Isle of May National Nature Reserve - Annual Report 2023

Authors: David Steel and Thomas Skinner

Published: 2024

1. Introduction

The Isle of May NNR was staffed by the NatureScot team from March to November, as Reserve Manager David Steel returned for his ninth season whilst Thomas Skinner started his first season as Assistant Reserve Manager from early May. The island was manned from 26 March - 12 December with NatureScot staff and volunteers as well as various research groups and organisations.

The seabird breeding season proved successful, especially for European shags and kittiwakes, although no terns nested for the first time in decades. Unfortunately, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus (known as bird flu) was once again confirmed on the island. This coincided with a surge of cases at seabird colonies down the east coast as it was circulating widely within wild seabird populations in Scotland. For all those visiting and working on the island, extra biosecurity measures were put in place.

During mid-June, the North Sea experienced a ‘marine heatwave’ as sea surface temperatures were up by 4oC above normal for the time of year. Around the island, the sea showed temperatures of 16.5 degrees for almost a week, which is 3 degrees higher than we would expect in June. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration categorised it as a Category 4 (extreme) marine heatwave event. This is likely to have a significant impact on marine life; the heatwave will mean a nutrient and oxygen disruption in the sea surface disrupting the marine food web (plankton and everything which feeds on it, including sandeels).

Acknowledgements

The information and data collected for this report came from a variety of sources, including the NatureScot team of David Steel, Thomas Skinner, Rachael Davey, Finley Dennison and Andrew Shaw; the UKCEH team of Mark Newell, Josie Hewitt, Francis Daunt, Mike Harris, Erin Taylor, Ella Benninghaus and Sarah Burthe; the Edinburgh University team of Chiara D’Avino, Eve Merrall, Hannah Ravenswater and Fiona Greco; the BTO team of Gary Clewley, Lucy and Daniel. Also, thanks to the Isle of May Bird Observatory Trust and members, various boatmen and others who continued throughout the season.

2. Biological recording

2.1 Introduction to breeding seabirds

As part of NatureScot’s core NNR management work, the breeding seabird populations are monitored to allow assessment of trends and to report on the Special Protection Area (SPA) qualifying species. Further seabird monitoring is carried out by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH), under contract to the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO). Data from this monitoring work is integral to JNCC’s national system of long-term monitoring for seabird populations, as the island is one of four strategic monitoring sites in Great Britain. The other three sites are Skomer, Canna and Fair Isle.

NatureScot carries out the population counts of the cliff-nesting seabirds (fulmar, shag, kittiwake, razorbill and guillemot) alongside nesting terns on an annual basis, whilst large nesting gulls and eiders are counted every two years. Due to the scale of the operation, a puffin census is carried out every five to six years.

UKCEH monitors the breeding success, return rate, survival and food intake of the auks, shags, fulmar and kittiwakes. Other island partners such as the Isle of May Bird Observatory Trust (IOMBOT), Edinburgh University, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and St Andrews University provide numerous other pieces of data invaluable to this report, such as the dates of first eggs and chicks and sightings of migrant birds, cetaceans and lepidoptera. In the 2023 season, due to avian influenza (HPAI), there were no ground counts of large gulls and eiders, and the proposed puffin census was cancelled. A review during the winter of 2023/24 will assess the likelihood of these surveys being conducted next year.

2.2 Population monitoring of cliff-nesting seabirds

2.2.1 Sections and timings

The detailed methodology for the five cliff-nesting bird species (guillemot, razorbill, kittiwake, fulmar and shag) is set out in the Isle of May Monitoring Handbook (NatureScot, 2001, revised 2002, 2011, 2021). The island is divided into the same standardised count sections as have been used in previous years. All species are counted once during the first week in June to capture a snapshot of the populations. Counts from sea (using boat) were added in 2018 to allow those birds nesting in caves and areas unseen from land to be included in the population counts. The majority of the all-island count was carried out by David Steel from 1-8 June and in sections that were sensitive, data was provided by Mark Newell of UKCEH to avoid additional disturbance.

2.2.2 Cornerstone plot counts

The counts of individual razorbill and guillemot are converted to estimates of numbers of pairs. The number of both species breeding at the Cornerstone plot is monitored by UKCEH. A count of each species was made at the Cornerstone plot at the beginning of every count session. For each species, the number of pairs known to be breeding at Cornerstone was divided by the relevant Cornerstone count, for every count session. This provided a “k” value which represents the difference between the number of individuals counted and the number of actual breeding pairs. By multiplying this “k-value” with the number of individual birds counted during a session, the number of pairs can be estimated for that session. Keeping raw counts to within a few hours of the Cornerstone plot count allows for the variation in attendance of adults on the cliffs.

2.3 Results of cliff-nesting seabirds

Key tables for the breeding seabirds are available to download in the attached spreadsheet at the end of the report - quick reference guide:

- Table 4: The key dates throughout the 2023 season for each seabird breeding species

- Table 5: The overall counts for 2018-2023 for each of the five cliff-nesting species

- Table 6: The different section totals for each species

- Table 7: Breeding survival rates

- Table 8: Productivity of certain key breeding species

- Table 9: Population counts of the main seabird species

- Table 10: Population estimates of ground-nesting seabirds

2.3.1 Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis)

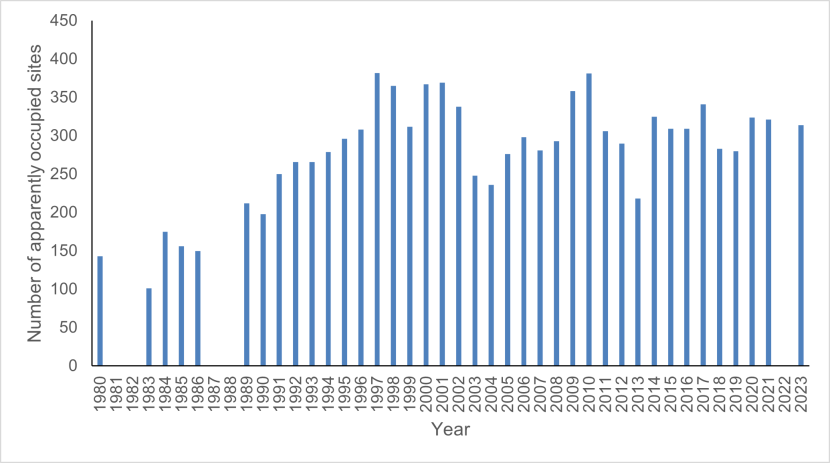

Bar chart showing numbers of fulmar, apparently occupied sites, from 1980 to 2023, except for 1981, 1982, 1987,1988 and 2022. Year is along the x axis, from 1980 to 2023, and number of apparently occupied sites is along the y axis, with a scale that runs from 0 to 450. Counts are quite variable but have shown an overall increase. A visual representation of some of the data from Table 9, which gives figures for fulmar, shag, cormorants, kittiwake, guillemot and razorbill.

