SPANS Scotland's People and Nature Survey 2017/18 - Summary report - Participation in outdoor recreation: under-represented groups

1. Background

This summary report is one of a series describing how people in Scotland use, value and enjoy the natural environment. It focuses on the population groups that are under-represented in outdoor recreation, including older people; less affluent people; those living with a long-term illness, health problem or disability; people with self-reported bad health; and members of the BME population (black and minority ethnicity). The report uses data from Scotland’s People and Nature Survey (SPANS), conducted in 2013/14 and 2017/18, and data from the 2012 Scottish Recreation Survey (ScRS).

The research methodology used for SPANS is identical to that used for the ScRS meaning that data from both surveys are directly comparable. As the survey findings are based on interviews conducted with a representative sample of adults living in Scotland, all estimates are subject to a margin of sampling error, see SPANS Technical Report.

2. Definitions

In SPANS and the ScRS the term ‘outdoors’ includes mountains, moorland, farmland, forests, woods, rivers, lochs and reservoirs, beaches and the coast, and open spaces in towns and cities. ‘Visits to the outdoors’ refers to leisure trips taken from home or while away from home on holiday, provided the holiday was in Scotland. ‘Outdoor recreation’ is defined as any non-motorised activity carried out for leisure purposes. It can include informal everyday activities (e.g. walking the dog, family outings) as well as a range of other types of activities such as cycling, hill walking and watersports.

3. Why are outdoor visits important?

Enjoyment of the outdoors, including greenspaces in towns and cities, the countryside around urban areas and more remote and wild areas of land and water, can help provide many social, environmental and economic benefits. These include better health and well-being, an improved quality of life, greater empathy with the natural world, wider use of sustainable forms of transport such as walking and cycling, and economic benefits derived from expenditure incurred by outdoor visitors. Increasing the proportion of adults visiting the outdoors at least once a week and ensuring that the benefits are shared by everyone in Scotland is a key target of the Scottish Government which measures progress via its National Performance Framework.

