Landscape Character Assessment: Outer Hebrides - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The pdf version of this document can be downloaded from the foot of this webpage.

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten.

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of:

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in the “NatureScot Review 92 – Western Isles landscape character assessment”, 1998, John Richards.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

‘It could be argued that there is as much seascape as landscape in the Outer Hebrides. The human association with the coastline is almost total with respect to settlement, and the coast is probably much more important than the inland area for tourism. The form of the landscape is determined by a combination of geology, glaciation, climate, wildlife and human influence.’

(Angus, Stewart, 1997. The Outer Hebrides. The shaping of the islands.)

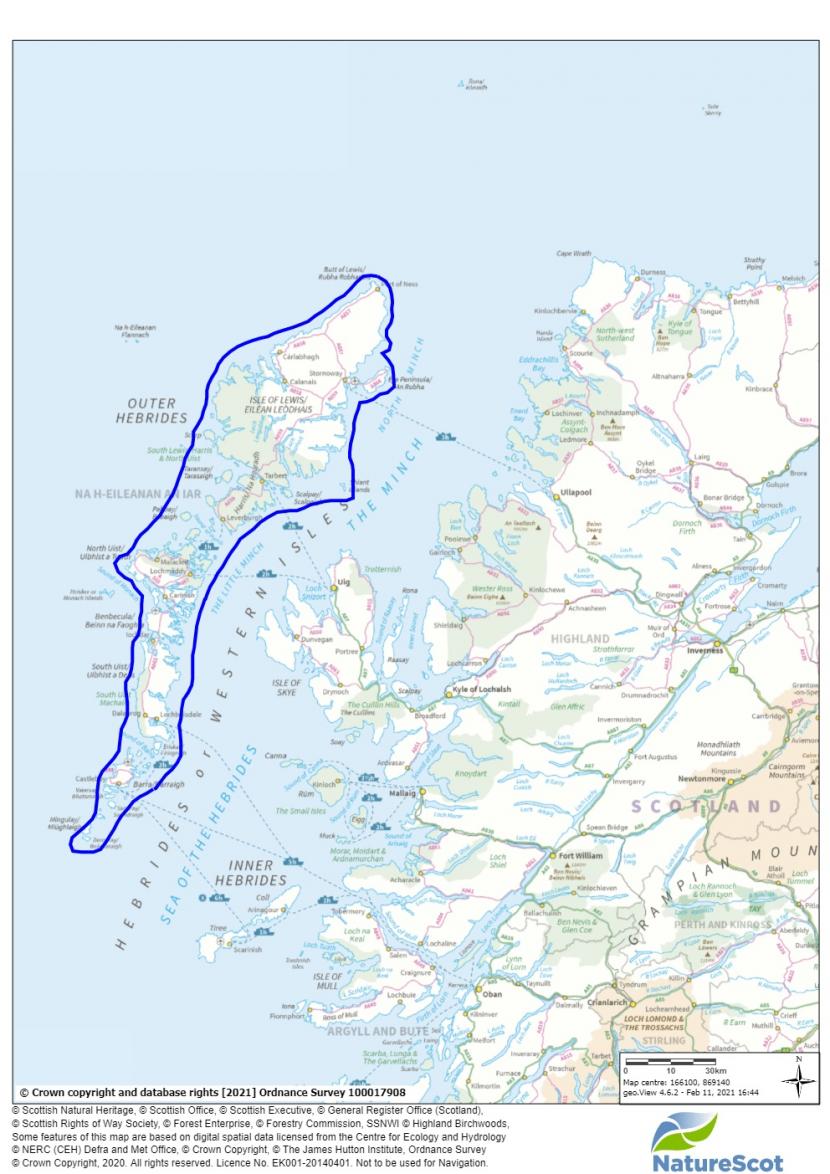

The Outer Hebrides, also referred to as the ‘Western Isles’ or ‘Na h-Eileann an Iar’ in Gaelic, form a 210km chain of islands, lying approximately 45km off the north-west coast of Scotland. There are 119 islands, of which over 70 are named and 14 are currently inhabited. Although there is no firm evidence for this derivation, the word ‘Hebrides’ originated from the Norse word ‘Havbredey’, meaning ‘isles on the edge of the sea'. By around 870AD, the islands were under Norse control and became known as ‘Innse Gall’, or ‘Isle of the Foreigners’ to the rest of the Celtic world until their accession to Scotland in 1266.

The islands cover an area of approximately 300,000 hectares and have an intricate coastline over 3000km in length which makes up one-sixth of Scotland’s coastline. In terms of the range of habitats found there it is extraordinarily varied and highly scenic. Settlement is heavily associated with the coast than the inland areas. The variety and range of light, weather, skies and seas – with the Atlantic to the west and the Minch to the east – create conditions that have long drawn and inspired artists and writers. Above all, it is a vibrant part of the Gaidhealtachd, with a different cultural context to the rest of the country.

Current population estimates for the Outer Hebrides are 26,720 and the average age in the islands is estimated to be 49.5 years. The population has a higher percentage of individuals in the older age groups and correspondingly less in younger age groups. The average age of residents in the Outer Hebrides (2019 population estimates) was over seven years older (49.5 years) than in Scotland (42 years).

The prevailing pattern is a dispersed population living in a predominately rural landscape. Stornoway is the only large town. Almost 26% of the total population, approximately 7,000 people, live within the Stornoway area with the remaining population scattered over 280 settlements.

Crofting is the predominant form of land use and is the foundation of the way of life and the culture. There are some 6,000 crofts; it is estimated that approximately two-thirds of the land in the Outer Hebrides is held in crofting tenure and therefore subject to crofting legislation. Most crofters have another occupation, often related to agritourism.

There are many environmental benefits associated with this system of land tenure. Crofting practices have traditionally helped to maintain the abundant biodiversity which exists in the Outer Hebrides. The traditional extensive methods of farming on which crofting is based persist. Crofting is still a very low input system, with little chemical use. Seaweed and dung, traditional and readily available fertilisers, remain in widespread use, especially in the Uists and Barra. The main crofting product is raising store lambs that are then fattened for slaughter elsewhere in the UK, or Europe. Calf-rearing for store or hardy-breeding stock is carried out mainly in the Uists and Barra, although the activity is less than in former years. Grazing land can be valuable for renewable energy projects.

Life in the Outer Hebrides relates directly to the physical environment and geography of the Islands, the crofting system, and to the Gaelic language. Gaelic lies at the root of the strong cultural identity of the islands, and there is a distinct world view of community and people’s relationship to land and their surrounding environment. The proportion of people in the Outer Hebrides with some Gaelic language skills is the highest in Scotland. Since summer 2020 pupils are enrolled in Gaelic medium education unless their parents request otherwise. This is a first in Scottish education.

The Outer Hebrides are of outstanding conservation importance as evidenced by the large number and extent of international and national statutory conservation sites. The conservation value of the islands has been enhanced by a history of sympathetic human management which has not only protected but enhanced many of the critical habitats.

The coastal dune grasslands that border the islands’ lengthy, white, sparkling sandy beaches along the western seaboard are known as the ‘machair’. This is a rare habitat, restricted globally to north and west Scotland and western Ireland. It ‘may justifiably be regarded as a cultural feature just as much as a biological one’ (Angus, Stewart 2001. The Outer Hebrides: Moor and Machair) and supports a rich and varied world of flowers and grasses, breeding birds and invertebrates. The machair system is the result of environmental processes and human activity, the active crofting of the pastures for cattle rearing and feeding, on this oceanic, dynamic environment.

There is great scenic variety across the Outer Hebrides, with each island having a distinct character:

- North Lewis embodies a great plateau of low-lying peatland extending southwards to bold, rugged hills in South Lewis and North Harris;

- The Harris ‘mountains’ are really hills (An Cliseam – The Clisham at 799 metres is the only Corbett in the Outer Hebrides) but nonetheless they are dramatic due to the way in which they rise up so steeply from sea-level;

- South Harris is an island of stark contrasts: the west coast comprises extensive machair and dune systems, and expansive silver beaches, while the east coast is deeply dissected with cnoc and lochan topography, extensive rockscapes and challenging terrain;

- North Uist has extensive areas of low-lying machair as well as an intricate, indented and fragmented coastline of inlets, narrow channels, fjards, lochs and lochans, where the distinction between land, sea and freshwater is often lost.

