Landscape Character Assessment: Skye and Lochalsh - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The pdf version of this document is at the foot of this webpage.

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten.

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of:

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in the “NatureScot Review 71 – Skye and Lochalsh landscape character assessment”, 1996, Caroline Stanton.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

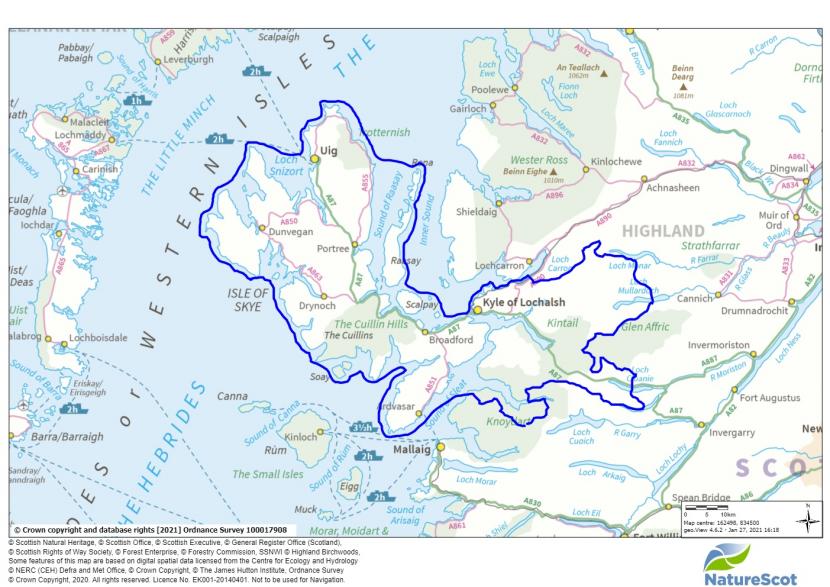

Skye and Lochalsh is located on the west coast of Highland Scotland, covering an area of 270,656 hectares, of which 27% is over 300 metres above sea level. It had a population of 12,374 in 2004, with a density of 4.4 persons per square kilometre, making it one of the most sparsely populated parts of Europe.

The landscape of the area contains great variety, combining a vast range of characteristics within a relatively small area. This diversity is created by both the juxtaposition of the different characteristics and the varying scale, as well as the influence of time, seasons and weather. The dramatic coast and awe inspiring, iconic mountains have been shaped by massive tectonic and climatic upheavals and continue to be shaped by water.

The impact of humans on this landscape initially seems insignificant but the settlements, forbidding castles and even the vegetation illustrate the thousands of years that humans have survived on the edges of this seemingly impenetrable landscape.

Skye has been described as the ‘Winged Isle’, derived from the Gaelic An t-Eilean Sgitheanach. Although the mainland of Lochalsh can hardly be similarly compared to the shape of an eagle or butterfly, these adjacent areas possess a comparable form, dominated by an indented coastline linking deep penetrating sea lochs with protruding peninsulas and inland massifs. The alternative origin for the name is from the Norse “Ski Ey”, Cloudy or Misty Island, which would seem equally descriptive of the island often cloaked in cloud, especially over its peaks.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Skye and Lochalsh is comprised of a diverse range of landform and drainage characteristics, closely related to its complex geology. This is derived from a long history of sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous rock formation, in addition to repeated modification by continental drift, volcanic activity and periods of mountain building and erosion. The complex assortment of underlying rock characteristics responsible for the diversity of landform is often exposed by cliffs, ridges and mountain peaks, sometimes forming distinct landmarks; they are also occasionally revealed by quarries and road and river cuttings. The landform of Skye and Lochalsh is strongly influenced by past volcanic activity which has then been moulded into the modern landscape by glaciation during the last ice age and it continues to evolve due to weathering and the impact of the sea.

The distinct variety of landform and its altitude, slope and resulting microclimate and ground conditions, supports a diverse spectrum of flora and fauna, ranging from rocky alpine precipices which are the home to golden eagles, to acid peatlands smothered in bog myrtle and frequented by red deer. This diversity of environment often results in a startling contrast of impressions, such as the delicate image of lilies upon the dark deep waters of a lochan on a remote, rugged and ‘hostile’ rocky plateau.

In contrast to the abrupt up-thrust and pivoting arc of the Black Cuillin, most of the other upland areas within Skye and Lochalsh comprise large ranges of hills and massifs. These typically rise from coastal waters to extend deep into the inland interior, their character subtly varying and extending into moorland. The moorland plateaux of the area often conceal an assortment of lochans and rocky outcrops, combined with peat hags and mounds. There are some exposed tree ‘skeletons’ within areas of eroded peat hags, attributed to heavy grazing and muirburn.

When compared to the upland areas of Skye and Lochalsh, the area’s moorland tends to be perceived as monotonous and it is often visually dominated by the mountains. Such moorland areas typically coincide with extensive areas of hard underlying rock, particularly Precambrian gneiss and, on Skye, extrusive basalt lava flows. These moorlands have a simple composition of visual characteristics, being extensive expanses without dominating foci. Their typical characteristic is wet peatland with slow meandering streams and spongy wet Sphagnum vegetation. Pockets of blanket bog, in some places extensive, add to this deceptive visual simplicity.

Although there are a few isolated areas within the Lochalsh interior which have a predominantly inland character, the penetration of the sea into much of this district results in the dominance of coastal landscape characteristics. It is the juxtaposition of the mountainous interior with the coast which makes the area so memorable.

Bedrock geology

The base rock across the area is split into two main types; the Lewisian complex is the oldest bedrock type in the area, with gneiss the dominant form, and much of the remainder of the area is composed of Torridonian Sandstone and Cambrian and Ordovician limestones. The eroded roots of the Caledonian mountain belt are found to the north-west of the Sleat peninsula on Skye.

This pattern is complicated by Skye and Lochalsh being on top of the Moine Thrust, an area where tectonic movement forced the rocks to the east to be pushed over the rocks to the west. This has given rise to visible folding and jointing in exposed areas and a variety of weathering patterns where the different rocks have reacted differently. Metamorphosis of the rocks due to heat and pressure exerted by tectonic movement has also created areas of blue talc schist, which have been exploited for quarrying at Ardintoul, as well as metamorphosed marble.

During the Mesozoic period the crust in this area was stretched and the resulting depression allowed Jurassic and Cretaceous sediments to accumulate. Most of the Cretaceous sediment has since been eroded by ice or altered by igneous activity but the coast of Skye still contains complete sections of Jurassic rocks which provide opportunity to study the marine and coastal environments of the time and have provided some significant fossil finds, including dinosaur skeletons.

Volcanic Forces

The centre of Skye has been shaped by four separate volcanic centres which formed on top of the lava plateau. The oldest is the Black Cuillin, with its distinctive layers of dark gabro and lighter, crumbly peridotite. The later eruptions shifted eastwards forming Strath na Creitheach and then the western and eastern Red Hills, which together make up the Red Cuillins. These are predominately made up of pinkish granite which has been shaped into a rounder, smoother shape whilst still being imposing features of the landscape, even the relatively small Glamaig illustrates the geology of the area and is easily recognisable. Much of the moorland is underlain with igneous rock, either basalt lava or Precambrian gneiss and the moorland above has different characteristics accordingly.

The oldest volcanic features include examples of the Trapp landscapes with stepped cliffs and plateaus formed by successive lava flows, like the fissure eruptions common in Iceland. The individual lava flows caused by these fissure volcanoes are around 10-15 metres thick, the lava piled to about 1200 metres thick and connected Ireland to Scotland by a lava plateau. Some of the more famous of these Trapp features remaining are Healabhal Beag (actually the taller of the two Healabhal hills) and Healabhal Mor (a much bigger plateau hence its name), also known as MacLeod’s Tables. Legend recounts how they were used to host a banquet for King James V to support a MacLeod chief’s boast that his dining hall could rival the King’s court.

