Landscape Character Assessment: Inverness - Landscape Evolution and Influences

There is a pdf version of this document at the foot of this web page.

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten,

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some reports have been combined where original LCA area coverage was very small.

The new documents include photographs. They do not include the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of;

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot/

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

The content of this document was drawn from the background chapter information in the “NatureScot Review 114 – Inverness and District landscape character assessment”, 1999, John Richards.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

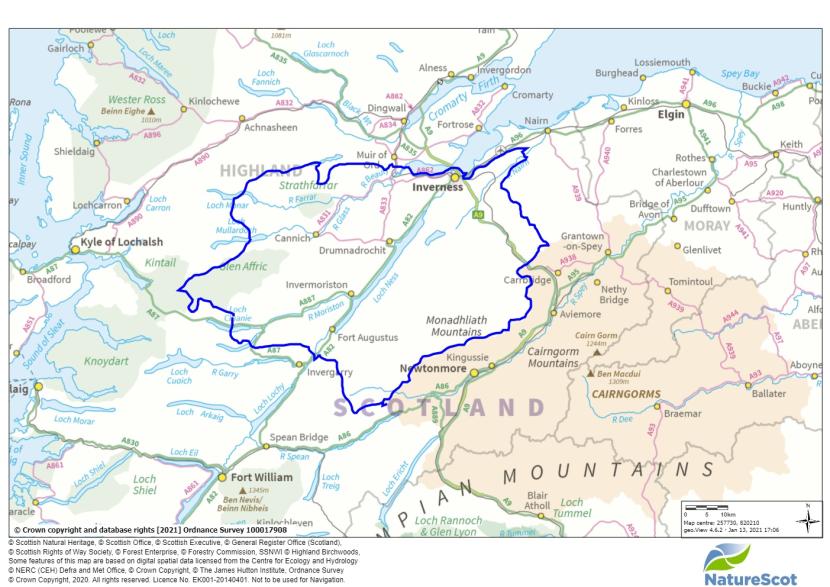

The study area extends from Inverness in the north, to Fort Augustus in the south. To the west, the district includes the hill ranges which encompass Glen Affric and Glen Strathfarrar, and to the east, the Monadhliath Mountains. It lies within the wider administrative area of The Highland Council, which has its headquarters in Inverness.

The north is bounded by the coastal plains of the Moray and Beauly Firths, the edges of which are characterised by complex natural patterns, colours, smells and textures of coastal intertidal mudflats, with panoramic views across the sea. Inland, the district includes a rich variety of landscapes, where evidence of human presence generally diminishes progressively from the coast to the uplands, as the influence of nature becomes more pronounced.

The fertile and sheltered coastal edge is where settlement has been greatest. Inverness, the largest settlement, is situated here, at the point where the Great Glen meets the Moray Firth. Its setting is a distinctive feature; to the north, the city looks out over the expanse of the Moray Firth, whilst to the south it is sheltered by agricultural and wooded hills. The clear contrast between the character of the town’s historic centre and its rural surroundings has been fragmented by urban expansion on the higher ground to the south of the city spreading towards the Great Glen. However, the city still presents in a rural context from most directions.

Moving inland, the hills rise to form broad uplands which are divided by a number of sparsely settled straths and glens. These create green ribbons of pastoral land with meandering rivers and occasional lochs, which contrast with their upland backdrop. To the west, the uplands are rugged and contain some of the district's most spectacular scenery, which culminates in the sinuous steep-sided Glen Affric, within which is set great lochs and rivers, with lower slopes clothed in Caledonian pine forests flanked by high rugged mountain ranges. In contrast, to the east, lie the rounded Monadhliath hills, where immense tracts of open heather moorland create a strong sense of isolation and remoteness.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Geology

The geology of the Inverness area is defined by the Great Glen Fault, one of the most obvious physical features of Scotland, and visible clearly from space. This fault, a wrench- or tear-fault, was initiated 430 million to 400 million years ago. Lateral displacement along the fault may have been as much as tens of kilometres. Movement continued into early Tertiary times and minor earth tremors still occasionally occur. The Kessock Bridge, which spans the fault at Inverness, was designed to withstand earthquakes. The Great Glen itself was formed by glacial scouring along this fault line.

The Great Glen Fault separates two of the main divisions of Scottish geology: the Moine to the north-west and the Dalradian to the south-east. The Moine supergroup rocks created a rugged and complicated tapestry of glens and mountain ranges. The Dalradian supergroup underlies the Monadhliath plateau and helped to form its smoother, simpler shape. Both supergroups dominantly consist of metamorphosed sedimentary rocks; the Moine is the older of the two. South-east of Inverness there is an area of metasediments that are Moine-like and may be older than the surrounding Dalradian.

In contrast to the metamorphic rocks of most of the area, sedimentary rocks outcrop along stretches of the Great Glen Fault. West of the fault, and also south of Beauly and along the shores of the Beauly Firth, Lower Old Red Sandstones occur. They consist mostly of siltstones, mudstones and conglomerate. Middle Old Red Sandstones are found along parts of the eastern side of the Great Glen Fault, and along the southern coast of the Moray Firth, extending eastwards towards Nairn. They were probably deposited by rivers and alluvial fans; there are only occasional lacustrine sections relating to the large Lake Orcadie of Devonian times.

Granite, and some mafic, pluton intrusions (igneous rock that crystallised slowly from cooling magma at several kilometres beneath the Earth’s surface) around Loch Moy, Corrieyairack and the Monadhliath are more resistant to erosion and remain prominent, for example Carn Dearg, the highest point in the Monadhliath.

Glaciation and glacial deposition have been very influential in the Inverness area, with Devensian glaciation overwriting most of the traces of earlier glacial episodes. Ice flowed north-east along the glen, smoothing the Monadhliath plateaux and deepening the glens to the north. The Great Glen is a prime example of glacial erosion along a fault line. The steep sides and great volume of Loch Ness, and its lack of islands, demonstrate the power of the ice in sculpting the straight trench of the Great Glen.

Glacial depositional features are also notable. East of Inverness, the Kildrummie “Kames”, actually a series of eskers (narrow winding ridges deposited by meltwaters flowing in tunnels beneath the ice) extend north-east towards Nairn. The “kames” are designated as being of national importance, as are the eskers between Inverness and Dochgarroch, of which Tomnahurich, a well-wooded Victorian cemetery, is particularly prominent.

