Landscape Character Assessment: Glasgow and Clyde Valley - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The PDF version of this document is at the foot of this webpage.

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten,

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of;

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot/

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in the “NatureScot Review 116 – Glasgow and Clyde Valley landscape character assessment”, 1999, Land Use Consultants in association with Glasgow University Archaeological Research Division.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

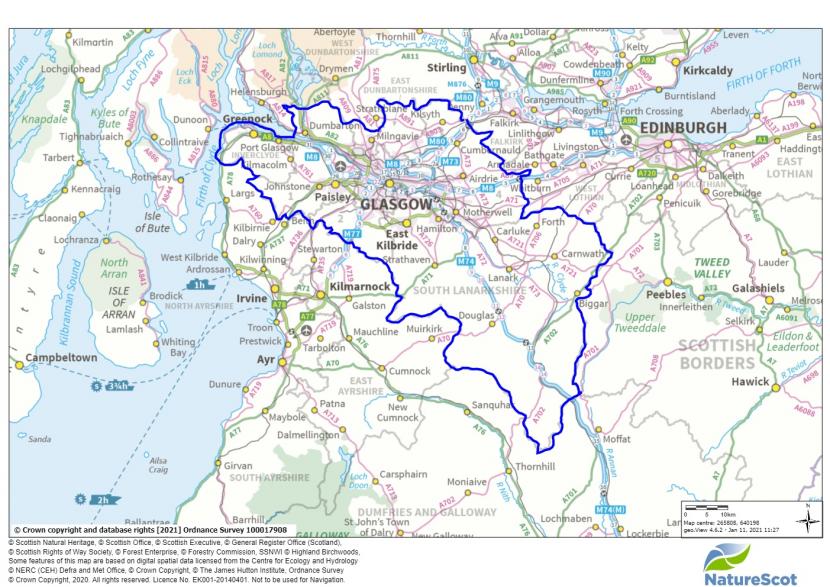

The Glasgow and Clyde Valley LCA covers the administrative areas of East Dunbartonshire, West Dunbartonshire, Glasgow City, Inverclyde, Renfrewshire, East Renfrewshire, North Lanarkshire and South Lanarkshire. It covers an area of 334,610 hectares, and extends from Gourock and the Firth of Clyde in the west to Carnwath and the Pentland Hills in the east, and from southern Loch Lomond and Balloch in the north to Abington and the Lowther Hills in the south. Geologically it mostly lies in the Midland Valley of Scotland, a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and Southern Upland Fault to the south.

This large area contains a very diverse range of environments, ranging from extensive urban areas to remote rural areas. The landscape seen today has been extensively influenced by human activity. At the core of the area is Glasgow city centre, with a variety of adjoining settlements and outlying rural settlements. The River Clyde lies at its heart – a focus along much of its length for settlement, transport and, downstream, industry. Other rivers are mostly tributaries of the Clyde and they are also varied in character, generally becoming more urban in their lower reaches, for example the Avon; the South Calder and the White Cart.

It is contained by plateau moorland uplands to the south; the Campsie Fells and Kilpatrick Hills to the north; the Firth of Clyde (which has some of the deepest inshore coastal waters in Britain at 164 metres deep) and intervening low moorland hills to the west; and the Slamannan Plateau and southern end of the Pentland Hills to the east. The lowlands in the central areas have mostly fertile soils.

One-third of Scotland’s population live in the area (1,789,500 in 2012, projected to grow to 1.84 million by 2029). This is creating a need for extensive new housing development on the periphery of urban areas, as well as a great deal of inner-city and riverside regeneration. The population has an increasingly ageing profile. The region generates a third of the country’s wealth and is home to over 29% of all businesses in Scotland. The traditional reliance on heavy industry, shipbuilding and mining has now changed to include modern engineering, manufacturing, and technology.

One of the city region’s key assets is the network of greenspaces that surround and intersect the urban area. It incorporates both green and blue spaces, such as parks, canals and woodlands, as well as the interconnected corridors which allow the movement of people and species between spaces.

According to the National Forest Inventory 2013, there are approximately 56,850 hectares of woodland within the region, of which approximately 14,691 hectares are native woodlands (derived from the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland 2014). This is around 17% of the area, which is close to the Scottish average of 18% of woodland cover.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

This section outlines the main physical processes which have determined the solid and drift geology of the Glasgow and Clyde Valley area, and the patterns of hydrology and topography of the area today. These attributes represent the physical structure of the landscape and are fundamental to its present character.

Solid Geology

Most of Glasgow and the Clyde Valley is within the Midland Valley of Scotland: a geological rift valley bounded by the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and Southern Upland Fault to the south. These faults run roughly parallel to each other, about 80 kilometres apart, from the south-west of Scotland to the north-east coast. The rift valley was formed by the unit of rocks between these faults being displaced downwards, creating a body of land of generally lower altitude than those bordering units to the north and south. Glasgow and the Clyde Valley occupies a large central portion of this rift valley: from the Firth of Clyde around Wemyss Bay in the west; inland as far as the western edge of the Pentland Hills: north to the Campsie Fells; and south over the Southern Upland Fault into the Southern Uplands.

Land to the north of the Highland Boundary Fault is comprised mainly of hard metamorphic rocks of the Dalradian supergroup. These formations do not outcrop in the area, but fragments of them occur in the glacial deposits which overlay much of the area. These are discussed below. South of the Southern Upland Fault, the rocks are Silurian and Ordovician sedimentary formations. These are generally fine-grained and form greywackes, shales and mudstones. These rocks have proved relatively resistant to weathering and have formed the rounded hills and plateaux of the Southern Uplands. Within the area, Silurian sedimentary rocks are found between Lesmahagow and Muirkirk.

The rocks of the Midland Valley itself are principally sedimentary and of the Old Red Sandstone (Devonian) and Carboniferous ages. The Devonian sandstone and conglomerate beds often have a distinct red-brown colour; they outcrop in the Lanark area. Late in the Devonian the conditions were desert-like, shown by sand dunes in the rock record. At the beginning of the Carboniferous period around 355 million years ago, the desert environment gave way to more tropical conditions. Additionally, there was major volcanic activity in the Glasgow area. Contemporaneous igneous rocks occur in the form of lavas and tuffs, and numerous intrusions such as plugs, dykes and sills also outcrop. The differential erosion of these harder igneous rocks and the softer sedimentary forms on which they lie has had a significant role in creating the present-day landforms and landscape.

There is a broad distinction between the main hill regions and plateaux areas which are formed from, or capped by, the extrusive volcanic rocks, and the lowland areas which tend to be sedimentary in origin. The Glennifer Braes, Beith-Barrhead Hills and Cathkin Braes are all formed from early Carboniferous basalt lavas. In particular, the lavas which cap the Kilpatrick Hills, Campsie Fells and Renfrewshire Hills created distinctive 'stepped' or terraced slopes. Igneous intrusions have created the features such as Dumbarton Rock (volcanic neck) and Tinto Hill (felsite laccolith). Similar landforms are found in neighbouring areas outwith the area.

The remainder of the area is comprised of Carboniferous limestones, grits and coal measures, generally forming the lower ground and basin areas. While these rocks also form the exposed central plateau between the east and west sides of the country around Shotts, Harthill and Caldercruix, the highest points of the plateau are still notably lower than the igneous hills elsewhere in the Midland Valley. The coal measures which underlie much of the basin have had a very significant Influence on the pattern of industrial development and settlement in the area. Some of their fossil content is of international importance, for example at Bearsden; and Fossil Grove in Victoria Park in Glasgow is renowned for the glimpse it provides of the Carboniferous forest environment. However, their contribution in terms of physical landform is relatively limited.

The shapes and forms into which the rocks of the area have been eroded and moulded reflect millions of years of weathering under a variety of climatic conditions. In particular, the actions of successive glaciations have carved the rock surfaces, deepening and over-deepening valleys and basins, and sculpting other rock features. Fluvial erosion had a continuing influence over the millions of years before the Ice Ages, and over thousands of years since the withdrawal of the last glaciers.

