NatureScot Research Report 1291 - Review of chough management between populations - a comparison of the biotic and abiotic factors influencing chough populations across the UK and Irish range

Year of publication: 2024

Authors: David Norfolk and Gavin Siriwardena (British Trust for Ornithology)

Cite as: Norfolk, D. and Siriwardena, G. 2024. Review of chough management between populations - a comparison of the biotic and abiotic factors influencing chough populations across the UK and Irish range. NatureScot Research Report 1291.

Keywords

red-billed chough; Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax; regional population trends; climate change; veterinary pharmaceuticals; habitat management; livestock grazing; food availability

Background

Chough in the British Isles are a species that feeds primarily in coastal, grazed grassland and that nest in holes in cliffs. Their nesting habit means that chough use nest boxes and quarries in some parts of their range, as well as natural sea cliffs. Other important foraging habitats, particularly at certain times of year and for specific populations, are sand dunes, mown silage fields, moorland, ploughed fields, stubbles and the tideline (Coombs, 1978). The diet consists almost entirely of invertebrates, access to which requires a short sward, although both probing in the soil (for earthworms, fly and moth larvae) and pecking on the surface (for ants, spiders and beetles) are used (Coombs, 1978). Chough largely feed in flocks during the non-breeding season and remain in (long-term bonded) pairs for breeding, but have a fluid social structure and are not strongly territorial, except close to the nest site (Coombs, 1978). Observational studies suggest that unpaired birds may help breeding pairs to raise chicks in some circumstances (Cowdy in Coombs, 1978), as is known for other corvid species (e.g., Richner, 1990). On Islay, where many birds are individually colour-ringed, several cases have been recorded of two siblings breeding with an unrelated partner in a trio (E. Bignal, pers. comm., 2023).

Scotland’s chough are at the northern-most edge of the species’ global geographical range. In Scotland, as elsewhere in Britain, chough have shown a protracted decline and range contraction over perhaps 200 years (Coombs, 1978). They are now restricted to the islands of Islay and Colonsay, but an increasing risk of regional extinction within the next 50 years has been identified due to the critically small population size (Trask et al., 2020; Stanbury et al., 2021). Since 2010, a programme of emergency supplementary feeding and parasite treatment, delivered by the Scottish Chough Study Group under contract to NatureScot, has stabilised the population, but further conservation action is needed to enhance their natural food supply and to address genetic threats, in order to develop a long-term solution.

The abundance and demography of chough on Islay have been monitored intensively since 1981, allowing rigorous population viability analyses to reveal that the mechanism for the recent population decline has been reduced first-year survival (from fledging to age one year, Reid et al., 2011). This has been attributed to reduced food sources in flock feeding sites (Reid et al., 2009), combined with high parasite burdens (Trask et al., 2020) and a genetically-driven recessive blindness condition that is expressed phenotypically due to the impoverished gene pool in the relict population (Trask et al., 2016). However, it remains possible that additional factors may also be involved, and the exact interactions between land management and food availability could be better understood. Nevertheless, the short-term (to date) success of supplementary feeding suggests that some food supply effect has been important.

Supplementary feeding has been conducted on Islay since 2010. Trask et al. (2020) report that c.82% of colour-ringed sub-adult and adult chough in the population that were known to be alive used the supplementary food between 2010 and 2018. The annual survival rates of all three age-classes (first-year, second-year and adult) were found to be positively associated with indices of use of supplementary food, while a greater proportion of breeding attempts were also successful in fed than in unfed areas. Research is continuing, but these results are strongly suggestive of acute food-limitation in the contemporary Islay population.

In addition, Trask et al. (2020) report that 58% of chough found dead on Islay that were examined from 2004-2018 (n = 14/24) had pathologically significant parasite burdens, potentially contributing to their mortality and low survival across the population. Parasites could operate as a proximate cause of death in birds that are weakened by lack of food or genetic deficiencies. Treatment of first-year chough showing symptoms of parasite infection with antihelminthic drugs increased their survival.

The results from population viability analyses by Trask et al. (2020) indicated that supplementary feeding (with associated parasite treatments) is now essential to maintain the population, but ultimately insufficient, as inbreeding will increase. Therefore, long-term conservation management in Scotland is likely to require a combination of management of food resources and genetic reinforcement, but continuing supplementary feeding and parasite treatment is critical in the short term.

The development of management approaches for chough on Islay, in particular, has been focused on the specific situation on the island due to conservation urgency and the possibility of high specificity given the policy focus on a small geographical area, leading to highly targeted potential solutions (e.g. Reid et al., 2009). This must be a positive, given that a comprehensive understanding of the ecology of the system underlies the focus, but it is also possible that ecological evidence relating to potential solutions from other parts of the chough’s range can also inform what conservation measures will be effective in Scotland. Therefore, it will be valuable to evaluate those that have been used for comparable populations elsewhere, with respect to the similarities and differences in drivers of change and ecological context. Specifically, direct supplementary feeding is not sustainable in the long-term and needs to be replaced with the provision of the equivalent ecological resources from habitat management and agricultural practices, together with effective enhancement of the gene pool. Both management and translocation measures from elsewhere may therefore provide valuable lessons for the Scottish situation, but the context of chronic, long-term decline and extreme range contraction must also be taken into account. In particular, the establishment of potential stepping stone populations between Islay and the nearest chough populations in Ireland and the Isle of Man needs to be considered to ensure long-term genetic viability within a larger metapopulation. This report aims to collate the evidence for the status, drivers of change and management effects concerning the Scottish and other relevant chough populations.

Main findings

- The Scottish chough population is of high conservation concern, despite ongoing interventions that allow it to persist. Without this active intervention it is very likely to go extinct, so maintenance of supplementary feeding and parasite treatments are critical in the short term. Long-term population sustainability will require sustainable habitat management and/or agricultural practices that provide sufficient food resources all year round, combined with genetic reinforcement of the population.

- Although there are indications that breeding success is somewhat higher in healthier populations, strong demographic comparisons between regions are not currently straightforward because results are not reported in a standard way. Formal inter-regional analyses would be valuable and could increase understanding of the drivers of population change significantly, but require novel integration of the data from diverse local groups.

- A wide range of biotic and abiotic factors could affect chough populations, and there are no obvious factors that are likely to be critical for the Scottish birds that have not been investigated. There are also no clear factors that affect the Scottish population uniquely, but comparatively healthy populations have not been studied in the same depth, which is a gap in our knowledge of the species.

- Conservation management measures applied for chough across the British Isles have many common factors and mostly involve the provision of foraging habitat, based on widely accepted key factors for foraging.

- There have been few strong evaluations of the effects of management interventions aimed at benefiting chough (as opposed to measuring environmental effects on their ecology). This means that there is no direct evidence for the efficacy of specific possible management approaches. Some novel intervention concepts have promise, but need to be trialled in respect of their effectiveness in practice.

- Based on the current understanding of chough habitat requirements, the available management approaches for grazing and livestock management practices should deliver suitable foraging habitat for chough. However, the details of the ecology supporting food resource availability and its relationships with management could be understood better, as where habitat may appear suitable, prey species may still be limited due to past or current land management. Inter-regional comparisons between the Scottish chough context and those of other populations would be valuable.

- Enhancing the genetic diversity of the Scottish population is essential for its survival, but will be challenging. There is no guarantee that captive bird releases will succeed in adding to the gene pool, for example released birds may not interbreed with the existing population (there is evidence that this was the case in Cornwall), and release protocols need to be developed in consultation with the other territories where releases have been successful and unsuccessful. Broader scale habitat management and possibly other release sites should also be considered to facilitate the operation of a metapopulation, in the form of a stepping-stone population along the west coast of the UK.

Acknowledgements

This review was funded by NatureScot. A number of individuals and organisations have provided crucial information for this document that would not be otherwise accessible via conventional literature searches. We would particularly like to thank the following for their communication and offers of help:

Ireland: Sinéad Cummins, National Parks and Wildlife Service

Scotland: David Jardine; Eric Bignal, Scottish Chough Forum; Ellen Bird, Morven Laurie, Dave Parish, NatureScot.

