numbers of participants, or from very generic recreational activities in specific habitats (such as walking in woodland).

Primary studies using surveys will be necessary to quantify and value health and well-being benefits across a range of NHS outdoor estate activities. The most efficient use of resources would be to prioritise certain activities or user groups and run different projects on pilot NHS Health Board sites. The learning can then be applied to other sites and be used in a future valuation toolkit in the medium to long term.

Summary of recommendations

We recommend the following for a robust evaluation and valuation of the health and well-being benefits from the use of the NHS outdoor estate. They will also help NHS Scotland develop their role as an anchor institution, allowing the outdoor estate to contribute to prevention of illness and address health inequalities:

- Adopt a place-based approach with an awareness of the opportunities being different for urban and rural estate.

- Be aware of time-horizons for valuation and the role of discount rates.

- Employ a shift in thinking about hospitals and their estate as places of acute care to places with a role to play in prevention.

- Begin to gather data and monitor use of the green estate.

- Employ the proposed building blocks framework to valuation.

- An initial focus on benefits to the NHS workforce addressing mental and musculoskeletal health.

- Establish the concept of zoning the green estate for staff, for patients and visitors, for green parking, and for community activities using green estate land.

- Establish demonstration sites with built-in evaluation and the resources required for evaluation with outside links to those familiar with methods evaluation of costs and benefits.

- Deliver evaluations including academic publication in peer-reviewed journals as well as accessible web-based reports and infographics.

- Work collaboratively with experts in the field.

Glossary

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Anchor organisation |

An organisation which has an important presence in a place and is tied to a particular place through mission, physical assets and local relationships. Key to this is that the institution is tied to the well-being of the population and influences community health and well-being. Implicit from an NHS perspective is that the NHS has a responsibility to deliver community benefits through the way it operates. |

|

B£ST |

Benefits Estimation Tool. |

|

Biodiversity |

An abbreviation of ‘Biological diversity’. The variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems. |

|

Boolean operators |

Words like “and” and “not” which allow expansion of search parameters. |

|

CBA |

Cost-Benefit Analysis. |

|

CCA |

Cost-Consequence Analysis. |

|

CEA |

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. |

|

CICES v5.1 |

Common International Classification for Ecosystem Services. |

|

Cultural services |

Non-material benefits that can be obtained from ecosystems, such as physical health and well-being and spiritual enjoyment. |

|

CVM |

Contingent Valuation Method. |

|

DALY |

Disability Adjusted Life Year. |

|

DCE |

Discrete Choice Experiment. |

|

Ecosystem service |

The direct and indirect contributions of ecosystems to human well-being and quality of life. There are four categories of ecosystem services: Provisioning, Regulating, and Cultural. The term ‘services’ is usually used to encompass the tangible and intangible benefits that humans obtain from ecosystems, which are sometimes separated into ‘goods’ and ‘services.’ |

|

Ecosystem service flow /physical flow |

The flow of ecosystem services provided by natural capital e.g. tonnes of carbon sequestered or number of recreational visits. |

|

GIS |

Geographical Information Systems. |

|

GI-Val |

Green Infrastructure Valuation Toolkit. |

|

Green parking |

Semi-paved car parks that provide sustainable drainage, prevent the movement of soil and clogging up of sewer systems. Recycled materials are often used. |

|

Habitat condition |

The Biodiversity Metric V.3.1 uses habitat condition as one of the measures of habitat quality. It measures the variation in the quality of patches of the same habitat type against ecological optimum state for that particular habitat. |

|

HALY |

Health Adjusted Life Years. |

|

HEAT |

Health Economic Assessment Tool. |

|

ICECAP |

ICEpop CAPability Measure. |

|

InVEST |

Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-Offs. |

|

Likert scale |

A rating scale used in surveys to gauge opinions, values or perceptions. Respondents choose from given options and the responses can then be given a numerical score for numerical analysis. Invented in 1932 by Rensis Likert, America social psychologist (1903-1981). |

|

Local climate regulation |

The capacity of habitats / natural capital assets to cool the local environment and cause a reduction in urban heat maxima. |

|

Logic chain |

A natural capital logic chain shows the links between natural capital assets (their quantity, quality and location) and the ecosystem services and benefits they provide. |

|

MCDA |

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. |

|

Monetary flow |

The monetary value of the benefits that flow from natural capital assets. |

|

Natural capital |

Elements of nature that directly or indirectly produce value or benefits to people, including ecosystems, species, freshwater, land, minerals, the air and oceans, as well as natural processes and functions. |

|

Natural capital accounting |

Natural capital accounting is the use of an accounting framework to provide a systematic way to measure and report on the value of the stocks of natural capital and flows of ecosystem service benefits. It documents the natural capital assets, the physical flows of ecosystem services and the monetary flows (or value) of the benefits. It provides a net natural capital value by accounting for liabilities associated with maintaining the natural capital assets. This term is often confused with natural capital assessment, or the monetary valuation of ecosystem service benefits. |

|

Natural capital assessment |

Describing or quantifying natural capital assets, the benefits that flow from them and their value. Can include opportunities analysis for restoring or creating new habitat for enhancing the delivering of benefits. Provides natural capital evidence for integration into decision-making to improve natural capital management. |

|

Natural capital assets |

A distinctive component or grouping of natural capital components, including e.g. habitats, soils and air. |

|

Natural capital stock |

The store of natural capital assets on which humans depend (amount of freshwater, grassland or woodland etc). |

|

NEVO |

Environment Valuation Online. |

|

NICE |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. |

|

Noise attenuation |

The capacity of the land to diffuse and absorb noise pollution. Noise can impact health, well-being, productivity and the natural environment. |

|

ORVal |

Outdoor Recreation Valuation. |

|

PAMS |

Property and Asset Management Strategies. |

|

Present value |

Today's value of the benefits you expect to flow from a natural capital asset in the future. |

|

Provisioning services |

Characterised by the products obtained from ecosystems such as food, water and timber. |

|

QALY |

Quality-Adjusted Life Years. |

|

Qualitative assessment |

The descriptive and conceptual findings of non-numerical data. |

|

Quantitative assessment |

The collection and analysis of numerical data. |

|

Regulating services |

Any benefit obtained from the natural processes and functioning of ecosystems such as flood reduction, water quality, pollination or carbon sequestration. |

|

Sensitivity analysis |

A tool to evaluate the impacts of different assumptions and possible outcomes of a valuation. |

|

Spatial data |

Data that references a specific geographical area or location. |

|

SROI |

Social Return on Investment. |

|

TCM |

Travel Cost Method. |

|

VOSL |

Value of a Statistical Life. |

|

WELLBY |

Well-Being Adjusted Life Year. |

|

WTA |

Willingness To Accept. |

|

WTP |

Willingness To Pay. |

1. Introduction

Access to green space and associated physical exercise, recreation and social networking provide benefits to physical health, mental health and well-being across the life-course. The NHS in Scotland own a considerable outdoor greenspace estate across 14 Health Boards, 7 special Health Boards and Public Health Scotland. The 7 special Health Boards have a special function which covers the whole of Scotland and one public health body which is legally constituted as a Health Board. These are NHS Education for Scotland; Scottish Ambulance Service; NHS National Waiting Times Centre; Healthcare Improvement Scotland; National Services Scotland; NHS 24; The State Hospitals Board for Scotland and Public Health Scotland. It consists of 4.7 million square metres of buildings often part of larger estates rich in greenspace, parks and woodlands (Scottish Government, 2022a). This land is part of the public realm and as institutional ground is, under Scottish Government draft regulations, to be included and considered in Local Authority Open Space Strategies. This offers opportunities for moving hospitals from downstream providers of acute care to upstream enablers of prevention through the provision of healthy environments and ecosystem services.