Basalt sills have intruded into the Jurassic strata and can be up to 90m thick and stacked. Sills have created distinctive features such as Kilt Rock north of Staffin where the vertical hexagonal columns of dolerite is said to resemble a kilt. The difference in weathering between gabro, periodinite and basalt sills on the Black Cuillin has produced the distinctive jagged outline. In most places the basalt eroded more quickly but the Inaccessible Pinnacle of Sgurr Dearg is an exception to this with a blade of basalt left behind.

As well as the igneous volcanic rocks produced from the different compositions of magma, the metamorphism of the Jurassic limestone already present has produced the famous Skye marble, still quarried at Torrin.

Glaciation

Although results of igneous activity in the form of mountain masses may comprise the dominant foci within much of Skye and Lochalsh, it is the impact of glaciation which has typically superimposed its influence throughout the entire district. In the last ice age, Skye and Lochalsh was covered by an ice dome with little appearing above it apart from the peaks of Black Cuillin and the Trottenish Escarpment which stood out as nunachuks. This is evidenced by the accumulation of weathered and frost shattered rock on their summits. The lower Red Cuillins were covered, so ice scoured the peaks leaving smooth rounded slopes with shallow arêtes and gentle corries. The last extensive ice covering of the area was during the Loch Lomond Interstatial. This Ice Age was responsible for the initial isolation of Skye as an island, in addition to the deep carving of numerous glacial troughs and corries, the former often filled by fresh and sea water lochs, creating steep unstable slopes covered with scree and little soil. It was also responsible for the littering of lower foothills and valley floors with an assorted mix of moraine and erratics, notably Glen Sligchan near Loch Ainort where moraine ridges are obvious resting on the lava flows below, in addition to the formation of a string of raised beaches around the coasts. There are many landmark peaks who’s shape has been moulded by ice including the Five Sisters, Ben Sgritheall, The Saddle, the Trotternish Ridge, Macleod’s Tables, the Red Hills and the Black Cuillin, the last dominating the Skye skyline form the mainland due to their high elevation, dramatic profile and rough gabbro surface.

Cnoc and lochan landscapes have been formed where the flow of ice has exploited fault lines, joints and other geological weaknesses to produce a landscape of rocky knolls (cnocs) and hollows, now filled with either water (lochans) or peat bogs. The cnocs are characteristically rounded and steep sided with a whale back shape and sparse vegetation.

The differing resistance of the varied geology of Skye is clear at Loch na dal on the Sleat Peninsula. The cnocan formed from the more resistant gneiss are craggier and larger than the more rounded Torridonian sandstone. The Torridonian sandstone also produces more heathery vegetation, highlighting the geology when the heather is in flower.

The abrupt edges formed by ridges and cliffs create a number of distinctive features within the area’s landscape. These range in character from ‘knife-edge’ arêtes linking angular mountain peaks, deep corries, often with a loch in their base and shadowed through most of the day due to their aspect, to ridges formed by land slippage, and the stepped edges of extensive lava flows.

Post glacial change

The physical landscape has continued to evolve, especially through the dissolution of limestone and marble outcrops deepening stream valleys. Chemical weathering of soluble rock also can produce sudden vegetation changes where bedrock changes, due to variation in soil acidity. In the Red Hills the marble outcrops cause a sudden drop into valleys and the vegetation abruptly changes to rich limestone flora. Significant cave systems have also formed through dissolution and chemical weathering: High Pasture cave system has over 320 metres of navigable passages.

In this area the weight and erosive power of the ice sheets caused more instability which has led to landslips in some areas. The plateau lava of the north of Skye is underlain by weaker sedimentary rocks: the weight of ice and land movement has made part of these unstable and, although the biggest landslips occurred soon after the retreat of the icecaps, some movement is still experienced. Where landform slippage occurs, these areas can hide an amazingly complex range of rock pinnacles and tables, creating an unpredictable mix of mysterious forms. Along the Trottenish Escarpment the Storr and Quiraing landslips have reshaped the landscape. In the Storr landslip the entire south east face of the Storr collapsed producing Coire Faoin and pinnacles of shattered rock, Old Man of Storr being the most prominent. The Quiraing Landslip is believed to be the largest in Britain, covering an area of around 8.5km2. Small levels of slippage are still occurring here and the road below needs regular repair due to the land movement. Further north a smaller landslip formed the equally distinctive Fairy Glen with Castle Ewan, a natural rock pillar standing proud.

Frost shattering and physical weathering continues on higher and more exposed peaks. Notably on high scree slopes like the Great Stone Shute, with debris plummeting 450 metres from Sgurr Aladair.

The Coast

The geological and topographical characteristics of the area are often most clearly illustrated along the coastal edge. The coast forms an essentially linear feature within Skye and Lochalsh, although intermittently broken by a number of focal points, coinciding with the location of bays, settlements and the intersection of a valley or watercourse. The coastal landform of Skye has been influenced by glaciation, volcanic activity and the other forces affecting inland but has also been moulded by the power of the sea.

The coastline of Lochalsh and Skye is dramatic with alternating high vertical cliffs and low bays coupled with headlands and sea stacks, such as the impressive Macleod’s Maidens close to Idrigill Point. Mafic basalt has created the 313 metre high Biodan Athair (Sky Cliff) on the Duirnish Peninsula where some of the highest cliffs on Skye are found. This offers an exhilarating and precarious, yet slightly detached, view of the sea below, whilst being exposed to coastal winds and sea spray in rough weather.

Sea lochs are found, especially to the East of Skye, some with sheltered waters between islands and others with narrow channels with strong currents. The Inner Sound between Raasay and the mainland is the deepest trench on the British continental shelf, at more than 300 metres deep.

The coastal edge opens out to form occasional bays with changes in bedrock geology. Bearreraig Bay has been carved out of Jurassic rocks by the waves. Its calcareous sandstone cliffs contain distinctive carbonate concretions, up to 2 metres in diameter, jutting out of the cliff and littering the rock platform below.

Beaches are uncommon on the coastline with stone and sand beaches, like Talisker Beach, noteworthy for their novelty. Rocky bays such as Bearreraig have their own attractions, in this case fossils of ammonites and similar harking back to its more tropical and underwater history.

Of particular focal value within Skye and Lochalsh are a number of coral beaches, Claigan and Camas Daraich being good examples. These are formed by an accumulation of the red alga, Lithothamium calcaneum: alive it is a deep magenta but desiccated and bleached it becomes a startling white. These beaches are spectacular in their brilliance, reflecting light and creating aquamarine coloured waters. Their attraction is heightened when on closer inspection they reveal a wealth of textures, shapes and colours within the coral mix.

Fluctuating sea levels have left raised beaches, remnants of previous higher sea levels, Broadford raised beach is 30 metres above the current sea level. All of these tilts slightly to the west due to isostatic rebound. Achmore also has a notable raised beach.

Around the coast of Skye there are a number of distinct islands, many privately owned, some inhabited and others abandoned. Raasay is one of the largest with a population of about 170 people, small tidal islands like Fladda and Holman are linked to Raasay, both now uninhabited. Holman is home to a large colony of seals. Raasay has significant forestry and crofting; much of the island was cleared for sheep farming and game in the 19th Century and the population has remained low.

As part of the same ridge of gneiss Scalpay is just south of Raasay, The origins of the name Skalproy – Norse for Scallop Island - suggesting its use for food gathering. Rona is north of Raasay. The glaciated landscape created by the same ridge that produced Raasay is too rocky to sustain a large population. It was used for cattle but experienced a rise in population as tenants cleared from Raasay settled here. This declined and the island now has two inhabitants managing the island. These islands were originally part of the mainland when sea levels were lower and share the same sub ocean drainage patterns.

To the west of Lochalsh, in the Inner Sound, the islands of Eilean Mor, Pabay and Longay are dotted, making navigation more complicated for larger vessels. On the west coast of Skye, Soay, Oronsay and Wiay are the largest islands.