Post-glaciation sea level changes have meant that the coastline was approximately thirty metres above its present day level 14,000 years ago. The coastline has been near the present levels for approximately 10,000 years, due to the uplift caused by isostatic rebound (the rise of land masses after the lifting of huge ice sheets) roughly equalling increase in sea levels. River terraces and gravel floodplains, including under Inverness itself, have been incised by more recent river activity, often following ice flow patterns. The sediment from the river systems, and glacial sediment still being washed to the sea, has meant that the coast area of Inverness is still developing.

Landform

As noted in the previous section, the Great Glen divides the area into two areas of mountains. To the west, the uplands are rugged and divided into a series of mountain ranges by deep glens. In contrast, the eastern uplands are simpler, where the Monadhlaith hill range forms a large unbroken mass of high rolling moorlands and plateau.

The western ranges of rugged, irregular mountains are covered with many rocky outcrops and scattered glacial debris. These are severed by long, steep-sided glens created by glacial routes through weaker faults. The glens subdivide the mountains and are emphasised by their wooded nature, many with lochs winding along their base. The mountains’ rugged appearance and steep slopes as viewed from the glen bases, disguise the fact that the ranges are not high in comparison to the mountains further west or the Monadhlaiths to the east.

To the east, glaciers have carved a plateau of large scale, smooth, rounded hills, which are devoid of corries, creating a vast, almost featureless landscape. The mountains are deceptively high, sandwiched between the drama of the ridges to the west and the towering Cairngorm mountains to the east. The hills also form an important reference to many lower areas, their rounded forms and uniform landcover merging to form a simple backdrop to the adjacent straths and more distant lowlands.

The Great Glen is the district's most significant landform feature. It divides the Highlands in a straight line linking coast to coast and is highlighted by a chain of long, narrow lochs. The Glen owes its existence to a major fault running through the underlying schists, granites and sandstones of the area. This was later broadened and steepened by glacial action. The Great Glen has been an important channel for movement across the Highlands from prehistoric to modern times, enabling links to develop between regions around the Irish Sea to the Northern Isles. Communications were further strengthened by road and canal building in later centuries and human influences on the landscape through the glen illustrates its importance as a route.

Fitting within this underlying mountainous structure, there is a series of distinct smaller-scale landscapes, including coastal lowlands around Inverness and settled straths which occur across most of the area. The uplands and plateaux areas tend to form a simple backdrop to sheltered straths and glens. The journey inland, whether into the uplands or along the glens, illustrates this contrast well.

Climate: weather and seasons

In this northern latitude winters are characterised by long nights and short days. Summer days are long, with almost continuous light at the summer solstice. Spells of high pressure in the spring bring periods of clear visibility and blue skies.

There is often a marked difference in weather between the west and east of the district and between the mountains and lowlands. The west is subject to a series of Atlantic depressions which can cloak the mountains in the mists and rain clouds associated with high levels of relief rainfall. In contrast, the hills to the east are often clearer and drier, with the exception of days when haar (coastal fog) rolls in from the North Sea. On these days it is sometimes possible to emerge into bright sunshine only a few miles in from the coast, although at other times the haar can penetrate the Great Glen as far as Fort William. The climate changes with elevation, with the low lying coastal area bordering the Moray and Beauly Firths tending to have a milder and drier climate which is favourable for agriculture and settlement. Further inland the hills experience colder, wetter and windier conditions, which are partly responsible for the open heather moorland, severely wind cut trees and formation of peat bogs and the area's characteristic hill farming and sporting estate land uses.

The variability of the climate within the district means that seasons often seem to merge into one another. Winters in the coastal areas tend to be mild and often completely free of snow, whilst in the uplands, winters are often harsh with extremely cold temperatures and frequent snow cover which can persist into the summer. Spring is normally the season with least precipitation and May, being the driest month, is a good time of year to avoid midges in the western part of the district. This pattern has changed over the past decades with less frost and snow lying and a longer growing season. Precipitation is also increasing, especially in winter, with episodes of heavy rain rather than increased rainfall days. Changes of weather patterns may cause a wider range of crops to be grown as well altering trees and woodland species and structures due to weather, pathogens and actions taken to mitigate climate change.

Hydrology

Within the Inverness area water drains predominantly into the River Ness or north, directly into the Moray Firth. Loch Ness is the main loch in the area, and the largest by volume in the UK, following the base of the Great Glen from Fort Augustus to Loch Ness. Smaller upland lochs such as Loch Duntelchaig and Loch Mhor are dotted along the Monadhliath range to the east.

The Caledonian Canal is also a key feature in this area, linking the east and west coasts and running from Clachnaharry, west of Inverness, down the Great Glen to Corpach near Fort William. It is a superb example of Georgian engineering and when designed by Thomas Telford in 1803, the canal was the largest in the world. It was intended to be a goods route between the west and east of Scotland but in practice was too small for larger freight boats and the railway became more important.

Lower reaches of the River Ness are heavily modified for flood relief. Loch Ness, the River Ness and the canal are a focus for recreation and visitors to the area. In its middle reaches the river Nairn, which runs south-west to north-east parallel to the great Glen Fault, joining the sea at Nairn, is a good example of gorge formation.

Soils

There are four main types of soil across the Inverness area. The main lowland soil type is mineral podzol. Peat soils, peat, peaty gleys and peaty podzols cover the upland areas.

There are areas of immature soils where the slopes are steep along the Great Glen. These are interspersed with rocky outcrops. Their low levels of vegetation and loose structure means that they can become unstable in heavy rains, and erosion and landslides are not unlikely. Their unstable nature has impacts on transport links in the areas as these are concentrated on the lower glen sides. The immature soils are of little use for agriculture but may support some forestry on gentler slopes. The mineral podzols have some organic layers and are useful for mixed agriculture and arable with improvement, and also for maintaining native pinewoods and heather moorland. Some parts of the coastal plain are capable of producing a wide range of crops, in particular to the south and east of Inverness and around Beauly, because of the soil and other environmental characteristics.

The peaty soils are a valuable carbon store and are essential for maintaining upland habitats such as heather moorland and blanket bog. This is important for game management and supporting upland species such as hen harriers.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

History

The character of the landscape today has evolved from long-term human influence on the physical landscape. Archaeological excavation has confirmed that there was settlement in the area occupied by modern Inverness during the Mesolithic period, by around 5,000BC. However, it is likely that earlier evidence of settlement will be found in the future. The evidence from this period is sparse but what has been recorded suggests hunting and exploitation of coastal resources. With the exception of some possible mounds of discarded sea shells along the Moray Firth coastline, there is little evidence of these early inhabitants in the landscape today.

