Landscape Character Assessment: Orkney - Landscape Evolution and Influences

The PDF version of this document is at the foot of this webpage.

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten.

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of:

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land-use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in the “NatureScot Review 100 – Orkney landscape character assessment, 1998, Land Use Consultants.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

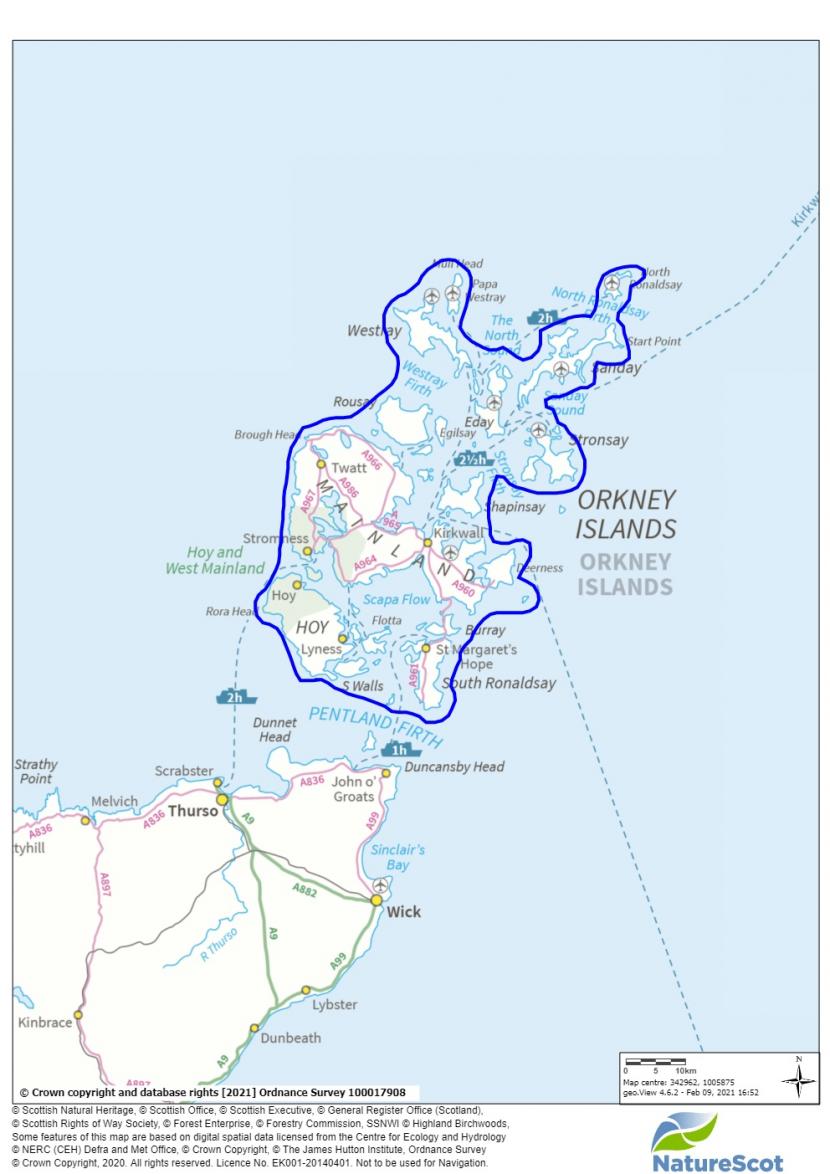

The Orkney Islands are separated from the Scottish mainland by the Pentland Firth. There are approximately 70 islands in the archipelago, 20 of which are permanently inhabited. The islands occupy an area of about 1,000 square kilometres, dispersed over an area that measures 85 kilometres from south to north, and 65 kilometres east to west. The largest Island is Orkney Mainland, which is the 6th largest Scottish island; an older name for the Mainland is Hrossey, Horse Island.

The islands north of the Orkney Mainland are generally referred to as the North Isles. They include Eday, Rousay, Sanday, Shapinsay, Westray, and North Ronaldsay which is further north than the southern coast of Norway. The islands south of Mainland are less commonly referred to as the South Isles, including Hoy, Flotta, Burray and South Ronaldsay. The most southerly island is Stroma. There are approximately 21,670 people living in the archipelago, of which 9,000 live in the largest settlement of Kirkwall.

The islands have predominantly low and gentle relief, the smooth contours of which are emphasised by the scarcity of trees and woodland cover. This landscape, though windswept, supports large areas of productive pastures and some arable farming. The landform is generally lower than 270 metres, except on Hoy, the second largest island, where hills reach 480 metres above sea level. They are characterised by heather moorland cover which contrasts with the pastoral greens of the lower ground. Hoy also shows the most northerly evidence of corries, u-shaped valleys and other glacial erosion in the UK. This produces a stark contrast to the smoother, lower islands.

The sea is important to the physical and cultural landscapes of Orkney. The meeting of land and sea at the coast, and the features that are formed, are key elements in the landscape. The most dramatic topography is found around Orkney's coastline where spectacular cliffs have been sculpted into arches, stacks, geos (coastal clefts) and gloups (blowholes). These renowned features are essential contributors to Orkney's identity and perception. Along the western coast in particular, the land meets the sea in a cliff rampart up to 300 metres high which has been shaped by the relentless action of Atlantic waves. In contrast, many of the lowest areas appear drowned by shallow lochs and bays. Here, the lower-lying coastal features such as tilted flags, sand dunes and sandy bays present an entirely different character.

The climate and topography of the islands have proved amenable to settlement and productive agriculture since prehistoric times. The legacy of past generations is evident in the rich archaeology of the Orkney landscape. Some of these artefacts have remained upstanding and even prominent, while much rich material remains buried. This subtly influences the shape of the landscape, especially through field patterns and hints of building clusters clearly visible from arriving by air. The consistency of visual history in Orkney gives a sense of permanence to the islands enhanced by their pastoral land use. This has been recognised by the “Heart of Neolithic Orkney” UNESCO designated World Heritage Site. There are also the oldest standing house in north-west Europe on Papa Westray; 12th Century churches showing the Norse rule of the islands; the UK’s tallest land-based light house on North Ronaldsay; and evidence of wartime fortifications throughout this time, including Napoleonic and 20th Century conflicts. The location of Orkney has strategic importance to the UK, and its resources are still important in the development of renewable energy.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Topography

Orkney's topography is generally low-lying with smooth relief. The highest areas rise to almost 500 metres above sea level, but the majority of the archipelago is below 100 metres elevation, with significant areas below 30 metres.

The relief of West Orkney Mainland is in the form of a basin tilted up at the north and east. Hill land, generally below 200 metres elevation, forms a gently sloping rim; flat land, with the lochs of Harray and Stenness and the smaller lochs of Boardhouse, Hundland and Swannay, forms the basin floor. The hill land of the West Orkney Mainland is generally smoothly undulating, with locally steep relief associated with the larger hills, for example Wideford Hill, Costa Hill, and the ridges around Settiscarth and Stenness. East Orkney Mainland and South Ronaldsay reach heights of over 80 metres, but lack strong relief. The highest areas are smoothly domed hills, for example, Warthill on East Orkney Mainland and Ward Hill on South Ronaldsay. East Orkney Mainland also has an extensive plateau ridge which constitutes the main high ground. Tankerness and Deerness are both comparatively low, with smooth and undulating topography.

Hoy has higher and more dramatic topography than the rest of Orkney, with heights in the north of the island frequently over 300 or 400 metres above sea level. Ward Hill, which at 481 metres is the highest point in the Orkney archipelago, is located on Hoy. Central and southern Hoy are slightly lower and more undulating than the north, although much land is over 200 metres above sea level. Along the west coast this height is expressed in Hoy's awe-inspiring cliffs which reach over 300 metres high in the north of the island, reducing gradually towards the south. These include the well-known landforms of St John’s Head, the highest perpendicular cliff in the UK at 335m high; and the Old Man of Hoy, a 137m high sea sack.