4. How frequently do people in Scotland visit the outdoors for recreation?

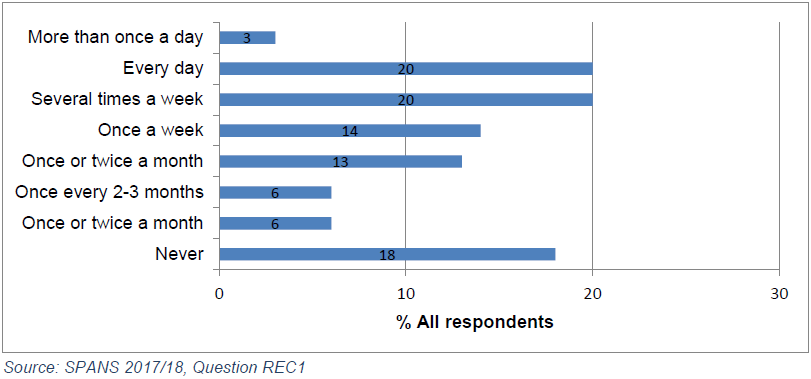

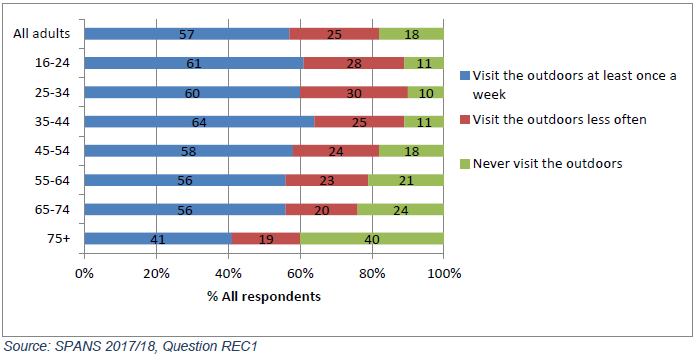

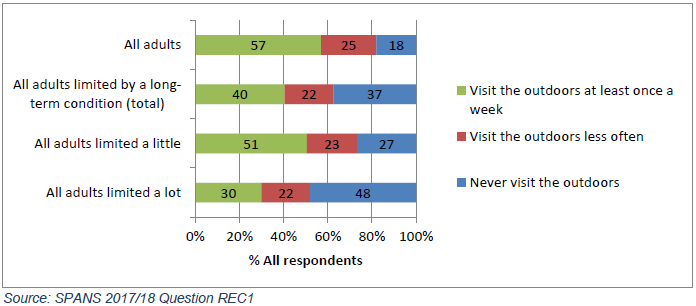

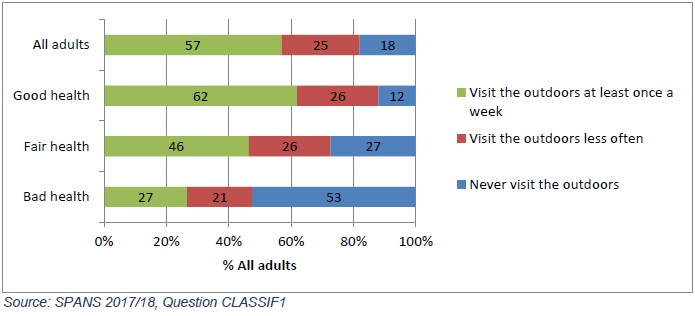

SPANS indicates that most people in Scotland visit the outdoors for leisure and recreation (82% in 2017/18) with just over half visiting on a regular weekly basis (57%). A quarter of adults visit less frequently (25%) and almost a fifth don’t visit at all (18%).

Some population groups are under-represented in terms of their participation in outdoor recreation. Each under-represented group is discussed in more detail in the sections that follow.

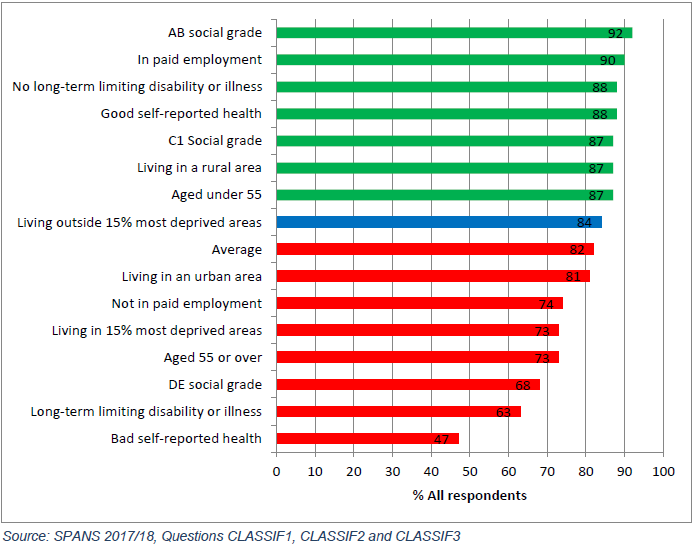

As shown in Figure 2, older people; less affluent people; people living in urban areas; those with a long-term limiting illness, health problem or disability; and people with self-reported bad health are all less likely to visit the outdoors. In addition, members of the BME population are less likely than those of white ethnicity to visit the outdoors on a regular, weekly basis.

5. Participation in outdoor recreation among older adults

Older adults are significantly less likely than average to participate in outdoor recreation and to do so on a regular basis.

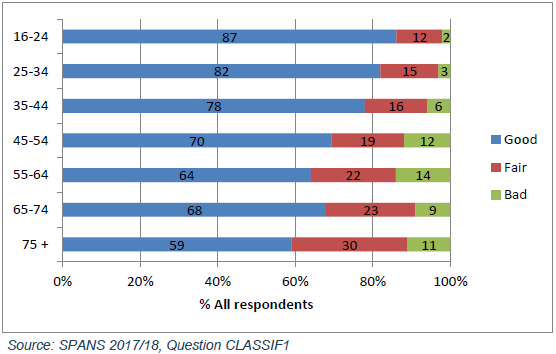

In 2017/18, 76% of adults aged 65-74 and 60% of those aged 75 and over (compared to 82% of all adults) visited the outdoors in the 12 months prior to interview. Around a third of adults aged 65 and over didn’t visit the outdoors at all during this period (31%). Weekly participation in outdoor recreation starts declining after age 35-44 and is lowest among those aged 75 and over. In 2017/18, 41% of those aged 75 and over visited the outdoors on a weekly basis (compared to 57% of all adults).