- South Uist has major contrasts between its ridge of high hills and rocky east coast, where some remote areas are difficult to access, and its widespread extent of machair landscape, dunes and magnificent beaches on the west coast;

- Berneray is a small island, tightly and compactly reflecting features found across the Uists;

- Barra and Vatersay are rocky and fringed with smaller islands; Barra is compact with Heaval (384 metres) standing centrally, and its main settlement at Castlebay clustered around a broad bay that provides safe anchorage, with Kisimul Castle fortified on a central islet – a striking centerpiece; the Traigh Mhor the ‘Cockle Strand’ serves as the island airstrip and the small airport is sited on the machair land above the beach.

This diversity of land and sea, culture and habitats is extensive even across smaller isles not mentioned above - each offshore island or island group had its own character and atmosphere, some are still occupied, others abandoned. The islands comprising St Kilda are world famous for their cultural and natural associations, and it is a dual World Heritage Site on account of its historic and nature conservation status. The Shiants are renowned for their dramatic cliffs and sea bird colonies.

Island landscapes and seascapes have long inspired the visual and written arts – Gaelic song and bardachd (poetry). While the islands’ landscape and cultural heritage is a prime component of tourism and a source of creative content, it is the oral tradition which transmits much of Gaelic culture and has kept Gaelic history, values, music, and a distinct sense of identity and kinship alive. Traditional and contemporary music thrives along with literature, arts and crafts; broadcasting, textiles and other creative and cultural industries tend to be rooted in the islands’ ‘sense of place’, with the gross added value of these industries to the Outer Hebrides economy being in the region of more than £33 million.

The Outer Hebrides are the home of Harris Tweed, the only fabric in the world governed by its own Act of Parliament and the only fabric produced in commercial quantities by truly traditional methods. It is an internationally known and acclaimed cloth that can be produced only by weavers working at their own homes.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Geology

Underlying geology

The island chain, from Lewis in the north to Berneray in the south, is made up of Lewisian gneiss. These complex crystalline rocks are amongst the oldest in the world. Minor differences in the mineral constituents of the gneiss mean that various bands and inclusions exhibit differing resistance to erosion. This creates one of the characteristic features of the Lewisian landscape: its diversity of hard rock landforms. One of the greatest contrasts is the difference between the relatively subdued topography of the North Lewis plateau, and the bold, rugged hills of South Lewis and Harris, which rise abruptly out of the expanse of blanket bog.

Whereas on mainland Scotland Lewisian rocks are overlain by younger rocks to a depth of up to 16km, in the Outer Hebrides they are overlain only by intrusions and the sediments of the Shiant Islands and Stornoway Formation. Most of the Lewisian gneisses in the Outer Hebrides were strongly altered by what is known as the Laxfordian event (some 1,700 million years ago) when rocks were metamorphosed. Magma was intruded into the gneisses forming veins and sheets of hard, pink granite, harder than the surrounding gneiss. The resulting dykes and sills (Scourie dykes) can be seen in many places, as at Leanish Point on Barra. Some of these igneous intrusions were unaltered by Laxfordian metamorphism and these ‘Cleitichean beag’ gneiss outcrops – the Pentland Road Knolls – are found especially in north Lewis. Anorthosite is an igneous rock, rare in Britain, consisting predominantly of feldspar, which forms the summit of Roineabhal and outcrops around Lingerabay. The South Harris anorthosite, an area of 7-8km2, is the largest expanse occurring in the U.K.

The Outer Hebrides Fault was caused by a major fracture in the Earth’s crust, probably starting during the Laxfordian, and the fault has continued to move through geological time. The rocks that arise along the fault line result from underground Lewisian gneisses ground together along the fracture, melting and extruding into cracks in the gneiss. This has caused rocks to weld together; these are resistant to erosion and now form a chain of low hills along the Outer Hebrides Fault, from Eaval in North Uist, to Heaval in Barra.

Glaciation

The Outer Hebrides were originally one long island, made up of fault-bound Lewisian gneiss, which stood above sea level for a billion years. Most evidence of glaciation dates from the most recent Ice Age, when the Outer Hebrides were crossed by the mainland ice sheets. These scoured the gneisses into bare, rocky knolls and areas of angular, frost-blasted rock. The last major glaciation of the Outer Hebrides was by a local ice cap that radiated outwards from centres at Uig and Harris. Only the tops of the highest hills on Harris and South Uist stood out above this local ice at the last glacial maximum and the only islands unaffected by glacial ice sheets were Rockall and St Kilda.

Across the Outer Hebrides glacial action exaggerated the complicated fault mosaics of the gneisses, forming glacially deepened valleys and concave corries amongst the South Lewis and Harris hills, and deep fjords. It also created cnoc-and-lochan landscapes – ice moulded rocky hillocks side-by-side with lochans (water-filled hollows). This distinctive landscape is particularly well developed in south-central Lewis, South Harris and parts of Barra.

Post-glacial geology

Some 11,500 years ago, the dry Arctic climate changed to become relatively, warm and wet, dominated by the Gulf Stream. This caused major environmental change in three distinct ways.

The first of these was the formation of peat bogs in ice-scoured basins and poorly drained low-lying plateaux. Although the acid blanket bogs have limited agricultural value, they provided an abundant fuel supply in a region lacking both coal and timber. Archaeological evidence suggests that the practice of farming led to the clearance of woodland and the spread of grasslands for grazing, destroying forever the natural, postglacial environment of Scotland. In the Outer Hebrides, a great deal of the woodland cover was lost, particularly in the coastal areas and on the better soils. Peat continued to form as the climate became colder and wetter.

The second was the machair, formed from the gradual, lengthy accumulation of calcareous sands along the western coastal edge. The machair’s sand content derives largely from glacial drifts which formed a shallow offshore platform immediately after glaciation, while the calcareous component of the sand originates from the crushed shells of numerous marine organisms. The vegetation that developed is typical of calcareous to neutral sandy grassland.

The machair is formed by the movement and accumulation of sand by prevailing, strong westerly winds and rain that gives rise to a complex, highly dynamic system of erosion and deposition at the coastal edge. The grassland has been modified by human activity throughout its development. Traditionally, machair supports extensive grazing regimes and cultivation that rely on low-intensity systems of rotational cropping. This traditional agriculture sustains a rich and varied dune and arable weed flora. Today, the machair plains form a rich and verdant landscape throughout the summer months and, under traditional rotational cultivation, form the Outer Hebrides most productive agricultural land.

The third major effect is the gradual rise in sea level, as the last glaciers melted. Sea level did not rise uniformly, but fluctuated. The single, elongated island was separated into scores of individual islands and skerries, particularly along the east coast, where a deeply indented coastline of deep, flooded, glacial valleys was created.

Topography

The coastline of the Outer Hebrides is between 1813 to 3900 kilometres in length, depending on how its intricate extent is measured. The coast is highly dynamic and complex, with many varied forms:

- deeply indented fjords which are deep, narrow, lengthened and steep basins gouged out by glaciation that becomes more shallow towards the sea, to rise to a sill – a ridge of solid bedrock, which may sometimes lie close to the surface (examples are Lochs Claidh, Seaforth, Tamanavay);

- fjards which are drowned glacial lowlands, typically punctuated by small islands, called skerries, that result from isostatic recovery. One of the best European examples is Loch Maddy where the tidal range is 4 metres and the various lochs and lochans vary in their salinity;

- caves, and the geos (or sloc, long narrow, steep-sided clefts formed by erosion in coastal cliffs), stacks and gloups (blow holes, where a chimney has developed behind the cliff face) that can develop from them. The most impressive range of stacks are at St Kilda;

- saltmarsh – intertidal lands at the head of sea lochs and bays, which although generally linear and flat, are complex features in terms of their tidal and estuarine water levels, drainage and vegetation. The largest site is a Melbost-Tong (1 square kilometre), elsewhere large areas lie at Baleshare, Seilebost, Camas Uig and Northton

- softer’ features like tombolos (bars of sand or shingle joining islands to the mainland), dunes and dune-fields.