Although lower, the slopes of Rousay rise steeply from the sea to dramatic effect. This is enhanced by clearly visible terracing on the slopes which creates a distinctive profile from distant vantage points. The extent of Rousay's hill land makes it somewhat distinct from the other North Isles and more closely related to the moorlands of West Orkney Mainland in terms of topography. Eday and Westray contain large areas of land higher than 50 metres above sea level which appear high relative to the surrounding land and sea. The dramatic contrast of height to the sea is a joint product of the geology and the strength of the Atlantic Storm Waves approaching from the west.

In contrast to the above, the islands of Sanday, North Ronaldsay and Stronsay are very low (below 50 metres elevation) with no significant hill forms. In these landscapes sand dune systems and man-made earthworks, for example farm mounds and Treb dykes (pre-Norse land divisions which remain as low broad ridges) are the most significant topographic features.

Solid Geology

The foundation rocks of Orkney are a mixture of granite, gneiss and schists, which formed part of the Caledonian mountain chain 400 million years ago. These rocks originally enclosed the Orcadian Basin which became the focus for the deposition of debris eroded from the higher surrounding regions. This sediment formed the Old Red Sandstone of north and east Scotland, which largely obscured the basement rocks of the Orcadian Basin. There are small areas where the basement complex outcrops in the form of inliers within larger areas of sandstone deposits. The largest such site within the Orkney Islands is to the north and west of Stromness; smaller outcrops are at Yesnaby and on Graemsay. These represent remnants of a north-westerly orientated range of hills, the influence of which is still reflected in the local topography. The dominant basement rock type is a pink foliated granite which has been extensively quarried in the Stromness area for use as building material both in and around the town.

At the time of Old Red Sandstone deposition, around 380 million years ago, Britain lay in equatorial latitudes where the climate was dry and hot. This resulted in the formation of deserts along the fringes of the large freshwater lake known as Lake Orcadie. Climatic changes caused the depth and extent of the lake to alter. Muds and sands were deposited in the lake and, over millions of years, the remains of fish were fossilised in the lake bed. The Sandwick Fish Bed shows the preservation of whole fish due to the anaerobic conditions present in the large stagnant lake, not more than tens of metres deep. Subsequent tectonic activity caused these sediments to become folded and faulted creating ranges of hills. This activity also initiated lava flows from volcanic vents into sills and dykes. The hills created were subject to millions of years of erosion and partial submergence by the sea. The islands of Orkney represent the higher remnants of these hills, left exposed after the submergence of lower land by the rises in sea level.

With the exception of the small outcrops of basement complex the Orkney Islands, therefore, consist almost entirely of gently inclined sedimentary rocks of middle and upper Old Red Sandstone age. The middle Old Red Sandstone falls into two major groups. The lower group comprising Stromness flags and Rousay flags is the dominant type through much of the area, on Orkney Mainland, Rousay, Stronsay, Shapinsay, Westray and Sanday. These rocks comprise sequences of thinly bedded grey and black siltstones and mudstones with alternating thin beds of sandstones. These flags vary in colour from pale to dark browns and greys. The upper group (Eday beds) comprises the lower, middle and upper Eday sandstone, and is generally confined to the North Isles and parts of East Orkney Mainland, although it is also present along the North Scapa and Brims Risa faults.

Beds ascribed to the upper Old Red Sandstone are confined to the Island of Hoy where they form up to 1000 metres depth of red, pink, and yellow sandstone with subordinate bands of marl. They are underlain by a variable thickness of basalt lava and tuff which rest on an irregular bed of middle Old Red Sandstone.

The Old Red Sandstones of Orkney are generally folded in open sinuous lines which contribute to the rounded gentle topography. Tight folds with steep inclined strata are of limited extent. The principal folds have a north/north-westerly trend which is reflected in the alignment of the main loch basins and hill ridges.

The nature of folds and faults of the Old Red Sandstone is best appreciated around the coast, where cliffs and rock platforms expose the details of jointing patterns, inclines and fault line movements. More importantly, these features influence the rate and form of coastal erosion and thereby determine to a great extent the coastal geomorphology. This includes visually distinctive landforms such as Ward Hill and sea stacks like the Old Man of Hoy.

Faulting has been influential in the structural pattern of Orkney and in the disposition of various rock groups. The largest and most important of these are the North Scapa fault, the East Scapa fault, and the Brims Risa fault. Once again, the principal orientation of fault lines is north to northwest; faults adjacent to one another generally exhibit the same direction of down-throw, which is predominantly eastwards. From the differences in bed thickness, it appears that faults were active during, and possibly before, the deposition of the middle Old Red Sandstone Eday beds.

Several small volcanic vents have been recorded, principally on Hoy, South Ronaldsay and East Orkney Mainland. Some of these are closely connected with dykes, suggesting crustal stretching in a north-north-west direction. Some of the vents contain breccia composed entirely of sedimentary rock and these resemble the breccia vents of east Shetland. These are generally difficult to discern in the landscape due to the mantle of till that covers the bedrock.

The rocks of Orkney, in particular the regularly bedded flagstones, have provided a source of first-class building masonry which has been used since prehistoric times. Its natural splitting qualities (into slabs and blocks) has enabled and encouraged the construction of remarkable buildings by early inhabitants of the islands, many of which remain today. This versatile indigenous resource has been used to the present day for walls, roofing slabs, floor flags and stone fences. Its use in such a comprehensive manner helps to create a strong relationship between human activity and the inherent physical structure of the islands.

Glaciation

The solid geology of the Orkney Islands was modified by glacial action during various Quaternary ice ages, the last of which reached its maximum extent around 18,000 years ago. Several studies indicate that ice streamed eastwards from eastern Sutherland and was then deflected north-westwards over Caithness and Orkney by contact with the Scandinavian ice sheet. After the retreat of these ice sheets, local glaciers lingered for some time in the valleys and corries of Hoy and parts of Orkney Mainland, evidence of which can be seen in the form of moraines and other landforms. Over much of the Orkney archipelago the main effects of ice movement were to smooth out the pre-existing topography and to deposit vast quantities of glacial till boulder clay.

Before glaciation, in areas where the rock is in flagstone form, the hillsides were probably terraced by small rocky escarpments with scree at their base. In most areas the passage of ice has filled the terraces with boulder clay and removed projecting rocks, leaving behind only indistinct ledges. However, several distinct topographic features have also been created by glaciation. Hoy displays many classic landforms of glacial erosion and deposition. The only part of Orkney to have supported local glaciers, the north of Hoy has well-developed corries on the east and west slopes of Ward Hill and on the north-west slope of Cuilags. The two glens on either side of Ward Hill, which converge to form the wide valley at Rackwick, have been considerably modified by valley glaciers to produce the distinctive U-shape. On the south of Rousay, and in the higher parts of Westray, ice scouring emphasised terracing in contrast to the smoothing effects elsewhere.

Glacial boulder clays and moraines associated with the most recent stage of Quaternary glaciation almost exclusively account for the drift geology of Orkney Mainland. The boulder clay of Orkney, which is largely confined to the low ground, is exposed in many coastal sections where it ranges in thickness from three to ten metres. It generally consists of red or purple sandy clay with abundant polished and striated boulders. In eastern and many northern exposures the matrix is composed of material largely derived from the marls and sandstones of the Eday beds, and it also contains shell fragments incorporated from marine deposits which the ice crossed offshore. Traced westward across West Orkney Mainland and Westray, the red is gradually replaced by browns, yellow, and greys as the proportion of comminuted (highly fractured) rock derived from the Rousay and Stromness flags increases. The distribution of boulders in the till shows that the principal ice movement was in a north-westerly direction. Most boulders and smaller stones in the till consist of local material. Erratic boulders carried by the ice into the study area are relatively rare. Most igneous and metamorphic erratics can be matched with rocks outcropping in Sutherland, although some are of Scandinavian origin.