Isle of Man: Neil Morris, Manx Birdlife.

Northern Ireland: Adam McClure, BTO Regional Rep, Co. Antrim.

Wales: Julian Hughes, RSPB Cymru; Ian Johnstone, RSPB; Jane Hodges and Bob Haycock; Sarah Mellor, Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority; Tony Cross and Adrienne Stratford; Patrick Lindley.

England: Hilary Mitchell, Cornwall Bird Watching and Preservation Society; Ray Hales, Paradise Park Wildlife Sanctuary, Cornwall.

John Calladine, Ian Johnstone, Dave Parish, Morven Laurie, Sinéad Cummins, Ellen Bird and Jen Graham provided helpful comments to improve previous drafts of this report.

1. Introduction

The red-billed chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (hereafter chough) is a crow (Corvidae) species with a geographical range extending from the western coasts of Britain and Ireland, east through southern Europe, North Africa, Central and East Asia. It is a species of European Conservation Concern (Annex 1, EC Birds Directive). Chough in the UK and Ireland (and Brittany) are recognised as the distinct sub-species pyrrhocorax (Cramp et al., 1994) and are assigned Schedule 1 species status (Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981). This reflects ecological and biogeographical differences from the bulk of the range: birds in the British Isles and northwest France are on the edge of the range and live in coastal habitats, while the rest of the distribution is found in upland, inland regions. Population data are highly biased towards Europe, but Europe accounts for only c. 5% of the global population. Long-term records of decreases in European populations (Madge and Burn, 1993) lead to an estimation of the overall trend by the IUCN to be ‘declining’, but globally the species is also of ‘Least Concern’, reflecting the wide distribution of the majority of the population from Asia Minor to east Asia (BirdLife International, 2016). Given the geographical and ecological differences, it would seem unwise to reach conclusions about the chough status in the British Isles from evidence from the rest of the range. High conservation importance may not be justifiable in terms of the global population and current classification at the species level, but the pyrrhocorax sub-species is arguably sufficiently distinct, particularly in respect of the national and regional fauna, to support conservation priority. Chough may also be a figurehead species for the conservation of low-intensity agricultural ecosystems and the mosaic of habitats that such systems generally provide (Reid et al., 2009), although its potential to do this in practice in a UK context must be limited by its coastal-only distribution.

Chough were Amber-listed (UK) in 2009 (Eaton et al., 2009), due to being categorised as a Species of European Conservation Concern, but this criterion was removed in the 2015 UK assessment and the species remains on the Green List as of 2021, although the species is listed as Vulnerable in the IUCN2 UK assessment (Stanbury et al., 2021). ‘Green’ status reflects an overall lack of pronounced population change during recent decades and the period for which we have monitoring data, but declines are believed to have occurred over the preceding 150 years or so, leaving the extant, remnant populations in northwest Europe (Robinson, 2005). However, the overall current status masks risks of regional extinction of isolated populations within Britain and Ireland, in particular, and the species’ vulnerability is higher when these populations are considered individually. Regional differences in chough population trends are apparent: increases (or stability) in Cornwall and south Wales, but declines in Scotland and north and mid-Wales, as well as a local extinction in Northern Ireland. In Ireland, results from a chough census which took place in 2021 show localised declines in some regions, but stability overall (Colhourn et al., 2023), and, on the Isle of Man, recent anecdotal evidence suggests a perceived decline in a previously stable population, with Manx BirdLife planning an island-wide chough census in 2023 to investigate these observations (N. Morris pers. comm., 2022). Understanding the factors behind these differences in population trends and responses to previous and current management efforts should inform conservation actions in Scotland and elsewhere and facilitate informed policies and interventions.

1.1 Purpose of this review

The purpose of this review is to collate and synthesise all relevant literature and summary data on chough population dynamics, population threats and conservation management evidence that is currently available. By gathering information from key chough researchers and conservationists, we aimed to compile both published and unpublished literature on factors affecting chough populations from across the UK and Irish range. It is hoped the assimilation of this information will provide a greater understanding of factors influencing the chough populations across their respective regions, which will help to inform future conservation measures for Scottish birds and other populations within the wider British Isles, by identifying influences that both affect only individual regional populations and are common across multiple populations.

NatureScot, supported by the Scottish Chough Forum, are currently scoping a long-term programme of recovery for chough in Scotland. The results of this review are intended to collate the evidence for factors influencing chough populations across the British Isles, in order to inform conservation actions in Scotland and elsewhere, and to support the possible development of a wider recovery programme, including facilitating exchanges and linkages between otherwise isolated populations. There has been a recent reintroduction programme in Jersey, which is considered in the relevant section, but otherwise, the focus of the review is on birds in Britain and Ireland.

2. Methods

The review was divided into four sections, with rationales as described in sections 2.1-2.4. The specific methods applied for each review are then detailed in section 2.5.

2.1 Integrated review of chough population trends and dynamics

Differences in the temporal trends shown by populations in different regions, where they are subject to different environmental influences, can be informative about the factors to which a species is sensitive. Further, complementary information on population demography, i.e., dynamics, can indicate the life history stage where critical pressures have acted. This approach was central to the diagnosis of causes of decline among farmland birds in the UK (Siriwardena et al., 2000), for example. However, differences in population context and ecology between regions (such as the relative occurrence of immigration and the features of habitats that are available) could limit the extent to which comparisons are informative. For example, a larger, more connected population may be intrinsically more stable than more isolated populations. It is, therefore, important to consider population dynamics evidence with care.

Collating evidence about chough in Britain and Ireland is challenging, because of the species’ rarity and the fragmented nature of the wider population: reliable, standardised data are not collected by national monitoring schemes and small, regional populations tend to be difficult to study, in terms of generating sufficient sample sizes for robust analyses. Further, if regional populations differ ecologically, pooling data across different regions may be inappropriate. Hence, evidence is likely largely to be found in locally published sources for each region, having been collected using locally specific methods, and possibly may be difficult to access and to standardise.

2.2 Review of the evidence for the influences of biotic and abiotic factors (and interactions between them) on chough population dynamics

Species’ populations can be influenced by a wide range of environmental influences, both ecological (biotic) and related to the physical environment (abiotic). The key abiotic factors influencing chough could include climatic conditions, seasonal weather conditions, nest site availability (quarries, crevices in sea cliffs and out buildings), soil type and health (acidity, nitrogen and phosphorus levels), and underlying geology. Biotic factors could include sward structure and the effects of grazing of wild and domestic mammals (notably rabbits), avermectin or other veterinary pharmaceutical contaminants, soil biodiversity and abundance (i.e. food availability) and its drivers, and interactions with other wild species (including disease, competition and predation). Further, interactions between these factors may also be critical in terms of when and how they impact upon chough, because some influences may only be significant, for example, when conditions are harsh. It will also be important to consider the demographic mechanisms by which these influences may affect chough abundance, as this will affect how interventions might best be targeted. For example, winter habitat or weather conditions would be most likely to primarily affect overwinter survival, whereas nest site availability would affect breeding success.

2.3 Review of population establishment and conservation management measures

The status of British and Irish chough as vulnerable means that a range of management approaches have been taken to promote the species, but these vary with respect to the context of local populations and the threats that have been identified. A key contrast, or variation, may be that some local populations are remnants and/or declining, suggesting that aspects of the local environment have become unsuitable, while others are newly colonising or spreading, wherein management potentially involves enhancing nearby areas to allow further spread. In both cases, the approaches that have been successful in other locations may also be effective in Scotland, while unsuccessful approaches may provide important lessons, although population context must also be taken into account.

A similar approach to that used for population dynamics was undertaken to collate information regarding management approaches for chough, for the same reasons. The evidence found included that from local bird reports and atlases and that from consultation with local experts in each region, revealing the range of conservation management that has been applied to support existing populations and the establishment of new ones (via natural colonisation or reintroduction). Similarly, information on how and why some populations have been lost (e.g. from Northern Ireland in the 2010s, from southeast Scotland in the later 20th Century and from southwest England in the early 20th Century), or have seen only intermittent, short-term establishment (e.g. Mull, Galloway) was also sought. Relevant management measures in the last two decades were mostly implemented via agri-environment schemes (AESs), so scheme handbooks were consulted.