The interior of Lewis comprises an extensive plain of low-lying peatlands stretching from South Galson in Ness to the loch-sprinkled moorlands south of Achmore in North Lochs. The Barvas Moor makes up a large part of this area, with Muirneag (248 metres) the most elevated point in North Lewis rising above the flat moorland plain. Much of this extensive area covering approximately 300 square kilometres is known as the Lewis Peatlands and has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC). In the past the peatlands have provided a source of fuel since as early as the Bronze Age. These areas were also traditionally used for summer grazing ‘shieling’ and for fishing in the many freshwater lochs and burns. North Uist too comprises an extensive landscape of peatlands and complex waterbodies. It is the underlying topography that largely determines the type of peatland – the confined mires, partly confined mires, and unconfined mires that occur determine the nutrients available for blanket bog growth. There are also strange peat mounds, some two metres high and 5-10 metres across which dot the bog. Many examples of this occur along the Stornoway – Barvas road.

Elsewhere, the land is rocky and rugged. This varies from the high Harris Hills (An Cliseam - The Clisham 799 metres) which consist of curved, boulder-strewn ridges, corries and glaciated valleys, and lower hills in North Uist (Eabhal - Eaval, 347metres). These hills appear prominent due to their setting as they tower dramatically when viewed from the low-lying gneiss platform, which is only 10-20 metres above sea level. Sea cliffs and rocky coasts, and inland a topographically complex pattern of rocky hills and valleys, and the ‘knobbliness of the hard-rock landforms’ cover much of the islands. Harris possesses the ultimate ‘rockscapes’, often described as a lunar landscape, where only about 1% of the land is cultivated and 96% is peaty moorland or ice-scoured rock. Pairc in Lewis and Harris is noted for its trackless and uninhabited areas. The east coast of South Harris (commonly called ‘The Bays’ of Harris) is an undulating and elevated rocky coast of ‘cnoc and lochan’ deeply indented by the sea. The Bays are linked by a scenic single-track road, known as the ‘Golden Road’ as it was so expensive to build in the 19th Century.

Hydrology

Catchment areas vary and include the vast peat moorlands on Lewis with numerous inlets and inland waters; the rugged Harris hills with many hill lochs, boulder-strewn burns and rivers; North Uist’s freshwaters, sea-pools and inlets; South Uist’s machair lochs on the west and fjordic inlets fed by spate rivers on the east; and the brown trout waters of Barra. There are over 4,000 lochs and lochans in the islands in addition to rivers and burns. Lochs range in size from relatively small ones to the seven-mile long Loch Langavat in Harris with its 28 miles of shoreline. Angling in the Outer Hebrides generates some £5.6 million annually for the local economy and accounted for over 260 jobs in the year 2000.

There is an extremely high ratio of freshwater to landmass in the Outer Hebrides. In the wetter post-glacial climate, it is likely that early human activity in felling the islands’ woodlands caused an increase in surplus water. The lack of tree cover means that rainfall increases surface run-off and a rise in the water table. The peatlands hold a high reservoir of water, as well as intricate pool systems.

On Lewis the main river systems are the Grimersta system, the Creed, Blackwater, Fhorsta, Laxay, Blackwater and Gress. The Gress lies 8 miles north-east of Stornoway, and flows for seven miles from its source in Loch Ghrias to Gress sands estuary. Once renowned as a salmon and sea trout river, the runs of fish declined dramatically in the 1970s. The River Creed is a renowned salmon and sea trout fishery that enters the Minch just to the southwest of Stornoway.

Soils

Lewisian rocks that make up the majority of the Outer Hebrides are largely resistant to weathering. The soils derived from them are acid and nutrient-deficient. Rivers carry little silt because there is scant erosion of the underlying, hard rocks.

More fertile soils occur on the sedimentary rocks of the Stornoway Formation and the Ness tills, which are made up of glacially deposited materials (moraines and gravels). The soil pattern can be very complex – notably in parts of Harris, Benbecula, North and South Uist.

Many soils are ‘leached’ of their nutrients by exposure to high rainfall, low evaporation and the abundance of water. There are areas of brown earths, developed on the richer materials in the crofting townships of Breasclete, Bragar, Leurbost, Rodel and Carloway.

The only extensive area of brown forest soil is in the Lews Castle Grounds. It was largely imported from the mainland as part of Sir James Matheson’s ‘improvements’ in the mid 19th Century. In many localities soils have been improved by humans: millenia of manuring and fertilizing have improved the agricultural capacity of in-bye, but also areas of the uplands. A notable instance is the construction of feannagan, or’ lazybeds’ – linear, agricultural terraces built up through a combination of turf, seaweed and manure to provide raised agricultural soils within waterlogged and poorly drained areas. They were used for growing mainly potatoes and oats. These have left linear, grooved patterns in the landscape, distinctive in low-light during the winter and evening, covering large tracts of land mostly across the western coasts of the islands.

In more recent times inland areas of acidic peatland were improved by top-dressing with the alkaline, calcareous shell sand from the beaches and machair in line with recommendations made by the North of Scotland College of Agriculture in the 1970s.

In general, the machair system is a dynamic one with natural changes of sand erosion and deposition. A great deal of research and work has led to better understanding of the complex systems, and the effect of intentional and unintentional human actions on machair.

Climate

The Outer Hebrides climate is oceanic – all the islands are classified as ‘hyperoceanic’, meaning that the sea is the moderating influence on the climate, which rarely exhibits temperature extremes. Winters are less cold than would be expected at this latitude due to the relatively warm waters: there is an average winter high of 7°C (44°F). However, summers are rarely very warm, with an average summer high of around 16°C (60°F). There are long daylight hours in the summer months, with barely two hours darkness in midsummer because of the northerly latitude. The sunniest months are April to June; December is the wettest month.

Wind and rain are dominant features and combine to form the major limiting factors on humans and the environment – major damage is not infrequent. Most older houses are located and aligned to maximize shelter, thereby ‘creating a settlement pattern that seemed to sit very comfortably in the natural landscape’ (Angus). The prevailing wind is from the south and south-west, with most gales occurring in winter. The majority of the land area is classified as ‘very exposed’ with average wind speeds of 12-15.5 knots. There are substantial differences between the different island groups. The lower lying Uists are often more vulnerable to gales compared to more sheltered settlements in Harris. On Lewis, settlement on the higher coastal plateau tends to be more exposed than those more sheltered ones on the east coast.

Land cover

The relationship between human activities, flora and fauna are complex. The traditional way of life and farming methods are non-intensive and overall, human impacts have been light, compared to the mainland. Many of the island habitats are fragile and easily damaged; the ability of damaged vegetation to recover is extremely slow due to the harsh climate and physical conditions.

The major influences on plant life are exposure to strong, often salt-laden winds, the high rainfall, and poor drainage qualities of the underlying gneiss substrate. Vegetation in the Outer Hebrides falls into two broad types:

- the mires, heaths and acidic grasslands of the peat-covered inland and upland areas; and

- the contrasting distinctive grass communities of the machair plains.

Within these broad types there exists a wide variety of habitats such as dune systems, machair, grasslands, maritime grasslands, salt marshes, mountains, heathland and wetlands.

Peatland

Peatland in the Outer Hebrides covers some 70% of the land area. It is the most common habitat in the Outer Hebrides, and forms the characteristically smooth blanket bogs, studded with numerous water bodies, which are extensive across much of Lewis and North Uist, with more localised areas spread throughout the islands. Shallow blankets of peatland vegetation overlie the rocky moorlands where there are deeper peat deposits and small lochans. On Barvas Moor the average peat depth is 2.1 metres and the maximum depth recorded is 5.1 metres. Although pockets of peat started accumulating in the Neolithic it is largely the product of human vegetartion clearance coupled with climatic deterioration in the Iron Age. Humans have managed the peat in various ways, most notably for fuel.These nutrient poor peatlands are host to a relatively limited variety of plants and animals, but some are highly adapted to this environment, including many species of heather, mosses, liverwort, rushes and sedges.

At higher altitudes, the peatlands give way to montane areas which support a limited range of plant and animal species due to the extremely rugged rocky terrain and high winds. Conditions for soil formation are generally poor on the summits and ridges. Vegetation tends to be sparse, and the nutrient-poor soils are confined to cracks and patches between rocks, so plants are largely confined to lichens, mosses and thin grasses. Montane species occur throughout the uplands, often at low altitudes compared to other areas such as the Cairngorms. This is because of the oceanic conditions – highly exposed with increased rainfall, humidity and cloud cover. Montane species can be found at or near sea level and often flower later than elsewhere.

