Landscape Character Assessment: Cairngorms - Landscape Evolution and Influences

A PDF version of this document is available at the foot of the webpage

This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority or national park area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset.

The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. The documents have been revised because feedback suggested they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced.

The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority.

The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. Some content variation still remains as it has not been possible to completely re-write the documents.

The new documents include photographs. It has not been possible to update the maps or sketches from the original LCAs, but these are still available, in the archived original reports, from the NatureScot Information Library. Additional information can be obtained from the websites of:

- British Geological Survey www.bgs.ac.uk/

- Historic Environment Scotland (Historic Land use Assessment, Gardens and Designed Landscapes, historic features and their designations, etc). www.historicenvironment.scot/

- NatureScot website especially Landforms and Geology (more specifically the “Landscape Fashioned by Geology” series) and About Scotland’s Landscapes soils; wild land; landscape character; designations etc.) www.nature.scot

- The relevant local authority, which will have information on landscape policies, etc.

- Cairngorms National Park Authority. www.cairngorms.co.uk

The content of this document is based on the background chapter information in “Nature Scot Review 75 - Cairngorms Landscape Assessment”, 1996, Turnbull Jeffrey Partnership.

If you have any comments, please email [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

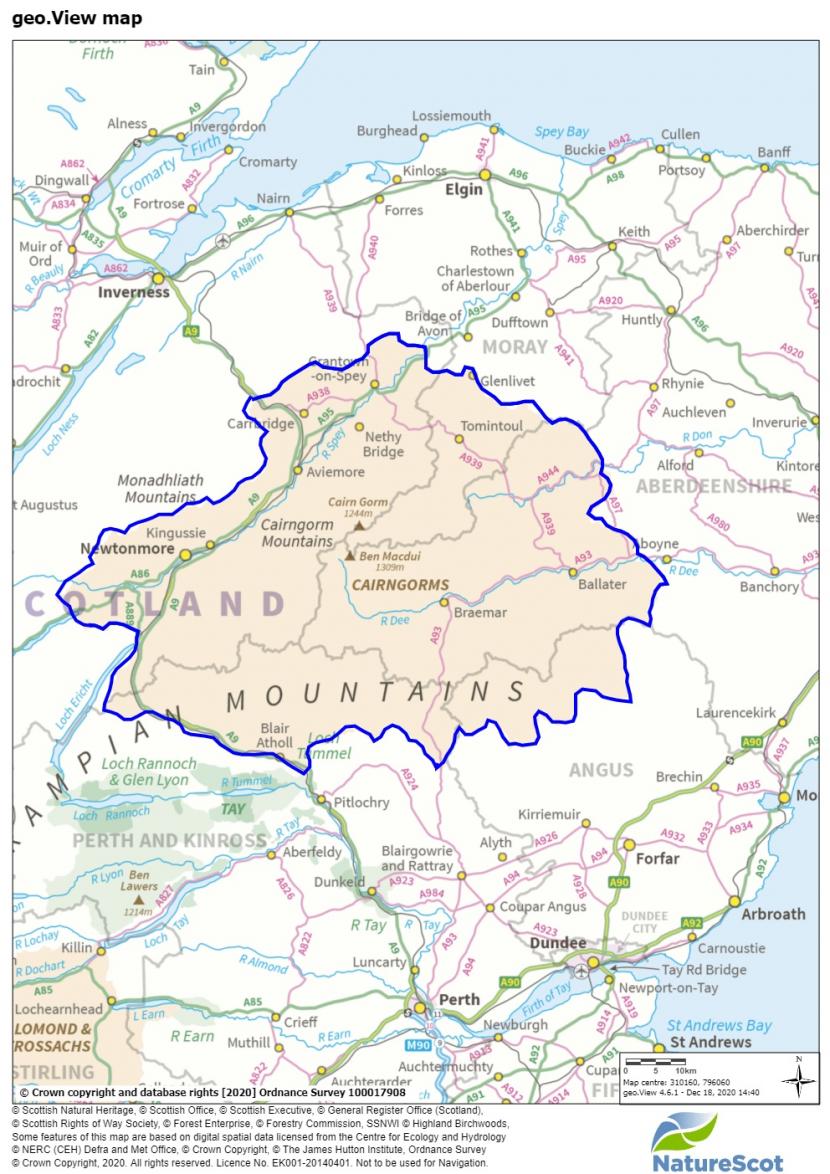

This information covers the Cairngorms National Park area, located in the Scottish Highlands west of Aberdeen, north of Pitlochry and south-east of Inverness. Forming the largest National Park in the UK, it covers 4,528 km2, about 6% of Scotland’s land area and spans the boundaries of 5 local authority areas – Angus, Perth and Kinross, Aberdeenshire, Moray and Highland. Magnificent mountains tower over moorland, forest and straths. The Cairngorm Plateau is the highest and has the most extensive range of arctic mountain landscape in the British Isles. There is a vastness of space, scale and height, and a strong juxtaposition of different landscapes

The high massif of the Cairngorms forms the core of the area, surrounded by extensive lower hill ranges and dissected by the broad straths of the Dee and Spey. It is a landscape of many contrasts, where the influence of humans on the landscape is clearly evident in the settled and farmed straths and glens, but where, for example in the sub-arctic environment of the Cairngorms massif, natural processes are dominant. The area has a rich natural heritage with rivers and wetlands, birch and native pine woodlands, heather moor and the more rarefied arctic vegetation of the high mountains contributing to the character of the landscape. Human-made elements of the landscape are also important and the farmland of the straths and hills, estate policies and cultural heritage of the area are distinctive. The scenery of the Cairngorms has long been celebrated, with tourism being a feature mainly from the 19th Century onwards.

The area was designated a National Park by the Scottish Parliament in 2003, under the National Parks (Scotland) Act because of its outstanding national importance for its natural and cultural heritage, distinctive character and coherent identity. The designation aims to conserve and enhance the natural and cultural heritage of the area, promote sustainable use of the natural resources, promote understanding and enjoyment (including enjoyment in the form of recreation) of the special qualities of the area by the public, and promote sustainable economic and social development of the area’s communities. The Park was extended in 2010 to take in Blair Atholl and Spittal of Glenshee.

About 19,000 people live in the Park, many in the main settlements of Aviemore, Ballater, Grantown on Spey, Kingussie and Newtonmore, but also a large number in dispersed rural communities. Settlement is frequently within the main river valleys. Outside settlements most of the land is farmland, moorland, forestry, woodland and mountains.

1.8 million people visit each year. The economy of the area is heavily reliant on sectors, particularly tourism (30% of economy and 43% of employment). People come to appreciate the outstanding landscapes, wildlife, culture, tranquillity and huge range of activities, including hillwalking, mountaineering, cycling, paddle sports and skiing. The area has become renowned for its wide range of outdoor recreation opportunities. The attractiveness of the area for a wide variety of recreational pursuits has resulted in significant increases in the numbers of visitors to the area in recent years, with visitor pressure affecting landscape character in some areas. Changes in land use and management have also affected the landscape character of the area, and there is continuing pressure for change.

The landscapes of the Cairngorms are one of the Park’s most valuable assets, underpinning its character, designations and the appeal of the area as a place to visit, live and invest. The Cairngorms and Deeside and Lochnagar, are designated National Scenic Areas in recognition of their nationally outstanding scenic value and beauty. The experience of large scale wildness is particularly distinctive in UK terms; Wild Land Areas cover nearly half of the area. The National Park has 55 Munros (the 282 mountains over 3,000 feet, or 914 metres) including four of the UK’s highest mountains and five of Scotland’s highest. The National Park contains the largest continuous area of natural and semi-natural woodlands in the UK.

Within the area there are ten places identified in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes, grounds which were consciously laid out for artistic effect. As well as being nationally designated they are an important element of Scotland’s historic environment and landscape and often incorporate designed views and wider landscapes as part of their setting.

Over half of the Park is designated as being of European importance for nature through the Natura network and over a quarter of the country’s rare and threatened species are found here. Almost 55% of the Park area is covered by formal natural heritage designations, with 19 Areas of Conservation, 12 Special Protection Areas and 46 Sites of Special Scientific Interest. There are also 9 National Nature Reserves.