2.4 Review of evidence for the effects of management interventions on chough abundance and population dynamics

Clearly, evidence for the effectiveness of interventions should be an important factor in determining whether their wider use is to be recommended. Once again, the relevance of the evidence will depend on context, but could come from a range of sources. Interventions will notably include specific grazing and mowing measures that are designed to enhance habitat for chough (such as the Scottish Government’s Agri-Environment and Climate Scheme (AECS) ‘Chough Grazing Management’ option and ‘Chough Mown Grassland’ option). It will be important to consider both core intervention types, as might be tested in field trials or based on empirical evidence, and the AES options that codify them, because efficacy can be reduced following implementation in practice. Evidence could come from measured, hypothetical (i.e. based on logical deduction from ecological knowledge and principles) or modelled effects on chough numbers or demographic rates, notably breeding success and survival. Evidence quality could be revealed by factors including sample size, study duration, statistical significance, qualitative versus quantitative results, presence of confounding factors, and temporal and geographical relevance to the Scottish context. In addition, how well the sampling of chough parameters has been matched to the management activity could be critical; for example, the certainty with which habitat management can be associated with particular pairs whose breeding success is measured and the extent to which multiple interventions have been applied together, limiting the potential to assess their independent effects.

2.5 Literature review approach

For each individual review, we used a combination of systematic and traditional review protocols, focusing on the British Isles subspecies of chough in the UK and Ireland. Both peer reviewed and conservation/land management reports were searched to provide information. Utilising extensive access to online material via Google Scholar and Web of Science, academic search engines, and the resources of the Cambridge University Library, we accessed relevant resources that were available electronically, and carried out the searches using a comprehensive list of search terms based on key literature. Search results were refined by sifting manually to remove duplicate sources and by following promising references within the publications that were identified in the first instance. Harzing’s Publish or Perish© software was used to filter published literature that was less than 30 years old, where more up-to-date information was required for certain age-relevant topics (e.g. population assessments and the use of veterinary pharmaceuticals on livestock).

It was evident in the preliminary stages of the literature search that information pertaining to red-billed chough literature was limited, so search terms were generally restricted to using only two words (including ‘chough’).

Individual searches made in combination with ‘chough’ as the primary search term:

- AND agri-environment OR farmland OR management OR conservation OR population OR UK OR disease OR parasites OR measures OR prey OR livestock OR land-use OR predation OR climate OR distribution OR trend OR genetics OR foraging OR reproductive OR demographics OR nesting OR survival OR food OR ecology OR effects OR dung OR insects OR invertebrates OR avermectin OR drugs OR pharmaceuticals OR veterinary OR tourism OR disturbance OR grazing OR weather.

Additional searches were made that may not have been directly related to chough ecology, but could provide relevant information to support the evidence, or benefit discussion throughout this review:

- avermectin OR anti-parasitic AND birds OR livestock OR dung OR soil OR insects OR invertebrates.

- birds AND grazing AND sward OR livestock OR dung OR invertebrates.

In addition, since much relevant information was likely to be obscure and/or unpublished, we (a) used the BTO’s library (one of the two most comprehensive ornithological libraries in the UK) to search for relevant articles in local and regional bird reports and journals from across the UK and Ireland, and (b) utilised our network of contacts to approach the key chough researchers in Wales, Scotland, England, the Republic of Ireland and the Isle of Man, who supplied us with the most recent population and ecological results.

3. Population trends and breeding success

First, we summarise the current distribution and regional breeding population sizes of chough across the British Isles, then provide detail on the population trends and breeding success by region.

3.1 Populations of breeding chough in the UK and Ireland

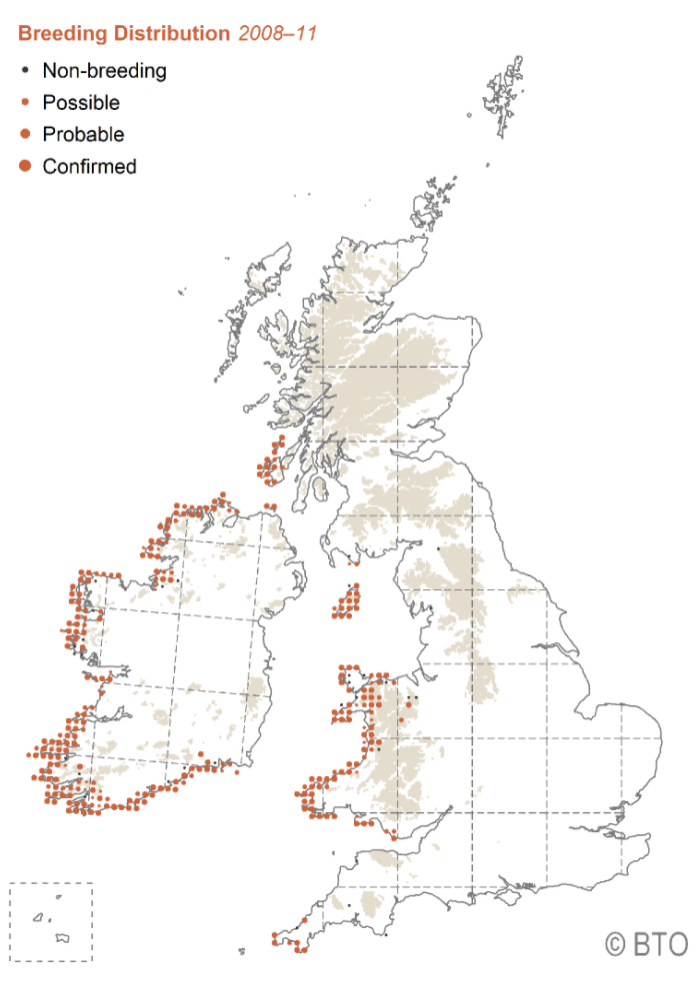

Map of the UK and Ireland showing the breeding distribution of chough during the period 2008 to 2011, from the BTO Breeding Bird Atlas. Orange dots show possible, probable and confirmed breeding locations via the increasing size of dots. All breeding chough are found on the western seaboards, with most birds in western Ireland, some in western Wales and the Isle of Man, and relatively few on Islay, Colonsay and Oronsay in Scotland.

Chough are predominantly distributed across the western coastlines of the UK and the Republic of Ireland (hereafter Ireland), in several well-defined but fragmented populations (Balmer et al., 2013). Ireland currently holds the largest population in the region and supports more than 70 % of the Northwest European population (Birdlife International/EBCC, 2000), with around 390 confirmed/probable breeding pairs (Colhoun et al., 2023). In 2014-15, Wales supported the largest percentage of UK birds (55%), with 236 breeding pairs, followed by the Isle of Man (31%) with 133 breeding pairs. Scotland’s population, at the time these figures were collated, comprised 11% of the total: a population of fewer than 60 pairs persisting on the islands of Islay and Colonsay, although with evidence of an ongoing decline. However, these results were obtained from 2014/15 data following the last UK and Isle of Man population assessment (Hayhow et al., 2018) and the detailed proportions are therefore expected to have changed by now. All populations are known to have seen both regional and local population changes since the 2014/15 population assessment. During the last national census, mainland England (Cornwall) supported only seven breeding pairs (2% of the UK population), which had tripled by 2021 (CBWPS, 2021). A smaller population has now been breeding in the wild on Jersey since 2015, following a captive breeding and reintroduction programme on the island. In 2021, the Jersey population was around 30 birds (Corry et al., 2021). Chough have not bred in Northern Ireland since the one remaining breeding pair disappeared from Rathlin Island in 2017 (Allen and Mellon, 2021).