More substantial evidence for settlement during the Neolithic (or New Stone Age) period that started around 4000BC has been found to the south of Inverness. During this period people began to adopt what we would identify as agriculture and animal husbandry. Land suitable for cultivation would have become increasingly important, and this can be found on the fertile flood plains of the River Ness, and the light, free-draining soils of the hill foot slopes to the east and west.

The settlements from this period do not survive about ground but important monuments do survive, in particular, early types of burial cairns that have distinctive internal chambers. These tombs were clearly built to be prominent and to have important relationships with the surrounding landscape. For example, the chambered tomb at Leachkin, west of Inverness, is on a ridge with extensive views over the valley of the Ness and the Beauly Firth. We can still appreciate these important features of chambered tombs today.

Changes in technology and beliefs seem to have spread through the area from around 2,500BC and signify the start of the Bronze Age. This included the introduction of bronze and copper tools which may have made it easier to clear woodlands and cultivate small fields. Settlements may have spread further upslope as a result of population growth and/or climactic changes. Evidence for this survives in the low heather and grass-covered stone foundations of hut circles on the side slopes of the glens and higher moorland areas throughout the district such as Garbeg above Drumnadrochit. In arable areas remains of settlements are identified as cropmarks, but otherwise cannot be seen on the surface.

From around 2000BC there was also a notable change in the architecture and typical locations of burial cairns, which must reflect a fundamental shift in the beliefs of the people who built them. The area around the Moray Firth is known for a distinct group of around 50 cairns named after the most famous site at Clava.

These sites combine features of cairns and tombs with stone circles. The group at Clava is orientated in a line, mirroring the orientation of the surrounding Nairn Valley and aligning with the midwinter sunset. Unlike earlier tombs the cairns tend to be sited in areas suitable for settlement, with good land and access to water. These cairns were clearly built to have important relationships with the surrounding landscape, astronomical bodies and other monuments. This must reflect some of the important beliefs of the farming communities that built them and although few people appear to have been buried in them, they must have taken many to build and remained in use for around 1000 years. The tombs are an important part of the landscape character of the area and, along with other types of cairn or standing stones, they extend throughout the coastal plains and along the glens. Another fine example is located at Corrimony in Glen Urguhart.

Over the course of the first millennium BC there were further technological changes, such as the introduction of ironworking. There was also a marked deterioration in the climate, which got cooler and wetter, reaching a low point around 650BC. This is likely to have resulted in the abandonment of upland settlements and may have led to the movement of people to lower elevations with better soils. There may have been increased pressure for land and other resources. These changes are reflected by a change in the settlement pattern and, in particular, the building of defended sites such as hill forts, duns and crannogs (small island dwellings within lochs). The remains of the duns and hill forts are common on the steep high knolls which line the Great Glen, where they are characterised by low stone walls enclosing isolated rocky outcrops. Examples include Dun Deardil and Craig Phradraig on the edge of Inverness. The forts would have allowed the inhabitants to watch over and exert control over their surroundings and communication routes like the Great Glen. These important strategic relationships with the surrounding landscape can still be readily appreciated today through many views both to and from these forts.

The remains of crannogs are also evident in the landscape, where they form small, round islands in several lochs throughout the district. There is still much we have to learn about crannogs. Recent work in the Western Isles has found that some have origins in the Neolithic period, while we know that others were occupied right up until medieval times. They clearly had important relationships with the bodies of water they sit in and which would have provided some form of defence and a sense of separation.

The modern expansion of Inverness to the south has resulted in several extensive archaeological excavations. These have confirmed that the area around Inverness had at least one very important Iron Age settlement at Culduthel. This included two huge roundhouses, a host of smaller residences and one of the biggest concentrations of metalworking found in Scotland. The settlement was on a terrace and would have dominated the end of the Great Glen where it reached the fertile coastal plain. The size and elaborate architecture of the main residence, and the richness of the finds found with it, suggest that it was the residence of an important leader. Its occupation continued during Roman incursions, and the settlement would presumably have been an important centre for one of the tribes the Romans referred to as the Caledonians or Picts.

The Iron Age economy that supported the aristocracy that lived at Culduthel was founded on a mix of cultivation and rearing stock, especially cattle and sheep. Barley and wheat were the principal crops. There is likely to have been an established system with higher quality farmland on the coasts and lower glens cultivated and pastoral farming in the uplands and poorer land. This farming system is mirrored in the later medieval systems represented by upland shielings and cultivated furrows and ridges in the lowlands.

In the 6th Century AD the area enters the historic record. The site of the, much later, Castle Urquhart is the most likely candidate to have been the residence of a Pictish noble named Emchath, who was visited by St Columba during his mission to convert the area to Christianity. Columba also visited and converted the Pictish King Bridei and Bridei’s fort is commonly held to be Creag Phadrig, an Iron Age fort that was also occupied in Pictish times. While the exact location of these sites has not been confirmed it is clear that the north end of the Great Glen remained strategically important and a centre of power in the early medieval period. This is illustrated by these important forts and a number of characteristic Pictish symbol stones and crosses, which have been discovered at the head of the Great Glen, between Inverness and Dores. It is also illustrated by one of the best examples of an upstanding Pictish cemetery in Scotland, characterised by its square barrows or mounds at Garbeg on the north side of Glen Urquhart,

By the 11th Century, Scotland was a largely united land. In 1057, Malcom Canmore became king and started a dynasty that was to rule Scotland for two centuries. The rule of his son David I is commonly said to have been revolutionary because he seems to have been largely responsible for embedding the feudal system that extended throughout Europe across much of Scotland. This included the foundation of many burghs, including Inverness, and monasteries.

Inverness and its castle were the royal centre of power in the Highlands. The burgh was also an important market and seaport that exported goods from the surrounding countryside, including hides, wool, cured salmon and timber. By establishing a burgh, David intended to draw the area fully under his control and connect it to a trading network that extended into Europe.

The crown’s grip on power was reinforced by installing allies, mainly French and Anglo-French knights, as lords. Feudal lords controlled the country, and communication routes through it, from a series of distinctive fortifications that had little in common with the earlier duns. These are concentrated at important points, such as around Inverness. Some early castles were stone, like at Tom-a'-Caisteal to the west of Inverness, but most were earth and timber fortifications or mottes that can still be found in the valleys of the Nairn, Ness and Beauly Rivers. Other important castles were placed at strategic points in the glens, most famously Urquhart Castle, which controlled the junction of the Great Glen and Glen Urquhart.