Machair

Along the west coast of the islands, prevailing westerly winds blow large amounts of shell sand onshore. This forms the flat fertile coastal plain known as machair. The shifting sands are often stabilized or by sub-surface archaeological sites and deposits. A fragile agricultural soil has been maintained here since at least the Bronze Age. The resulting habitat sustains a rare and valued mix of rich bird and plant life. There is a traditional grazing pattern accompanied by low-intensity cropping of the machair that together creates a habitat mosaic ranging from distinctive patterns of cropped and fallow land on the drier machair, to wet meadow on loch edges. Each of these land uses creates conditions which support characteristic communities of plants that in turn create great visual and seasonal diversity across the machair plains.

Woodland

There is a near absence of woodland due to human activities and livestock grazing over many hundreds of years, combined with the severe climate, and in many areas, lack of suitable soils. Tree stumps and pollen grains from peat bogs are ample evidence of post-glacial woodlands of alder, birch, elm, oak, hazel, pine, willow, rowan and juniper, although there was probably never the extensive tree cover that existed on the Scottish mainland.

There is considerable woodland immediately to the west of Stornoway, the result of woodland planting and major landscaping around Lews Castle by Sir James Matheson in the 1840s, following his purchase of the island of Lewis. The mature, mixed broadleaf-coniferous woods provide shelter and open space in close proximity to Stornoway and are well-used for recreation.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

Importance of climate change to the archaeological record

Human settlement in the Outer Hebrides is mainly determined by natural conditions. It is sparse and largely located along either the lower-lying western seaboard, where the most fertile soils are found; or on the east coast concentrated around natural deep-water sheltered harbours and some isolated sandy bays. This pattern has persisted since the Neolithic.

Although human habitation dates back to the end of the last Ice Age (some 12,000 years ago) and the settlement pattern prevails throughout this time across the islands, the sea level was then much lower than it is now: perhaps some 9 metres below its present level. This means that many smaller off-shore islands would have been joined to the mainland (for example in Loch Roag); previously inhabited terrain on the west coast now lies submerged; and sandy beaches would have lain further westwards.

Much archaeological evidence comes from the dynamic coastal zone. Finds from the now-submerged lands and eroding coastline include: an oval-shaped, woven basket, dating to the early Bronze Age or Iron Age, and still containing quartz stones and animal bones, which was found at Baleshare, on the south-west coast of North Uist in 2014; copper coins, thought to date from the mid-4th Century AD, were found in a sand dune in the Uists where past finds included a Roman brooch and pottery shards; tidal erosion on Cnip beach, Uig, Lewis, uncovered an exceptionally well-preserved Iron Age settlement complex; and of course, in 1831, Malcolm MacLeod of Pennydonald discovered a small stone chamber at the edge of Uig beach on Lewis. Inside, was a hoard that contained 93 gaming pieces made from walrus ivory and whale tooth. The pieces, probably made in Trondheim, Norway in the 12th – early 13th Century during the 450 years of Norse rule of Scotland, are known to us today as the renowned ‘Lewis Chessmen’. The pieces were sold for £30 and 84 were eventually bought by the British Museum, 11 were acquired by the National Museum of Scotland in 1888. Six pieces are now on loan to Museum nan Eilean from the British Museum. Many preserved artefacts have also been found in peat – a rare Hebridean stone axe with its wooden haft substantially intact was discovered in 1982 during peat cutting at Shulishader in Point, Lewis. The haft was radiocarbon dated to around 3,150 BC.

Historical Landuse

Mesolithic (c. 7000 – 4,500 BCE)

Pollen grains from peat samples indicate areas of mixed deciduous woodland existed following the end of the last Ice Age. One of the first pieces of evidence of human presence in the Outer Hebrides is the increase of microscopic charcoal particles and decrease of arboreal pollen in peat and sediment samples. This appears to reflect deliberate burning of woodland, presumably to increase grassland for grazing animals or to increase the occurrence of marginal woodland ecologies where edible plants such as hazel or berries would flourish.

Although much of the Mesolithic coastline is now submerged, and most evidence for hunter-gatherer occupation and activity is now lost, small isolated pockets of Mesolithic activity have been discovered, such as at Traigh na Beirigh and Aird Chalanais, in Lewis, Barpa Langais, in North Uist and Oransay, South Uist. The best evidence for Mesolithic settlement was found at Northton, in Harris, where charred hazelnut shells, in association with hearths, pits, and artefacts, were dated to 7000 BC. This ephemeral evidence suggests a mobile, hunting and gathering population, as in the rest of Scotland, who travelled seasonally through the landscape, taking advantage of localized resources. Archaeological evidence for Mesolithic seasonal fishing has also been found at Cnip, in Uig in Lewis. There is further potential for sites to be preserved under the machair or along river tributaries inland.

Neolithic/early Bronze Age (c.4,500 - 1,200BC)

Clearance of woodland continued with the introduction of farming from around 4,500 BC to make way for managed areas of grazing consisting of grassland, sedges and heather. Evidence for burning found in pollen cores shows that these grasslands may have been regularly burnt, perhaps as a way of improving the qualities of the pasture and rejuvenating rank vegetation. Although no coastal settlements have been detected due to sea level rise there is much evidence for the presence of human occupation on the coast from stray finds throughout the Western Isles. This includes stone axes; flaked lithics of flint, mudstone, and quartz; ground stone tools such as hammer stones and pottery; and flaked stone tools such as arrowheads, scrapers and knives., Tools were made from the local white quartz outcrops which form veins in the Lewisian gneiss, as well as mudstones from the Shint Islands, and imported flint from the mainland. At Cnoc Dubh on the southern shores of Loch Ceann Hulabhig, near the Neolithic Callanish complex, a vein of quartz worked in prehistoric time can still be seen (Bjarke Ballin, Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports 11, 2004).

A tentative picture of settlement is emerging through archaeological excavation. Neolithic settlements were relatively transient, and it is possible that there was still some population mobility. Settlements have been discovered on artificial islands in lochs, for example at Loch Olabhat in North Uist, and elsewhere. The earlier settlement at Northton continued in use during this period. Neolithic houses were small, oval structures, relatively lightly built, which used wood, turf and stone in their construction. Neolithic pottery has been found associated with many Iron Age roundhouse sites located on islets, suggesting that such sites may have been the focus for settlement in the Neolithic.

Large burial cairns such as Barpa Langais in North Uist survive, often located on slopes overlooking routeways or agricultural land. Significant effort went into their construction. In the later Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, many stone circles, alignments and standing stones were erected, including sites such as Pobuill Fhinn, in North Uist, and Clach an Truiseil in Lewis. The distribution of burial cairns and stone settings suggests that settlement was widely distributed across the landscape at this period, including interior areas of the islands which are now covered with blanket peat. Many of these ritual monuments have been respected by succeeding generations and today form a focus of tourist activity.

The best known stone circle is at Calanais (Callanish), where the standing stones erected 5,000 years ago predate England’s famous Stonehenge monument. The stone circle is part of a wider complex of at least ten stone circles, five small stone settings, seven stone rows, nine single standing stones and many burial cairns, distributed around the shores of Loch Rog, on the west coast of Lewis. The Calanais Stones are set in a cross-shaped plan, the result of alterations and additions to the setting over many years, and a chambered burial cairn was constructed in the centre of the circle. Much later, in the Iron Age, a building was built next to the cairn, including some of the standing stones in its walls, showing that the standing stones continued to be an important feature of the landscape for thousands of years.

There are numerous other stone circles throughout the islands, which with the cairns form a legacy of the Neolithic and Bronze Age farming communities’ religious practices and express their understanding of their natural environment and how they made sense of their world. Many of these sites are intervisible, forming inter-related groups in different areas of the islands, such as at Shader and Ballantrushal in Lewis, and around Barpa Langass in North Uist.

The deterioration of the northern European climate, some 3,500 years ago, meant that conditions in the Outer Hebrides became colder and wetter. This had a huge effect on the landscape, principally due to the formation and spread of peat across once fertile land. Soils, especially on the upper slopes, became less productive and settlement shifted to the coastal edge.

