Landscape Character Assessment: Ayrshire - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The PDF version of this document can be found at the foot of the webpage

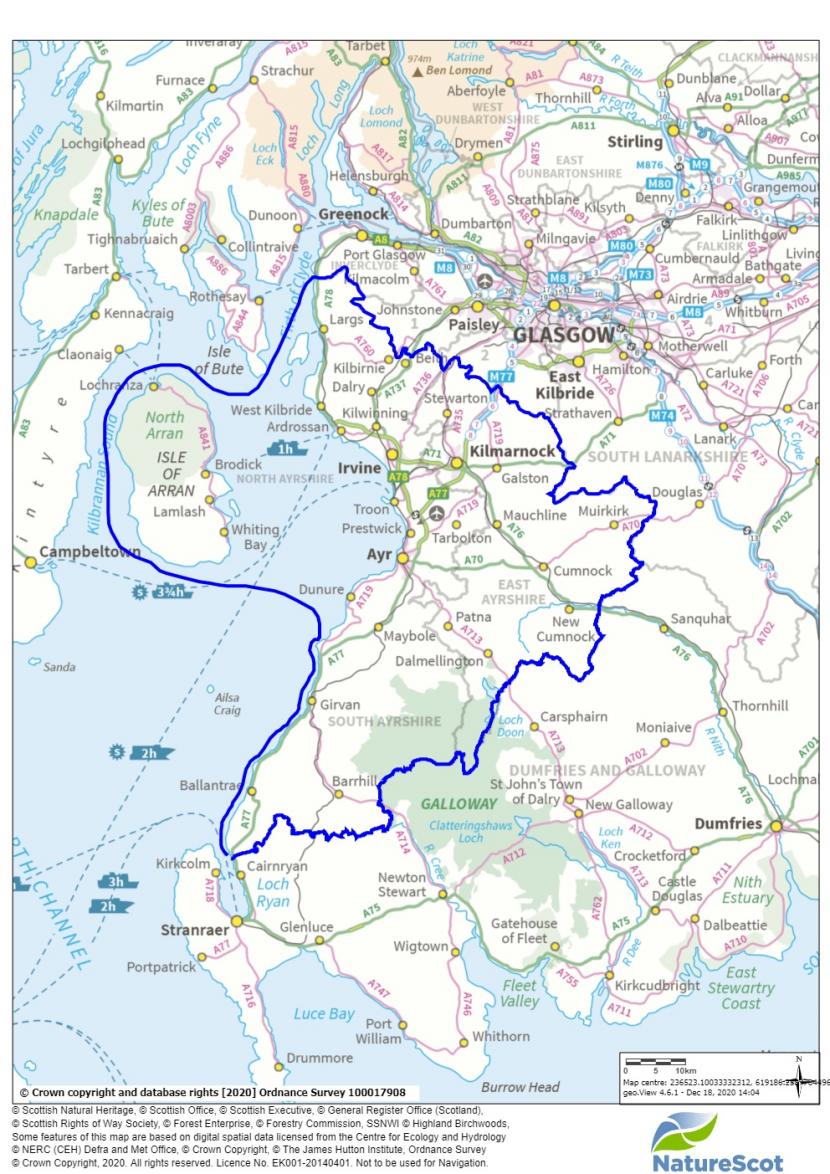

This document provides information on how the landscape of Ayrshire area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten,

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot website. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of;

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot/

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in “Nature Scot Review 111: Ayrshire Landscape Character Assessment” 1998, Land Use Consultants.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION/OVERVIEW

Ayrshire encompasses a wide variety of landscapes, ranging from the rich pastoral lowlands of the Ayr Basin, through expansive plateau moorlands, to dramatic upland summits such as those found in the northern part of Arran. It is predominantly a lowland region lacking the large-scale rugged grandeur of the northern Highlands. It does, nevertheless, have local areas and features of strong relief which provide dramatic and scenic contrasts to gentler topography of the surrounding areas. The smallest of these are the distinctive remains of volcanic plugs which constitute Loudoun Hill, Ailsa Craig, the Heads of Ayr and Knockdolian.

On a grander scale are the rugged glaciated peaks of Arran and the Loch Doon Mountains, with their corries, u-shaped valleys, hanging valleys and frost shattered ridges. Less rugged, but nevertheless powerful geomorphological features, are the smooth glacially carved valleys of the Southern Uplands as typified by the Nick of the Balloch.

Ayrshire's coastline of raised beaches is equally distinctive and impressive, particularly where the former cliffs rise to great height behind the flat fertile terrace of the raised beach.

Several islands lie within the area. These include barely habited islands such as Little Cumbrae, Holy Island, and Ailsa Craig to the larger islands of Great Cumbrae and Arran. In addition to comprising important landscapes in their own right, these islands make a significant contribution to views across the Firth of Clyde from the mainland. Ailsa Craig, for example, is often visible as a steep-sided silhouette, while on a clear day, the mountains of north Arran soar dramatically above the surrounding islands and coastline.

The variation in landscape character reflects closely the area's geological structure, a factor which has had a determining influence on landform, vegetation patterns and, equally significantly, the distribution of human settlement and land use.

Most of Ayrshire’s main towns are along the coast, from Largs in the north, to Irvine, Troon, Prestwick, Ayr and Girvan, reflecting the strategic importance of the coast for the fishing industry and the movement of goods. Hunterston port in north Ayrshire was constructed in the 1970s to import iron ore to supply Ravenscraig steelworks in Motherwell. Kilmarnock, situated inland on the River Irvine is the largest town in East Ayrshire. Johnnie Walker whisky had been part of the town’s industry for 189 years when it closed in 1989. East Ayrshire was the heart of Ayrshire’s coalmining industry which developed during the 19th Century. Killoch Colliery near Ochiltree and Barony Colliery near Auchinleck were among the last coalmines to close in Scotland – both closed in 1989.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Geology

The majority of Ayrshire lies within the Midland Valley of Scotland, the broad belt of comparatively low land (rift valley) which is bounded by the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and the Southern Upland Fault to the south. The alignment of these faults is approximately south-west to north-east. Ayrshire occupies the entire western seaboard of the Midland Valley and extends beyond the Southern Upland Fault to encompass parts of the Southern Uplands along the boundary with Galloway. All of Ayrshire lies to the south of the Highland Boundary Fault with the exception of Arran which is bisected by the fault.

The Southern Upland Fault runs from south-west to north-east across central and southern Scotland, marking the transition from the upland hills which characterise much of Dumfries and Galloway, and the Midland Valley to the north. The Fault runs across the southern part of Ayrshire where it has influenced the alignment of river valleys such as the Girvan and the Stinchar, together with the orientation of the foothills, moorlands and ridges between them. To the south of the Fault lie bold uplands, modified significantly by glacial erosion, creating smoothly rounded hills and plunging u-shaped valleys. The rugged granite summits of the Merrick Range extend into the south-east corner of Ayrshire, around Loch Doon. These are amongst the most remote and unsettled parts of Ayrshire. Commercial forests clothe large areas of the uplands.

To the north of the Southern Upland Fault, the landscape is lower and less complex, comprising an extensive basin focused on the coastal town of Ayr, and enclosed by a semi-circle of plateau moorlands and foothills which mark the watershed between Ayrshire and the Clyde and Lanark basins. Although areas of arable cultivation are found on better land along the coast, it is pastoral farming which characterises much of the basin. The area retains a dense network of hedges, hedgerow trees and small fields. Stone farmhouses crown low hills in the undulating basin. In combination, these characteristics create a pastoral landscape which is more intact than many of the parts of England with which Ayrshire is often compared.

Post-glacial land and sea level changes created the raised beach complexes which are found along much of the Ayrshire coast. Usually, this landscape comprises a gently sloping terrace a few metres above the high water mark (representing the former beach) together with a steep escarpment representing the former cliffline. In many cases, these clifflines support rich broadleaf woodland, the canopy shaped by the force of prevailing winds. While these raised beach landscapes characterise those areas where the uplands reach the coast, within the lowland basin the coast is characterised by extensive dune systems, punctuated by more resistant rock headlands such as that at Troon. Much of the dune coast has been 'reclaimed' to provide land for urban expansion around towns such as Ayr, Prestwick and Troon. Other areas have been transformed into golf-courses or other recreation areas. Few areas of natural dune remain.

