Landscape Character Assessment: Dumfries and Galloway - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The PDF version of this document can be found at the foot of this webpage

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten.

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of:

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot/

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in “Dumfries and Galloway Landscape Character Assessment”, Land Use Consultants, 1998, SNH Review No 94.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

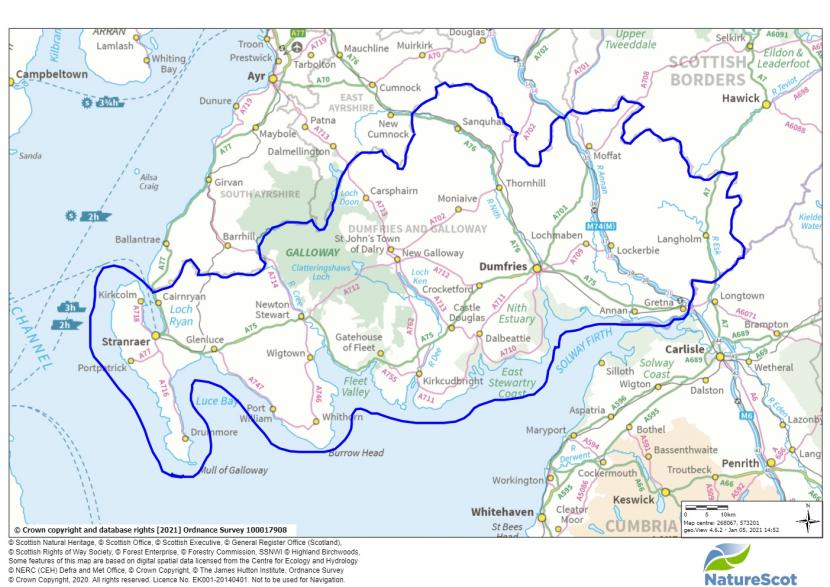

Dumfries and Galloway is located in south-west Scotland. To the north, the region shares borders with South Ayrshire, East Ayrshire and South Lanarkshire; to the east with Scottish Borders; and to the south with the county of Cumbria. Dumfries and Galloway occupies a land area of approximately 6,439 km² and has a coastline of 350km. To the south is the Solway Firth, one of the largest intertidal mudflat and salt marsh areas in the United Kingdom. The western boundary is the North Channel of the Irish Sea with Loch Ryan opening just to the south of the Firth of Clyde.

The area is celebrated for if natural heritage. It contains most of the Galloway Forest Park and the Galloway and Southern Ayrshire Biosphere core area, as well as the Galloway Dark Sky Park.

Its population of approximately 147,284 is projected to grow to around 150,000 over the next 10 years. Over a quarter of the population live in Dumfries, the largest town in the area, Stranraer and Annan are the next largest settlements. Overall the region has low population density of 23 persons per km2.

The countryside of Dumfries and Galloway region shows a great diversity of landscape character which results from the interaction of both the physical and human influences on the area. It has four distinctive regions the Rhins and Machars, the Galloway uplands, the west southern uplands and the Dumfries coastlands:

The Rhins and the Machars

These areas make up the western section of Dumfries and Galloway, following similar boundaries to that of the original county of Wigtownshire. It includes principally the Rhins (including the Mull of Galloway), the Stranraer lowlands, the Machars peninsula and the Luce moorlands. The underlying geology is mostly Ordovician and Silurian greywackes, known locally as whinstone, and shales, with new red sandstones under the Stranraer lowlands. The area has been extensively modified by glacial deposition and erosion, producing an undulating landscape of relatively low altitude.

Even inland the area is strongly maritime in character shaped by the Gulf Stream. This is a predominantly pastoral landscape and traditionally the dairy heart of Dumfries and Galloway. Large dairy farms are characteristic features, as are the grazing enclosures and herb rich pastures. The highest areas are towards the north east, where moorland plateaux and mossy basins form in the upper catchments of the area's main rivers: Water of Luce, River Bladnoch and Tarf Water. Closer to the coast cattle and sheep graze on salt marsh around the Machars

Galloway Uplands

The Galloway Uplands are centred on the Merrick uplands and are closely defined between the valleys of the Rivers Cree and Dee. The underlying geology is dominated by the granite intrusions of Cairnsmore of Fleet and the Merrick. This includes the metamorphic aureole which contains a number of dramatic physical features such as the Rhinns of Kells.

The area is characterised by its relatively rugged and wild topography. The core area is one of Scotland's Wild Land Areas. A large proportion of the area is within the Galloway Forest Park and the Galloway and South Ayrshire Biosphere and, therefore, forest management for recreation, the environment, soil condition, biodiversity and natural drainage is an important characteristic.

West Southern Uplands

The West Southern Uplands constitute the landscape of uplands and dales that extends eastwards from the valley of the River Dee. The underlying geology is predominantly Ordovician and Silurian greywackes (commonly known as whinstone) and shales, with some significant areas of Permian red sandstone in Nithsdale and Annandale. The West Southern Uplands are characteristically smooth, conical peaks with extensive foothills and plateaux. Forestry, upland sheep farming and game management are principal land uses, except in the dales where more cattle are grazed. Arable crops and grass silage are grown within walled and hedged enclosures.

This area differs significantly from the Galloway Uplands in its more uniform topography and absence of rugged landforms. Forestry, although extensive, does not (as yet) have such continuity of cover.

The main settlements and lines of communications are in the dales. The presence here of underlying red sandstone is reflected in the building materials and in the red soils of ploughed fields around Moffat and Thornhill. The dales also contain major country houses, designed landscapes and many features representative of a rich cultural history.

Dumfries and Galloway Coastlands

The Dumfries Coastlands comprise the lower dales and a variety of landscape character types centred on Dumfries but forming a coastal belt between the Southern Uplands and the Solway Firth. The underlying geology is complex, comprising granite, red sandstones and carboniferous sandstones. These are expressed in the distinct differences in local building materials. The effects of glaciation are also significant; features of both erosion and deposition are characteristic of this area, especially drumlins and kettleholes.

Agriculture is an intensive mixture of arable and grazing. Both drystone dykes and hedgerows are features of its landscapes with localised styles. The influence of designed landscapes is also strong, reflected in both countryside and architecture.

This is a settled landscape containing the most developed parts of Dumfries and Galloway, including some of the main towns in the region, such as Dumfries, Annan and Kirkcudbright. The single east to west main trunk road links with other parts of the region's road network. The sole communication east to west is by road, by-passing the settlements; north south routes, both modern and historic tend to follow the principal rivers. An east to west railway line was stopped at Dumfries many decades ago, but railway structures remain in the landscape. Many old roads are still in use, following the coastal though the newer roads are inland and bypass many of the smaller coastal settlements Trade and communication by sea has been influential in the development of a small number of coastal towns and harbours.

The coastline itself is dissected by estuaries which afford scenic views of a high order, as reflected in the three National Scenic Areas. The contrast between coastal flats and uplands, especially granite peaks such as Criffel, is an important part of this experience and an essential component of its character. The views to small islands are distinctive and, from the Solway Firth mouth and the outer coastal edges, the Isle of Man is visible in good weather.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Solid Geology

The solid geology of Dumfries and Galloway is composed mainly of sedimentary greywackes and shales of the Ordovician/Silurian period, with areas of new red sandstone and the major intrusive granite masses of Criffel, Cairnsmore of Fleet and Loch Doon. Granite is also found around Dalbeattie, Canonbie and Creetown. The sedimentary bands are oriented north-east to south-west. Basins of coal measures also exist, predominantly around Sanquhar in the north of the region, but also around Canonbie in the east. In the south-east, sandstone and limestone occur.