Glacial deposition and fluvioglacial activity created many landform features in Orkney. The corries and glaciated valleys of Hoy contain morainic mounds. Hummocky moraines also occur on Hoy on the hillside southeast of Rackwick and in the valley of the Forse Burn. Morainic mounds are found in the valley leading west from Finstown (Orkney Mainland) and in the northern part of Orkney Mainland, near Harray and Evie. These may be the deposits left by lobes of ice which, during a stage in the de-glaciation, re-advanced westward and south-westward from the iced filled bays and straits up the valleys of West Orkney Mainland. Fluvio-glacial deposits have been recorded in western Hoy, where spreads of sand and gravel occupy the floor of the valleys north of Rackwick.

Post-Glaciation Geology

Significant deposits of peat, laid down in post-glacial times are also found across Orkney, the largest areas being those covering the eastern hills of the West Orkney Mainland and the greater part of central Hoy, with large deposits also found in Rousay and Eday. Most peat is of the blanket type which ranges from less than half a metre to one metre in thickness. Basin bogs are of a relatively small extent, two examples being White Moss and Glins Moss both on Orkney Mainland. There is evidence of peat submerged along the coastline indicating post-glacial sea rise

Recent drift deposits consist of windblown sand and alluvium. The development of bays through sea-level fluctuations, coastal erosion and subsequent deposition has caused the build-up of sand dunes blown inland by the prevailing westerly winds. These sands are found around many of the more open shallow bays, for example, the bays of Birsay and Skaill (Orkney Mainland), Rackwick and Moaness (Hoy), Bow in Burray, and considerable areas of Sanday, Westray and North Ronaldsay. The sand consists principally of fine shell fragments and tends to have a high pH. High-level storm beaches occur in some exposed western shores, for example in Westray and Rousay.

Hydrology

Water is an important feature of the landscapes of Orkney and it has influenced and continues to influence, the physical form of the land. There is very little in the way of fluvial erosion in Orkney at the present day. The loch basins act as receptacles for most of the run-off in West Orkney Mainland. Large rivers are absent from Orkney due to sea-level rise flooding the lower reaches. However, there are many burns that arise in upland areas, most of which have been artificially straightened in the lowlands.

The tidal nature of the main lochs of Harray and Stenness provides an outlet for excess water during periods of heavy rain. Elsewhere on the islands small burns and ditches carry runoff to the sea down coastal inclines, into small bays or through coastal basins. In Hoy the discharge of water is more dramatic, particularly where streams terminate as waterfalls down the high cliffs of the north and west coasts of the island.

Generally, small streams on Orkney do not make a significant landscape impact, and the inland lochs and coastline are the most notable water features. There are several lochs with large areas of open water, usually shallow. They are important features of the landscape and often have considerable ornithological interest. For example, Mill Loch on Eday, a SSSI, is of national importance for breeding red-throated-divers. The botanical interest of the lochs also appears to be high, although the emergent marginal vegetation is often poorly expressed. The large lochs of Stenness and Harray are of special note for their transition from saline to fresh water and are important for the over-wintering of wildfowl. The lowland watercourses and open water bodies are at risk from influence by nutrients from the agricultural land.

The number and extent of lochs within Orkney's island landscapes is an unusual characteristic that emphasises the flooded nature of the archipelago. Within West Orkney Mainland in particular, the large loch basins provide both a physical and symbolic relationship between the land and water.

On the smaller islands, lochs are not as extensive as on Orkney Mainland. They are, nevertheless, important features particularly as sources of fresh water and for wildlife. A common characteristic is their absence of marginal scrub vegetation which emphasises the flooded appearance of the landscape. Many of the island lochs are close to the coast in the low ground behind bays or formed as 'ouses' (small enclosed lochs), trapped behind sand or shingle bars locally known as 'ayres'. Hoy and Rousay are distinguished by their higher inland water bodies cradled within heathy valleys and on peat covered plateaux.

Climate

Climatic factors have influenced the shape of Orkney's landscape through time, from the weathering of surrounding sandstone massifs which formed the predominant geology of the islands, to the severe climatic deterioration which brought northern Britain under the erosive and depositional influences of ice sheets and glaciers. Climatic influences have helped shape the cultural history of the islands, by determining the capacity for agriculture, the form of buildings and the patterns of settlement. Climate continues to have considerable influence on the landscape of Orkney today.

Post Glacial Climatic influences on Orkney

Following the last ice age temperatures rose, melting ice caps and raising the sea level. The land around Orkney was flooded, creating a group of islands. As the sea level rose further, deeper valleys were also submerged leaving only the old hill tops and high ground standing clear of the sea, as numerous islands. The sea level stabilised about 6,000 years ago, but Orkney continues to be submerged very slowly. Evidence for the gradual submergence of Orkney into the sea in post-glacial times is demonstrated by the absence of raised beaches; the presence in many bays of peat beds below the high water mark; and the existence at sea level of lochs with freshwater deposits. The submersion of Orkney has been such that river systems were severely truncated, with only small streams now remaining.

The rise of sea level since the last glaciation is responsible for the "drowned" topography of Orkney. The submergence of the land, coupled with frequent strong winds and the erosive force of the sea, has been responsible for rapid marine erosion along the exposed coasts, particularly along the west coasts of Hoy and Orkney Mainland. This has produced impressive cliffs with their geos (clefts), gloups (blow holes), natural arches, and stacks. The most famous stack is the Old Man of Hoy. The submergence of the landscape has also created distinctive coastal valleys or 'voes' (narrow inlets).

The rising sea during the postglacial period has reworked sediments in the offshore zone and these have been moved onshore to create the sands that now form the popular beaches such as Waulkmill and Skaill. Ayres (bay-mouth sand or shingle bars) have been created by longshore drift, forming ouses (small enclosed lochs) at the coast.

During the changes in climate experienced during the Iron Age, peat accumulated on Orkney. The weather cooled and became wetter which lead to slower decomposition rates. This, coupled with the reduction in tree cover, by both anthropological and natural causes, lead to an accumulation of organic material and the creation of peatland bogs. These bogs have allowed the preservation of artefacts in excellent condition such as the Orkney Hood, a child’s fringed woollen cloak, found near Tankerness in the 19th Century and carbon dated to between AD250 and AD615.

Present-day climate and weather

The climate and weather of the Orkney Islands today is governed by three factors: the intimate relationship with the sea; the open landscape; and the high latitude. The climate is described as hyper-oceanic, producing a cool and moist equitable climate, exposed to the severity of the Atlantic weather systems and salt-laden winds.

Wind from the west and south-east is one of the most significant features of the Orkney climate. Gales are frequent, occurring on 29 days of an average year, with the winter months between October and March being the windiest. The geographical position of Orkney accounts for the gales which frequently affect the islands. Most Atlantic depressions cross Britain on a southwest to northeast path, taking them just west and north of Orkney. These depressions bring strong winds which are unimpeded as they cross the sea, building up very high velocities and carrying salt spray. The impact, sounds and taste of the winds are essential parts of the Orkney landscape, influencing land-use capabilities and building styles. Orkney's few trees reflect the impact of the wind in their sheared and contorted forms.

The winds often pick up heat and moisture from the warm ocean water associated with the northern extension of the Gulf Stream: the North Atlantic Drift. This generates frequent cloud cover and fine persistent rain, but the annual rainfall remains relatively low. This has been attributed to the generally low relief of the islands and the effect of lying in the rain shadow of North West Sutherland. The maritime influence of the North Atlantic Drift brings mild conditions to the islands, keeping winter temperatures above the norm for Orkney's latitude, with average temperatures of 5 to 6° C, and holding summer temperatures down to a cool average of 15° C. The growing season in Orkney lasts for between five and six months, and although it remains marginal for cereal crops, the risk of early or late frosts is relatively low. The high winds have a drying effect on the land, preventing widespread waterlogging.

Salt, carried from the sea into the air or flung from the breaking waves as spray, exerts quite an important influence in the landscape. Along the top of coastal cliffs salt-resistant plants create a carpet of colour when in flower, and the browner appearance of Orkney's pasture in winter is influenced by salt burn. It is also believed that the presence of sea salt in the air contributes to the lack of disease and general health of plants and animals enhancing Orkney's reputation for high quality livestock and farm produce.