The number of apparently occupied sites was 314 (AOS).

The species was present on the cliff ledges throughout January-March and, as usual, birds disappeared for a brief period in early May, prior to the start of the breeding season. The first incubating bird was discovered on the early date of 11 May on the south side of the Loch and therefore good numbers were settled for the summer. The first chicks hatched from 5 July, with the first fledgers taking to the wing from 15 August. Nesting productivity indicated a breeding season of 0.36 chicks per nest, the lowest since 2012 and mirroring other fulmar colonies nearby. Following the breeding season, the species became scarce in September-October, with single figure counts, before numbers increased in late November and December.

2.3.2 Shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis)

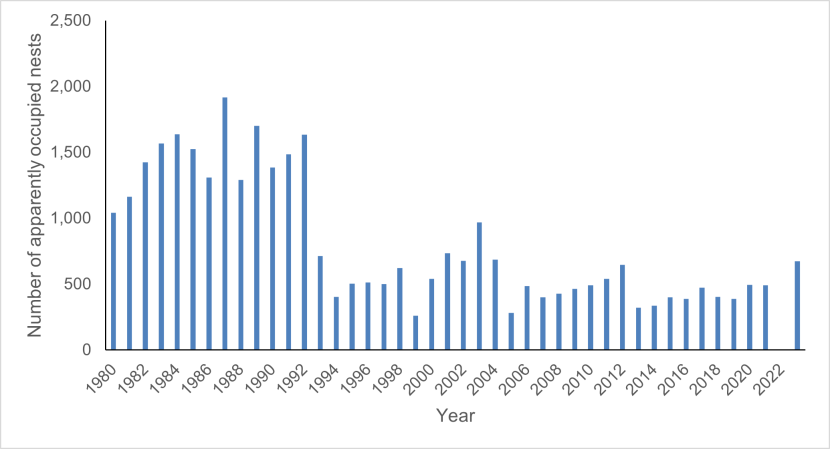

Bar chart showing numbers of breeding shag, apparently occupied nests, from 1980 to 2023, except for 2022. Year is along the x axis, from 1980 to 2023, and number of apparently occupied nests is along the y axis, with a scale that runs from 0 to 2,500. Counts are quite variable and show an overall decline. A visual representation of some of the data from Table 9, which gives figures for fulmar, shag, cormorants, kittiwake, guillemot and razorbill.

The number of apparently occupied nests was 674 (AON).

Traditionally, the species is the first to settle and start breeding and this year was no different. Good numbers overwintered on the island and nest building activities and courtship displays were noted during February. The mild settled weather encouraged early nesting as the first eggs were noted on 20 March. Return rates were above average, with the figure for the survival rate of adults calculated at 85.7%. The first chicks hatched from 21 April and although the chicks were fledging by 27 May, some birds were still nest building, showing the protracted nature of the shag breeding season. Nesting productivity indicated a return of 1.81 chicks per nest, which is average for recent years. The last chick to fledge was noted in early September on Rona. The population showed a very welcome increase with 674 apparently occupied nests (AON), the highest for twenty years. Thereafter, large numbers remained around the island throughout the autumn and winter, although the late October storms appeared to have a detrimental effect on birds.

2.3.3 Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla)

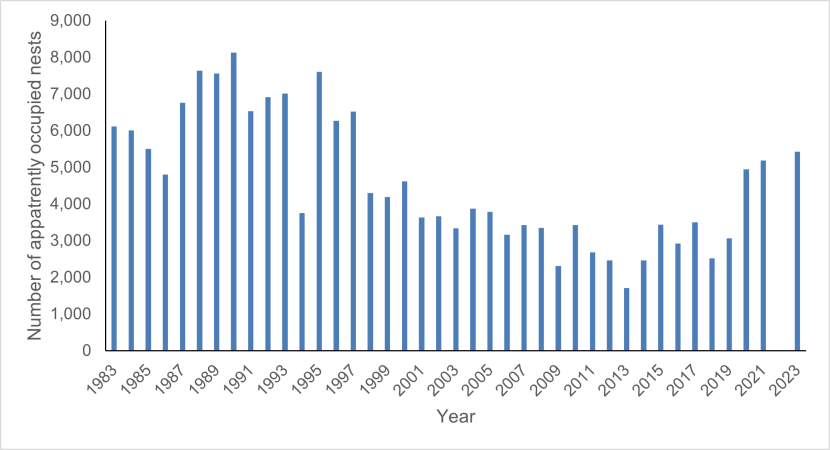

Bar chart showing the numbers of breeding kittiwake, apparently occupied nests, from 1983 to 2023, except 2022. Year is along the x axis, from 1983 to 2023, and number of apparently occupied nests is along the y axis, with a scale running from 0 to 9,000. Counts are quite variable and show an overall decline. A visual representation of some of the data from Table 9, which gives figures for fulmar, shag, cormorants, kittiwake, guillemot and razorbill.

The kittiwake population increased once again with 5,425 (AON) counted.

As usual, small numbers wintered around the island, but the large numbers did not return to the cliffs until late March. Thereafter, good numbers returned to the cliffsides and the return rate was calculated at 86%, average for the previous thirty years. Nest building commenced from 26 April, with the first eggs on 12 May. The first chicks hatched from 10 June and the first fledgling from 14 July. Productivity was calculated at 1.04 per nest, indicating another excellent breeding season, the fifth consecutive year the species has done well. Unlike recent times, only small numbers lingered off the south end, rather than the 1,000+ which we have become accustomed to in late summer. Small numbers were once again overwintering.

2.3.4 Guillemot (Uria aalge)

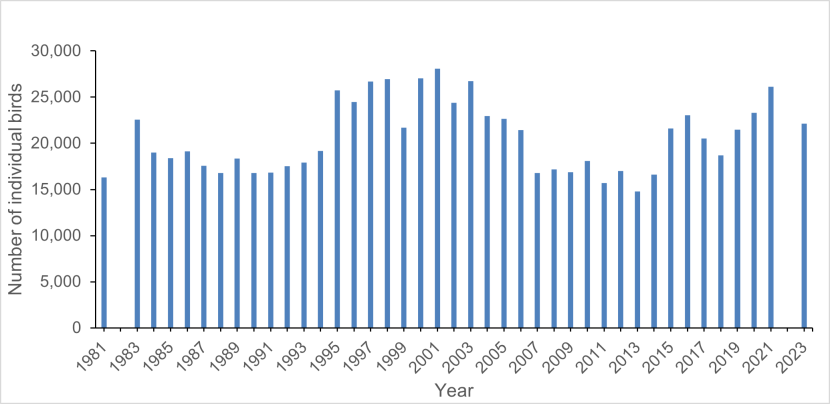

Bar chart showing the numbers of guillemot from 1981 to 2023, except 1982 and 2022. Year is along the x axis, from 1981 to 2023, and number of individual birds is along the y axis, with a scale running from 0 to 30,000. Counts are quite variable. A visual representation of some of the data from Table 9, which gives figures for fulmar, shag, cormorants, kittiwake, guillemot and razorbill.