Ornsay is a tidal island off Sleat peninsula which contains a sizeable natural harbour used for leisure craft. Wiay further north has striking vertical cliffs with sea caves and is one of a number of smaller uninhabited islands in Loch Bracadale to the west of the Island.

Soils

Much of Skye and Lochalsh is covered in peaty gleys, with peak and basin peats found in lower lying areas. In the higher and steeper areas the soil is immature with loose rock and scree and limited vegetation. Thin alpine soils are also found in upland areas, for example the Trottenish Ridge.

Along the coast non-leached brown soils are more fertile and this reaches into straths inland in Lochalsh and along Strath Suardal on Skye. These areas traditionally correspond with population patterns although much is now plantation forestry.

There are significant patches of blanket peat, for example at Moineach Mararaulin, Srath Ascaig, west of the Trottenish Ridge and surrounding Beinn a Ghlinne Bhig.

The area has poor fertility and is not well suited to intensive farming. The area has a history of subsistence farming and cattle rearing. Farming was supplemented by both fishing and kelp farming as it was difficult to grow sufficient food. More recently forestry was also limited by poor fertility, as well as poor access, making it less economically viable than similar areas in mainland Scotland.

Hydrology

There is evidence of river valleys carved deep into the base rock from tertiary period off shore around Skye and Loch Alsh. Now flooded by sea level change, these marry up with the main rivers of the area and explain the lack of mature drainage systems in the area. Due to this, rivers such as the Lealt have the characteristics of the upper reaches of a river to their mouth. These included impressive gorges and waterfalls along their course such as the famous Fairy Pools at Glen Brittle, the Falls of Glomach in Kyle of Lochalsh - the highest waterfalls in Scotland at just over 114 metres high - and Eas a’Bhradhain. The Leallt river descends over a basalt sill towards the sea making an impressive sight.

River valleys have developed to exploit the contacts between harder igneous rocks and surrounding rocks and many rivers have dog legged appearances, due to the sudden changes in geology. Glen Sligachan tracks the line between the Black Cuillin gabbro and the granite of the Red Hills where the river has cut into the faults between then, assisted by past glaciation. The longest river in Skye is the Snizort which loops and bends across the island. The River Ling is one of the longest rivers in Lochalsh, feeding into Loch Long, which joins Loch Duich then Loch Alsh with the iconic Eileen Donnan castle guarding the junction. In Loch Alsh area the rivers flow westwards towards the sea whereas on Skye their direction is influenced by the topography and geology.

Climate, Weather and Seasons

Skye and Lochalsh is subject to a mild maritime climate. Its northern location results in associated conditions of long daylight hours in summer, contrasting with short winter days and low light conditions. The long wavelength of this light tends particularly to emphasise the moorland and mountain landforms, and their textures and colours; it especially highlights the orange and brown hues of the district’s vegetation, so that the landscape often appears to ‘glow’. Except on the highest peaks the average temperatures in January are around 3-4oC, warmer on the west coast which is more influenced by ocean currents. The mainland is still influenced by the ocean but average temperatures are closer to 2-3oC.

Summer temperatures are also lower than average for Scotland with mean July temperatures of between 12.5 oC and 13.5oC. Average temperatures on the peaks can be 2-7 degrees lower. Coastal areas have fewer ground frosts days (35-45 in winter) although this increases with altitude and, inland, ground frosts also last into spring and start in autumn.

The repeated reference to Skye as ‘The Misty Isle’ may actually be misleading. It is often assumed that this refers to an abundance of sea fog, however, the predominant cloud and rainfall conditions are usually derived from orographic uplift due to relief. As many images of Skye and Lochalsh so often depict, this results in high levels of precipitation - around 1154 per annum - with rain falling on about 156 days a year, borne by a consistent passage of westerly Atlantic depressions. The open moorland and coastal areas of this district offer spectacular views of the changing weather with rapidly moving clouds and the resulting shadows seeming to ‘dance’ over the varied surface forms of this landscape. With a yearly average of 1160 hours of sunlight, Skye’s reputation may be slightly unfair, as it is just a little under the Scottish average of 1186.8 hours. Winter sunshine hours are higher than much of the west of Scotland.

The combination of characteristic high levels of precipitation, with the remote and deep upland valleys within the Highlands means that such areas are often used as water reservoirs, and for hydroelectric power generation.

In contrast to the prevailing grey days, periods of high pressure do occur within the area, often in late spring and early summer or late autumn months. These bring clear visibility and blue skies.

The equable nature of the maritime climate within Skye and Lochalsh generally means that there are only relatively gradual changes of season, with a characteristic instability and unpredictability of conditions. Although the weather may never be reliable within the district, distinct seasons are illustrated with marked changes in flora, fauna and land use. Typical vegetation indicators, with their changing colours, flowers and fruits, are the heathers and grasses (particularly cotton grass and deer sedge), bracken, flag iris, rowan and birch. The grandest exhibition of seasonal change displayed by animals is possibly that of the stags roaring in autumn and, to a lesser extent, the abundance of lambs in spring. However, undoubtedly the district, and particularly Skye’s, summer season is well known for its torment of midges. A combination of mild damp weather, and water bodies surrounded by grassland, results in these insects often casting a blight on the appreciation of this landscape, particularly during the hours of dawn and dusk.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

Comparable with much of the Western Highlands, Skye and Lochalsh contains only a relatively small population of some 12,374 people (2014) within an overall area of 270,656 hectares (an approximate density of 4.4 persons per square kilometre). This population rose by 11% between 1981 and 1991, and by 3.2% between 1991 and 2001, and is expected to continue along this trend into the future. However, this figure does not clearly represent how much of the upland landscape remains uninhabited, the centres of population tending to be located along the coast or within valleys, linked to the provision of marine and agricultural resources respectively. The majority of the Skye and Lochalsh population resides within isolated rural properties, crofting townships or small harbour and service settlements. The main residential centres are Broadford, Portree, Armadale, Dunvegan, Staffin and Uig within Skye, and Kyle and Plockton within Lochalsh. Only two of these had populations of over 1000 in 2016 – Portree (2523) and Broadford (1095). On the mainland the largest settlement in the area is Kyle of Lochalsh with a population of 643 in 2016.

History

Mesolithic

Mesolithic activity on Skye and the surrounding islands is relatively well represented compared to areas further to the north. Mesolithic activity on the western seaboard of Scotland is often characterised by the exploitation of marine resources on beach and cave sites. The Mesolithic of Skye begins c.7500BC with the recorded lithic scatter at Loch na h-Airde and the rock shelters at Rubh an Dunain and An Corran, Staffin, and finds of worked mudstone and bloodstone in stream beds along the west and south coasts of Skye are not uncommon. This artefactual culture is of the same form as that across the Inner Hebrides, including the open-air sites on Colonsay and Oronsay, and the rock shelters of Mull and Ulva. Dated deposits at the multi-period cave site of High Pasture Cave in the parish of Strath on Skye represent some transient Mesolithic activity and a limited artefactual assemblage solidifies occupation of this system in the late Mesolithic.

Mesolithic activity across Lochalsh and into the inland areas of the Scottish mainland is less apparent. This is exacerbated by the coverage of plantation forestry and a lack of organised survey which inhibits the identification of sites.