To the north of the Highland Boundary Fault, the geology comprises resistant metamorphic rocks of the Dalradian Complex. These generally include Quartz-mica schists, slates and phyllites with many igneous intrusions typically of granite, basalt and dolerite. Only the northern half of Arran has these constituents, the effects of which are discussed below.

To the south of the Southern Upland Fault, the geology comprises ancient (Palaeozoic Ordovician) sedimentary formations which generally include greywackes, shales and mudstones. These rocks, generally of dark grey and brown hues, are fairly resistant to denudation, and as a result form extensive ranges of rounded hills and plateaux between 300 and 800 metres.

These Ordovician rocks are disrupted by many igneous intrusions which include porphyritic and rhyolitic dykes and granite batholiths (very large igneous intrusions extending to an unknown depth in the earth's crust). The most significant is the Loch Doon granite intrusion which has determined the formation of southern Ayrshire's most dramatic mountain landscapes. This massive intrusion initially pushed its ‘roof’ of sedimentary rocks into a dome, the top of which was subsequently eroded leaving a central ridge of hard white granite (Mullwharcar, Hoodens Hill, and Craigmawhannal) surrounded by a rim of extremely resistant metamorphosed sedimentary rocks. The latter now represent the highest mountains and ridges, e.g. Kirriereoch Hill (786 metres); Tarfessock (697 metres); Shalloch on Minnoch (768 metres), and Gaiglee (523 metres). The central granite ridge is flanked by tonalite granite which has a higher proportion of plagioclase feldspar and is consequently less resistant to erosion. This differential has created a corridor on lower ground occupied by rivers and lochs, including Gala Lane, Carrick Lane, Loch Riecawr and Loch Macaterick.

The Southern Upland Fault passes to the north of Loch Doon, separating, as the name suggests, high plateaux and hills to the south and lower undulating landforms to the north. The Southern Upland Fault is defined by a number of distinct topographic features, including the dramatic clefts of Glen App, Glen Dunnack, the upper section of Glen Tig, Glen Muck and the Howe of Laggan; and the hill ridges of Penderry Hill, Carlock Hill, Milljoan Hill and Benevaird, and from Greensides to Pinbreck Hill. These features establish a strong visual axis across the country.

To the north of the Southern Upland Fault, the area was subject to widespread parallel faulting and volcanic activity, which further complicated geological formations. However, the general patterns follow a south-west orientation parallel to the main faults. The Stinchar Valley Fault follows this orientation and provides a pronounced geological boundary between Ordovician greywackes, siltstones and mudstones of the Tappins Group to the north, and the Ordovician greywackes with thin siltstones and shales to the south. This fault determines the alignment of the Stinchar Valley and the characteristics of its side slopes.

Volcanic activity in southern Ayrshire, as elsewhere in the region, has created a number of distinct topographic features determined by their resistance to denudation. The island of Ailsa Craig and the distinctive conical hills Knockdolian and Loudoun Hill in East Ayrshire are the remains of volcanic plugs. The combination of intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks between Ballantrae and Girvan has also determined the presence of craggy coastal uplands with steep cliff or raised beach bluff slopes.

The majority of Ayrshire is within the western region of the Midland Valley of Scotland. The latter has formed a depository for sedimentary rocks since early Palaeozoic times. Subsequent folding, faulting and igneous activity within the Midland Valley created a complex geological pattern of synclines and eroded anticlines with local intrusions and extrusive coverings of igneous rocks.

The western region of the Midland Valley comprises two carboniferous basins: the Ayrshire and Lanarkshire Basins. These basins represent two major downfolds separated by a ridge of hills which are the remnants of an eroded upfold capped by resistant carboniferous lavas (basalt and spilite). This ridge of hills and heathy plateaux extends south-east from the Wemyss Bay - Gourock headland to between Darvel and Strathaven, from where it becomes disrupted by parallel faulting close to the Southern Upland Fault. Old Red Sandstone underlies the lava cap but re-emerges in the south as a discontinuous band running roughly parallel with the Southern Upland Fault. The basalt covered ridge of hills effectively defines Ayrshire's north eastern and eastern rim and determines that the general incline of the region is towards the western seaboard. The disrupted Old Red Sandstone hills in the south serve to close the basin and create its roughly horse-shoe shape.

A large proportion of central Ayrshire is underlain by coal measures (Ayrshire Coalfield) which contain productive coal seams and ironstones at various depths.

The shallowest (most accessible) coals are around the edge of the Ayrshire Basin, bordering and underlying the eastern hill range. These were easily extracted and quickly worked out by stoop and room methods in the 19th and early 20th Centuries.

Ayrshire's deep coals are located in the centre of the basin to the east of Ayr, about 600 metres beneath thick layers of Barren Red Measures, Permian sandstones and lavas. These are harder to extract and as a result they remained undisturbed until later deep mining technology made their extraction viable.

The newest rocks in the centre of the basin are Permian New Red Sandstone found to the west and south west of Mauchline, covering the low plateau known as Kyle. As in Dumfries and Galloway, this stone is prized for its building qualities. The distinctive New Red Sandstone was used widely throughout Ayrshire and is a dominant characteristic of many towns.

Vulcanicity throughout the Midland Valley caused the introduction of intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks including granites, basalts, dolerites and rhyolites. As already mentioned the eastern rim of the Ayrshire Basin was capped by carboniferous basalt and spilite; the basin itself was mostly affected by local intrusions of basalt and dolerite. The low coastline is punctuated by dolerite sills which form the headlands of Prestwick, Troon and Saltcoats. Inland, these igneous rocks form locally prominent hills such as those between Troon and Dundonald, and the hills north of Dalmellington and Waterside (e.g. Benquahat Hill).

The most dramatic and complex igneous features are, however, found in Arran where the remains of a massive granite pluton dominates the northern half of the island (and the Firth of Clyde). The Arran Granite is the second largest Tertiary Granite outcrop in the UK. It comprises two types of granite: its outer part is coarse-grained and extremely resistant to erosion, its centre is softer fine-grained granite. The result has been differential erosion leaving sharper higher peaks around the east and west margins (e.g. Cir Mhor and Beinn Bharrain) with a low central trough (Glen lorsa) flanked by lower rounded mountains.

The Arran Granite intruded within the Dalradian schists to the north of the Highland Boundary Fault. In so doing, it caused a south-eastern deformation of the fault line into an arc around the northern part of Arran. The granite intrusion is, therefore, fringed by Dalradian schists to the north, south and west, but also has a mixture of displaced sedimentary rocks to its north and east. This narrow coastal margin has been influenced by the isostatic adjustment of Arran, whereby raised beaches were formed over the underlying metamorphic and sedimentary rocks.

The north-eastern fringe of Arran comprises the displaced sedimentary rocks below the Highland Boundary Fault (which is defined by the North Glen Sannox and Glen Chalmadale valleys). These include Carboniferous and Permian rocks which are tilted to form a rampart of cliffs known as the Cock of Arran. These contain coal measures which were mined for a period to provide local fuel for the island.

The southern half of Arran is an undulating plateau around which is at a height of around 500 metres, dipping generally towards the south-west and to its shores. It is underlain by predominantly New Red Sandstone with numerous igneous intrusions which create local ruggedness. Igneous sills from the Tertiary period have left sheets of resistant rock between beds of sedimentary rocks. Their relative resistance to denudation has left cliffs, scarps and terraces. These include the cliffs at Drumadoon Point, Brown Head and Bennan Head and the scarps in south east Arran at Cnoc na Garbad, the waterfall steps of Glenashdale and Auchenhew Hill. Arran contains many other complex geological features which contribute to the local character. These include a 'ring complex' in the centre of Arran where igneous intrusions within a 'caldera' remain as irregular peaks around Glen Craigag, e.g. Ard Bheinn and Creag Dubh. Igneous dykes (vertical sheets of granite and gabbro) are also visible along the south shore of Arran, and Holy Island represents part of a 'ring dyke' of riebeckite-trachyte which itself is part of a cone sheet complex centred on Lamlash Bay.

