Landscape Character Assessment: Ross & Cromarty - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The pdf version of this document can be downloaded from the foot of this webpage.

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, include a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten.

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of:

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in the “NatureScot Review 119 – Ross and Cromarty landscape character assessment”, 1999, Ferguson McIlveen, and “NatureScot Review 90 – Inner Moray Firth landscape character assessment”, 1998, Sarah Fletcher.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

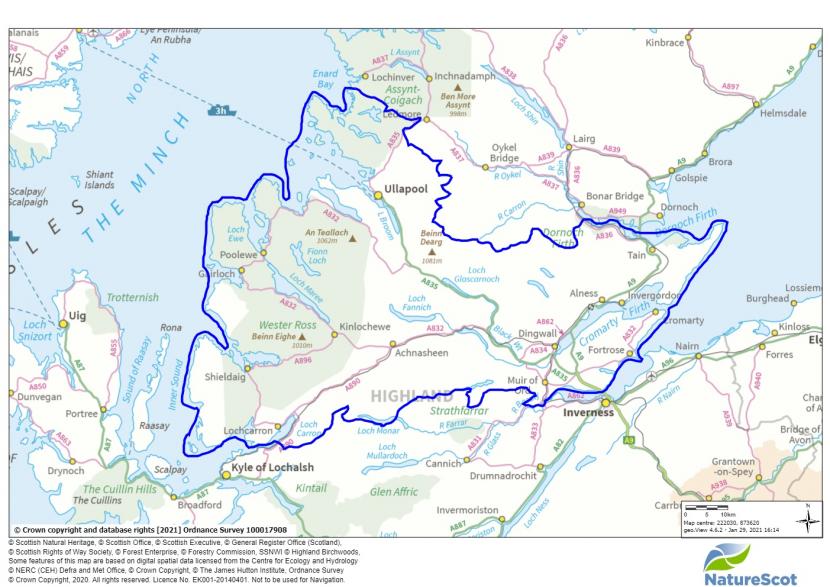

This document covers the Ross and Cromarty area, which broadly concurs with the former Ross and Cromarty District. It covers an area of 5,100km2 from the east to the west coast across northern Scotland but excludes Lewis and Skye which have been included in some historic boundaries of the area. It has a population of approximately 50,000 and forms part of The Highland Council area. It also incorporates information from the 1998 Landscape Character Assessment of the “Inner Moray Firth”, as this study provides information on the area from Inverness to Brora around the western edge of the Moray Firth.

Many of Ross and Cromarty's landscape characteristics are striking, particularly the varying scale and contrasting forms experienced travelling between east and west. The west coast is deeply indented by sea lochs that rise steeply to the adjacent high mountains, offering a striking contrast to the fertile plains and sunny slopes in the east. The landscape character of Ross and Cromarty is greatly influenced by time, seasons and the weather. There is a resulting sense of anticipation as a wide range of experiences and perceptions are encountered around every corner.

The mainland can be broadly divided into four areas. Easter Ross, the Inner Moray Firth, Wester and Mid Ross, each of which possess varying characteristics of scale, form, habitation and land use.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Geology and Hydrology

Landform

The areas of Wester Ross and Mid Ross at first glance seem to comprise almost entirely of mountain and moor. Closer inspection reveals an elaborate tapestry of mountains, hills, plateaux and moorland, into which is woven a network of glens, straths, channels, lochs and sea lochs. These landforms and drainage characteristics relate strongly to the geological and glacial processes that shaped the Highlands.

The formation of sedimentary Torridonian sandstone and Cambrian rocks with metamorphic Lewisian gneiss and schists resulted in a complex landform. The great displacements of these rocks are clearly displayed as exposed strata with other underlying geological processes expressed by cliffs, ridges and mountain peaks.

The mountain masses are the product of geological activity and glacial modification. During glaciation the whole region was enveloped in ice which moved west and north-west. This carved out large areas of rock leaving ushaped valleys and corries. Further evidence of glacial activity can be found in ice markings, the presence of boulder clay deposits, the assorted mix of moraine on valley floors and the formation of raised beaches around the coast.

There are essentially three varied landscape types in the North West Highlands. The dominant isolated mountain massifs of Torridonian sandstone, the rough mammilated surfaces (covered in rounded protuberances) that have developed on the Lewisian gneiss, and the complicated mountain and valley systems associated with the Moine Thrust.

There are spectacular peaks that are known for their distinctive light caps of Cambrian quartzite. The enormous size of these mountain groups is well illustrated by comparison with surrounding hills, moorland landscapes and the straths which extend far inland. In contrast to the large ranges of mountains rising from the coast there are isolated massifs formed from outcrops of Torridonian sandstone. There are also splendid examples of mountains that show the terraced arrangement of sediments. The high elevation and steep profile of these mountains, e.g. Liathach, is particularly dominant when visibility is clear.

In the transition between Easter and Mid Ross there is an area of glens, straths and streams dominated by groups of mountains. In the Tertiary period, schists were thrown into sharp folds. The tableland which developed had an eastward tilt, and the original drainage patterns produced the straths and three tributaries, which drain into the firths. Much of the ground is below 2,000 feet but there are 3 Munros (mountains over 3000 feet, or 914.4 metres, in height), all of which exhibit clear evidence of glacial erosion. The principal glens were made wider and deeper by glacial activity and now form important routeways to the north-west Highlands.

The north-central highlands of Mid Ross give way eastwards to a more gentle and open landscape. Easter Ross is a land of low, rolling hills and gentle farmland sweeping down to the sea, with a hill and mountain backdrop. In Easter Ross, wide shallow valleys and low divides form a landscape more akin to a low plateau which contrasts with the mountains which dominate the rest of the Ross and Cromarty mainland. The forested hills provide a strong form contrasting in colour and texture with the smooth underlying landscape.

The belt of richly cultivated land in Easter Ross overlays Old Red Sandstone. This strata forms a lower coastal zone with a patchwork of different land uses, backed by low mountains with distinctive rounded summits. This is a sedimentary rock and generally producing red to reddish soils, in some instances the mudstones can be grey or black due to the presence of organic material. This leads to blacker and fertile soils such as those on the Black Isle. The valleys leading down to the firths are characterised by wide terraces cut into fluvioglacial sands and gravel, indicating previous sea levels.

The geology is influenced by north-north-east trending faults, notably the Great Glen Fault, that continues from Inverness parallel to the coastline and then seawards into the Moray Firth from Tarbat Ness. Extrusions of Moine Metamorphic rock are found to the east of Beauly, north of Rosemarkie and Fortrose, continuing onto Fearn Peninsula in a band disrupted by the Cromarty Forth. Outcrops of Jurassic sediments are found running within this at Balintore, between Rosemarkie and Cromarty. The Jurassic and sandstone deposits have also lead to the presence of oil within the firth with oil platforms visible at the Beatrice Field.

Glacial Influences

In the Caledonian mountain building period (approximately 470 million years ago), it has been suggested that a large hollow formed in the region of the Moray Firth basin as a result of movement within the earth's crust. This ultimately produced the geological weakness caused by the Great Glen Fault and deepened the Great Glen which runs through from Fort William to Inverness. The fault can be recognised in the steep, straight, eastern coastline of the Black Isle and Tarbat Ness.

Many of the recognisable landforms of today had their beginnings before the last Ice Age, some 2 million years ago. In the period that followed (Pleistocene), the ice moved along existing lies of weakness in these landforms, and so began the development of many of the distinctive topographical features of Ross and Cromarty area.