Overall, the population counts revealed 22,113 individuals, with estimated breeding pairs of 15,314, down on the previous count.

Birds were attending the cliff ledges early in the mornings throughout January-March and eventually birds settled down on ledges from early April. Return rates were calculated at just 68%, the lowest ever in recorded history of data collection on the island. This was due directly to HPAI and an auk wreck which occurred the previous September-October, which saw high mortality of birds. The first eggs were discovered on 22 April and the first chicks hatched from 29 May. The first chicks started jumping from 19 June and the last was recorded on 6 August. Thereafter, birds were seen throughout the autumn in the surrounding waters of the island. Overall nesting productivity was 0.71 per pair, an average breeding season for the species.

2.3.5 Razorbill (Alca torda)

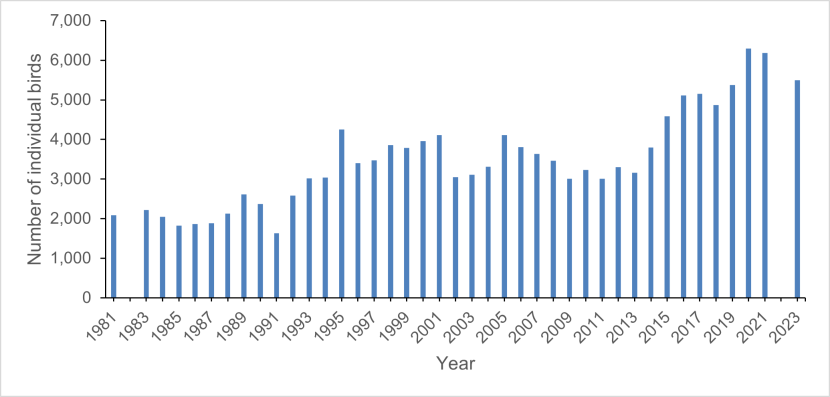

Bar chart showing the numbers of razorbill from 1981 to 2023, except 1982 and 2022. Year is along the x axis, from 1981 to 2023, and number of individual birds is along the y axis, with a scale that runs from 0 to 7,000. Numbers have been quite variable, with an overall upward trend. A visual representation of some of the data from Table 9, which gives figures for fulmar, shag, cormorants, kittiwake, guillemot and razorbill from1980-2023.

The population counts revealed a total of 5,493 individuals, with an estimate of 4,223 pairs (AON).

Birds started arriving in May waters from mid-February and gradually increased throughout March. Birds eventually settled, with copulation noted on 17 April. The return rate of adults surviving over the winter was 93%, which was above average and the fifth highest on record. The first eggs were discovered on 23 April. The first chicks hatched from 31 May, whilst the first chicks jumped from 20 June. As usual, the cliffs become quiet from early August, with the majority of birds gone to the open sea, with the last fledgling recorded on 4 August. Of all monitored chicks, 69% fledged, an average breeding season for the species.

2.3.6 Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo)

A total of 23 pairs nested, a record year for the island.

The species has not become established on the island, having first nested in 2020. The small colony on the north end of the island was once again occupied from mid-March, with the first incubating birds noted from 15 April. The first chicks hatched from early May and birds were in good attendance thereafter. Although not monitored, it appeared to be a very good breeding season, with large numbers of chicks fledging (43 fledged chicks counted on 28 June). Thereafter, the evening roost on Rona attracted 100+ nightly throughout the late summer/autumn.

2.4 Population monitoring of ground-nesting seabirds.

2.4.1 Puffin (Fratercula arctica)

As usual, huge numbers arrived in island waters in late March, with the first landfall made on 24 March, followed by vast numbers the following day. Over the following two weeks, observers noted lots of courtship displays and spring cleaning of burrows. Return rates were calculated at 74.4%, a low return compared to recent years, and the seventh lowest in recorded history. The first eggs were discovered on 12 April. The first birds carrying fish were seen on 21 May, indicating the first chicks had hatched. The chicks started fledging from 2 July and a late fledger was recorded on 24 August. Overall productivity indicated a success of 0.77 per nest, an average season for the species. The population was not counted this year, but an all-island count will be undertaken in 2024.

2.4.2 Herring and lesser black-backed gull

Herring gull (Larus argentatus)

Present all year round, with the winter numbers supplemented by birds from more northerly breeding populations in Scotland and Northern Europe. Birds were well established on breeding territories throughout April and nest building was noted mid-month. The first eggs were discovered on 27 April, with the first chicks hatching from 29 May. The population was not counted this year but will be counted next season. Chicks started fledging from across the island from 2 July and, as usual, small numbers remained throughout the autumn, with 400 counted on 27 October.

Lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus)

The entire island population moves south for the winter and the first returning birds were seen in mid-February with a single on 12 February. As spring progressed, larger numbers arrived across the colonies and the territorial disputes were noted in late March. The first eggs were discovered on 28 April, with chicks hatching by 30 May. The population was not counted this year but a count will be undertaken next year. Chicks started fledging from 4 July and thereafter numbers dwindled. The last confirmed record involved an individual in late October.

Gull management

Due to HPAI and with no terns nesting during 2023, there was no direct management of the large nesting gulls on the island. This will be reviewed for next year and dependent on the various circumstances of the breeding season.

2.4.3 Great black-backed gull (Larus marinus)

Present all year round with influxes of northern birds in the autumn. The island’s small population was on territory by mid-March; the first eggs were discovered on 15 April and the first chicks hatched from 17 May. The population was not counted this year but was approximately 150 pairs. The first chicks started fledging from the end of June. As usual, post-breeding numbers increased with the onset of the grey seal season as many birds took advantage of dead or dying pups as well as afterbirth in October-December. Evening roost counts of birds increased as a result, with over 400 noted in November.

2.4.4 Terns

Common tern (Sterna hirundo)

The first returning birds were seen on 24 April and aerial displays commenced soon after. The first egg was discovered on 30 May, but, as with the Arctic terns (see that species account), birds did not breed and there were no fledglings or population counts undertaken. Small numbers were seen on passage during the late summer, as they headed south from colonies elsewhere.

Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea)

It was the season to forget for the species, as there was no breeding attempt for the first time in several decades. Birds returned as usual from mid-April, with aerial displays undertaken from early May. However, the birds appeared distracted and were not settled, and there were various theories as to why the birds were not settling. Various factors might have played a part, as avian influenza might have been affecting them, the presence of nesting peregrines will have kept them on edge, whilst food availability dipped due to the marine heatwave at the end of May. This combination meant that birds did not settle despite the first egg being discovered on 19 May. As a result, there are no breeding data or population counts. Small numbers of birds would return to roost under the cover of darkness in traditional breeding areas but very few were recorded during the summer, with passing family parties from other colonies in August.

2.4.5 Eider (Somateria mollissima)

Small numbers overwintered around the island and gradually birds started increasing from late March. The main island Loch was the focal point in the spring as large numbers of displaying drakes were present with females. The first birds were seen nest prospecting from 12 April and the first sitting female was discovered in the Low Trap on 17 April. The first ducklings hatched from 11 May and thereafter good numbers of young were seen leaving the islands with large family crèches. Although the population was not counted this year, numbers appeared low on ground level, mirroring the reduced numbers which nested last year.

2.4.6 Storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus)

A full storm petrel survey was carried out using playback recordings, endoscopes and night vision cameras in the main area of the island, south of Fluke Street. Intensive effort was put in daily between 20-28 June and again in early July to establish the potential breeding population. Throughout the survey a total of 14 pairs were located calling, going down burrows or incubating eggs, which is the first population survey of its kind on the island. The species was only discovered nesting as recently as 2019 and further work will help establish further nest sites in the area.

2.5 Other breeding birds

2.5.1 Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus)

The island supports the only east coast breeding pair and birds returned to their traditional area in the north of the island from late March. Despite encouraging signs, with both adults returning and being present for the majority of the summer, there appeared to be no breeding attempt and the birds had gone by August. It was disappointing news and the hope is that the birds will return again next year with better success.

2.5.2 Shelduck (Tadorna tadorna)

As usual, the first birds arrived in late March and up to eight individuals were present, with pair bonding and displaying noted. Due to the secretive nature of their nesting behaviour (nesting underground), it is always difficult to assess the actual number of breeding pairs. It was considered that four pairs bred and a family party with 11 ducklings was seen leaving the island via the Loch on 6 June whilst another pair with eight young was seen near Tarbet on 16 June.

2.5.3 Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

During the early spring, two pairs were evident on the island favouring the Loch and it was obvious a breeding attempt would occur. Although the nests were not found, a female with ten ducklings was noted at Bishop’s Cove Pool on 30 April, indicating breeding success. Interestingly, a female with large young was seen on Rona in late June, suggesting that the female had managed to get some young to fledging stage, avoiding predating by the large gulls.

2.5.4 Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus)

Birds were present all year round, with approximately 20 pairs nesting across the island (no census this year). Displaying was noted from mid-April, with the first eggs discovered in early May. Plenty of young fledged nests and post-breeding counts included up to 40 across the island in early August.

2.5.5 Ringed plover (Charadrius hiaticula)

For only the second time in the island’s history, a breeding attempt was made. The species is usually a scarce visitor to the island, but from mid-March a pair were seen displaying around Kirkhaven. Eventually, a pair were discovered on the small beach incubating four eggs, but unfortunately, after nearly twenty days of incubating, were predated by a large gull. The pair remained in the area for several more weeks, but no further breeding attempt was made.

2.5.6 Feral pigeon (Columba livia (domest.))

The species remains a common resident, with breeding recorded throughout the year, with 500 counted in October.

2.5.7 Swallow (Hirundo rustica)

Another excellent year as birds returned to breeding areas from late April and breeding pairs were found at the Visitor Centre (2), the South Horn, Fluke Street freezer room, Fluke Street engine room and at the main lighthouse. All six pairs were successful in raising at least one brood, and four of these pairs fledged second broods, some as late as early October.

2.5.8 Rock pipit (Anthus petrosus)

This common resident was present all year round and although the population was not surveyed this year, the breeding population appeared healthy (20+ pairs). Pairs were spread across the island and large numbers of young fledged mid-summer.

2.5.9 Pied wagtail (Motacilla alba)

There was no census of the population this year, but good numbers were present throughout the summer, with successful breeding recorded. Breeding pairs utilised stone walls, buildings and natural nest sites as approximately 20 pairs nested, many producing two broods. As usual, the species departed the island with no overwintering individuals.

2.5.10 Carrion crow (Corvus corone)

Two pairs were present in the spring and although breeding was attempted by one pair (a nest was constructed on The Angel), the attempt failed for reasons not understood. Birds remained around all season, including ‘Patch’, the distinctive individual which has successfully bred on the island in recent years.

2.5.11 Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus)

For the second consecutive year, the pair nested successfully on the island in the same area as the previous season (on South Plateau). The birds were evident from March and vocal displays commenced from late March. During April, a clutch of four eggs was incubated and all four hatched. Prey items were very varied, from seabirds to migrant birds, and all four chicks fledged successfully from the nest in July. The family eventually dispersed to the nearby mainland in Fife during the autumn months.

2.5.12 Wood pigeon (Columba palumbus)

The first breeding wood pigeons for the island were recorded as recently as 2015 and have since established into a healthy population. As in recent years, a total of four pairs bred on the island and at least two of the pairs were ground-nesting, showing the variety of sites the birds can use. Breeding was protracted, with attempts during the autumn and at least four chicks fledged from various attempts/nests.

2.6 Migrant birds

The Bird Observatory opened its doors on 2 April and occupancy was excellent, with 1,074 occupied nights (maximum of 1,344 bed nights available). The only two weeks not occupied during the season included 2-8 April and 15-22 April. As usual, weather played a factor for groups arriving on the designated Saturday, especially towards the end of the season. The NatureScot team provided transport service of all kit and equipment across the island throughout the year. As usual, the bird observatory members concentrated on recording bird migration through daily census and bird ringing operations.

Since 2017, the Isle of May Bird Observatory Trust has implemented a full-scale replacement Heligoland trap programme, demolishing and replacing the four traps on the island. Three of the four traps had been replaced up to 2019, but due to the onset of Covid there was a halt to proceedings. This spring, the final trap, the Low Trap, was replaced and the construction will hopefully last for many decades to come. More information can be found on the Isle of May Bird Observatory website

An excellent season for migrants as the all-time year list record was broken, with 185 species recorded, eclipsing the previous record of 180 set in 2016. Most noteworthy highlights included:

1st - Pallas’s grasshopper warbler

1st - Spotted sandpiper

1st - Lesser whitethroat - confirmed eastern race

2nd - King eider

2nd - Pallid harrier

3rd - Great white egret

3rd - Smew

5th - Red-flanked bluetail

6th-7th - Blyth’s reed warbler

Other highlights and noteworthy birds included 4 Cory’s shearwater, Balearic shearwater, 5 Sabine’s gulls, 2 long-tailed skuas, 11 Leach’s petrels, 2 grey phalaropes, 2 olive-backed pipit and hoopoe alongside.

