NatureScot Research Report 1335 - NatureScot Opinion Survey 2022

Year of publication: 2023

Authors: Stewart, D. and Eccleston, J.

Cite as: Stewart, D. and Eccleston, J. 2023. NatureScot Opinion Survey 2022. NatureScot Research Report 1335.

Keywords

environmental attitudes; biodiversity loss; climate change; corporate identity; public awareness; National Nature Reserves; Countryside Rangers

Background and approach

This report presents the findings from a nationally representative online survey of the Scottish adult population in November 2022. This survey covered a range of topics relating to NatureScot’s corporate identity, public awareness and understanding of the organisation’s work, and attitudes to environmental issues, including some topics previously included in the Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey which was last undertaken in 2019.

Main findings

NatureScot brand awareness

- Just under half the population had heard of NatureScot (47%), lower than for SNH in 2019 (78%). 12% were aware of what the organisation does. A larger proportion (35%) had heard of the organisation but were not sure of what it does.

- Overall, 20% of people recognised one or both of the NatureScot logos shown in the survey. By comparison when a similar question was asked in 2019, 37% recognised the SNH logo.

- The majority of respondents had a fairly accurate idea of NatureScot’s role, with most people indicating they believed the organisation’s role to involve looking after Scotland’s nature, protecting wildlife and preserving the environment. This was a much higher rate of correct responses than were provided about SNH’s role in 2019.

- The most important activities undertaken by NatureScot, according to participants, were ‘protecting native plants and animals’ (52%), ‘protecting Scotland’s finest landscapes’ (48%) and ‘helping people enjoy and benefit from nature’ (37%).

National Nature Reserves (NNRs)

- Just over two in five (43%) respondents had heard of National Nature Reserves. Similar proportions were aware of NNRs when this question was included in the 2017 (42%) and 2019 (41%) Scottish Nature Omnibus surveys.

- 61% of people stated that they had visited any NNRs during the last 12 months, a higher percentage than when the same question was asked in 2017 and 2019 surveys (40% in 2017, 54% in 2019).

- In terms of the specific NNRs visited in 2022, four reserves were selected by more than a tenth of respondents – Loch Lomond (37%), Glencoe (21%), Loch Leven (17%) and The Great Trossachs Forest (11%).

Countryside Rangers

- Around 3 in 5 respondents were aware that Scotland has Countryside Rangers (61%), a much higher percentage than when this question was last asked in 2019 (38%).

- A quarter of respondents (26%) recognised the Countryside Ranger logo, also a higher percentage than recorded in 2019 (19%).

Creation of new National Parks

- The vast majority of respondents supported the creation of one or more new National Parks in Scotland with 44% strongly supporting and 45% tending to support.

- Respondents were shown a list of potential reasons for establishing new National Parks and ask to select those which they felt were most important. The most frequently provided reasons were to protect Scotland’s best wildlife and landscapes (71%) and to deliver more on the opportunities to restore nature as well as protecting what exists already (52%).

Attitudes to biodiversity loss and climate change

- The majority of people agree that biodiversity loss is an immediate urgent problem (76%) and that taking action on biodiversity loss will help us to tackle climate change (70%). However, fewer than half of respondents indicated that they worried about loss of diversity in everyday life, that they felt optimistic about our collective ability to stop biodiversity loss, or that they knew what actions their household could take to stop biodiversity loss.

- A larger majority of people (83%) also agreed that climate change is an immediate and urgent problem, and that climate change and biodiversity loss are linked (74%) and can be tackled together. However, comparing responses to each of the crises it is clear that levels of concern and understanding of actions which can be taken are higher in relation to climate change than for biodiversity loss.

1. Background

1.1 Objective

This survey was commissioned by NatureScot to provide updated quantitative insights on a number of topics relating the natural environment as follows:

- Awareness and opinions of NatureScot

- Awareness of National Nature Reserves

- Visits to National Nature Reserves

- Awareness and understanding of the role of Countryside Rangers

- Opinions on the creation of new National Parks in Scotland

- View on Scottish landscapes

- Attitudes to biodiversity

- Attitudes to climate change

This report summarises the findings relating to the topics listed above, including comparisons with results from previous comparable findings from the Scottish Nature Omnibus where available.

