NatureScot Research Report 1281 - Approaches to monitoring wintering waterfowl in Marine Protected Areas - Moray Firth pilot study winter 2019/20

Year of publication: 2023

Authors: Jen Graham and Kate Thompson (NatureScot)

Cite as: Graham, J. and Thompson, K. 2023. Approaches to monitoring wintering waterfowl in Marine Protected Areas - Moray Firth pilot study winter 2019/20. NatureScot Research Report 1281.

Keywords

seaduck, divers, grebes, inshore wintering waterfowl, European shags, citizen science, monitoring, Marine Protected Areas, Moray Firth Special Protection Area

Background

This report summarizes a programme of work undertaken to investigate different methods of monitoring inshore wintering waterfowl (divers, grebes, seaduck and European shag) in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Using the Moray Firth Special Protection Area (SPA) as a pilot area data were collected in the winter of 2019/2020 on the site’s 11 wintering qualifying features: great northern diver, red-throated diver, Slavonian grebe, greater scaup, common eider, long-tailed duck, common scoter, velvet scoter, common goldeneye, red-breasted merganser and European shag.

The focus of this report is the development, trial and evaluation of a bespoke Citizen Science Pilot survey to survey these birds. A separate report commissioned by NatureScot (Scott et al., 2022), details simultaneous digital aerial surveys and the development of analyses for comparison of data from these aerial surveys, the Citizen Science Pilot surveys, the Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) and, historic vantage point surveys undertaken by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB).

This report applies the analyses developed by Scott et al. (2022) to all 11 wintering features and presents comparisons that inform recommendations on approaches to future monitoring of populations of wintering divers, grebes, seaduck and shags in MPAs.

Main findings

- Shore-based vantage point surveys were undertaken by citizen science volunteers across the Moray Firth SPA on 19th January and 8th March 2020, coincident with digital aerial surveys completed by HiDef Aerial Surveying Limited. (Scott et al., 2022). Field tests were undertaken in March 2020 to investigate differences between observers.

- 48 vantage points were surveyed in January and 28 in March. In total 10,806 birds were detected in the January survey and 11,072 in March.

- Relationships were characterised between: the aerial survey bird density models and the Citizen Science Pilot counts; the Citizen Science Pilot counts and contemporary WeBS counts; and, historic WeBS and RSPB shore-based (vantage point ) counts.

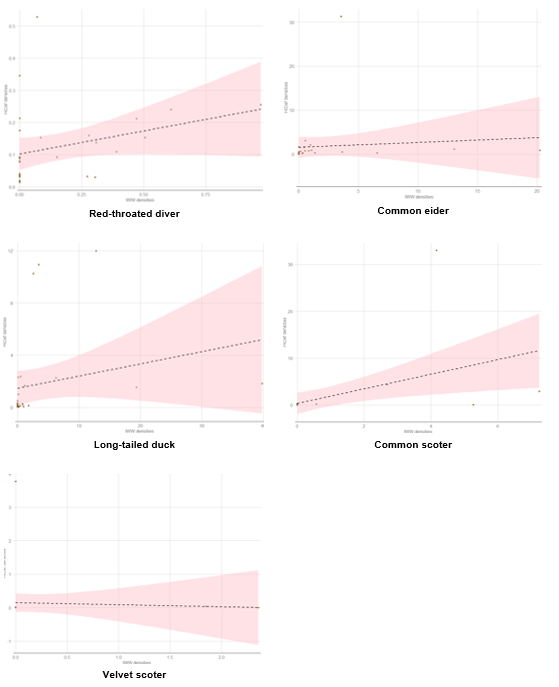

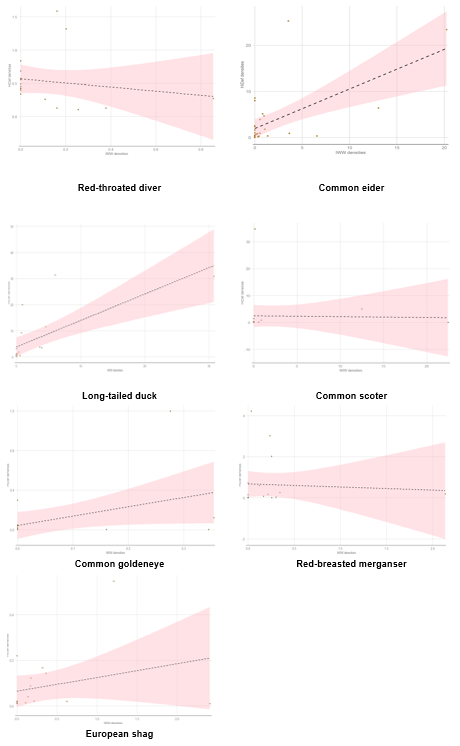

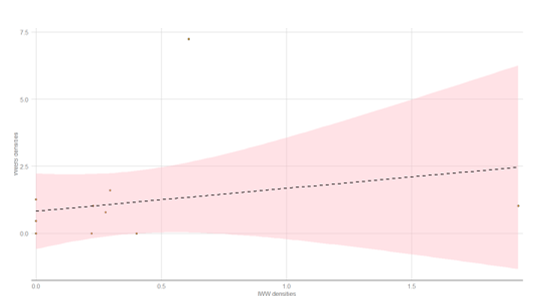

- Relationships between density estimates derived from the Citizen Science Pilot surveys and the Bayesian Model (derived from digital aerial survey data), were generally weak. However, distributions generally appear similar in inshore waters, which supports citizen science surveys as a means of understanding inshore distributions of these species.

- Comparative analyses between Citizen Science Pilot surveys and WeBS surveys in January 2020 were based on limited data and were inconclusive. However, historic targeted shore-based counts undertaken by the RSPB show moderate correlations with WeBS counts in the Moray Firth in the two sub-sectors analysed, suggesting that there is a relationship between the survey types for some species. The comparisons suggest that the RSPB shore-based counts provided consistently higher detection rates than WeBS counts in the same months.

- Volunteer feedback suggests that there is appetite for a bespoke long term monitoring of inshore wintering waterfowl (IWW) in the Moray Firth by Citizen Scientists.

- A suite of recommendations is made on the types of survey which are likely to yield the best detection rates for each of the qualifying features as well as on future monitoring of IWW in MPAs and further analysis of existing data sets.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the dedicated and enthusiastic volunteers, without whom this project would not have been possible. We would also like to thank the members of the Technical Advisory Group who provided particular assistance with the development and support of the project: Dawn Balmer, Ben Darvill and Liz Humphreys (British Trust for Ornithology), Mark Lewis (Joint Nature Conservation Committee), Colette Hall (Wildfowl and Wetland Trust), Linda Wilson (RSPB), Tom Evans (Marine Scotland), and Alex Banks (Natural England).

Some individuals provided particular advice and support to this project and we would like to thank them specifically: Alex Robbins, David Patterson, Martin Cook and Grant Humphries.

We are also extremely grateful for the support and assistance provided by data providers, as follows:

Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS): Data provided by WeBS, a Partnership jointly funded by the British Trust for Ornithology, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and Joint Nature Conservation Committee, in association with the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, with fieldwork conducted by volunteers. Although WeBS data are presented within this report, in some cases (2018/19 and 2019/20 data) the figures may not have been fully checked and validated. Therefore, for any detailed analyses of WeBS data, enquiries should be directed to the WeBS team at the British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, IP24 2PU ([email protected]).

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB): counts of divers, grebes and seaducks in the Moray Firth provided for the months of November, December, January, and March from 1998 to 2006. These data are reproduced by permission of RSPB. © RSPB 2019. All rights reserved.

Abbreviations

BioSS: Biomathematics and Statistics Scotland

BTO: British Trust for Ornithology

HiDef: HiDef Aerial Surveying Ltd.

IWW: Inshore Wintering Waterfowl

JNCC: Joint Nature Conservation Committee

MPA: Marine Protected Area

RPAV: Remotely Piloted Aerial Vehicle

RSPB: The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

SCM: Site Condition Monitoring

SPA: Special Protection Area

TAG: Technical Advisory Group

UAV: Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

VSAS: Volunteer Seabirds at Sea scheme

WeBS: Wetland Bird Survey

WWT: Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust

Glossary

Inshore Wintering Waterfowl: species of divers, grebes and seaduck, including sawbills, that winter in notable numbers in inshore waters (within 12 nautical miles of the coast).

Marine Protected Area: defined geographical areas of the marine environment established and managed to achieve long-term nature conservation and sustainable use.

(marine) Special Protection Area: a type of MPA classified to protect populations of rare and vulnerable birds and regularly occurring migratory birds of European importance.

Introduction

Scotland’s marine environment is recognised as an area of outstanding importance for a number of European bird species, which use these productive temperate waters in the winter period as an area to moult, roost and feed.

The Birds Directive (EC Directive on the conservation of wild birds consolidated in 2009 as 2009/147/EC2, replacing the original 1979 Directive), requires Member States to establish a national network of Special Protection Areas (SPAs) on land and at sea. This is one of several conservation measures that contribute to the protection of rare, vulnerable and migratory bird species and has been a major driver of UK bird conservation action over the past three decades. In the terrestrial environment, the Scottish SPA network includes breeding seabird colony SPAs and estuarine SPAs for some sea duck and grebe species.

A more recent focus on the marine environment (Marine SPA selection process) has included classification, in December 2020, of 12 marine SPAs in Scotland for the protection of seabirds, divers, grebes and seaduck. Seven of these sites include one or more species of inshore wintering waterfowl (divers, grebes, seaduck) or European shag as qualifying features. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), including SPAs, contribute towards achieving Favourable Conservation Status of vulnerable species and habitats across the Atlantic Biogeographic Region.

One of the conservation benefits of site protection is that the sites are monitored to assess feature condition and whether this is likely to be maintained. Conservation measures seek to address site-specific pressures and to enhance resilience to other anthropogenic threats, including climate change. The development and implementation of such measures requires information on populations and distributions of the qualifying features and the underlying causes of observed changes. Monitoring is also a key component of establishing whether the conservation objectives are being met.

There are significant challenges to monitoring mobile species in large marine sites. Multiple methods are available for conducting counts of waterfowl, such as visual aerial surveys, digital aerial surveys, boat based surveys and shore-based surveys, each of which have inherent strengths and limitations. Consideration of the available techniques and evaluating the most effective survey methods for each qualifying feature is important in order to make informed conservation decisions.

Digital aerial surveys are increasingly accepted as the best method for providing snapshot estimates of numbers and distributions of birds at sea. Using high-quality cameras to photograph or film the surface of the water, this technique is able to sample large marine sites in short time frames, overcoming the challenge of monitoring large expanses of open water. Furthermore, unlike previous visual aerial survey methods using human observers, the greater height at which the survey planes fly limits risk of disturbance to the target species. However, these techniques currently incur high costs, in part arising from the manual analyses of images, and consequently, digital aerial surveys are only likely to be commissioned infrequently, perhaps once every 10 winters per site to inform NatureScot’s Site Condition Monitoring (SCM) programme. The relative infrequency of such surveys therefore presents a challenge in the monitoring of wintering species whose populations and distributions may fluctuate or change significantly within or between winter seasons.

Boat based surveys may provide better identification rates for some species, and in common with aerial methods, also allow the survey of more offshore habitats in comparison with shore- based survey methods. However, boat based surveys are associated with a high disturbance rate, markedly reducing detection of some species such as divers and red-breasted merganser (Mendel et al., 2008; Jarrett et al., 2018), which results in low population estimates for such species. Furthermore boat based surveys are limited in access to the coastline where vessels may not be able to manoeuvre safely. Consequently, boat based surveys may under-record species which are more closely associated with the coast. Given these inherent limitations boat-based survey methods have not been considered further here.