Another important element of feudal society was the church, which controlled large areas of land, in particular through monasteries. There were few of these in the Highlands but one of the most important was Beauly Priory founded in 1230.

Away from burghs, castles and monasteries life in the countryside probably went on very much as before. Simple turf, timber and drystone houses were built in townships and the land was worked communally. The agricultural land of each township comprised infield plots, which were laid out in long narrow beds and cropped by individual families on a runrig system (rigs, narrow strips of cultivated land, were allocated to tenants on a rotational basis); and outfields which were worked and cropped jointly by the whole community. Beyond the township, cattle would be grazed on the hill land during summer months where some of the community would live alongside them in sheilings. The stone foundations of township houses, together with characteristic ridge and furrows of runrig, survive along the mid-slopes of many of the glens throughout the area. Surrounding them are often widespread enclosures defined by earth banks and drystone dykes. In upper glens the footings of shielings can survive, always by reasonable grazing and a source of water.

Along the coastal plain the townships may have developed into small settlements or have been succeeded by farms. Here modern cultivation will have removed most traces of earlier field systems and cultivation

Following Scotland’s forced incorporation into Cromwell’s Commonwealth in 1652 one of four citadels intended to pacify the country was built in Inverness. This citadel was a key part of a network of many smaller forts that extended along major communication routes including the Great Glen, with a fort also built at Fort William. The massive masonry walls were built from stone partly robbed from the area’s medieval religious buildings, including Beauly Priory. The citadel dwarfed other buildings in the town but brought some employment and increased trade to a burgh that had become less economically important over the later medieval and early post-medieval period.

After the unsuccessful Jacobite uprisings of 1715 and 1719, the British government wished to gain greater control over the Highlands. General Wade, Scotland's Commander in Chief, used soldiers to re-occupy some earlier forts, build some new forts, including Fort Augustus, and to construct a network of roads to allow troops to move easily between them. These roads were the first important step in bringing the Highlands in general, and the Inverness area in particular, under the firmer control of the British Government, and dealing with Jacobite unrest. Wade's roads were the first constructed roads of any length in the Highlands and formed the first planned post-Roman road system in Britain. They are clearly seen in the landscape of Inverness district today: for example the modern road along the east side of Loch Ness follows the same route, as do stretches of the A9 south from Inverness. Other sections remain well-preserved and are used more for recreation, like the route over the Monadhliath from Dalwhinnie to Fort Augustus, which is popular with cyclists. This includes the longest continuous stretch of military road built under the direction of Wade that remains substantially unaffected by modern alterations.

The final Jacobite uprising of 1745 culminated in the Battle of Culloden where, on 16th April 1746, an army of Jacobite clansmen attempted to prevent the British Army reaching Inverness and was defeated. Culloden marked not only the end of the rebellion, but some say also hastened the end of the traditional Highland way of life. The battle site, on an area of raised moor to the east of Inverness, has been altered since the 18th Century through agricultural improvement and commercial forestry. However, an area of moor at the centre of the battlefield has been preserved and was recently expanded through the removal of forestry. Settlement expansion by villages on the edge of Inverness has edged closer, although remains mostly unseen and it is still possible to appreciate the battlefield landscape and how it affected the famous events associated with the battle. A visitor centre provides explanation and context. The battlefield’s importance is recognised by its inclusion on the Inventory of Historic Battlefields, which means it is given special consideration in the planning system and in other land-use decision-making.

After Culloden, a number of possible factors, including the end of clan warfare and improvements in public health, linked to the advances of the Scottish Enlightenment, created a rapid increase in the Highland population. This, when combined with poor harvests, resulted in a number of years of famine. To address this problem, the administration of many of the large estates changed to the Crown and new tenancies were granted on the basis that land would be improved. In areas where former chiefs had become landlords, they were also put under new obligations to create new tenancies, with obligations upon their tenants to improve the land.

Initially, landowners broke up the lands of former townships to create moderately-sized farms, which they leased to farmers on condition that they introduce agricultural improvements. These improvements entailed levelling the old rigs and reorganising field systems, in order to introduce new crop rotations such as turnips and hay, needed to provide adequate feed for livestock over the winter. At the same time, the boggy floors of many straths were drained and converted into rich meadows, eliminating the need to move cattle to high ground during the summer months. As a result, over the second half of the 18th Century, the character of many of the straths and glens changed radically. The traditional land-use pattern of townships surrounded by cultivated fields and upland pastures and sheilings disappeared, to be replaced by a more regular pattern of pastoral and arable fields along the lower slopes, and large farm houses surrounded by pastoral meadows along the drained strath floors, as can be seen in Strathglass.

As townships were replaced by large farms, the grazing lands were given over to sheep and then deer. These changes went on in a piecemeal manner throughout the Inverness area, and perhaps as a result of this, the district escaped the large scale evictions which were common elsewhere in the Highlands and are collectively known as the Clearances. Yet the end result was very much the same, as much of the area's rural population migrated to the industrial towns of the south and further afield, or emigrated to a new life overseas.

By the turn of the 19th Century, as a consequence of war with France and the rapid growth of industrial towns in the south, the price of wool and mutton soared. Sheep farmers from the south were willing to pay higher rents than existing tenants. Landowners gradually raised the rents, forcing out their original tenants, many of whom migrated southwards. Areas like Farr Parish were cleared in 1807-1814. Few people remained; either relocated to poorer land, or employed shepherding or working the land directly for their new landlords. The remaining crofting settlements were put under further pressure by the arrival of potato blight in the 1840’s. The resulting crop failures and the stringent conditions attached to famine relief proved the final knell for many families and migration, often aided by landlords, led to further dereliction.

From the mid-19th Century onwards, another element entered into the economics of the local estates - their value as sporting properties. A general decline in sheep and wool prices coincided with the rise in the popularity of deer stalking. This at first led to the payment of high rents for shooting rights, and later to the acquisition of whole Highland estates. Although this happened throughout the Highlands, it was particularly prevalent in the western part of Inverness-shire. The rugged massif above Strathglass and Strathfarrar was cleared and lodge houses, such as Monar Lodge, were built to service this new industry. Deer forests needed even fewer hands than sheep farms, and many of the area's already small rural population joined the exodus south. Only a few stayed on to work as gamekeepers, or to take up employment in the new manor houses and hunting lodges.