Glaciation

Glacial Erosion

During periods of glaciation there are thought to have been a number of ice sheets centred on different locations in Scotland. At their maximum extent, these would all have been connected to form a single sheet over most or all of Scotland, possibly joining the main Scandinavian ice sheets over the North Sea. One of the major centres of ice dispersal in Scotland was centred over the Rannoch Moor area, and it is ice originating from that area that had the greatest effect on the Glasgow and Clyde Valley LCA area.

Ice from the Rannoch sheet travelled south, down what is now Loch Lomond, along the Clyde Valley south and east towards the Southern Uplands and Edinburgh. A further branch flowed west towards the Firth of Clyde. The Southern Uplands themselves are thought to have held a similar, but smaller, ice sheet with glaciers of considerably less erosive power. This movement has been traced from the shapes and orientation of rock features which have been streamlined by ice over many glaciations. Also, deposits known to have been left by ice of the most recent period of glaciation to affect the whole area, (the Dimlington Stadial, around 26,000-13,000 years ago) indicate where ice travelled. The distribution of pieces of Glen Fyne granite for example, the source of which is located at the northern end of Loch Lomond, shows that ice transporting this rock must have extended far up the Clyde Valley.

A small readvance of the Scottish ice sheets occurred between 11,000 and 10,000 years ago; known as the Loch Lomond Stadial or readvance, it had a small effect on parts of the area. Small areas of land around Loch Lomond itself have been very slightly modified by glaciers from that time, and there has been speculation that some small glaciers may have formed on higher ground in the Southern Uplands.

The main ice-cut basins and valleys in the area are the Loch Lomond-Leven Valley, Strathblane, the Glasgow basin (or Howe of Glasgow) and the inner Clyde Valley for most of its length. These channels were present prior to the advance of the ice, probably formed by pre-glacial rivers over millions of years, but were deepened further by the glaciations. Much of the Glasgow basin, which now holds most of the conurbation, has been infilled with deposits from the Dimlington Stadial and later periods when sea levels were higher, flooding much of the Clyde Basin. Ice-streamlined landforms are common, such as crag-and-tail where resistant volcanic rocks protected weaker sediments from the eroding effects of glaciers. The Necropolis in Glasgow is an example.

Glacial Deposition

The materials eroded by glaciers were subsequently deposited by the glaciers or by meltwaters associated with the ice. These deposits can simply be a blanket-like covering of material plastered onto rock surfaces in varying thicknesses, or they can be specific and separate landforms related to the particular mode of deposition. Such deposits are extensive throughout Glasgow and the Clyde Valley and make a significant contribution to the present landscape.

The general area of the Glasgow basin has a thick layer of glacial deposits. These were moulded underneath the last glaciers to form streamlined hummocks known as drumlins. Drumlin fields extend south and east from Loch Lomond in the north, towards Ayrshire and the central plateau. Much of the conurbation is built over drumlins, and they have influenced the settlement pattern adopted there. These are reflected in place-names such as Maryhill, Hillhead and Drumchapel as well as the way street patterns curve around the steeper slopes, or buildings – such as Glasgow University – are placed prominently on top.

Glacial deposits also fill, and can obliterate, pre-glacial valleys. Parts of Motherwell overlie a buried valley around 50 metres deep and another extends from Kirk o'Shotts to Wishaw. Former courses of some tributaries of the Clyde, the Mouse and Avon waters, are also recorded by deep buried valleys.

Fluvio-Glacial Deposition

Meltwaters from the glaciers deposited large volumes of sand and gravel over parts of the Glasgow and Clyde Valley area. There are great accumulations of fluvio-glacial materials (which were deposited by meltwaters) in the upper Clyde Valley tributaries around Carstairs and in the Douglas Valley. The Carstairs Esker is a long, ridge-like form that was deposited by a river or stream running underneath the ice which once covered that area.

Other related landforms in the area are kames and kame terraces, formed from deposits left at the margins of the ice and land by meltwaters running off the ice. These features tend to form a chaotic hummocky terrain of lumps and hollows. The sands and gravels of these deposits are now a financially viable mineral resource and are extracted in some parts of the area.

Sea Level Change

In the aftermath of the last glaciation (the Dimlington Stadial), a rise in the relative sea level meant that sea waters extended up the Clyde and reached up to some 25 metres higher than at present. At that time much of the Glasgow area would have been under water, with tidal sea waters cutting shorelines into the drumlins of the Glasgow basin and into the fluvio-glacial deposits from the meltwaters of the receding glaciers. Cliff lines were also cut into the solid geology of the coasts of the Firth of Clyde. Subsequently, the sea level dropped relative to the land as a result of isostatic uplift. This left the former cliffs and beaches dry and raised above sea level. The raised beaches of the Firth of Clyde are now important topographic features utilised as communication and development corridors.

Fluvial Erosion

Postglacial rivers have cut channels through the soft deposits of the valley floors to create terraces. The postglacial drainage system of Glasgow and the Clyde Valley differs in some respects to that which existed prior to glaciation. While many postglacial rivers have followed old courses, they had to cut through new deposits and have only occasionally found the true rock valleys through which they formerly flowed. Where deposition by the ice and its meltwaters filled-in preglacial valleys, as is the case near Motherwell and in some of the Clyde tributaries such as the Mouse Water and Avon Water, the waters have been forced to find new courses through these sediments.

The Clyde has 'captured' a number of new tributaries since the last glaciation, taking away waters which once flowed east to the Tweed valley. It is thought that at some time prior to the last period of glaciation, the watershed of the Clyde and Tweed waters was situated close to the present location of Lanark. However, the Clyde had enough erosive power to cut backwards to collect firstly the Mouse Water, then the Douglas and the North Medwin Water, and finally the Upper Clyde itself near Symington. These tributaries have also extended their catchment areas to make the Clyde the size it is today.

A combination of the need to reinstate river valleys through deposits or rocks, and isostatic uplift of the land adjusting to its lighter weight without ice sheets, has meant that many rivers have cut narrow gorges. This feature is most pronounced in the upper Clyde area where the Clyde itself and several of its tributaries such as the Mouse and Avon Waters and the River Nethan at Crossford, all have gorges or narrow steep-sided sections to their courses.

Topographic Features

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley is predominantly a lowland area surrounded by hill ranges. Whilst the latter reach over 700 metres in South Lanarkshire, they generally lack the rugged grandeur of mountains north of the Highland Boundary Fault. Nevertheless, the hills that enclose the Clyde basin are important visual boundaries for a large population and their topographic variety is appreciated and physically experienced on a regular basis. The terraced lava cliffs and scarps of the Campsie Fells, Kilpatrick Hills and the Renfrewshire Heights are distinctive features to the north and west. To the south are the larger scale, but more uniform, domed forms of the Southern Uplands.

Volcanic activity has introduced topographic landmarks into comparatively lowland situations. Dumbarton Rock, Duncryne Hill, Dumbuck Hill and Tinto Hill are the most noticeable within the Glasgow and Clyde Valley LCA area, appearing as prominent conical hills. Many of these have been utilised for their prominence with the erection of Bronze Age cairns, such as at Tinto, or Iron Age hill forts and/or later castles, on their summits – Dumbarton being one of the most prominent examples. Similar features can also be found just outside the area at Dunglass, Dumgoyne and Loudoun Hill, the latter perhaps being most famous as acting as an evocative landmark for the location for one of the most important battle in the Wars of Independence.

Topographic features related to glacial and post-glacial activity are important in this predominantly lowland landscape. Drumlin hills determine the scale of spatial enclosure in many areas. They have also had a considerable influence on settlement and urban development patterns. In rural areas, many villages and farmsteads are sited on drumlins.

In Glasgow, the views afforded by drumlins were used to great effect in the layout of urban blocks and parklands. Other glacial deposition features include eskers and kames near Lanark and Carstairs. Glacial erosion also had a significant influence within the Southern Uplands in particular, carving the deep, rounded glens and smooth domed hills and summits.