Historical evidence suggests that chough were much more widespread than they are today (Yalden and Albarella, 2009), with declines being observed in the nineteenth Century in Wales, England and the Isle of Man, and a long-term range contraction in Scotland. However, there is evidence of recovery in some areas in the early part of the twentieth century (Owen, 1989). The declines have been attributed to a reduction of foraging habitat through changes in land-use and farming intensification (Bullock et al., 1983). From the 1960s onwards, there have been a number of censuses conducted on breeding chough in the UK and Ireland, which have provided more accurate population estimates. There have been four national censuses in the UK and Isle of Man: in 1982 (Bullock et al., 1983), in 1992 (Green and Williams, 1992), in 2002 (Johnstone et al., 2007) and in 2014 (Hayhow et al., 2018), and two surveys confined to Scotland, one in 1986 (Monaghan et al., 1989) and one in 1998 (Cook et al., 2001). There have been five censuses in Ireland (Cabot 1965; Bullock et al., 1983; Berrow et al., 1993; Gray et al., 2003; Colhoun et al., 2023). Section: 3.2 Regional population trends and breeding success below summarises the results of these censuses.

3.2 Regional population trends and breeding success

The available data on population size and change are summarised in Tables 1-3. Based on the available data, overall chough numbers appear to have remained relatively stable across the region in the last 30 years, apart from in Scotland, north and mid-Wales. In Northern Ireland, the very small population has undergone a gradual downward trend between survey periods, resulting in extirpation (Balmer et al., 2013). Available estimates of breeding success are summarised in Table 4; note that standard information is not available for all regions and the figures that have been quoted, or were available for collation here, are not necessarily equivalent. This is particularly true for the treatment of numbers of pairs or sites, in particular unsuccessful pairs or non-productive nest sites. An important parameter for demography is breeding success per pair, i.e., including zero values for pairs for whom nesting attempts failed or that did not breed. However, it was frequently unclear in the available sources whether all of these zero values were included in calculations, and they were clearly sometimes excluded. Hence, results are presented for the average numbers of fledglings per nest both including and excluding zeroes, where possible, or for the one of these that was available; the values including zeroes should be treated with particular caution as there could be hidden variations in the treatment of zeroes between data sources. Note also that differences in field methods could have a significant impact on the productivity estimates that are presented in Table 4: they depend on how occupied sites or pairs are defined (e.g. ‘possible’ and ‘probable’ breeding) and counting fledged (possibly hiding) chicks can be problematic, especially if families have left the immediate vicinity of the nest site. A formal comparison of regions really needs standardisation of all of these aspects of the methods (e.g. Hayhow et al., 2018); otherwise, it is likely that there will be significant biases.

Table 1. Summary of chough population estimates (breeding pairs) for UK, Isle of Man and Ireland from the past 30 years from national censuses.

‘NI’ denotes no information available.

|

Country/region |

1992 |

1998 |

2002/03 |

2014 |

2021 |

% change 1992 - 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

England* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

23 |

+2300 |

|

Isle of Man |

68 |

78 |

128 |

133 |

NI |

NI |

|

Scotland |

82 |

58 |

71 |

53 |

NI |

NI |

|

Wales |

151 |

173 |

228 |

236 |

NI |

NI |

|

Northern Ireland |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

-200 |

|

UK and Isle of Man |

303 |

310 |

429 |

433 |

NI |

NI |

|

Ireland |

428 |

NI |

445 |

NI |

386 |

-10 |

*Data derived from continuous annual monitoring

UK and Isle of Man estimates (Hayhow, 2018); Ireland estimates (Gray, 2003)

Table 2. Breakdown of population estimates of breeding pairs per county/region for Ireland. Pairs are confirmed and probable breeding pairs based on two standard visits.

|

Country |

County |

1992 survey |

2002/03 survey |

2021 survey |

% change 1992-2002/3 |

% change 2002/3-2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ireland |

Wexford |

8 |

0 |

4 |

-800 |

+400 |

|

- |

Waterford |

18 |

11 |

25 |

-38 |

+127 |

|

- |

Cork |

153 |

134 |

173 |

-9 |

+29 |

|

- |

Kerry |

112 |

141 |

68 |

-15 |

-52 |

|

- |

Clare |

19 |

11 |

31 |

-14 |

+182 |

|

- |

Galway |

26 |

16 |

14 |

-47 |

-13 |

|

- |

Mayo |

34 |

43 |

31 |

+23 |

-28 |

|

- |

Sligo |

10 |

7 |

3 |

-14 |

-57 |

|

- |

Leitrim |

1 |

4 |

1 |

+75 |

-75 |

|

- |

Donegal |

47 |

78 |

44 |

+28 |

-44 |

|

- |

Total |

428 |

445 |

394 |

-4 |

-11 |

(Adapted from Colhoun et al, 2023)

Table 3. Breakdown of population estimates of breeding pairs per county/region for UK and Isle of Man.

Pairs are confirmed and probable breeding pairs based on two visits (1992) and two visits plus all other information (2002, 2014, 2021). Results for England are derived from annual nest monitoring data of successful breeding pairs and not the standardised ‘two visit’ method as with all other regions. Percentage change of breeding pairs in UK and Isle of Man between surveys 1992, 2002, 2014, and in England and in 2021. ‘NI’ denotes no information available.

|

Country |

County |

1992 |

2002 |

2014 |

2021 |

% change 1992-2014 |

% change 2002-2014 |

% change 2014-2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scotland total |

- |

82 |

71 |

58 |

NI |

-29 |

-18 |

NI |

|

- |

Islay |

69 |

56 |

48 |

NI |

-30 |

-14 |

NI |

|

- |

Colonsay |

9 |

14 |

10 |

NI |

+11 |

-40 |

NI |

|

- |

Jura |

2 |

0 |

0 |

NI |

-100 |

0 |

NI |

|

- |

Dumfries and Galloway |

1 |

1 |

0 |

NI |

-100 |

-100 |

NI |

|

- |

Mull |

1 |

0 |

0 |

NI |

-100 |

0 |

NI |

|

Wales total |

- |

150 |

228 |

236 |

NI |

+57 |

+3 |

NI |

|

- |

Anglesey |

13 |

39 |

40 |

NI |

+207 |

+3 |

NI |

|

- |

Caernarfon |

56 |

84 |

87 |

NI |

+55 |

+4 |

NI |

|

- |

Denbighshire |

0 |

2 |

2 |

NI |

Increase |

0 |

NI |

|

- |

Meirionnydd |

8 |

20 |

18 |

NI |

+125 |

-10 |

NI |

|

- |

Montgomery |

4 |

1 |

0 |

NI |

-100 |

-100 |

NI |

|

- |

Ceredigion |

15 |

25 |

27 |

NI |

+80 |

+8 |

NI |

|

- |

Pembrokeshire |

53 |

59 |

58 |

NI |

+9 |

-2 |

NI |

|

- |

Glamorgan |

1 |

3 |

4 |

NI |

+300 |

33 |

NI |

|

England |

Cornwall |

0 |

1 |

7 |

23 |

Increase |

+600 |

229 |

|

Northern Ireland |

Antrim (Rathlin Island) |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

-50 |

0 |

0 |

|

Isle of Man 2014/15 |

- |

68 |

128 |

133 |

NI |

+94 |

+16 |

NI |

|

UK and Isle of Man total |

- |

302 |

429 |

433 |

NI |

+34 |

+3 |

NI |

(Adapted from Hayhow, 2018)

Table 4. Summary of average breeding success in regional populations.