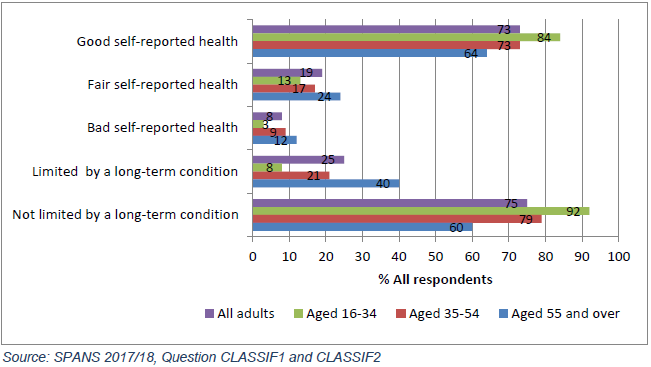

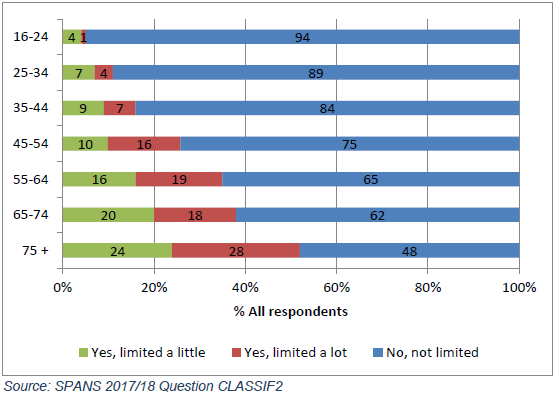

Older people are more likely than average to be living with a long-term condition which limits their ability to participate in outdoor recreation (40% of those aged 55 and over stated this was the case compared to 15% of those aged under 55) and to describe their general health as ‘bad’ (12% of those aged 55 and over compared to 6% of those aged under 55).

In line with this, in 2013/14 SPANS found that ‘poor health’ and ‘old age’ were the main barriers to participation in outdoor recreation cited by older people, especially those aged 65 and over (Table 1).

|

Reasons given |

All adults % |

Aged 16-24 % |

Aged 25-34 % |

Aged 35-44 % |

Aged 45-54 % |

Aged 55-64 % |

Aged 65-74 % |

Aged 75 plus % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Poor health |

23 |

- |

3 |

5 |

21 |

31 |

39 |

50 |

|

Lack of time |

36 |

47 |

54 |

56 |

41 |

36 |

18 |

10 |

|

No particular reason |

11 |

20 |

7 |

12 |

12 |

8 |

13 |

7 |

|

Old age |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

12 |

37 |

|

Poor weather |

14 |

20 |

16 |

9 |

17 |

15 |

9 |

10 |

|

Not interested |

5 |

6 |

4 |

7 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

|

Can’t afford it |

4 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

No car |

2 |

8 |

3 |

- |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

Have young children |

2 |

1 |

13 |

2 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

Source: SPANS 2013/14, Question REC2

Looking ahead, it is worth noting that Scotland has an ageing population. The National Records of Scotland estimate that in the year to mid-2017 19% of people in Scotland (around a million people) were aged 65 and over. By 2041, this proportion is projected to grow to 25%. The fastest growing age group in Scotland is expected to be those aged 75 and over, projected to increase by 79% over the 25 year period between 2016 and 2041. This is followed by the 65 to 74 age group, projected to grow by 17% over the same period. In contrast, the populations of all other groups (aged under 65) are projected to decline over this period.