Changes in sea level have created the raised beaches of the Clyde Estuary, extending as far inland as Erskine. These have provided important communication and development corridors beside the Clyde with an immediate hinterland of steep bluff slopes.

The major valleys of the Clyde, Kelvin and the Leven are, of course, essential topographic features of the area, with characteristics that vary throughout their length. There are also many smaller valleys with distinctive relief. The gorge sections of the Clyde near Lanark, the North Calder near Calderbank and the Avon near Hamilton are particularly distinctive examples.

Freshwater

The river Clyde, with its estuary and tributaries such as the Leven, Cart and Kelvin, is important in the landscape. River valleys frequently follow the north-east/south-west grain of the dominant faults. They influenced the location of much of the human settlement and transport infrastructure that followed. Walkway routes now follow several of the main river corridors, including the Clyde itself, and the Avon and Kelvin.

The Falls of Clyde, New Lanark are of geological, botanical, historical and cultural interest. They were harnessed for electricity in 1926, Britain’s first commercial hydroelectric generating station, but on ‘waterfall days’ they can be seen as they were viewed in the past by tourists.

Water bodies include man-made reservoirs as well as natural lochs, many the result of glacial processes, eg. kettlehole lochs such as the Seven Lochs, now a wetland park, which include Frankfield Loch and Hogganfield Loch on the northern boundary of North Lanarkshire. Many are still managed to support multiple usage including access and recreation. Strathclyde Loch is the prime example, visible from the M74 between Hamilton and Motherwell. Others were originally created to provide power to industry along the banks of the Clyde and other valleys. Thom’s Cutts, on the hills between Inverkip Greenock, is one of the most the extensive and well-preserved examples, along with that at the northwest end of Lochwinnoch.

The Forth & Clyde and Monkland Canals pass through the area. These once served as transport routes for business and industry and have now become a valuable recreational and natural heritage resource.

The Forth and Clyde Canal is a superlative example of Georgian civil engineering. It was the first of Scotland’s great inland waterways to be constructed and, even at the time of its opening in the 1790s, it was christened ‘The Great Canal,’ a recognition of its undoubted importance even then. The Monkland Canal is an excellent example of Georgian civil engineering. The earliest sections, constructed from 1770 onwards, are the work of celebrated engineer and inventor James Watt. As the main means of transport between the North Lanarkshire coalfields and the rapidly expanding city of Glasgow, the canal epitomises the interdependence of 18th Century Glasgow with North Lanarkshire, which led to the region becoming the most important industrial centre of 19th Century Scotland.

Climate

Like the rest of Scotland, Glasgow and the Clyde Valley experience a generally cool and wet climate. It is oceanic, that is, with little extreme variation or events but there is often considerable daily variation in the weather. The prevailing winds are south-westerly. Winter temperatures in the Glasgow area are similar or slightly cooler than the Scottish average; summer temperatures are warmer. Rainfall is distributed evenly throughout the year and there is significant annual rainfall – even the drier months tend to have a good deal of rainfall.

There is variety in the weather experienced across the area given the range of heights and varying proximity to the coast. There can be snow on the higher ground (despite its relatively low heights, generally less than 600 metres) while the lower ground is rainy (70% of the west Central Belt is below 200 metres in height). The Clyde downstream from Glasgow feels the evidence of the Gulf Stream and also shelter from coastal gales: tender plants can be found in gardens on the Firth. This provides a strong contrast to the exposure of the higher ground.

Soils

Most of the soil parent materials are of glacial influence, such as tills, fluvioglacial sands, silts and gravels. Alluvial and organic parent materials are also present. In the lowland areas, parent materials derived from Lower and Upper Old Red Sandstone can give rise to reddish brown sandy clay loam soils, or more gravelly textures. Carboniferous sediments can result in yellowish brown and greyish brown tills of clay loam or sandy clay loam.

Soils in the lowland areas are generally mineral soils. Frequently derived from fine-textured parent materials, they commonly have gley features with poor natural drainage. (Gleys are periodically or permanently waterlogged.) The most common major soil sub-groups are brown forest soils with gleying and noncalcareous gleys. Fluvioglacial sands and gravels occur locally in the broader valleys.

The major soil sub-groups in the upland and hill areas are mostly peaty gleys and peat. Soils are often shallow over the bedrock. Deep wet peat or peaty soils accumulate in depressions. Peat blankets large areas of gently sloping upland.

The best land (Land Capability Classes 3.1 and 3.2) is found on remaining alluvial floodplains in the heart of the basin. At Rosebank and Crossford in the heart of the Clyde Valley there are pockets of Class 2 land. Relatively small areas are found to the south-west and north of Glasgow, with a greater concentration forming a broad (if fragmented) band to the east of Glasgow. Further areas are found within the tight confines of the incised part of the Clyde Valley between Hamilton and Lanark, and within the broad alluvial basin near Biggar. Poorer farmland (Class 4) forms a band around the moorland hills and uplands, corresponding broadly to the areas defined as plateau farmland. On the south western side of Glasgow these areas extend up to the urban edge. The poorest land, Classes 5 and 6, is concentrated on the moorlands and plateau that enclose the Clyde Valley, principally the Renfrewshire Heights, Kilpatrick Hills, Campsie Fells, central plateau and the moorlands separating the valley from the Ayrshire Basin.

Landcover

Lowlands

Throughout the more accessible, low altitude areas, where not developed for urban uses, the land is mainly agricultural, mostly under pasture including silage grassland, but there are areas of arable land growing: in particular barley, wheat, oats and oil-seed rape. There is less arable land than the Scottish average in this region.

The pattern of agriculture closely reflects the physical structure of the landscape, as well as soils, climate and other factors. These patterns are reflected in the distribution of farming types and many of the farming units have characteristic field boundaries of stone dykes, hedgerows or field boundary trees, depending on their location. Arable production is concentrated within the Black Cart floodplain in Renfrewshire and along the southern side of the Kelvin Valley between Glasgow and Kirkintilloch. The Upper Clyde Valley, including the narrow valley between Hamilton and Lanark, has historically been dominated by orchards, horticulture and arable, including large areas of greenhouses for growing tomatoes. These industries were established on the sand and gravel terraces and alluvial soils of the valley, though recent decades have seen the decline of fruit and vegetable growing in the area. Remnants can still be seen in what is now more of a garden centre landscape.

Much of the remainder of the lowlands are dominated by pastoral farming, with cattle in the lower areas and cattle and sheep grazing on higher, less productive land. The uplands are dominated by extensive hill farming, though improved pastures are found along many of the valleys and glens.

The vast majority of the grasslands have been dramatically altered, and sometimes created by improvement treatments such as draining, fertilising and seeding, and areas of unimproved, or even semi-improved, pasture or traditional meadow grasslands are becoming an increasingly rare resource. Even though large areas of the urban fringe still retain a rural atmosphere, the ecological interest of this improved farmland landscape is in general fairly low.

Local areas of less-improved grassland, and other habitats such as heaths, mires, wetlands and woodlands occur scattered throughout the lowlands, usually on marginal farmland such as along the sides of water courses, poorly draining depressions or haughs, local rocky ridges, upland transition slopes, areas of abandoned industry, and on the urban fringes (several of these are noted further in other sections). These areas can be of high diversity and interest and many are noted as being local nature conservation sites (LNCS) within their respective local authority areas.