Shore-based surveys are an alternative which are limited in their coverage of more offshore habitats, being restricted to nearshore waters, but can provide excellent value for money and extensive coverage around coastlines. The long-established Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) has provided trends on wetland bird species across the UK using citizen scientists to observe and record species, on a monthly basis (Frost et al, 2017). However, it is recognised that WeBS methodologies have some limitations with respect to surveying marine IWW such as seaduck and divers for example a broader focus on wetland birds such as waders on the shoreline means that more offshore species of IWW might be undercounted (BTO, 2017). A bespoke shore-based methodology could have the benefit of focussing citizen science effort on IWW species and consequently may provide a complimentary method to digital aerial surveys by providing population count data more frequently.

Work program elements and structure

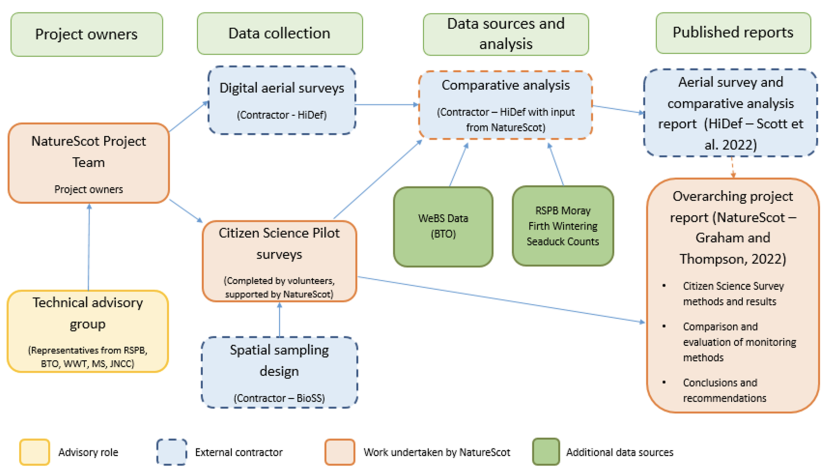

This report describes a program of work undertaken at the Moray Firth SPA in the winter of 2019/2020 to investigate future approaches to monitoring IWW in MPAs in Scotland. This program tied together multiple work packages, as detailed below and illustrated in Figure 2. The focus of this report is the development, trial and evaluation of a bespoke Citizen Science Pilot survey. Throughout this report, reference is made to (Scott et al., 2022), which details coincident digital aerial surveys and the development of analytical approaches for comparison of both contemporary and historic survey data collected using different methods.

The work program was developed by NatureScot, with input provided by a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) set up to advise on various aspects of the work. The TAG was chaired by NatureScot and comprised of representatives from the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), Marine Scotland, Natural England, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT). The TAG provided advice throughout the development and implementation of the project, through meetings and correspondence and provided comments on an early draft of this report.

Using the Moray Firth SPA as a pilot area, data were collected on two occasions in the winter of 2019/2020 using simultaneous digital aerial survey and shore-based vantage point surveys, in order to gain directly comparable counts and trial a novel count method. The digital aerial survey work was commissioned by NatureScot and undertaken by HiDef Aerial Surveying Limited (HiDef) as detailed in Scott et al. (2022).

The shore-based vantage point survey (hereafter referred to as “Citizen Science Pilot”) was developed and led by the project officer, a NatureScot Graduate Placement recruited specifically for this project. Counts were undertaken by volunteers, managed and supported by NatureScot. The spatial sampling strategy for this aspect of data collection was commissioned by NatureScot from Biomathematics and Statistics Scotland (BioSS).

The final element of the work program was development of methods for comparative analyses of these and other data sets completed under a separate contract to NatureScot by HiDef with additional input from NatureScot. The results of the comparative analyses are detailed in Scott et al. (2022), but where relevant are summarised in this report, alongside a detailed evaluation of the Citizen Science Pilot, to inform an overarching evaluation of techniques and discussion of future monitoring approaches of IWW and wintering European shags in MPAs.

The work program was managed by NatureScot, with support from a Technical Advisory Group. NatureScot developed and undertook Citizen Science Pilot surveys, with the help of many volunteers. NatureScot commissioned BioSS to develop the sampling design for the surveys and HiDef to undertake the digital aerial surveys and develop the comparative data analyses which have supported and informed this report. The programme is fully described in the paragraphs above.

The Moray Firth SPA

The Moray Firth is a relatively sheltered, funnel-shaped body of water situated on the north-east coast of Scotland. The Firth is shallow water (less than 20 metres (m) depth) over a sandy substrate (Barne et al., 1996), with a deep channel (50 m) running east-west through muddy substrate (Tilbrook, 1986). Tidal flows are relatively weak with a maximum tidal range of 3 m (Harding-Hill, 1993). The Firth encompasses both an expansive stretch of open sea and a number of smaller firths including the Beauly Firth, Cromarty Firth, Dornoch Firth and Loch Fleet, with multiple tributary rivers, providing input of freshwater.

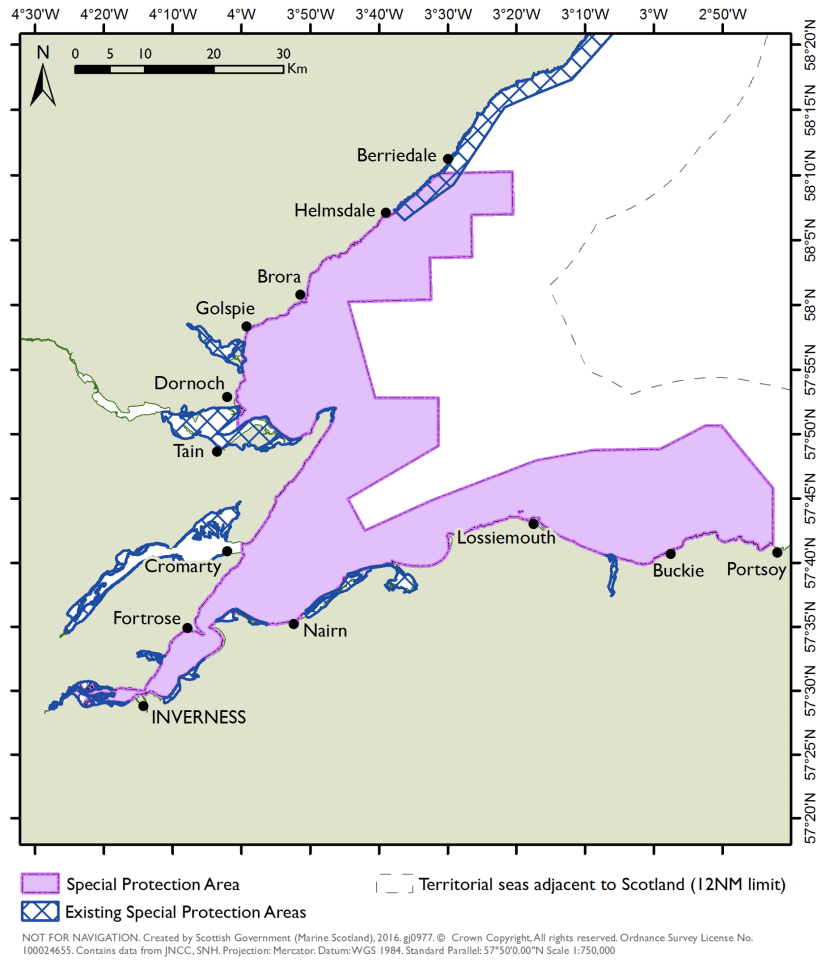

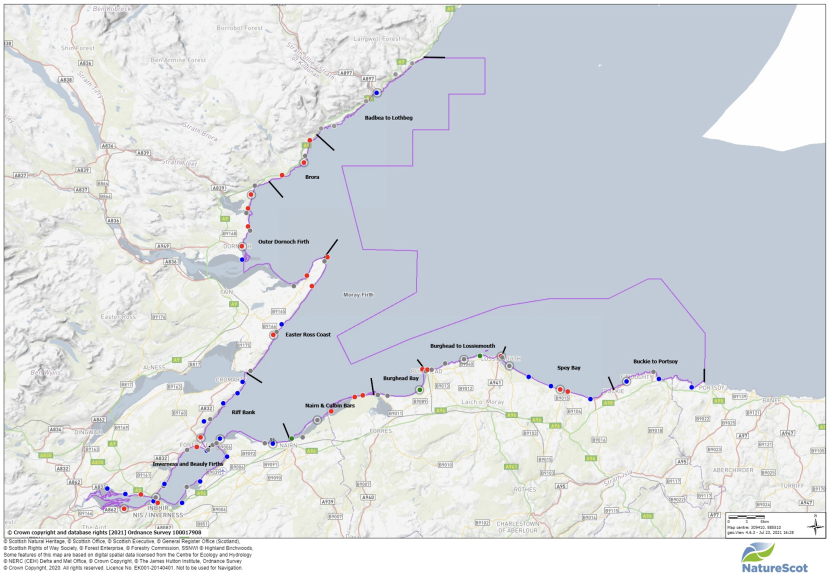

The Moray Firth SPA is an extensive site within the wider Firth, comprising a total area of 1,762.36 kilometres 2 (km) but excluding smaller subsidiary firths, many of which are also part of the existing SPA network (Figure 3). The Moray Firth SPA supports non-breeding populations of European importance of 11 species: great northern diver (Gavia immer), red-throated diver (Gavia stellata), Slavonian grebe (Podiceps auritus), greater scaup (Aythya marila), common eider (Somateria mollissima), long-tailed duck (Clangula hyemalis), common scoter (Melanitta nigra), velvet scoter (Melanitta fusca), common goldeneye (Bucephala clangula), red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator), and European shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis). Details of populations of these qualifying features in the Moray Firth SPA are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Moray Firth SPA qualifying features and populations

Population estimates are based on the mean maximum population estimates provided in Lawson et al., 2015 for all non-breeding (nb) waterfowl and Kober et al., 2010, 2012 for breeding (b) and non-breeding European shag. Percentage of GB population uses reference populations from Musgrove et al., 2013 and Wetlands International, 2014.

|

Qualifying feature |

Population estimate (individuals) |

% of GB population |

|---|---|---|

|

Great northern diver (nb) Gavia immer |

144 |

5.8 |

|

Red-throated diver (nb) Gavia Stellata |

324 |

1.9 |

|

Slavonian grebe (nb) Podiceps auritus |

43 |

3.9 |

|

Common eider (nb) Somateria mollissima |

1733 |

2.9 |

|

Long-tailed duck (nb) Clangula hyemalis |

5001 |

45.5 |

|

Greater scaup (nb) Aythya marila |

930 |

17.9 |

|

Common scoter (nb)) Melanitta nigra |

5479 |

5.5 |

|

Velvet scoter (nb) Melanitta fusca |

1488 |

59.5 |

|

Common goldeneye (nb) Bucephala clangula |

907 |

4.5 |

|

Red-breasted merganser (nb) Mergus serrator |

151 |

1.8 |

|

European shag (b & nb) Phalacrocorax aristotelis |

5,494+ (b) |

10.2 |

The presence of high densities of IWW and wintering European shags in the Moray Firth is indicative of the importance and productivity of these waters during the winter months. Common eider and European shag are resident throughout the year, but long-tailed duck, great northern diver, common goldeneye, greater scaup and Slavonian grebe migrate long distances from more northerly breeding grounds. Wintering red-breasted merganser populations in Britain include both long-distance migrants and resident birds, which are typically short distance migrants, using coastal areas in winter.