Soils

The variation in soil types in Orkney depends upon the parent material: Old Red Sandstone, boulder clay, peat, blown sand, fluvio-glacial deposits, or a basement inlier of metamorphic or igneous rock, depending upon the location. The main influence that soil has on the landscape is on the vegetation and land uses resulting from its composition.

The vast majority of lowland West Orkney Mainland is covered by soils whose parent materials are greyish brown drifts derived from the Middle Old Red Sandstone series flagstones and sandstones. The soils are dominated by poorly-drained non-calcareous gleys (accounting for 40% of the Orkney and North East Caithness area) and peat (covering 20% of the area). 15% of the area is covered by brown forest soils and a further 12% is peaty gleys. The gleys are generally surface water gleys in which the downward movement of water is hindered. The brown forest soils develop on the more strongly sloping land and are often characterised by hardened horizons. The brown forest soils and non-calcareous gleys are capable of supporting arable crops and permanent grass, and peaty gleys can support some grasslands. In some coastal areas, particularly the western seaboard of Orkney Mainland, Rousay and Westray, the drift geology has obviously been affected by the sea to create saline gleys and gley rankers, capable of supporting only a limited range of coastal grasses and sea plantain.

On the lower slopes of the hills in Orkney Mainland, and the higher ground of the western Orkney Mainland coast, Rousay and Eday, there is an abundance of peaty component soils which support Atlantic heather moor. The higher hilly areas of central Orkney Mainland and Hoy have a blanket peat covering which is not conducive to improvement for agriculture.

Most of northern and western Hoy is covered with soil derived from drifts from the upper Old Red Sandstone age. These soils are mostly peaty podzols and gleys which can support heather moor and blanket bog. On the highest peaks, and extending down to about 275 metres above sea level, are alpine and subalpine soils which support vegetation of alpine lichen heath, mountain grassland and upland blanket bog.

Various other soil types are present in the Orkney Islands but are not as widely distributed as those mentioned above. They mostly reflect local variations in the underlying drift geology. At the coast, around Billia Croo and to the west of Stromness the basement complex bedrock surfaces and the soils (peaty gleys and podzols) are derived from a parent group of Old Red Sandstone age mixed with some granites and schist. On the west side of Swanbister Bay is a small area of alluvial soils upon which a range of grasses can survive, along with swamp rush pastures and sedge mires. Shell sands occur in some bays and coastal areas, most extensively in Sanday and in some parts of Orkney Mainland, Westray, North Ronaldsay and South Ronaldsay. The shell sand has produced calcareous soils and gleys capable of supporting dune or machair plant communities. Several different soil types occur at Rackwick, including peaty podzols derived from fluvioglacial sands and gravels from upper Old Red Sandstones. There is also a small deposit of soil derived from basaltic rock drift, supporting herb-rich Atlantic heather moor.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

Like the majority of Scotland, Orkney’s landscape has been shaped by the generations of people who have lived there in the past; present-day inhabitants continue to influence the landscape. Orkney is extraordinary in terms of both its ever-increasing number of known archaeological sites and the remarkable state of preservation in which many are found. It is also unusual because, as Orkney has been virtually treeless for millennia, it is possible to view all but the earliest monuments in something akin to the landscape in which they were created in terms of skyline and landforms, at the very least. There is a huge variety of site types across the islands, reflecting differences in geography, land use and past cultural groupings. The evolution of traditional land uses, like agriculture and defence, continue to shape Orkney and their influence is joined by more modern land uses, such as energy production.

History of settlement and land use

The interaction between physical and cultural forces is clearly demonstrated in Orkney, where human activity can be dated back to at least 7000 BC, although isolated finds have been made which date back to the Palaeolithic era. Physical factors such as soils and climate influenced human activity, as did the availability of plants and animals, and the early Orcadians began the process of adapting to and modifying the environment in their building, farming, domestic and ritual practices. The construction of monumental sites in prehistory, and the often-observed phenomenon of the re-use of sites over millennia, sometimes resulting in the creation of artificial mounds over time, mean that ancient activities still form significant and highly visible aspects of the modern landscape. The following paragraphs outline briefly the influence of human cultures in the Orkney landscapes.

Mesolithic C7000-4000BC

The Mesolithic was a period when humans lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers, migrating seasonally and building only temporary shelters. No permanent stone structures were left behind, so in comparison to subsequent periods, material remains are often scant.

In Orkney, this activity took place in a landscape much removed from that of the 21st Century. Sea levels were lower and the familiar low-lying islands we see today were the hilltops of one, and then two large islands. In several instances, modern lochs and bays were wetlands.

Palaeo-environmental work suggests that high ground was vegetated by open grassland, hazel, birch and willow. Lower ground, now submerged, was vegetated with diverse mixed woodland. This is exemplified by the forest remnants found in the Bay of Moaness on Rousay and Otterswick Bay on Sanday, where researchers have identified wetland woods of hazel and willow underlying sand deposits. Such woodland, complemented by rich coastal resources, could have provided ample food and shelter - the ideal environment for human activity. As a result, a paucity of Mesolithic finds might be expected in Orkney with most sites located beneath modern sea level. This is supported by research that found evidence of submerged stone structures, suggested to be early Neolithic, in the Bay of Firth.

However, there have been many Mesolithic discoveries made in Orkney. Only one settlement site has been located to this point - Links House on Stronsay. Here, a seasonal occupation site was identified which may have been used over a considerable period of time. Stake/post holes, pits and other features have been excavated and almost 25,000 pieces of flint including points, awls, microliths, and blades found. The site has been radiocarbon dated to 7050–6650 BC.

Aside from the Links House site, most Mesolithic finds consist of ‘scatters’ of tools, flint flakes or other debris associated with tool production. These have been located variously by fieldwalking ploughed fields, as stray finds, and during excavation of sites from later periods. Such discoveries have been made on Sanday, Stronsay, Papa Westray, Westray, Rousay, and in multiple locations in Mainland Orkney, for example Yesnaby, Loch of Stenness and Wideford Hill.

Considering the low archaeological visibility of the Mesolithic in general, and the altered geography of Orkney, the spread of discoveries described might be suggestive of more than just the occasional visitor in this era. The naturally evolving landscape and environment have been conducive to human activity for millennia. There are indications that humans may also have started to influence the environment at this juncture. It had been suggested that episodes of forest burning, represented in the palaeo-environmental record by microscopic charcoal fragments, indicate deliberate acts designed to promote grazing land for prey, but natural explanations are equally viable at this stage of prehistory.

Neolithic 4,000 BC - 2,200 BC

The Neolithic saw the advent of permanent human settlement, farming, monumental ritual architecture, communal burial and the development of a more complex society. This new way of living spread slowly from Europe, complete with new types of stone tool, the first pottery, domesticated animals and crops. In this era, temperatures were slightly warmer than today, ideal for the development of agriculture.

Palaeo-environmental records show the impacts that this change in lifestyle had in Orkney. Woodland cover decreased through the early Neolithic until the forests survived as only isolated pockets of trees by around 3500BC. By the late Neolithic, trees were almost as limited in their extent as they are today. Meantime, sea level continued to rise and the islands we know today were starting to form, but swathes of dry land persisted which in modern times are submerged. Orkney’s landscape and environment were now demonstrably subject to the influences of both natural and human activity.

Against this backdrop, human society appears to have flourished. Midden deposits show sheep, pig and cattle being farmed, wheat and barley cultivated but also ongoing utilisation of wild resources: red deer, seal, molluscs, fish and whale. The population is assumed to have increased as settlements and ritual monuments were constructed across the archipelago. Many of these sites are considered to be of worldwide importance today, attracting visitors and researchers alike to Orkney. The best known of sites are famous because of their state of preservation and their dramatic appearance within the low, sweeping Orkney landscape.

This preservation is due to a number of factors. Natural, windblown sand deposits, sometimes metres thick, covered hectares of land and, in some cases, filled and covered sites, concealing and protecting them. This was the case at the famous late Neolithic site of Skara Brae, which was exposed by a storm in 1850. Skara Brae also illustrates well another preservation factor: the use of stone as a building material.