Contact with nature, and specific nature-based or green health interventions, can deliver health benefits to patients, visitors, NHS staff and local communities. The importance of natural capital in delivering such health benefits is recognised by NHS Scotland in its Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy (2022-26) (Scottish Government, 2022a). The strategy puts forward actions and targets to address climate change impacts, to achieve net zero carbon, and to enhance biodiversity in response to the climate emergency and the need for environmental sustainability. This is alongside fulfilling its duty as a public body to deliver on biodiversity (Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004) and contribute to meeting the climate change target of net zero by 2045 (Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009). However, importantly in this context the strategy also recognises that fulfilling these actions will create opportunities for health co-benefits, reduce health harms and address health inequalities.

The strategy also emphasises NHS Scotland’s role as an anchor organisation. There is a need for the significant land and physical assets of NHS Scotland to contribute a positive influence on the social, economic and environmental factors that help create good health within local neighbourhoods, playing a key role in addressing health inequalities (Reed et al., 2019). NHS Scotland as an anchor organisation is a specific focus of the Place and Well-being programme within the Scottish Government’s Care and Well-Being Portfolio (Scottish Government, 2022b), and links to the Public Health Scotland Place and Well-being Outcomes (Public Health Scotland, 2022).

NatureScot along with Scottish Forestry, NHS Health Scotland and NHS National Services Scotland has been working with Scottish Health Boards through the Green Exercise Partnership to deliver infrastructure improvements and set up four NHS Greenspace for Health Partnerships to improve activation of the NHS estate. Public Health Scotland are currently creating a geospatial data base of the natural capital assets of the NHS Scotland estate. The remaining challenge is how to identify, measure and value the health and well-being benefits that the NHS outdoor estate generates, and the costs of releasing and developing these existing and potential benefits in future. NatureScot and Public Health Scotland would like to develop a tool or set of tools that can quantify and value these benefits. The aims of the project were to:

- Review the variety of existing uses of the NHS physical outdoor estate in Scotland for health and well-being benefit.

- Complete a rapid literature review of existing Natural Capital Assessment approaches or tools that include a health and well-being component relevant to urban developments as well as rural settings that would be appropriate within health care sites and services in Scotland.

- Provide recommendations on the appropriateness and robustness of these specific health and well-being approaches or tools.

- Devise a simple ‘Phase 1’ conceptual model that sets out the relationships between the natural capital assets of a greenspace, the ecosystem services that are derived from those assets, the beneficiaries of those ecosystem services and the health and well-being outcomes experienced by those beneficiaries.

- Recommend the inputs (the data) that will be needed for a tool to support the evaluation and valuation of the health and well-being benefits of NHS greenspace and the indicative costs of collecting/ collating that data.

- Recommend the outputs that will be needed from a tool to support the evaluation and valuation of the health and well-being benefits of NHS Greenspace.

This report first presents the results of the survey of uses and users that has informed a taxonomy of uses associated with the NHS outdoor estate (Section 2), it then sets out a conceptual logic chain of the relationships between natural capital, ecosystem services and the health and well-being benefits that need to be considered for valuation (Section 3). This is followed by the results of a rapid review of metrics used to quantify and value the health and well-being benefits akin to those that might occur from the NHS outdoor estate (Section 4). In Section 5 we propose a framework for evaluating and valuing the health and well-being benefits flowing from the NHS outdoor estate and explain the concepts that underpin this approach. The following section (Section 6) then outlines how this framework can be put into practice across the estates, outlining the data requirements that will take the NHS Health Boards closer to being able to value the health and well-being benefits, measures that are required for improving access, and areas to focus efforts to achieve greatest impact and quick wins. The conclusions and recommendations from this project are presented in Section 7, followed by suggestions for next steps for the broader initiative (Section 8).

2. Taxonomy of uses of the NHS Scotland outdoor estate

The work described in this section focuses on the development of a survey to capture current uses and users of the NHS Scotland outdoor estate. Preliminary semi-structured interviews were undertaken with NHS staff who were able to offer key interests and/or experience in this area. Information from these interviews was synthesised with findings from the literature review to develop an online survey for wider distribution through NHS Scotland.

2.1. The interviews

Online interviews were undertaken via Teams and Zoom on four occasions with eleven Health Service staff from a range of functions and regions. The outcomes of these discussions have been instrumental in identifying perspectives on the use of NHS greenspace for therapeutic and other purposes, the importance of strategic placement, the role of other agencies, bodies and organisations in catalysing green space initiatives and in identifying previous initiatives which, although discontinued in a number of cases, continue to be valuable sources of insight. We have also identified uses of greenspace which had not previously appeared in our background research.

2.2. The survey

The objective of the survey was to fill a gap in our knowledge about the extent and types of use and user on the NHS Scotland outdoor estate, focused on health and well-being benefits. The first steps in designing the survey drew on the literature review, in particular the identification of different uses and users identified across a selection of academic and grey literature.

The survey was initially designed on paper, reviewed with the project steering group and subsequently modified for delivery by LimeSurvey, the designated software for this project. Further modifications were then made in the light of initial online testing before the survey went fully live.

The questions in the survey covered:

- Respondent familiarity with the use of the NHS outdoor estate in Scotland for health and well- being purposes.

- Respondent relationship to the estate, as an NHS employee, volunteer or other user.

- The NHS Scotland Board or Boards referred to in respondents’ answers.

- Identification of existing uses, activities and facilities.

- Identification of uses according to the different user groups: Patients, Staff, Volunteers, Visitors, Local community uses and others.

- Extent or intensity of use according to NHS functional areas (for example medical speciality).

- Involvement of other organisations, focussed on local authorities, health and welfare charities, national agencies like the Forestry Commission, conservation and similar charities, local groups distinguishing those with a health focus, special interest, children and youth, early years.

- The extent to which health and well-being benefits of the outdoor estate are recognised within Property and Asset Management Strategies.

The survey went live on 27 February 2023, with a request for responses by 6 March.