The SPAs deliniated in blue are: East Caithness Cliffs SPA, Dornoch Firth and Loch Fleet SPA, Cromarty Firth SPA, Inner Moray Firth SPA, Moray and Nairn Coast SPA. Created by Scottish Government (Marine Scotland) 2016. Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100024655. Contains data from JNCC, SNH.

The Moray Firth supports a wide variety of both pelagic and demersal fish and is an important spawning ground for several species. Shellfish, such as Norway lobster Nephrops norvegicus, and bivalves including blue mussel Mytilus edulis (Hopkins, 1986; Harding-Hill, 1993) also form part of the diverse fauna, all of which provide important prey for marine birds using the site. Divers, mergansers and European shags feed on a wide variety of fish, which they catch by diving from the surface and pursuing underwater (Guse et al., 2009; McCluskie et al., 2012).

Slavonian grebes feed on small fish species but their diet also includes small amphipods and other crustaceans (Sonntag et al., 2009). Great northern divers (Figure 4) also feed opportunistically on crustaceans (Roycroft et al., 2007).

Common eiders, velvet scoters, common scoters, and long-tailed ducks feed almost exclusively on molluscs and small crustaceans, diving from the surface to find their prey on the seabed (Fox, 2013). Common goldeneye and greater scaup feed mainly on bivalves and amphipods in winter months. Diving activity varies among species but average foraging dive depths for most are shallower than 15 m (Jakubas, 2003; Robbins, 2017; Kirby et al., 1993).

The Moray Firth SPA was identified as an ideal site in which to investigate approaches to monitoring IWW, due to the size of the site, mix of qualifying features and crucially an abundance of existing IWW survey data. These data spanned multiple years and were gathered using a range of methodologies, providing an opportunity for comparative analyses in an important marine site.

Moray Firth data sets

The following data sets (depicted as green boxes in Figure 2) were used to underpin site selection of the Moray Firth SPA and were used to conduct comparative analyses to explore future methods of monitoring. Full descriptions of these data and their characteristics are provided in Scott et al. (2022).

BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) data

The Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) is a long-term monitoring scheme of non-breeding waterbirds, including waterfowl and waders, coordinated by the BTO. Data is collected on a monthly basis throughout the UK by volunteers. The ‘core count’ (September – March) dates are pre-selected to enable a synchronised count across the whole country, in order to reduce double counting. The dates are selected with prioritization of tidal conditions for coastal surveys at high tide and generally take place on a Sunday. Surveys are undertaken at all wetland habitats used by waterbirds including lakes, reservoirs, canals, freshwater marshes as well as estuaries and sections of the open coast. Data collection began in 1947 and is ongoing which makes the WeBS data set enormously important in monitoring IWW and other waterbirds.

The WeBS core counts use a ‘look-see’ methodology, where the observer records all species within a given count sector. For shore-based count sectors this methodology therefore includes both waders on the shore and all marine birds (including waterfowl and seabirds). To participate in this survey observers must be familiar with all the target species of the survey, which include; swans, geese, ducks, divers, grebes, cormorants, herons, spoonbill, rails, cranes, waders and kingfisher, as well as optional counts of gulls and terns (WeBS Methods).

This methodology has some inherent limitations for counting IWW. The fixed count dates can result in weather and sea conditions which are not optimal for surveying these species. Furthermore, sustained observations are required to detect, identify and count IWW. The WeBS target species includes a large assemblage of birds which are found on the shoreline and other wetland habitats and therefore observer effort is divided, potentially resulting in undercounting for more offshore species.

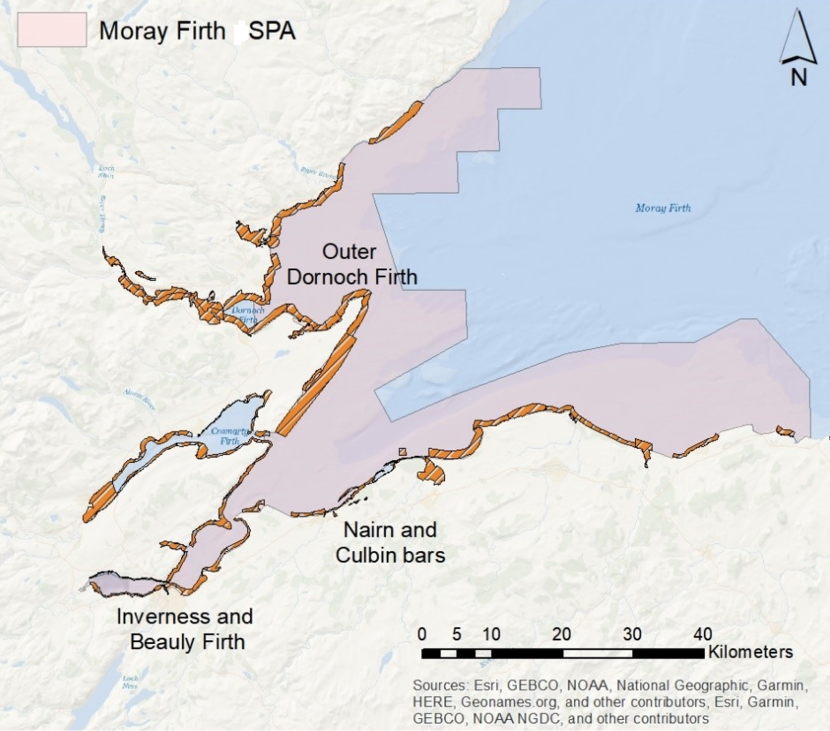

In the Moray Firth, WeBS counts cover an area from Brora to Buckie. The coastal regions are divided into 60 sectors, of which 55 fall within the Moray Firth SPA (Figure 5). For the purposes of this research, WeBS data was drawn from 1998/99 to 2018/19 for the qualifying features of the Moray Firth SPA (see Acknowledgements). This period was chosen to coincide with the commencement of data collection for site selection of marine SPAs for inshore wintering waterfowl in Scotland. In winter 2019/20, WeBS core count dates in the Moray Firth included the 12th of January and 8th of March. Data from the January 2020 counts were included in the following analyses but data from the March 2020 counts were not available when these analyses were undertaken.

RSPB Moray Firth Wintering Seaduck Counts

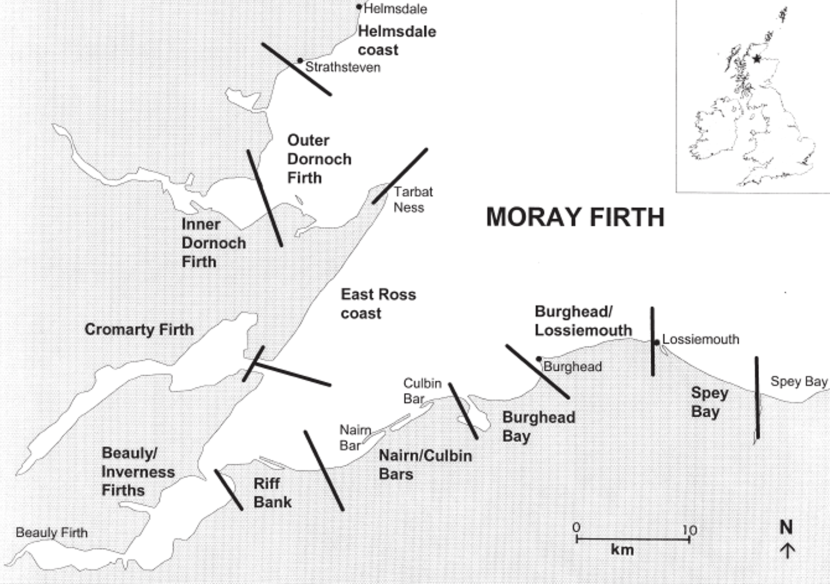

Following the development of the Beatrice oil field in the Moray Firth, the RSPB set up annual monitoring of wintering waterfowl (Evans, 1998). In 1977/78 surveys were undertaken by The Nature Conservancy Council and the RSPB. These surveys established baseline post-construction information on the Moray Firth populations and distributions of wintering divers, seaducks and grebes. Surveys were continued and expanded by the RSPB through most winters until 1994/95. After a two year gap in monitoring between 1995 and 1997 surveys were resumed in the winter of 1997/98 up until 2005/06 (Kaletja-Summers and Butterfield, 2006). The surveys provided good coverage of the Moray Firth coastline, establishing 112 vantage points from Helmsdale to Spey Bay, including the inner firths (Dornoch Firth, Loch Fleet, Cromarty Firth and the Inner Beauly Firth) (Figure 5).

The RSPB employed a dedicated observer in each survey season who surveyed the vantage points across the Moray Firth each winter using a look-see methodology. This survey was targeted at marine species, including; seaducks, divers, grebes, sawbills and auks. As a result of using a single observer these surveys were not synchronised across the site, however efforts were made to complete counts of each sector within a day (Kaletja-Summers and Butterfield, 2006). Consequently, whole site surveys could take around two to three weeks to complete. Data from these surveys were generally used preferentially to WeBS counts, and in some instances in preference to visual aerial surveys, in the assessments of IWW populations that were used to underpin site selection (see Table 7), as they focussed specifically on the relevant species. These surveys provided the best available data for greater scaup, long-tailed duck, common scoter, velvet scoter, common goldeneye and red-breasted merganser (Lawson, et al., 2015).

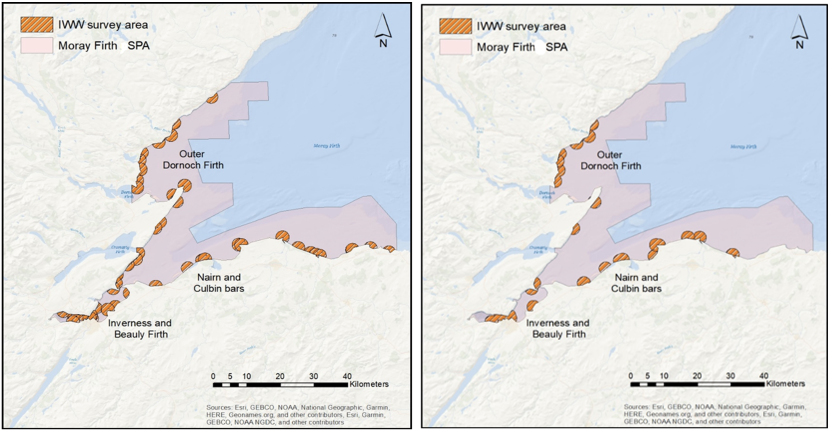

A map of the Moray Firth showing the boundary of the Moray Firth SPA and WeBS count sectors on the coastline in the Outer Dornoch Firth, the Inverness and Beauly Firths and at Nairn and Culbin Bars.

Sources: Esri, GEBCO, NOAA, National Geographic, Garmin, HERE, Geonames.org and other contributors.

Map of the Moray Firth showing 11 RSPB count sectors delineated by black bands. Sectors are; Helmsdale coast, Outer Dornoch Firth, Inner Dornoch Firth, East Ross Coast, Cromarty Firth, Beauly/Inverness Firths, Riff Bank, Nairn/Culbin Bars, Burghead Bay, Burghead/Lossiemouth and Spey Bay. RSPB (Kalejta-Summers and Butterfield, 2006)

JNCC Visual Aerial Surveys

Visual aerial surveys were undertaken by JNCC between 2000 and 2007 for species of seaduck, divers, grebes and little gull in the Moray Firth. Nine surveys were conducted using line transects, assigning observations to three, and later, four distance bands. Two observers, made observations from each side of the plane, by recording data onto a cassette voice recorder. Aircraft used a cruising altitude of 76 m and 185km h-1 in order to enable observations whilst minimising disturbance to target species (Lewis et al., 2008).