- Wryneck: Second consecutive year after a six-year gap

- Long-tailed skua: Recorded for only the 10th year involving 20 birds

- Red-breasted flycatcher: Recorded in 8 of the last 9 years

- Bluethroat: 8 records (7 spring and 1 autumn record)

- Red-backed shrike: 3 records (only 3 blank years in past 30 years)

- Marsh warbler: 2 records (recorded in 5 of the last 6 years)

- Barred warbler:

- Icterine warbler: 3 records

- Firecrest: 2 records

- Common rosefinch: (Only 1 blank year in past 30 years)

- Hawfinch: 2 records

- Little bunting: 4 in one day (record day count and first since 2020)

2.7 Mammals

2.7.1 Grey seals

The grey seal season was slow to start, with the first pup discovered on Rona on 3 October. Thereafter, there was a gradual increase as animals were born at Kirkhaven and Pilgrim's Haven by mid-October, with the main pupping areas becoming busy by the end of October. A full census using aerial images (from plane) were taken by the Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU) using three flyovers during the autumn months and the results will be released next year. The storms of mid-October (Babet and Ciaran) caused very few problems as the majority of pups are born in sheltered areas of the island or are moved further up the slopes of the island beyond the reach of the sea in these extreme weather events. As usual, the season ended in mid-December, with late pups born in early January.

2.7.2 Cetaceans

It was a great season for cetacean sightings (cetaceans are aquatic mammals that include whales, dolphins, and porpoises). A total of seven species were recorded in the surrounding seas, representing the highest number of species in two decades. Annual cetacean counts typically return only 3-4 species, with minke whale (16 out of the last 17 years), harbour porpoise (15 out of the last 17 years) and bottle-nosed dolphin (12 out of the last 17 years) the island’s most regularly reported species. The month of August proved to be the most productive, with sightings on 25 days, followed by September, with sightings on 23 days.

Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata)

This season, it was the most frequently sighted cetacean (seen on 33 days) and typically most were seen during August (15 days) and September (7 days). The first of the year was noted in early May and then every month into October. The largest number seen included three in August and September. Interestingly, an individual was seen breaching on 9 June as well as on 5 August.

Harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena)

There were reports on 28 dates across the season, with the most frequent including August (8 dates) and September (7 dates). Sightings began in March and ended in late October, with no recorded sightings in June. The largest number of animals involved a pod of six on 10 August.

Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus)

Two animals were recorded off the west side of the island on 12 September, having been seen off Fife Ness earlier in the day. Both animals remained in the area for a further five days and were seen off the south and east end of the island. Interestingly, one animal was seen ‘logging’, a resting behaviour where cetaceans rest at the surface and appear like ‘logs’. The final sighting involved just a single animal on 18 September. The majority of Risso’s dolphin sightings come from the west coast of Scotland and Outer Hebrides as they tend to feed on fish and squid in deep waters along the continental shelf. This was the first record of the animals around the island since 2011.

Bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

The species is frequently seen along the Fife coastline and reported by boatmen throughout the summer, but these animals are just outside our recording area. The species is much rarer around the island and reports were received on only five dates, with a single in May and four in September. The largest number of individuals seen was a pod of five on 9 September.

Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)

An individual was seen surfacing only 20m from the May Princess boat off the south end of the isle on 4 May. The animal remained in Isle of May waters for a further 12 days and was seen on several occasions during this time, especially off the north end. Reports are increasing from the island as there have been records in 2015, 2018 and 2022.

Common dolphin (Delphinus delphis)

One of the real highlights of the summer involved a pod of 60 animals frantically working together, fishing off the east side of the island on 25-26 August. This large pod remained for two days and showed well on occasions. There are only a few records from the island, and this was the first since two animals were recorded in 2016.

Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis)

On only the second ever occasion, this species was sighted off the Isle of May. During a feeding frenzy off the north end, an animal was recorded on 5 September and had been present for several days off Crail, but this was the only time it was seen from the Isle of May. This represents the second ever record following one off the south end in 2021.

2.8 Lepidoptera

2.8.1 Butterflies

It proved to be a good year, with twelve species recorded on the island from March until October. This is the second highest annual species count after thirteen were logged in 2010, as usually 9-10 species are seen annually. The seven most common species included red admiral, small tortoiseshell, small white, large white, green-veined white, peacock and painted lady butterflies. These seven species of butterfly have been recorded every year since 2007, excluding 2020 when no staff were present on the island due to Covid-19.

Highlights for the season included a holly blue in July, which represented the first ever island record. Speckled wood was first recorded as recently as 2017 but has now been recorded in four years since, including an individual in June. A similar pattern has occurred with wall brown, as the first island record occurred in 2018, but the species has been seen in five years since, including records in July and August. Small tortoiseshell were seen in every month from March, followed by red admiral and peacock, seen across five months. Red admiral was the most frequently occurring species as it was present on 101 days (including 4,000 across the island in mid-August), followed by small tortoiseshell, present on 50 days, and peacock, present on 22 days.

2.8.2 Moths

Moth trapping at Fluke Street took place on 65 nights between 30 April and 18 September, with the Skinner MV light trap being set up in the garden of the principal keeper’s cottage and moved under shelter on wet nights. A total of 128 species were identified over the season, comprising 4,012 individual specimens. Bright-line brown-eye was the most frequently occurring species, present on 44 occasions, followed by large yellow underwing, present on 40 nights, and dark arches, present on 38 nights. Marbled coronet was the most abundant species, with a total of 633 specimens counted, followed by dark arches with 386 specimens and large yellow underwing with 379.