A technological change to metalworking was associated with the influence of new ideas from Europe, bringing typological changes in the design of pottery and stone tools. This was reflected in a change in burial practice. Whereas Neolithic tombs contained many different human remains, in the Bronze Age ‘cist’ burials contain a single individual. The cist, built into the ground, lined with stone and covered by earth or a cairn of small stones, was sometimes accompanied by bronze artefacts and distinctive pottery vessels. Bronze Age burials near Cnip (Uig, Isle of Lewis) lie alongside what would have been rich farmland in the Bronze Age, but which is now under water. The burials were accompanied by earthenware pots, and one included a bead made of jet imported from northern England.

The earliest settlements from the Bronze Age are dated to between 2500-1700BC and occur as eroding settlement mounds on the machair. Excavated examples can be found at the Udal in North Uist, at Northton on the Isle of Harris, and in Barvas and Dalmore on the Isle of Lewis.

Late Bronze Age/Iron Age (c. 1,200 BC – AD 400)

By the later part of the Bronze Age, the settlement pattern had largely shifted to its present coastal location. Excavation at Cladh Hallan in South Uist showed that houses had become larger and were built of stone, and that there was a clear association between the size of house and prestigious artefacts – big houses were built by powerful people. These houses had central hearths, with household activity arranged in a sunwise direction around the hearth. Burials of humans, animals and objects were found beneath the floors, including two human bodies which had been mummified.

Survey indicates that settlements were built and rebuilt in the same location throughout much of this period. The accumulated remains of generations of buildings are visible rising above the machair plain to this day.

Further archaeological evidence for this period comes from the metal hoards and stray finds which have been discovered, the most celebrated of these is the Adabroc Hoard from Ness, Isle of Lewis. This was discovered at the end of the 19th Century by a local crofter while cutting peat. The hoard consists of a large and varied collection of artefacts ranging from woodworking chisels and gouges, to socketed axes and spearheads. The hoard also contained items such as beads that have a wide provenance across Europe and Scandinavia, revealing a complex system of trade between these islands and the rest of Europe.

The cultural preference for large stone houses reached its peak with the construction of the massive stone roundhouses of the Iron Age. From the fourth Century BC, brochs were constructed throughout the north of Scotland. These circular drystone towers could reach up to 13 metres in height, though many would have been lower than that. Prime examples are Dùn Chàrlabhagh standing in Lewis and the excavated shoreline site at Dùn Mhulan, South Uist. In North Uist, two of the best-preserved brochs – Dùn an Sticir and Dùn Torcuill - are accessible across stone causeways. These defensive dwellings indicate a period of instability, warfare and competition for resources. The massive remains of brochs and duns are still highly visible landmarks today, particularly for sailors and walkers.

Coastal duns and promontory sites dating to the middle Iron Age are often distinctive in that they may have only one stretch of walling defending a cliff-bound promontory, sometimes with a roundhouse built on the promontory, such as at Dun Mara in Ness, Isle of Lewis, Stac a Chasteil, Isle of Lewis, Caisteal Odair, North Uist or Dunan Ruadh, Pabbay.

The evidence from the Iron Age throughout the Western Isles demonstrates a developed and complex history: there are many different types of site ranging from large and complex Atlantic roundhouses, defended promontory forts, smaller defended roundhouses on islets in inland lochs, and anomalous, possibly religious or mortuary sites which are hard to define, with the reuse of earlier Neolithic monuments (such as at Steinacleit in Shader, and Dunasbroc, Ness, both on the Isle of Lewis). This patchwork of archaeological remains allows us to visualise settlement and small-scale farming lifestyles which were flexible and changing over a long period, dictated by the needs of the society and influenced not only by the landscape but the wider cultural and political environment.

During this period ‘wheelhouses’ developed. These were round houses with a central hearth and internal radial partitions dividing the space into different rooms, which looked, in plan view, like a wheel with spokes. The roofs were partly of stone, minimising the use of wood. Wheelhouses were a common form of housing and their remains are widespread and still visible in the islands, for example at Griomsaigh, Cleitreabhal and Cnoc a’ Comhdhalach in North Uist. In Lewis, wheelhouses which survived to roof level have been archaeologically excavated at Cnip, and others are known nearby in Clibhe and on Traigh na Beirgh.

Later Iron Age/Pictish (up to 800 AD)

The foundation of the monastery of Iona by St Columba in AD 563 enabled Christian conversion to expand into western Scotland during the later 6th and 7th Centuries AD. Evidence of the early arrival of Christianity survives in the form of early medieval sculpture. These occur in their densest concentrations in the southern islands, as most in the northern islands were removed following the Reformation. One of the best examples, that includes a symbol stone, is found on the island of Pabbay, south of Barra. The stone bears a simple Latin cross above two Pictish symbols (a lily and a V-rod). Most are simple crosses like those found in the graveyard at Cille Bhar in Barra or at Howmore in South Uist. The place-name Pabbay, or Papay, which occurs at least eight times in the Outer Hebrides, is derived from the Norse papar-oy, meaning priests’ island, which may indicate the presence of Christian clergy before Viking settlement. Place names with the prefix Kill, (Cille, Gaelic for church) mark the location of early Christian sites, but the number which have Norse dedications suggest that many might date from after the conversion of the Vikings rather than be sites which survived their arrival. The masonry structures associated with these sites are mostly later and are Norse or later medieval chapels and churches built on earlier sites. However, those on some of the off-shore islands such as the Flannans and Ronaigh may be earlier.

Those brochs and wheelhouses that were adapted and lived in throughout the Iron Age often continued to be occupied until around 800 AD. Where they were not abandoned, cellular buildings were added to these earlier structures, such as those identified through excavation at Cnip and Loch na Berie, Isle of Lewis.

Burial practices changed during this period, with long cist cemeteries dating to the 4th Century AD discovered at Galston, Isle of Lewis. A handful of Pictish symbol stones in the southern isles, most notably in Pabbay in the Bishop’ Isles and from a small islet in the sound between Benbecula and North Uist, coupled with the similarity of the square cairn erected at Kilphedar to those found in the Pictish heartland, also indicate a degree of social connectivity between these two areas.

Scandinavian invaders – the Vikings – arrived sometime around 800AD, bringing with them a Norse culture and language that remained strong, despite the increasing adoption of Gaelic and intertwining with affairs throughout Scotland’s western seaboard, until the Isles were formally ceded from the Norse crown to Scotland in 1266. Norse placenames indicate that from the 1000s onwards there was a considerable expansion of settlement and arable farming, into what had previously been pasture land. The abundance of Norse place names is the most obvious legacy of this period of settlement in the landscape. Rectangular Norse period farms only remain visible as settlement mounds on the machair of North and South Uist. At Cnip, they reused a Bronze Age cemetery as a family burial ground, perhaps conscious of the visible remains of the earlier burial cairn. A stone cross at Cille Bharra in Barra has an Old Norse runic inscription on one side and a local-style cross on the other, suggesting that some Scandinavians may have converted by the 10th Century.

Stornoway is an important east coast anchorage, therefore it is likely that there was a Viking settlement in or nearby. The name derives from the Old Norse Stjǫrnarvágr and is thought to mean ‘Star Bay’ or ‘Steering Bay’. Most other anchorages along the east coast also have Norse placenames. Lews Castle Grounds is the site of a Viking Age hoard of ‘hack silver’ – pieces of silver jewellery and coins were found in the 1980s. The hoard is thought to have been deposited around AD 990-1040, and the coins, dated to the late 10th /early 11th Century, were wrapped in a linen cloth and put inside a cow’s horn before being buried, proof of Viking activity in close proximity to Stornoway.

Medieval period (c.1000-1600)

From the 12th Century onwards the islands were increasingly Gaelicised. At first they became part of the Kingdom Sudreyar (the southern isles), also called the Kingdom of the Man and Isles. Lewis and Harris were probably initially more connected to Man, with the southern isles ruled by related families descended from 12th Century warlord, Somhairle. The MacSorleys extended their influence over the whole of the Outer Hebrides and continued to dominate them after the cessation of the Hebrides to Norway. Over the 14th Century their kingdom came to be known as the Lordship of the Isles.