These visual aerial surveys were used for the population estimates of red-throated diver, great northern diver and common eider in the data underpinning site selection of the Moray Firth SPA.

The role of citizen science

Citizen science has a long tradition in the data collection and monitoring of the natural environment, particularly within ornithology, with volunteer collected data underpinning much of our understanding about the populations and distributions of bird species.

Despite the surge in community based monitoring methods over the last few decades, concerns about the data quality and credibility remain (Crall, et al., 2011, Law et al., 2017). Some studies have found greater variability in volunteer collected data than in data collected by professionals (Belt & Krausman, 2012 and Moyer-Horner et al., 2012.). Other studies have found that there is little variability in data between the two (Hoyer, et al., 2001, and Oldekop, et al., 2011). For example, Chandler, et al. (2017) found that there were many examples of volunteer collected data which were no more problematic than those collected by professional scientists. During identification tests of invasive species, Crall, et al. (2011) found that self-identified comfort levels provided the most accurate predictor of correct species identification. Variability and bias in citizen science data is still poorly understood, and it is possible that any associated error or variability is dependent on the type of monitoring undertaken, the conditions, target species and characteristics of volunteers. As such, it is appropriate to undertake field tests to investigate the levels of error present in each citizen science project to allow adjustments to be made to methodologies and protocols in order to reduce this as far as possible and so increase levels of accuracy and precision.

IWW represent a challenging taxonomic group for monitoring by citizen scientists due to their distance from the shore, and similarity of appearance for some related species (e.g. scoter species, diver species and shags and cormorants). Consequently, detection and identification can be difficult leading to errors in counts and resulting population estimates. On top of this, there are environmental challenges in coastal environments, which must be taken into consideration.

Despite the challenges inherent in citizen science methods and in monitoring IWW there are significant benefits to this approach, for instance, enabling snapshot data collection from multiple coastal vantage points across multiple sites, and which can be continued over long temporal scales. These data sets can make huge contributions to our understanding of species population and distribution and enable monitoring of specific sites at relatively low cost. However, the benefits of a citizen science based monitoring program move beyond data collection. Citizen science can also be a valuable means of increasing stewardship and awareness of our natural environment and influencing conservation actions and advocacy. In a secondary sense, citizen science projects can help to develop communities, increase the knowledge and skills of participants and help connect people to the environment (MacPhail and Colla, 2020).

Citizen Science Pilot

A bespoke citizen science survey methodology was developed and trialled at the Moray Firth SPA in winter 2019/20 and the results evaluated to determine the potential value of such an approach to future monitoring of IWW in MPAs. The Citizen Science Pilot was intended to explore three distinct topic areas:

Topic A: Factors which influence the quality and repeatability of shore-based counts of IWW in MPAs.

We aimed to explore species-specific, environmental, and observer (including equipment) factors affecting quality and repeatability of shore-based counts of IWW and consider how these might be controlled for through survey design and data collection protocols.

Topic B: Potential (added) value of targeted shore-based counts of IWW to detection of long-term trends and shorter-term variations in the populations and / or distributions of IWW qualifying features in large MPAs.

We aimed to examine the potential of targeted shore-based counts of IWW to provide a consistent proxy indicator of overall populations of some or all species in large marine sites. A specific focus was on whether targeted shore-based counts have potential to add significant value to the information on the abundance and distribution of any IWW species as already collected by WeBS counts.

Topic C: Practicality of a bespoke citizen science model for monitoring of IWW within MPAs and approaches to development and delivery.

We aimed to explore whether there is likely to be sufficient volunteer support for this type of monitoring in both the short and long term and considered how a bespoke programme of citizen science shore-based monitoring of IWW in MPAs be co-ordinated and delivered in the future.

Annex 1 sets out a series of detailed questions and approaches that were identified within these topic areas and outlines the progress made on each.

Methods

The Citizen Science Pilot surveys and digital aerial surveys were undertaken in the Moray Firth SPA in the winter of 2019/2020. Surveys were closely coordinated in order to facilitate comparison of the results. Two rounds of surveying were completed using each technique. Survey rounds were planned to run in January and February, however, very poor weather conditions resulted in the delay of the second round which eventually took place in early March (Table 2). Both survey techniques collected data on the 11 qualifying features listed in Table 1. Some other marine birds were also recorded, such as auks and gulls.

Table 2. Survey rounds and dates Moray Firth 2019/20

Weather data are from historic weather logs for Moray Firth at timeanddate.com.

|

Count round |

Planned Survey Date |

Actual Survey date |

Wind speed and direction |

Precipitation |

Cloud cover |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

18th / 19th January |

19th January |

16-27mph, SSW |

None |

Passing clouds (over 750m) |

|

2 |

15th / 16th February |

8th March |

11-16mph, SW |

Occasional light showers |

Passing clouds (over 750m) |

The weather requirements for the digital aerial survey and Citizen Science Pilot were slightly different, but both required low wind speeds, and good visibility. The digital aerial surveys required a cloud base of above 550m and the Citizen Science Pilot surveys required a sea state of four or less. In a large site like the Moray Firth SPA, conditions can vary significantly from one vantage point to another. During the first survey, this was the case, and many of the southern vantage points experienced higher wind speeds than the northern vantage points.

Citizen Science Pilot Survey Design

The NatureScot Citizen Science Pilot surveys were designed to target the qualifying features of the Moray Firth SPA from shore-based vantage points along the coastline. The survey was designed using a look-see methodology, at vantage points with a viewshed out to sea (Bibby et al., 2000 and Gilbert et al., 1998).

Recruitment for volunteer observers was undertaken by advertising with local bird groups and in NatureScot offices and using social media groups to find potential volunteers. Due to the challenges of monitoring IWW, we recruited volunteers who could already identify these species and around half of surveyed volunteers had previously participated in WeBS counts. The number of volunteers recruited dictated and constrained the number of vantage points surveyed on each count date with some volunteers conducting surveys from more than one vantage point. Volunteer observers were self-selected with the requirement that they must know how to identify the SPA qualifying features and have access to a telescope with which to conduct the surveys. All volunteers were provided with a copy of the survey protocol, information on the vantage points they were to survey and recording sheets. All volunteers were local to the Moray Firth area.

Count sectors and vantage points

The count sectors and vantage points used were derived from those previously used for the RSPB Moray Firth wintering seaduck counts. When developing the NatureScot Citizen Science Pilot, it was agreed that the original RSPB vantage points should be used where possible to aid comparisons of the data, and eliminate the need to select and quality assess many new vantage points. Some additions to the RSPB vantage points were required in order to include sections of coast which were not previously surveyed but which are within the Moray Firth SPA boundary. These additions were made prior to the surveys and were chosen based on appropriate distances between other vantage points and the likelihood of the site having a good viewshed. Similarly, some of the RSPB vantage points within the inner firths were excluded from the NatureScot survey design as they were not within the SPA boundary.

The Citizen Science Pilot consequently identified 84 potential vantage points within 11 count sectors (Figure 7 and Annex 2), substantially modelled on the sectors previously used by RSPB (Figure 6). The RSPB sectors were used to delineate sections of the Moray Firth coast and nearshore waters with distinct biological characteristics (e.g. more sheltered areas such as Inner Firth, areas of low water depth, such as the Riff Bank, and rocky shoreline such as between Burghead and Lossiemouth). The Citizen Science Pilot added a new sector to the east of Spey Bay (“Buckie to Portsoy”). In addition, the previous “Helmsdale Coast” was extended northwards to the Moray Firth SPA boundary and divided to create two sectors “Brora” and “Badbea to Lothbeg”. The RSPB “Cromarty Firth” sector, and associated vantage points, was omitted as it falls outside the Moray Firth SPA boundary.

Sampling methods and sector coverage

Although a whole site survey was desirable, it was not possible to survey every available vantage point due to the number of volunteer observers available at short notice to coordinate with the digital aerial survey. Consequently, only a selection of vantage points could be visited during each of the two survey rounds. Ensuring that the spatial sampling of the Citizen Science Pilot provided data which could be used for comparison with digital aerial survey was a key priority in designing the spatial sampling methods. A spatial sampling strategy for the Citizen Science Pilot was completed under contract to NatureScot by Biomathematics and Statistics Scotland (BioSS) whose (unpublished) report informed the spatial sampling described below.

To ensure good geographical coverage along the shoreline of Moray Firth and to facilitate comparisons with the WeBS and historical RSPB’s Moray Firth Wintering Seaduck counts, the sampling design was spatially stratified by the 11 sectors shown in Figure 7.

Up to three vantage points in each sector (17 in total) were initially identified as ‘essential’ (Table 3 and Figure 7). These were chosen based on knowledge of the Moray Firth distributions and sites that had high densities of the SPA qualifying features in the RSPB data. The number of additional vantage points to survey per sector was then determined according to the number of available volunteers. The intention was that simple random sampling would then be used to identify further vantage points to sample with the assumption that each volunteer could visit two vantage points. In allocating additional ‘non-essential’ vantage points, proportional allocation was used to randomly assign these to available volunteers.

In practice, as illustrated in Figure 7 and detailed in Table 3, the number and geographical distribution of volunteers and access issues for some vantage points, meant that it was not possible to cover all those originally identified as “essential”. However, in January, 12 “essential” vantage points and nearly 60% of all possible vantage points were covered by a total of 27 volunteers. Allocation of volunteers within sectors was as far as possible proportional to the number of vantage points identified in that sector. Exceptions were Badbea to Lothbeg and Burghead Bay, where only one vantage point was visited, and Buckie to Portsoy, where all vantage points were visited. In March, when only 11 volunteers were available, it was decided to omit two sectors (Badbea to Lothbeg and Riff Bank) and concentrate effort in the remaining sectors to provide adequate coverage within as many sectors as possible. Within these sectors, it was also decided where possible to prioritise those vantage points with greatest direct overlap with the digital aerial survey flight lines to facilitate direct comparisons. In March, volunteers re-surveyed 25 of the vantage points that were surveyed in January, including 10 of the original “essential” vantage points and 11 overlapping digital aerial survey flight lines. In some instances, vantage points were surveyed by volunteers but data was not submitted, in these cases we have treated the vantage points as not surveyed.

Table 3. Vantage points sampling design.

|

Shore of Moray Firth |

Sector |

Number of potential vantage points |

“Essential” vantage points codes a |

Vantage points overlapping digital aerial survey flight lines a |

Total vantage points surveyed in January |

Total vantage points surveyed in March |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

North |

Badbea to Lothbeg |

6 |

1a [b] |

(Excluded from design in March) |

1 |

0 |

|

North |

Brora |

4 |

3 [a] |

3 [a] |

3 |

3 |

|

North |

Outer Dornoch Firth |

10 |

6 [a], 15 [a] |

(5), 7 [a], 19 [a] |

6 |

5 |

|

North |

Easter Ross Coast |

7 |

25 [a] |

22 [a], (24) |

4 |

3 |

|

Both |

Riff Bank |

10 |

34 [a], S1 [b], 39 [b] |

29, 33, 38 (Excluded from design in March) |

7 |

1 |

|

Both |

Inverness / Beauly Firth |

19 |

I/B5 [a], S7 [a] |

I/B2 [a], I/B7 [a], S2 [b], S3 [b] |

13 |

5 |

|

South |

Nairn and Culbin Bars |

6 |

(43) |

45 [a] |

3 |

4 |

|

South |

Burghead Bay |

5 |

50 [b] |

(48), 52 [b] |

1 |

2 |

|

South |

Burghead to Lossiemouth |

6 |

(56), 58 [a] |

57 [b], 58 [a] |

2 |

3 |

|

South |

Spey Bay |

7 |

(59), 62 [a] |

62 [a] |

5 |

2 |

|

South |

Buckie to Portsoy |

4 |

N3 [a] |

N4 [b] |

3 |

0 |

|

TOTAL |

– |

84 |

17 |

22 |

48 |

28 |

[a] indicates surveyed in both January and March; [b] indicates surveyed in either January or March; enclosed in brackets indicates not surveyed

Map showing the Moray Firth SPA and indicating vantage points and when they were surveyed. Pink line indicates Moray Firth SPA boundary. Red vantage points were counted in both the January and March surveys (n=25), Blue in January only (n=23) and Black in March only (n=3). Grey vantage points were not surveyed. Vantage points initially identified as “essential” (Table 3) are circled.