Neolithic

The Neolithic of the western seaboard of Scotland is complex. In contrast to the well-developed agricultural representation of these people across the east and south of Scotland, here it has been severely impacted by the scarcity of suitable sites of arable agriculture. Evidence of early settlement within Skye and Lochalsh dates back to a number of standing stones, burial mounds and cairns, relics of the Neolithic. Neolithic sites in Srath Ascaig include a megalithic chambered cairn (5,000-2,000BC) and a mound at Achmore Bridge thought to be a chambered cairn. On Skye most of the chambered cairns are passage graves of a similar type to those found in Orkney, Cromarty and the Hebrides which, in their simplest form, have a short passage leading into a small chamber - the excavated cairn at Rudh’ an Dunain being a good example. Around the island, chambered cairns including the Suardal cairn suggests a mortuary use of the landscape which must have been associated with a less apparent domestic use. High Pasture Cave in Strath again returned Neolithic dates and artefactual assemblages, although sparse, and as in more northern regions some investigations of Bronze and Iron Age roundhouses have returned Neolithic dates for buried soils, suggestive of ‘slash and burn’ agriculture and woodland clearance in this period. Stray finds such as a carved stone ball identified at Roag on Skye also point to the use of the island in this period.

Evidence of Neolithic activity in the Lochalsh region is similarly constrained by the landscape and again by plantation forestry. A stone axehead in the collections of the National Museum of Scotland was identified during roadworks at Kyle of Lochalsh in 1953 and has been provisionally dated to the Neolithic, implying use of the landscape in this region, but large-scale sites have not been identified.

Bronze Age

The surviving Bronze Age archaeology of Skye and Lochalsh points to an increased focus of activity in the uplands, including the Cuillin ridge and around Uig in Skye, and in the heights above Dornie and between Kyle of Lochalsh and Plockton on the mainland. Whether the upland settlement record is one of preservation bias or an original distribution is debatable, but it follows the wider model of northwest Scotland with Bronze Age roundhouses or hut circles preserved above 100m and often associated with limited landscape clearance denoted by clearance cairns. Some of the settlement record is more substantive: a circular rise known as the Achmore Enigma is thought to be a bronze age roundhouse (2000-500BC). It is a large building around 16 metres in diameter with evidence of substantial stone walls. It is in a poor defensive position suggesting that it is not a defensive site, but may represent monumentalism important to signifying power within the landscape. Throughout these landscapes, Bronze Age burnt mounds are often seen within wetter areas or alongside stream courses, and extensive Bronze Age land surfaces with traces of cultivation can be found buried beneath the blanket peat.

The Bronze Age mortuary record is represented by cairns and cists, such as the cairn on the shore at Inver Aulavaig in Sleat, which covered a number of stone cists, or the burial cists containing a Beaker found at the Broadford Community Hospital site in 2018.

Iron Age

Skye, Lochalsh, and the neighbouring island of Raasay have a more visible Iron Age record than the Bronze Age precursor (the Iron Age is c500 BC to the Early Medieval period). Many of the monuments of this period are defensive sites, consisting of a number of duns and brochs - tall hollow-walled roundhouses built without mortar - such as Dun Borodale on Raasay. Dun Beag and Dun Ringill on mainland Skye, and Dun Telve and Dun Troddan in Glenelg, form spectacular and substantial structures on many prominent and defensible locations within the area. The majority of these defensive sites are coastal or sub-coastal with the exception of areas to the north and east of Dornie and along the route of the A87 as it penetrates deeper into the mainland. These sites usually control high points or coastal promontories, speaking to their defensive intention, and were designed to be seen from afar. In the north of Skye, brochs are the common building type, often built on rocky knolls on hillsides around the coast, in locations with good visibility of the surrounding land. Small promontory forts are more common in the south of the island, utilising small promontories jutting into the sea. Some of the forts may date to the Iron Age, including the vitrified fort at Carn na Sean Creag next to Achaidna na H’Inich, Lochalsh. Vitrification occurs when the rocks have been fused together by burning at high temperature. Non-defensive settlement from the Iron Age is less evident, which may be due to subsequent construction on top of domestic sites located in prime agricultural land or in coastal embayments.

Other site types dating to this period include crannogs - fortified manmade islands - and these include examples in Loch Achaidh na h-Inich in Kintail, which is now mostly covered by artificial increases in the loch water level, and the small Lochside site in Loch Mealt, north Trotternish. Excavations in advance of the Broadford community hospital site in 2018 identified a grain drying kiln and souterrain, a stone-lined passage from the Iron Age, and other domestic activity. The upland roundhouse record in Skye and across the upland regions of Lochalsh and towards Plockton is reminiscent of that on the wider western seaboard, with roundhouses and associated field systems existing, preserved by the lack of development or modern agriculture. Modern plantation forestry is beginning to change this distribution, however, with many upland glens being drained and planted.

Early Medieval

The north of Scotland was ruled by a mosaic of small groups, principally known as the Picts, from around AD 100, although Gaelic groups originating in the north of Ireland held Argyll from around 300AD. It is likely that these groups continued to use the brochs and forts built by their predecessors as well as building additional forts, but there has been little excavation of these structures to provide a chronology.

The Gaelic influence on the area was strengthened with the introduction of Christianity by the Irish in the 6th Century AD. St Columba was reported to have landed at Kilmuir (Cill Muir or Mary’s church), and there are remnants of larger Columban monasteries, as well as those of other schools, and missionary churches like St Moluag’s on Raasay which merge Pictish stonework with the emerging Gaelic Christianity.

Evidence of the arrival and occupation of the Gaels within Skye and Lochalsh tends to be the most noticeable from the prolific place name evidence. The language of the Gaels indicates their distinct appreciation of the landscape, possessing a wide range of associated words which have no English equivalent.

Norse settlers took control of Skye and Lochalsh area around 700AD and remained in power for close to 500 years. To the east of Skye, by Loch na h-Airde, there are remains of a Viking canal, evidence of boat building and repair docks, with Norse influences in the name and lineage of the clans who traditionally owned the area (MacAskills, from Asgill and MacLeod, from Leod or Ljotr). Their most dominant legacy, however, is in the form of placenames, with Norse elements forming part of most of the main settlements and landforms, especially those around the coast. By the end of Norse rule in Skye and Lochalsh the ruling families were heavily intermarried with ruling Gaelic families and culture was already merging.

12th to 17th Centuries

1266, which saw the ceding of Norse suzerainty in favour of the Scottish crown marked the final end of Norse control, although many of the most powerful families maintained contact for some time after. The MacLeods were keen to mark their Norse ancestry, for instance, to distinguish themselves from the more Gaelic-centred MacDonalds. At a Scotland level the big shift of power occurred in 1292 when John Balliol was proclaimed King of the Scots but to achieve this he had to recognise the English King as his overlord. Fighting continued sporadically with Robert the Bruce succeeding in gaining recognition as King of Scotland in 1328 and becoming the foundation of the Stewart monarchy (through his daughter). The shifts in power between the ruling Scottish families caused tensions between clans and changes in land ownership. Lochalsh was forfeit by the MacDonalds in 1494 and became MacKenzie land, the hereditary title the Earl of Seaforth was granted and Lochalsh remained in their lands until 1801 when the land was sold to the Innes family.

Some of Scotland’s earliest stone castles, such as Dun Akin/Caisteal Maol or Eilean Donan betray the importance of the seaways around Skye. Many of the later castles were often linked to the bloody relationship between the two most powerful clans within the area, the Macleods and the Macdonalds. Brochel on Raasay, Eileen Donan in Lochalsh and Duntulm on Trottenish, all located with good seaward views to control maritime routeways, local fishing grounds and/or harbours, show the wealth and instability of the clans at that time. Many prehistoric forts were re-occupied, with medieval deposits or structures being recovered from all the best-preserved brochs – perhaps the most notable being Dun Ringill. Tales of the bloody events during this time resonate through the landscape including the burning of a church full of parishioners in Trumpan, Waternish by the MacDonalds of Uist, in retaliation for a previous Macleod attack on Eigg. These events are recorded by the flourishing bards, poetry and music, especially piping, supported by the chiefs of the area. These fights started to die down in the 14th Century and the last skirmish of note was reported to have occurred in Coire na Creiche (Corrie of the raid), probably due to the continuing practice of cattle rustling in the area. Rustlers exploited the complicated landscape to hide their gains.