Fledglings/pair are calculated for all available records, for the periods stated, including zeroes for unsuccessful pairs or reporting just from successful nests, depending on what was available or interpretable from data sources. Calculations were simple totals, ratios and/or averages from the available figures, depending on what has been published, attempting to convert all into the same scale. However, details of how ‘pairs’ were defined were not available for many datasets and probably varied (see main text), meaning that it would be unwise to interpret regional differences in detail. Some calculations used annual totals of chicks and nests, and some annual records of productivity, which in turn could have been reported per nest or per local population. Figures may not match those in other publications because calculations have been done differently (if in doubt, take values from the primary sources, not here). Ranges reflect summaries of minimum and maximum annual values across years. Averages across years are weighted by the sample sizes in each year (so, for example, the Cornwall data are dominated by the latter years in the time series). Standard errors are provided where they could be estimated from the data that were available, derived from whole samples or, mostly, from annual averages; they should therefore be treated with caution as they represent under-estimates of the true variation in most cases.

|

Region |

Years measured |

Total no. of nests |

No. successful (No. of broods) |

Fledglings per pair (SE) Including zeroes |

Fledglings per pair (SE) Excluding zeroes |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scotland - Islay |

2010-2018 |

538 |

287 |

1.29 (?) |

2.41 (?) |

Trask et al. (2020) |

|

Scotland - Colonsay |

1990-2018 |

289 |

- |

2.00 (?) |

- |

Jardine et al. (2019) |

|

Isle of Man |

2002-2016 |

459 |

401 |

1.95 (0.35) |

2.24 (0.37) |

Moore (2006-2020) |

|

Cornwall |

2002-2021 |

204 |

112 |

2.10 (1.27) |

3.08 (0.37) |

CBWPS (2021) |

|

Ireland* |

2002-2003 |

- |

98 |

- |

2.43 (1.23) |

Gray et al., (2003) |

|

Wales - Gower |

1992-2020 |

73 |

- |

1.62 (?) |

2.51 (0.41) |

Hodges and Haycock (2020) |

|

Wales - Pembrokeshire |

1992-2020 |

1675 |

- |

1.64 (?) |

2.54 (0.28) |

Hodges and Haycock (2020) |

|

Wales - north and mid-west |

2011-2020 |

1666-1831 |

680-845 |

- |

2.96 (0.07) |

Cross and Stratford chough project |

* Additional breeding success information is reported in Boylan, M. (2011) The ecology of the Chough in south west Ireland. PhD Thesis, National University of Ireland, Cork (S. Cummins, pers. comm. 2023). However, the thesis is not published and was not available at the time of writing. The summary data of which we are aware are not in a format that allows incorporation or conversion to match the figures in this table, but this might perhaps be possible with access to the thesis.

3.2.1 Scotland

There is evidence to suggest that chough populations have had a long history of decline and recolonization throughout much of Scotland, (e.g. records as far south as the borders (1867) and as far north as Orkney during the Iron Age) (Forrester et al., 2007). Between the 1963 and 1992 censuses, the Scottish population had increased from 11 breeding pairs in 1963 (Rolfe, 1996) to 88 pairs by 1988 (Monaghan et al., 1989). However, the population then declined from the 1992 census period onward, while all other populations, until recently, (except for the very small Northern Irish population) were undergoing population increases. As a result, the breeding range of Scottish chough retracted to just three islands (Islay, Colonsay and Oronsay) within this period, having recolonised these islands in the mid-1960s, with the last breeding occurrence prior to this in the early 1900s (Thom, 2010). They also previously bred on the islands of Jura and Mull, and on the mainland in Dumfries and Galloway at the time of the 1992 census, and also on Kintyre from 1964-83. Since the last census in 2014, numbers are believed to have stabilised to some degree due to supplementary feeding and successful treatment of parasites (Trask et al., 2020), but the population continues to remain particularly vulnerable, due to its restricted breeding range, and recruitment of young birds into the breeding population remains low. Islay remains their stronghold, supporting a relatively stable population of c.50 breeding pairs since 2000, which constitutes c.80% of the Scottish population (Monaghan et al., 1989; Finney and Jardine, 2003). The Colonsay and Oronsay population densities have remained relatively low compared to Islay, with a peak breeding population of between 15 and 20 breeding pairs between 2000 and 2010, but have seen a gradual decline since then (Jardine et al., 2019), down to 3-4 pairs in 2023 (D. Jardine, pers. comm., 2023).

Fledging success data were obtained from the Annexes to Trask et al. (2020) and a Scottish Chough Study Group submission to the 2020 Scottish Chough Forum (M. Laurie, pers. comm., 2022). In 1998, an average of 2.07 (± 0.19 se, n=43) fledglings per breeding pair were produced on Islay and 2.78 (±0.40 se, n=9) on Colonsay. No significant differences in fledgling success between these two islands was evident, while Jura and Galloway only had a single breeding pair, producing two and four fledglings, respectively, and a single breeding pair on Mull did not produce young (Cook et al., 2001). In the long-term data, there was some evidence that breeding success has been higher on Colonsay than on Islay in recent years, but differences are marginal and potentially influenced by differences in the definition of zero success nests (Table 4, Table A1 and Table A2). In general, however, breeding success in Scotland appears somewhat lower than in some other regions (albeit with the same caveat about data interpretation). In Scotland, chough are a qualifying species in Special Protection Areas (SPA), listed in Annex I of the Birds Directive.

3.2.2 Ireland

The overall trend for Ireland is considered to be one of relative stability with fluctuating breeding numbers either side of the 2002/3 census, , with a reported, small, overall breeding population decrease of 10% between the 1992 and 2021 censuses. However, most recently, there have been notable gains and losses recorded at the county/local level, with a suggestion of a north-south divide, with the exception of Kerry. The historical stronghold of Cork has experienced a recovery following a decrease in 2002/3 census and has increased by 29%. In contrast the neighbouring county of Kerry (the second largest historical stronghold), has undergone a significant decrease of 52%. Conversely, Clare to the north has seen 182% and 63% increases, respectively, from the last two census periods. Waterford and Wexford, situated on the south coast, have also reported gains since 2002/3, 127% in Waterford and from zero to four breeding pairs in Wexford, such that numbers are now similar to those in 1992. The overall trend appears to be one of decrease north of Clare and up to Donegal. Although having historically smaller population sizes, Galway, Mayo, and Sligo have all undergone continued small declines from the previous two censuses. Donegal (the northernmost county) has seen a 44% reduction in numbers since 2002/3 and the highest range losses in terms of birds occupying 10-km survey squares from the 2021 census, compared with the Breeding Bird Atlas (2007-11) distribution, such that numbers are now similar to those in 1992. Leitrim has retained a single breeding pair, following an increase of three breeding pairs between the previous two censuses (Colhoun et al., 2023).

In recent decades, chough have successfully recolonised and established breeding populations on the British mainland – first on the Gower peninsular, in south Wales from 2000, and then in Cornwall in 2002, for which there is evidence to suggest they originated from Ireland (Wenzel et al., 2012). This significant range expansion, in parallel with stable breeding numbers, suggests that the Irish chough population was in relatively good health during this time period. During the 2002-03 census the average number of fledglings per successful pair was 2.43 (±1.23 se, n=98) (Gray et al., 2003). This value is not one of the higher ones among regions (Table 4), but has a large standard error, indicating high variability.

3.2.3 Wales

Wales holds around 75% of the UK chough breeding population. Available data shows an overall upward trend in Wales from the last three censuses, although only a relatively small increase over the period 2002-2014. Likewise, the historical trend from 1963 onwards has been positive for all census periods. However, there is strong variation in regional trends with declines in some areas and particular concern about falling numbers of chough breeding inland in north and mid-Wales (Cross et al., 2020; Haycock et al., 2021). Caernarfon continues to retain the largest population with a 55% increase between 1982 and 2014, with a suggestion of a levelling-off in recent years. Pembrokeshire has remained the most stable population out of all the Welsh counties, varying between 50-60 pairs between 1992 and 2014. Out of those counties that had double-figure breeding pair numbers recorded from the 1992 census, the population on Anglesey has undergone the sharpest increase, with 40 breeding pairs in 2014, representing a +207% change, and has remained stable since (Cross et al., 2020). The counties of Ceredigion, Glamorgan, Meirionnydd and Denbighshire have seen their populations remain broadly stable throughout all periods. However, Montgomeryshire had lost its last remaining breeding pair between the 2002 and 2014 census periods (Table 3).