© Crown copyright and database rights [2021]. Ordnance Survey 100017908. © Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Office. © Scottish Executive. © General Register Office (Scotland). © Scottish Rights of Way Society. © Forest Enterprise. © Forestry Commission, SSNWI. © Highland Birchwoods. Some features on this map are based on data from the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology © NERC (CEH), Defra and Met Office. © Crown copyright. © The James Hutton Institute. Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright 2020. All rights reserved. Licence No. EK001-20140401. Not to be used for navigation.

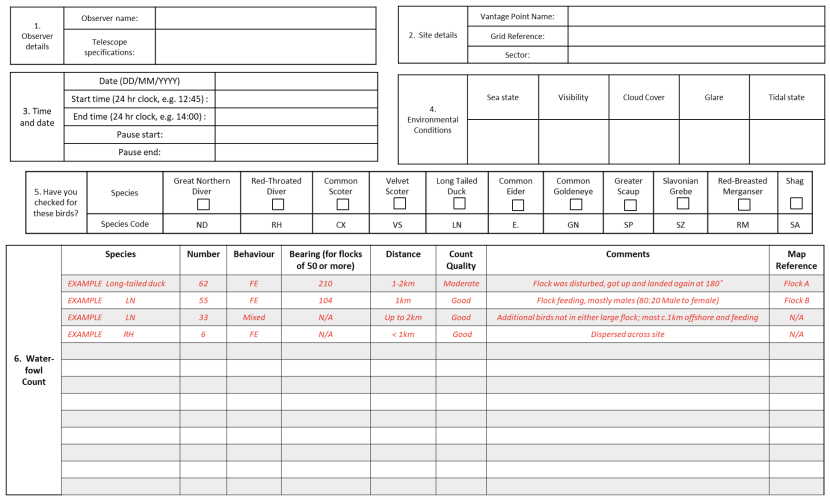

Recording methods and protocol

Volunteer observers were provided with a protocol to undertake the survey and a recording form on which to detail each survey (Annexes 3 and 4). Volunteer observers were asked to fill out recording sheets for each vantage point they visited.

Prior to beginning the survey observers were required to fill in sections of the form detailing their names, equipment used and the vantage point that they are surveying. We also asked that observers record the grid reference if the location of the vantage point was different from that provided. Observers were asked to make a judgement about the exact vantage point location on the day, as the project officer was not able to visit every vantage point in advance to assess viewshed and elevation. Volunteers were then asked to complete environmental information, including sea state (using Beaufort scale), visibility, cloud cover (measured in Oktas), glare and tidal state (details of the measurements used are provided in Annex 4). After completing this information volunteers were able to begin their survey, recording the date and time started. Once observers had finished the survey the finish time was also recorded in order to derive effort data.

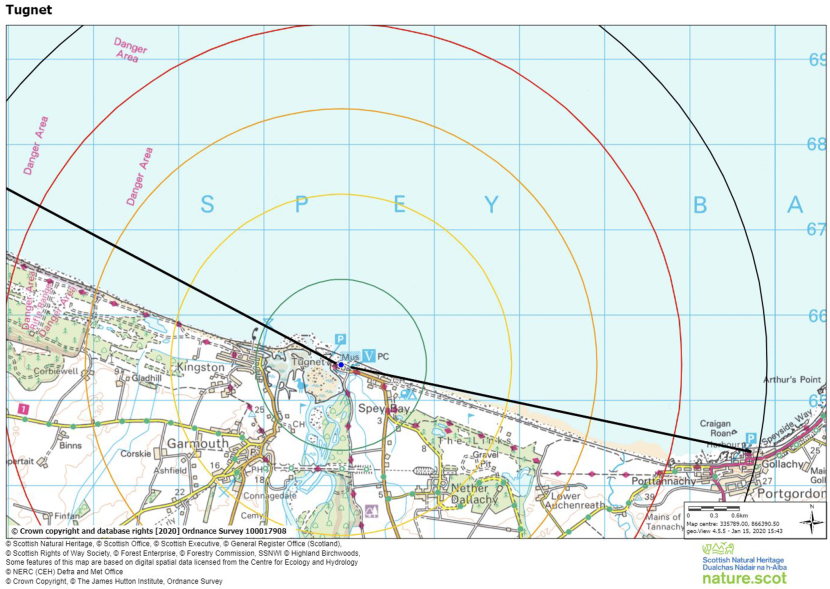

Observers were provided with a map of the vantage point and associated survey area (see example at Figure 8), which provided boundaries within which to complete their survey. Observers were encouraged to scan as methodically as possible using binoculars across the entire survey area (from left to right) to identify birds to be counted. Observers were then asked to use a telescope to identify and count all birds of the target species (Figure 9), and to scan further out to sea, where some species may not be found using binoculars only. Volunteers were permitted to count the birds in any way they chose e.g. using tally counters and techniques such as counting in 10s or 100s to estimate numbers in large flocks.

As the number of birds present differ with location and also time of day and tide height, observers were not restricted to a time limit for the survey, but were asked to stop surveying once they felt all the birds that were present during the first scan had been counted. This was to ensure that observers were not surveying the site for an extended period during which significant movement into or out of the survey area could occur.

Birds were identified to species level, where possible. However, if the species was unknown, observers were asked to indicate to lowest taxonomic rank possible, for example, ‘diver sp.’ or ‘scoter sp.’. Observers were asked to record all of the SPA qualifying features, scanning from left to right across the survey area. The protocol asked that no birds in flight were recorded unless they had taken off or landed in the survey area. Observers were asked to count flocks of over 50 individuals twice before recording the count or a third time where there was a large discrepancy between the first and second count. When recording the birds observed on the survey, the following information was recorded: species, number (count estimate), behaviour, bearing (for flocks of 50 or more) from vantage point, estimated distance from vantage point, count quality, comments and a map reference. Bearings to flocks and distance estimates were recorded in order to infer distribution within each vantage point survey area, and to restrict the data to within 2kms for analyses. We provided observers with maps in order to aid their estimation of distance to birds and to allow observers to show estimated locations of flocks.

Observers were asked to record their confidence in count quality (Good, Moderate or Poor) to gain more nuanced understanding of the quality of the data, and the certainty of the observers in their identification and counts.

We provided space on the recording form for comments, in case observers wished to note specific information about flocks which we did not anticipate (e.g. where they felt there may have been double counting, or notes on the identification of species).

Map of a VP with viewshed out to sea and distance bands in concentric circles out to a distance of 5 km.

© Crown copyright and database rights [2020].

Mapping and distance recording

All shore-based survey methodologies for marine birds are limited by distance to target species. Distance from the observer is a factor which greatly affects the detection and identification of species. The distance over which a bird may be detected and identified will also be affected by the bird’s size, plumage pattern and behaviour and by extrinsic factors including weather conditions, observer experience and optical equipment. However, under good conditions, observers are generally able to identify and count birds at up to 2km from the shore (Jackson and Whitfield, 2011; Waggitt et al., 2014; Oedekoven et al., 2013, Webb et al., 1990). Some birds may be visible at a greater distance, although counts and identification of such birds might be far less accurate and far more difficult to obtain.

A challenge in developing the survey protocol was how to verify which observations were in fact of birds within 2km, such that more distant birds could be excluded from relevant analyses. One option was to ask observers to only record birds within the 2km limit. However, it was felt that this might inhibit the collection of data with observers having to establish whether a bird was in or outside of the 2km boundary prior to counting it. This would add further opportunity for error and different rules being applied by different observers or even on different occasions by the same observer. Furthermore, important contextual information would have been lost at certain vantage points where large aggregations of the qualifying features such as scoter and long-tailed duck can be present beyond 2km.

We therefore asked volunteers to record approximate distances and bearings to flocks of over 50 birds. Volunteers were provided with maps (see example at Figure 8) which showed 1km distance bands up to 5km distance and detailed the distance to any landmarks at sea such as buoys, headlands or skerries.

In estimating distance to objects at sea, range finders, or distance sticks, are considered an effective means of obtaining a rough estimate. However, distance sticks must be made to fit the observer, taking into account their height and arm length and the elevation of the vantage point. Some training would be required to allow observers to use this type of equipment. This was not felt to be a realistic method for the Citizen Science Pilot due to tight project time constraints and the requirement for observers to make this to specification prior to visiting the vantage point. Instead we chose to use the mapping approach, which, while having limitations, was easy to provide to observers and simple to use.

Corrections for potential double counts

The potential for double counting large numbers of birds from adjacent vantage points was identified when reviewing the spatial sampling design. If a whole site survey were undertaken, double counting would be a significant concern as several of the vantage points had viewsheds which overlapped within the 2km boundary. However, a significant portion of the potential vantage points were not surveyed due to limited numbers of volunteers. Consequently, the majority of the vantage points which were surveyed in January and March were at sufficient separation to eliminate the possibility of double counting.

A small number of the vantage points with overlapping viewsheds remained and were surveyed. These vantage points therefore had the potential for double counting to occur. This risk was mitigated by having the same observer survey adjacent vantage points. Consequently, the observer had knowledge of the adjacent site and would be more likely to identify potential instances of double counting the same bird or birds. Furthermore, volunteers were asked to mark large flocks on maps and to record distances and bearings to these flocks such that obvious instances of double counting could be readily identified.

Some inherent problems still exist in particular for species which have smaller populations and are more locally sparse.

Data compilation and quality assessment

All data from both Citizen Science Pilot surveys, including counts from vantage points with no observations of the SPA qualifying features, were compiled into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (extract available in Annex 5) and each observation was assigned a unique ID code. The data were quality assessed during the input process and a few records that were not collected using the standard methodology were excluded to enable comparison with other vantage points. When inputting data into the database, the project officer standardised elements of the observations e.g. all distance estimates were converted into meters. This process raised queries around how to categorise entries that straddled two coded choices. For example one observer stated that the sea state was ‘1-2’. The decision was made to record the information as the observer recorded it, so that potentially incorrect interpretations were not coded into the raw data.

In general information on distance was retained as records for the majority of cases data was recorded clearly e.g. 2800m. However in some instances distance recording was not clear e.g. 'up to 3000m' or '<3000m'. In order to enable identification of data at less than 2km, some assumptions were made. Any records which stated numbers "up to 3000m" were assumed to be within 1km of the upper limit e.g. between 2001m and 3000m. Numbers recorded as e.g.<3000m were assumed to be between 2001m - 3000m and those recorded as e.g. >1000 were assumed to be between 1001m and 2000m. These assumptions allowed us to filter data based on those records that were less than 2000m

One potential double count was identified by a volunteer and this was highlighted in the database. However the database was not systematically checked for double counts.

Citizen Science Pilot field test

Field tests enable investigation of factors that might influence the quality and repeatability of the Citizen Science Pilot surveys. In particular, key questions were developed about how species-specific, environmental and observer factors affected count quality and whether these factors can be controlled for through survey design and data collection protocol (Annex 4).