PHYSICAL INFLUENCES

Introduction

The Cairngorms area includes one of the most notable mountain environments in Britain, comprising broad granite plateaux, with steep-sided glens and corries, surrounded by extensive uplands, and the straths and glens which cut into them. The area is home to one third of UK land over 600 metres. The diverse vegetation includes semi-natural woodlands, plantations and moorland and the farmland and wetlands within the straths.

The landscape we see today, throughout the study area, has evolved over a prolonged period of time as a result of the complex interaction of various physical and human processes, some of which still continue. Geological and geomorphological processes have played a dominant role in shaping the landscape. Subsequent weathering has led to the development of particular soil characteristics, which in turn have influenced vegetation patterns. People have further altered the landscape through settlement, farming, forest clearance and tree planting, along with other activities and developments. Throughout the area, on-going geomorphological activity and changes in land use and land management, illustrates the dynamic and continually evolving character of the landscape.

Geology, Topography and Hydrology

Geological evidence, although incomplete, indicates that the evolution of the Cairngorms has been a long and varied process. Between approximately 800-600 million years ago, the geological foundations of the Grampian Highlands were created, with the laying down of great thicknesses of sediments on the floor of an ancient sea. Subsequently, great movements of the earth's crust with associated heat and pressure metamorphosed these sediments and folded them into 'Alpine scale' mountains. At the same time, large quantities of granite melt, contributed to the building of the mountains by rising through the crust and solidifying within a few kilometres of the earth's surface. Over many millions of years, erosion and weathering wore down the mountains to their foundations, revealing granite cores from beneath the encircling metamorphosed rocks.

The central Cairngorm massif forms the largest homogenous granite mass in Britain. A series of these granite masses, surrounded by bands of metamorphic rocks, occurs throughout the National Park. The variety of rocks occurring in the area gives rise to different landscape characteristics. Where not modified by intense glacial erosion, granite landscapes are characterised by rounded, smooth landforms, with extensive boulder fields which are particularly prevalent throughout the Cairngorm – Ben Macdui - Braeriach plateau and the Lochnagar area. Granite landscapes also tend to be less fertile than those forming on underlying metamorphosed rocks, and therefore have a more barren character, whereas the mountains comprising metamorphosed rocks are characterised by ‘knobbly’ landform patterns, exemplified by the eastern edge of the Monadliaths and the Ardverikie area. These areas are also influenced by the dominant geological pattern, known as the Caledonian trend, giving them a distinct north-east to south-west grain. Within the areas of schist, small pockets of limestone, such as at Inchrory in Glen Avon, produce a contrast through and scree colour within the surrounding landscape.

During the Tertiary, commencing 65 million years ago, rivers cut into the granite mass creating a network of steep valleys. The climate was considerably warmer than it is today, which assisted the chemical weathering of the bedrock. Such weathering was more intense where the jointing in the rocks was closely spaced. The weathered material was subsequently removed by glacial and periglacial processes during the succeeding Quaternary, leaving the more massive, less weathered rock outcrops upstanding as tors. Such features are particularly distinctive on the summits and slopes to the north and east of the central mountain massif, for example on Ben Avon and Beinn Mheadhoin.

Before the onset of glaciation, the landscape would have comprised broad plateau surfaces, rolling hills and shallow river valleys, with extensive occurrence of deeply weathered bedrock. Many of these features survive today on a scale that is exceptional in glaciated mountains of Northern Europe, suggesting that glaciation resulted in minimal modification of the mountain plateaux compared with the effect it had on the surrounding glens and straths.

The Influence of Ice

About 2.5 million years ago, there was a major cooling of the climate, heralding the onset of the Ice Age or Quaternary Period. Glaciers formed over the upland areas as snows built up, extending slowly, out into the lowlands to create huge ice sheets. The Ice Age consisted of many glacial periods interspersed by warmer interglacial periods; many of the features of glacial erosion therefore reflect the imprint of successive glaciations.

The intensity of glacial erosion was much more significant in the areas surrounding the plateaux, producing a series of deeply eroded glens or glacial troughs which cut into and through the gently rolling pre-glacial landscape, exploiting inherent weakness in the underlying rock structure. Here the ice was thicker and faster flowing, making it very effective at eroding the granite. In places such as the Lairig Ghru, the ice carved through original watersheds to create spectacular glacial breaches, as well as creating truncated spurs where glens were straightened. These glacial breaches tend to cut across pre-glacial valleys such as the Dee and Geldie. Rivers like the Feshie were also diverted as the ice created new, or modified existing landform patterns.

In the areas surrounding the central plateaux, glacial action tended to accentuate weakness in the more complex schist rocks, producing a more varied landform pattern. In the west, glaciers fed by ice from further west were larger and more erosive than those in the central core of the area, resulting in generally lower mountains and hills. During times of higher temperature or reduced snowfall, small glaciers formed, particularly on north-east facing slopes as a result of wind-blown snow and shading. These glaciers carved deep corries into the edge of the plateaux, such as at the Northern Corries, Braeriach and Corrie Fee, creating distinctive headwall cliffs.

The Cairngorms were last fully covered by an ice sheet approximately 18,000 years ago. There is a marked contrast in the extent of glacial erosion between the essentially pre-glacial plateaux and the surrounding glens. The ice on the plateaux was probably thin and slow-moving and therefore incapable of much erosion.

Approximately 13,000 years ago, most of the ice had melted following climate warming. However, analysis of plant and insect remains, as well as landforms, indicate that Ice Age did not end in a smooth transition to interglacial conditions, but with a series of rapid climate changes. Glacial conditions returned around 11,000 years ago for about a further thousand years. Small glaciers reformed, their extents being marked by boulder moraines found in many corries. The extensive ‘hummocky’ moraine deposits at Drumochter were also formed at this time.

Writings of contemporary travellers indicate that parts of Braeriach may have held perennial snow or ice as recently as the Little Ice Age which occurred between the 17th and 19th Centuries. This certainly corresponds with known glacial advances elsewhere in Europe and with periods of worse climate and hard winters in Scotland.

The juxtaposition of 'pre-glacial' and glacial features within the Cairngorms massif forms a landscape of selective glacial erosion which is internationally recognised and forms a landscape of considerable geomorphological interest.

Meltwater activity

Many landforms in the Cairngorms were formed by meltwater rivers flowing beneath or off the ice sheets as they began to retreat and thin at the end of the Ice Age.

Highly mobile meltwater rivers, containing enormous volumes of water, carried large volumes of sediment and debris changed the patterns of unstable morainic debris deposited by the glaciers. These have formed a number of characteristic features still found in today’s landscape. In places, these rivers cut into underlying bedrock forming a series of channels which are now dry, such as the Chalamain Gap. Some rivers deposited sediment along the upper edges of glaciers as kame terraces or as eskers on the lower slopes. The northern flanks of the Cairngorms contain a nationally important assemblage of these features.

During the final stages of melting, areas of ice stagnated within the meltwater deposits, creating mounds and steep-sided hollows, called kettle holes, as the ice melted. This process accounts for the ‘hummocky’ landforms evident in Strath Spey around Aviemore. Well beyond the glacier fronts, meltwaters deposited large areas of sands and gravels in many of the main glens, which subsequently dissected as the discharge rate and carrying capacity of the meltwaters subsided. This process resulted in the formation of river terraces, as in Strath Spey and Glen More.

Periglacial Landscape

Since the end of the glacial period, cold climate, non-glacial processes continued to modify the landscape to varying degrees. In particular, frost and ground ice shattered the granite bedrock, producing extensive areas of broken rock or blockfields which cover many of the plateaux landscapes. On steeper slopes, frost weathering produced fall and the build-up of scree. Elsewhere, soil flow processes carried loose boulders downhill to create distinctive sheets, terraces and lobes of debris. This process continues today to a limited extent.

Landscape Stabilisation

After the end of the glacial period, the relatively warm, temperate climate led to an increase in vegetation cover. Initially, sparse vegetation cover allowed the sands and gravels deposited by glaciers to be easily shifted by running water. However, areas of sedge and grass pioneer communities soon colonised the hill slopes and valley floors and the binding effect of their root systems helped to create more stable ground conditions and reduce the erosive effects of running water.