In Pembrokeshire, the chough population has been monitored since the early 1980s (Table 3, A4). The main focus of this work is on distribution, demography and productivity, in line with the Chough Conservation Strategy for Pembrokeshire (Hodges, 1994). A particular focus of this monitoring of the breeding population within the National Park is on the islands of Skomer and Skokholm, and the Seas off Pembrokeshire SPA. Similar work is carried out in the Ramsey and St David’s Peninsula Coast SPA and the Castlemartin Cliffs SPA. These three Pembrokeshire sites are part of the Natura 2000 network of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and SPAs for which chough are a qualifying species. Annual nest monitoring has taken place since 1992 (Table A4; see Haycock et al., 2021 for detailed reporting). The most successful nesting year was in 2020 (61 of 73 recorded nests fledging 169 young), and an apparently high level of productivity compared to other regions (c. 2.5 fledglings per successful nest: Table A4). Productivity in 2020 (2.8 fledglings per breeding pair) was above the 29-year average, and the minimum number of fledged young was the highest ever recorded (Hughes, 2020). The lowest year of productivity recorded was 1993, but this was due to incomplete survey coverage in that year (Hodges and Haycock, 2020, Haycock et al., 2021). (The specific data shown graphically in Haycock et al. (2021) were not available for re-analysis, so Tables 4 and A4 are based on the figures that could be extracted from Welsh Bird Reports for the same period. The data published in the bird reports were not standardised, particularly in earlier years). Chough are also monitored comprehensively across the parts of the range in north and mid-Wales, with annual recording of more than 170 pairs in the counties of Anglesey, Caernarfon, Denbighshire, Meirionnydd, Ceredigion and Montgomeryshire (although zero abundance counts have been recorded in recent years for Montgomeryshire; A. Cross and A Stratford, pers. comm., 2022). The data collected contribute to national totals and the BTO Ringing Scheme database, and are published in Cross et al., 2020. Overall breeding success for this region appears to be high relative to other regions, at least among successful nests. However, between 1994 and 2019 the territory occupation rate declined by 72% in inland areas, and by 12% in coastal areas. This equates to a 27% decline in the breeding population of mid and north Wales. These results add detail to the recent periodic national census results that highlighted some concerning vice-county level changes. Furthermore, nest studies carried out during the ‘Red-billed Chough Research Programme’ found that adult survival in north and mid-Wales is lowest for birds hatched in inland areas and highest for birds hatched in coastal quarries. However, there was a marked decline in the survival of first breeding year adults (from 90.2% in 1993-99 to 75.1% in 2014-19). There was also a marked decline in the rate of recruitment of new breeding adults especially to inland breeding territories, which suggests survival around the time of recruitment to the breeding population as a period of potential demographic stress for the Welsh Chough population. Declining recruitment to the breeding population, increasing mortality affecting first-time breeders and declining productivity and nest success rate may collectively explain observed patterns in territory occupation rates (Cross et al., 2020).

3.2.4 Isle of Man

Available census results show that since the 1992 census, the Isle of Man has seen an overall positive trend in breeding numbers with an 88% increase between the 1992 and 2002 censuses, which had tailed-off to a slower rate of a 16% increase by the 2014 census (Table 5). The Isle of Man population has remained stable, particularly on the Calf of Man, where breeding numbers have remained identical (n=14 pairs) between the last two census periods. The most notable increase has been the re-colonisation of the northern part of the island, with six breeding pairs recorded during the last census. All regions have maintained relative stability between 1992 and 2014-15 censuses, apart from the west where there has been a degree of fluctuation (Table 5).

Table 5. Total breeding pairs from Isle of Man censuses 1992 to 2014-15.

|

Region |

1992 |

2002 |

2014-15 |

% change 1992 – 2014/15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

West |

23 |

42 |

31 |

+35 |

|

Calf |

8 |

14 |

14 |

+75 |

|

South |

11 |

40 |

46 |

+264 |

|

East |

30 |

46 |

52 |

+73 |

|

Inland |

5 |

8 |

11 |

+120 |

|

North |

0 |

0 |

6 |

+600 |

|

Total main island, not including north |

69 |

136 |

140 |

+100 |

|

Total |

77 |

150 |

160 |

+30 |

(Moore, 2018)

Annual nest productivity data have been published by Moore (2004-2020), allowing fairly strong summary analyses to be conducted. These suggest that average breeding success has been lower than in some regions, but probably higher than that in the Scottish population (Table 4). There is no clear evidence of a temporal trend in breeding success among Isle of Man chough (Table A3). However, anecdotal evidence now suggests that chough may be in decline, as indicated by a discernible downward trend in maximum flock sizes observed over the last four years, and the 2021 Birds of Conservation Concern in the Isle of Man listed Chough as Amber (N. Morris pers. comm., 2022).

3.2.5 England

Historically, chough were widespread along the south and southwest coasts of England before numbers started to decline in the 1800s. The last breeding occurrence was in Cornwall in 1947 (Carter et al., 2003), until a breeding pair naturally recolonised the area in 2001 and successfully raised three young the following year. DNA analysis of feather samples showed that this pair had originated from southern Ireland (Wenzel et al., 2012).

Breeding chough in England have undergone a near-continuous population increase since the recolonization in 2001. An annual population increase has been observed, with the exception of 2017 (as a result of bad weather during the nesting period). The 2022 breeding season was another successful year for Cornish chough, and the trend is forecast to continue as there is plentiful, suitable, available habitat into which their breeding range can expand along the Cornish coast and as breeding numbers have now reached the threshold (20-30 breeding pairs) of what is considered a self-sustaining population by the RSPB (Table A5): the recent trend looks positive, with 70 fledglings raised from 25 pairs in 2022 (CBWPS, 2022). There is a suggestion of a reduction in fledgling success rate in recent years, although the sample size is too small to infer a genuine change in nest productivity at this stage. Additionally, initial breeding success was high relative to that in other regions, as is the overall mean of 3.08 chicks per nest fledged across all years and for all successful nests (Tables 4 and A5).

3.2.6 Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland had supported a single breeding pair between 1992 and 2002 (Gray et al., 2003), with the last breeding occurrence in 2017 on Rathlin Island. The pair often wintered along the mainland Antrim coastline and, although this was not confirmed, was believed to commute to Donegal in the Republic of Ireland. Any sightings of the species remain very scarce in Northern Ireland (McClure pers. comm., 2022). The breeding success of these birds was not measured, but was probably low, unless most fledglings emigrated to other populations.

4. Review of the evidence for the influences of biotic and abiotic factors (and interactions between them) on chough population dynamics

To be effective, chough conservation measures need to be designed to counter the influences of negative factors for population change and to promote or at least not to negate the influences of positive factors. The important influences could be ecological (biotic) or physical (abiotic), and could act via interactions between diverse influences, such that the likely success of management measures varies considerably between contexts. Multiple factors affecting chough populations are well documented, and it is unlikely that a single factor in isolation is influencing population dynamics for all regions where they occur (Table 6). Although chough in the British Isles are predominantly found in rocky coastal habitats, some nest further inland in quarries, derelict buildings or agricultural structures. Some have access to arable land as well as a variety of grassland types. Hence, the pressures and influences on different populations will vary regionally, but the set of factors across all regions should provide a fairly comprehensive guide to the potentially important drivers of habitat suitability and population change in any location.

Table 6. Summary of biotic and abiotic factors, their effects and consequences, and conservation measures.

All were identified in both published and grey literature; biotic and abiotic factors are as considered to be either probable or potential causes affecting chough populations by region; the conservation measures have been implemented in response to these factors.

|

- |

Factors influencing chough population |

Effects/Consequences |

Conservation measures currently implemented |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scotland |

Loss of low intensity livestock grazing |

Reduced first year survival rates |

Year-round cattle grazing |

NatureScot |

|

- |

Lack of food availability and decrease in foraging opportunity |

Decrease in first year survival rates |

Supplementary feeding programme 2010 (Islay) |

NatureScot |

|

- |

Veterinary pharmaceutical practices (anthelminthic treatments) |

Decrease in dung invertebrates as food |

- |

Reid et al., 2009 |

|

- |

Mechanical vegetation topping |

Destruction of dung pats and associated insect food prey |

- |

Reid et al., 2009 |

|

- |

development and forestry activities |

- |

- |

Reid et al., 2009 |

|

- |

Inbreeding |

Low genetic diversity – reduced viability |

- |

Wenzel et al., 2012 |

|

- |

Increased tourism |

Disturbance to nesting and foraging birds |

- |

McKay, 2007, Hayhow et al., 2018) |

|

- |

Climate: Increased heavy rainfall events projected for Scotland |

Decrease in nesting success rates |

- |

NatureScot, SAC Chough Conservation Paper |

|

- |

Parasite burdens |

Clinical and sub-clinical effects on fitness in some birds. |

Treatment for parasites |

NatureScot, SAC Chough Conservation Paper |

|

- |

Climate |

Bad weather late spring effecting nesting success, summer droughts, extended cold periods reducing foraging ability. |