Table 1. Unweighted and weighted sample profile by key demographics

|

- |

Unweighted sample |

Weighted sample profile |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

- |

- |

|

Male |

421 (42%) |

48% |

|

Female |

585 (58%) |

52% |

|

Age band |

- |

- |

|

16-34 |

234 (23%) |

29% |

|

35-54 |

315 (31%) |

32% |

|

55+ |

461 (46%) |

39% |

|

Socio-economic group |

- |

- |

|

ABC1 |

604 (60%) |

52% |

|

C2DE |

406 (40%) |

48% |

|

Region |

- |

- |

|

West |

374 (37%) |

45% |

|

South |

59 (6%) |

5% |

|

East |

395 (39%) |

35% |

|

North |

182 (18%) |

15% |

|

Total sample |

1,010 (100%) |

- |

During data analysis respondent postcodes were matched with publicly available classifications. Specifically, respondents were classified as follows:

- Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) – respondents were grouped on the basis of residency in the 10% most deprived areas, the 10% least deprived areas and the middle 11% to 89% areas.

- Scottish Government urban/rural classification – respondents were classified using the six-fold classification ranging from large urban populations to remote rural populations.

A number of other demographic variables were recorded in the survey and also used in the analysis of results. The full questionnaire used is included in the Annex.

In several places throughout this report, reference is made to results from 2017 and 2019. These refer to waves of the Scottish Nature Omnibus, a survey conducted by SNH in which some of the questions included in NOS were previously asked.

2. NatureScot

2.1 Awareness of NatureScot

This survey was conducted two years after the adoption of the name NatureScot. Just under half of the population had heard of NatureScot, with 12% stating that they had heard of the organisation and knew what they do, while a further 35% had heard of the organisation but were not sure of what they do.

49% had never heard of NatureScot.

A similar question was asked in the 2019 Scottish Nature Omnibus in relation to awareness of SNH. Awareness levels of SNH were significantly higher with a total of 78% having heard of the organisation (29% knew what they did and 49% had heard of them but did not know what they did). At the time, 18% had not heard of SNH.

Comparing responses amongst different demographic groups, respondents most likely to state that they were aware of NatureScot and knew what the organisation does included those who work full time (16%) and people aged 18 to 34 (16%).

Conversely, people aged 55 or over, residents of the South of Scotland and retired people were more likely to state that they had never heard of NatureScot (58%, 56% and 57% respectively).

2.2 Logo recognition

Respondents were shown two NatureScot logos, illustrated below, and asked if they recognised either. Overall, 20% recognised either of these while 3% recognised both. 12% stated that they had seen the version with the writing before and 11% had previously seen the round green logo. However around two-thirds of the population (68%) had not seen either logo before and a further 12% did not know if they had seen either.

Bar chart of responses to the question of whether people recognised the NatureScot logo. The bars are oriented vertically, with the answer categories along the x axis and the percentage of participants who answered each category on the y axis. Two NatureScot logos are shown. One is a green circle with a leaf logo without accompanying text. The other is the traditional NatureScot logo showing the leaf with accompanying text in English and Gaelic. 20% of people indicated they recognised either logo. 3% recognised both. 11% recognised the logo without text. And 12% recognised the logo with text.

By comparison when a similar question was asked in 2019, 37% recognised the SNH logo.

Reflecting the results relating to awareness of NatureScot, recognition of the logos was higher amongst people aged 18-34 (31% recognised one or both) and people who work full time (26%). Recognition was also higher amongst people with children in their household (27%).

2.3 NatureScot’s role

Participants who indicated they had heard of NatureScot were given an open-ended question to type in what they thought the organisation does.

Responses were coded into the categories used in previous surveys regarding SNH’s role, allowing for a comparison of perceptions before and after the change of name.

Table 2. Unprompted knowledge of NatureScot and SNH’s activities

|

- |

NatureScot |

SNH |

|---|---|---|

|

Looks after Scotland’s nature and landscapes |

46% |

20% |

|

Looks after/ protects wildlife/ animal/ birds/ habitats |

21% |

8% |

|

Looks after/ preserves environment/ countryside |

14% |

8% |

|

Looks after forests/ woodland |

4% |

2% |

|

Promotes Scottish tourism/ recreation |

2% |

2% |

|

Educational role/ teaches about natural environment |

1% |

2% |

|

Other positive comments |

1% |

2% |

|

Protects/ looks after Scotland’s heritage, culture, history |

1% |

21% |

|

Looks after/ preserves historic buildings/ museums |

- |

14% |

The majority of respondents appeared to have a fairly accurate idea of NatureScot’s role, with most responses relating to looking after Scotland’s nature, protecting wildlife and preserving the environment.