The main ice sheet was centred over the northern mountain spine which ran from Altnaharra to Rannoch Moor, whence it spread westwards to the Minch and Inner Hebrides, and eastwards into the Moray Firth. The ice scoured out areas of weakness along existing valleys and formed deep basins such as those in the Beauly and Cromarty Firths. On meeting the main Scandinavian ice sheet, this ice was diverted east and north along the east coast, moving material from the floor of the firth up onto the land. The Wester and Mid Ross coast and mountains were sculpted by the ice flowing westwards. This carved out large areas of rock leaving ushaped valleys and corries. Further evidence of glacial activity can be found in ice markings, the presence of boulder clay deposits, the assorted mix of moraine on valley floors and the formation of raised beaches around the coast, for example at Gruinard Bay and near Beauly.

Upland areas

To the north, large areas of Lewisian gneiss have been moulded into convoluted landscapes consisting of small hills and hollows, referred to as “cnoc and lochan”. The thin soils and bare rock of the hills indicate glacial scouring while the hollows, produced by glacial erosion, are filled with peat or small lochs. The greater the scouring of the glacier, the deeper the valley. When submerged in the water the pronounced u-shaped valley had steep sides with a narrow coastal edge. Here the relationship between land and sea is sharper, giving an acute sense of enclosure and shelter. The lack of low-lying land associated with the coastal edge forces the main communication routes down to the shore, giving travellers the added experience of tidal change.

Further east the ice flowed over the lower land, rather than being confined as it was within the more pronounced valleys further west. This resulted in a shallower glaciated basin, with smoother, concave slopes, and provided a greater amount of land suitable for settlement and cultivation close to deep, natural harbours.

The ice began melting around 10,000 years ago and the firths were formed by the drowning of the glaciated valleys. Later, as more ice melted and the weight upon the land became less, the land lifted up revealing the firth shores and large deposits of sand and gravel which are still locally important features today (such as the Dornoch eskers). The uplifting of the land as the ice receded revealed an abundance of shoreline features, such as raised beaches and terraces.

The irregular coastal features around the Dornoch, Cromarty, Beauly and Inverness firths are glacial sand and gravel deposits left by outwash streams and later dissected by rivers flowing down the steep valley sides. These narrow firth edges and deltas provide a basis for land use and settlement.

Meltwater from the glaciers produced a range of small depositional features such as the many winding ridges of sand and gravel along the lower lands of the Moray Firth. Often the coastline is bounded by later depositional landforms, where extensive infilling at the edges of the firths produced a gently shelving interface between the land and sea. These are now the tidal mudflats along which expansive views can be gained inland towards the hills. Deposition by glacial rivers was responsible for much of the sands and gravel for the present-day beaches, dunes, spits and bars which are characteristic features of the dynamic edge of the outer firth.

The Coast

There is a distinct contrast between the east and west coasts of Ross and Cromarty.

The west coast has a rugged, deeply incised, fjord coastline, linking a series of glaciated valleys that contain deep penetrating sea lochs. Wester Ross is the indented strip of mainland to the west of the Cromarty watershed. It also includes the group of offshore islands known as the Summer Isles.

Despite the dramatic coastal landscape, much of the west coast is dominated by the mountains just inland, with roads and settlements crowded on to the sea edge. Beaches are less common but popular examples can be found at Gairloch, Achnahaird and Applecross.

In the east, the coast forms a gently shelving interface between land and sea with broad flat coastal edges of glacial deposits and soils that are punctuated by wide firths extending inland, progressively narrower. In the narrows of the firths, large estuarine flats have developed from sedimentation. The constantly shifting tidal mud flats, beaches, dunes, spits and bars give a dynamic feel to the east coast, intensified by daily tidal changes. The often extensive stretches of beach and mudflats diminish the inherent sensitivity of this transitory coastal edge.

Within the Moray Firth basin, two distinct patterns of coastal processes emerge due to the differing actions of the wind and waves. This is split loosely in to inner and outer coast environments. Both the outer and inner coastlines of the Firth are considered to be relatively stable, the inner coast being exposed to a low energy environment and the outer coast being rock dominated and resistant to erosion. The middle coastline experiences the most rapid rates of physiographic change with high levels of sediment transfer. Both the marine and coastal areas include economically important deposits of hydrocarbons, sand and gravel, metalliferous material and carbonates. Many also have considerable importance by providing essential conditions for spawning and feeding grounds for a range of marine organisms including fish.

In comparison to the inner firths, strong coastal winds lead to an increased movement of material by both wave and wind. The development of spits and bars along the southern shores of the Dornoch Firth are examples of the continuing migration of sediments by waves, and typifies the characteristically dynamic qualities of the outer firth. The transport of sediments over land by wind gives a wider dispersal of fine sediments and creates a flat open landscape, such as that at Morrich More on the south side of the Dornoch Firth. This highly mobile, dynamic landscape can be experienced not just visually, but by the smell and taste of salt, the movement of sand beneath the feet and the sound of the waves and sea birds.

The river estuaries of the Moray, Cromarty and Dornoch Firths punctuate the coast of the Black Isle and Easter Ross. These firths contain intertidal flats at a scale unique in Highland Scotland that support an enormous variety of wading birds and wildfowl, such as that found at Loch Fleet. The tidal range can be up to 3 metres which exposes vast stretches of mudflats twice a day. Deep infills of sediment occur, for example at Nigg Bay in the Cromarty Firth and at the head of the Beauly Firth. The inner parts of the individual firths consist of mainly silt- or mud-based sediment but seawards they become increasingly dominated by sand and gravel.

Hydrology

Water falling on the west Highlands will either drain east into the Moray Firth, for example the River Conon catchment via the Cromarty Firth; or west to the Minch such as the River Ewe catchment or the River Carron. Broadly, the rivers draining to the east are more mature rivers with defined flood plains in their extensive lower reaches. The rivers flowing west tend to be more in spate due to the higher rainfall and bare rocks in upland areas. The majority of the water starts in boulder burns which drain the mountain ridges and plateaux, often into lochs and bogs before the water makes its way to the larger rivers.

There are numerous lochs of various sizes. The larger ones follow glacial u-shaped valleys and encompass fresh water lochs, like Loch Maree; and sea lochs, like Loch Torridon, Loch Ewe and Loch Broom. There are some lochans, most commonly within the High Rocky Moorland and Plateau and Cnocan Landscape Character Types and within corries. These tend to be nutrient poor. There are a number of dammed lochs, such as Loch Luichart and Loch Glascarnoch, which utilise the high rainfall of this area to produce hydroelectricity, which modifies the rivers flowing from them. These follow the shape of the straths and basins but are distinguishable from natural lochs by drawdown margins around their shoreline and associated infrastructure such as access tracks, dams and pump stations. As well as electricity generation, these lochs are used for recreation.

The rivers, lochs, coastal waters and estuaries contained in Ross and Cromarty are considered good quality generally which is reflected in the variety of wildlife supported by them.

Soils

The soils in this area are typical of much of the Scottish Highlands. The highest and most exposed peaks and ridges have montane soils, whose restricted organic material, and loose and coarse texture maintains little vegetation cover. Steep slopes have immature soils, which are weakly developed and lacking subsoil. This type of soil (with a sandy structure) is also found behind sand dunes along the east coast. Lower slopes and moorlands have a mix of peat and podzol based soils. These include podzols and peaty podzols which support acid loving heather moorland, some rough grazing and forestry, and peaty gleys whose more waterlogged horizons mean that they are less useful for both grazing and forestry. There are scattered blanket peat bogs which are valuable as breeding grounds for birds and as a carbon store. These are more limited in extent than further north.

The west coast has poor farmland, predominantly suitable for forage crops and pasture and this continues into the straths such as Strath Bran, Strath Conon and around Kinlochewe. Towards the east of the area, humus-iron podzols are more useful for agriculture supporting a mix of improved grazing, crops and forestry. The Black Isle, actually a peninsula, is well known for its fertile soil and the area is one of the few extensive arable areas in the Highlands with oilseed rape and other crops noticeable in the spring and summer. Patches of higher quality soil also allow fruit and vegetable farming in this area. This soil quality spreads up the coast but declines in quality just north of Dornoch. Alluvial soils, especially in the Conon and Beauly flood plains, are also rich sources of agricultural soils but are much less common on the western side of the area.

