Official Statistics - Terrestrial Breeding Birds 1994-2019

An Official Statistics Publication for Scotland

Scotland’s terrestrial breeding birds occupy a wide range of habitats including urban areas and wetlands, but most are species associated with one or more of the dominant landscapes of farmland, upland and woodland. Some are found in one particular habitat, for example coal tit is a typical woodland bird. Others use a wider range of habitats, such as skylark, which use farmland and upland, or great tit which uses woodland and farmland. Bird populations can respond relatively quickly to drivers, such as changes in habitat extent or condition, which are reflected in breeding success, survival or dispersal (moving from one area to another). Since birds are well surveyed through volunteer-based and professional surveys, and many are widespread and abundant, they are often used as indicators of environmental change.

Evidence

We monitor terrestrial breeding birds primarily through the volunteer-led Breeding Bird Survey (Harris et al. 2020). Randomly located 1km survey squares are visited twice each breeding season (April to July). These squares are intended to be representative of Scotland’s habitats including farmland, woodland and upland. Ten of the 66 species are assessed using targeted surveys, as they are either too scarce for reliable trends through BBS or are better monitored by specialised surveys.

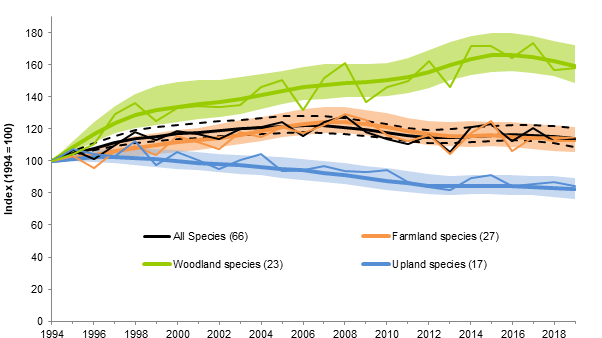

Figure 1. Index of Abundance for Scottish Terrestrial Breeding Birds, 1994 to 2019. Thick and thin lines are smoothed and unsmoothed trends, respectively. Dashed lines (for all species trend) and shaded areas (for habitat specific trends) illustrate 95% confidence intervals.

Assessment

Since 1994 to the most recent assessment in 2019:

- Of the 66 bird species, 34 species increased, 26 declined and 6 were stable (i.e. within 5% of 1994 value).

- The ‘all species’ indicator increased steadily till the mid-2000s, but has subsequently declined to fluctuate between 14% and 17% above the 1994 index value. It is currently 14% higher than in 1994;

- The smoothed woodland bird index increased significantly, by 59%;

- The smoothed farmland bird index increased steadily up to the late-2000s, peaking at 24% above the 1994 index value. It is currently 14% higher than in 1994;

- The smoothed upland bird index decreased significantly by 18%;

- The unsmoothed data show that, between 2018 and 2019 the all species, farmland, woodland and upland bird indices were stable, i.e. have not changed more than 5% since last reported.

Understanding the changes

Breeding bird populations in Scotland are, as elsewhere, affected by conditions in all parts of their range; in the non-breeding, as well as the breeding season. For example, a summer migrant to Scotland may be affected by conditions in Scotland, along its migration route, and on its wintering grounds. Long-term and short-term changes for individual species are assessed using unsmoothed trends. Due to annual variability in the individual species trends, populations are considered to have increased or decreased only when the change is at least 5%. Individual species trends are shown in Table 1. Extreme weather, such as that experienced in winter 2017 resulted in lower numbers of many resident birds during 2018. The latest results show some stabilising to the recent trends, which in part is due to improved conditions for, in particular, migrant birds in 2019. Over the longer term, warming temperatures in Britain have led to earlier breeding in many British bird species but the consequences of this phenological change vary with species. While some species benefit from a longer breeding season, others can be negatively impacted (for example, if this leads to a mismatch between food availability and demand during chick rearing).

Woodland

Over the long-term, woodland bird species have increased more than the other groupings. Seventeen species have increased since 1994. The biggest increases, of over 400%, are for chiffchaff, great spotted woodpecker and blackcap. Bullfinch, cuckoo, tree pipit, great tit, willow warbler, goldcrest and wren have also increased by more than 50%. The biggest long-term decrease (-53%) is for capercaillie. The only other species to decline by more than 10% in woodland was chaffinch.