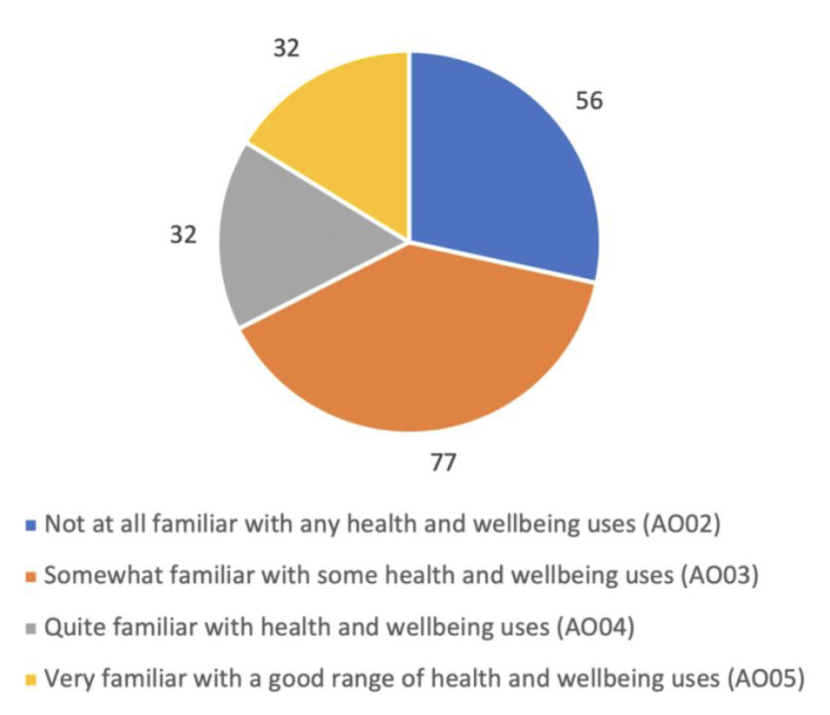

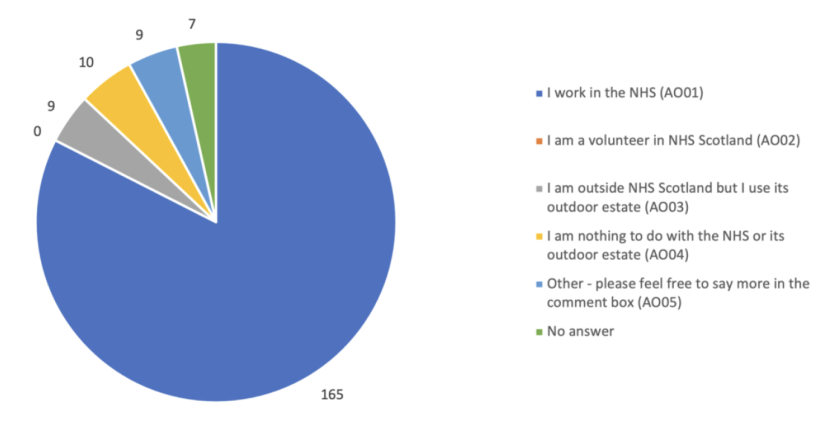

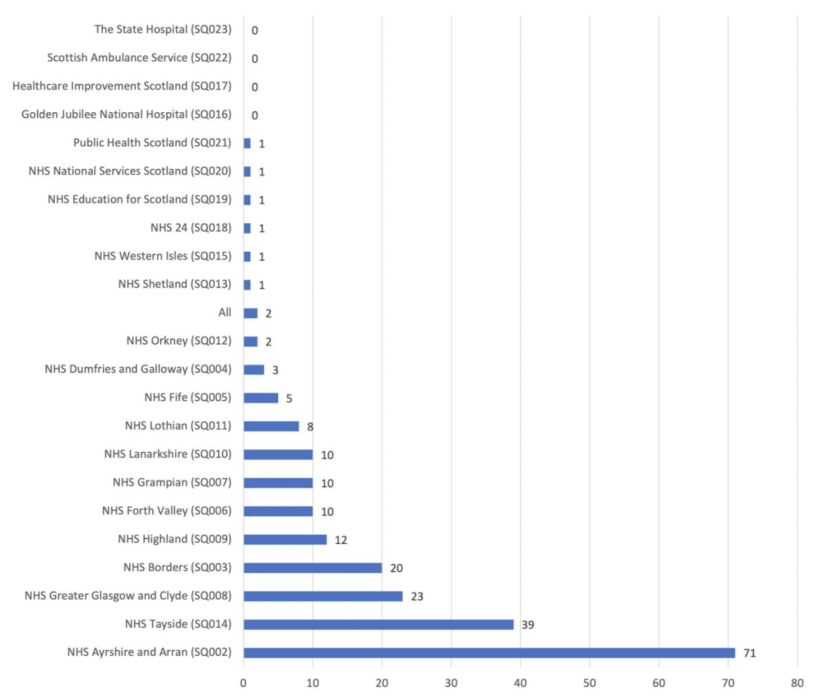

By 8th March, 200 complete responses had been received and these were drawn for analysis. Distribution of the survey was by email to NHS contacts with requests to distribute the survey link to further contacts. This does mean that we do not know how many potential respondents were contacted, nor anything about the nature of a population for sampling purposes. Nevertheless, we do have a profile of the responses we have received in terms of their self-perceived familiarity with the use of the NHS outdoor estate for health and well-being, and their role in relation to the NHS outdoor estate and the Scottish Health Board or Boards their answers relate to. Figures 1a, b & c provide summaries of these responses.

Figure 1a is a pie chart showing the responses of 197 people to the question “How familiar do you feel you are with the use of the NHS outdoor estate in Scotland for health and well-being purposes?” Of those respondents, 56 were not at all familiar with any health and wellbeing uses, 77 were somewhat familiar with some health and wellbeing uses, 32 were quite familiar with health and wellbeing uses and 32 were very familiar with a good range of health and wellbeing uses. Therefore most respondents were not at all familiar or merely somewhat familiar with the health and well-being benefits associated with use of the NHS estate in Scotland.

Figure 1b a is a pie chart showing the status of the 200 respondents to the questionnaire in relation to the NHS estate.165 of the respondents worked in the NHS. 9 did not work for the NHS but used the outdoor estate, 10 had nothing to do with the NHS or its outdoor estate. Most respondents (83%) work in the NHS. No volunteers responded.

Figure 1 c is a bar chart showing the responses of 221 respondents to a question that asked for the Health Board or Boards on which respondents had based their answers. 71 respondents had based their answers on NHS Ayrshire and Arran, and NHS Tayside accounted for 39 of the responses. Together these Boards accounted for half the responses. NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde accounted for 23 or the responses, NHS Borders accounted for 20, NHS Forth Valley accounted for 10, as did NHS Grampian and NHS Lanarkshire. NHS Lothian accounted for 8 and NHS Fife accounted for 5. No responses were received from the Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Scottish Ambulance Service and The State Hospital.