6. Less affluent people

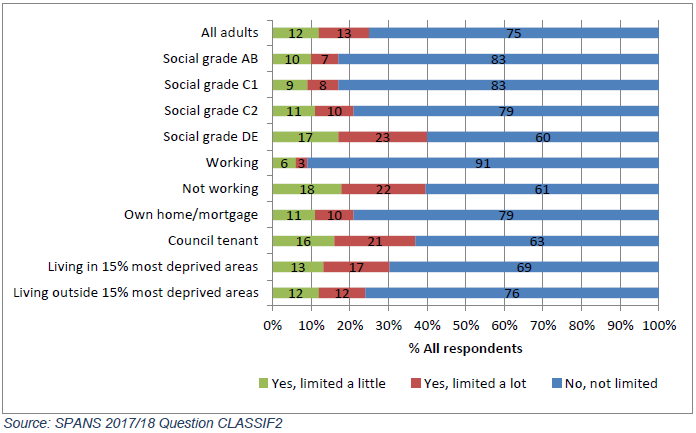

Level of affluence can be associated with a number of variables including area deprivation (using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation or SIMD) and social grade.

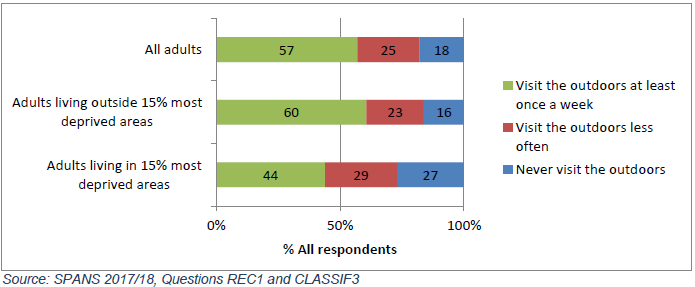

People living in the 15% most deprived areas in Scotland are significantly less likely than average to participate in outdoor recreation and to do so on a regular basis: 73% (compared to 82% of all adults) visited the outdoors in the 12 months prior to interview and 44% (compared to 57% of all adults) visited at least once a week during that period.

The SIMD estimates that around 700,000 people live in the 15% most deprived areas in Scotland (although not everyone living in these areas is deprived and not all deprived individuals live in the most deprived areas).

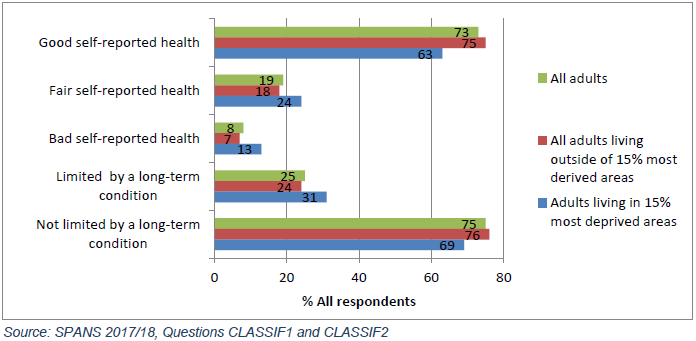

People living in the 15% most deprived areas are more likely than those living outside of these areas to have a long-term condition that limits their ability to participate in outdoor recreation (31%). They are also more likely to report that their health is bad (13%).

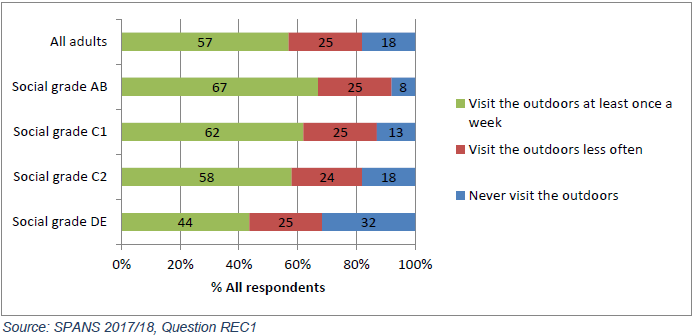

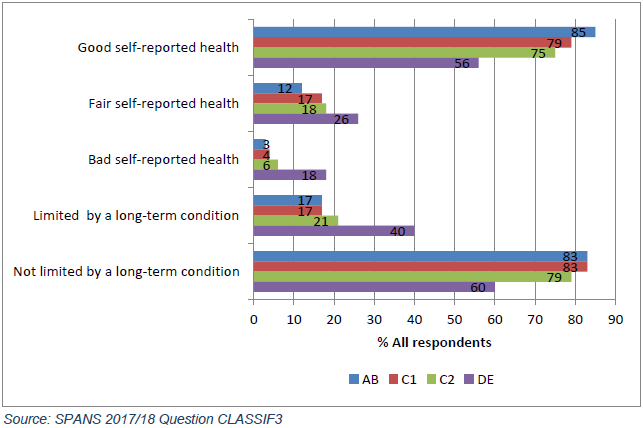

People in the DE social grade are also less likely than average to participate in outdoor recreation than people in any other social grade: 68% (compared to 82% of all adults) visited the outdoors in the 12 months prior to interview and 44% (compared to 57% of all adults) visited at least once a week during that period.