Most noteworthy records during the season included a swallow prominent (Pheosia tremula), recorded for the first time on the island. The red-necked footman (Atolmis rubricollis) was an island second, last seen in 2006. The third record of the swallow-tailed moth (Ourapteryx sambucaria) was noted and last seen in 2006. One of the big highlights was the discovery of two convolvulus hawk-moths (Agrius convolvuli) in September, which had only been recorded on three previous occasions. The final noteworthy highlight included three latticed heath (Chiasmia clathrata) trapped this year, with only two previous island records.

|

Species |

Number of nights |

Total caught |

|---|---|---|

|

Bright-line brown-eye |

44 |

288 |

|

Large yellow underwing |

40 |

379 |

|

Dark arches |

39 |

387 |

|

Silver Y |

37 |

121 |

|

Black-headed conch |

36 |

124 |

|

Campion |

29 |

149 |

|

Marbled coronet |

26 |

633 |

|

White-line dart |

24 |

194 |

|

Garden grass veneer |

23 |

358 |

|

Lime-speck pug |

22 |

89 |

3. Research and monitoring

3.1 Research teams

As usual, research teams were based on the island throughout the year, studying various aspects of the island’s flora and fauna. The teams spent a total of 737 bed nights on the island, showing the importance of the island for research. During the summer months, the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH), led by Francis Daunt with field manager Mark Newell, were present from 19 April until the end of July. The team included new assistant Josie Hewitt with support from several other people including Mike Harris, Ella Benninghaus, Erin Taylor and Sarah Burthe amongst others. The British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), led by Gary Clewley, worked on the large nesting gulls during the spring, whilst Edinburgh University, led by Emma Cunningham, had a team of four present throughout the summer months looking at HPAI and European shags. During the autumn months, Manchester and Edinburgh University worked together on the island’s mice, and they were based in Fluke Street from 4 November until 11 December. The only other group to undertake studies involved the Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU) from St Andrews, who were present for two weeks from 10 November, their first time back on the island in five years.

A summary of research work undertaken is in ANNEX 2, with the main projects detailed below:

- GPS tracking of Isle of May seabirds to assess effects of offshore renewable developments, led by Dr Francis Daunt

- Overwintering foraging ecology of seabirds, led by Dr Francis Daunt

- Understanding the disease ecology of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in large gulls, led by Prof. Karen Spence

- Assessing the impact of environmental chemicals (ECs) on seabird development and health, by Laura Kamp

- The impact of legacy waste contaminants and parasitism on seabirds, led by Dr Francis Daunt

- Isle of May long-term seabird studies, led by Dr Francis Daunt

- Measuring the interaction between large gulls and offshore wind farm development zones through telemetry, by Gary Clewley

- Disease susceptibility and gut health in the wild - house mice: determining interactions between diet, gut microbiome, and immunity, led by Prof. Kathryn Else

- Evolutionary genetics of grey seal reproductive behaviour and maternal investment, led by Dr Kelly Robinson

4. Visitor review

After three years of disruption due to Covid-19 and HPAI, the island experienced its first full visitor season since 2019. The island opened its doors on 1 April and remained open until 30 September, with planned closures one day per week in the months of May and June, whilst, as usual, bad weather curtailed sailing on several dates.

The visitor boats departing from Anstruther brought the majority of visitors, with the May Princess bringing 11,470 visitors (7,446 last year) whilst the fast RIB Osprey carried a further 1,655 visitors (1,169 last year). During the season, boats travelled from the Lothian side of the Firth of Forth, with the Seabird Centre RIB bringing 1,417 visitors (862 last year) and BlueWild a further 616 visitors (138 last year). Small private leisure craft, cruise ships (two) and kayaks carried a further 443 visitors, bringing the annual total to a new record of 15,603 people compared to 9,656 the previous year.

Despite poor weather at the start of the season and in July, the annual total was a new record for the island, eclipsing the previous best of 14,248 in 2019. All four boats broke their own records for the number of passengers carried during the season.

|

Month |

May Princess |

Osprey RIB |

Seabird RIB |

BlueWild |

Others |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

April |

1,404 |

257 |

219 |

7 |

8 |

1,895 |

|

May |

2,270 |

299 |

269 |

128 |

201 |

3,167 |

|

June |

2,534 |

306 |

295 |

184 |

184 |

3,503 |

|

July |

2,620 |

318 |

261 |

132 |

25 |

3,356 |

|

August |

2,022 |

332 |

275 |

131 |

25 |

2,785 |

|

Sept |

620 |

143 |

98 |

34 |

2 |

897 |

|

Total |

11,470 |

1,655 |

1,417 |

616 |

445 |

15,603 |

|

Year |

May Princess |

Osprey RIB |

Seabird RIB |

BlueWild |

Others |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2023 |

11,470 |

1,655 |

1,417 |

616 |

445 |

15,603 |

|

2022 |

7,446 |

1,169 |

862 |

138 |

41 |

9,656 |

|

2021 |

7,981 |

1,280 |

1,043 |

98 |

152 |

10,554 |

|

2020 |

2,466 |

328 |

390 |

10 |

93 |

3,287 |

|

2019 |

11,551 |

1,474 |

984 |

0 |

239 |

14,248 |

|

2018 |

11,112 |

1,373 |

1,029 |

19 |

221 |

13,754 |

|

2017 |

10,385 |

1,349 |

798 |

112 |

251 |

12,895 |

|

2016 |

9,830 |

1,327 |

743 |

0 |

164 |

12,064 |

|

2015 |

8,803 |

1,219 |

669 |

0 |

238 |

10,929 |

5. Media coverage

The Isle of May appeared regularly on various media outlets throughout the year. BBC Radio Four interviewed Reserve Manager David Steel on 1 April with an upbeat story about puffins whilst local newspaper The Courier ran several island-related stories during the year, including the opening of the island on 1 April. During the summer, BBC Radio Four, with presenter Karine Polwart, produced a thirty-minute interview as part of the ‘Seek the Light’ series which featured the Arctic terns of the island. Other interviews were conducted with BBC Scotland Aberdeen regarding the plight of the seabirds during the HPAI outbreak and BBC producer Richard Taylor-Jones filmed the nesting auks of the island. Social media was again very popular, with the island’s blog attracting a record of 105,051 hits by 46,647 visitors. Overall, 104 different blog posts were uploaded highlighting the work done on the island. Facebook remained popular, with 5,500 people following the page.

6. Volunteers and support

The island’s long-term volunteer programme increased as three members were taken on for the busy summer months. The team included volunteers on long-term placements Andrew Shaw (4 May-10 August), Rachel Davey (15 May-19 September) and Finley Dennison (24 May-22 September), who contributed significantly to the island with a total of 260 working days and without their help the island would not operate.

As usual, our local NNR teams helped during the season: the Tentsmuir NNR team helped rebuild damaged stone walls in early April; the Loch Leven team helped open up and prepare the island for visitors in late March; and staff from local reserves helped pack down the island and remove rubbish in early October. Other help was most welcome during the season from a number of people including Laura Kamp, Simon Ritchie, Caroline Gallacher, Clara Menche, Bob Ritchie and Liz Morgan.

7. Infrastructure and island work

As usual, various island work was undertaken during the season, dependent on the weather and the seabird breeding season. Noticeable jobs this year included the conversion of the wall at the Rona crossing to a seating area; the replacement of old decaying benches with two new recycled plastic picnic benches; stone walls rebuilt following winter seal damage; the boardwalk extension on Holyman’s Road; the rebuild of the South Plateau steps.