Glaciation

During the Pleistocene period, the Loch Doon highland massif operated as a major ice centre from which glaciers and ice sheets flowed to north and south. A breach in the metamorphosed rim allowed the glacial over-deepening of the Loch Doon Valley as ice moved northwards. Local ice erosion and frost shattering also left rugged peaks, cliffs and jagged ridgelines in the area. Dramatic evidence of glacial erosion can be found in proximity to the Southern Upland Boundary Fault where glacier ice has eroded carries and u-shaped valleys. The Nick of the Balloch and the corries between Glengap, Haggis and Rowantree Hills are fine examples of this geomorphological feature.

Several of the rivers show evidence of over-deepening as a result of isostatic adjustment after the release of ice pressure in post-glacial times. The incised lower valleys of the Rivers Ayr, lrvine and Doon best illustrate this effect. Ayrshire's raised beach coastline is also testament to the relative changes in land and sea levels. Where the hinterland is composed of higher, more resistant rocks, the once towering sea cliffs now rise as steep bluff slopes behind raised beach terraces of varying widths. These raised beaches have provided valuable light soils for cultivation and enabled the construction of coastal towns, villages and communication routes.

The present rugged character of Arran’s granite massif is largely due to the processes of glaciation. Arran was covered by ice sheets on several occasions and was a local centre for ice movement. This resulted in the glacial carving of softer rocks, existing valleys and lines of weakness, accompanied by the frost shattering of high exposed rocks and the deposition of eroded material in lower areas. The products of glaciation include u-shaped valleys, hanging side valleys, carries, corrie ridges and the horns of summits.

Glacial and inter-glacial deposition left moraines on the lower ground, particularly in the main glens where they are local features or provide areas capable of cultivation. Raised beaches extend around the southern half of Arran and support the most productive farming

Hydrology

The drainage patterns reflect geology with the main rivers converging towards the low coastline between Saltcoats and Ayr. These include the River Garnock and tributaries, Annick Water, Fenwick Water, the River lrvine and the River Ayr. In the south of Ayrshire, river valley systems have been more significantly affected by faulting, and by glaciation. The upper reaches of the River Doon and the Water of Girvan valleys in particular have been carved by ice from the Southern Uplands.

In their upper reaches, the rivers Gourock, lrvine, Ayr, Glenmuir, Nith and Troon have cut sizeable valleys into the surrounding rim of hills. These valleys became a focus for communication routes, settlement and industrial development, the latter based on the exploitation of water power for textiles and mineral deposits for the coal, iron and steel industries. In their lower reaches, these rivers flow through narrower, often incised valleys cut into the floor of the Ayrshire basin, again acting as a magnet for settlement.

There are few large lochs within Ayrshire, the largest is Loch Doon which has been enlarged, Loch Bradan nearby is also a reservoir. Other lochs are small and mostly remain from the last glacial period. They characteristically have marshy edges and are good habitats for birds.

Soils

Inland lowland soils in Ayrshire are predominantly mineral gleys, along the coast soils on the New Red Sandstone are more productive, particularly in the areas of lower gentle relief. The igneous rocks, on the other hand, have generally thin, often rocky acid soils which support moorland habitats.

In higher areas, especially near Loch Doon, peat and peaty podzols are more common. This is also reflected in Arran. There are also limited areas of low-level peat and peat-rich soils closer to the coast. Both Arran and the Loch Doon area have limited areas of immature upland soils, mainly granite-derived which are capable of maintaining alpine species otherwise rare in this area.

Alluvial sediments can be found in the flood plains of the rivers. These are some of the most fertile soils in the area.

The raised beaches provide a narrow but important fringe of habitable land around the northern coast of Arran. Above this fringe, the slopes generally rise steeply and have thin acid soils only capable of supporting rough grazing and some forestry. The more extensive cultivable soils in southern Arran encouraged large scale agricultural improvements during the 18th and 19th Centuries. As a result, there is a greater regularity of field and settlement patterns in southern Arran. The agricultural limitations of northern Arran have determined that few wide scale agricultural improvements were implemented during the 18th \19th Centuries and, consequently, the remnants of ancient patterns of settlement and land tenure can still be seen.

The lowland and coastal areas of Ayrshire show good capacity for agriculture and are capable of maintaining a variety of crops, traditionally cereals and potatoes were common. Further inland this capacity declines, initially suitable for improved grazing, especially dairy, and higher ground becomes more suitable for rough grazing and forestry.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

Historic Landuse

The landscapes of Britain have been inhabited since soon after the retreat of the last ice sheets around 10,000 years ago. Humans have, therefore, utilised and manipulated the landscape and its physical resources for several millennia. The results of this activity are now essential characteristics of the landscape. The following summarises how humans have influenced the physical landscape of Ayrshire.

Mesolithic Period (7,000 - 4,000 BC)

In Mesolithic times, it is believed that the majority of Ayrshire was covered in woodland and scrub communities, with areas of open moor and grassland on higher areas. Into this landscape arrived migrations of people travelling up the west coast by the use of small craft. These nomadic people were reliant on fishing and hunting and established only temporary settlements on the raised beaches, leaving relics in the form of small flint tools and middens as at the mouth of the Stinchar near Ballantrae, and at Shewalton and Ardeer. Evidence of human activity inland is scarcer; however, a number of sites are known around the shores of Loch Doon. It is likely that hunting expeditions inland took place. The paucity of Mesolithic human remains in the area would suggest that treatment of the dead was perhaps less formalised or monumental than in later periods.

Neolithic Period (4,000 - 2,500 BC)

Around 6,000 years ago, there was a move from dependence on hunting to a mix of hunting and farming. Communities began to grow crops and keep domesticated animals. The earliest signs of farming practice in Great Britain and Ireland are in the south of England, but the practice spread across the country over the next 200 years with settlements established in coastal areas, and lowland areas accessible from the coast. In so doing, communities cleared areas of woodland to allow the cultivation of crops. Animals were herded on upland areas where open grassland was more extensive. The Neolithic people lived in settled community groups with a high level of social cohesion. Little evidence remains for Neolithic dwellings in Ayrshire. Most were probably of timber construction. Many burial sites and ritual monuments were built in stone and consequently survive as features in today's landscape.

The characteristic burial monuments of the Neolithic are chambered cairns which housed multiple burials in a chamber covered with a cairn. Sometimes it is only the structural stones of the chamber that survive. The chambered cairns on Ayrshire and Arran belong to the Clyde group of cairns which are found from the Solway Firth to the southern Hebrides, and the Bargrennan tombs which have a south-western Scotland distribution. The Clyde cairns seem to have been sited to have views over both upland areas and over water, being positioned to look over the sea or a loch, and include Giants Grave Chambered Cairn on Arran which overlooks Whiting Bay. The Bargrennan tombs includes a long cairn on the slopes of Cuff Hill near Beith, North Ayrshire.

Other monuments of the Neolithic include stone circles and standing stones that may have had ritual significance. The largest concentration of prehistoric monuments in Ayrshire (and one of the most significant in Scotland) is in Arran, where numerous outstanding chambered cairns can be seen, along with round cairns, stone circles and standing stones. A significant concentration of these are on and around Machrie Moor, part of a significant prehistoric landscape. It is interesting to note that the stone circles were preceded by timber circles on the same sites. Machrie Moor was sited near the highland/lowland fault line and was the focus of connections between Ireland and west-central Scotland.

Bronze Age (2,500-700BC)

The Bronze Age in Scotland is characterised by the use of copper and copper alloys for making weapons, tools and personal ornaments. During this period woodland clearance accelerated allowing more extensive cultivation on the lower ground, on raised beaches, along valleys and along the forest edges. The pasturing of cattle on the uplands was also more extensive. Hut circles and associated field systems have been found in areas least disturbed by agricultural improvements of later centuries. By the later Bronze Age enclosed settlements and fortified settlements were being constructed and survive as archaeological features, along with their associated field systems, in areas least disturbed by the agricultural improvements of later centuries.

Bronze Age burial practice generally differed from that of the Neolithic, and changed throughout the Bronze Age. Burials were typically in cists beneath round cairns. Late Bronze Age burials frequently involved cremation, and the burial of urns containing bones or within cairns or in urnfield cemeteries. It was common for old burial and ritual sites (such as Neolithic cairns) to be reused over many generations, hence the localised mixture of ritual practices.