Many of the original croft houses and lands of the clearances survive as evocative ruins or relict systems of dykes and cultivation. Some have been modernised and reoccupied as dwellings for people who no longer work on the land around them. Evidence of former townships is sometimes no more than the footing of a single house, or in some places a scatter of footings around which little fields can be traced; in other places buildings can survive to roof height and retain a sense that the inhabitants recently left. Sometimes these remains cover a broad area, giving clues to the existence of a sizeable township and associated lands. Examples like Alltnaba in Farr parish show up to four unroofed buildings plus evidence of field shapes and enclosures remaining around them. This is a common pattern across the area that adds much to its character.

By the end of the 19th Century, the agricultural landscape of the area with which we are familiar today had been largely formed. The agricultural lands on the slopes which overlook Inverness supported a mix of farmlands and policy woodlands, in contrast to the sporting estates of the uplands and hill farms of the more sheltered straths and glens.

The 19th Century was also marked by improvements in transport - firstly, with the construction of the Caledonian Canal, then by the general improvement of the major roads, and finally by the introduction of the railway. Improvements in transport were critical to improving access and communications with the rest of the country and increasing the number of visitors to the area.

The Caledonian Canal was constructed between 1803 and 1822, with the intention of allowing sailing ships (trading between the Baltic and America) and naval ships through the Great Glen, thereby avoiding the treacherous and longer route around the west coast and through the Pentland Firth. Unfortunately, the canal was built just before the era of larger steam powered ships, and did not become the international waterway it was intended to be. Nor did it stimulate industry along the Great Glen, although locally it did create employment during its construction period and was of value in carrying coal, building materials and fertiliser, for example, between Glasgow and Inverness. However, the canal has assumed a purpose beyond the vision of its builders. It survives as one of Scotland’s most impressive and scenic industrial monuments. It has survived as a tourist attraction longer than it was primarily used for commerce and first gained popularity after Queen Victoria took a trip along it in 1873. Today hundreds of thousands of visitors are attracted to the canal and the important sites it links. The entirety of the canal is protected as a scheduled monument.

The first surfaced roads were those constructed by General Wade in 1726, joining the garrisons at Inverness, Fort Augustus and Fort William with the south. Prior to this, roads through the county were generally unsurfaced and most heavy loads were transported by sea. In 1803, the Government set up a Parliamentary Commission for Highland roads, with a view to improving the economy by enhancing access. The Commission provided grants to landowners to upgrade roads. During the first half of the 19th Century, these roads grew to form a network of major and minor roads which, with the exception of some upgrading, had changed relatively little until 1982 when the opening of the Kessock Bridge and connected the Black Isle with Inverness. The route had previously been serviced by a ferry that was not suitable for significant amounts of traffic or freight. The ferry had been of such significance to the area that the Merkinch area is still referred as the Ferry thirty-five years after the service stopped. The bridge is also an important landmark in the sweeping views of the firth as visitors approach Inverness from the south.

The Inverness to Nairn railway was completed in 1854 and only eight years later the railway connected Inverness, via Nairn and Aviemore, to the south. By 1863, there were through trains to London. Although Inverness had been important as a wholesale supplier to the surrounding area for many years due to its harbour, this role was reinforced by rail connections. The railway also led to an increase in tourism and associated facilities, such as hotels, tour operators, specialist shops and services.

Depopulation remained a very serious problem at the end of the 19th Century and the early 20th Century. The population of the Highlands is currently increasing, and the Inverness area in particular has seen significant growth from the late 20th Century. However, this has not matched the increase in the rest of the UK as a whole and the area still seems sparsely populated compared to other regions.

During the 20th Century, the economy of Inverness and surroundings has generally followed wider Highland trends. The first half of the century saw a slow decline. In rural areas, the sporting estates reduced in popularity and the role of Inverness as a fishing port also declined. This followed the construction of a sheltered harbour at Buckie, fifty miles nearer to the main fishing grounds. Perhaps the most ironic cause of decline over this period was that brought about by improvements in transport during the previous century, particularly road and rail. Although initially these improvements had opened up trade with the south, they later brought competition from enterprises serving the larger markets in the south resulting in the decline and eventual loss of several locally based companies.

There were several new developments in forestry, hydroelectricity, road and bridge building, urban expansion, housing and industry over the 20th Century which had a significant effect on the character of the district. Early in the 21st Century, wind energy and further urban expansion are changing the landscape. Inverness has experienced rapid urban expansion over the past twenty years and demand for housing, although slowing, is still high. Expansion has occurred, mainly to the east, providing almost continuous settlement through to Culloden and Smithton, and on either side of the River Ness towards Loch Ness. The new houses, roads, bridges and other infrastructure have created an area with a more suburban character, although there are few places in the city from where the surrounding coast and countryside are not visible. Wind farms have been built in the Monadhliath Mountains, such as those at Farr and Moy, which have introduced a man-made element to the otherwise perceived wild uplands and can be seen from neighbouring upland areas.

Tourism has become an increasingly important industry for the Inverness region with Inverness marketing itself as the hub of the Highlands, and the airport and port welcoming passengers to the area. This is especially noticeable along the west bank of Loch Ness where the road has been redesigned with stopping places and attractions, which can make the journey very slow in the summer months. Adventure attractions and long distance routes, such as the Great Glen Canoe Trail and Great Glen Way, open up the area to a range of visitors.

Landcover

Overview

The Inverness district has a mix of land-cover dictated by the geography of the area. The peat-dominated soil types of the upland areas lead to a dominance of boggy moorland, classified as mires, bogs and fens in the EUNIS landcover Scotland maps, edged by heathland and scrub where drainage is better. Cultivated and improved agricultural land is concentrated in strath floors and lowland areas nearer the coast with woodland, native and planted forest, a strong feature of the mid slopes between. Small areas of montane habitats top the peaks and highest areas of the plateau.

Forest and woodland

Commercial forests are characteristic of many upland areas throughout the district. The poorer soil in upland areas means that it is one of the few profitable crops. The sides of the Great Glen sides are generally too steep and rocky for agriculture. Originally, these slopes would have supported native Caledonian pine woodlands which were cleared over the centuries to provide timber for many uses: from constructing Iron Age crannogs, to building the Caledonian Canal. In more recent years, the character of these woodlands has changed, as the more uniform character of coniferous forestry has gradually dominated the glen sides. Woodland and forest ring the slopes above Inverness and adjoining settlements with agricultural land and heathland sandwiched between. It follows the loch south in a continuous strip of varying widths, mostly native along the loch edge but with conifer forests extending behind.