The younger, softer sandstones are more easily eroded than older, harder granite and basalt, and have influenced the evolution of the drainage pattern. For example, the course of the Nith has been largely determined by the presence of basins of younger rocks, especially the Permian sandstones. Dumfries is located in the centre of the largest of these basins which is also a topographic hollow. Loch Ryan, the Stranraer lowlands and much of Luce Bay have been carved from a partly submerged basin of Permian sandstone. The course of the Esk carves through harder basalt and andesites and so remains narrow. Sediments have provided excellent building stone, and their colours and textures are distinctive features of the built environment including the variation and distinctive appearance of dry stone dykes in different parts of the region’s landscape.

The harder Ordovician and Silurian sediments have been more resistant to erosion remaining as the extensive Southem Uplands range. This is typified by conical domed peaks incised by deep valleys in many areas. In contrast, the granite intrusions have created a more rugged landscape with more obvious outcrops in both the granite and its metamorphosed rim. The main granite peaks (Cairnsmore of Fleet, Criffel and Cairnsmore of Carsphairn) are essentially domed masses, but the exposure of white/grey granite on their flanks, and its use in drystone walling, is distinct from the predominant greywackes and shales. The Criffel, Cairnsmore and Loch Doon intrusions contribute significantly to the relief of Galloway. Loch Doon granite is slightly different from the others in that few of the highest summits here coincide with the granite outcrop. Only in the ridge of Mullwharchar does white central granite play a major role in the relief. The surrounding mountains (including the Merrick and Rhinns of Kells) are not found on the granite itself, but once roofed the massive intrusion. They have worn away and now survive only on the flanks where they create a prominent ring of uplands surrounding the central granite ridge of Mullwharchar.

The region has also been affected by volcanic intrusions in the form of basaltic sills and dykes. These are limited in extent, but have been quarried as hard building stones in certain areas and have influenced the formation of minerals in the surrounding sediments.

Drift Geology

The solid geology of Dumfries and Galloway has been modified by glacial action. During the last main glacial, the region was covered by the Southern Upland ice sheet, with the Merrick and Cairnsmore being a major source of valley glaciers. Glacial action has tended to have a rounding effect on the topography, for example in the deepened valley of the Devils Beef Tub north of Moffat, and the wide dome of the summit of Broad Law. The signs of glacial activity are most numerous around the Merrick and Rhinns of Kells. Loch Doon (mostly in East Ayrshire) occupies a glacially-over-deepened trough, and Loch Trool infills a u-shaped valley. The mountainous heartland is, therefore, very rugged, reminiscent in places such as Merrick of the western Highlands.

Outwith the granite areas, the landscape softens in texture, with great spreads of glacio-fluvial deposits, especially in the lower Dee valley which supports some of the most productive dairy farms in Scotland. Glacio-fluvial drift is widespread in the southern uplands and contributes to the smoothly contoured slopes. Within these areas of deposited material are the distinct drumlin landforms. These were created as an ice sheet carrying till at its base crossed an obstacle such as a boulder which would not be dislodged, obstructing the smooth flow of the glacier. Till became lodged around such obstacles and was streamlined in the direction of glacier flow as the ice moved over the obstacle, creating the distinct landforms still evident today.

Although sedimentary records suggest a maximum glaciation about 22,000 years ago, multiple readvancements and deglaciation episodes are indicated in this area. Glacial conditions returned c10,800 years ago with ice caps on high ground feeding valley glaciers. This re-advance was limited and is shown by a series of moraine ridges. Sea level rise which accompanied deglaciation, along with isostatic recovery at the end of the glaciated periods, caused major fluctuating adjustments between land and sea. The results are raised beaches and estuarine areas, and incised valleys inland. The importance of post-glacial raised beaches in the landscape here lies in their effect on coastal settlement and land use, as the raised shoreline added many square miles of low marsh to the coastal fringe. Good examples are present at Luce Bay and Loch Ryan, as well as the wide expanses of raised beach deposits on the Nith Estuary, stretching from Dumfries to Southwick Water and relatively late examples at Powfoot and Barnkirk Point. The coastal fringes were not subject to intense erosion by ice and there are extensive spreads of glacial drift. Rolling drift-covered landscape can have a more uniform colour, and is often used as pasture - much of this landscape has been improved to give fertile farmlands, for example the Machars area. The Rhins was probably an island in late glacial times and clear drumlin fields are present on both the Whithorn and Rhins peninsulas.

At the coast, hard rock headlands are separated by bays of softer rock. In more detail, it is the drift deposits of glacial and post-glacial derivation which largely shape this landscape: the lowlands of Wigtownshire provide contrast to the moorland landscape of Carrick and the Stewartry. Along the Luce Bay coast is the most extensive sand dune system in Galloway, with some dunes over 15 metres high, still highly dynamic and actively building.

Soils

The predominant underlying geology produces stony, loamy drift over the hills, with clay tills in the valleys. The eastern part, underlain by sandstone, has deeper sandier drifts with good drainage. The river valleys in the region contain deposits of alluvium, glacial meltwater deposits (kames and terraces) and raised beach deposits. The high rainfall and humidity of the area have been conducive to peat growth, and bogs are, therefore, common on upland plateaux, lower slopes and even on valley floor where they are termed 'flowes'.

On high plateaux, there is blanket bog. Bog and marsh form distinctive features of the landscape: raised bog (flowe), salt marsh (merse), and heather moor is frequently found on this soil, often creating areas of nature conservation value protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Peat is extracted near Annan and above Langholm and forestry has been planted in peatland, all of which have the potential for restoration. The lower areas, especially near the coast and on the Rhins and Machars peninsulas, show agricultural capacity of high and moderate yields of cereals although in practice this is focussed on the coastal plateaux and some other crops. Highland areas show better suitability for grazing and forestry and the hinterlands are suited to improved grassland and high quality grazing. This has heavily influenced the rural and domestic landscapes of lowland Dumfries and Galloway with the fields, boundaries and even the identifiable cattle breeds contributing to the identity.

Hydrology

The landform of Dumfries and Galloway is dissected by river courses running north-south into the Solway Firth, and it has been suggested that, despite the enormous amount of glacial modification, the present drainage system originated in mid Tertiary times.

The main river systems from east to west are the Esk, Annan, Nith, Urr, Dee/Ken, Cree and Water of Luce. There are over 25km2 of lochs within the region, some of which have been artificially created through flooding, such as Clatteringshaws Loch. This is part of one of the earliest hydroelectric schemes in Scotland (built between 1930 and 1936); the Galloway scheme also includes Loch Doon on the northern boundary of the area. These provide water supply, electricity and are important recreational areas. Loch Ken and Loch Trool are flooded valley ribbon lochs, although Loch Ken has been enlarged. Most lochs in the lowlands are of glacial kettle-hole origin, small, shallow and saucer shaped eutrophic (rich in nutrients and so supporting a dense plant population). Examples include Whitefield Loch, Castle Loch, White Loch and Black Loch. The shores of these merge into marshy grasslands and woodland with a range of wetland plants and important wildfowl habitats. In the uplands, they occupy basins and glacially carved hollows.

Climate

Historic climate

Climatic factors have played some part in the shaping of the physical landscape. The last ice age, which reached its climax around 18,000 years ago, created the most significant climatic influence on the contemporary landscape. Very cold temperatures allowed the formation of valley glaciers and ice sheets which carved their way through upland areas and deposited vast quantities of debris in the low-lying outwash plain.

Climatic improvement around 12,000 years ago led to the gradual retreat of ice and subsequent isostatic recovery as the land, now free of ice readjusted itself accordingly creating coastal landforms such as raised beaches and incised valleys inland. Around 3,000 years ago, the climate deteriorated which, along with woodland clearance for agriculture, created conditions for blanket peat to develop.

Climate has affected the development of soils in the region and has been one of the influencing factors in the proliferation of dairying as a land use, although human decision making in the 18th and 19th Centuries arguably played a larger role.

Climatic factors have been significant in the evolution of human settlement which has left its mark in the physical landscape. For example, the deterioration in climatic conditions in the 7th Century BC led to a period of sophisticated fortification as a struggle ensued to seize and control larger areas of land for production.