Iron Age (700BC-500AD)

The introduction of iron technology from Europe around 700BC enabled the production of more effective weapons and tools and gives this period its name. Several factors contributed to changes the landscape of Ayrshire during the Iron Age. Firstly, a significant deterioration in the climate reduced the area of productive pressures on good land. This may have led to the felling of extensive lowland forests in order to increase areas for cultivation and stock rearing. The introduction of mould-board ploughs also allowed the cultivation of heavier soils, thereby increasing the scope for agriculture throughout inland Ayrshire.

Political control may have become a major driver in Iron Age society. Extensive defences including many forts and smaller fortlets or 'duns' were built on commanding hilltop sites throughout the region. Several vitrified forts, whose walls were fused together by burning, are found in Ayrshire, for example at Largs (Knockhill), West Kilbride (Auldhill), Kirkoswald (Dowhill) and Maybole (Kildon). Duns were more numerous and include those at West Kilbride, Dalry, Fenwick, Dundonald, Craigie and Maybole. Another form of defensive habitation found in Ayrshire is the 'crannog', an artificial island dwelling constructed in shallow lochs and connected to the shore by a causeway. These generally appear as small overgrown islands or are submerged irregularities. Examples can be found across Ayrshire, such as at Tarbolton (Lochlea), Kilmaurs (Buiston) and Maybole (Lochspouts).

Farmsteads established during the Iron Age became the main centres of habitation and it was common for farms to be developed and redeveloped over time on the same site. Many of today's farms are located on sites of Iron Age (or possibly earlier) origin. The typical low hilltop location of many Ayrshire farms is a legacy of this period.

Roman Occupation (c.70s AD - 290 AD)

There is little evidence of Roman occupation within Ayrshire as a whole, although trade with the Romans is evidenced by finds in Iron Age sites. The most significant Roman development was the fort at the top of the lrvine Valley opposite Loudoun Hill. This site was occupied and abandoned on several occasions during the Flavian and Antonine occupations of southern Scotland. It is probable that roads were also constructed into Ayrshire from the east, by the Romans, but no conclusive evidence remains. The Romans probably also advanced up Scotland’s west coast from the south, either following the coastline or over the Southern Upland moors. A Roman fortlet at Bladnoch, near Wigtown, indicates the most westerly point of known Roman occupation in the south of Scotland. In Ayrshire, a series of marching camps are known to lie immediately north of Girvan and another has recently been uncovered through excavations at Ayr. It is possible the Roman penetration of Ayrshire was more substantial but the evidence remains fairly slight for this area.

Early Medieval Period (c.200AD-1,000AD)

Few records and little archaeological evidence remains to provide a clear picture of developments during this period. It was a time of continued immigrations, political changes and warfare between groups. Due to its excellent communication links over land and sea, Ayrshire would see an influx of various societal and cultural influences during this period, namely from Gaelic, Brythonic, and Anglian origins. The placenames of Ayrshire reflect this linguist mix.

The Early Medieval period saw the emergence of the kingdom of Strathclyde, centred on Dumbarton Rock and much of the land that is present day Ayrshire was part of that kingdom.

Christianity was probably introduced to Ayrshire during the 8th Century with, missionaries entering the region from Ninian's church at Whithorn in Galloway. The 'Kil-' prefix in place names, e.g. Kilwinning, Kilbirnie, Kilmarnock, etc., is traditionally associated with early churches and dedications to early medieval saints. More positive proof of religious activity are the distinctive early medieval crosses installed between the 5th and 10th Centuries at Ballantrae, Girvan, Dailly, Colmonell, Maybole, Alloway and Kilbirnie.

Medieval Period (1,000AD-1,600AD)

The Medieval period saw the establishment of a monarchy that would rule what is now modern Scotland, along with the development of a feudal society in lowland Scotland, which copied many aspects of the Norman administration of England, and encouraged the immigration of Norman barons and churchmen into Scotland.

Ayrshire initially comprised four districts, each administered by feudal lords or the Crown. These were Cuninghame, Kyle Stewart, King's Kyle and Carrick. The main rivers of Ayrshire constituted the boundaries of each district, i.e. the lrvine, the Ayr, and the Doon. The feudal lords established bailiery courts and religious centres in each district. In Cuninghame, the bailiery court was established at lrvine and Kilwinning Abbey developed for the Tyronensian Order of monks.

In Kyle Stewart, the bailiery court was established at Prestwick and the Cistercian Order was granted a castle and land around Mauchline. In King's Kyle, a Royal Castle and St. John's church were built in Ayr. In Carrick, Turnberry was made the feudal centre and Crossraguel Abbey was constructed for the Cluniac Order.

The feudal overlords granted lands and delegated functions to lesser lords and their vassals. The lands granted form the basis of many estates in Ayrshire and at their centre, control was exercised from castles. Whilst some Iron Age forts were adapted, most castles of the early medieval period adopted Norman designs, i.e. motte and bailey castles which were usually constructed of earth and timber. This type of castle can be found throughout Ayrshire such as at Dalry, Beith, Largs, Dalmellington, Tarbolton, Ochiltree and Loudoun.

By the 12th Century, stone was used more widely in castle construction and older timber structures were reinforced or replaced by stone. The first major stone castles were built for the King and important barons, as at Loch Doon Castle and Dundonald Castle. By the 14th Century, stone built castles and tower houses were the usual residence for local lords. In the following centuries, these residencies became less austere; architectural ornamentation was added, interiors were decorated and glazed windows were used.

The majority of the medieval population was involved in farming (under a feudal tenancy arrangement). A typical farm unit comprised a group of dwellings for several families with gardens or kailyards. Nearby was the 'infield', an area intensively farmed on a run-rig system. Beyond the 'infield' was the 'outfield', which was cultivated but used less intensively with fallow periods. Oats, barley, peas and beans were typically grown in these fields. In the surrounding 'common' areas of rough pasture, cattle were herded or tethered.

The above system continued until the agricultural revolution of the 18th Century. It was responsible for extending woodland clearance throughout the region until Ayrshire was largely devoid of mature woodlands. Other impacts on the landscape during this time include the draining of Trindlemoss Loch in Irvine, a natural loch sitting in a glacial hollow. The drainage of the loch was complete by the end of the 17th Century.

The various religious orders were responsible for large tracts of land into which new agricultural techniques and crafts were introduced. Sheep herding and woollen textile manufacture were typical influences. Crossraguel Abbey near Maybole, founded in the 13th Century, was one of Scotland’s two Cluniac monasteries (Paisley was the other) and like many religious orders was established in the countryside in the vicinity of the burgh, and remains a dominant feature in the landscape. The extent of landscape modification, including the introduction of mills and, later, tower houses for the most important members of the community, which visually reference the seats of the noble families they hailed from, indicate a tight control of resources and left a distinct mark on the landscape. The introduction of Protestantism in the 16th Century saw the despoilation of previous religious centres such as Kilwinning, Fail and Crossraguel. From the 17th Century onwards, new Presbyterian chapels were constructed throughout Ayrshire and parish ministries established.

18th and 19th Centuries

By 1700, Ayrshire's population had risen gradually to around 50,000. This comprised mostly country dwellers based in farming communities or 'ferm touns'. After the Act of the Union in 1707, an economic revolution began which caused subsistence farming to be replaced by commercial farming, and promoted mineral exploitation and manufacturing industries. This revolution was fuelled by trading opportunities with the Americas and with England.

Manufacturing expanded rapidly in Ayrshire, initially based on textiles, particularly woollen goods, cotton and linen. Weaving centres were established at Kilmarnock and Stewarton, flax and linen was produced at Beith. The growth of the cotton industry then saw the development of the massive Catrine Works and workers' accommodation at Ballochmyle.

Many more cotton spinning works were then developed in Beith, Dairy, Kilwinning, lrvine, Kilmarnock, Dundonald and Monkton. Linen, silk, muslin and lace manufacturing also developed as specialist markets in the Garnock and lrvine Valleys. These developments caused the rapid expansion of towns and establishment of new industrial communities.