An estimated 29% of adults in Scotland (around 1.3 million people) are in the DE social grade which includes semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers, casual and lowest grade workers, state pensioners and others who depend on the state for their income.

People in the DE social grade are more likely than average to have a long-term condition that limits the ability to participate in outdoor recreation (40%) and to report that their health is bad (18%).

7. People with a long-term illness, health problem or disability

Adults with a long-term limiting illness, health problem or disability are significantly less likely than average to participate in outdoor recreation and to do so on a regular basis: 63% (compared to 82% of all adults) visited the outdoors in the 12 months prior to interview and 40% (compared to 57% of all adults) visited at least once a week during that period. More than a third of adults with a long-term condition didn’t visit the outdoors at all (37%), rising to almost half of those with a condition which limits their participation ‘a lot’ (48%).

People with a long-term limiting condition are significantly more likely than average to describe their general health as ‘bad’ (31% compared to 8% of all adults).

In 2012, the Scottish Recreation Survey found that ‘poor health’ and ‘old age’ were the main barriers to participation in outdoor recreation cited by those with a long-term limiting condition (mentioned by 66% and 21%, of respondents respectively).

|

- |

All adults |

All adults with a long-term limiting condition |

|---|---|---|

|

Reason given |

% |

% |

|

Poor health |

29 |

66 |

|

Old age |

11 |

21 |

|

No particular reason |

21 |

9 |

|

Poor weather |

8 |

6 |

|

Lack of time |

23 |

5 |

|

Not interested |

8 |

4 |

Source: Scottish Recreation Survey 2012, Question 2

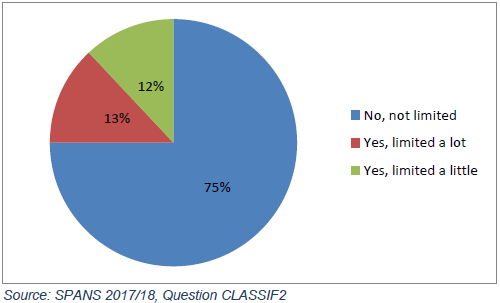

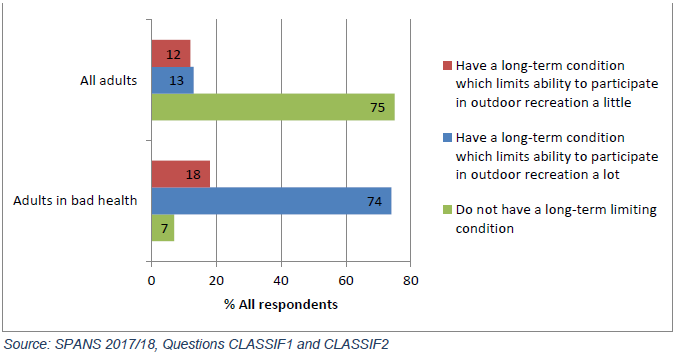

A quarter of adults in Scotland (an estimated 1.1 million people) state that their ability to participate in outdoor recreation is limited by a long-term illness, health problem or disability. Around half of this group are limited ‘a lot’ and half are limited ‘a little’.

The proportion of adults limited by a long-term condition increases with age and is highest among those aged 75 and over (52%).

Long-term limiting conditions are also associated with level of affluence. Those in the DE social grade (40% have a long-term limiting condition)*, those aren’t working (40%), people living in council properties (37%) and those living in the 15% most deprived areas in Scotland (30%) are all more likely to state that their ability to participate in outdoor recreation is limited by a long-term illness, health problem or disability.