In contrast when a similar question was asked in the 2019 Scottish Nature Omnibus about SNH’s role, a much larger percentage of respondents provided incorrect responses suggesting that SNH protects Scotland’s heritage, culture and history or looks after historic buildings or museums. These results suggest that the new name, NatureScot, gives a more accurate impression to the public of the organisation’s role than did the previous name.

A selection of the full responses provided in 2022 in relation to NatureScot’s role are provided below:

- “Tries to look after all things nature in Scotland.”

- “Promotes the natural heritage in Scotland.”

- “Promotes the health & diversity of Scotland’s rural & urban landscapes.”

- “Protect Scottish environment to benefit all types of nature”.

- “Helps keep Scotland’s countryside healthy along with all the wild animals/birds within.”

- “The government's arm of nature and the environment, taking forward issues related to them.”

- “Encourages and helps maintain and protect Scotland's natural environment. Helps enforce necessary legislation”.

- “I would expect them to play a role in maintaining Scotland's countryside, preserving ancient woodlands, encouraging farmers to act responsibly with regard to their management of their farms, encouraging the public to take better care of the environment for the benefit of all.”

Respondents aware of NatureScot were asked to consider a list of activities undertaken by NatureScot and to select those which they considered to be most important. A maximum of 5 options could be selected.

As shown below, the largest percentages selected ‘protecting native plants and animals’ (52%), ‘protecting Scotland’s finest landscapes’ (48%) and ‘helping people enjoy and benefit from nature’ (37%).

In contrast the least frequently selected activities were ‘advising on planning applications’ (10%), ‘helping to control deer numbers’ (8%) and ‘providing advice and funding to land managers’ (7%).

Bar chart ranking responses to the question asking participants to select what activities NatureScot should prioritise. Bars are oriented horizontally, with the percentage of people each answer along the x axis and the different activities NatureScot undertakes listed on the y axis. The activities are listed in descending order of the percentage of people selecting them as priorities. The leading three activities are protecting native plants and animals (52%), protecting Scotland’s finest landscapes (48%), and helping people enjoy and benefit from nature (31%).

Views on the priorities for NatureScot varied by age. The the youngest age group (18-34) were more likely to rate protecting native plants and animals (55%) and tackling the climate crisis (35%) as important while those aged 35-54 provided a higher rating for promoting Scotland’s Great Trails (21%) and promoting nature-based skills and jobs (20%) while the oldest age group (55+) were more likely to prioritise reintroducing native species (38%) and restoring peatland and other natural habitat (37%).

3. National Nature Reserves

3.1 Awareness of NNRs

Just over two in five respondents (43%) had heard of National Nature Reserves (NNRs) before while the same percentage had not heard of them (43%). The remaining 15% did not know if they had heard of them before.

As shown in Figure 4 below, similar percentages were aware of NNRs when this question was included in the 2017 and 2019 Scottish Nature Omnibus surveys.

Bar chart of awareness of NNRs, comparing data from November 2022, August 2019, and August 2017. The bars for the answer categories (Yes, No, and Don’t know) are oriented horizontally, with data from each of the three years shown in different shades of green. The results show that just as many people had heard of NNRs as had no (43% in both cases), with a further 15% indicating they did not know whether they had heard of NNRs. The data is relatively stable from year to year, ranging from 41% to 43% ‘Yes’ and 41% to 44% ‘No’.

Levels of awareness varied by demographics and place of residence with the highest levels among men (46% compared with 39% of women), residents of South of Scotland (56%) and residents of rural areas (53%).

3.2 Visits to NNRs

As shown in Figure 5, after being shown a map of Scotland’s NNRs, 61% stated that they had visited any NNRs during the last 12 months.

Overall, a greater number of people claimed to have visited NNRs compared with recent surveys. When the same question was asked in the 2017 and 2019 Scottish Nature Omnibus surveys, lower percentages claimed to have been to an NNR with visit levels increasing from 40% overall in 2017 to 54% in 2019 to the current level in 2022.

It is possible that that some of those answering this question may have mis-reported visits made to wider areas as a visit to an NNR, for example due to a lack of clarity over the extent of NNR boundaries, in particular in the Loch Lomond area. Nevertheless as this question was asked using a consistent survey approach in each year, the increased percentages of the population visiting NNRs is likely to reflect a real trend reflective of increasing levels of outdoor recreation within Scotland over this period.