These lords were also keen patrons of the church. A bishopric with a cathedral was established at Snizort, although its influence waned as the Lords of the Isles became more focussed on the MacDonalds and ecclesiastical power became centralised on Iona. Stone parish churches were built on earlier chapel sites and many were embellished by fine examples of sculpture in the West Highland tradition: a good example being St Moluag’s in Eynort, which has several examples of medieval grave slabs and had an ornate cross shaft marking the boundary of the sacred area around it, but which has now been moved.

By the end of the medieval period most communities were living in scattered settlements along the more fertile valley floors. The remains of these houses can still be seen, usually surrounded by extensive rigs (raised strip fields) and patterns of dykes and other land divisions. There are more remote examples patches of rig, often around a single house, further up some valleys, and beyond the head dyke the hills were exploited as summer pastures. Green mounds, sticking out above the surrounding moor, and located neat running water, betray the remains of the sheiling/airigh huts where families lived when the cattle were enjoying the nearby vegetation.

Like much of the Highlands, the Skye and Lochalsh area was partially supportive of the Jacobite uprisings and heavily affected by the aftermath. Not only the loss of men but the changes in land ownership and stricter administration by the English military set in action a number of actions that would have a significant mark on the landscape and communities, whether supportive of the Stuarts or Hanoverians.

18th and 19th Centuries

After the unsuccessful Jacobite rising of 1745, the mutual ties, trusts and responsibilities which had held clans together were eroded and replaced by a relationship based much more on economics. The chiefs became landlords, dividing rigs and other lands previously organised as a rotational ‘runrig’ system, where the landless poor were catered for, into crofts that demanded rents, rather than payment in kind. This, in combination with a high population, a succession of poor harvests and a shift from cattle to sheep, resulted in mass ‘clearances’ of land and emigration. Those who remained in the district were somewhat aided by the prosperity of the kelp industry at the turn of the century, but this slumped during the 1820s. The decline of the kelp industry caused lairds to develop further the sheep farming industry, converting large tracts of Skye and Lochalsh to sheep walks. In addition to a number of bad harvests, a population boom (an increase of 46% between 1755 and 1801) resulted in further subdivision of land and created even greater pressure on such areas. Without the security of tenure, improvement, and management of land were not encouraged resulting in significant land degradation and infertility, encouraging still further migration. The agricultural changes were similar to those experienced across Europe at this time but, when coupled with the major cultural upheavals, it became a period still recalled with bitterness. Lochalsh was significantly affected by its purchase by the Innes family in 1801. It led to almost immediate evictions with the area mapped, divided for sheep farms, and cleared within 15 years of purchase. The census shows people initially moving to coastal settlements such as Ardnaff and Portachullin, and to the designed town of Plockton, but the population of the area started to decline due to emigration and a large number of young men joining the army to fight abroad. The population continued to decline until the 1970s.

Unrest and clashes between evicted families and landowners were at times violent and police from further south and marines were deployed to round up the ring leaders. Reports of the continued clashes led the Prime Minister William Gladstone to set up an enquiry.

The instability did not ease until the Crofters’ Holding Act of 1886, when tenant farmers earned security of tenure. However this did not apply to previously lost lands and, as in many parts of the Highlands, past depopulation is still clearly evident in the Skye and Lochalsh landscape. There are a multitude of abandoned croft houses, enclosures, rigs and feannagan/lazy beds, enabling the growing of crops and particularly potatoes in less favoured ground. Evidence of villages such as Leiter Fura on Skye, Hallaig on Raasay and Braentra, Lochalsh where collapsed stone outlines, show the deserted homes of entire communities. The remains of smaller houses, particularly in areas with less favoured arable ground, surrounded by extensive lazy beds, mark the height of pressure on the land both before and after the clearances. Areas of ground that had previously been summer pastures, where centuries of grazing had slightly improved the soil cover, were often brought into cultivation by cleared families.

In 1851 Lochalsh and Eilaen Donan were bought by the Matheson family (regaining old family land) and Duncraig Castle was built. The Matheson family were also a key financier of the Dingwall and Skye railway which made Lochalsh and Skye accessible to the middle class tourists emerging in this period, as well as improving trade in and out of the area.

Transport improvements through the 19th Century made massive impact on the communities in this area. Until 1813 it was very isolated with few tracks in and out. The journey to Skye also involved a small boat which reinforced its isolation and independence from the mainland. The main transport routes were poor quality droving roads, for example the road to Sallachy. In 1813 the Lochalsh road was built linking Kyleakin Ferry to Strome and thus further afield, meaning the journey could at least be undertaken by carriage and cart more easily.

General Caulfield built a military road to Glen Elg Barracks in the 18th Century, to help control unrest in the Highlands. Thomas Telford upgraded this in the 19th Century, linking Sheil Bridge with Glen Elg via the Mam Ratagen Pass.

Sixty years later the biggest development in opening up the area to the outside world occurred when the railway to Strome Ferry opened in 1870. Strome briefly thrived with ferry terminuses to Skye and Lewis, and associated infrastructure was built. However, this was short-lived as the railway was extended to Kyle in 1898 and Kyle of Lochalsh took over as the main ferry terminal.

Since the 12th Century there have been ferries running to Skye from Glenelg and Armadale, and this was the key point for access to Skye due to the short crossing. The railway to Kyle of Lochalsh allowed the development of a larger harbour for goods and visitors to the island and on to other ports in the area.

These improvements in transport allowed for the development of what is now Skye and Lochalsh’s biggest industry, tourism.

As the landowners became less connected to the clan system the highland estates became treated more as commercial and leisure interests. Game became an attraction for the wealthier visitors and estates started to manage moorland for this as sheep became less profitable. The popularity of the Highlands grew with Queen Victoria’s passion for Scotland and the romanticised Highland images made popular by Turner and other painters and authors. The British Tour became a way for the wealthier middle classes to travel and the Highlands became an essential destination in this, aided by the arrival of steamers and ferries from Glasgow and the railway.

In the latter half of the 19th Century, the dawn of the mountaineering age and organised climbing in Skye meant a new type of traveller. Sgurr Alasdair was named after one of these early mountaineers, Alexander Nicholson, and the alpine style of climbing available here meant that Skye became a destination for mountaineers and explorers looking to train for more remote destinations.

Other industries that developed in the 19th and early 20th Century include whisky. 1830 saw the opening of a legal distillery at Carbost which later became Talisker distillery which is still going strong today, and mining. Cloth making, tweed mainly, was also widespread with a number of small scale mills but these became uneconomic and closed in the second half of the 20th Century.

The 20th Century

By 1934 the population had shrunk to about 11,000 less than half of a century before. The First and Second World Wars contributed towards population decline in the area as young men left and many did not return, whether killed or deciding to move away from their homes after the conflicts. The distinctive War memorial at Glen Elg, looking out over Kyle Rhea, commemorates the soldiers lost. They include Valentine Fleming, a landowner in the area who was the father of Ian Fleming the author. Young people continued to move away from the area throughout the twentieth century with few returning. This also led to an aging demographic across the Highlands as a whole. This decline has slowed and the provision of tertiary education in Skye and the rest of the Highlands has reduced the flow of young people from the area, although the population is still very heavily skewed towards those over 50 years old.

Starting in the interwar years, after demand for wood in the First World War had led to nationwide deforestation, forestry became a growing industry in Skye and Lochalsh. Although limited by the transport issues, plantations grew up in the southern part of Skye and Raasay as well as on the mainland.

After the Second World War, ambitious hydroelectric plants such as Storr Lochs were built, bringing electricity to the area.

The Skye Bridge was opened in 1995 and removing the barrier of embarking on a ferry made Skye more accessible. The transport developments that had led to the growth of Kyle of Lochalsh now led to its decline. The shift to larger ferries from the 1970s onwards made Ullapool’s larger harbour capacity a better destination for crossings to the Western Isles. Kyle became a less important harbour and its population and prosperity declined.