On a large scale, the Low Light tower and Beacon were painted, with the North and South Horns programmed for painting in the early spring. Water was an issue, as the dry spring resulted in water shortages in the main well near the Visitor Centre. The well was almost dry by the end of June and remained that way until early October.

8. Activities around the island

8.1 Boat activity around the island

During the months of June and July, other boat activity was recorded around the island, but it is important to note that this was based on incidental sightings, recorded by varying numbers of island residents while engaged in other tasks, and is by no means a complete record of all boat activity in these months. Despite this, a total of 127 incidences of boats using Isle of May waters was recorded in June and July 2023, with over half (64) being commercial users, the vast majority being creeling boats for lobster and crab.

On Monday 3 July, the impressive RRS Sir David Attenborough sailed past the north end of the island on its way north. The ship is a polar research vessel for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and has been visiting Scotland for the first time. It had been up the Firth of Forth at Rosyth for maintenance and was heading to do some dynamic positioning and moon pool trials.

8.2 Wind farm installation

The wind farm east of the Isle of May, Neart Na Gaoithe (meaning ‘Strength of the Wind’ in Gaelic), has been under construction since August 2020. Since that date, industrial ships and heavy plant material have been ever-present on the horizon, working throughout the year. Most of the work in this time has been underwater as ground preparations, cable laying and foundations have been the main focus. The wind farm will eventually consist of 54 turbines covering 1,052 kms with a potential of producing 450 megawatts (450 million watts), which will be enough to power 375,000 homes. On Wednesday 19 July, the first turbine was erected and the project is expected to be complete by early next year.

9. Weather

The Isle of May experiences all weather systems during the year and some of the most noticeable this season included the arrival of snow in early March. Snow is rarely recorded on the island, with the previous occurrence being in February 2021, which brought a lot of woodcock to the island as birds escaped the frozen mainland. Prior to that, in March 2018 heavy snow drifted and settled across the island as part of the ‘Beast from the East’. The spring (April and May) were dominated by easterly winds and rainfall was low, resulting in water shortage issues in the island’s wells later in the season. The months of July and August were interchangeable, with spells of wet weather, whilst the autumn was dominated by easterly storms, especially October. These storms included Storm Babet and Storm Ciaran, which brought huge seas in early October (the wave buoy indicated wave heights of 13.3m on occasions) and caused damage to the east side of the island, especially around the jetty systems.

Annex 1: Seabird Data

You can download this information in the spreadsheet at the foot of the page.

Annex 2: Research project summaries

1. GPS tracking of Isle of May seabirds to assess effects of offshore renewable developments

UKCEH - M Newell, E Benninghaus, J Hewitt, E Taylor & F Daunt

Neart na Gaoithe offshore wind farm are undertaking GPS tracking of Isle of May seabirds as part of their post-construction environmental monitoring programme signed off by Scottish Government. They have contracted UKCEH to undertake the work. This study will undertake GPS tracking of kittiwakes, puffins, guillemots and razorbills to quantify distribution on foraging trips, overlap with wind farm footprints and, together with work in later years during wind farm construction and operation, the potential impact of these developments on SPA breeding birds in the region. In 2023, we successfully deployed GPS devices on 25 guillemots, 50 kittiwakes, 27 puffins and 17 razorbills. The data from these deployments will inform on the usage of the Neart na Gaoithe wind farm area by these seabirds.

2. Long-term studies of breeding seabirds on the Isle of May

UKCEH - M Newell, M Harris, J Hewitt, E Taylor, S Burthe, E Benninghaus & F Daunt

The late winter period was fairly benign and the commencement of breeding in 2023 was at a normal date for most species but particularly early for European shags. However, it was clear that common guillemot had been severely hit, with the return rate of individually marked birds at the lowest point on record, with Atlantic puffins also at a low level. During the breeding season, fieldwork on the Isle of May was able to commence on time and using usual protocols. Although there were signs of the return of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in several seabird species, fieldwork was able to continue throughout the season by following careful measures to avoid any transmission risks. Ultimately, mortality on the Isle of May was only observed to be above normal levels for black-legged kittiwakes, although this did not appear to severely affect their breeding performance.

The 2023 season proved a fairly productive year amongst the main study species despite the presence of HPAI. With UKCEH researchers present on the island continuously for three and a half months, the cliff-nesting seabirds could be monitored on a daily basis, allowing the exact timing of any failures and effects of extreme weather to be recorded. As widely reported, sea temperatures were well above normal levels throughout most of the breeding season, but this did not appear to adversely affect productivity in most study species. Light winds dominated the season and it was exceptionally dry, meaning breeding attempts were unaffected by the weather. However, the post-fledging period in 2023 appears to be tough going, particularly for common guillemots, with widespread reports of abnormal behaviour and high mortality. Although testing has been somewhat limited, it appears that HPAI is not the primary cause and the signs are very similar to the 2021 post season mortality event when starvation was noted in most individuals examined.

Breeding success of razorbills, European shags and black-legged kittiwakes was above the long-term average, whereas common guillemots and Atlantic puffins were average and fulmars had a below-average breeding season. Return rates were above the long-term average for European shags, black-legged kittiwakes and razorbills, while Atlantic puffin were below average and common guillemots the lowest on record.

The main species-specific results were:

- Northern fulmar breeding success (0.36 chicks per incubating pair) was below average and the lowest since 2012.

- European shags had a successful season (1.81 chicks per pair). Adult return rate at 85.7% was above average.

- Black-legged kittiwakes had an above average breeding season (1.04 chicks per completed nest). Adult return rate (86%) was above average.

- Common guillemots had an average breeding season (0.71 chicks leaving per pair laying). Return rate of adults (68%) was the lowest ever.

- Razorbills had an above average breeding season (0.69 chicks leaving per pair laying), but the adult return rate (93%) was high.

- Atlantic puffins had an average breeding season (0.77 chicks per pair laying). The return rate for adults (74.4%) was poor, with only six lower years.

3. Overwintering foraging ecology of seabirds

UKCEH - M Newell, M Harris, S Burthe, E Benninghaus, J Hewitt, E Taylor, S Wanless & F Daunt

This project aims to obtain fine-scale data on movements and foraging behaviour of seabirds in winter, by attaching specially designed loggers to European shags, Atlantic puffins, black-legged kittiwakes, razorbills and common guillemots. The loggers record daily location and foraging effort. Detailed data on location-specific foraging effort of seabirds will enable patterns of distribution and behaviour in relation to season and breeding status to be analysed.