Current Climate

Today Dumfries and Galloway’s climate is maritime in character and heavily influenced by the Gulf Stream. The mild wet seasons and predominantly westerly and south-westerly winds mean less difference in seasonal temperatures and high average rainfall. Winter and autumn are the wettest seasons with around 45 days with rainfall per season in autumn and winter near the coast, rising to 55 in upland areas and 35 on the coast in spring and summer, and 40 in upland areas.

Mean daily temperatures in the coastal areas are between 1°C and 6°C in January and 12°C and 20°C in July. This drops significantly in upland areas where snow is more likely to lie in winter months, albeit in restricted areas.

Future Climate

Future climate change due to human actions are looking likely to increase the temperatures but also increase the strength and frequency of storms, especially in winter and autumn. This could an impact on infrastructure and soil quality.

There are also significant predictions for sea-level rise due to the loss of ice in the Polar Regions. The Solway estuary has very low-lying areas within it which may be affected by a future change in sea level and increased salination. These include wetland bird habitat as well as land used for agriculture and tourism. Damage to infrastructure, such as harbours, roads, and settlement, may occur and exacerbate existing erosion, especially at the coast. The loss of the wetland and dune habitats could also leave inland areas more vulnerable to storm surge damage.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

The Dumfries and Galloway area has been home to humans for over 8000 years. Its location near the sea and close to other trading centres meant that it received new ideas and people, and its fertile soils meant that it was good for both hunter-gathering and farming to establish.

Early Settlement

Mesolithic 7,000 B.C. - 3,500 B.C.

The first evidence of human activity in the landscape dates to the hunter-gatherer fishing communities of the Mesolithic era. Collections of artefacts, found along the coast, are the main evidence of these communities. Stone tool assemblages are often formed of cherts from rock outcrops at Loch Doon at Water of Ken. More exotic raw materials for tool making have also been identified, brought from the Inner Hebrides and Cumbria.

The most significant deposits are located around the shores of Luce Bay, Loch Doon and Loch Ryan. The earliest known site in Dumfries and Galloway is at Redkirk Point, Annan, where an excavated hearth has been dated to 6900 BC; whilst Barsalloch on the east side of Luce Bay has been dated to around 4,000 BC. Many other Wigtownshire coastal sites, such as Dunragit, are probably of a similar age.

A number of Mesolithic sites have also been found alongside some of the region's rivers and inland lochs. Excavations at Irish Street in Dumfries uncovered a camp used by people fishing the lower reaches of the river Nith. Similar sites have been found close to the Tarf Water in Wigtownshire and on the banks of the Annan at Kirkhill in eastern Dumfriesshire. A large, barbed red deer antler point was found in the bed of the River Dee at Cumstoun, where it may have been used to spear salmon and was radiocarbon dated to around 4600BC. It is one of a handful of such barbed points found in the west of Scotland; another, larger tool of very similar date was found by a relict shoreline at Irvine in north Ayrshire.

Other concentrations have been found around the shores of Lochs Doon, Dee and Grannoch and Clatteringshaws Loch. In some cases, traces of related activity have also been found such as the dated fire-spots on the west shore of Clatteringshaws Loch.

A small number of similar sites have also been discovered in upland areas, such as that found during forestry operations at Twiglees. Excavations at Starr Cottage, Loch Doon revealed a camp site dated to 4,300 BC and a similar date has been obtained from another campsite at Smittons near Carsphairn. Some of these upland camps may have been set up next to woodland clearings where the open grazing attracted wild animals. There is even some evidence from pollen cores taken in the Galloway hills that Mesolithic hunters were deliberately burning woodland to create grazing areas. The survival and discovery of these early sites remains rare, despite probably having been heavily used by Mesolithic populations.

Neolithic 3,500 B.C. - 2,250 B.C.

The earliest farming communities of the region, dating to the Neolithic period, are better known to us through their burials rather than through their houses or agricultural activities, though two Neolithic long halls have been excavated at Beckton and Broomhouses near Lockerbie. These are evidence of the sophistication of Neolithic activity, and also represent regional distinctions, being absent from the west coast and uplands. Intra-regional differences could suggest that the more open, fertile valleys to the east attracted more abundant and organised early farming communities, while the topographic and soil conditions elsewhere were more conducive to smaller, more dispersed communities. The local economy may have been essentially pastoral with family groups following their animals from winter to summer pastures, though pollen cores indicate that extensive woodland clearance commenced in the Neolithic. Marine resources - fish, shellfish and seals - continued to be an important part of the local diet.

A number of polished stone axes have been found around the head of Kirkcudbright Bay and the River Dee estuary. Almost all are fine-grained greenstone, a volcanic tuff that outcrops along a narrow range of high peaks in Langdale. Polishing improved axes' mechanical strength and also produced exquisite objects, to which people seem to have attached symbolic as well as practical meanings that may have connected woodland clearance with the construction of communal monuments and associated belief systems.

There are various types of tombs across the region. In Dumfriesshire and eastern Kirkcudbrightshire the most common tomb type was the un-chambered long cairn. Those at Lochhill, New Abbey, and Slewcairn, Dalbeattie were built over the remains of earlier mortuary structures which were deliberately burnt down, suggesting many had long-standing associations with burial. Around Newton Stewart and the Cree Valley the preference was for a round cairn covering one or more burial chambers with simple entrance passages, such as White Cairn, Glentrool. Elsewhere in Galloway, and on Arran and in Ayrshire, huge wedge-shaped cairns, known as Clyde cairns, were built, of which the best example is at Cairnholy, near Carsluith. In Eskdale, a highly unusual form of cairn, a bank barrow, 2km long was erected: Long Tom’s Knowe is a bank barrow, which extends across both sides of the valley of the River Esk.

Cairns were enormous construction projects that created new features in the landscape on an unprecedented scale and may have been used to highlight route-ways across the landscape, such as that at High Cornarroch along a long-established routeway through the uplands from between the river systems of the Doon and Dee, and another near Carsphairn. Some stone circles and standing stones, like those at Holm of Daltallochan appear to straddle or overlook natural routeways, those paths of least topographic resistance along watercourses and through the hills. Many also have some relationship to rivers, burns, lochs and springs, for example, at Stroan Loch a stone circle overlooks the narrow valley of the Black Water of Dee as it flows towards confluence with the Water of Ken.

Towards the end of the Neolithic around 2300 BC and on into the Early Bronze Age, local groups were joining together to build huge ceremonial monuments. One of the most dramatic was at Dunragit near Stranraer where three enormous timber circles were built one with another. The largest circle was over 100m in diameter, five times the size of Stonehenge, with an avenue pointing to an earth mound, still visible, and out to Luce Bay beyond. Droughduil Mote is a highly visible remnant of this important ritual landscape.

Bronze Age 2,250 BC- 700 BC

This was a time of social change, often driven by climate fluctuation, illustrated by the emergence of hierarchical tribal societies dominated by an elite of chieftains and warriors.

By 1500 BC the climate was some 2°C warmer than it is today. This meant that crops could be grown in areas at a higher altitude than is now possible and many upland areas of south-west Scotland were farmed. An agricultural surplus, plus control of natural resources like copper or and gold, created a degree of wealth which supported the area's elite. The climate worsened around 1100 BC and the upland margins were abandoned. As people were forced into a smaller area, tension and conflict ensued over resources. The period from 1100 BC to 200 BC saw the development of hilltop forts and defended settlements, as well as the development of specialised weapons such as the sword and dagger.

The meanings of formerly significant places for communal gathering and ceremony seemed to shift, as did people's relationship to the landscape. The old chambered cairns, stone circles and henges became foci for new burial practices. Instead, mounds and cairns were built to cover a single burial, often placed within a stone box or cist and accompanied with pots and stone and metal tools. This commemoration of the individual is in direct contrast to the communal burial tradition of the preceding Neolithic and demonstrated a degree of social division.