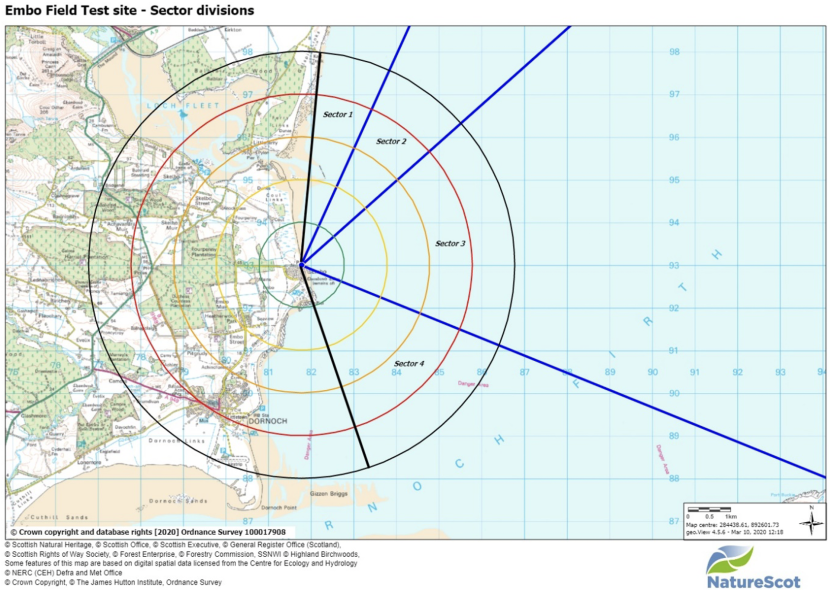

A field test was completed investigating inter-observer effects. Further field tests were planned seeking to investigate how environmental conditions might impact the quality of observations, but had to be cancelled due to the Covid-19 crisis. The field test was undertaken at Embo on the 3rd of March 2020, using six volunteers to assess how observers differ in count identification and estimation (Figure 10). All the observers were experienced ornithologists with knowledge of the SPA qualifying features and with some background in participating in organised counts. The volunteer observers were asked to answer some questions about their experience level.

Five of the participants were provided with the same telescope, a Swarovski ATS 65 with a 20-60x zoom lens. One participant used their own telescope (Nikon Fieldscope ED 82 with 30x wide angle eyepiece). The project officer, who organised the field test, was present to provide instructions, but did not participate in order to reduce the chance of any influence on the observers.

The field test was undertaken from a vantage point selected for the range and number of SPA qualifying features, as well as the presence of landmarks to aid observers in dividing the site. The viewshed of the field test vantage point was divided into four sections (Figure 11) in order to maximise the number of samples (6 observers x 4 sections = 24 samples). The sections were defined from the vantage point to certain distant landmarks. Sections were discussed and agreed with the volunteer observers before starting the field test.

Map showing Embo test site with lines denoting the end of each sector and 1 km distance bands.

© Crown copyright and database rights [2020]. Ordnance Survey 100017908. © Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Office. © Scottish Executive. © General Register Office (Scotland). © Scottish Rights of Way Society. © Forest Enterprise. © Forestry Commission, SSNWI. © Highland Birchwoods. Some features on this map are based on data from the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology © NERC (CEH), Defra and Met Office. © Crown copyright. © The James Hutton Institute. Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright 2020. All rights reserved. Licence No. EK001-20140401. Not to be used for navigation.

Observers conducted synchronised counts of each section, all beginning their survey at the same time and counting clockwise from the start of the section to the end. However, observers were allowed to complete each section in their own time before resynchronising at the beginning of the next section. This was to allow for differences in speed of recording and consequently to ensure that each observer completed the survey of each section. Volunteer observers were asked to follow the standard count protocol (Annex 4). No tally counters were used during the field test to minimise potential differences among observers in count methods.

Field test analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to investigate differences among observers. The raw counts were used to compare observers by both species and sectors recorded. We used a coefficient of variation to examine how inter-observer variability affects species counts.

Observers were ranked on their experience based on their answers to two questions:

- How would you describe yourself? (a. Occasional birder; b. Active birder; c. Committed birder; d. Expert birder)

- How many waterfowl surveys (or similar) have you taken part in previously? Could you please name the survey type(s).

This method was chosen as it was felt that only one metric might provide a biased ranking of experience. We used this observer experience metric to qualitatively investigate how experience might impact observer counts and potential underlying reasons for any variation.

Citizen Science Pilot volunteer feedback

To ascertain the practicality of the bespoke NatureScot citizen science model for monitoring IWW within MPAs, an online questionnaire was developed to invite feedback from volunteers about their experience of participating in the pilot study. The full questionnaire is detailed in Annex 6.

The questionnaire was designed to target volunteers’ thoughts on their experience of the Citizen Science Pilot surveys, whether they had taken part in other similar surveys and whether they would be interested in participating in this type of survey in future. In order to identify how a bespoke programme of citizen science shore-based monitoring of IWW in MPAs might be coordinated and delivered in future, further questions were included to ascertain any difficulties encountered in completing the protocol, and if volunteers were happy with the communication and planning of the surveys.

The questionnaire was created using Survey Monkey (an online questionnaire platform) and distributed by email to all volunteers. Volunteers were asked to self-complete the questionnaire and the results were automatically and anonymously collated by Survey Monkey. Further feedback was ascertained through informal conversations between the project officer and volunteers.

The volunteer feedback questionnaire was analysed using descriptive statistics. Qualitative thematic analysis was used to investigate responses to open questions by identifying common recurrent themes in participant responses.

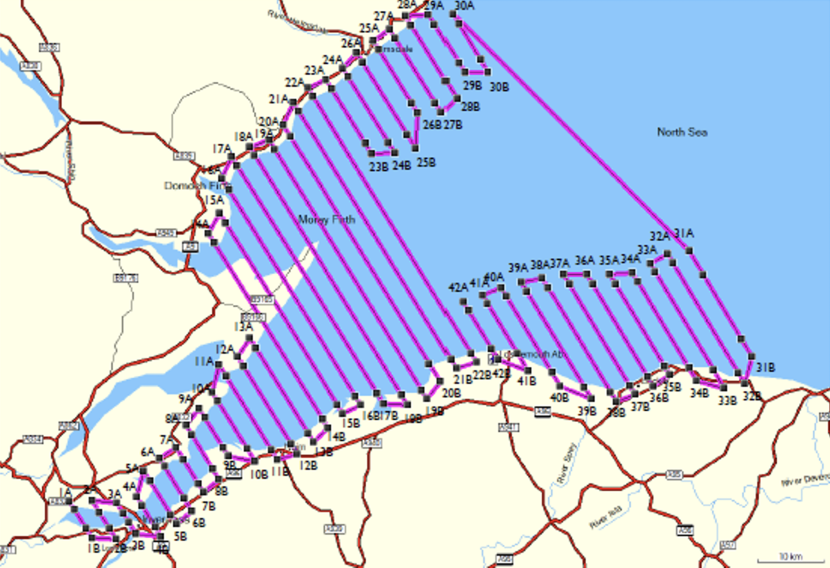

Digital aerial survey

The digital aerial survey design consisted of a series of parallel transects which were oriented approximately perpendicularly to the main gradients (bathymetry and proximity to coast) that were likely to affect bird distributions (Figure 12). This ensured that bird abundance was sampled across a wide range of these habitat values. A non-stratified approach was adopted with transects spaced at 3km distance apart. This spacing meant that with a 500 m survey swathe, approximately 16.7 % site coverage could be achieved (Table 4 and Figure 12), which was broadly similar to the effective coverage achieved in previous visual aerial surveys of the site described by Lawson et al. (2015).

The survey was split between two aircraft to ensure surveys could be completed in a day. Constraints imposed by the Ministry of Defence meant that flights had to take place at the weekend in order to achieve full coverage of the Moray Firth SPA. However, this fitted well with the availability of citizen science field workers for the concurrent vantage point watches. Weather considerations also limited surveys to days with no precipitation, cloud bases of at least 600m and wind speeds no higher than Beaufort force 6.

Table 4. Digital aerial survey effort across the Moray Firth SPA in 2019/20

|

Survey date |

Number of transects |

Total transect length surveyed (km) |

Area covered (km2) |

Percentage of SPA coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

19th January 2020 |

42 |

593.76 |

296.88 |

16.84% |

|

8th March 2020 |

42 |

597.76 |

298.88 |

16.96% |

The surveys were flown at approximately 220 km/hr at an altitude of ca. 550m (1800ft), providing a 2cm Ground Sample Distance (GSD) resolution. The resulting video footage was converted into a format for further analysis and images were manually reviewed by trained reviewers and then assessed and identified by a team of trained ornithologists. Further details are in Scott et al. (2022).

Map showing the Moray Firth SPA and the locations of the digital aerial survey transects.

Comparative analyses

The focus of this element of the project was on exploratory comparative analyses of data from contemporary and historic surveys of wintering waterbirds in the Moray Firth, namely:

- 2019/20 Digital Aerial surveys

- 2019/20 Citizen Science Pilot surveys

- Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS)

- RSPB Moray Firth Wintering Seaduck Counts surveys

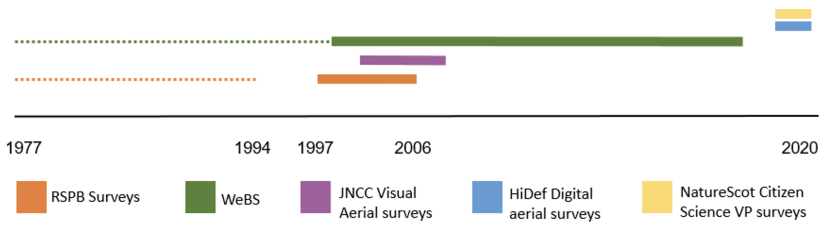

These data sets differed in survey methods and spatial and temporal coverage (Figure 13). The focus of the analyses reported here was on investigating the potential of the different types of survey data to provide robust and consistent indices of changes in bird populations within and across the Moray Firth SPA.

Timeline of surveys on inshore wintering waterfowl in the Moray Firth and years for which data was used in comparative analysis (Orange = RSPB surveys, Purple = JNCC Visual Aerial Surveys, Green = WeBS, Blue = Digital Aerial surveys and Yellow = Citizen Science Pilot surveys). Data was extracted for analysis for years with solid bars, dotted lines indicate additional availability of given data set from 1977 (when RSPB surveys commenced). Data were extracted from RSPB surveys conducted from 1998 until 2006, JNCC visual aerial surveys from 2000 until 2007and the WeBS from 1998 until 2019. Data from the HiDef digital aerial survey and NatureScot Citizen Science surveys cover the period 2019/2020.

As detailed in Scott et al. (2022), comparative analyses methods were developed by HiDef under contract to NatureScot and applied to three of the Moray Firth SPA qualifying features; common scoter, common eider and red-throated diver. These three species were selected on the basis of their differing habits and distributions. Red-throated divers forage on fish in the water column and are widely dispersed across the Moray Firth SPA. Common eiders feed predominantly on benthic bivalves, such as blue mussels, and are moderately dispersed, predominantly in nearshore waters. Common scoters occur in a few large aggregations and exhibit simultaneous diving behaviour to forage on bivalves in soft sediments.

Where there were sufficient data, the same analyses were then applied to the remaining qualifying features by the NatureScot project officer, with technical guidance from HiDef. Data processing and analyses were completed using the R programming language (version 3.4.3). The most recent version of the annotated R code used to carry out these analyses is available on Github.

Data processing

The data included in the comparative analyses were variously spatially and temporally defined and aggregated and were stored in a range of formats. Consequently, as summarised in Table 5, considerable initial data preparation and manipulation was undertaken by HiDef (Scott et al., 2022) to enable subsequent statistical analyses and interpretation.