The period of the Lordship of the Isles may justly be regarded as the golden age of medieval Gaelic culture and society; poetry and art flourished, castles and churches were built and masons created intricate sculpture. The Lordship of the Isles’ rule was broken in 1493 by King James IV, who achieved the effective inclusion of the Western Isles within his kingdom of Scotland. In the Isle of Lewis, this led to a significant increase in feuding and raiding, marked in the landscape by the creation of new forts, such as Dun Eistean in Ness and Eilean Bheagram in South Uist, but also by the destruction of earlier monuments, including Stornoway Castle and a reputed grand house owned by the MacLeods of Lewis in Ness.

Castles once dominated the islands’ best harbours. Kisimul in Barra, reconstructed in the 20th Century, is the best-preserved and most iconic. However, the more ruined Borve Castle in Benbecula may contain the remains of the one of the earliest Outer Hebridean castles. The loch it once presided over has now filled in with sand. The island tower house castle in Stornoway Bay was largely destroyed as the harbour expanded.

Under the Lordship masonry parish churches were built throughout the islands, alongside smaller chapels. Some of the best-preserved parish churches, employing a mix of new Gothic and antiquated Romanesque architectural features, can be found at Eaglais na h-Aodhe and Teampull Eion in Lews, Howmore in South Uist and Kilbar in Barra. Teampull na Trionaid in North Uist was not a parish church but remains a highly impressive church building: it was once surrounded by a sanctuary marked by a number of high carved crosses. Most of the crosses from this period were removed alongside the Reformation but several examples of intricately carved late medieval burial slabs, often depicting warriors, ornate foliage, etc., can be found within and around the ruined remains of masonry churches. The most ornate late medieval sculpture can be found in the largely reconstructed St Clement’s Church, Rodel: a reminder of the skills that were established during the Lordship. The Reformation of the church after 1560 led to a lack of church provision and many medieval churches and chapels throughout the island fell into ruin at this time, and were later reused as burial aisles.

A number of prehistoric forts, occupied stacks, and crannogs that were built in the late Iron Age continued to be maintained and occupied into the medieval period. This increased following the forfeiture of the Lordship of the Isles. In some cases prehistoric sites had new masonry structures built on them, such as Dun Raouill in South Uist and Dun MhicLeoid (Castle Sinclair) situated on an islet in Loch Tangusdale, (Barra). Some brochs had medieval buildings inserted into them – the most visible being Dun an Sticer, in North Uist. Many were simply reoccupied by building small houses in and around them. Some new fortifications were also built, such as Eilean Bheagram in South Uist and Dun Eistean in Ness.

The houses and farming patterns of most of the medieval population remains poorly understood. In the Uists, archaeological survey suggests that settlement moved inland from the machair in the 14th Century or a little later (in Lewis and Harris, this shift seems to have happened after the Middle Ages). Prolongued cool and stormy periods caused damage to the soft machair coastlines and illness amongst people and animals, particularly between the 14th and 17th Centuries: this, possibly coupled with political instability, resulted in population decline as well as making machair settlements unviable. It may also be no coincidence that cattle grazing became increasingly important over this period.

Post-Medieval: AD 1600-1900

The period after the Middle Ages was a time of significant change in the Hebrides. Settlement appears to have re-established and expanded: new settlements were created at Gearraidh Bhaltos in South Uist and Gearanan in Lewis. The settlement pattern was of scattered clusters of long rectilinear houses: in Lewis this was focused primarily on the coast, whilst in Uist the settlement sat between the machair and blacklands (agricultural system in the Outer Hebrides). These settlements sat within an infield of rig and furrow, and their inhabitants were largely dependent upon subsistence agriculture, paying rents in material goods such as cattle, sheep, cheese, butter, and eggs. By the end of this period, the first crofts had been established and the islands had reached their peak recorded population, shortly before the First World War.

The changing character of settlement during this time was part of wider changes in Scotland. From the later 17th Century onwards, agricultural production across Scotland started to increase, with surpluses providing for the growing urban populations. By the 18th Century, ideas of agricultural improvement were spreading widely, and landowners started to reorganise their estates with a view to generating more income. In South Uist, construction of a new, grander estate house was started in 1700, and during the following two centuries new farms were laid out and large farmhouses were constructed. From the 18th Century onwards, there was voluntary emigration from the islands, both to Mainland Scotland and elsewhere in the British Empire.

Estate incomes were boosted by kelping in the 18th Century. This was the burning of laminaria seaweed to produce alkali ash which could be used in industry. To support this, some estates created tiny land holdings, crofts, to accommodate people working in kelping. Kelp was burned in long stone-lined trenches or ovens, the remains of which can be seen around the coast of the islands. The kelp was shipped to Leith, Dumbarton, Glasgow, Newcastle, Liverpool and Bristol. During the kelping season, workers might stay in small huts, such as those at Rudh’ Aird Mhule in South Uist. Sometimes uninhabited islands were used. Estates such as South Uist reserved the use of seaweed for kelping, which meant it could not be used to fertilise agricultural land, reducing the productivity of landholdings. The industry collapsed at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, reducing estate incomes and resulting in poverty among former kelpworkers.

The potato was introduced to the islands in the mid-18th Century, and it rapidly became a staple crop, producing more calories per acre than barley or oats and supporting population growth. The mid-19th Century failures of the potato harvest created destitution and starvation. Significant clearance of populations occurred around this time, as estates reorganised once again and involuntary emigration occurred, particularly from South Uist and Barra. The population of North Uist halved between the mid-19th Century and the beginning of the First World War. Settlement patterns shifted significantly, as remaining machair settlements were extensively cleared and the population was moved either onto rocky east coastland, for example in Harris, or crowded into a few larger townships, such as Barabhas in Lewis. Colonel Gordon of Cluny, owner of Barra, South Uist and Benbecula evicted thousands of islanders using trickery and cruelty and even offered to sell Barra to the government as a penal colony. Islands such as Fuaigh Mòr were completely cleared of their populations. The tidemark of lazybeds on the hillsides reveals the extent of land pressure prior to the clearances, as farmers tried to make a living from ground that had previously been thought only fit for grazing.

For those who remained, new economic opportunities emerged through the export of cattle, commercial fishing and tourism. During the summer season in the 1860s and 1870s five thousand inhabitants of Lewis could be found in Wick on the mainland of Scotland, employed on the fishing boats and at the quaysides. Nonetheless, emigration and naval or military service became the choice of many and the archipelago's populations continued to dwindle throughout the late 19th and 20th Centuries. By 2001 the population of North Uist was only 1,271.

The crofting landscape as seen today, with individual houses on small, rectangular holdings forming linear townships, largely had its roots in the mid-19th Century landscape reorganisation, though there are remains of earlier planned settlements at Arnoil and Barabhas in Lewis. The traditional thatched houses of the islands, now increasingly rare, varied in internal organization from island to island: in Barra and Uist, animals were not housed under the same roof as people, while in Lewis they were. Lewis thatched houses therefore tended to be long and large, sometimes with parallel ranges of buildings housing people, animals and stores, while Barra crofts had a cluster of smaller separate buildings. Their construction reflected the materials available in the surrounding landscape: stone, peat and clay; and roofing materials varied depending upon local plant growth, including heather, marram grass, iris leaves and/or straw. The brickworks at the north end of Barra reveal short-lived attempts to develop industry in this period. The escarpments around Vatersay and part of Castlebay in Barra also reveal the extent of a large-scale and industrialised fishing industry.

Despite Clearance, the overall population of the islands continued to rise towards the end of the 19th Century, creating significant land hunger. National awareness of the islands increased with fashionable interest in the Scottish Highlands from the mid-19th Century onwards, and towards the end of the century a Royal Commission, the Napier Commission, was established to investigate the situation of the crofters of northern Scotland. One result of the commission was the Crofters’ Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886, which for the first time gave legal rights and some security to crofters, and encouraged the development of crofts.

20th Century to the Present Day

The work of the Napier Commission and the Congested Districts Board, and the passing of the Crofting Act of 1886, improved poor living conditions for the islanders but social unrest continued due to marginal and overcrowded croftland being unsustainable for families. In July 1906 grazing land on Vatersay was raided by landless men from Barra and its isles. Lady Gordon Cathcart took legal action against the "raiders" but the visiting judge took the view that she had neglected her duties as a landowner and that "long indifference to the necessities of the cottars had gone far to drive them to exasperation". On Lewis, land agitation continued from 1874 through to 1922. A number of protests took place in order to challenge the right of landlords to deny people the right to live on and work the land of their ancestors. Monuments to the Land Heroes ‘Na Gaisgich’ can be seen at Pairc; at Point; at Bernera, in Uig; and at Gress in Lewis.