Bronze Age cairns are common in the western uplands, especially on Creeside, for example along Coldstream Bum and Cambret Moor. Examples of rock sculpture remains from this period in the cup and ring markings which are found in well over a hundred locations in Galloway, mainly in the Machars and below Creetown, but with many good examples around Kirkcudbright.

Several cairns bracket the rock art at High Banks and neighbouring Galtway Hill and contained cremated human remains and Beakers. In some places, such as New Luce area of Wigtownshire Moors, burial cairns can be found close to small settlements.

Stone circles are another type of Bronze Age monument and known across the region, from Torhusemuir near Wigtown, via a cluster of four on Cambret Moor, through the Twelve Apostles by Dumfries to the Loupin’ Stanes and Girdlestanes in Eskdale. Stone circles had a ritual function, probably connected with rites of passage, death and burial. Standing stones are another type of ceremonial monument from this period. The Laggangairn Standing Stones are likely remnants of a larger circle from early in this period. The two remaining stones have been repurposed by medieval pilgrims and crosslets in the style of this era have been carved on them. Generally sited in dramatic locations, standing stones appear to have marked divisions in the landscape, especially boundaries between the everyday world of the living and the spirit world of the ancestors.

Features like hilltops, lochs and rivers became the focus of deliberate, votive deposition, involving metalwork in particular, much of it brought from other regions. This can be seen at Carlingwark Loch where objects such as a bronze sword and a sandstone axe-hammer have been found dating from this period.

Bronze Age settlement usually consists of circular stone-built houses or 'hut circles' - associated with stock enclosures, field systems and agricultural clearance mounds, often with a visual relationship with nearby burial cairns. Substantial houses in open settlements with field systems dominate the upland record from this period, although these more sedentary, domesticated landscapes are likely preserved by the lack of modern agriculture or development in the uplands. One of the largest concentration of prehistoric settlement and agricultural remains, including round houses and cairnfields, is on the southern edge of the uplands between Loch Whinyeon and Laughenghie Hill. Small farming settlements like these were probably abundant across both lowland and upland areas.

Across these upland areas and by water courses are abundant burnt mounds, which consist of heat-cracked stones that were heaped up around a stone trough, were probably outdoor cooking or industrial sites. Like the settlement remains, their distribution was once much more extensive, as has been proven by topsoil stripping of a transect across Dumfries and Galloway.

Iron Age c700 B.C. - A.D. 400

The tribes who lived in this region were referred to as the Novantae by Roman historians. From the 7th Century BC, in addition to the characteristic open settlements of the Bronze Age, a new process of sophisticated fortification was taking place. Poor climatic conditions made farming difficult and farms and camps had to be defended against the struggles to control greater areas. The process of forest clearance was well under way before the Iron Age, and now southern Scotland saw an unprecedented burst in woodland clearance to extend agricultural territories and build enclosures.

People lived in small settlements, practising a mixed agricultural economy, growing a form of barley and raising cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. The high standard of metal goods found in Galloway indicates a wealthy society, which may have been based on the exploitation of its copper resources. There is possibly an early mining site at Tonderghie, near Whithorn, and mining tools and ingots have been found at Barhullion near Port William.

From the early to mid-1st millennium BC, many communities in southern Scotland began building defensive homesteads and enclosures defined by ramparts and ditches. While many were highly impressive, elite forts positioned on the spurs or summits of hills, others were more domestic, in low-lying places and have been truncated by later land use. Hill forts are more common in Dumfriesshire and Kirkcudbrightshire than in Wigtownshire. A particularly good group are found in the valley of the River Esk and now promoted through the Eskdale Prehistoric Trail. Included in this group are small promontory forts found along the coastline of South-West Scotland such as Rockcliffe, Balcary and Mull of Galloway.

Less impressive enclosures include Rispain Camp in Wigtownshire, where a small number of round houses might be clustered together and enclosed for defence and/or as a statement of community identity. Similar examples can be found at The Boonies in Eskdale or visible as cropmarks, such as Carronbridge and Ward Law.

The Iron Age also saw the erection of a small number of notable coastal broch-like duns found in western Galloway and at Castle Haven, Borgue. These types of structure are more commonly found in the north and west of Scotland, and indicate the spread of building customs down the west coast and into Galloway as well as relating to broader social and architectural trends around the Atlantic coast of Europe.

Iron Age round houses can also be found on artificial platforms in lochs. There are many examples of these crannogs in Galloway, for example at Black Loch of Myrton near Monreith, or Dowalton in Wigtownshire. Lochs and bogs appear to have been of religious or ritual significance during the Iron Age, for high value metal goods have been recovered from them, which appear to have been deposited as a ritual offering. This includes the Carlingwark hoard deposited in a cauldron in Carlingwark Loch near Castle Douglas around AD 100 which included a quantity of Roman military and Iron Age native metalwork.

In southern Scotland, forts and enclosed settlements were largely abandoned before the 1st Century AD, with ramparts and ditches no longer maintained, new houses built over former boundaries and some enclosed settlements abandoned altogether. This may have signalled an increased sense of security and the weakening of communities' individual identities in favour of broader, sub-regional social and political organisation.

Many of the roundhouse settlements recorded on the uplands could have been occupied throughout the 1st millennium BC and into the period of Roman presence in southern Scotland. There are a number of enclosures classified as 'forts' along the axis of the valley and several of them are scheduled monuments, but few have been dated. Prestige is likely to have been a major influence, besides defence, in the design of fortified farmsteads such as Rispain built between 100BC and AD200. This name is likely to have derived from the Cumbric Rhwospen, ‘the chief of the cultivated country’, a dialect closely related to Old Welsh. The superficial structures of these fortifications were mostly timber and have long since disappeared. Their earthworks, however, remain as legible forms in the landscape where they have not been destroyed by modern agriculture or development.

Roman Period A.D.80 - A.D.400

South-west Scotland was only formally encompassed within the frontiers of the Roman Empire for relatively brief periods in the late 1st and 2nd Centuries AD. Nevertheless, the Roman authorities would have maintained a keen interest in the region, given its proximity to the eventual final frontier of Roman Britain, delineated by Hadrian's Wall from the later 2nd Century.

The Roman Army probably first entered the south-west during the campaigns against the Brigantian tribe in the early 70s A.D. The Roman author Tacitus informs us that his father-in-law, the Roman governor and general of the province of Britannia, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, embarked on a series of campaigns to conquer the remainder of Britain, including a sea-borne invasion across the Solway in AD82. Agricola consolidated the Roman acquisition of the Lowlands by building forts on the Forth-Clyde line in 81 A.D.

The main western supply road to this frontier ran up through Annandale, whilst a western branch road ran to forts at Dalswinton, controlling the Nith crossing, and Glenlochar, controlling that of the Dee, and on west towards Loch Ryan. Southern Scotland was an occupied military zone at intervals over the next ninety years, and a more extensive road system was constructed to move troops around, including routes up most of the principal river valleys, and an eastern branch road from Annandale heading via Eskdalemuir to Trimontium, near Melrose. Several of these form the basis of roads and paths to this day.

Many Roman fortifications are only visible today from the air as crop markings, but good earthworks survive of the fort at Birrens, Middlebie and of the fortlet in the Durisdeer Pass, as well as the two Roman assault camps at Burnswark that may date to the Antonine re-conquest campaign of 140AD. There are numerous other examples of Roman forts, fortlets, towers and camps particularly up the river valleys of Nithsdale and Annandale and across Dumfriesshire. The military complex at Glenlochar serves as a strong representation of this change in the landscape, as an extensive palimpsest of the Roman occupations. It consists of the buried remains of three phases of fort with an annexe, a stretch of Roman road, a tower and up to eight camps, all visible through cropmarking recorded on aerial photographs and (in the case of the fort) as a level platform. Similar complexes of military occupation also mark the crossing points of the River Nith at Dalswinton and Drumlanrig.