Most survey respondents were not at all familiar or merely somewhat familiar with the health and well-being benefits associated with use of the NHS estate in Scotland (133 of 200 respondents, Figure 1a). Most respondents (165/200, 83%) work in the NHS. No volunteers responded. There were small numbers in the remaining categories in the survey (see Figure 1b).

There were 221 responses to the question that asked for the Health Board or Boards on which respondents had based their answers (Figure 1c). NHS Ayrshire and Arran dominated, and along with NHS Tayside accounted for half the responses (110 responses of 221). At the other end of this scale, no responses were received from the Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Scottish Ambulance Service and The State Hospital. This may represent an onward distribution bias when considering the results in view of the snowballing approach whereby the survey was initially distributed to all boards.

Table 1 lists the uses, activities and facilities identified by respondents in rank order. Walking and secure bicycle storage were the two most prominent uses according to the number of respondents who identified each, followed by active travel to and from work (itself likely to be by walking or cycling – categories were not mutually exclusive).

Oddly secure bicycle storage was identified by 106 respondents, but cycling itself by only 55 respondents. Uses of a therapeutic nature included:

- Outdoor therapeutic interventions or rehabilitation – recognised by 21% of respondents, and ranked 9th.

- This was followed by Organised Fitness Sessions – 20% of respondents and rank 10th. It is not possible to tell directly from the responses whether the organised fitness sessions were set up with a medical therapeutic intention.

We also sought to distinguish uses by different groups: patients, staff, volunteers, visitors and others. Respondents chose from a shorter list of activities and their responses are presented in Table 2, with uses presented in rank order for each group. Not surprisingly walking is the highest ranked activity on each list, but there is then considerable variation between groups. The value of this information may be in enabling the selection of activities for further development and promotion according to local user priorities.

Table 3 summarises the intensity of use within different NHS functional areas, for example psychiatry, obstetrics, occupational health (a total of 18 higher order divisions of the work of the NHS). The functional areas were based on NHS workforce development groupings with some modification to avoid confusion in the light of steering group feedback. The overwhelming answer for all functional areas was that respondents did not know.

The Stand-Out groups in Table 3 are Health Promotion, Psychiatry, Occupational Health and Primary Care. This is based on the total number of responses in the two highest categories in the Likert scale used for this question. The Likert scale itself is reproduced in Table 3. One respondent stated that every NHS Functional Area made extensive use of the outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes including active use or promotion in treatment pathway plans with active monitoring of outcomes. This is not credible, and this response could be removed for future analysis. Nevertheless, its inclusion does not affect the relative position of the functional areas. Clearly some functional areas will struggle ever to make more than a minimal use of the outdoor estate for therapeutic or medical purposes, and these results may be helpful in supporting the top users to increase their use and share with others, and to encourage the next tier of users as to how they might engage more fruitfully with the NHS outdoor estate.

We were also interested in the involvement of other organisations in health and well-being activities on the estate. Table 4 summarises the results of this section of the survey.

Table 1. Uses, activities and facilities on the NHS outdoor estate: number of respondents.

|

Answer |

Count |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Walking (SQ002) |

157 |

78.50% |

|

Secure bicycle storage (SQ010) |

106 |

53.00% |

|

Active travel to/from work (SQ019) |

75 |

37.50% |

|

Picnic areas (SQ018) |

72 |

36.00% |

|

Informal recreational gardening (SQ013) |

69 |

34.50% |

|

Cycling (SQ005) |

55 |

27.50% |

|

Running (SQ004) |

49 |

24.50% |

|

Informal social gatherings (SQ036) |

43 |

21.50% |

|

Outdoor therapeutic interventions or rehabilitation (SQ024) |

42 |

21.00% |

|

Organised fitness sessions (SQ009) |

40 |

20.00% |

|

Meetings (SQ025) |

39 |

19.50% |

|

Active travel within estate (SQ020) |

38 |

19.00% |

|

Organised social exercise eg walking or wheeling club (SQ022) |

37 |

18.50% |

|

Nature conservation tasks eg tree planting or hedge laying (SQ026) |

37 |

18.50% |

|

Communal bicycle repair facility (SQ012) |

35 |

17.50% |

|

Visual arts display eg statues (SQ029) |

34 |

17.00% |

|

Artistic creation eg drawing and painting (SQ028) |

33 |

16.50% |

|

Teaching and learning (SQ017) |

31 |

15.50% |

|

Wheeling (SQ003) |

30 |

15.00% |

|

Bicycle hire/loan (SQ011) |

29 |

14.50% |

|

Community Food production (SQ015) |

26 |

13.00% |

|

Informal play (SQ007) |

25 |

12.50% |

|

Birdwatching or other wildlife study (SQ032) |

23 |

11.50% |

|

Formally organised social gatherings (SQ037) |

21 |

10.50% |

|

Outdoor exercise equipment eg green gym (SQ021) |

20 |

10.00% |

|

Corporate volunteering eg awayday activity (SQ033) |

15 |

7.50% |

|

Equipped play areas (SQ006) |

14 |

7.00% |

|

Changing rooms or facilities for sports or other strenuous activity (SQ008) |

14 |

7.00% |

|

Others, please specify below (SQ038) |

14 |

7.00% |

|

Care for animals inc beekeeping (SQ016) |

11 |

5.50% |

|

Foraging eg for mushrooms or wood (SQ027) |

11 |

5.50% |

|

Performing arts rehearsal or performance (SQ030) |

11 |

5.50% |

|

Organised sport (SQ034) |

9 |

4.50% |

|

BBQ or other outdoor cookery (SQ031) |

8 |

4.00% |

|

Informal competitive sport (SQ035) |

7 |

3.50% |

|

Commercial food production (SQ014) |

5 |

2.50% |

|

Outdoor medical consultations (SQ023) |

4 |

2.00% |

Table 2. User Groups and uses/activities/facilities in rank order. Number (n) of respondents who choose this option.