Road building became either the lifeline for villages or a final decision in their demise, Calum’s Road on Raasay was built by Calum Macleod, mostly singlehandedly, to connect Arnish with Inverarish and the ferry was built to stop the township from dying out, and allow his daughter to come home more easily. However, it happened too late for the village and it is no longer inhabited. In other parts of Skye, the increase or decrease in population is reflected by the road-building near it.

Tourism grew quickly from the last decade of the 20th Century, made easier by the bridge and road improvements further south. This increase in numbers of visitors continues.

Land Cover

Woodland

A number of isolated patches of broadleaf woodland form pronounced foci along the Skye and Lochalsh coastline. This vegetation represents merely a relic of the past extent of woodland within the district, typically winding itself along the most sheltered and least accessible stretches of the coastal edge. The rarity of these woodland fragments heightens the appreciation of their distinctiveness, both in the character of the trees themselves and the habitat they create. The woodland fragments mainly comprise birch, oak or hazel species, with pockets of aspen, willow and rowan. The stand interiors are typically difficult to penetrate, as the trees tend to form low, bent and contorted shapes, often growing out of a dense surface of carpet rock, ferns and mosses. Of all the native tree species, birch tends to occur most frequently within the area; its white papery bark and small ‘dancing’ leaves typically reflecting light back and forth within such areas, to create a dynamic display of light and dappled shade, as well as a wealth of various textures, colours, noise, smell and form. Ash trees are found on limestone outcrops, such as between Achmore and Braeintra and a larger woodland at Coille Thogabhaig, another visual indicator of the varied geology of the area.

Planting in the mid-19th Century around Duncraig Castle and Strome wood has produced designed woodlands with a mix of native and exotic tree species. Plantations of coniferous trees can be found throughout the area, for example, Kinloss Forest and south Raasay, and were planted during the 20th Century to provide a steady supply of homegrown timber. Forest design has evolved greatly since the early stands were planted almost 100 years ago and more diversity of age and species is now common with the forest areas being valued for both recreational and material. Broadleaf trees are now valued within newer schemes.

Regeneration of woodland and decline in the quality of native woodland has been in part due to high levels of sheep and increasing numbers of red deer grazing in the area. Sheep numbers are now lower than they have been in the previous century but active deer management is important to protect young trees. Fencing is common and can produce hard edges to forestry. There are now other approaches in force that promote a more natural woodland edge.

Grassland and Moorland

The most widespread habitats in the area are heather moorland, peatlands and acid grasslands. The EUNIS habitat map of Scotland shows large sections of Skye and Lochalsh as mires, bogs and fens habitat with grasslands, heath and scrub in the lower areas. Dwarf shrub heath and moss heath are found with widespread peatland occurring as mosaics of blanket bog and heathland. Extensive deeper bog occurs at lower altitudes at Mointeach nan Lochain Dubha and Sligachan which are examples of oceanic blanket bog with dark coloured pools scattered through. The limestone pavement at Strath Suardal supports crevice vegetation and distinctive species-rich grassland which contrasts with the more acidic surrounding areas. There is little cultivated land across this area but much of the grasslands around the coast is used for grazing.

Montane Habitats

Trottenish Ridge and the areas around Sgurr na Coinnich and Ben Aslak are classified as montane habitat. Base-rich soils support rare plant communities along the Trottenish Ridge due to the basalt ridge below.

The higher and steeper Cuillins are predominately sparsely vegetated with high proportions of bare rock and scree and small communities of alpine plants and bryophytes.

Coastal Habitats

Coastal habitats are limited by the narrow coastal margins and rocky coastline. Rubha an Torra Mhor shows spit and depositional features but the coastline is fairly static in this area. Rocky headlands like Rubha Hunish on the north coast are exposed to the predominant westerly wind but Skye is protected by the Outer Hebrides from the full force of the Atlantic.

Beaches occur on the west of Skye such as Port Kilbride and Uig Ba and Culnamean. Hard rock and cliff are the most common habitat, supporting arctic-alpine and tall herb-rich vegetation at low altitudes.

Saltmarsh is found around the coastline in sheltered bays and loch-heads but not as large expanses. Loch Sligachan, Loch Portree and Barrisdale Bay are fairly typical examples where the marshes transition into heathland

Land Use

Compared with the rest of the Highlands, and Scotland as a whole, Skye and Lochaber has a higher share of employment in agriculture, forestry, fishing and accommodation and food services. Tourism accounts for around 35% of employment, with food production, farming, fishing and aquaculture all having a high profile.

Crofting and Agriculture

Despite the extensive depopulation that occurred within parts of Skye and Lochalsh, the crofting township still remains the dominant settlement type within the area. The location of these townships typically relates to the coast, watercourses or valleys, as these environments tend to offer favourable microclimate, access, soil and drainage conditions. Although the form and density of the townships varies, they possess common components, such as the small scale and simple design of croft house within an area of extensive common grazing. Within such townships, a few old ‘black houses’ remain, built of drystone walls and thatched with straw; however these are rare in comparison to the newer ‘white house’ which started to be built at the end of the 19th Century. These houses tend to highlight the layout and pattern of buildings within the crofting landscape due to their colour contrast, although this characteristic is being increasingly changed by the rapid proliferation of new ‘kit houses’; these typically appear as isolated elements within the landscape as, unlike their earlier counterparts, they tend not to directly relate to the land in either their function, location or design. Modern design based on traditional styles is now evident in these places, especially for purpose-built holiday accommodation, some enhancing the character of the landscape.

The character of land division within the crofting township is most clearly highlighted by the formal pattern of the property boundaries superimposed upon the landform. Dykes and ditches showing field patterns are marked on 1807 maps, and some are still in use. Drainage ditches from the 19th Century, as well as burn realignment, is still evident. This pattern now appears to be losing its distinction, however, as agricultural practice through the later part of the 20th Century and early 21st Century and the provision of farm subsidies encouraged an increase of sheep grazing at the expense of cropping. This encouragement is not as evident now with subsidies for traditional crofting methods, diversification and environmental stewardship more prevalent through the Sustainable Rural Development Programme. The pattern changes are comparable to other areas throughout the Highlands, and even though the crofts never supported full-time employment, they can now be barely relied upon to even provide part-time income. Proposals exist to encourage further active land use through crofter ownership, and greater land diversification by, for example, the provision of woodland grants which allow tenants to own woodland upon common land. However, the trend still seems to be for an increasing reliance upon supplementary sources of employment within the growing service and tourist industries. Such intense seasonal commitment tends to encourage less active management of the croft and this has resulted in many townships possessing a ‘neglected’ appearance through unmaintained boundaries, outbuildings, pasture, drainage, etc., and an expansion of ‘weed’ species due to the selective nature of grazing sheep.

Estates

Increasing extensive management of land is also occurring within the large rural estates of Skye, and particularly Lochalsh. These estates, which traditionally comprise a foci of estate buildings, boundary walls, rich pastures and mature woodlands, with a distinct historic image, are now increasingly unprofitable, with a growing reliance on external funding. This is typically through utilisation of sheep subsidies, woodland grants, and a greater dependence on income from sporting and tourist activity; this tends in turn to increased pressure on the landscape due to heavy grazing by sheep and deer, and track construction and erosion.

Red deer populations have increased over the last 50 years, especially around Lochalsh, although it is a greater issue on Skye then previously. Control of deer populations is an important part of habitat improvements in these areas as well as a lucrative business, both shooting and in selling the meat produced.

Community landownership and right to roam legislation have affected some of the traditional estates. The Land Reform act of 2003 changed access laws within Scotland meaning that access to land was enshrined in law and communities were given the right to buy land and other assets.

Glendale was the oldest community-owned estate in Scotland in 1908 but they were limited until the 1990s when Borve and Annishadder community trust bought the estate they lived on. The 2003 Act and subsequent legislation have made this process more transparent and open to a wider type of property including smaller-scale ownership of individual assets. In this area community facilities like shops, public toilets and post offices are essential to communities, with Kyle and Lochalsh and Sleat community trust running facilities in the area for residents and visitors.