As the climate continued to become warmer, so vegetation developed further, with dwarf birch, crowberry and juniper dominating an arctic shrub tundra vegetation. The landscape at this time still retained a strong open character.

By about 9000 years ago, birch and hazel woodlands developed in the glens with some oak and elm occurring in more local sheltered areas. Around 7000 years ago, there was a major expansion of pine forest which dominated the more acid, well drained soils. These pine forests extended to a maximum tree line of about 800 metres during this time. During periods of significantly wetter weather, which waterlogged soils and led to an expansion of blanket bog, the extent of pine forest was reduced. As these bogs dried out, so birch recolonised only to be overwhelmed by further peat growth in wetter periods.

Increased vegetation cover, though, did not mean that the physical processes of landscape evolution ceased: rather the nature, rate and location of these processes changed. Wide braided rivers continued to shift and erode sediments on the valley floors, creating large alluvial fans at the junctions of rivers. Debris flows from steep gullies created large cones of loose material, particularly after intense rainstorms.

Ongoing Physical Processes and Climate

Post-glacial modifications of the landscape are extensively represented by a wide variety of landform features, created by processes which continue to be active today. The vagaries of the Cairngorm climate may result in natural hazards, such as landslides, avalanches and floods occurring. Periods of prolonged wet weather, followed by a single intense rainstorm can quickly saturate and overload the soil capacity, resulting in debris flows on steep slopes. This often massive movement of material leaves many slopes scarred by gullies and debris chutes.

Heavy snowfalls, combined with complex air flow patterns, increase the likelihood of avalanches. The effects of avalanches are variable, but they can often sweep over large areas of unstable debris into the corries and glens, forming extensive boulder tongues.

During periods of flood, gravel beds can be moved by the fast flowing water which assists in the erosion of river edges and can result in abrupt changes in the course of a river. The River Feshie has altered its course on many occasions, indicating the dynamic character of rivers. The thin soils, steep slopes and largely impervious bedrock channel the rainfall rapidly into rivers and burns, causing rapid flash floods. These floods form extensive deposits along the length of the rivers. The steady build-up of gravels on alluvial fans can often lead to sudden channel switching by rivers, relocating large areas of gravel.

Post-glacial modifications of the landscape are extensively represented by a wide variety of landform features, created by processes which continue to be active today. The vagaries of the Cairngorm climate may result in natural hazards, such as landslides, avalanches and floods occurring. Periods of prolonged wet weather, followed by a single intense rainstorm can quickly saturate and overload the soil capacity, resulting in debris flows on steep slopes. This often massive movement of material leaves many slopes scarred by gullies and debris chutes.

Heavy snowfalls, combined with complex air flow patterns, increase the likelihood of avalanches. The effects of avalanches are variable, but they can often sweep over large areas of unstable debris into the corries and glens, forming extensive boulder tongues.

During periods of flood, gravel beds can be moved by the fast flowing water which assists in the erosion of river edges and can result in abrupt changes in the course of a river. The River Feshie has altered its course on many occasions, indicating the dynamic character of rivers. The thin soils, steep slopes and largely impervious bedrock channel the rainfall rapidly into rivers and burns, causing rapid flash floods. These floods form extensive deposits along the length of the rivers. The steady build-up of gravels on alluvial fans can often lead to sudden channel switching by rivers, relocating large areas of gravel.

This dynamic character is further illustrated by periglacial activities on the upper slopes. Wind eroded surfaces and frost-shattered debris create a series of distinctive landforms such as stone stripes and circles and wind patterning of vegetation.

Soils

A rich variety of soils types occurs in the Cairngorms National Park, often reflecting the fertility of the underlying rock. It includes those having arctic-like features on the high plateaux, pockets of fertile soils supporting many alpine flowers in sheltered corries, and deep hags in the blanket peat which covers vast tracts mostly between 450 – 750 metres elevation. Soils greatly influence the form and colour of the landscape. They also largely determine the amount, diversity and nutritive value of the vegetation and so in turn affect the types and number of many wild animals.

Soils form by the interaction of parent material, climate, relief and living organisms, usually over a long period of time. Some soils in the area are still at a very early stage of their development. Examples are the soils forming on bare scree or exposed rock, colonised so far by lichens or even only by bacteria and other micro-organisms.

The soils forming on the granite bedrock of the area are thinner, more arid, more gravelly and thus more infertile than those forming on schists. Soils forming on the small lime-rich patches of limestone which occur, at Blair Castle for example, are even more fertile. Where rich and poor rocks make contact, spectacular changes from heather to grass moorland occur, such as in Glen Builg.

The farmland on granite is generally poorer and extends less far up the hillside than on the richer rocks; this is why the soils of the farms of Strathdon are more productive than on the granite to the north of Lochnagar. Sheep grazing occurs on hills and moors underlain by schists. There are deeper, more fertile soil in Glas Maol, upper Glen Callater and Glen Fearnach.

Landcover Today

Due to topography and climatic constraints of the area, only a relatively small proportion of land is farmed, mostly concentrated in the straths. Livestock rearing is the principal agricultural activity with some production of winter fodder occurring on the better land. Most farms include a proportion of rough pasture and areas of hill grazing.

The Park contains 60 lochs. These, as well as marches, are a feature of the middle reaches of the Spey and include the extensive lnsh Marches which forms the largest floodplain mire in Scotland. It is Britain’s largest functioning floodplain at over 8 km long and nearly 3 km wide in places. Together with Muir of Dinnet, a large mosaic of heath woodland and mire, with peat bogs, swamps, fen and 2 lochs, these 2 sites are globally recognised as wetlands of international nature conservation importance as RAMSAR sites.

The Park area is relatively well wooded with approximately 16% of the total land area being covered by woodland, compared with 18% nationally. Much of this is concentrated in Badenoch & Strathspey and Deeside, where woodland coverage amounts to approximately 18% of the total land area. 81% of the tree cover is coniferous, with three quarters of that being native Scots Pine. By far the most dominant broadleaf species is birch (16%), with other species such as rowan and aspen making up only 3% of the tree cover. The National Park is home to a quarter of Scotland’s native forest. Native woodlands cover 8% of the area, and these include more than half of the surviving Caledonian forest, including the largest remnants, particularly located in the Glen Tanar, Rothiemurchus and Abernethy areas and extensive birch woodlands within Speyside and Deeside.

Conifer forests include a high proportion of Scots Pines and are mainly located in Glenmore, Deeside and Badenoch & Strathspey, while forests of spruce, larch and other exotics principally occur in Strathdon, the Angus Glens, Glenmore and parts of Deeside. One-third of conifer forests are on Ancient Woodland sites.

Heather moorland dominates the upland landscapes, covering approximately 44% of the total land area in 2014. The dominant form of moorland is managed moorland (189,552ha), followed by rough grazing (66,678ha), conservation (35,165ha), forestry (28,390ha) and native woodlands (19,384ha). Mountain blanket bog is found right across the National Park on shallow slopes between 500 - 800 metres, while montane vegetation of the high mountain plateaux includes internationally important arctic flora and is one of the least modified landscapes. Truly high montane bogs are found in areas such as Moine Mhor above Glenfeshie and Mar Lodge estate above 1000 metres. The Park also contains Scotland’s largest extent of bog woodland.

The land cover of the uplands has been changed considerably by humans. Farmers and crofters cleared trees and cut peats for fuel, and burned the hills to clear off the old vegetation and get fresh spring growth for livestock. The 19th Century saw muirburn for grouse moor management. Then, from the mid-20th Century, many estates drained their uplands/bog. The combination of these practices has affected the upland landscape, producing large areas of eroded peatland with extensive areas of bare peat and gullies.

HUMAN INFLUENCES

Background

Although the number of archaeological sites currently identified in the Cairngorms area is relatively low, field survey carried out by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland on the Mar Lodge Estate, Glen Shee and in Newtonmore/Kingussie has indicated that field remains of human settlement dating from the prehistoric period to recent times in these areas are more numerous and extensive than was previously thought.