Over the short-term there has been a mixed pattern. Small bodied and resident species such as goldcrest, wren and treecreeper are particularly vulnerable to cold weather events. As a result, their numbers can fluctuate markedly from year to year. Harsh winter weather, such as that experienced late in the 2017-18 winter (when Scotland experienced the ‘Beast from the East’), is known to affect over winter survival for these and other resident birds. However, 2018-2019 results for wren and goldcrest indicate some rapid recovery, with numbers of both species up by more than 20%. Interestingly, treecreeper did not show any recovery, declining by a further 15% since 2018.

Willow warbler is Scotland’s commonest woodland migrant bird. Changes in its numbers may reflect a northward shifting of its British population, Increases in Scotland have been accompanied by declines further south, and results from the Nest Record Scheme show that laying dates are significantly earlier than in previous decades. The importance of productivity in driving these patterns was highlighted by Morrison et al. (2016) who showed that increased willow warbler abundance at northern latitudes were related to years of high over-winter survival coinciding with periods of high productivity. Further south, productivity of willow warblers was typically low.

Farmland

Overall there has been a long-term increase among the species trends that contribute to the farmland bird indicator. The greatest long-term increases have been for goldfinch (+363%) and great tit (+175%). Magpie, whitethroat, and jackdaw populations on farmland also increased by more than 100% so all five of these species are more than twice as abundant on farmland as they were in 1994. There have been some substantial long-term decreases in other farmland bird population, however, including declines of more than 50% for greenfinch, kestrel, and lapwing, and 25-50% declines in oystercatcher and rook. Some farmland species such as grey partridge, corn bunting and tree sparrow do not contribute to this indicator because of insufficient coverage of these species by the BBS. The 2007-11 Bird Atlas (Balmer et al., 2013) suggests long-term declines for the former two species and substantial increases for the latter in Scotland. Long-term changes in Scottish and UK farmland bird populations have been driven by a range of factors including agricultural intensification, reduced diversity of crop types at the within-farm scale and reductions in spring-sown crops (Donald et al., 2001; Bell and Calladine, 2017). Agri-environment schemes have been in place in Scotland for around two decades, with results varying between different species. Targeted measures, such as the provision of cover crops has been shown to benefit seed eating birds including goldfinch, linnet and yellowhammer (Foster et al., 2013). A recent study in northeast Scotland found positive associations between bird abundance and specific land management options that met species' ecological requirements, in particular reed bunting and water margins, and yellowhammers and species‐rich grasslands. This highlights the importance of farm‐ and field‐scale targeting of management within Agri-environment schemes (Daskalova et al., 2019). In addition, some farmland birds (e.g. goldfinch) may be benefitting from garden feeding (Plummer et al., 2019).

Upland

Seventeen species contribute to the upland bird indicator, and of these nine are in significant long-term decline. Five species (dotterel, curlew, black grouse, hooded crow and dipper) have declined by more than 45%. Long-term changes in upland bird populations have been driven by a number of factors including climate change, forest expansion, and changes in site based management practices such as grazing and predator control (Buchanan et al., 2017). One of the biggest stories to emerge from the last Bird Atlas 2007-11 (Balmer et al. 2013) is the disappearance of many wader species from much of their former breeding ranges, consistent with the declines reported by the Breeding Bird Survey in Scotland and across the UK. Concern about both upland and lowland breeding wader declines has resulted in a wide range of research and conservation initiatives, with many of those in Scotland highlighted on the Working for Waders hub. Changes in numbers of golden plover have been linked to climate change, in part due to impacts on the abundance of craneflies during the breeding season (Pearce-Higgins et al., 2010). Much research is underway to identify factors affecting the rapidly declining curlew populations, with evidence suggesting interacting effects of land use change and predation (Douglas et al., 2014; Franks et al., 2017). In contrast, raven and cuckoo populations have increased, by more than 100% since 1994 and two other species (red grouse and, golden eagle) have increased by more than 20%.

Some other species breeding in the uplands such as whinchat and ring ouzel do not currently contribute to the indicator because of insufficient coverage by the BBS. Both of these species are in long-term decline (Balmer et al., 2013; Henderson et al., 2014; Wotton et al., 2016).