Uplands

The high ground typically supports three main habitats: species-poor upland pasture, heather moorland or forestry. These habitats can occur in complex mosaics but frequently they are represented in discrete units, reflecting the local estate management regimes. The combinations of these habitats over the seasons can impart characteristic ranges of colours and textures to the landscape with shades of greens, browns, ochres and straw, and at flowering periods, the vivid purple of the extensive heather dominated areas and the white heads of cotton grasses in blanket bog. These contrast with the predominantly agricultural landcover of the lower ground

The pasture grasslands, maintained by sheep grazing, with some dairy and beef cattle in Clydesdale, are dominated by fine-leaved fescue, mat and wavy-hair grasses and broader-leaved bent grasses, usually with a limited range of associate herbs and mosses. The acidic grasslands can occur in complex mosaics with dry and wet heaths, in part reflecting soils and drainage, but mostly the localised influence of stock grazing; such mosaics can be of high value to wildlife and species diversity and have visual landscape appeal. However, there has been a loss of unimproved and semi-improved grassland, with an average decline between the 1940’s and 1980’s of 14%, with the highest rates occurring between the 1970’s and 80’s in the northern part of the area.

The species diversity can be locally high, often associated with bent-fescue type grasslands on shallower soils or those with a more basic underlying geology such as in the Renfrewshire Hills can have locally high species diversity. Locally, bracken can form extensive stands, sometimes indicating former woodland areas, and generally impacting both the ecology and landscape.

Many of the field boundaries are defined by hedgerows, frequently devoid of trees, which establish rectilinear patterns in the landscape. Hawthorn is the commonly used species although beech is characteristic of certain areas where locally favoured, such as in the north of the area, adjoining the Trossachs. The hawthorn hedgerows are badly maintained in many parts of the area and are now seldom stock-proof. At many areas the defunct hedgerows have large gaps, some being seriously overcut or conversely are overgrown appearing more like rows of widely spaced shrubs. Some of the better-maintained hedgerows can occur along roadsides, where there can be well-developed hedge-bank grass and herb floras; such floras are now rare or absent in the heavily grazed pasture fields.

Trees and woodland

Woodlands are widely distributed and varied. The area has a very extensive softwood resource, concentrated on the moorland plateaux and hills around the edges of the city region, most notably in the Southern Uplands, Lowther Hills, on Eaglesham Moor, the Slamannan Plateau and in the Campsie Fells and Kilsyth Hills. These forests make an important contribution to the rural area, as well as contributing to a sustainable timber supply to meet the needs of Scotland’s growing timber processing sector. According to the National Forest Inventory 2013, there are approximately 56,850 hectares of woodland within the area, of which approximately 14,691 hectares are native woodlands (derived from the Native Woodland Survey of Scotland 2014).

Conifer forests are concentrated in the upland areas where farming has become or has always been marginal. Areas lacking rugged relief were favoured and consequently the largest plantations are found in the Southern Uplands, on the gentler plateau slopes of the Campsie Fells and Kilpatrick Hills, and in plateau moorland areas between the Clyde and Ayrshire Basins.

As later sections describe more fully, modern forestry policy aims to create multi-purpose woodlands which satisfy a range of objectives including commercial production, aesthetic amenity, recreation, and nature and heritage conservation. The more recent forest plantations and rotations are, therefore, more sympathetically designed and frequently incorporate felling coupes more closely related to landform in scale and shape, more extensive open space patterns, broadleaf and mixed conifer fringes and corridors, public access routes and recreational facilities. Within the Glasgow and Clyde Valley area, the Carron Valley Forest, Cuningar Loop and Whitelee wind farm contain recreational facilities.

Much of the broadleaf woodland is associated with principal and tributary rivers. The middle Clyde Valley, and its series of deeply incised tributaries, has some of the most intact and ecologically rich woodlands in the area, much of which is internationally or nationally designated. The Clyde Valley has a legacy of orchards, many of which have been lost or stand derelict, and a series of designed landscapes many with distinctive policy woodlands. Neighbouring areas of plateau farmland are, by contrast, more open and exposed, with woodland cover often limited to lines of field boundary trees and small farm woodlands.

Over the past decade, the Central Scotland Green Network Trust has made a significant positive contribution to vacant and derelict land, using woodland planting and other enhancements to improve damaged ecosystems and secure significant benefits for communities across the area. Across significant parts of Lanarkshire the pattern of coal mining and associated industrial activity has left a legacy of vacant and derelict land within a wider fragmented rural landscape. There is significant potential to further increase woodland cover in these areas to transform post-industrial landscapes but this needs to be balanced against the potential impact on this area’s industrial heritage.

The native woodland networks of the Clyde Valley and its tributaries are internationally important for their biodiversity value, as some of the most intact – and dramatically located – ancient and semi-natural woodlands in lowland Scotland. Similarly, being located within an hour’s drive for the majority of the nation’s population, they are highly accessible. They also incorporate areas of high cultural heritage value, taking in important areas of ancient wood pasture and the remains of medieval royal deer parks at Hamilton High Parks (in Chatelherault Country Park). Across the region, riparian networks hold a significant proportion of the higher quality native woodland resources – for example in the foothills of the Campsie Fells and the Kilsyth and Kilpatrick Hills. However, outside these relatively undisturbed areas, much of the region’s native woodlands are often both highly fragmented and relatively small in size. The ash-elm woodlands and ancient wood pastures of the Clyde Valley support rare and endangered species of deadwood invertebrates and are particular significance.

Trees and woodlands are an important aspect of the region’s urban areas. These features are key aspects of the quality, character and distinctiveness of the region’s historic towns and villages. Historically, extensive networks of new woodlands were created in parallel with the establishment of New Towns at Cumbernauld and East Kilbride, and these have matured into an important component of the region’s woodland resource. The region has already benefitted significantly from efforts to expand and positively manage woodlands in and around urban areas, through the work of the Central Scotland Green Network and the then Forestry Commission Scotland’s ‘Woods In and Around Towns’ (WIAT) programme. Successes of projects such as the Bishop’s Estate Woods, bringing a substantial area of woodland on the edge of Easterhouse into positive management, improving habitat, access networks and reconnecting communities to environmental assets, illustrate the potential that the region’s woods have in contributing to regeneration.

Trees contribute to the quality of urban greenspaces such as Strathclyde Park and Castlemilk Woodland Park, to formal squares and gardens such as those found across the West End, key river corridors including the Kelvin, Leven and the White Cart through Linn Park inGlasgow and East Renfrewshire.

New Towns such as Cumbernauld, by contrast, have an extensive planned greenspace network, much of which includes woodland Trees and woodlands are, however, much less common in large areas of social housing and some of the newer suburbs. There is significant potential to increase tree cover across the area’s townscapes, linking and extending existing habitats, providing stepping stones and corridors through the urban area, offering shelter and improving the physical environment. The area’s mixed woodland resource is primarily located in the region’s parks, gardens and designed landscapes, and in amenity planting associated with transport corridors and development.

Moorlands, bogs and mire

The moorlands are characterised by the abundance of heather but range from dry heaths with other ericoids such as blaeberry, bell heather, crowberry, and, on higher ground, cowberry, to wet heaths or blanket bogs, on shallow slopes, depressions or plateaux. In these areas graminoid elements such as purple moor-grass, deer-grass and cotton-grasses can be more extensive. The ecological interest and species diversity of relatively less disturbed areas can be high, supporting various herbs, and notably lower plants such as mosses, liverworts and lichens. The heather moorlands are often maintained by muirburn, and the patchwork result can be seen over much of the Southern Uplands, although inappropriate burning practices can have an adverse effect on upland habitats and species. Heather moorland has declined by about a quarter since the 1940s, with most losses occurring in the 1970s and ’80s in the Clyde Valley.

Blanket bogs, often the result of prehistoric land management coupled with climate change, are a feature of the poorly draining ground of slopes, shoulders and plateaux of the uplands. Heather with cotton grass are the main dominants, although cross-leaved heath, deer-grass and purple moor-grass can also be common; cloudberry is also a feature of the upland blanket mires above 400m. However a significant feature of bogs is the usually abundant growth of mosses, notably the main peat forming bog mosses (Sphagnum spp.). Where degraded the graminoid elements can become more prevalent, with cotton grass and purple moor-grass locally dominant. Extensive areas of blanket bog occur at Clyde Muirshiel in Renfrewshire, the summit plateaux of the Kilpatrick and Kilsyth Hills to the north of Glasgow, the moors above Eaglesham (the Whitelee wind farm area has a habitat management plan) and in the southern uplands.