Table 5. Summary of data processing and extraction for comparative analyses.

|

Data set |

Spatial data extracted |

Count rate data extracted |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Digital aerial survey (Jan & Mar 2020) |

Bayesian point pattern process used to predict bird densities across the SPA at a 1 x 1 km grid resolution. |

Not applicable |

Insufficient data to generate population estimates by this method for some species (Table 7) |

|

Citizen Science Pilot surveys (Jan & Mar 2020) |

Numbers of birds within 2km buffers around vantage points (Fig 13) |

Numbers of birds counted per hour |

Where spatial buffers overlapped, polygons were merged, and the average count taken. |

|

WeBS counts (1998/99 - 2019/20) |

Total numbers of birds counted within each count sector (Figure 5) for each monthly count |

Numbers of birds counted per hour in each count sector (Figure 5) for each monthly count |

For count rate, mean value of survey effort across all surveys used where not specified (69% of cases) |

|

RSPB vantage point surveys for Dec & Jan (1998 – 2006) |

No spatial analyses feasible. |

Mean count rates (birds/hr) in three broad sub-regions (The Outer Dornoch Firth, Nairn and Culbin Bars and Inverness and Beauly Firths; Figure 6) for each monthly count |

Some missing information on count locations. No information on the spatial effort. Limited data on count durations, survey effort in each sub-region inferred from approximate mean time for vantage point counts (c.0.4 hours). |

Count methods varied among data sets, and there were some gaps in the information captured with respect to on spatial coverage or survey effort. Consequently, some subsequent analyses were based on comparison of densities of birds within defined areas while others focused on comparative rates of observations. Where relevant, count rates were used to provide a measure of effort because raw count data cannot be used to reliably compare between methodologies (e.g. if in one method an observer counts 100 birds over two hours, but in another method the observer counts 10 birds over 15 minutes, the difference in counts reflects temporal effort).

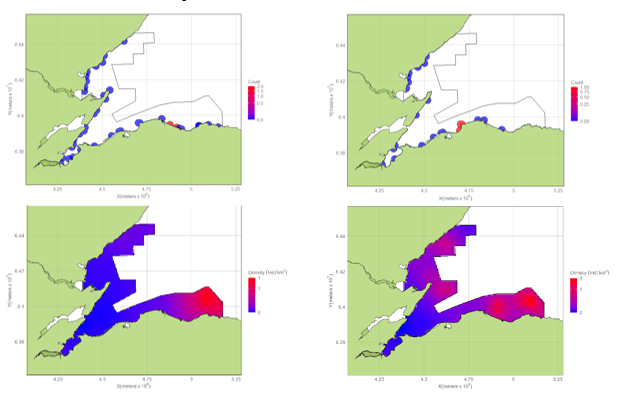

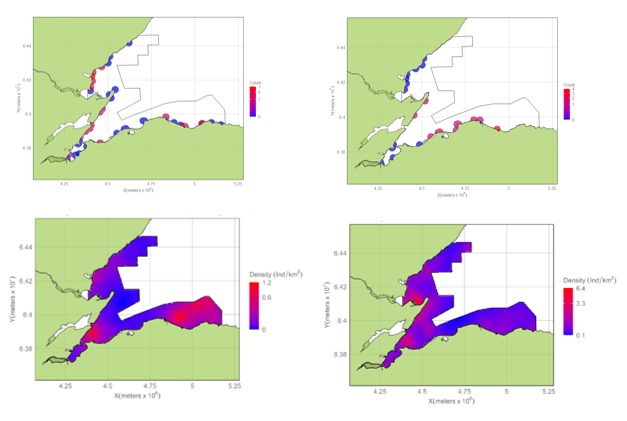

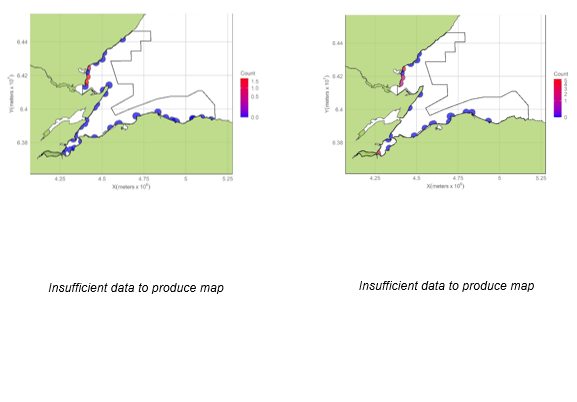

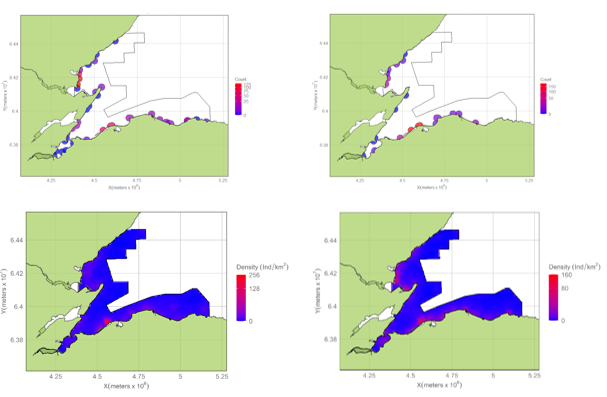

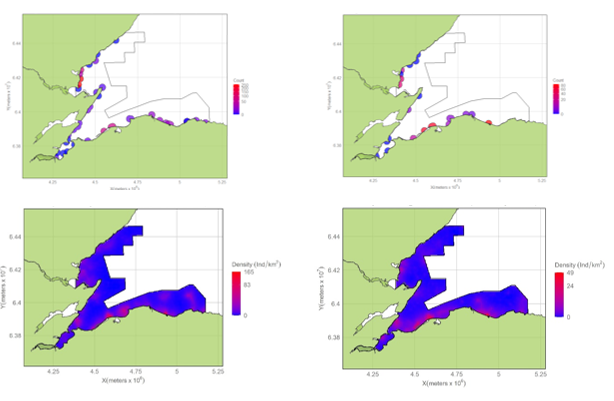

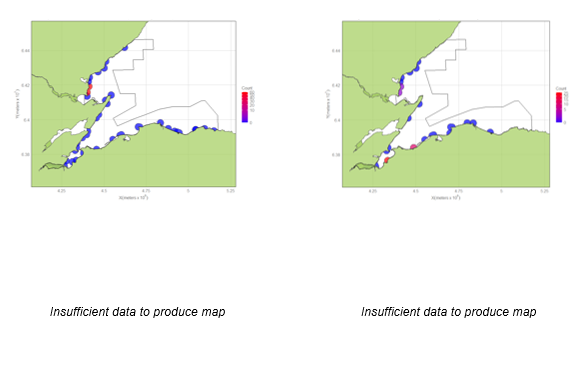

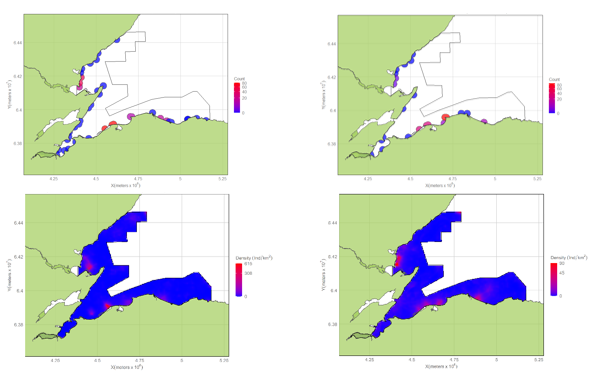

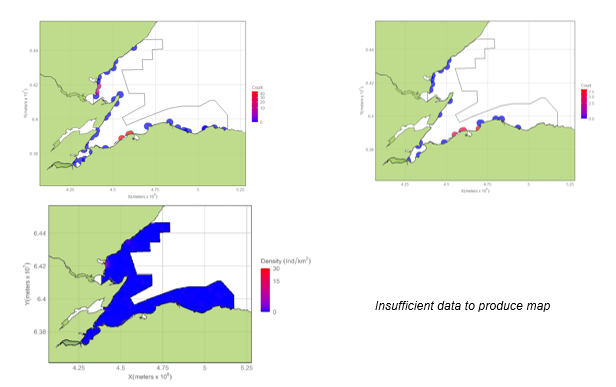

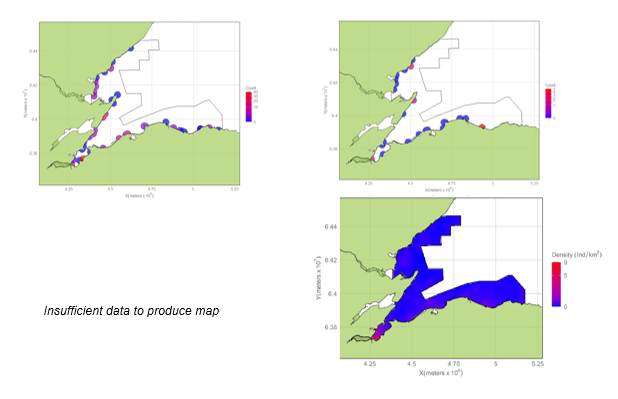

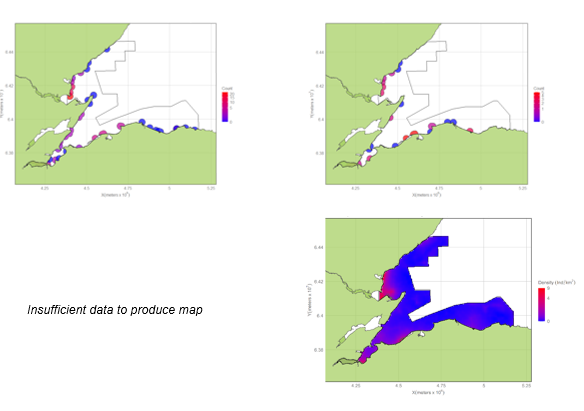

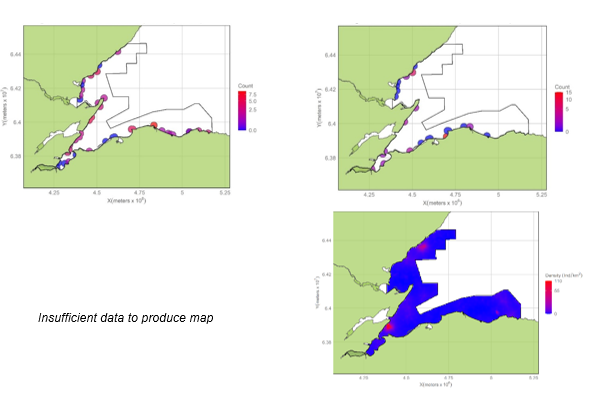

Comparing the digital aerial survey models to Citizen Science Pilot survey counts

To compare the Citizen Science Pilot vantage point counts to the HiDef digital aerial survey data, the mean density in the 2km vantage point buffers (Figure 14) was compared to the mean modelled density of birds from the aerial surveys within the same areas. These comparisons were made using linear regression and correlation. The data were also examined on a log-log scale in case there were issues of magnitude differences in counts or estimates.

For each species in the two survey months (January and March 2020), the linear relationship (either natural scale or log-log scale) with the highest Spearman’s correlation coefficient was selected (Scott et al., 2022).

Comparing Citizen Science Pilot survey counts to contemporary WeBS counts

A spatial merge was performed on the Citizen Science Pilot vantage point counts of 19th January 2020 and WeBS counts of 12th January 2020 using the R programming language. The WeBS data for March 2020 were not available at the time when these analyses were undertaken. All Citizen Science Pilot vantage points that fell within the boundaries of a WeBS sector were combined and a mean density was calculated. The mean density of the WeBS counts for each sector were also calculated using the area of the WeBS sector polygons (Figure 5). These densities were compared using a linear comparison and a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated.