Climate: Weather and Seasons

The mainland of Ross and Cromarty extends from the Atlantic to the North Sea. lt is therefore subject to two contrasting climates. On the west coast a mild maritime climate is experienced, mild enough for the tropical planting of Inverewe Gardens to thrive; on the east coast it is drier and colder. The lowest temperatures occur inland, away from the moderating influence of the sea, in valleys into which cold air drains. The low position of the sun in northern regions, in combination with the mountainous relief, creates large areas of shaded land. This can have a dramatic effect on the local climate. The northern latitude results in short winter days, compensated by long summer days with extended twilight.

A consistent stream of westerly Atlantic depressions bombards and lifts over the mountains of the west coast. As a result the weather conditions are predominantly cloudy with high levels of precipitation and relative humidity. This is reflected by place names - Loch Broom is derived from the Gaelic Loch a’Bhraoin meaning ‘lake of the drizzling rain’. Strong winds are frequent and tend to blow along the well-defined glens and straths.

The exposed coasts and open moorlands provide vantage points to watch the changing weather as it moves inland. The clean air of Ross and Cromarty gives good visibility in open weather. However, prevailing cloud with a very low base can shroud high ground and mountain peaks with hill fog, seemingly lowering the sky. The resulting low visibility can pose a hazard for motorists, hill walkers, fishermen and sailors.

On the west coast, the unpredictable conditions of the maritime climate mean that there is a relatively gradual seasonal change marked by changes in flora, fauna and land use. The in-bye land has an abundance of lambs displaying the arrival of spring, whilst the roar of the stags in the hills heralds the start of autumn. In autumn the landscape is aglow with the orange and brown hues of moorland vegetation, heather and grass species with bracken, rowan and birch in the low lying areas.

The climate of the sheltered east coast is well favoured, considering its northerly latitude. It is characterised by high sunshine totals relative to latitude, the average rainfall is well below average for the United Kingdom, and the proximity of the North Sea prevents the coastal temperature from being very low during winter. The change of climate of the coastal area to the high ground just inland can be surprisingly abrupt. Temperatures over high ground in winter can bear little resemblance to the equable regime on the coast, with a marked increase in frequency and intensity of winter snowfall.

Wind strength is markedly affected by local topography. Over land the roughness of the ground causes a decrease in wind speed relative to winds over the sea. Winds are predominantly from the southwest.

The coastal region of the Moray Firth exhibits two interesting weather effects – ‘fohn’ winds and ‘haar’, due to the proximity of mountains and the North Sea. When moist south-westerly winds pass over the high ground of central and northern Scotland they give rise to the 'fohn' effect by depositing most of their moisture over the high ground, then warming and becoming drier on their descent on leeward slopes towards the Moray Firth coast. Some of the highest UK winter temperatures have been recorded along the Moray Firth as a result of the 'fohn' effect.

‘Haar’ is a shallow sea fog caused by the moistening of relatively warm air over the cooler waters of the North Sea, including the Moray Firth. Haars are most likely to occur during late spring and summer, and occasionally are thick enough to produce some drizzle. Normally, the haar is shallow and tends to burn back to coasts during the day to allow some sunshine inland, before returning.

Over the next century the overall rainfall in Ross and Cromarty is unlikely to change dramatically, although the seasonal pattern is expected to. An increase in winter precipitation is expected as Scotland’s climate changes with a corresponding reduction in summer rainfall. This could lead to increased run-off in the winter and also damage to woodlands. The lower areas of Ross and Cromarty may become suitable for increased biomass cropping but the agriculture across the area is unlikely to change much, due to the upland nature and poor soils of the region. The peatland areas may change; in some area accumulating more peat due to the wetter winters but there may also be damage due to increased runoff from the stormier nature of summer precipitation. Changes in temperatures may lead to changes in species ranges for heather moorland and alpine plants, and there could be potential for an increase in wildfires.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

Human Settlement

The population of Ross and Cromarty is about 50,000 people within an area of approximately 5,000 square kilometres. (10/square km, compared to the UK average of 241/square km). Between 1981 and 1996 the population rose by about 4% and this trend has continued. The centres of population tend to be located along the east and west coasts, or within glens and straths associated with marine and agricultural resources. The majority of the population resides within harbour and service settlements or crofting townships.

The oasis of flat and fertile land on the east coast of Ross and Cromarty, with its largely mountainous backdrop, has led to a long history of habitation and cultivation. The shelter afforded by the mountains, coupled with the extensive fertile land and proximity to the sea, encouraged human activity as far back as 8000 years ago. Towns developed from the Middle Ages, tower houses were built on small estates in the 16th and 17th Centuries, and prosperous farms were established in the 18th and 19th Centuries. The cultural pattern developed gives a landscape character strongly influenced by the mosaic of field patterns, tree lines, woodland, settlement patterns and communication lines. This is a stark contrast to the backdrop to Wester and Mid Ross where the feeling is of the landscape dominated by natural forces with more recent human occupation squeezed into the edges. This is despite the soils and vegetation being affected by millennia of human interaction, and indeed it is not as clearly defined as it appears at first glance.

History

Mesolithic

The social history of Ross and Cromarty commenced around 8,000 years ago, with the earliest settlers of the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age). These people hunted wild animals, and gathered shellfish and other marine resources as well as plants for food. The Mesolithic record in Ross and Cromarty is distinct either side of the Moine Thrust, with the west coast activity typified by shell middens, such as that at Red Point on Loch Gairloch and at Shieldaig; and the east coast activity more represented by artefact scatters, such as at Muirtown on the Black Isle. However, the unifying feature of Mesolithic archaeology in Ross and Cromarty is low visibility, and very few sites are known or securely dated. While the visibility of sites is low, it is likely that many sites remain unidentified or have been damaged by erosion in the coastal reaches of the Wester Ross, as Mesolithic activity across the wider Minch is relatively well attested to, especially in the Inner Hebrides to the south. Coastal travel would have dominated in this period, and many shell middens, artefact scatters, and butchery sites may exist within coastal dune systems of on the raised beaches of Wester Ross. Across the east coast with its less incised coastline and heavily disturbed agricultural soils the Mesolithic record is even less visible, although again a reliance on marine resources across this period may have led to a bias in site location towards the coastal cliffs and beaches of the Cromarty Firth. The upland Mesolithic record is largely unknown.

Neolithic

The first farmers settled during the Neolithic (New Stone Age) around 5,500 years ago. A variety of archaeological finds and artefacts around the Moray Firth, although relatively slight in their physical imprint on the landscape, indicate that the fertile landscape was recognised from as far back as 5,000 years ago. Compared with the islands to the north and the coastal plains of Aberdeenshire, Moray, and Angus, the Neolithic record from Ross and Cromarty is sparse, although several studies of buried soils in upland areas, such as at Auchtercairn above Gairloch, have returned Neolithic dates suggestive of small scale ‘slash and burn’ agriculture. Several undated sites across the West Ross coast may be Neolithic, such as the undated shell midden at Mellon Udrigle, the Dog Tooth field boundary at Auchtercairn, and many of the upland cairns, but a more systematic survey and dating regime would be needed to clarify this issue. On the Black Isle and around Cromarty the extent of post-Medieval ploughing is likely to have damaged Neolithic sites, which we would expect to see largely within the crop mark record, again evidencing the impact which subsequent land use, dictated by soil types, has had upon the prehistoric record.