Settlements

Within Skye and Lochalsh most settlements are concentrated within the coastal areas or within the flat-bottomed straths leading towards the coast.

Harbour settlements, in contrast to the more extensive crofting townships, tend to be more confined; located on the coast, they characteristically possess a concentrated hub of activity. The focus of these settlements varies considerably in scale, from large ferry terminals, such as Kyle harbour, linking to Uist and Harris; to small jetties supporting local aquaculture or fishing industries. They tend to display an interesting visual variety of forms, textures, colours, people and movement.

Portree, the capital of Skye, was created as a fishing village at the beginning of the 19th Century. It is located on a sheltered bay and remains in use for leisure craft and fishing fleets.

Designed settlements such as Plockton and Edinbane were created for displaced crofters. Plockton grew into a village in 19th Century, possibly from a small crofting settlement. The Innes family designed the planned village based on fishing and subsistence crofting, and Plockton grew due to its fishing harbour and declined when the industry did. Its infrastructure and attractive design mean that it is now a tourist destination.

Edinbane was redesigned in 1861 as a ‘new town’. Its design included schools, a watermill and inn as well as housing. The philanthropist Kenneth Macleod also designated required professions such as a smith and carpenter, and a trust to run a hospital, which was closed in 2006. Now much reduced in both services and population, it is within commuting distance to Portree and a focus for visitors.

Crofting townships like Staffin have a more extensive layout with lines of fields and houses along roads stretching along the coastline and straths. The housing is modest and traditional in style generally and the fields are a brighter improved green in summer. Farm buildings, vehicles and caravans are not uncommon and much of this is functional in style.

Although most development within Skye and Lochalsh remains small scale, the current population growth needs to be supported by increased services and the creation of opportunities for employment. This raises many issues concerning housing and how to incorporate the changing relationship between people and the land, which was once so closely integrated within this landscape. There is a substantial demand for new houses due to the rising population and decreasing household size; the expansion of existing settlements, however, may create a confusing image of the old and new, as properties are increasingly residential in character and modern communities typically require new standards of servicing. New housing is now more common in Skye although large developments are limited. There are a number of local firms designing and producing houses, and prefabricated housing with inspiration from the past architectural styles of the area and some have been publicised widely and won accolades. A new village and university facilities at Kilbeg on the Sleat Peninsula is the first planned settlement to be built on Skye for over 150 years.

Tourism

The Skye and Lochalsh landscape is intermittently dominated by large numbers of visitors. A high proportion of these come to enjoy the natural heritage of the area and the recreation opportunities this has created as well as the history of the area. Although the immense pressure that these inflict is a relatively recent phenomenon, there has been a long tradition of people visiting the district and particularly Skye.

Today, influxes of visitors to the area in the summer months can result in an area bustling with backpackers, hill-walkers, mountain climbers and traffic including campervans, motorhomes and caravans, all directed by a proliferation of signs. Off-season there can be under-utilisation of services and tourist facilities are empty or closed. Collectively this can create an image of the increasing shift of land use and income away from practices which directly relate to the landscape, towards the service and tourist industry.

Appreciation of the Skye and Lochalsh landscape is very much influenced by access into the area. There is only a sparse network of roads through the region, often built upon past droving and military routes; this means that increased traffic tends to exert excessive pressure on existing roads, particularly evident by its volume and noise, and the spreading edges of routes in attempt to accommodate passing and parking places. The majority of roads are minor and they may be single track. There are also a number of “honeypot” locations with Skye which are not prepared for the high influx of visitors at peak times, such as the Fairy Pools. Promotion of alternative, and equally photogenic, locations within the area may help with this in the future as there are still areas which are quieter.

Both land- and water-based recreation are popular in this area. Sailing and sea kayaking provide an alternative experience of the landscape. Walking and climbing continue to grow in popularity with climbing the Cuillin providing a unique experience within the UK and the area has a high density of both Munros and Corbetts. Mountain biking is also increasingly popular. Wild camping is enabled by Scottish access laws and this allows campers to experience the countryside more intensely but can lead to problems if not undertaken responsibly.

Wildlife tours, including a glass-bottomed boat, allow visitors to experience the marine environment, are run from both Skye and Lochalsh and more gentle outdoor activity is provided in the forest areas.

As within any area, an influx of ‘universal’ elements threatens the distinct character of place. This issue has been pushed to the forefront within Skye and Lochalsh, not only because of an increase of ‘incomers’ and greater services, but because of an actual physical change with the construction of the Skye Bridge. People are undoubtedly attracted to Skye as a distinct place, often at the expense of Lochalsh, whose identity is less clear from its geography. Although physical linkage may not necessarily destroy this distinction, reduced isolation tends to require compensating effort in reinforcing the landscape character in other ways, for example in a greater emphasis on distinctive design, community relationships and cultural characteristics.

Fishing and Aquaculture

Salmon and trout fisheries along the west coast have declined considerably. Much of this is likely to be due to factors at sea, but also the decline of riparian woodland and increased sedimentation in rivers. The seas off Skye and Lochalsh have been fished heavily and Kyle and Portree harbours host fishing fleets.

Aquaculture, producing salmon and shellfish, has increased, especially in more sheltered sea lochs. Their visual impacts are not only from the cages but the buildings associated along the shore. Recently a large fish food processing plant for the aquaculture industry has opened at Kyleakin providing jobs in a distinctive modern building.

Renewable Energy

As in much of the Highlands, the natural resources of Skye and Lochalsh are in demand for renewable energy generation, due to the high rainfall and wind, topography and low population density.

The combination of high levels of precipitation, with remote and deep upland valleys within this region, means that such areas are often utilised as water reservoirs and for hydroelectric power generation. There is considered to be potential for supplementing this further by utilisation of the wind, with the construction and development of wind turbines and windfarms. However, the highly valued scenery and distance from major grid infrastructure has meant that wind energy development has not been significant in much of the area. It is unlikely that demand for sites will decline in the foreseeable future so it is likely that other sites will eventually be used.

Hydroelectric schemes

There are two large schemes within this area from the hydroelectricity boom of the mid-20th Century. Storr Lochs near Portree was built between 1950 and1953 and produces around 28,000 KW per year. It is distinctive for the railway pulled up and down the cliff by a cable instead of an access road. Nostie Bridge scheme in Lochalsh was built in 1948 and produces 1.2 KW. These are still much smaller than their contemporaries in the rest of the Highlands.

There are a number of small and micro schemes. Some are built on the fast-flowing streams of the area and require little or no storage. They are often linked to industry, such as the distillery or small settlements. Others are linked to small dammed lochs.

Wind Energy

Similar to hydroelectric generation, turbine installation has been limited by access and regard for the high quality of the natural heritage in Skye and Lochalsh.

In Lochalsh and the south of Skye, there are small single turbines only, mainly in smaller settlements and individual farms. In the central part of Skye Ben Aketil and Edinbane windfarms have 30 turbines between them and approval has been given for another wind farm at Glen Ullinish.

Infrastructure – transport and communications

Travel infrastructure has been one of the most transforming influences on the settlements and landscape of Skye and Lochalsh. Until 1813 the area was very isolated with few tracks in and out of the area. The journey to Skye involved a small boat which reinforced its isolation and independence from the mainland and droving roads were the key to travel in and out of the area, for example, the road to Sallachy. As part of the military road building of the 18th Century, a road to Glenelg Barracks linked it to Fort Augustus and the other Highland garrisons. Ironically this was used by the Jacobite army in the final uprising to travel faster through the Highlands.

In 1813 Lochalsh road (Strome to Kyleakin Ferry) was built, this opened up the Kyle of Lochalsh harbour to goods transport in and out of the area, as well as travel to Skye.