|

Patients |

n |

Staff |

n |

Volunteers |

n |

Visitors |

n |

Local community or others |

n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Walking (SQ002) |

128 |

Walking (SQ002) |

155 |

Walking (SQ002) |

74 |

Walking (SQ002) |

117 |

Walking (SQ002) |

100 |

|

Informal gardening (SQ012) |

56 |

Picnic areas (SQ016) |

72 |

Informal gardening (SQ012) |

50 |

Picnic areas (SQ016) |

52 |

Cycling (SQ005) |

45 |

|

Informal social (SQ027) |

49 |

Active travel (SQ017) |

64 |

Volunteering (SQ026) |

49 |

Informal social (SQ027) |

47 |

Running (SQ004) |

44 |

|

Picnic areas (SQ016) |

42 |

Informal social (SQ027) |

64 |

Conservation tasks (SQ020) |

37 |

Cycling (SQ005) |

35 |

Picnic areas (SQ016) |

43 |

|

Growing food (SQ013) |

40 |

Cycling (SQ005) |

63 |

Informal social (SQ027) |

36 |

Wheeling (SQ003) |

32 |

Informal social (SQ027) |

35 |

|

Wheeling (SQ003) |

32 |

Meetings (SQ019) |

45 |

Growing food (SQ013) |

35 |

Active travel (SQ017) |

29 |

Informal gardening (SQ012) |

32 |

|

Other exercise (SQ009) |

30 |

Running (SQ004) |

44 |

Picnic areas (SQ016) |

34 |

Running (SQ004) |

26 |

Other volunteering (SQ026) |

30 |

|

Arts creativity (SQ022) |

29 |

Informal gardening (SQ012) |

44 |

Arts creativity (SQ022) |

29 |

Informal play (SQ008) |

25 |

Wheeling (SQ003) |

27 |

|

Cycling (SQ005) |

24 |

Other exercise (SQ009) |

32 |

Active travel (SQ017) |

24 |

Informal gardening (SQ012) |

21 |

Informal play (SQ008) |

26 |

|

Conservation tasks (SQ020) |

24 |

Volunteering (SQ026) |

31 |

Cycling (SQ005) |

19 |

Volunteering (SQ026) |

21 |

Birdwatching (SQ024) |

22 |

|

Active travel (SQ017) |

22 |

Changing facility (SQ010) |

29 |

Other exercise (SQ009) |

19 |

Other exercise (SQ009) |

18 |

Other exercise (SQ009) |

21 |

|

Birdwatching (SQ024) |

22 |

Organised fitness (SQ011) |

28 |

Meetings (SQ019) |

19 |

Birdwatching (SQ024) |

16 |

Active travel (SQ017) |

21 |

|

Other Volunteering (SQ026) |

20 |

Wheeling (SQ003) |

25 |

Other nature study (SQ025) |

19 |

Other nature study (SQ025) |

14 |

Conservation tasks (SQ020) |

21 |

|

Other nature study (SQ025) |

19 |

Formal social (SQ028) |

20 |

Running (SQ004) |

18 |

Playground (SQ007) |

13 |

Playground (SQ007) |

20 |

|

Organised fitness (SQ011) |

17 |

Growing food (SQ013) |

19 |

Teaching (SQ015) |

18 |

Arts creativity (SQ022) |

13 |

Arts creativity (SQ022) |

20 |

|

Informal play (SQ008) |

15 |

Conservation tasks (SQ020) |

18 |

Organised fitness (SQ011) |

16 |

Meetings (SQ019) |

10 |

Other nature study (SQ025) |

20 |

|

Running (SQ004) |

13 |

Birdwatching (SQ024) |

17 |

Birdwatching (SQ024) |

16 |

Foraging (SQ021) |

9 |

Growing food (SQ013) |

18 |

|

Meetings (SQ019) |

13 |

Teaching (SQ015) |

12 |

Formal social (SQ028) |

15 |

Formal social (SQ028) |

8 |

Organised fitness (SQ011) |

16 |

|

Formal social (SQ028) |

13 |

Medical uses (SQ018) |

11 |

Wheeling (SQ003) |

14 |

Other (SQ029) |

8 |

Meetings (SQ019) |

16 |

|

Medical uses (SQ018) |

10 |

Arts creativity (SQ022) |

11 |

Outdoor cookery (SQ023) |

12 |

Organised fitness (SQ011) |

7 |

Foraging (SQ021) |

12 |

|

Outdoor cookery (SQ023) |

10 |

Other nature study (SQ025) |

11 |

Animal care (SQ014) |

11 |

Growing food (SQ013) |

7 |

Animal care (SQ014) |

11 |

|

Teaching (SQ015) |

8 |

Foraging (SQ021) |

6 |

Foraging (SQ021) |

11 |

Conservation tasks (SQ020) |

7 |

Other (SQ029) |

10 |

|

Foraging (SQ021) |

8 |

Outdoor cookery (SQ023) |

6 |

Informal play (SQ008) |

9 |

Animal care (SQ014) |

6 |

Competitive sport (SQ006) |

9 |

|

Other (SQ029) |

8 |

Competitive sport (SQ006) |

5 |

Changing facility (SQ010) |

9 |

Teaching (SQ015) |

5 |

Teaching (SQ015) |

9 |

|

Playground (SQ007) |

7 |

Playground (SQ007) |

5 |

Playground (SQ007) |

5 |

Medical uses (SQ018) |

5 |

Outdoor cookery (SQ023) |

9 |

|

Animal care (SQ014) |

7 |

Animal care (SQ014) |

5 |

Medical uses (SQ018) |

3 |

Outdoor cookery (SQ023) |

5 |

Formal social (SQ028) |

9 |

|

Changing facility (SQ010) |

5 |

Informal play (SQ008) |

4 |

Competitive sport (SQ006) |

1 |

Changing facility (SQ010) |

4 |

Changing facility (SQ010) |

4 |

|

Competitive sport (SQ006) |

3 |

Other (SQ029) |

2 |

Other (SQ029) |

1 |

Competitive sport (SQ006) |

3 |

Medical uses (SQ018) |

3 |

Table 3. Intensity of use by NHS Functional Area. Number of respondents in each category.

|

Answer |

Medicine |

Pathology |

Clinical Oncology |

Other cancer care |

Imaging |

Dental/Oral |

Surgery eg orthopaedics |

Obstetrics and gynaecology |

Psychiatry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I do not know |

119 |

132 |

129 |

118 |

135 |

136 |

129 |

136 |

91 |

|

No active use of the outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge |

14 |

22 |

12 |

12 |

19 |

18 |

13 |

14 |

11 |

|

Very limited active use of outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge |

5 |

0 |

11 |

14 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

3 |

18 |

|

Some active use of outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge, including some use in treatment pathway plans and monitoring outcomes |

15 |

2 |

5 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

1 |

25 |

|

Extensive active use of outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge including active use or promotion in treatment pathway plans and active monitoring outcomes |

4 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

15 |

|

Total number of answers |

157 |

158 |

158 |

157 |

156 |

155 |

157 |

155 |

160 |

|

No answer |

43 |

42 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

43 |

45 |

40 |

|

Answer |

Occupational Health |

Primary Care |

Health Promotion |

Clinical Support |

General Acute, A&E |

Estates |

Facilities |

Corporate |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I do not know |

107 |

104 |

82 |

131 |

133 |

116 |

119 |

114 |

73 |

|

No active use of the outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge |

12 |

14 |

11 |

11 |

17 |

9 |

12 |

16 |

3 |

|

Very limited active use of outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge |

9 |

17 |

17 |

3 |

1 |

9 |

8 |

10 |

1 |

|

Some active use of outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge, including some use in treatment pathway plans and monitoring outcomes |

