Definition of a Wildcat - Updated Guidance

Version: 9 August 2023

The reliable identification of wildcats (Felis silvestris) is necessary to enable the protection of the species and to ensure land managers, animal welfare organisations, conservation practitioners and others operate within the law. Wildcats are protected in a number of ways. For example, it is an offence to deliberately or recklessly capture, injure, kill or harass wildcats, disturb them in a den or to damage or destroy their breeding sites or resting places.

However, feral domestic cats (Felis catus) are an invasive non-native species. Therefore, releasing a feral domestic cat requires a licence, irrespective of whether it is neutered or not. Land managers are allowed to use appropriate lethal methods to control feral domestic cats.

Here we summarise the pragmatic, practical approaches we use to define wildcats when providing advice and making licensing decisions.

Cat identification – the two main methods

Identification can be complicated because wildcats have a significant history of hybridisation (interbreeding) with domestic cats. This has been happening for several decades (Howard-McCombe et al. 2021), and has led to the development of a hybrid swarm (a single population of cats in the wild that form a genetic and morphological continuum from wildcat to domestic cat). However, wildcats with a small amount of domestic cat ancestry still have value for wildcat conservation in Scotland. That is because there are almost certainly no individual cats remaining in the wild in Scotland that have no history of hybridisation.

There are two approaches to identifying wildcats, and at the end of this webpage, we describe how we use them in different situations.

The first method relates to their external appearance and the use of a ‘pelage score’ developed by Kitchener et al. (2005). This method gives a score of between 1 (domestic cat trait) and 3 (wildcat trait) for seven key pelage or coat patterns. Individuals that score 19 or more for the resulting pelage score (called the ‘7PS’ score) are classified as a wildcat. This is a score we aspire to in wildcat conservation, but the level of hybridisation that exists in the wild in Scotland means that the vast majority of animals considered to be of conservation value as wildcats have lower pelage scores (see the table below). For conservation management purposes in the field, we use a lower pelage threshold as described in the table below. See Annex 1 for photos of cats considered to be of conservation value as wildcats and Annex 2 for more details on the pelage score. In wild populations with limited levels of hybridisation, these pelage traits are highly correlated with skull characters, cranial volume and intestinal length, which together define a wildcat, however it is likely that there will be much lower correlations in populations which have experienced hybridisation for a longer time.

The second method uses a genetic test that evaluates the proportion of wildcat ancestry (Q) in an individual, from 0 (domestic cat) to 1 (wildcat). The value of Q is an estimate, which ranges from a lower boundary (LBQ) to an upper boundary (UBQ) based on a statistical calculation. During the Scottish Wildcat Action project we agreed with partners that for a cat to be considered a wildcat then the LBQ should be greater or equal to 0.75, i.e. we have a high certainty that it has at least 75% wildcat ancestry and therefore it “passes the genetic threshold”. The genetic analysis underpinning hybridisation is a technical subject and further details of the test can be found in Senn and Ogden (2015) and Senn et al. (2019), and in Annex 3 below.

Genetic and pelage tests are two different approaches that provide assessments of whether a cat is a wildcat. However the relationship between the genetic and pelage tests is not simple. Firstly, the two measures are very different in nature, one is a continuous measure (the genetic score estimates the % of wildcat genes in an animal’s genome) and the other is an index (the pelage score is an amalgamation of scores from seven different nominal categories, each scored on an ordinal scale of 1-3). Secondly, wildcat genomics (like the genomics of many species, even humans) is still a developing scientific discipline. Because we do not yet have a full understanding of the wildcat genome, we do not yet fully understand the genetic control of lots of different traits including pelage and other morphological characters. Wildcat pelage characters are likely to be under the control of a relatively small number of genes, some of which may interact with each other in complex ways. Despite gaps in scientific knowledge over how the two relate to each other, the genetic and pelage score do still both tell us different pieces of information about wildcat genetics and therefore we use both in combination where possible. However, there are circumstances where, because of practical necessity, we can only use one or another (see below). Genetic analysis methods are continually developing and, in line with this, we are continually working to improve our understanding of wildcat hybridisation

Cat identification – the range of situations

The amount and types of information available to help distinguish wildcats from domestic cats and their hybrids is highly dependent on the situation in which the animals are observed. Assessing the 7PS pelage score of an animal can be difficult to do in wild situations. Gamekeepers viewing a cat from a distance, or even in a cage trap, will probably have only a partial view of the animal’s pelage. At the opposite end of the spectrum, practitioners working with a cat held in captivity for any length of time, such as during some stages of a conservation breeding programme or where a cat is being rehabilitated, will have more opportunity to view the cat’s pelage and obtain genetic samples either directly from blood taken for disease and health screening or indirectly from scats and/or hair samples. In between the ends of this spectrum, there will be practitioners with detailed camera-trap images, or short-term access to a sedated cat on a veterinary table or in fieldwork conditions, who may not have an opportunity to run genetic tests, but will be able to take a closer look at the pelage or take photos for later assessment.