The above developments were accompanied by a transformation of Ayrshire's landscape as landowners sought to provide raw materials for the available markets. This process of agricultural improvements involved:

- the clearance of the old run-rig/infield and outfield system;

- the regrouping of many farmsteads and the development of new farm units;

- the renovation of farmland through deep ploughing, draining, liming and manuring;

- the enclosure of farms and regular subdivision into fields using hawthorn (and some beech) hedges and stone dykes in the uplands;

- the introduction of tree lines, avenues and shelterbelts;

- the introduction of a rotation system, i.e. the Fairlie rotation which takes 5/6 years and involves two thirds grass and one third crops.

In addition to the above measures, landowners planted woodlands around their estates, particularly in the vicinity of their mansions as part of designed landscapes. Notable early improvers in Ayrshire were Alexander, 10th Earl of Eglinton and John, 4th Earl of Loudoun, who undertook extensive improvements during the mid-18th Century.

The farm landscape of today is largely the product of these agricultural improvements. They were, however, not all-inclusive, and in many marginal areas the improvements were modest, leaving previous agricultural patterns legible in the landscape. In the north of Arran the absence of significant agricultural replanning has preserved the ancient 'clachan' farming patterns in certain areas.

As in Dumfries and Galloway, the deep red sandstone is prized for its building qualities. Its consistent durability yet ease of cutting and dressing, coupled with its extraordinary colour, has encouraged its local use for building and its quarrying for export from Ayrshire ports. The former Ballochmyle Quarry at Mauchline was once the main commercial quarry. Smaller local quarries also provided freestone for local construction. The distinctive red sandstone was used widely throughout Ayrshire and is a dominant characteristic of many towns. Local stone has been used for vernacular building and construction methods tailored accordingly. Locally, Old Red Sandstone, and certain grits and limestones have provided good masonry. The harder basalts and dolerites, however, have generally been used for rubble work.

A large proportion of central Ayrshire is underlain by coal measures (Ayrshire Coalfield) which contain productive coal seams and ironstones at various depths. This combination of raw materials, the accessibility of the area and the presence of plentiful water supplies, stimulated the development of the iron industry in Ayrshire. The region boasted 48 blast furnaces at one point in the 19th Century, with heavy concentrations along the River Garnock Valley, and the upper reaches of the River Ayr and River Doon Valleys.

The shallowest (most accessible) coals are around the edge of the Ayrshire Basin, bordering and underlying the eastern hill range. Ayrshire's coalfield was initially exploited by small-scale surface drift mining stoop and room methods in the 19th and early 20th Centuries and pits to provide fuel for lime burning, for fertiliser and for saltpanning. This market grew as industry developed and agricultural improvements demanded more fertiliser. It has left a legacy of bings, mining villages, disused railtracks and derelict structures.

Ayrshire's deep coals are located in the centre of the basin to the east of Ayr, about 600 metres beneath thick layers of Barren Red Measures, Permian sandstones and lavas. These are harder to extract and as a result they remained undisturbed until later deep mining technology made their extraction viable.

Large coal mines were developed near Kilmarnock, Cumnock, Dalmellington and New Cumnock where the coal is at shallow depth. The presence of iron ore within the coal measures promoted the development of Ayrshire's iron industry towards the end of the 18th Century. Muirkirk was the first iron centre followed by centres at Cessnock (Galston), Blair (Dalry), Glengarnock (Kilbirnie), Afton (New Cumnock), Lugar (Auchinleck), Portland (Hurlford), Waterside (Dalmellington), Eglinton (Kilwinning) and Ardeer (Stevenston). By 1869, there were 48 blast furnaces in Ayrshire served by a network of railways linking industrial centres and Ayrshire ports. Significant areas of former farmland were disturbed and developed for heavy industry. Coal bings, mine structures, furnaces, process areas, workers' dwellings and communication lines were introduced into the rural landscapes as north Ayrshire became heavily industrialised. By 1878, Ayrshire had 104 collieries and 42 blast furnaces, in addition it had a fireclay and coal tar industry and was supported by numerous engineering works.

Improvements in transportation facilitated many developments by providing access to markets and to manufacturing/processing centres. In the early 18th Century, local road improvements were undertaken by landlords. These were extended by the Ayrshire Turnpike Acts of 1767 and 1774 which led to a network of good roads. Industrialisation led to railway and port developments during the 19th Century which improved access to Glasgow and Ireland via Stranraer and Dumfries. By the end of the 19th Century, Ayrshire's population had become predominantly urban based and had grown to c.250,000.

Ayrshire was also home to the world’s first explosives factory, founded on the Ardeer peninsula in 1870 by Alfred Nobel to manufacture his new invention: dynamite. Nobel Industries Limited would continue to expand, before witnessing a steady decline in the second half of the 20th Century.

20th and 21st Century Developments

Industry

The 20th Century saw the dramatic decline of Ayrshire's heavy industries. The North Ayrshire Coalfield was 'worked-out' by conventional mining methods, resulting in the closure of 80 pits between 1900 and 1930. In the same period, 54 pits closed in central Ayrshire. The National Coal Board, established in 1947, concentrated its efforts in the large, deep mines of central Ayrshire until open-cast methods allowed the extraction of previously unviable shallow coals. Open-cast coal mining has, therefore, increased, resulting in significant local landscape changes.

Many decades of shallow and deep coal mining, together with associated iron working, have left a legacy of bings, excavated land and the remains of related infrastructure such as railway embankments, inclines and bridge structures. Most bings are of relatively modest size, and while some have been reclaimed, many remain as important features in the local, and often wider, landscape. Many longer views across the southern part of the Ayrshire basin are punctuated by the steep-sided, flat topped spoil tips which rise above the surrounding landscape.

The restoration of open-cast sites is a further issue of importance for the landscape. Although past schemes have tended to include the nominal restoration of sites to their previous land use, rarely has this been entirely successful. One of the most consistent criticisms of past open-cast restoration schemes has been the bland nature of the new landscape, often with constant engineered gradients, unrelieved by localised changes in topography or vegetation and lacking the features and grain which combine to create landscape character. East Ayrshire Council and its partners have recently initiated the Coalfields Community Landscape Partnership to encourage local communities, charities and agencies to work together to protect and promote the legacy of the coalfields as a socio-economic catalyst.

All of Ayrshire's ironworks had closed by the 1920s, leaving only Glengarnock Steelworks and a number of foundries to continue for a few more decades. Engineering industries similarly declined, although a number of textiles industries do continue. The decline of these industries has removed the raison d'etre of several communities and has left some urban housing schemes, once related to the coal/iron industries, in a countryside setting.

Some industries continued to thrive however. Nobel’s explosives plant, run by Imperial Chemical Industries as ICI Ardeer, continued to thrive until the 1960s. At its peak the factory employed almost 13,000 people, to the extent that it had its own dedicated rail and bus service.

Agriculture

Farming became more specialised during the 20th Century, particularly in dairying, potatoes and sheep farming, and more land has been given over to grazing. The use of fertilisers has increased and the greater numbers of stock require the importation of feedstuffs, silage making and longer rotations under grass. This has introduced silage towers as common features in the landscape and has generally diminished the diversity of the agricultural scene. Dairying operations have changed; cheese is no longer produced on farms and consequently, traditional buildings have become redundant and the keeping of small numbers of dairy fed pigs and poultry is rare. The latter are now typically farmed in a concentrated fashion as pig farms or with broiler houses.

The social changes in the 20th Century saw a number of the mansion houses abandoned and deroofed to avoid crippling tax duties, e.g. Loudoun Castle, Dalquharran and Eglinton Castle. Despite this change of socio-economic circumstances Ayrshire retains a fine selection of castles and mansion houses that remain privately owned i.e. Blairquhan, Kelburn Castle, Bargany House, Sorn, Craigengillan etc. These estates over the last few decades have had to radically alter their business models and diversify: hospitality in its widest sense is now seen as an important income stream, A number of mansion houses have found other uses, such as educational establishments, hospitals, hotels or residential flatted dwellings. The conversion and reuse of these buildings may involve associated “enabling development” - works permitted without which the reuse of the main house would be unviable. In some instances, there can be a significant level of change to the setting of the main house and associated landscape.

Forestry

In 1919, the Forestry Commission (now Forestry Scotland) was established with a remit to build up the UK's strategic reserves of timber. The Forestry Commission purchased large areas of uplands and estate forests and pursued a policy of maximum timber production. The most extensive forests were developed in the Southern Uplands extending into Galloway. These include the Glentrool, Loch Doon and Carsphairn Forests. Forestry in Ayrshire has increased steadily during the 20th Century, latterly by private investment in the foothills and moorland plateaux further north.