Prehistoric Settlement

The most detailed, chronologically fixed, palynological (spores and pollen studies) work relevant to human communities has been conducted on the eastern margins of the Park, at Loch Davan and Braeroddach Loch. Using this work as an example it can be envisaged that progressive deforestation occurred during the later prehistoric period. For the first millennium AD, we have little palynological or bio-archaeological evidence to draw on, but cultivation, stock-raising, hunting and continuing exploitation of the forests may all safely be assumed to have continued in the area, although the scale of these activities is unknown.

Hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic

It is likely that the presence of rivers and lochs, and the altitudinal range at the local scale within the Cairngorms National Park area, would have made portions of the landscape of considerable attraction to broad-spectrum hunter-gatherers. There is still uncertainty about when people first inhabited the landmass we now know as Scotland. Although it is possible that inhabitation took place during the Lower Palaeolithic, any archaeological evidence before the end of the Ice Age – the Last Glacial Maximum – has not been found as Scotland was completely submerged beneath ice sheets. However, based on evidence elsewhere in Scotland, it is probable that such communities would have been established here at least 10,000 years ago.

Mesolithic period (10,000 to 6, 000 years ago)

It is worth remembering that there is very little visibility of Mesolithic archaeological evidence in Scotland, with only a few sites identified by scatters of lithic artefacts known as microliths, cave and rock shelters and middens. As well as being relatively ephemeral in the first place, Mesolithic archaeological evidence is also more vulnerable to erosion.

Much of the Mesolithic evidence to date has also come from islands on the West Coast, perhaps reflecting the coastal bias of the landscape survey studies that have been undertaken. Mesolithic sites in the Highland Zone are also mostly on land belonging to a single landowner with an archaeological interest.

However, evidence from elsewhere in north-west Europe suggests that communities with predominantly inland or coastal territories may have co-existed. Inland Mesolithic sites such as Chest of Dee, Aberdeenshire and Ben Lawers, Perthshire certainly indicate that Mesolithic activity penetrated the Highland Zone, and the Cairngorm’s river valleys and inland lochs would have likely been inhabited by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers as good places to fish, hunt and gather plants.

Chest of Dee, or Caochanan Ruadha, Glen Geldie in the Mar Lodge Estate for example lies at the southern end of a key routeway through the Cairngorm massif connecting Deeside with Speyside. It was first revealed following a discovery of flint artifacts in 2003 and excavations were undertaken between 2014 and 2016. They revealed a large number of non-local worked flints, most likely from the coast, and a possible small structure surrounding a central hearth. Radiocarbon dating indicated that the site was used approximately 8,000 years ago.

In Glen Avon, a barbed bone point was recovered from peat moss. Forming part of a larger, composite artefact such as a harpoon or spear used to bring down large quarry like deer, this object indicates at least the presence of a hunting party in this area at an early date.

Archaeologists have also discovered flint scatters in the Dee Valley. In the 1970s, a large number of worked flints were found at Nether Mills of Crathes by field walking (surface collection after ploughing) and subsequent excavations have revealed the remains of structures.

The Neolithic Period and Early Bronze Age: first farmers and monument builders

The Neolithic period is typically dated from 4,000 BC to 2,500 BC. The appearance of funerary and ritual monuments - including chambered tombs, ring cairns, stone circles and stone settings, and round cairns – marks the fourth to second millennium BC in terms of the visibility of its archaeological record in Scotland. These monuments appear alongside with the domestication of wild plants and animals, the first appearance of pottery and new types of stone tools.

However, monuments made of timber such as the Early Neolithic timber large houses known as ‘halls’ are among the earliest evidence for any Neolithic presence in this region. Examples include Crathes and Balbridie, on either side of the River Dee and both of these sites contained evidence of cereal crop cultivation along with the gathering of wild plants including hazelnuts and crab apples. Although the animal remains were not well preserved, lipid analysis of the Crathes pottery has revealed that the occupants’ cattle/sheep/goats had been used for dairying because traces of ruminant milk fats were found in them. The presence of Arran pitchstone at Crathes also indicates that the occupants participated in a network of wide-ranging contacts.

Many of the stone Neolithic funerary and ritual monuments that appear at this time are positioned in relation to distinctive topographic features such as rivers, hills and mountains and are located near to routeways across and between different terrestrial and marine landscapes. The two Late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age cairns at Cairn O’Mount are good examples of this, given their location at 455m AOD and location adjacent to the B974 Cairn o' Mount road which runs between Fettercairn and Banchory. This elevated location affords extensive, panoramic views out over the surrounding upland landscape, and the monuments are also highly visible features within this landscape and a well-known landmark from modern day travellers along the modern road.

Other ritual and funerary monuments are presently located in much more modern settings however. The Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age site at Aviemore for instance, which comprises a Clava-type chambered cairn surrounded by a stone circle, is now set within a modern housing development, although more long-distance views out over the landscape are still possible in some directions.

Other sites dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Age include Glen Avon. Excavations there uncovered a flint leaf-shaped arrowhead dating to the Neolithic (i.e. the fourth to the second millennia BC) and a flint barbed-and-tanged arrowhead probably dating to the Early Bronze Age (2,500 – 1500 BC) were recovered. These artefacts reflect a time when hunting would have been practiced by farmers seeking to supplement their diet with game. The Bronze Age in Scotland begins in 2500 BC when people first start to use metal, a new type of pottery vessels known as ‘Beaker’s and change their funerary practice from communal to individual burials. It ends around 800 BC when iron objects first appear.

Later prehistory: farming and society in the last millennium BC

The first millennium BC, comprising the later Bronze Age and the pre-Roman Iron Age, is marked, by major changes in the nature of the surviving archaeological remains. The burial and ritual monuments which characterised the earlier periods are superseded in the visible archaeological record by a variety of settlement sites, ranging from farmsteads consisting of groups of hut-circles, to stoutly defended, stone-walled hillforts.

Dating from at least as early as the later Bronze Age, the hut-circles (i.e. the remains of round houses), and in some cases their associated field-systems, still survive within modern farmland, but they are more characteristic of moorland areas which have not been cultivated since the prehistoric period. Their widespread distribution gives some indication both of the extent to which prehistoric people had occupied the area and the likely major impact of early agriculture on the forest cover.

In contrast with the open settlements represented by the hut-circles, the area also includes a number of enclosed settlements ranging from crannogs (lake dwellings), to palisaded sites, and the better known hillforts. Many of these sites occupy prominent positions in the modern landscape, and it is clear that these hill-top positions were carefully chosen to command views and control movement through the landscape. Because they are also highly visible features within the landscape, they would have also been visually impressive and powerful sites.

The Early Historic Period

The history of this area in the centuries after the Roman withdrawal is dominated by the Picts, the indigenous inhabitants of what we now know as Eastern and Northern Scotland who were given their name Picti by the invading Romans. The Pictish period dates to the Iron Age (800 BC to AD 400) and the main archaeological evidence comes from symbols on standing stones and other objects, and place names containing the word Pit. However, excavations in recent years are providing a filler picture of their lives, including settlement and burial sites.

Pictish symbol stones are perhaps the most visible part of the Pictish archaeological landscape and are of huge significance in relation to the nation’s and local identities. Although few are in their original location, they tend to be found located next to routeways or at church sites, and many are re-used prehistoric standing stones. There is an impressive collection of carved stones at Tullich Kirk just outside Ballatar, including Pictish symbol stones which have been conserved and displayed within a modern shelter.

The Gaelic-speaking Scots extended their hold on Scotland steadily during the second half of the first millennium. Another major strand during this period was provided by the expansion of the Irish form of Christianity: based on powerful abbots, rather than bishops with territorial sees to occupy them, and with a tradition that encouraged the foundation of outposts in new territory: an example of an early establishment in the Columbian tradition is represented by St Nathalan's, at Tullich on Deeside. Although there is evidence for Norse activity in the lowlands of Moray, there is no evidence of Norse settlement in the Park.

The Medieval Period

Throughout the medieval period, the area seems to have remained predominantly rural, and its inhabitants to have depended on the exploitation of its crops, livestock and forestry.