Bronze Age

Around 4,000 years ago the use of bronze and an influx of immigrants marked the beginning of the Bronze Age, typified in Ross and Cromarty by the upland and coastal hut circle record and the scatterings of burnt mounds across wetter areas, such as at Allt Thuirnaig on the Inverewe Estate. These Bronze Age people built monuments for their dead and these are still visible in some areas of Ross and Cromarty. The remains of the low circular foundations of the walls of the roundhouses where these people lived are common across the region together with evidence of arable fields and pastures where stock were grazed. Settlement patterns such as those near Gairloch at Auchtercairn, the Sand River and North Erradale, show a pattern of buildings on well-drained but sheltered land. The well-drained brown earth of the Black Isle have been heavily reworked in the post-Medieval periods and as such have damaged much of the archaeological record for the Bronze Age, but hut circles and field systems are still visible at Wester Brae. It is likely that the cleared areas created by these settlers were limited but the woodland clearance by humans continued until the 20th Century. This clearance, coupled with overgrazing and later climate change led to blanket peat growth, leading to the heath and moorland seen today in the uplands of the region.

Iron Age

As pressure on the land increased in the Iron Age (around 700 BC to AD 200), defensive sites, in the form of duns, forts and crannogs, were built on prominent and defensible locations within the district, for example Dun an Ruigh and Ruadh Dun Canna, both on Loch Broom. Due to the restrictive nature of the landscape, especially in the west, much previous settlement is overlaid by later occupation, thus good sites may show evidence of successive artefacts.

Some of the west coast duns, such as Dun Thournaig on Loch Ewe and An Dun on Loch Gairloch, are partially vitrified meaning that the stone of portions of their walls has been heated to the point of low-level melting. Vitrification is thought by some to represent a form of conspicuous consumption, as seen widely across the Cairngorm hillforts. However, this has not been substantively proven in Ross and Cromarty. The non-defensive Iron Age record is similar to that of the Bronze Age, with many hut circles and field systems indistinguishable from earlier counterparts until excavated. Aided by increased farming peat expanded rapidly in during the climatic changes in the Iron Age. Blanket peat expansion in upland areas between Dingwall and Ullapool has aided in the preservation of waterlogged Iron Age deposits and ancient land surfaces which present opportunities for paleo-environmental reconstruction. However, blanket peat expansion has also buried large areas of the landscape which may obscure Iron Age and earlier sites, leading to the perceived emptiness of upland areas.

Early Medieval

By the 3rd Century AD we know that the people over much of Scotland were called the Picts (Picti or Painted People) by the Romans, but actually represented by a mosaic of distinct cultures. Symbol stones carved by the Picts still exist along the eastern seaboard of Ross and Cromarty in Shandwick, Hilton of Cadboll, Strathpeffer, and Nigg. Pictish settlements such as Dornoch and Burghead date from 300 AD but have been mostly built over by later occupation. The Cave at Rosemarkie on the Black Isle also presented a well-preserved Pictish burial.In the 6th Century an increasing influx from Ireland, via the Picts of south-west Scotland and Celtic communities in Argyll, brought Christianity and a distinct land management strategy to the west coast which became distinct from the Pictish east. In the 9th Century, the Vikings began to colonise, leading to further changes in culture and the archaeological record across the region. The impact of the Vikings is most evident in the place names of Ross and Cromarty, for instance, Ullapool and Dingwall, but they were reputed to have settled over a large swathe of Easter Ross, including the Black Isle, and the west coast. The Viking record is visible at the ‘Ting’ site identified beneath the Cromartie Memorial Carpark in Dingwall, and is suggestive of a far wider record now largely erased by modern agriculture and settlement. Gaelic also fully established itself as a language in this period.

Medieval and Post Medieval

In the Middle Ages, a clan system was established in the Highlands, with the prize of land and titles to be won. Bloody battles were fought and the construction of castles expressed the power of the clans of the region. Tower houses are the most abundant castle form in this area. Some of the most impressive were mostly built above good harbours or along good routeways along the coast, but inland both prominent and less- immediately obvious examples can also be seen on islands and earlier crannogs on the larger lochs, which were the major routeways through the area. Medieval lords patronised church building and the flourishing of Gaelic arts and culture, which stamped its mark on the area and lasted until the present day. The dominant pattern of land division was organised as a runrig system, although in the southeast of the area it may date back to the 12th Century. Throughout this were 'fermtoun' building clusters, many of which persisted relatively unaltered until the 18th Century periods of agricultural improvements: remains can still be seen near Evanton of Drummond fermtoun. Dispersed throughout these areas were the landless poor who settled into a pattern of farming that aspired to self-sufficiency, with little commercial output. The abandoned settlements of the medieval and post-medieval people of Ross and Cromarty are also common across the district. However, the extensive medieval trading settlement was largely coastal, as evidenced at Cromarty itself, and is now largely covered by the subsequent coastal settlement. Grass grown rectangular footings of houses are associated with traces of field systems (rigs), and shielings, which were the dwellings of those who took cattle to higher grazings in the summer and can be seen across much of the upland areas of Ross and Cromarty where modern agriculture is untenable and as such has not damaged the preserved archaeological landscape. Both historically and in the present day, the system of landholding in Scotland (with relatively large areas of land often being held by a few individuals) has had a dominant influence on the evolution of farming technology and agricultural land use, and thence on the resulting landscape patterns, including the survival of the archaeological record.

Easter Ross and the Black Isle became prosperous due to their agricultural capacity and good links by sea to Moray and beyond. Fortrose, with its now-ruined cathedral, was described in 1693 as “the seat of law, divinity and physic”. This long-vanished ecclesiastical settlement has left its own legacy of medicinal plants which still survive in the local flora.

Following the defeat of the Jacobite rising of 1745 the clan system, which had long tied people together by bonds of mutual trust and kinship, was broken down. The chiefs became more akin to landlords, dividing the land and demanding rents. The vast interior tracts of land offered great scope for the introduction of sheep farming. What transpired in combination with the reshaping of land use patterns, poor harvests and economic alternatives, was a mass clearance of traditional town settlements, often by force, of people who occupied the interior land. This is evidenced by the remains of field boundaries and the footprints of dwellings in even the most remote moorland.

From 1780 - 1880 a period of estate improvement coincided with the Highland Clearances, both of which produced very distinct landscape patterns which often relate to specific types of terrain. The estates tend to be situated on the flat, valley bottoms associated with the river flood plains and at the heads of the firths. Agricultural improvements for the estates meant, in part, the planting and managing of lines of deciduous trees enclosing the fields, and policy woodlands around the large houses. Those who remained on the estates were confined to the very edge of the land, along the coastal fringe, and were often encouraged to take up fishing and the kelp industry. Ullapool was built as part of developing this industry but struggled with variable fish availability. The aim of the new crofting settlements, such as Gairloch, Upper Diabeg and the First and Second Coast on Gruinard Bay, was to provide subsistence farming for the tenants who would then also work for their landlords, although there were ideological differences between their creation, management and subsequently structure. This period of improvement also saw the laying of a number of planned villages and towns, such as at Ullapool by the British Fisheries Society. These planned towns were intended to attract skills and trades from the economically and technologically more advanced Lowlands, to introduce civilization and industry, and as well to serve to the needs of the increasing local gentry.

Crofting as a land use on and near the east coast is relatively sparsely distributed on the poorer, steeper terrain of the valley sides. Although the soils are thin, they are also free draining, though much stone often had to be cleared to produce workable land. Many of the croft holdings are arranged in a strong geometric pattern, specifically planned to accommodate those who were 'cleared' from the inland straths. As such the crofting areas tend to have a highly populated appearance with a scattered abundance of croft houses and other buildings. The contrast between the two lifestyles of the crofter and estate owner is almost tangible in the contrasts of these two landscapes; the mature trees, large fields and big houses as compared to the rough, highly diverse nature and intimate scale of the crafting landscape. Planned settlements from the clearance of large estates, evident in the regularly laid out estate village of such as Evanton, were also built to house those removed from the land to make way for sheep farming.