No doubt cross-frontier social and economic contact continued and probably developed during the relatively peaceful 3rd Century AD, to the benefit of the local Iron Age communities, where Roman pottery, jewellery and metal goods were in use, and have been subsequently discovered when these sites have been excavated. Although the South-West was not Romanised in the same way as Britain south of Hadrian's Wall, nevertheless after their abandonment of Britain, elements of Roman culture survived in Galloway where, through the Christian Church, Latin remained in use.

Early History to Medieval Times

During the 6th and 7th Centuries, Dumfries and Galloway is thought to have formed part of the Brittonic Kingdom of Rheged which extended into modern day Cumbria. Christianity was well-established across much of southern Scotland by 450AD. Christian communities such as Whithorn and Kirkmadrine in Wigtownshire were centres for missionaries working in central Scotland and possibly in Ireland. Excavations at Whithorn, long associated with Scotland's first saint, Ninian, have revealed a large monastic site which during the 6th and 7th Centuries AD was wealthy enough to import wine and other luxury goods from Gaul and the Mediterranean. Similar evidence for trade with continental Europe has been found at the Mote of Mark near Dalbeattie, a small hill fort that was probably the court of one the princes of Rheged.

The Anglian kingdom of Northumbria extended its power over south-west Scotland from the 7th to 10th centuries. A small number of Anglian settlement placenames, suggests some settlement and linguistic change, but the extent of change seems rather limited and perhaps mostly within the higher echelons of society. Whithorn came within the diocese of York and Northumbrian silver coins were in circulation in the town. A major Anglian monastery was built at Hoddom in Dumfriesshire and a series of spectacular crosses carved in an Anglo-Saxon style were raised at Ruthwell (which carries an inscription in runes of a version of The Dream of the Rood – one of the oldest surviving Old English poems), Hoddom, Closeburn, Old Kirkconnel and at other church sites across the region.

Towards the end of the 9th Century, Galloway came under increasing Irish and Scandanavian (Hiberno-Norse) influence. The Irish Sea was the centre of a new political force based on cultural and trading links between Dublin, north-west England, the Isle of Man, the Western Isles and the Solway coast. Evidence of the extensive connections of the Norse maritime world can be seen in the artefacts uncovered in the Galloway Hoard, found in the Ken valley in 2014, although many of the artefacts are Anglian and may show the richness and cultural contacts of previous centuries. Coped gravestones in eastern Dumfriesshire are reminiscent of Norse hogsback gravetones. By the early 11th Century a town with characteristic Norse buildings was being built around the monastery of Whithorn. Galloway became a Norse earldom by 1100AD, with links to Ireland, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. A number of Norse placenames suggests that Scandinavians, probably from northern England, settled in Annandale and Eskdale. It was during this period that Gaelic replaced Brittonic as the main language in the west.

Strathnith, lay to the east of Galloway and formed was sandwiched between various expanding kingdoms, Northumbria, Strathclyde and Alba, the emerging kingdom of Scotland. By 1018 Scottish border stood at the River Nith. Galloway followed when it was invaded three times in 1160 by Malcom IV. The Lords of Galloway continued for another century as semi-independent rulers, actively engaged with politics and warfare in the Isle of Man and Ulster, with help from both English and Scottish kings.

In the 12th Century a major redistribution of power arrived with the Norman ruling class from the north of England being granted land by the Scottish kings as part of their attempts to contain and bring under control the unruly Galwegians west of the Nith. A multitude of motte and bailey timber castles and fortified moated sites were built by incoming Norman knights to control strategic locations and areas of landscape across Dumfries and Galloway and many of the earthworks are still standing and well preserved, such as Bruce’s Motte on the Annan and the Mote of Urr, which became a stronghold of the Balliols. Many mottes were a simple mound with surrounding ditch and a wooden tower erected on the mound top, but others had extensive baileys sheltering settlement and industry, and numerous sites were converted to the stone-built castles of subsequent centuries. However, there was much local resistance and Galloway remained effectively beyond the control of the Scottish monarchs until after the death of Alan of Galloway in 1235.

Although there is some early evidence for ecclesiastical territories these were adapted and formalised in 12th and 13th Centuries. The Parish network is still intact, though amalgamation has taken place. Through the medieval period the area became a significant destination for pilgrims to St Ninian’s Shrine at Whithorn. This meant that ideas and people from across Britain and beyond arrived in the area and the local economy benefitted along a number of well-trod pilgrim routes through the region. Chapels like St Ninian’s and Chapel Finian at Port William were built to benefit pilgrims to St Ninian’s Shrine.

Abbeys and priories were built across the region and illustrate the wealth and patronage of the aristocracy. Pre-eminent were the Cistercian abbeys of Dundrennan, Glenluce founded in the 12th century and Sweetheart founded in the later 13th century. Dulce Cor (Sweetheart) was founded by Lady Dervorguilla of Galloway to commemorate her late husband John Balliol. Its construction was hampered by damage during the war of Independence between Scotland and England in the late 13th and 14th Centuries and like the other religious houses in the region was substantially taken down after the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Happily, the shell of the abbey church remains towering over the adjacent village of New Abbey.

The turbulence experienced by the area during the later medieval period is also reflected in the castles throughout. Morton Castle, on the lower slopes of the Lowther Hills, is a complex hall house castle, probably constructed around 1300; the lake is artificial and made centuries later. The imposing tower of Threave Castle was built in 1369 and its inhabitants, the Black Douglases were thorns in the sides of the early Stewart kings, culminating in a major siege of the castle by James II in 1455. The Maxwell’s stronghold of Caerlaverock Castle was besieged by Edward I of England during the wars of Independence. Like Threave it was captured from a Royalist garrison and rendered defenceless in 1640 by a Covenanting army. This indicates the complications of politics at this time with loyalties shifting with each generation. Tower houses become the most dominant form of castle buildings over the middle ages. They were often built to a fashionable design but also built to be defensible. They stand proud of the landscape showing the power of the family who built them. Typical and publicly accessible examples can be found at Cardoness, Drumcoltran and Maclennan’s Castle, Kirkcudbright, are all good examples, but there are many others.

Tower houses gradually evolved to be comfortable family homes instead of fortresses as the area became more stable. Political stability and prosperity from the 17th Century onwards saw much of the gentry abandoning them in favour of more comfortable substantial country houses, many with gardens and designed landscapes which contrast in their exotic and designed forms from the surrounding agriculture. Some of the most significant country houses include: Drumlanrig Castle (Nithsdale), Galloway House (Wigtown), and Kirkdale House (Wigtown). Castle Kennedy is also important for its extensive designed landscape which provides the setting for its ruin.

The ‘Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland' includes and describes 20 designed landscapes within Dumfries and Galloway. In addition to the houses mentioned above, the following are included: Logan House/Logan Botanic Gardens (Wigtown), Lochryan (Wigtown), Ardwell House (Wigtown), Threave Gardens (Stewartry), Brooklands (Stewartry), Arbigland (Nithsdale), Dalswinton (Nithsdale), Raehills (Annandale and Eskdale) and Kinmount (Annandale and Eskdale). These landscapes have been assessed on their setting, the contribution that they make to the surrounding scenery, and on the various components of the landscape within its structure, as well as with reference to their historical value. There are also 168 regionally significant non-inventory designed landscapes, such as Corsewall near Kirkcolm, as well as numerous small-scale designed landscapes around prosperous 18th and 19th Century farmhouses. There are of course, many other elements of policy landscapes in Dumfries and Galloway. These may be of small scale or the legacy of more extensive estate control. Many lowland woods shelterbelts and tree avenues are attributable to estate influence during the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Growth of Towns – Trading, Agriculture and Industry

The early growth of towns in Dumfries and Galloway was largely a function of their role as defensible market centres for agricultural produce, often on the lowest fording point of rivers. The medieval town of Dumfries lay on the east bank of the River Nith. The river formed the border between Scotland and Galloway when the town developed. The separate burgh of Maxweltown on the western bank was only amalgamated with Dumfries in 1929. This is reflected in a cluster of mottes (earthen mounds for timber castles), two on the Dumfries bank and three on the Galloway side, reflecting the precarious state of a border zone.