22 |

15 |

30 |

6 |

1 |

12 |

8 |

8 |

2 |

|

Extensive active use of outdoor estate for therapeutic, medical or other service purposes to the best of my knowledge including active use or promotion in treatment pathway plans and active monitoring outcomes |

6 |

7 |

17 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

Total number of answers |

156 |

157 |

157 |

153 |

153 |

152 |

151 |

151 |

80 |

|

No answer |

44 |

43 |

43 |

47 |

47 |

48 |

49 |

49 |

120 |

Table 4. Other organisations and their involvement in health and well-being activity on the NHS outdoor estate in Scotland. Numbers responding for each category. The key to the table codes are in a separate table below.

|

Answer |

LA |

CHW |

NA |

CARTS |

LG:HF |

LG:SI |

LG: CY |

LG: EY |

LG: CF |

LG: O |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No knowledge (AO01) |

107 |

93 |

121 |

118 |

103 |

133 |

123 |

120 |

113 |

114 |

82 |

|

Very limited involvement (AO02) |

22 |

18 |

6 |

11 |

15 |

10 |

13 |

17 |

11 |

17 |

2 |

|

Some involvement (AO03) |

21 |

27 |

12 |

11 |

21 |

6 |

14 |

13 |

13 |

13 |

1 |

|

Active involvement (AO04) |

5 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

13 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

8 |

7 |

3 |

|

Active driver of activity (AO05) |

4 |

11 |

10 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

3 |

4 |

|

No answer |

41 |

41 |

45 |

45 |

42 |

47 |

47 |

46 |

46 |

46 |

108 |

|

Local Authority |

LA |

|

Charity: Health and Welfare Focus |

CHW |

|

National Agency eg Forestry Commission |

NA |

|

Conservation, Amenity or Recreation Charity or Trust |

CARTS |

|

Local Group: Health Focus |

LG:HF |

|

Local Group: Special Interest Focus (eg model engineering society) |

LG:SI |

|

Local Group: Children and Youth Groups |

LG:CY |

|

Local Group: Early Years |

LG:EY |

|

Local Group: Conservation focus |

LG:CF |

|

Local Group: other |

LG:O |

The top involved organisations identified as being either actively involved or an active driver of activity were:

- Charities with a health and welfare focus (21/200 respondents).

- Local groups with a health focus (19/200 respondents).

- Local groups with a conservation focus (17/200 respondents).

- National agencies like Forestry Scotland (16/200 respondents).

- Conservation, Amenity and Recreation Trusts or Charities (15/200 respondents).

A surprising omission from this list, in view of some of the information from the earlier semi-structured interviews, are Local Authorities. However, if the response for ‘some involvement’ is included Local Authorities would occupy third equal position on the list with Local Groups with a Conservation Focus at 30/200 respondents each. On this basis the first two positions would still be occupied by Charities with a health and welfare focus, and local groups with a health focus respectively.

Property and Asset Management Strategies (PAMS) are the principal instrument by which the NHS estate is managed. Most respondents (66%) had not heard of PAMS, and another 19% had heard of them but had no idea of the extent to which they reflect health and well-being benefits (Table 5).

Table 5. Extent of recognition of health and well-being benefits of the outdoor estate within NHS Scotland PAMS.

|

Answer |

Count |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

I have never heard of PAMS (AO01) |

132 |

66% |

|

Heard of PAMS but no idea of the extent to which they reflect health and well-being benefits (AO02) |

37 |

19% |

|

Current PAMS do not reflect health and well-being benefits of the outdoor estate, potential or actual (AO03) |

3 |

2% |

|

Current PAMS do not reflect health and well-being benefits of the outdoor estate but there are signs that future revisions will reflect these (AO04) |

8 |

4% |

|

Current PAMS reflect the role or potential role of the outdoor estate but are vague or non-committal with regard to development and performance measurement (AO05) |

8 |

4% |

|

Current PAMS have embraced the role of potential role of the outdoor estate, with analysis of existing contribution, clear objectives for future development or deployment and the adoption of performance measures which are regularly reviewed (AO06) |

4 |

2% |

|

No answer |

8 |

4% |

|

Totals |

200 |

100% |

The few remaining respondents divided almost equally around the division between the top and bottom two categories in the Likert scale we developed for this question.

Several of the survey questions invited additional comments and the survey attracted 204 additional comments in total. We have not conducted a formal thematic analysis of these comments, some of which were extensive, but the following themes easily emerge from them:

- Dog walking as a use was mentioned in response to several questions, with at least six references to this activity.

- Outdoor smoking was also mentioned, with three mentions of this activity one acknowledging its illicit nature in hospital grounds.

- Awareness of the potential benefits was clearly a broad theme for many respondents, while there were a smaller number of others who had never really considered that the NHS outdoor estate might be a therapeutic resource, captured neatly by one respondent who said, “Completing this survey has opened my eyes to the possibilities that the NHS outdoor space CAN be used for. It is something I had never thought about. I've always enjoyed walking around the grounds during my break and lunchtimes but never considered any other uses by other departments. I genuinely hope that the departments and/or wider agencies are encouraged to use the outdoor spaces in a more fruitful way”.

- Equally common was the recognition amongst respondents that much more could be done with the NHS outdoor estate through the implementation of practical adoption measures. This was coupled with a strong enthusiasm among respondents for more to be done.

- Pragmatically respondents also recognised difficulties in implementing good ideas for the greenspace, coupled with a sense of frustration at the demands on existing NHS resources. This frustration extended to the grounds management at some hospital sites, where it was recognised that management of greenspace could be more ambitious and imaginative in its engagement with the local environment and the needs of users.

- There was also an underlying sense of isolation amongst respondents, in that so many had so little idea of what was happening or could happen in areas of the NHS outside their own immediate experience and role.

Taken as a whole the survey shows:

- There is an extensive set of uses of the NHS Scotland estate – wider than is currently recognised in published sources.

- Walking is the dominant activity across all users. Future work could seek to distinguish different types and purposes of walking, distinguishing, for example, necessary travel to and from work; movement within the working day; and walking for other purposes including its own therapeutic or well-being impact.

- The top 10 uses identified by respondents to the survey were, in addition to walking: secure bicycle storage, active travel to and from work, picnic areas, informal recreational gardening, cycling, running, informal social gatherings, outdoor therapeutic interventions or rehabilitation and organised fitness sessions.

- Most respondents work in the NHS. There is scope to increase the external perspective on the use of the outdoor estate. More than three-quarters of the responses related to the following NHS Boards: Ayrshire and Arran, Tayside, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Borders.

- In theory there is considerable scope to do a great deal more for therapeutic and well-being purposes with the NHS estate, and these benefits could be as strong for staff, visitors, volunteers, local communities as for patients. The results may even suggest that the benefits to the former groups could be at least as great or greater than for patients.

- There is a great enthusiasm for more extensive and better uses of the NHS Outdoor estate, but one obstacle to building on this asset will be the time and other resources required to do so.