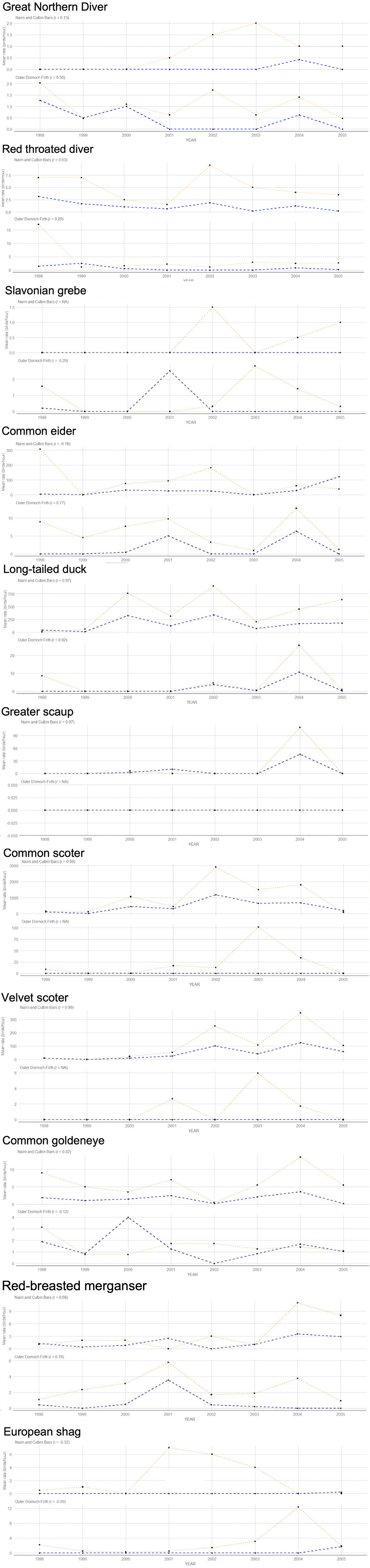

Comparing historic RSPB counts to WeBS counts

The initial explorative analyses of the RSPB vantage point surveys described in Scott et al. (2022) included three sub-regions in two months (Table 5). The extension of these analyses was restricted to the Outer Dornoch Firth and the Nairn and Culbin Bars sub-regions (Figure 6) as for a number of species there were zero or few data within the Inverness and Beauly Firths sub-region (see e.g. Figures 38, 39, 44 and 45 in Scott et al., 2022). By contrast, both the Outer Dornoch Firth and the Nairn and Culbin Bars sub-regions are well known for higher numbers of observations and were well covered by both RSPB and WeBS counts.

WeBS sectors (Figure 5) which fell into these two selected RSPB sub-regions were merged.

The mean count rates of birds (birds/hour) were then calculated for each species for these two sub-regions in December for each year, as counts were made in this month in all years.

The time series of rates of counts in the WeBS data and the RSPB data were then compared using a standard linear model to obtain the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Results

Citizen Science Pilot surveys

January surveys covered 48 vantage points, while in March 28 vantage points were surveyed, 25 of which were sites which had been previously surveyed in January (Figure 14). See Annexes 2 and 5 for details of surveyed vantage points and an extract of the original data.

Table 6 summarizes the counts for both the January and March surveys. Distance from shore strongly influences bird densities for most species, however it was not feasible to correct for reduced detectability because observers estimates of distance were not consistent or reliable enough to do so. Hence, the observations from each surveyed vantage point will underestimate actual numbers of birds within the field of view. Furthermore, the Citizen Science Pilot vantage points covered discrete sections of the Moray Firth SPA coastal waters and should not be considered to offer a whole site survey. Therefore, the counts detailed should be considered a minimum estimate of the birds present in the survey site during each round of survey.

Table 6. Total numbers of qualifying features observed from shore-based vantage points in the Moray Firth SPA in January and March 2020. Figures in brackets are numbers judged by observers to be within 2km of the vantage point. Note that the overall coverage and vantage points differed between the two surveys (Figure 14 and text).

|

Species |

19th January 2020 |

8th March 2020 |

|---|---|---|

|

Great northern diver |

4 (4) |

2 (2) |

|

Red-throated diver |

28 (23) |

14 (14) |

|

Unidentified diver spp. |

4 (4) |

1 (1) |

|

Slavonian grebe |

8 (8) |

39 (22) |

|

Common eider |

1913 (1324) |

1745 (1739) |

|

Long-tailed duck |

2027 (1882) |

1326 (1226) |

|

Greater scaup |

60 (8) |

64 (63) |

|

Common scoter |

1412 (1395) |

552 (552) |

|

Velvet scoter |

58 (58) |

42 (42) |

|

Unidentified scoter spp. |

4712 (4710) |

6880 (380) |

|

Common goldeneye |

191 (187) |

13 (13) |

|

Red-breasted merganser |

152 (100) |

39 (36) |

|

Unidentified duck spp. |

100 (93) |

287 (287) |

|

European shag |

137 (116) |

68 (68) |

|

Total |

10806 (9964) |

11072 (4445) |

Table 7 summarizes the data from the 2020 digital aerial surveys and Citizen Science Pilot surveys as well as historic WeBS, RSPB, visual aerial survey and European Seabirds at Sea (ESAS) data underpinning identification and classification of the Moray Firth SPA. The data in this table do not provide a like for like comparison due to the differing areas surveyed, and methods used.

Maps of the Moray Firth SPA showing the locations of the two 2020 pilot citizen science surveys. More locations were surveyed in January than in March.

Sources: Esri, GEBCO, NOAA, National Geographic, Garmin, HERE, Geonames.org, and other contributors, Esri, Garmin, GEBCO, NOAA NGDC, and other contributors.

Table 7. Target species: total Citizen Science Pilot survey counts and digital aerial survey modelled population estimates in 2020 with comparison to data from previous surveys underpinning site selection (Lawson et al., 2015). Figures marked with [a] are the Moray Firth SPA citation population estimates (see Table 1). The coverage of the site varied between survey types and so the figures are not directly comparable between survey types and periods. Note in particular: a) under visual aerial surveys, the figures in parenthesis refer to the original Area of Search (Lawson et al, 2015), whereas those used in the SPA citation (marked by [a]) are corrected to the (smaller) final SPA boundary; and, b) the January 2020 WeBS count data were incomplete when supplied. The population estimates from the 2020 digital aerial surveys are derived using Bayesian models, with 95% Confidence Intervals shown in parenthesis (see Scott et al., 2022 for full details).

|

Survey and years |

Great Northern Diver |

Red-throated diver |

Slavonian grebe |

Common eider |

Long-tailed duck |

Greater scaup |

Common scoter |

Velvet scoter |

Common goldeneye |

Red-breasted merganser |

European shag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Citizen Science Pilot Jan 2020 |

4 |

28 |

8 |

1913 |

2027 |

60 |

1412 |

58 |

191 |

152 |

137 |

|

Citizen Science Pilot Mar 2020 |

2 |

14 |

39 |

1745 |

1326 |

64 |

552 |

42 |

13 |

39 |

68 |

|

Digital aerial survey Jan 2020 |

180 |

254 |

Only 5 detected- no model |

3808 |

1624 |

Only 1 detected- no model |

9989 |

49 |

49

|

Only 8 detected- no model |

None detected |

|

Digital aerial survey Mar 2020 |

750 |

918 |

Only 4 detected- no model |

3355 |

4530 |

None detected |

2091 |

Only 2 detected- no model |

93

|

355 |

1762 |

|

WeBS Jan 2020 |

- |

13 |

4 |

1136 |

3001 |

114 |

1399 |

46 |

160 |

144 |

51 |

|

WeBS Mean of Peak 2006/07 – 2010/11 |

2 |

28 |

26 |

970 |

3,118 |

492 |

1,442 |

206 |

169 |

91 |

105 |

|

RSPB Mean of Peak 2001/02 – 2005/06 |

59 |

119 |

43 [a] |

1,435 |

5,001 [a] |

930 [a] |

5,479 [a] |

1,488 [a] |

907 [a] |

151 [a] |

- |

|

Visual Aerial Mean of Peak 2001/02; 2003/04 – 2006/07 |

144 [a] |

324 [a] |

0

|

1,733 [a] |

(3,167) |

0 |

(2,544) |

(249) |

(74) |

(90) |

- |

|

ESAS hotspot analyses of 1980 – 2006 data |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6,462 [a] |

Comparison with additional seaduck counts in the Outer Dornoch Firth

In the Outer Dornoch Firth, shore-based counts and distribution mapping of seaduck were undertaken by voluntary research from 2018-2020 (Patterson, 2019 & 2021). The methodology followed was similar to the Citizen Science Pilot methodology but prioritized counting large flocks of seaducks, divers and grebes over other species such as shag. Counts were undertaken regularly (weekly and opportunistically), from vantage points at Dornoch Golf Club, Golspie and Littleferry. Counts were scheduled to coincide with good weather conditions in which to survey.

These counts recorded 5,040 common scoter on the 26th of January 2020. The Citizen Science Pilot survey recorded 4,676 unidentified scoter species from the same VPs on the 19th of January. Table 8 details the counts by both David Patterson and the Citizen Science Pilot in 2020 for common scoter/scoter spp. Despite the ‘snapshot’ nature of the Citizen Science Pilot counts, the comparison suggests that the estimate is representative when compared to data from similar methods employed more regularly. Previous peak estimates from the RSPB seaduck surveys estimated common scoter at around 5,000 individuals.

Table 8. Counts undertaken by David Patterson (DP) and by Citizen Science Pilot (CS) in January, and February and March 2020.

|

Source |

Date |

Common Scoter count |

Scoter spp. count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CS |

19th January |

4,676 |

– |

|

DP |

26th January |

– |

5,040 |

|

DP |

20th February |

7,050 |

– |

|

CS |

8th March |

– |

6,881 |

Field Test Results

During the field test, each sector was surveyed once by each of the six observers. All of the Moray Firth SPA qualifying features were recorded by at least one observer, with the exception of great northern diver. The results of the field test are illustrated below comparing the populations estimated by each observer across all four sectors (Figure 16) for each of the species. It is important to note that observers 1- 5 were all using the same scope (Swarovski HD 20x60) while observer 6 was using a Nikon Fieldscope ED 82 mm objective with 30x wide angle eyepiece.

Observations were highest in sector one, with 66% of total birds recorded observed in the first sector (Table 9). Sector three was the quietest section with only 117 total birds recorded from all observers.

Table 9. Embo field test observations per sector

|

Sector |

Observations |

Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

16603 |

66.8 |

|

2 |

5859 |

23.6 |

|

3 |

117 |

0.47 |

|

4 |

2240 |

9.02 |

Table 10 shows total counts across all four sectors for each species and observer and Table 11 shows mean counts with associated coefficients of variation across observers for each species. Observer counts varied more in sectors one and two than in sectors three and four, perhaps reflecting the much higher overall numbers of birds, particularly scoters and common eiders present and associated counting challenges.

Table 10. Overall counts for each species across all sectors by observer (Obs)

|

Species |

Obs. 1 |

Obs. 2 |

Obs. 3 |

Obs. 4 |

Obs. 5 |

Obs. 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Great northern diver |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Red-throated diver |

2 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Slavonian grebe |

2 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

9 |

3 |

|

Common eider |

33 |

422 |

541 |

50 |

0 |

118 |

|

Long-tailed duck |

307 |

379 |

715 |

503 |

643 |

106 |

|

Greater Scaup |

0 |

0 |