Other glens and straths support intricate patterns of pasture, small, native, woodlands, meandering rivers and occasional lochs. On the gently rolling lowlands which overlook the Moray and Beauly Firths, a long continuity of settlement has created a diverse landscape of woodlands, farmland, settlements and access routes, with a mixed pattern of enclosed spaces and open areas. This has been affected by the extension of settlement along the A96 corridor where the area has taken on a more suburban character, with less distinction between Inverness and satellite settlements. Woodland is still present but is more fragmented than before. It serves an increasingly important recreational function for the surrounding settlements.

Moorlands

Upland mountain habitats comprise heather, rough grassland and bog, with some birch and Caledonian pine woods linking with more extensive pinewoods in the glens. The quality of soil in these areas means that it is not suitable for modern agriculture apart from rough grazing. However, large areas are used for rearing of game and field sports. Without management by grazing and burning, many of these areas would progress through succession to climax communities of birch and Caledonian pine woodland. The lower edges of the Monadhliaths and many of the hills to the west of Loch Ness are covered by heathland with the moorland becoming wetter with mires, bogs and fens on the higher parts of the plateau. There are few areas of montane habitat in the area outwith the Monadhliath plateau, where it is more common towards the south of the plateau.

Grassland

Agricultural grassland is found along the strath floors and in the lower land around Inverness. This is predominantly improved and semi improved grassland for grazing with low levels of mixed agriculture. It is interspersed with scattered steadings. More intensive pastoral agriculture, such pig rearing and dairy, is restricted to the coastal areas.

Land-use

This area shows a wide diversity of land use for the Highlands. Inverness is the largest settlement in the Highlands with smaller satellite commuter towns, linked infrastructure and industry around its periphery. This includes upgraded roads, an airport, university campus, shopping centres and industrial estates on the edges of Inverness and at Dalcross. Agriculture is predominately pastoral but there are mixed farming and cereals along the coast, and forage crops grown on the strath floors. Upland areas are used for game and rough grazing as well as being an attraction for visitors. Renewable energy generation through hydroelectric and wind turbines is also a common upland land use in this area.

Transport

The roads in the Inverness area are focussed on the glen floors with few and more minor roads crossing higher ground. The key road routes are the A9, A86 and A82. Transport improvements linked to the A9, A96 and the Inverness to Aberdeen rail line are proposed. A new road crossing over the River Ness in Inverness reduces pressure on the existing town centre river and canal crossings, redirecting heavy vehicles from the town centre. It also extends the urban edge of Inverness to the south.

The expansion of Inverness Airport, to the east of Inverness, has attracted more visitors to the area as well as the development of an industrial area on previously agricultural land between the A9 and Ardersier. This is likely to be linked to the creation of new settlement, including the new planned town of Tornagrain, and a railway station built to service this.

Inverness port attracts cruise liners and cargoes such as renewable energy machinery and timber. Oil rigs, and related tankers, are a common sight in the Firth beyond Inverness but dock further north at Invergordon or Nigg in the Cromarty Firth.

The railway is still well-used in the region to connect Inverness to the central belt and the east coast. The lines west and north are used by residents and visitors to the area as transport and to experience the spectacular scenery.

Agriculture

There is little high quality agricultural land in the Inverness area, although there is a small area along the firth and south west towards the Great Glen that is capable of maintaining crops such as cereals and potatoes. Even in these areas, agriculture is more likely to be mixed and pastoral. Closer to the firth, pigs and dairy herds are not uncommon but the area is more used for cattle and sheep grazing. Within the limited steep valleys of the glens, improved grassland supports mostly cattle and sheep farming. Above the glens land is mostly unimproved and only suitable for rough grazing, declining in quality with altitude. Across the wider Highland Council area as a whole, cattle and sheep farming and general cropping and forage is the most common form of farming.

Crofting is present in a number of areas across the area. Crofts generally comprise landholdings with buildings present on better quality, improved grassland and poorer mixed agricultural land and grazing rights on low quality hill grazing. They are usually small landholdings aimed at subsistence farming, generally run in tandem with another occupation. Many are tenanted, but increasing numbers are owner-occupied or community owned. In occupying a croft there are duties required to maintain the land - crofters should be resident on or close to their croft, and cultivate and maintain their croft. There are also restrictions on changes of use.

At present, there are several financial incentives and grants available from various organisations which support agricultural diversification within crofting areas. These incentives tend to encourage the protection of natural habitats such as scrub, bogland and wetlands, and the creation of woodlands and encouragement of countryside access for recreation.

Hill farming has helped to shape the landscape. It maintains moorland and upland grassland which would otherwise be colonised by trees, thus promoting moorland habitats. Silage and hay production emphasise the seasonal nature of arable farming and provide nesting opportunities for birds like corncrakes. However this interdependency means that changes in stocking levels and practices can have an effect on both. Grants and incentives are a strong force in landscape change in the area. Game, particularly deer, is common in higher areas, especially areas of Rugged Massif, and grazing controls the vegetation present in many areas.

Commercial Forestry

Forests are characteristic of several upland areas throughout the area. Many of these date back to the early years of the Forestry Commission which, between 1920 and 1950, purchased private estate land and planted several large conifer forests. Over this period, the diverse mix of native oak, pine, ash, birch and hazel which covered many of the steep rocky hillsides increasingly disappeared to be replaced by the uniform, dark green colour of commercial forests, which bore little relationship to the underlying landform. Many of these forests are now being felled and restructured. Their management is no longer solely focussed on tree production and, instead, encourages the regeneration of native woodland and use for recreation. Woodland like those at Culloden and Daviot are now heavily used by local residents, with others along Loch Ness being marketed as visitor attractions. Concerns about the effects of climate change and pathogens, as well as grants promoting access and native species, has reduced the reliance on monoculture and clear felling and a more mixed approach is becoming common, even within private forest estates.

Hydro-electricity

Between 1948 and 1970, the building of hydroelectric schemes and associated new and improved roads created considerable employment throughout the Highlands, and the upland areas around Inverness in particular. A number of dams and reservoirs were constructed in many of the area's remote glens, such as Glen Strathfarrar and Glencannich. The dams tended to be constructed as simple concrete utilitarian structures with associated buildings usually designed and constructed from local materials. The pronounced draw-down scars (when the water level drops below the maximum level) can isolate the reservoirs from their surrounding landscape at certain times. The reservoirs often act as a focus for outdoor recreation, with associated car parks at the dams.