During 2022, groups most likely to have visited an NNR included people aged 18-44 (70% visited any), members of the more affluent ABC1 socio-economic groups (65%), people who work full time (69%) and people with children in their household (69%).

However, groups less likely to have visited an NNR included those aged 65+ (50%), people who self-reported their health as fair or bad (57%) and residents of the 10% most deprived SIMD areas (54%).

In terms of the specific NNRs visited, as shown below four reserves were selected by more than a tenth of respondents – Loch Lomond (37%), Glencoe (21%), Loch Leven (17%) and The Great Trossachs Forest (11%).

Bar chart showing which NNRs were visited by those people who visited any NNRs in the last 12 months. All NNRs are listed on the y axis in descending order of percentage of people visiting, with percentage along the x axis. Bars are oriented horizontally. The results show that the overwhelming majority of NNRs were visited by no more than 5% of people who visited any NNRs, with the most common result being visits by 1% of people. Loch Lomond was by far the most visited, with 37% of NNR visitors having visited there in the last 12 months. The remaining NNRs visited by more than 5% of visitors were Glencoe (21%), Loch Leven (17%), The Great Trossachs Forest (11%), Clyde Valley Woodlands (9%), and Tentsmuir (9%).

While the relatively small sample sizes taking visits to individual locations should be taken into account in any analysis of individual site level data, it is useful to compare the percentages of respondents indicating they had visited NNRs during the last 12 months in 2022 compared with the levels recorded when the same question was asked in August 2019. The percentages claiming to have visited increased for all of the most visited locations shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Most visited NNRs – 2022 comparisons with 2019

|

- |

November 2022 |

August 2019 |

|---|---|---|

|

Loch Lomond |

37% |

21% |

|

Glencoe |

21% |

15% |

|

Loch Leven |

17% |

11% |

|

The Great Trossachs Forest |

11% |

6% |

|

Clyde Valley Woodlands |

9% |

7% |

|

Tentsmuir |

6% |

5% |

|

Glen Affric |

5% |

3% |

|

Glenmore |

5% |

4% |

|

St Cyrus |

5% |

3% |

|

Ben Lawers |

5% |

4% |

Respondents who had visited an NNR during the last 12 months were asked to what extent they agreed with a series of statements relating to their last visit, as shown in Figure 7.

The vast majority either agreed or agreed strongly that they enjoyed their visit to the reserve. Respondents more likely to agree strongly with this statement included women (50% compared with 43% of men) and people with ‘very good’ health (55%).

Most respondents also agreed they were interested in visiting other reserves as a result of their most recent NNR visit. While 34% of all respondents agree strongly with this statement, people aged 18-44 were significantly more likely to provide this response (44%). People in this younger age group were also more likely than older respondents to strongly agree that they learned more about nature on their visit (23%).

Just 10% agreed with the negative statement ‘the reserve was too busy for me to enjoy fully’. Men were more likely than women to agree with this statement (13% and 7% respectively).

4. Countryside Rangers

4.1 Awareness of Countryside Rangers

Around 3 in 5 respondents were aware that Scotland has Countryside Rangers, a much higher percentage than when this question was asked in the 2019 Scottish Nature Omnibus.

Bar chart of awareness of Countryside Rangers, comparing data from November 2022 and August 2019. The bars for the answer categories (Yes, No, and Don’t know) are oriented horizontally, with data from each of the three years shown in different shades of green. The results show that a greater proportion of people indicated they were aware of Countryside Rangers in 2022 (61%) than in 2019 (38%), with an inverted change noted in the percentage of people indicating they were not aware of Countryside Rangers.