Stone became the predominant building material during the course of the Orcadian Neolithic, it is thought partly due to deforestation and partly for cultural reasons, whereas elsewhere in Britain timber remained the principal building material. Not only have monumental stone circles and chambered tombs survived intact in Orkney, so have domestic settlements. Buildings and, in some cases, stone furnishings have been discovered. Skara Brae, for example, presents a vivid impression of how people lived, complete with houses, interconnecting passages, beds, boxes, fireplaces, clay ovens and stone drains.

The third principle factor is the rural nature of modern Orkney, and the limited areas of intensive agricultural activity. This means that not only the quality, but the quantity of known surviving sites is high. It is possible to envisage the complete Neolithic landscape - the land, the settlement, ritual and burial sites, in parts of Orkney. This has been recognised by UNESCO, who proclaimed ‘The Heart of Neolithic Orkney’ as a World Heritage Site in 1999, acclaimed as one of Western Europe’s richest surviving Neolithic landscapes. Global interest in Orkney’s Neolithic has led to it being a focus of research and excavation over the last 20 years, and our understanding of this period is constantly evolving.

Currently, the Neolithic is divided into two overlapping periods: early and late. The transition occurred around 3100BC. During the Early Neolithic, Orkney-Cromarty passage graves (e.g. Midhowe on Rousay) and both timber (e.g. Smerquoy) and stone houses (e.g. Knap of Howar) were constructed. On some sites, both stone and timber houses are represented (e.g. Wideford Hill and Ha Breck on Wyre). The houses notably mirror the contemporary tombs in plan. Round bottomed ceramic vessels known as Unstan Ware were used.

The Late Neolithic saw a shift to the construction of Maeshowe-type chambered cairns (e.g. Maeshowe itself and Quoyness on Sanday). These have a central chamber with radiating side cells. The houses (e.g. Skara Brae, Barnhouse), now only constructed of stone, are again reminiscent of these tombs in plan. A ceramic style known as Grooved Ware is associated with this period.

The field of Neolithic research in Orkney is huge, and it is not appropriate to try to cover it fully here. As stated above, in the Neolithic the evidence points to humans shaping their environment through deforestation and the introduction of crop species. There are also examples of their use of the landscape for more than simply survival. This is most obvious in the Heart of Neolithic Orkney, where an almost theatrical effect is created by the siting of The Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness at either side of the massive ceremonial complex of the Ness of Brodgar, all within a low-lying basin surrounded by hills. This use of landscape continues into the Bronze Age, when, although much else appears to have changed, on-going use of this basin for ceremonial and burial purposes is indisputable.

Bronze Age 2,200 BC – 700 BC

The change from the use of stone to bronze for tools and weapons is not as apparent in Orkney as in other parts of Britain, as very few bronze objects have been recovered which date to this period. However, the differences between the Bronze Age and the Neolithic are stark.

The natural environment continued to change. The landscape was becoming comparable to modern Orkney in terms of sea level and forestation. Nevertheless, a marked climatic deterioration began to take place. The mean temperature dropped, rainfall increased and blanket peat began to form in upland areas. Peat bog and heathland became widespread.

Construction of monumental sites ceased and a general shift from communal burial to individual burials is seen across Europe. Many of the burials are cremations, placed in small stone coffins or cists, which were then covered by an earthen mound or cairn. Hundreds of these burial mounds are still evident across Orkney, although many have been truncated by ploughing. Excavations have shown cemeteries can survive below ground even where this is the case. On Orkney, notably, there is continuity from the Neolithic of the importance of specific places for burial in spite of the change in burial type. Small Bronze Age burial mounds cluster around the grand sites in the Heart of Neolithic Orkney, for example. On Sanday, Bronze Age cists can be seen inserted into the top of Neolithic chambered cairns at Tofts Ness. Here and at Elsness, also on Sanday, crescentic lines of Bronze Age mounds arc around chambered cairns. Evidence for Bronze Age settlement is more elusive than that of the Neolithic. Relatively few sites are yet recognised and fewer have been excavated. A notable exception is Links of Noltland on Westray where both Neolithic and Bronze Age remains have been found. Here, as was the case at Skara Brae, settlement remains were encompassed and protected by windblown sand, only to be revealed in the 1800s by aeolian erosion.

Work here has identified a cemetery, fields and around ten Bronze Age buildings. The cemetery was located close to the houses, with around 50 individuals represented as cremations and inhumations.

Another distinctive site type normally associated with the Bronze Age is the burnt mound. These typically kidney-shaped grassed mounds are always located beside a water source, be it a stream or a constructed cistern, as at Meur on Sanday. They are formed of burnt and heat-cracked stones which have been piled around a trough and a fire. The primary function of the sites appeared to be heating water in a stone lined trough simply by dropping in heated stones. The purpose of this has been suggested as cooking, processing hide or use as a sauna. Orkney burnt mounds differ from mainland Scottish examples in having associated structures and are known as complex burnt mounds.

Burnt mounds are interesting in their frequency. This may indicate a higher population than indicated by the paucity of known settlement remains. Orkney’s crannogs may also fit into this time period, but as yet little research has been carried out to describe and quantify the site type or date known examples. Elsewhere in Scotland, crannogs have been found to be multi-period sites with dates spanning the Neolithic through to the medieval period.

Iron Age: BC 700 - AD 400

By 600BC, continued climatic deterioration meant that the climate and landscape of Orkney because similar to today a. Less upland cultivation was possible and there were increased pressures on low-lying areas. However, cultivation of crops and farming of sheep, pig and cattle continued, as did exploitation of available natural resources such as red deer and molluscs.

In contrast with the Neolithic and Bronze Age, finds of burials are not common, although an Iron Age cemetery, which was in use from 200BC to 500AD, was excavated at Knowe of Skea on Westray. Here, collapsed Bronze Age structures were re-used to contain inhumations and cremations.

Most notably, this period saw a return to monumental building, but now of substantial, double-walled stone towers known as brochs. These often had surrounding settlements and external fortifications such as those at Gurness and Midhowe, Rousay. This may indicate a change in society from that occupying the more dispersed settlement of the Bronze Age. Most brochs were constructed in defensive locations, on high ground or at the coast. This defensive nature could indicate a preoccupation with control of land, perhaps triggered by the decline in the productive land caused by climate change.

There are a large number of brochs in Orkney, all of which have long since partially collapsed and now survive as massive grassed mounds, highly visible in the landscape. Many were excavated historically. Sections of walling and intra-mural features like stairs and cells have in some cases been left uncovered and can still be seen.

In many cases, broch sites have been re-used after the original structure fell out of use, in several cases for the construction of early churches. Some sites remain in use today, with modern farms built on large mounds which are believed to be broch sites, for example at How and Westbrough on Sanday. In particularly flat areas like Sanday, these mounds, which have retained their significance as places for millennia, are the most prominent features in the modern landscape.

Brochs are the most visible remnant of the Iron Age today, but they were not alone in the Iron Age landscape. Roundhouses, such as the early Iron Age example excavated at Tofts Ness on Sanday, showed undefended sites existed alongside brochs, as did souterrains: underground passages used for storage which are normally associated with roundhouses.

Later in the Iron Age, there was a move away from the construction of defensive sites back to a landscape of undefended farmsteads. For example, at the Cairns broch, the defensive ditch was partially infilled and a later Iron Age building used for metal-working was constructed over the top of it. Wheelhouses also appear: undefended roundhouses with internal divisions which resemble a spoked wheel when viewed in plan. These are common in the Western Isles, but there are eight known examples in Orkney.

Although the Orkney Islands were known to the Romans, Roman occupation did not advance this far north. Shards of Roman pottery have been found at broch sites and indicate a movement of goods through trade or contact.

Pictish Period c. AD300 - 900

The period, which could equally be referred to as the Later Iron Age, is when early historical references first give us hints as to who was living in Scotland. Debate surrounds the dating for the commencement of a 'Pictish period' and the origins of the Picts. The Picts are accepted to be the indigenous Iron Age tribes who were given a new name that was derived from the Roman descriptions of them as Picti (painted people). Later sources tell us that Orkney was within the Pictish cultural orbit by the beginning of the 7th Century and was administratively absorbed into the Pictish Kingdom by the early 8th Century. At that time it had its power centre in Tayside and was the strongest political force in northern Britain.