Changes in the Forestry Commission's policy objectives throughout the 20th and 21st Centuries have seen a shift from highly commercial 'blanket' afforestation to multi-function forests that accommodate recreation, and respect the natural and built heritage resources of an area. These shifts have resulted in more sympathetic forest designs which employ greater proportions of open space, respond to topography and contain greater variety of species, particularly broadleaves.

Transport

Increased car ownership and individual mobility since the Second World War was instrumental in the closure of some of Ayrshire's railways in 1963, and created the demand for a road building/improvement programme. Major road improvements were undertaken, notably the dualling of the A77, the construction of the Irvine bypass (A78) at a longstanding traffic bottleneck and, latterly, an extension to the A78 bypassing the ‘Three Towns’ (Stevenston, Saltcoats, and Ardrossan) in 2004. Most of Ayrshire's main roads have also been improved, including bypasses of Ayr and Kilmarnock.

There is a frequent rail service between Glasgow and Ayr and Kilmarnock, also linking with Stranraer and the Irish ferry services. Some freight trains run through the region as well.

The airport at Prestwick was founded in the 1920s by members of the Glasgow Auxiliary Air Force Squadron, becoming a passenger airport in 1938. In World War Two it was used as a military base. Post war, it returned to being a civilian passenger facility, the only one offering transatlantic flights at that time. It was developed and the runway extended in 1960 and today is a centre for aerospace technology, as well as maintaining its role as an international freight and passenger airport, albeit with a declining passenger numbers in the 21st Century. The airport creates a focal point in the area of noise and activity.

Settlement Growth

The mobility provided by the car has created commuter demands for development in Ayrshire's countryside and has helped to sustain settlements where local employment opportunities have declined. The scenic and accessible nature of much of Ayrshire encourages interest in development in the countryside. There are predominantly demands for houses, agricultural buildings and tourist accommodation and urban areas continue to expand. Whilst the lowlands are characterised partially by their settled nature, continuing incremental development in the countryside could change the rural character of the landscape.

Identified as one of several ‘growth areas’ of the central belt in the Central Scotland White Paper of 1963, Irvine was subsequently designated Scotland’s fifth and largest New Town in 1966. The town, incorporating Irvine, Kilwinning, and a series of smaller settlements, underwent major changes during the following 30 years.

Irvine was unique among Britain’s New Towns for having a sandy coastline, and unusual for incorporating two existing substantial towns. The initial proposals by the development corporation sought to transform Irvine into a leisure and tourism hub for Ayrshire and the wider southwest region. However, subsequent political and economic changes meant this was never fully realised.

Much of Irvine’s built environment serves as an excellent study in changing practices of urban redevelopment throughout the second half of the 20th Century: from large, ambitious Modernist schemes that referenced international architecture; to conservation streets such as Glasgow Vennel; to more sensitively designed schemes such as the Harbourside. The road and path network of the New Town forms an unusual landscape structured around the exponential growth of car ownership in the 1960s and 1970s and the impacts this would have on the safety of pedestrians. This landscape provides an insight uncommon in Scotland into attempts by the state to manage the growing conflict between pedestrian and car.

The main settlements have continued to grow, thereby increasing demands for development along the Ayrshire coast, particularly between Ayr and Ardrossan. In recent years there has been a steady rise in the demand for development sites within and in close proximity to main settlements, which has been accommodated through strategic and local planning on a mixture of brown and greenfield sites. While the New Town of lrvine absorbed a considerable amount of development, many other settlements, such as Kilmarnock, Ayr and Kilbirnie, experienced considerable growth, often in the form of incremental additions in peripheral locations. In many cases, ring roads and bypasses were used to define the edge of settlements, with new development infilling land between the settlement and road in question. Often the expansion has pushed development outwards from the original nucleus (perhaps a bridging point or the site of a mill). Twentieth Century development is frequently a prominent feature in the landscape. This is particularly the case in relation to mining settlements in the Cumnock and Doon area, where little woodland screening is present in the expansive landscape.

Changes in agricultural practice have brought about a range of farm building developments and conversions. Traditional buildings, being unsuited to contemporary needs for machinery or livestock, have become largely redundant. There is a significant demand for traditional buildings as restoration projects. Many of these are redundant farm buildings or isolated dwellings in the countryside. Generally, these restoration projects have significant environmental benefits; in some cases, however, there are associated changes in character. These are typically caused by changes to windows, white-wash treatments, the creation of driveways, gates and elaborate gardens, all of which change the building and its immediate setting. Other aspects which may arise are where the development requires additional or upgraded infrastructure such as roads, water supply or foul water disposal. In flat coastal areas, for example, sewage disposal requires the use of pumping stations.

Tourism and Recreation

Ayrshire is a long-established destination for holidays and day trips. Historically, most activity has been focused on towns along the coast, from Girvan in the south, through Ayr, Prestwick, Troon, Irvine and Ardrossan to Largs. Visitors would flock to the Ayrshire coast either by steamer or by rail, a journey known as going doon the watter. Many towns and villages experienced considerable growth during the Victorian period and again in the post war period when caravan sites and holiday camps opened to service the industrial central belt. More prominent buildings from Ayrshire’s initial growth in tourism include Turnberry Hotel and Ayr Station Hotel. One of the largest navy training camps was converted to a holiday park - Butlin’s Ayr. From 1987-1998 it was run as Wonderwest World and now operates as Craig Tara, Ayrshire was also home to the Magnum leisure centre, opened in 1976 as part of Irvine Development Corporation’s proposals for Irvine New Town. The largest of its kind in Europe when constructed, the Magnum’s design showed strong influence from the pavilions built for World Expos, and pioneered the use of large span roofs in Scotland. Once a tourist draw on a national scale, the Magnum was demolished by the local authority in 2017.

Outside the main settlements, large parts of the lowland coast are occupied by the golf-courses for which Ayrshire is renowned. The modern game of golf originated in Scotland, and the oldest golf tournament in the world, The Open Championship, was first played at Prestwick Golf Club in 1860.

Ayrshire is also made famous by Robert Burns, many of whose poems and songs make reference to local places and features. Today many sites of importance are linked by the Burns Trail.

Latterly, tourism and recreation pressure has taken two principal forms:

- The emergence of proposals for large scale, formal recreation developments including theme and fun parks. These may relate to sites already in use (e.g. as caravan sites), to historic estates seeking additional sources of revenue, or previously undeveloped sites;

- The growth of informal recreation activity outwith the main tourism centres, encouraged by the potential offered by 'heritage' attractions such as castles, National Trust for Scotland properties, industrial archaeology museums and the comparatively unvisited uplands in the south.

Signage related to tourism facilities can become cluttered in popular holiday areas.

Renewables and Infrastructure

Loch Doon is one of the two main storage reservoirs for the Galloway hydro-electric scheme developed in 1935. The Loch’s original water level rose by at least 10 metres and changed shape dramatically. The scheme straddles Dumfries and Galloway and Ayrshire areas and consists of six power stations and eight dams. The buildings and dam at Loch Doon are now listed for their engineering significance. Loch Doon Castle which originally was sited on an island in the loch was rebuilt in the 1930s at the side of the Loch to preserve it.

Drinking water reservoirs, such as Craigendunton and Knockendon, supply towns in the area and mostly date from the 20th Century. Lochspouts Reservoir was built in 1882 to provide a water supply for Maybole but is disused now.

Hunterston ‘A’ nuclear power station opened in 1964 and provided energy for the west coast of Scotland until 1990 when it began the decommissioning process. This station was joined by Hunterston ‘B’ in 1976, which continues to generate electricity at a reduced capacity. The Scottish Southern Energy Board explored options for ‘C’ and ‘D’ power stations at Hunterston, but these were never developed.

Photovoltaic panels are becoming a common sight especially on council owned buildings and housing association developments. Lochcraigs solar farm near Kilwinning is a larger-scale installation of around15 hectares.