There are many lowland raised bogs of national and international importance. Raised bogs, although superficially similar to blanket bogs, are more discrete units, typically developing in the lowlands, in shallow basins or on broad, river flood-plains, and may have been growing for several thousands of years. When in a relatively pristine condition they support a luxurious growth of bog-mosses with associate liverworts, other mosses and lichens, in addition to previously mentioned bog species. Raised bogs are well represented in the area with notable examples being Cranley and Carnwath mosses to the east of Lanark and Red and Coalburn mosses, north of Abington. Other sites occur on the urban fringe such as Blantyre Muir by Hamilton, Commonhead Moss (Local Nature Reserve), east Glasgow, Langlands Moss (National Nature Reserve), East Kilbride and Branchal Moss by Newmains. The western margins of the Slamannan plateau support a number of raised or intermediate bogs of note such as Black Loch (SSSI and SAC) and Lady Bell's (SSSI) Mosses.

Other mires, including, basin or valley mires and rush-dominated pastures usually occur in association with bog habitats but can occur as distinct units, and as noted with other wetlands, can significantly add to the species diversity and interest, when present as part of site habitat mosaics. Rush-dominated pastures are a very common landscape feature, often marking out drained hill slopes and rig and furrow drainage patterns in pasture grasslands, but are also important habitats at a range of sites, including marginal farmland, disused industrial workings and urban areas.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

The landscapes of Britain have been inhabited permanently since soon after the retreat of the last ice sheets around 10,000 years ago. Humans have, therefore, utilised and manipulated the landscape and its physical resources for millennia. The results of this activity can be characteristic of the landscape, although a legacy from all periods of history may not be evident. The land itself can obscure and distort our understanding of human activity in the past. Much of the Glasgow and Clyde Valley area has poorly drained soils which do not allow for arable agriculture. Over the past few decades our understanding of human activity in some parts of Scotland has been revolutionised by our ability to record and interpret the remains of otherwise invisible buried structures through the cropmarks they create in cereal or grass crops under dry conditions. Such conditions are rare in the physical landscape of Glasgow and the Clyde Valley and as a result our understanding of human activity in the past is hampered by the limited nature of the evidence.

Historical Landuse

Mesolithic Period (12,000-4,000BC)

The Mesolithic period was a time of massive environmental change in Scotland. Over 9000 years the landscape transformed from glaciers and tundra to a mixture of woodland, scrub, marshland and upland moors. The Mesolithic colonists of Scotland left little evidence of their passing due to their nomadic lifestyle. They survived by hunting, gathering and fishing and left little in the way of evidence for built structures.

Scatters of stone-working debris are often the only trace of human activity for this period and these can be found across much of the area. The earliest evidence for human activity in Scotland has been found in the upper reaches of the Clyde Valley. Around 13,000 years ago, a hunting party following game on the tundra recently exposed by the retreat of the ice sheets left a scatter of flint-working debris at one of their camps in an area just to the north of Biggar. There is a particular concentration of artefacts from all phases of the Mesolithic recorded in the upper Clyde valley. Beyond the area, in the hills near Peebles, was an easily accessible source of chert, a flint-like rock, and this would have drawn people to the area. An intensive programme of survey by a local heritage group has also revealed a richness of remains that may simply be undiscovered elsewhere.

Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Period (4,000-1,500 BC)

The Neolithic (New Stone Age) marks the introduction of farming around 6,000-5,500 years ago. The origins and spread of Scotland’s first farmers are hotly disputed, but farming appears to arrive as a “package” with domesticated animals and plants, new forms of stone tools, pottery and monumental construction projects. The first farmers would have altered the landscape, felling trees to create fields. Domesticated livestock would have been used to keep the cleared areas open.

Evidence for settlement and agriculture is rare for this period, largely due the intensity of subsequent land use and occupation, and there are no certain remains of Neolithic settlement in the area, the only possible exception being a few identified as cropmarks in aerial photographs. Perhaps, because people settled in an area, they began marking places in the landscape which were important to them, erecting massive monuments such as henges, long cairns, and stone and timber circles, which would have required the mobilisation of large communities to provide the labour necessary for their construction. Remains of these structures are also not common and those that are known are concentrated in the uplands of the Clyde Valley, where they tend to occupy unobtrusive locations within the landscape. The massive ceremonial enclosure at Blackshouse Burn between Thankerton and Hyndford Bridge exemplifies this. It is a huge sub-circular structure measuring 320 metres east-west and 310 metres north-south, defined by a stone wall just over one metre high and up to 11 metres wide, with entrances on the east-south-east and west-north-west. It sits in a natural south facing bowl on Swaites Hill surrounded by the multiple peaks of the hill, where it commends extensive views to the south but is also virtually invisible from the valley below. Excavations at the site showed evidence for multiple phases of rebuilding and alteration. Journeying to such sites and engaging in communal activities there appear to have been essential factors in their function and use. Burial monuments, such as at Burngrange and Greens Moor, show the same pattern with repeated rebuilding and manipulation of the human remains within the sites. There is a marked concentration of axes between Biggar, Lamington and West Linton, suggesting the area was intensively occupied.

To the north of the area there is a very different pattern. Apart from the two long cairns at Gallangad Muir and Stockie Muir on the northern slopes of the Kilpatrick Hills, the only clear evidence of Neolithic activity is the presence of cup and ring marked rocks in the hills around the mouth of the Clyde. These sites comprise circular patterns carved into bedrock often in areas offering extensive views across the surrounding landscape. There is a particular concentration of these carvings along the southern side of the Kilpatrick Hills, with the Cochno Stone being one of the most complex examples.

Between 2,500 and 2,000 BC, bronze artefacts start to appear in Britain. They are accompanied by a new form of pottery known as beakers and new ostentatious burial rites for individuals featuring intact bodies or cremations with grave goods placed either in large round burial cairns or barrows, often within or close to existing Neolithic monuments. The enclosure at Blackshouse Burn is ringed around with Bronze Age cairns, as are the long cairns at the head of the Westruther Burn north of Carnwath and the henge at Normangill Rigg north-east of Crawford. These Bronze Age cairns do not just focus on earlier sites but can be found across the area. The massive cairn on the summit of Tinto Hill dates from this period and dominates the point where the high ground of the southern uplands give way to the lower-lying ground to the north. Recent DNA analysis indicates that the individuals buried in this way are genetically distinct from the Neolithic farming community, hinting at an influx of new migrants with significant power and influence.

Later Bronze Age and Iron Age (1,500BC – AD50)

By around 1,500BC, the archaeological record has shifted from ritual and ceremonial sites towards settlement and field systems. The best preserved remains from this period are around the upper Clyde Valley, with numbers platform settlements surviving in the hills. These sites comprise groups of earth platforms cut into hill slopes to accommodate circular wooden houses, sometimes with associated yards and platforms for smaller outbuildings. This area also has a dense concentration of small round cairns or barrows, which is not found further north within the study area. At 45 metres in diameter, the round cairn on Tinto Hill in South Lanarkshire is one of the largest Bronze Age cairns in Scotland, visible from throughout the surrounding area. Fall Hill near Crawford is an enclosed cremation cemetery, and the only example of this type of monument to be identified with some certainty in Lanarkshire, but it is possible that other enclosures may belong to the same class. Some examples of these are to be found at Wester Yardhouses: at Hare Law and, to the southeast, at Horse Law. Together these monuments betray a significant expansion of settlement and farming, enabled by a substantial intensification of vegetation clearance. A cooling in the climate after 1,500BC, accompanied by environmental degradation caused primarily by land clearance and the development of peat in upland areas, meant these areas were gradually abandoned and the archaeological remains have survived undisturbed by later land-use.