The most archaeologically visible aspect of Pictish culture is the carved symbol stone. Only eight symbol stones have been recovered from Orkney, the best-known being that on the Brough of Birsay, just off Orkney Mainland. Here, the remains of a Pictish period settlement are directly overlain by subsequent Norse activity. Structures dating to the Pictish period include wheelhouses and brochs, and the so-called figure-of-eight houses like the one excavated at Buckquoy, which are again overlain by Norse structures.

Little is known of Early Pictish religion, rituals, or burials, which appear to be within long and short cists. The single most influential development in Orkney in Pictish times was the introduction of Christianity. First contact with Christianity would seem to be around the 6th Century AD but there was little church authority until the 8th Century. The remains of chapels situated on broch mounds are a visible reminder of this period.

Norse Rule

The influence of the Norse on Orkney was extensive and persists today. They were seafarers and farmers, they invaded and they settled. From a Norwegian perspective the lands of Orkney would have been temptingly fertile, while the sheltered bays would have been familiar and practical. This package was conducive to their economy of mixed farming and exploitation of maritime resources.

They stayed on Orkney and took control, be it forcibly or with consent, and they brought their language. The origins of almost all current place names are derived from Old Norse and either describe the location or indicate the status and size of the settlement. The easily recognised elements "Bu", "Bay", "Skaill", are known to mark the farmsteads of especially high status. They are invariably sited in prime positions and the locations often remain in use today. ‘Garth’ refers to the subdivision of land and the creation of new settlements. Large estates typically generated outset settlements - ‘umbesetts’ - around them, which were inhabited by a dependent population. Kirkwall derives from the Old Norse Kirkjuvagar or church on the bay, probably a reference to St Magnus Cathedral.

Early Norse remains include boat noosts - slipways into which longships could be pulled to protect them from storms - and burials. Noosts, often made of stone, are visible around the coast of Orkney. Orkney also has the largest concentration of pre-Christian Norse graves in Scotland, including extensive cemeteries at Pierowall in Westray. Elaborate boat burials were excavated in Westness from 1963 onwards, with human remains found - men and a woman with her newborn - as well as weapons, jewellery and tools. One of the men shows the remains of arrows in his body, suggesting a violent death. The Scar Viking boat burial site on Sanday was excavated quickly before autumn storms could wash away the site and the dated artefacts put the grave date to between 875 and 950 AD.

The Norse brought rectangular house construction, a style that has persisted from that time. The longhouse comprised a divided core area for both the family and livestock, to which further extensions were added, literally creating longhouses. They frequently had a kiln for drying grain at one end, a necessity in such an uncertain climate. These traditional farm buildings were constructed with low eaves, mostly of a single storey with thick masonry walls and small window openings. Roofs were covered with thin flagstones laid as a square or as large overlapping wedge shapes. Weighted thatch or turf was traditionally used, but few retain this roof covering today. These solid, squat forms were designed in response to the elements and technical limitations.

More elaborate structures - Norse halls, built of timber or stone - also occur in Orkney. Examples constructed of both building materials have been excavated at Pool, Sanday, where they form the latest phase of a multi-period mound established during the Neolithic. The postholes of the timber hall were massive, suggestive of timbers that must have been imported from elsewhere. Another recently excavated stone-walled example at Skaill, Rousay, cited as a ‘drinking hall’, contained stone benches along each long side.

From the Norse period onwards, traditional techniques led to the general use of 13 feet as the internal width, this being the maximum span economically achievable with the type of timber generally available. The continuity of the longhouse tradition and the ease with which drystone construction could subsequently be altered or repaired make it very difficult to precisely date Orkney vernacular architecture. The longhouse is evident at Norse settlement sites such as the Brough of Birsay. The influence of this form can be seen throughout Orkney today.

Orkney has several religious and secular remains from the 12th Century onwards. These include the Round Church, Orphir and the prominent St. Magnus Church on Egilsay. The most famous is probably St. Magnus' Cathedral in Kirkwall, a magnificent red sandstone structure, with the oldest parts dating from 800 years ago. Whilst the Cathedral has been progressively extended and maintained over the centuries, two other notable Renaissance palaces suffered during periods of conflict and now stand as ruins. These are the Earl’s Palace in Birsay and Bishop's Palace in Kirkwall.

The Norse period also sees availability of more historical sources to colour in the history behind the material remains we see in the landscape. The Bandamanna saga from Iceland, which takes place sometime after the year 1000 AD, recounts the voyage of a young man named Oddr who, thanks to favourable winds, is able to sail all the way from Iceland to Orkney to collect malt and grains (corn) for a wedding feast without having to hardly lift a finger. Whether this is a true tale or not, it indicates that Orkney was already established as a part of the Norse supply chain, whether through trade or pilfering. The 'Orkneyinga Saga', compiled in the early 13th Century concerns events of the previous century. It paints a vivid picture of some of the most powerful men in the Norse world - the Orkney earls and conflates their exploits to mythical levels. Upstanding remains of churches and monasteries can be visited at St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orphir, Egilsay, Birsay, Tuquoy in Westray and Eynhallow. Cubbie Row Castle at Wyre is one of the earliest stone castles in Scotland and was built around 1145 by Kolbein Hruga, of Norse origin.

Multi-period settlement

The re-use of sites through prehistory and history occurs throughout the periods of human occupation described above. The reasons behind this are likely to be a combination of practical and symbolic. From a practical point of view, location of sites is a factor. Sheltered bays or valleys beside water sources, or places where particularly desirable resources of the time happen to be concentrated, will always have had a draw. A site, especially stone-constructed, which has fallen out of use is an easy source of building materials. There are many examples of sites where old buildings have been levelled, some stone removed for reuse and the remainder of the structures backfilled with rubble or midden material. New buildings were then constructed directly on top. This process has often happened repeatedly on the same site. Some coastal examples are being actively eroding by the sea, proving an opportunity to glimpse the many layers of human activity, as at Pool on Sanday.

From a symbolic point of view, the levelling of old buildings with all their intrinsic associations and the imposition of a different style of structure on the same site could be seen as a stamp of dominance. This might be an appropriate interpretation for the Norse re-use of Pictish sites as at Brough of Birsay, and the Early Christian chapels sited on brochs, as at Peters Kirk in Evie. Whatever the various factors involved, the impact on the modern landscape is undeniable. These anthropogenic accumulations, alongside mounds created by the collapse of massive brochs, are significant features, visible for miles and contrasting with the rolling natural landscape. The many examples on the flat landscapes of Sanday and North Ronaldsay, as touched on above, remain the most prominent features in the landscape.

Scottish Feudal Rule

Orkney was ruled from Norway until 1468 when it was made part of the dowry of Margaret, daughter of Christian I of Norway for her marriage to James III of Scotland. Both Orkney and Shetland were annexed to the Crown of Scotland in that year, and Kirkwall was elevated to Royal Burgh status by James III.

The 16th Century saw the first resurgence of major building works on monumental buildings since the 12th Century golden age of St Magnus’ Cathedral and the Bishops Palace at Kirkwall. A busy period of castle/palace/fortified mansion construction began in Orkney with the building of Noltland Castle in 1560-74. Located near Pierowall on Westray at what may be Orkney’s best natural harbour and in an excellent defensive position, the castle was constructed by Sir Gilbert Balfour who had connections with Mary Queen of Scots.

In 1560 the Crown estates in Orkney and Shetland were gifted to Lord Robert Stewart by his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots; later revoked in favour of making her new husband, the Earl of Bothwell, the Duke of Orkney. On her defeat, Stewart reclaimed the islands using his new powers to raise rents and taxes and control trade. Possibly inspired by the Renaissance design of Noltland Castle, Robert Stewart had the Earl’s Palace at Birsay built between 1569 and 1574. This palace was constructed as a fortified house in the newly fashionable Renaissance style, with early records showing the presence of gardens around the main building. The Palace dominates the current village of Birsay and the surrounding area and reinforces the importance of this area of Orkney in this period.