Dumfries, “Queen of the South”, was a Royal Burgh by the late 12th Century and the absorption of Galloway into the Scottish kingdom after 1235 saw this status also given to the important trading centres of Kirkcudbright and Wigtown. The conferral of burgh status on a town was fundamental to its trading position, as only those living within the town walls had trading rights. Agricultural produce was the basis of this early economy, and also was the foundation for many historic industries which have grown out of traditional farming. The economy of Dumfries was very basic with cloth and wool as the main exports. It quickly grew into the major market town for the south west, particularly for cattle, and served as a collecting point on the old droving routes, reflected in a particularly large marketplace. 30,000 head of cattle are recorded as passing through Dumfries in a single day. Aside from local cattle, many passed through the region from Ulster, en route to markets in London.

By the early 19th Century, Dumfries had a large tanning industry associated with this central position. Although little is left of the medieval town, Dumfries has long been the main centre of this region. Most of the important buildings are of red sandstone. There is a predominance of red ashlar and white painted rubble or ashlar in Dumfries, Annan, Lockerbie and many other places, but also bare whinstone with ashlar and/or granite dressings and chimneys, as well as painted stone and lime rendered stone. In the centre of the town is the Midsteeple, completed in 1708 to provide a meeting place for the town council as well as a courtroom and prison. A plaque on the outer wall gives the distances to other towns and cities to which the people of Dumfries might have wanted to travel in the 18th Century.

The old red sandstone bridge, which dates back to the 15th Century, once provided an entrance with a toll house at the far end. Known as Devorguilla’s Bridge, it was here that the Lady Devorguilla de Balliol had the first bridge built, probably of timber, in the 13th Century. In former years ships were able to navigate the Nith, and it was the Dumfries merchants who built the lighthouse at Southerness in 1749. In the 18th and 19th centuries the quays downriver at Kingholm and Glencaple were still busy with ships trading to North America, the West Indies and the Baltic.

Harbours such as Portpatrick, Kirkcudbright, Isle of Whithorn and Garliestown linked the area with the Isle of Man, Ireland and further afield to the Americas, as well as housing ship building and fishing industries. The smaller harbours became obsolete with the introduction of steam vessels which required larger harbours and Stranraer became the principal port in the area until 2009 when the main port moved up Loch Ryan to Cairnryan. Stranraer is used by fishing vessels and leisure boats. Small scale fish catches are still landed at many of the historic harbours which are also attractive as mooring for yachts.

Agricultural improvement in the region pre-dated many other areas by 100 years. The early enclosures were by cattle-owning lairds of the 18th Century who have left their legacy in two distinctive forms of field boundary, the Galloway dyke and hedge. With improvement, more land was given over to oats, wheat and barley, and subsequently the brewing, distilling and milling industries advanced in their importance. New Abbey Corn Mill, dates from the 18th Century but replaced an abbey run mill here previously. Cloth manufacturing also became more significant at about this time. The sheep farming at Glenkens region, Upper Annandale and Eskdale supplied the factories when wool production became fully mechanised. In lower, lusher areas, dairying was the focus of production from the 1850s onwards. Arable related industry suffered from this shift in production, and many derelict grain mills are scattered across the Galloway landscape. By the mid-19th Century, Dumfries had become a thriving port.

Other historic industry within the region includes quarrying of stone for building, largely for local needs. Granite was used locally for setts but high quality granite and red sandstone were used in Glasgow and exported abroad. Granite exported from Dalbeattie went into the Mersey Docks in Liverpool, the Thames Embankment in London, it is significant in buildings in historical Boston, various British lighthouses, and was even exported as far as the lighthouse at the southern tip of Sri Lanka. Wanlockhead in the north had been the centre of Scottish lead and precious metal mining since the Middle Ages. The water powered beam pumping machine from 1870 is still visible. A fishing industry thrived along the Solway coast with Annan as a prosperous seaport until the 19th Century, smaller scale industry still perseveres.

Road and bridge building began in earnest here in the 17th Century and increased after the Turnpike Acts of the 1790s, which allowed tolls to be levied along roads to fund further road building programmes. Stretches of Roman and Medieval road can still be discerned in the landscape, and old droving roads are distinguished by their wide verges. The military roads, constructed in the 18th Century to counter the Jacobite threat, still form part of the modern road network.

The role of individual entrepreneurialism and planning is also evident in the landscape, with planned and semi-planned villages of the last two centuries being traditional features. Newton Stewart was the first planned village in the region, founded by William Stewart in 1677. Gatehouse of Fleet thrived as a cotton milling centre from the mid-18th to 19th Centuries, after which it declined. The industry had been established in the town by the local laird. Similarly, Garlieston was founded by the 7th Earl of Galloway as a fishing station and trading port.

Railways arrived in the region in 1845 and brought both prosperity and decline to the area. The trading function of ports such as Dumfries and Annan declined when rail transport arrived. For Annan, this signalled a significant blow to its shipbuilding industry of the 19th Century. However, the increased accessibility brought by railways created prosperity in many other towns. Moffat was a fashionable spa town in the 18th and 19th Centuries, but it was not until the railways arrived that it developed into a main tourist centre. Galloway as a whole lay comparatively unexplored by tourist traffic until the railway network was completed. Many of these railways are no longer operational, but their mark has been left in the landscape in viaducts such as the one over the Big Water of Fleet.

20th and 21st Century Developments

Agriculture

Agriculture has remained a dominant land use throughout the 20th Century, now accounting for over 73% of the land area of the region. The soil survey of Scotland identifies no class 1 or 2 land in the region, although localised pockets may be capable of producing a wide range of crops. Land class 3 (capable of producing a moderate range of crops) is found predominantly in lowland locations, for example, in the pastures around Castle Douglas, sheltered estuaries and along the main river valleys such as the Annan, Nith and Cree. Land class 4 is slightly more limited than the above and tends to be found as upland extensions of class 3. Much of the land area is suited only to improved grassland or rough grazing, (classes 5 and 6). Significant parts of the uplands face severe limitations for agriculture and are therefore only suited to rough grazing, although small pockets of land may be suited to limited improvements.

Agriculture in the region is skewed towards dairying and the rearing and breeding of beef cattle and sheep. The large majority of agricultural land is pasture or rough grazing. Very little land is given over exclusively to arable, although cereal crops are often grown on lowland farms in the course of a predominately grass rotation. Over 85% of the region’s land area is designated as a less favoured area due to severe limitations for agriculture. Nevertheless, the region accounts for about 30% of Scotland's dairy breeding herd and over 15.5% of sheep for breeding, since the mild wet climate produces some of the most productive grassland in Scotland. Much of the land up to about 200 metres is improved grassland, and so the sight of sheep and cattle grazing on fairly lush green pastures is a common one. Sheep are most common on rougher, higher pasture, with cattle on the lusher lower ground. Galloway cattle, particularly “Belties” are a distinctive sight in this landscape, with their broad white 'belts' standing out from their otherwise black form. They are only one of a number of interesting breeds of cattle within the Region.

The rougher, sheep-grazed pastures are characterised by stone wall boundaries, particularly in more exposed parts. These often give way to unenclosed rough pasture on plateau-like areas, there is also a small industry of salt marsh grazing sheep. Hedges and fences commonly enclose lower pastures, particularly in the valley and coastal areas where stone is not so readily available, but some walls are common on low ground in the Machars. Valleys, both narrow and wide, tend to have a pastoral feel, with grazing on lush pasture in the valley floor.