In the first millennium BC there is an increasing emphasis on building settlements with substantial defences comprising varying combinations of ramparts, ditches and palisades. Sites like Arbory Hill above Abington and Sheep Hill near Dumbarton are classic examples of the type, but it is notable that there are few such sites in the area between Lanark and Clydebank. Black Hill and Fallburn Fort in Lanarkshire and Walls Hill Fort in Renfrewshire are exceptions and instead there seems to have been an increase in smaller fortifications, occupying less impressive fortifications, instead. There are also fortified headlands above the Clyde, with extensive complexes of ramparts, such as Castle Qua. This is in marked contrast to the settlement pattern in other parts of southern Scotland such as the Tweed valley and Dumfries and Galloway where substantial forts are more common.

The presence of a group of crannogs in the mouth of the Clyde estuary is another peculiarly local feature of the Iron Age in this area. Crannogs are artificial islands or platforms built in bodies of water that would have supported a substantial timber roundhouse. While they are reasonably widespread across Scotland, particularly in the west, they are almost exclusively a feature of freshwater lochs; the only similar group of such sites in a marine context is in the Beauly Firth.

Change during this period was not limited to settlement. Technical innovations such as the introduction of iron tools and the rotary quern would have increased the efficiency of agricultural production, while the increasing influence of the Roman Empire brought luxury goods like glass, jewellery, fine pottery and wine.

Roman Occupation (c.AD 70s - AD 390)

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley has some of the best evidence of the period of Roman occupation in Scotland. From the late AD70s, Iron Age life was disrupted by the invasion of the Roman army, and the Roman author Tacitus informs us that his father-in-law, the Roman governor and general of the province of Britannia, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, drove northwards. Archaeology paints a more complex picture but the first Roman remains in this area date to the later part of the 1st Century AD. Dominance was assured by a network of roads and forts which allowed the Romans to contain troubles and to prevent raids from locals living to the north. It has been suggested that the Selgovae, an Iron Age tribe whose territory probably included the Upper Tweed Valley and the easternmost part of the Clyde Valley, were opposed to the Roman invasion. This resulted in a strong presence in this area of the Clyde Valley. The fort at Castledykes and its associated annexes and temporary camps may have been constructed on the border of the lands of the Selgovae where they met with those of the Damnonii, who were sympathetic towards the Roman presence.

Trouble elsewhere on the continent caused the Romans to remove troops for action elsewhere, resulting in the withdrawal from the conquests in Scotland. By around AD 90 it is thought that all of the Roman forts had all been vacated. In the 120s, the Emperor Hadrian instructed his soldiers to build the Wall that bears his name, marking the northern limit of the Empire at that time. With the accession of Antoninus Pius as emperor In AD 138 came a new instruction to move north, reoccupy lowland Scotland and build a new frontier. The Antonine Wall was constructed to link the firths of Clyde and Forth, with outpost forts to the north-east and west plus a network of hinterland forts down the Clyde to the south. The valley was linked to the south by a road close to the line subsequently chosen for the present-day A74. Although the Roman army maintained its presence in southern Scotland till the 4th Century, including outpost forts for Hadrian’s Wall, there was no permanent presence in west-central Scotland.

The most significant assemblage of Roman remains in the area is the Antonine Wall, the line of which runs from Old Kilpatrick in the west through East and West Dunbartonshire and North Lanarkshire to Allandale in the east before heading over to Bo’ness on the Forth. In places along its length it is still visible as a rampart or ditch, and it has a number of forts, fortlets, other structures and camps associated with it. Good sections of remains of the earthworks can be seen between Dullatur and Twechar, particularly at Croy Hill, North Lanarkshire and at Bar Hill (Roman fort). Stretches of the Wall base can be seen in New Kilpatrick Cemetery, East Dunbartonshire. Other remains include the Bearsden Bath House, East Dunbartonshire, the fortlet at Lurg Moor, lnverclyde, and the Redshaw Burn fortlet, South Lanarkshire.

Early Medieval Period (c.AD200 - AD1000)

The early medieval period was characterised by many political and religious changes. There are relatively few records and very little archaeological evidence from this period: much of the history has been pieced together from the works of religious chroniclers working many years later.

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley was, along with much of the rest of west central Scotland, absorbed within the kingdom of Strathclyde, whose lands included the general areas of Dumbarton, Lanark, Renfrew and Ayr, with the seat of Strathclyde at Dumbarton Rock. Dumbarton Rock, known as Alt Clut, or Clyde Rock, occupying a key strategic location in the fledgling Kingdom of Strathclyde, was heavily fortified in this period. The rock was besieged by Viking forces in 870, only succumbing after four months. Following the siege Strathclyde became a hybrid mix of Norse, Gaelic and Brittonic culture. Strathclyde’s centre of power shifted away from Dumbarton, with a royal estate established further up the Clyde at Partick and an important assembly mound erected at Govan.

Christianity was introduced to west central Scotland in the early 5th Century by Ninian, who carried out missionary work from his base at Whithorn, Wigtownshire. It is Christianity that has left the greatest impression on the landscape from this period through the tradition of stone carving: raising ornate crosses, memorial stones and gravestones; examples are the Barochan Cross in Paisley Abbey and the stones in the New Parish Church in lnchinnan.

Govan Old Parish Church was erected over a much earlier church built near to an assembly mound or ‘moot hill’ believed to be of Norse origin. The church contains a number of hogbacks: large, ornate recumbent stones that are generally believed to originate to the Norse activity in the area. While often assumed to be grave markers, the function of hogbacks remains unclear. The church is also home to the Govan Sarcophagus, an ornate sarcophagus believed to be 9th or 10th Century AD in origin and discovered in the graveyard in 1855. Another collection of sculpture from this period was recovered from an ecclesiastical centre at Inchinnan close the historic ford across the Cart Water.

Glasgow Cathedral, first consecrated in 1136, stands on the site of a monastery founded by St Kentigern in the 6th or 7th Century AD. The cathedral and its surrounding precinct marks the location of the original medieval settlement of Glasgow prior to its gradual expansion westwards. The crypt is particularly fine, containing the tomb of St Mungo, Glasgow’s patron saint. The cathedral is also noteworthy for containing architectural details that survived the reformation, such as its rude screen separating the nave from the choir.

The Medieval Period (AD1200 - AD1600)

During the medieval period, the Scottish Crown sought closer links with the Norman aristocracy of England. The Norman influences which subsequently arrived changed the nature and style of architecture, the Church and Land laws. By the 13th Century, much of lowland Scotland was a feudal state society with castles, churches and towns. The Normans established shires, governed by feudal lords, as the principal form of administrative unit.

The church was reorganised during this period to follow the rest of western Christendom. The new structure was based on territorial divisions where a Bishop controlled a diocese from a cathedral base. The diocese was then further divided into parishes, each with its own church and priest. The early parish churches have largely been replaced with more recent buildings, but a piece of the original church in the form of a 12th Century Romanesque arched doorway is present in the wall of the post reformation church at Lamington in South Lanarkshire. Other medieval parish churches were adapted and largely survived as burial enclosures, such as St Kentigern’s in Lanark, Dalry and Killallan, near Houston.

Following the Wars of Independence, the centre of ecclesiastical power in the area shifted from Rutherglen to Glasgow. Whilst much reduced after the reformation Glasgow Cathedral contains much surviving medieval material, attesting to its former grandeur. A similar example can be seen at Paisley Abbey which attests to the influence of former monastic estates, which have now largely disappeared, mostly leaving only ruined buildings behind, such as Blantyre Priory.

The feudal overlords in medieval society granted lands and delegated functions to lesser lords and their vassals. The lands granted form the basis of many estates in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley and at the centre of these estates control was exercised from castles, home farms, tower houses or mansions. Early castles took the form of earthwork and timber mottes and baileys. A very well-preserved motte can be seen on the golf course at Carnwath. The glaciated landscape around the Clyde allowed easy conversion of drumlins and other glacial features into these defensive structures, and to a certain extent influenced their location. Many of these were gradually replaced during the 13th Century with stone structures. An example of this can be seen at the Bishop's Castle in Glasgow, where excavations show that a stone hall was added to an earlier earthwork castle.