Robert Stewart was succeeded by his son Patrick in 1593 who carried his powers further, enforcing labour for quarrying to supply his private building projects including the Earl's Palace in Kirkwall. The Earl’s Palace is one of the finest examples of Renaissance architecture in Scotland. Construction began in 1600 and the intention was to include the recently restored and reconstructed Bishop’s Palace adjacent to it. This plan was never realised as Patrick Stewart ran out of funds; however, the Earl’s Palace was largely completed. The Stewart rule ended with Patrick and his son Robert being executed for treason and the Earl’s Palace became the residence of the bishops of Orkney. These fortified palaces demonstrate both the turbulent nature of this period in Orkney and Scotland but also through their Renaissance designs the wider connections and links with Scotland and Europe.

The earliest recorded development in Stromness was in the late 16th Century when an inn was opened to cater to the increasing number of vessels heading for the Atlantic to develop trade with America and the Far East. In the mid to late 17th Century, a Cromwellian garrison was stationed in Kirkwall, occupying the town; a fort was built on the east shore although no trace of it now remains. By 1750, the title Earldom of Orkney had lost all connection with the islands.

Land Tenure and Historical Developments in Agriculture

The form of the historic landscape in Orkney is complex, with different forms of land use overlying one another. In parts of Orkney, the remains of medieval field systems and land tenure can still be seen in the form of turf head dykes. A survey undertaken at Eynhallow in 2015 identified a complex multi-period field system with areas of pre-improvement rig and furrow and later rig and furrow both overlying earlier turf banks of a past field system. Geophysical survey at Skaill Farm on Rousay indicated the presence of earlier boundaries on a different alignment to the present post-medieval boundaries.

The traditional system of land tenure in Orkney, ’Udal law’, differs in some respects from that in the rest of Scotland, and has a Norse origin. Udal inheritance rejected primogeniture and shared out property among all the sons. This led to excessive fragmentation of holdings in some districts. From the 16th Century onwards both the Udal and Scottish feudal system were used in Orkney with the usage of the feudal system accelerated by the Stewart earls, the Episcopalian bishops in the 17th Century and the merchant lairds of the 18th Century.

It is thought that in pre-enclosure times the ‘tunship’ would have been a small unit comprising houses each with some private land, one or more blocks of communally held land in ‘runrig’, and shares of outfield grazing and shore resources. Knowledge of tunship settlements is largely derived from the old Rentals, tax-rolls showing the various skats or taxes due to the Earls or Bishops from each farm or tunship. Under the runrig system the different types of land, better and worse, were shared out amongst everyone in long strips, with some land left uncultivated between the strips and no formal boundaries.

Around the middle of the 18th Century, some small industry had been introduced: linen and yarn manufacturing and kelp-burning. Through the latter, large estate owners made a lot of money from seaweed prepared into solid kelp which was shipped southwards for glass and soap manufacture. The landowners coerced their tenants into kelp manufacture by leasing cultivated land at very high rents, forcing tenants to seek additional employment. The fragmentation of agricultural holdings over the years was further encouraged by 18th and 19th Century mercantile landlords, who could exploit a large pool of low-paid dependent labour in their development of the kelping and fishing industries. Due to Udal law the ownership of adjacent land in Orkney commonly extends down to the low tide mark, allowing landlords greater control of the total available resources. The kelping industry left many backshores marked by groups of circular burning pits. A particularly well-preserved group of kelp burning pits can be seen at Crook Beach on Sanday. The practice of tangle gathering, now for the chemical industry and cottage industries, continues to feature in such areas, with elaborately improvised drystone and driftwood structures.

The main alternatives to working the land were provided by the Hudson Bay Company, whaling and fishing fleets. The former had a supply and recruiting station in Stromness from which young men were recruited to work on trading posts in Canada. Stromness was a freshwater stop for John Franklin and Captain Cook on their way north and the Orcadian surgeon John Rae was recruited from here by the Hudson Bay Company. He was later important in discovering the final part of the Northwest Passage and retracing the last steps of John Franklin’s doomed expedition. These maritime links further demonstrate that, as in earlier times, Orkney was well connected to the British mainland, Europe and America and ideas and goods spread there more quickly than other more inland areas of mainland Scotland.

19th and 20th Century Agricultural Changes

At the beginning of the 19th Century, subsistence agriculture prevailed: oats and bere were grown on better land but the land itself was often divided under the runrig system of unfenced strips. The kelp industry was profitable while the superior Mediterranean product was unavailable due to the Napoleonic wars and the landowners had little incentive to modernise the agricultural sector. The kelp trade collapsed with the defeat of Napoleon and, in 1823, the Leblanc process for cheap synthetic soda-making further damaged the industry. This left the lairds little option but to make more money from their land by increasing efficiency and productivity.

Whilst the rig system was removed in the 18th Century, the field patterns remained and it was not until the mid-19th Century that large-scale consolidation took place. The modern landscape of rectilinear fields mainly derives from this period of rearrangement, brought about by the influence on estate owners of new ideas from mainland Britain. The invention of steamships and their subsequent use for commercial haulage was the key technological innovation that made possible the change from mixed subsistence farming to specialised store cattle production. Steamships opened up the markets of mainland Britain and facilitated the importation of materials such as coal and machinery. This encouraged and enabled investment in agriculture and, consequently, the agricultural landscapes of Orkney were modernised and altered on a large scale by both existing and new landlords. Several landowners used wealth generated in England, Scotland and the colonies to finance ambitious land improvement and house building schemes. One of the most successful of these landlords was Major Balfour, who bought Shapinsay in 1782 and proceeded to make many agricultural improvements through enclosure, cultivation of new lands, and rotational cultivation. At Shapinsay virtually the whole of the island was divided into fields of four hectares, a feature that is still apparent today.

It was also at this time that many of the old house groupings were broken up and new settlement patterns were created in relation to the consolidated farm units. Many Orkney houses date from this period. Far-sighted landowners provided their tenants with longer leases giving them the incentive of greater security to undertake long-term improvements. Widespread enclosure took place, new ploughs were introduced, and new types of seed and livestock were tried. By the late 19th Century, the arable acreage in Orkney had increased. However, it was livestock that became the basis of the newfound prosperity in agriculture.

There was little land clearance in Orkney, unlike neighbouring Caithness, however, Rousay suffered from mass evictions around Westness and Quandale. Until then, the area had been a good corn growing area but the landowner of the time favoured sheep farming. The area is still deserted with ruined crofts, the remains of turf dykes and runrig farming still apparent. Smaller scale enforced movement of people also occurred in areas of other islands such as Sanday and Eynhallow. In the late 19th Century, the Crofter Act was passed, introducing security of tenure, heritable tenure, and fair rents which reduced the risks for tenant farmers.

Wealthier homes from the 18th and 19th Centuries frequently adopted one-and-a-half or two-storey forms with simple formal elevations generally comprising gable chimneys, deeply recessed doors and windows, few dormers and four-pane windows of small size. The 'ink pot' house, an imported form generally used in manses, is an interesting building design employed at several locations, such as West Manse on Sanday. It has centrally positioned fireplaces and chimneys which form the core of the house. The result is a distinctive formal elevation of two storeys with a pyramidal roof whose apex is one or two large chimney stacks.

The success of the agricultural reforms allowed landlords and wealthy entrepreneurs to build country houses. The architectural sophistication and grandeur of these properties contrast sharply with the small, utilitarian farmsteads. The country houses and castles of Balfour (Shapinsay), Melsetter (Hoy), Tankerness, Skaill, Woodwick, Clestrain and Breckness (Orkney Mainland), Trumland House (Rousay), and Carrick House (Eday) are examples. Some were used primarily in summer, the winter residences being in the towns of Kirkwall or Stromness or further afield. Unlike their counterparts in mainland Scotland, these houses generally do not have extensive or significant designed landscapes, with the exceptions of Balfour Castle and Melsetter House (which are both included on the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes) The designed landscapes around the estate houses provide almost all of the established rural woodlands in Orkney and are therefore a significant landscape element. The cores of estates are recognisable by the presence of rectilinear drystone dykes, gateways or lodges; small shelter woodlands and walled gardens; as well as home farms or small-scale designed settlements. The houses are located to capitalise on views of the coast and access to the shore for boats, and to the road network. Built to reflect current fashions, one or two of the houses are manifestations of the Scottish Baronial style, such as Balfour, on Shapinsay, while Melsetter House on Hoy is a good example of the Arts and Crafts design movement. Many of the 19th Century grand houses were successfully occupied only by their builder's generation: their upkeep in the Orkney climate has proved to be an onerous obligation for contemporary owners. Several are only partially occupied and some are searching for other uses such as visitor centres or hotels.