- More formal promotion of the role of Property and Asset Management Strategies in the promotion of health and well-being uses of the outdoor estate could help to secure focus.

- Greater work to explore the inclusion of greenspace within formal health and treatment pathway protocols may also help to secure focus and commitment.

- The discussions beforehand, and to a lesser extent the survey, suggest that more could be achieved by working closely with non-NHS organisations in the development of new solutions on the NHS outdoor estate.

3. Assessing health and well-being benefits of the NHS outdoor estate – a conceptual model

This project has taken an integrated approach to the valuation of health and well-being benefits, a natural capital approach and a health economics perspective. Here, we use a natural capital approach to create a logic chain for the relationships between the natural capital assets of the NHS outdoor estate, the ecosystem services and benefits.

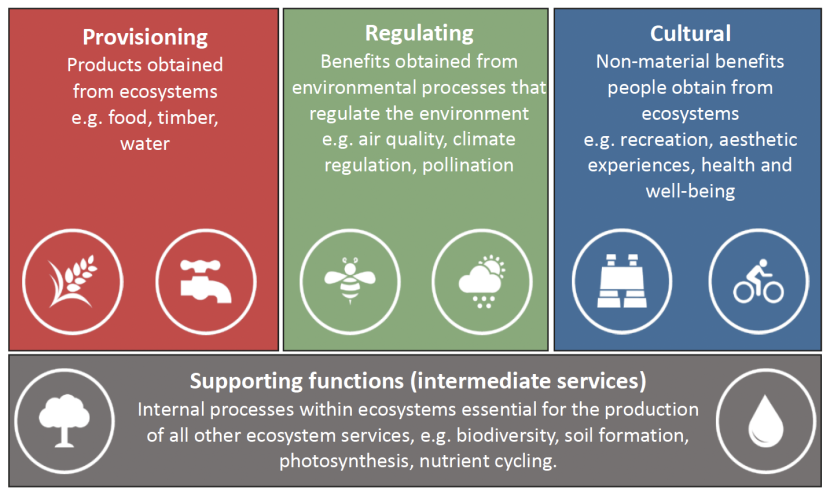

Natural Capital is defined as “..elements of nature that directly or indirectly produce value or benefits to people, including ecosystems, species, freshwater, land, minerals, the air and oceans, as well as natural processes and functions” (Natural Capital Committee, 2014). It is the stock of natural assets (e.g. soils, water, biodiversity) and supporting functions (soil formation, nutrient cycling) that produces a wide range of ecosystem services that benefit people. These include food production, regulation of flooding and climate, pollination of crops, and cultural benefits such as aesthetic value and recreational opportunities (Figure 2).

They are the underpinning structures and processes that give rise to ecosystem services. Figure 2 is a diagram setting out the four key types of ecosystem services, namely provisioning services, regulating services, cultural services and supporting services. Provisioning services are products obtained from ecosystems such as food and timber. Regulating services are the benefits obtained from environmental processes that regulate the environment such as climate regulation. Cultural services are the non-material benefits people obtain from ecosystems such as health and well-being and supporting services are internal processes within ecosystems essential for the production of all other ecosystem services such as soil formation and photosynthesis.

As valuation is being considered in this project it is important to break down this concept further to ensure the environmental functions that lead to (physical) flows of goods and services (or benefits), and the economic production functions that lead to (monetary) flows of goods and services (or benefits) are considered separately. This splits the products of the natural system from the those of the social system and makes it clear which outputs require biophysical measurements and which outputs can be valued∗. As an example of this distinction, green health activities and water quality regulation are, respectively, final cultural and regulating ecosystem services, and stress reduction and clean drinking water are the health and well-being benefits that flow from these that can be quantified and valued.

3.1. Natural capital logic chain

One of the principal tasks of this project was to develop a conceptual model of the relationships between the natural capital assets of the NHS outdoor estate, and the health and well-being benefits that flow from them. A logic chain has been created (Figure 3) that describes the pathway that leads to a monetary value of those benefits. In addition, it includes the main factors that influence the delivery of health and well-being benefits from the NHS Scotland outdoor estate, as well as the beneficiary groups. Each stage needs to be measured to quantify the value.

The natural capital assets are the different habitats that may occur on NHS Scotland’s outdoor estates, e.g. woodland, gardens, allotments and grassland (Figure 3). These assets may alone give rise to final cultural ecosystem services such as recreation or restorative green health activities (e.g. walking, running, birdwatching), and certainly give rise to regulating services (e.g. air quality, noise and climate regulation). However, for many of the cultural services and the provisioning service of food production, further physical and social infrastructure will be required before the final ecosystem services and benefits can be realised. This might be the creation of cycle paths or footpaths and allotments, or organised activities such as exercise programmes (green gyms), conservation groups or therapeutic programmes. These all require labour and capital inputs. Whether or not the benefits are provided, or the extent to which the benefits can be provided, also depends on the accessibility of the greenspace provision (e.g. whether the natural capital asset is directly outside where a user is a patient or where they work, or is more than a few minutes away on foot or by bike, see Section 6 for discussion), how much greenspace there is available and the quality of the greenspace (whether it is well maintained or biodiverse).

The flow of health and well-being benefits are wide ranging (Figure 3), from stress reduction, increased mental health and happiness and sleep improvements, through lowering risk of chronic, metabolic and clinical diseases, to reducing pollution, noise, heat and flood hazards. This level of the flow of benefits is mediated by the exposure of beneficiaries to these greenspaces, whether any one visit is short or long, or whether these visits are daily, weekly or monthly. The benefits may increase if social interaction is also occurring during the visit/activity.

The logic chain (Figure 3) also outlines the beneficiaries of these benefits. In the NHS context these range from inpatients, outpatients, staff, and visitors and local communities, including individuals, families, school and nursery children. In relation to the cultural benefits these will flow directly to the users of the greenspaces. The regulating benefits will benefit those on site and those in surrounding communities. These benefits have value. Value can be captured in many ways, and we suggest an approach to evaluating and valuing these benefits in Section 5.

Any tool that is eventually developed for valuing the benefits that flow from the uses of the outdoor estate will also need to quantify the physical flows of these services. For provisioning and regulating services it is usual that the area and type of habitat is one of the determining factors that delivers a physical flow value (e.g. the area of woodland and species of tree will determine the amount of a pollutant adsorbed). It is more complicated for cultural services. The type, spatial location, accessibility, quality and quantity of greenspace will need to be measured as they certainly influence the type and frequency of activity that takes place, and hence the value. Ultimately the existence of greenspace determines whether there is a potential flow of these benefits or not. However, it is also necessary to quantify the number of people and their mental or physical response to being in the greenspaces, to complete the valuation. The Social Return On Investment framework proposed for use in the evaluation and valuation of health and well-being benefits (see Section 5 and 6) will pick up the full range of factors (environmental, social and economic) determining the value of the benefits whether or not they can be quantified. The importance of the natural capital assets will, therefore, be included. The type, location, accessibility, quantity and quality of the natural capital assets are even more important in a strategic context for the NHS Health Boards, as they determine how demand for these services can be met and where. Certainly, for organised activities like practical conservation and therapeutic gardening there needs to be the right amount of greenspace of the right type for the activity to go ahead. There can only be as many programmes as the space allows.