This period saw the creation of a number of large and imposing castles, often built by royal or highly important families, and concentrated along the Clyde: most notably at Bothwell. Originally constructed in the 13th Century, Bothwell was demolished and rebuilt after a series of sieges throughout its life. Described as ‘among the foremost secular structures of the Middle Ages in Scotland,’ Bothwell Castle was originally conceived by Walter de Moray who acquired the land in 1242. The castle was laid out on a grand scale that demonstrated clear influences from the large castles of enceinte constructed by Edward I in Wales. Like these castles, Bothwell was originally intended to contain a large and imposing gatehouse of two towers. This, along with much of the curtain wall, was never constructed. The castle as it appears today was probably completed by Archibald ‘the Grim’ Douglas of Threave. Bothwell Castle’s most iconic feature is undoubtedly its massive, stout donjon or keep. This enormous round tower shows clear stylistic ties to castles in mainland Europe, indicating the wealth, societal connections, and cultural ties of its constructors.

Cadzow Castle, near Hamilton, was probably constructed between 1500 and 1550 by the second Earl of Hamilton. The Hamiltons were very much to the fore in the politics of state surrounding Mary Queen of Scots. The castle is unlikely to have been occupied following a siege in 1579, with the fifth Duke of Hamilton subsequently building the hunting lodge of Chatelherault close by in 1732. The picturesque ruins of Cadzow Castle were subsequently incorporated into the more formalised landscape around Hamilton Palace, with the castle showing evidence of being ‘romanticised’ with alterations in the 18th and 19th Centuries. The early artillery emplacements erected around Craignethan Castle, above the Clyde near Lanark, show that the area continued to be at the forefront of lordly design throughout this period.

Lesser lords tended to build much smaller castles, especially in the later medieval period. Where they have not been adapted as later homes their remains are a common feature in the landscape, with ruined towerhouses still visible ranging from relatively well preserved, publicly accessible and complex ones, such as Crookston Castle, to more ruined examples often re-used as eye catchers within later designed landscapes, such as Ranfurly Castle at Bridge of Weir, and other examples surviving in urban locations, such as Strathaven Castle or Stanely Castle which sits within a reservoir.

It was during the medieval period that many of the towns in the area were first established. Comparative stability and the new social order allowed trade to expand, and the main towns grew with merchants, minor nobles and a tertiary population of servicers such as market gardeners, artisans and tradesmen. The medieval origins of the areas towns can be seen in street patterns, churches and castles, most of which have been subsequently heavily adapted. A smattering of medieval townhouses also survive, such as in Lanark.

The majority of the medieval population was involved in farming through feudal tenancy agreements. Farm units tended to be a group of dwellings for several families with gardens or kailyards attached. Nearby was an "infield", an area intensively farmed on a run-rig system. Beyond the "infield" was the "outfield', which was cultivated but used less intensively and allowed fallow periods. The surrounding "common" areas of rough pasture were used for cattle grazing.

This system, which followed patterns possibly established during the Iron Age, but which is more likely to be connected to the introduction of feudalism, continued until the agricultural revolution of the 18th Century. It was responsible for further removing woodland from the area until it was largely devoid of ancient or semi-natural woodland. The religious orders, and particularly the monasteries, were responsible for large areas of land into which new agricultural techniques, crops and crafts were introduced. A vast area of Lanarkshire, for example, at this time appears to have been granted to the monks of Kelso Abbey. Further evidence of this type of landholding are “The Monklands”, centred on what are now Airdrie and Coatbridge. These towns are divided into the Old Monklands (Coatbridge) and the New Monklands (Airdrie). The name ‘Monklands’ goes back to the High Middle Ages, when the Cistercian monks farmed in the region. In 1162, the lands were officially granted to the monks of Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, by King Malcolm IV. Originally establishing farms and mills there, the Cistercian monks would keep these lands all through the Middle Ages, becoming the first people in the area to exploit the local coal. When the Reformation came to Scotland, the monks were dispossessed, and their lands given away.

18th and 19th Centuries

After the Act of Union in 1707, the pace of economic, political and social change increased dramatically. Throughout the medieval period, the landscape had changed very gradually: small changes to patterns which had existed for hundreds of years. Post medieval Scotland however, saw agricultural improvements, industrialisation, urban development and population growth all combining to change dramatically the landscape of Scotland and particularly west-central Scotland.

The improvements in agriculture during this period had a significant effect on the landscape. In addition to new technologies and the dissemination of improved methods of farming, many landowners replaced traditional yearly tenancies with longer ones to encourage farmers to carry out longer-term improvements to the land. Land was drained and enclosed, increasing the productivity, field sizes and human control over the land. Tree planting was considered a crucial element of improvement and very large numbers of trees were planted throughout the 18th Century. Much landscape woodland – avenues, shelter belts, copses and small and large plantations - have their origins in this period and in many cases are remarkably little changed in shape. Farmhouses and steadings became progressively better-built and more substantial, with much thought given to their design and layout. Many farm buildings from this period can be seen in the more rural parts of the Glasgow and Clyde Valley area and form an important element in the landscape.

Increased revenues from mining, trade and industry (and, to a lesser extent, improved rents from agricultural improvements) made landowners richer and helped to finance the mansions and planned landscapes of the estates. These are found throughout the lowland areas. One of the finest examples is the grounds of the Hamilton estate with the now-demolished Hamilton Palace and the still present Chatelherault garden building built in 1732. At Castle Semple, near Lochwinnoch, improvements carried out in the 1720s and 30’s were paid for by the profits of sugar plantations on St Kitts. Many 18th Century estates in the vicinity of Glasgow belonged to merchants who had made their money in tobacco or sugar. Estate planned landscapes throughout the region tend to have their origins in the 18th or 19th Centuries. Many have since suffered from decline or have been built over. In part, this reflects the changing economic position of many estates, but is also a result of planning policies that permitted redevelopment on parkland in preference to agricultural land.

Urban growth and industrial expansion occurred simultaneously, starting towards the end of the 18th Century and due primarily to the loss of the American colonies which changed the trading patterns of the time. Initially, spinning and weaving industries expanded; this is recorded dramatically by the cotton mills of New Lanark. These used the waters of the Clyde for power, and employed up to 2,000 workers to create one of the first mass production factories. Renfrewshire too had a major cloth weaving industry which grew around Paisley. Much of the preparatory work on the cloth was carried out by outworkers in villages such as Kilsyth, Cumbernauld, Condorrat and in Airdrie and surrounding villages: a weaver's cottage is still present at Kilbarchan.

By the start of the 19th Century, heavier industries such as coal and iron ore mining, engineering and ship building were starting to expand. The most accessible coal measures in the region were mined, as were locally abundant supplies of Iron ore and limestone. The Clyde and the Glasgow basin became one of the world's major industrial locations of the 19th Century. Ships were built all along the shores of the Clyde with major centres at Greenock and Port Glasgow in the west and Govan near the centre of Glasgow itself. They were marked out by their prominent cranes and covered yards. The Forth-Clyde Canal, built in the late 18th Century, allowed bulk transport of goods with the east coast; places such as Kirkintilloch built smaller boats such as tugs for the Clyde. While little can now be seen of the working of the coal and iron industries from the 19th Century, cast iron street furniture - including fountains, decorative lamp standards, bandstands and architectural ornaments such as balconies and braticcing (ornamental work along a ridge or cornice) - which was made during this period can still be seen in many towns in the Glasgow and Clyde Valley area. It was also exported to other parts of the world.

As the industries grew, so did the urban area within Glasgow and the Clyde Valley. The need for labour meant that the region became a magnet for migrants from the Highlands and other parts of Scotland as well as from England and Ireland. With so many new people in the area, the towns expanded to support them, industry owners employing them grew richer, and towns grew, with bulk housing for the poor and extravagant homes for the wealthy. It was around this time that Glasgow became the physical and economic centre of the area. Between 1755 and 1851 the population of Glasgow increased from around 23,500 to around 333,500, and by the beginning of the 20th Century was close to 800,000.