However, the insecurity of the tenancies meant that management and improvement was weak in many of these settlements, and the land in many fringe areas became degraded and infertile. Many emigrated throughout the empire, while those who remained faced destitution. The cattle grazing in the west of the area was much in demand as the 18th and 19th Centuries progressed. This lead to the wholesale movement of cattle (droving) from the area to large markets at Falkirk and Crieff and then on south. In the east of the area, grain was predominant and this was shipped south, even during the famine years when potato harvest failed, and rioting ensued in 1946 as grain was continuing to be exported despite crop failures.

Land clearances did not ease up until the Crofters Holding Act of 1886, when crofters earned security of tenure, although this did not apply to previously lost lands. It is still possible to see the relics of enclosures and ridges in certain light conditions and from elevated viewpoints.

Population decline continued through the 20th Century. Predominantly young men left for England, USA and Canada and Australia, leaving women, the elderly and children behind. These Highland communities were hit hard by the First and Second World Wars. The small size of the communities, the gender bias of emigration and regional recruitment areas for infantry regiments, such as the Queens’s Own Cameron Highlanders and the Seaforth Highlanders (later merged into the Highlanders), meant that the Highlands and Islands suffered some of the heaviest losses, proportionally, in Britain. The emigration of young people continued to be a feature of the rest of the 20th Century. However, the population change slowed due to increased life expectancy and a slightly higher birth rate during the post-war baby boom. Fertility rates dropped in the same pattern as the rest of the UK through the remainder of the 20th Century and into the 21st Century but this has been evened out by increases in life expectancy. Ross and Cromarty area now have a density of 10.6 people per square kilometre, much lower than the Scotland average of 68.4, but above the Highland average of 9.1. This population is concentrated to the east and west with few people living in the central parts of the area. By the late 20th Century population decline was reversed and between 2003 and 2013 an increase of 8% was experienced, although the 16-44 year old age brackets remains lower than Scotland as a whole.

The east and west coasts of Ross and Cromarty, chosen strategically for their sheltered inlets, were occupied during the First and Second World Wars and during the Cold War. Invergordon was a major naval base and Loch Ewe was the point of departure for the Arctic Convoys. There are nationally significant remnants of cultural heritage in the form of fortifications and observation towers along this area and activity is still common in the west. The flatter east coast was important for aircraft, and there are remains of airfields and infrastructure at Tain and Fearn. Tain is still in use today. (See Military Influences section below).

In 2005 the Assynt foundation bought two estates, Glencanisp and Drumrunie, in the north-west of Ross and Cromarty, as a landmark community purchase under the 2003 Scottish Land Reform Act. This was hailed as returning the Highlands to the people who lived there and the estate management has sustainability as a focus. Community land purchase and management is now a feature along the west coast of Scotland and the islands and is likely to increase.

Landcover

Woodland and Forest

Isolated patches of broadleaf or native pine woodlands are found along the coast, mainly occurring around the edges of coastal lochs and bays. The interjections of these rare fragments of woodland provide surprising focal points and intermittent framed views along the winding coastal roads. The sparseness of woodland in the area strengthens the visual awareness and appreciation of its form, habit, and colour. The woodlands predominantly comprise birch but there are also oak and hazel species and occasional pockets of aspen, willow, pine and rowan providing visual diversity. Areas of native Scots pine also occur as relics of previous extensive woodland cover. Individual trees stand solitary on steep slopes with occasional larger areas fenced off for protection. The tall, reddish coloured bare trunks and dark, layered canopy are distinctive landscape features. There has been extensive native woodland replanting in areas such as Beinn Eighe National Nature Reserve, Torridon estate, and the shores of Loch Maree. In some cases this is replacing plantation conifers and in others, planting on moorland previously managed for game. Inland, woodland follows the straths with more extensive planting to the east of the area north of Contin and Garve, this is predominantly planted but there is native woodland interspersed within it. In addition to plantations and native woodland, there is scattered estate policy woodland, for example, Poolewe associated with Inverewe Gardens and around Torridon.

In the east, the presence of large-scale forests is characteristic of many upland and coastal locations. Although much of this relates to the formation of the Forestry Commission at the beginning of the 20th Century, and their large areas of pre and post-Second World War plantings; there are also considerable areas of longer established estate woodland. One of the main features of these woodlands is the predominance of exotic conifers which are capable of withstanding exposure and growing successfully on poor acid soils. Their distribution tends to be on the upland areas of peat, on rocky slopes, and on heaths associated with the dune systems, where forestry was originally introduced to curb coastal erosion.

Bog woodland can be found at Monad Mor towards the western edge of the Black Isle, a Special Area of Conservation with kettlehole lochs and sphagnum lawns.

Oakwood, such as that found at Drummondreach Oakwoods, is found in more acidic areas with ash and elm woodland more common in the outcrops of more calcareous rocks, for example around Rosemarkie.

Heathland

The heathland of Ross and Cromarty is extensive and undulating. There are subtle variations in texture, isolated rock outcrops and lochans. Changes tend to be seasonal in colour, especially of the heather. There are areas of sporadic native woodland and forestry plantations dotted throughout with access tracks linked to the latter. Power lines are common in lower-lying and more accessible terrain which tends to also be the focus for main transport links. Overall the moorland of Ross and Cromarty gives a sense, however inaccurate, of an absence of human activity and remoteness. To the west the moorland stretches to the coast although the most undisturbed is inland. To the east it is replaced by agricultural land, especially grazing land.

Peatland

Peat is predominantly the product of human farming and climatic change in the Iron Age. It has often been extensively managed and exploited for fuel and other materials. Inland peatbogs and fens are common, especially upland of Kinlochewe and north of Loch Glascarnoch.

Peatbogs are common in the Cnocan landscape in poorly drained basins. They are not widespread across the area but have an important role in carbon storage, flood management and as a habitat, especially for breeding birds and plants.

There is extensive peatland in the interior of Ross and Cromarty, much of which has little human impact evident and is classified as Wild Land Areas. Deep channels carved into the peat by running water can make moving through these areas difficult and emphasise their wild character.

Closer to the west coast, lowland bogs and heathland are extensive between Loch Gairloch and Loch Ewe but more common inland. Bogland is less common to the east of the area but salt marsh and mudflats can be found in the Dornoch, Conon and Beauly Firths.

Grassland

Unimproved grassland is limited and most is cultivated for agricultural use. Semi improved pasture is common in the lower land to the east of the area, where arable farming increases in lowland areas, and along the coast where it is linked to crofting settlements. Upland grassland is fragmented and mostly found within sheltered areas adjacent to montane habitats. It is popular grazing for deer and mountain hares.

There are limited dune systems and associated grassland along the coasts, for example around Big Sands near Gairloch.

Montane Habitats

The rugged character of the mountains of Wester Ross leads to a montane habitat on the peaks, interspersed with upland grassland and peat depending on the topography. Trees are sparse and malformed, and grasses, heathers and mosses predominate. Blueberry is also a common sight. The exposed peaks have less vegetation, again with mosses and lichens common on the rocky ridges and scree. As well as alpine species the rocky peaks and glacial features like corries are important for nesting birds such as Golden Eagles.

Landuse

Although an initial glance at much of Wester and Mid Ross would indicate a landscape unutilised by humans this is far from the truth. Very little of it shows no trace of human impact, even if this is evidence of abandonment, and much is managed in one way or another. Easter Ross, Black Isle and the east coast show their uses more obviously and have a more settled aspect, in places even industrial in nature.

Agriculture

The majority of Ross and Cromarty is limited to rough grazing of poor quality due to the intractable physical limitations of the geography of the area. It is consequently not profitable to farm. Only a very small area in the lowland east is deemed capable of supporting mixed and arable agriculture. In the coast areas of the west some improved grassland exists which is the basis of the crofting communities situated there.