- |

Reid et al., 2009 |

|

England |

Human disturbance |

Decreased foraging time |

- |

Owen 1989, Kerribiriou et al., 2007. |

|

- |

Removal of livestock from cliff edge heath and grassland |

Increased scrub/vegetation height reducing foraging ability. |

Reinstated livestock grazing along the cliff edge and coastal pastures using agri-environment options. |

Cornwall Council |

|

- |

Illegal egg collecting |

Reduced nesting success. |

Round-the-clock volunteer nest surveillance since 2002 |

Cornwall Council |

|

Wales |

Afforestation on unstable bare/clay cliffs |

Increased vegetation and bracken encroachment reducing foraging opportunities. |

- |

Nature Gwynedd |

|

Gwynedd and Pembrokeshire |

Veterinary pharmaceutical practices ‘Avermectins’ administered to coastal livestock |

Decreased insect food availability in animal dung. |

- |

Nature Gwynedd and Chough Conservation Strategy for Pembrokeshire (Hodges 1994) |

|

- |

Natural predators (Peregrine) |

Disturbance to communal roosts and affecting fledgling success. |

- |

Nature Gwynedd and Chough Conservation Strategy for Pembrokeshire (Hodges 1994) |

|

Gwynedd |

Mining/quarrying activities |

Destruction or disturbance of nest sites. |

Nest site protection in working quarries during the breeding season; Safeguard potential nest sites/communal roosts from certain development or mining. |

Nature Gwynedd (Species Action Plan for Chough) |

|

- |

Recreation activities – climbing, ramblers, bird watchers, paragliders |

Disturbance to nesting and foraging birds. |

Liaison with British Mountaineering Council |

Nature Gwynedd (Species Action Plan for Chough) |

|

Pembrokeshire |

Coastal scrub encroachment |

Reduced foraging opportunities. |

Controlled winter burning of Gorse |

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Gwarchod y Park; Conserving the Park 2003-2018, |

|

- |

Illegal egg collecting |

Reduced fledging success |

- |

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Gwarchod y Park; Conserving the Park 2003-2018, |

|

- |

Cliff-top recreation activities |

Disturbance to foraging and disruption of social behaviour |

- |

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Gwarchod y Park; Conserving the Park 2003-2018, |

|

- |

Climate related |

Spring storms impact foraging time. Nests get washed out. Under-weight chicks get water-logged and chilled causing death. |

- |

Chough Conservation Strategy for Pembrokeshire |

|

- |

Reduced genetic diversity |

long-term health and resilience of the population |

- |

Wenzel et al., 2012 |

|

- |

Possible predators (fox, weasel, stoat, ferret, polecat) |

Predation of eggs and chicks could occur (not quantifiable) |

- |

Chough Conservation Strategy for Pembrokeshire |

|

Northern Ireland |

Removal of grazing from grassy cliff slopes |

Loss of short well-grazed turf and bare ground |

- |

Allen and Mellon, 2021 |

|

Antrim (Rathlin Island) |

Illegal shooting (Rathlin Ireland) |

Accelerated population decline |

- |

Allen and Mellon, 2021 |

|

Antrim |

Intensification of grassland management and removal and loss of stubbles. |

Loss of winter foraging opportunities |

Local farmers have all contributed to the creation of more favourable foraging conditions through chough targeted agri-environment options. Introduction of chough ‘prescriptions’ on the Antrim Coast |

Allen and Mellon, 2021 |

|

- |

Recreational rock climbing |

Potential Nest disturbance causing reduction in nesting success |

- |

Allen and Mellon, 2021 |

|

Ireland |

Abandonment of land |

Loss of suitable foraging habitat if land is left unmanaged. |

- |

Gray et al., 2003 |

|

Cork (Dursey Island) |

Tourism/development |

Disturbance to foraging and nesting from proposed cable car from Irish mainland to Dursey Island |

- |

Cork County Council Appendix D – Post-breeding chough survey report |

|

Isle of Man |

Low genetic diversity |

Reduced viability |

- |

Wenzel et al., 2012 |

A wide range of biotic and abiotic factors could influence chough, notably (abiotic factors) climatic conditions, seasonal weather conditions, nest site availability (buildings, quarries, sea cliffs and cavities within them), and soil type and health (acidity, nitrogen and phosphorus levels), as well as (biotic factors) sward structure and the effects of grazing of different wild and domestic mammals (i.e. land-use), genetics, avermectin or other veterinary pharmaceutical contaminants, soil biodiversity and abundance (i.e. food availability) and its drivers, and interactions with other wild species (including disease, competition and predation). We consider the evidence for all of these below. We do not separate further into biotic and abiotic factors because the lines between them are blurred in some cases, and interactions may be common.

4.1 Land-use and foraging habitat characteristics

The requirement for suitable foraging habitat, close to nesting sites and within the dispersal range of young, will be the single most important factor influencing both the presence and productivity of chough in any given region, as it is for any breeding bird. Chough foraging ecology means that year-round access to insects is critical, chiefly via short-grazed swards, together with the availability of dung invertebrates and, locally, specific habitats such as silage fields, stubbles and the strand line, at different times of year (e.g., Coombs, 1978; Bignal et al., 1989). Of particular importance on Islay are coastal dune systems and cut silage fields, which have been shown to support c.90% and 10% of foraging flocks of chough, respectively (Reid et al., 2009). Within the dune systems, they utilise grazed and largely ungrazed dune grasslands, kelp beds, bare sand, cliff and heath habitats. The sandy areas can be an important source of mining bees, which can provide food for much of the year (Clarke & Clarke, 1995). Newly-cut silage fields provide a rich source of food for fledgling and sub-adult choughs in June to August, when sub-adult mortality can be high. Availability of dung insects is recognised as an important component of chough foraging and diet (Warnes & Stroud, 1989; McKay, 1996; MacGillivray et al., 2018). Hence, land-use providing such resources is a prerequisite for chough presence and persistence in an area, and change in land-use is likely to have a negative impact.

Afforestation is a major current and ongoing form of land-use change. Although its potential effects on the Islay chough population were acknowledged in the 1980s (McKay, 1996), there is no recent evidence to suggest that loss of foraging habitat due to afforestation is driving their population decline throughout the UK and Irish range. However, there are concerns that this may become a significant pressure on Islay in the future. Although there is very little land on Islay that offers more than moderate potential for the establishment of tree crops (Soil Survey of Scotland Staff, 1988), there are signs that carbon off-setting and rewilding could incentivise planting (D. Parish, pers. comm., 2023). Furthermore, there appears to be no evidence suggesting that urbanisation or other forms of non-agricultural land-use are also contributing factors to change on Islay, or elsewhere. However, land-use change that is more subtle may be more significant for chough. In Scotland, increased afforestation around the coast could be a threat to chough foraging opportunities, as a result of both reduced land availability for foraging and increased competition from rooks, especially in foraging areas adjacent to communal roosting or breeding sites.

On Islay, livestock numbers across the island have changed since the 1980s, broadly in parallel with the decline in chough numbers. Fewer farms in key chough areas kept sheep and cattle in 2013, compared with 1989 (Gilbert et al., 2019a), and the average stocking density of farms on Islay is substantially lower than that of other parts in the British chough range with healthier populations (Jonsson et al., 2020). This reflects a long-term trend for reduced stocking densities of both cattle and sheep across Scotland, although numbers may have stabilised recently, to a degree, due to agri-environment and subsidy payment structures, as well as farm economics (Brak et al., 2004; Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services Division, Scottish Government, 2021). Further, the relationship between stocking rates and first-year survival rates of chough on Colonsay and Oronsay may be significant. The shift in farm subsidies in 2003 brought a reduction in both sheep and cattle on the islands, which resulted in a widespread loss of the short-cropped turf that is favoured by foraging chough at several cliff-top and dune-system localities. This occurred concurrently with the increase in juvenile chough mortality that supplementary feeding has been shown to mitigate, suggesting a causal link involving food availability (Jardine et al., 2019). While many aspects of biodiversity benefit from reduced farming intensity (Brak et al., 2004), chough foraging requires the short, open swards that high grazing pressure provides and livestock dung further increases the availability of invertebrate food resources (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2019a). Therefore, falling stocking densities, as on Islay, could have had significant impacts on habitat quality for chough. The further reduction in stocking rates is still of concern on Islay and Colonsay, with several local, recent examples of stock removal (D. Parish, pers. comm., 2023). Further losses of stock would likely lead to gross land-use change from land abandonment, with further, but different negative effects on chough. This may be facilitated by the aging profile of farmers on Islay (Brak et al., 2004).