The area contained some of Scotland’s earliest railways, developed from the mid-1820s to serve the North Lanarkshire coal- and ironfields. The Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway was the first in Britain to specify steam locomotive haulage in its Act of Parliament (1824). This area also contained some of Scotland’s earliest main line passenger lines, including the Glasgow Paisley Kilmarnock & Ayr Railway, the Glasgow Paisley and Greenock Railway and the Edinburgh-Glasgow Railway, which opened in 1840, 1841 and 1842 respectively. Railways built along both shores of the Clyde in the mid-19th Century augmented established steam-boat services and encouraged the building of large numbers of weekend and holiday villas in settlements such as Skelmorlie, Helensburgh, Craigendorran and Rhu for wealthy Glasgow businessmen and their families. Many of these villas were built by leading architects of the day and are of the highest quality.

The introduction of the railway network to Lanarkshire caused large fluctuations in population there. Initially, the number of people living in areas such as Carstairs increased due to an influx of railway workers and their families around the once-important junction. Eventually, in some places the improved transport links caused a population decrease as people from the local communities became aware of the larger towns and cities nearby, with their thriving markets and new lifestyles. Places such as Thankerton suffered a decrease in population as the local tradespeople were usurped by the cheaper and more varied goods available in nearby Glasgow and Edinburgh. Overall, it appears that the farming communities in the area were least affected, and appear to have had the most stable populations over time.

20th and 21st Century Developments

Industry

The 20th Century saw the dramatic decline of Glasgow and the Clyde Valley's heavy industry. By the early 1900s, the mining of the Lanarkshire coalfields was slowing as shallow deposits in the area were 'worked out' by conventional methods. A few of the deeper pits continued to be worked until the 1990s. Evidence in the landscape for the mining industry remains in the form of many small bings and spoil heaps. The area has a number of examples of isolated housing groups, particularly over parts of the central plateau, a legacy of communities where mining once thrived.

Aggregate production in the area is 26% of all Scotland’s hard rock and sand & gravel. In relation to hard rock mined, 88% is retained within the city region. Distribution of sand and gravel shows 77% of production is retained within the city region. Exports can go further afield, such as the Lanark red granite chips which are in demand within Western Europe for road infrastructure projects. Some hard rock quarries have not been fully restored following mining operations.

In the 1980’s and 1990’s open-cast coal mining increased, with some large areas worked this way in North Lanarkshire in particular. This form of mining caused some locally significant changes in the landscape. Past open-cast restoration schemes have often produced constant engineered gradients, unrelieved by localised changes in topography or vegetation and lacking the features and grain which combine to create landscape character. In parts of the area, sites have not been fully re-instated, due to financial and legal issues, resulting in unnatural slopes and mounds which can have a considerable negative effect on the landscape as a result.

Peat, used for horticulture, has been extracted commercially on parts of the central plateau south of Cumbernauld, having a locally significant effect on the landscape of the plateau. In South Lanarkshire, there have been impacts on the landscape due to the extraction of sand and gravel. This extraction has been responsible for the removal of local archaeological sites but has enabled several archaeological discoveries. This type of landscape modification is evident in areas around the Tinto Hills. Sand and gravel extraction continues, for example, in the valley of the upper River Avon near Drumclog.

Shipbuilding and steel making, core industries of the conurbation, struggled to survive after the Second World War. The major steelworks all closed during the 1980s and early 1990s, and the Clyde now has only two working shipyards. The towers of the Ravenscraig Steelworks by Motherwell were a significant feature of the landscape until they were removed in the mid-1990s. The area is now home to one of Europe’s largest urban regeneration projects with £200 million investment on the 1200 acre site creating 1000 homes, sports and community centre, new green space, transport infrastructure and employment opportunities. Some of the quays, sheds and cranes (such as at Finnieston Quay, and the Titan crane at Clydebank) on the Clyde in Glasgow have been retained as landmarks and reminders of Glasgow's shipbuilding past. Many former industrial sites have been cleared to provide 'brownfield' land for redevelopment, or are being redeveloped for new commercial, infrastructure, public amenity, housing, leisure and retail uses. Prime waterfront examples include the Glasgow Science Centre, IMAX, the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre (SECC) national exhibition centre, the Armadillo and Pacific Quay which are all clustered here, along with the distinctive footbridge that is the Clyde Arc. One of the major successful developments is the creation of the new SSE Hydro, a major new venue for Scotland. On the south bank of the river, Creative Clyde provides a focus for creative and digital activity, with the BBC and STV studios both located here. Many of these buildings have formed new landmarks. Further upstream, a group of sports facilities and housing in the east end of Glasgow and at Clyde Gateway form part of the Commonwealth Games legacy from 2014. Other sites remain derelict or contaminated and have been the subject of a range of initiatives designed to improve their environmental quality. Several of these sites are found adjacent to, or within settlements.

The decline of heavy industry in the 1980s prompted programmes designed to attract new development and inward investment. These focused on low density business parks, information technology manufacturers and distribution businesses and are generally located on the edge of settlements and similar locations accessible to the motorway network. This investment had the effect of increasing pressure on surviving fragments of countryside around and between settlements in the conurbation. Pressure has been greatest on the eastern side of Glasgow, particularly in the sector served by the M8/A8, M80 and M74, but the trend is evident in other areas also, such as Mossend Rail Freight Terminal, Eurocentral, and the expansion of Newhouse industrial Estate. There has been less emphasis on speculative development of business parks in recent years with most new developments being bespoke premises for the relocation or expansion of existing businesses. The location of businesses on the edge of settlements has contributed to the decline of town centres.

Urban Redevelopment

The pattern of residential development has also seen changes. The population is concentrated in Glasgow and the larger towns in its hinterland such as Hamilton, Motherwell and Paisley. Past periods of development created relatively high density settlements, exemplified by the tenement areas of Glasgow.

After the Second World War, Glasgow suffered from significant problems of overcrowding in a city whose housing stock dated largely to the Industrial Revolution. The city’s subsequent efforts to tackle its housing crisis have been described as one of the more extreme episodes in the history of post-war rebuilding. The Gorbals in particular had become the most impoverished and overcrowded urban area in western Europe. Two plans were devised to solve this problem: the Bruce Report (by City Engineer Robert Bruce) and the Clyde Valley Regional Plan (by Sir Patrick Abercrombie, the pre-eminent planner of the era, and Robert Matthew) both published in 1946. The Bruce Report advocated rehousing the city’s residents within city limits in modern high-rise flats; the Regional Plan estimated that 250,000 Glaswegians would need to be ‘decanted’ to New Towns at East Kilbride, Cumbernauld, and Bishopton.

In the event, elements of both plans were adopted. In the 20 years after the war, Glasgow saw an extensive rebuilding and infrastructure development programme that fundamentally altered the character of the city. High-rise tower blocks were built across the conurbation from Drumchapel in the northwest to Kennishead in the southeast. These buildings, emblematic of post-war redevelopment, dramatically altered the Glasgow skyline. Some of the most iconic of these were the series of massive slab- and point-blocks constructed at Red Road and the Basil Spence-designed blocks constructed at the Gorbals. Through a combination of poorly-planned infrastructure and growing stigmatisation of tower blocks, both schemes (along with other tower blocks in the city) were later demolished by Glasgow City Council.

Other tower blocks were constructed in the City Centre, such as those at Cowcaddens and the Richard Seifert-designed towers at Anderston. Anderston and the surrounding areas saw wholesale demolition in the 1960s for the creation of the M8: a new motorway that was driven through Glasgow city centre, forming an “inner ring road”. Ultimately, only the north and west flanks of this ring road were built. This has resulted in various dead-end slip roads and “bridges to nowhere” appearing across Glasgow’s motorway network. The most famous of these is the Tradeston “ski jump” which would have met the southern flank. A modified version of this section was later constructed as a stretch of the M74, joining the M8 100m to the south, in 2011.