In the west, crofting still determines the landscape and settlement patterns. The crofting townships are located near to the coast, or as small pockets within straths, as these places tend to offer favourable microclimate, access and drainage conditions. Crofting on the east coast is sparsely distributed, for example on the slopes around Muir of Ord. The pattern of the crofting landscape is one of the most distinctive in all of Western Europe. It comprises regular small landholdings, the townships arranged in a strong geometric pattern and the scatter of croft houses with common grazing. However, this pattern now appears to be losing its distinction, as old cropping practices have been replaced by an increase in sheep farming and larger landholdings, encouraged by the provision of farm subsidies. The Crofting Commission is charged with overseeing the practice of crofting by administering schemes that offer various forms of financial assistance.

The large rural estates, situated on fertile lowlands and extending onto the hill ground, have big estate houses and outbuildings, large fields of rich pasture land and mature woodland. They offer a sharp contrast to the 'rough' and diverse nature of the crofting landscape. The estate landscape has a long tradition of occupation, with its managed appearance tending to add a positive image to the landscape; however, the estates are now increasingly non-profitable. Landowners are turning to external funding from agricultural and forestry subsidies and grant schemes, with sporting recreation activities proving to be an attractive money maker. As a result of the activities associated with these land uses, greater pressure tends to be exerted onto the landscape, such as heavy grazing by sheep and deer. They are often the focus for a number of smaller dwellings, traditionally linked to the estate and workers but often independently owned now. Easter Ross, Moray Firth and the Black Isle support improved pasture, mixed grazing and cultivated arable land, especially cereal and potatoes, mixed with woodland and plantations in a productive mosaic. Close to the coast, on the Black Isle, and within the alluvial river soils there are areas of very good soil fertility where a range of crops can be grown with the mild climatic conditions even allowing soft fruits in some areas.

Forestry

Large-scale conifer forests dominate some parts of the region, particularly the straths of the central area and the eastern margins of the uplands. The introduction of these and associated access routes, and overhead power line routes, into moorland areas channels movement along the main routes, which are often situated in the more favourable, low-lying moorland terrain. In the east, there are also extensive areas of established estate woodland, which contain a predominance of successfully growing exotic conifers. Forestry has proved to be a useful provider of employment in some parts of the region, but changes in technology, and forestry and farming techniques, led to a decrease in the numbers needed to sustain this land use. Forests were established in the 18th and 19th Century however forestry really took off as an industry after the First World War (the Forestry Commission was formed in 1919 to ensure a timber supply in the event of another conflict). Initially, this was in the form of dense plantations, many of which are still maturing but since the 1980’s the approach has been more focussed on the multiple benefits of woodland, including more native species and natural structures, rather than just commercial value. The private sector has lagged in this move but now much more of the financial assistance available is focused on enabling this shift. One result of this is a reduction in clear-felling areas.

Fishing

Fishing continues to be an important economic activity in parts of Ross and Cromarty. The harbour settlements, which arose due to this industry, are confined to sheltered lowland areas along the coast. On the west coast the harbours vary considerably in scale from large ferry terminals to small jetties supporting the local industry. On the east coast the smaller facilities contain concentrated hubs of activity with a myriad of forms, colours, textures and movements that entice visitors. In Wester Ross, Ullapool has gone through a number of reincarnations since its inception as a herring port and subsequent decline. In the 1980’s and 1990’s it became the hub of a massive autumn mackerel fishery. As well as many fishing vessels, numerous massive 'klondyke' factory ships from Eastern Europe were anchored around Loch Broom, processing the local mackerel. With the decline of mackerel, Ullapool is mainly a whitefish and seafood harbour now, while also supporting the fish farming industry along the coast. Evidence of fishing is found along the coast with ice houses and fishing stations, such as that at Red Point, now falling into ruin as smaller fishing communities shift away from the industry.

Aquaculture

Along the west coast of Ross and Cromarty, fish farms, predominantly for salmon and shellfish, are a common sight. They are found in both freshwater and sea lochs and the rafts and buoys can be highly visible against the water depending on their location and the number present in the area. There may also be associated shore development, such as jetties and sheds. This industry has expanded in recent years with Scotland now the third largest producer of farmed salmon in the world. It is economically important for the area, in part replacing the decline in fishing income, although critics point to the low numbers of employees and there are concerns about the environmental impacts of farms. Aquaculture is more limited on the east coast although mussels and cockles are harvested there.

Settlement and Transport

It was as early as the 12th Century that agricultural development favoured the growth of small urban centres to act as trading marketplaces. These burghs continued to be formed, creating a hierarchy of settlements, up to the 17th Century, after which urban growth began to stabilise. In contrast, from then until the late 19th Century, fishing settlements experienced a period of pronounced growth, in response to the herring fishing industry.

Patterns of settlement, establishment and growth are strongly correlated to the growth of communications. The restrictive topography of Ross and Cromarty has resulted in a sparse network of roads through the region mainly running along straths and the coast, thus preventing access into the mountainous interior, which retains its distinctive uninhabited nature and sense of remoteness. In contrast, the east of the region, with flat land and easy access by land and sea to Moray and beyond, has remained more prosperous. The importance of the sea as a means of communication is apparent with the growth of small tightly knit settlements crowded around harbours at strategic coastal locations. Later, settlements became associated with the crossing points of the firths, with bridges at the heads and ferries at the mouths and natural crossroads in the landscape, like Achnasheen.

Many existing roads were built upon past droving and military roads, put into place by General Wade as part of controlling the Highlands after the failed rebellions. The road from Contin to Poole, including the distinctive Little Garve Bridge, was part of this building program. The modern period of road-building began with the 1803 Act for making Roads and Bridges, and much of this early work was directed by Thomas Telford, including the ’Bridge’ at Bonar Bridge. The Garve to Ullapool road is known colloquially as the 'Dirrie More' (Gaelic: 'an Diridh mer' - the great ascent), because of its rise to over 274 metres above sea level. It is also known as 'Dithreash Mer' (a great wilderness) because it winds its way through bare and barren land for miles. The reconstruction of the roads to Ullapool and Gairloch during the 1960s did much to reduce the isolation of Wester Ross, and greatly facilitated the growth of tourism in this area. The completion of new road links has generally increased accessibility into the remoter districts.

To the west, the largest settlement is the harbour town of Ullapool. It was initially designed by Thomas Telford as a modern village and port for herring fishing for the British Fisheries Society in 1788. It was also one of the leaving points for ships to Nova Scotia during the Highland Clearances. It developed around the fishing industry, both as a port and with processing facilities, and is still the main service, tourist and fishing hub for the area. Ullapool still rates as one of the top 10 fishing ports in the UK, although its reliance on the industry is softened by tourism.

The other settlements along the west coast are smaller fishing and crofting settlements, many redesigned and enlarged during the restructuring of estates during the 18th and 19th Centuries, such as Shieldaig and Poolewe. Settlements in the interior are limited and generally focussed on lochs, rivers and natural junction points along the routes to the west, such as Achnasheen and Garve.

With increased heavy haulage, tourist traffic and private cars, the existing network of roads are under great pressure and deteriorates easily. The passing place system can be slow, especially in summer, and in winter they become easily snow and ice-bound. The increasing trunk road network alters the perception of the landscape as it allows the visitor to pass through the landscape at much higher speeds. In the latter part of the 20th Century the construction of the A9 northwards from Inverness via the Kessock, Cromarty and Dornoch Firth bridges has had a profound effect on the landscape character of the Black Isle and Easter Ross. The bridges spanning the firths have radically changed the focus for the location of new housing and industrial development. As a further consequence, interaction with the firths on a human scale has been lost, as more dramatic yet detached views can be gained by taking the shorter and quicker route.