The work on shags is a continuation of work commenced in 2002. A total of 18 geolocator loggers were retrieved from shags, with a further 16 deployed which we plan to retrieve in 2024. Two further geolocator loggers were retrieved from shags which died in autumn 2023 in storms. In 2023, 16 retrievals of geolocator loggers were made from guillemots, with a further 20 deployments. In 2023, 20 loggers were deployed on puffins, with 5 retrieved from previous deployments. Of these, one was retrieved from a dead puffin which had been predated by great black-backed gulls in an area of over one hundred predated puffins. These deployments will be targeted for retrieval in 2024. A total of 17 loggers were retrieved from kittiwakes in 2021 which had been deployed in previous years. A further 20 new deployments were made.

4. The impact of legacy waste contaminants and parasites on seabirds

UKCEH - F Daunt, M Newell, F Greco, E Benninghaus, F Ruiz-Raya, J Hewitt, E Taylor, E Cunningham & S Burthe

Seabirds in the Firth of Forth are under pressure from multiple stressors. Contaminants and parasites are two such stressors known to have detrimental impacts on hosts and which may interact through modulation of immune function, with negative consequences on individuals and, in turn, populations. Understanding why some individuals are more contaminated or parasitised than others and how these two drivers interact is vital for understanding impacts on individual fitness and population dynamics. A period of observational work to establish apparent laying dates and identify adults commenced in late April. Sampling work commenced on 9/5/23 and continued until 16/7/23. No endoscopy was carried out in 2023. From a total of 81 broods, 211 chicks were dosed with either anti-parasite drug or a control saline solution. Efforts will be made over the coming winter to resight these colour-ringed individuals in order to understand their movements. A total of ten shags were caught and ring mounted GPS devices deployed. These will collect data through the winter months with the aim of retrieval in 2024. Data will be analysed over the coming months and inform plans for 2024.

5. Isle of May non-breeding season shag resightings

UKCEH - M Newell, M Harris, S Burthe, S Wanless & F Daunt

Seabirds in the Firth of Forth are under pressure from multiple stressors. The effects of these stressors are important during the non-breeding season when most mortality of seabirds takes place. Contaminants and parasites are two such stressors known to have detrimental impacts on hosts. Increasing quantities of contaminants originating from land are found in coastal marine food webs, especially in locations with high human population density and long industrial histories such as the Firth of Forth. Seabirds foraging in these regions are potentially exposed to high concentrations through food ingestion, and European shags (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) are likely to have particularly high exposure because of their coastal distribution in proximity to sources of contaminants. Accordingly, results from past work show that Isle of May shags have very high levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane metabolites (DDTs), perfluoroalkyl compounds (PFAs) and mercury.

However, the demographic consequences of these chemicals are unknown, and there is increasing concern about emerging contaminants such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products and microplastics. Shags are also heavily parasitized with endoparasitic worms, and we know that these parasites impact behaviour and reproductive performance. Understanding the effects of contaminants and parasites requires a detailed understanding of a bird’s exposure outside the breeding season. Exposure is closely associated with migration strategy – some individuals remain resident on the Isle of May and others migrate to other locations where environmental concentrations of contaminants and parasites may differ. This variation in exposure could in turn have consequences for the survival and subsequent breeding performance of residents and migrants, which is vital to quantify in order to understand the effects on the dynamics of this declining population. Accordingly, we wish to obtain resightings of colour-ringed individuals throughout the non-breeding season on the Isle of May, as part of a wider programme of resightings taking place in eastern Scotland encompassing the wintering range of this population. We will then relate migration strategy to breeding success and survival at the individual level to understanding the demographic consequences of these stressors on this population. We also wish to collect pellets outside the breeding season to obtain an estimate of diet, which will be used to inform estimates of exposure through ingestion of different prey.

This work is funded by a Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Highlight Topic grant on Legacy Waste in the Coastal Zone. In the winter of 2022/23, a total of 5373 observations were made of 1429 individual colour-ringed shags on the Isle of May. This impressive total will form an invaluable analysis along with the sightings of shags made from the mainland over the same period. It is hoped that a similar number of observations will be made in the winter of 2023/24.

6. Isle of May mouse research

University of Manchester and University of Edinburgh

The Isle of May is home to a single species of rodent, the house mouse, or Mus musculus domesticus. Usually found in close proximity with humans, the Isle of May house mice seem to be a hardy population, surviving on an island which has not seen continuous human habitation for decades. The mice are spread across the island living in rocky cracks, their own burrows and potentially sharing burrows with puffins and rabbits. Undergoing severe population crashes each winter, from several thousand in autumn to several hundred in spring, these mice offer an incredible opportunity to study what shapes their physiology in a fully natural setting.

A collaborative team from the University of Manchester and the University of Edinburgh have been funded by the BBSRC to carry out a three-year project working with the wild house mouse population on the Isle of May. The Isle of May mice are naturally infected with a parasitic whipworm that lives in the gut, and the way the immune system responds to this infection is key to disease progression and relevant to human populations affected by the human species of whipworm. One of our major knowledge gaps is how a beneficial immune response can be supported to allow the individual to get rid of the infection. The aim of the project is to understand how diet and the microbiome – the bacteria that live in the gut – shape the immune response to whipworm infection.

In order to meet this aim, the team had a first six-week-long field trip to the Isle of May in November 2023, live-trapping mice across two independent sites on the Isle of May, one near the Low Light and one near Fluke Street. One of those grids was supplemented with an overall highly nutritious mouse diet using feeders with small, mouse-sized entry holes, whilst the other grid was not provided with any additional nutritional supplementation.

Measurements and samples of individual animals were recorded across multiple captures over time, to follow any changes in physiology and whipworm infection levels between the two grids. In order to take into account how different seasons may affect infection levels, diet and the microbiome of these house mice, the team will perform field trips in late summer when the population is expanding, and early winter when it is declining, across several years. The goal by the end of the project is to have disentangled the ways in which an improved diet supports health and wellbeing and protects against parasitic infection in the real-world environment in which the immune system operates, with the help of this uniquely isolated population of house mice on the Isle of May.

7. Grey seal study

Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU)

Three areas of study undertaken during the autumn months looking at the evolutionary genetics of grey seal reproductive behaviour and maternal investment, ground truthing of air survey images for population counts and looking at the dispersal of grey seal weaners from a breeding colony.

The work looked at the genetics of pinniped evolution and life history strategies, focussing on lactation performance and duration. This involved examining gene expression in blood, milk and blubber using an observation team which took samples from adults and pups under licence. Further studies looked at flying a drone over a group of breeding animals concurrent with scheduled fixed-wing aerial survey flights to ground truth air survey images and subsequent counts. The final part of the work involved tagging weaners to follow their movements once they leave the colonies and how their at-sea behaviour changes in early life.