Access to the area from the south was always restricted by the scarcity of hill passes through the uplands, it is therefore unsurprising that many of the principal structures, both physical and terrestrial, associated with the consolidation of medieval kingship in Scotland are relatively infrequent in the Park area or are sited near its orders. Relative isolation from the central powers to the south undoubtedly contributed to the power of the local aristocracies. Thus the castle mounds called mottes, characteristic of the establishment of a Norman aristocracy, are infrequent, and essentially confined to the principal valleys. Equally, with the exception of Cromdale and possibly Glenlivet, thanages - territories administered directly by a royal official - are absent from the area.

A number of Earldoms, including Mar (which encompassed the valleys of the Dee and Don and much of the intervening area) and Atholl, existed on a semi-independent basis while, from the 15th Century onwards, control of Upper Strathspey, was divided between the Gordons and the Grants. Castles and ancient churches are still evident in the landscape from this period and include Kindrochit Castle in Braemar which was a hunting seat of the Kings of Scotland and located in a strong position close to the rocky gorge of the Clunie. The principal stronghold of Atholl, Blair Castle, originally consisted of a strong tower like Kindrochit Castle, and was built from 1269 onwards, but considerably remodelled in later times. Other medieval strongholds included stark towers, like Drumin Castle in Glenlivet, set at the confluence of the Avon and Livet and commanding the Lecht route into Speyside.

Lairds also constructed stone castles during this period, for example, Castle Grant in Strathspey and Muckernish near Duthil, Abergeldie. The forests of the area provided sport for a succession of Scottish Kings and nobility, thus some of these castles served primarily as bases for hunting expeditions. The Earl of Huntly had Blairfindy built for his hunting parties in Glenlivet (from 1546), while the Erskines of Mar were responsible for hunting seats at both Corgarff in Strathdon and the Castle of Braemar (these examples were transformed into Government barracks1745, garrisons were stationed at several places to ensure the Hanoverian hold on the area).

Although depletion of the forests to accommodate agriculture probably continued throughout this period, powerful landowners were anxious to maintain some degree of control over the forest, not least because of its role in providing a habitat for game, and could, as in the case of the Earls of Mar, make use of their feudal powers to achieve this. The forests of Mar and Atholl were favoured hunting grounds of the Royal House in medieval times, and the Earldom of Mar, when not under the direct control of the Crown, was normally strongly under its influence. Limited tree felling was tolerated, but on occasion, peasants cutting down trees were punished to ensure that such activities did not become too extensive.

One of these big estates is the Mar Lodge Estate which is the largest property owned by the National Trust for Scotland (NTS). It is located on the southern edge of the Cairngorm Mountains, at the heart of the Cairngorms National Park. The Estate comprises a diverse landscape of montane plateau/corries, wooded glens, open moorland, upland glens and the more populated valley bottom of Upper Deeside, providing a marked transition from managed to wild landscapes.

Some of the areas within the Estate have been identified as being scheduled monuments, meaning they are of national importance because they contribute significantly to our understanding of the past. These are concentrated in the Dee and Lui glens and here there is excellent preservation of features relating to three main forms of land-use: townships and associated shielings from the medieval and later period of settlement; sheep farms of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century; and the framework of the late nineteenth-/early twentieth-century shooting estate. The two shieling groups at Alltan na Beinne and Derry Burn are contemporary with the townships and are evidence of the practice of transhumance that was integral to the economy of the area until the late eighteenth century, when it began to decline with the introduction of sheep farming. There are also two mill sites on the Quoich Water.

The absence of intensive farming or settlement in these areas since their abandonment has ensured a good level of preservation and resulted in the survival of a relatively complete relict landscape. These archaeological remains, combined with a substantial documentary resource, permits a more detailed, in-depth understanding of these material traces than would otherwise be possible. However, they are under threat from expanding and unmanaged woodland.

The 17th and 18th Centuries

Significant landscape change would have occurred throughout this period as the forests of the area were exploited for timber on a large scale, and as agriculture expanded into the higher ground as the population increased. Communications were also considerably improved, largely due to the construction of military roads, and planned settlements were instigated by landowners interested in promoting new industry to the area.

Timber Exploitation and Other Industry

The first large-scale timber exploitation in Speyside was in Abernethy forest where all the pine woods in the parishes of Abernethy, Duthil and Kincardine were leased for four decades from 1630 without limit on exploitation. Although the activity was not on a modern scale, available technology and transport difficulties serving to restrict it, the landowners, the Grants, nonetheless realised that replanting was necessary, and some was carried out. At the time, the pines of Speyside were described as stretching virtually uninterrupted for 24 miles. At the beginning of the 18th Century a substantial shipbuilding industry grew up at Kingston-on-Spey in Morayshire from 1785 using Abernethy Pine and lasted almost until the end of the succeeding century. Not all timber was, however, used for naval requirements: the area also produced timber for London’s first piped water supply, installed in the 1770s, and charcoal was also in demand for ironworking for armaments manufacturing.

Commercial exploitation of the forests of Mar on the other side of the Cairngorm massif, did not begin in earnest until the 1770s when the Earls of Fife felled a large part of the woods in Glen Luibeg and floated the timber down the Lui Water to a sawmill near Muir.

Other attempts to develop industry in the wake of forest exploitation followed. Thus, in 1728, the York Buildings Company purchased 60,000 of the finest pines from the Grants on Speyside and embarked on an ambitious programme of construction of sawmills, roads and blast furnaces for smelting iron ore, using local charcoal. Rocks were blasted from the bed of the Spey to facilitate the transport of timbers down the principal river course.

Rural Settlement and Farming Practices

Due to the exposed upland nature of much of the area, its use for arable agriculture, and more especially cereals, has always been restricted. In the uplands of Mar, sheep farming supplied the Aberdeenshire trade in woollen cloth. In the eighteenth century, the development of arable cultivation in the lowlands of Scotland, and access to the English markets, gave a considerable momentum to the export of black cattle from northern Scotland to the trysts at Falkirk and Crieff, and cattle droving through the landscape increased significantly. The drovers' dislike of tolls and of passing through countryside congested with buildings, walls and undergrowth led many from the north to favour the route via Strathspey, the Avon and Corgarff to Ballater, whence alternative routes to the south included Glen Muick or Braemar and Glen Calalter (Toilmouth) to the Angus Glens, or Braemar and Glen Clunie to Glenshee and Perthshire. The ancient passes through the central Cairngorms, the Lairig Ghru and the Lairig an Laoigh were also used. Haldane notes that the former was still in use as late as the 1870s when men were sent each spring to clear the path of stones. Glen Muick seems to have continued to be used for droving for a further decade. Indications of this activity are furnished by the eroded trackways, often particularly visible in the vicinity of stream crossings.

Agricultural systems in the uplands, based around communal farming townships comprising families, seem to have reached a zenith in the 1760s when, according to an 18th Century legal case, never had so much land been under the plough. In numerous valleys, including Glens Ey, Clunie, Dee, Lui and Banchor, substantial areas of ground cleared of stone, and the footings of buildings and ancillary structures, like corn-drying kilns, indicate that crops were grown at up to 410 metres. Also apparent are the strips associated with the run-rig cultivation; extensive enclosed arable fields are uncommon beyond the lower valley sides. Indeed, in some parts of upper Deeside, unconsolidated strips of arable land persisted as late as the 1850s.

The practice of transhumance (moving livestock from one grazing ground to another seasonally) was carried out throughout the area. Shielings, consisting of groups of huts constructed of varying combinations of wood, stone and turf, were in use between May and September for the inhabitants of the townships, in order to protect arable ground from the trampling and grazing of livestock.

Buildings and Communications

The major communications network present within the area today, owes much to the network of military roads and garrisons, e.g. Ruthven Barracks, constructed in the wake of the 1715 rising and more particularly after 1745. The old A9 from Perth to Inverness followed the route of the Military Road built by General Wade in the 1730s, while a later road planned by General Caulfield and intended to connect the new coastal fort at Fort George with Blairgowrie passed through the area. These roads were designed to facilitate troop movements in what was essentially occupied territory and were accompanied by outposts on either side of Drummochter (at Dalnacardoch and Dalwhinnie), Braemar, Glen Feshie, Glen Clunie on the Dee, lnchrory and Corgarff on the Don, and at Glen Muick and Glen Clova to control the throughways to the Angus Glens. The routes of some of these roads have become unclear but stretches of the Corrieyairack road, which remains as a track and links to the western edge of the Park, are a Scheduled Monument.

