Keen of Hamar Nature Reserve - A miniature mosaic

First impressions of the Keen of Hamar are probably of a stony wasteground – a barren, bleak and lifeless rocky desert. But a closer look will reward you with a delicate carpet of tiny and often very rare plants. This lunar landscape has a special appeal all of its own, and for a botanist it's heaven.

Perhaps the best way to explore the Keen of Hamar is on your hands and knees! That's the preferred style of the many botanists who flock here to explore this miniature mosaic of specially adapted plants.

Getting to the Keen of Hamar

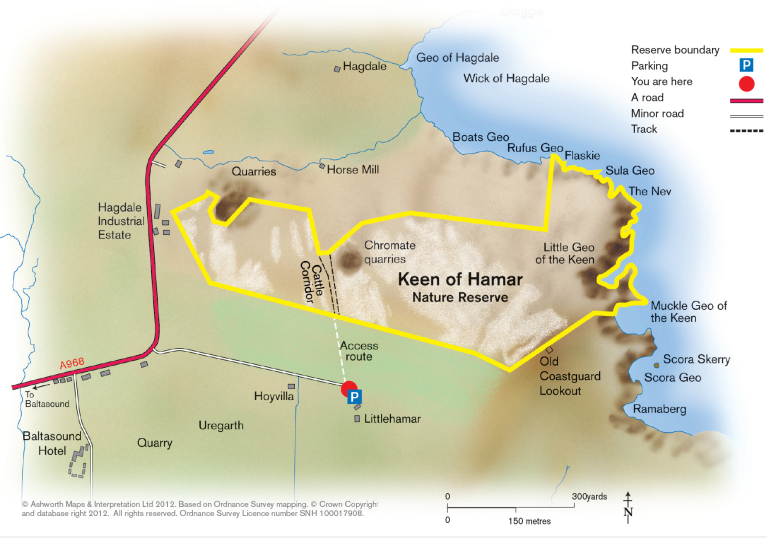

The Keen of Hamar lies beside the A968 east of Baltasound (take the side road to Little Hamar).

NatureScot

Stewart Building

Lerwick

Shetland

ZE1 0LL

Tel: 01463 667 600

From the bowels of the Earth

Hamar is old Norse for 'rocky outcrop on the hillside'. The serpentine rocks here originally formed deep beneath the oceans and aren't normally found on land. They were thrown up during dramatic Earth movements some 400 million years ago and have weathered to produce a sparse soil that's among the oldest and poorest in Britain. This barren landscape is probably how much of Northern Europe looked as the ice retreated after the last Ice Age some 11,000 years ago.

A load of old rubble

Where the Keen's serpentine rock has weathered to produce angular stones, it's known as 'debris'. Serpentine outcrops can also be found elsewhere on Unst and on the neighbouring island of Fetlar, as well as in Cornwall, on Rum and Skye and in areas of Fife. However, nowhere else is there the same expanse of serpentine debris as you find on the Keen of Hamar.

A moving landscape

On the bare north-facing slopes of the reserve you can see stone stripes – stripes of large stones and small stones sorted by size. These are formed by repeated freezing and thawing of water in the soil. This process is usually found in high mountain areas, but at the Keen these stone stripes are just 50m above sea level. The stone stripes can move a few centimetres downslope each year. If they're disturbed, the stripes can form again in a single winter.

Ice-carried soil

There are actually two types of soil on the reserve and you can clearly see the effects of this in the patchwork of grassy and bare areas on the reserve. The bare serpentine debris stands out against the thin, stoneless, sandy soils on the lower slopes, where you'll find areas of colourful heath with lots of flowers, grasses and sedges. Although this soil is also formed from serpentine, it didn't come from the bedrock at Keen of Hamar. Instead, it was carried to the site and left there by moving ice more than 10,000 years ago.

These richer areas are dominated by ling, bell heather and grasses, as well as species that normally grow on lime-rich soils, such as the tiny, fragile fairy flax and mountain everlasting with its delicate blush of pink flowers. There are also other notable Shetland species such as fragrant orchid, hoary whitlow grass, the difficult-to-spot frog orchid and the even more elusive moonwort.

Local hero

The community of flowers that have adapted to life in such harsh conditions is one of the most impressive in Europe. Some of Britain's rarest flowers grow here, including northern rock cress, Norwegian sandwort and – rarest of all – Edmondston's chickweed, which is only found on the serpentine debris on Unst. This plant – also known as Shetland mouse-ear – was discovered in 1837 by 12-year-old Thomas Edmondston of Buness, later appointed Professor of Botany at the Anderson University of Glasgow. He published A Flora of Shetland in 1845, but was tragically killed the following year, aged only 20, on a scientific expedition to South America.

Other species – particularly scurvy grass, stone bramble, thrift and sea plantain – have adapted to survive in the harsh conditions on the Keen of Hamar. Generally, they're smaller than usual and have a definite purple tinge, probably caused by the chemicals in the soil.

Little gems

The tiny white fairy flax is found in the heath areas of the Keen. It's easily missed, not only because it's small, but also because the flowers only open when the sun is out and last only a few days. The flower and its wiry roots were once used as a remedy for constipation!

Mountain everlasting is 'dioecious', which means that some plants have only male flowers and others only female. The plant relies on insects to carry the pollen from the male plants to the female plants. The pinker flowers are female and the whiter ones male, while the undersides of the leaves are a distinctive white.

Deep roots, hairy leaves

You may come across pegs set out around the reserve. These allow reserve staff to return to the same places year after year and record the changing plantlife. For more than 25 years scientists have been trying to explain why the debris is so uninviting for plants and why it hasn't grown over.

There have been various theories, including the high levels of nickel and chromium, which can poison plants, or low levels of nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus, which plants need in order to grow. These factors may have some bearing, but today the shortage of water in summer is the favoured answer. It's hard to believe that water shortage could be a problem in Shetland, but the coarse debris and hillside location mean that rain tends to drain off the site very quickly. Many of the plants do show adaptations to very dry conditions such as fleshy leaves, extreme hairiness and wide-ranging roots.

Colour from the earth

The field next to the reserve shows just how sensitive this area is. The debris here was fertilised and reseeded and this has created the green area you see today. A fenced corridor through the middle of the site allows cattle to move between areas of grazing pasture and here you can see the effects of a natural fertiliser – cattle dung.

On the opposite side of the reserve is Hagdale Quarry, which was the most important chromite mine in Britain from 1820 to 1944. Chromite was used in explosives, for metal plating and in yellow paint. Later, serpentine was quarried for bricks used to line furnaces.

Reaching the Keen

The Keen of Hamar is open all year round but the flowers are best seen in May, June and July. It lies beside the A968 east of Baltasound (take the side road to Little Hamar). A limited bus service operates between Lerwick and Baltasound, check ZetTrans website for details.

Note: this leaflet is available to download next