* Social grade is a household classification system based on the occupation of the Chief Income Earner in the household: AB - higher and intermediate managerial, administrative and professional; C1 - supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional; C2 - skilled manual workers; DE - semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers, casual and lowest grade workers, state pensioners and others who depend on the state for their income.

8. People in bad health

Adults with self-reported bad health are significantly less likely than average to participate in outdoor recreation and to do so on a regular basis: in 2017/18, 47% of adults who described their health as ‘bad’ (compared to 82% of all adults) visited the outdoors in the 12 months prior to interview and 27% (compared to 57% of all adults) visited at least once a week during that period. More than half of those with self-reported bad health didn’t visit the outdoors at all (53%).

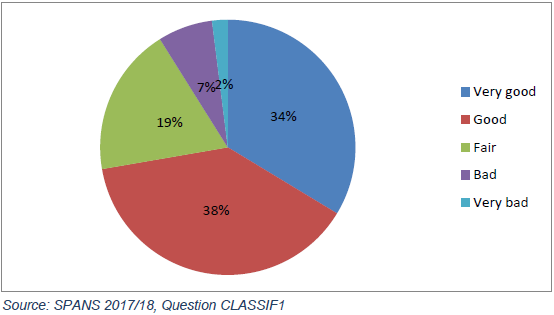

Eight per cent of adults in Scotland (an estimated 367,000 people) describe their general health as bad, including 2% who report their health as ‘very bad’.

The vast majority of people in bad health are also living with a long-term illness, health problem or disability which limits their ability to visit the outdoors for recreation (93%).

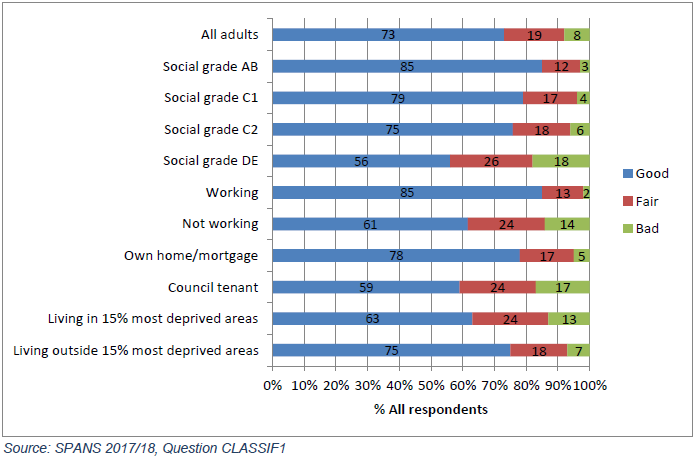

As shown in Figure 16, the proportion of adults reporting that their general health is bad increases with age, with those in the over 45 age groups more likely than average to state that this is the case (12% overall).

As with long-term limiting conditions, there is also an association between self-reported bad health and level of affluence. Those in the DE social grade (18% describe their health as ‘bad’), council tenants (17%), those not working (14%) and those living in the 15% most deprived areas (13%) are all more likely than average to describe their health as ‘bad’.

9. Ethnicity

Four percent of people in Scotland are members of the BME population (around 212,000 people), 2011 Census.

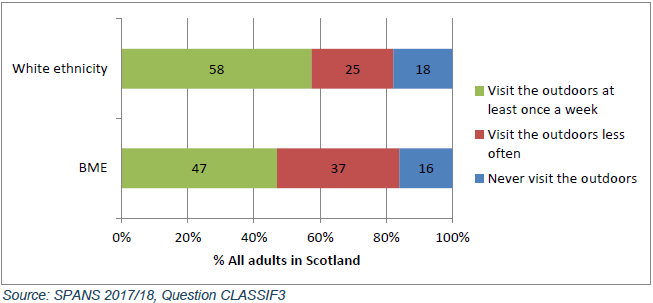

Members of the BME population are just as likely as adults of white ethnicity to visit the outdoors for recreation; they are, however, less likely to visit on a regular weekly basis: 47% (compared to 58% of adults of white ethnicity) reported that they had visited the outdoors at least once a week in 2017/18.

Further information about SPANS and other surveys commissioned by NatureScot is available on the NatureScot website.

Published: 2018