Several fine water mills can still be seen in the Orkney landscape. These were built in areas with slopes that are steep enough to generate an adequate flow of water in the burns to drive the mill wheels. Primitive mills were designed with a horizontal wheel, and several sites have been found in Orkney lowland basins. These were designed to make the most of a low head and volume of water and the style dates from at least Norse era but maybe earlier: there is evidence of one at Earl’s Bu, Orphir that probably dates from the 9th Century AD. The last surviving horizontal mill on Orkney in working order, after restoration, is the early 19th Century Click Mill at Dounby, Orkney Mainland. The water mills proved to be more reliable than wind-powered mills which suffered in the ferocity of Orkney Islands’ gales. The mills were largely used to grind grain and represent the legacy of more intensive arable cultivation. The mill at Barony, Birsay (West Orkney Mainland) built in 1873, has been restored to a working mill and produces beremeal using an ancient form of barley tolerant to the growing conditions on Orkney, as well as northern and Scandinavian strains of wheat and oats suited to the shorter growing season and windy conditions. There are older remains of previous mills adjacent but these have not been restored to date. A small number of mills was also used in textile production, especially tweed: there is a small modern mill housed in a disused lighthouse on North Ronaldsay. The most significant mills include: Finstown, Kirbister, Voy, Rango, Suckquoy and Graemeshall on Orkney Mainland; Saviskaill Mill on Rousay; and Elwick Mill on Shapinsay. A few mills have been restored and converted into large residences or visitor centres, for example, Tormiston Mill near Maes Howe. However, most mills lie derelict or used for storage. Despite this, the remaining mill buildings are important features in the countryside.

In the flatter parts of Orkney Mainland, and on the other islands, wind power was tried from necessity in a few locations. Windmills were built with a stone base on which timber housing and the sails were mounted. These no longer function and only the stone base remains as a squat tower. Wind power was also used on a domestic scale. Small sails were driven from stone turrets attached to the dwelling house, for example at Sangar on Westray, employing maritime technology and canvas sails.

Almost all of Orkney’s lighthouses were built by the Stevenson family in the 19th Century. Two of the earliest lighthouses in Britain were built to prevent ship losses in Orkney's northern waters, and they are still operational: Pentland Skerries (1794) and Start Point (1806) which is painted a distinctive black and white. All the lighthouses are elegant structures and prominent landmarks with their livery of white, or white with black or red stripes. The other notable lighthouses are at Noup Head, Westray; Dennis Papa Stronsay; the Brough of Birsay; Graemsay; Cantick Head, South Walls; and at Rose Ness, East Orkney Mainland. The last built in Orkney was Tor Ness in 1980. All are still in use marking potentially dangerous promontories and aiding maritime navigation.

During the Napoleonic and British-American wars, defences were built to protect British merchant shipping from the French and American privateers who were wreaking havoc on ships travelling through the Pentland Firth or around Orkney. The Hackness battery was built in 1813 and a year later the two stone Martello towers (Hackness and Crockness) were constructed along the coastline at North and South Walls. Each tower was built to house a nine-man garrison. Their design, incorporating ventilation and freshwater supply, reflects architectural and engineering expertise of a very simple, yet effective nature. They represent two out of only three Martello Towers ever constructed in Scotland. In 1866 the battery and towers were upgraded in response to a perceived threat from the American Fenian Brotherhood: outdated guns were replaced, and the barracks improved.

Orkney’s 20th Century wartime role

The enormous impact on the Orkney Islands of both World Wars has left an important legacy of military structures, such as coastal defence batteries, observation towers and searchlight emplacements, many of which do not survive elsewhere in the UK. The built heritage and archaeology from this era should be considered as part of Orkney’s vernacular, as it is a significant and recent phase in the history of its built heritage that has left a lasting impression on the landscape.

Prior to the First World War, Britain was considered to be most at risk of attack from continental Europe and the British Navy was based on the south coast of England. The changing political situation at the beginning of the 20th Century meant that the threat changed to focus on the German Navy in the Baltic Sea.

Orkney had been recognised historically as a strategic location. The sheltered and deep waters of Scapa Flow have been used throughout the centuries for travel, trade and conflict. Scapa Flow is one of the world's largest natural harbours and it is mostly enclosed by surrounding islands, including mainland Orkney, Flotta, and Hoy where the town of Lyness overlooks the Flow. It was this, combined with the location of the Orkney Islands was the impetus for moving part of the Grand Fleet to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

The harbour at Lyness was chosen as an ideal strategic location for the Royal Navy base in both World Wars. The base supported thousands of military and civilian personnel. Lyness became a self-contained town that provided accommodation and recreational facilities for the servicemen and women who were stationed there during both World Wars. This activity during wartime had a huge impact on the Orcadian landscape.

The immediate setting of the military buildings in Orkney would have changed soon after the end of the Second World War when the personnel left and a large proportion of the naval military buildings were dismantled or demolished. Nevertheless, the remaining buildings provide an important context and retain a clearly readable historic setting. The waterfront is still recognisable as a naval base and continues in use for ferries and marine energy support vessels. Visible remains of the military presence in Orkney can still be seen throughout the islands, for example at Roan Head on Flotta and the Holm and Houton batteries on the Mainland.

There is a wealth of underwater archaeology from both World Wars. Orkney has several designated and protected sites in the waters of Scapa Flow. In 1916, Lord Kitchener and the crew of HMS Hampshire perished when the boat hit a German mine: there is a stone tower at Marwick Head to commemorate this. In 1919 the German Grand Fleet was captured and escorted to the Flow where it was interned. Rather than surrender, the Fleet was scuttled, with nine German soldiers killed. Several ships were salvaged, but eight hulks remain. The remaining wrecks are protected as scheduled monuments and form a key feature for modern diving enthusiasts.

In the Second World War, the Royal Navy was again stationed at Scapa Flow to contain German naval activity and protect North Atlantic routes to the USA and Russia (Orkney played a key role in the support and defence of the Arctic Convoy route to Murmansk). A month into the conflict, a U-boat entered Scapa Flow and sank HMS Royal Oak by torpedo. Over half the crew lost their lives. This led to an increase in defence structures being constructed. There are concentrations around Lyness and Rinnigill on Hoy where the ruins of military buildings are widespread, creating a distinctive character and sense of history through their abandoned appearance. Many concrete and brick structures from the Second World War remain throughout the archipelago; this method of construction contrasts with more typical Orkney architecture; these buildings now form a key part of Orkney’s landscape.

The largest features from this period are the Churchill Barriers: concrete block causeways that link the South Isles to the Orkney Mainland and close the eastern passages into Scapa Flow. In conjunction with the Barriers, coastal defence structures were built to guard the remaining passages into Scapa Flow. These comprise concrete gun emplacements and grey searchlight towers with projecting flat roofs and slot windows, and they are most visible when approaching the islands by ferry. Air defences were also developed, using flat areas of Orkney Mainland for fighter and bomber aerodromes. Airstrips were developed at Twatt, Skeabrae and on the site of the present Kirkwall Airport. Only the last is still in use: the other sites retain the remains of buildings and air raid bunkers which are largely overgrown.

The dramatic increase in population during the war allowed the mixing of people from different backgrounds and enriched the cultural history of the islands. The structures built to accommodate the troops and to serve the military purpose have left a poignant physical legacy in the form of their contemporary ruins.