Many of the settlements in the area are planned villages, laid out by improving landowners for a variety of purposes. Ballater, established by the Farquharsons of Monaltrie, was explicitly created to house visitors to the spa at Pannanich. Tomintoul, on its high and isolated hillside, was laid out by the fourth Duke of Gordon from 1770, with the aim of exploiting the “inexhaustible” peat moss and quarried slate in the vicinity; while Grantown was set out in 1776 by James Grant of Grant, with the aim of attracting carpenters and other craftmen, in order to stimulate the demand for timber. Planned villages tend to have a main street and village square, like Tomintoul and Grantown; and a standard architectural style and/or building material. These can be seen in the settlement core, often now surrounded by more recent development

The 19th Century

Agricultural and Estate Improvements

From the middle of the 18th Century, landowners began to invest in agricultural and estate improvements, effecting a complete transformation of the rural landscape and creating the distinctive landscape of agricultural ground in the Cairngorms. This included the layout of new farms, rectilinear enclosures, the drainage of wet ground, and other improvements, and led to the clearance of many townships in the highland glens and the concomitant abandonment of transhumance. This process entailed much migration of population, but many tenants, as on the Earl of Fife's Estates in Aberdeenshire, found employment elsewhere. However, the chronology of highland clearance is spread over a long period, for example, Glen Lui on Deeside was cleared in 1776 but Glen Banchor in Speyside was not abandoned until almost 100 years later: the one being the result of a single traumatic event and the other of a more gradual process as townships in upland locations became uneconomic.

By the time of the New Statistical Account in the 1830s/1840s, improvements in rural housing were under way. In Duthil, drystone and turf houses were replaced by gabled, stone and lime thatched cottages, with window glass. In Braemar, the larger farms had stone built houses with slate roofs, although the smaller buildings were still capped with heather sods. Prince Albert and Queen Victoria's improvements to the housing on the Balmoral estate stimulated other landowners to follow suit and less cramped stone and lime farmhouses and shepherds' and keepers' cottages appeared in the glens.

The introduction of sheep farming in the early 19th Century was successful in some of the richer areas, such as Glen Shee and Glenlivet and around Corgarff, but was less so in areas where available vegetation was less plentiful or was unsuitable, as in Glen Derry. However, the importance of hunting and timber production meant that sheep farming was never introduced on the scale of many other parts of the Highlands.

The Growth of Sporting Estates

The medieval practice of hunting within the forests of the areas had all but died out, partly due to the traditional nobility’s forfeiture of its estates after 1745, and the widespread felling of the open Caledonian pine forests which had formed the principal habitat of the deer. Stalking in the modern form began around 1800.

With the decline of sheep farming in the second half of the 19th Century, the area of deer forest expanded, and numbers of deer increased. The ‘adoption’ of Deeside by Queen Victoria, played an important role in the growing popularity of the area for sporting activity. The freeing of further ground from sheep, from the mid-19th Century onwards also allowed the development of grouse moors on the uplands surrounding the mountainous core of the Cairngorms.

The major development of deerstalking in Strathspey occurred later than in Deeside, and the lower deer population of the former area allowed considerable regeneration to take hold before the upper parts of Abernethy parish was cleared of its farms and their families by their respective owners, the Gordon family, for deer. This occurred in the 1860s. Some of the younger stands of pine were however protected from the grazing activities deer by fencing, including considerable areas in Abernethy and Rothiemurchus.

An Age of Building

As well as the upgrading of the housing stock which characterised the 19th Century, places of worship were almost all renewed. Many old castles, as has been noted above, were given substantial extensions in the Victorian period and many of the planned villages, established in the 18th Century, expanded to service the needs of sportsmen and travellers. The accent on hunting was accompanied by the creation of increasingly sumptuous lodges in which to accommodate the hunters, often with additional designed features in the landscape around them. Thus the Duke of Fife’s high Victorian Mar Lodge of 1898 was in fact the third such lodge on this estate, each one grander than its predecessor. The construction of shooting lodges occurred throughout the area during the 19th Century, and, whilst some were intended for year-round occupation (by the staff at least), others were intended solely for use during the summer season. Some, many of them now ruinous, were located in extremely inaccessible spots, for example Slugain Lodge, near Invercauld, Bynack Lodge or Altanour Lodge in Glen Ey.

Many of the lodges built on sporting estates had designed landscapes created around them. The nearby Falls of Corriemulzie on the Dee were also rendered more picturesque by the planting of specimen trees in their vicinity, continuing a practice earlier exemplified by the Duke of Atholl elsewhere, around the Hermitage on the River Braan.

The development of railway links to the south attracted not only sportsmen but, later, tourists to the area. The line from Perth to Inverness via Forres through Drummochter was begun in 1861 by the Highland Railway. The Deeside line reached as far as Ballater in 1866 but an extension contemplated to Braemar and thence to Blair Atholl through Glen Tilt was probably prevented by Queen Victoria’s influence; she did not want her privacy further affected, or the native pinewoods of Ballochbuie interfered with.

Tourism to the area grew and was linked with the writings of early travellers and to the Royal associations with Deeside. Most of the area’s hotels, built to accommodate increasing numbers of visitors date from the 19th Century, and were often the outcome of transforming small inns into massive Victorian structures often copying the styles of nearby landowners’ lodges.

Industry

Although forestry was not as important as it had been in the 17th/18th Centuries, due to the value of open moorland for shooting and stalking, the reputation of Speyside timber ensured markets for timber and good forestry management practices continued. The planting of extensive forests mainly comprising exotic conifers was, however, an uncommon practice in the area, although 19th Century plantings of larch and spruce occurred on some estates in Strathdon and Deeside. The Atholl estate was the first in the UK to import European larch in the 18th Century and it has remained an important species for the estate ever since.

Industries other than quarrying, forestry and agriculture were not significant in the area in terms of impacting directly on the landscape, with the exception of distilling. In the 1790s the making and drinking of whisky was practiced by all 37 families in Tomintoul, and in the 1820s there are reputed to have been at least 200 small stills in the Glenlivet area. The earliest legal distilleries date to the early 19th Century and it is from this period that an industry, once secretive, begins to make its presence in the landscape felt. 19th Century distilleries normally display distinctive pagoda-like roofs and associated clusters of buildings as drying barns and for storage. Examples include those at Pitlochry and Dalwhinnie, and, the sole example on Deeside, Royal Lochnagar (1884). Many have been significantly extended in recent years and a new one has been approved at Grantown.

20th Century Change

The landscape of the area saw a number of landuse and developmental changes in the 20th Century, many of these affecting landscape character to some extent and including changes to forests and woodlands and the agricultural landscape, and consequent effects on semi-natural habitats. Considerable landscape change also occurred in the area through new-built development, including the expansion of settlements, recreation facilities and infrastructure.

Woodland

Although the overall pattern and extent of woodland did not change significantly in the majority of the area in this period, the management and composition of these woodlands considerably altered as exotic conifers were increasingly planted, from the 1920s onwards, replacing what would have been Scots Pine, although some of this would have been 19th Century plantings. Such replacement planting would have affected the character of the original woodlands which in the past comprised both commercially managed woodlands and remnant semi-natural Caledonian pine forest. Activities such as drainage, ploughing and a high stocking density disrupted the intricate pattern of glades and diversity of land cover throughout the native forest, which occurred as a result of natural regeneration, which was also used as a restocking method in the pine woodlands which were commercially managed from the late 17th Century onwards.