In recent years the Agri-Environment Climate Scheme has promoted land management practices which protect and enhance Scotland’s magnificent natural heritage, improve water quality and public access, manage flood risk and mitigate and adapt to climate change through payments supporting these practices.

The pastoral landscape of Dumfries and Galloway is delineated by several types of field boundary: walls, hedgerows, hedgerow trees, banks and combinations of these. These are essential characteristic features which express the local geology, highlight topographic relief, create skyline silhouettes, separate patterns and colours of cultivation and define visual boundaries. Two particularly distinct boundary types are the Galloway Dyke and the Galloway Hedge, developed locally but influential in the design of enclosures for other British pastoral landscapes. The Galloway Dyke is constructed with a double stone base and topped with large single stones showing light through the gaps. This construction is ideal for the granite landscapes where the local stone is found in a boulder form and is extremely difficult to split by hand. The Galloway Hedge is a combination of wall and hedge (usually hawthorn) where the hedge is layered through the wall ultimately growing to form the top half of the boundary.

In areas where hedgerows are the dominant enclosures, these too vary, between hawthorn and beech. Hawthorn is generally found on poorer soils, or exposed areas, especially near the coast, and beech in more sheltered parts. The very presence of beech hedges reinforces a sheltered appearance. Preference of individual landowners would also appear to play some role - in Annandale, for example, beech avenues and hedgerows are particularly striking. The decline of hedgerows and hedgerow trees has not had a reprieve and gaps in mature tree lines and post and wire fence replacements are becoming commonplace. In the narrow intimate valleys, enclosures are often more densely treed with mixtures of sycamore, ash, Oak and beech. Elsewhere sycamore tends to dominate as the hedgerow tree.

Farm buildings are important features of the landscape. These include not only the occupied, but also the redundant buildings which no longer serve contemporary requirements. Their existence is important to visual diversity, and represents the cultural history of the farmlands. This includes the remnants of earlier agricultural settlement e.g. shielings and sheep folds which are often the only visible structures in upland areas.

Forestry and Woodland

Forest and woodlands constitute a major element in the landscape of Dumfries and Galloway. In total about 35% of the region's land cover is classified as forest or woodland, and within this category fall a variety of woodland types reflecting a variety of purposes and management regimes. Much afforestation, primarily coniferous, was undertaken by the Forestry Commission (now Forestry and Land Scotland) and later by private forest companies, so that approximately one quarter of the region's land surface area is now forested.

The area of native woodland is just under 10% of the total woodland area with wet woodland, upland birch woods and lowland mixed deciduous woodland comprising the majority, but upland ash and oak woods are also significant. Much of this woodland follows the river valleys although there are copses of woodland, especially in lower lands. Invasive Rhododendron and over invasive exotics affect about 2.4% of this. Chalara, ash dieback infection, has been widespread in Dumfries and Galloway, which could significantly affect the native woodland in the area. Much of the semi natural woodland is in the form of wood pastures, shelter belts and hedgerows.

The Solway Coast, including the Rhins Peninsula, Machars Peninsula and lower Annandale, fall within the lowland zone of semi-natural woodland with associated species of lowland mixed broadleaved woodland, wet woodlands and acid oakwoods. These remnant areas of ancient and semi natural woodland are valuable particularly from a nature conservation view in terms of their intrinsic value and associated wildlife which they support. From a landscape point of view they add diversity and often intimacy. Pockets of long-established semi-natural woodland can be found throughout the Region, as can long established plantation woodland. These ancient and semi-natural woodlands are often associated with large houses or castles as areas of land have been designed and laid out primarily for ornamental reasons, Aldouran Glen and Castramon Wood are semi natural with evidence of planting as well as significant native woodland. Trees have formed an important element in these policy landscapes, with large deciduous trees amongst pasture creating a parkland atmosphere, and ornamental conifers standing proud from manicured lawns or adding diversity to policy plantations. These trees create an impressive yet often intimate landscape and have also provided practical benefit of shelter. Some estates such as Drumlanrig in Nithsdale have also managed their woodland for commercial purposes using mainly conifers but also some broadleaf/hardwood production.

Woodlands are a feature of agricultural landscapes in the region. Primarily used for shelter, belts of trees line field boundaries across the area and are particularly significant in the landscape near the coast or in exposed upland landscapes. These shelter belts tend to be of mixed woodland. Land use policy encourages more planting to help combat climate change and other aims.

Trees are a feature of many valley landscapes, where they often form a riparian fringe to the water course, picking out the river. These are most often of deciduous species and create intimate pockets within wilder landscapes. Hedgerow trees line some roadsides for example in the Stranraer Basin and Annandale.

The Forestry Commission was established in 1919 to create and manage state forests, predominantly for strategic and economic reasons. In the late 1920s and early 30's, substantial areas of agricultural land were sold to the Forestry Commission to establish the first state forests in the Dumfries and Galloway Region, at Kirroughtree, Berman, Fleet and Ae. At the time, economic and agricultural depression was sweeping the country and this new drive for forestry was welcomed by many as a means of diversifying the rural economy. The transfer of land from agriculture to forestry met few constraints.

With the onset of war in 1939, forest expansion halted and timber reserves were quickly depleted. By the mid-40s a planting target had been set by the Forestry Commission of 2 million hectares of productive British woodland by the end of the century. Assistance to private owners to manage their woodlands and establish new forest was greatly expanded to achieve this end, in some cases destroying upland archaeology through ploughing and planting. In addition, greater availability of hill land for planting facilitated the Government's wish to increase areas under forest. This less productive hill land was deemed suitable because its transferral to forestry would have the least impact on agricultural efficiency. Much of this type of land was in Scotland, south-west Scotland in particular, which effectively earmarked Dumfries and Galloway as an important area for forest expansion.

The social and economic role of upland forests to these communities became the main rationale behind the continuation of these policies into the 1950s and 1960s. Planting programmes became policy targets to be achieved annually to maintain employment levels and distinctive post war forest villages such as Glentrool and Ae were created. The expansion of forestry therefore continued to receive general public support, and indeed had sought to cater for public leisure needs in some locations with the creation of the Galloway Forest Park.

The 1970s saw a number of developments in policy which influenced the nature of forestry in the region. Entry to the European Union strengthened the position of hill farming so that land available for planting was limited to the very least productive. Landscape concerns over monoculture forestry became more vociferous, as did the debate about the general lack of access provision where forestry blocked walkers' advance into the hills. The Forestry Commission incorporated more recreational facilities into its forests as a result, as did some private estates in the region. A landscape design approach to planting and felling was also adopted. In 1972 a governmental review of forestry questioned the profitability of the forests and highlighted the very low rate of return. A reduction in the Commission's planting programme was announced and planting rates in the private sector also slumped. The evolution of forestry, and the Commission's response to many of the issues raised throughout its lifetime has led to its present status as a generally multi-purpose resource, although timber production remains the prime objective for vast areas of forest.

In the last 35 years care has been taken to acknowledge landscape concerns in planting and felling, with more sensitive edge treatments, and with clear fell and new planting having greater regard to natural contours. There is also a handful of large forests owned by private forestry interests. Carsphairn Forest and parts of Eskdalemuir are examples of this.

In 2019 the Forestry Commission in Scotland was reorganised into Scottish Forestry and Forestry and Land Scotland; the former is the governing body for all forest management in Scotland and the latter manages the state-owned forests. A modern feature of Forestry and Land Scotland forests has been the provision of recreation facilities such as picnic clearings, car parks, toilets and waymarked trails. Most notably this is a feature of the Galloway Forest Park which, while still managed for timber production, is highly sensitive in its management to landscape issues, particularly in the most popular tourist parts. Mabie and Dalbeattie Forests are examples of smaller scale local recreational forests. There is also substantial native and mixed woodland planting, this is a trend that is likely to continue as current government targets for tree planting are ambitious.