The only short-term increases more than 20% were for hooded crow and common sandpiper contrasting with their longer-term declines across Scotland whereas dipper and snipe declined by more than 20% since the last report.

Birds not specific to any of the habitats

Eight bird species are not included in the habitat-specific trends, either because they do not show a strong association with any of the habitats reported, or because insufficient data were available to calculate a habitat-specific trend. Long-term trends remain as previously reported for most of these species, most notable being the continued decline of swift. The long-term decline of swifts may be related to the reduced availability of suitable nesting sites on buildings (Woodward et al., 2018), though a reduction in availability of flying insects may also play a role (Hallmann et al., 2017). Swifts are long-distance migrants and there may also be factors that influence their survival outside the breeding season during migration or on their wintering grounds. Tracking studies in the UK and elsewhere in Europe have revealed that swifts from northern latitudes overwinter in different locations in sub-Saharan Africa than those that breed further south (Åkesson et al. 2020). In contrast, there have been long-term increases for house sparrow, stonechat, and house martin.

Populations can fluctuate markedly because of environmental conditions and between 2018 and 2019, stonechat and grey heron numbers went up markedly.

Source data and updates

Data for 56 of the 66 species come from the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) run by British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) on behalf of a partnership that also includes the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) and Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). The data for BBS consist of annual counts made over a period of years at a series of sites. Generalised Linear Models were used to generate trends. To prevent short-term population variability and sampling error having an undue influence, trends were smoothed and long-term trends assessed using techniques recommended by Fewster et al., (2000). The smoothed indices were used to assess the significance of long-term changes and the unsmoothed indices were used to assess the significance of short-term changes. Details of the methods used to calculate the indices are available from the British Trust for Ornithology. Trends for common sandpiper and dipper are derived from the BTO Waterways Bird Survey and the Waterways Breeding Bird Survey. Grey heron trends are derived from the Heronries Census. Trends for seven species (golden eagle, hen harrier, peregrine, dotterel, corncrake, black grouse and capercaillie) are estimated from single-species surveys carried out periodically, during the period 1994 to 2018 as part of the SCARABBS (Statutory Conservation Agency/RSPB Annual Breeding Bird Scheme) programme. A further 46 terrestrial species regularly breed in Scotland (being found in at least 100 10km squares in Bird Atlas 2007-11), but insufficient data are available through current monitoring schemes to permit their inclusion in these indicators. In Scotland, the production of multi-species indicators is limited to a start date in 1994 as this is when BBS was first implemented, and achieved broad-scale representative coverage of many terrestrial species in Scotland. Changes reported through these indicators therefore exclude any changes that occurred prior to 1994, which based on UK data show marked declines in many farmland and woodland species.

Results for annual trends in wild bird populations in the UK are available.

Due to the impacts of COVID-19 on volunteer surveys during 2020 the date for the next update will be decided in due course.

Official Statistics are produced by professionally independent statistical staff in accordance with the Code of Practice for Statistics.

References

Åkesson, S., Atkinson, P.W., Bermejo, A., de la Puente, J., Ferri, M., Hewson, C.M., Holmgren, J., Kaiser, E., Kearsley, L., Klaassen, R.H.G., Kolunen, H., Matsson, G., Minelli, F., Norevik, G., Pietiäinen, H., Singh, N.J., Spina, F., Viktora, L. & Hedenström, A. 2020. Evolution of chain migration in an aerial insectivorous bird, the common swift Apus apus. Evolution 74: 2377-2391 (doi: 10.1111/evo.14093)

Balmer, D.E., Gillings, S., Caffrey, B.J., Swann, R.L., Downie, I.S., & Fuller, R.J. 2013. Bird Atlas 2007-11: the breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland (Thetford: BTO Books).

Bell, M.V. & Calladine, J. 2017. The Decline of a Population of Farmland Breeding Waders: a twenty-five year case study. Bird Study 64: 264-273.

Buchanan, G.M., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Douglas, D.J.T. & Grant, M.C. 2017. Quantifying the importance of multi-scale management and environmental variables on moorland bird abundance. Ibis 159: 744-756.

Daskalova GN, Phillimore AB, Bell M, Maggs HE, Perkins AJ. Population responses of farmland bird species to agri-environment schemes and land management options in Northeastern Scotland J Appl Ecol. 2019;56:640– 650.