The above diagram shows the relationships between the natural capital assets (different greenspace types e.g. garden or woodland); the cultural ecosystem services such as recreation or restorative green health activities (e.g. walking, running, birdwatching), and provisioning and regulating services (e.g. air quality, noise and climate regulation) that give rise to health and well-being benefits (increased mental health and happiness, lowering risk of chronic diseases, including health benefits from reducing pollution, noise, heat and flood hazards). It also outlines the beneficiary groups (patients, visitors, staff and local community users) and emphasises that the health and well-being benefits and the regulating service benefits to these groups will vary depending on the type, spatial location, accessibility, quality and quantity of greenspace, the infrastructure that is provided (e.g. cycle paths, footpaths) and organised activities available (e.g. green gyms or practical conservation). All these elements need to be measured to enable a valuation of the natural capital benefits, i.e., the greenspace characteristics as well as the human use and benefits.

4. Valuing the health and well-being benefits of the NHS outdoor estate – rapid review and expert panel meeting

The aim of the rapid review was to identify scientific research papers and grey literature that contained metrics and toolkits for quantifying the health and well-being benefits (flowing from both regulating and cultural services) derived from activities in greenspaces related to the NHS outdoor estate. The focus was placed largely on the cultural services in the review, because there are fewer metrics available at present and it is a fast growing area of research. Regulating services that give rise to health and other benefits are better studied and there are already good metrics available.

Rapid evidence reviews are used in health sciences by Defra and in reviews commissioned by the Scottish Government. We drew on good practice from the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). The following questions guided the review:

- What are the health and well-being benefits from exposure to greenspaces of the type found on NHS estates? (Benefits delivered via provisioning, regulating services and cultural services.)

- What are the health and well-being benefits from specific health interventions (activities) employed by the NHS estates? (Benefits delivered via provisioning, regulating services and cultural services.)

- How are physical flow of benefits quantified? (Toolkits used or individual metrics.)

- How are the monetary values of these benefits quantified? (Toolkits used or individual metrics.)

The rapid review was focused specifically on papers and grey literature that quantify the relationships between the greenspace type (e.g. park / allotment / woodland) or intervention (e.g. green gym, therapeutic gardening) and the health and well-being response to exposure or participation (e.g. decrease in stress, increased quality of life, reduced mortality or morbidity). Web of Science and Google Scholar were searched to ensure that studies were captured from the scientific literature and the grey literature. The specific search terms used are outlined in Table 6 below. The search terms from the first two columns were combined with Boolean operators (e.g. “greenspace” AND “reduced morbidity”). Then a third search term from the third column was added (e.g. “greenspace” AND “reduced morbidity” AND “QALY”). Searches were also conducted using “green space” as well as “greenspace” to ensure all relevant studies were picked up. The searches were limited to research and grey literature published in the English language between 2000-2022. The scope outlined for this search was to keep the review concise and deliverable within the timeframe expected for a rapid review.

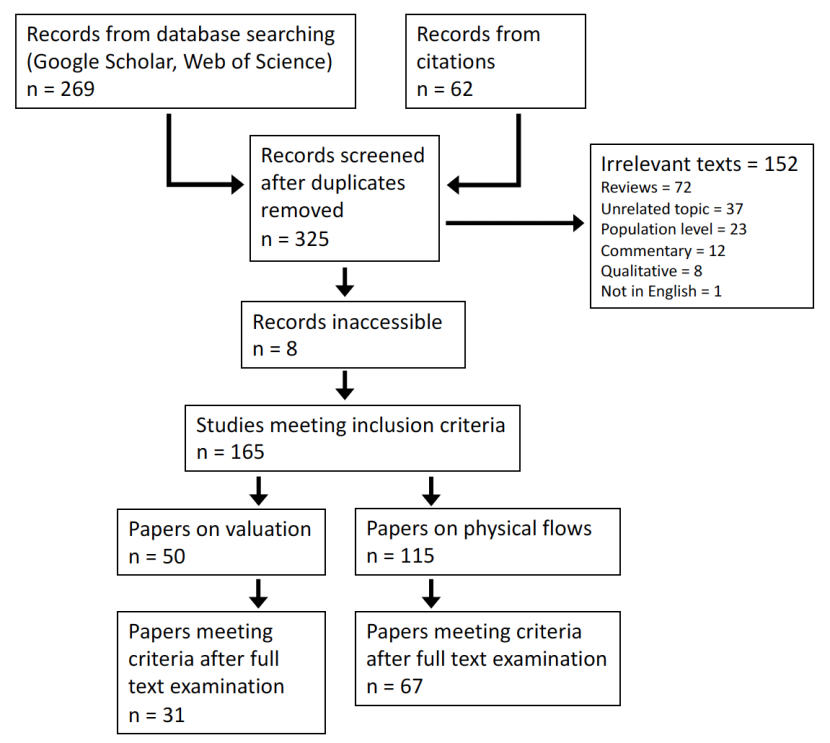

Relevant studies were first assessed by title and were taken from NatureScot and NHS Scotland reports supplied by the client. Key review studies that had been identified in the NHS Lothian natural capital assessment report were also included (62 studies, Figure 4). Two hundred and sixty-nine papers were accepted in this first stage of the review from the Web of Science and Google Scholar searches (Figure 4). Once these were screened for duplicates, irrelevant texts filtered out by reading the abstract, and excluding studies that were not accessible online, 165 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 4). A significant proportion (70%) of these papers were focused on quantifying the physical flows of the cultural and regulating services that deliver health and well-being benefits (e.g. measuring physical activity in greenspaces, morbidity or changes in physiological responses), and 30% were focused on valuing the health and well-being benefits.

Table 6. Search terms used in the literature review.

|

Greenspace type or activity |

Response |

Study type |

|---|---|---|

|

Natural capital |

Higher rates of physical activity |

QALY |

|

Greenspace |

Recreational benefits |

Cost benefit |

|

Bluespace |

Connection with nature |

Cost-effectiveness |

|

Natural environment |

Social contact and cohesion |

Case study |

|

Urban green infrastructure |

Mitigation of heat island effects Reduction of noise pollution |

- |

|

Parks |

Reduction of air pollution |

- |

|

Gardens |

Reduction of flooding |

- |

|

Allotments |

Improved nutrition |

- |

|

Woodlands |

Reduced mortality |

- |

|

Street trees |

Reduced morbidity |

- |

|

Biodiversity |

Better mental health |

- |

|

Green prescriptions |

Better quality of life |

- |

|

Therapeutic gardening |

Reduced health inequalities |

- |

|

Green gyms |