4.2 Logo recognition

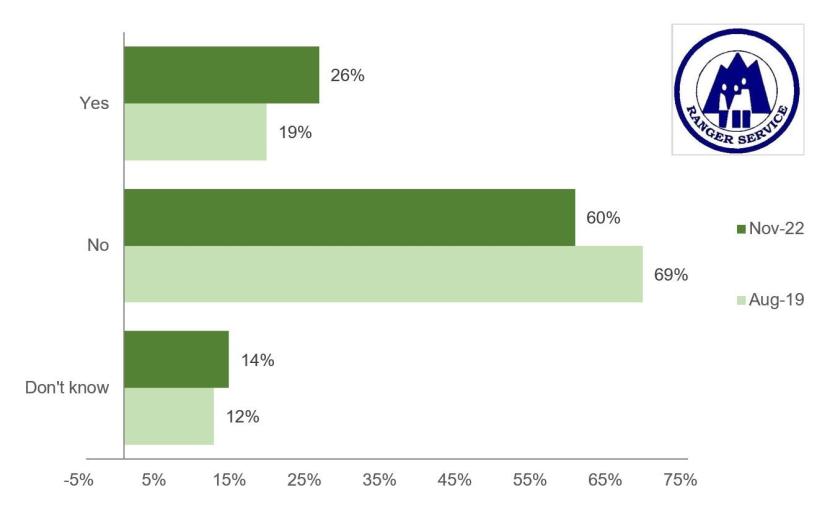

A quarter of respondents (26%) recognised the Countryside Ranger logo, a higher percentage than recorded in 2019 (19%).

Bar chart of recognition of the Countryside Rangers logo, comparing data from November 2022 and August 2019. The bars for the answer categories (Yes, No, and Don’t know) are oriented horizontally, with data from each of the three years shown in different shades of green. The results show that a slightly greater proportion of people indicated they did recognise the logo in 2022 (26%) than in 2019 (19%), with an inverted change noted in the percentage of people indicating they did not recognise the logo.

Recognition of the logo reflected general awareness of Countryside Rangers with higher levels recorded amongst men (30% compared with 23% of women) and people aged 55 or over (31%). Recognition levels were also higher amongst residents of rural areas (35% compared with 25% amongst urban residents).

4.3 Perceptions of Countryside Ranger role

Those who were aware of Countryside Rangers were asked an open-ended question about what they perceived their role to be.

While a range of responses was provided, the largest proportions suggested that Countryside Rangers were responsible for protecting nature/ wildlife or that their role was to ensure responsible behaviour amongst visitors to the countryside. A selection of the responses provided are shown below.

- “To police the countryside areas.”

- “Look after Scotland’s national parks Make sure that there is no destruction or vandalism.”

- “Protect the wildlife and habitat from incorrect use by the public.”

- “Protecting wildlife and keeping the parks safe for humans and animals.”

- “To help educate visitors and help protect nature. also teach children about different species.”

- “To provide information to the public visiting specific areas. Monitor wildlife. Ensure public are following countryside code.”

- “Keeping wildlife and the countryside safe.”

- “To ensure good management and control of our countryside and provide information.”

- “Protects wildlife and forests. They are involved in everything to do with the countryside, from hedgerows to wildlife.”

4.4 Attendance of Countryside Ranger activities or events

As shown in Figure 10, 15% claimed to have attended an event or activity attended by Countryside Rangers during the last 12 months, an increase from 8% in 2019.

Bar chart of whether people had attended events or activities where a Countryside Ranger was present, comparing data from November 2022 and August 2019. The bars for the answer categories (Yes, No, and Don’t know) are oriented horizontally, with data from each of the three years shown in different shades of green. The results show that in both years an overwhelming majority of people did not attend events where a Countryside Ranger was present (76% and 80% in 2022 and 2019 respectively.

Respondents most likely to have attended an event with Countryside Rangers present included those aged under 45 (21%), people who work full time (21%) and people with children in their household (28%).

5. Creation of new National Parks

5.1 General support for new National Parks

As shown in Figure 11, the vast majority of respondents supported the creation of one or more new National Parks in Scotland, with 44% strongly supporting and 45% tending to support.

Just 3% opposed the suggestion while 8% didn’t know.

Bar chart showing levels of agreement with the creation of one or more new National Parks in Scotland. Agreement statements are listed along the x axis: strongly support, tend to support, tend to oppose, strongly oppose, and don’t know. The percentage selecting each agreement statement is along the y axis. The results show that the overwhelming majority of people either strongly support (44%) or tend to support (45%) the creation of one or more new National Parks.

Groups most likely to strongly support the creation of new National Parks included residents of the South of Scotland (56%) and residents of rural areas (52%).

5.2 Reasons for establishing a new National Park

Respondents were shown a list of potential reasons for establishing new National Parks and ask to select those which they felt were most important. A maximum of three reasons could be selected.