Industry and Infrastructure

Industry and infrastructure has had an impact on the landscape since humans first settled on the land and has evolved alongside human development. Roads have become wider, and sealed, the railway grew and then declined, and energy and communication infrastructure of the 20th and 21st Centuries has become more widespread.

Important features are the remnants of the following industries: road and rail communication, sea trade and milling. Military heritage is particularly significant in certain parts of the region. Features include, for example, remains of huge 1st World War munitions workings along the Annandale coast at Powfoot, now an active quarry, fish farm and caravan site, and Gretna, the latter stretching over the English-Scottish border. In the 2nd World War there were munitions plants and magazines at Edingham outside Dalbeattie, and many other 2nd World War military facilities around Loch Ryan. The military port infrastructure at Cairnyran has now mostly been removed through the construction of the new ferry terminal.

In the later part of the 20th Century communication masts, initially for radio and television, and latterly for mobile phone networks, became visible on many hilltops and are evident in views south across the Solway into Cumbria. It is likely that there are few new areas for masts to be installed, although potential improvements in technology may mean that the number and size may decrease.

Energy network infrastructure has expanded throughout Scotland. Overhead power lines are visible manifestation of these developments. Prior to its decommissioning, pylons converging on the nuclear power station at Chapelcross near Annan, were particularly noticeable, but the increase in renewable schemes means that there is an increased requirement for more or larger pylons elsewhere in the region. The region is also traversed by many underground pipelines for water and gas supply and for sewage, which are less intrusive and only noticeable by intermittent above-ground service hatches and buildings. Underground electricity cabling is less extensive and employed mostly in proximity to urban areas.

A logical extension to the agricultural industries of dairying, corn milling and sheep rearing, was the development of a textile industry using the available water power and natural materials. This industry once boomed in the region causing the development of textile mills in several towns, for example Dalbeattie and Annan, but with concentrations at Gatehouse of Fleet and Dumfries. Mill buildings are, therefore, regular features in the landscape, as part of farmsteads and as industrial complexes now defunct.

Renewable Energy

Hydroelectric schemes constructed in the 1930s are still very evident in the landscape today. The Galloway scheme is one of the oldest in Scotland and contains six generating sites. The infrastructure associated with them is distinctive and in some cases protected. The Art Deco styled Tongland power station near Kirkcudbright is a particularly striking example.

The development of renewable energy is limited in certain areas due to natural heritage considerations but the area has some of the highest output in Scotland. There is one off-shore wind development in the Solway Firth: Robin Rigg (180MW). There are sixteen onshore wind farms are currently operational: predominately in upland areas. Groupings of wind farms and/or turbines can be found in the Luce Valley and moorland to the east; in the uplands between Carsphairn and Sanquhar; in the moorland and hills between Carsphairn and Moniaive; in the Forest of Ae, and in the hills east of Langholm. New proposals continue to be brought forward and more modern turbines are significantly taller, up to 220m in some developments. There is also a 40MW biomass plant at Lockerbie.

Smaller in impact, but still noticeable in the built environment, there are almost 2700 domestic solar installations in the area. There is potential that larger commercial solar farms may be built in the future.

Transport

Much of Dumfries and Galloway’s role in history has stemmed from its geography and connection to other places. On the fringes of the Roman Empire, active within the Irish Sea zone, and later as the Debateable Lands on the English - Scottish border, it has not only been the site of many border disputes but also a place where ideas and innovations came from the movement through the area, by land and sea. Prior to the development of the modern road and railway network, the Solway and Irish Sea would have offered the best means of trade and communication.

The determination to develop sea-trade led to the construction of harbours and lighthouses around the coast of Dumfries and Galloway. In some cases their use has now waned, for example at Port Logan, Drummore and Wigtown. Rough Firth (Kippford) and Auchencairn Bay may have historically been used as sheltered harbours. Others remain thriving such as Kirkcudbright which has recently had improvements made to fishing and recreational boat moorings. The infrastructure of ports, both prosperous and those in decline, remain as characteristic features of the region's coasts and estuaries. Southerness Lighthouse is one of the earliest in Scotland. Scallops and lobsters from fishing in Irish Sea are still landed at Isle of Whithorn and trawlers operate out of Port William, Portpatrick, Garlieston and Stranraer.

Disused railway viaducts such as Glenluce and Goldilea, are powerful reminders of the once dominance of railway communication. Earlier road bridge structures in masonry and cast iron remain in use, and are key features across the region's rivers.

Dumfries and Galloway is traversed by several trunk roads (A74/M74, A75 and A76) which generally follow lowland and valley routes through the region. These have been subject to varying scales of engineering upgrades. The M74 through Annandale has been the subject of major works over many years. The A75, as the main east-west link between Carlisle (M6) and Stranraer has also been significantly improved in the form of bypasses for Dumfries, Annan, Castle Douglas and Gatehouse of Fleet, as well as localised improvements. On the other principal roads, particularly the Regional Strategic Road Network, engineering works have generally addressed bottle-necks, and slow and dangerous sections of road. The minor road network has been subject to a programme of engineering works designed to accommodate the pressures of forestry haulage and the statutory need to upgrade bridges to carry heavy goods vehicles. This has necessitated the strengthening or replacement of minor bridges and local adjustments to road alignments and widths. Road building programmes have created the demand for both hard rock and aggregates which are quarried within Dumfries and Galloway.

Rail travel is now limited in the area, with a branch line from Glasgow to Dumfries which connects to the west coast main line at Carlisle. The West coast mainline travels north-south in the east of the region, although currently the only station is at Lockerbie. Additionally there is a coastal line to Stranraer from the north, linking the ferry terminal for Northern Ireland, now at Cairnryan, with Glasgow. There is potential for the reopening of disused lines as part of reducing the reliance on road transport, but no progress has be made to date.

Mineral Extraction

The grey granites of Stewartry and the red sandstones of Lower Annandale and Nithsdale were prized for a range of engineering and building projects at the end of the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Granite is still quarried: at Dalbeattie and New Red Sandstone at Locharbriggs. Disused commercial quarries remain, now weathered and partially overgrown.

The geology of Dumfries and Galloway has yielded a wealth of minerals and fossil fuels that have been worked for generations. Metals and semiprecious minerals were formed within areas of metamorphic influence close to granite intrusions. In Upper Nithsdale the presence of carboniferous geology supported coal mining for a period, as was the case around Rowanburn near Canonbie, but that has ceased and the sites mostly restored. Evidence suggests activity of this nature stretched back to the earliest metal working communities. The most intensive mining was undertaken for lead at Wanlockhead (and Leadhills) and Carsphairn, and for coal at Sanquhar and Kirkconnel. The latter employed as many as 2,000 in 1925.

The legacy of small-scale mining is often difficult to detect in today's landscape. Most noticeable perhaps are the distinctive settlements that have developed because of mining. The local effects of lead and coal mining are, however, significant features in the landscape, especially if not restored. The large opencast site at Kirkconnel in Upper Nithsdale for example, which went bankrupt in the early 2000s and has not been reinstated, is still highly visible. Close by are the spoil and slag heaps which appear raw against the green hillsides. Lead mining also resulted in many associated features in the landscape: silting lagoons, smelting chimneys and water channels. The importance of this industrial heritage has been recognised in recent years with the development of a lead mining museum at Wanlockhead and the designation of the Woodhead mining village as a Scheduled Monument, along with the mines at Pibble Hill near Creetown. The Wanlockhead mining complex is the largest Scheduled Monument in Dumfries and Galloway.

The legacy of coal mining in the form of bings, for example at Sanquhar, are unglamorous but interesting reminders of the settlement's reason for being there. Sand, greywacke and gravel extraction continues to be carried out within the region, largely for building and improvement works, such as the greywacke Barlockhart Quarry near Glenluce.

The Built Environment