Many of the large scale forests of spruce and larch, present in Glenmore, Inshriach, the Angus Glens, Strathdon and Strathspey, and Glen Livet, were planted on marginal hill farms from the 1940s onwards, although landowners in Strathdon and Deeside often planted such woodlands from the late 18th and 19th Centuries. Although many of these new forests often replaced Scots Pine woodland some were established on heather moorland, thus diminishing extent of this land cover, for example, in Strathspey and Glen Clova. In Badenoch and Strathspey District between the 1940s and 1970s, semi-natural conifer woodland decreased by 39% and heather moorland by 11% while coniferous forests substantially increased from 76 square kilometres to 239 square kilometres over the same period. Similar increases in conifer forest have been estimated within Kindcardine and Deeside at the expense of semi-natural habitats such as heather moorland and native pine woodland, the latter suffering a 70% loss between the 1940s and 1970s.

Many of these forests contribute to landscape character, however others were planted at a time when the objectives of planting were markedly different and when current design standards did not apply. This has resulted, in some instances, in a legacy of forest planting which can be poorly scaled and shaped and, in a few areas, illogically located in the landscape.

The remaining semi-natural pine forest has become considerably fragmented and small in extent and has been under decline in many areas, due to deer grazing pressure, since the late 19th and throughout the 20th Centuries. Little or no natural regeneration is evident in many areas.

Agriculture

The 20th Century saw agriculture in the area become less intensive, as hill farming became less profitable. There is now relatively little cultivated land, and sheep and hill cattle occupy areas lower down the hills and in the straths. Policy and fiscal incentives were a feature of the latter half of the century aimed to intensify farming methods and this often resulted in the decline of traditional features of the strath farmland, for example, stone dykes, unimproved pasture, wetlands, and broadleaved woodlands. Between the 1940s and 1970s, wet ground decreased by 40% within Badenoch and Strathspey District, while semi-improved and improved pasture significantly increased, indicating that considerable drainage of land occurred throughout this period. Arable land also decreased by around 15% in this district over the same period, while a 15% increase in sheep numbers occurred in some areas of Badenoch and Strathspey between 1946 and 1988. More extensive grazing of sheep, as separate small-holdings were combined, has also occurred.

Development and Land-use Changes

Some of the most obvious changes that occurred to the character of the uplands and high mountain areas, were associated with the construction of access tracks for sporting use, and forestry and ski developments at Coire Cas on the Cairngorms in the 1960s and later at Glenshee and the Lecht. The increasing popularity of the Cairngorms for some recreational activities has introduced built developments such as tracks and roads, car parks, ski tows and runs. This has diminished the wild land qualities of the mountains.

Two long-distance walking and cycling routes which are partly in the Park were developed in the 20th Century. The Speyside Way first opened in 1981, to run from Spey Bay to Ballindalloch, with a spur to Tomintoul being added in 1990 and further extensions which now extend to Kingussie. The Deeside Way, which extends from Aberdeen to Ballater, has been developed in stages since 1992, largely following the route of the old Deeside Railway. It is currently proposed to extend as far as Braemar.

Built development also increased considerably in parts of the Park throughout the 20th Century, being mainly concentrated in the Speyside area, where Aviemore was substantially extended in the 1960s as a tourist centre. It developed into the distinctive centre for outdoor recreation that it is today. Expansion of other towns in the area also occurred, although not on the same scale. Rural housing increased in the Speyside area as people were attracted to live in the area, although in more remote parts of the area such as the Angus Glens, upper Spey and Laggan, the population gradually declined throughout the 20th Century.

Cairngorms National Park in the 21st Century

The Cairngorms National Park was designated in 2003, aiming to conserve and enhance the natural and cultural heritage of the area, promote sustainable use of the natural resources, promote understanding and enjoyment (including enjoyment in the form of recreation) of the special qualities of the area by the public, and promote sustainable economic and social development of the area’s communities. There is a specific policy to protect and enhance the landscape character and Special Landscape Qualities of the Park.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority was established to promote partnership working and give leadership to all those involved in the Cairngorms. It now employs around 70 people and has its headquarters in Grantown-on-Spey. The Cairngorms National Park Partnership Plan has 3 conservation priorities;

- Supporting landscape collaboration. For example, the Tomintoul and Glenlivet Partnership are working on habitat improvements and local community projects. Their Dark Skies initiative, for instance, aims to create an area of 265km2 to become a Dark Sky Park, one of only 2 in Scotland, if their application to the Dark Skies Association is successful. The Partnership also includes cultural heritage initiatives, such as making Tomintoul Museum a Discovery Centre and tourist hub, conserving and making safe Blairfindy Castle and Scalan (an 18th Century seminary), and a regional oral history project which will collect stories that bring the landscape to life and record abandoned settlements to provide a better understanding of the local heritage.

- Deer Management, for woodland expansion, peatland restoration and for designated sites. A general trend is to reduce deer numbers and maintain economic contribution of sporting stalking to the economy.

- Moorland management. Over 800ha of peatland is currently under restoration management. In 2018/19 Peatland Action awarded funding to another 1052ha, with another 2500ha in the pipeline for the future.

Tourism and Recreation

The creation of the National Park has increased visitor numbers, with more pressure on recreation facilities. For example, popular mountain paths have become increasingly well-used, which has led to the “Mountains and People” project which improves existing paths and builds new ones. From 2014-2018, 35.5km of paths have been improved or created under this initiative. The Park caters for a wide range of activities including walking, mountaineering, skiing and water sports; these often require associated facilities such as car parking.

Increased visitor numbers have also lead to more interpretive initiatives, such as the creation of the “Snow Roads” which promotes the 90 mile route between Blairgowrie to the south of the Park and Grantown-on-Spey. Along this, there are photo posts for Fixed Point Photography and several sculptural installations, all of which are aimed at increasing visitors’ enjoyment and perception of the varying landscapes along the route.

There is also continued pressure for visitor accommodation, especially in the main tourist destinations. The prosperity of the tourism sector has led to new facilities being developed, such as a distillery and visitor centre outside Grantown-on-Spey at Craggan. The Strathspey Steam Railway, which follows a line closed in the 1960s, opened in 1978 and runs from Aviemore to Broomhil. The“Rails to Grantown” project hopes to extend the railway from Broomhill to Grantown in the future.

Forestry

The long heritage of woodland management continues, with emphasis on good environmental management. In last two decades a number of estates have significantly reduced deer pressure resulting in significant regeneration without the need for deer fencing, which has saved some pinewoods from serious decline. Deer control, limited sheep grazing and controlled management have also led to woodland management on the edge of moorland. The emphasis on woodland expansion led to over 4600ha of woodland being created in the National Park between 2013 and 2018. The Cairngorms National Park Authority issued a new forestry strategy in 2019 with the key objective being to create new woodland and integrate it with different land uses.

Population and housing

The National Park has a distinctly different population profile to the national one, with a higher proportion of people falling within the 55 to 74 age bracket. When compared to other rural parts of Scotland, the Cairngorms National Park also has a relatively high proportion of residents aged 10 to 29. This is thought to be due to the relatively high number of opportunities for employment in the outdoor and tourism sectors.

Infrastructure

The growth of the renewable energy sector, primarily wind turbine development, to the north of the Cairngorms National Park led to upgrading of major overhead power lines. This included the Beauly Denny overhead power line, which provided an opportunity to, in places, locate some transmission cables underground and remove some others. In some locations existing pylons have been replaced with larger pylons, such as those which are aligned through the Drumochter Pass in the south-west of the Park.

The A9 in the west of the National Park is being upgraded to dual-carriageway. This will alter the landscapes and perception of the route to varying degrees, being most obvious in open upland areas. There have also been recent improvements to the railway line between Perth and Inverness (the Highland Main Line), to increase connectivity between north and south Scotland include additional loops, dynamic loops and lengthening of double track sections. These changes will also increase frequency and speed of trains that may lessen the tranquillity of the route.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES

Introduction

The Cairngorms have often displayed rather distinctive traditions, which can be coarsely characterised as, firstly, those of the Spey and its catchment; secondly of the great rivers (the Dee and the Don) of the northeast which reach the sea at Aberdeen; thirdly of the headwaters of the southward-trending river valleys (such as the Tummel which flows south to the River Tay and South Esk which flows east to the River Esk, which reaches the sea at Montrose); and lastly the Grampian massif centred on the Cairngorms themselves.