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2019. Wild bird populations in the UK, 1970 to 2018: Annual statistical release Defra National Statistics, London.

Donald, P.F., Green, R.E. & Heath, M.F. 2001. Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe’s farmland bird populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 268: 25-29.

Douglas, D.J.T., Bellamy, P.E., Stephen, L.S. et al. 2014. Upland land use predicts population decline in a globally near-threatened wader. Journal of Applied Ecology 51: 194-203.

Fewster, R.M., Buckland, S.T., Siriwardena, G.M., Baillie, S.R. & Wilson, J.D. 2000. Analysis of population trends for farmland birds using generalized additive models. Ecology 81: 1970-1984.

Foster, S., Harrison, P., Buckland, S., Elston, D., Brewer, M., Johnston, A., Pearce‐Higgins, J. & Marrs, S. (2013) Trends of Breeding Farmland Birds in Scotland. Trend Note 022. Scottish Natural Heritage.

Franks, S.E., Douglas, D.J.T., Gillings, S. & Pearce-Higgins, J.W. 2017. Environmental correlates of breeding abundance and population change of Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata in Britain Bird Study 64-3: 393-409 (full article).

Hallmann, C. A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H., Hofland, N., Schwan, H. et al. 2017. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas PLoS ONE, 12(10): e0185809.

Harris, S.J., Massimino, D., Balmer, D.E., Eaton, M.A., Gillings, S., Noble, D.G., Balmer, D.E., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Woodcock, P. & Gillings, S. 2020. The Breeding Bird Survey 2019. BTO Research Report 726. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford.

Henderson, I., Calladine, J., Massimino, D., Taylor, J. & Gillings, S. (2014) Evidence for contrasting causes of population change in two closely related, sympatric breeding species the Whinchat Saxicola rubetra and Stonechat Saxicola torquata in Britain. Bird Study 61: 553-565.

Morrison, C.A., Robinson, R.A., Butler , S. J., Clark J.A. and Gill J.A. 2016 Demographic drivers of decline and recovery in an Afro-Palaearctic migratory bird population Proc. R. Soc. B. 283: 20161387

Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Dennis, P., Whittingham, M.J. & Yalden, D.W. 2010 Impacts of climate on prey abundance account for fluctuations in a population of a northern wader at the southern edge of its range Global Change Biology 16: 12–23. DOI:

Plummer, K.E., Risely, K., Toms, M.P. & Sirawrdena, G. M. 2019. The composition of British bird communities is associated with long-term garden bird feeding. Nat Commun 10, 2088.

Woodward, I.D., Massimino, D., Hammond, M.J., Harris, S.J., Leech, D.I., Noble, D.G., Walker, R.H., Barimore, C., Dadam, D., Eglington, S.M., Marchant, J.H., Sullivan, M.J.P., Baillie, S.R. & Robinson, R.A. (2018) BirdTrends 2018: trends in numbers, breeding success and survival for UK breeding birds. Research Report 708. BTO, Thetford. www.bto.org/birdtrends

Wotton, S.R., Stanbury, A.J., Douse, A., Eaton, M.A.. 2016. The status of the Ring Ouzel Turdus torquatus in the UK in 2012. Bird Study 63: 155-164.

Table 1. Percentage changes in abundance for the Scottish Terrestrial Breeding Birds, 1994-2019 and 2018-2019, species listed in order of overall change 1994 to 2018. Summarised trends for individual species and their habitat associations from 1994 to 2018, and the most recent year of change. A blank entry denotes that the species did not show a strong association to that habitat, or that insufficient data were available to calculate a habitat-specific trend.

| Species | Change 1994-2019 | Change 2018-2019 | Change wood 1994- 2019 |

Change wood 2018- 2019 |

Change farm 1994- 2019 |

Change farm 2018- 2019 |

Change upland 1994- 2019 |

Change upland 2018- 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chiffchaff |

874 |

-2 |

874 |

-2 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Blackcap |

548 |

30 |

560 |

29 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Great Spotted Woodpecker |