In 1911 the Small Landholders (Scotland) Act of 1911, taking over from the Board of Congestion, attempted to negotiate better land allocations for crofters. The creation of new crofts and landholdings, especially in Lewis and Harris, was interrupted by the First World War, as the islands’ young men left in their droves to fight overseas.

The loss of men in the Western Isles due to the Great War cannot be underestimated. Every village, township and island was deeply affected, and this is marked today by the many war memorials inscribed with hundreds of names found across many parts of the Outer Hebrides, and the frequent Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones within the islands' cemeteries. Twice as many men from the Isle of Lewis died during World War One in proportion to the UK losses as a whole, and this scale of loss is represented throughout the island chain. The impact of this loss on the landscape of the islands could be felt not only on the crofts – which were maintained by younger family members and the women - but also on the fishing grounds: boats were abandoned and were often never used again, with only the occasional timber prow reused as a fence strainer.

The large loss of men and lack of employment for the returning survivors encouraged the desire to emigrate for many. Despite continuous occupation for thousands of years, many of the more remote islands were abandoned - Mingulay (South of Barra) in 1912, Hirta (St Kilda) evacuated in 1930, and Ceann Iar (part of the Monach Isles) in 1942 among them. This process involved a transition from these places being perceived as relatively self-sufficient agricultural economies to a view becoming held by island residents and outsiders alike that they lacked the essential services of a modern industrial economy.

After the Great War Lord Leverhulme, a famous soap magnate who owned Lewis and Harris for a short time, tried to kick-start the economy and assist the islanders by developing the fishing industry. He provided much-needed jobs after the war and many improvements were made to roads, and housing schemes were built in Stornoway. However, conflict arose over the land issue when returning soldiers and sailors were promised land by the Government. In frustration, Leverhulme abandoned his schemes when his farm at Gress was raided and the government refused to take action against the crofters. His final grand gesture was to gift the parish of Stornoway to the people, facilitating the creation of the Stornoway Trust, Scotland’s oldest community landlord, in 1923.

The advent of World War Two had a more lasting physical impact on the landscape of the Western Isles, with many radar bases, coastal batteries, gun emplacements and other military structures built at the beginning of the conflict. The geographical location of the islands was crucial in the defence of Britain’s coastline, and military installations contributed enormously to the control of Atlantic waters throughout the war. As the Western Isles were not considered threatened by invasion there is a lack of anti-invasion defences on any of the islands. The main threat was considered to be from the air, hence the many radar sites throughout the Western Isles. Remains of these can be found in Ness, Breanais, Aird Uig and Islibhig, Isle of Lewis, Rodel, Isle of Harris, Clettravel in North Uist and Borve Castle in Benbecula, and Grien Head, Barra.

A large coastal battery can be found at Arnish Point on the approach to Stornoway harbour in Lewis, as the Navy was concerned about a seaborne attack on the town, which never transpired. Stornoway also hosted a large airfield from where RAF attacks on German U-boats in the Atlantic were flown. The airport was also used as a stop-over for Allied military aircraft travelling from the US, via Iceland, on their way to the military airfields in the east and south of England. The airfield in Balivanich was also constructed at this time.

There were gradual economic improvements, among the most visible of which was the replacement of the traditional low-lying, thick-walled thatched house or ‘tigh’ which came to be known as the ‘taigh dubh’ or ‘blackhouse with accommodation of a more modern design, many of one and a half, or two storey height in contrast to the low-lying single storey thatched houses. This was encouraged by the provision of housing grants by the Department of Agriculture & Fisheries. The resulting houses, known as ‘White Houses’ in contrast to the traditional ‘black house’, were built to plans produced by the Department. The shift from Blackhouse to White House can be seen at Arnol, Isle of Lewis, and the remains of both can be seen throughout the islands.

Following the Second World War, crofters increasingly took advantage of agricultural grants to fence inbye croft land, changing a largely open agricultural landscape to an enclosed one within two generations. This reflected a move to more individual and less communal management of agriculture, as the population of the islands has progressively decreased and aged.

The creation of the Highlands and Islands Development Board, the discovery of substantial deposits of oil in the North Sea in 1965, the establishment of a unitary local authority for the islands in 1975, and more recently the renewables sector, have all contributed to a degree of economic stability in recent decades. The Arnish yard has had a chequered history but has been a significant employer in both the oil and renewables industries. Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, the local authority, covers the whole of the Outer Hebrides and employs 1,300 people, making it the largest employer in the Outer Hebrides. The council has its main office in Stornoway, Lewis; and area offices in Tarbert, Harris; Balivanich, Benbecula; and Castlebay, Barra. It is often known locally simply as "the Comhairle" or “a' Chomhairle”.

Under the Highlands and Islands Convergence Programme 2007 – 2018 the islands benefitted from funding from the European Union to help achieve an ambitious target for jobs and economic growth. European Structural and Investment Funding has contributed funding for harbours and key infrastructure developments, such as the Scalpay Bridge and the Eriskay Causeway, as well as tourism-related projects such as the Callanish Standing Stones Visitor Centre and countryside access projects. New schools have also been built, including secondary schools in Benbecula and Barra.

Traditional commercial activities centre on crofting, fishing, and weaving including the manufacture of Harris Tweed; and craft food and drink, including new distilleries such as the Isle of Harris Distillery at Tarbert. A number of Community Land Trusts have been set up to take control of the land they live on and to determine their futures with the objective of managing a range of projects to support and develop their area and local economy. In striking contrast to the 19th and 20th Century domination by absentee landlords, more than two thirds of the Outer Hebrides population now lives on community-owned estates which brings new management challenges, along with potential opportunities and benefits. However the economic position of the islands remains relatively precarious. The Outer Hebrides, including Stornoway, are defined by Highlands and Islands Enterprise as an economically "Fragile Area" and they have a substantial trade deficit. Overall, the area is relatively reliant on primary industries and the public sector, and fishing and fish farming in particular are vulnerable to environmental impacts, changing market pressures and legislation. There is some optimism about the possibility of future developments in, for example, renewable energy generation, tourism, food and drink, creative industries and education, and after declines in the 20th Century the population showed an increase in the 2001 Census and the 2011 Census, although it is ageing. At present, the Outer Hebrides has a population of approximately 26,720; Stomoway is the only major town, with about 4,300 inhabitants.

Crofting/Agriculture

In general, many inhabitants of the isles maintain a close working relationship with the land, with the majority of people still living in remote rural areas.

There are over 6,318 individual crofts in 280 townships on the Outer Hebrides and, though the majority are part-time agricultural units, they contribute significantly to the social and economic fabric of the whole community. Crofting is the predominant land use of these islands, accounting for approximately two-thirds of land tenure. It is the foundation of life, language and culture, important for maintaining rural population in areas where it would otherwise have disappeared.

The quality and size of crofts and grazings varies considerably, although they are generally around three hectares in size. Generally, the smallest crofts are found on the poorest land. Uist has most of the full-time crofts on the islands.

Crofting is characterised by traditional extensive farming methods. These still represent a very low-input system, with few added chemicals. The use of seaweed and dung for fertilizer is still widespread in the Uists and Barra. The most important crofting product is the raising of store lambs. These are fattened for slaughter elsewhere in UK and Europe. The rearing of calves as store or hardy breeding stock is also practiced, although cattle numbers have declined since 1900.

Over the past 50 years agriculture, including crofting, has been supported by various agricultural grants and subsidies, funded by National Government and more recently by the European Community. There has been a radical change in emphasis in agricultural funding, away from early schemes which have an emphasis on agricultural improvement and increased agricultural production, to agri-environmental grant schemes which have an emphasis on the use of more environmentally sensitive farming methods.