Road access between the east and west is limited and focusses on two main routes through Strath Bran and Strath Oykel. The roads in the West are limited and generally single track or narrow and concentrated on the coastline. The dramatic and poor quality of the roads is, in some cases, celebrated. The steep Bealach na Ba is marketed as a challenge to cyclists and an opportunity for spectacular views for those with powerful engines alike. The east side of Ross and Cromarty has more and better quality roads due to its proximity to the denser population around the Moray Firth, focussed on Inverness.

The railway did not have the transformative effect that it did further south due to the limitations of tracks built. However, the Inverness to Kyle of Lochalsh line linked Skye and Inverness directly for the first time. There were plans for a branch line between Garve and Ullapool which did not come to fruition due to lack of funds, arguably holding back the northern part of Wester Ross in the development of both tourism and a larger fishing industry.

The Inverness to Kyle of Lochalsh line is not only used as local access but is considered a scenic route, which makes it much busier in the summer months. The train line north to Thurso and Wick serves a similar purpose but the stations closer to Inverness are more commonly used for commuting purposes and the station reopening at Conon Bridge, 50 years after it was closed, reflects this.

Manufacturing, Mineral Extraction and Industry

The presence of the whisky distillery (using the peat filtered water from the surrounding hills and the good barley ground) as a recognisable architectural feature increased after the 1814 Act of Parliament. This defined a certain production capacity in an attempt to stop illicit trade. There are several well-known distilleries in the area, including Balblair at Edderton, Glen Ord at Muir of Ord, Glenmorangie at Tain and Dalmore at Alness.

The building of the Invergordon aluminium smelter and the discovery of oil in 1976 can account for the most rapid and visually dramatic growth of settlements and industrial areas in today's landscape. The ports at Nigg and Invergordon have expanded to accommodate this industry as well as turbines and other requirements for the growing renewable industry. Oil rigs in various stages of reconditioning are a common sight within the Cromarty Firth and further from the coastline.

Taking advantage of the deep waters of Loch Kishorn on the west coast, Kishorn Port was built in the 1970s to construct the Ninian Central oil platform, and other platforms for the North Sea oil field. It was closed in the 1980s but it has now been reopened for the manufacturing, laydown, and assembly of renewable energy devices for offshore wind, wave, and tidal sectors, as well as oil and gas, and decommissioning services linked to these industries. Invergordon is also now equipped to moor large cruise liners which increases the revenue of the port, but has limited economic effects on the surrounding area as the visitors are bussed to Inverness and other attractions.

There was limited iron working from bog iron ore fed Red Smiddy, near Poolewe, which was the oldest iron blast furnace in Scotland (1610 – 1670), and potentially other small scale furnaces. Mining around Kishorn for iron was short lived as the veins were deemed too irregular for exploitation. Copper was mined in the Kishorn area too, with Rassal mine the best known. It was definitely in production in the mid 1700’s but was abandoned by the early 20th Century.

There are local rock quarries, for aggregate and building stone, around the area, including near Ullapool (Limestone), Achilty (igneous/metamorphic) and Kishorn (Sandstone). There has also been peat cutting historically, but this has been local and mostly small-scale.

Military influences

As previously discussed, the First and the Second World Wars, and the Cold War, saw installations set up on both the east and west coasts of this area. The Cromarty Firth inlet was a vital component of the UK’s defence system which extended from Shetland to Cornwall, and was one of the main naval bases, with the oiling / refuelling station and port at Invergordon. The expansive oil tank farm at Seabank is still visible. At the entrance of the Firth, to the North and South Sutor headlands, there are the remains of gun batteries providing protection from seaward attack. The Sutor batteries were reoccupied in the Second World War, and the survival today of many of the ancillary structures at South Sutor, in particular, makes this the most complete surviving coastal battery in Scotland. The Firth was, in the later part of the First World War, also the home of a US Naval Base and a key site for the assembly of components for laying the North Sea Mine Barrage. There are some good examples of First World War training trenches, cut into the landscape at Rhicullen and Broomhill. There are very few surviving First World War training areas within Scotland, which would have been relatively common during the conflict.

The flat land and good climate on the east coast meant that RAF facilities and airfields were built for good access to Scandinavia and the North Sea. Remnants of these survive in the area, with control towers and decaying huts still visible, although mostly now surrounded by farmland again. Tain and Fearn peninsula is still in use as a training range for both British and NATO exercises and the low flying aircraft can be quite noticeable during busy periods.

On the west coast, the landscape at Loch Ewe provided the perfect setting for a strategic naval port and was used as a temporary base for the Home Fleet during the Second World War. Loch Ewe is probably most significantly known as being the assembly point for the convoy of ships sailing in the 1942 Artic Convoy to Murmansk. As with the Cromarty Firth in the east, there are a number of associated defensive coastal batteries and military campsites that survive to the west. The area remained in military use during the Cold War by NATO as a maintenance, refuelling, and servicing depot for nuclear submarines. The area is still in use for refuelling submarines today.

Renewable energy

The Highland area has good conditions for the production of renewable energy and, as a council area, energy production from renewable sources generally exceeds consumption.

Linked to energy production in this area, high voltage lines and pylons are common features creating strong visual focal lines. In general these follow the main transport routes and strath floors. To the very east of the area there are lines and transmission stations associated with the Beauly Denny power lines, but these lead to the west of the area so their impact is limited. Communication masts are also common, especially close to settlements, and are generally prominent on higher ground.

Hydroelectricity

The high levels of precipitation and characteristic deep upland valleys and lochs in Mid and Wester Ross were recognised in the early 20th Century for their potential in developing hydroelectricity. In the course of development, new dams and power stations appeared in remote glens, and new lochs were impounded, modifying the local landscape and inundating some valley bottom grazing. More recent smaller run-of-river projects have renewed interest in the harnessing of the water power resources of Ross and Cromarty, for example on the south side of Loch Maree.

Large schemes were built during the 1950s and 1960s as part of a large-scale attempt to control the water in the area. These schemes are typified by large dammed reservoirs and storage connected by tunnels through the hills. In Ross and Cromarty, the Conon Scheme, although building on a smaller scheme started in the 1920s, was the most ambitious, being built between 1946 and 1961. It has 104.6MW of installed capacity with water passing through three opportunities to generate electricity. Work at the large Garbhaig Hydroelectric Scheme more recently has resulted in track lines and felling at Victoria Falls on the banks of Loch Maree.

Smaller schemes, such as those at Flowerdale and Letterewe on Loch Maree have been installed in the last decade. These often serve remote settlement clusters or feed into large schemes close by. Some of these are run-of-river, requiring no storage capacity, which may have less visual impact.

The artificial lochs created by hydroelectricity are identifiable by the imposing dams, draw-down zones of bare rock and buildings. Despite this, many are used heavily for recreation and are often considered to be scenic.

Wind Energy

Due to the protection afforded by the National Scenic Area designations, and the difficulties in accessing much of Ross and Cromarty, there are less large scale windfarms in this area than across the Highland Council area in general. Lochluichart is an exception to this. Novar to the north of Ben Wyvis is another prominent wind farm. On the eastern side of the area Beinn Tharsuinn and Fairburn are much smaller, (20 turbines) but are highly visible from the lower land to the east. There are a number of micro turbines built predominantly along the coasts but these are limited, more common on the more settled east, and generally built for domestic use.

Tourism and Leisure

Tourism is an important part of the economic stability of the Ross and Cromarty area. About 35% of employment is related to tourism in some way.

Visitors have been attracted to the area since the late 18th Century. The town of Strathpeffer is a planned village intended for tourism, and this is evidenced in the character of the architecture. Designed in 1806, and redeveloped in 1860, with the spa there being Scotland’s only remaining natural spa. The pump room here was built in 1819 and expanded throughout the 19th Century. The building of the railways and railway hotels brought visitors to the Highlands and, although less popular than the area south of Inverness, estates in Ross and Cromarty were nevertheless attractive for hunting and fishing.