439 |

-20 |

439 |

-20 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Goldfinch |

257 |

4 |

n/a |

n/a |

363 |

7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

House Martin |

182 |

4 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Raven |

178 |

2 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

178 |

2 |

|

Whitethroat |

153 |

16 |

n/a |

n/a |

153 |

16 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Stonechat |

147 |

84 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Bullfinch |

121 |

24 |

121 |

24 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Magpie |

111 |

14 |

n/a |

n/a |

114 |

15 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Cuckoo |

102 |

-3 |

68 |

9 |

n/a |

n/a |

112 |

-10 |

|

Jackdaw |

96 |

35 |

n/a |

n/a |

112 |

50 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Corncrake |

89 |

-3 |

n/a |

n/a |

89 |

-3 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Tree Pipit |

83 |

10 |

83 |

10 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Great Tit |

78 |

-1 |

84 |

1 |

175 |

7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Reed Bunting |

74 |

-4 |

n/a |

n/a |

74 |

-4 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Willow Warbler |

62 |

19 |

62 |

19 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Goldcrest |

60 |

24 |

60 |

24 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Wren |

56 |

21 |

56 |

21 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Lesser Redpoll |

45 |

-23 |

45 |

-23 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

House Sparrow |

45 |

-6 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Blue Tit |

33 |

1 |

18 |

-1 |

49 |

10 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Yellowhammer |

31 |

11 |

n/a |

n/a |

31 |

11 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Song Thrush |

31 |

5 |

36 |

-2 |

73 |

17 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Golden Eagle |

25 |

1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

25 |

1 |

|

Willow/Red Grouse |

24 |

-16 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

24 |

-16 |

|

Buzzard |

14 |

1 |

13 |

-3 |

61 |

0 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Dunnock |

14 |

1 |

20 |

-3 |

-9 |

6 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Treecreeper |

14 |

-15 |

14 |

-15 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Coal Tit |

13 |

12 |

13 |

12 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Blackbird |

13 |

-5 |

2 |

-8 |

40 |

3 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Siskin |

12 |

-11 |

12 |

-11 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Grey Wagtail |

11 |

3 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Sedge Warbler |

11 |

-7 |

n/a |

n/a |

11 |

-7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Snipe |

4 |

-26 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

4 |

-26 |

|

Mistle Thrush |

2 |

-17 |

2 |

-17 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Robin |

2 |

4 |

10 |

8 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Mallard |

-1 |

-1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Hen Harrier |

-3 |

-2 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-3 |

-2 |

|

Grey Heron |

-4 |

58 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Woodpigeon |

-6 |

-16 |

n/a |

n/a |

-9 |

-17 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Skylark |

-8 |

-10 |

n/a |

n/a |

-16 |

-9 |

8 |

-8 |

|

Linnet |

-9 |

3 |

n/a |

n/a |

-9 |

3 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Chaffinch |

-9 |

-6 |

-10 |

-4 |

-1 |

-2 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Meadow Pipit |

-9 |

-1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-9 |

-1 |

|

Starling |

-10 |

22 |

n/a |

n/a |

9 |

7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Carrion Crow |

-11 |

-10 |

n/a |

n/a |

1 |

2 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Golden Plover |

-12 |

-10 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-12 |

-10 |

|

Collared Dove |

-13 |

-24 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Swallow |

-15 |

-12 |

n/a |

n/a |

-15 |

-12 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Pied Wagtail |

-15 |

16 |

n/a |

n/a |

-15 |

16 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Peregrine |

-19 |

-1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-19 |

-1 |

|

Wheatear |

-23 |

2 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-23 |

2 |

|

Rook |

-25 |

5 |

n/a |

n/a |

-25 |

5 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Common Sandpiper |

-37 |

25 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-37 |

25 |

|

Oystercatcher |

-43 |

-5 |

n/a |

n/a |

-43 |

-5 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Swift |

-46 |

63 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Dipper |

-48 |

-24 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-48 |

-24 |

|

Hooded Crow |

-49 |

25 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-49 |

25 |

|

Capercaillie |

-53 |

-2 |

-53 |

-2 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Curlew |

-56 |

10 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-56 |

10 |

|

Black Grouse |

-58 |

-3 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-58 |

-3 |

|

Lapwing |

-58 |

-3 |

n/a |

n/a |

-58 |

-3 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Dotterel |

-66 |

-5 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

-66 |

-5 |

|

Greenfinch |

-68 |

-10 |

n/a |

n/a |

-65 |

-11 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Kestrel |

-82 |

-59 |

n/a |

n/a |

-82 |

-59 |

n/a |

n/a |