Ayrshire has a number of installed large-scale windfarms, from Arecleoch in the south to Whitelees in the north. These can be visible over large areas, especially as they are generally situated in higher and exposed areas. Hadyard Hill Wind Farm was the first windfarm in Britain to have a capacity of over 100MW. Its 52 turbines are now dwarfed by Whitelees on the East Ayrshire/East Renfrewshire border which has a capacity of over 500MW.

Associated with these developments are electrical transmission cables, substations, pipes and pylons which generally follow the main transport routes in the area.

Landcover

Ayrshire and Arran encompass coastal, lowland, mid-altitude and upland landscapes which, despite the predominance of cultivated land, support a variety of flora and fauna. In addition, the complex geology of this region provides a broad range of geological and geomorphological interest. The following paragraphs seek to summarise the key natural heritage attributes of Ayrshire.

Upland/Moorland Habitats

The highest mountains of Ayrshire are associated with the granite and metamorphosed rocks at Loch Doon and in North Arran. These are encompassed within the region's largest Sites of Special of Scientific Interest (SSSIs) - Merrick Kells and North Arran - and support a diversity of upland communities more typical of mountains further north. They contain combinations of dry heath and bilberry on upper slopes, with mosaics of fescues and mosses. Mires are extensive at lower altitudes dominated by purple moor-grass, heather deergrass and hare's tail cottongrass. The variety of soils also supports areas of woodland (typically birch, rowan, oak and ash) but Arran also has its endemic whitebeams: Sorbus arranensis and Sorbus pseudofenica. These combine with the grasslands and brackens to create a rich mosaic capable of supporting a variety of insects, animals and birds (including golden plovers, dunlin, hen harrier, raven, peregrine and golden eagle). When viewed from a distance, this creates patterns of ochres, browns, greens and oranges, broken occasionally by rock outcrops, which change seasonally into flushes of green, pink heather blossom, russets of bracken and deergrass and whites of snow.

Moorland and Mosses

Moorland also covers significant areas of mid-altitude hills and plateaux in Ayrshire. This generally comprises a mixture of wet and dry heaths, peatland mosses, fens and mires, with local variations in response to the changes in geology and hydrology. Several 'mosses' remain as isolated features within pastoral farmland, where local land improvements have reduced their previous extent. These isolated raised bogs and mires are locally important for wildlife and provide landscape diversity. A number of these have consequently been designated as SSSIs (e.g. Bankhead Moss, Beith; Barlosh Moss; Cockinhead Moss; and Dykeneuk Moss). The larger areas of plateau moorlands and mosses also contrast with the adjacent cultivated/improved grasslands and provide valuable tracts of undeveloped land as habitats for a broad range of insect, animal and bird life.

Native and Semi-Natural Woodlands

The great majority of Ayrshire's native woodlands were cleared by past generations to increase areas of cultivation or to provide timber. Only a few protected areas have retained old semi-natural or native woodlands which harbour significant wildlife interest. These are mainly within narrow steep-sided valleys, remote upland fringe areas or are parts of old estate woodlands which have encompassed ancient woodlands, possibly preserved for hunting. The best examples include River Ayr Gorge, Craig Wood of Glen Tig, Ness Glen near Loch Doon, Skelmorlie Glen, Benlister Glen and Dundonald Wood. They contain native and semi-natural woodlands which include oak, ash, elm, alder and birch, with often introduced beech and sycamore.

Pockets of ancient and semi-natural woodland exist throughout Ayrshire, adding diversity to local landscapes and wildlife. Many of these most significant areas are protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest. However, the registers of Ancient and Semi-Natural Woodlands do not take account of woodlands of less than two hectares. These small woodlands make valuable contributions to the landscape.

Grasslands

A large proportion of Ayrshire's grasslands have been modified by the agricultural processes of improvement and cultivation. These have removed or reduced ecological diversity except in the limited areas excluded from these processes. The most extensive grasslands of nature conservation interest are in the unimproved upland fringe areas or on low igneous hills where the soils support a variety of grassland habitats. These include base rich grasslands, herb rich grasslands, wet and dry grasslands, usually interrupted by flushes and mosaics of heath, fen and mire. In coastal areas, the salt spray also influences the vegetation patterns by lowering the acidity of the soils as at Bennane Head.

Lochs

Ayrshire lacks large natural lochs (Loch Doon having been artificially enlarged) but has numerous small lochs and reservoirs. These provide open water valued by a wide range of breeding and wintering wildfowl including rare species like red-throated diver. They also have a range of aquatic and marginal vegetation which provides great diversity within concentrated areas. Lochs within Ayrshire may contain emergent reedswamp, and be fringed by mires, fen, carr or marshy grasslands, dependant on altitude, underlying soils and geology. Several of these lochs have been designated SSSIs including Ashgrove Loch, Martnaham Loch, Bogton Loch and Loch Doon. Many other small mire lochs are also included within larger designated areas.

Coastlands

Ayrshire's extensive coastline has numerous features of nature conservation interest. These are principally its intertidal mudflats, sands and shingles, its sand dunes and dune grasslands, its sea cliffs and former cliff slopes and the transitions of vegetation between these different zones. These features and the broader areas influenced by salt laden winds support a broad range of seabirds and wildfowl, locally distinctive or rare plant communities and insects which in subtle ways all contribute to the local character of the landscape.

Trees, Woodlands and Hedgerows

The majority of Ayrshire’s native and semi-natural woodlands are located in the inaccessible and protected environments of steeply sided valleys, remote mountain slopes and old estates. These only represent a small percentage of Ayrshire’s total woodland cover and make relatively localised contributions to landscape character. The more extensive tree and woodland features are, therefore, forests or are part of farm landscapes.

Policy Woodlands

The woodlands of estates and their designed landscapes surrounding mansion houses and castles are significant features of the Ayrshire landscape, making positive contributions to most of the lowland and transitional areas. They represent some of the most extensive early woodlands established at a time when Ayrshire was left with little native tree cover. In general, these woodlands provide shelter and enclosure for parklands and the home farms. Many adopt formal and informal design layouts to enhance views from the mansion house and to accommodate carriage drives, walks and woodland garden features. The composition of these policy woodlands is usually a mixture of deciduous and conifer species, often incorporating exotic specimen trees and shrubs. Typical mixes include: oak, elm, beech, lime, horse chestnut, sycamore, ash, yew and Scots pine. The inclusion of tall conifers is also common and often identifies designed landscapes from considerable distances; redwoods, firs, cedars and monkey puzzles were popular choices. Several designed landscapes occupy coastal sites where their woodlands are wind-trimmed and have dense, distorted branching patterns. This makes them particularly distinctive, and essential features of the raised beach cliff lines.

Arguably the most significant policy woodlands, which make the greatest contributions to the landscape, are those of Culzean Castle, Kelburn Castle, Knock Castle and Brodick Castle on the coast; Loudoun Castle, Glenapp Castle, Sorn Castle and Auchinleck inland. In addition, there are many remnants of designed landscapes and policy woodlands throughout Ayrshire which have a significant combined contribution to the settled and prosperous agricultural character of the region. Other notable policies include those of: Blair, Dumfries House, Dundonald Castle, Sundrum Castle, Craufurdland Castle, Cloncaird Castle, Caprington Castle, Rowallan and Lanfine House.

Farm Woodlands, Tree Lines and Hedgerows

The most widespread tree/woodland features are those of the farm landscapes, most of which originate from the 18th and early 19th Centuries. An essential feature of Ayrshire's farms is the extensive pattern of hedgerow field enclosures. These define a roughly rectilinear pattern of enclosure with clipped hawthorn hedges (occasionally beech is used, but not extensively). Field sizes vary from around 0.5 hectares to 1.5 hectares in the lowland areas, become larger in the uplands, and often switching to stone dyke enclosures. The hedgerows are frequently reinforced by tree lines, usually beech, oak, ash or sycamore (elm now declining due to Dutch elm disease). Hedgerow boundaries are a critical constituent of many lowland or transitional landscapes, often creating a sense of enclosure and emphasising the contrast between lowlands and uplands. Farm woodlands and trees are important features throughout Ayrshire, and become key space-defining elements in the lowlands.