As shown below, the most frequently provided reasons were to protect Scotland’s best wildlife and landscapes (71%) and to deliver more on the opportunities to restore nature as well as protecting what exists already (52%).

In contrast, much smaller percentages selected the options relating to rebalancing visitor pressure and increasing population growth in remote areas.

6. Scotland’s landscapes

6.1 General attitudes

Respondents were shown the following list of statements relating to Scotland’s landscape and asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with each.

While the vast majority agreed with the statement ‘Scotland’s areas of wildland should be protected’ (94% agreed or agreed strongly), responses to the other statements were more varied.

Responses to each of the statements differed somewhat by population groups including the following variations:

- Windfarms in Scotland are generally well located and designed – overall just over half agreed with this statement but agreement levels were higher amongst women (60% vs 51% of men), people aged 18-44 (67% vs 44% aged 55+) and residents of urban areas (61% vs 43% amongst rural residents).

- Most new development in the countryside is having a positive impact on Scotland’s landscapes – overall 36% agreed with this statement with higher levels of agreement amongst people aged 18-44 (44% vs 29% aged 55+), C2DEs (41% vs 31% of ABC1s) and residents of the 10% most deprived areas (58% vs 20% in 10% least deprived areas).

- The landscape in the places I like to visit in Scotland could accommodate more windfarms – while overall 40% agree with this statement, levels of agreement were higher amongst people aged 18-44 (52% vs 30% aged 55+).

- The landscape in places close to where I live could accommodate more windfarms – overall 45% agreed with this statement but those aged 18-44 and residents of urban areas were more likely to agree (54% and 48% respectively)

- Scotland’s landscapes are changing for the better – just under a third agreed with this statement overall but those aged 18-44 were more likely than older age groups to agree (37% vs 27%).

6.2 Rewilding

Respondents were asked to what extent they support or oppose rewilding in Scotland. As shown in Figure 14, the majority expressed support with 29% strongly supporting. Just 6% opposed rewilding in Scotland while 14% didn’t know.

9% of men opposed rewilding compared with 3% of women.

Bar chart showing levels of support for rewilding in Scotland. Support levels are listed along the x axis: strongly support, tend to support, tend to oppose, strongly oppose, and don’t know. The percentage selecting support level is along the y axis. The results show that the a majority of people either strongly support (29%) or tend to support (50%) the creation of one or more new National Parks. A significant number of people (14%) indicated that they didn’t know.

7. Attitudes to biodiversity loss and climate change

7.1 Biodiversity loss

Respondents were shown a series of statements relating to Biodiversity loss and asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with each.

As shown in Figure 15 below, the majority of respondents agreed to some extent that biodiversity loss is an immediate and urgent problem and that taking action on biodiversity loss will help us to tackle climate change.

However less than half of respondents agreed with the other statements relating to worrying about loss of diversity in everyday life, feeling optimistic about our collective ability to stop biodiversity loss and knowing what actions their household can take to stop biodiversity loss. Levels of agreement for all three of these statements was higher amongst those aged 18-44 than 45+.

7.2 Climate change

Respondents were shown a similar series of statements relating to climate change and asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with each.

As shown in Figure 16, the majority agreed that climate change is an immediate and urgent problem, that climate change and biodiversity loss are linked and can be tackled together and that they know the actions their household can take to tackle climate change.

However, responses were more varied in relation to the statements regarding level of everyday worry about climate change and optimism about our collective ability to tackle climate change. Women and younger age groups were more likely to agree with both of these statements.

Figure 17 compares levels of agreement with the three statements which were asked in relation to both biodiversity loss and climate change.

It is notable that levels of agreement were higher for all of the statements in relation to climate change. Most notably, respondents were around twice as likely to know what actions to take to tackle climate change.

Bar chart comparing agreement with similar questions relating to climate change and biodiversity loss. Bars are oriented vertically, with the percentage agreeing with each statement along the y axis. The following statements are arranged along the x axis: ‘an immediate and urgent problem’, ‘worry a lot in my everyday life’, ‘and know what actions I can take to tackle’. Bars showing the level of agreement are in two shades of green; dark green for biodiversity loss and light green for climate change. The results show that similar levels agree that climate change and biodiversity loss are immediate and urgent problems (84% and 76% respectively), and that they worry about these issues a lot in everyday life (53% and 42% respectively). However, a significantly higher (69%) proportion agreed that they knew what actions they could take for climate change than for biodiversity loss (34%).