Construction and upgrading of the original hydro schemes also required infrastructure such as tracks and buildings which have a varying level of impact on the landscape. Early schemes were designed to show the buildings function with grand art deco inspired pump rooms; more recently installed schemes have been more discrete.

Hydroelectric schemes across the area vary from large schemes like Fasnakyle, (above Cannich) which produces output equivalent to 50% of the Highland Council household consumption, to micro and medium schemes, of which there are a number under construction or approved.

The Great Glen Scheme has five power stations which have an annual output equivalent to the electricity consumption of all the households in The Highland Council region. Micro schemes are typically used to provide power to single or clusters of properties and are often ‘run of river’ schemes with little storage required.

Wind energy

Recent large scale commercial windfarms, have introduced significant features into the rolling upland landscapes in the Inverness area. Projects include Moy and Farr within the Monadhliath; new developments like Dunmaglass and Balmacaan will add to the visibility across the area. The restricted nature of the landscape of the Great Glen means that glimpses are fleeting from within it; however from the higher plateau there is an increasing visibility. The lack of other landscape or manmade features in the vicinity of the wind farms makes them a strong component of the landscape.

Mineral extraction

Mineral extraction in the Inverness area is limited, with a small number of active sand and gravel quarries, peat cutting and one quarry cutting igneous and metamorphic rock for building materials near Daviot. The quarry is visible as vehicles approach form the south on the A9.

Tourism and leisure

The distinctive scenery of the Inverness area, as well as the local attractions and its rich cultural associations, attract a significant number of tourists. The scenery and landscape is the most popular reason for visiting the Highlands as a whole. In the 2017 Visit Scotland’s Visitor Survey Regional Summary, 87% of respondents mention it, with the history and culture also in the top three reasons. Inverness area is a focus for these visitors due to its services and role as a transport hub for the area. 42% of visitors to the Highlands say they ‘visited cities’ and, as the largest settlement in the area, it is highly likely Inverness is the city referred to. During the seasonal influx of visitors in the summer months the area bustles with tourists, hill walkers and mountain climbers, which leads to some congestion on roads, and generally increases the level of activity and commerce. The introduction of the “North Coast 500” route, which starts and ends in Inverness and follows the whole coastline to the north, has compounded this effect.

Inverness acts as a base for tourists to explore other areas of scenic and historic interest further afield. The industry expanded rapidly during the late 20th Century, and continues to expand steadily. Inverness is extremely busy at peak times, especially as the summer season sees influxes of cruise ship passengers daily to the highland capital and its tourist attractions. This is a visitor type that has increased greatly in recent times.

The Caledonian Canal is a popular tourist attraction. Many motor cruisers and yachts sail along the canal and Loch Ness during the summer months. However, the immense size of the loch means that it does not appear crowded. The canals, lochs and their gates also attract interest as working pieces of industrial heritage, particularly at Neptune’s Staircase at Fort Augustus, where the flight of five lochs and passage of boats forms the centre of attraction.

Other historic sites make the district’s tourist offering one of the strongest in Scotland. These include impressive castles at Urquhart, which draws over half a million visitors a year, and Cawdor. The Culloden Battlefield Visitor Centre and Clava Cairns have seen very steep recent rises in visitor numbers, largely driven by an association with the popular ‘Outlander’ television series. These sites, and the roads around them, can get very crowded.

Settlement

The intrinsic landscape character of the area around Inverness reflects a close relationship between the area’s natural assets and the people that have managed and shaped them. Patterns of settlement and agriculture reflect the strong, historical relationship between people and land, and are often responsible for the diverse range of habitats, landscapes and cultural features found in the district.

Urban expansion has increased around Inverness, the Black Isle and the Great Glen in the last few decades, resulting from improved transport connections, and the growth of tourism and service industries. The Inverness area has experienced recent rapid urban expansion of around 15% since 2001. This has been focussed on the city itself, extending south past early expansion in the 1950’s and 60’s towards Loch Ness and eastwards where the villages of Culloden and Smithton are now experienced in an almost contiguous manner. New settlements along the A96, such as at Tornagrain, will continue this band of development. This expansion has also been reflected in the villages within commuting distance of Inverness such as Kiltarlity, Beauly and Kirkhill. This expansion has fragmented the distinction between rural and urban patterns around Inverness. The Inverness area is identified as a growth area, stretching down the coast eastwards towards Moray, in the Local Development Plan. The expansion of the city has been determined by the physical geography of the area and steep slopes to the south and west and the firth are the first determinants, coupled with flood plains for the Ness and the canal. The city is planned to fill in the expansion to the south on the slopes above the river and growth at Culloden.

Generally, the expansion of settlements has brought with it an influx of standardised developments which do not reflect the character of the area, tending to create a more homogeneous landscape which dilutes the 'sense of place'. The edges of Inverness have been characterised by the introduction of out-of-town shopping and suburban housing developments which have a national, rather than local character. Similarly, the expansion of smaller settlements has often seen the introduction of suburban house types and servicing elements which has tended to blur the distinction between town and rural settlements, diminishing the distinctive character of both.

Protected landscapes

Glen Strathfarrar and Glen Affric both have National Scenic Area designations, and Glen Affric is also designated a National Nature Reserve, being one of the best examples of remaining Caledonian Forest that once covered much of Scotland.

Both shores of the Great Glen, from just north of Dores and stretching to Fort Augustus, have local landscape designation as a Special Landscape Area by the Highland Council. This area surrounds and includes Loch Ness from Lochend in the north to Fort Augustus in the south. It includes the bounding hill slopes on the loch’s western and eastern shores, the prominent hill Meall Fuarmhonaidh, which lies between Drumnadrochit and Invermoriston, and the elevated moorland and agricultural interior plateau which contains Lochs Ashie, Duntelchaig, and Ruthven. The landscape of the area is focussed on Loch Ness and how it dominates its setting.

Culloden Muir is designated a Conservation Area for its special historic interest and is included on the Inventory of Historic Battlefields. The area designated as a Conservation Area encompasses the land associated with the battle and was extended to make sure this area was fully enclosed. It also reflects the remains of prehistoric activity at Clava and the development of the railway, particularly the Nairn Viaduct, all of which help to illustrate how the culture of the area has evolved. This means that the character of the landscape and its historical context have been considered within the conservation area boundaries.