Although the importance of livestock grazing for creating and maintaining short swards and open, bare patches has been established, there has been much less attention paid to other forms of grazing – notably rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus. McCanch (2000) found that high rabbit populations correlate with large chough brood sizes and foraging success on the Calf of Man (Isle of Man). The strongest correlation was found between the decline in the chough breeding population, and the outbreak of myxomatosis, even when sheep (Loaghtan) grazing numbers were consistently maintained through the study period. Moreover, when the chough population began to recover after 1970, the effects of myxomatosis on the rabbit population were also reducing. The recovery of the Chough population after 1970 corresponds with a change in the effects of myxomatosis outbreaks, probably as a result of the virus being replaced by a less virulent strain, which subsequently became endemic in the local rabbit population. The study suggests that rabbit grazing is as effective as sheep grazing for maintaining the sward characteristics favoured by chough, although they do not contribute to the preferred dung fauna.

4.2 Climate, weather and food availability

In general, British chough, and Scottish chough in particular, are at the northern limit of the species’ range, so climate change might be expected to have presently had, and to continue to have, a positive effect on habitat suitability, allowing northward spread. Moreover, conditions on the edge of the range must always be marginal for a species, all other factors being equal, so we would expect birds there to be the most vulnerable to any stress factors. However, longer-term climate change projections for the UK have indicated wetter winters and drier summers on average, and an increase to the frequency of extreme weather events (Humphrey and Murphy, 2017). Whilst accurate predictions of the severity and location of these weather effects are not available, it is conceivable that changes in weather will be likely to influence chough prey availability and foraging efficiency during periods of heavy and persistent rainfall, especially if they occur at sensitive times of year. Young chough survival rates on Islay are lower in years with higher rainfall totals, when they coincide with the pre-breeding period in late winter and spring, which likely leads to reduced prey availability (Reid et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2008). Specifically, survival of chough fledglings was higher in winters when cranefly (Tipulidae) larvae were more abundant and when previous weather conditions supported increased overall insect prey availability (Reid, 2008). McKay (1996) suggests that the relationship between the climate and the chough’s distribution in the UK probably results from the effects of climate on the growth, mortality and productivity of the invertebrate populations which form their diet. Alternative food sources, such as mown silage fields, low-input arable crops or strand-line wrack, could be critical for buffering local populations against fluctuations in food accessibility in grassland. Although the availability of silage aftermath could be extended by spreading cut dates, these sources are ephemeral or unpredictable, so are only likely to be a supplement, rather than a core resource.

Hayhow et al. (2018) suggests that climatic conditions affecting chough populations in the south (Glamorgan and Pembrokeshire) may have changed to benefit chough in recent years, perhaps contributing to the increases in survival rates and breeding success reported in these areas. Recent mild winters have brought stability to the Pembrokeshire chough population by increasing survival rates of first-year birds. However, extreme weather events in spring and summer can have a severe impact on the population, especially via breeding success. Prolonged strong winds can reduce foraging opportunities throughout the year and heavy rainfall may waterlog nests and kill young. Conversely, prolonged periods of drought can be detrimental for foraging, as the soil may become too dry and firm for chough to feed effectively (Hodges, 1994). In general, such extreme weather events are likely to have a population impact only if they are repeated or prolonged, as numbers may recover quickly if more clement weather allows productivity to improve in subsequent years. Such a change in frequency of extreme events is predicted to occur under climate change; therefore, it is important to consider the possibility that effects of climate will become more apparent and more significant in the future. Note also, that effects could be subtle, such as maritime storm severity and frequency affecting both the accumulation of tideline wrack and its dispersal, perhaps before it can accumulate any invertebrate fauna.

4.3 Use of livestock veterinary pharmaceutical treatments

Following a review of grazing intensities on foraging habitats throughout the chough’s UK range, Jonsson et al., (2020) suggest that higher intensity grazing is preferable, in conjunction with lower rates of avermectin-based treatments for livestock. Macrocyclic lactones, such as avermectins, have long been associated with having lethal and sub-lethal effects on dung-associated invertebrates (Wall and Strong, 1987; McCracken, 1990; McCracken and Foster, 1993). Changes in chough diet on Islay from the 1980s to 2010s, showing a marked reduction in the presence of dung beetle larvae (MacGillivray et al. 2018), are consistent with such an effect following through to an effect on the birds, although this may also reflect the decline in cattle numbers. However, Beynon et al. (2012) found that other parasite-control products (anthelminthics), such as synthetic pyrethroids (SP) (alternatives to avermectins), can also affect invertebrates colonising dung, highlighting the need for testing to be carried out on their environmental effects. In Jonsson et al.’s (2020) review, 63 farms that regularly supported foraging chough were assessed, showing significant differences between chough populations in how farmers graze their land. Farmers on Islay, Colonsay and Oronsay (ICO) were found to administer between four and 13 times more SP treatments to cattle per year than all other regions within their breeding range. Avermectin-based veterinary drugs, for example, have been shown to be lethal to insects inhabiting dung (Lumaret and Errouissi, 2002), and affect many aspects of insect reproduction, including mating behaviour, egg development, oviposition and egg hatching at a sub-lethal level (Strong and Brown, 1987). Webb et al. (2006) suggest that these treatments could affect quantities of larvae present in dung to a degree that could increase the time these dung feeding specialists (e.g., chough, lapwing and redshank) need to spend foraging to obtain sufficient food during key chick development stages. ICO farmers were also found to treat sheep with the highest applications of triclabendazole out of all the other regions in the study (Jonsson et al., 2020). Both SP and triclabendazole products were found to reduce numbers of arthropod larvae found in livestock faeces significantly, during a study into the effects of macrocyclic lactone treatments for livestock on Islay (Gilbert et al., 2019b), although Sands & Wall (2018) found that farms that used SP had similar dung beetle diversity to farms that did not use parasiticides, with their effects being less pronounced than those of Avermectins.

4.4 Genetics

The UK and Irish chough populations are fragmented and isolated, and have been shown to be connected by infrequent and depauperate gene flow, with low genetic diversity reported throughout the north-west European population (Wenzel et al., 2012). Wenzel et al. (2012) reported a genetic diversity gradient from Brittany (highest diversity) to Scotland and Isle of Man (lowest diversity). While there has been some cross-infiltration of chough populations throughout the Irish and UK range in recent decades (e.g., between Isle of Man and North Wales; (Moore, 2006, 2008)), genetic viability remains a concern amongst the smaller populations. Chough in Scotland are closely related, and genetic abnormality is suspected as the cause for blindness in a small proportion of nestlings on Islay and Colonsay (Trask et al., 2016). Most of the Cornish population have descended from the original three birds in 2001 and, consequently, genetic viability continues to remain a concern in the long-term (Mitchell pers. comm., 2021). The extent to which low genetic variability is affecting population dynamics across the UK range is uncertain. There is currently no published, specific, information relating to the genetic viability of the birds used in the Jersey reintroduction programme, but the programme occurs within a context of zoo-based captive breeding, in which management of genetic diversity is a regular focus. Wenzel et al. (2012, 2015) suggest that UK populations are the least diverse in Europe (including island birds in La Palma, Canary Islands, which have been sustained by multiple colonisation events), so may require genetic management intervention to ensure long-term viability. The extent of dispersal among British and Irish birds remains unknown, but could clearly be a critical determinant of genetic population structure. Growing numbers of colour-ringed birds in various populations may offer an opportunity to investigate this further using targeted resighting effort.

4.5 Diseases