The other consideration is the experience of the observer(s) in using physical features to assess cats. For example, individual gamekeepers or veterinary clinicians, however highly experienced and knowledgeable about animals and wildlife, are unlikely to have a detailed knowledge of the wildcat pelage scoring system and may not have the time or opportunity to ask for expert advice.

A situation-specific description of a wildcat

A contextual approach to describe wildcats is provided in the table below based on the methods taken by the Scottish Wildcat Action project that ran from 2015-2020, and updated following consultation with experts and key stakeholder groups during the Saving Wildcats project. The criteria use both the pelage scoring system and the genetic scoring system.

These pelage and genetic tests are from peer-reviewed, published science (Kitchener et al. 2005; Senn et al. 2019) and are widely accepted methods for identifying wildcats applied by NatureScot and other key partners. We apply this approach when giving advice and for those situations where licensing is relevant.

This method takes into consideration the situation of the assessor and what opportunities they may have to obtain information for the assessment, as well as the experience and knowledge of the practitioner in making the assessment.

Throughout, a precautionary approach should be taken: if in doubt, assume the cat is a wildcat. Doubt, in this context, is where there is a lack of information or experience to make a confident and accurate assessment following the criteria set out below. Remember that wildcats are protected from, amongst other things, ‘reckless’ killing or harassment. Failure to follow the precautionary approach set out below may be regarded as ‘reckless’.

We will, in discussion with our partners, regularly review and, where necessary, update this approach as we continue to collate more information and gain more experience with wildcats and practical wildcat issues.

Table 1: Situation-specific descriptions of a wildcat

|

In what situation should the assessment method be used? |

Assessment method |

Assume the animal is a wildcat of value to conservation: |

|---|---|---|

|

Where pelage markings are not visible, such as:

|

N/A |

Until further information can be collected (e.g., using camera traps or daytime sightings) |

|

Where a detailed pelage assessment is not possible, such as in the following situations:

|

Pelage - descriptive |

If a cat with ALL of the following features:

and WITHOUT the following features:

Note that the bluntness of the tail tip can vary with the seasons, age, dampness of fur, etc. This feature should be used with caution.

If it is not possible to see all of these features clearly, but visible features match the description above, then assume it is a wildcat.

|

|

Where there is insufficient opportunity for genetic testing, but a good visual examination of the animal is possible (e.g., for camera trap images, or during an assessment of a sedated cat, with someone knowledgeable in the pelage scoring method), such as:

(*Opportunities for taking genetic samples for later testing to support research should be discussed with NatureScot) |

Pelage score only |

If Pelage score is ≥17

|

|

Where genetic samples are obtainable, but pelage assessment is not possible, unreliable, or where there are practical constraints associated with essential conservation actions such as for:

|

Genetics score only |

If Genetic score LBQ is ≥0.75 |

|

Where a detailed pelage assessment of the cat is possible (e.g., a preserved specimen or a dead or sedated cat under good, well-lit conditions, with someone trained in pelage scoring) and there is the opportunity and time to obtain genetic samples and run a genetic test.

This will include (but not be restricted to):

For full details see the pelage and genetic scoring decision matrix on page 33 of Senn and Ogden (2015), also provided in Annex 4. This also details how cases that fall outwith the criteria given in the right column should be handled. |

Combined genetics and pelage scores |

If Genetic score LBQ is ≥0.75 and Pelage score is ≥16 OR Genetic score Q is ≥0.75 and Pelage score is ≥17 OR Genetic score UBQ is ≥0.75 and Pelage score is ≥18 |