Drynachen, Lochindorb and Dava Moor Special Landscape Area covers most of the higher moorland which separates the Cawdor-Ferness-Beachans area of Nairn district from Strath Spey to the south and the route of the A9 to the west. It incorporates the continuous moors of Drynachan, Lochindorb and Dava and extends from Carn nan Tri-tighearnan in the west to Lang Hill and Carn Kitty in the east. This means that the westerly edge of this designation is included in the Inverness area. The landscape is comprised of high rolling moorland with elevated blanket bog and heather moorland with muirburn patterns. There is some scattered pine-birch woodland but the open moorland landscape is dominated by the unbroken skylines. This area is not large scale or highly wild but its location between settlements and the experience of travelling through it means that the moorland has a high value to the area’s character.

The Monadhliath Wild Land Area has been identified as an area of high wildness. Although not a designation, this recognition is taken into account when considering development proposals in this area.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES

Gaelic in the Landscape

Although no longer commonly spoken, Gaelic was widespread in the Highlands until the last 150 years. Recently there has been a growing interest in the Gaelic culture, with an increased popularity of Gaelic literature, prose, television and contemporary music. The promotion of Gaelic as an intrinsic cultural characteristic of the region has been adopted by the Gael and visitor alike. Ironically some may see the strong traditional culture as a reaction against the increase in incomers; however, this cultural strength is itself an attraction for visitors.

The native language has many descriptive words for landscape features suggesting a respect for the character and grandeur of the surroundings. This retained interest in the Gaelic language exists despite the attempts in the past to remove the people from the land and modern working practices that mean fewer people earn their living from the land. Land use and income have moved away from practices that relate directly to the landscape and have come to rely more and more on the service and tourism industry. The language is one tangible link, not only to the cultural heritage, but also by its richness to the land itself.

Around Inverness the Gaelic names are descriptive and give a sense of the type, shape, colour and size of a feature. Inverness itself, Inbhir Nis, describes its location at the mouth of the Ness River. The various names for mountain shape, for example Aonach is a steep ridge, sgurr is a steep peak, and meal describes a rounded hill or mountain. Meall Fuar-Mhonaidh, describes the mound of cold (or empty) moor. Monadhliath (Am Monadh Liath) means the grey moor. Other terms such as coire (corrie) and loch are also common features. Inverness-shire marks the westerly edge of Scots in the Highlands with words such as brae (St Stephen’s Brae) and auld (Auldcastle Road). These are concentrated around the city where Scots influences were stronger. Some Norse derived place names exist, including firth, derived from fjord, the Moray Firth being the northern focus of this area. It is unlikely that much Norse influence is found further inland.

Perception of the landscape

The Great Glen’s towering wooded side slopes and long linear loch create a sequence of experiences, as uninterrupted views along the length of the glen alternate with more contained views focusing on the opposite shore.

The general ruggedness of the mountains to the west of the Great Glen, combined with a covering of rocky heather moorland on the mid and lower slopes, and few signs of human activity, creates a strong sense of remoteness which is particularly pronounced within the interior. Due to the nature of the landscape to the west of the Great Glen, the experience of wildness can feel relatively contained.

East of the Great Glen, the Monadhliaths range of massive rounded hills and plateaux is awe-inspiring in its simplicity, openness and immense scale, and offer panoramic views to distant mountain ranges. They contain an extensive, simple interior, largely uninhabited, with few human structures, excepting occasional unoccupied bothies and shielings. Coupled with an absence of access tracks, these factors contribute to a perceived ‘emptiness’ and a strong sense of naturalness, remoteness and sanctuary. Unoccupied buildings and small settlements often evoke a sense of abandonment. Long narrow glens cutting into the hill and plateau edges are remote but facilitate access. Slopes screen views but create shelter and a sense of sanctuary.

The sheltered straths and glens are highlighted by their brighter colours and more intricate patterns of pasture, small woodlands, meandering rivers and occasional lochs. The gently rolling lowlands have a diverse landscape, with a mixed balanced pattern of enclosed spaces and open areas. Reservoirs often appear as elements with distinctly human influence within the glens which otherwise have intrinsic remote qualities.

The mix of mountains, glens and coastlands within the area provides a variety of experiences in different seasons and weather conditions. The northern latitude, and coastal situation of parts of the area, also results in striking light conditions and skies at certain times which change dramatically throughout the year. In the short winter the low sun angle emphasises the rolling landforms and the rugged textures of the hills and moorlands. In contrast, summer days are long, with almost continuous light at the summer solstice. The landscape is often seen at its most striking in the spring and early summer, when spells of high pressure bring periods of clear visibility and blue skies that reveal the true spectacle of the district's landscape. This also emphasises the contrasting relationships between the settled lowlands and glens and their more rugged and uninhabited mountain backdrops. The clear light is particularly acute in coastal areas around the firths where the intense brightness is emphasised by reflections from the water's surface and wet sand. The autumn is typically distinguished by the sound of bellowing stags and rich purples of the heather moorlands in the hills, and the grasses gradually turning russet mark the approach of winter.

Cultural Impact of the Inverness area

The Inverness area has a rich history and mythology attracting visitors and giving depth to the way the landscape is viewed. The stories around the Loch Ness monster add a fun edge to visitors experience of visiting the loch and have been the subject of films such as Loch Ness (1983) and The Water Horse (2007), which were both filmed here and not only promote the popular myth but showcase the landscape. Other poetry and paintings celebrate the scenic attractions of the area, especially Robert Burns’ dramatic description of the Falls of Foyers, ‘Lines on the Fall of Foyers’, and Dorothea Primrose Campbell’s romanticised description of the area along the River Ness ‘To Eliza L. G. Sutherland’ (1810).

The Battle of Culloden promotes a feeling of wildness in the area and poetry like ‘Culloden Moor (Seen in Autumn Rain)’, written by Alice MacDonell at the end of the 19th Century, and ‘Culloden’ by Andrew Lang, describe the bleakness of the moor, linking it to the dramatic history.

Contemporary perceptions of Culloden are often evocative, invoking wider associations with the clearances and a related sense of loss. An international audience recognises the significance of Culloden and many of them might feel a strong connection to the Highlands because their ancestors were part of the Scottish diaspora. Awareness of Culloden, and the history of the Highlands more generally, continues to grow through popular contemporary depictions, most recently in the ‘Outlander’ television series.

The history of battles and the Scottish clans adds colour to the experience, and there is a strong trend for visitors, especially from north America, Australia and New Zealand, looking for their links with the area. This is now known as genealogy tourism. 23% of long haul visitors cite their Scottish ancestry as a reason for visiting Scotland as a whole. Inverness is the location of the Highland Record Centre which makes it a popular destination for these trips.

Document downloads

Contact

If you have any comments, please email