Forestry and Contemporary Woodlands

The most extensive woodlands in Ayrshire have been developed over the last century by the Forestry Commission and private forest developers. In the early part of the 20th Century, coniferous forests were planted to meet Britain's crisis demands for timber. Productivity was a prime consideration resulting in the forests of few or single species with straight or geometric margins. Forests originating prior to the 1970s are generally of this type. In the south west of Scotland, the success of Sitka spruce as a commercial crop determined that forests were predominantly or wholly of this species. Very large areas of plateau moorland and upland were planted with monocultures of Sitka spruce or Douglas fir, creating dense woodlands which transformed the previously open uplands and which obscured the subtleties of the moorland landscape. Forests often extended up to road sides, thereby containing views from the road, while felling coupes were selected without regard to possible effects on either the local or the wider landscape.

It was during this phase of forestry practice that the first large forests were created in southern Ayrshire. However, the Forestry Commission's policies towards forest and woodland design have been developed and refined considerably over recent years. Guidance now requires that new forest plans are sympathetic to landform, provide a greater proportion of open space and of broadleaf/other conifer species. In addition, the design of felling coupes is required to add greater age diversity to the forests. All these measures result in the marked enhancement of many commercial-forest landscapes, in terms of visual amenity, ecological diversity and recreational potential.

Large areas of marginal farmland were afforested, i.e. moorland plateaux, foothills and lower parts of the Southern Uplands. Extensive forests are, therefore, a common feature of these landscapes. These areas, and parts of North Ayrshire too, attract interest for forestry and the area of commercial forest in Ayrshire is growing steadily. Current forest policy encourages multi-use woodlands of high design, amenity and conservation values. Recent forest plans seek, therefore, to create more sympathetic integration with landform and land uses. The physical manifestation of these objectives can be seen in the establishment of deciduous fringes; open space patterns that respect views, heritage features and access routes; and the provision of recreational facilities. The Loch Doon area of the Galloway Forest Park best illustrates these features of modern forestry practice.

Archaeological Features – in more detail

Evidence of prehistoric human activity in Ayrshire is most visible in Arran, where the greatest concentrations of monuments remain intact as significant features in the landscape. These include the stone-built ritual and funerary monuments such as chambered cairns, round cairns, standing stones, stone circles and inscribed stones, all of which are prominently positioned on hill slopes close to the coast and still clearly visible as human constructions, despite their usual grass cover or partially ruined condition.

The mainland of Ayrshire contains a number of cairns that are markedly different from the “Clyde” type known on Arran. Most of these cairns occur in the hillier and less densely populated southern part of the region. The cairns here vary widely from small, Bronze Age cairns on hilltops to large, monumental chambered cairns. The latter group have been termed “Bargrennan” cairns, after Bargrennan White Cairn near Glentrool. This substantial round cairn is lined by a kerb of large boulders, with a small central chamber accessed by a narrow passage. These cairns are often located on low rises that afford panoramic views, or on the shoulders of hills overlooking lowland valleys. Bargrennan cairns are typically round, with at least one but often multiple chambers, each accessed by a passage. Some of the finer examples of the group are Arecleoch Cave Cairn and Cairnderry Cairn, excavated in 2002-3.

Throughout mainland Ayrshire many prehistoric features are still visible in the landscape, particularly in the less cultivated hills of North Ayrshire and in the coastal hills south of Ayr. These include many cairns, a few chambered cairns and long barrows, standing stones and inscribed stones. The Ballochmyle cup and ring marked rocks are perhaps the most significant Neolithic/Bronze Age feature in mainland Ayrshire.

Many prehistoric sites are difficult to detect in the landscape, but are easier to see under certain climatic conditions. Frost cover, snow, low sunlight and crop marks can expose the locations of ancient dwellings and lines of enclosure. These more ephemeral earth and timber structures from the prehistoric period often appear under these conditions and are subtle but intriguing components of the landscape heritage.

Iron Age features are more evident throughout the region as a result of their large numbers, their younger age, their long occupation and their robust construction/size of construction. Approximately 200 forts and duns have been discovered in Ayrshire.

These are circular stone structures usually sited on the top of hills, ridges or prominent knolls from which they could guard surrounding farmland. Forts were generally of circular plan and built of stone and examples include the near-circular fort of Dowan’s Hill, near Minishant, South Ayrshire and Knock fort near Largs, North Ayrshire. Several forts in Ayrshire, including Knock fort, were 'vitrified', a process which involved burning to fuse the rampart materials. This fusing process has frequently helped to preserve the structures from erosion and stone robbing. Duns are similar to forts but are smaller defensive structures capable of accommodating only one family or small group of people. While forts occasionally had outer walls and ramparts, duns generally had only an outer bank to protect a single entrance. The remains of most forts and duns represent a small proportion of their original size and many are wholly or partially overgrown. They are nevertheless easily recognised as distinctive lumps on the tops of many hills. Many other earthworks remain from the Iron Age period, the legacy of settlements and defensive structures. Crannogs are also distinctive local features if only few in number.

Of locally significant and certainly symbolic importance are the Celtic crosses which marked early Christian gathering places throughout Ayrshire. These are perhaps not major features of the landscape, and a number have been taken into museums. Where they remain, they make a considerable contribution to the local landscape character.

Built and Industrial Heritage Features

Ayrshire has a rich legacy of built and industrial heritage which charts the progressions over this millennium from simple to sophisticated buildings and which reflects the later changes in society as a result of the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions. The region's geological foundations are fundamental to these processes in providing raw materials for building construction and for heavy industries. The following paragraphs seek to outline the nature of the built and industrial heritage features which have such a significant influence on the character of the region as a whole and of its constituent parts.

Castles and Country Houses

The Norman influenced motte and bailey castles represent the earliest form of 'castle' structure present in Ayrshire. These remain as earthworks usually overgrown and lacking any significant stone structures. The early Loudoun Castle is a good example of such a feature, now incorporated within the grounds of the later castle. Other significant 'mottes’ include Castle Knowe and Montfode Burn Motte in North Ayrshire; Dalmellington Motte in East Ayrshire and the Tarbolton Motte and Helenton Motte in South Ayrshire. Dinvin Motte, south of Girvan, survives as a particularly fine and unusual example of this type of fortification.

The stone built structures of later centuries are generally more significant features in the landscape, especially where they occupy commanding sites unobscured by vegetation. Loch Doon Castle, a unique eleven-sided curtain-wall castle dating from the 13th Century, is such a feature. It originally stood on an island in the loch but was resited in 1935 when Loch Doon was enlarged as a reservoir. More typical of the 13th to 15th Centuries was the tower house, a tall defensive structure of square plan with few small windows. Many of these towers are strategically located along the narrow valleys and glens of the southern parts of the region, to guard and control these important routeways. Examples in this group include Ardstinchar Castle, Carleton Castle, and the brooding hulk of Craigneil Castle. Dundonald Castle also dates from this period and has a commanding presence on its natural rocky knoll. Lochranza Castle in Arran illustrates how many fortified houses were modified and enlarged by successive occupants. This predominantly 16th Century 'L' shaped castle originated as a 13th Century fortified house. It is largely intact and represents an evocative feature at the head of Lochranza Bay.

The late medieval period saw the consolidation and development of estates under more peaceful conditions. At their centres, castles and tower houses were enlarged, improved or replaced by more sophisticated buildings. The influence of Europe and the Renaissance was reflected in the adoption of classical architectural styling and in the layout of formal landscapes. Many castles remain from the mid to late medieval period of various sizes, styles and conditions. Regardless of their differences, they are all important local features that add mystery, romance and reinforce the identity of their surrounding landscapes. Notable castles from this period include: Auchinleck Castle, Martnaham Castle, Ardmillan Castle, Knockdaw Castle, Blair Castle, Kirkhill Castle, Knockdolian Castle and Pinwherry Castle.

Whilst many castle ruins now stand as isolated features, many of the residences of the grand estates have remained in occupation over many generations and have developed grandiose mansion houses/castles as the centre-piece to extensive designed landscapes. The most significant of these are well known regionally and nationally and have landscapes included within the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland. The Inventory sites include: Culzean Castle, Brodick Castle, Kelburn Castle, Loudoun Castle, Eglinton Castle, Rowallan, Rozelle (in Ayr), Bargany, Glenapp, Kilkerran, Blairquhan, Auchincruive, Dumfries House, Annick Lodge, Blair Estate, Craingengillan, Lanfine, Skeldon House and Carnell.