Appendices

Annex 1 - Images of typical wildcats

Annex 2 – Pelage scoring

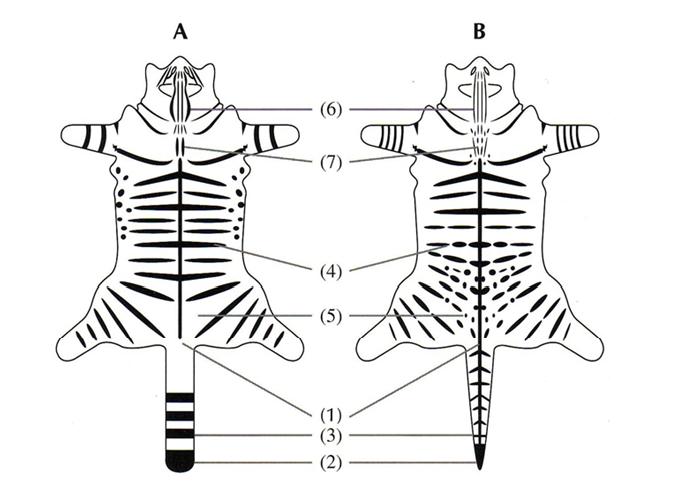

Note that there is variation in the markings between wildcats and so this drawing should not be taken as an exact description. For example, not all wildcats will have exactly four tail bands with a lack of markings towards the base of the tail. Details on the seven pelage characters and how they score are provided in the table below. Adapted from Kitchener et al. (2005).

Table 2: Scores for the seven pelage characters modified from Kitchener et al. (2005), where a score of 1 indicates a domestic cat trait, 3 indicates a wildcat trait and 2 indicates an intermediate trait indicative of a hybrid.

|

No. |

Character |

Domestic cat trait (Score 1) |

Intermediate trait (Score 2) |

Wildcat trait (Score 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Extent of dorsal line |

Absent / covers entire tail |

Continues onto tail |

Stops at base of tail |

|

2 |

Shape of tail tip |

Tapered to a point |

Intermediate |

Blunt |

|

3 |

Distinctness of tail bands |

Absent / joined by dorsal line |

Indistinct or fused |

Distinct |

|

4 |

Broken stripes on flanks |

> 50% broken / no marking |

25–50% broken |

< 25% broken |

|

5 |

Broken stripes on hindquarters |

> 50% broken / no marking |

25–50% broken |

< 25% broken |

|

6 |

Stripes on nape |

Thin / no stripes |

Intermediate |

4 wavy thick stripes |

|

7 |

Stripes on shoulder |

Indistinct / no stripes |

Intermediate |

2 or 3 thick stripes |

Annex 3 – Genetic scoring

The genetic test is fully described in Senn and Ogden (2015) and Senn et al. (2019), with further evidence presented in relation to its accuracy in Howard McCombe et al. (2021). The test uses an array of 35 Short Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), selected because they showed good ability to differentiate between domestic cats and wildcats. Once the genetic test has been run, the results are assessed using a statistical model. This provides three components to the hybrid score: Q = the hybrid score estimate ranging from 0 (domestic cat) to 1 (wildcat); LBQ = lower boundary of the 90% posterior credibility interval (CI) of the hybrid score Q; and UBQ = upper boundary of the 90% CI hybrid score. An LBQ greater than 0.75 indicates a high probability that a cat is at least 75% wildcat, while an LBQ below 0.75 with a UBQ greater than 0.75 indicates that a cat could be 75% wildcat. This means that where the genetic score is on the lower side, then the pelage score becomes more influential. See Senn and Ogden (2015) for more details.

Table A. Scoring matrix 1 for wildcats assessed for inclusion in the conservation breeding programme (adapted from Senn and Ogden, 2015).

|

Matrix 1 |

- |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- |

- |

Fail (UBQ<0.75) |

Uncertain (UBQ>0.75 & LBQ<0.75) |

Pass (LBQ>0.75) |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

<16 |

Reject |

Reject |

Monitor* |

| Pelage criteria (7PS) | 16-18 | Reject | ? Go to sub-matrix 2 (Table B) | Accept |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

>18 |

Reject |

Accept |

Accept |

* Breed for 1 generation and evaluate pelage of offspring

Table B. Scoring submatrix 2 for wildcats assessed for inclusion in the conservation breeding programme (adapted from Senn and Ogden, 2015).

|

Sub-matrix 2 |

- |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

Genetic Criteria (35 SNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

- |

- |

Uncertain in Matrix 1 & Q<0.75 |

Uncertain in Matrix 1 & Q≥0.75 |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

16 |

Reject |

? Go to committee* |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

17 |

Reject |

Accept |

|

Pelage criteria (7PS) |

18 |

? Go to committee |

Accept |

*Made up of specialists from NatureScot, NMS and RZSS.