At present, agricultural subsidies and grants fall into three main groups, Headage Subsidies, Agricultural Improvement Grants, and Agri-Environmental Grants Schemes. Each of these schemes has some effect on the landscape character of the Outer Hebrides. Headage subsidies are based on the number of sheep or cattle maintained on the land. Economically, they tend to favour sheep production and this has led to a decline in hill cattle and a preference for all-sheep systems. This in turn, reduces the need for production of winter fodder on inbye land, and as a result, reduces traditional distinctive land-use patterns and seasonal diversity within the inbye areas.

The most important Agricultural Improvement Grant to the economy of the Western Isles Crofting Areas is the Crofting Agricultural Grants Scheme (CAGS). This scheme provides grants for crofters for capital projects, such as the construction or improvement of agricultural buildings, drainage and fencing which help to sustain their businesses. A croft House Improvement Grant helps crofters upgrade housing or build new homes, covering up to 40% of the cost.

Fishing

90% of fish landings in the Outer Hebrides are shellfish. Deep sea, finfish, and white fish account for the remaining 10%. A significant proportion of the shellfish is exported.

In the early 2000s there was a significant decline in 10-15 metre boats, due to retirements and trading down to smaller vessels with lower running costs. New entrants to the sector are now in boats of less than 10 metres in length. The Outer Hebrides now has the largest fleet of small boats of any fishing district in Scotland.

The number of people employed in the fishing industry has remained stable in recent years, with 318 people employed in fish catching, 300 in ancillary services, including processing, product marketing, gear manufacture and vessel maintenance/repair.

Fish-processing facilities are mostly small-scale. Prawn and shellfish factories operate throughout the Western Isles, and white fish primary processing takes place in Stornoway.

Aquaculture

The Outer Hebrides has an extensive coastline offering a clean high-quality water environment that supports a rich marine natural heritage and provides ideal conditions for growing farmed fish and shellfish.

Fish farming is an established industry and key employment sector in the Outer Hebrides. There are finfish and shellfish farms in both sea‐lochs and coastal waters. The area is the third-largest regional producer of salmon in Scotland and has an extensive number of farm sites. The salmon farming industry has evolved considerably from its establishment as a widespread small-scale business in the 1970s to one led by a relatively small number of operators that farm a lesser number of large sites with automated equipment and who compete in a global marketplace.

There are currently 45 marine sites, which range from conventional salmon farming to organic salmon farming. Fish farming supports 550 full-time equivalent jobs on the islands, 348 of which are in marine salmon farming and 200 in processing, marketing and distribution. Due mainly to lower market prices, many smaller companies have been forced out of salmon farming. Three companies now account for 80% of production.

Weaving

The inhabitants of the Outer Hebrides made cloth by hand for domestic and local use long before the industrial revolution reached Scotland. ‘Clo-Mòr’ (the ‘Big Cloth’), later called ‘Harris Tweed’ has been made for generations by islanders from wool sheared from their own sheep and woven on looms at their homes. Around 1840 the Countess of Dunmore, proprietress of Harris, took an interest and started marketing it to wealthy friends, and it became an established product with merchants across Scotland.

An Act of Parliament in 1993 brought into being the Harris Tweed Authority, replacing the Harris Tweed Association originally set up in 1909. This legislation – alongside the work of the Harris Tweed Authority – allows the safeguarding of the Harris Tweed name, quality and reputation.

Located throughout Harris and Lewis, registered weavers are skilled artisans, their trade often passed down from generation to generation, although certificated training programmes are occasionally also supported by the sector. Harris Tweed® weavers must, by law weave cloth on treadle or rapier looms located at their homes. When travelling around the islands it is common to hear the noise of working looms in action.

Three Island mills, employing approximately a further 130 people manufacture and supply the weavers with the yarn they require for weaving cloth. These businesses trade globally within the fashion, home interiors and accessories markets.

The different coloured threads that blend together in the tweed reflect the natural beauty of the Hebridean landscape. Many products are made locally using Harris Tweed, such as bags, purses, phone cases, clothing and furnishings.

Tourism

The tranquility of the landscape, its stunning sea views and endless skyscapes, its rich history and Gaelic culture, its natural heritage interest and its potential for outdoor leisure activities are some of the main reasons that tourists come to the Outer Hebrides. Tourism on the islands has grown in significance for the regional economy in recent years. It generates £65 million in economic value for the islands, sustains around 1000 jobs, and is one of the key growth sectors in the economy of the islands. There are 219,000 visitors per year; 930 accommodation providers are directly supported by tourism, and hundreds of other businesses depend on the visitor economy. The Outer Hebrides are publicised as a holiday destination through TV programmes, advertisements and features in many national newspapers, supplements and publications.

The Outer Hebrides have some of the most spectacular beaches in Scotland, Europe and possibly the world. A significant number of people come purely to experience these, with the most iconic beaches being Traigh Mhor, Tolstal; Traigh na Berie, Uig, both in Lewis; Northton, Scarista, Horgabost, Seilibost/Luskentyre, on the Isle of Harris; and Vatersay Bay, Isle of Vatersay south of Barra. Beyond their recreational and scenic value, they have an inherent value in marketing the islands as a destination.

Leisure and activity-based tourism (angling, fishing, sailing, canoeing, bird watching, walking, cycling, golfing etc) is also popular. Hosta, North Uist; Scarista, Harris; Mangersta, Cliff and Dalmore on the Atlantic coast; and Eoropie and Port of Ness on the north coast are all popular surfing beaches that attract both locals and visitors. Inshore sailing and scuba diving are popular and can be enjoyed in a host of different environments. There are several popular walking and cycling routes that attract visitors, such as the Hebridean Way, which stretches from Vatersay to Lewis, and the Machair Path (35km on South Uist).

Fresh water and coastal game fishing for salmon, brown trout and sea trout and sea angling (primarily for saithe, pollack and mackerel) provide a popular outdoor recreational activity for many residents. They account for a significant percentage of annual tourist visits per annum.

Genealogy is a growing market. Many visitors come to the islands to find out more about their ancestry, especially from Canada, USA and Australia.

Settlement and Built heritage

As a historic burgh and only town of the Outer Hebrides, Stornoway has a similar sequence of development to many other small Scottish burghs, with a comparable density of population, urban plan form and range of architecture. The medieval core of the town is confined to the narrow promontory of Point Street between the inner (north) and outer (south) harbours, though no buildings from the medieval period survive, nor indeed do any post-medieval buildings from the 17th -18th Century, though remnant parts may exist within later buildings. The Macleod stronghold Stornoway Castle, early 16th to mid 17th Century, occupied a rocky islet beside the southwest tip of the promontory. Its remains, which were still visible in the 19th Century, lie beneath the ferry pier.

The historic townscape of Stornoway is largely mid to late 19th Century, set out in grid-plan north and east of Point Street, expanding the geometrical plan of Georgian Stornoway shown in John Wood’s town plan of 1821. Much of the mid 19th Century expansion is attributable to the ‘improvement’ plans of James Mattheson who purchased Lewis in 1844. He also carried out the considerable redevelopment of the harbour, and built the castellated mansion Lews Castle on elevated land, on the site of the former Seaforth Lodge, across the water from the main town. He also created its extensive wooded parklands and designed estate landscape. This is the grandest mansion and estate of the Outer Hebrides and the most commanding historic feature of the town, forming a picturesque backdrop in views across the harbour. The further eastern expansion of Stornoway in the late 19th to early 20th Centuries, as the herring industry boomed, includes fine examples of Victorian and Edwardian villas (several are listed buildings), notably on Mattheson Road. The townscape of this area is also notable for its ornamental cast ironwork. This is regarded as the best surviving collection of domestic ironwork from mainland Scotland’s world-renowned major foundries of the late 19th century.

Fine civic buildings in Stornoway town centre include the Flemish Gothic style Town Hall and Library (1905) prominently positioned facing the south harbour on South Beach, and Tudor style Court House and Former Jail, (1843) within the grid on Lewis Street. There are some sizeable historic industrial buildings in the harbour area, such as the quayside’s 19th Century former fisher lime harled warehouse Sail Loft, now sensitively converted to residential use. There are also a few prominent 20th and 21st Century buildings, such as the imposing Art Deco commercial building 7 James Street; and striking contemporary An Lanntair Arts Centre (2005), South Beach. The special historic and architectural interest of Stornoway town centre together with Lews Castle and its parklands, is recognized by its designation as a conservation area, and the listing of numerous individual buildings.