The Railway to Strome Ferry opened 1870, and led to ferry terminuses to Skye and Lewis and associated infrastructure making it a much larger settlement. This line was extended to Kyle in 1898 and Kyle of Lochalsh took over as the main ferry terminal until the updated ferries of from the 1970s onwards took the shorter journey to Ullapool with a larger harbour capacity

Calum’s Road, on Raasay, was built by Calum Macleod mostly singlehandedly over 10 years to connect Arnish with the ferry at Inverarish and to stop the township dying out. He was much celebrated locally, as well as nationally, and both a book and tune have been written to commemorate his achievements.

Until 1995 ferries were the only way to reach Skye. Glenelg still operates a manually operated turntable ferry, which has taken cars since 1934, to Kylerhea. The Mallaig to Armadale ferry route, which has been used from at least 1173, is the closest point to the south of Skye and a ferry still operates, although it is less popular than previously.

In 1995 the Skye Bridge opened, linking the island with the mainland. It has opened up tourism and reduced the rate of population decline on the island.

Industry

Industry in Skye and Lochalsh is limited, and has been so throughout history. There are few large-scale industries, but artisanal size food and drink producers, including traditional smokeries and small-scale craft producers, are found across the area. Weaving, salt production and candle-making, for example, produce traditional style goods mainly targeting visitors to the area. Their impact on the economy and landscape are limited.

There are a number of distilleries producing whisky, and more recently gin, and a successful brewery which supplies establishments across Scotland. These use environmental factors, such as peat and water, as a production requirement, as well as a marketing tool to sell their product more widely.

Mining has been carried out on a small scale across Skye. A Diatomite mine produced silica but closed in 1960, and iron ore on Raasay was mined in the wars but was not economic in a peacetime international economy. Marble is still mined at Torrin to this day. The distinctive black, grey and white marble has been used across Scotland and globally, including at Versailles palace and the Vatican.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES AND PERCEPTION

Evidence of human occupation or activity occurs within the Skye and Lochalsh landscape, despite its vastness of scale and harsh physical environment.

Visitor Experience

Skye and Lochalsh attract and are intermittently dominated by large numbers of visitors. Although the immense pressure that these inflict is a relatively recent phenomenon, there has been a long tradition of people visiting the area, and particularly Skye. Their impressions of the area have typically been influenced by the fashion of landscape appreciation at that time.

The first detailed account of the natural history and people of the district was given by Martin Martin in the early 18th Century. Although a native Skyeman, it seems that he had little appreciation of the rugged scenery of his homeland. Likewise, most travellers to the area in the 1700’s tended to consider the landscape character as something quite horrid and intimidating, something to overcome. Thomas Penant, in 1772, described the Cuillins as “a savage series of mountains” and Samuel Johnson, again in 1772, wrote “a walk upon ploughed fields in England is a dance upon carpets compared to the toilsome drudgery of wandering on Skye”.

It was not until later on in the 19th Century that travellers really started to visit Skye and Lochalsh in search of the ‘romanticism’ of the Highlands, as depicted by Lord Cockburn, Sir Walter Scott and painted by Turner.

“…all below is beautiful, perfectly treeless, hard looking, and bare, but still capable of all the beauty that a bright sun can bestow on calm water, and on silent hills”. Lord Cockburn, 1841.

“ …The wildest glen, but this, can show

Some tough of Nature’s genial glow;

On high Benmore green mosses grow.

And heath-bells bud in deep Glencroe,

And copse on Cruachan-Ben;

But here-above, around, below

On mountain or in glen,

Nor tree, nor shrub, nor plant, nor flower,

Nor aught of vegetative power,

The weary eye may ken.

Foe all is rocks at random thrown,

Black waves, bare crags, and banks of stone,

As if were here denied

The summer sun, the spring’s sweet dew,

That clothe with many a varied hue

The bleakest mountain-side.”

Sir Walter Scott, extract from The Lord of the Isles.

Later authors, such as Gavin Maxwell, who wrote Ring of Bright Water whilst based at Camusfearna, continued to describe picturesque wildness. It has been built on by the area's depiction on screen, both in historic films and as a backdrop for mythical tales, like Game of Thrones.

It is this romantic combination of mountains, sea and sky which still tends to attract most people to the area, although this may change again in the future, possibly influenced by the current exponential growth of service provision. There is concern that the increase in tourist-related development can divert attention away from the traditional land-use practices which are responsible for the distinctive Skye and Lochalsh landscape, and may eventually result in the district becoming an indistinguishable tourist area, where the facilities rather than the place becomes the main focus of attention.

Gaelic Culture

The strong Gaelic culture of this district, and particularly of Skye, has undergone substantial change throughout history, mainly in response to changing political and social pressures. It has recently been subject to growing interest and activity in its retention as a distinct characteristic of the region, particularly through the promotion of the Gaelic language. Locally, this has perhaps been most clearly assisted through the development of Sabhal Mor Ostaig, the independent Gaelic college of further education set up in 1973 in Sleat, and more widely by the increasing popularity of Gaelic literature, prose, television and contemporary music.

The Skye area has produced a number of accomplished Gaelic poets such as Sorley Maclean and Mairi Mhor nan Oran. The latter was a 19th Century poet and nurse who wrote Gaelic verse and song to support land reform and protest against injustices, especially the clearances in Skye and the rest of the Highlands. Sorley MacLean was a 20th Century poet born on Raasay who wrote in both Gaelic and English about life in the 20th Century, including the impact of the clearances on Skye.

The concentration of this attention may to some extent be a ‘natural’ reaction to the rising influx of ‘incomers’ and visitors into Skye and Lochalsh, which may be perceived to dilute its traditional culture. However, the promotion of Gaelic as an intrinsic cultural characteristic of the district is clearly valued. At the moment this is mostly represented within the arts, and perhaps most evident within everyday life by signs, including road signs, and increased use in teaching. The future sustainability of this movement is not guaranteed; indeed, as within much of rural Britain, there is an increasing pressure on people to ‘widen their horizons’, becoming European and internationally orientated. This means that a fine balance will have to be made between celebrating the distinct cultural and landscape character of Skye and Lochalsh, whilst also embracing change, in order to prevent any isolation of the district

Gaelic place names

The names of places in Skye and Lochalsh are the most obvious experience of Gaelic to a visitor. Gaelic place naming is descriptive and can give a new understanding to experiencing the landscape.

Common words include Ach - field, for example Achbeg and Achmore: little and big fields respectively. Ard or Rubha indicates a promontory or headland. Glens and Straths describe to shapes of valleys with straths being wider and flat bottomed.

Hills have many descriptive names; creag or craig and carn (stony hill), cnoc (small hill), cnocan (knoll), meal (rounded hill) as well as beinn (high hill), monad (moor covered mountain) and aonach (a ridge). Craig generally indicates a rocky outcrop, for example Duncraig (Dun na Creige) means hill fort of the crag.

On such undulating terrain bealach indicates an important feature of the landscape, the hill pass. These prefixes are coupled with descriptive words, such as Dhuirich (dark), Dubh (black) or more sites specific such as Loch Innis nan Seaghan – Loch of the Isle of the Ants.

Norse influences on place names are also common with the area, and have evolved with the Gaelic influences of later centuries. Strome Ferry is thought to be derived from the Norse Straumr, a strong current, Fernaig is likely derived from the Gaelic for Alder, Fearn, and aig the Norse ending indicating a landing place or bay. Healabhal, Bheag and Mhor are thought to have derived from the Norse Helgi Fjall (Holy Fell) alluding to their altar like shape.

Other notable Norse names include Quirang – from Norse for Round Fold, possibly from the practice of hiding cattle here from raiders; and Eriskay is Norse, Erics-ey or Eric's Island. Kyleakin translates as “King Haakan’s strait” after the Norse king who was based here before the battle of Largs in 1263. There are a few remnants of earlier Pictish names within Skye although it is likely they have influenced the form of some of the later versions.

Landscape Perception