The name Cairngorms is, in the present day, applied to a large area of mountainous country which is somewhat vaguely defined, as it has been since the term came into common use some two hundred years ago. The original name for the central Cairngorms massif was in Gaelic, Monadh Ruadh, i.e. red mountains, a name given to these mountains by the people of Badenoch, in contrast to the Monadh Liath (grey mountains), lying further east nearer to the Great Glen of Inverness-shire.

Despite the impact of humans on all areas of the landscape, and the remains of recently cleared settlement that scatter upland and lowland alike, the sense of remoteness and timeless character of the Cairngorms in terms of both their landscape and their culture has impressed many visitors over the centuries. One of the greatest experts on the Cairngorms, naturalist, photographer and folklorist Seton Gordon (1886-1977), believed that the principal qualities of the Cairngorms to be their emptiness, the extensive views from them, and their rapidly changing and extreme weather conditions. These factors are all recurrent themes in depictions, both literary and artistic, of the area, and also pervade accounts of the characteristics of the populations inhabiting these areas. More recently, the entry for the Cairngorms in Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland (1994, 121-122) notes;

"Their extent (c. 300 sq miles) and elevation,… flora and fauna ... and recreational facilities ... are distinctly more exciting than their profiles. Even the four summits over 4000 feet are literary nonentities compared with Scott’s Trossachs, Ben Lawyers or Schiehallion."

As regards the weather, Andrews (1989) in remarking how the early phase of cultural tourism to Scotland in the 18th Century rarely extended beyond Perthshire, noted that mists and rain were already a factor discouraging penetration through Drummochter, or over the other upland passes into the area.

Greater remoteness from southern centres of literary and artistic elites, external perceptions of the area more especially after the Second Jacobite Rising in the mid-18th Century, and the relatively late (and incomplete) penetration of the area by both roads and subsequently the railways, may all be considered to have contributed to the late upswing in interest in the landscapes of the areas. To these factors must be added matters of taste in terms of landscape appreciation. Compared with the Trossachs, for example, much of the landscape of the area does not seem to have corresponded to 18th Century perceptions of “the picturesque”, further appreciation of these landscapes being developed in the 19th Century and having continued until the present day.

Amongst the 19th Century figures, the celebrity of the area, particularly the eastern sector, owes much to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s well publicised affection for the Central Highlands. Although this royal endorsement, and the influence and artistic patronage which ensued from it, were important for the subsequent popularity of parts of the Cairngorms, the prospect of impressive sights had already drawn visitors to the area considerably beforehand and instances of accounts of early tourists will be given below.

Another major influence in the discovery of the area - attributable to the presence of the Cairngorm massif itself - has been the development of mountaineering. Here, the landscape is perceived to offer “a physical challenge to mankind to produce a distinct but not wholly different emphasis”.

Early Travellers' Accounts of the Cairngorms

The appreciation of the qualities of some of the landscapes of the Cairngorms is relatively recent, reflecting landscape perception at the time of the travellers’ visits, although many of these accounts could be considered not representative of wider views as they were often published by rich male writers.

One of the earliest accounts of a visit to the Cairngorms comes from the pen of John Taylor (born 1580). Wyness has described him as "Deeside's first ‘tourist’ to write an account of his visit to the valley". Taylor later published an account of his experiences, under the title The Pennyless Pilgrimage (1630). He was most impressed with the height and steepness of the surrounding hills, observing “mount Benawe, with a furr’d mist upon his snowie head instead of a nightcap, for you must understand, that the oldest man alive never saw but the snow was on the top of divers of those hills, both in summer, as well as in winter." (quoted by Hume Brown, 1891). He also noted the abundance and quality of the pines in Mar, and visited Speyside (Alexander, 1938).

The improving Midlothian landowner and antiquary, Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, wrote in 1739 that in travelling "from Dalwhinny about 10 or 12 miles we came to Riven (Ruthven) in Badenoch... I could see nothing but a barbarous tract of mountain on both hands and scarce a stalk of grass to be seen" (quoted by Smout, 1983).

Thomas Pennant passed north through the Glen Tilt-Glen Feshie route to Braemar on his way to Aberdeen in 1769. In his Tour in Scotland (1771) he comments, of the pine forests of Braemar (reached after crossing what he described as "dreary wastes”):

"Some of the trees are of a vast size: I measured some that were ten, eleven and even twelve feet in circumference... the prospect above these forests is extraordinary, a distant view of hills over surface of verdant pyramids of pines" (Pennant, 1770, 130).

Other characteristic observations of the highland landscapes include the "horrible grandeur" of the Garry at Killiecrankie, and the size and number of the stags on the Duke of Atholl’s estate, where they occur in "the forests, or rather chases (for they are quite naked), which are very extensive….”. Pennant's comments on the quality of the woodland, already peppered with commercial references, but he notes too the range of wildlife present and comments on the impoverished lifestyles of the more lowly inhabitants, and the ugliness of their womenfolk. Such observations become part of the stock-in-trade of subsequent commentators. On the whole, the population and its humble architecture did not lend itself to incorporation into the “picturesque”,as sought by succeeding generations of aesthetically-informed visitors.

Nan Shepherd, author and poet, writing in the 1940s (published 1977) about the Cairngorms plateau and the clear waters it gathers and disperses, wrote “water so clear cannot be imagined, must be seen. One must go back, and back again, to look at it, for in the interval memory refuses to re-create its brightness. This is one of the reasons why the high plateau where these streams begin, the streams themselves, their cataracts and rocky beds, the corries, the whole wild enchantment, like a work of art is perpetually new when one returns to it. The mind cannot carry away all that it has to give, nor does it always believe possible what it has carried away”.

These contrasting views encapsulate different perspectives of landscapes through time. Some of the historic landscape changes - notably those of settlement and population, and of deforestation and subsequent reafforestation - have complemented varying attitudes to the austere beauty (the "Sublime" of writers from the mid-18th Century onwards) or of "desolation” and wilderness” as substantial parts of the area have also been considered.

In the late 18th Century the Government attempted to integrate the Highlands with the rest of Great Britain. The construction of roads and the compilation of maps, gave travellers more confidence in planning journeys. Military officers stationed in the Highlands in the aftermath of Culloden, spread curiosity about the Highlands and their ‘primitive’ people amongst the southern upper classes, who also came into contact with the major Highland landowners as they took up residence in London.

Burns, visiting the Falls of Bruar on the Duke of Atholl’s estate in 1787, appealed to the Duke to enhance the beauty spot by planting trees, a wish that was soon to be fulfilled. The large number of published accounts of tours and Government investigations into the Highlands raised the profile of the area among the then rather select circle of potential visitors. The first guide specifically devoted to the mountains themselves appears to be Scenery of the Grampian Mountains written George Fennell Robson (1814), republished with coloured plates five years later. A mountaineering Club Guide to the Cairngorms was published in 1938 (Alexander, 1938).

Literary Influences

Other factors contributed to the rise of external interest in the central Highlands. The popularity of the poems of Ossian, collected and embellished, if not wholly composed, and published by James Macpherson of Ruthven (Badenoch) from 1760, led many to tour the locations traditionally associated with the legendary bard, in order to have a fuller appreciation of the settings of ·his work. Ossianic poetry evoked acts of Highland chivalry set against a background of mountainous scenery which, if "ridiculously melodramatic to modern ears" (Smout, 1983) was far from so at time of their publication. Acclaimed by Professor Blair of Edinburgh, the Ossianic cycle prompted cultured tourists to venture further north to identify the literary context and associations of that work and simultaneously to view landscape, not then conventionally beautiful, but rather "sublime... that would fill them with the frisson of inspiring terror" (Smout, 1983), but from which they were relatively cocooned.

Alongside the sublime, the late 18th Century saw the development of the multiple concepts of the "picturesque", most associated with William Gilpin, whose observations on the Highlands (though he did not come north of Perthshire), were published in 1792 - and just at the time when continental travel was becoming more difficult as a result of the French Revolution and the subsequent development of Napoleon's continental bloc. These added another dimension to the search for scenery and, although Gilpin was less than wholehearted in his endorsement of the Highland landscapes, feeling they did not often match his criteria, he offered a corrective to Johnson’s vision.