During the 20th Century, despite the closure of many branch railway lines, the emergence of the car made the area more accessible for visitors and it became an attractive destination for outdoor enthusiasts. Developments such as the North Coast 500, a road trip around the north coast of Scotland, were brought about to further develop the tourist industry in the area and have increased vehicle traffic and cyclists visiting in the last few years.

Pressures over demand for housing and visitor accommodation, and increased traffic on the roads, have been present in this area like any other region reliant on tourism, exacerbated by the narrow roads in rural areas. With the gradual increase of population in the region, traffic travelling south to Inverness over the Kessock Bridge is becoming busier, resulting in an increase in demand for office and workshop accommodation north of the bridge.

On the coast of Ross and Cromarty, golf is a popular leisure activity with courses at Dornoch, Rosemarkie and Tain notable. This can cause conflict with conservation concerns as dunes and link areas are desirable for golf course development.

Within the recent surge of visitors, and because of the good access allowed by the Scottish access laws, adventure sports such as long distance walking, mountain biking and canoeing have become more popular. These can bring specific pressure on the landscape, including localised erosion, parking requirements in more remote locations and the impact of increased wild camping. There are also seasonal impacts related to busier roads and beauty spots, and the use of parking facilities and laybys for camping and camper vans.

Protected Places

Ross and Cromarty has three National Scenic Areas within its boundaries; Wester Ross which is wholly contained within the area, Assynt and Coigach of which only the southern part of the NSA is covered, and Dornoch Firth at the north east edge of the area.

The special landscape qualities of Wester Ross National Scenic Area, such as the dwarfing of human settlements by the vast natural backdrop, the contrasts and interplay between the expansive moorland, distinctive and magnificent profiles of mountains, woodland and the coastal views, are resonant of the western part of Ross and Cromarty. The wild and remote nature of the inland landscape and the iconic views of Loch Maree and Slioch, Bealach na Ba and An Teallach are an important part of the identity of this area.

Assynt and Coigach National Scenic Area has more rugged qualities and distinctively shaped peaks like Ben Mor Coigach, Cul Mor and Stac Pollaidh rising up out of the surrounding moorland, lochans and morainic hillock. Its coastline is fragmented up by scattered islands, such as the Summer Isles, and long narrow sea lochs.

Dornoch Firth National Scenic Area is dominated by the ever-changing firth and the tranquillity of a relatively undeveloped coastline. The contrast between the enclosure of the firth by moors and hills to the west and the expansive sea views to the east as well as the ordered inhabited farmland on the flats with the wilder hills behind are important to the experience and the variety of woodland, alluvial land, dunes and links mean that there is a full experience of the area to be had in a national scenic area.

Ross and Cromarty contain at least part of 7 Wild Land Areas. Towards the north, Rhiddoroch – Beinn Dearg – Ben Wyvis and Inverpolly – Glencanisp straddle Ross and Cromarty and Caithness and Sutherland districts. Coulin and Ledgowan Forest, Applecross Flowerdale- Shieldaig-Torridon and Fisherfield-Letterewe-Fannichs are all wholly with in the area and Central Highlands Wild Land Area is split between Inverness District and Ross and Cromarty. They are large inland areas with few tracks and paths entering their interior, and are mostly experienced by glimpses in from the roads on their periphery. Although rugged, the coastal areas are mostly excluded from these areas as the geography and population distribution mean that human influence is concentrated in these areas.

The north western edge of the Ross and Cromarty district is part of the North West Highlands Geopark. This is a UNESCO designation, recognising the aim of managing outstanding geological sites and landscapes in a holistic manner, and achieving sustainable development through this. It is one of only 150 worldwide.

Special Landscape Areas (SLAs) are regionally valuable landscapes identified by The Highland Council to protect and enhance landscape qualities and promote their enjoyment, and are formalised in the development planning system:

- Fannichs, Beinn Dearg and Glencalvie SLA is an extensive area of mountains and moorland on both sides of the main Garve-Ullapool road along the Dirrie More, stretching between Loch Glascarnoch and the head of Loch Broom. It includes the range of hills south of the road commonly known as the Fannichs along with the loch of that name. To the north of the road it takes in a wider sweep of country into the Caithness and Sutherland Character Assessment area. The SLA also includes the Corrieshalloch Gorge and most of the low-lying Strath More which runs between the gorge and the head of Loch Broom.

- Ben Wyvis SLA encompasses the rounded summits and foothills from Loch Glass to Little Wyvis. The Ben is a dominant landmark in the area, including from Inverness, due to its separation from the main mountain areas to the west and north. It is also designated a National Nature Reserve.

- StrathConon, Monar and Mullardoch SLA is an unbroken tract of remote interior hills (North half only, south is part of the Skye and Lochalsh). It comprises extensive moorlands and hills which are difficult to access. The SLA has dissected mountain massif, large scale water bodies and a strong sense of wildness.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES AND PERCEPTION

Landscape Perception

At the coast, the juxtaposition of land and water produces a variety of forms, textures, lines and colour. In some places, gently sloping land falls to the coast, gradually fading into a sea/land/sky interface, whilst the mountain massifs can form dramatic vertical edges of land, abruptly dropping into the sea, like walls of rock. Seldom far from the sea's influence, the intermingling of water and land in Wester Ross creates a variety of views, although the many radiating promontories, sounds, lochs and small islands are often difficult to differentiate from each other. To many people, the coast creates a sense of security that cannot be found within the vast scale of the inland mountains and moorland, by providing shelter and allowing radiating views out to sea.

The influence of the Wester Ross coastline extends inland, characterised by exposure, open visibility, atmospheric conditions, light and the movement of water. The relative dominance of each element varies in different weather. On a day when conditions are calm the landscape may be perceived as relaxing, tranquil and safe. Yet, in contrast, stormy weather can be unsettling and exhilarating.

As the coastline elevates, views open out to vast expanses of sea and wide skies. The relationship with the sea is lost, creating an unsettling and exposed detachment. Along the indented coastline of Wester Ross there are only a few sand and shingle beaches. This means that where they do occur, their contrasting pink colour, crescent shapes and detailed textures create a strong focal point against the dark backdrop of moorland hills.

Within the convoluted landscapes in the north of Wester Ross distant views are obscured by the constant rise and fall of the land. Foreground detail compensates for the lack of a strong, dominant focus in this repetitive landscape.

The moorland landscapes are perceived by some as bleak and monotonous, visually dominated by the surrounding dramatic mountains and upland areas. Yet the extensive, undulating moorlands have a strong and simple composition, which creates a visual unity not found in the uplands. Predominant characteristics are the subtle variations in texture, isolated rock outcrops and lochans, seasonal changes in the colours of grass and heather, and the occasional areas of eroded peat bog.

The inner firths extend far into the landmass, producing extensive tidal mudflats along which extensive views can be enjoyed, many terminating in spectacular panoramas of the central hills. The presence of these firths and their bridge and causeway crossings increases awareness of the sea, as once small ferry links would have done. In other places the topography forces the main communication routes down to the shore where the experience of the sea/land interface and its variety and dynamism is so powerful. Here the tide, wind and changing light quality add an exciting facet to the landscape experience. The ability to see directly across the firth to the opposite shore gives a feeling of location allowing individuals to establish their own geographical reference points in the landscape.

Humans' relationship with the sea and the coastal lands is an important element in the landscape. The hierarchy of coastal indentations, along with their associated settlement and microclimates, result in a series of smaller scale landscapes often very different from the intervening coastal stretches. In areas where the coast is more uniform, coastal communities occupy tightly knit villages and small towns built and organised to withstand the severity of the climate. Small fishing settlements contrast with the now-familiar sight of oil-related operations such as the rigs and pipeline construction facilities on the Cromarty Firth. These reflect a changing but continuing association between the coastal population and the sea.

The Gaelic Language